ABSTRACT

UK young adults saw sharp mental health declines during the COVID-19 pandemic. This paper examines whether living with siblings helped moderate this negative effect. We compare the outcomes of young adults (age 19), i) who were living with parents and siblings, with ii) those who were living with only parents, and iii) with those who were living away from parents. We used data from the Millennium Cohort Study COVID-19 survey, linked with the mainstage survey (N = 2,578), and captured mental health with: the Shortened Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale and the Kessler-6 Psychological Distress scale. As young men and women may be differently affected by sibling co-residence, we vary living arrangements effects by gender. While average young adult mental health deteriorated during the first national lockdown, there were variations by gender and living arrangements. For young men, living with siblings was associated with improved mental health on both measures during the first COVID-19 lockdown. For young women, living with parents was associated with lower psychological distress than living away from home, but siblings provided no additional benefit. Data from later in the pandemic suggests that, as young adults became more accustomed to social restrictions, the importance of family living arrangements declined.

Introduction

The UK experienced its first national COVID-19 related lockdown between late March and June 2020, with people ordered to stay at home and only leave for essential purposes, such as buying food. Schools and universities were temporarily shut down; for those employed in non-essential occupations, jobs were suspended, and workers furloughed or moved online. For the population, this period can be characterized as a time of acute distress, loss of control, and uncertainty, as fear of the disease, alongside stay-at-home orders, and extreme limits on public gatherings, curtailed daily life.

Despite being at low-risk of mortality from infection (Kung et al. Citation2023) young adults experienced significant deteriorations in their mental health during the first lockdown as the normal social, educational, and occupational milestones associated with the transition to adulthood were disrupted (Shanahan et al. Citation2020). Responding to the large-scale disruptions, many young adults, who had previously left the family home, returned (Evandrou et al. Citation2021; Hall and Zygmunt Citation2021), while those with plans to leave remained (Luppi et al. Citation2021). Living with parents during lockdown may have protected against loneliness and the economic strains of lockdown restrictions (Kung et al. Citation2023; Park et al. Citation2019; Wu and Grundy Citation2023). Moreover, the presence of siblings, because of their more peer-like role in the household, may have provided young adults with additional emotional support (Harper et al. Citation2016). Yet, despite the potential importance of siblings for young adult mental health (Thomas et al. Citation2017), and the likely heightened significance of siblings for mental health during periods of crisis (Milevsky et al. Citation2005; Van Volkom Citation2006), few studies have considered how young adult mental health was affected by living with siblings during the pandemic. We contrast the effect of family living arrangements on young adult mental health during the first COVID-19 lockdown, in May 2020, with those experienced during later stages of the pandemic, in Autumn 2020 and Spring 2021, as restrictions, and young adult adherence to them, eased (Aksoy Citation2022; Wright et al. Citation2022).

The COVID-19 pandemic provides a unique opportunity to study the association of co-residing with parents and siblings on young adult mental health during periods of stress. We build upon previous studies to explore how living with parents and siblings affected young adult mental health. As gender may influence the nature of familial relationships and response to social support (Batz and Tay Citation2018; McHale et al. Citation2003), we also investigate whether the effect of living arrangements on young adults’ mental health vary by gender. We use ‘mental health’ to broadly mean both the presence of positive emotional, psychological, and social functioning, as well as the absence of distress, worry, depression, and anxiety (Westerhof and Keyes Citation2010). In accordance, we report measures for two dimensions of mental health: mental well-being and psychological distress using, respectively, the Shortened Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS) and the Kessler-6 question Psychological Distress scale (K6).

Literature review

Living at home and young adult mental health

Although the transition to adulthood in Western countries has become longer, more complex, and less defined by age norms (Shanahan Citation2000), residential independence remains an important social milestone (Her et al. Citation2022; Stone et al. Citation2014). For young adults living with their parents, ‘failure to launch’, or returning home after leaving (‘boomerang kids’), can be negatively perceived as a drain on parental resources, especially in societies like the UK, where achievement and self-sufficiency are valued (Beck and Beck-Gernsheim Citation2002; Kins and Beyers Citation2010). While young adults’ life courses have become less standardized (e.g. Elzinga and Liefbroer Citation2007; Spéder et al. Citation2014), the negative normative associations that persist around parental co-residence may harm the mental health of young adults who live with their parents (Copp et al. Citation2017).

Pre-pandemic evidence shows mixed effects of young adult and parent co-residence on young adult mental health. Children, who had not yet moved out, appear to experience no adverse mental health effects; while evidence on those who ‘boomerang’ home has suggested their mental health deteriorates (Copp et al. Citation2017; Sandberg-Thoma et al. Citation2015), shows no changes (Preetz et al. Citation2021), or even improves (Wu and Grundy Citation2023). These mixed results may be explained by the fact that adult children often return to the parental home in response to stressful life events and individual crises, such as unemployment, mental illness, relationship breakdown, or educational disruptions (Sandberg-Thoma et al. Citation2015; Tosi and Grundy Citation2018). In times of crisis, returning to live with parents can offer an important safety net, protecting against the instability of young adult life (Park et al. Citation2019; Sage et al. Citation2013; Wu and Grundy Citation2023). Yet, because parental support is provided in response to children’s individual needs (Park et al. Citation2019), identifying the effect of family living arrangements on young adult mental health is difficult.

Unlike other stressful life events, the first national lockdown was an unexpected shock that affected all young adults (Shanahan et al. Citation2020; Stroud and Gutman Citation2021). As such, it provides a unique opportunity to interrogate how living with parents may protect young adult mental health during a period of widespread distress and uncertainty. We also examine how the relationship between family-living arrangements and mental health changed over the course of the pandemic, as COVID-19-related restrictions waxed and waned. While prior studies have examined how family functioning changed during COVID-19 (Campione-Barr et al. Citation2021; Cassinat et al. Citation2021), few have looked directly at how living arrangements influenced young adult mental health. One exception, Evandrou et al.’s (Citation2021) UK study, looked at how moving home during lockdown affected young adult stress. However, Evandrou et al.’s study did not directly examine the relationship between living arrangements and mental health, nor did they consider the presence of siblings.

Siblings and young adult mental health

Siblings can be important influences on each other’s mental health across the life course (Cicirelli Citation1995). This influence can be direct, through sibling interactions (Jensen et al. Citation2018; Thomas et al. Citation2017), or indirect, through their influence on household dynamics and the parental resources (Jensen et al. Citation2013). As children become young adults, sibling conflict decreases, and siblings can become closer (Conger and Little Citation2010; Jensen et al. Citation2018; White Citation2001). Moreover, siblings report being closer when they share adulthood life events (Cicirelli Citation1995; Conger and Little Citation2010), and throughout adulthood, sibling support remains important, particularly during crises (Milevsky et al. Citation2005; Van Volkom Citation2006).

Living with siblings during the first UK lockdown may have independently protected against isolation and loneliness. Not only were siblings likely to spend more time together during lockdown, given restrictions on social contact, they could have acted as substitutes for close friends and peers, providing an important source of companionship distinct from that offered by parents (Conger and Little Citation2010; Harper et al. Citation2016). Previous studies of sibling relationships during the pandemic have focused on adolescent or teenage children. Using data from a sample of young people aged 12–20 in the US (N = 170), Campione-Barr et al. (Citation2021) found that sibling relationships became more intense during their pandemic observation window. A separate survey of families in the US with two children, ages 10–5 (N = 682 households), found that sibling conflict increased in response to greater family chaos during the pandemic (Cassinat et al. Citation2021). Notably, as well as lacking a focus on mental health, neither study centered young adults, who have reached a life stage characterized by less conflictual and more egalitarian sibling relationships (Conger and Little Citation2010; Jensen et al. Citation2018; White Citation2001).

Among those with siblings, the number of siblings, birth order, gender composition, and childhood sibling conflict may all affect young adult sibling relationships (Van Volkom et al. Citation2017). Having more siblings is traditionally thought to reduce overall household resources and thus increase early-life sibling competition, translating to more conflictual adult sibling relationships (Jensen et al. Citation2018). Yet, the connection between number of siblings and mental health remains unclear (Merry et al. Citation2020). Older siblings may act as supplementary caregivers to younger siblings, receiving less support from sibling relationships than those who are younger (Lawson and Mace Citation2010; Milevsky et al. Citation2005). The gender mix of siblings may also matter, with same-gender siblings reporting closer and more supportive relationships than opposite-gender pairings (Hollifield and Conger Citation2015; Jensen et al. Citation2013). Finally, confrontational childhood sibling relationships, such as by bullying or being bullied by a sibling, are thought to diminish opportunities for positive sibling relationships in adulthood (Jensen et al. Citation2018).

Gendered effects of co-residing with parents and siblings

Evidence from the pandemic suggests that women and girls had worse mental health than men and boys (e.g. Stroud and Gutman Citation2021). Moreover, the association between parent and sibling co-residence and young adult mental health may differ by gender. Gender differences in social roles mean different responsibilities and stressors (Batz and Tay Citation2018), which will moderate how young adults respond to living with family. Young women, who generally assume larger shares of household work than young men (e.g. Schulz Citation2021), may benefit less from living at home. Supporting this idea, research suggests that women leave the family home earlier than men (Sandberg-Thoma et al. Citation2015; Stone et al. Citation2014) and retain fewer positive relationships with parents after leaving home than young men (Tosi Citation2017). While men may experience more comfort from family, women may suffer more when they are without this common social support. In a large sample of Norwegian adults, ages 18-38, Johansen and colleagues (Citation2021) found that women had larger support networks but were more negatively affected when they lacked social support than men. Similarly, Lee and Goldstein (Citation2016) found that young women (aged 18-25) reported suffering more loneliness from lack of support than men. While neither of these studies focused on parents and siblings or young adult living arrangements in their analysis, they do indicate that young women’s mental health may be hurt more than men’s by the absence of social, including familial, support.

Considering the specific role of siblings, Cable et al. (Citation2013) found that, while friendship protects older men and women’s well-being similarly, only men gain comparable support from siblings. Voorpostel and Blieszner (Citation2008) found that adult siblings were more likely to support one another when relationships between parents and children were poor, with this compensatory effect being stronger for brothers than sisters. Given this evidence, and evidence that gender drives how family members interact with each other (Lee and Goldstein Citation2016; McHale et al. Citation2003), we expect to see variations by gender in the association between family living arrangements and young adult mental health during the pandemic. On the one hand, compared to young men, young women’s greater dependence on social support may have meant that living at home moderated poor mental health during the pandemic, although the social roles ascribed to young women may have reduced these gains. Living with siblings may also be less strongly associated with improved mental health support if siblings provide a poor substitute for friends, which may be more likely for women.

Other young adult pandemic stressors

Young adult living arrangements were one of many factors affecting young adults’ mental health during lockdown. Restrictions meant in-person social interactions were suspended, education moved online, and job opportunities disappeared, became virtual, or were furloughed. In the UK, furloughed workers, whose jobs were suspended due to pandemic restrictions, were provided government support at 90% (or higher) normal pay. Many young adults had anxiety about catching and spreading the virus (Shanahan et al. Citation2020). Moreover, resource disadvantages (e.g. overcrowded households, low income households) meant some families had less capacity to cope with the shock of lockdown and the presence of young adults at home (Wright et al. Citation2020). Additionally, parent composition (e.g. whether a young adult has stepparents or single parents), affects the nature of familial relationships and stressors (Kalmijn Citation2013). Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately impacted minority ethnic populations due to structural inequalities (Platt and Warwick Citation2020; Shen and Bartram Citation2021).

Family living arrangements and young adult mental health throughout the pandemic

The UK experienced three national lockdowns over the course of the pandemic. The first lockdown took place between March and June 2020 with a second lockdown following in November 2020, with the third and final lockdown from January to March 2021 (Institute for Government Citation2022). From 8 March 2021, a phased ‘roadmap of lockdown’ saw a phased lifting of restrictions as the country returned to normal life (Brown et al. Citation2021). While restrictions remained in place over the course of the pandemic, there was an adaption to COVID-19 restrictions and a decline in COVID-19 guideline compliance, including social distancing measures, particularly amongst younger people (Aksoy Citation2022; Wright et al. Citation2022). This adaptation to COVID-19 measures is reflected in changes in young peoples’ living arrangements. As has been well documented, in response to the shock of the first lockdown, many young adults returned to the parental home, with parental co-residence providing an important safety net during this period (Evandrou et al. Citation2021; Luppi et al. Citation2021). Yet, as restrictions eased, young adults began to resume pursuing adulthood milestones, including living away from the parental home. As we report later in this paper, the share of young adults living with their parents fell sharply between May and September/October 2020, after the country emerged from its first lockdown. Unlike the first lockdown, the third lockdown, in the first quarter of 2021, was not associated with young adults returning to the family home.Footnote1 The resumption of increasingly normal life leads us to expect the importance of living with parents and siblings to decline over the course of the pandemic. In other words, we expect family living arrangements to be most strongly associated with young adult mental health during the first lockdown.

Study overview

Given the discussion above, we expect co-residence with parents and siblings to protect young adult mental health during the first lockdown. Specifically, living without parents during the lockdown is expected to have been particularly challenging for young women’s mental health. For especially young men, we expect living with siblings to protect mental health. To test these expectations, we compare the outcomes of young adults who were living (i) with parents and siblings; (ii) with parents and no siblings; and (iii) outside the parental home. We use data from the Millennium Cohort Study (MCS) subsample of the Centre for Longitudinal Studies (CLS) COVID-19 survey in three waves: in May 2020, September to October 2020, and February to March 2021 (CLS Citation2021). To account for prior differences in mental health, as well as variations in sibling characteristics, we link CLS COVID-19 data to the MCS mainstage survey. Both the first and third waves of the CLS COVID-19 survey cover periods of national lockdowns. While not in lockdown during the second wave, collected Autumn 2020, restrictions on social gatherings remained in place (Institute for Government Citation2022). Although we present results for each of COVID-19 data collection wave, when controlling for pre-pandemic mental health, we expect the effect of young adults’ living arrangements on mental health to moderate over the course of the pandemic. Therefore, we focus on data collected during the first lockdown before discussing the relationship between family living arrangements and mental health at later stages of the pandemic.

Methods

Data and sample

We used data from the MCS mainstage and the CLS COVID-19 surveys. The MCS mainstage survey is a high quality, longitudinal study representative of a UK cohort born between September 2000 and March 2002, with data collected when the participants were 9 months (Wave 1) and at 3 (Wave 2), 5 (Wave 3), 7 (Wave 4), 11 (Wave 5), 14 (Wave 6), and 17 (Wave 7) years old (CLS Citation2023, Citation2022a, Citation2022b, Citation2022c, Citation2022d, Citation2022e, Citation2022f). The CLS COVID-19 survey drew on a sample of participants from five national longitudinal cohort studies, including a subsample of MCS participants. A majority of MCS respondents to the CLS COVID-19 survey were aged 19Footnote2 at the first wave of data collection, in May 2020 (CLS Citation2021). We linked data from the CLS COVID-19 survey to the MCS mainstage survey to account for pre-pandemic characteristics.

The sampling frame for the CLS COVID-19 survey changed across waves. During Wave 1, the survey team was unable to send mailings, due to lockdown restrictions, so only those for whom an email address was held were invited to participate. From Wave 2, both email and post were used to invite participants to respond to the survey. In Wave 3, participation was further boosted, with those who did not respond to the web survey being invited to participate via telephone. As a result, the number of MCS respondents in the CLS COVID-19 survey grew with each wave (Wave 1: N = 2,640; Wave 2: N = 3,266, and Wave 3: N = 4,464). Data from a total of N = 5,552 MCS cohort members were collected, with N = 1,522 MCS cohort members responding at all three waves (Brown et al. Citation2024).

The following sample restrictions were applied to the 2,640 young adults who responded to the first CLS COVID-19 survey. First, to ensure the inclusion of only one child per family, we excluded twins and triplets as sample members (N = 38), counting them instead as siblings. We then organized our sample members by COVID-19 family living arrangements and found that (N = 24) participants were living with siblings and no parents during the first wave of COVID-19. As these young adults may be affected by their living arrangements differently than the rest of the sample, they were excluded from our analysis. For CLS COVID-19 Wave 1, our final unweighted sample was N = 2578. We applied similar restrictions to waves 2 and 3 of the data, with final sample sizes of N = 3207 and N = 4375 respectively. Last, we applied our sample restrictions, to those who responded to all three waves of the COVID-19 survey, with a final sample of N = 1,471.

In our samples, around 12% of participants did not have valid mental health responses. At CLS COVID-19 Wave 1, those with missing mental health information were more likely to have left the family home (43%) or to be living at home with parents but no siblings (15%). To account for missing mental health information, and as is common in studies using cohort data (Silverwood et al. Citation2021), we used multiple imputation by chained equations with 30 iterations (Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn Citation2011). The number of missing observations in each imputed variable is indicated in the notes of our descriptive tables (i.e. and Table A2).

Table 1. Sample characteristics of young adults (age 19) who participated in the CLS COVID-19 survey Wave 1, during the first COVID-19 lockdown.

Finally, to ensure our estimates are representative, we used survey weights that account for sample structure and attrition between the COVID-19 survey and the original mainstage survey sample (Brown et al. Citation2024). We report unweighted sample sizes and weighted estimates throughout.

Measures

Outcome variables

Our first mental health measure, SWEMWBS (Tennant et al. Citation2007), captures mental well-being, or the ‘optimal social and psychological functioning’ (Kazdin Citation1993, 128). The SWEMWBS measures positive aspects of mental health including optimism, trust in self and others, and social connection (on a scale of 1 = ‘None of the time’ to 5 = ‘All of the time’). The seven questions of the SWEMWBS are added such that scores ranged from 7–35 and transformed with a widely accepted metric conversion factor designed for the scale (Stewart-Brown et al. Citation2009) (Cronbach alpha, α = 0.93). With the SWEMWBS, good mental health, or higher SWEMWBS scores, encapsulates the frequency of positive social and psychological processes, and poor mental health (i.e. low SWEMWBS scores) through the absence of these processes.

In addition to measuring the presence of health, we consider the absence of ill-health. The well-validated K6 measure captures non-specific psychological distress within a healthy population (Kessler et al. Citation2002; Mewton et al. Citation2015). The scale was designed to screen for non-clinical mood disturbance (e.g. depression, anxiety) and heightened worry (Sharp and Theiler Citation2018). The K6 is widely used in sociological and epidemiological studies of young adult mental health (e.g. Sharp and Theiler Citation2018). The K6 asks six questions that capture how often, in the last 30 days, one felt depressed, hopeless, restless or fidgety, everything was an effort, worthless, and nervous (on a scale of 0 = ‘None of the time’ to 4 = ‘All of the time’). These questions are added such that scores ranged from 0 to 24 (Cronbach alpha, α = 0.84), with increasing K6 values indicating higher distress. Opposite to the SWEMWBS and reflecting the separate constructs of psychological distress and mental well-being, the K6 measures good mental health through the absence of negative psychological symptoms, or lower scores.

Explanatory variables

We distinguished between young adults living with their parents and living away from parental homes at each wave of the CLS COVID-19 survey. Those residing with their parents were further categorized by sibling co-residence. The resulting COVID-19 living arrangement categories were: (i) living away from the parental home, (ii) living with parents, no siblings, and (iii) living with parents and siblings.

The CLS COVID-19 survey had limited sibling information: a binary answer to whether the respondent was living with siblings. However, the MCS mainstage survey provides richer information regarding sibling structure and childhood sibling relationship. To examine how sibling factors influenced young adult mental health during lockdown, we included the number of siblings, having a same-gender sibling, being the oldest sibling, and whether the young adult was bullied by their sibling, or themselves bullied their sibling, at least once a week (collected at Wave 6, aged 14Footnote3). Apart from number of siblings (ranging, 0–8), all sibling variables were dichotomous.

Covariates

Changes to living arrangements and household members, rather than living arrangements themselves, may increase stress (Evandrou et al. Citation2021). We controlled for this using the question ‘Have there been any changes to the people you are living with since the Coronavirus outbreak?’ (binary: yes/no, labelled ‘Changes to living arrangements since March 2020’).Footnote4 Unfortunately, it was not possible to distinguish between different types of moves; for example, whether the change was a result of a young adult boomeranging home or others joining the family home (e.g. older siblings or grandparents moving in). Additionally, this question was only asked of participants once, upon their entry to the survey; so, this variable could not be considered a repeated measure (like those available for mental health).

The CLS COVID-19 survey collected information on young adult pandemic economic activity. We included controls for being in university (ref), in education (not university), employed in paid work (including self-employment), on UK pandemic furlough, unemployed, and economically inactive (including all those employed but currently unpaid, those in unpaid work, caregiving, and those who are permanently sick or differently abled). We separated education into university and non-university education because, in the UK, university students may have been more likely to have had their living arrangements disrupted.Footnote5

To account for pandemic-related household strains, we included information on whether the house was overcrowded (defined as more than one person per household room, binary: yes/no), and household relationship quality, defined as increased intra-household conflict during the pandemic (binary: yes/no). We included two further controls, which have been shown to affect mental health during the pandemic (Platt and Warwick Citation2020; Wright et al. Citation2020), in our analysis: COVID-19 infection (binary: yes/no) and whether the participant was non-white (binary: yes/no, collected from the first wave of the mainstage survey). As UK-wide lockdown rules fractured from 11 May 2020, with national restrictions taking their place (Institute for Government Citation2022), we controlled for country policy differences by including dummy variables for living in England, Wales, Scotland, or Northern Ireland.

A major advantage of the MCS subsample in the CLS COVID-19 survey is that we could link the data to pre-pandemic information. This allowed us to condition on pre-pandemic mental health (measured at Wave 7 of the mainstage survey, collected between January 2018 and May 2019, when participants were aged 17). We also constructed controls from Wave 7 for whether the young adult lived in a single-parent household and whether there was a stepparent in the household. We used data from the Wave 6 survey (January 2015 to April 2016, when participants were aged 14), to condition on parental educationFootnote6 (a dummy variable for whether at least one parent had reported an above high school education) and whether the young person had lived in a low-income household (defined as being in the bottom UK equivalized income quintile). Like our outcome measures, the less than 5% of cases with missing responses for these controls were filled using multiple imputation of chained equations (Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn Citation2011; Silverwood et al. Citation2021).

Analytic strategy

We estimated non-dynamic longitudinal models that control for prior mental health, measured at age 17. Such models are commonly used in studies drawing on cohort data that are interested in outcomes at a single point in time (e.g. Gyani et al. Citation2013; Harkness et al. Citation2020; Silverwood et al. Citation2021). We carry out our analysis in three parts. First, we investigated the associations between family living arrangements during the first lockdown and young adult mental health. We estimated three models: (a) the first includes our main explanatory factors of young adult family living arrangements interacted with gender; (b) the second adds controls for changes in living arrangements since March 2020, young adult COVID-19 economic activity, and childhood family characteristics, and (c) the third adds a control for increased household conflict during COVID-19, which has previously been shown to mediate the effect of living arrangements on mental health (Evandrou et al. Citation2021). Secondarily, we considered only young adults who have siblings, examining the relationship between mental health during the first lockdown and sibling characteristics. We estimated a baseline model with controls for living arrangements and gender; then, we add sibling characteristic controls (i.e. gender composition, being the oldest sibling, and the quality of sibling relationships observed earlier in childhood); and then we add all remaining controls. The third and final part of our analysis considered how young adult co-residence with siblings moderated mental health over the course of the pandemic, running a model with all available controls on the first, second and third waves of the CLS COVID-19 survey.Footnote7

We also tested the sensitivity of our results. First, to confirm that effects for each of the three waves of the data are robust against cross-wave sample differences, we considered our tertiary analysis on a sample limited to those observed in all three waves. Second, we estimated fixed effect (FE) models to control for time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity more conservatively. FE models are frequently used to examine changes over time (e.g. wage growth) and may help eliminate some sources of potential bias. However, they also come with several limitations. On the one hand, the FE specification may ‘wash out’ family characteristics that show little variation over time (Blanden et al. Citation2002; Miller et al. Citation2023), making recovering parameters on family structure (e.g. sibling characteristics) difficult while limiting external validity (Hill et al. Citation2020; Johnston and DiNardo Citation1997). On the other hand, coefficients are unreliable when longitudinal data covers few time periods (as in the cohort studies) and more likely to suffer from attenuation bias due to measurement error (Angrist and Pischke Citation2009). The limitations of FE models are further compounded by the nature of the MCS sample in the CLS COVID-19, of which, as described above, only 27% of all young adult participants were observed in all three COVID-19 waves. For these reasons, FE models are less well suited to our research question than our non-dynamic longitudinal models. Despite this, because FE models better account for time-invariant heterogeneity, we supplemented our estimates with FE models (Appendix Table A4), where t = 0 is when participants were aged 17 (MCS mainstage survey Wave 7) up t = 3 (CLS COVID-19 survey Wave 3).

All code and instruction for data cleaning and analysis is available at https://zenodo.org/doi/10.5281/zenodo.11204823.

Results

presents descriptive statistics for 2,578 young adults aged 19 at the first wave of the CLS COVID-19 survey, overall and according to gender. In May 2020, only about 15% of the sample had left the parental home, 20% were living with parents and no siblings, and 65% were living with parents and siblings. More than one-in-five (22%) reported changed living arrangements since March 2020. Around 90% of our sample had at least one sibling (step, adopted, foster, half, or full), and 65% of our sample were living with a sibling during the first lockdown. These proportions were similar by gender.

Separately, we investigated the living arrangements of young adults living outside the parental home in slightly more detail. Briefly, almost 25% of young adults were co-habiting with a romantic partner, 27% with a friend, 15% with a grandparent, and 4% were living with a child (categories non-mutually exclusive). Of those living away from parent during the first lockdown, 15% were also not living with their parents at Wave 7 and 35% had changed living arrangements since the beginning of the first lockdown. The household members of those living away from the parental home undoubtedly impact lockdown mental health. In such a way, our sample is limited by having too few participants living alone to properly account for this heterogeneity.

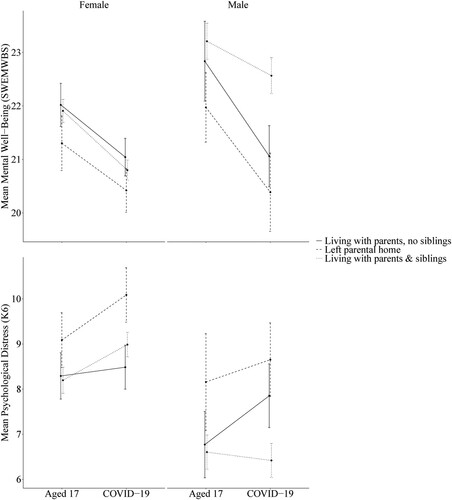

shows how mental health varied by household living arrangements in the raw data at age 17 and during the first lockdown. Young adult mental health declined between ages 17 and the first COVID-19 lockdown (when participants were aged 19), with mental well-being (SWEMWBS) decreasing and psychological distress (K6) increasing for both men and women on average. One exception is recorded SWEMWBS and K6 scores for young men living with parents and siblings, which did not change on average. Young women’s mental health at age 17 was worse than young men’s, and young women reported worse mental health during the first lockdown. On both outcome measures, men living with parents and siblings reported the best mental health during the first lockdown. In contrast, young women living away from the parental home reported notably higher K6 and descriptively lower SWEMWBS than the other living arrangement categories.

Figure 1. Mean Shortened Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale scores (SWEMWBS, top) and Kessler 6 Question Psychological Distress Scale scores (K6, bottom) pre-pandemic (age 17) and during the first lockdown (May 2020, age 19), by COVID-19 family living arrangements and gender.

Note: Weighted mean and 95% confidence interval error bar. Mean mental health scores (i.e. SWEMWBS and K6) were collected during Wave 7 of the mainstage survey and Wave 1 of the CLS COVID-19 survey (May 2020) during the first lockdown. Missing values in the sample (N = 2,578) were filled using multiple imputation of chained equations.

shows the estimated association between living with parents (and siblings) and changes in young adults’ SWEMWBS and K6 scores during the first national COVID-19 lockdown. Compared to living with parents and no siblings, living with parents and siblings was associated with improved mental health for young men across both measures, with significant positive coefficients for SWEMWBS scores and negative coefficients for K6 scores. On the other hand, young women living outside the parental home during the first lockdown reported significantly higher K6 scores than those living with parents and no siblings. Unlike men’s SWEMWBS scores, women’s SWEMWBS scores were not associated with family living arrangements. We also found that, compared to living with parents alone, women reported no additional benefit of living with siblings. These results are robust to the inclusion of controls for young adult COVID-19 economic activity and childhood family characteristics (Model 2) as well as the effect of increased intra-household conflict since the beginning of COVID-19 (Model 3). also shows that those with higher K6 scores at age 17 reported greater increases in K6 during the first lockdown, whilst those with higher SWEMWBS at age 17 reported higher SWEMWBS in lockdown. For all young adults, those who were unemployed or furloughed, experienced a living arrangement change since March 2020, and reported increased intra-household conflict were associated with reduced mental health. However, the inclusion of these variables did not alter the observed associations between our explanatory factors and outcome measures. Though not included here, the authors also stratified the sample by income, finding that the magnitude of reported effects increases for those from high income households, although the direction and significance of effects is like our main analysis.

Table 2. Estimated association between family living arrangements and young adult mental health during the first COVID-19 lockdown, interacting living arrangements with gender.

summarises the association between family living arrangements and young adult mental health, on a sample restricted to participants with siblings, as well as whether there is any effect of sibling factors. As in the overall sample, for young men living with parents and siblings during the first lockdown with reported significantly improved mental health in both measures. Also, similar to the full sample, young women living away from the parental home reported worse mental health, with significantly increased K6 scores and descriptively lower SWEMWBS scores. Being an oldest sibling and the experience of childhood sibling bullying were related to slightly related to increased K6 scores, after including available control factors.

Table 3. Estimated association between family living arrangements, sibling factors, and young adult mental health during the first COVID-19 lockdown, interacting living arrangements with gender, on a sample of only siblings

Changes over the course of the pandemic

Young adults’ living arrangements changed as they adapted to the pandemic and as restrictions eased (Appendix Table A1). In the first wave, 91% of young adults were living with parents and siblings. This co-residence decreased dramatically by Autumn 2020, to 63% and remained close to this level in Spring 2021. Young adults who had left the parental home by Wave 2 did not return to home by Spring 2021 (Wave 3), despite lockdown measures being in place again. Appendix Table A2 provides further detail on how the living arrangements of the samples in Waves 2 and 3 differ from those in Wave 1 (reported in ).

Young adults’ living arrangement changes during the later stages of the pandemic and their gradual resumption of everyday life could indicate an adaptation to COVID-19 and, in comparison to the first lockdown, a decrease in the importance of family living arrangements to young adults’ mental health. Given these changes, we expected that the association between family living arrangements and mental health would change over the course of the pandemic.

summarizes our LDV models estimated across all observed COVID-19 periods. Coinciding with observed living arrangement changes, lockdown restriction relaxation, and potential young adult adaption to remaining restrictions (e.g. social distancing Aksoy Citation2022), we find that the positive association between sibling co-residence and young men’s mental health disappears after the first lockdown. In a reversal of the effect from Wave 1, after the first lockdown, for young women living away from the parental home were associated with slightly lower K6 scores and slightly higher SWEMWBS scores in Spring 2021. In contrast, for young men, living alone was associated with worse K6 and SWEMWBS scores by Spring 2021, although young men on average also reported better mental health in this period.

Table 4. Estimated association between family living arrangements and young adult mental health during three periods of COVID-19, interacting living arrangements with gender.

Sensitivity analyses

Our sensitivity analyses show that our results are robust to alternative specifications. First, when controlling for potential sample differences in between the repeated cross-sections of the three COVID-19 waves, we find that, while the smaller sample shows less significance overall, the direction of effects is unchanged (Appendix Table A3). Additionally, we estimated FE of the family living arrangement variables on the change in young adult mental health, using pre-pandemic mental health and all three periods during the pandemic, and exploring gender effects by interacting gender with living arrangements (Appendix Table A4). Investigating how FE varied when including mental health changes beyond the first lockdown, Appendix Table A4 confirms the expectation that apart from the shock of the initial lockdown, as the pandemic wore on, parent and sibling co-residence impacted young adult mental health less. Both these sensitivity analyses show that the moderating effect of siblings on young adult mental health was not constant across the pandemic, and instead was strongest in the first lockdown.

Discussion

As the UK entered lockdown in the spring of 2020, young adults experienced abrupt disruptions to the normal milestones associated with the transition to adulthood (Shanahan et al. Citation2020), risking young adult mental health, especially during national lockdowns (Stroud and Gutman Citation2021). While siblings may act as important source of social and emotional support during crisis, the literature has not yet examined the role of siblings in influencing young adults’ mental health during COVID-19. Moreover, studies that have examined the relationship between family co-residence and young adult mental health during the pandemic have been unable to account for mental health prior to the pandemic (Campione-Barr et al. Citation2021; Cassinat et al. Citation2021; Evandrou et al. Citation2021). We used MCS data, collected before, during, and after the first UK lockdown, and we estimated non-dynamic longitudinal models to investigate the associations between young adult COVID-19 residential arrangements with parents and siblings and mental health during the first lockdown via both K6 and SWEMWBS scores, whilst allowing for gender variation. We also investigated whether sibling characteristics changed the association of family living arrangements and young adult mental health as well as how these effects altered as the pandemic progressed.

Young adults’ mental health is particularly vulnerable to unpredictable and drastic life-course changes, such as those experienced during the pandemic (Shanahan et al. Citation2020). Following expectations and corresponding with prior work (Park et al. Citation2019; Sage et al. Citation2013; Wu and Grundy Citation2023), our findings suggest that living in the parental home provided an important source of social and emotional support during the first national lockdown. We find that, while family living arrangements were important in the first lockdown, the importance of family declined over the course of the pandemic, including during subsequent lockdowns. Shedding light on a conflicted evidence base (Copp et al. Citation2017; Preetz et al. Citation2021; Wu and Grundy Citation2023), our findings illustrate the importance of the context and timing of co-residence to the observed relationship between family living arrangements and young adults’ mental health.

Our results highlight important gender differences in the association of family living arrangements on young adult mental health. Particularly, living precariously but independently may hurt young women’s mental health more than young men’s (Chiuri and Del Boca Citation2010). Living with siblings may provide additional support compared to that received from parents alone (McHale et al. Citation2012), but only young men may feel these sibling-related mental health supports (Cable et al. Citation2013; Voorpostel and Blieszner Citation2008). These findings align with literature showing that young women often have more complex and less favorable family relationships than men (Sandberg-Thoma et al. Citation2015; Stone et al. Citation2014; Tosi Citation2017). One explanation for this may be that men and women have a different relationship between mental health and sibling networks, due to gendered familial responsibilities and gendered differences in the social significance of families (e.g. Schulz Citation2021). Another potential explanation is that fraternal connections are more activated under familial strain than sororal relationships (Voorpostel and Blieszner Citation2008). Our findings suggest that gender continues to influence how family members support and relate to each other during early adulthood (McHale et al. Citation2003; Stone et al. Citation2014), and that these gendered family processes played an important role in moderating mental health during the first national lockdown.

Despite existing literature linking sibling factors and economic activity to mental health (Cicirelli Citation1995; Copp et al. Citation2017; Tosi and Grundy Citation2018; White Citation2001), we find little effect of these covariates in our models. The general lack of significant association between young adult mental health during the first lockdown and sibling characteristics suggests that young adult mental health was more strongly affected by sibling co-residence during the unprecedented social restrictions of the first lockdown than by specific factors that may cause variations in young adult sibling relationships under more ordinary circumstances. This aligns with research that finds sibling support strongest during periods of crisis, regardless of prior sibling relationship or sibling dyad characteristics (Milevsky et al. Citation2005; Van Volkom Citation2006). Similarly, the relationship between mental health and living arrangements was unaffected by the addition of our further covariates (e.g. economic activity), contrasting prior studies (Copp et al. Citation2017; Tosi and Grundy Citation2018). The lack of sibling characteristic and covariate effects in our COVID-19 models reinforces the idea that context and timing matters for when and how family co-residence supports young adult mental health.

Comparing our two outcome measures, we find that the pandemic had a significant effect on men’s SWEMWBS and K6 scores, indicating living with siblings was important for protecting young men’s positive social functioning, in addition to protecting against mental ill-health. On the other hand, women reported higher average K6 scores, but with large variation, when living away from the parental home during the first lockdown. One reason for an effect only being seen for men and women using the K6 measure is that lockdown-related uncertainty, loss of control, and social isolation more directly affected symptoms of non-specific emotional dysfunction, or distress, which are measured with the K6 (Shanahan et al. Citation2020). On the other hand, it is possible that, for young adults, especially young men, the childhood family more strongly affects the social connection measured with the SWEMWBS. We found that for young men living with siblings saw both their psychological stress decrease and their mental well-being increase, which mirrors the findings of existing studies on older adults (Cable et al. Citation2013). This positive association of siblings with mental health for young men underlines the importance of these family members to those facing disruptions and adjustments in their lives.

Although we provide evidence showing how living with parents and siblings might buffer young adults’ mental health during the UK’s first lockdown, we were not able to control for a range of other factors affecting the mental health of young adults during the pandemic. For example, despite controlling for prior mental health, other unobserved factors, such as poor familial relationships or geographical distance from family (Sandberg-Thoma et al. Citation2015), may affect young adults’ mental health. Data limitations, for example those which limit our ability to identify boomerang moves, further limit our analysis. Thus, while our results are robust to numerous alternative specifications, there may be other factors driving the observed association between family living arrangements and mental health during the pandemic.

Despite these limitations, we have shown how living with parents and siblings helped protect young adult mental health during the first UK lockdown. We highlighted gender differences in how young adults responded to family support during a crisis, showing that young women not living with parents were vulnerable to high levels of psychological distress, and siblings protected young men’s mental health. Because we used COVID-19 data, future research should consider how young adults with low levels of mental health during, and due to, COVID-19 affects this cohort’s social emotional outcomes moving forward. Additionally, future research may further investigate how young adult sibling relationships evolve in relation to crisis, and the role of sibling relationship quality in supporting mental health during the uncertain life period of young adulthood. This may help us understand why only young men benefitted from living with siblings during COVID-19.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (2.2 MB)Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Esther Dermott and Dr Julia Gumy for useful advice. We are also grateful for the helpful comments from the journal’s editors and peer reviewers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 See Appendix Table A1 for a description of changes in family living arrangements across three different periods of the pandemic.

2 A small portion of MCS participants in the CLS COVID-19 Wave 1 survey were aged 18 when they responded (CLS Citation2021).

3 Missing values for frequent childhood sibling bullying (N = 97) were filled using multiple imputation (by chained equations).

4 In subsequent COVID-19 waves, this question was slightly altered to be worded as ‘Have there been any changes to the people you are living with since the Coronavirus outbreak in March?’ in Wave 2, and ‘since the Coronavirus outbreak in March 2020?’ in Wave 3.

5 After the first wave of the CLS COVID-19 survey, information regarding university attendance changed. So, for the second and third wave, as well as when comparing results from the three waves together, we use a slightly different economic activity variable with only five categories, by merging the group of those being in university with the group of those being in education or training.

6 Because parental education is considered relatively stable, if parental education information at Wave 6 is missing but available at Wave 5, the Wave 6 missing answer is filled with Wave 5. After backfilling with available cases in Wave 5, any residual missing values (< 1% of cases) were then also filled with multiple imputation.

7 Intra-household COVID-19 conflict was unavailable in the second and third waves, therefore was excluded from this part of the analysis. Additionally, changes in living arrangements was only asked of participants once. So, when investigating the second and third COVID-19 wave, we feed forward preceding COVID-19 living arrangement responses for those who participated in multiple COVID-19 waves.

References

- Aksoy, O. (2022) ‘Within-family influences on compliance with social-distancing measures during COVID-19 lockdowns in the United Kingdom’, Nature Human Behaviour 6: 1660–8. doi:10.1038/s41562-022-01465-w.

- Angrist, J. D. and Pischke, J.-S. (2009) Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion. Woodstock, Oxfordshire: Princeton University Press.

- Batz, C. and Tay, L. (2018) ‘Gender differences in subjective well-being’, in E. Diener, S. Oishi and L. Tay (eds.), Handbook of Well-Being, Salt Lake City: DEF Publishers, pp. 358–72.

- Beck, U. and Beck-Gernsheim, E. (2002) Individualization: Institutionalized Individualism and Its Social and Political Consequences, London: Sage.

- Blanden, J., Goodman, A., Gregg, P. and Machin, S. (2002) Changes in Intergenerational Mobility in Britain. London: Centre for the Economics of Education, London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Brown, M., Goodman, A., Peters, A., Ploubidis, G. B., Sanchez, A., Silverwood, R. and Smith, K. (2024) COVID-19 Survey in Five National Longitudinal Studies: Waves 1, 2 and 3 User Guide (User Guide No. Version 4), London: UCL Centre for Longitudinal Studies and MRC Unit for Lifelong Health and Ageing.

- Brown, J., Kirk-Wade, E., Baker, C. and Barber, S. (2021) Coronavirus: A history of “Lockdown Laws” in England (No. 9068), London: House of Commons Library.

- Buuren, S. and Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. (2011) ‘Mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R’, Journal of Statistical Software 45: 1–67. doi:10.18637/jss.v045.i03.

- Cable, N., Bartley, M., Chandola, T. and Sacker, A. (2013) ‘Friends are equally important to men and women, but family matters more for men’s well-being’, Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 67: 166–71. doi:10.1136/jech-2012-201113.

- Campione-Barr, N., Rote, W., Killoren, S. E. and Rose, A. J. (2021) ‘Adolescent adjustment during COVID-19: the role of close relationships and COVID-19-related stress’, Journal of Research on Adolescence 31: 608–22. doi:10.1111/jora.12647.

- Cassinat, J. R., Whiteman, S. D., Serang, S., Dotterer, A. M., Mustillo, S. A., Maggs, J. L. and Kelly, B. C. (2021) ‘Changes in family chaos and family relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from a longitudinal study’, Developmental Psychology 57: 1597–610. doi:10.1037/dev0001217.

- Chiuri, M. C. and Del Boca, D. (2010) ‘Home-leaving decisions of daughters and sons’, Review of Economics of the Household 8: 393–408. doi:10.1007/s11150-010-9093-2.

- Cicirelli, V. (1995) Sibling Relationships Across the Life Span, New York, USA: Springer Science & Business Media.

- CLS (2021) COVID-19 Survey in Five National Longitudinal Cohort Studies: Millennium Cohort Study, Next Steps, 1970 British Cohort Study and 1958 National Child Development Study, 2020–2021.

- CLS (2022a) Millennium Cohort Study: Age 3, Sweep 2, 2004. doi:10.5255/UKDA-SN-5350-6.

- CLS (2022b) Millennium Cohort Study: Age 9 Months, Sweep 1, 2001. doi:10.5255/UKDA-SN-4683-6.

- CLS (2022c) Millennium Cohort Study: Age 5, Sweep 3, 2006. doi:10.5255/UKDA-SN-5795-6.

- CLS (2022d) Millennium Cohort Study: Age 7, Sweep 4, 2008. doi:10.5255/UKDA-SN-6411-9.

- CLS (2022e) Millennium Cohort Study: Age 17, Sweep 7, 2018. doi:10.5255/UKDA-SN-8682-2.

- CLS (2022f) Millennium Cohort Study: Age 11, Sweep 5, 2012. doi:10.5255/UKDA-SN-7464-5.

- CLS (2023) Millennium Cohort Study: Age 14, Sweep 6, 2015. doi:10.5255/UKDA-SN-8156-7.

- Conger, K. J. and Little, W. M. (2010) ‘Sibling relationships during the transition to Adulthood’, Child Development Perspectives 4: 87–94. doi:10.1111/j.1750-8606.2010.00123.x.

- Copp, J. E., Giordano, P. C., Longmore, M. A. and Manning, W. D. (2017) ‘Living With parents and emerging adults’ depressive Symptoms’, Journal of Family Issues 38: 2254–76. doi:10.1177/0192513X15617797.

- Elzinga, C. H. and Liefbroer, A. C. (2007) ‘De-standardization of family-life trajectories of young adults: a cross-national comparison using sequence analysis’, European Journal of Population / Revue Européenne de Démographie 23: 225–50. doi:10.1007/s10680-007-9133-7.

- Evandrou, M., Falkingham, J., Qin, M. and Vlachantoni, A. (2021) ‘Changing living arrangements and stress during Covid-19 lockdown: evidence from four birth cohorts in the UK’, SSM – Population Health 13: 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100761.

- Gyani, A., Shafran, R., Layard, R. and Clark, D. M. (2013) ‘Enhancing recovery rates: lessons from year one of IAPT’, Behaviour Research and Therapy 51: 597–606. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2013.06.004.

- Hall, S. S. and Zygmunt, E. (2021) ‘I hate it here: mental health changes of college students living with parents during the COVID-19 quarantine’, Emerging Adulthood 9: 449–61. doi:10.1177/21676968211000494.

- Harkness, S., Gregg, P. and Fernández-Salgado, M. (2020) ‘The rise in single-mother families and children’s cognitive development: evidence from three British birth cohorts’, Child Development 91: 1762–85. doi:10.1111/cdev.13342.

- Harper, J. M., Padilla-Walker, L. M. and Jensen, A. C. (2016) ‘Do siblings matter independent of both parents and friends? Sympathy as a mediator between sibling relationship quality and adolescent outcomes’, Journal of Research on Adolescence 26: 101–14. doi:10.1111/jora.12174.

- Her, Y., Vergauwen, J. and Mortelmans, D. (2022) ‘Nest leaver or home stayer? Sibling influence on parental home leaving in the United Kingdom’, Advances in Life Course Research 52: 100464. doi:10.1016/j.alcr.2022.100464.

- Hill, T. D., Davis, A. P., Roos, J. M. and French, M. T. (2020) ‘Limitations of fixed-effects models for panel data’, Sociological Perspectives 63: 357–69. doi:10.1177/0731121419863785.

- Hollifield, C. R. and Conger, K. J. (2015) ‘The role of siblings and psychological needs in predicting life satisfaction during emerging adulthood’, Emerging Adulthood 3: 143–53. doi:10.1177/2167696814561544.

- Institute for Government (2022) Timeline of UK Government Coronavirus Lockdowns and Restrictions (Data Visualisation), London: Institute for Government.

- Jensen, A. C., Whiteman, S. D. and Fingerman, K. L. (2018) ‘Can’t live with or without them: transitions and young adults’ perceptions of sibling relationships’, Journal of Family Psychology 32: 385–95. doi:10.1037/fam0000361.

- Jensen, A. C., Whiteman, S. D., Fingerman, K. L. and Birditt, K. S. (2013) ‘Life still isn’t fair: parental differential treatment of young adult siblings’, Journal of Marriage and Family 75: 438–52. doi:10.1111/jomf.12002.

- Johansen, R., Espetvedt, M. N., Lyshol, H., Clench-Aas, J. and Myklestad, I. (2021) ‘Mental distress among young adults – gender differences in the role of social support’, BMC Public Health 21: 2152. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-12109-5.

- Johnston, J. and DiNardo, J. (1997) Econometric Methods, 4th ed. McGraw-Hill International Editions. Economics SERIES, London: McGraw-Hill.

- Kalmijn, M. (2013) ‘Adult children’s relationships with married parents, divorced parents, and stepparents: biology, marriage, or residence?’, Journal of Marriage and Family 75: 1181–93. doi:10.1111/jomf.12057.

- Kazdin, A. E. (1993) ‘Adolescent mental health. Prevention and treatment programs’, American Psychologist 48: 127–41. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.48.2.127.

- Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S. L. T., Walters, E. E. and Zaslavsky, A. M. (2002) ‘Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress’, Psychological Medicine 32: 959–76. doi:10.1017/S0033291702006074.

- Kins, E. and Beyers, W. (2010) ‘Failure to launch, failure to achieve criteria for adulthood?’, Journal of Adolescent Research 25: 743–77. doi:10.1177/0743558410371126.

- Kung, C. S. J., Kunz, J. S. and Shields, M. A. (2023) ‘COVID-19 lockdowns and changes in loneliness among young people in the U.K’, Social Science & Medicine 320: 115692. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.115692.

- Lawson, D. W. and Mace, R. (2010) ‘Siblings and childhood mental health: evidence for a later-born advantage’, Social Science & Medicine 70: 2061–9. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.009.

- Lee, C.-Y. S. and Goldstein, S. E. (2016) ‘Loneliness, stress, and social support in young adulthood: does the source of support matter?’, Journal of Youth and Adolescence 45: 568–80. doi:10.1007/s10964-015-0395-9.

- Luppi, F., Rosina, A. and Sironi, E. (2021) ‘On the changes of the intention to leave the parental home during the COVID-19 pandemic: a comparison among five European countries’, Genus 77: 1–23. doi:10.1186/s41118-021-00117-7.

- McHale, S. M., Crouter, A. C. and Whiteman, S. D. (2003) ‘The family contexts of gender development in childhood and adolescence’, Social Development 12: 125–48. doi:10.1111/1467-9507.00225.

- McHale, S. M., Updegraff, K. A. and Whiteman, S. D. (2012) ‘Sibling relationships and influences in childhood and Adolescence’, Journal of Marriage and Family 74: 913–30. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.01011.x.

- Merry, J. J., Bobbitt-Zeher, D. and Downey, D. B. (2020) ‘Number of siblings in childhood, social outcomes in adulthood’, Journal of Family Issues 41: 212–34. doi:10.1177/0192513X19873356.

- Mewton, L., Kessler, R. C., Slade, T., Hobbs, M. J., Brownhill, L., Birrell, L., Tonks, Z., Teesson, M., Newton, N., Chapman, C., Allsop, S., Hides, L., McBride, N. and Andrews, G. (2015) ‘The psychometric properties of the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6) in a general population sample of adolescents’, Psychological Assessment 28: 1232–42. doi:10.1037/pas0000239.

- Milevsky, A., Smoot, K., Leh, M. and Ruppe, A. (2005) ‘Familial and contextual variables and the nature of sibling relationships in emerging adulthood’, Marriage & Family Review 37: 123–41. doi:10.1300/J002v37n04_07.

- Miller, D. L., Shenhav, N. and Grosz, M. (2023) ‘Selection into identification in fixed effects models, with application to head start’, Journal of Human Resources 58: 1523–66. doi:10.3368/jhr.58.5.0520-10930R1.

- Park, S. S., Wiemers, E. E. and Seltzer, J. A. (2019) ‘The family safety net of black and white multigenerational families’, Population and Development Review 45: 351–78. doi:10.1111/padr.12233.

- Platt, L. and Warwick, R. (2020) ‘COVID-19 and ethnic inequalities in England and Wales’, Fiscal Studies 41: 259–89. doi:10.1111/1475-5890.12228.

- Preetz, R., Filser, A., Brömmelhaus, A., Baalmann, T. and Feldhaus, M. (2021) ‘Longitudinal changes in life satisfaction and mental health in emerging adulthood during the COVID-19 pandemic’, Emerging Adulthood 9: 602–17. doi:10.1177/21676968211042109.

- Sage, J., Evandrou, M. and Falkingham, J. (2013) ‘Onwards or homewards? Complex graduate migration pathways, well-being, and the ‘parental safety net’, Population, Space and Place 19: 738–55. doi:10.1002/psp.1793.

- Sandberg-Thoma, S. E., Snyder, A. R. and Jang, B. J. (2015) ‘Exiting and returning to the parental home for boomerang kids’, Journal of Marriage and Family 77: 806–18. doi:10.1111/jomf.12183.

- Schulz, F. (2021) ‘Mothers’, fathers’ and siblings’ housework time within family households’, Journal of Marriage and Family 83: 803–19. doi:10.1111/jomf.12762.

- Shanahan, M. J. (2000) ‘Pathways to adulthood in changing societies: variability and mechanisms in life course perspective’, Annual Review of Sociology 26: 667–92. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.667.

- Shanahan, L., Steinhoff, A., Bechtiger, L., Murray, A. L., Nivette, A., Hepp, U., Ribeaud, D. and Eisner, M. (2020) ‘Emotional distress in young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence of risk and resilience from a longitudinal cohort study’, Psychological Medicine 52: 824–33. doi:10.1017/S003329172000241X.

- Sharp, J. and Theiler, S. (2018) ‘A review of psychological distress among university students: pervasiveness, implications and potential points of intervention’, International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling 40: 193–212. doi:10.1007/s10447-018-9321-7.

- Shen, J. and Bartram, D. (2021) ‘Fare differently, feel differently: mental well-being of UK-born and foreign-born working men during the COVID-19 pandemic’, European Societies 23: S370–S383. doi:10.1080/14616696.2020.1826557.

- Silverwood, R., Narayanan, M., Dodgeon, B. and Ploubidis, G. (2021) Handling Missing Data in the National Child Development Study: User Guide (Version 2), London: UCL Centre for Longitudinal Studies.

- Spéder, Z., Murinkó, L. and Settersten, R. A. (2014) ‘Are conceptions of adulthood universal and unisex? Ages and social markers in 25 European countries’, Social Forces 92: 873–98. doi:10.1093/sf/sot100.

- Stewart-Brown, S., Tennant, A., Tennant, R., Platt, S., Parkinson, J. and Weich, S. (2009) ‘Internal construct validity of the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): a Rasch analysis using data from the Scottish Health Education Population Survey’, Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 7: 1–8. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-7-15.

- Stone, J., Berrington, A. and Falkingham, J. (2014) ‘Gender, turning points, and boomerangs: returning home in young adulthood in Great Britain’, Demography 51: 257–76. doi:10.1007/s13524-013-0247-8.

- Stroud, I. and Gutman, L. M. (2021) ‘Longitudinal changes in the mental health of UK young male and female adults during the COVID-19 pandemic’, Psychiatry Research 303: 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114074.

- Tennant, R., Hiller, L., Fishwick, R., Platt, S., Joseph, S., Weich, S., Parkinson, J., Secker, J. and Stewart-Brown, S. (2007) ‘The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): development and UK validation’, Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 5: 1–13. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-5-63.

- Thomas, P. A., Liu, H. and Umberson, D. (2017) ‘Family relationships and well-Being’, Innovation in Aging 1: 1–11.

- Tosi, M. (2017) ‘Leaving-home transition and later parent–child relationships: proximity and contact in Italy’, European Societies 19: 69–90. doi:10.1080/14616696.2016.1226374.

- Tosi, M. and Grundy, E. (2018) ‘Returns home by children and changes in parents’ well-being in Europe’, Social Science & Medicine 200: 99–106. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.01.016.

- Van Volkom, M. (2006) ‘Sibling relationships in middle and older adulthood: a review of the literature’, Marriage & Family Review 40: 151–70. doi:10.1300/J002v40n02_08.

- Van Volkom, M., Guerguis, A. J. and Kramer, A. (2017) ‘Sibling relationships, birth order, and personality among emerging adults’, Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Science 5: 21–28.

- Voorpostel, M. and Blieszner, R. (2008) ‘Intergenerational solidarity and support between adult siblings’, Journal of Marriage and Family 70: 157–67. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00468.x.

- Westerhof, G. J. and Keyes, C. L. M. (2010) ‘Mental illness and mental health: the two continua model across the lifespan’, Journal of Adult Development 17: 110–9. doi:10.1007/s10804-009-9082-y.

- White, L. K. (2001) ‘Sibling relationships over the life course: a panel analysis’, Journal of Marriage and Family 63: 555–68. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00555.x.

- Wright, L., Steptoe, A. and Fancourt, D. (2020) ‘Are we all in this together? Longitudinal assessment of cumulative adversities by socioeconomic position in the first 3 weeks of lockdown in the UK’, Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 683–688.

- Wright, L., Steptoe, A. and Fancourt, D. (2022) ‘Trajectories of compliance with COVID-19 related guidelines: longitudinal analyses of 50,000 UK adults’, Annals of Behavioral Medicine 56: 781–90. doi:10.1093/abm/kaac023.

- Wu, J. and Grundy, E. (2023) ‘Boomerang’ moves and young adults’ mental well-being in the United Kingdom’, Advances in Life Course Research 56: 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.alcr.2023.100531.