ABSTRACT

Much research has focused on penalties by gender, parenthood and part-time work for hiring processes or wages, but their role for promotions is less clear. This study analyzes perceived chances for internal promotion, using a factorial survey design. Employees in 540 larger German (>100 employees) firms were asked to rate the likelihood of internal promotion for vignettes describing fictitious co-workers who varied in terms of gender, parenthood, working hours as well as age, earnings, qualification, tenure and job performance. Results show that promotion chances are perceived as significantly lower for co-workers who are women (gender penalty), mothers (motherhood penalty) and part-time workers (part-time penalty). Fathers and childless men (co-workers) are not evaluated differently (no fatherhood premium or penalty), and neither does part-time employment seem to be perceived as a double penalty for male co-workers. All three perceived promotion penalties are more pronounced among female employees, mothers and part-time employees. These findings show that employees perceive differential promotion chances for co-workers which indicate actual differences due to discrimination, selective applications or structural dead-ends. Either way, perceived promotion penalties are likely consequential in guiding employee’s application behavior and hence can contribute to the persistence of vertical gender segregation in the labor market.

Introduction

Women in Europe continue being underrepresented in supervisory positions (Dämmrich and Blossfeld Citation2017; Eurofound Citation2020; Levanon and Grusky Citation2016). Two explanations for this vertical gender segregation are frequently put forward in the literature: on the one hand, self-selection into certain employment and careers; and, on the other, employers’ discrimination in hiring and promotion processes. Much research has focused on penalties for women (based on gender, parenthood and part-time work) with regard to hiring (e.g. Bertogg et al. Citation2020; Birkelund et al. Citation2022) while their role for promotions is less often investigated (Fernandez-Lozano et al. Citation2020; Sterkens et al. Citation2023). However, supervisory positions are not only accessed through hiring (initial placement) but also through internal promotions (evaluation of achievement). It might be that (i) discrimination against women also arises at later stages of their careers, for instance when selecting for senior position and that specific groups (e.g. women) (ii) are only selectively aiming at achieving a supervisory position or (iii) are sorted into jobs with low chances for internal career mobility. The combination of these factors could potentially contribute to the persistence of vertical gender segregation.

Besides the gender of an employee two interconnected characteristics are potentially conflicting with achieving or aiming at an internal promotion. First, employees becoming a mother or a father are perceived differently in terms of their perceived competence and warmth (Stereotype Content Model by Fiske et al. Citation2002). While fathers gain perceived warmth, mothers gain perceived warmth and lose perceived competence which can lead to parenthood-specific promotion penalties. Second, working part-time (e.g. to balance family and work obligations) conflicts with the stereotypical expectations of ‘ideal workers’ who should be constantly available to signal commitment to the job regardless of potential family responsibilities (Acker Citation1990; Williams Citation2001) and hence can result in part-time-specific promotion penalties.

One way of studying these promotion penalties is to work with administrative data on companies and their employees to identify job promotions within individual careers and investigate their potential determinants. Previous studies have found a clear gender and part-time gap in promotions among employees (e.g. Kunze and Miller Citation2017). For Germany, this has also been supported not only for internal but also for external (a change from a non-managerial position in firm A to a managerial position in firm B) promotions (Bossler and Grunau Citation2020). With regard to parenthood-specific penalties there is no evidence from Germany yet, as the administrative data sources do not include information on parenthood status. Generally, the approach to derive promotion penalties from residual differences for gender or working hours when adjusting for promotion-relevant factors being available in administrative data (e.g. education, experience) brings the obvious problem that employee’s human capital investments are themselves influences by expectations about future family responsibilities and the perceived level of discrimination in the labor market (Charles and Grusky Citation2004). Hence, if women decide to reduce human capital investments as they expect to carry family obligations in the future, estimates based on administrative data would take this into account as human capital differences and the resulting gender penalty in promotions would be unjustly small.

Therefore, a second way to study promotion penalties is to use factorial survey experiments, where recruiters directly evaluate a candidate’s suitability for an internal promotion. To date, there have been only two recent studies that have applied this survey-experimental approach from the hiring literature (e.g. Bertogg et al. Citation2020) to internal job promotions (for Spain: Fernandez-Lozano et al. Citation2020; and for the UK and the US: Sterkens et al. Citation2023). The rather mixed results suggest that there is a prevailing part-time penalty in Spain, but no evidence for a gender penalty in the promotion evaluations made by real-life supervisors from the US, the UK and Spain. Parental leave is connected to a clear penalty in the US and the UK, while in Spain the evidence suggests a motherhood premium. Although focusing on the promotion evaluations of supervisors comes closest to (i) measure prevailing employer-based discrimination, this approach does not acknowledge that (ii) some groups (e.g. women, parents, part-time workers) might be less likely to aspire internal promotions at all or (iii) are sorted into dead-end jobs with low chances for internal career mobility. Hence, the estimates generalize only to a scenario where all investigated candidates would show similar interest in applying for promotions and are working in jobs with similarly structured promotion opportunities.

Building on this literature, I propose a third way of studying promotion penalties which focuses on perceptions of promotion penalties in the workplace and aims at combining (i) employer-based discrimination, (ii) selective promotion applications and (iii) sorting into dead-end jobs as mechanisms for the persistence of vertical gender segregation.

My contribution to the literature is as follows: First, I contribute to the literature by studying employees’ perceptions of promotion opportunities rather than actual promotion behavior, which is rarely observed. Hence, instead of directly measuring discriminatory practices in the (fictitious) decisions of supervisors (demand-side), this paper investigates whether employees perceive differing promotion chances based on characteristics of (fictitious) co-workers (supply-side). I argue that these perceived promotion penalties can be a result of (i) employee’s subjective evaluation of employer’s promotion discrimination (e.g. through own observation or exchanges with co-workers), (ii) employees perceiving selective promotion applications by their (e.g. female) co-workers and (iii) employees perceiving structural disadvantages based on the sorting into dead-end jobs with low internal career mobility. This subjective measure is consequential because it (potentially) determines whether employees self-select out of leadership careers. After all, if female employees, parents or employees in part-time are sensitive to perceiving promotion penalties for their groups in their working environment, this may lead to a lower level of commitment to their work, higher turnover intentions and lower job satisfaction, overall decreasing the chances that they will strive for (or receive) a promotion (Del Triana et al. Citation2019). Previous research on gender discrimination in the workplace has already shown that even anticipated discrimination can reduce women’s leadership ambitions (Fisk and Overton Citation2019).

Second, to tackle the supply-side perspective, this paper contributes to the literature by exploiting the advantages of factorial survey experiments, a method that has not yet been applied to study perceptions of promotion penalties. Compared to previous literature on workers’ perceptions of discrimination at the workplace (see meta-analysis of 85 studies by Del Triana et al. Citation2019) that was often based on directly asking survey respondents whether they feel discriminated against (e.g. high social desirability), these designs are an ideal tool to study complex evaluations processes and combine the advantages of lab experiments (e.g. higher internal validity, lower social desirability) with those of survey research (e.g. higher external validity) (Auspurg and Hinz Citation2015). As vignette characteristics are randomly varied, their design allows for disentangling multiple determinants of perceived promotion penalties (gender, parenthood and part-time work) while taking qualifications and performance differences into account.

Third, to the best of my knowledge, this paper is the first attempt to study perceptions of promotion penalties based on employees sampled from German firms. Germany provides an interesting context because the prevalence of supervisory positions and women’s disadvantage in holding these positions is close to the European average while women in Eastern European countries are less underrepresented and women in Nordic countries more underrepresented (Dämmrich and Blossfeld Citation2017). Also among higher education graduates in Germany, women are only half as likely to having reached a managerial position ten years after graduation (Ochsenfeld Citation2012). At the same time Germany is characterized by a rather high female labor force participation rate which however is mainly driven by a large share of women and particularly mothers opting for part-time work (Destatis Citation2022). This is also reflected in gender stereotypes that women should be cutting down paid work for family reasons which are similarly common in Germany compared to many other European countries – except the Nordic countries (Breidahl and Larsen Citation2016). Additionally, internal promotions in Germany are a highly relevant means of climbing the workplace hierarchy with almost every second firm filling their vacant supervisory positions with internal candidates (Hammermann and Stettes Citation2018).

To address these contributions to the literature I explore data from a survey experiment gathered in 2021 (for the data see Strauß et al. Citation2022), where 3,761 randomly selected employees from 540 larger (>100 employees) German companies evaluated the chances of fictitious co-workers to receive an internal promotion within the next year, to test whether employees perceived lower promotion chances for their fictitious (i) female co-workers; (ii) co-workers with children; or (iii) co-workers working part-time. As one’s own experiences in the labor market can shape the expected opportunities for similar others, I further study (iv) the sensitivity of participants to perceiving promotion penalties of similar co-workers as an indicator for the associated consequences for themselves (e.g. self-selection out of leadership careers).

Perceptions of promotion penalties: theoretical perspectives and previous research

In contrast to previous literature concerned with penalties for internal promotions as investigated from the side of employers (Fernandez-Lozano et al. Citation2020; Sterkens et al. Citation2023), this study explores promotion penalties of co-workers as perceived by employees.

Perceptions of promotion penalties can emerge based on three mechanisms. First, they can be seen as a subjective measure of actual promotion discrimination by the employer. Employees are constantly confronted with employer’s behavior regarding the award of promotions, e.g. through own observations, exchanges with co-workers, and through the general workplace culture within which internal promotions are more or less commonly awarded to women, parents or part-time workers. Based on these experiences, employees form a subjective perception of the actual level of promotion discrimination in their workplace. As promotion opportunities are rare events, one’s own perceived promotion chances would only provide a limited heuristic in assessing discrimination in workplaces. In turn, extending the heuristic to the promotion chances of one’s co-workers in similar positions might lead to a more adequate – although still only subjective – estimate of the degree of discrimination based on gender, parenthood and part-time work.

Second, they can be a result of employees perceiving selective promotion applications by their (e.g. female) co-workers based on experiences at their workplace or due to internalized stereotypes about who is considered as suitable for internal promotions. Both sources of the expectation that specific groups (e.g. women, parents, part-time workers) seldom aim at internal promotions lead employees to perceive lower promotion chances for co-workers from these specific groups and hence contribute to the perception of promotion penalties.

Third, perceived promotion penalties can emerge based on the sorting of individuals into positions in a firm that are characterized by different levels of promotion chances. This structural mechanism stems from the idea that the allocation of men and women to jobs with different career opportunities can explain lower internal career mobility among women. Hence, working in these so-called ‘dead-end jobs’ (Bihagen and Ohls Citation2007) can also be a source of perceived promotion penalties that is not directly related to promotion discrimination, nor to selective promotion applications due to internalized stereotypes.

Perceptions of promotion penalties are consequential as a (potential) determinant of self-selection out of leadership careers which is connected to persisting vertical (gender) segregation. Based on the three mechanisms mentioned before and related literature (see Levanon and Grusky Citation2016) employees might decide against applying for a promotion because they are (i) conditioning on the likely employer-based discrimination, (ii) carrying internalized stereotypes about suitable promotion candidates that prevent human capital investments or lead them to not aim at supervisory positions even if the required human capital investments were made and they are (iii) working in ‘dead-end jobs’ and perceive their structural disadvantage regarding internal career mobility. All three mechanisms (i–iii) are reflected in the measurement of the promotion chances that employees assign to their co-workers and hence lead employees to stop considering leadership careers. This is highlighted by the literature demonstrating the consequences of perceived discrimination on job-related outcomes (e.g. commitment, satisfaction and turnover intentions) but also on health outcomes (e.g. psychological withdrawal, burnout), and work-related outcomes (e.g. career success; felt conflict with supervisor) (Del Triana et al. Citation2019; Fisk and Overton Citation2019; Volpone and Avery Citation2013).

It is important to note, that for all three mechanisms (i–iii) to be at play, it is not required for subjective and objective discrimination by the employer to be aligned. Even in cases were employers show no objective promotion penalties, employees could still be (i) subjectively perceiving the unequal treatments of themselves or of their co-workers, and (ii) carrying stereotypical beliefs about themselves or their co-workers to not be suited for higher-level positions and (iii) working in ‘dead-end jobs’ and therefore self-select out of aiming at achieving a promotion. Hence, perceived promotion penalties can be consequential for employees independently of the prevailing objective level of employer-based promotion discrimination.

Summing up, perceived promotion penalties refer to the lower promotion likelihood employees perceive with regard to gender, parenthood and part-time work of their co-workers which can be a result of perceived employer-based promotion discrimination, perceived selective promotion applications by employees, and perceived structural disadvantages based on the type of job and the corresponding internal career mobility. Due to the involved consequences for employees themselves, such as self-selecting out of career paths leading to promotions, these subjective perceptions can be a mechanism for the persistence of vertical gender segregation. Based on this conceptualization two subsequent steps are the main focus of this paper. First, measuring the prevalence of perceived promotion penalties while disentangling differences between gender, parenthood and part-time work. And second, investigating which groups are most sensitive to perceiving these penalties and hence are most likely to be affected by their consequences. Accordingly, the following sections outline the previous literature and expected mechanisms at play with regard to gender, parenthood and part-time work, as well as respondent-specific sensitivity to these penalties.

The perceived gender penalty

The Stereotype Content Model (SCM) developed by Fiske et al. (Citation2002) suggests that individuals may be perceived with regard to the two dimensions of warmth (i.e. whether they are seen as trustworthy, empathic and friendly) and competence (i.e. whether they are seen as intelligent, skilled, creative and efficient). When examined empirically, women are generally evaluated higher on warmth, while men, on average, are perceived to be more competent than women (e.g. Eckes Citation2002). As supervisory positions are believed to require higher levels of competence than warmth, employers could be cognitively biased in thinking that promoting female employees might provide a worse match between job tasks and an applicant’s traits compared to the promotion of men. Hence, gender stereotypes are drivers of unequal treatments of men and women in selection processes by employers. Moreover, employees should also be more likely to assign lower chances of getting a job promotion to female co-workers compared to equally qualified male co-workers as they are subjectively evaluating the employer’s practices regarding promotion decisions and might themselves carry internalized stereotypes regarding the lower competences of women compared to men.

The previous literature has found evidence of a substantial gender gap in the composition of supervisory positions (e.g. Dämmrich and Blossfeld Citation2017; Stojmenovska et al. Citation2021) as well as in internal job promotions to supervisory positions using administrative data in Germany (Bossler and Grunau Citation2020) and Norway (Kunze and Miller Citation2017). However, the reasons for these gaps are still under-explored. To date, there exist only two studies based on factorial survey experiments that examined the role of candidate’s gender for the evaluation of promotion chances from the side of real-life supervisors. Their results are similar in a way that they both could found no evidence for a gender penalty in a survey of managers from Spain (Fernandez-Lozano et al. Citation2020),Footnote1 the US and the UK (Sterkens et al. Citation2023). However, employees in this study are not skilled HR professionals, who may be more strongly aware of gender biases or pressured to implement gender mainstreaming measures. Stereotypes associating men with competence and women with warmth may nevertheless be at work when employees evaluate the promotion chances of their co-workers. Hence, based on the SCM, I expect the following:

H1: Employees evaluate female co-workers as being less likely to receive an internal promotion compared to male co-workers.

Parenthood: the perceived motherhood penalty and fatherhood premium

Parenthood is also connected to gender-specific stereotypical notions. According to the SCM (Fiske et al. Citation2002), employees are perceived differently in terms of the dimensions of competence and warmth after becoming parents, and these changes are argued to be gender-specific. Male employees gain perceived warmth while maintaining their perceived level of competence, whereas women – when becoming mothers – gain perceived warmth while losing perceived competence (Cuddy et al. Citation2004). With such a gender-specific gain in perceived assets and a loss in perceived competence, parenthood is expected to have gender-specific consequences on the further careers of mothers and fathers. Moreover, gender stereotypes entail socially shared expectations about the appropriate behavior for women, particularly mothers. According to the normative ideal of ‘intensive mothering’ (Hays Citation1998), mothers should be the primary caregiver and prioritize their children over employment. Mothers who prove to be competent and highly committed to their job are therefore perceived as less warm and are refused job-related rewards because they seemingly violate the prescriptive stereotype of mothers as being nurturing and caring (Benard and Correll Citation2010). On the other hand, male employees tend to be viewed as more mature and stable when they become fathers, which makes them more suitable for managerial positions (Coltrane Citation2004).

Motherhood penalties in hiring evaluations (Correll et al. Citation2007; Cuddy et al. Citation2004) are well documented. With regard to supervisory positions, Stojmenovska et al. (Citation2021) have also found disadvantages for women in the years after they become mothers, although it has to be noted that the gender gap in supervisory positions is already large before parenthood. In terms of promotion opportunities, there is evidence from lab experiments with student samples suggesting that mothers are evaluated as being less likely to be promoted compared to childless women and that these ratings depend on their perceived level of competence (Cuddy et al. Citation2004; Fuegen et al. Citation2004). Based on factorial survey experiments with real-world recruiters from private companies there is somewhat conflicting evidence. While parental leave is clearly connected to a motherhood and a fatherhood penalty in the US and the UK (Sterkens et al. Citation2023), candidates being a mother surprisingly received a promotion premium in Spain (Fernandez-Lozano et al. Citation2020). However, based on the theoretical arguments and the majority of the literature above, I still expect that:

H2: Employees evaluate female co-workers with children as being less likely to receive an internal promotion compared to childless female co-workers.

H3: Employees evaluate male co-workers with children as being more likely to receive an internal promotion compared to childless male co-workers.

The perceived part-time penalty

Opting for part-time work (e.g. to balance family and work obligations) conflicts with the stereotypical expectations of employers: ‘ideal workers’ should be constantly available, which signals a high level of commitment to the job regardless of potential family responsibilities (Acker Citation1990; Williams Citation2001). These norms have become more salient in recent decades (Thébaud and Pedulla Citation2022) and have even endured external shocks on the labor market, such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Schieman et al. Citation2022). Hence, when employees behave against the norm by reducing their working hours, they face the risk of being perceived as a less committed (Williams et al. Citation2013), and may even experience stigmatization (Chung Citation2020). The ‘ideal worker’ norm is so strong that even being visible to other co-workers during normal business hours without any interaction has been shown to positively influence co-workers’ perceptions about that person’s dependability and commitment (Elsbach et al. Citation2010). This prevailing flexibility stigma is connected to a range of consequences, such as higher levels of distress and increased turnover intentions (Ferdous et al. Citation2022).

In hiring processes, previous part-time work experience acts as a signal of lower work commitment and leads to lower call-back rates, especially for male applicants to managerial positions (Pedulla Citation2016). Furthermore, employees from the UK believe workers with flexible work arrangements to create more work for others and face lower chances of being selected for promotions (Chung Citation2020). When employers are asked to rate the promotion chances of candidates with flexible work arrangements, both genders were disadvantaged based on lower levels of perceived commitment in Spain (Fernandez-Lozano et al. Citation2020). Based on these existing findings I expect the following:

H4: Employees evaluate co-workers who work part-time as being less likely to receive an internal promotion compared to co-workers working full-time.

H5: Employees evaluate male co-workers who work part-time as being less likely to receive an internal promotion compared to female co-workers working part-time.

Sensitivity for promotion penalties

So far, the theoretical arguments have related to how employees perceive different co-worker characteristics and possibly adjust their evaluations of promotion likelihood based on stereotypical beliefs about gender, parenthood and part-time work. However, these evaluation processes are likely not only to depend on the characteristics of fictitious co-workers, but also on the characteristics of the evaluating employees. Employees’ own experiences in the labor market can shape the expected opportunities or constraints for others in similar situations. Women who have encountered gender barriers during their time in the labor market are argued to be less likely to believe in the social mobility of other women (Schmitt et al. Citation2003). Hence, if employees of one specific group (e.g. women) are more sensitive to perceive lower promotion chances of their own group, they should be more likely to self-select out of aiming at achieving a promotion in the future which would then contribute to the persistence of vertical gender segregation (Levanon and Grusky Citation2016). As women, mothers and part-time workers are all underrepresented in supervisory positions (e.g. Dämmrich and Blossfeld Citation2017), these groups are more likely to have encountered barriers (or more likely to have experienced similar others self-selecting out of aiming at promotion). They should therefore be more sensitive to the disadvantages of their own group regarding promotions and hence more likely to assign lower promotion chances to co-workers with similar characteristics. Thus, I expect that:

H6: Female employees, part-time employees and mothers are more sensitive to the potential promotion penalties of similar co-workers than male employees, employees working full-time, and childless women.

Methodology

Survey data

To study the perceptions of internal promotion opportunities, I rely on data from a factorial survey experiment that was part of a larger online survey (for data and documentation see Strauß et al. Citation2022). Employees were recruited using a combination of two administrative data sources from the Institute for Employment Research (IAB), the Establishment History Panel (BHP) and Employee History (BeH), which contain information for all firms in Germany with at least one employee and all employees that are subject to social security contributions. Based on these data sources, a stratified random sample was selected of 54,000 employees working in 540 larger firms (at least 100 employees per firm: for method report see Strauß et al. Citation2022). Focusing on larger firms has two advantages for studying internal promotions. First, larger firms are characterized by having internal job markets with ‘job ladders’ that make promotion more common compared to smaller firms (Drucker Citation2012). Second, gender differences regarding promotions are typically smaller in larger firms (e.g. Saridakis et al. Citation2022). Hence, analyzing perceived promotion penalties in larger firms should provide conservative estimates and avoid the risk of overestimation (at least when employees’ awareness of discrimination is comparable across firm sizes).

Fieldwork took place between April and May 2021 using postal invitation letters and up to three postal reminders. The survey experiment was embedded into a regular online survey consisting of several parts. At the start, we asked respondents about their job satisfaction and financial situation; after the survey experiment, we asked them questions about justice principles, organizational context, job situation and, their general life situation (for the codebook, see Strauß et al. Citation2022). All used variables in this paper were collected as part of the online survey or the embedded survey experiment.

Factorial survey design

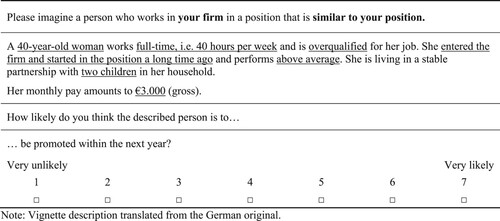

Factorial survey designs are survey experiments in which respondents (in this case employees) are presented with vignettes containing hypothetical persons, objects, or situations (here fictitious co-workers) that they evaluate in terms of their desirability or likelihood (here the chances of fictitious co-workers of receiving an internal promotion within 12 months). Factorial survey experiments are an ideal tool for studying complex decision or evaluation processes for which respondents have to take multiple factors into account at the same time (Auspurg and Hinz Citation2015). This way, evaluations are less prone to social desirability bias (Walzenbach Citation2019). However, to profit from these advantages, it is crucial that the vignettes should be constructed as realistically as possible to provide respondents with reality-inspired scenarios (Auspurg et al. Citation2009). In this study, two steps were undertaken to avoid unrealistic vignettes. First, unlike in many other vignette studies (e.g. Sauer Citation2020), respondents to this survey had to imagine a person working in their own company, with a similar position to their own (see a sample vignette in ). This likely activates a more reliable heuristic for the evaluation of promotion chances compared to the rather unknown promotion chances of a randomly chosen employee in Germany. Second, the calculation of vignette wages was not based on a predefined range of income categories, as this could have resulted in fictional co-workers with unrealistically high or low wages. Therefore, the vignette income was calculated dynamically during the online survey using each respondent’s income and working hours as an anchor and adjusting for vignette working hours (for a step-by-step description, see Strauß et al. Citation2022).

More specifically, the vignettes consisted of eight dimensions described in , which varied randomly. Vignettes also contained information pertaining to the company (‘working in the same company as you’), position (‘working in a similar position as you’) and family status (‘lives with a partner’), which were held constant for each fictitious co-worker. The structure and conditions were similar to previous vignette studies describing fictitious workers (e.g. Auspurg et al. Citation2017). The vignette universe consisted of 6 × 2 × 9 × 2 × 3 × 3 × 4 × 4 = 31,104 vignettes, which was reduced to a fractional design (d-efficiency = 91.4). This algorithmic design search led to a smaller vignette design with 360 vignettes blocked into 72 decks with five vignettes each, while maximizing orthogonality (i.e. minimizing the correlation between each pair of the eight dimensions) and leveling balance (i.e. equalizing the frequencies of each level within decks).

Table 1. Vignette dimensions and levels.

Each respondent then randomly received one of the 72 questionnaire versions and evaluated five vignettes. However, by design, each vignette was randomly assigned only one of six potential items, with ‘being promoted within the next year’ being the central one for this paper.Footnote2 The randomization was checked using the distribution of evaluation tasks by order of vignette (see Supplementary Table A2) and by calculating a bivariate correlation matrix of all variables showing no relevant correlations (min r = −0.03 and max. r = 0.06) (see Supplementary Table A3). Hence, the orthogonality of vignette dimensions was secured as well. By randomizing the order of vignettes per respondent and allowing respondents to move backwards within the online survey to re-evaluate, order and learning effects were reduced (Auspurg and Hinz Citation2015).

Analytical sample

Based on a total of 7,867 survey participants, I reduce the sample of analysis to respondents who received the item on promotion chances for one of their five vignettes at least once (N = 4497, or 57.2%). I further excluded respondents whose self-reported employment status was no longer as an employee of the sample company (e.g. self-employed) (N = 648). After listwise deletion of all cases with missing values on the dependent or independent variables, the sample of analysis consisted of 3761 respondents who evaluated the chances of an internal promotion for 5212 fictitious co-workers (on average 1.39 vignettes).

Measures and analytical strategy

The outcome of interest was the perceived chance that a respondent’s fictitious co-worker would be promoted within the next year and hence moves up one next step in the internal career latter – independently of whether this results in holding a supervisory position. The answers were given using a seven-point scale, ranging from ‘very unlikely’ (1) to ‘very likely’ (7). Not surprisingly due to the experimental variation of vignette dimensions, a majority of respondents evaluated an internal promotion within the next year as rather unlikely (mean promotion chances across all evaluations = 2.74, SD = 1.70), and the most frequently mentioned category was ‘very unlikely’. To account for this skewness in the promotion evaluations, the dependent variable was log transformed (ranging from 0 to 1.95) and the coefficients were exponentiated (exp(coef.)−1) for the following analyzes.Footnote3 Hence, the coefficients from the regression models can be interpreted as the percentage change in the employee’s evaluation with a one-unit change in the independent variable: for example, concerning the gender of the vignette person, the difference in rated promotion chances between male and female co-workers which would speak to a perceived gender penalty in promotions.

The main explanatory measures were the vignette person’s assigned gender, parenthood status and working hours (full-time vs. part-time employment),Footnote4 as well as the respondent’s own gender (ref. male), parenthood status (ref. no children in household) and working hours (full-time vs. part-time) (for their distribution, see ). As additional covariates, I included all remaining co-worker’s characteristics as defined by the vignette design (see ). It was also necessary to take into account the fact that the first evaluation task for each vignette was to rate the fairness of vignette wages. As this could influence the evaluation of promotion chances, I included a categorical variable (1 ‘unfairly low’, 2 ‘fair’, 3 ‘unfairly high’).Footnote5 The order of vignette appearance could also result in differing promotion ratings, which is why another categorical covariate was included to capture this (1 ‘respondents with only one promotion rating’, 2 ‘respondent with more than one promotion rating, first rating’, 3 ‘respondent with more than one promotion rating, not the first rating’). Lastly, I added a dummy variable indicating whether the respondents themselves were working in a supervisory position, as individuals with leadership responsibilities potentially evaluate promotion chances differently from regular employees. Supplementary Table A6 contains a descriptive overview of all the variables.

Table 2. Descriptive overview of the key variables.

Due to the hierarchical data structure of some respondents with multiple promotion evaluations,Footnote6 I followed the advice by Auspurg and Hinz (Citation2015) to account for this nesting using two-level hierarchical linear models (random intercept with evaluations nested in individuals) for the promotion evaluation.Footnote7 The corresponding intraclass correlation in the null model of 0.153 supported this methodological approach. Alternative specifications that additionally take into account the clustering of respondents within firms by including clustered standard errors at the firm-level or by introducing firm-fixed effects to control for unobserved heterogeneity at the firm level do not lead to substantially different results (see Supplementary Table A11). Hence, the measured perceived promotion penalties imply rather general stereotypes about who is more likely to be promoted (or to aim at a promotion) than a firm-specific understanding of promotion processes. All analyzes were run in Stata (SE version 16.1).

To test my hypotheses, I ran stepwise models starting with model 0 which only contains variables at the level of vignettes and hence acts as baseline model. In model 1, the respondent-level variables are added to test for the random assignment of vignette dimensions and present the main effects of the respondent characteristics. If the randomization worked as planned the coefficients of co-worker’s characteristics in m0 and m1 should not vary substantially and provide an estimation of the promotion penalties for gender, parenthood status and working hours. Finally, in model 2 two sets of interactions terms are added to the model. The first set contains interactions between the co-worker’s gender and (a) the co-worker’s parenthood status as well as (b) the co-worker’s working hours to test the hypotheses regarding gender-specific patterns of parenthood penalty and part-time penalty. The second set interacts the respondent’s gender with (a) the co-worker’s gender, (b) the respondent’s parenthood and the co-worker’s parenthood and (c) the respondent’s working hours and the co-worker’s working hours to tackle the hypotheses regarding respondent-specific sensitivity for the perceived promotion penalties (see Supplementary Tables A13–A15 for the sample sizes of all interacted subgroups). For the interaction terms of both sets, I present average marginal effects (AMEs) (see and ).

Results

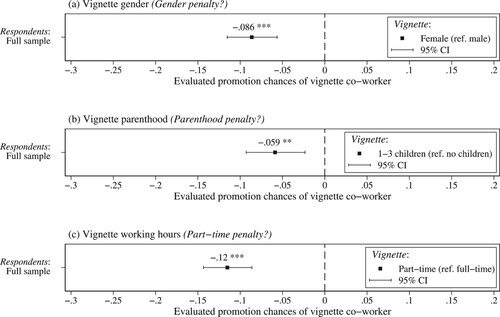

presents the perceived promotion penalties based on the coefficients of a fictitious co-worker’s (a) gender, (b) parenthood status and (c) working hours (for an overview of all covariates, see Supplementary Table A12 and for baseline probabilities of gender, parenthood and working hours see Supplementary Table A13). The gender coefficient indicates that the participants in our study evaluated female co-workers as being 9% less likely than male co-workers to be promoted within the next year, independently of that co-worker’s qualifications, tenure, job performance, parenthood status, working hours, gross earnings and age (and independently of the other additional covariates, e.g. order of vignette appearance). Remember, coefficients can be interpreted as a percentage change in the promotion evaluations as the dependent variable was log transformed and coefficients were exponentiated. Co-workers with children were perceived as being 6% less likely to be promoted compared to childless co-workers, and working part-time even reduced the chance that employees saw of achieving an internal promotion by 12% compared to working full-time.

Figure 2. Perceived promotion penalties: impact of a fictitious co-worker’s gender, parenthood status and working hours on evaluated promotion chances, regression coefficients and 95% confidence intervals.

Note: Visualization based on model 1 from Supplementary Table A12: N (evaluations) = 5512, N (individuals) = 3761. Controls: Vignette level = Age, gross earnings, qualification, tenure, job performance, evaluated fairness of vignette wage, order of vignette appearance; Respondent level = Gender, children in household, part-time, holding a supervisory position. +P<0.1 *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. Data: ‘Fair: Arbeiten in Deutschland’ (Strauß et al. Citation2022), own calculations.

These results clearly show that employees indeed perceive promotion penalties with regard to gender (H1), parenthood, and part-time work (H4). Interestingly, additional subgroups analyzes (see Supplementary Figure A1) show that respondents working in supervisory positions perceive a smaller (b = −0.044, p > 0.1) gender penalty, while the perceived parenthood penalty (b = −0.063, p = <0.1) and the part-time penalty (b = −0.088, p < 0.01) are similar to those of regular employees. This links to the lack of a gender penalty among surveyed managers in Spain (Fernandez-Lozano et al. Citation2020) and supports the approach to survey all employees in order to detect prevailing perceived promotion penalties. Moreover, supervisors generally evaluate the promotion chances about 5% higher (see Supplementary Table A12) indicating that own labor market success might lead them to be more optimistic about promotion chances of their co-workers who were by design also in similar supervisory positions. Finally, the effects of additional co-worker characteristics (Supplementary Table A12) reveal that job performance is the most important predictor of evaluated promotion chances (31% increase for ‘above average’ compared to ‘average’ performance). Although considerably smaller, tenure and qualifications are also relevant predictors that are comparable in size with gender and working part-time.

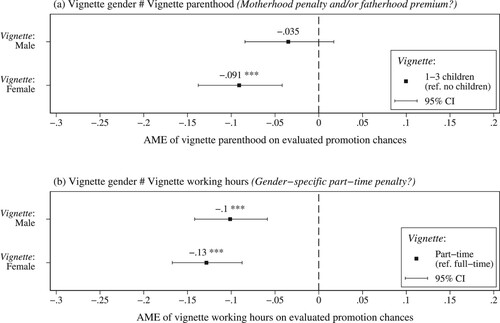

provides the AMEs for the interactions between vignette gender and vignette (a) parenthood status, and (b) working hours (for the predictive margins of the interacted groups, see Supplementary Table A14). Regarding a gender-specific effect of parenthood (a), I find evidence that employees evaluate female co-workers with children as being 9% less likely to be promoted compared to female co-workers without children. This perceived motherhood penalty in terms of promotion supports the second hypothesis (H2). Concerning the expected fatherhood premium, I have to reject the third hypothesis (H3), as the promotion chances of fathers were not evaluated as being higher compared to childless co-workers. There was even a small (−0.035, p = 0.185) perceived parenthood penalty for fathers. However, as it was close to zero and confidence intervals overlapped, it can hardly be interpreted in detail.

Figure 3. Gender-specific promotion penalties: AME with 95% confidence intervals of interactions between.

Note: Visualization based on model 2 from Supplementary Table A12: N (evaluations) = 5512, N (individuals) = 3,761. +P<0.1 *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. Data: ‘Fair: Arbeiten in Deutschland’ (Strauß et al. Citation2022), own calculations.

Next, panel (b) answers the question of a gender-specific part-time penalty. The perceived part-time penalty (compared to working full-time) for achieving an internal promotion was 13% for female co-workers and 10% for male co-workers. Hence, there is no evidence of a perceived double penalty for men (rejecting H5). If anything, male workers suffer a smaller penalty for working part-time, although this is not significantly different from the female part-time penalty (−0.030, p = 0.358).

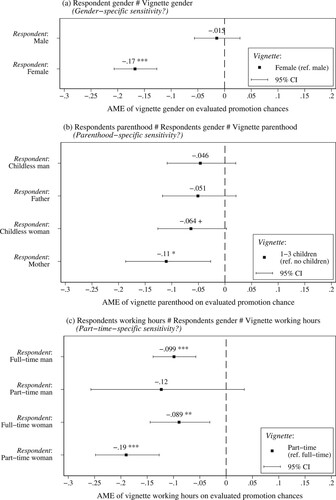

presents results from the investigation into the relationship between a respondent’s characteristics and their perceptions of co-workers with similar characteristics (for the predictive margins of the interacted groups, see Supplementary Table A15). Panel (a) shows that female respondents evaluated their female co-workers as being 17% less likely to achieve promotion than their male counterparts. This supports the first part of the sensitivity mechanism, according to which women should be more sensitive to perceiving a gender penalty in terms of promotion chances. Interestingly, men did not differentiate between genders when rating the promotion chances of their co-workers. Hence, men are seemingly unaware that the gender of their co-workers could influence their promotion chances, while women clearly perceive that their female compared to their male co-workers are less likely to be promoted.

Figure 4. Respondent-specific promotion penalties: AME with 95% confidence intervals of interactions between.

Note: Visualization based on model 2 from Supplementary Table A12: N (evaluations) = 5512, N (individuals) = 3,761. +P<0.1 *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. Data: ‘Fair: Arbeiten in Deutschland’ (Strauß et al. Citation2022), own calculations.

Panel (b) shows that, among the respondents, childless women, fathers and childless men all perceived a similarly small (5-6%) parenthood penalty for their co-workers (p > 0.05). Mothers were the only group that perceived a clear parenthood penalty, as they evaluated co-workers with children as being 11% less likely than childless co-workers to achieve promotion (supporting H6). It has to be noted however, that the group differences of 5–6 percentage points between mothers and the other groups did not reach statistical significance at the 95% level (pairwise comparison of AMEs).

In panel (c), women working part-time themselves were most likely to perceive lower promotion chances for their co-workers working part-time (part-time penalty of 19%). The other three respondent groups also perceived part-time penalties in promotion, which were substantially lower than those among women working part-time (9–12%). The group differences between part-time woman and (i) full-time men as well as (ii) full-time woman are statistically significant at the 95% level. The small group size of part-time men (N = 148) resulted in relatively large confidence bands making it difficult to draw substantial conclusions about this specific subgroup.

Taken together, these results indicate that respondent-specific sensitivity is at play for gender, parenthood status and part-time. Hence, female employees, women working part-time, and mothers appeared to perceive the strongest promotion penalties compared to men, full-time men and women as well as childless men and women and fathers. This generally supports the sixth hypothesis (H6).

Discussion and conclusion

Persisting vertical gender segregation has motivated many researchers to study the discriminatory practices of employers in hiring processes. Internal promotions, on the other hand, have received much less attention, even though they are an alternative and (and often-used) means of climbing the workplace hierarchy for a large share of the employed population (e.g. Fernandez-Lozano et al. Citation2020). In Germany, almost every second firm is filling their vacant supervisory positions with internal candidates (Hammermann and Stettes Citation2018). Hence, discrimination in promotions may accumulate over individual careers and in combination with self-selection out of leadership careers contribute to the persisting vertical gender segregation in the labor market. This study was designed to address this research gap and to extend previous research on promotion discrimination by employers (Fernandez-Lozano et al. Citation2020; Sterkens et al. Citation2023) to the perspective of promotion penalties as perceived by employees. Perceived promotion penalties can be relevant as a subjective measure of actual promotion discrimination by the employer, as a subjective measure of selective promotion applications by (e.g. female) co-workers and structural constrains for promotion opportunities in specific jobs as well as a potential determinant for self-selection out of leadership careers – particularly when perceived for the own group. Hence, this perspective constitutes an innovative, yet realistic approach to assess promotion barriers of women, parents, and part-time workers.

Overall, being a woman, working part-time and being a parent substantially reduced the promotion chances as perceived by the co-workers in larger German firms. Contrary to the expectations, a parenthood penalty was only found for women: Female co-workers with children were evaluated as substantially less likely for promotion (confirming the hypothesis regarding a perceived motherhood penalty), whereas the promotion chances of male co-workers with children were perceived as similar to those without children (refuting the hypothesis regarding a perceived fatherhood premium). This relates to the mixed evidence regarding a potential fatherhood premium in hiring (Albert et al. Citation2011; Bygren et al. Citation2017), in promotion evaluations from lab experiments (Correll et al. Citation2007; Cuddy et al. Citation2004; Fuegen et al. Citation2004) and in employer-based promotion evaluations (Fernandez-Lozano et al. Citation2020; Sterkens et al. Citation2023). Maybe fathers today are perceived as being less committed as well due to their increased use of parental leave (Geisler and Kreyenfeld Citation2019). This could – at least in the German context – counteract that becoming a father increases perceived warmth while retaining stable levels of perceived competence (SCM) and hence result in similar evaluated promotion chances between male co-workers with and without children. Regardless, these results challenge the notion of a fatherhood premium in promotions.

Moreover, the hypothesis that men who work part-time suffer a double penalty also has to be rejected, as male compared to female co-workers in part-time were evaluated similarly regarding their chances of receiving an internal promotion. One explanation here could be that men’s increased involvement in part-time work – although still at a low level compared to women – over the last two decades (Destatis Citation2022) has weakened or even dissolved the ‘ideal man’ norm according to which men who decide against working full-time are stigmatized and face lower perceptions of organizational commitment. In any case, the part-time penalty in promotion chances among German employees appears to be less gendered than expected and no support for a prevailing double penalty among men was found.

With regard to respondents’ gender-, parenthood- and part-time-specific sensitivity, expectations were supported by the data. Women were more sensitive to a gender penalty than men, mothers were more sensitive to a parenthood penalty than non-mothers, and women working part-time to a part-time penalty than women working full-time. These results are worrying evidence that women (especially women with children or women working part-time) perceive their group as disadvantaged for internal promotions, which I interpret as an indicator for (potential) self-selection out of a leadership career.

This study comes with several limitations. First, one might argue that there is a gap between actual promotion penalties and perceived promotion penalties as studied in this paper. Hence, higher sensitivity for perceived penalties in a firm does not clearly correspond to the actual promotion penalties employees might face through the discriminatory practices of supervisors. However, I argue that perceived promotion penalties are nonetheless important, as they might prevent women (or mothers, or part-time workers) from aiming at supervisory positions even if there is no actual employer bias disadvantaging them.

Second, the experimental design did not include or manipulate information on the fictitious co-workers’ aspiration to (not) strive for a promotion. Therefore, it unfortunately remains speculative whether employees perceived lower promotion chances of women, mothers and part-time workers because they perceive these groups (i) to be discriminated against by the employer, (ii) to be less likely to aim at a leadership role anyway or (iii) are sorted into dead-end jobs with low promotion opportunities. Here, future studies could focus specifically at disentangling the potential drivers of perceived promotion penalties, e.g. by including the co-workers’ career aspirations.

Third, the data does not contain any baseline information of actual promotion probabilities in the respondent’s firm. Hence, respondents from firms with varying levels of internal mobility might show downwardly or upwardly biased promotion evaluations of their co-workers. This should, however, only concern the level of average promotion ratings, and should not be problematic for analyzing the experimentally varied co-worker’s characteristics. Future work could nonetheless explore the working environment by potentially linking additional administrative data on the firm level to compare actual and perceived promotion penalties and to better understand contextual factors that might constrain the perceptions of promotion penalties.

Fourth and last, despite being characterized by a large external validity compared to lab experiments the applied factorial survey design can only be generalizable for employees within larger German firms. Whether the results differ within smaller establishments or between other European countries remains therefore speculative and a question for future studies.

Nevertheless, the detected penalties in this study have implications for both employees and employers. The higher magnitude of the perceived gender, motherhood and part-time penalty (net of other promotion-relevant factors) among female employees, mothers and women in part-time indicates that a substantial share of women in the German labor market perceives a barrier with regard to reaching these jobs which could lead them to stop consider aiming at them. This is detrimental for women’s career advancement and contributes to persisting vertical gender segregation.

There are also implications for employers. Women who aim at higher-level jobs but who perceive promotion penalties (based on gender, being a mother or working part-time) within their current company are likely to improve their situation by changing their employer. These human capital losses are to be avoided by employers, particularly at times of skilled labor shortages (Dettmann et al. Citation2019), by giving employees a fair chance for promotion independently of their gender, parenthood status or working hours.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (705.8 KB)Acknowledgements

The author thanks participants of the PopFest 2022: 28th Annual Postgraduate Population Studies Conference and the 2022 Venice Seminar for Analytical Sociology: Theory and Empirical Applications for the valuable discussions, and the Editors and anonymous reviewers for their fruitful comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data and documentation of ‘Fair: Arbeiten in Deutschland’ can be found at https://doi.org/10.7802/2486

.Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ole Brüggemann

Ole Brüggemann is a doctoral researcher in sociology at the Cluster of Excellence ‘The Politics of Inequality’, University of Konstanz, Germany. His current research interests include (gendered) perceptions of social inequalities and their behavioral outcomes. His work has been published in European Sociological Review.

Notes

1 Thanks to the replication material by Fernandez-Lozano et al. (Citation2020) it was possible to replicate their main model with separate covariates for gender and the number of children (see Supplementary Table A1).

2 The additional five items were (1) apply for another job, (2) complain at the workers’ council, (3) renegotiate her own salary, (4) decrease her effort and (5) increase her effort.

3 For a comparison of a model with (a) log transformed and exponentiated coefficients, (b) log transformed coefficients as well as a model (c) without log transformation see Supplementary Table A4. The results – apart from the scaling – do not vary substantially.

4 The operationalization of the vignette working hours full-time (40 h/week); part-time (20 h/week) is a simplification of part-time employment that has to be considered as limitation of the experimental design.

5 The results are robust to the in- or exclusion of the evaluated fairness of vignette wages (see Supplementary Table A5).

6 See Supplementary Table A7 for the number of vignette evaluations per respondent. As respondents’ promotion ratings could vary depending on the number of different rating tasks presented in their individual set of vignettes, Supplementary Table A8 contains a comparison where this information was included as a robustness check. Results do not vary substantially. Moreover, a higher number of distinct rating tasks could influence respondent’s fatigue. To test this, Supplementary Table A9 includes a model for the response time per vignette (logged) on the vignette number and the number of distinct ratings per respondent. Response time per vignette decrease with each vignette (typical learning effect) but there is no indication for a fatigue effect depending on the number of distinct vignette ratings per respondent.

7 Please note that results remain stable when based on OLS with cluster-robust standard errors (see Supplementary Table A10).

References

- Acker, J. (1990) ‘Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: a theory of gendered organizations’, Gender & Society 4: 139–58.

- Albert, R., Escot, L. and Fernández-Cornejo, J. A. (2011) ‘A field experiment to study sex and age discrimination in the Madrid labour market’, The International Journal of Human Resource Management 22: 351–75.

- Allen, T. D. and Russell, J. E. A. (1999) 'Parental leave of absence: Some not so family-friendly implications', Journal of Applied Social Psychology 29: 166–91.

- Auspurg, K. and Hinz, T. (2015) Factorial Survey Experiments. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Auspurg, K., Hinz, T. and Liebig, S. (2009) ‘Komplexität von Vignetten, Lerneffekte und Plausibilität im Faktoriellen Survey’, Methoden, Daten, Analysen 3: 59–96.

- Auspurg, K., Hinz, T. and Sauer, C. (2017) ‘Why should women get less? Evidence on the gender pay gap from multifactorial survey experiments’, American Sociological Review 82: 179–210.

- Benard, S. and Correll, S. J. (2010) ‘Normative discrimination and the motherhood penalty’, Gender & Society 24: 616–46. doi:10.1177/0891243210383142 .

- Bertogg, A., Imdorf, C., Hyggen, C., Parsanoglou, D. and Stoilova, R. (2020) ‘Gender discrimination in the hiring of skilled professionals in two male-dominated occupational fields: a factorial survey experiment with real-world vacancies and recruiters in four European Countries’, KZfSS Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 72: 261–89.

- Bihagen, E. and Ohls, M. (2007) ‘Are women over-represented in dead-end jobs? A Swedish study using empirically derived measures of dead-end jobs’, Social Indicators Research 84: 159–77.

- Birkelund, G. E., Lancee, B., Larsen, E. N., Polavieja, J. G., Radl, J. and Yemane, R. (2022) ‘Gender discrimination in hiring: evidence from a cross-national harmonized field experiment’, European Sociological Review 38: 1–18.

- Bossler, M. and Grunau, P. (2020) ‘Asymmetric information in external versus internal promotions’, Empirical Economics 59: 2977–98.

- Breidahl, K. N. and Larsen, C. A. (2016) ‘The myth of unadaptable gender roles: attitudes towards women’s paid work among immigrants across 30 European countries’, Journal of European Social Policy 26: 387–401.

- Bygren, M., Erlandsson, A. and Gähler, M. (2017) ‘Do employers prefer fathers? Evidence from a field experiment testing the gender by parenthood interaction effect on callbacks to job applications’, European Sociological Review 33: 337–48.

- Bygren, M. and Gähler, M. (2012) ‘Family formation and men's and women's attainment of workplace authority’, Social Forces 90: 795–816.

- Charles, M. and Grusky, D. B. (2004) Occupational Ghettos: The Worldwide Segregation of Women and Men, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Chung, H. (2020) ‘Gender, flexibility stigma and the perceived negative consequences of flexible working in the UK’, Social Indicators Research 151: 521–45.

- Coltrane, S. (2004) ‘Elite careers and family commitment: it’s (still) about gender’, The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 596: 214–20.

- Correll, S. J., Benard, S. and Paik, I. (2007) ‘Getting a job: is there a motherhood penalty?’, American Journal of Sociology 112: 1297–339.

- Cuddy, A. J. C., Fiske, S. T. and Glick, P. (2004) ‘When professionals become mothers, warmth doesn't cut the ice’, Journal of Social Issues 60: 701–18.

- Dämmrich, J. and Blossfeld, H.-P. (2017) ‘Women’s disadvantage in holding supervisory positions. variations among European countries and the role of horizontal gender segregation’, Acta Sociologica 60: 262–82.

- Del Triana, M. C., Jayasinghe, M., Pieper, J. R., Delgado, D. M. and Li, M. (2019) ‘Perceived workplace gender discrimination and employee consequences: a meta-analysis and complementary studies considering country context’, Journal of Management 45: 2419–47.

- Destatis (2022) Abhängig Erwerbstätige nach Beschäftigungsumfang und Geschlecht (1985-2019). GENESIS-Online: Ergebnis 12211-9010.

- Dettmann, E., Fackler, D., Müller, S., Neuschäffer, G., Slavtchev, V., Leber, U. and Schwengler, B. (2019) Fehlende Fachkräfte in Deutschland - Unterschiede in den Betrieben und mögliche Erklärungsfaktoren. Ergebnisse aus dem IAB-Betriebspanel 2018. (IAB-Forschungsbericht 10/2019), Nürnberg.

- Drucker, P. (2012) The Practice of Management, 2nd edn, Hoboken, NJ: Taylor & Francis.

- Eckes, T. (2002) ‘Paternalistic and envious gender stereotypes: testing predictions from the stereotype content model’, Sex Roles 47: 99–114.

- Elsbach, K. D., Cable, D. M. and Sherman, J. W. (2010) ‘How passive ‘face time’ affects perceptions of employees: evidence of spontaneous trait inference’, Human Relations 63: 735–60.

- Eurofound (2020) Gender Equality at Work, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Ferdous, T., Ali, M. and French, E. (2022) ‘Impact of flexibility stigma on outcomes: role of flexible work practices usage’, Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 60: 510–31.

- Fernandez-Lozano, I., González, M. J., Jurado-Guerrero, T. and Martínez-Pastor, J.-I. (2020) ‘The hidden cost of flexibility: a factorial survey experiment on job promotion’, European Sociological Review 36: 265–83.

- Fisk, S. R. and Overton, J. (2019) ‘Who wants to lead? Anticipated gender discrimination reduces women’s leadership ambitions’, Social Psychology Quarterly 82: 319–32.

- Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., Glick, P. and Xu, J. (2002) ‘A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 82: 878–902.

- Fuegen, K., Biernat, M., Haines, E. and Deaux, K. (2004) ‘Mothers and fathers in the workplace: how gender and parental status influence judgments of job-related competence’, Journal of Social Issues 60: 737–54.

- Geisler, E. and Kreyenfeld, M. (2019) 'Policy reform and fathers’ use of parental leave in Germany: The role of education and workplace characteristics', Journal of European Social Policy 29: 273–91.

- Hammermann, A. and Stettes, O. (2018) Welche Kriterien befördern den Aufstieg auf internen Karriereleitern? Eine empirische Untersuchung auf Basis des IW-Personalpanels, Köln: Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft (IW), IW-Report 10/2018.

- Hays, S. (1998) The Cultural Contradictions of Motherhood, New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Kunze, A. and Miller, A. R. (2017) ‘Women helping women? Evidence from private sector data on workplace hierarchies’, The Review of Economics and Statistics 99: 769–75.

- Levanon, A. and Grusky, D. B. (2016) ‘The persistence of extreme gender segregation in the twenty-first century’, American Journal of Sociology 122: 573–619.

- Ochsenfeld, F. (2012) ‘Gläserne Decke oder goldener Käfig: Scheitert der Aufstieg von Frauen in erste Managementpositionen an betrieblicher Diskriminierung oder an familiären Pflichten?’, KZfSS Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 64: 507–34.

- Pedulla, D. S. (2016) ‘Penalized or protected? Gender and the consequences of nonstandard and mismatched employment Histories’, American Sociological Review 81: 262–89.

- Rudman, L. A. and Mescher, K. (2013) ‘Penalizing men who request a family leave: is flexibility stigma a femininity stigma?’, Journal of Social Issues 69: 322–40.

- Saridakis, G., Ferreira, P., Mohammed, A.-M. and Marlow, S. (2022) ‘The relationship between gender and promotion over the business cycle: does firm size matter?’, British Journal of Management 33: 806–27.

- Sauer, C. (2020) ‘Gender bias in justice evaluations of earnings: evidence from three survey experiments’, Frontiers in Sociology 5: 22.

- Schieman, S., Badawy, P. and Hill, D. (2022) ‘Did perceptions of supportive work-life culture change during the COVID-19 pandemic?’, Journal of Marriage and Family 84: 655–72.

- Schmitt, M. T., Ellemers, N. and Branscombe, N. R. (2003) ‘Perceiving and responding to gender discrimination in organizations’, in S. A. Haslam, D. van Knippenberg, M. J. Platow and N. Ellemers (eds.), Social Identity at Work: Developing Theory for Organizational Practice, New York, NY: Psychology Press, pp. 277–92.

- Sterkens, P., Baert, S., Rooman, C. and Derous, E. (2023) ‘Why making promotion after a burnout is like boiling the ocean’, European Sociological Review 39: 516–31.

- Stojmenovska, D., Steinmetz, S. and Volker, B. (2021) ‘The gender gap in workplace authority: variation across types of authority Positions’, Social Forces 100: 599–621.

- Strauß, S., Hinz, T., Nick, Z., Brüggemann, O. and Lang, J. (2022) Fair: Arbeiten in Deutschland (Konstanz). Datenfile Version 1.0.0. Available from: https://doi.org/10.7802/2486 .

- Thébaud, S. and Pedulla, D. S. (2022) ‘When do work-family policies work? Unpacking the effects of stigma and financial costs for men and women’, Work and Occupations 49: 229–35.

- Volpone, S. D. and Avery, D. R. (2013) ‘It's self defense: how perceived discrimination promotes employee withdrawal’, Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 18: 430–48.

- Walzenbach, S. (2019) ‘Hiding sensitive topics by design? An experiment on the reduction of social desirability bias in factorial Surveys’, Survey Research Methods 13: 103–21.

- Williams, J. (2001) Unbending Gender: Why Family and Work Conflict and What To Do About It, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Williams, J. C., Blair-Loy, M. and Berdahl, J. L. (2013) ‘Cultural schemas, social class, and the flexibility stigma’, Journal of Social Issues 69: 209–34.