ABSTRACT

Whether further European integration is desirable is an ongoing question in public opinion research: both extant research and the outcome of various EU-related referendums show that many citizens hold negative views on proposals that lead to further loss of national sovereignty. An important issue thus arises: does the prospect of such additional sovereignty loss increase negativity towards the EU? This study attempts to answer this question using a pre-registered original survey experiment conducted among members of a nationally-representative high-quality Dutch panel. Our focus is on how exposure to proposed abolishment of EU member states’ right of veto affects EU attitudes. In addition, we analyse whether the exposure effect is shaped by 1) citizens’ prior populist attitudes and 2) the Eurosceptic character of the medium. Concerning the former, informed by recent in-depth qualitative research, we hypothesise that populist attitudes aggravate the extent to which exposure to potential loss of national sovereignty leads to more negative EU attitudes. Concerning the latter, we hypothesise that exposure via a Eurosceptic medium might either aggravate or abate the extent to which the newspaper message leads to more negative EU attitudes. We discuss our findings and provide suggestions for further research.

1. Introduction

While the existence of the European Union (EU) evidently entails a degree of European integration and hence sovereignty loss of individual member states, the issue of whether further integration is desirable is fiercely debated and a key issue in public opinion research. Various studies have scrutinised citizens’ attitudes on this matter (e.g. De Vries and Steenbergen Citation2013; Ejrnaes and Jensen Citation2019; Janssen Citation1991; Toshkov and Krouwel Citation2022; Vössing Citation2015), which is of paramount importance as ‘[p]ublic attitudes, through mass political behaviour, shape and constrain the process of European integration’ (Gabel Citation1998: 333). The surprising results of the referendums on the EU constitution in 2005 (Baden and De Vreese Citation2008; Hobolt Citation2007; Hobolt and Brouard Citation2011; Lubbers Citation2008; Schuck and De Vreese Citation2008) and the association treaty with Ukraine in 2016 (Abts et al. Citation2023; Van der Brug et al. Citation2018), indeed made it abundantly clear that citizens’ stances influence the process of European integration. Moreover, those referendums suggest that many citizens hold negative views on proposals that lead to further loss of national sovereignty.

Against this background of popular aversion to further European integration and accompanied additional loss of national sovereignty, we ask: does the prospect of further sovereignty loss fuel Euroscepticism? This study aims to address this question by employing a pre-registered survey experiment conducted among members of a high-quality panel representative of the Dutch population to test empirically whether exposure to plans for further EU integration strengthens negative attitudes to the institution. To this end, we experimentally exposed respondents to the potential abolition of the right of veto of EU member states. We strategically selected that issue for our experimental condition, as it is supported by some countries in the EU (BNR Citation2021) and, if implemented, would clearly lead to an additional loss of national sovereignty.

Using the EU member states’ right of veto as a case adds to the external validity of our experiment, and it does not tap into substantive political topics discussed within the EU, like migration or measures to mitigate climate change. Moreover, by situating the study in the Netherlands, which is far less influential in the EU than, e.g. France or Germany, we are increasing the likelihood that the respondents will regard the loss of the right of veto as a threat to national sovereignty. Our experiment is used to first answer the following research question: does the proposed abolishment of the EU member states’ right of veto increase negative EU attitudes?

It is doubtful that the impact will be universal: the same information is likely to be interpreted differently, depending on its source and the individual viewing it. After all, ‘every opinion is a marriage of information and predisposition: information to form a mental picture of a given issue, and predisposition to motivate some conclusion about it’ (Zaller Citation1992: 6). That the same information can be interpreted differently by different segments of the population depending on a person’s understanding of a subject has also been found by various empirical studies (De Koster et al. Citation2016; De Koster and Achterberg Citation2015; Kahan Citation2010; Van Rijn et al. Citation2019). With regards to EU attitudes, the degree of populist attitudes has been found to be crucial for how the EU is understood (Van den Hoogen et al. Citation2022a), thus we will scrutinise whether populist attitudes amongst citizens moderate the effect of exposure to plans to abolish the right of veto.

As information does not exist in a vacuum, how a proposal to remove the right of veto is communicated probably affects its impact. Research has found that the media in general play a ‘double role in both fuelling and reducing Euroscepticism’, depending, amongst other things, on the source (De Vreese Citation2007: 42). It also shows that specific media can be affiliated with a specific stance on the EU – ranging from Europositive to Euro-ambivalent to Eurosceptic (Leruth et al. Citation2017). Consequently, we also test whether the medium (Europositive versus Eurosceptic) in which the message is communicated shapes the attitudinal consequences of the message. Therefore, the second question to be answered with our experiment is: does the effect of the proposed abolishment of the EU member states’ right of veto on EU attitudes differ depending on the level of populist attitudes of the receiver or the Eurosceptic character of the medium in which the message is communicated?

2. The effect of a proposed loss of national sovereignty on EU attitudes

People’s attitudes on whether the EU should integrate further have been included in many different kinds of studies. For example, some studies have used citizens’ stances on further integration as an indicator of support for the institution more generally (e.g. Anderson and Hecht Citation2018; Baute et al. Citation2018; Carey Citation2002; Hooghe and Marks Citation2004; Jayet Citation2020). At the same time, various studies have linked negative attitudes towards the European Union to concerns about loss of national sovereignty (e.g. Borriello and Brack Citation2019; Carrieri and Vittori Citation2021; Pirro and Van Kessel Citation2017; Yordanova et al. Citation2020). Moreover, recent qualitative and quantitative studies set in the Netherlands (Van den Hoogen Citation2022a; Citation2022b) have demonstrated that further sovereignty loss is an issue of concern for Eurosceptics and Euro-enthusiasts alike. More specifically, these earlier studies showed that being explicitly pro-EU, i.e. being in favour of their country’s membership to the EU, does not necessarily go hand in hand with being in favour of further European integration. It thus seems likely that proposals that would result in further loss of national sovereignty, of which abolishment of the right of veto of member states is a key example, would negatively impact attitudes to the EU across the board.

To assess whether public opinion on the EU is affected by a proposal that signals national sovereignty loss, we carefully selected five distinct EU attitudes. Informed by prior survey research (Boomgaarden et al. Citation2011; De Vreese et al. Citation2019) and in-depth interviews among Dutch citizens (Van den Hoogen et al. Citation2022a), this study distinguishes four attitudes tapping into the rational aspects of EU attitudes: on The Netherlands’ membership to the EU; on a Dutch exit out of the EU (‘Nexit’); on Dutch sovereignty within the EU; and on EU enlargement. Informed by recent studies highlighting the importance of emotions in EU attitudinal research (e.g. De Vreese et al. Citation2019; Marquart et al. Citation2019; Nielsen Citation2018; Verbalyte and Von Scheve Citation2018), we also selected an attitude focusing on a negative emotive response to the EU. This attitude, measuring disgust with the EU, is based on earlier research and frequently used in EU attitudinal research (e.g. Bakker and De Vreese Citation2016; Boomgaarden et al. Citation2011; De Vreese et al. Citation2019). We therefore hypothesise (H1a-H1e): A proposal for abolishment of EU member states’ right of veto causes citizens to be a) more negative towards EU membership; b) more negative towards EU expansion; c) more supportive of a ‘Nexit’; d) more likely to believe that the EU endangers Dutch sovereignty; e) more disgusted with the EU.

Of course, not everyone is likely to interpret such cues in the same way: how citizens understand and respond to certain prompts depends on their ‘principles of selection, emphasis and presentation composed of little tacit theories about what exists, what happens, and what matters’ (Gitlin Citation1980: 6; cf. Hall Citation1980; Zaller Citation1992). In other words, it is likely that the meaning an individual ascribes to a social phenomenon influences how cues about it are perceived. Indeed, extant research on a wide range of issues has shown that worldviews moderate how informational or neighbourhood cues affect political attitudes and behaviour, e.g. concerning opinions on hydrogen technologies (de Koster and Achterberg Citation2015), Turkey becoming an EU member (Azrout et al. Citation2011), suspended prison sentences (de Koster et al. Citation2016), or vote choices (Van Noord et al. Citation2018).

This is likely also the case when the focus is on cues regarding an EU-induced additional loss of national sovereignty. As there are various indications that people have different understandings of the EU (Van den Hoogen et al. Citation2022a; Citation2022b), this likely shapes their reactions to EU policy proposals. Populist attitudes are crucial in this respect: a recent interview study among Dutch citizens showed that those whose views are more anti-establishment tend to perceive the EU as a malicious instrument of the elites, which is only used to further their interests at the detriment of the common people. Those whose views are more populist were found to perceive the EU as being led by a group of elites that make up the top of a power hierarchy, from which they ‘exploit’ all member states out of their own self-interest (Van den Hoogen et al. Citation2022a). Respondents from this study even described the EU as a ‘tactical coup’ (Van den Hoogen et al. Citation2022a: 11) and named the Dutch prime minister ‘the bellboy of the EU’ (p. 11).

Having a populist understanding of the EU, then, is likely to underlie a more negative response to a proposal that would result in additional loss of national sovereignty. After all, from that perspective, such a proposal would give more power to a ‘malignant’ EU at the cost of the sovereignty of the nation states themselves: it would be even better positioned to ‘exploit’ the Netherlands than it currently does. The notion of ‘motivated reasoning’ predicts something similar: citizens’ prior populist attitudes could act as a ‘perceptual screen’, motivating ‘effortful processing of relevant information’ (Bolsen et al. Citation2014: 241; cf. Taber and Lodge Citation2012 [2006]; Taber and Lodge Citation2012). Therefore, the policy proposal in our experiment will likely reinforce negative opinions about the EU for people with a higher level of populist attitudes. We therefore anticipate that the hypothesised effect of the proposal for abolishment of EU member states’ right of veto on negative EU attitudes is stronger for citizens with a higher level of populist attitudes (H2a-H2e):

There is a positive interaction between exposure to a proposal for abolishment of EU member states’ right of veto and having more populist attitudes on a) a negative view on EU membership; b) a negative view on EU enlargement; c) support for a ‘Nexit’; d) the belief that the EU endangers Dutch sovereignty; e) disgust with the EU.

The way newspapers report on EU issues typically reflects their general stance towards the EU, which is often consistent and ranges from Europositive via Euro-ambivalent to Eurosceptic (Leruth et al. Citation2017: 101). We consider it likely that such a stance will influence how reports on EU-related matters are interpreted by readers. Inspired by research on the distinctions between tabloid and broadsheet newspapers (e.g. de Vreese and Boomgaarden Citation2006a; Dutceac Segesten and Bossetta Citation2019; Hameleers Citation2019; Leruth et al. Citation2017), our focus in this study is more specifically on the differences between a tabloid known to be consistently Eurosceptic and a broadsheet widely acknowledged as representing the opposite position. We hypothesise that the medium’s stance could have two possible effects. First, exposure to a report contained in a newspaper which generally has a negative position concerning EU matters, and thus a Eurosceptic connotation, could lead to more negative interpretations of our proposed treatment (H3a-H3e):

There is a positive interaction between exposure to a proposal for abolishment of EU member states’ right of veto and the message being published in a Eurosceptic newspaper on a) a negative view on EU membership; b) a negative view on EU enlargement; c) support for a ‘Nexit’; d) the belief that the EU endangers Dutch sovereignty; e) disgust with the EU.

There is a negative interaction between exposure to a proposal for abolishment of EU member states’ right of veto and the message being published in a Eurosceptic newspaper on a) a negative view on EU membership; b) a negative view on EU enlargement; c) support for a ‘Nexit’; d) the belief that the EU endangers Dutch sovereignty; e) disgust with the EU.

3. Data, treatment & measures

Our study was pre-registered on the Open Science Framework (OSF)Footnote1 prior to the start of data collection and received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Review Committee of the Department of Public Administration and Sociology at Erasmus University Rotterdam.Footnote2 The causal relationship between a proposal resulting in a loss of national sovereignty and negative attitudes towards the EU was assessed via a randomised, population-based, survey experiment using a 2×2 factorial between-subjects design (n = 1,587). Respondents were therefore randomly assigned to one of four conditions, ensuring that any characteristics potentially relevant for processing those conditions were randomly distributed. We included pre-measures that were identical to the outcome measures from a previous survey completed by the same respondents as controls (De Koster et al. Citation2020). This made the identification of the treatment’s effect more precise (Clifford et al. Citation2021). In addition to these pre-measures, we also measured populist attitudes in the same earlier survey (Akkerman et al. Citation2014). These pre-measured EU and populist attitudes were linked to the data newly collected for the present study.

We used the high-quality LISS (Longitudinal Internet Studies for the Social Sciences) panel, and only included participants aged 18 or older. The LISS panel was established via true probability sampling of households in the Netherlands using the official Dutch population register (Scherpenzeel, Citation2009). Centerdata, an independent scientific research institute affiliated with Tilburg University, manages the panel and collected the data on our behalf.

After exposure to one of the four treatment conditions detailed below, the respondents answered questions on their attitudes towards the EU. This enabled us to estimate both the causal effects of a proposal concerning the abolition of the EU member states’ right of veto on EU attitudes, and whether these effects are moderated by prior populist attitudes and the Eurosceptic character of the medium. The respondents also answered two manipulation check questions, one on the topic of the text and the other on the medium in which it was, supposedly, published. However, since the literature indicates that removing respondents from a sample in this way could bias results (Aronow et al. Citation2019; Montgomery et al. Citation2018), we only excluded those who had failed the check included in the sensitivity analyses (see below), and not when testing our pre-registered hypotheses.

3.1. Treatment

The treatment was an image of an online newspaper article reporting on EU member states’ right of veto. The text either just explained this right (control) or, in addition, addressed plans for its potential abolition (treatment). Furthermore, the report was shown as an image that mimicked either an online page of a Eurosceptic tabloid or a non-Eurosceptic broadsheet. We chose De Telegraaf and de Volkskrant for this purpose, as an expert survey has determined the former to be largely Eurosceptic and the latter to be generally Europositive or Euroambivalent (Leruth et al. Citation2017: 101). The text of the report was based on actual coverage of EU member states’ right of veto and its potential abolition (BNR Citation2021), thus increasing the experiment’s external validity. This resulted in four experimental conditions differing both in message (control versus treatment) and source (Eurosceptic versus non-Eurosceptic). The experimental conditions, including the text and the layout, can be found in the online supplementary material (Figure S1a – Figure S1d).

3.2. Measures

Informed by survey research (Boomgaarden et al. Citation2011; de Vreese et al. Citation2019) and recent in-depth interviews (Van den Hoogen et al. Citation2022a), we selected five items to measure EU attitudes: 1) ‘Dutch membership of the European Union is a good thing’; 2) ‘The European Union should be enlarged with other countries’; 3) ‘The Netherlands should leave the European Union’; 4) ‘The European Union endangers the independence of the Netherlands’; and 5) ‘I am disgusted by the European Union’. The respondents were asked to respond to each statement on a seven-point Likert scale, with the possible answers ranging from ‘completely disagree’ to ‘completely agree’. The first two items were recoded such that a higher score reflects more negative attitudes on the EU. Reflecting our hypotheses, the variables measuring EU attitudes are not combined into a single scale.

Populist attitudes were measured using Akkerman et al.’s (Citation2014) widely used scale, for which we combined the following items: 1) ‘The people, and not politicians, should make our most important policy decisions’; 2) ‘The political differences between the elite and the people are larger than the differences among the people’; 3) ‘I would rather be represented by a citizen than by a specialised politician’; 4) ‘Elected officials talk too much and take too little action’; and 5) ‘What people call ‘compromise’ in politics is really just selling out on one’s principles’. Respondents answered each of these statements on a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from ‘completely disagree’ to ‘completely agree’. We calculated the mean score for respondents with valid scores on all five items. A reliability analysis demonstrated that the scale was highly reliable, with α = 0.83 (M: 4.26; SD: 1.13).

4. Results

4.1. Main analyses

We estimated the treatment effects using ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models (). These concerned the causal effects of the proposed abolition of the right of veto on negative attitudes towards the EU (Model 1), as well as the interaction effects on those attitudes between the proposal and populist attitudes (Model 2) and the type of newspaper containing the report (Model 3). As we used five distinct attitudes towards the EU, we ran each of the three models five times – once per EU attitude. Each model also included the corresponding pre-measured attitude to increase the precision of the estimates (Clifford et al. Citation2021).

Table 1. OLS regression estimates for negative EU attitudes.

As shown in , we did not identify any significant direct effects of the treatment on attitudes to the EU. H1a-H1e are therefore not supported. Moreover, its interaction effects with populist attitudes (models 2) or with the medium in which the message is reported (models 3), are also not significant. We plotted the interaction effects as to aid their interpretation (Brambor et al. Citation2006).

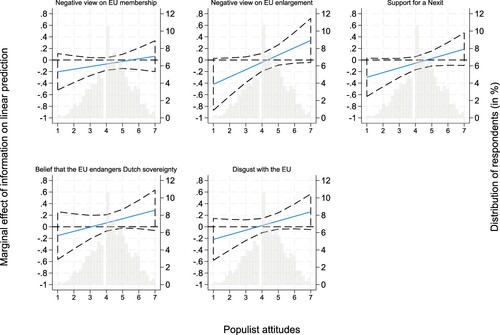

shows the conditional marginal effects of a proposal for the abolishment of right of veto on EU attitudes by populist attitudes. Although H2a-H2e need to be rejected, the consistent pattern suggests that the EU attitudes of more populist citizens may become more negative after reading that proposal while that is not the case among the least populist citizens. We will discuss this further in the conclusion.

Figure 1. Conditional marginal effects of abolishment of EU’s right of veto on negative EU attitudes, by prior populist attitudes (95% confidence interval), including histograms of the distribution of prior populist attitudes.

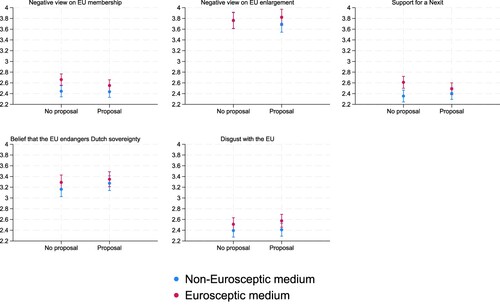

In contrast to , shows no clear pattern. The proposal of abolishment of right of veto hardly interacts with the type of newspaper in which it is published, and the weak interaction effects also differ in direction across EU attitudes. Clearly the kind of newspaper in which the message is reported does not shape how exposure to a proposal of abolishment of right of veto influences those attitudes, and H3a-H3e and H4a-H4e need to be rejected.

4.2. Four exploratory analyses

We conducted four types of exploratory analyses. First, we looked at the direct effects on EU attitudes of the type of newspaper in which the treatment proposal was published. As indicated in , there was a positive, significant, direct effect for three of the five attitudes measured: publishing the text in a Eurosceptic newspaper led to more negative views on the EU; more support for a Nexit; and higher levels of disgust with the EU. As the message reported in either newspaper was the same for both, this indicates that the Eurosceptic connotation of a certain newspaper affects EU attitudes, even though it does not moderate the impact of our treatment. We reflect on this further in the conclusion.

Table 2. OLS regression estimates for negative EU attitudes.

Second, we included measures on the credibility (‘The information in the newspaper article is credible’) and comprehensibility (‘The newspaper article is hard to understand’) of the text. The participants reacted to these statements after responding to the measures of EU attitudes. The responses to these items demonstrated that most of them regarded the (control and treatment) texts as credible, with only 5.9% indicating otherwise. Moreover, only 8.1% of the respondents said that the text they had read was hard to understand. ANOVAs were used to explore whether the treatments differed in terms of their credibility (F(6, 1579) = 0.69, p = 0.656) and/or incomprehensibility (F(6, 1579) = 0.95, p = 0.456), but no significant differences were identified. This finding underscores the validity of our experiment and results.

Third, to further explore the indication that more-populist citizens respond differently to the message than less-populist citizens, we calculated the association of populist attitudes with the response to questions about the credibility and incomprehensibility of the treatments: r = −0.204 (p < .001) and r = 0.140 (p < .001), respectively. Respondents with more populist attitudes regarded the treatments as less credible and harder to comprehend than people with a lower level of populist attitudes. The former finding is comparable with extant research showing that an anti-establishment perspective on the EU goes together with low trust in the EU (Van den Hoogen et al. Citation2022b, see also Van den Hoogen et al. Citation2022a), while the finding that populist respondents regard the experimental material harder to comprehend relates to the idea that populist attitudes are associated with possessing limited political knowledge (e.g. Van Kessel et al. Citation2021).

Fourth, as national identity related concerns are also often used as an explanation for opposing further European integration (e.g. Carey Citation2002; Ejrnaes and Jensen Citation2019; Luedtke Citation2005), we also explored whether nationalist attitudes moderate the effect of exposure to a proposal for the abolishment of EU member states’ right of veto on EU attitudes. The panel used to field our survey experiment included two items that could be used to that end in a previous survey (De Koster et al. Citation2020): ‘The world would be a better place if people from other countries were more like the Dutch’ and ‘Generally speaking, The Netherlands is a better country than most other countries’, both based on Davidov (Citation2011). Both were measured in 2020, and we used their mean score as a moderator (α = 0.64; M: 4.31; SD: 1.19). Similar to our findings for populist attitudes, OLS regression analyses did not show a significant interaction effect of nationalist attitudes with our treatment for any of the five distinct EU attitudes (see table S3 in the Online Supplementary Material).

4.3. Sensitivity analyses

Informed by the suggestion that removing respondents based on manipulation checks may bias results (Aronow et al. Citation2019; Montgomery et al. Citation2018), we did not exclude those who failed the checks in our main analyses. Yet, we applied a sensitivity analysis by excluding them, especially because of their remarkably high number: 122 respondents failed to identify the right textual treatment and 788 to recognise the correct medium (incorrect answers and ‘don’t knows’ combined). Reflecting on why roughly half of the respondents were unable to identify the right newspaper, we noted the following: 1) the subtlety of the manipulation, i.e. just the layout, font and heading, may have made this task difficult; and 2) the four answer categories of the manipulation check, i.e. two tabloids and two broadsheet newspapers, might also have caused this question to be harder to answer and, as a result, responsible for the high number of respondents who chose the ‘don’t know’ option (n = 389).

The results of the sensitivity analyses after excluding the high number of respondents who failed the manipulation checks were, nonetheless, very similar to those of our main analysis. In other words, no significant direct and interaction effects were identified (table S1 and table S2 in the online supplementary material). Moreover, excluding these respondents did not affect the results reported in of the main analysis, i.e. those exposed to an article in a newspaper known for its Eurosceptic stance had a more negative attitude towards EU membership, greater support for a Nexit and higher levels of disgust with the institution (Table S2 in the online supplementary material). The finding that the respondents who were unable to identify the newspaper correctly were affected equally by the article as those who were able to do so suggests that the Euroscepticism of the medium was, in general, processed unconsciously. We will elaborate on this further in the conclusion.

5. Conclusion

Informed by the literature, we tested whether exposing Dutch citizens to a report of plans for further EU integration that would result in additional loss of national sovereignty increased negative EU attitudes. Our pre-registered survey experiment, conducted among members of a high quality, nationally representative panel, demonstrated that those exposed to a proposal to abolish member states’ right of veto did not report more negative attitudes to the EU than those who were just informed about what this right of veto entailed.

There may be three reasons for this unexpected result. First, as we modelled our experimental treatment after a real-world news message, it might be that some respondents were already familiar with its contents. If that is indeed the case, it could be that an effect is only present among those not yet familiar with the message’s content, which could render the overall effect too small to detect. However, this seems unlikely, as the issue of abolishment of the right of veto was not extensively and structurally covered by Dutch media and neither hotly debated in the Dutch public sphere. In addition, even if the general content of the message was already familiar to some respondents, being exposed to the treatment would still have highlighted the salience of the issue relative to the respondents in the control condition.

Second, the issue chosen for exposing respondents to potential sovereignty loss might be too complex for inspiring feelings of infringement on national sovereignty. We did ensure that our treatment condition made explicit mention of concerns about the loss of sovereignty following the proposed abolition of the right of veto. Nevertheless, the procedures and processes relating to this right mostly occur ‘behind the scenes’, and the direct impact on citizens’ day-to-day lives may be quite subtle. It should, however, be noted that very few respondents said the text in the article they read was too difficult to understand. Moreover, we did not identify any differences in relation to comprehensibility between the control and treatment conditions. Future research could thus investigate whether other examples of national sovereignty loss have an impact on the public’s attitudes. This could be achieved in at least two ways, for example, by conducting: 1) survey experiments that adopt a similar approach, but use different examples, such as announcing an EU constitution, potential increases in its budget or the implementation of EU taxes; and 2) natural experiments that involve actual further EU integration in the future, possibly employing difference-in-difference analyses of the effects on public opinion.

Third, the influence of the Netherlands, as a net contributor to and founding member of the EU, might be overestimated by Dutch citizens. They may thus regard the prospect of sovereignty loss as less problematic, at least in comparison to citizens of member states that joined the EU later and are net beneficiaries, such as Greece, Portugal or Spain (Hobolt Citation2014), or those whose countries are experiencing an ‘illiberal turn’ that is the subject of strong criticism from EU officials, Poland and Hungary for instance (Krastev and Holmes Citation2018). The attitudes towards the EU of citizens in those member states might, consequently, become more negative if they are confronted with a potential loss of national sovereignty than is the case in the Netherlands. Future studies could investigate this issue by fielding a similar kind of experiment in those types of countries.

Next, in relation to the conditional treatment effects, we found that the interaction terms used to estimate whether the treatment especially leads to more negative EU attitudes among citizens with a high level of populist attitudes did not reach pre-registered levels of significance. Consequently, the associated hypotheses were not supported. It should, however, be noted that those interaction terms did affect all five dependent variables in the hypothesised directions, and that exposure to the proposal seemed to have a negative impact on the attitudes of the most populist citizens. This suggests that, in different circumstances, the prospect of sovereignty loss might strengthen the negative opinions on the EU of citizens who hold populist views. As populism in some countries is more intertwined with opposition to further European integration than in other ones (e.g. Kneuer Citation2018, see also Taggart and Pirro Citation2021), it is not unlikely that a similar experiment may yield stronger, or weaker, effects when fielded elsewhere. Future research that scrutinises this suggestion would thus be worthwhile.

In contrast to the case with populist attitudes, the type of newspaper did not shape in any way how the exposure to a proposed abolition of the right of veto affected attitudes towards the EU. It is, however, notable that our exploratory analyses did identify that the respondents exposed to the treatment in a Eurosceptic newspaper were more negative than those exposed to it in one that is not. We can draw two conclusions from this direct effect on attitudes to the EU of the type of newspaper employed: 1) a lack of internal validity is not a likely cause of the non-significant interaction with exposure to the proposal; and 2) a very subtle change in the layout of the messaging can have very noticeable effects, even when the content does not change. In terms of the latter, it is interesting to note that while roughly half of the respondents incorrectly identified the medium they were exposed to, this medium nevertheless affected their attitudes to the EU in a similar way to those who made the correct identification. In other words, the part played by the type of medium in shaping negative views on the EU seems to run deeper than the literature typically reports. Indeed, previous studies have reported that exposure to negative news on EU-related matters adversely affects opinions towards it (Galpin and Trenz Citation2017; van Spanje and de Vreese Citation2014; Vliegenthart et al. Citation2008). Our analysis, however, demonstrates that a non-negative article on these issues may even have such an impact in cases where it is published in a newspaper renowned for its Euroscepticism, irrespective of whether people are able to identify the medium correctly, but are exposed to it via subtle cues like its layout. Note that higher aversion to the EU after exposure to such subtle cues include reporting more negative emotions, which is measured as disgust. In other words: the most subtle hint at a Eurosceptic messenger can already increase an outspoken negative emotion towards the EU. Given the role played by the tabloid press in the Brexit vote in 2016 (e.g. Simpson and Startin Citation2022) and Euroscepticism more generally (e.g. Foos and Bischof Citation2021; Leruth et al. Citation2017), this finding makes an important contribution to the field. After all, it highlights the potential influence a Eurosceptic connotation of a medium could have on general attitudes towards the EU.

Generally, one could argue that the weak to non-existent effects found in this study reflect that many attitudes, including those on the EU (e.g. Kunst et al. Citation2022), hardly change due to events or policy changes. Especially because two aspects of our experiment made it likely to detect any policy-change induced attitude change if it actually occurred. First, it provides a realistic powerful manipulation (Kinder and Palfrey Citation1993: 27), by exposing respondents to a policy change with vast consequences for national sovereignty. Second, our experiment has high external validity (Barabas and Jerit Citation2010: 227), as the proposed policy change was presented in existing newspaper articles’ layout, using content based on real-life material. A future natural experiment utilising the actual abolishment of veto rights in case this would occur would be the litmus test for uncovering whether attitudinal change really does not occur due to such a profound policy change.

In summary, exposure to a proposal to abolish the right of veto of EU member states did not have a negative effect on the attitudes towards the institution of Dutch citizens, and nor was this outcome conditional on their populist attitudes or the Eurosceptic nature of the newspaper in which the proposal was published. Nevertheless, our findings also suggest that potential sovereignty loss might especially upset the most populist citizens. They, moreover, suggest that a subtle and unconscious association with the Eurosceptic character of a newspaper might already make its readers more Eurosceptic. Future research could uncover whether our findings depend on the specific issue used to expose respondents to potential sovereignty loss, and how far they travel beyond the Dutch case.

Ethics approval statement

Our study conforms with all relevant ethical regulations. In addition to Centerdata’s ethical regulations, our study was reviewed by and received ethical approval from the Ethics Review Committee of the Department of Public Administration and Sociology, Erasmus School of Social and Behavioural Sciences, Erasmus University Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Research data were collected from Centerdata’s LISS panel and are freely available for academic research purposes from the LISS Data Archive repository, which has the international CoreTrustSeal certification. Given reasons of privacy and ensuring a secure storage and responsible usage of the data, the data can only be accessed through the LISS Data Archive. A replication package that contains links to the data, as well as the code that enables reproducing our results, can be found here: https://surfdrive.surf.nl/files/index.php/s/TpyBJStqk1rBh24.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Link to the OSF registration: https://osf.io/2mv7a?view_only=ffca4f6b189f4111bda0961fde991688

2 Link to the data and code that can be used to replicate our results: https://surfdrive.surf.nl/files/index.php/s/TpyBJStqk1rBh24

Bibliography

- Abts, K., Etienne, T., Kutiyski, Y. and Krouwel, A. (2023) EU-sentiment Predicts the 2016 Dutch Referendum Vote on the EU’s Association with Ukraine Better Than Concerns About Russia or National Discontent, European Union Politics Advance online publication.

- Akkerman, A., Mudde, C. and Zaslove, A. (2014) ‘How populist are the people? Measuring populist attitudes in voters’, Comparative Political Studies 47(9): 1324–53.

- Anderson, C. J. and Hecht, J. D. (2018) ‘The preference for Europe: public opinion about European integration since 1952’, European Union Politics 19(4): 617–38.

- Aronow, P. M., Baron, J. and Pinson, L. (2019) ‘A note on dropping experimental subjects who fail a manipulation check’, Political Analysis 27(4): 572–89.

- Azrout, R., van Spanje, J. and de Vreese, C. (2011) ‘Talking Turkey: anti-immigrant attitudes and their effect on support for Turkish membership of the EU’, European Union Politics 12(1): 3–19.

- Azrout, R., van Spanje, J. and de Vreese, C. (2012) ‘When news matters: media effects on public support for European union enlargement in 21 Countries’, Journal of Common Market Studies 50(5): 691–708.

- Baden, C. and De Vreese, C. H. (2008) ‘Making sense: a reconstruction of people’s understandings of the European constitutional referendum in The Netherlands’, Communications 33(2): 117–45.

- Bakker, B. N. and De Vreese, C. H. (2016) ‘Personality and European Union attitudes: relationships across European Union attitude dimensions’, European Union Politics 17(1): 25–45.

- Barabas, J. and Jerit, J. (2010) ‘Are survey experiments externally valid?’, American Political Science Review 104(2): 226–42.

- Baute, S., Meuleman, B., Abts, K. and Swyngedouw, M. (2018) ‘European integration as a threat to social security: another source of Euroscepticism?’, European Union Politics 19(2): 209–32.

- BNR (2021, March 25) “Afschaffen vetorecht geeft Europa meer slagkracht” BNR Nieuwsradio. https://www.bnr.nl/nieuws/internationaal/10436313/spanje-en-nederland-willen-af-van-vetorecht-eu.

- Bolsen, T., Druckman, J. N. and Cook, F. L. (2014) ‘The influence of partisan motivated reasoning on public opinion’, Political Behavior 36(2): 235–62.

- Boomgaarden, H. G., Schuck, A. R. T., Elenbaas, M. and de Vreese, C. H. (2011) ‘Mapping EU attitudes: conceptual and empirical dimensions of Euroscepticism and EU support’, European Union Politics 12(2): 241–66.

- Borriello, A. and Brack, N. (2019) ‘‘I want my sovereignty back!’ a comparative analysis of the populist discourses of podemos, the 5 star movement, the FN and UKIP during the economic and migration crises’, Journal of European Integration 41(7): 833–53.

- Brambor, T., Roberts Clark, W. and Golder, M. (2006) ‘Society for political methodology understanding interaction models: improving empirical analyses’, Source: Political Analysis 14(1): 63–82.

- Brosius, A., van Elsas, E. J. and de Vreese, C. H. (2019) ‘Trust in the European Union: effects of the information environment’, European Journal of Communication 34(1): 57–73.

- Carey, S. (2002) ‘Undivided loyalties: is national identity an obstacle to European integration?’, European Union Politics 3(4): 387–413.

- Carrieri, L. and Vittori, D. (2021) ‘Defying Europe? The Euroscepticism of radical right and radical left voters in Western Europe’, Journal of European Integration. 43(8): 955–71.

- Clifford, S., Sheagley, G. and Piston, S. (2021) ‘Increasing precision without altering treatment effects: repeated measures designs in survey experiments’, American Political Science Review 115(3): 1048–65.

- Davidov, E. (2011) ‘Nationalism and constructive patriotism: a longitudinal test of comparability in 22 countries with the ISSP’, International Journal of Public Opinion Research 23(1): 88–103.

- De Koster, W. and Achterberg, P. (2015) Comment on ‘Providing information promotes greater public support for potable recycled water’ by Fielding, K.S. and Roiko, A.H., 2014 [Water Research 61, 86-96], Water Research 84: 372–4.

- De Koster, W., Achterberg, P. and Ivanova, N. (2016) ‘Reconsidering the impact of informational provision on opinions of suspended sentences in The Netherlands: the importance of cultural frames’, Crime and Delinquency 62(11): 1528–39.

- De Koster, W., van den Hoogen, E., Lindner, T. and van der Waal, J. (2020) Political and Social Attitudes in the Netherlands [Dataset], Tilburg: Centerdata.

- De Vreese, C. H. (2007) ‘A spiral of Euroscepticism: the media’s fault?’, Acta Politica 42(2–3): 271–86.

- De Vreese, C. H., Azrout, R. and Boomgaarden, H. G. (2019) ‘One size fits all? Testing the dimensional structure of EU attitudes in 21 Countries’, International Journal of Public Opinion Research 31(2): 195–219.

- De Vreese, C. H. and Boomgaarden, H. (2006a) ‘News, political knowledge and participation: the differential effects of news media exposure on political knowledge and participation’, Acta Politica 41(4): 317–41.

- De Vreese, C. H. and Boomgaarden, H. G. (2006b) ‘Media effects on public opinion about the enlargement of the European Union’, Journal of Common Market Studies 44(2): 419–36.

- De Vreese, C. H. and Boomgaarden, H. G. (2006c) ‘Media message flows and interpersonal communication the conditional nature of effects on public opinion’, Communication Research 33(1): 19–37.

- De Vries, C. and Steenbergen, M. (2013) ‘Variable opinions: the predictability of support for unification in European mass Publics’, Journal of Political Marketing 12(1): 121–41.

- Dutceac Segesten, A. and Bossetta, M. (2019) ‘Can Euroscepticism contribute to a European public sphere? The europeanization of media discourses on Euroscepticism across six countries’, Journal of Common Market Studies 57(5): 1051–70.

- Ejrnæs, A. and Jensen, M. D. (2019) ‘Divided but united: explaining nested public support for European integration’, West European Politics 42(7): 1390–419.

- Foos, F. and Bischof, D. (2021) ‘Tabloid media campaigns and public opinion: quasi-experimental evidence on Euroscepticism in England’, American Political Science Review 115(1): 232–248.

- Gabel, M. (1998) ‘Public support for European integration: an empirical test of five theories’, The Journal of Politics 60(2): 333–54.

- Galpin, C. and Trenz, H.-J. (2017) ‘The spiral of Euroscepticism: media negativity, framing and opposition to the EU. In J. A. Trenz & J. de Wilde (Eds.), Euroscepticism, Democracy and the Media (pp. 49–72), London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gitlin, T. (1980) The Whole World is Watching: Mass Media in the Making & Unmaking of the new Left, Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Hall, S. (1980) ‘Encoding, decoding.’ In C. for C. C. Studies (Ed.), Culture, Media, Language. Working Papers in Cultural Studies, 1972-1979 (pp. 112–121), Routledge.

- Hameleers, M. (2019) ‘Partisan media, polarized audiences? A qualitative analysis of online political news and responses in the United States, U.K., and The Netherlands’, International Journal of Public Opinion Research 31(3): 485–505.

- Hobolt, S. B. (2007) ‘Taking cues on Europe? Voter competence and party endorsements in referendums on European integration’, European Journal of Political Research 46(2): 151–82.

- Hobolt, S. B. (2014) ‘Ever closer or ever wider? Public attitudes towards further enlargement and integration in the European Union’, Journal of European Public Policy 21(5): 664–80.

- Hobolt, S. B. and Brouard, S. (2011) ‘Contesting the European Union? Why the Dutch and the French rejected the European constitution’, Political Research Quarterly 64(2): 309–22.

- Hooghe, L. and Marks, G. (2004) ‘Does identity or economic rationality drive public opinion on European integration?’, Political Science and Politics 37(3): 415–20.

- Janssen, J. I. (1991) ‘Postmaterialism, cognitive mobilization and public support for European Integration’, British Journal of Political Science 21(4): 443–68.

- Jayet, C. (2020) ‘The meaning of the European Union and public support for European integration’, Journal of Common Market Studies 58(5): 1144–64.

- Kahan, D. (2010) ‘Fixing the communications failure’, Nature 463(7279): 296–297.

- Kepplinger, H. M. (2012) Effects of the News Media on Public Opinion, The SAGE Handbook of Public Opinion Research (pp. 192–204).

- Kinder, D. R. and Palfrey, T. R. (Eds.). (1993) Experimental Foundations of Political Science, University of Michigan Press.

- Kneuer, M. (2018) ‘The tandem of populism and Euroscepticism: a comparative perspective in the light of the European crises’, Contemporary Social Science 14(1): 26–42.

- Krastev, I. and Holmes, S. (2018) ‘Imitation and its discontents’, Journal of Democracy 29(3): 117–28.

- Kunst, S., Kuhn, T. and van de Werfhorst, H. G. (2022) ‘As the twig is bent, the tree is inclined? The role of parental versus own education for openness towards globalisation’, European Union Politics 24(2): 264–85.

- Leruth, B., Kutiyski, Y., Krouwel, A. and Startin, N. J. (2017) ‘Does the information source matter? Newspaper readership, political preferences and attitudes towards the EU in the UK, France and The Netherlands.’ In J. A. Trenz & J. de Wilde (Eds.), Euroscepticism, Democracy and the Media, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 95–120.

- Lubbers, M. (2008) ‘Regarding the Dutch “nee” to the European constitution: a test of the identity, utilitarian and political approaches to voting “no.”’, European Union Politics 9(1): 59–86.

- Luedtke, A. (2005) ‘European integration, public opinion and immigration policy: testing the impact of national identity’, European Union Politics 6(1): 83–112.

- Marquart, F., Brosius, A. and de Vreese, C. (2019) ‘United feelings: the mediating role of emotions in social media campaigns for EU attitudes and behavioral intentions’, Journal of Political Marketing 21(1): 1–27.

- Marquart, F., Goldberg, A. C., van Elsas, E. J., Brosius, A. and de Vreese, C. H. (2018) ‘Knowing is not loving: media effects on knowledge about and attitudes toward the EU’, Journal of European Integration 41(5): 1–15.

- Michailidou, A. (2015) ‘The role of the public in shaping EU contestation: Euroscepticism and online news media’, International Political Science Review 36(3): 324–36.

- Montgomery, J. M., Nyhan, B. and Torres, M. (2018) ‘How conditioning on posttreatment variables can ruin your experiment and what to do about it’, American Journal of Political Science 62(3): 760–75.

- Nielsen, J. H. (2018) ‘The effect of affect: how affective style determines attitudes towards the EU’, European Union Politics 19(1): 75–96.

- Pirro, A. and van Kessel, S. (2017) ‘United in opposition? The populist radical right’s EU-pessimism in times of crisis’, Journal of European Integration 39(4): 405–20.

- Scherpenzeel, A. (2009) Start of the LISS Panel: Sample and recruitment of a probability-based internet Panel, Tilburg: Centerdata, 1–9.

- Schuck, A. R. T. and De Vreese, C. H. (2008) ‘The Dutch no to the EU constitution: assessing the role of EU skepticism and the Campaign’, Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 18(1): 101–28.

- Schuck, A. R. T., Vliegenthart, R., Boomgaarden, H. G., Elenbaas, M., Azrout, R., van Spanje, J. and de Vreese, C. H. (2013) ‘Explaining campaign news coverage: How medium, time, and context explain variation in the media framing of the 2009 European parliamentary elections’, Journal of Political Marketing 12(1): 8–28.

- Simpson, K. and Startin, N. (2022) ‘Tabloid tales: how the British tabloid press shaped the Brexit vote’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 60(1): 36–53.

- Taber, C. S. and Lodge, M. (2012) ‘Motivated skepticism in the evaluation of political beliefs (2006)’, Critical Review 24(2): 157–84.

- Taggart, P. and Pirro, A. L. P. (2021) ‘European populism before the pandemic: ideology, Euroscepticism, electoral performance, and government participation of 63 parties in 30 countries’, Italian Political Science Review/Rivista Italiana Di Scienza Politica 51: 281–304.

- Toshkov, D. and Krouwel, A. (2022) ‘Beyond the U-curve: citizen preferences on European integration in multidimensional political space’, European Union Politics 23(3): 462–88.

- Van den Hoogen, E., Daenekindt, S., de Koster, W. and van der Waal, J. (2022b) ‘Support for European Union membership comes in various guises: evidence from a correlational class analysis of novel Dutch survey data’, European Union Politics 23(3): 489–508.

- Van den Hoogen, E., de Koster, W. and van der Waal, J. (2022a) ‘What does the EU actually mean to citizens? An in-depth study of Dutch citizens’ understandings and evaluations of the European Union’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 60(5): 1432–48.

- Van der Brug, W., van der Meer, T. and van der Pas, D. (2018) ‘Voting in the Dutch ‘Ukraine-referendum’: a panel study on the dynamics of party preference, EU-attitudes, and referendum-specific considerations’, Acta Politica 53(4): 496–516.

- Van Kessel, S., Sajuria, J. and Van Hauwaert, S. M. (2021) ‘Informed, uninformed or misinformed? A cross-national analysis of populist party supporters across European democracies’, West European Politics 44(3): 585–610.

- Van Noord, J., de Koster, W. and van der Waal, J. (2018) ‘Order please! How cultural framing shapes the impact of neighborhood disorder on law-and-order voting’, Political Geography 64: 73–82.

- Van Rijn, M., Haverkate, M., Achterberg, P. and Timen, A. (2019) ‘The public uptake of information about antibiotic resistance in the Netherlands’, Public Understanding of Science 28(4): 486–503.

- Van Spanje, J. and de Vreese, C. (2014) ‘Europhile media and Eurosceptic voting: effects of news media coverage on Eurosceptic voting in the 2009 European parliamentary elections’, Political Communication 31(2): 325–54.

- Verbalyte, M. and von Scheve, C. (2018) ‘Feeling Europe: political emotion, knowledge, and support for the European Union’, Innovation 31(2): 162–88.

- Vliegenthart, R., Schuck, A. R. T., Boomgaarden, H. G. and de Vreese, C. H. (2008) ‘News coverage and support for European integration, 1990-2006’, International Journal of Public Opinion Research 20(4): 415–6.

- Vössing, K. (2015) ‘Transforming public opinion about European integration: elite influence and its limits’, European Union Politics 16(2): 157–75.

- Wojcieszak, M., Azrout, R. and de Vreese, C. (2018) ‘Waving the Red Cloth’, Public Opinion Quarterly 82(1): 87–109.

- Yordanova, N., Angelova, M., Lehrer, R., Osnabrügge, M. and Renes, S. (2020) ‘Swaying citizen support for EU membership: evidence from a survey experiment of German voters’, European Union Politics 21(3): 429–50.

- Zaller, J. R. (1992) The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.