ABSTRACT

The main aim of the study was to investigate the coping strategies and their association with self-reported general health/psychological status in Ukrainian female refugees’ sample (N = 919) in the Czech Republic. The BRIEF-COPE inventory was employed to investigate coping strategies. Binomial logistic regression analysis was performed to investigate the association between self-reported general health status and self-reported psychological status with coping strategies adjusted by socio-demographics. The findings showed that within problem-focused coping strategies, planning what to do and taking action to try to make the stressful situation better has been found the most frequently used. Among the emotion-focused coping, more often used strategies connected with accepting the situation and learning to live in new circumstances. On side of avoidance coping strategies, only strategies to work or to do other activities ‘to take their minds off things’ were used more often. Further, outcomes revealed that ineffective coping strategies of self-blame and behavioral disengagement were associated with poorly reported general health/psychological status, and effective coping strategy was positively associated with better-reported psychological status. The research outcomes could be useful for the policymakers to help Ukrainian female refugees to better adapt to the country and avoid worsening physical and mental health statuses.

Introduction and background

The Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24th February 2022 suddenly led millions of Ukrainian to leave their homes and communities to seek safety as refugees in foreign countries such as the Czech Republic. Currently, on 16th January 2023, the Czech government has already granted ‘temporary protection’ to 481 047 refugees fleeing from Ukraine. Out of the total amount of refugees, 46% are females and 36% are children (Operational Data Portal Citation2023). The status of war-related refugees suggested that in some cases the person has been separated from family members and/or lost close family members or friends. For female refugees, especially those with children, an additional burden is taken considering the process of re-establishing their home, protecting family values and cultures, and at the same time, searching for a new job and adapting to a new place and language. Undertaking these responsibilities altogether can impact female refugees’ physical and mental health due to the pressure of the stressful situation.

Coping strategies

People who are forced to migrate to foreign countries due to war is more sensitive to being committed by stress. Stress is an unavoidable aspect of human life, and Hans Selye, known as ‘the father of stress research’, defined it as a ‘nonspecific response of the body to any demand’ (Selye and Fortier Citation1950). Additionally, Lazarus and Folkman defined stress as a ‘particular relationship between the person and the environment that is appraised by the person as taxing or exceeding his or her resources and endangering his or her well-being’ (Lazarus and Folkman Citation1984). Among theories of stress, the most dominant and influential, which the present study relies on, is the transactional model of stress and coping proposed by Lazarus and Folkman. This theory explains that an individual’s perception of an event, risk, and ability to cope determines if an event is perceiving stressful or not. According to theory, stress is an outcome of a disproportion between perceived external or internal demands and the perceived individual and social resources to cope with them (Lazarus and Folkman Citation1984).

Coping is an essential aspect of an individual’s adaptational process throughout stressful events and could predict their physiological and psychological well-being. The psychologists Lazarus and Folkman (Citation1984) defined coping as constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person. Individuals use the coping strategies perceived as more effective for them in a specific stressful event, based on previous experience. Therefore, the strategies could vary between individuals as well as within the individual (Johnson Citation1999).

Coping resources affect coping processes and could trigger different reactions, based on the availability of resources, such as taking action, managing emotions, or avoiding handling stressful events (Taylor and Stanton Citation2007). Coping actions can be organized into coping strategies (coping responses) in a multidimensional construct (Lazarus and Folkman Citation1984; Carver et al. Citation1989; Parker and Endler Citation1992). Also, individuals could employ a mix of coping strategies to adapt to a stressful event, which could be effective or ineffective regarding influence on health and well-being. The dichotomized coping approach includes problem-focused and emotion-focused, as problem-focused coping strategies are directed to alter the source of stress (action-oriented coping), and emotion-focused coping strategies are aimed to handle the emotions that accompany the perception of stress (emotion-oriented coping) (Carver et al. Citation1989). Additionally, the literature has reported other coping strategies, for instance, avoidance, which is related to the act of denying the occurrence of a stressful event. Avoidance coping strategy includes the avoidance of thinking about the stressful event and making no effort to solve the problem or change the situation (Endler and Parker Citation1994).

It has been described in the literature that each individual can respond to stressful events in both adaptive (effective or positive) and maladaptive (ineffective or negative) ways, moreover, the strategies can be adaptive or maladaptive in specific contexts (Carver and Connor-Smith Citation2010). Maladaptive coping strategies, such as behavioral disengagement and self-blame, it has previously been associated with mental and physical health (Lehavot Citation2012). Coping strategies associated with better mental health are classified as positive emotion-focused coping styles. For example, positive reframing refers to a reappraisal of a stressful event in positive terms (Stanislawski Citation2019). The coping strategies used for Ukrainian war refugees and their association with mental and physical health are still a topic lacking in the literature. Few studies have shown that emotion-focused and avoidance coping strategies were associated with psychological symptoms and self-reported poorer physical health in refugees (Matheson et al. Citation2008). Ineffective coping strategies have been demonstrated to predispose refugees to mental disorders, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression. On the opposite, effective coping may positively influence refugee health status (Matheson et al. Citation2008; Huijts et al. Citation2012). Therefore, information about how war refugees can cope with stressful situations can play a key role in physiological and psychological health.

Regarding coping strategies and refugees, demographic factors need to be considered. Age is significantly associated with coping strategies and health, when the eldest presented fewer coping recourses and worst health at the same time younger refugees are more flexible to cope with the situation (Roberts and Browne Citation2011). Education was also found to be an important factor for effective coping, as younger refugees who had a higher education were more likely to employ problem-solving strategies, at the same time older, having a lower education were more possibly to employ social support-seeking strategies (Alzoubi et al. Citation2019). It can be considered that refugees with a high level of education could have more knowledge and cognitive skills to cope with stressful events.

Lastly, the association of cope strategies and economic, financial, employment statuses, and administration of resources is a sensitive and important topic to be considered among refugees. Higher socioeconomic status and major income can help refugees to be more effective in process of adaptation to a new environment (Alzoubi et al. Citation2019). Unemployment status has been shown to have a negative impact on psychological well-being and the use of coping strategies (Roberts and Browne Citation2011). However, as demonstrated in another study, the employment status of female refugees is strongly related to proficiency in the national language of the host country (Hashimoto-Govindasamy and Rose Citation2011).

Ukrainian refugees’ profiles and health issues: evidence in Europe and the Czech Republic

According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the demographic composition of refugees from Ukraine differs from others because ‘at least 70% of the adults are women and over a third of all refugees are children’ (SAM – UKR Survey Citation2022). It can be interpreted that most of the refugees could be mothers with children. The European Union Agency for Asylum in partnership with OECD conducted the Surveys of Arriving Migrants from Ukraine (from 11th April to 7th June 2022) across European countries. The demographic profile of respondents (N = 2369) was as follows: most of them are female (82%) between 18 and 44 years (81%), with university degrees (73%), and had a job in their motherland (77%). Work opportunities were the most important reason among the refugees for choosing the destination country. Refugees rated their general satisfaction with access to medical care as 3.2 out of 5; children’s education as 3.4; and living conditions as 3.6. An important point to address is that 73% of refugees have been vaccinated for COVID-19 (SAM – UKR Survey Citation2022).

Another online and phone-based survey with refugees from Ukraine across European countries was conducted by the United Nation Refugee Agency (UNHCR). Data (N = 4871) was collected in the Czech Republic, Hungary, the Republic of Moldova, Poland, Romania, and Slovakia (16th May to 15th June 2022), including 7 focus groups conducted in Poland and Romania. Similarly, the sample was 90% of women and children; 77% of female refugees have technical, vocational, or university education and 76% of them had jobs in Ukraine. The main reasons to choose the host country were safety, family ties, and access to employment. Important to point out that respondents have experience in such crucial branches of the economy as education (17%) and medical (11%) services as well as social services (5%) (UNHCR Citation2022b). The UNHCR’s follow-up research was conducted in 43 countries (N = 4814) (between August and September 2022) by using phone-based surveys, web-based surveys, and face-to-face interviews as well as a series of focus groups. Likewise, findings showed that the majority (89%) of respondents are females with an average age of 42 years old and completed university studies (70%), 63% of them had jobs in Ukraine including such sectors as education (16%), and health and social service (7%). At the time of the survey, 28% of them were currently employed in the host country. Regarding main sources of income: 47% of households have social protection benefits/cash assistance, 32% – have savings, 35% – have salaries, 12% – have pensions, and 12% – have transfers from relatives or friends in Ukraine (UNHCR Citation2022a).

In June 2022, the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs of the Czech Republic (MLSA) surveyed Ukrainian refugees, who settled in the country. An online questionnaire was sent by email to 65,145 refugees that applied for humanitarian benefits and received feedback from 29, 012 adults and 21, 224 children. The survey sample consists of 44% women and 36% children. 75% of the adult are under 45 years and 35% of them have university degrees. More than 50% of adults are economically active, 80% of them are working in low-skilled occupations and approximately 75% of respondents reported that they are in a ‘very unsatisfactory’ or ‘critical’ financial situation (Klimešová et al. Citation2022). The survey of the MLSA was followed by panel waves prepared by the MLSA in cooperation with the Institute of Sociology of the Czech Academy of Sciences. The panel waves about the health and mental health of Ukrainian refugees included 1347 participants and collected data in September 2022. The panel wave showed that refugees reported problems with access to medical services: 62% of adults and 53% of children do not have a primary healthcare physician. Moreover, 19% of refugees reported that they did not get an appointment with the doctor when they needed it. The main barrier was defined as absent Czech language skills (45%) as well as a lack of information about how to register with a doctor and a long waiting list. The survey showed that the health status of refugees is related to their socio-economic situation, more precisely, refugees in material deprivation, those without basic knowledge in Czech, and those in worse housing conditions estimated their health worse (Hlas Ukrajinců: Zdraví a služby Citation2022). Additionally, the study showed that 45% of both gender refugees have moderate symptoms of depression or anxiety, which are connected with refugees’ background regarding family separation and other war issues and socioeconomic status in the Czech Republic connected to unemployment, poor housing, material deprivation, lack of language skills, and low level of children's enrolling to schools and kindergartens. The main obstacle to getting medical assistance with mental health issues was stated as the lack of information on what services are available and the shame to seek psychiatric help (Hlas Ukrajinců: Duševní zdraví Citation2022).

Taking into account the above, considering that effective coping strategies play an important role in mental and physical health, but also can be influenced by some individual characteristics, understanding how Ukrainian female refugees are coping with the stressful situation becomes necessary. The main aim of the study was to identify the coping strategies used by Ukrainian female refugees settled in the Czech Republic since 24 February 2022. After, it was investigated the association of different coping strategies with the demographic characteristics of respondents, and self-reported general health/psychological status. Additionally, the study translated and tested the psychometric properties of the Brief Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced (the Brief-COPE) in the specific sample.

Methods

Participants and data collection

The study focuses on Ukrainian female refugees which are settled in the Czech Republic. The inclusion criteria included being a female aged above 18 years and coming to the Czech Republic due to the war (from 24th February). This study is part of a big project involving female and children refugees in the Czech Republic. Data were obtained via an online survey, created in the Ukrainian language, with questionnaires related to self-reported physical health and psychological status, coping strategies, and demographic characteristics. The survey was distributed through social media groups (Facebook, Telegram, and Viber), non-government organizations working with refugees, and Czech schools in which Ukrainian children are enrolled. Females, who had agreed to participate in the study, were asked to sign a consent form online before completing the questionnaires. They also were informed about voluntary participation and the possibility of withdrawing from the study at any given stage. The data was collected between the 6th of June the and 6th of September, 2022.

Demographic characteristics

To characterize the participants, the following demographical information was collected: age, marital status, number of children, place of residence (in Ukraine and the Czech Republic), the highest level of education obtained, employment status (in Ukraine and the Czech Republic), financial situation (in Ukraine and the Czech Republic) ().

Table 1. Socio-demographic, self-reported general health, emotions, and psychological status characteristics of Ukrainian female refugees in the Czech Republic (n = 919).

Self-reported general health and emotions and psychological status

Self-reported health (SRH) is commonly used as a measure of general health when extensive measurements of health are not possible because of the connection of this indicator to disease burden as well as to mental health. Besides, ‘SRH reflects coping resources and influences health-related behavior that affects outcome’ (Lorem et al. Citation2020). In this study, self-reported health was used as an indicator of the females’ general subjective health. This indicator has been used for monitoring health outcomes and measures of morbidity, mortality, and health care services (Wu et al. Citation2013; Wuorela et al. Citation2020). The SRH measured the following question: ‘Please estimate your physical health today’. The respondents should choose one of the 5-point options: ‘very bad’, ‘bad’, ‘fair’, ‘good’, or ‘very good’. Similarly, a question about their emotions and psychological status was asked, with the option to answer from ‘very bad’ to ‘very good’.

Coping strategies measures

To assess the coping strategies of Ukrainian female refugees, the study utilized the BRIEF-COPE. In the literature, few instruments are validated to measure coping strategies (Schwarzer and Schwarzer Citation1996). The BRIEF-COPE Inventory is an abbreviated version of the original 60-item Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced inventory (Carver et al. Citation1989). Carver with colleagues developed a multidimensional coping inventory to measure a variety of ways in which people can respond to stressful events. The COPE Inventory has a theory-based measure using the transactional model of stress and coping (Lazarus and Folkman Citation1984) and the behavioral self-regulation model (Carver et al. Citation1989) in contrast to other tools constructed empirically. Unlike other tools, the COPE has shown reliable psychometric properties of both dispositional and situational coping efforts (Carver Citation1997; Carver et al. Citation1989). Although, the BRIEF-COPE is one of the most widely used tools for the English and non-English-speaking populations (Lehavot Citation2012; Furman Citation2018) used in a previous study with refugees (Kapsou et al. Citation2010).

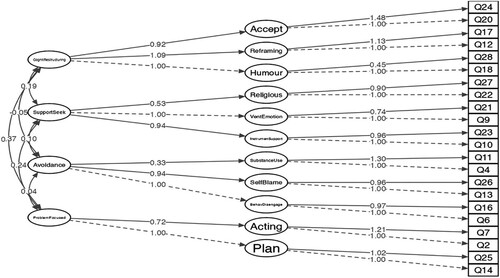

The Brief-COPE includes 28 items to measure different coping strategies for stressful events. It measures 14 sub-scales of coping reactions (two questions each) about: active coping, planning, instrumental support, positive reframing, acceptance, emotional support, humor, religion, venting, self-distraction, denial, behavioral disengagement, substance use, and self-blame. Each item was scored using a 4-point Likert scale (1 = I haven’t been doing this at all to 4 = I’ve been doing this a lot). According to the author, researchers could modify the instrument to fit sample characteristics (e.g. removing or changing scales or items to fit the sample) (Caver Citation1997). This study applied the three-dimension conceptual system which includes problem-focused coping (dealing with sources of stress), emotion-focused coping (handling feelings and thoughts associated with the stressor), and avoidant coping (avoiding dealing with the stressor or associated emotions) () (Carver et al. Citation1989; Huijts et al. Citation2012).

Table 2. Frequency of use of coping strategies by Ukrainian female refugees (n = 919).

The instrument was forward and backward translated from English to the Ukrainian language for use in the present study. The translation was performed by two different translation agencies and reviewed by a researcher and psychologist. The Ukrainian translation of the BRIEF-COPE demonstrated a valid and reliable instrument and can be used in future studies to measure coping strategies in the Ukrainian population (Appendix 1).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics of central tendency and dispersion, absolute and relative frequency were used to display the female refugees’ responses. Binomial logistic regression analysis was performed to investigate the association between self-reported general health status (Model 1) and self-reported emotions and psychological status (Model 2) with coping strategies (14 scales of the BRIEF-COPE) adjusted by socio-demographic covariates. The results are reported in odd ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The BRIEF-COPE statistic validation was better described in the supplementary materials (Appendix 2–6).

Jamovi statistic software version 2.2.5. was utilized to perform the confirmatory factor analysis in the BRIEF-COPE validation process (The jamovi project Citation2021; R Core Team Citation2021; Gallucci and Jentschke Citation2021; Rosseel Citation2019; Epskamp et al. Citation2019). The remaining analysis was performed via Statistical Package for the Social Sciences IBM SPSS version 28. All statistical analysis was performed at a 5% level of significance.

Results

A total of 919 responses from Ukrainian female refugees were obtained. According to the descriptive statistic (), the average age of the respondents was 38 years old (M = 37.61; SD = 9.57). 68.4% of respondents are married/cohabited and more than 70% reported that they have children under 18 years old. Most respondents have a university education (71%), lived in Ukrainian cities and towns (88.7%), and had paid work in Ukraine (73.8%). They came from central (34.4%), south (28.8%), and east (27.6%) parts of Ukraine. About 40% settled in the two biggest cities of the Czech Republic (20% – Prague and 19% – Brno). The average time the refugee stayed in the Czech Republic before participating in the survey was 15 weeks (M = 15.12; SD = 5.33). According to the study, 39.7% of respondents plan to come back to Ukraine, 9.2% don’t plan and others don’t know the answer yet.

As regards, self-reported health, 43% of females reported their general health as good, 46.8% as fair, and 10.2% as bad and very bad. In addition, 27.9% reported their health has worsened during the last month and 4.5% worsening of their health or sustained injury due to the war. Also, Ukrainian refugees were asked to report their emotions and psychological status, on a 5-point Likert scale, as a result, 52.7% self-reported their status as fair, 26% as bad, and 7.7% as having very bad emotions and psychological status.

Coping strategies responses and the BRIEF-COPE validation

Coping strategies used by Ukrainian female refugees are presented in . Within the problem-focused coping strategies planning what to do and taking action to try to make the situation better has been found to be among the most frequently used coping strategies. Acting coping includes doing something about the stressful situation (3.05) and taking action to try to make the situation better (3.15) while planning consists of thinking hard about what steps to take (3.11) and developing a strategy for what to do (3.02). The instrumental support strategies such as trying (2.23) or getting (2.26) help and advice from other people were reported as a little less used compared with those mentioned before. Among the emotion-focused coping strategies, two items used more often connected with acceptance, firstly, learning to live in new circumstances (3.01) and, secondly, accepting reality (2.95). The least employed were strategies such as humor ‘making fun of the situation’ (1.62), emotional support from others (1.83), self-blame ‘for things that happened’ (1.73), and religion ‘to find comfort in my religion or spiritual beliefs’ (1.89). Within the avoidance coping strategies the most often used strategy relating to self-distraction was working or doing other activities to take their minds off things (3.07) and doing something to think about the stressful situation less (2.68). The least frequently employed substance use strategies to ‘feel better’ (1.48) and to ‘get through it’ (1.39).

Concerning the BRIEF-COPE validation, the general internal consistency measured by Cronbach’s alpha was 0.81, which is considered ‘good’. Similarly, the internal consistency of each of the three sub-scales (problem-focused, emotional, and avoidant) was between 0.65 and 0.77. Inter-correlation coefficients between the scales in the BRIEF-COPE are displayed in Appendix 2. These correlations were not strong (from 0.01 to 0.59) which could be explained by the fact that Ukrainian female refugees used different coping strategies during the adaptation process in the Czech Republic. Substance use had the lowest mean inter-correlations with all the other subscales. Informational and emotional supports had the highest mean inter-correlation (0.59) followed by planning and active coping (0.53). Cronbach’s reliability for the BRIEF-COPE 14 scales revealed that emotional support (0.46), self–distraction (0.42), and denial (0.48) cannot be considered consistent, so they were deleted from further analysis.

Appendix 3 presented the results of exploratory factor analysis, conducted with principal axis factoring with oblimin rotation and Kaiser normalization. The scree plot suggested a 7-factor structure, accounting for 51.35% of the variance. Two items (Q21 and Q24) with factor loadings ≥0.3 were loaded on more than one factor, they both additionally result in Factor 7. The extracted factor 1 included the items of planning, active coping, and one item of acceptance scales (which were loaded into two factors). Overall, this factor appeared to form a problem-focused coping strategy (Carver et al. Citation1989). Factor 2 consisted of behavioral disengagement and self-blame items. Factor 3 separated the substance use items. Therefore, factors 2 and 3 reflected the avoidant coping strategy (Carver et al. Citation1989). Factor 4 contained the instrumental support and venting scales. Factor 5 separated the religious items. Accordingly, factors 4 and 5 reflected the support-seeking coping strategy (Doron et al. Citation2014). Factor 6 corresponded to humor and positive reframing. Factor 7 consists of acceptance scales. Thus, factors 6 and 7 reflected the cognitive restructuring coping strategy (Doron et al. Citation2014). Appendix 4 showed indexes of good-fit. The SRMR and the RMSEA values less than 0.08 are demonstrating a reasonable and close fit of the model to the data. Other indexes CFI and TLI with values above 0.95 demonstrate a good fit too (Hu and Bentler Citation1999).

According to the confirmatory factor analysis, the structure of the BRIEF-COPE questionnaire data for Ukrainian female refugees in the Czech Republic showed poor data fit for the three-dimension model, i.e. problem-focused, emotion-focused and avoidant copings. Goodness-of-fit indexes show poor results for the three-factor model: chi-square = 2130 (df = 195), RMSEA = 0.115, SRMR = 0.103, CFI = 0.917. Therefore better fit is for the four-dimensional model: cognitive restructuring (acceptance, positive reframing, humor), support seeking (religion, venting, instrumental support), avoidance (substance use, self-blame, behavioral disengagement), problem-focused (active coping, planning) (Doron et al. Citation2014) as it is shown in . Scales are reported as squares, and dimensions as ellipses. All the factor loadings are significantly different from zero (Appendixes 5 and 6).

Self-reported health/emotions and psychological status and coping strategies associations

The binomial logistic regression analysis was conducted to check the associations between self-reported general health/emotions and psychological status and coping strategies. Self-reported general health (SRH) was used as a dependent variable for Model 1. SRH was dichotomized into good SRH which includes very good and good categories and poor SRH, which includes bad and very bad categories. Self-reported emotions and psychological status (SREPS) also was dichotomized into: good SREPS which includes very good and good categories and poor SREPS, which includes bad and very bad categories, and used for Model 2. As predictor variables were used the coping strategies were measured as 14 scales of the BRIEF-COPE. Socio-demographic variables such as the age of respondents were categorized into three age groups (under 30, 30-40, and above 40), also used variables: having children under 18 yrs., and staying in the Czech Republic (in weeks). Socio-economic variables such as education, economic situation (in Ukraine/the Czech Republic), employment in the Czech Republic, getting financial aid, and free medical insurance.

Nagelkerke R 2 for Model 1 is 50.2%, and 87.1% of cases are correctly classified. Nagelkerke R 2 for Model 2 is 55.0% and 83.9% of cases were correctly classified. Model 1 was additionally adjusted for two intersections, first, between religion and age groups because of an assumption that older respondents would use more often religion as a coping strategy, and second between having children under 18 yrs. and age because of an assumption that respondents from younger age groups would have more chances to have children under 18 yrs. ().

Table 3. The binomial logistic regression analysis.

The binomial logistic regression analysis results are presented in . Firstly, in both models, coping strategies such as self-blame and behavioral disengagement were important factors associated with poor reported general health/emotions and psychological status. Self-blame strategies showed moderate use among respondents ‘I’ve been criticizing myself’ (2.48) and I’ve been blaming myself for things that happened (1.73) have a significant association with poor SRH (OR = 2.84) and poor SREPS (OR = 2.79). Behavioral disengagement strategies showed moderate use among respondents ‘I've been giving up trying to deal with it’ (2.24) and ‘I’ve been giving up the attempt to cope’ (2.01) have a significant association with poor SRH (OR = 2.34) and poor SREPS (OR = 4.42). Secondly, females who are using positive reframing coping strategy expected less likely to report poor emotions and psychological status (OR = 0.5).

In addition, it was revealed, that respondents whose economic situation in the Czech Republic remained the same or became worst (compared to their situation in Ukraine) were more likely to report poor general health. On the contrary, females who had enough money for living and some savings were less likely to report poor general health, probably because of the possibility to use their savings for settling in a new country which positively connected to health status. Also, respondents from the age group above 40 or those who have a job in the Czech Republic were more likely to report poor emotions and psychological status. The data showed that the longer a person stays in the Czech Republic the less likely their report poor emotions and psychological status. Females, having children under 18 yrs., were less likely to report poor general health.

Discussion

The present study sought to identify the coping strategies used by Ukrainian female refugees settled in the Czech Republic since 24 February 2022 and investigate the association with their self-reported general health/psychological status and demographic characteristics. Supplementary, the psychometric properties of the coping strategies instrument, the Brief Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced (the BRIEF-COPE) were tested by translation and validation in the Ukrainian-speaking sample. The major findings can be resumed as follow: (1) mothers of children under 18 years, with a high level of education and with a paid job in their motherland was the most refugee respondent; (2) refugees estimated their psychological status three times worst that general physical health; (3) refugees more often used problem-focused and emotion-focused strategies, and less avoidant coping strategies; (4) ineffective coping strategies of self-blame and behavioral disengagement were associated with poorly reported general health/psychological status and effective coping strategy was positively associated with better-reported psychological status; (5) the BRIEF-COPE questionnaire translated into the Ukrainian language presented acceptable proprieties in the female refugees’ sample.

The characteristics of Ukrainian female refugees from our study are similar to the other surveys about Ukrainian refugees that settled around Europe. Mothers of children under 18 years, with a high level of education and with a paid job in their motherland was the most refugee in the Czech Republic and also in the SAM – UKR Survey (2022), in the UNHCR Regional Bureau for Europe Surveys # 1 and # 2 (UNHCR Citation2022a, Citation2022b). Considering the self-reported health in this research, only 10.2% of females reported their general physical health as poor, nevertheless, for the self-reported psychological status, one-third (33,7%) of them estimate it as bad and very bad status. The results are very similar to 31% of refugees of both genders from a previous survey in the Czech Republic, which reported being aware of the possible mental disorder according to findings, and psychological instruments showed that 45% of refugees of both genders have moderate symptoms of depression or anxiety (Hlas Ukrajinců: Duševní zdravi Citation2022). Outcomes from the surveys described a positive trend in which the longer female stays in the Czech Republic the less likely she is to report poor emotions and psychological status. It could be because over time the person better adapts to new conditions, and culture solves household problems, and learns the basic of the Czech language.

Respondents from the oldest age group (above 40 yrs.) in our study are more likely to report poor emotions and psychological status compared with younger age groups. Previously, a study demonstrated a significant association between refugees’ age and their health, the eldest have fewer coping recourses and worst health (Roberts and Browne Citation2011).

A previous study showed a significant association between better self-rated physical and mental health with childlessness in the refugee population (Nesterko et al. Citation2020). Our findings showed that females, having children under 18 yrs. were less likely to report poor general health, it can be probably because, for mothers caring for children, the process of re-establishing a home, protecting family and cultural values, and securing children’s health care and education were effective problem-focus strategies.

Socioeconomic status and income were significantly correlated with subjective health and psychological well-being. Female refugees whose economic situation remained the same or became worst compared to before in Ukraine were more likely to report poor general health. Higher socioeconomic status and income help refugees to be more effective in process of adaptation to a new environment (Crabtree Citation2010). Unfortunately, according to the survey of the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs of the Czech Republic, approximately 75% of Ukrainian refugees of both gender in the Czech Republic reported that they are in a ‘very unsatisfactory’ or ‘critical’ financial situation after settling in the country (Klimešová et al. Citation2022). The same outcome was found in the panel waves ‘The Voices of Ukrainians in the Czech Republic’ where the health status of refugees is related to their socio-economic situation, refugees in deprivation and with poor housing conditions estimated their health worse (Hlas Ukrajinců: Zdraví a služby Citation2022). On the contrary, our research showed that females who had enough money for living and some savings in Ukraine were less likely to report poor general health, probably because the possibility to use their savings for settling in a new country, is positively connected to health status.

Additionally, previous studies have shown that unemployment status hurts psychological well-being and the use of coping strategies (Roberts and Browne Citation2011). This study showed the opposite association because respondents who got a job in the Czech Republic were more likely to report poor psychological well-being. It could be explained, as 74,7% of respondents have high education, 30.1% got a job in the Czech Republic but only 7.4% of them got the job according to their qualifications. Other studies also supported our results because findings showed that refugees with higher education have poorer mental health, more stress, and reported lower job satisfaction because their current employment is not appropriate to their skills and qualifications (Bridekirk et al. Citation2021). So, females with high education who got unqualified jobs in the Czech Republic got low payments and lowered their social status which caused worsening their psychological well-being. Among unemployment reasons, respondents declared that only low-paid manual labor is offered (30.9%), impossible to be employed by qualification (36.1%). This is also supported by the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs (MLSA) of the Czech Republic Survey results, therefore 80% of refugees are working in low-skilled occupations (Klimešová et al. Citation2022).

One more issue that restricted work opportunities for Ukrainian refugees in the Czech Republic reported by participants are the lack of knowledge of Czech and/or English languages (45.6%) needed for getting work. According to previous studies employment status of female refugees is strongly related to proficiency in the national language of the host country (Hashimoto-Govindasamy and Rose Citation2011). Those refugees who cannot communicate in Czech reported their health as worse also in another survey conducted in the Czech Republic (Hlas Ukrajinců: Zdraví a služby Citation2022), so it is important for refugees to have access to free language courses.

Considering the coping strategies, to our best knowledge, this study is the first to examine the factor structure of the BRIEF-COPE in Ukrainian female refugees in the Czech Republic. The findings of this research are unique and pioneering in the area. Coping strategies play a key role in both mental and physical health, in the case of Ukrainian female refugees settled in the Czech Republic, their health could be impaired significantly due to the accumulation of different stressful events connected with war, forced migration, and settlement in a foreign country. The BRIEF-COPE in our study suggested a 7-factor structure, previous studies reported a two or more-factor structure of the BRIEF-COPE (Kapsou et al. Citation2010; Tang et al. Citation2021). The major findings of the present study are that Ukrainian female refugees used different coping strategies during the adaptation process in the Czech Republic. The results showed that Ukrainian female refugees more often used problem-focused and emotion-focused strategies, and less avoidant coping strategies. Similar results were presented earlier in studies with refugees (Al-Smadi et al. Citation2017; Khawaja et al. Citation2008).

In times of uncertainty, problem-focused coping is vital, female refugees are planning and taking the actions that are connected to re-establishing homes for children, deciding about their education (in the Czech education system or Ukrainian online or both), looking for possibilities of work and studying the language of the host country. Additionally, they have to plan their return home or integration into a foreign country’s culture. Refugees use emotion-focused coping thought seeking and using instrumental support by getting help from the government and NGOs in the Czech Republic regarding getting access to the educational system for children or medical services for all family members. Moreover, they overcome many bureaucratic obstacles related to obtaining special visas, applying for humanitarian financial or material aid, issuing medical insurance, finding housing, and looking for possibilities to enroll children in kindergartens and schools. They use emotion-coping to accept a new reality and learn to live in an environment and culture, uniting, supporting, and helping each other. Female refugees are forming real and virtual (through social media) communities for self-help, to support Ukraine through organizing and participating in demonstrations, fundraising, and collecting humanitarian aid for people who stay in Ukraine. It is worth mentioning, that the study sample consists mainly of highly educated mothers with children with an average age of 38 yrs., so using alcohol or other drugs as well as self-blame and behavioral disengagement is rarely a choice for them.

Additional outcomes revealed that within problem-focused coping, the association between using the effective coping strategy of positive reframing reported better psychological status. Positive reframing refers to the more positive reinterpretation of stressful events and was used by Ukrainian female refugees moderately (2.73). Problem-focused strategies were associated with better health outcomes in previous studies as well (Penley et al. Citation2002; Horwitz et al. Citation2018; Stanisławski Citation2019). Contrarily, within emotion-focused coping, it was found associations between ineffective coping strategies self-blame, and worst reported general health/psychological status. Additionally, within avoidant coping, it was discovered associations between ineffective coping strategies behavioral disengagement, and worst reported general health/psychological status. Previous studies had revealed the same outcomes, as behavioral disengagement and self-blame were significantly associated with mental and physical health (Lehavot Citation2012; Stanisławski Citation2019). Moreover, psychological symptoms and self-reported poorer physical health were associated with emotion-focused and avoidance coping strategies (Matheson et al. Citation2008; Stanisławski Citation2019).

The present study, up to now, is the first to provide an empirically and theoretically supported structure model of the BRIEF-COPE and also the first to show the association between self-reported health/psychological status and coping strategies in Ukrainian female refugees settled in the Czech Republic. However, some limitations should be highlighted. The use of online questionnaires restricted the participation of educated females with good digital skills. Therefore, additional analysis will be further conducted to triangulate the results including an analysis of in-depth interviews with Ukrainian female refugees in the Czech Republic. Future research should be included older females with low digital literacy. Additionally, self-reporting may have some degree of social desirability bias; however, some strategies were used in the present study to reduce social desirability bias such as anonymity, self-administered questionnaires, and forced-choice items.

Conclusion

Ukrainian female refugees from the present study used various coping strategies for adaptation in the Czech Republic. Most often they used effective active-coping strategies. Planning what to do and taking action to try to make the situation better was found to be among the most frequently used coping strategies. Among the emotion-focused coping strategies, there were two items used more often connected with accepting the situation and learning to live in new circumstances. Less likely that Ukrainian female refugees used avoidance coping strategies, only strategies to work or to do other activities to take their minds off things were used. The least frequently used coping strategies were substance use and making fun of the situation. There was found an association between ineffective coping strategies self-blame and behavioral disengagement with poor reported general health/ psychological status. Usage of an effective coping strategy such as positive reframing is associated with less likelihood to report poor emotions and psychological status.

The conclusion highlights that the usage of effective coping strategies could be protective to reduce negative psychological distress in this population. Also, these research outcomes could be used in the social policy of the Czech government to help Ukrainian female refugees to better adapt to the country and avoid worsening physical and mental health status. Social policies can reduce the negative physical and mental health outcomes associated with refugees’ resettlement. First of all, poverty is a major social determinant of health, it is important to ensure adequate financial support and work possibilities. Secondly, vital access to health care services, especially, specialized mental health care services for the most vulnerable refugee should be provided according to their needs. Thirdly, enable, Ukrainian refugees with appropriate education and work experience access to the job market in such areas as education, health care, and social services disregarding Czech language knowledge to serve the Ukrainian refugee population. Fourthly, it important is to provide more information about symptoms of mental disorders and effective coping strategies (health promotion) through NGOs, schools, social networks, and health care staff as well as about possibilities to access health care and social services when needed. Fifthly, grant free Czech language courses for refugees, in particular, there is a lack of courses for those who already know the Czech language at a basic level, but advanced knowledge is necessary to perform more skilled and better-paid work.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (47.4 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the reviewers for valuable comments that improved the quality of the manuscript as well as all of the Ukrainian females who took part in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Iryna Mazhak

Iryna Mazhak, Ph.D. (kandydat nauk) in Medical Sociology, Associate Professor at National University ‘Kyiv Mohyla Academy' (Ukraine) and academic researcher at Masaryk University (Czech Republic). She is interested in social determinants of health, social inequalities in health, health policy analysis, and refugees’ health status and coping strategies.

Ana Carolina Paludo

Ana Carolina Paludo, Sport Science Ph.D., is a postdoctoral researcher at Masaryk University. She supports academics in research methods and academic writing at the Faculty of Sports Studies. Her main research interests are focused on behavioral and physiological responses related to athletes' performance.

Danylo Sudyn

Danylo Sudyn, kandydat nauk (Ph.D. equivalent), in Sociology, Associate Professor at Ukrainian Catholic University (Ukraine). His research interests include international migrations, methodology of quantitative social research, national identity and historical memory.

References

- Al-Smadi, A. M., Tawalbeh, L. I., Gammoh, O. S., Ashour, A., Alzoubi, F. A. and Slater, P. (2017) ‘Predictors of coping strategies employed by Iraqi refugees in Jordan’, Clinical Nursing Research 26(5): 592–607.

- Alzoubi, F. A., Al-Smadi, A. M. and Gougazeh, Y. M. (2019) ‘Coping strategies used by Syrian refugees in Jordan’, Clinical Nursing Research 28(4): 396–421.

- Bridekirk, J., Hynie, M. and Syria, L. (2021) ‘The impact of education and employment quality on self-rated mental health among Syrian refugees in Canada’, Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 23: 290–7.

- Carver, C. S. (1997) ‘You want to measure coping but your protocol’ too long: consider the brief cope’, International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 4(1): 92–100.

- Carver, C. S. and Connor-Smith, J. (2010) Personality and coping.

- Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F. and Weintraub, J. K. (1989) ‘Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 56(2): 267–83.

- Crabtree, K. (2010) ‘Economic challenges and coping mechanisms in protracted displacement: a case study of the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh’, Journal of Muslim Mental Health 5(1): 41–58.

- Doron, J., Trouillet, R., Gana, K., Boiché, J., Neveu, D. and Ninot, G. (2014) ‘Examination of the hierarchical structure of the brief COPE in a French sample: empirical and theoretical convergences’, Journal of Personality Assessment 96(5): 567–75.

- Endler, N. S. and Parker, J. D. (1994) ‘Assessment of multidimensional coping: task, emotion, and avoidance strategies’, Psychological Assessment 6(1): 50.

- Epskamp, S., Stuber, S., Nak, J., Veenman, M. and Jorgensen, T. D. (2019) semPlot: Path Diagrams and Visual Analysis of Various SEM Packages’ Output. [R Package]. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=semPlot.

- Furman, M., Joseph, N. and Miller-Perrin, C. (2018) ‘Associations between coping strategies, perceived stress, and health indicators’, Psi Chi Journal of Psychological Research 23: 1.

- Gallucci, M. and Jentschke, S. (2021) SEMLj: jamovi SEM Analysis. [jamovi module]. For help please visit https://semlj.github.io/.

- Hashimoto-Govindasamy, L. S. and Rose, V. (2011) ‘An ethnographic process evaluation of a community support program with Sudanese refugee women in western Sydney’, Health Promotion Journal of Australia 22(2): 107–12.

- Hlas Ukrajinců: Duševní zdraví. 2022. Výzkum mezi uprchlíky. Sociologický ústav AV ČR. Národní ústav duševního zdraví. PAQ Research. 21 p.

- Hlas Ukrajinců: Zdraví a služby. 2022. Výzkum mezi uprchlíky. Sociologický ústav AV ČR. PAQ Research. 14 p.

- Horwitz, A. G., Czyz, E. K., Berona, J. and King, C. A. (2018) ‘Prospective associations of coping styles with depression and suicide risk among psychiatric emergency patients’, Behavior Therapy 49(2): 225–36.

- Hu, L. T. and Bentler, P. M. (1999) ‘Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives’, Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 6: 1–55.

- Huijts, I., Kleijn, W. C., van Emmerik, A. A., Noordhof, A. and Smith, A. J. (2012) ‘Dealing with man-made trauma: the relationship between coping style, posttraumatic stress, and quality of life in resettled, traumatized refugees in the Netherlands’, Journal of Traumatic Stress 25(1): 71–8.

- The jamovi project (2021) jamovi. (Version 2.2) [Computer Software]. Available from https://www.jamovi.org.

- Johnson, J. E. (1999) ‘Self-regulation theory and coping with physical illness’, Research in Nursing & Health 22(6): 435–48.

- Kapsou, M., Panayiotou, G., Kokkinos, C. M. and Demetriou, A. G. (2010) ‘Dimensionality of coping: an empirical contribution to the construct validation of the brief-COPE with a Greek-speaking sample’, Journal of Health Psychology 15(2): 215–29.

- Khawaja, N. G., White, K. M., Schweitzer, R. and Greenslade, J. (2008) ‘Difficulties and coping strategies of Sudanese refugees: a qualitative approach’, Transcultural Psychiatry 45(3): 489–512.

- Klimešová, M., Šatava, J. and Ondruška, M. (2022) Situace uprchliku z Ukrajiny. Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, 40 p.

- Lazarus, R. S. and Folkman, S. (1984) Stress, Appraisal, and Coping, New York: Springer Publishing Company.

- Lehavot, K. (2012) ‘Coping strategies and health in a national sample of sexual minority women’, American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 82(4): 494.

- Lorem, G., Cook, S., Leon, D. A., Emaus, N. and Schirmer, H. (2020) ‘Self-reported health as a predictor of mortality: a cohort study of its relation to other health measurements and observation time’, Scientific Reports 10(1): 1–9.

- Matheson, K., Jorden, S. and Anisman, H. (2008) ‘Relations between trauma experiences and psychological, physical and neuroendocrine functioning among Somali refugees: mediating role of coping with acculturation stressors’, Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 10(4): 291–304.

- Nesterko, Y., Jäckle, D., Friedrich, M., Holzapfel, L. and Glaesmer, H. (2020) ‘Factors predicting symptoms of somatization, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, self-rated mental and physical health among recently arrived refugees in Germany’, Conflict and Health 14: 1–12.

- Operational Data Portal for the Ukraine Refugee Situation. https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine [Accessed 16 Jan 2023].

- Parker, J. D. and Endler, N. S. (1992) ‘Coping with coping assessment: A critical review’, European Journal of Personality 6(5): 321–44.

- Penley, J. A., Tomaka, J. and Wiebe, S. (2002) ‘The association of coping to physical and psychological health outcomes: a meta-analytic review’, Journal of Behavioral Medicine 25: 551–603.

- R Core Team (2021) R: A Language and environment for statistical computing. (Version 4.0) [Computer software]. Available from https://cran.r-project.org. (R packages retrieved from MRAN snapshot 2021-04-01).

- Roberts, B. and Browne, J. (2011) ‘A systematic review of factors influencing the psychological health of conflict-affected populations in low-and middle-income countries’, Global Public Health 6(8): 814–29.

- Rosseel, Y. (2019) ‘Lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling’, Journal of Statistical Software 48(2): 1–36.

- Schwarzer, R. and Schwarzer, C. (1996) ‘A critical survey of coping instruments’, in M. Zeidner and N. S. Endler (eds.), Handbook of Coping: Theory, Research, Applications, New York: Wiley, pp. 107–32.

- Selye, H. and Fortier, C. (1950) ‘Adaptive reaction to stress’, Psychosomatic Medicine 12(3): 149–57.

- Stanisławski, K. (2019) ‘The coping circumplex model: an integrative model of the structure of coping with stress’, Frontiers in Psychology 10: 694. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00694.

- Surveys of Arriving Migrants from Ukraine (SAM – UKR). Factsheet (14 June 2022) European Union Agency for Asylum. https://euaa.europa.eu/publications/surveys-arriving-migrants-ukraine-factsheet-14-june-2022.

- Tang, W. P. Y., Chan, C. W. and Choi, K. C. (2021) ‘Factor structure of the brief coping orientation to problems experienced inventory in Chinese (Brief-COPE-C) in caregivers of children with chronic illnesses’, Journal of Pediatric Nursing 59: 63–9.

- Taylor, S. E. and Stanton, A. L. (2007) ‘Coping resources, coping processes, and mental health’, Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 3(1): 377–401.

- UNHCR (2022a) Lives on hold: intentions and perspectives of refugees from Ukraine. UNHCR Regional Bureau for Europe. # 2. September 2022, 25 p.

- UNHCR (2022b) Lives on hold: profiles and intentions of refugees from Ukraine. Czech Republic, Hungary, Republic of Moldova, Poland, Romania & Slovakia. Regional International Report # 1. UNHCR Regional Bureau for Europe. July 2022, 21 p.

- Wu, S., Wang, R., Zhao, Y., Ma, X., Wu, M., Yan, X. and He, J. (2013) ‘The relationship between self-rated health and objective health status: a population-based study’, BMC Public Health 13: 1–9.

- Wuorela, M., Lavonius, S., Salminen, M., Vahlberg, T., Viitanen, M. and Viikari, L. (2020) ‘Self-rated health and objective health status as predictors of all-cause mortality among older people: a prospective study with a 5-, 10-, and 27-year follow-up’, BMC Geriatrics 20: 1–7.