ABSTRACT

During the past decade, academic interest in physical attractiveness-based social inequalities has spread significantly beyond the United States to Europe. In previous research, however, there has been no consensus on whether the socioeconomic outcomes of physical attractiveness are gendered. Thus, we conducted a systematic review to determine to what extent and how the socioeconomic outcomes of physical appearance in labor markets are gendered. A total of 58 articles were reviewed after searching through five databases and identifying relevant articles. The results show that, in general, more attractive individuals are socioeconomically favored, which is true for both men and women. The number of studies that claim that attractiveness is more beneficial for women is almost equal to the number of studies that claim it is more beneficial for men. Moreover, while the socioeconomic outcomes for men are somewhat consistent, the outcomes for women appear to be more inconsistent; only women appear to be both rewarded and penalized for being attractive. Therefore, we conclude that contextual factors play a greater role in attractiveness-related outcomes, especially for women, than previously assumed.

Introduction

Social interactions are influenced by physical appearance, which has a significant impact on social inequality. Several decades of cross-disciplinary research have shown this to be a social fact: A good appearance benefits in a workplace and beyond, whereas not living up to standards of attractiveness is linked to severe social and economic penalties (Hamermesh Citation2011). In the era of an expanding service sector, social media, and visual culture, the importance of looking good has increased. Moreover, good looks have become a more crucial requirement for work (van den Berg and Arts Citation2019; Warhurst and Nickson Citation2001), leading to discussions about prohibiting appearance discrimination in the labor market (Hamermesh Citation2011; Mason and Minerva Citation2020). Apparently, social scientists are re-engaging with the timely topic, ‘beauty is having a moment in the social sciences’ (Mears Citation2014, p. 1130). In particular, there is a rapidly growing body of research that focuses on analyzing gendered consequences of perceived physical attractiveness. Therefore, a systematic review of the research on socioeconomic outcomes of physical attractiveness among men and women is urgently needed.

Although a layman’s understanding of appearance-related inequality relies on the idea that appearances are more important and consequential for women than for men, there is no scientific consensus regarding whether appearance-related socioeconomic inequality is gendered. In fact, most of the literature on this subject ignores the issue of gender. Hence, it is perhaps not surprising that gender has also been ignored in many previous literature reviews on physical appearance-related inequality (e.g. Anderson et al. Citation2010; Langlois et al. Citation2000). However, even the literature reviews that have considered physical appearance as a gendered source of inequality have reached conflicting conclusions. According to Hosoda et al. (Citation2003), physical appearance brings perks and penalties equally for men and women. Maestripieri et al. (Citation2017) suggested that attractiveness is more advantageous for women than for men, whereas Morrow (Citation1990) concluded that men are more likely to receive the benefits. Previous review articles (e.g. Hosoda et al. Citation2003; Langlois et al. Citation2000; Maestripieri et al. Citation2017) relied upon two competing hypotheses: (a) both men and women are evenly rewarded for being attractive, or (b) outcomes of attractiveness are gendered.

We commenced this systematic review to provide an up-to-date summary of the gendered outcomes of physical attractiveness in the labor market. This allowed us to fill in the gaps of previous reviews on this subject. Our review focuses on quantitative studies that provide a comparison of socioeconomic outcomes for physical attractiveness based on gender (including cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, as well as experimental studies, both lab-based and field experiments). We operationally define the outcomes of physical attractiveness as socioeconomic factors, including income, salary, hiring, tips, electoral votes, and career success.

The review is guided by the following question: To what extent and how are the socioeconomic outcomes of physical appearance gendered in working life? We conducted a systematic review of previous studies that compared work–related socioeconomic outcomes of physical appearance for men and women. After briefly discussing theoretical approaches to gender and attractiveness and introducing past literature reviews, the selection criteria and data collection of this review are explained. Next, we provide an overview of the included studies and show how literature on the topic has not only increased in number, but has also become more global and based on more realistic and comprehensive data. We demonstrate how research on socioeconomic (dis)advantages of attractiveness has been heavily concentrated in the U.S. before the 2010s, but has dramatically increased in Europe over the past ten years. We then discuss what these studies can tell us about the genderedness of physical appearance-related inequality in working life. According to our systematic review, attractiveness seems more consistently beneficial for men than for women. For women, attractiveness is not a universal asset. According to some studies in our review, attractiveness appears to be detrimental for women in some instances, but not for men. We conclude by proposing several key ways through which future studies – both quantitative and qualitative – can better understand the gendered economic outcomes of physical appearance and develop research designs and measurements to better capture the complexities of physical appearance-related inequalities.

Theoretical approaches to (gendered) outcomes of attractiveness

General approaches: attractiveness as a universal asset

Much of the current literature on physical appearance and socioeconomic inequality assumes that good looks are a universal good (Anderson et al. Citation2010; Hakim Citation2010; Hamermesh Citation2011); overall, beauty is considered as a positive quality, whose evaluations are universally shared and its consequences are generally positive (Mears Citation2014). Many economists, political scientists, social psychologists, and scholars of social stratification have drawn on this perspective of attractiveness as a universal good (Berggren et al., Citation2010; Jæger Citation2011; Sala et al. Citation2013; Wolbring and Riordan, Citation2016).

In economistic explanations, the main mechanism through which beauty is believed to confer benefits is related to preferences; employers, customers, and coworkers alike prefer beautiful people (Hamermesh Citation2011; Mobius and Rosenblat Citation2006; Rosenblat Citation2008). These preferences for beautiful people add up to social and economic rewards for attractive people, and penalties for unattractive people. This is called taste-based discrimination (Hamermesh Citation2011). The taste-based perspective is general and descriptive rather than explanatory, as the source of these preferences is rarely explained or questioned (Maestripieri et al. Citation2017). There have, however, been debates as to the extent to which the so-called beauty premia have to do with attractive people having more confidence as a result of being preferred in different situations throughout life (Mobius and Rosenblat Citation2006), or attractive people being more intelligent (Kanazawa Citation2011; Kanazawa and Still Citation2018), better negotiators (Rosenblat Citation2008), or whether the preferences indeed cause employees to be more productive in certain fields of work where, for example, customer preferences are crucial for productivity (Biddle and Hamermesh Citation1998; Hamermesh and Biddle Citation1994). Furthermore, economics-inspired analyzes tend to draw upon evolutionary explanations and social psychological research on stereotypes in order to explain the origin of preferences.

Evolutionary psychologists go the furthest in explaining preferences for beautiful people. Evolutionary approaches claim that the preference for beautiful people is a result of deeply ingrained dispositions stemming from the evolutionary role of attractiveness in selecting mates for successful reproduction (Buss et al. Citation1990). Some claim that facial attractiveness has intrinsic value and indicates reproductive quality (Maestripieri et al. Citation2017). Specifically, evolutionary-based research suggests that individuals’ brains contain flexible and advanced systems, which help them to make adaptive responses to (non-)attractive faces. These systems aim to maximize the benefits of choosing not only mates, but also other social partners with whom to co-operate, such as in context of labor market. (Little et al. Citation2011.)

Research in social psychology proposes that beauty is advantageous because people associate it with other desirable traits, such as trustworthiness, sociability, and intelligence. This mechanism is often referred to as ‘what is beautiful is good’ or attractiveness stereotype, and sometimes the halo effect (Eagly et al. Citation1991; Langlois et al. Citation2000). In sociology, beauty has been considered a diffuse status characteristic, which signals status in a similar manner to other forms of status generalization, such as sex or race (Webster and Driskell, Citation1983; Frevert and Walker Citation2014; Wolbring and Riordan Citation2016). These approaches have been complemented by expectation states theory (Ridgeway et al. Citation1985, Correll and Ridgeway Citation2006), which suggests that status characteristics and stereotypes are based on widely shared cultural beliefs that shape people’s expectations of themselves and others, and subsequently shape their actions, regardless of whether they personally endorse cultural beliefs (Ridgeway Citation2001).

Overall, the predominant perspectives in this line of research indicates that attractiveness is a universally appreciated and rewarded property. Latently, these considerations also suggest that unattractiveness – or plainness or homeliness, as it is often euphemized in the literature (Hamermesh Citation2011) – is penalized irrespective of gender. Thus, we can hypothesize that the consequences of attractiveness are not gender-specific.

Gendered approaches: attractiveness as a gendered form of inequality

Other hypotheses on how physical appearance unequalizes individuals suggest that physical appearance might be associated with unequal outcomes for people depending on their gender – or sex, as proposed by evolutionary psychologists. They claim that the central role of physical appearance in mate selection accounts for the economic and social outcomes of beauty (Buss et al. Citation1990). Thus, such evolution-based explanations suggest that gender matters, as male and female mating motivations and strategies differ by nature (Maestripieri et al. Citation2017). According to Buss (Citation1989), attractiveness is more consequential for women, since their fertility and ‘reproductive value’ are more important than men’s. Furthermore, evolutionary psychologists propose that the consequences of attractiveness are affected by interpersonal competition, particularly intrasexual competition among women who are considered envious of other women’s appearances, thus seeking to undermine attractive women’s success (Ruffle and Schtudiner Citation2015). In summary, certain evolutionary perspectives suggest that beauty premiums should exist, particularly in interactions between opposite sexes, and biases might be more pronounced for women (Maestripieri et al. Citation2017).

According to sociologists and social psychologists, too, the socioeconomic outcomes of attractiveness might be gendered. In sociology, it is well understood that attractiveness as a status characteristic intersects with other status characteristics (Monk et al. Citation2021). Thus, the consequences of attractiveness may differ, for example between men and women, because of the way stereotypes linked with attractiveness interact with stereotypes about gender. Notably, scholars who draw on gender stereotypes, especially the lack-of-fit model (Heilman Citation1983), propose that stereotypes related to physical appearance affect men and women differently because attractiveness enhances perceptions of femininity. An attractive woman is considered more feminine, and assumed by employers to be unfit for jobs that are stereotyped as masculine. Conversely, unattractiveness might increase the chances of a women being considered fit for jobs stereotyped as masculine, since unattractive women are considered to be less ‘typically’ feminine, and therefore more suited for a masculine role. This explanation is sometimes referred to as the ‘beauty is beastly’ effect (for example, Heilman and Saruwatari Citation1979). Although scholars drawing on gender stereotypes implicitly rely on universal standards of attractiveness, the consequences of attractiveness are believed to be contingent on other relevant status characteristics and depend on context, including the occupational field’s gender type. Because of the intimate connection between beauty and femininity, gender stereotype approaches suggest that the consequences of attractiveness are more varied for women than for men. Moreover, recent research has shown that the returns of attractiveness vary across different categorical combinations of gender and race (Monk et al. Citation2021).

Recent research in sociology, social psychology, and organizational studies has explicitly questioned the universal logic related to beauty and its positive outcomes, particularly regarding socioeconomic outcomes for women. This line of inquiry draws on Bourdieu’s (Citation1984) understanding of cultural capital, as well as feminist theorizing, most notably supplementing Hochschild’s (Citation1983) notion of emotional labor with a sister concept: aesthetic labor. From this perspective, many aesthetic standards are a result of culturally embedded processes of evaluation, and the value of attractiveness is negotiated within social fields with particular power constellations (Kukkonen Citation2021; Mears Citation2014). Research has shown that beauty standards are not universally shared, but multiple tastes are expressed based on several evaluative repertoires. Importantly, women are more easily evaluated based on strict aesthetic standards than men (Kuipers Citation2015).

Furthermore, this approach views beauty not only as a natural gift or something purely genetic, but also as something that is actively negotiated and ‘done’. The labor of beauty is highly gendered; feminist scholars has shown how, in everyday interactions, gender is often presumed, made, and presented based on physical appearance (Bartky Citation1990; Bordo Citation1993; Elias et al. Citation2017; Wolf Citation2002). Specifically, femininity is achieved through meticulous work on the body (Kwan and Trautner Citation2009). In their professional lives, aesthetic laborers are expected to present particular femininities and masculinities (Barber Citation2016; van den Berg Citation2019). However, even though women are expected to work more on their appearances than men (Sarpila et al. Citation2020), they are not necessarily rewarded for this effort. Mears has shown how men use attractive female bodies for their own status projects, whereas women themselves may be stigmatized by the benefits of attractiveness (Mears Citation2015; Citation2020). Indeed, strict social norms regulate the use of one’s physical appearance in order to gain socioeconomic advantage, particularly for women (Kukkonen et al. Citation2018; Sarpila et al. Citation2020). This line of research suggests that attractiveness may not always benefit women.

Therefore, based on previous research on beauty and gender, we hypothesize that socioeconomic consequences of attractiveness are primarily gendered. Next, we examine how previous systematic reviews have accounted for gender in their analyzes.

Gaps in the previous reviews

Early psychological research reviews on the physical attractiveness stereotype have concluded that people tend to attribute more positive characteristics to attractive individuals, both women and men (Eagly et al. Citation1991; Feingold Citation1992). In their meta-analysis, Langlois et al. (Citation2000) examined whether the attractiveness stereotype mattered for men and women in more realistic research settings. They found no differences based on gender. The lack of gender differences may be due to the fact that the majority of existing research does not distinguish between men and women in the data analysis, or analyzes only one gender. (Langlois et al. Citation2000.)

While Langlois et al. (Citation2000) concluded that attractiveness strongly impacts judgments of occupational competence in actual interactions, Hosoda et al. (Citation2003) furthered this knowledge by conducting a meta-analysis of attractiveness bias in simulated employment contexts. Moreover, Hosoda et al. (Citation2003) included the results from a larger number of studies (27), and used a broader set of job-related outcomes, including selection, performance evaluation, and hiring decisions. Additionally, the authors particularly focused on examining gender effects. They found no gendered differences in employment situations. They concluded that physical attractiveness was always an asset for both men and women alike, regardless of the job for which they applied. According to their review, the attractiveness effect varied depending on the research design. The authors disclosed that a potential limitation of their meta-analysis was that they only included experimental studies and were unable to infer the outcomes of non-experimental studies (i.e. calculating the external validity of their research).

In one of the most recent reviews on the topic, Maestripieri et al. (Citation2017) examined the effect of gender of the raters. Focusing on labor market analyzes and laboratory studies with experimental economic games, the authors analyzed 17 studies that pay particular attention to the impact of opposite-sex versus same-sex social interactions. The outcomes seem to vary according to opposite-sex and same-sex logic, women are likely to disfavor attractive women (same-sex social interactions), whereas men in general are prone to favor attractive women (opposite-sex social interactions). According to the researchers, their review supported an evolutionary psychological understanding in which attractive individuals are favored in opposite-sex interactions as they are regarded as desirable potential mates, whereas attractive individuals appear as sexual competitors in same-sex interactions. Indeed, the review argues that sexual attraction and mating motives explain the unequal outcomes of attractiveness. The finding that women are more likely to experience attractiveness-related outcomes compared to men is presumed to be due to the overrepresentation of men in positions of power, that is, if a male employee has the opportunity to hire an attractive female, his mating motives are activated despite his will and intentions (Maestripieri et al. Citation2017: 10). According to this view, man has two brains: one that thinks rationally, and another carnal, primal ‘penis brain,’ which operates in contrast to the man’s rational, cerebral thoughts (Potts Citation2001). Overall, it is worth considering the setup used by Maestripieri et al. and their inclusion criteria used to reach such results.

Beyond these more systematic reviews, certain more narrative literature reviews are also worth noting. Anderson et al.’s (Citation2010) narrative review of beauty perks and penalties touched on gender differences. The authors claimed that, although women receive demands to pay a high price for beauty, looks may also provide them with symbolic, social, and material wealth. Although the authors attempted to discuss the outcomes of physical appearance from a gender perspective, they failed to actually review the gendered nature of outcomes.

Sierminska and Liu (Citation2015) reviewed literature on the effect of physical attractiveness on labor market outcomes. They discussed potential explanations for the effect, as well as gender differences and consistency of the findings across cultures. Instead of adopting a systematic approach, the authors relied on selected findings – mostly from economics – without explaining the selection process. Their findings lead them to assume that men have a greater beauty premium than women. Women are less likely, overall, to participate in the labor market and more likely to stay at home, which could explain the gender differences. The authors suggested (based on Hamermesh Citation2011) that the disincentives of less-than-average looks on the labor market may lead women who are less attractive to opt out. Conversely, attractive women self-select into the labor force. Hence, the female labor force is generally more attractive than the male labor force, indicating that there is less variation in attractiveness, and therefore, a smaller beauty premium for women. In light of converging gender roles, the authors hypothesized that the beauty-premium gender gap is decreasing. Alas, the authors did not discuss, let alone test, this hypothesis in conjunction with their comparisons of the (gendered) effect of beauty on wages across various countries. They reported that, apart from Luxembourg, attractiveness was rewarded in most of their selected country findings, consisting of nine studies. The highest beauty premium was found in Australia and China, especially for women.

Overall, previous literature reviews on the gendered outcomes of physical appearance have come to conflicting conclusions; some find no gender differences (Eagly et al. Citation1991; Hosoda et al. Citation2003; Feingold Citation1992; Langlois et al. Citation2000), one suggests that attractiveness is more beneficial for women than for men (Maestripieri et al. Citation2017), and another presumes that attractiveness is more beneficial for men than for women (Sierminska and Liu Citation2015). These reviews illustrate their authors’ highly variable understanding of gender: some interpret gender in terms of sex and mating, and appear to take hegemonic masculine sexual subjectivity for granted (Maestripieri et al. Citation2017), whereas others refer to gender roles in a rather loose manner (Hosoda et al. Citation2003; Sierminska and Liu Citation2015). Furthermore, previous reviews have included a limited number of studies (the most comprehensive being Hosoda et al.’s [Citation2003] review of 27 studies), and the reviewed studies largely lean towards less realistic experimental methodologies rather than field experiments. Whereas Hosoda et al. (Citation2003) suggested that the outcomes of attractiveness may vary based on the research design, previous reviewers have neglected to analyze this. Furthermore, Sierminska and Liu (Citation2015) discussed how the effects of physical appearance might differ worldwide, but previous reviews have not analyzed how the gendered outcomes of physical attractiveness vary between countries or cultural contexts.

Therefore, we take a gender perspective to systematically analyze significantly more studies (58) than previous reviews, including and comparing both experimental and real-life studies. Furthermore, in contrast to previous reviews, we also analyze how results vary according to research design, culture, and context. In line with previous literature reviews and theoretical accounts on the topic, we also rely on the following hypotheses: (a) both men and women are rather evenly rewarded for being attractive; (b) outcomes of attractiveness are gendered.

Methods

Search strategy, inclusion criteria, and data extraction

Our systematic review was conducted using several search engines, including EBSCO, Scopus, ProQuest, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. We conducted the searches in three waves. The first search wave was conducted on October 1 and 2, 2019, using EBSCO, Scopus, and ProQuest. The second wave was conducted on October 18, 2019 using Web of Science. After screening the results of the first and second search waves, we noticed that our searches had not managed to capture certain relevant articles that we were aware of. Thus, the third search wave also included additional searches using Google’s related-articles search for such relevant articles (Anderson et al. Citation2010; Hamermesh and Biddle Citation1994; Harper Citation2000; Liu and Sierminska Citation2014; Mobius and Rosenblat Citation2006).

Our search string (see Appendix A) was adjusted for each search engine; however, the search contents were consistently maintained. A major challenge in the searches was to find all relevant studies, while limiting the results for efficient screening. Thus, we consulted an information specialist from the university library to construct an efficient search string. After this appointment, we achieved our goal, with the exception of Google Scholar, which yielded 1,100,000 results. After screening the first 100 results of the Google search, the number of relevant results dropped dramatically, and we decided to include only the first 1,000 results in order of relevance. The details of our initial bibliographic search are presented in Appendix A.

In the first phase of article selection, two authors independently screened the search results by reading their titles. In the first round, we selected all titles that seemed to be vaguely related to the subject and potentially met the inclusion criteria (). The search on the Web of Science was an exception; we only included unique articles that were not found by the other search engines in the first wave of the search. After collecting the titles and removing duplicates, we obtained 504 articles that passed the first phase of screening.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

In the second screening, two reviewers independently read the abstracts of the selected 504 articles. Both reviewers were advised to include rather than exclude articles if they were uncertain whether the abstract met the predetermined inclusion criteria. After both reviewers had screened the abstracts, a third reviewer compared the choices of the two and made a final decision regarding which articles were eligible for data extraction. Finally, 101 articles met the criteria.

Before delving into reading the articles, we created a data extraction table to gather the information in a more condensed and easily comparable format. The columns in the extraction table were as follows:

article name

country of the data

total number of participants (men, women, other)

possible name and year of the data

sample characteristics/population

short outline of the study

method

how attractiveness was measured

what fields or occupations were studied

type of outcome

main results

other possible remarks

Independently, two researchers extracted each article. All authors participated in the extraction process. The results from the two extractions were then compared. In case of mistakes or conflicts, the reviewers discussed and resolved them together. It should be noted that not all studies provided information for all columns. In some cases, the country or year of the data was missing, and if that information could not be deduced, we left blanks in the extraction table.

Our inclusion criteria were not met by several studies during the extraction process, leading us to discard them. Some of the studies discarded were clearly unsuitable for our study, such as those with only either women or men as their subjects. Others, however, revealed ambiguities in our inclusion criteria, which we have discussed below.

As a result of careful consideration of the interpretation of our inclusion and exclusion criteria, we had lengthy discussions regarding two of our inclusion criteria, namely ‘attractiveness (or beauty) as a measurement of appearance’ and ‘labor market-related socioeconomic outcomes’. First, the manifold and sometimes imaginative ways in which previous research has measured attractiveness posed questions. Initially, we considered including only studies that measured attractiveness based on facial photos that were evaluated in terms of attractiveness by several raters. However, this would have excluded some of the most-cited studies on the subject (e.g. Hamermesh and Biddle Citation1994), which, among many others, employed data from a longitudinal study in the United States called Add Health. In Add Health, attractiveness was measured by a single interviewer visiting respondents’ homes (Monk et al. Citation2021). Thus, instead of evaluating respondents’ attractiveness based on facial photographs, the interviewer establishes their rating on a general, bodily impression of respondents’ appearance. We finally included all studies that used attractiveness or beauty as a measure, regardless of whether the measurement was based on facial impressions or impressions based on more general bodily attractiveness. Appendix B discusses in detail the ways in which included articles measured attractiveness.

Second, when applied to actual research papers, the criterion for labor market-related socioeconomic outcomes proved to be ambiguous. One question that emerged was whether to include studies on student ratings of teachers (e.g. Hamermesh and Parker Citation2005; Riniolo et al. Citation2006; Wolbring and Riordan Citation2016). Although some studies (Kaun Citation1984; Moore et al. Citation1998) have stated that student ratings may have an indirect impact on teachers’ salaries, we decided to exclude these because there is no clear evidence of a causal relationship between the two variables. Similarly, we excluded studies that used academic success as an outcome (Gheorghiu et al. Citation2017). Additionally, it was necessary to determine whether to include experimental laboratory studies that utilized game theoretical designs, ultimatum games, or bargaining tasks (e.g. Deryugina and Shurchkov Citation2015; Solnick and Schweitzer Citation1999; Quereshi and Kay Citation1986). There was concern over the feasibility of these research designs in simulating real-life outcomes. Nevertheless, we included all game studies that concerned working life contexts. Moreover, we debated the inclusion of multiple studies that measured the relationship between physical attractiveness and electoral success, both in political and corporate elections (e.g. Berggren et al. Citation2010; Geiler et al. Citation2018; Jäckle and Metz Citation2017). We discussed whether electoral success could be viewed as a socioeconomic outcome, and finally decided to include such studies, rationalizing our decision to view political and corporate management positions as usually paid jobs, thus comparable to occupational hiring. Even people who are not politicians by profession often receive monetary remuneration, for instance, for attending meetings. Previous research on electoral outcomes has also been related to the literature concerning appearance premiums in the labor market (e.g. Berggren et al. Citation2010). Lastly, we discussed the inclusion of several studies (Duarte et al. Citation2012; Gonzalez and Loureiro Citation2014; Jenq et al. Citation2015) that used loans as the outcome. The consensus resulted in ruling out personal loans, but including studies on company loans, which are not fully private loans, but are concerned with working life and are applied for not as an individual but in an occupational role. Finally, 58 studies matched our inclusion criteria.

Data analysis

Descriptive outlook on the selected studies

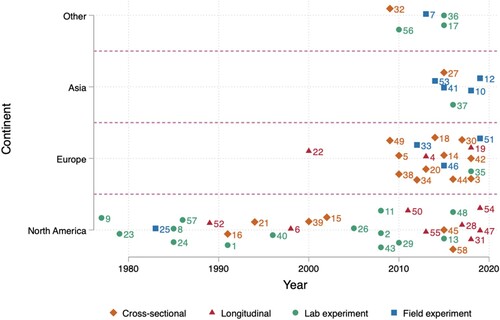

provides an overview of the included studies and shows, first, how the majority of studies (64%) were published in 2010 or later. This implies that plenty of research on gender differences in the economic outcomes of physical appearance in working life has been conducted since the publication of previous literature reviews on the topic. Second, until 2010 almost all studies on the topic have been conducted in North America, mainly the U.S. Since then, studies from Europe and Asia, in particular, have increased, and several studies have also been conducted in Australia and South America. Africa was the only continent where we did not find any research that met our inclusion criteria. Third, recent research has employed more non-experimental designs than earlier studies. Considering these three aspects in the overall trends in our data, we should update our current understanding of the subject. Furthermore, it is worthwhile to consider whether the data employed in earlier reviews were biased in favor of studies that employed experimental designs in the US. Research from the 2010s adds cultural and methodological diversity to the pool of research, allowing us to assess the consistency of the logics of beauty in working life.

Figure 1. Overview of included studies by study type, year of publication, and continent. Number labels refer to article ID, see Appendix C.

shows how different socioeconomic outcomes were measured in these studies. Often, the outcomes were related to recruitment processes (e.g. the likelihood of hiring, providing recommendations for hiring, or rating and ranking the applicants on their hireability) and different monetary measurements, including hourly, monthly, and yearly incomes as well as tips in service jobs. Moreover, electoral success was a commonly used measurement, and included both political (communal and national) and corporal elections, such as elections for corporate directors (Geiler et al. Citation2018) or for officers in an association (Hamermesh Citation2006). In addition, there were some studies that did not fit into these categories. These studies measured, for example, occupational status or standing (Anýžová and Matějů Citation2018; Sala et al. Citation2013), competence (e.g. evaluations of career progress and capability; Heilman and Stopeck Citation1985), or speed of obtaining a loan in different sectors of the labor market (Jenq et al. Citation2015).

Table 2. Measures of socioeconomic outcomes in the studies.

depicts the occupations examined in the articles. The occupations were first classified using the 10-pointed ISCO-08 classification and then further grouped into four categories containing low – and high-skilled white- and blue-collar occupations. Since many studies examined more than one occupation, the numbers and percentages in the table do not add up to our total N of 58 or 100%. shows that most of the research on the gendered economic outcomes of attractiveness that has taken occupation into account has focused on white-collar jobs. There is a clear imbalance in the occupations studied, marked by the near total absence of studies on blue-collar jobs.

Table 3. Occupations examined in the studies reviewed, categorized according to the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO-08).

Gendered outcomes

Next, we discuss the distribution of appearance-related socioeconomic outcomes in labor markets between men and women. We begin by introducing the general results of our analysis.

shows the number of reviewed studies in which various conditions were supported. In coding the results, we specifically examined the paper’s gender comparisons. If a paper included, for example, stepwise models we looked at the model which was the most comparable to models in other papers. Apart from our interpretations of the models, we also took into account the authors’ interpretation. The total number of results is greater than the number of studies included because many studies have provided several results that were not mutually exclusive. For example, if attractiveness was found to be generally beneficial for both genders, but more to men than to women, the result was marked in both the second (‘attractiveness more beneficial for men’) and third columns (‘attractiveness beneficial for both’). According to this count of results, there are no clear differences between genders in the benefits associated with attractiveness. Instead, a similar number of studies have supported the claim that women benefit from attractiveness more than men, as there is support for the claim that men benefit more than women. In most cases, we find evidence to support the claim that attractiveness is socioeconomically beneficial for both men and women.

Table 4. Distribution of gendered outcomes of articles (N = 58) reviewed.

Thus, we find that attractiveness is not exclusively a benefit for women, but there is evidence that it is an asset for men. Interestingly, the most obvious gender differences are observed in cases where attractiveness acts as a detrimental property, often referred to as the ‘beauty is beastly’ effect (Heilman and Saruwatari Citation1979). Seven studies have found this effect for women, but no study has detected it for men. Accordingly, attractiveness seems to be more coherently an asset for men, whereas the outcomes of attractiveness are more unsystematic for women.

A limited number of studies have focused on the effects of being less attractive (often referred to as unattractiveness or plainness). Hence, we can say less about the gender differences in the effects of unattractiveness or plainness. Overall, most studies focusing on plainness found it to be linked to negative outcomes for either one or both genders (15 papers in total). According to three studies, plainness may be beneficial either for men or women, and none of the studies reported it to be generally rewarding. Moreover, Heilman and Saruwatari (Citation1979) found unattractiveness to be more beneficial for women in managerial jobs in terms of hiring and salary recommendations, as well as qualification evaluations. The same result was replicated in a study by Shahani-Denning et al. (Citation2010), but only in their U.S. sample, not in India, where they compared the U.S. results. In contrast, Lee et al. (Citation2015) found that unattractiveness may be beneficial for men instead of women in situations where the decision maker expects them to compete with the evaluated person in the future. In short, all studies that found plainness to be beneficial for either gender considered more situational logics involved, implying that the process through which appearance-related inequalities emerge is multidimensional.

As a supplementary analysis, we inquired into possible patterns behind the inconsistent outcomes in terms of gender by analyzing in more detail the studies that found attractiveness to be beneficial either for men (20 studies) or women (19 studies), as well as studies that found attractiveness to be more detrimental for women (seven studies). We tabulated these studies by country, year, study type, occupational categories, outcomes, as well as based on ratings and pool of raters. The results of this supplementary analysis can be found in Appendix D. We did not find clear patterns that could explain the discrepancies in results. Our analysis revealed that the majority of studies that reported the existence of beauty penalties for attractive women were conducted in the U.S. (and only one in Europe) and utilized an experimental design. It is possible that these types of lab experiments, based on first impression and stimulus-reaction schemes, reinforce gender stereotypes related to attractive women in particular (Kuwabara and Thébaud Citation2017). Moreover, six European studies found attractiveness to be more beneficial for women, whereas only three reported attractiveness to be more beneficial for men. However, further research is required to draw conclusions about the existence of cultural differences in the gendered outcomes of attractiveness.

Discussion

This study provides a detailed and up-to-date summary of the gendered socioeconomic outcomes of physical attractiveness in the labor market. Over the past decade, researchers from Europe have become increasingly interested in physical attractiveness-based inequalities, besides those from the U.S. However, the results have often been scattered in terms of gender. Similar to previous literature reviews, we also relied on two competing hypotheses: (a) both men and women are universally rewarded for being attractive; (b) outcomes of attractiveness are gendered.

First, we found that attractiveness is generally socioeconomically beneficial for both men and women. A very common conclusion in the studies that we reviewed was there are no significant gender difference in socioeconomic outcomes of attractiveness in working life. Indeed, we found no evidence that attractiveness would be more beneficial particularly for women, as lay understanding suggests. Instead, we found an almost equal amount of studies indicating that attractiveness is more beneficial for men as we found studies reporting that attractiveness is more beneficial for women.

Second, we found that the outcomes of attractiveness are gendered in that it is more consistently beneficial for men than for women. For women, attractiveness appears to be detrimental in certain cases, which is not the case for men. Thus, we conclude that attractiveness is a rather universally beneficial for men, whereas it may be more context-dependent for women. In other words, both genders generally benefit from attractiveness, but only women get penalized for being attractive. Women are expected to constantly engage in aesthetic labor to improve their looks (Elias et al. Citation2017), yet attractiveness entails risks of not only stigma (Tseëlon Citation1992), but also socioeconomic penalties on labor markets. The fact that women walk such a tightrope means that we can hardly consider attractiveness an individual characteristic or form of capital that universally yields gender-neutral beauty premia. Thus, our results partially support the second hypothesis regarding the outcomes of attractiveness being gendered.

Several papers we reviewed straightforwardly drew from very empirical and often theoretically void (Maestripieri et al. Citation2017) research on beauty premia, assuming that attractiveness is a universal asset that automatically confers benefits to individuals (Mears Citation2014). The inconsistencies in the results of this research in terms of gender, however, highlight that this approach simply does not suffice for understanding and explaining appearance-related labor market inequalities. It is plausible that context and power relations play a role in determining attractiveness-related outcomes: Perhaps unequal outcomes relate as much to contextual power relations as to individual characteristics. In Bourdieusian terms, the structure of the social field matters (Green Citation2014; Kukkonen Citation2021). Additionally, quantitative research on appearance-related inequality could benefit significantly from engaging with the literature on aesthetic labor, which underscores how appearance-related inequalities are shaped in social interaction in particular labor market contexts, where the power relations tend to be skewed, such as in terms of social class, gender, age, and race (e.g. Boyle and Keere Citation2019, Wissinger Citation2012, Walters Citation2018).

The reviewed quantitative research on the socioeconomic outcomes of attractiveness largely glosses over power relations. Despite focusing on socioeconomic inequality, the research field is surprisingly blind to forms of inequality, both in terms of status and class. For example, it is striking that blue-collar occupations were barely represented in the studies we reviewed in this paper. This not only causes a middle class bias, but may also distort results in terms of gender, as blue-collar occupations tend to be more sex-typed than white-collar jobs.

Generally, more recent studies included in our systematic review acknowledged different social categorizations better than older studies, for example, by employing comparative study settings and including more detailed analyzes of different statistical interactions. If studies increasingly examine differences in the outcomes of attractiveness between social groups, future studies could be conducted to review the interplay between attractiveness and, for example, age and race in shaping labor market inequalities in different fields of work or different cultures. However, the potential for drawing together research results and comparing results is undermined by attractiveness being measured in numerous ways, on countless different scales, and a lack of uniformity in analysis. With the overwhelming focus on the positive outcomes of attractiveness in the literature, there is a tendency to contrast some groups defined as ‘attractive’ to ‘others,’ rather than examining outcomes of unattractiveness, or comparing different levels of attractiveness. This limits our understanding of appearance-based inequality (Griffin and Langlois Citation2006; Kanazawa and Still Citation2018).

Considering that attractiveness in itself is a classed, gendered, racist, and ageist concept (Craig Citation2002, Jha Citation2015, Kuipers Citation2015, Kwan and Trautner Citation2009), exploring these social categorizations may help us better understand appearance-related inequality. For example, a recent study by Monk et al. (Citation2021) found that the returns of attractiveness vary depending on the intersections of race and gender, with Black women gaining the most advantage from attractiveness, while facing the most disadvantage from unattractiveness. Such intersectional – or even infra-categorical (Monk Citation2022) – thinking and methods of analysis could be key to understanding the dynamics of appearance-related inequalities. Current research often takes the role of attractiveness for granted, thus contributing to the naturalization of attractiveness-related inequality. More efforts should be made to unpack the ‘black box’ of attractiveness (cf. Mears Citation2014), and focusing on cues of categories, as well as typicality (Monk Citation2022). Therefore, complementary measures should be developed and studied to capture, for example, how styles of clothing, hair, posture, facial expressions, grooming, and living up to occupational appearance expectations produce unequal outcomes. We encourage applying innovative research designs to solve inconsistencies from previous research and to increase our understanding of gendered appearance-related inequalities in working life. In a visually oriented social world, these inequalities will rapidly deepen unless they are better recognized and understood.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Tobias Wolbring for his meticulous, perceptive, and patient guidance, which helped us revise the paper.

Data availability

The data extracted by the researchers is publicly and permanently available at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7852214.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Iida Kukkonen

Iida Kukkonen works as a senior researcher at the Unit of Economic Sociology, University of Turku. Her research interests revolve around physical appearance, inequality, gender, and consumption. In her PhD thesis, she studies gendered physical appearance-related inequalities in Finnish working life.

Tero Pajunen

Tero Pajunen is a doctoral researcher at the Unit of Economic Sociology, University of Turku. He studies appearance-related meaning-making processes and the role of physical appearance in everyday working life.

Outi Sarpila

Outi Sarpila is an economic sociologist and works as a Senior Research Fellow at the INVEST Research Flagship, University of Turku. Her research interests include themes related to physical appearance and inequalities, as well as sociology of consumption.

Erica Åberg

Erica Åberg works as a university teacher at the University of Turku. She has previously studied social norms related to physical appearance and social media. In the past few years, she has shifted her attention to different youth cultures on social media, particularly those around Nordic drill music.

References

- Abramowitz, I. and O’Grady, K. (1991) ‘Impact of gender, physical attractiveness, and intelligence on the perception of peer counselors’, The Journal of Psychology 125(3): 311–326.

- Anderson, T. L., Grunert, C., Katz, A. and Lovascio, S. (2010) ‘Aesthetic capital: a research review on beauty perks and penalties’, Sociology Compass 4(8): 564–575.

- Andreoni, J. and Petrie, R. (2008) ‘Beauty, gender and stereotypes: evidence from laboratory experiments’, Journal of Economic Psychology 29(1): 73–93.

- Anýžová, P. and Matějů, P. (2018) ‘Beauty still matters: the role of attractiveness in labour market outcomes’, International Sociology 33(3): 269–291.

- Barber, K. (2016) ‘Men wanted’, Gender & Society 30(4): 618–642.

- Bartky, S. L. (1990) Femininity and Domination: Studies in the Phenomenology of Oppression, New York: Routledge.

- Benzeval, M., Green, M. J. and Macintyre, S. (2013) ‘Does perceived physical attractiveness in adolescence predict better socioeconomic position in adulthood? Evidence from 20 years of follow up in a population cohort study’, PloS One 8(5): e63975.

- Berggren, N., Jordahl, H. and Poutvaara, P. (2010) ‘The looks of a winner: beauty and electoral success’, Journal of Public Economics 94(1–2): 8–15.

- Biddle, J. E. and Hamermesh, D. S. (1998) ‘Beauty, productivity, and discrimination: lawyers’ looks and lucre’, Journal of Labor Economics 16(1): 172–201.

- Bóo, F. L., Rossi, M. A. and Urzúa, S. S. (2013) ‘The labor market return to an attractive face: evidence from a field experiment’, Economics Letters 118(1): 170–172.

- Bordo, S. (2004[1993]) Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture and the Body, Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1984) Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Boyle, B. and Keere, K. D. (2019) ‘Aesthetic labour, class and taste: mobility aspirations of middle-class women working in luxury-retail’, The Sociological Review 67(3): 706–722.

- Buss, D. M. (1989) ‘Sex differences in human mate preferences: evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures’, Behavioral and Brain Sciences 12(1): 1–14.

- Buss, D. M., Abbott, M., Angleitner, A., Asherian, A., Biaggio, A., Blanco-Villasenor, A., Bruchon-Schweitzer, M., Ch'u, H. Y., Czapinski, J., Deraad, B. and Ekehammar, B. (1990) ‘International preferences in selecting Mates’, Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 21(1): 5–47.

- Cash, T., Gillen, B. and Burns, S. (1977) ‘Sexism and beautyism in personnel consultant decision making’, Journal of Applied Psychology 62(3): 301–310.

- Cash, T. and Kilcullen, R. (1985) ‘The Aye of the beholder: susceptibility to sexism and beautyism in the evaluation of managerial Applicants1’, Journal of Applied Social Psychology 15(4): 591–605.

- Chiang, C. I. and Saw, Y. L. (2018) ‘Do good looks matter when applying for jobs in the hospitality industry?’, International Journal of Hospitality Management 71: 33–40.

- Chiao, J., Bowman, N. and Gill, H. (2008) ‘The political gender gap: gender bias in facial inferences that predict voting behavior’, PloS One 3(10): e3666.

- Correll, S. J. and Ridgeway, C. L. (2006) ‘Expectation states theory’, in J. Delamater (ed.), Handbook of Social Psychology, Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research, Boston, MA: Springer, pp. 29–51.

- Craig, M. L. (2002) Ain’t I a Beauty Queen? Black Women, Beauty, and the Politics of Race, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Deng, W., Li, D. and Zhou, D. (2020) ‘Beauty and job accessibility: new evidence from a field experiment’, Journal of Population Economics 33: 1303–1341.

- Deryugina, T. and Shurchkov, O. (2015) ‘Now you see it, now you don’t: the vanishing beauty premium’, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 116: 331–345.

- Doorley, K. and Sierminska, E. (2015) ‘Myth or fact? The beauty premium across the wage distribution in Germany’, Economics Letters 129: 29–34.

- Duarte, J., Siegel, S. and Young, L. (2012) ‘Trust and credit: the role of appearance in peer-to-peer lending’, Review of Financial Studies 25(8): 2455–2484.

- Eagly, A. H., Ashmore, R. D., Makhijani, M. G. and Longo, L. C. (1991) ‘What is beautiful is good, but … : a meta-analytic review of research on the physical attractiveness stereotype’, Psychological Bulletin 110(1): 109–128.

- Elias, A. S., Gill, R. and Scharff, C. (2017) ‘Aesthetic labor: Beauty politics in neoliberalism’, in A. S. Elias, R. Gill and C. Scharff (eds.), Aesthetic Labor: Rethinking Beauty Politics in Neoliberalism, London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 3-49.

- Feingold, A. (1992) ‘Good-looking people are not what we think’, Psychological Bulletin 111(2): 304–341.

- French, M. (2002) ‘Physical appearance and earnings: further evidence’, Applied Economics 34(5): 569–572.

- Frevert, T. K. and Walker, L. S. (2014) ‘Physical attractiveness and social status’, Sociology Compass 8(3): 313–323.

- Frieze, I. H., Olson, J. and Russell, J. (1991) ‘Attractiveness and income for men and women in Management1’, Journal of Applied Social Psychology 21(13): 1039–1057.

- Fruhen, L., Watkins, C. and Jones, B. (2015) ‘Perceptions of facial dominance, trustworthiness and attractiveness predict managerial pay awards in experimental tasks’, The Leadership Quarterly 26(6): 1005–1016.

- Gehrsitz, M. (2014) ‘Looks and labor: do attractive people work more?’, Labour (committee. on Canadian Labour History) 28(3): 269–287.

- Geiler, P., Renneboog, L. and Zhao, Y. (2018) ‘Beauty and appearance in corporate director elections’, Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money 55: 1–12.

- Geys, B. (2015) ‘Looks good, you’re hired? evidence from extra-parliamentary activities of German Parliamentarians’, German Economic Review 16(1): 1–12.

- Gheorghiu, A. I., Callan, M. J. and Skylark, W. J. (2017) ‘Facial appearance affects science communication’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114(23): 5970–5975.

- Gonzalez, L. and Loureiro, Y. K. (2014) ‘When can a photo increase credit? The impact of lender and borrower profiles on online peer-to-peer loans’, Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance 2: 44–58.

- Green, A. I. (2014) ‘Toward a sociology of collective sexual life’, in A. I. Green (ed.), Sexual Fields: Toward a Sociology of Collective Sexual Life, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, pp. 1–23.

- Griffin, A. M. and Langlois, J. H. (2006) ‘Stereotype directionality and attractiveness stereotyping: is beauty good or is ugly bad?’, Social Cognition 24(2): 187–206.

- Hakim, C. (2010) ‘Erotic capital’, European Sociological Review 26(5): 499–518.

- Hamermesh, D. S. (2006) ‘Changing looks and changing “discrimination”: the beauty of economists’, Economics Letters 93(3): 405–412.

- Hamermesh, D. S. (2011) Beauty Pays: Why Attractive People are More Successful, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Hamermesh, D. S. and Biddle, J. E. (1994) ‘Beauty and the labor market’, The American Economic Review 84(5): 1174–1194.

- Hamermesh, D. S. and Parker, A. (2005) ‘Beauty in the classroom: instructors’ pulchritude and putative pedagogical productivity’, Economics of Education Review 24(4): 369–376.

- Harper, B. (2000) ‘Beauty, stature and the labour market: a British cohort Study’, Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 62(s1): 771–800.

- Heilman, M. E. (1983) ‘Sex bias in work settings: the lack of fit model’, Research in Organizational Behavior 5: 269–298.

- Heilman, M. E. and Saruwatari, L. (1979) ‘When beauty is beastly: the effects of appearance and sex on evaluations of job applicants for managerial and nonmanagerial jobs’, Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 23(3): 360–372.

- Heilman, M. E. and Stopeck, M. H. (1985) ‘Being attractive, advantage or disadvantage? Performance-based evaluations and recommended personnel actions as a function of appearance, sex, and job type’, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 35(2): 202–215.

- Hochschild, A. R. (1983) The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling, Berkeley: The University of California Press.

- Hosoda, M., Stone-Romero, E. F. and Coats, G. (2003) ‘The effects of physical attractiveness on job-related outcomes: a meta-analysis of experimental studies’, Personnel Psychology 56(2): 431–462.

- Jäckle, S. and Metz, T. (2017) ‘Beauty contest revisited: the effects of perceived attractiveness, competence, and likability on the electoral success of German MPs’, Politics & Policy 45(4): 495–534.

- Jackson, L. A. (1983) ‘Gender, physical attractiveness, and sex role in occupational treatment discrimination: the influence of trait and role assumptions’, Journal of Applied Social Psychology 13(5): 443–458.

- Jawahar, I. M. and Mattsson, J. (2005) ‘Sexism and beautyism effects in selection as a function of self-monitoring level of decision maker’, Journal of Applied Psychology 90(3): 563–573.

- Jenq, C., Pan, J. and Theseira, W. (2015) ‘Beauty, weight, and skin color in charitable giving’, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 119: 234–253.

- Jæger, M. M. (2011) ‘“A thing of beauty is a joy forever”? Returns to physical attractiveness over the life course’, Social Forces 89(3): 983–1003.

- Jha, M. R. (2015) The global beauty industry: Colorism, racism, and the national body, New York: Routledge.

- Johnson, S. K., Podratz, K. E., Dipboye, R. L. and Gibbons, E. (2010) ‘Physical attractiveness biases in ratings of employment suitability: tracking down the “beauty is beastly” effect’, The Journal of Social Psychology 150(3): 301–318.

- Judge, T. A., Hurst, C. and Simon, L. S. (2009) ‘Does it pay to be smart, attractive, or confident (or all three)? Relationships among general mental ability, physical attractiveness, core self-evaluations, and income’, Journal of Applied Psychology 94(3): 742–755.

- Kanazawa, S. (2011) ‘Intelligence and physical attractiveness’, Intelligence 39(1): 7–14.

- Kanazawa, S. and Still, M. C. (2018) ‘Is there really a beauty premium or an ugliness penalty on earnings?’, Journal of Business and Psychology 33(2): 249–262.

- Kaun, D. E. (1984) ‘Faculty advancement in a nontraditional university environment’, ILR Review 37(4): 592–606.

- King, A. and Leigh, A. (2009) ‘Beautiful politicians’, Kyklos 62(4): 579–593.

- Kraft, P. (2012) ‘The role of beauty in the labor market’, Ph.D. thesis, Center for Economic Research and Graduate Education, Charles University Prague.

- Kuipers, G. (2015) ‘Beauty and distinction? The evaluation of appearance and cultural capital in five European countries’, Poetics 53: 38–51.

- Kukkonen, I. (2021) ‘Physical appearance as a form of capital: Key problems and tensions’, in O. Sarpila, I. Kukkonen, T. Pajunen and E. Åberg (eds.), Appearance as Capital: The Normative Regulation of Aesthetic Capital Accumulation and Conversion, Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited, pp. 23-37.

- Kukkonen, I., Åberg, E., Sarpila, O. and Pajunen, T. (2018) ‘Exploitation of aesthetic capital – disapproved by whom?’, International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 38(3/4): 312–328.

- Kuwabara, K. and Thébaud, S. (2017) ‘When beauty doesn’t pay: gender and beauty biases in a peer-to-peer loan market’, Social Forces 95(4): 1371–1398.

- Kwan, S. and Trautner, M. N. (2009) ‘Beauty work: individual and institutional rewards, the reproduction of gender, and questions of agency’, Sociology Compass 3(1): 49–71.

- Langlois, J. H., Kalakanis, L., Rubenstein, A. J., Larson, A., Hallam, M. and Smoot, M. (2000) ‘Maxims or myths of beauty? A meta-analytic and theoretical review’, Psychological Bulletin 126(3): 390–423.

- Lee, S., Pitesa, M., Pillutla, M. and Thau, S. (2015) ‘When beauty helps and when it hurts: an organizational context model of attractiveness discrimination in selection decisions’, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 128: 15–28.

- Lee, M., Pitesa, M., Pillutla, M. and Thau, S. (2018) ‘Perceived entitlement causes discrimination against attractive job candidates in the domain of relatively less desirable jobs’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 114(3): 422–442.

- Lev-On, A. and Waismel-Manor, I. (2016) ‘Looks that Matter’, American Behavioral Scientist 60(14): 1756–1771.

- Little, A. C., Jones, B. C. and DeBruine, L. M. (2011) ‘Facial attractiveness: evolutionary based research’, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 366(1571): 1638–1659.

- Liu, X. and Sierminska, E. (2014) ‘Evaluating the effect of beauty on labor market outcomes: A review of the literature’, Luxembourg Institute of Socio-Economic Research (LISER) Working Paper Series 11.

- Lutz, G. (2010) ‘The electoral success of beauties and beasts’, Swiss Political Science Review 16(3): 457–480.

- Lynn, M. and Simons, T. (2000) ‘Predictors of male and female servers' average Tip Earnings1’, Journal of Applied Social Psychology 30(2): 241–252.

- Maestripieri, D., Henry, A. and Nickels, N. (2017) ‘Explaining financial and prosocial biases in favor of attractive people: interdisciplinary perspectives from economics, social psychology, and evolutionary psychology’, Behavioral and Brain Sciences 40: e19.

- Marlowe, C., Schneider, S. and Nelson, C. (1996) ‘Gender and attractiveness biases in hiring decisions: are more experienced managers less biased?’, Journal of Applied Psychology 81(1): 11–21.

- Mason, A. and Minerva, F. (2020) ‘Should the Equality Act 2010 be extended to prohibit appearance discrimination?’, Political Studies 70(2): 425–442.

- Maurer-Fazio, M. and Lei, L. (2015) ‘As rare as a panda’, International Journal of Manpower 36(1): 68–85.

- Mavisakalyan, A. (2018) ‘Do employers reward physical attractiveness in transition countries?’, Economics & Human Biology 28: 38–52.

- Mears, A. (2014) ‘Aesthetic labor for the sociologies of work, gender, and beauty’, Sociology Compass 8(12): 1330–1343.

- Mears, A. (2015) ‘Girls as elite distinction: the appropriation of bodily capital’, Poetics 53: 22–37.

- Mears, A. (2020) Very Important People: Status and Beauty in the Global Party Circuit, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Mobius, M. M. and Rosenblat, T. S. (2006) ‘Why beauty matters’, American Economic Review 96(1): 222–235.

- Monk, E. P. (2022) ‘Inequality without groups: contemporary theories of categories, intersectional typicality, and the disaggregation of difference’, Sociological Theory 40(1): 3–27.

- Monk, E. P., Esposito, M. H. and Lee, H. (2021) ‘Beholding inequality: race, gender, and returns to physical attractiveness in the United States’, American Journal of Sociology 127(1): 194–241.

- Moore, W. J., Newman, R. J. and Turnbull, G. K. (1998) ‘Do academic salaries decline with seniority?’, Journal of Labor Economics 16(2): 352–366.

- Morrow, P. C. (1990) ‘Physical attractiveness and selection decision making’, Journal of Management 16(1): 45–60.

- Nicklin, J. and Roch, S. (2008) ‘Biases influencing recommendation letter contents: physical attractiveness and gender’, Journal of Applied Social Psychology 38(12): 3053–3074.

- Oreffice, S. and Quintana-Domeque, C. (2016) ‘Beauty, body size and wages: evidence from a unique data set’, Economics & Human Biology 22: 24–34.

- Parrett, M. (2015) ‘Beauty and the feast: examining the effect of beauty on earnings using restaurant tipping data’, Journal of Economic Psychology 49: 34–46.

- Patacchini, E., Ragusa, G. and Zenou, Y. (2015) ‘Unexplored dimensions of discrimination in Europe: homosexuality and physical appearance’, Journal of Population Economics 28(4): 1045–1073.

- Patel, P. and Wolfe, M. (2021) ‘In the eye of the beholder? The returns to beauty and IQ for the self-employed’, Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 15(4): 487–525.

- Paustian-Underdahl, S. and Walker, S. L. (2016) ‘Revisiting the beauty is beastly effect: examining when and why sex and attractiveness impact hiring judgments’, The International Journal of Human Resource Management 27(10): 1034–1058.

- Potts, A. (2001) ‘The man with two brains: hegemonic masculine subjectivity and the discursive construction of the unreasonable penis-self’, Journal of Gender Studies 10(2): 145–156.

- Poutvaara, P., Jordahl, H. and Berggren, N. (2009) ‘Faces of politicians: babyfacedness predicts inferred competence but not electoral success’, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 45(5): 1132–1135.

- Quereshi, M. Y. and Kay, J. P. (1986) ‘Physical attractiveness, age, and sex as determinants of reactions to resumes’, Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal 14(1): 103–112.

- Ridgeway, C. L. (2001) ‘Gender, status, and leadership’, Journal of Social Issues 57(4): 637–655.

- Ridgeway, C. L., Berger, J. and Smith, L. (1985) ‘Nonverbal cues and status: an expectation states Approach’, American Journal of Sociology 90(5): 955–978.

- Riniolo, T. C., Johnson, K. C., Sherman, T. R. and Misso, J. A. (2006) ‘Hot or not: do professors perceived as physically attractive receive higher student evaluations?’, The Journal of General Psychology 133(1): 19–35.

- Robins, P., Homer, J. and French, M. (2011) ‘Beauty and the labor market: accounting for the additional effects of personality and grooming’, Labour (committee. on Canadian Labour History) 25(2): 228–251.

- Rooth, D.-O. (2009) ‘Obesity, attractiveness, and differential treatment in hiring – A field experiment’, Journal of Human Resources 44(3): 710–735.

- Rosenblat, T. S. (2008) ‘The beauty premium: physical attractiveness and gender in dictator games’, Negotiation Journal 24(4): 465–481.

- Roszell, P., Kennedy, D. and Grabb, E. (1989) ‘Physical attractiveness and income attainment among Canadians’, The Journal of Psychology 123(6): 547–559.

- Ruffle, B. J. and Shtudiner, Z. (2015) ‘Are good-looking people more employable?’, Management Science 61(8): 1760–1776.

- Ryabov, I. (2019) ‘How much does physical attractiveness matter for Blacks? Linking skin color, physical attractiveness, and black status attainment’, Race and Social Problems 11(1): 68–79.

- Sala, E., Terraneo, M., Lucchini, M. and Knies, G. (2013) ‘Exploring the impact of male and female facial attractiveness on occupational prestige’, Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 31: 69–81.

- Sarpila, O., Koivula, A., Kukkonen, I., Åberg, E. and Pajunen, T. (2020) ‘Double standards in the accumulation and utilisation of ‘aesthetic capital’’, Poetics 82: 101447.

- Shahani-Denning, C., Dudhat, P., Tevet, R. and Andreoli, N. (2010) ‘Effect of physical attractiveness on selection decisions in India and the United States’, International Journal of Management 27(1): 37–51.

- Sierminska, E. and Liu, X. (2015) ‘Beauty and the labor market.”’, in J. D. Wright (ed.), International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, Oxford: Elsevier Science & Technology, pp. 383-391.

- Sigelman, C., Sigelman, L., Thomas, D. and Ribich, F. (1986) ‘Gender, physical attractiveness, and electability: an experimental investigation of voter biases’, Journal of Applied Social Psychology 16(3): 229–248.

- Solnick, S. J. and Schweitzer, M. E. (1999) ‘The influence of physical attractiveness and gender on ultimatum game decisions’, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 79(3): 199–215.

- Tseëlon, E. (1992) ‘What is beautiful is bad: physical attractiveness as stigma’, Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 22(3): 295–309.

- Van den Berg, M. (2019) ‘Precarious masculinities and gender as pedagogy: aesthetic advice-encounters for the Dutch urban economy’, Gender, Place & Culture 26(5): 700–718.

- Van den Berg, M. and Arts, J. (2019) ‘The aesthetics of work-readiness: aesthetic judgements and pedagogies for conditional welfare and post-fordist labour markets’, Work, Employment and Society 33(2): 298–313.

- Walters, K. (2018) ‘“They’ll go with the lighter”: tri-racial aesthetic labor in clothing retail’, Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 4(1): 128–141.

- Warhurst, C. and Nickson, D. P. (2001) Looking Good, Sounding Right: Style Counselling and the Aesthetics of the new Economy, London: The Industrial Society.

- Webster, M. and Driskell, J. E. (1983) ‘Beauty as status’, American Journal of Sociology 89(1): 140–165.

- Wissinger, E. (2012) ‘Managing the semiotics of skin tone: race and aesthetic labor in the fashion modeling industry’, Economic and Industrial Democracy 33(1): 125–143.

- Wolbring, T. and Riordan, P. (2016) ‘How beauty works. Theoretical mechanisms and two empirical applications on students’ evaluation of teaching’, Social Science Research 57: 253–272.

- Wolf, N. (2002[1990]) The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty are Used Against Women, New York: Harper Perennial.

- Wong, J. S. and Penner, A. M. (2016) ‘Gender and the returns to attractiveness’, Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 44: 113–123.

Appendix A:

Bibliographic search strategy

Appendix B:

Measuring attractiveness

Table B1. Measurements of attractiveness in the studies

There is no standard measurement of attractiveness in research, instead, studies have approached it in several different ways. The majority of studies measured attractiveness by having a panel rate unmanipulated facial photographs of real people, which ensured that each appearance was evaluated several times. Some studies digitally manipulated photographs that were checked for manipulation by a group of raters (e.g. Deng et al. Citation2020; Rooth Citation2009). Numerous studies evaluated attractiveness based on ratings on face-to-face encounters. In these cases, the evaluation of attractiveness was based on a whole-body impression, rather than a static two-dimensional facial photograph. Ratings based on real-life encounters were typically based on a rating given by an interviewer. In five studies (Cash and Kilcullen Citation1985; Lee et al. Citation2018; Lev-On and Waismel-Manor Citation2016; Maurer-Fazio and Lei Citation2015; Parrett Citation2015), the number of times each appearance was evaluated was not reported. In approximately in one-third of the studies, the pool of raters consisted of undergraduate university students. Another one-third used a more diverse sample of raters, including individuals of different nationalities (e.g. comparisons between USA and India (Shahani-Denning et al. Citation2010)), different age groups, occupational groups, or more random combinations of people (e.g. restaurant visitors (Parrett Citation2015)). In 12 studies, attractiveness was evaluated by an interviewer whose background or gender was not disclosed.

Generally, attractiveness was measured using 5-point scales (31% of studies used some type of 5-point scale), but narrower and wider scales were also used, ranging from scales of 1–3 all the way to 11-point scales. Often, only the peak numbers were verbally explicated (for example, the terms for lowest attractiveness were ‘very unattractive’, ‘homely’ or ‘not at all attractive’ and the terms for highest attractiveness were ‘very attractive’ or ‘strikingly handsome/beautiful’). Moreover, one study determined attractiveness by asking raters to select the more attractive one out of two pictures (Jäckle and Metz Citation2017). In most studies, only attractiveness was evaluated, but about one-third of the studies also measured other appearance-related characteristics, such as babyfacedness, trustworthiness, or likeability.

Appendix C:

Included Articles in Alphabetical Order

Appendix D:

Supplementary analysis

Table D1. Inconsistent gendered outcomes by country, year, study type, occupational categories, outcomes, basis of rating and pool of raters.