ABSTRACT

The 2014 Russian invasion of Ukraine resulted, among other things, in a dramatic increase in Ukrainian emigration to Europe, particularly to Poland. The article evaluates its consequences, by confronting trajectories of pre- and post- 2014 war male and female Ukrainian migrants to Poland. The comparisons combine mobility and migrants’ labor market paths linked to employment sectors. On data from surveys conducted in two Polish cities – Warsaw and Wrocław – in 2018-2019, we performed sequence analysis revealing seven clusters of trajectories, serving as a dependent variable in the multinomial regression analysis. We found that the war context contributed to the growth of permanency in Ukrainian migration, challenging a temporary mobility model observed in Ukraine-to-Poland migration for over two decades, which involves demographic consequences for Ukrainian society. In Poland, post-2014 war migrants are more likely than earlier cohorts to work in the new migrant niches, but contribute also to the revitalization of old ones. All of this contributes to structural changes in the Polish labor market. Importantly, we did not find evidence for a refugee penalty in economic integration, which we link to the mix of economic and humanitarian drivers of post-war Ukrainian migration to Poland.

1. Introduction

The 2014 Russian invasion of Ukraine had an impact on various spheres of Ukrainian society. The humanitarian crisis in the Eastern part of Ukraine and the subsequent economic crisis resulted not only in internal displacement of a number of Ukrainian citizens (Drbohlav and Jaroszewicz Citation2016), but also changed the context of migration from Ukraine to Europe. Starting from the early 1990s, Ukrainian migration to various European countries, especially Central Europe, was quite intensive. However, it was characterized by a prevalence of short-term circular mobility of Ukrainian citizens earning their living in Ukraine (Fedyuk and Kindler Citation2016). Such a pattern was surprisingly persistent notwithstanding political changes on the European continent such as the expansion of the European Union and the Schengen area to the east. Against this background, the 2014 Russian invasion apparently constituted a game changer for Ukraine-to-Europe migration resulting in its dramatic increase, particularly to neighboring Poland (Lücke and Saha Citation2019, Górny and Kaczmarczyk Citation2020) which became the European leader in the number of first residence permits issued in 2016.Footnote1

The article aims at evaluating dynamics in temporal patterns and labor market participation of Ukrainian migrants to Poland in the context of the 2014 Russian invasion of Ukraine. The invasion implies the occurrence of humanitarian drivers in Ukraine-to-Poland migration and is considered an important factor of its substantial increase after 2013 (Górny and Kaczmarczyk Citation2020). In this way, it addresses consequences of the Russian invasion for both Ukraine and Poland. Emigration involves demographic and economic challenges for an ageing Ukrainian society. The influx of millions of Ukrainian migrants to Poland over a short-time span, following the 2014 war, constitutes both an opportunity for the Polish economy suffering shortages in the labor market and challenges regarding the social integration of numerous migrants. These latter challenges have been further intensified by the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, resulting in massive humanitarian movements towards Europe, and again mainly towards Poland. The post-2014 Ukraine-to-Poland migration context analyzed in this paper constitutes an important reference point for current processes we observe in Poland and other European countries during the war in Ukraine.

The research question we attend to here is: to what extent do pre-2014 war and post-war Ukrainian male and female migrants to Poland differ with regard to mobility patterns – with the focus on their permanence and temporariness – and labor market trajectories? We focus on the sectors of migrants’ employment in Poland. The analyzed group of post-war migrants can be treated as a fluid category of humanitarian migrants, including not only legally recognized refugees whose mean share among applicants for international protection in Europe, approached only 10%, not exceeding 2% in selected countries, in 2000–2014 (Dustmann et al. Citation2017). As in some earlier studies on economic integration of forced migrants (Cortes Citation2004, Anders et al. Citation2018, Şimşek Citation2020, Salikutluk and Menke Citation2021), we refer to the selected wave of migrants from the given country of origin corresponding to increased humanitarian outflows from this country.

Studies comparing humanitarian and economic migrants are still not numerous and relate to diverse contexts. However, their common message points to the observable differences between outcomes of economic integration in the case of these two groups (Connor Citation2010, Bakker et al. Citation2017, Dustmann et al. Citation2017). Regarding the Poland-Ukraine case, we suppose that the occurrence of humanitarian push factors in Ukraine challenged the model of circular mobility, making migrants more prone to come to Poland for longer stays and settlement, as is the case for involuntary migrants without prospects for positive changes in the home country (Zakirova and Buzurukov Citation2021). Consequently, we expect that migrants’ labor market trajectories have changed as well because permanent and long-term migrants are more prone than temporary migrants to strive for social advancement on the labor market and avoid or escape migrant niches (Barbiano di Belgiojoso Citation2019). Moreover, the Polish labor market has had to accommodate a sudden increase in supply of a labor force from abroad, which was conducive towards an opening of new sectors for foreign employment (Friberg and Midtbøen Citation2019). In our analyses, we attend to differences between males and females, acknowledging gendered patterns of migration and economic integration observed in other contexts (Rendall et al. Citation2010, Fleischmann and Höhne Citation2013, Kleinepier et al. Citation2015).

We focus on migration to urban areas predominating in Ukrainian inflow to Poland (Górny and Śleszyński Citation2019), cities Warsaw and Wrocław, and on the period before the COVID-19 pandemic (survey data collected in 2018-2019). We employed sequence analysis to identify the main types of mobility and labor market trajectories of Ukrainian migrants during the first three years of migration. Subsequently, we estimated a multinomial regression to examine factors influencing the probability that migrants fall into the given types of trajectories, with the focus on differences between pre-war and post-war migrants, both male and female.

2. Economic integration of involuntary and voluntary migrants

Two classical theoretical approaches to economic integration of migrants are assimilation theory (Chiswick Citation1978) and segmented assimilation (Piore Michael Citation1979). The first posits a U-shape pattern of occupational mobility of migrants in the destination country during their stay, after initial downgrading. According to the second perspective economic integration of migrants is largely confined to the secondary segment of the receiving labor market involving low-paid and low-skilled niches occupied by migrants – defined by an occupation and sector of employment (e.g. Midtbøen and Nadim, Citation2019). Generally, the stronger the secondary segment of the labor market, the higher the chances for segmented economic assimilation among migrants (Stanek and Ramos Citation2013). Formation of migrant niches is related to a combination of structural factors. One of them, linked to the supply side of the labor market, takes place when high numbers of migrants arrive in the destination country in a relatively short time-span (Friberg and Midtbøen Citation2019). As newcomers, they tend to locate on the lower strata of the labor market, with the operation of migrant social capital resulting in their concentration in given sectors.

The crucial factor behind economic integration, advancement of migrants and escape from migrant niches is the accumulation of the destination country specific capital, with the pivotal role of accumulation of human capital alongside the acquisition of the language of the receiving society (Chiswick Citation1978, De Vroome and Van Tubergen Citation2010, Sańchez-Domińguez and Fahleń Citation2018). The propensity of migrants to accumulate such capital is, in turn, linked to the time-horizon of their stay in the given country (Cortes Citation2004, Adda et al. Citation2021). Consequently, permanent migrants are more likely than temporary migrants to make investments in this regard. Moreover, if we treat temporary migrants as target earners only, their interest in social advancement on the occupational ladder of the destination country is limited (Barbiano di Belgiojoso Citation2019). Accordingly, temporary migrants are more likely than permanent migrants to locate in migrant niches of the labor market (Sánchez-Soto and Singelmann Citation2017). As regards humanitarian migrants, several authors (Cortes Citation2004, Bakker et al. Citation2017) argue that their time-horizon in the destination country is relatively long given the lack of opportunities to return home in a short-term perspective. However, Dustmann et al. (Citation2017) turn their attention to the uncertainty such migrants face in this respect due to the temporariness of legal protection rules and the unpredictability of the situation in their home countries.

The most frequently studied indicators of humanitarian migrants’ economic integration include employment status – usually limited to division between working and not-working statuses – or earnings (Cortes Citation2004, Potocky-Tripodi Citation2004, Connor Citation2010, Bevelander and Pendakur Citation2014, Bakker et al. Citation2017, Ruiz and Vargas-Silva Citation2018, Brell et al. Citation2020). Studies addressing other important indicators of economic integration, such as legal status of work (Ortensi and Ambrosetti Citation2021) and occupational status intersecting with location in migrant niches (Akresh Citation2008, Connor Citation2010, De Vroome and Van Tubergen Citation2010, Anders et al. Citation2018) are much less frequent. At the same time, previous studies indicate that employment in migrant niches involves a wage penalty (Catanzarite and Aguilera Citation2002). Therefore, migrants’ labor market trajectories relating to sectors of employment deserve attention in the context of their economic integration.

A common message stemming from the results of studies using various indicators of economic integration of involuntary migrants points to their inferior position on the labor market of the destination countries at the initial phase of migration when compared to other migrants (e.g. Cortes, Citation2004, Ruiz and Vargas-Silva, Citation2018). Newly arrived humanitarian migrants tend to concentrate in the lowest strata of not only the general labor market but also of migrant niches (Colic-Peisker and Tilbury Citation2006). This strong ‘immigration entry effect’ (Bakker et al. Citation2017) is interpreted in relation to circumstances of involuntary migration such as lack of a pre-migration preparatory phase and limited opportunities for choosing a destination country that would be optimal for the migrants’ skills (Dustmann et al. Citation2017). Consequently, the relatively low level of human capital of the arriving humanitarian migrants (especially language skills) and its limited transferability are considered as the main factors restraining the economic integration of involuntary migrants at the start (De Vroome and Van Tubergen Citation2010, Lumley-Sapanski Citation2021).

Concerning the economic integration of humanitarian migrants, most studies demonstrate a relatively fast catching-up process during the first years of migration (Connor Citation2010, Dustmann et al. Citation2017), which is, however, usually slower for females (Liebig and Tronstad Citation2018, Perales et al. Citation2021). This positive outcome has been explained by the eagerness of involuntary migrants to invest in the destination country specific human capital due to the relatively long time horizon they have in the destination country given the humanitarian situation in their home countries (Cortes Citation2004, Bakker et al. Citation2017). However, taking a long-term perspective, results are less consistent (Bratsberg et al. Citation2014). Still, several studies provide evidence for a ‘recovery hypothesis’ over a span of several years (Bakker et al. Citation2017, Dustmann et al. Citation2017). Differential results partly stem from variations in legal procedures and integration programs in the destination countries (Dustmann et al. Citation2017). Their positive role in the economic integration of humanitarian migrants has been evidenced by studies conducted in different countries (De Vroome and Van Tubergen Citation2010, Bevelander and Pendakur Citation2014, Lumley-Sapanski Citation2021).

Previous studies have, almost unanimously, pointed to the salience of differing selection patterns related to drivers of migration in shaping economic integration of various categories of migrants (Bratsberg et al. Citation2014, Dustmann et al. Citation2017). In the case of involuntary migrants, ethnic and national backgrounds, as well as comparatively low levels of social and human capital and its transferability, are most frequently addressed (Cortes Citation2004, Connor Citation2010, Anders et al. Citation2018, Van Tubergen Citation2022). Other factors influencing economic integration of both voluntary and involuntary migrants include gender, age at arrival in the destination country and household composition (e.g. Andersson and Scott, Citation2005, Connor, Citation2010, Potocky-Tripodi, Citation2004). Importantly, previous studies point to the inferior position of female humanitarian migrants on the labor market of the destination countries (Liebig and Tronstad Citation2018, Perales et al. Citation2021, Salikutluk and Menke Citation2021, Stempel and Alemi Citation2021) and a gendered pattern of niching (Wright et al. Citation2010). Then, younger migrants have better chances for fast accumulation of the destination country’s human capital, which opens avenues for labor market success (Bratsberg et al. Citation2014, Brell et al. Citation2020). An individual-level factor addressed specifically in the case of involuntary migrants is the risk of psychological health problems posing barriers to professional activity in the destination country (De Vroome and Van Tubergen Citation2010, Bakker et al. Citation2017, Ruiz and Vargas-Silva Citation2018).

In this article, while comparing Ukrainian migrants arriving in Poland before and after the 2014 Russian invasion of Ukraine, we contribute to the still-limited research field on economic integration of humanitarian migrants addressed via labor market trajectories and in a broader comparative perspective with respect to other migrants. By focusing on one national group, we eliminate a crucial source of refugees’ selectivity, i.e. country of origin and related cultural factors (Waxman Citation2001). It is a powerful circumstance in analyses of labor market trajectories, as migrant niches tend to evolve along ethnic divisions (Colic-Peisker and Tilbury Citation2006). We thus expect social-ethnic ties to direct post-war newcomers to Ukrainian migrant niches present on the Polish labor market already before the 2014 war. However, we also suppose expansion and an occurrence of new migrant niches on the Polish labor market because of an increased inflow of post-war Ukrainian migrants. As a ‘catching up effect’, we expect post-war migrants to be more likely than pre-war ones to escape migrant niches. This emerges from our presumption of higher permanency for migration in the case of the post-war group due to the humanitarian drivers of migration conducive to migrants’ investments in Poland-specific human capital acquisition.

3. The Poland-Ukraine context

The contemporary migration of Ukrainians to Poland started with the political and economic transitions in Central and Eastern Europe in the late 1980s, with trips by petty traders, which later evolved into labor migration. Such trips were short-term, repetitive and numerous – a model of circular mobility – proceeding under the visa-free regime between Poland and countries of the former Soviet Union. Temporary migration remained the dominant form of Ukrainian inflows to Poland for over two decades, mainly due to the Polish migratory legal framework which was supportive of temporary mobility (Górny et al. Citation2010). Flexible regulations regarding short-term stays and work, yet restrictive rules regarding long-term employment and settlement, provided grounds for the temporary migration regime in Poland (Górny Citation2017b) which was challenged only by the COVID-19 pandemic regulations.

Since the late 1980s, the stock of migrants in Poland has grown only moderately, accounting for less than 1% of the Polish population at the beginning of the 2010s. This trend was smooth, despite the increase in demand on the Polish labor market after the intensive emigration of Poles following Poland's accession to the European Union (2004), the growth of the economy, and the ongoing liberalization of regulations on the work of foreigners (which began as early as 2007) (Górny Citation2017a, Górny and Kaczmarczyk Citation2020). Only the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2014 interrupted this trend, leading to a substantial increase in migration from Ukraine to Poland. Poland, as a neighboring country with very liberal employment regulations and strong demand for workers in selected sectors of the Polish labor market, became a magnet for Ukrainians fleeing the humanitarian and economic hardships of the war (Górny and Kaczmarczyk Citation2020) when Russia lost its relative importance as the destination area due to the war context (Lücke and Saha Citation2019).

The number of documents for work issued by the Polish state to Ukrainian migrants increased from less than 300,000 in 2013 to almost two million in 2017 and 2019 (Ministry of Family and Social Policy data). Consequently, the share of Ukrainians reached 70-90% in various categories of foreign workers in Poland. In the case of Ukrainians with residence permits, the respective increases went from less than 40,000 in 2013 to over 145,000 in 2017 and almost 215,000 in 2019 (Office for Foreigners data). The numbers of Ukrainians applying for a refugee status in Poland oscillated, however, with only around 2,300 in 2014-2015, and showed a diminishing trend in subsequent years. The military crisis in Ukraine resulted, thus, in a dynamic increase of economic, but not humanitarian, migration to Poland, if we consider the legal status of Ukrainians arriving in PolandFootnote2. Before the early 2010s, Ukrainian nationals in Poland worked mainly in agriculture, construction and domestic services (Brunarska et al. Citation2016). In later years, especially after 2013, a growing diversity of sectors for employment of these migrants has been observed, including trade, hospitality, industry and services (Górny and Kaczmarczyk Citation2020).

Overall, Ukrainian migration to Poland constitutes an intriguing case of complex interplays between economic and humanitarian drivers of migration challenging the sharp division between humanitarian and economic migrants, as observed also in other contexts (Donato and Ferris Citation2020, Ortensi and Ambrosetti Citation2021). Results of previous studies on refugees’ return migration additionally point to the salience of economic security in the home countries as its predictor (Klinthäll Citation2007, Zakirova and Buzurukov Citation2021). In this vein, humanitarian factors and the subsequent economic crisis in Ukraine changed the opportunity structures for Ukrainian temporary and return migration.

Ukrainian migrants have been drawn mainly to large Polish cities (Górny and Śleszyński Citation2019). Before 2014, they were additionally highly concentrated in selected areas, with the main role of the capital Warsaw and Mazovian region. In 2013, documents issued for work in this region accounted for over 55% of the total for Poland. Growing numbers of Ukrainian migrants were, however, exploring new Polish destinations, such as Wrocław, located in the Lesser Silesia region, and analyzed in this article as a second city after Warsaw. In 2019, Mazovian and the Lesser Silesia regionsFootnote3 held the first two places in terms of the largest numbers of documents issued to work in Poland, mainly to Ukrainians, with respective shares amounting to 24% and 10% of the total. However, while Warsaw can be considered as a ‘traditional’ destination area in Poland, whose role was already important in the 1990s, Wrocław is a new post-2014-war Polish destination for Ukrainian migrants. Inclusion of these two cities in our analyses allows for the capture of differential contexts in post-war Ukrainian migration.

4. Data and methods

4.1. Data

In this study we use data from two surveys on Ukrainian migrants in Poland, conducted in two major Polish cities hosting the largest numbers of Ukrainian migrants: Wrocław (N = 500) in 2018 (Górny et al. Citation2019) and Warsaw (N = 1319) in 2019 (Górny et al. Citation2020). The surveys were thus carried out in a short one-year interval when no major changes in migratory trends to Poland have been observed. Importantly, they employed an identical method of data collection and research tools: a PAPI mode of an interview conducted in the one dedicated research site in either the Ukrainian, Russian or Polish language depending on the choice of the respondent. The questionnaire collected retrospective information, in the form of a bi-weekly calendar, about each trip to Poland, and selected data relating to the stay in Poland, including labor market status, sector of employment and legal status (See the supplemental file for the questions).

Both analyzed surveys were conducted with the help of a respondent-driven sampling method (RDS), which is a modified version of chain-referral sampling with a double incentive system. Its advantages in research on so-called ‘hard-to-reach’ populations contributed to its growing popularity in migration studies (Tyldum and Johnston Citation2014). Respondents are rewarded both for taking part in the research (primary incentive) and for recruiting a peer (secondary incentive) (for an elaboration, see Heckathorn, Citation1997). The study starts by selecting a small number of diverse individuals (so-called ‘seeds’). They initiate the recruitment chains and, as subsequent recruiters, are allowed to recruit only a limited number of people (usually 2–3 people). In RDS, the recruitment can be considered a first-order Markov chain process. Consequently, frequency weights and unbiased estimators for the studied groups can be derived (Heckathorn Citation1997). However, our analyses were conducted on an unweighted analytical sample, therefore the presented frequency distributions should not be considered as representative for the locations studied, but as portraying characteristics of this sample. At the same time, previous methodological studies on RDS provide for reasonable reliability of the results of multivariate analyses conducted on unweighted data (Heckathorn Citation2007, Sperandei et al. Citation2021).

The research group, in both surveys, was adult (18 years or older) Ukrainian migrants who had arrived in Poland at least three months prior to the study for non-tourist purposes and excluding persons enrolled in full-time and evening studies in Poland at the time of the studyFootnote4. The analytical sample was limited to 651 respondents whose migration projects (time since first arrival in Poland) were at least 36 months long. This makes it possible to follow the development of migrants’ trajectories over a considerable period of time. Importantly, although we examine migrants who were residents of the studied cities and their environsFootnote5 at the time of the study, our focus is on an initial three-year period of their migration to Poland, which may have been related to other localizations, e.g. the countryside. The sample included 149 migrants from Wroclaw and 502 from Warsaw, 288 men and 363 women, for whom the year of first arrival in Poland ranges from 1990 to 2016.

4.2. Methods

We used sequence analysis to identify the main types of mobility and labor market trajectories of Ukrainian migrants, and multinomial regression analysis to examine factors influencing the probability that migrants fell into the given types of trajectories, with the focus on differences between pre-war and post-war migrants, male and female. First, we started with a sequence analysis, where sequences refer to ordered states, events or activities (Cornwell Citation2015). Sequence analysis is especially useful for descriptive research on longitudinal data and is often used for labor market trajectories (Halpin Citation2019). The sequences we have studied consist of the monthly place of stay (Poland or Ukraine) and sector of employment in Poland – which we focus on in our operationalization of migrants’ labor market trajectories. These are examined over the course of three years, starting in the month of the first arrival in Poland. There are thus (12*3 = ) 36 monthly activity states.

In each month, individuals can stay in either Ukraine or Poland and work in different sectors of the Polish labor market. We distinguish between seven sectors and nine states: (1) staying in Ukraine; staying in Poland, and work in: (2) agriculture, (3) industry, (4) construction, (5) domestic services, (6) hospitality & catering, (7) other services, trade and transport, (8) other sectors; and (9) not working. The choice of sectors was based on their high prevalence in the studied group, and with reference to earlier studies on Ukrainian migrants in Poland (Górny and Kaczmarczyk Citation2020). The first five sectors account for 71.3% of all initial states during the first month of migration to Poland. The category ‘other services, trade and transport’ (11.2% of all initial states) refers to jobs that are likely to be occupations classified in 4–5 ISCO (the International Standard Classification of Occupations) categories, i.e. middle positions on the skills ladder. In turn, ‘other sector’ (5.7%) encompasses rather ‘better’ sectors beyond migrant niches such as health, education, IT, technology, communication, finances and banking, and consulting and marketing, and refers to higher 1–3 ISCO categories. The share of migrants not working during their first month in Poland – i.e. in education, inactive or unemployed – equals 11.8%.

The first step in our sequence analysis was to explore the labor market patterns among Ukrainian migrants in Poland. Second, we applied Optimal Matching (OM) to measure the dissimilarity of our observations. Third, we used agglomerative hierarchical clustering, using the Traminer package in R (Gabadinho et al. Citation2011), to identify clusters in our data. A robustness check using partitioning around medoids (PAM) produced similar clusters and cluster quality (available on request). We decided about the number of clusters based on the dendrogram, distribution plots and the Average Silhouette Width (ASW; 0.46).

After identification of the clusters, we used multinomial logistic regression analysis with the clusters as the dependent variable. Next to gender, an independent variable of our main interest has two categories: first arrival in Poland after 2013 (post-war migrants) and earlier (pre-war migrants). We also take into account other migrants’ socio-demographic characteristics and the characteristics of their first stays in Poland, as starting points of their trajectories. These include age at the first arrival in Poland, a binary indicator of migrants’ relatively stable legal status during their first stays, and temporary or permanent residence permit. We also consider two measures of human capital: whether migrants studied during their first stay in Poland, as well as educational level at the time of the study coded into four categories – primary, lower or vocational education, secondary or post-secondary, and tertiary education. We furthermore control for Western Ukraine as a region of the migrants’ origin, and the city where they reside in Poland – Warsaw or Wrocław. Descriptive statistics for the analytical sample and excluded cases are presented in Table A1 and A2 in the supplementary material. A replication package including all the programming code can be found online (Górny and van der Zwan Citation2023).

5. Results

5.1. Sequence analysis

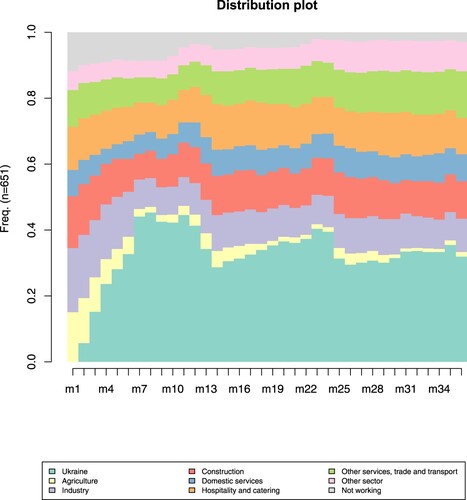

We start with a distribution plot of the different states. shows the general pattern of the whole set of sequences, that is aggregated views for each month, not individual sequences (Gabadinho et al. Citation2011). In the first months after arrival, we see heterogeneity across sectors. Over time, there are fewer and fewer respondents working in agriculture and industry, and also those not employed anywhere. We see quite stable shares of migrants that work in construction, while those in the rest of the sectors, especially in other services, trade and transport as well as in other sectors, mainly relating to ‘better’ jobs outside migrant niches, grow over time. The rate of respondents returning to Ukraine varies over time.

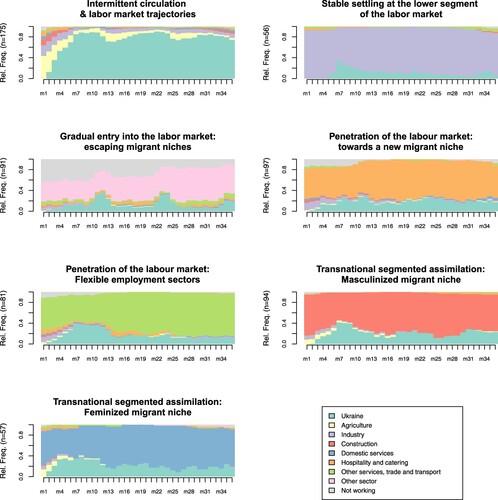

We identified seven clusters representing different types of mobility and labor market trajectories in Poland during the first three years of Ukrainians’ migration projects (). Descriptive statistics for each cluster can be found in Table A3 in the supplementary material. Each cluster is clearly linked to the given sector of employment. However, mobility patterns and related labor market trajectories differ between the clusters () providing for their specificities.

Table 1. Selected indicators of mobility and labor market trajectories in Poland by cluster.

shows that the biggest identified cluster (N = 175; 26.9% of the analytical sample) deserves the name ‘Intermittent circulation & labor market trajectories’. It is distinctive as regards mobility patterns because migrants belonging to it are characterized by a high mean share of time spent in Ukraine (74.8%), which implies an erratic pattern of circulation and high temporariness of stays in Poland (). The main initial sector of employment in Poland is agriculture, where 43.4% of migrants from this group were employed during their first stay in Poland. The incidence of non-working periods is observable, but not very high – only 5.7% of intermittent circulants had ever experienced this. Their mobility on the Polish labor market can be considered as rather small with the mean number of sectors of employment for three years, equaling 1.2. What distinguishes this cluster from other groups is that the incidence of employment in the sector most popular at the beginning of a migratory trajectory – agriculture – decreases visibly over the three-year observation period. However, we study migrants present in the city at the moment of the study, thus those who potentially had left agriculture at some point of their migration. Consequently, the obtained results might overestimate the outflow from agriculture, as we do not observe migrants who remained in the countryside. At the end of the three-year migration period, the share of migrants finally employed in agriculture reaches only 33.1% next to 20.6% of migrants working in industry. These two sectors, especially agriculture, can be considered as lower ends of the migrant labor market in Poland, as suggested by earlier research (Górny and Kaczmarczyk Citation2020).

Employment in the industry dominates the cluster ‘Stable settling at the lower segment of the labor market’ (N = 56; 8.6%) that encompasses migrants who, contrary to the previous cluster, spend most of their time in Poland (89.7%). For as many as 92.9% of migrants, industry was the main initial sector, but only 85.7% ended their three-year period of migration to Poland in this sector. At the same time, the incidence of non-working periods is one of the lowest alongside a small mean number of sectors of employment in Poland – 1.2. Therefore, the cluster represents migrants who are comparatively immobile regarding migration and the Polish labor market.

In the case of the remaining clusters, we observe a growing concentration of employment in the sectors that dominate migrants’ work trajectories. One of them, ‘Gradual entry into the labor market - escaping migrant niches’ (N = 91, 14.0%), refers to migrants spending most of their time in Poland (87.3% of the time). It can be considered as a contrasting example to the previously described two clusters, as it relates to the higher ends of the labor market. Namely, it consists of migrants among whom 36.3% started their working path in Poland in a sector other than typical migrant niches. This share increases if we consider the last job amounting to 63.7%. What distinguishes this cluster from others is a very high proportion of migrants who started their migration from a non-working period (45.1%), which usually involves studying in Poland (44.0% of migrants in this cluster). Moreover, the average share of such periods in the three-year periods of migration reaches as much as 33.3%. This is definitely a cluster of migrants who actively built their occupational paths in Poland, which involved investments in Poland-specific human capital, while studying in Poland.

As for the remaining four clusters, what they have in common is a comparable share of time spent by migrants in Poland during the first three years of their migration projects (78.5-82.9%). These four clusters form two pairs with observable similarities. The first pair bears the label ‘Penetration of the Polish labor market’, although its outcomes differ between the two clusters in question. The first of these deserves the sub-name ‘towards a new immigrant niche’ (hospitality & catering) (N = 97, 14.9%), while the second we call ‘flexible employment sectors’ (other services, trade and transport) (N = 81, 12.4%). What these two clusters have in common is a comparatively small proportion of migrants initially employed in the sector dominating the given cluster (around 60%). In the first cluster of the described pair, the share of migrants employed in hospitality & catering dominating this cluster, increased from 57.7% to 79.4% during the three-year observation period. This cluster stands out regarding the relatively high mean number of sectors migrants worked in – 1.6. It is also characterized by a relatively high proportion of migrants with non-working periods (18.6%), but the mean share of such periods is small – barely exceeding 5%. Overall, this cluster represents relatively diverse labor trajectories, but nonetheless demonstrates the pulling potential of the hospitality & catering sector as a new migrant niche.

In the case of the second cluster denoting responding of migrants to demand in flexible employment sectors, on the one hand, the pulling potential of the main sector-category is very high – 92.6% of migrants worked in ‘other services’ at the end of the three-year period. On the other hand, however, it must be borne in mind that the category of other services is broad and encompasses quite a variety of sub-sectors. It can be argued that, at the time of the study, they were only opening for foreign workforce, but none of them could have been considered a migrant niche, given the moderate concentration of migrants (Górny et al. Citation2019, Citation2020). Moreover, 12.3% of migrants in this cluster have ever experienced not-working in Poland.

The last two clusters are in line with earlier studies on economic integration of Ukrainian migrants in Poland (e.g. Brunarska et al. Citation2016) and relate to the old migrant niches. Both deserve to be labelled ‘Transnational segmented assimilation’ and differentiated into a ‘masculinized migrant niche’ (construction) (N = 94, 14.4%) and a ‘feminized migrant niche’ (domestic services) (N = 56, 8.6%). These clusters are unquestionably gender specific with shares of males and females exceeding 95% in respective groups (Table A3, supplementary material). They also stand out due to the highest shares (around 90%) of migrants ending up in the main sector of employment – construction and domestic services – after three years. Migrants in the feminized migrant niche cluster are slightly more mobile on the Polish labor market with regard to sectors of employment. Moreover, only 66.1% of them had started with domestic services compared to 78.7% in the construction sector. Additionally, 7.1% of migrants in the feminized migrant niche cluster had experienced non-working periods, while for the masculinized cluster it was only 2.1%.

5.2. Multinomial regression analysis

In the second step of the analyses, we test how being a pre-war and post-war migrant and other individual characteristics relate to the different clusters. We estimated two multinomial regression models with the clusters as the dependent variable, and present average marginal effects (AME). In the Model 1a (), we included all the individual characteristics and those related to the first trip to Poland except for indicators of migrants’ human capital. These indicators – the level of migrants’ education and a binary for studying in Poland during the first stay – were added in Model 1b (). In addition, we estimated two supplementary models (Table A4, supplementary material), in which variables measuring year of the first arrival in Poland were more precise than in the main models. These are: a variable designating two cohorts of pre-war migrants – those who started migrating before 2008 and in 2008–2013 – next to the post-war cohort (Model 1a, Table A4); and a quasi-continuous variable denoting the year of first arrival in Poland (Model 1b, Table A4). In this way we can discuss the differences between pre-war and post-war migrants against the development of the process of Ukrainian migration to PolandFootnote6.

Table 2. Multinomial regression analysis; presented are Average Marginal Effects (AME; N = 651).

In descriptions to follow, we focus on the final model (Model 1b, ), commenting on differences between models where appropriate. First, as expected, pre-war and post-war migrants differ significantly in probability of belonging to certain clusters. In particular, post-war migrants are by 24 percentage points (p.p.) less likely to pursue a trajectory of intermittent circulation during the first three years of migration to Poland than pre-war migrants. When compared to migrants arriving in Poland before 2008 (Model 1a, Table A4), the 2008-13 migrant cohort is by 13 p.p. less likely to follow this path, while for post-war migrants the respective decrease of likelihood has been visibly higher (37 p.p.). The cluster in question thus represents the pattern gradually declining in importance, which can be linked to the progress in migration from Ukraine to Poland rather slowly becoming more permanent (Górny Citation2017b). Each subsequent cohort of migrants is by 2 p.p. less likely to pursue such trajectory (Model 1b, Table A4). This process clearly intensified when the war context deteriorated return prospects in Ukraine after 2013.

Overall, post-war migrants are more likely than pre-war migrants to pursue trajectories related to more stable stays in Poland. Significant effects are found for two clusters linked to the newer migrant niches – stable settling at the lower segment (4 p.p.) and towards a new migrant niche (10 p.p.) – and to the ‘older’ masculinized migrant niche (7 p.p.) (Model 1b, ). For the trajectory of stable settling at the lower segment related to the industry sector, additional analysis (Model 1a, Table A4) reveals that post-war migrants are also more likely (6 p.p.) to follow this path than pre-2008 migrant cohort, while the differences between two older cohorts are insignificant. This suggests that the industry has gradually become more important in the lowest segment of the labor market with respect to foreign employment in Poland, but a significant change took place in the post-war period. The same tendency, with respect to pre-2008 and 2008-13 cohorts, has been observed for the cluster denoting flexible employment sectors (Model 1a, Table A4).

Regarding the cluster related to the new migrant niche in hospitality & catering, we can observe its already gradually growing role before the war (Model 1b, Table A4), which intensified in the post-war period. Migrants from the 2008-13 cohort are more likely than earlier migrants to belong to the cluster related to this niche by 7 p.p., while for the post-war migrants the respective effect amounts to 14 p.p. (Model 1a, Table A4). The corresponding tendencies related to the cluster involving the ‘older’ masculinized migrant niche are more complex. Interestingly, migrants from the 2008-13 cohort are less likely (by 8 p.p.) than earlier migrants to belong to this cluster, while the respective effect is insignificant for post-war migrants (Model 1a, Table A4). The increased inflow of post-war migrants resulted, thus, in a revival of the construction sector as an ‘old’ employment niche for foreign workers.

Importantly, only when we differentiate between older and newer pre-war cohorts (Model 1a, Table A4), we observe significant effects for the trajectory denoting escaping migrant niches. Migrants from the 2008-13 cohort and from the post-war cohort are, respectively, by 15 p.p. and 11 p.p. more likely to pursue this path than pre-2008 migrants. This trajectory had thus already grown in importance among the Ukrainians who had started migration to Poland shortly before the 2014 war and its outbreak did not influenced this tendency decisively. However, it is likely that some migrants became more inclined to remain in Poland and to invest in escaping migrant niches after the outbreak of the war, which happened after some time from the start of their migration to Poland.

As regards gender as a factor differentiating belonging to the given clusters, as expected, its impact is first of all visible in the case of the segmented assimilation pattern related to masculinized and feminized migrant niches. However, women are also more likely than men (by 10 p.p.) to pursue a trajectory of labor market penetration towards the new migrant niche – hospitality & catering. The four remaining clusters are equally probable in the case of both genders, according to the final model (Model 1b, ). However, according to the model not accounting for the accumulation and level of migrants’ human capital (Model 1a, ) women are more likely to pursue the trajectory escaping migrant niches. This points to the significance of the selection process with respect to human capital in shaping the capability of migrants to escape segmented assimilation (Bratsberg et al. Citation2014, Dustmann et al. Citation2017).

As demonstrated in most studies addressing integration of migrants (Fuller Citation2015), circumstances of the initial phase of migration – in our study those related to the time during the first stay in Poland – are crucial for shaping labor market trajectories in the destination country. The older migrants were at the start of the migration, the more likely they were to pursue segmented assimilation trajectories, whereas intermittent circulation and the trajectory related to hospitality & catering are more probable in the case of younger migrants. However, the age-related effects are rather small. Results on the legal status during the first stay in Poland show that migrants possessing either temporary or permanent residence permits are more likely to belong to the clusters unrelated to particular migrant niches, i.e. escaping migrant niches (11 p.p.) and flexible employment sectors (8 p.p.). This points to the fact that a stable legal status at the beginning of a migration project gives migrants better opportunities to locate outside migrant niches in the context of a temporary migration regime such as the Polish case. In addition, possessing a stable legal status at the start of migration differentiates migrants in the probability of belonging to clusters related to the most and the least intensive mobility between Ukraine and Poland: intermittent circulation (by 21 p.p. lower) and stable settling (by 4 p.p. higher), which agrees with intuition.

An important predictor, materializing as significant in the case of the six out of seven clusters is enrolment in studies in Poland during the first stay. This can be treated as a (partial) indicator of Poland-specific human capital accumulation (Dustmann et al. Citation2017). Importantly, it relates also to the selectivity of migrants, as only a certain group of migrants is capable of studying in the destination country – those with an adequate level of education and sufficient languages skills. Thus, it does not come as a surprise that enrolment for studies in Poland during the first stay increases the probability of belonging to the escaping migrant niches trajectory by 20 p.p., which is the biggest effect from among clusters. It is also a significant predictor for the two clusters denoting the penetration of the Polish labor market (hospitality & catering and other services sectors), and interestingly, for segmented assimilation in domestic services. These sectors can provide part-time jobs for students, which would explain their popularity among migrants who had studied in Poland at some point. On the opposite end, enrolment in studies in Poland decreases the probability of intermittent circulation and stable settling at the lower segment (industry) – the two trajectories related to the bottom end of the Polish labor market.

Another indicator of migrant human capital – the level of education at the time of the study – does not substantially influence the probability of the given type of trajectory (Model 1b, ) suggesting that transferability of skills is limited in the case of migration from Ukraine to Poland. We observe the negative effect of primary or vocational education (vs. higher education) (10 p.p.) on the probability of escaping migrant niches, and positive effect of secondary and post-secondary education (10 p.p.) with respect to the cluster flexible employment sectors. These highlight differences between the two trajectories suggesting stronger educational selection in the case of the escaping migrant niches path associated with higher ends of the labor market. Interestingly, for the trajectory towards the new migrant niche we observe two effects: positive for primary and vocational (7 p.p.) and negative for secondary and post-secondary education (7 p.p.). We may thus suppose that the hospitality & catering sector, as a new migrant niche, accommodates both unskilled migrants and those performing part-time jobs during their studies.Footnote7

Finally, with respect to the place of destination in Poland, segmented assimilation to both ‘old’ niches is more probable among migrants resident in Warsaw – the traditional destination area for Ukrainian migrants. In addition, the path related to the masculinized construction niche is a domain of migrants from Western Ukraine. The stable settlement at the lower end of the Polish labor market – industry as a new unattractive migrant niche – has been, in turn, more popular for migrants residing in Wrocław – a relatively new destination area in Poland.

6. Discussion and conclusions

The 2014 Russian invasion of Ukraine, involving humanitarian and economic consequences for Ukrainian society, induced a substantial increase in migratory outflows to Europe, with Poland holding the first place as the European destination area. It also contributed to some changes and intensification of certain tendencies in migration and on the labor market observed already before the 2014 war. This is portrayed in differences between pre – 2014 war and post-war Ukrainian migrants to Poland with respect to their migratory and labor market trajectories.

As our research on Ukrainian migration to two big Polish cities – Warsaw and Wrocław – demonstrates, Ukrainian migration to Poland became more permanent, especially among post-war migrants. This trend had been traceable already before the 2014 war but accelerated after its outburst. Because legal grounds for long-term and settled migration were not liberalized in the 2010s in Poland, such an outcome can be linked to the war context. This extended a time-horizon of migrants in Poland due to limited chances for improvement of the political and economic situation in Ukraine in a short-term perspective, as is the case for refugees (Dustmann et al. Citation2017, Zakirova and Buzurukov Citation2021). Thus, although most of the migrants studied arrived in Poland as labor migrants, our results indicate that humanitarian drivers might have played a role in their migratory decisions. This resonates with previous studies (Donato and Ferris Citation2020, Ortensi and Ambrosetti Citation2021) pointing to the ambiguity in typifying migrants into humanitarian and economic migrants.

Results relating to differences between labor market trajectories of post-war and pre-war migrants are less straightforward than in the case of mobility patterns, as complexity of occupational paths does not allow for a clear-cut gradation of observed trajectories, as it is in the case of earnings or the labor market status (Bevelander and Pendakur Citation2014, Ruiz and Vargas-Silva Citation2018). Moreover, some changes, especially opening of new sectors for foreign employment in Poland have been observed already before the 2014 war. However, generally, the results demonstrate the existence of niching of both pre-war and post-war Ukrainian migrants on the Polish labor market. As many as five out of seven distinct clusters portray a pulling potential of the given sectors of employment. Three of them can be considered old migrant niches on the Polish labor market – agriculture, construction and domestic services (Brunarska et al. Citation2016) – while the remaining two – hospitality & catering, and industry – are new ones.

Importantly, it can be argued that with respect to niching, we do not observe a visibly stronger negative ‘immigration effect’ (Bakker et al. Citation2017) in the case of the post-2014 war cohort of Ukrainian migrants, i.e. a clear tendency to locate in lower segments of the Polish labor market than with pre-war migrants. If we consider agriculture and industry as the least attractive sectors of employment, the two related trajectories are, respectively, ‘intermittent circulation & labor market trajectories’ and ‘stable settling at the lower segment’. Where they both differ from other trajectories is (moderately) decreasing shares of migrants employed in the sectors in question over time. However, the first of these is distinctive due to the intensive circulation of migrants between Poland and Ukraine, while the second stands out as the most permanent in terms of mobility patterns. As expected, the post-war migrants were less likely than their pre-war counterparts to pursue an intermittent circulation type of trajectory linked to the unattractive agriculture sector. If they remained at the bottom of the labor market, it was rather within industry, where employment involves longer uninterrupted stays in Poland. Our results may underestimate the presence of post-war migrants, i.e. more recent migrants, in the agriculture, as we studied Ukrainians already resident in cities. However, the declining relative role of agriculture as a sector employing foreigners in Poland after 2013 has also been documented in previous studies (e.g. Górny and Kaczmarczyk Citation2020).

Clearly, the post-war migrants were more likely than pre-war migrants to operate in relatively new migrant niches, which can be related to their formation or expansion (Friberg and Midtbøen Citation2019) upon arrival of substantial numbers of Ukrainian migrants to Poland in a short time-span after 2013. Next to industry, it applies to hospitality & catering linked to the trajectory we have labeled, ‘penetration of the labor market towards a new migrant niche’. It is characteristic of relatively high diversity of labor market trajectories including also non-working periods. We observe a pulling potential of hospitality & catering as a new migrant niche in the growing concentration of migrants in this sector over time passing since their first arrival in Poland in the described cluster, but this potential is smaller than in the case of the old migrant niches of construction and domestic services. Therefore, while referring to trajectories related to the two later sectors, we use the notion of ‘transnational segmented assimilation into masculinized/feminized migrant niche’. Importantly, according to our results, the old migrant niches attracted post-2014 war migrants. In fact, they were even more likely than pre-war migrants to pursue a segmented assimilation trajectory in the construction sector, while in the case of domestic services differences between the two groups were insignificant. Based on our results, we can additionally argue that the post-war inflow contributed to the revival of the construction niche with respect to foreign employment.

Post-war migrants were also more likely than pre-war migrants, especially than those from earlier cohorts (pre-2008 cohorts), to follow a trajectory that we call ‘penetration of the labor market – flexible employment sectors’ such as various services, trade and transport. In this way they contributed to the process of opening up new sectors of the Polish labor market to foreign employment, which had already begun before the 2014 war. Importantly, this trajectory was more likely for people with secondary and post-secondary education than for highly educated migrants.

Contrary to our expectations, we have not observed significant differences between post-war and pre-war migrants considering the likelihood of following the trajectory ‘gradual entry into the labor market – escaping migrant niches’ that can be considered as superior, as it is not related to the niching process and refers to higher ends of the labor market. In this cluster, incidences of economic inactivity were relatively high, but were decreasing over time; the majority of migrants started from employment outside of the migrant niches, and the proportion of such employment grew in time. A lack of differences between pre-war and post-war migrants in propensity to follow this superior labor market trajectory does not correspond either to conclusions from the previous studies regarding relatively strong negative immigration effect (e.g. Cortes, Citation2004, Colic-Peisker and Tilbury, Citation2006, Ruiz and Vargas-Silva, Citation2018), or to results pointing to the comparatively fast catch-up effect in the case of refugees (Connor Citation2010, Dustmann et al. Citation2017). We interpret this result by particular selection mechanisms in the case of a mix of economic and humanitarian drivers in post-war Ukrainian migration to Poland, when compared to asylum seekers in other contexts. In particular, the cluster denoting escaping migrant niches involves the strongest selection patterns. Its significant predictors, with strong effects, encompass enrolment in studies in Poland, higher vs. primary education, and possession of permanent or temporary residence permits. The results of our study thus fit into the numerous studies (Chiswick Citation1978, De Vroome and Van Tubergen Citation2010, Dustmann et al. Citation2017) advocating that the level of human capital and its accumulation constitute decisive factors in shaping the economic integration of both voluntary and involuntary migrants.

Gender differences are not substantial in relation to mobility patterns, but visible in labor market trajectories. Above all, two clusters of segmented assimilation towards ‘old’ niches – construction and domestic services – provide for the clear gendered patterns. Women were also more likely to pursue a trajectory leading to a new migrant niche – hospitality & catering. Interestingly, a significant predictor of belonging to the two female-dominated trajectories is enrolment in studies during the first stay in Poland, which indicates accumulation of the Poland-specific human capital and its relatively high levels among migrants. It is thus likely that employment in hospitality & catering as well as in domestic services constitutes a transitory phase in the labor market trajectories of Ukrainian, mainly female, migrants, and possibly also forms a source of income during studies in Poland. For the feminized migrant niche in domestic services, it would imply a change of its character, as in previous times it was dominated by middle-aged women working full time in cleaning and carrying services (Brunarska et al. Citation2016). We do not observe a predomination of any gender in the three clusters relating to two edges of the labor market – agriculture, industry and employment beyond migrant niches if we take into account human capital.

To conclude, the growth of permanency in numerically high Ukrainian migration to Poland, according to our results stimulated by the 2014 Russian invasion, can have negative effects for the demography of an ageing Ukrainian society. At the same time, the occurrence of humanitarian drivers of migration has not substantially challenged the tendency of Ukrainian migrants to locate in certain niches of the Polish labor market. However, the constellation of these niches has changed with the advent of new ones and the development of those forming already before the war. In particular, post – 2014 war migrants were more likely than earlier migrant cohorts to work in the new migrant niches, but contributed also to the revitalization of old ones. These tendencies are likely to continue influencing the structure of the Polish labor market. Importantly, we do not find evidence for a particularly strong negative immigration effect with respect to economic integration in the case of post-war migrants. On the one hand, this is a calming circumstance in the context of even bigger challenges being faced by Poland due to the massive humanitarian inflow from Ukraine after the 2022 Russian invasion. On the other hand, however, the supremacy of humanitarian factors in this most recent migration generates a new context for Ukrainians’ integration in Poland.

Our study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, we examined migrants surveyed in 2018–2019 using retrospective information about their migration and we limited our analyzes to individuals who continued migration until the time of the study. However, conducting longitudinal analyses of temporary migrants poses other substantial challenges regarding selection of migrants. Moreover, we had only general information about sectors of employment during the given stay. Thus, we had to remove from our analytical sample migrants staying in Poland for longer periods and reporting several sectors of employment during their stays in Poland, as we were incapable of reconstructing their full labor market trajectories. They accounted, however, for only a small fraction of our sample (below 3%). Furthermore, we had no data on language proficiency of migrants at the beginning of their migration project, which constitutes a crucial predictor of economic integration. Notwithstanding those limitations, our study constitutes the first attempt to reconstruct labor market trajectories of Ukrainian migrants to Poland. It is also a unique attempt to address labor market trajectories of temporary migrants in conjunction with their mobility patterns.

Acknowledgements

The analyses presented in this article were conducted within the Bekker 2020 Programme, funded by the Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange. We are grateful to the team at the Centre of Migration Research, University of Warsaw for their valuable comments and suggestions that greatly contributed to improving the final version of the paper.

Ethical approval

The surveys analyzed in the article were approved by the Research Ethic Committee of Centre of Migration Research, University of Warsaw (approval no. CMR/EC/08/2022). The code of ethics in the surveys was evaluated after the research, as the ethic approval was not required in Poland at the moment they were conducted (this is confirmed in the ethnical approval, available upon request). All participants have provided informed consent to take part in the survey by contacting the researchers by phone (making a call or sending an SMS requesting the contact) to make an appointment for an interview, and by coming to the research site for an interview.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (498 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The authors do not own the data and do not have copyrights for sharing the data. The data ownerships remain with National Bank of Poland for which the Centre of Migration Research in Warsaw did a study described in the article. Consequently, we could not deposit data in any repository. We prepared a replication package (but without data) which can be found online: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/UQME5

.Notes

1 Eurostat data (MIGR_RESFIRST); https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat.

2 Data on trends in the years 2005-21 for selected documents for work and temporary residence permits issued in Poland and applications for a refugee status for all foreigners and Ukrainians are presented in Figures A1-A4 in the supplementary material.

3 We refer to data on regions, as data on documents issued in cities are not publicly available.

4 More details on the sampling procedure are provided in the supplementary material.

5 The RDS method does not pose firm geographical boundaries, as recruitment is in the hands of the respondents. However, since respondents are asked to come to the research site in the city center, only those living within reach of public transportation are usually inclined to participate in the research.

6 However, due to small numbers of cases especially in the pre-2008 cohort these observations should be interpreted with care.

7 Referring also to the significant effect of enrolment to Polish studies described earlier.

References

- Adda, J., Dustmann, C. and Görlach, J.-S. (2021) ‘The dynamics of return migration, human capital accumulation, and wage Assimilation’, SSRN Electronic Journal 14333: 1–15.

- Akresh, I. R. (2008) ‘Occupational trajectories of legal US immigrants: downgrading and recovery’, Population and Development Review 34(3): 435–56.

- Anders, J., Burgess, S. and Portes, J. (2018) The Long-Term Outcomes of Refugees: Tracking the Progress of the East African Asians. IZA Discussion paper series, (11609).

- Andersson, G. and Scott, K. (2005) ‘Labour-market status and first-time parenthood: The experience of immigrant women in Sweden, 1981-97’, Population Studies 59(1): 21–38.

- Bakker, L., Dagevos, J. and Engbersen, G. (2017) ‘Explaining the refugee gap: a longitudinal study on labour market participation of refugees in The Netherlands’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43(11): 1775–91.

- Barbiano di Belgiojoso, E. (2019) ‘The occupational (im)mobility of migrants in Italy’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45(9): 1571–94.

- Bevelander, P. and Pendakur, R. (2014) ‘The labour market integration of refugee and family reunion immigrants: A comparison of outcomes in Canada and Sweden’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40(5): 689–709.

- Bratsberg, B., Raaum, O. and Røed, K. (2014) ‘Immigrants, labour market performance and social insurance’, Economic Journal 124(580): F644–F683.

- Brell, C., Dustmann, C. and Preston, I. (2020) ‘The labor market integration of refugee migrants in high-income Countries’, The Journal of Economic Perspectives 34(1): 94–121.

- Brunarska, Z., Kindler, M., Szulecka, M., and Toruńczyk-Ruiz, S., 2016. Ukrainian migration to Poland: A ‘local’ mobility? In: O. Fedyuk, and M. Kindle, eds., Ukrainian Migration to the European Union. IMISCOE Research Series. Cham: Springer Science and Business Media B.V., 115–31.

- Catanzarite, L. and Aguilera, M. B. (2002) ‘Working with co-ethnics: earnings penalties for latino immigrants at latino jobsites’, Social Problems 49(1): 101–27.

- Chiswick, B. R. (1978) ‘The effect of americanization on the earnings of foreign-born Men’, Journal of Political Economy 86(5): 897–921.

- Colic-Peisker, V. and Tilbury, F. (2006) ‘Employment niches for recent refugees: segmented labour market in twenty-first century Australia’, Journal of Refugee Studies 19(2): 203–29.

- Connor, P. (2010) ‘Explaining the refugee gap: economic outcomes of refugees versus other immigrants’, Journal of Refugee Studies 23(3): 377–97.

- Cornwell, B. (2015) ‘Theoretical foundations of social sequence Analysis’, in B. Cornwell (ed.), Social Sequence Analysis. Methods and Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 21–55.

- Cortes, K. (2004) ‘Are refugees different from economic immigrants? some empirical evidence on the heterogeneity of immigrant groups in the United States’, Review of Economics and Statistics 86(2): 465–80.

- De Vroome, T. and Van Tubergen, F. (2010) ‘The employment experience of refugees in The Netherlands’, International Migration Review 44(2): 376–403.

- Donato, K. M. and Ferris, E. (2020) ‘Refugee integration in Canada, Europe, and the United States: perspectives from Research’, Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 690(1): 7–35.

- Drbohlav, D. and Jaroszewicz, M., eds. (2016) Ukrainian Migration in Times of Crisis: Forced and Labour Mobility, Prague: Charles University, Faculty of Science.

- Dustmann, C., Fasani, F., Frattini, T., Minale, L., Schönberg, U. and Schö, U. (2017) ‘On the economics and politics of refugee migration’, Economic Policy 32(91): 497–550.

- Fedyuk, O. and Kindler, M. (2016) Ukrainian Migration to the European Union, Cham.: IMISCOE Research Series. Springer.

- Fleischmann, F. and Höhne, J. (2013) ‘Gender and migration on the labour market: additive or interacting disadvantages in Germany?’, Social Science Research 42(5): 1325–45.

- Friberg, J. H. and Midtbøen, A. H. (2019) ‘The making of immigrant niches in an affluent welfare State’, International Migration Review 53(2): 322–45.

- Fuller, S. (2015) ‘Do pathways matter? linking early immigrant employment sequences and later economic outcomes: evidence from Canada’, International Migration Review 49(2): 355–405.

- Gabadinho, A., Ritschard, G., Müller, N. S. and Studer, M. (2011) ‘Analyzing and visualizing state sequences in R with TraMineR’, Journal of Statistical Software 40(4): 1–37.

- Górny, A. (2017a) ‘Eastwards EU enlargements and migration transition in central and Eastern Europe’, Geografie-Sbornik CGS 122(4): 476–99.

- Górny, A. (2017b) ‘All circular but different: variation in patterns of Ukraine-to-Poland migration’, Population, Space and Place 23(8): 1–10.

- Górny, A., Grabowska-Lusińska, I., Lesińska, M. and Okólski, M., eds., (2010) Immigration to Poland: Policy, Employment, Integration, Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar.

- Górny, A. and Kaczmarczyk, P., 2020. Temporary farmworkers and migration transition. On a changing role of the agricultural sector in international labour migration to Poland. In: J.F. Rye and K.A. O’Reilly. International Labour Migration to Europe’s Rural Regions. London: Routledge, pp. 86–103.

- Górny, A., Kołodziejczyk, K., Madej, K. and Kaczmarczyk, P. (2019) Nowe obszary docelowe w migracji z Ukrainy do Polski. Przypadek Bydgoszczy i Wrocławia na tle innych miast. CMR Working Papers, 118/176, Warsaw: Universtiy of Warsaw.

- Górny, A., Madej, K. and Porwit, K. (2020) Ewolucja czy rewolucja? Imigracja z Ukrainy do aglomeracji warszawskiej z perspektywy lat 2015-2019. CMR Working Papers, 123/181, Warsaw: Universtiy of Warsaw.

- Górny, A. and Śleszyński, P. (2019) ‘Exploring the spatial concentration of foreign employment in Poland under the simplified procedure’, Geographia Polonica 92(3): 258–78.

- Górny, A. and Van der Zwan, R. (2023) Mobility and labor market trajectories of Ukrainian migrants to Poland in the context of the 2014 Russian invasion of Ukraine. Replication Package.

- Halpin, B., 2019. Introduction to sequence analysis. In: H.P. Blossfeld, G. Rohwer, and T. Schneider, eds. Event History Analysis With Stata. London: Routledge, pp. 282–307.

- Heckathorn, D. (1997) ‘Respondent-Driven sampling: a new approach to the study of hidden populations’, Social Problems 44(2): 174–99.

- Heckathorn, D. (2007) ‘6 extensions of respondent-driven sampling: analyzing continuous variables and controlling for differential Recruitment’, Sociological Methodology 37(1): 151–208.

- Kleinepier, T., de Valk, H. A. G. and van Gaalen, R. (2015) ‘Life paths of migrants: A sequence analysis of Polish migrants’ family life trajectories’, European Journal of Population 31(2): 155–79.

- Klinthäll, M. (2007) ‘Refugee return migration: return migration from Sweden to Chile, Iran and Poland 1973-1996’, Journal of Refugee Studies 20(4): 579–98.

- Liebig, T. and Tronstad, K. R. (2018) Triple Disadvantage? A First Overview of the Integration of Refugee Women, Paris.: OECD Publishing.

- Lücke, M. and Saha, D. (2019). Labour Migration from Ukraine: Changing Destinations, Growing Macroeconomic Impact. Policy Studies Series. Berlin: German Advisory Group.

- Lumley-Sapanski, A. (2021) ‘The survival Job trap: explaining refugee employment outcomes in Chicago and the contributing Factors’, Journal of Refugee Studies 34(2): 2093–123.

- Midtbøen, A. H. and Nadim, M. (2019) ‘Ethnic niche formation at the top? second-generation immigrants in Norwegian high-status occupations’, Ethnic and Racial Studies 42(16): 177–95.

- Ortensi, L. E. and Ambrosetti, E. (2021) ‘Even worse than the undocumented? assessing the refugees’ integration in the labour market of lombardy (Italy) in 2001–2014’, International Migration 60(3): 20–37.

- Perales, F., Lee, R., Forrest, W., Todd, A. and Baxter, J. (2021) ‘Employment prospects of humanitarian migrants in Australia: does gender inequality in the origin country matter?’, Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies 0(0): 1–15.

- Piore Michael, J. (1979) Birds of Passage: Migrant Labor and Industrial Societies, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Potocky-Tripodi, M. (2004) ‘The role of social capital in immigrant and refugee economic adaptation’, Journal of Social Service Research 31(1): 59–91.

- Rendall, M. S., Tsang, F., Rubin, J. K., Rabinovich, L. and Janta, B. (2010) ‘Trajectoires d’intégration des immigrées sur le marché du travail: Une comparaison entre l’Europe de l’Ouest et l’Europe du Sud’, European Journal of Population 26(4): 383–410.

- Ruiz, I. and Vargas-Silva, C. (2018) ‘Differences in labour market outcomes between natives, refugees and other migrants in the UK’, Journal of Economic Geography 18(4): 855–85.

- Salikutluk, Z. and Menke, K. (2021) ‘Gendered integration? How recently arrived male and female refugees fare on the German labour market’, Journal of Family Research 33(2): 284–321.

- Sańchez-Domińguez, M. and Fahleń, S. (2018) ‘Changing sector? social mobility among female migrants in care and cleaning sector in Spain and Sweden’, Migration Studies 6(3): 367–99.

- Sánchez-Soto, G. and Singelmann, J. (2017) ‘The occupational mobility of Mexican migrants in the United States’, Revista Latinoamericana de Población 11(20): 55–78.

- Şimşek, D. (2020) ‘Integration processes of Syrian refugees in Turkey: ‘class-based integration’’, Journal of Refugee Studies 33(3): 537–54.

- Sperandei, S., Bastos, L.S., Ribeiro-Alves, M., Reis, A., and Bastos, F.I., 2021. Evaluation of Logistic Regression Applied to Respondent-Driven Samples: Simulated and Real Data, (ArXiv preprint arXiv:2101.04253), 1–23.

- Stanek, M. and Ramos, A. V. (2013) ‘Occupational mobility of migrants’, Evidence from Spain. Sociological Research Online 18(4): 158–66.

- Stempel, C. and Alemi, Q. (2021) ‘Challenges to the economic integration of Afghan refugees in the U.S’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47(21): 4872–92.

- Tyldum, G. and Johnston, L. eds., (2014) Applying Respondent Driven Sampling to Migrant Populations. Lessons from the Field, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Van Tubergen, F. (2022) ‘Post-Migration education Among refugees in The Netherlands’, Frontiers in Sociology 6: 1–11.

- Waxman, P. (2001) ‘The economic adjustment of recently arrived bosnian, ahban and Iraqi refigees in Sydney, Australia’, International Migration 35(2): 472–505.

- Wright, R., Ellis, M. and Parks, V. (2010) ‘Immigrant niches and the intrametropolitan spatial division of labour’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 36(7): 1033–59.

- Zakirova, K. and Buzurukov, B. (2021) ‘The road back home is never long: refugee return Migration’, Journal of Refugee Studies 34(4): 4456–78.