?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Recent research shows that firms and jobs are more important for understanding gender wage inequalities than individual-level and occupational-level attributes. I investigate how two mechanisms derived from relational inequality theory, opportunity hoarding and exploitation, affect within-firm gender wage gaps. First, men might exclude women from high-paying firms or jobs (i.e. opportunity hoarding), resulting in gender wage inequalities. Second, male managers might use their relational power to redistribute wages from females to males (exploitation). Increasing the number of female managers might stop this exploitation. While previous literature focused on the effect of female managers on the gender wage gap, I contribute to the literature by also considering the impact of female managers on males’ wages theoretically and empirically. Using German linked employer-employee data and fixed-effect regressions at the firm and job levels, I find evidence for opportunity hoarding at both the firm and the job levels. For the exploitation mechanism, female managers increase females’ wages and lower males’ wages, suggesting the existence of the exploitation mechanism. Further analyses show that the increases in females’ wages are proportional to the decreases in males’ wages. Thus, I find evidence for female managers redistributing males’ wages to females.

Introduction

In recent years, the narrowing of the gender wage gap has slowed or even stalled (England et al. Citation2020). Since closing gender inequalities is an important goal of policymakers in most western countries, understanding processes contributing to the gender wage gap is essential for effectively reaching this goal and closing gender wage inequalities. Scholars have identified a wide range of factors contributing to gender wage gaps at the occupational level, such as segregation (Grönlund and Magnusson Citation2016), and at the individual level, such as human capital (Blau and Kahn Citation2017). Recent scholarship shows that firmsFootnote1 and jobs, i.e. occupations within firms, are more important for understanding wage stratification than occupations or individual attributes (Avent-Holt et al. Citation2020; Penner et al. Citation2023), which is in line with Baron and Bielby’s call to ‘bring the firm back in’ (Baron and Bielby Citation1980).

Following this call, researchers recently investigated factors contributing to gender wage inequality at the firm level, such as segregation (e.g. Avent-Holt and Tomaskovic-Devey Citation2012), organizational practices (van der Lippe, van Breeschoten, and van Hek Citation2019; Zimmermann and Collischon Citation2023), and female managers (e.g. Van Hek and Van Der Lippe Citation2019; Zimmermann Citation2022). Recent theoretical developments also highlight the importance of organizations for creating and sustaining inequality, such as the relational inequality theory (RIT) (Tomaskovic-Devey and Avent-Holt Citation2019).

According to RIT, relational claims-making is an essential mechanism creating inequalities within workplaces through social relationships (Peters and Melzer Citation2022; Tomaskovic-Devey and Avent-Holt Citation2019). In combination with status hierarchies among groups (e.g. Ridgeway Citation2014), categorical distinctions (e.g. based on gender or nationality) can legitimize claims-making to organizational resources, such as pay or promotions (Peters and Melzer Citation2022). With respect to gender, men and women might, intentionally or not, try to aid same-gender colleagues in claiming organizational resources. If men are a superordinate status category in a workplace, then men preferably sharing resources with other men can result in the exploitation of women by two mechanisms: (i) opportunity hoarding and (ii) exploitation, thus creating inequality between groups (Avent-Holt and Tomaskovic-Devey Citation2010; Tilly Citation1998).

First, regarding opportunity hoarding, men might preferably give access to positions in high-paying firms or high-paying jobs to other men, leading to the exclusion of women from claiming these opportunities. The resulting segregation into differently paid firms or jobs creates inequality between males and females. Second, regarding exploitation, men could use their relational power to help other men make claims on workplace opportunities more effectively than women. Exploiting their relational power advantage, men can create inequality by allocating organizational resources disproportionally to other men. This exploitation increases males’ wages at the expense of females’ wages (Avent-Holt and Tomaskovic-Devey Citation2012).

In this study, I investigate gender inequalities in organizations using the RIT framework. First, I test opportunity hoarding by investigating gender wage gap differences at the labour market level, firm level, and job level. The differences between these gaps show whether women disproportionally work in lower-paid firms and whether women work in lower-paid jobs inside of firms compared to men. This segregation into lower paid firms or jobs might be the result of opportunity hoarding. By investigating opportunity hoarding at these two levels, I can investigate at which level segregation contributes to wage inequalities between men and women.

Second, I investigate the exploitation mechanism, by which men use relational power to get advantages in claims-making. Since organizational resources are scarce, group members with high status can help subordinates to make claims on workplace opportunities. The ratio of high-status to low-status group members can represent relational power, as high-status group members can help low-status members to make claims (Avent-Holt and Tomaskovic-Devey Citation2010; Avent-Holt and Tomaskovic-Devey Citation2012). In contrast to recent literature focusing on the presence of female managers (e.g. Zimmermann Citation2022), RIT shifts the focus to relational power of groups relating to categorical distinctions inside organizations.Footnote2 Following Avent-Holt and Tomaskovic-Devey (Citation2010), I use the difference between the female share of managers and the female share of workers, i.e. non-managerial workers, as an indicator of female relational power. Furthermore, by taking opportunity hoarding at the job level into account, I can extract the effect of exploitation on men and women net of sorting into different occupations within firms.

Third, I explicitly consider wage redistributions from males to females theoretically and empirically. Previous literature focuses on the effect of female managers on the gender wage gap (e.g. Abendroth et al. Citation2017; Van Hek and Van Der Lippe Citation2019) without theoretically considering potential effects on males’ wages. The RIT framework highlights the scarceness of organizational resources. Wage decreases for females accompany male wage gains through exploitation since more organizational resources awarded to men lead to less organizational resources awarded to women (Tomaskovic-Devey and Avent-Holt Citation2019). Thus, reducing exploitation should lead to a convergence of male and female wages by raising females’ wages and lowering the wages of males. I can test both sides of the exploitation mechanism by directly analyzing a potential redistribution of wages.

To investigate my research question, I employ a longitudinal linked employer-employee panel dataset from Germany, the Linked-Employer-Employee-Data (LIAB QM2 9319) (Ruf et al. Citation2021b) of the Institute for Employment Research (IAB).Footnote3 This unique dataset encompassing 2.632 private-sector firms and 1,252,125 worker observations contains rich organizational-level information about a firm, such as information about managers, collective agreements, and high-quality administrative worker data, such as wages and occupations.

I contribute to the literature in at least two ways. First, by investigating exploitation at the job level, I can extract the effect of exploitation net of segregation. Second, I provide, to the best of my knowledge, first evidence on the redistribution aspect of the exploitation mechanism. Since most previous scholarship on RIT investigating gender or migrant wage inequalities is cross-sectional (e.g. Avent-Holt and Tomaskovic-Devey Citation2012; Melzer et al. Citation2018; Peters and Melzer Citation2022), in-firm wage effects on males or natives cannot be estimated. Longitudinal data allows me to investigate whether males’ wages inside firms are affected by the relative female bargaining power. Since wage inequalities according to exploitation are based on redistributions between groups, examining both wage effects on males and females is essential for thoroughly investigating this mechanism.

Relational inequality theory

Scholars have long recognized the importance of organizations in generating and sustaining inequalities (Acker Citation2006; Baron and Bielby Citation1980; Tilly Citation1998; Tomaskovic-Devey and Avent-Holt Citation2019). In the RIT framework, relational claims-making is a central mechanism generating inequalities (Tomaskovic-Devey and Avent-Holt Citation2019). Relational claims-making operates via social relationships within workplaces (Peters and Melzer Citation2022): Workers make claims to workplace resources, such as pay. Employers judge these claims’ legitimacies and then either grant or dismiss the claims (Peters and Melzer Citation2022; Tomaskovic-Devey and Avent-Holt Citation2019). While competence or productivity might increase legitimacy to these claims, RIT emphasizes the role of categorical distinctions in combination with status hierarchies based on these distinctions for the claims making process (Peters and Melzer Citation2022). Belonging to a group with assumed high status can legitimize claims to organizational resources regardless of actual competence or productivity (Peters and Melzer Citation2022; Ridgeway Citation2014; Tilly Citation1998).

Categorical distinctions might be highlighted or dampened by the intersection of institutional, organizational, and individual contexts (Melzer et al. Citation2018). Since local status hierarchies and interactional norms are developed inside organizations (DiTomaso et al. Citation2007), the local organizational context influences categorical processes leading to between-group distinctions (Melzer et al. Citation2018). In this context, gender is an essential and salient attribute on which people categorize and distinguish socially (England Citation2010; Avent-Holt and Tomaskovic-Devey Citation2012). In summary, the local organizational context leads to substantial variation in gender wage inequalities between organizations, creating distinct inequality regimes (Acker Citation2006; Tomaskovic-Devey and Avent-Holt Citation2019).

Opportunity hoarding

Building on Marx (Citation1867), Weber (Citation1947 [1924]), and Tilly (Citation1998), among others, RIT offers two potential mechanisms for how categorical distinctions in combination with status hierarchies based on these distinctions lead to inequalities between groups (Tomaskovic-Devey and Avent-Holt Citation2019). First, in-group members might prefer sharing access to high-paying firms or jobs with other in-group members, resulting in the exclusion of out-group members in these firms and jobs.Footnote4 This opportunity hoarding leads to segregated workplaces. Second, more powerful actors could disproportionally award in-group members with organizational resources. This exploitation would lead to inequality at the expense of less powerful actors (Tilly Citation1998; Tomaskovic-Devey and Avent-Holt Citation2019).

In the context of gender wage inequalities, men might prefer to share opportunities for joining high-paying firms or working high-paying jobs with other men, preventing women from entering high-paying jobs or firms. Organized social closure (Reskin Citation1988; Tomaskovic-Devey Citation1993) and self-selection into different jobs or firms (Card et al. Citation2016; Ridgeway Citation1997) can contribute to opportunity hoarding (Tilly Citation1998; Avent-Holt and Tomaskovic-Devey Citation2012). If men and women segregate into differently paying jobs and firms, gender wage inequality at the firm or job level might be low, while the gender wage gap at the national level may be high. Thus, to test opportunity hoarding, I investigate gender wage gaps at the national level, within firms, and within jobs. Differences in gender wage inequalities between these levels could indicate segregation of women into less paying firms or jobs, leading to the hypotheses:

When segregation at the firm level is more prevalent, the within-firm gender wage gap is narrower than the overall gender wage gap (Hypothesis 1a).

When segregation at the job level is more prevalent, the within-job gender wage gap is narrower than the overall gender wage gap (Hypothesis 1b).

Exploitation

While opportunity hoarding assumes that in-group and out-group members get paid similar wages working the same job, the exploitation mechanism might lead to wage inequalities between groups in the same jobs. Generalizing from Marx (Citation1867), exploitation is defined as an actor appropriating value at the expense of others (Avent-Holt and Tomaskovic-Devey Citation2012; Tilly Citation1998). High-status in-group members can help other in-group members to make claims on workplace opportunities, such as pay (Tomaskovic-Devey and Avent-Holt Citation2019). Thus, the relative status composition, i.e. the ratio of high-status to low-status in-group members, represents the relational power of an actor (Tomaskovic-Devey and Avent-Holt Citation2019). An essential determinant of relational power is the hierarchical status of in-group members in an organization. Since managers have a high hierarchical status, relational power can be represented by the difference between a group’s relative representation in management and non-managerial jobs in a firm (Avent-Holt and Tomaskovic-Devey Citation2010).

In the context of gender wage inequalities, male managers might allocate scarce organizational resources disproportionally to male non-managerial workers. This exploitation increases males’ wages at the expense of females’ wages, resulting in gender wage inequalities (Avent-Holt and Tomaskovic-Devey Citation2012). Since either more female managers or fewer female non-managerial workers increase female relational power, I expect that an increase in the share of female managers relative to the share of female workers increases females’ wages, leading to hypothesis 2a.

An increase in female relational power increases females’ wages within firms and jobs (Hypothesis 2a).

According to the exploitation mechanism, high male wages result from disproportionally allocating scarce organizational resources to men at the expense of women (Tomaskovic-Devey and Avent-Holt Citation2019). Thus, increases in female bargaining power and resulting increases in females’ wages should be accompanied by wage decreases for men. This redistribution of organizational resources between groups is essential for the exploitation mechanism as organizational resources are scarce (Tomaskovic-Devey and Avent-Holt Citation2019). This redistribution leads to hypothesis 2b.

An increase in female relational power reduces males’ wages within firms and jobs (Hypothesis 2b).

Relational power might have different effects at different levels of job qualifications. Educational qualifications and job sorting are tightly linked in Germany (DiPrete and McManus Citation1996). Thus, employees with lower educational qualifications usually work in less-qualified jobs that pay less. Employers might show less resistance to wage increases for lower qualified female workers as increases for this group are less costly for employers (Abendroth et al. Citation2017). Previous research for Germany (Abendroth et al. Citation2017; Zimmermann Citation2022) shows that especially lower qualified female workers benefit from the presence of female managers. The different effects per qualification level lead to the following hypothesis:

An increase in female relational power increases wages of lower-qualified females without a university degree within firms and jobs stronger than for higher-qualified females with a university degree (Hypothesis 2c).

Low-qualified workers have less relational power than higher qualified workers (Tomaskovic-Devey and Avent-Holt Citation2019) and can be more easily replaced. Thus, low qualified male workers’ wages might be more strongly redistributed as higher qualified male workers might more effectively prevent wage decreases. Previous research mainly points towards a redistribution from workers with less relational power to workers with more relational power (Tomaskovic-Devey and Avent-Holt Citation2019), such as less senior to more senior workers (Liu et al. Citation2010) or less qualified to more qualified workers (Sakamoto and Kim Citation2010). These considerations lead to the following hypothesis:

An increase in female relational power reduces wages of lower-qualified males without a university degree within firms and jobs stronger than for higher-qualified males with a university degree (Hypothesis 2d).

The German institutional setting

Firms are embedded into the national institutional setting, which might limit managerial discretion in allocating organizational resources to different groups (Avent-Holt and Tomaskovic-Devey Citation2010). For example, wages in the private sector are mainly determined by individual-level or workplace-level negotiations (Peters and Melzer Citation2022). In contrast to the negotiable private sector wages, the public sector features centralized and formalized pay scales that mainly depend on seniority (Peters and Melzer Citation2022). Thus, I focus on private sector firms to identify the role of female relational power in individual- and workplace-level negotiations.

In the private sector, firms might also have collective wage agreements which set wages in jobs and prevent arbitrarily setting wages between groups (Tomaskovic-Devey and Avent-Holt Citation2019). Another institutional feature of Germany is the prevalence of works councils, which increase workers’ bargaining power, especially vulnerable ones. Collective agreements and works councils should lower gender wage inequalities because they leave fewer opportunities for exploitation in firms. I assume that the impact of relational power on earnings is potentially larger in Germany than in other Western countries because Germany had the fifth highest gender wage gap in Europe in 2020 (Eurostat Citation2022).

Data and measurements

Data

To test my hypotheses, I employ German longitudinal linked employer-employee data (LIAB QM2 9319) (Ruf et al. Citation2021b, Citation2021a; Umkehrer Citation2017) provided by the Institute for Employment Research (IAB). This representative dataset comprises yearly surveyed firm-level information on employment-related topics, such as management composition, collective agreements, and works councils (Ruf et al. Citation2021a). The LIAB QM2 9319 is a stratified random sample drawn from all firms in Germany employing at least one employee liable to social security as of 30 June in the previous year (Ruf et al. Citation2021a). The face-to-face interviews were conducted mainly by professional interviewers. Since most interview respondents had managerial jobs, high data quality can be assumed.

My analysis focuses on the years 2012, 2014, 2016, and 2018 because information about management composition is available in these years.Footnote5 I merge the survey data at the firm level to administrative employment records of all employees liable to social security working in the surveyed firms. I focus on private sector firms with at least ten employees that employ at least one full-time male and female worker between the ages of 20 and 60 years in every surveyed year. I exclude managers according to occupational codes to avoid managers’ wages biasing my results, as the hypotheses are targeted at the non-managerial employee level. Furthermore, I focus on full-time workers since the data lacks information on the exact number of working hours. Finally, I exclude firms with missing information in one of the variables outlined in the control variables section. After these restrictions, my balanced panel sample comprises 2,638 firms, 475,427 unique full-time workers, and 1,252,125 full-time worker-year observations.

Measurements

Wages

My dependent variable is a worker’s daily gross wage in Euros, which is drawn from social security contributions and deflated to the year 2015. In contrast to survey-based data, this information is not subject to misreporting or selective non-response (Avent-Holt et al. Citation2020; Valet et al. Citation2019). Since wage information is censored at the upper earnings limit for statutory pension insurance, I impute the deflated wage separately by gender, region (location in East and West Germany), and calendar year using individual-level control variables (Stüber et al. Citation2023). To eliminate randomly generated outliers, I censor the imputed wage at ten times the 99th percentile (€757.53 per day).

Jobs

Detailed information about occupations is essential to identify jobs. Following the literature (Avent-Holt et al. Citation2020; Penner et al. Citation2023), I use the 3-digit occupational code to distinguish between 140 occupations, enabling a fine-grained identification of jobs. Using administrative information on occupations circumvents problems of survey data (Avent-Holt et al. Citation2020), i.e. reporting and coding errors (Speer Citation2016). As a robustness check, I also employ 4-digit occupational codes distinguishing between 540 occupations (Ruf et al. Citation2021a).

Female relational power

Relational power for females in a firm is represented by a firm’s relative gender composition, i.e. the difference between the female share of managers and the fulltime-equivalent female share of non-managerial workers (Avent-Holt and Tomaskovic-Devey Citation2010).

The information about the female share of managers is calculated from the survey data because administrative data does not include managers not liable to social security contributions, such as executives and owners of a firm (Zimmermann Citation2022). The survey data divides the management into two levels: executives and supervisors. I calculate the female management share by dividing the number of female managers in all management levels by the number of managers in all management levels. I calculate the fulltime-equivalent female share of non-managerial workers from all workers liable to social security in a firm whose occupational code does not indicate a managerial occupation. I weigh full-time workers as 1 and part-time workers as 0.5 since information about exact working hours is not available. See Appendix Figure A1 for the distribution of female relational power in a firm. As a robustness check, I also calculate relational power separately by management level.

Control variables

Following the literature investigating wage inequalities in Germany using RIT (Melzer et al. Citation2018; Abendroth et al. Citation2017), I control for demographic and human capital variables at the individual level, i.e. age in years, its square, three dummies for education, tenure in years, and labour market experience in years. I consider 140 occupations at the occupational level in models without job-fixed effects. At the firm level, I account for firm-fixed effects, which control for all time-constant firm-level variables (Abendroth et al. Citation2017). For time-variant variables at the firm level, I consider the log number of employees; a firm’s self-reported profit assessment; full-time equivalent sharesFootnote6 of highly-qualified workers (i.e. workers with a university degree), female workers, and fixed-term workers; share of part-time workers; the existence of a works council; collective agreements at the firm-level and the sector-level (Zimmermann Citation2022). To take the German institutional setting into account, I also control for the interaction of female and collective agreements as well as the existence of a works council, as these variables theoretically affect gender wage inequalities (Tomaskovic-Devey and Avent-Holt Citation2019). Finally, I control for dummies for the observed year. See Appendix Table A1 for a more detailed description of these variables and Appendix Table A2 for summary statistics of the variables.

Analytical strategy

To estimate the relationship between gender wage inequalities, segregation, and females’ relational power within firms, I employ multilevel linear regression models with fixed effects at the firm level and job level (Wooldridge Citation2010). Since the theory focuses on processes within organizations, my estimand is the association between female relational power in a firm and the within firm or within job gender wage gap (Lundberg et al. Citation2021). The fixed effects model is equivalent to the also often employed hierarchical linear model except for using a fixed instead of a random effect at the firm or job level (Melzer et al. Citation2018). Firm- and job-fixed effects consider unobserved time-constant differences between firms or jobs (Rabe-Hesketh and Skrondal Citation2012), such as the industry sector. The female coefficient represents the gender wage gap at the sample mean because I demean the variables relational power, works council, and collective agreements before interacting them with the undemeaned female dummy (Imbens and Wooldridge Citation2009).

To estimate the effects of segregation into firms and jobs, I first estimate model (1) without control variables to estimate the raw gender wage gap. I add stepwise individual-level control variables (model (2)), occupation-level fixed effects (model (3)), firm-level control variables and firm-fixed effects (model (4)), and finally, job-level fixed effects (model (5)) to estimate gender wage inequalities at different stages of the labour market. For example, adding firm-fixed effects controls for the average wage level within a firm, i.e. sorting into differently paid firms. Thus, when the gender wage gap narrows after adding firm-fixed effects, the results indicate that females work in lower paid firms. Using this commonly used strategy to identify the effect of segregation (e.g. Peters and Melzer Citation2022; Melzer et al. Citation2018), I can test hypotheses 1a and 1b, i.e. the segregation of females into less-paying firms and jobs.

Models (4) and (5) also include my variable of interest, female relational power in a firm, and its interaction with female. In these models, I test hypotheses 2a and 2b, i.e. whether increasing female relational power increases females’ wages and decreases males’ wages. Since the theory assumes redistribution between groups within firms or jobs, I use the models including firm- or job-fixed effects to analyze hypothesis 2a and 2b. To provide evidence on hypotheses 2c and 2d, I split the sample into lower-qualified workers, i.e. workers without a university degree, and higher-qualified workers, i.e. workers with a university degree. To calculate the differences of these effects and investigate hypotheses 2c and 2d, I estimate a three-way interacted model.

In models (4) and (5) of the main results and in the regressions to test hypotheses 2c and 2d, the main effect of female relational power represents the association between female relational power and men’s wages. The interaction of this coefficient with female represents the difference in the coefficient between men and women, i.e. the association with the gender wage gap among workers. The average marginal effect, which is the sum of the main and interaction effects, represents the total association between female relational power and women’s wages.

Results

To measure opportunity hoarding, I calculate gender wage gaps with different control variables. At first, I calculate the raw gender wage gap without any control variables. Column 1 of shows that my sample’s raw gender wage gap is 19.9% (exp(−0.222)−1), which is higher than the unadjusted gender wage gap of 18.3% in 2020 in Germany (Eurostat Citation2022). This difference can be explained by the focus on full-time employment and the private sector, as gender wage gaps in Germany are higher for full-time employees and higher in the private sector (Eurostat Citation2022). Next, I calculate an adjusted gender wage gap by adding individual-level control variables, i.e. work experience, tenure, and education. The adjusted gender wage gap is 15.3% (exp(−0.167)−1) and 23.1% smaller than the non-adjusted gapFootnote7 (Column 2 of ). This difference between the raw gender wage gap and the adjusted gender wage gap can be attributed to individual differences. Within occupations, the gender wage gap narrows slightly to 14.6% (exp(−0.158)−1), which is 4.6% smaller than the adjusted gender wage gap (Column 3 of ).

Table 1. Association between female relational power and the gender wage gap in firms and jobs.

Inside firms, the gender wage gap narrows to 10.2% (exp(−0.108)−1), which is 30.1% smaller than the adjusted gender wage gap in within occupations (Column 4 of ). Segregation into different paying firms can explain the difference between these two gaps. Since women, on average, sort into lower-paid firms than men, wage differences are higher in the labour market than inside firms. My results are evidence for hypothesis 1a that women work on average in lower-paid firms than men. This segregation might be the result of opportunity hoarding.

Within jobs the gender wage gap narrows to 8.7% (exp(−0.091)−1) (Column 5 of ). This gap is 14.7% smaller than the gap within firms. Since the gender wage gap is lower in jobs than in firms, my results hint toward segregation at the job level, i.e. women working in lower-paying jobs than men in the same firm. This segregation inside firms is further indication for opportunity hoarding and hypothesis 1b that women work on average in lower-paid jobs than men. In summary, the gender wage gap considerably narrows when looking inside firms or jobs, as the gap in jobs is 56.3% smaller than the raw gap. My results show segregation at the firm and job level, indicating the presence of opportunity hoarding.

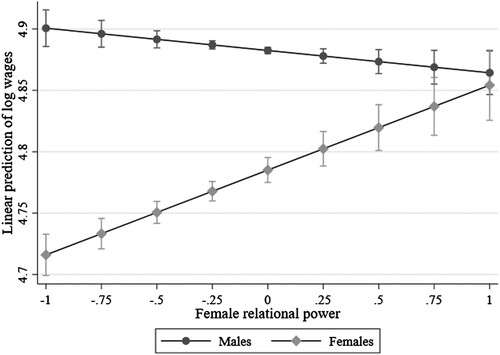

Although segregation into different firms and jobs explains a substantial share of the gender wage gap, notable wage differences between men and women remain, even at the job level. The second mechanism, exploitation through relational power, might explain these remaining differences. Columns 1 and 2 of show that higher female relational power is associated with females’ wage increases. The coefficient is very similar in size inside firms (Column 1) and inside jobs (Column 2). This result is evidence for hypothesis 2a and the exploitation mechanism since female relational power is associated with females’ wages even in the same jobs. For males, Columns 1 and 2 of show a negative association between higher female bargaining power and males’ wages for both regression models. Notably, this association is only statistically significant at the 10% level. This result supports hypothesis 2b that increasing the relational power of females lowers males’ wages and indicates a redistribution of males’ wages to females at the firm and job level. shows the predicted marginal effects graphically at different points of female relational power, underlining that female relational power is associated with both an increase in females’ wages and a decrease in males’ wages.Footnote8

Figure 1. Predicted marginal effects of relational power on males’ wages and females’ wages. Notes: The marginal effects are predicted using Stata’s marginsplot command based on the results from column (4) of Table 1. The depicted confidence interval is the 10% confidence interval.

Table 2. Marginal effects of relational power on males’ wages and females’ wages.

Redistribution by qualification level

reports exploitation by qualification level. Columns (1) and (2) show that for lower-qualified workers, female relational power is associated with higher wages for female workers (Columns 1 and 2 of ). For higher-qualified workers, I find a positive association between female relational power and females’ wages (Columns 3 and 4 of ). The coefficient of relational power is around 40% lower for higher-qualified females than the coefficient for lower-qualified females and the difference between these two coefficients is statistically significant for within-firm and within-job estimations (Appendix Table A6). Thus, I find evidence for hypothesis 2c that female relational power affects females’ wages stronger for lower-qualified than for higher-qualified females.

Table 3. Marginal effects of relational power on males’ and females’ wages by educational level.

For lower qualified male workers, I find a negative association between males’ wages and female relational power (Columns 3 and 4, ). Notably, this association is statistically significant at the 0.1% level at the firm level and 5% at the job level. Highly qualified males’ wages are not associated with female relational power and the difference between the coefficients for lower-qualified and higher-qualified males is statistically significant for the within-job estimations but not for the within-firm estimations (Appendix Table A6). Thus, I find partial evidence for hypothesis 2d that female relational power affects lower-qualified males’ wages stronger than wages of higher-qualified males. In summary, I find a stronger effect of female relational power on lower-qualified male and female workers. Furthermore, the positive coefficients for lower qualified and higher qualified female workers and negative coefficients for lower qualified male workers indicate a wage redistribution from lower qualified male workers to all female workers within firms.

Sensitivity analyses

To ensure the robustness of my results, I employ three sensitivity analyses. First, I aggregate first and second management level to measure female relational power. I find a particularly strong association between female relational power according to representation in the second management level and females’ wages (Appendix Table A7). The negative association between female relational power and males’ wages is limited to female representation in the second management level. These findings are in line with previous literature in Germany (Zimmermann Citation2022) and highlight the importance of female supervisors for narrowing gender wage inequalities.

Second, gender wage inequalities in Germany vary by industry sector (Hinz and Gartner Citation2005). Following the literature (Zimmermann Citation2022), I estimate fully interacted models including the industry sector as control variables to ensure the robustness of my results. The fully interacted regression yields similar results to the main regression (Appendix Figure A3; Appendix Table A8, column 1). Third, I categorize jobs at the 3-digit level. A more fine-grained occupational categorization might be beneficial when comparing workers within the same occupation. Using 4-digit occupational codes, I can distinguish between 540 occupations instead of 140 occupations when using 3-digit occupational codes. Categorizing jobs according to the very detailed 4-digit occupational codes yields similar results as 3-digit occupational codes (Appendix Figure A3; Appendix Table A8, column 2). Thus, the measurement of occupations does not affect my results.

Discussion and conclusion

Using the RIT framework, this study analyzes the importance of firms for gender wage inequalities and how the mechanisms opportunity hoarding and exploitation can explain gender wage gaps in firms. I employ unique longitudinal linked employer-employee data from Germany consisting of administrative data linked to rich survey data. I analyze the mechanisms of opportunity hoarding and exploitation.

First, opportunity hoarding postulates that males might prefer other males for highly paid jobs or firms, preventing females from entering well-paid firms or jobs. This segregation contributes to gender wage inequalities. This opportunity hoarding can happen at different levels, such as the firm level (Tomaskovic-Devey and Avent-Holt Citation2019). I find that the gender wage gap is much lower in firms than in the labour market, which might be the result of opportunity hoarding at the firm level. This difference between the labour market and firms is evidence for hypothesis 1a, which states that the gender wage gap is lower in firms than in the labour market in total. By analyzing differences between gender inequalities in wages at the firm and job level, I investigate opportunity hoarding at the job level (hypothesis 1b). My results show a 14.6% lower gender wage gap in firms than in the labour market. This difference could be the result of opportunity hoarding at the job level. Thus, my findings indicate opportunity hoarding at the firm and job levels, which is in line with previous scholarship (e.g. Penner et al. Citation2023).

Second, exploitation assumes that gender wage inequalities originate in males redistributing females’ wages to males using their relational power. My results show that increasing females’ relational power, for example, by increasing the presence of female managers, is associated with lower gender wage gaps. These findings are evidence for hypothesis 2a, stating that an increase in female managers leads to higher females’ wages. I show that this result can be found at the firm and job levels. My first contribution to the RIT literature is investigating exploitation net of opportunity hoarding at the job level. While some previous research finds no effects of the presence of female managers on females’ wages (e.g. Van Hek and Van Der Lippe Citation2019), most previous studies find that the presence of female managers in firms increases females’ wages (e.g. Cohen and Huffman Citation2007; Zimmermann Citation2022).

Since organizational resources are scarce (Tomaskovic-Devey and Avent-Holt Citation2019), wage increases for females must be accompanied by wage decreases for other groups, according to RIT. I find evidence for hypothesis 2b that at the firm and job level, an increase in female managers is accompanied by wage losses for male workers, albeit the wage losses for male workers are only statistically significant at the 10% level. The scarce previous longitudinal research on female managers and gender wage inequalities also finds a negative effect of female managers’ presence on males’ wages in Sweden (Hensvik Citation2014) and Germany (Zimmermann Citation2022). However, these studies do not investigate or discuss this finding in detail. My second contribution to the literature is investigating this redistribution within firms in detail and analyzing which groups’ wages are redistributed.

Although the wage redistribution to women can theoretically come from multiple sources, lower qualified workers should especially be affected by the redistribution due to their lower bargaining power. My results indicate mainly a redistribution from lower-qualified male workers to lower-qualified female workers within firms and jobs. The wages of higher-qualified male workers and female workers were not affected as strongly as the wages of lower-qualified male and female workers by female relational power, supporting hypothesis 2c and 2d. Notably, highly qualified males’ wages were not affected by female relational power.

My results on redistribution are in line with research, as previous evidence mainly points towards a redistribution from workers with less relational power to workers with more relational power (Tomaskovic-Devey and Avent-Holt Citation2019). For example, Sakamoto and Kim (Citation2010) find that male and credentialed workers earn wages above their estimated productivity contributions while female and uncredentialed workers’ wages are below their productivity contributions. Schweiker and Groß (Citation2017) show that decreases in bonus payments for the lower half of the wage distribution accompany increases in bonus payments for the upper half of the wage distribution in Germany. I only find statistically significant negative wage effects for lower-qualified males, which is in line with wage decreases for workers from the bottom of the wage distribution.

My study highlights an often overlooked finding of increasing the number of female managers. While females’ wages, in general, benefit from the presence of female managers, within-firm wages of lower-qualified males decrease. Thus, within-firm inequality between males and females narrows but inequality between lower-qualified and higher-qualified males increases. This finding is concerning as wage inequalities, in general, have been increasing (Schweiker and Groß Citation2017; Tomaskovic-Devey and Avent-Holt Citation2019), and the presence of female managers might contribute to this trend as a side effect by increasing wage inequality among males. Policymakers could try to increase the relational power of lower-qualified workers to counteract this inequality increase in males’ wages, for example, by increasing the prevalence of collective agreements.

There are also some limitations to my study. First, I measure redistributions between groups at the firm and job level. Since I cannot observe firm changes from individuals, I cannot include worker fixed effects. Thus, I cannot make statements about effects on individual wages. Hensvik (Citation2014) finds a negative effect of female managers on males’ wages using worker-fixed effects, indicating wage losses for individual male workers. Second, I cannot exclude other sources of potential wage gains for women, such as revenue increases in a firm which could get mostly allocated to females’ wages. Third, emerging literature shows that fixed effects regressions with interaction effects might be biased due to using within and between variance for the interaction effects (Giesselmann and Schmidt-Catran Citation2022). Since my panel is only four periods long, I cannot use estimators relying solely on within variance. An avenue for future research would be using panel data covering more periods of time to consider this limitation.

Fourth, I exclude part-time workers as the data lacks information about exact working hours. While less than 5% of men work part-time in my sample, approximately a third of women are part-time workers. Thus, considering part-time employment is essential for gender inequalities. As cross-sectional research for Germany including part-time employment also finds an association between the presence of female managers and higher wages for female employees (Abendroth et al. Citation2017), I assume that patterns might be similar when including part-time workers.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Matthias Collischon, Christoph Müller, and Dana Müller for their valuable feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The Research Data Centre of the Federal Employment Agency at the IAB (https://fdz.iab.de/en.aspx) provides the LIAB QM2 9319. See Zimmermann (Citation2023) for the replication package.

Notes

1 The terms firms and organizations refer to firms. For multi-site firms, firms and organizations refer to local establishments.

2 In related scholarship, workplace demography has long highlighted how the relative sex composition inside organizations affects inequality between groups (e.g. DiTomaso et al. Citation2007).

3 The Research Data Centre of the Federal Employment Agency at the IAB (https://fdz.iab.de/en.aspx) provides the LIAB QM2 9319. See Zimmermann (Citation2023) for the replication package.

4 Next to opportunity hoarding, an in-group bias, another form of social closure is exclusion, an out-group bias. In the exclusion mechanism, in-group members explicitly exclude out-group members from opportunities (Tomaskovic-Devey and Avent-Holt Citation2019). This form of exclusion is less prevalent since the introduction of equal opportunity laws.

5 Information about the management’s composition is also available in 2004 and 2008. Due to different time gaps between surveying the data, i.e. four years instead of two years, and a change to a more fine-grained occupational code in 2011, I focus on the years 2012, 2014, 2016, and 2018.

6 Full-time equivalent shares are calculated by weighing full-time workers as 1 and part-time workers as 0.5 since information about working hours is not available.

7 The relative differences between gender wage gaps is calculated in the following way:

100% − (15.3% / 19.9%) = 23.1%.

8 Estimations using dummies at different percentiles of female relational power’s distribution also show that increasing female relational power is accompanied by decreasing wages for males and increasing wages for females (Appendix Figure A2). A notable difference is that the confidence intervals do not overlap anymore for firms with high female relational power (Appendix Table A4).

References

- Abendroth, A.-K., Melzer, S., Kalev, A. and Tomaskovic-Devey, D. (2017) ‘Women at work’, ILR Review 70(1): 190–222. doi:10.1177/0019793916668530.

- Acker, J. (2006) ‘Inequality regimes’, Gender & Society 20(4): 441–64. doi:10.1177/0891243206289499.

- Avent-Holt, D., Henriksen, L. F., Hägglund, A. E., Jung, J., Kodama, N., Melzer, S. M., Mun, E., Rainey, A. and Tomaskovic-Devey, D. (2020) ‘Occupations, workplaces or jobs?: an exploration of stratification contexts using administrative data’, Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 70: 100456. doi:10.1016/j.rssm.2019.100456.

- Avent-Holt, D. and Tomaskovic-Devey, D. (2010) ‘The relational basis of inequality’, Work and Occupations 37(2): 162–93. doi:10.1177/0730888410365838.

- Avent-Holt, D. and Tomaskovic-Devey, D. (2012) ‘Relational inequality: gender earnings inequality in U.S. and Japanese manufacturing plants in the early 1980s’, Social Forces 91(1): 157–80. doi:10.1093/sf/sos068.

- Baron, J. N. and Bielby, W. T. (1980) ‘Bringing the firms back in: stratification, segmentation, and the organization of work’, American Sociological Review 45(5): 737. doi:10.2307/2094893.

- Blau, F. D. and Kahn, L. M. (2017) ‘The gender wage gap: extent, trends, and explanations’, Journal of Economic Literature 55(3): 789–865.

- Card, D., Cardoso, A. R. and Kline, P. (2016) ‘Bargaining, sorting, and the gender wage gap: quantifying the impact of firms on the relative pay of women *’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 131(2): 633–86. doi:10.1093/qje/qjv038.

- Cohen, P. N. and Huffman, M. L. (2007) ‘Working for the woman? female managers and the gender wage gap’, American Sociological Review 72(5): 681–704. doi:10.1177/000312240707200502.

- DiPrete, T. A. and McManus, P. A. (1996) ‘Institutions, technical change, and diverging life chances: earnings mobility in the United States and Germany’, American Journal of Sociology 102(1): 34–79. doi:10.1086/230908.

- DiTomaso, N., Post, C. and Parks-Yancy, R. (2007) ‘Workforce diversity and inequality: power, status, and numbers’, Annual Review of Sociology 33(1): 473–501. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131805.

- England, P. (2010) ‘The gender revolution’, Gender & Society 24(2): 149–66. doi:10.1177/0891243210361475.

- England, P., Levine, A. and Mishel, E. (2020) ‘Progress toward gender equality in the United States has slowed or stalled’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117(13): 6990–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.1918891117.

- Eurostat (2022) Gender pay gap statistics. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Gender_pay_gap_statistics [Accessed 13 Sep 2022].

- Giesselmann, M. and Schmidt-Catran, A. W. (2022) ‘Interactions in fixed effects regression models’, Sociological Methods & Research 51(3): 1100–27.

- Grönlund, A. and Magnusson, C. (2016) ‘Family-friendly policies and women’s wages – is there a trade-off? Skill Investments, occupational segregation and the gender pay gap in Germany, Sweden and the UK’, European Societies 18(1): 91–113. doi:10.1080/14616696.2015.1124904.

- Hensvik, L. E. (2014) ‘Manager impartiality: worker-firm matching and the gender wage gap’, ILR Review 67(2): 395–421. doi:10.1177/001979391406700205.

- Hinz, T. and Gartner, H. (2005) ‘Geschlechtsspezifische Lohnunterschiede in Branchen, berufen und betrieben / the gender wage gap within economic sectors, occupations, and firms’, Zeitschrift Für Soziologie 34(1): 22–39. doi:10.1515/zfsoz-2005-0102.

- Imbens, G. W. and Wooldridge, J. M. (2009) ‘Recent developments in the econometrics of program evaluation’, Journal of Economic Literature 47(1): 5–86.

- Liu, J., Sakamoto, A. and Su, K.-H. (2010) ‘Exploitation in contemporary capitalism: an empirical analysis of the case of Taiwan’, Sociological Focus 43(3): 259–81. doi:10.1080/00380237.2010.10571379.

- Lundberg, I., Johnson, R. and Stewart, B. M. (2021) ‘What is your estimand? Defining the target quantity connects statistical evidence to theory’, American Sociological Review 86(3): 532–65.

- Marx, K. (1867) Capital, Volume I.

- Melzer, S. M., Tomaskovic-Devey, D., Schunck, R. and Jacobebbinghaus, P. (2018) ‘A relational inequality approach to first- and second-generation immigrant earnings in German workplaces’, Social Forces 97(1): 91–128. doi:10.1093/sf/soy021.

- Penner, A.M., Petersen, T., Hermansen, A.S., Rainey, A., Boza, I., Elvira, M.M., Godechot, O., Hällsten, M., Henriksen, L. F., Hou, F., Mrčela, A. K., King, J., Kodama, N., Kristal, T., Křížková, A., Lippényi, Z., Melzer, S. M., Mun, E., Apascaritei, P., Avent-Holt, D., Bandelj, N., Hajdu, G., Jung, J., Poje, A., Sabanci, H., Safi, M., Soener, M., Tomaskovic-Devey, D. and Tufail, Z. (2023) ‘Within-job gender pay inequality in 15 countries’, Nature Human Behaviour 7(2): 184–9.

- Peters, E. and Melzer, S. M. (2022) ‘Immigrant–native wage gaps at work: how the public and private sectors shape relational inequality processes’, Work and Occupations 49(1): 79–129. doi:10.1177/07308884211060765.

- Rabe-Hesketh, S. and Skrondal, A. (2012) Multilevel and Longitudinal Modeling using Stata, College Station: Stata Press.

- Reskin, B. F. (1988) ‘Bringing the men back in: sex differentiation and the devaluation of women's work’, Gender & Society 2(1): 58–81.

- Ridgeway, C. L. (1997) ‘Interaction and the conservation of gender inequality: considering employment’, American Sociological Review 62(2): 218–35.

- Ridgeway, C. L. (2014) 'Why status matters for inequality', American Sociological Review 79(1): 1–16.

- Ruf, K., Schmidtlein, Lisa, Seth, Stefan, Stüber, Heiko and Umkehrer, Matthias (2021a) ‘Linked Employer-Employee Data from the IAB: LIAB Cross-Sectional Model 2 (LIAB QM2) 1993–2019’, FDZ Datenreport 3(2021).

- Ruf, K., Schmidtlein, Lisa, Seth, Stefan, Stüber, Heiko, Umkehrer, Matthias, Graf, Tobias, Grießemer, Stefan, Kaimer, Steffen, Köhler, Markus, Lehnert, Claudia, Oertel, Martina and Schneider, Andreas (2021b) Linked-Employer-Employee-Data of the IAB (LIAB): LIAB Cross-Sectional Model 2 1993–2019, Version 1 [Data set]. Research Data Centre of the Federal Employment Agency (BA) at the Institute for Employment Research (IAB). doi:10.5164/IAB.LIABQM29319.de.en.v1.

- Sakamoto, A. and Kim, C. (2010) ‘Is rising earnings inequality associated with increased exploitation? Evidence for U.S. Manufacturing Industries, 1971–1996’, Sociological Perspectives 53(1): 19–43. doi:10.1525/sop.2010.53.1.19.

- Schweiker, M. and Groß, M. (2017) ‘Organizational environments and bonus payments: rent destruction or rent sharing?’, Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 47: 7–19. doi:10.1016/j.rssm.2016.04.005.

- Speer, J. D. (2016) ‘How bad is occupational coding error? A task-based approach’, Economics Letters 141: 166–8. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2016.02.025.

- Stüber, H., Dauth, W. and Eppelsheimer, J. (2023) ‘A guide to preparing the sample of integrated labour market biographies (SIAB, version 7519 v1) for scientific analysis’, Journal for Labour Market Research 57(1): 1–11.

- Tilly, C. (1998) Durable Inequality, Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Tomaskovic-Devey, D. (1993) ‘Gender and racial inequality at work’. doi:10.7591/9781501717505.

- Tomaskovic-Devey, D. and Avent-Holt, D. (2019) Relational Inequality: An Organizational Approach, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Umkehrer, M. (2017) ‘Combining the waves of the IAB Establishment Panel. A do-file for the basic data preparation of a panel data set in Stata’, FDZ-Methodenreport 12: 2017.

- Valet, P., Adriaans, J. and Liebig, S. (2019) ‘Comparing survey data and Administrative Records on gross earnings: nonreporting, misreporting, interviewer presence and earnings inequality’, Quality & Quantity 53(1): 471–91. doi:10.1007/s11135-018-0764-z.

- Van Der Lippe, T, Van Breeschoten, L and Van Hek, M (2019) 'Organizational work–life policies and the gender wage gap in European workplaces', Work and Occupations 46(2): 111–148.

- Van Hek, M. and Van Der Lippe, T. (2019) ‘Are female managers agents of change or cogs in the machine? an assessment with three-level manager–employee linked data’, European Sociological Review 35(3): 316–31. doi:10.1093/esr/jcz008.

- Weber, M. (1947 [1924]) The Theory of Social and Economic Organization, trans T. Parsons, New York: Free Press.

- Wooldridge, J. M. (2010) Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data, Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Zimmermann, F. (2022) ‘Managing the gender wage gap—how female managers influence the gender wage gap among workers’, European Sociological Review 38(3): 355–70. doi:10.1093/esr/jcab046.

- Zimmermann, F. (2023) Narrowing inequalities through redistribution. Available from: osf.io/fzpjk.

- Zimmermann, F. and Collischon, M. (2023) ‘Do organizational policies narrow gender inequality? Novel evidence from longitudinal employer–employee data’, Sociological Science 10: 47–81.