ABSTRACT

An early start to good-quality early childhood education and care (ECEC) is considered beneficial, especially for disadvantaged children's development and educational outcomes. This assumption was tested using the latest two waves (2015 and 2018) of data from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) in five countries using the Nordic model of early education and care: Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden. The article finds evidence of the overall positive association between the age of entry in ECEC and literacy at age 15 in all Nordic countries. However, the relationship is non-linear, and the highest benefits seem to occur following entry into ECEC from ages two to three. The link between family background and ECEC enrollment largely explains this association. We did not find that ECEC would generally compensate for low socioeconomic status (SES) in children’s achievement. However, the Matthew effect was observed in Norway, where an early ECEC start is more strongly associated with literacy scores for affluent children than disadvantaged children. These findings have limitations due to their correlational nature. Still, this article indicates that even in high-quality universal ECEC systems, early preschool education is not a panacea for lowering achievement gaps due to parental background.

Introduction

Human capital theory suggests that early investments in children’s education are crucial because learning is cumulative, and the earlier such investments are made, the higher the profits (Heckman Citation2000, Citation2006; Heckman and Masterov Citation2007). Combined with supporting maternal employment, universal early childhood education and care (ECEC) has been seen as a social investment that can increase society's productivity while reducing inequalities when targeting these services at disadvantaged children (Esping-Andersen Citation2008). Indeed, differences in children's skills according to the family background have been observed before school age (Bradbury et al. Citation2015). Many studies show that high-quality ECEC can support the learning and educational attainment of disadvantaged children in particular, thus reducing societal inequalities (Burger Citation2010; Melhuish et al. Citation2015). This has also been found in studies examining universal ECEC (Drange and Havnes Citation2018; van Huizen and Plantenga Citation2018; Dietrichson et al. Citation2020). Because of its importance for society, early childhood education has become an important element in the public discourse and as a political objective. The World Bank (Citation2023) states that the ECEC is ‘the smartest thing a country can do to eliminate poverty’. In contrast, the OECD has actively supported the design of new childcare policies through intensive data collection and reporting for more than two decades. In addition, the Barchelona objectives, a plan that aimed to turn Europe's economy into a competitive and knowledge-based one, saw within ECEC a way to strengthen human capacities. According to these objectives, 33% of children under the age of three years and 90% of children above the age of three years should ideally attend childcare, with the eventual goal of near-universal childcare attendance (European Council Citation2013).

Parents have primary responsibility for raising children. Still, especially in the Nordic countries, societal responsibility is also significant, as reflected in universal, subsidized, and high-quality ECEC. The Nordic countries are considered the golden standard for family policies (Thévenon Citation2011). A comprehensive family policy aims to support mothers’ employment, increase the fathers’ share of childcare, and help reconcile work and family life (Daly Citation2020). The intention is that after parental leave, both parents will return to work, and the child will participate in ECEC. High-quality ECEC also facilitates parental return to the labor market. In the Nordic countries, school starts at six to seven years old, so children spend a relatively long time in ECEC before starting school.

Due to these characteristics, we can discuss the ‘Nordic model’ of early education, partly due to these countries’ social-democratic universalistic welfare state model (Esping-Andersen Citation1999). The characteristics of this model are universal early education from the age of one, high-quality programs of homogenous quality, and public education. Preschool education is conceived as a right for all children and independent of parental conditions. Childcare is also heavily subsidized, making it accessible and affordable to low-income families. Consequently, participation rates in early formal childcare services are very high in the Nordic countries. Nevertheless, despite the similarities in the Nordic countries, there are significant differences in how family policies guide ECEC enrollment; this is reflected in the differences in the internal organization of ECEC in each country. For example, in Finland and Norway, children's home care is supported by cash benefits. In four of the five countries, entrance to ECEC is a legal right, the only exception being Iceland. The total rates of attendance also varied in the data for the 2015 and 2018 cohorts examined by the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), with the highest attendance of three-year-olds in Iceland and Denmark (91% and 81%), followed by Sweden and Norway (76% each), and the lowest participation in Finland (36%, see European Commission Citation2009). The differences in how these countries’ childcare is organized and their populations’ uptake of ECEC, which varies according to the children's age, can be expected to influence the disparities in child outcomes. Because of the many common features of ECEC and parental policies in the Nordic model, a comparison among them is more likely to show whether the small differences in the design of otherwise highly efficient policies matter for children and the social inequality in early education, and if so, how.

This article defines ECEC as the institutional combination of care and education before primary school. It relies on the two most recent waves of PISA data and contributes to the literature by examining the association between the starting age of ECEC and high school literacy scores across five Nordic countries. Studies have often shown an interest in how ECEC benefits children compared to home care, but no full consensus exists on how ECEC participation at different ages is linked to children's educational attainment (Burger Citation2010). In this work, we study children as the central agents, relying on the available student reports in all the studied countries. We also assess whether an early start reduces educational inequality. Although single-country analyses on this topic exist, only a few studies include cross-country comparisons (see Cebolla-Boado et al. Citation2016; Dämmrich and Esping-Andersen Citation2017). Finally, these five Nordic countries have not previously been compared using the same data, so this study examines this issue from a novel perspective.

Theoretical mechanisms: the human capital perspective, compensation, and the Matthew effect

The human capital perspective assumes that investment in human capital – or the skills and knowledge acquired through education and training (Becker Citation1962) – increases the cognitive potential of individuals. According to James Heckman (Citation2000, Citation2006), investments in individuals should be made as early as possible because learning is cumulative, so early investment offers the best returns on children's human capital accumulation. It is also often emphasized that early childhood (0–3 years) is a significant time for brain development in children (Shonkoff and Phillips Citation2000). Positive events in this period can enhance a child's potential, while adverse events can significantly reduce children's capacities (Heckman Citation2012). Both families and educational institutions have increasingly become aware of the importance of supporting children during their early years. On the one hand, we know more about specific parenting styles that increase children's school-related skills (Lareau Citation2003). The quality of the home environment is transforming due to the constant pressure to improve children's intellectual stimulation and parental interaction (Kulic et al. Citation2017). On the other hand, a longer exposure to schooling is a crucial element in human capital formation. This focus on duration is accompanied by a growing focus on improving quality in ECEC, regarded as essential for positive outcomes (Burger Citation2010). Therefore, more years of (high-quality) ECEC are expected to be associated with better cognitive achievement.

Moreover, investing in the human capital of disadvantaged children is thought to reduce inequalities and benefit society's productivity (Heckman and Masterov Citation2007). However, a more nuanced analysis of the potential of investment to benefit disadvantaged children uncovers two parallel perspectives on how ECEC attendance can relate to social inequalities. The first perspective assumes that ECEC will attenuate inequalities because more disadvantaged children will likely experience increased benefits. This means that early education will be able to compensate disadvantaged children for their initial disadvantage (Magnuson and Shager Citation2010). The low socioeconomic position of families may deprive children of the right conditions for their development, whereas a longer exposure to good quality education may reverse these patterns (Burger Citation2010; Kulic et al. Citation2017). The second perspective assumes that ECEC can also increase inequalities, for instance, because children from highly educated families will be able to profit more from ECEC either due to their gene and environmental interaction, as mentioned above (Tucker-Drob and Harden Citation2012) or because of the more careful selection of ECEC institutions undertaken by their families (Augustine et al. Citation2009). In other words, the differential effects of ECEC on outcomes conditional on attendance will favor children from socioeconomically advantaged families. In the literature, this is known as the Matthew effect (Rigney Citation2010). The examples of more advantaged children benefiting more from schooling are found throughout countries and even in the Nordic egalitarian context. Nennstiel (Citation2022) reports for Germany that after controlling for initial student achievement, achievement gaps by parental socioeconomic status (SES) grow over schooling career net of school attendance, while they remain stable if prior achievement is not considered. Sandsør et al. (Citation2023) instead find a consistent and unconditional growth of the achievement gap by parental income from primary to secondary school in Norway. The Matthew effect is reported even in the interventions in home environments, which are found to be more effective for middle-class parents than low-class parents (for a review, see Bakermans-Kranenburg et al. Citation2005). Moreover, the Matthew effect also appears in preschool attendance, as more advantaged children are more likely than disadvantaged children to use formal childcare independent of the employment situation of their families (Pavolini and Van Lancker Citation2018; Kulic et al. Citation2019; Wood et al. Citation2023).

Both mechanisms, attenuation of disadvantage and an increase in advantage, can be in place simultaneously, and they will depend on the institutional features of the context studied. Countries characterized by a stronger selection of childcare but without universal attendance in preschool institutions are often found to reproduce the patterns of the Matthew effect (Magnuson et al. Citation2007; Gambaro et al. Citation2014). In contrast, good-quality and highly universal systems can be expected to promote a wider compensation for those disadvantaged because all families are equally likely to access and profit from ECEC attendance (Esping-Andersen et al. Citation2012). High selection into better quality institutions according to SES background is therefore less likely. The specific hypotheses in this article are based on the theoretical expectations of a positive effect of an early start to ECEC on human capital formation and specificities of the family and early education policies of the Nordic countries that guarantee universal access to ECEC and its high quality. The latter leads to an expectation of compensation for the low start of disadvantaged children but to a different degree depending on specific country contexts, as detailed below.

Empirical evidence on (universal) ECEC and educational outcomes

This section presents an overview of studies on the overall benefits of early education – particularly for children from low-educated or low-income families – and studies about the role of age of entry into ECEC for child cognitive achievement.

The effects of ECEC participation

A plethora of research summarizes the effects of ECEC participation on achievement. A review of these results and the most recent meta-analyses of intervention studies on disadvantaged children find a positive effect of ECEC interventions. Nores and Barnett (Citation2010) review non-US evidence on the effects of early childhood programs from quasi-experimental and experimental studies in 23 countries. They report noteworthy benefits for (disadvantaged) participants in cognitive and non-cognitive development, health, and future educational outcomes, particularly for more stimulating programs. Camilli et al. (Citation2010) reviewed 123 studies and conducted a meta-analysis of quasi-experimental and randomized studies, finding significant gains for children who attended a preschool program before kindergarten, particularly in cognitive development. These authors highlighted the importance of an early entry to these gains. McCoy et al. (Citation2017) focused instead on medium- and long-term outcomes of early childhood interventions. Their meta-analysis shows that attending ECEC reduces special education needs and grade retention and positively impacts graduation (of disadvantaged children).

However, the observational studies that used sources of international competence data like ours, such as PISA or the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS), have not fully clarified the association of preschool education with future cognitive outcomes in primary and secondary school. Strietholt et al. (Citation2020) do not find a consistent positive effect of preschool expansion on achievement using longitudinal PIRLS and PISA data components. In addition, Hogrebe and Strietholt (Citation2016) show that in only two out of eight countries in PIRLS data from 2011 (e.g. Singapore and Sweden, but not Norway), preschool attendance (of disadvantaged children) is significantly associated with later student achievement. Dämmrich and Esping-Andersen (Citation2017) found that preschool participation was associated with better literacy outcomes in primary school but not secondary school.

The role of starting age

Most of the literature above on interventions claims that an earlier start is better. However, the number of studies that test the role of age of entry for cognitive and non-cognitive development is limited, and the results are inconclusive. Han et al. (Citation2001) find for the US that entering preschool in infancy may harm advantaged children. Han et al. (Citation2001) report behavioral problems at ages seven and eight among American children who presumably attended childcare in the first nine months after birth while their mothers worked. In another American study (Loeb et al. Citation2007), the authors find that the optimal age to enter preschool is between age two and three, as entering at a younger age does not show particular benefits or even harms preschool skills. They also find significant behavioral problems for children entering at age two, particularly for those entering below the age of one.

In the Nordic context, however, an earlier start is, on average, seen as positive. In Sweden, children who started ECEC before age one performed better in school and on socio-emotional outcomes at ages 8 and 13 than those who started ECEC later or did not participate in ECEC at all (Andersson Citation1989, Citation1992). In two studies that dealt with cohorts born in the early 2000s, an earlier start in ECEC in Norway was found to have a positive effect on language and math skills at the age of three and seven, especially for children of low-educated and low-income families (Dearing et al. Citation2018; Drange and Havnes Citation2018). In Finland, ECEC beginning at ages two and four were each found to provide a better option for children's educational attainment than home care (Karhula et al. Citation2017; Kosonen and Huttunen Citation2018). In Finland, these effects have been found not to vary in terms of family background (Karhula et al. Citation2017; Kosonen and Huttunen Citation2018). In contrast, in Germany, children who started universal ECEC three months earlier did not perform differently on cognitive tests compared to children who started later, regardless of family background (Kuehnle and Oberfichtner Citation2020). In England, early schooling before the age of five increased test scores at ages five and seven, but this effect was no longer visible when children were 11 (Cornelissen and Dustmann Citation2019). Finally, Cebolla-Boado et al. (Citation2016) studied literacy outcomes in a comparative study of 28 developed countries using 2011 PIRLS survey data. They find that the longer children spend time in preschool (thus, the earlier they enter), the better they succeed in literacy tests in the fourth grade. This benefit was greater for children of low-educated parents. The study shows that the length of preschool has a positive overall association with literacy outcomes in fourth-grade children in Denmark and Sweden, but the association is negative in Finland. However, a more detailed examination shows that ECEC has a compensatory association with literacy outcomes in Denmark and Finland, while in Sweden, no such compensation was observed.

ECEC in the Nordic countries

The different combination of the main ECEC characteristics, including the availability of cash for care schemes and the availability, costs, and quality of ECEC, might make certain countries better equipped to compensate for the disadvantaged position of specific groups, including low-SES children.

The features of the Nordic family policy are a relatively long paid parental leave and a universal, mainly publicly funded, subsidized, and high-quality ECEC (Thévenon Citation2011). The income-protected parental leave length was about 9–12 months in the early 2000s in the Nordic countries. In Denmark, Finland, and Sweden, school starts the year the child turns seven, but children participate in preschool in the year when they turn six. In Norway and Iceland, school starts the year the child turns six.

Before entering pre-primary or primary school, children can participate in ECEC, the features of which are described in . The data in the table has been collected to best describe the years 2000–2008, when the target group for this study participated in ECEC. Comparing ECEC systems in different countries is challenging because the institutions and policies of countries vary widely. In addition to national guidelines, the Nordic welfare policy also strongly involves local decision-making, which is why large differences exist in the organization of ECEC services between municipalities.

Table 1. Characteristics of Nordic ECEC in the early 2000s.

Enrollment to ECEC

ECEC can start at a very young age. Except for Iceland, children in Nordic countries have a legal right to early childhood education after parental leave (European Commission Citation2015). In Denmark, ECEC can be started at around 8 months of age, in Finland at around 10 months, and in Sweden and Norway at around 12 months. In Iceland, ECEC can start at 18 months, but before that, the child can attend in-home childcare (The Nordic Council and the Nordic Council of Ministers Citationn.d.).

Between 2000 and 2005, the proportion of three-year-olds participating in ECEC was over 90% in Iceland, over 80% in Denmark, over 75% in Norway and Sweden, and around 36% in Finland. For four-year-olds, ECEC participation was over 90% in Iceland and Denmark, over 80% in Norway and Sweden, and around 45% in Finland. In the EU-27 countries, the corresponding figures were 66% for three-year-olds and 83% for four-year-olds (European Commission Citation2009). Participation is thus significantly higher in Denmark and Iceland than in the EU-27 generally. In Norway and Sweden, the participation rate was about 10 percentage points higher for three-year-olds and around the EU-27 average for four-year-olds. In Finland, the ECEC participation rate of three- and four-year-olds was almost 50% lower than the EU-27 average. Finland's low ECEC participation rate has been considered linked to the comprehensive home care allowance system (Thévenon Citation2011). Moreover, we can see that in 2017, the ECEC participation rate increased in all countries to 74% in Finland and over 90% in other countries for three-year-olds.

The official ECEC participation rate in Denmark and Iceland is highly similar to that reported in the PISA data. In Sweden, Norway, and Finland, the participation rate in the PISA data is somewhat higher than the Eurydice Report mean for 2000–2005 (European Commission Citation2009). In Finland, the participation rate of four-year-olds in the PISA survey is 17 percentage points higher than in the report. However, the Eurydice Report looks at center-based ECEC. In Finland, for example, almost a third of children in 2000 and about a quarter in 2005 were in family-based ECEC (Säkkinen and Kuoppala Citation2016). Therefore, the figures in the Eurydice Report are not directly comparable with those in the PISA data.

Staff ratio, staff education and curriculum in ECEC

Denmark, Sweden, and Iceland have no regulations for staff-child ratio or group size at the national level, as these are decided locally (European Commission Citation2009). In 2003, Denmark’s staff–child ratio was 1:3.3 for children aged 0–2 years old and 1:7.2 for children aged 3–5 years. In Sweden, the staff–child ratio is typically 1:5–6. In Iceland, the mean staff–child ratio for 2000–2008 was 1:5.5 for all children under school age based on our calculation from the Statistics Iceland database (Statistics Iceland Citation2023a, Citation2023b).

In Norway and Finland, group size is decided locally, but the staff–child ratio has a national guideline. In Finland, the ratio is 1:4 for 0–2-year-olds and 1:7 for 3–5-year-olds. In Norway, the staff–child ratio is computed per trained pedagogue and is 1:7–9 for 0–3-year-olds and 1:14–18 for 3–6-year olds. The proportion of children participating in full-time family day care is 4–5 children per caregiver in the Nordic countries (European Commission Citation2015).

In all Nordic countries, kindergarten teachers have a tertiary education, but there are also other care staff with lower educational qualifications. In Iceland, tertiary education is a master’s degree, and in other countries, a bachelor’s degree (European Commission Citation2009). The proportion of highly educated staff working with children under three is 60% in Denmark and 51% in Sweden. The proportions are lower in Finland, Iceland, and Norway, at 30%, 34%, and 35%, respectively. The ECEC curriculum is in use in all Nordic countries, but in Finland, it has only been applied to preschools since the early 2000s.

ECEC fees, share of GDP, and home care allowances

ECEC is mainly funded at the local level in most Nordic countries, but in Finland and Sweden, it is also funded at the national level. ECEC fees are publicly subsidized on both the public and the private side. In Sweden, for example, ECEC for three-year-olds is free to all children for 19 hours a week, while in Finland, Sweden, Denmark, and Norway, payments are linked to family size and income. In Iceland, the fees are decided by the municipalities (European Commission Citation2015). ECEC fees, on average, cover 22% of the service cost in Denmark and 15% in Finland. In Iceland, the maximum cost was about 25% (but in 2018). In Norway, ECEC pays a maximum of 20% to families, and in Sweden, the price of services is 11% of the cost of services. also shows the mean of total public expenditure in 2000–2008 on ECEC by its percentage of GDP. Denmark has the largest allocation, at 1.36%. In Sweden and Iceland, the allocation is at essentially the same level, 1.19% and 1.14%. The smallest allocations are in Finland and Norway, 0.89 and 0.77%.

In addition to ECEC, the Nordic countries offer cash allowances that allow children to be cared for at home. Home care allowance is most extensive in Finland and Norway. In Finland, a home care allowance is available for the care of children under three years of age, and in Norway, for children under two years of age. However, in the early childhood of students in this study, a home care allowance was available in Norway for children under three years of age (Ellingsæter Citation2012). In addition, in Finland, home care allowances can also be received for the care of older children if the family has a child under the age of three benefiting from them. In Denmark and Iceland, it is also possible to receive a municipal home care allowance. However, it is not widely used. In Sweden, the home care allowance was unavailable between 2000 and 2007, when the students in this study were in early childhood (Giuliani and Duvander Citation2017).

Based on staff-child ratio, staff education, and total public expenditure, which connect to the quality of ECEC and the presence and use of cash-for-care schemes that discourage ECEC participation, it seems that Denmark and Sweden are the two countries that, overall, provide the best conditions for ECEC, followed by Norway, Finland, and Iceland. Against this background, we assume Denmark and Sweden are the forerunners in ECEC in the Nordic context, while Finland, Iceland, and Norway are falling behind.

Contribution of this research and hypotheses

There are theoretical expectations and empirical evidence that universal ECEC has a positive effect on children’s development and later outcomes. However, the results of country-specific studies may be difficult to compare because the definition of ECEC varies between studies. In addition, the benefits of ECEC would appear to be greater for children from a more disadvantaged family background. Furthermore, theoretically, the earlier the ECEC is started, the greater the benefit to the child. This would seem to support Heckman’s hypothesis of human capital accumulation.

Our study contributes to the literature by examining the association between the commencement of ECEC and long-term literacy by comparing five countries with universal high-quality childcare. By comparing countries with similar ECEC organizations but partially different access rates, costs, availability of specific schemes, and quality, we aim to evaluate the overall association between ECEC start and children's cognitive development. In addition, we study the potential of high-quality universal ECEC in compensating for the disadvantage of children in societies that invest in children using the PISA scores. This study's central focus is on the role of the starting age. The three research questions are as follows: (1) Is an earlier start in ECEC associated with better literacy scores among children? (2) Does it have a compensatory role for the literacy scores of low-SES children at the age of 15? (3) Are there differences between the Nordic countries in how the starting age for ECEC is associated with students’ literacy scores when they are 15 years old?

Overall, we expect a positive association between ECEC and literacy in the Nordic childcare policy model with relatively high quality, and we hypothesize that an earlier start is associated with higher literacy scores at the age of 15 (H1a). Given the differences across Nordic countries in the way ECEC is financed and organized, we expect that the average association will (be shown to) be strongest in Denmark and Sweden and weakest in Finland, Iceland, and Norway (H1b). Regarding SES differences, we expect to see patterns of compensation in all countries: the difference in literacy scores between the low- and high-SES students will prove to be smaller the earlier ECEC is started (H2a). Following the country rankings described in the previous section concerning the overall characteristics of ECEC and the availability of cash-for-care schemes, we further hypothesize that the compensation will be (seen to be) strongest in Denmark and Sweden and the least strong in Finland, Iceland, and Norway (H2b).

Data and methods

We employed pooled PISA data from 2015 and 2018. The data were cross-sectional; in the PISA survey, students took a two-hour exam and then responded to a background survey that examined, for example, the student’s home background and attitudes toward learning. In the Nordic countries, the responses to the background surveys were based on the responses reported by students in the 2015 and 2018 PISA surveys. Descriptive statistics are presented in Table A1 in the appendix.

As dependent variables in the study, we used literacy plausible value (PV) scores derived from a literacy test (OECD Citation2022b). For the analyses, we standardized the literacy scores by year and country, with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1.

Our main independent variable was the starting age of ECEC. Given that ECEC starts early in the Nordic countries, not many students in the sample started ECEC late, prompting us to use the pooled data. Students were asked at what age they started ECEC. In Finland and Sweden, the question about starting ECEC asked at what age they, as children, entered childcare or preschool. In Norway and Iceland, this question enquired about the age at which children started childcare; in Denmark, it asked at what age children started ‘børnehave’ or preschool. Børnehave is a childcare institution that starts at around the age of two to three years and lasts until the child begins preschool. In Denmark, children from zero to three years old attend ‘vuggestue’, a childcare institution that precedes børnehave attendance. The country differences regarding the start and the organization of ECEC require some caution in direct comparison between countries.

Response options for our independent variable were: ‘1 year of age or earlier’, ‘2 years of age’, ‘3 years of age’, ‘4 years of age’, ‘5 years of age’, ‘6 years of age or older’, ‘did not participate’, and ‘do not remember’. We combined the last two categories in each because starting late and not attending ECEC are relatively marginal in Nordic countries. In Denmark, the first answer is at the age of two or earlier, likely because børnehave begins at age two at the earliest. For Iceland and Norway, we looked at the differences between those who started ECEC at the ages of 0–1, 2, 3, and 4 or older or who responded that they did not participate. In Denmark, Finland, and Sweden, the final categories were ‘5 or older’ or ‘did not participate’. Approximately 25% of the answers in the data were ‘do not remember’.

Family background was described by a ready-made variable: the economic, social, and cultural status (ESCS) index. This index was formed via principal component analysis of parental education, parental occupation, and the family’s cultural and financial capital. The index was standardized, with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 among the students from the OECD countries (OECD Citation2017). We categorized the index into five classes by country and the year of the data; the graphical results compare students between the lowest and highest categories of ESCS.

Our analyses controlled for students’ basic demographic characteristics: gender, age in months, home language, and immigrant status. Although the students were of the same age, those born at the beginning and end of a year may have differences in the duration of their ECEC participation. An immigrant background, in turn, has been linked to lower academic achievement on average (Heath et al. Citation2008) and a later ECEC start (Cornelissen et al. Citation2018). We included only those students who began primary school at ages 5–7, the usual starting age range in the Nordic countries. In addition, students who had a missing value in the ESCS variable or the home language or immigration status variables were excluded from the analyses.

Around 25% of the students answered that they did not remember their starting age for ECEC, so we used multiple imputations to account for the possible bias due to these missing answers. We utilized Stata’s built-in multiple imputation tools (Mi estimate command); we ran an ordered logistic regression imputation where we predicted students’ ECEC starting age by their ESCS index, gender, immigration background, and home language. With multiple imputations, we created 10 multiply imputed datasets, from which Stata calculates 10 different regression coefficients and standard errors, combining these estimates into one set of statistics. After imputation, the maximum number of missing observations was 60 across all imputed samples. For our primary analyses, we performed multilevel linear regression, where we nested students in schools by adding the school id to our models. We also weighted the data using PISA’s final student weights and only the first plausible value for literacy as our dependent variable; our analyses with the imputation strategy do not allow us to utilize replicate weights when analyzing the set of plausible values. Instead of using a model-based approach, the OECD recommends using design-based methods to account for complex survey design when analyzing weighted replicate samples and plausible values (OECD Citation2023). However, using only one plausible value and utilizing final student weights has led to similar results (Jerrim et al. Citation2017).

For the robustness check analyses, we used the Repest package for Stata, which accounts for the hierarchy and sampling of the data (Avvisati and Keslair Citation2014). Repest was used to run analyses with weighted replicate samples and plausible values used in complex survey designs, such as PISA data. Two types of weights can be used with Repest. Here, final student weights were used because students and schools may not have the same probability of being selected for the sample. Replicate weights were used for balanced repeated replication to account for the sampling error when schools were selected. Moreover, student test scores may suffer from measurement error, so the test scores were partly imputed: the PISA survey relies on using 10 plausible values; thus, the students’ assumed competence can be calculated. Repest is not designed to work with imputed samples. Yet, we include controls for the missing answers in our regression models when running the robustness checks with Repest.

For each country, we applied multilevel ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models in two steps: first, the models contained the age of ECEC entry as the main independent variable; second, the models included the interaction between the age of ECEC entry and the student's ESCS. We observed the predicted values of literacy scores both overall and by each ESCS group.

The analyses included four major control variables considered stable over time, but they omitted other variables with these characteristics. The questionnaire did not provide useful information on individual health status, other relevant stable personal characteristics, or the characteristics of the parents at the time of attendance. All these could have been useful in explaining the achievement gap due to the age of ECEC entry and, therefore, present a potential source of selection bias.

Stata do-files with which our analyses can be replicated are available online (Laaninen et al. Citation2024).

The association between ECEC enrollment age and literacy scores at the age of 15

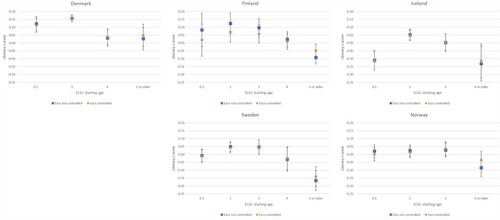

shows the literacy scores at different ECEC enrollment ages with and without adjusting the ESCS. In these models, we (1) regressed ECEC starting age on literacy score and (2) regressed ECEC starting age and ESCS index on literacy score. Both of our models controlled for gender, immigrant status, home language, and age in months. Regression tables are shown in Table A2 in the appendix. Generally, we found that those students who started ECEC from ages one to two and three appear to have higher literacy scores than children who started at up to the age of one and those who started ECEC at four or later. When adjusting for the ESCS, the score differences between the different enrollment groups narrow subtly. This is unsurprising, as family background is associated with both ECEC starting age and academic achievement.

Figure 1. Literacy scores net of demographic controls with and without adjusting for ESCS by starting age in ECEC. Prediction from the OLS models with multiply imputed data, demographic controls, and school fixed effects and 95% CI.

There were some differences between countries regarding which ECEC starting age appears most beneficial. In Denmark, ECEC refers to the ‘børnehave’, which typically starts at the age of three. Most Danes also participate in the ‘vuggestue’ from birth to age two. In Denmark, those who started børnehave at the age of three – the common enrollment age – achieve the highest literacy scores compared to all other groups. ECEC that typically began at the following ages seemed more beneficial for children’s literacy scores than ECEC that began at the age of one: age three in Norway, age two in Finland and Iceland, and ages two to three in Sweden. However, for some countries, these differences were not statistically significant (e.g. Finland and Norway). Compared to other countries, those who started ECEC at birth to age one do particularly poorly in literacy tests in Iceland. This may be because ECEC usually starts at the age of 18 months at the earliest in Iceland, although an earlier start is often offered to children with a delay in their development (Multicultural Information Centre Citation2022).

Our expectation that the association of an early start with literacy scores would be visible in all countries with high-quality childcare was partially met (H1a). Starting ECEC at two or three years old was associated with higher literacy scores compared to starting below the age of one and above the age of four. Furthermore, we expected that the positive association between an early start and literacy scores would depend on the specific country arrangements regarding ECEC and family policies. We assumed that the positive relationship was highest in Denmark and Sweden and would be weakest in Finland and Norway (H1b). A direct comparison of country differences does not fully clarify the matter. However, we compared the enrollment age with the highest literacy score, which, as noted earlier, varies by country, to those in the last starting age category with the lowest literacy score; the difference between these groups is 0.12 SD in Denmark, 0.12 SD in Finland, 0.16 SD in Iceland, 0.05 SD in Norway and 0.19 SD in Sweden (calculated from the ESCS-adjusted model in Table A2).

The differences by ECEC starting age seem the largest in Sweden, but the difference is at the same level in Denmark as in Finland. In Iceland, the difference is the second largest between our countries. Some countries show the highest positive scores for children aged two and three (e.g. Denmark, Sweden, and Iceland), while in other countries, the major difference is between starting below and above the age of four (e.g. Finland and Norway).

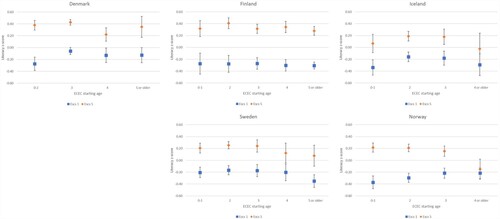

The previous analysis that considers the overall association of ECEC enrollment and literacy score is problematic as the family background precedes the ECEC starting age and is strongly linked to academic achievement. Because of this, in the second part of our analyses, we looked for the presence of heterogeneous effects: is it possible that the association of an early ECEC start with literacy scores is more visible for the group of low-SES children? presents literacy scores for high- and low-SES children for different ECEC starting ages. Regression tables are in Table A3 in the appendix. Surprisingly, there are no clear signs of compensation in literacy scores when low-SES students attend ECEC early.

Figure 2. Literacy scores of high and low ESCS children by starting age in ECEC. Prediction from the OLS models with demographic controls, multiply imputed data, school-fixed effects, and a 95% CI.

In Finland, Iceland, and Sweden, children received a somewhat similar literacy score regardless of the starting age in ECEC in both the high- and low-SES groups; nonetheless, the gap between the two groups is visible and rather stable, with high-SES children scoring substantially better. In Denmark, the gap between high- and low-SES students seems to be larger among those who started ECEC at birth to age two compared to those who started ECEC at the age of five or later (). However, these differences are not statistically significant (Table A4). Moreover, among low-SES children in Denmark, those who start børnehave at the age of three achieve better literacy scores than those who start between age 0–2. The difference between ages two and three for high-SES children is smaller, but the gap between high- and low-SES children for a start at ages 0–2 is highest in comparison to all other periods. This result might reflect some selection among those early starters who are highly disadvantaged: only children from very disadvantaged families are forced into early childcare, and they might be a particularly selected group. Similarly, in Iceland, those who started ECEC at the age of two achieve better literacy scores than those who start at the age of zero to one among the low-SES children. As we discussed previously, this might reflect that stating ECEC before age two is more common with children with delays in their development, especially among low-SES students.

In Norway, the gap between high- and low-SES students is highest among those who started ECEC earlier (at one and two years old), and it becomes comparatively smaller for the other age groups. Those who started ECEC at 0–1 or two years of age achieve scores that are 0.36 SD better than those who started ECEC at the age of four or later among the high-SES students. In addition, those who started ECEC at the age of three attain scores that are 0.31 SD higher than those who started ECEC at the age of four or later among the high-SES students. However, these corresponding differences are only 0.15 SD (0–1 vs. four or later), 0.08 SD (two vs. four or later), and 0.08 SD (three vs. four or later) among low-SES students. The differences between high- and low-SES students in Norway are statistically significant (Table A4).

We run two-way interaction models between country and starting age and three-way interaction models between country, starting age, and ESCS category to test the statistical significance of our country comparison. Table A5 shows that the association between starting age and literacy is stronger in Sweden than in Iceland and Norway. Furthermore, the three-way interaction models show that the difference between Sweden and Norway concerning starting age and ESCS is statistically significant. Regarding Denmark, we can see that the association between starting age and literacy is stronger in Denmark than in Iceland. However, the difference between Denmark and Norway in starting age and ESCS is not statistically significant.

This analysis mainly contradicts our compensation hypothesis (H2a) and is in line with the presence of the Matthew effect in Norway. In Finland and Sweden, the high-SES students have a better literacy score than the low-SES students, which is independent of the age of entry into ECEC. However, especially in Iceland and Denmark, the proportion of those who started ECEC late is small when comparing high- and low-SES groups, which weakens the precision of the estimates.

Robustness of the results

Finally, we conducted additional analyses to evaluate the robustness of our results. As shown in , the confidence intervals are large, especially for those who started early childhood education late. Table A6 shows the number of students who started ECEC at different times according to ESCS categories. The group sizes are especially small in Iceland, so the results for this country should be treated with caution.

Furthermore, we conducted our analyses with all plausible values using Stata's Repest package (Tables A7 and A8). These results do not differ in terms of content from our results in Tables A2 and A3. In addition, we run the regression models replacing ESCS with a ready-made Hisei variable, which is a component of ESCS and measures parents’ highest occupational status. These results in Figure A1 do not differ much from our original results in .

However, these analyses still need to be interpreted with caution due to data limitations, including measurement of ECEC starting age and parental SES. Both variables contain a subjective component: The data on ECEC starting age obtained from students at the age of 15 may suffer from recall bias or memory limitations, and relying on self-reported data from students for SES may introduce measurement errors and biases. The subjective nature of these variables may affect their accuracy and reliability. However, based on , we do not assume that the answers regarding ECEC starting age are completely random. Furthermore, the variable ESCS includes three components of SES that mitigate the effect of possible measurement errors on SES.

Discussion

The initial premise of this article was based on the premise that ECEC is beneficial for the development and educational outcomes of children, particularly for those who are disadvantaged (Burger Citation2010; Reynolds et al. Citation2011). However, this concept has mainly been established in studies with randomized trials targeting disadvantaged children, the results of which cannot be directly generalized to universal ECEC systems. Thus, it cannot be explicitly deducted from these types of studies how publicly funded and universal ECEC affects both advantaged and disadvantaged children (Baker Citation2011). However, the benefit of ECEC has also been observed in universal settings, especially when looking at shorter-run outcomes (e.g. Dearing et al. Citation2018; Drange and Havnes, Citation2018), but results considering longer-run cognitive outcomes are partly mixed (Dumas and Lefranc Citation2012; Felfe et al. Citation2015; Havnes and Mogstad Citation2015; Cornelissen and Dustmann Citation2019). This is one of the few studies that looks at the association between the ECEC starting age and long-term educational outcomes for the general population of students while focusing on countries with universal and high-quality ECEC. Moreover, the study is one of the rare comparative cross-country analyses. The cross-national data allowed us to compare how different contexts regarding ECEC are, on average, associated with potential benefits, offering a new perspective on national results.

Our primary hypothesis was that the association between an early start in ECEC and literacy scores would be positive and lead to compensation in literacy scores for disadvantaged low-SES children. The article develops a qualitative comparison of countries based on the description of ECEC systems found in the literature. Based on this, we expected Denmark and Sweden – forerunners in quality and availability of ECEC – to be prominent among countries in this comparison.

According to the results, literacy scores of students who started ECEC below the age of three are higher than those who started at the age of four or above. Starting at two or three years old is also often associated with higher scores than those starting before age one. The results, therefore, met our assumptions only partially, as the relationship is rather non-linear. In addition, our assumption that the association between ECEC and literacy scores would be stronger in Denmark and Sweden than in Finland and Norway received partial support, as the association was strongest in Sweden and weakest in Norway; however, it was on the same level in Denmark and Finland. Studies using data from large-scale international assessments have been rather inconclusive about the role of ECEC for cognitive achievement and have not found a consistent benefit (Hogrebe and Strietholt Citation2016; Strietholt et al. Citation2020). Our study confirms the US-based results that Loeb et al. (Citation2007) found regarding participation in ECEC at the ages of two and three being the most positively associated with literacy, which casts some doubt on the benefits of a very early and very late start to ECEC, even in universalistic Nordic systems. Nevertheless, the two countries, Sweden and Norway, do not show a significant difference between starting at ages one to three, and the major difference seems to be below and above the age of four. It is important to investigate specific quality features in these countries further to achieve a better understanding of the relationship of ECEC with a plethora of outcomes for younger and older children.

Because the examination of the average association may mask the differences between children from different backgrounds, we next examined the ECEC associations for literacy scores in the high- and low-SES quintiles. Contrary to our assumptions and previous research (Dumas and Lefranc Citation2012; Felfe et al. Citation2015; Datta-Gupta and Simonsen Citation2016; Dämmrich and Esping-Andersen, Citation2017; Dearing et al. Citation2018; Drange and Havnes Citation2018), we did not find that ECEC would compensate for low SES in children’s achievement. In all the countries, the gap between low- and high-SES children was considerable and relatively stable, suggesting that the association of ECEC with literacy scores is mainly driven by family background. This is particularly apparent in the case of Finland and Sweden. In contrast, the Matthew effect in achievement – high-SES children accumulate advantage due to ECEC – was observed in Norway, where the literacy scores of children from affluent families seem more associated with an early ECEC start than disadvantaged children.

This could mean that the gene-environment interaction, as well as the careful selection of ECEC institutions that are usually found in high-SES families, might be driving these gaps even in systems with high-quality universal education. Conforming to this argument, literature shows that in Norway, for example, there is segregation as regards participation in ECEC, with high-SES children participating in ECEC of a higher quality (Drange and Telle Citation2020). This lends credence to the interpretation that the Mathew effect observed in our data for Norway may also be due to selection. As an alternative explanation to the previous one, we allow for the possibility that SES differences are higher for earlier starting ages because selection patterns by family background may be stronger in these age groups than in older children. Furthermore, given the substantial time gap between entry into ECEC and PISA tests, it is likely that gaps are maintained throughout primary and secondary school: high-SES children are more likely to enter more prestigious primary and secondary schools, which can further contribute to and maintain the advantage. Related to this, high-SES students may rely on compensatory advantage mechanisms: high-SES parents can compensate for the low cognitive achievement of their children throughout their schooling by neutralizing any potential early gaps (Bernardi Citation2014; Heiskala et al. Citation2021). Therefore, the difference in the findings between our study and those looking at cognitive achievement at an early age – which find compensation among low-SES children due to preschool – might be due to ECEC's potential compensatory benefits diminishing after elementary school. For instance, previous studies in Norway looking at language and math skills at the age of three and seven (Dearing et al. Citation2018; Drange and Havnes Citation2018) have overlooked the later years, but a recent study on Norway (Sandsør et al. Citation2023) on primary and secondary school children indeed shows widening achievement gaps by parental background over time.

Overall, children from higher-SES families do better in school than children from low-SES families (Bol et al. Citation2014; Chmielewski Citation2019). Furthermore, a similar Matthew effect is sometimes found in cases of other educational outcomes, even in highly egalitarian educational contexts (regarding university education in Finland, see Heiskala et al. Citation2021). However, the potential presence of the Matthew effect in the context of ECEC is rather a new finding. Further research on other countries is needed to illustrate its relevance in other contexts. Notably, the Matthew effect’s presence in a country considered a forerunner in early childhood education and with a strong universal principle of access implies that the advantage of high-SES children may be even greater in countries with non-universal systems. The findings indicate that even when the same rights are provided to all children, low-SES children do not necessarily become less vulnerable. Although these findings require some caution due to the correlational nature of our study, this article provides some indications that even if all children benefit from the provision of high-quality ECEC, this provision does not prevent advantaged families from benefiting the most from those services and securing the best early education for their children.

The results observed in this article may partly emerge from selection issues from unobserved variables. As mentioned previously, this analysis accounts for a limited range of controls, while, over time, the SES status is assumed to be invariant. These are strong assumptions that could affect the size of the disparities observed. Possible unobserved factors could include, for example, parenting practices or child characteristics that correlate with literacy and ECEC starting age, such as developmental disorders or non-cognitive characteristics of children.

Finally, the evidence we provide suggests that, in most countries belonging to the Nordic education model, an early start in good quality education – particularly at the ages of two or three – may be related to higher cognitive achievements. However, it is not necessarily a panacea for leveraging the differences between children from different family backgrounds. In this light, public effort needs to be of a broad spectrum to provide an equal educational trajectory for disadvantaged children and would need to include policies that go beyond preschool attendance.

Availability of the data

The data supporting the findings of this study are freely available at https://www.oecd.org/pisa/data/.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (250.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andersson, B.-E. (1989) ‘Effects of public day-care: a longitudinal study’, Child Development 60(4): 857–66. doi:10.2307/1131027.

- Andersson, B.-E. (1992) ‘Effects of day-care on cognitive and socioemotional competence of thirteen-year-old Swedish schoolchildren’, Child Development 63(1): 20–36. doi:10.2307/1130898.

- Augustine, J. M., Cavanagh, S. E. and Crosnoe, R. (2009) ‘Maternal education, early child care and the reproduction of advantage’, Social Forces 88(1): 1–29. doi:10.1353/sof.0.0233.

- Avvisati, F. and Keslair, F. (2014) REPEST: Stata Module to Run Estimations with Weighted Replicate Samples and Plausible Values, Statistical Software Components (S457918), Boston College Department of Economics, https://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s457918.html.

- Baker, M. (2011) ‘Innis lecture: universal early childhood interventions: what is the evidence base?’, Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue Canadienne D’économique 44(4): 1069–105.

- Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Van IJzendoorn, M. H. and Bradley, R. H. (2005) ‘Those who have, receive: The Matthew effect in early childhood intervention in the home environment’, Review of Educational Research 75(1): 1–26. doi:10.3102/00346543075001001.

- Becker, G. S. (1962) ‘Investment in human capital: a theoretical analysis’, Journal of Political Economy 70(5, Part 2): 9–49.

- Bernardi, F. (2014) ‘Compensatory advantage as a mechanism of educational inequality: a regression discontinuity based on month of birth’, Sociology of Education 87(2): 74–88. doi:10.1177/0038040714524258.

- Bol, T., Witschge, J., Van de Werfhorst, H. G. and Dronkers, J. (2014) ‘Curricular tracking and central examinations: counterbalancing the impact of social background on student achievement in 36 countries’, Social Forces 92(4): 1545–72. doi:10.1093/sf/sou003.

- Bradbury, B., Corak, M., Waldfogel, J. and Washbrook, E. (2015) Too Many Children Left Behind: The US Achievement Gap in Comparative Perspective, New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Burger, K. (2010) ‘How does early childhood care and education affect cognitive development? An international review of the effects of early interventions for children from different social backgrounds’, Early Childhood Research Quarterly 25(2): 140–65. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2009.11.001.

- Camilli, G., Vargas, S., Ryan, S. and Barnett, W. S. (2010) ‘Meta-analysis of the effects of early education interventions on cognitive and social development’, Teachers College Record 112(3): 579–620. doi:10.1177/016146811011200303.

- Cebolla-Boado, H., Radl, J. and Salazar, L. (2016) ‘Preschool education as the great equalizer? A cross-country study into the sources of inequality in reading competence’, Acta Sociologica 60(1): 41–60. doi:10.1177/0001699316654529.

- Chmielewski, A. K. (2019) ‘The global increase in the socioeconomic achievement gap, 1964 to 2015’, American Sociological Review 84(3): 517–44. doi:10.1177/0003122419847165.

- Cornelissen, T. and Dustmann, C. (2019) ‘Early school exposure, test scores, and noncognitive outcomes’, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 11(2): 35–63. doi:10.1257/pol.20170641.

- Cornelissen, T., Dustmann, C., Raute, A. and Schönberg, U. (2018) ‘Who benefits from universal child care? Estimating marginal returns to early child care attendance’, Journal of Political Economy 126(6): 2356–409. doi:10.1086/699979.

- Daly, M. (2020) ‘Conceptualizing and analyzing family policy and how it is changing’, in R. Nieuwenhuis, and W. Van Lancker (eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Family Policy, London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 25–41.

- Dämmrich, J. and Esping-Andersen, G. (2017) ‘Preschool and reading competencies–a cross-national analysis’, in H.-P. Blossfeld, N. Kulic, J. Skopek and M. Triventi (eds.), Childcare, Early Education and Social Inequality, Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 133–151.

- Datta Gupta, N. and and Simonsen, M. (2016) ‘Academic performance and type of early childhood care’, Economics of Education Review 53: 217–29. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2016.03.013.

- Dearing, E., Zachrisson, H. D., Mykletun, A. and Toppelberg, C. O. (2018) ‘Estimating the consequences of Norway’s national scale-up of early childhood education and care (beginning in infancy) for early language skills’, AERA Open 4: 1. doi:10.1177/2332858418756598.

- Dietrichson, J., Lykke Kristiansen, I. and Viinholt, B. A. (2020) ‘Universal preschool programs and long-term child outcomes: a systematic review’, Journal of Economic Surveys 34(5): 1007–43. doi:10.1111/joes.12382.

- Drange, N. and Havnes, T. (2018) ‘Early childcare and cognitive development: evidence from an assignment lottery’, Journal of Labor Economics 37(2): 581–620. doi:10.1086/700193.

- Drange, N. and Telle, K. (2020) ‘Segregation in a universal child care system: descriptive findings from Norway’, European Sociological Review 36(6): 886–901. doi:10.1093/esr/jcaa026.

- Dumas, C. and Lefranc, A. (2012) ‘Early schooling and later outcomes’, in J. Ermisch, M. Jäntti and T. Smeeding (eds.), From Parents to Children: The Intergenerational Transmission of Advantage, New York: Russell Sage Foundation, pp. 164–89, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.77589781610447805.11.

- Ellingsæter, A. L. (2012) Cash for Childcare: Experiences from Finland, Norway and Sweden, Berlin: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1999) Social Foundations of Postindustrial Economies, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Esping-Andersen, G. (2008) ‘Childhood investments and skill formation’, International Tax and Public Finance 15(1): 19–44. doi:10.1007/s10797-007-9033-0.

- Esping-Andersen, G., Garfinkel, I., Han, W.-J., Magnuson, K., Wagner, S. and Waldfogel, J. (2012) ‘Child care and school performance in Denmark and the United States’, Children and Youth Services Review 34(3): 576–89. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.10.010.

- European Commission (2009) Early Childhood Education and Care in Europe: Tackling Social and Cultural Inequalities, ed. by Barle Lakota, Brussels: Publications Office.

- European Commission (2013) Barcelona Objectives: The Development of Childcare Facilities for Young Children in Europe with a View to Sustainable and Inclusive Growth, Publications Office. doi:10.2838/43161.

- European Commission (2015) Key Data on Early Childhood Education and Care in Europe: Eurydice and Eurostat Report: 2014 Edition, Brussels: Publications Office.

- European Commission (2019) Key Data on Early Childhood Education and Care in Europe – 2019 Edition. Eurydice Report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Felfe, C., Nollenberger, N. and Rodríguez-Planas, N. (2015) ‘Can’t buy mommy’s love? Universal childcare and children’s long-term cognitive development’, Journal of Population Economics 28: 393–422. doi:10.1007/s00148-014-0532-x.

- Gambaro, L., Stewart, K. and Waldfogel, J. (2014) An Equal Start?: Providing Quality Early Education and Care for Disadvantaged Children, Bristol: Policy Press.

- Giuliani, G. and Duvander, A. Z. (2017) ‘Cash-for-care policy in Sweden: an appraisal of its consequences on female employment’, International Journal of Social Welfare 26(1): 49–62. doi:10.1111/ijsw.12229.

- Han, W. J., Waldfogel, J. and Brooks-Gunn, J. (2001) ‘The effects of early maternal employment on later cognitive and behavioral outcomes’, Journal of Marriage and Family 63(2): 336–54. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00336.x.

- Havnes, T. and Mogstad, M. (2015) ‘Is universal child care leveling the playing field?’, Journal of Public Economics 127: 100–14. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0047272714000899.

- Heath, A. F., Rothon, C. and Kilpi, E. (2008) ‘The second generation in Western Europe: education, unemployment, and occupational attainment’, Annual Review of Sociology 34(1): 211–35. http://10.122annurev.soc.34.040507.134728.

- Heckman, J. (2000) ‘Policies to foster human capital’, Research in Economics 54(1): 3–56. doi:10.1006/reec.1999.0225.

- Heckman, J. (2006) ‘Skill formation and the economics of investing in disadvantaged children’, Science 312(5782): 1900–2. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1128898.

- Heckman, J. (2012) Invest in Early Childhood Development: Reduce Deficits, Strengthen the Economy. Available from: https://heckmanequation.org/resource/invest-in-early-childhood-development-reduce-deficits-strengthen-the-economy/ [Accessed 28 Feb 2022].

- Heckman, J. and Masterov, D. (2007) ‘The productivity argument for investing in young children’, Review of Agricultural Economics 29(3): 446–93. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/aepp/article-lookup/doi/10.1111j.1467-9353.2007.00359.x [Accessed 28 Jan 2022].

- Heiskala, L., Erola, J. and Kilpi-Jakonen, E. (2021) ‘Compensatory and multiplicative advantages: social origin, school performance, and stratified higher education enrolment in Finland’, European Sociological Review 37(2): 171–85. doi:10.1093/esr/jcaa046.

- Hogrebe, N. and Strietholt, R. (2016) ‘Does non-participation in preschool affect children’s reading achievement? International evidence from propensity score analyses’, Large-scale Assessments in Education 4(2): 1–22.

- Jerrim, J., Lopez-Agudo, L. A., Marcenaro-Gutierrez, O. D. and Shure, N. (2017) ‘To weight or not to weight?: The case of PISA data’, paper presented at the Proceedings of the XXVI Meeting of the Economics of Education Association, Murcia, Spain, June 29–30.

- Karhula, A., Erola, J. and Kilpi-Jakonen, E. (2017) ‘Home sweet home? Long-term educational outcomes of childcare arrangements in Finland’, in H.-P. Blossfeld, N. Kulic, J. Skopek and M. Triventi (eds.), Childcare, Early Education and Social Inequality, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 268–284.

- Kosonen, T. and Huttunen, K. (2018) Kotihoidontuen Vaikutus Lapsiin, Palkansaajien tutkimuslaitos: Helsinki.

- Kuehnle, D. and Oberfichtner, M. (2020) ‘Does starting universal childcare earlier influence children’s skill development?’, Demography 57(1): 61–98. doi:10.1007/s13524-019-00836-9.

- Kulic, N., Skopek, J., Triventi, M. and Blossfeld, H.-P. (2017) ‘Childcare, early education, and social inequality: perspectives for a cross-national and multidisciplinary study’, in H.-P. Blossfeld, N. Kulic, J. Skopek and M. Triventi (eds.), Childcare, Early Education and Social Inequality, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 3–28.

- Kulic, N., Skopek, J., Triventi, M. and Blossfeld, H.-P. (2019) ‘Social background and children’s cognitive skills: the role of early childhood education and care in a cross-national perspective’, Annual Review of Sociology 45: 557–79. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-073018-022401.

- Laaninen, M., Kulic, N. and Erola, J. (2024) Code repository for: Age of entry into early childhood education and care, literacy and reduction of educational inequality in Nordic countries. Zenodo. https://zenodo.org/records/10489644.

- Lareau, A. (2003) Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life, Berkeley:University of California Press.

- Loeb, S., Bridges, M., Bassok, D., Fuller, B. and Randumberger, R. W. (2007) ‘How much is too much? The influence of preschool centers on children's social and cognitive development’, Economics of Education Review 26(1): 52–66. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2005.11.005.

- Magnuson, K. A., Meyers, M. K. and Waldfogel, J. (2007) ‘Public funding and enrollment in formal child care in the 1990s’, Social Service Review 81(1): 47–83. doi:10.1086/511628.

- Magnuson, K. and Shager, H. (2010) ‘Early education: progress and promise for children from low-income families’, Children and Youth Services Review 32(9): 1186–98. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.03.006.

- McCoy, D. C., Yoshikawa, H., Ziol-Guest, K. M., Duncan, G. J., Schindler, H. S., Magnuson, K., Yang, R., Koepp, A. and Shonkoff, J. P. (2017) ‘Impacts of early childhood education on medium-and long-term educational outcomes’, Educational Researcher 46(8): 474–87. doi:10.3102/0013189X17737739.

- Melhuish, E., Ereky-Stevens, K., Petrogiannis, K., Ariescu, A., Penderi, E., Rentzou, K., Tawell, A., Slot, P. L., Broekhuizen, M. and Leseman, P. (2015) A Review of Research on the Effects of Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) upon Child Development. EU CARE project.

- Multicultural Information Centre (2022) Multicultural Information Centre. Available from: https://www.mcc.is/education/pre-compulsary-schools/ [Accessed 17 May 2022].

- Nennstiel, R. (2022) ‘No Matthew effects and stable SES gaps in math and language achievement growth throughout schooling: evidence from Germany’, European Sociological Review 39(5): 724–40. doi:10.1093/esr/jcac062.

- The Nordic Council and the Nordic Council of Ministers (n.d.) Info Norden. Available from: https://www.norden.org/en/info-norden [Accessed 31 Jan 2022].

- Nores, M. and Barnett, W. S. (2010) ‘Benefits of early childhood interventions across the world: (under) investing in the very young’, Economics of Education Review 29(2): 271–82. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2009.09.001.

- OECD (2006) Starting Strong II: Early Childhood Education and Care, Paris: OECD Publishing.

- OECD (2017) PISA 2015 Technical Report, Paris: OECD Publishing.

- OECD (2022a) Public Policies for Families and Children - Public Spending on Childcare and Early Education. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm [Accessed 31 Jan 2022].

- OECD (2022b) How to Prepare and Analyse the PISA Database. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/pisa/data/httpoecdorgpisadatabase-instructions.htm [Accessed 31 Jan 2022].

- OECD (2023) How to Prepare and Analyse the PISA database, < > [10 November 2023].

- Pavolini, E. and Van Lancker, W. (2018) ‘The Matthew effect in childcare use: a matter of policies or preferences?’, Journal of European Public Policy 25(6): 878–93. doi:10.1080/13501763.2017.1401108.

- Reynolds, A. J., Temple, J. A., Ou, S.-R., Arteaga, I. A. and White, B. A. B. (2011) ‘School-based early childhood education and age-28 well-being: effects by timing, dosage, and subgroups’, Science 333(6040): 360–4. doi:10.1126/science.1203618.

- Rigney, D. (2010) The Matthew Effect: How Advantage Begets Further Advantage, New York: Columbia University Press.

- Säkkinen, S. and Kuoppala, T. (2016) Varhaiskasvatus 2015, Helsinki: Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos.

- Sandsør, A. M. J., Zachrisson, H. D., Karoly, L. A. and Dearing, E. (2023) ‘The widening achievement gap between rich and poor in a nordic country’, Educational Researcher 52(4): 195–205. doi:10.3102/0013189X221142596.

- Shonkoff, J. and Phillips, D. (2000) From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development, Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences.

- Skogland, H. (2018) Iceland Country Profile 2018: Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC), Kópavogi: Directorate of Education.

- Statistics Iceland (2023a) Children in Pre-primary Institutions by Age of Children and Daily Attendance 1998–2022. Available from: https://px.hagstofa.is/pxen/pxweb/en/Samfelag/Samfelag__skolamal__1_leikskolastig__0_lsNemendur/SKO01001.px/ [Accessed 30 June 2023].

- Statistics Iceland (2023b) Personnel in Pre-primary Institutions by Education 1998–2021. Available from: https://px.hagstofa.is/pxen/pxweb/en/Samfelag/Samfelag__skolamal__1_leikskolastig__1_lsStarfsfolk/SKO01303.px/ [Accessed 30 June 2023].

- Statistics Iceland (2023c) Personnel in Pre-primary Institutions by Education 1998–2021. Available from: https://px.hagstofa.is/pxen/pxweb/en/Samfelag/Samfelag__skolamal__1_leikskolastig__1_lsStarfsfolk/SKO01303.px/ [Accessed 30 June 2023].

- Strietholt, R., Hogrebe, N. and Zachrisson, H. D. (2020) ‘Do increases in national-level preschool enrollment increase student achievement? Evidence from international assessments’, International Journal of Educational Development 79: 102287. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2020.102287.

- Thévenon, O. (2011) ‘Family policies in OECD countries: a comparative analysis’, Population and Development Review 37(1): 57–87. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2011.00390.x.

- Tucker-Drob, E. M. and Harden, K. P. (2012) ‘Learning motivation mediates gene-by-socioeconomic status interaction on mathematics achievement in early childhood’, Learning and Individual Differences 22(1): 37–45. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2011.11.015.

- van Huizen, T. and Plantenga, J. (2018) ‘Do children benefit from universal early childhood education and care? A meta-analysis of evidence from natural experiments’, Economics of Education Review 66: 206–22. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2018.08.001.

- Wood, J., Neels, K. and Maes, J. (2023) ‘A closer look at demand-side explanations for the Matthew effect in formal childcare uptake in Europe and Australia’, Journal of European Social Policy 33(4): 451–68. doi:10.1177/09589287231186068.

- World Bank (2023) Early Childhood Development. Available from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/earlychildhooddevelopment [Accessed 8 Aug 2023].