Abstract

Narrative news is often propagated as a means to inform and attract younger generations of news consumers. To test this, the current study assessed the effects of narrative structure versus inverted pyramid structure on information processing and news appreciation for Millennials, compared to Generation X, and Baby Boomers/Silent Generation. Participants were randomly exposed to either four online news articles written in a narrative structure or an inverted pyramid structure. Results show that people are better informed by narrative news. However, appreciation is lower for narrative news compared to the inverted pyramid. Moreover, the younger participants express lower appreciation, regardless of story structure. The results suggest that although the narrative structure is best at informing all audiences, it is not necessarily a viable strategy to attract younger news audiences.

Introduction

Young people do not enjoy following the news (Costera Meijer Citation2007; Marchi Citation2012; Mindich Citation2005). Research from the Pew Research Center (Citation2012) shows that just 29 percent of Millennials (aged 18–34) say they enjoy following the news a lot, compared to 45 percent of Generation Xers (35–55) and 58 percent of the oldest age groups (Silent Generation and Baby Boomers). The same survey indicates that those who do enjoy following the news get more news. In addition, those who enjoy keeping up with the news have a positive attitude towards news content (Nabi and Krcmar Citation2004). A more recent study (Pew Research Center Citation2016) shows that 27 percent of Millennials say they follow the news all or most of the time, compared to 46 percent of Generation Xers, 61 percent of the Baby Boomers and 77 percent of the Silent Generation. Although Millennials and Generation Xers are more likely to get their news online than older generations, their total frequency of news use lags seriously behind Baby Boomers and the Silent Generation. As a result, today’s youngest generations do not even come close to matching the news interest of previous generations (cf. Patterson Citation2007; Wayne et al. Citation2010). Longitudinal research indicates that younger generations will not increase their news intake as they get older (Pew Research Center Citation2012).

This is reflected in the fact that young news users tend to have relatively poor understanding and recollection of news, and low levels of political knowledge (Delli Carpini and Keeter Citation1996; Donsbach Citation2011; Patterson Citation2007). These trends point to a failure of news media to inform young people and to the danger of new generations becoming disengaged from civil society (cf. Aalberg, Blekesaune, and Elvestad Citation2013; Galston Citation2001, Citation2007; Norris Citation2000). Therefore, a major challenge for journalism in the early twenty-first century is to find ways to make news more attractive for younger people—while simultaneously keeping them informed on serious matters (Rogers Citation2010; Zerba Citation2008).

One up and coming strategy to achieve this is the application of narrative structure in news stories (Abrahamson Citation2006; Høyer and Nossen Citation2015; Johnston Citation2007; Shim Citation2014; Ytreberg Citation2001). This involves presenting a news report in a storytelling format. Shaping a news report in this manner may well be a good option to attract younger news audiences. Recent research has demonstrated the superiority of storytelling presentation in terms of information transfer, audience appeal, and engagement as compared to the conventional and dominant form of structuring news stories non-chronologically, the inverted pyramid structure (cf. Berinsky and Kinder Citation2006; Knobloch et al. Citation2004; Lang Citation1989; Machill, Köhler, and Waldhauser Citation2007; Wise et al. Citation2009; Yaros Citation2006). For this reason, critics have labeled the inverted pyramid as past its currency (cf. Emde, Klimmt, and Schluetz Citation2016; Fry Citation1999; Machill, Köhler, and Waldhauser Citation2007).

Although the narrative structure seems a viable strategy for informing and attracting young people, there are also indications that the positive effects on some aspects of information acquisition may be conditional upon user characteristics such as gender and age (Emde, Klimmt, and Schluetz Citation2016; Sternadori and Wise Citation2010). Only a limited number of studies have investigated its effects on young people’s information processing, whereas no research exists on the effects of narrative news on appreciation, nor were effects compared for other specific age groups. One study suggests that young news users’ processing of news presented in a narrative structure is superior to news presented as an inverted pyramid, but this effect was only found for those low in prior knowledge (Emde, Klimmt, and Schluetz Citation2016). Building upon this study, it is relevant to investigate whether cognitive effects of narrative presentation are singular and especially relevant to the younger age groups or whether these are general format effects that apply to all age groups. Beyond information processing, it is worthwhile investigating whether narrative news has an advantage over conventional news structures in making news more attractive to young news users, while simultaneously avoiding alienating older age groups. The present study does this by experimentally assessing the effects of the narrative structure versus the traditional inverted pyramid structure for three different age groups—Millennials, Generation X, and Baby Boomers/Silent Generation—on information processing and news appreciation.

News Story Structure and Information Processing

Since the nineteenth century, the inverted pyramid structure has been the staple conventional news report format. In terms of journalistic professionalism, it is regarded as the most objective and factual format (Høyer and Nossen Citation2015; Johnston Citation2007; Mindich Citation2000; Pöttker Citation2003; Schudson Citation1982, Citation2005). The most important facts—as defined by journalists in the What, When, Where, and Who of a news event (cf. Findahl and Höijer Citation1985)—are presented first, often with the most current events, such as the outcome, up top. Only in later parts of the story is the event given context, such as its origins and consequences (Van Dijk Citation1983). By contrast, the narrative story structure is traditionally associated with softer news stories and background features. However, it can also be applied to hard news stories (Johnston Citation2007). The narrative format follows a line of reporting that is reminiscent of storytelling. It is characterized by a format in which the several parts of an event are placed in chronological order, with a beginning, middle, and an end, with the outcome of an event often only given at the end of the story, and in which there is more focus on characters’ point of view (Britton et al. Citation1983; Emde, Klimmt, and Schluetz Citation2016; Knobloch et al. Citation2004; Rodríguez Citation2004).

To explain the differential effects of inverted pyramid structure and narrative structure on information processing, this study takes both the construction-integration model (Johnson-Laird Citation1983; Kintsch Citation1988; Kintsch and Van Dijk Citation1978) and the Limited Capacity Model of Motivated Mediated Message Processing (LC4MP; Lang Citation2000, Citation2006) as its theoretical foundation. While the LC4MP and the construction-integration models are different in many respects, together they provide a clear outline of how news stories are processed. The primary goal of message processing is to reach a level of understanding of the message being processed. Understanding depends on attentional focus and memory. The degree to which cognitive resources are allocated to processing information determines the degree to which the information is understood and learned. In both models it is assumed that the cognitive capacity of the human brain is limited.

The construction-integration model postulates that in order to achieve understanding, and to facilitate later retrieval of information, news users must construct a mental representation of the story (Johnson-Laird Citation1983; Kintsch Citation1988; Kintsch and Van Dijk Citation1978). Several processes work together to achieve this. News users allocate cognitive resources using previously stored information from semantic (long-term) memory, while simultaneously processing incoming information from the news story episodically in working memory. Integrating both streams of information results in a mental model, consisting of specific characteristics of the event as well as a temporal ordering of the various parts, that gets stored in long-term memory for later retrieval (Berinsky and Kinder Citation2006; Findahl and Höijer Citation1985; Lang Citation1989; Tulving Citation2002; Wise et al. Citation2009). These processes continue as long as the news story is received, with new information constantly being updated to fit into the mental model (Busselle and Bilandzic Citation2009).

Thus, the construction-integration model suggests that constructing a coherent mental model is needed for comprehension and learning. The LC4MP specifies how this process may be inhibited or enhanced by the allocation of attentional focus and memory faculties (Wise et al. Citation2009). To construct a model, a news user must keep selected bits of information from the news in working memory. During processing, another part of the cognitive effort is simultaneously devoted to bringing information from existing mental representations in semantic memory into working memory, to form associations with the incoming new information. But processing resources are limited (Lang Citation2000, Citation2006). Especially getting access to semantic memory requires effort that the user is not always capable or motivated enough to provide. If efficient use of semantic memory fails, this results in a less coherent mental model, lower comprehension, and more difficulty in later retrieval: the more resources devoted to constructing a model, the better the understanding and recollection (Lang Citation1989). The LC4MP assumes this may happen either because the user consciously decides to not invest the effort in the processing, or because the message requires too many cognitive resources. In either case, the cognitive resources invested into processing may not line up with the resources demanded for comprehension and learning.

Prior research suggests that news stories in the inverted pyramid structure place a relatively high burden on cognitive resources, whereas a chronological sequencing of events would leave more cognitive resources available for constructing a mental model (Sternadori and Wise Citation2010). The story is presented in such a way that reconstructing a coherent whole requires many instances in which inferences from semantic memory must be made, for instance in assessing the story topic and linking all the specific story elements and details into a coherent whole (Emde, Klimmt, and Schluetz Citation2016; Lang Citation1989; Wise et al. Citation2009). Because the inverted pyramid structure heavily taxes cognitive resources, the remaining resources may not be sufficient for encoding and storing all relevant information. This effect is exacerbated by insufficient background knowledge in many news users (Emde, Klimmt, and Schluetz Citation2016; Findahl and Höijer Citation1985).

In contrast, if a message is structured in a narrative format, generating associative links from the content and the integration of new information requires fewer resources because establishing coherence does not depend as heavily on extensive prior knowledge from semantic memory (Zwaan, Magliano, and Graesser Citation1995). One reason is that our brain processes information in a linear story-like fashion. Episodic memory operates through the linear sequencing of events, and humans construct narratives in memory from information they are presented, whether mediated or otherwise (Chaffee Citation1973; Schank and Abelson Citation1995; Tulving Citation1979). This explains why prior studies have shown superior information retrieval for more linear forms of presentation (Berinsky and Kinder Citation2006; Lang Citation1989; Lang, Potter, and Grabe Citation2003; Machill, Köhler, and Waldhauser Citation2007; Wise et al. Citation2009; Yaros Citation2006). If narrative news is more consistent with how the human brain processes information, then fewer cognitive resources should be required for processing compared to inverted pyramid news, leading to richer memory (Wise et al. Citation2009). In short, the narrative structure should facilitate information processing. One way of assessing this is by measuring recognition of information from the news report. We predict that:

H1: Information recognition is better for stories presented in the narrative structure compared to stories presented in the inverted pyramid structure.

News Story Structure and Appreciation

Beyond information processing, we are interested in how news users appreciate different news story structures, as an indication of their effectiveness to attract audiences. Prior research suggests that the narrative structure is superior to the inverted pyramid structure in this respect. In both news and non-news contexts, narrative structures elicit higher rates of positive affects—such as suspense, curiosity, engagement, empathy, and enjoyment—than the inverted pyramid (Busselle and Bilandzic Citation2009; Green, Brock, and Kaufman Citation2004; Knobloch et al. Citation2004; Oliver et al. Citation2012; Yaros Citation2006).

In entertainment studies, scholars have differentiated between the positive evaluations of narratives in terms of appreciation and enjoyment (Lewis, Tamborini, and Weber Citation2014; Oliver and Bartsch Citation2010; Oliver and Woolley Citation2010; Tamborini et al. Citation2011; Vorderer, Klimmt, and Ritterfeld Citation2004). Whereas enjoyment is defined as a “hedonistic” evaluation based on gratifying needs for fun and pleasure, appreciation is thought to reflect more cognitive, reflective affects. They also represent two distinct modes of information processing: enjoyment resulting from fast, automatic cognitive processes, and appreciation from slower, more deliberative processing. These distinct cognitive processes are used to appraise different narrative forms: media content that may not elicit direct emotional pleasure may still be appreciated on less hedonic gratifications, such as meaningfulness. For instance, a movie about a patient dying from disease is not very “enjoyable”, but may still be appreciated because it appeals to other, more reflective gratifications. While these conceptualizations stem from research and theory in the realm of entertainment media, in light of the idea that the relevance of news media is not so much to entertain but to appeal to non-hedonic, reflective values, this study takes appreciation as its evaluative variable.

There are two possible explanations why narrative news may enhance appreciation. First, because narrative stories connect to our natural modes of processing information, they put less demand on cognitive resources (Wise et al. Citation2009). Appreciation requires sufficient cognitive capacity (Vorderer, Knobloch, and Schramm Citation2001), whereas feeling cognitively overloaded is correlated with low appreciation of news (York Citation2013). Therefore, story formats that heavily tax resources or distract individuals and prevent engagement may hinder appreciation (Green, Brock, and Kaufman Citation2004). This means that in taking up relatively many cognitive resources, the inverted pyramid results in lower appreciation.

Second, narrative structures elicit the feeling of being “transported” into the story (Bilandzic and Busselle Citation2013; Busselle and Bilandzic Citation2009). The ability to become transported into or become engaged in narratives is presumed to be evolutionarily beneficial as a product of a human skill to envision possible future events and to plan future responses to these events (Leary and Buttermore Citation2003). In turn, the feeling of being transported into a story leads to positive evaluations of that story. Entertainment-education research has firmly established the ability of narratives to elicit transportation or engagement, as well as subsequent positive effects of transportation on both enjoyment and appreciation (Bilandzic and Busselle Citation2008, Citation2013; Busselle and Bilandzic Citation2009; Green, Brock, and Kaufman Citation2004; Oliver and Bartsch Citation2010; Quintero Johnson and Sangalang Citation2016; Sangalang, Quintero Johnson, and Ciancio Citation2013; Vorderer, Klimmt, and Ritterfeld Citation2004). Therefore, our second hypothesis states that:

H2: Appreciation is higher for news stories in the narrative structure compared to stories in the inverted pyramid structure.

Age Differences in Information Processing and Appreciation of Narrative News

To extend prior research, this study seeks to determine whether effects of story structure are specific to age groups, most notably younger ages, as often seems to be assumed by media professionals. Above, we argued that the narrative format is expected to be superior to the inverted pyramid format at informing as well as generating appreciation. But the question remains whether this is a general effect, or whether different age groups react differently to the narrative story structure. Prior research suggests that the positive effects narrative formats may be conditional upon user characteristics such as gender and prior knowledge (Emde, Klimmt, and Schluetz Citation2016; Sternadori and Wise Citation2010). Therefore, in the remaining part of this paper, we focus exclusively on the narrative structure and its effects with different age groups.

Research does not provide clear indications regarding the role of age, making it all the more relevant to study. On the one hand, information processing may be better among younger audiences because aging is associated with decline in cognitive processing. Compared to younger age groups, older individuals process information less accurately and more slowly, and have decreased working memory function (Park et al. Citation1996; Ramscar et al. Citation2014; Salthouse Citation2016). More generally, executive functions such as working memory performance and mental flexibility—needed to process information—deteriorate over the lifespan (Diamond Citation2013). In line with this, a number of studies have demonstrated that younger news users are better at recalling news than older age groups (cf. Frieske and Park Citation1999; Hill et al. Citation1989; Stine, Wingfield, and Myers Citation1990). As narrative news has been found to be less taxing on working memory resources than other formats, it might be predicted that particularly elder people can benefit from narrative story structure.

On the other hand, older age groups usually possess more news-related knowledge than younger ones (Curran et al. Citation2012; Delli Carpini and Keeter Citation1996; Patterson Citation2007). As high levels of prior knowledge facilitate information processing, the benefits of easy-to-process narrative structures may be less pronounced for older age groups than for younger age groups. To shed more light on the role of age, we formulate the following research question:

RQ1: Which age group benefits more from narrative news structures in terms of information processing?

Second, past or ongoing media behavior and media habits are a function of positive evaluations and preferences (e.g. Knobloch-Westerwick Citation2014; cf. Turel and Serenko Citation2012). Rooted in their different preferences, different generations develop different media use habits (Lee and Delli Carpini Citation2010). For instance, young people are more used to getting news from digital platforms, where they are more likely to encounter novel forms of journalism, such as narrative news styles (Høyer and Nossen Citation2015; Johnston Citation2007; Kramer Citation2000; Shim Citation2014; Ytreberg Citation2001). Furthermore, as youngsters want news to be more than just informative, they consume relatively little “serious” news while also making up the largest part of comedy news program audiences (Pew Research Center Citation2012). Once established, media habits hardly change over the lifespan (Lee and Delli Carpini Citation2010), indicating that the narrative story structure will appeal particularly to Millennials.

In sum, young news users are accustomed to using news that caters to their needs and preferences that go beyond mere information. These preferences, and the content and packaging of the news they use as a function of those preferences, are different from those of older generations. Thus, younger generations are expected to have a greater preference for and a higher exposure to alternative news styles that facilitate transportation and appreciation, including narrative news. Furthermore, exposure and appreciation are highly correlated: you appreciate what you are used to. We therefore expect that:

H3: Appreciation of narrative structured news stories is higher for Millennials compared to Generation Xers and Baby Boomers/Silent Generation.

Method

Design

An online experiment was conducted to investigate whether news stories presented in a narrative structure are better able to inform audiences and lead to more appreciation from different age groups in the news than stories presented in the inverted pyramid structure. Participants were randomly exposed to either four online news articles written in a narrative style (N = 96) or to four stories written in an inverted pyramid structure (N = 94). The dependent variable appreciation was measured repeatedly after each story by means of an online survey. Recognition for the four articles was tested at the end of the survey. The order in which the articles were presented was the same for all participants to ensure that the time between exposure to the articles and the questions measuring information processing of each article was comparable (they first got questions regarding article 1, then article 2, and so on). A small number of participants (N = 11) used a print version of the news articles and questionnaire because they had no internet access at the time they participated in the study.

Participants

Participants were recruited through social media, internet forums, or email. Moreover, some of the participants informed people in their network about the study by sending them the link to the study. A total number of 190 people participated in the experiment, 85 men and 105 women, who were equally divided over the two conditions (N = 42 males and N = 54 females in the narrative condition; N = 43 males and N = 51 females in the inverted pyramid condition). The age of the participants ranged between 18 and 88 years old (mean = 44.43; SD = 18.87). To compare the effects of story structure between people of different ages, three age groups were created. Those with an age ranging between 18 and 34 years old (N = 70; meanage = 23.27; SDage = 2.92; 64.3 percent female) represented the youngest age group (Millennials). People with an age ranging between 35 and 55 years were defined as the middle-aged group (Generation Xers, N = 63; meanage = 46.87; SDage = 4.86; 63.5 percent female). The oldest categories consisted of participants aged 55 and over (N = 57; meanage = 67.72; SDage = 6.86; 35.1 percent female), and together represent the Baby Boomers and Silent Generation. Participants indicated whether they had a low (N = 37), middle (N = 57), or high (N = 89) level of education (the level of education was unknown for seven participants).

Materials

Four news articles were selected from the website of a local newspaper. A number of criteria were applied to select suitable news stories. To diminish the chance that participant responses (e.g. memory scores) were influenced by previous knowledge, only stories reporting about low-impact events were selected. Moreover, only relatively short stories were selected to enhance readability and to diminish the chance of participant dropout. Finally, the stories represented a wide range of topics to ensure that effects of story structure were not topic-related. As a result, the stimulus materials consisted of news stories about a lawsuit, the results of a scientific study, domestic abuse, and a cultural festival.Footnote1

To enhance ecological validity, original news articles were chosen as a basis for developing different versions. Two of the stories were originally written and published in the narrative news structure, the other two in an inverted pyramid structure. The content of each version was the same in terms of characteristics such as topic, events, statements, emotions, information, and characters. For the purpose of the study, a journalist created two new versions of each article, rewriting it in either narrative structure or inverted pyramid structure by making minor changes in the original article and by rewriting it in the alternative structure. Following theoretical notions regarding narrative story structure, the narrative stories presented the information in a chronological order: stories had a clear beginning, middle, and end. In contrast, the inverted pyramid reports started with the most important information and story conclusion, followed by a further contextualization of the news event (cf. Van Dijk Citation1983). In addition, narrative versions were personalized by paraphrasing or quoting the points of view of characters in the stories, whereas in the inverted pyramid versions they were described. As a result, the narrative stories required more words for paraphrasing and linking (ranging from 225 to 332 words) than the inverted pyramid reports (ranging from 187 to 272 words).

A pretest among a number of local newspaper journalists was conducted to test the materials. They read the articles and checked whether they were indeed written in either a narrative structure or an inverted pyramid structure. They agreed that the structure of the stories reflected the study’s intention, implying that we succeeded in presenting each story in two different formats.

Measures

To measure information recognition, 33 true/false statements were presented to the participants. The statements tested the participants’ recognition of the most important aspects of the news stories (who, what, when, where, and why, of the news event; cf. Findahl and Höijer Citation1985). Items included, for instance, the offence for which the women stood trial took place in Arnhem: true/false; the musical festival will be taking place on May 28; the accused is a 54-year-old man from Nijmegen. We chose recognition measures, because recognition is the most sensitive measure of information processing (cf. Lang Citation2000). Depending on the length of the story, the number of questions asked per story ranged between 6 and 11. For the analysis, each correct answer was awarded with one point, whereas failing to recognize the information in the statement correctly resulted in no points. For each news story, a mean recognition score was calculated. The average recognition score was 0.63 (SD = 0.14), indicating that on average 63 percent of the story was correctly recognized.

Appreciation, representing cognitive, reflective affects instead of gratifying needs for fun and pleasure, was measured with a single-item question (cf. Oliver and Bartsch Citation2011). After each news story, participants were asked to indicate their appreciation of the story on a scale ranging from (1) very low appreciation to (10) very high appreciation of the story (mean = 6.63; SD = 0.99). Giving a score on this range is very common for participants in the Netherlands—the country were the study was conducted—as, for instance, grades at schools also range from 1 to 10.

Results

For each dependent variable, a repeated measures mixed ANOVA was carried out in which the four news stories were defined as within-subject variables, and writing style (narrative versus inverted pyramid) and age group (Millennials, Generation Xers, and Baby Boomers/Silent Generation) as between-subjects variables. Although the results showed some minor differences between the four different articles, no clear patterns could be detected. This implies that there was no specific story that may have distorted the results, and we therefore only report the results of the between-subjects variables. In preliminary analyses, we tested for each story separately whether gender and level of education correlated with the dependent variables. This was not the case and there was thus no reason to include gender and level of education as covariates in the model.

Information Processing

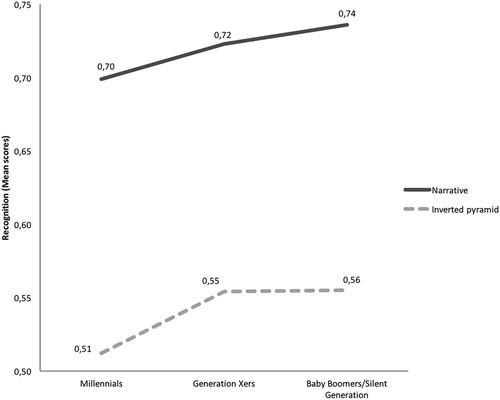

The first hypothesis concerned the main effect of story structure on information processing. As predicted, a narrative story structure (mean = 0.72; SE = 0.01) leads to better information processing than a story written in the inverted pyramid structure (mean = 0.54; SE = 0.01), F(1, 184) = 126.018; p < 0.001; r = 0.64. There was no main effect of age (p = 0.089) and no interaction between age and story structure (p = 0.884). This implies that participants representing Millennials, Generation Xers, and Baby Boomers/Silent Generation had comparable recognition scores. As shown in , they all processed information derived from the narrative news stories better. We therefore found an answer to the first research question: Millennials did not benefit more from narrative stories in terms of information processing compared to the older generations. Instead, all generations benefit from a narrative story structure in terms of information processing.

Appreciation

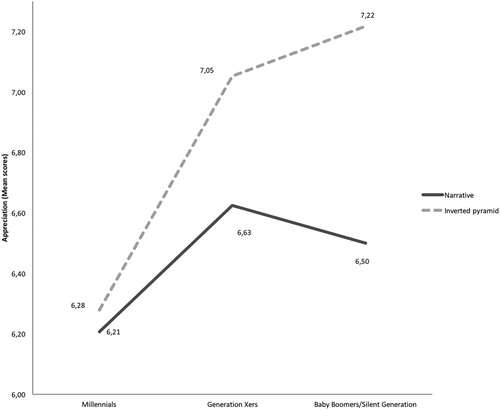

H2 predicted that narrative news would be appreciated more than stories written in the inverted pyramid style. As the results showed exactly the opposite, this hypothesis was rejected. The inverted pyramid reports were more appreciated (mean = 6.85; SE = 0.10) than the narrative stories (mean = 6.44; SE = 0.10), F(1, 184) = 8.86; p = 0.003; r = 0.21. In addition, a main effect of age was found, F(2, 184) = 9.29; p < 0.001; r = 0.22. Post-hoc analyses showed that the Millennials (mean = 6.24; SE = 0.11) had a lower appreciation of news stories than the Generation Xers (p = 0.001) and Baby Boomers/Silent Generation participants (p = 0.001). The difference between the Generations Xers (mean = 6.84; SE = 0.12) and Baby Boomers/Silent Generation (mean = 6.86; SE = 0.12) was not significant (p = 0.943).

The interaction between age and story structure did not reach significance (F(2, 184) = 6.622; p = 0.152), but post-hoc analyses revealed some interesting differences in light of H3. Millennials appreciated both narrative structure and inverted pyramid reports equally low (p = 0.749), whereas Generation Xers (p = 0.072) and Baby Boomers/Silent Generation participants (p = 0.004) tended to appreciate particularly the inverted pyramid reports more. In addition, Millennials had a significantly lower appreciation of the stories written in the inverted pyramid structure than Generation Xers (p = 0.001) and Baby Boomers/Silent Generation participants (p < 0.001). As illustrated in , the narrative story structure is not a convenient strategy to attract the young audience, nor is it able to attract the middle-aged and older readers. In all, the results do not provide support for H3.

Discussion

The current study investigated whether narrative news stories can be a meaningful strategy to inform and attract younger audiences to the news, while at the same time at the very least retaining the same qualities for older audiences. What did our results contribute to obtaining clarity on this much-advocated solution? First, narrative news stories do seem superior to news in the inverted pyramid on one important aspect. People from all ages are better informed by reports using a narrative format, at least in situations when background knowledge cannot be used, or is irrelevant. This concurs with previous research and may be seen as an important recommendation to use the narrative form in transferring information. In practice it means that news users, young and old, are more likely to learn current events knowledge from narrative news. In other words, narrative news may serve democratic citizens better than traditional news formats.

However, in terms of attracting audiences, the narrative form may not live up to its expectations. In contrast to earlier studies, participants from all ages in the current study had lower appreciation for the narrative news stories compared to the inverted pyramid reports. What is more, the younger audiences (i.e. Millennials) have a lower appreciation for all news reports compared to the two older generations, regardless of whether the reports are presented in a narrative or inverted pyramid structure. A potential explanation may be differential news preferences between generations. Growing up with inverted pyramid news has made this format the norm for serious news in the eyes of the older generations. This means that narrative news is not appreciated, whether or not it leads to increased transportation: it simply does not fit the typical “serious” news format. For the youngest generation, the explanation may be that they do not like serious news, full stop. Restructuring the news report does not do the trick, because it is still news.

This points to another important issue: in the current study, narrative structure was manipulated by changing the order of the news report to chronological and giving a more central role to the characters’ perspective by means of quotes. Other studies, particularly in entertainment-education research, have used broader definitions and operationalizations of narratives, including motivational and emotional storytelling, problem solving, conflict, and the temporality of existence (cf. Braddock and Dillard Citation2016). While not all of these elements may be relevant for news reporting, future research should investigate the effects of several narrative elements separately in order to shed more light on whether and how those specific elements may contribute to both the attractiveness and informative value of news.

In all, the results of this study do not necessarily bode well for the narrative structure as a successful strategy for attracting audiences, be they young or old. Indeed, the increase in narrative journalism may be a risky affair, as it may even alienate older generations of news users. However, for newsmakers aiming solely at younger audiences, there may yet be some hope to derive from the present study. As seen, among the Millennials appreciation of narrative news was equally low compared to the inverted pyramid reports. However, because the narrative format is superior in terms of learning, in the longer run this may lead to young people having improved background knowledge, which may then turn out useful for them as informed citizens. Ultimately, greater knowledge may lead to developing a greater interest in any kind of news topic because they are more likely to understand them, leading to a “virtuous circle” of knowledge gain, news interests, and news consumption (Norris Citation2000). So when looking at the younger generation only, narrative news may ultimately be the better choice.

In this context, it is important to note that the current study focuses on written news. Although presented in an internet environment, online news usually shows many similarities with traditional newspaper articles. This traditional presentation is probably not preferred by younger audiences, as the appreciation scores also tend to indicate. It is therefore worth exploring whether narrative journalism on other media platforms, or using different modalities to tell a story—audiovisual formats, social networking sites—is better suited to serve Millennials. Data from the Pew Research Center (Citation2012, Citation2016) suggest that younger audiences prefer such media outlets for getting news, most likely because new information and communication technologies are increasingly present in their lives (Livingstone and Helsper Citation2007). In particular, the rise of news on social networking sites can be seen as a promising development in light of the importance of getting youngsters involved in news. It is therefore interesting for future research to assess whether the inclusion of narrative structures in such newer news formats may enhance youngsters’ involvement in the news.

Differences in attitudes towards news topics may also play a role in this regard. Prior research has shown that young people have different interests from older generations. For instance, Millennials are less interested in political news, but they tend to prefer negative news more than older generations (e.g. Kleemans et al. Citation2012; Pew Research Center Citation2012). Moreover, Costera Meijer (Citation2007) shows that youngsters want news that can serve as a basis for conversation, provide inspiration, or add something to their life. As the current study consciously presented a wide range of topics, but nothing that was particularly relevant for a certain age group, one might wonder how other topics may affect audience responses. Future research should therefore investigate if narrative news stories on topics of higher personal relevance for a particular age group have other effects than traditional news reports.

Our measurement of appreciation was limited to a single item. Research on enjoyment and appreciation of entertainment content has only recently disentangled the concepts theoretically and empirically (Lewis, Tamborini, and Weber Citation2014; Oliver and Bartsch Citation2010, Citation2011; Oliver and Woolley Citation2010; Tamborini et al. Citation2011; Vorderer, Klimmt, and Ritterfeld Citation2004). Although there is evidence that single-item measurement of appreciation is valid (Oliver and Bartsch Citation2010), conceptually appreciation is more complex. In entertainment research, appreciation is correlated to content focusing on human virtue and life’s purpose, eliciting feelings of inspiration, awe, and tenderness (Oliver and Bartsch Citation2011). However, it is unclear whether this complex conceptualization and corresponding measurement are directly transferable to a news and information setting. Relevant future research may be directed towards further developing the concept and measurements in regard to non-entertainment content. Meanwhile, this study represents a first attempt to explore news evaluations beyond sheer “liking”.

On a general level, this study’s contribution is in the field of age differences in the effects of mediated messages. Although age is routinely included as a control variable in communication research, and much media effects research is done on specific age groups—most notably children and adolescents—research on the role of age differences in media effects is relatively scarce. To conclude, this study shows that there are still major challenges for journalists and scholars on the road to enhancing the relationship between youngsters and the news. As news consumption is an important prerequisite for the functioning of democracy, this question deserves high priority.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. Materials are available from the authors upon request.

REFERENCES

- Aalberg, Toril, Arild Blekesaune, and Eiri Elvestad. 2013. “Media Choice and Informed Democracy: Toward Increasing News Consumption Gaps in Europe?” The International Journal of Press/Politics 18 (3): 281–303. doi: 10.1177/1940161213485990

- Abrahamson, David. 2006. “The Problem with Sources, A Source of the Problem.” Journal of Magazine and New Media Research 9 (1): 1–6. http://www.bsu.edu/web/aejmcmagazine/archive/Fall_2006/Sources_problem.pdf.

- Berinsky, Adam J., and Donald R. Kinder. 2006. “Making Sense of Issues Through Media Frames: Understanding the Kosovo Crisis.” The Journal of Politics 68 (3): 640–656. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2508.2006.00451.x.

- Bilandzic, Helena, and Rick W. Busselle. 2008. “Transportation and Transportability in the Cultivation of Genre-Consistent Attitudes and Estimates.” Journal of Communication 58 (3): 508–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.00397.x

- Bilandzic, Helena, and Rick Busselle. 2013. “Narrative Persuasion.” In The Sage Handbook of Persuasion: Developments in Theory and Practice, edited by James Price and Lijiang Shen, 200–219. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Braddock, Kurt, and James Price Dillard. 2016. “Meta-Analytic Evidence for the Persuasive Effect of Narratives on Beliefs, Attitudes, Intentions, and Behaviors.” Communication Monographs 83 (4): 446–467. doi: 10.1080/03637751.2015.1128555

- Britton, Bruce K., Arthur C. Graesser, Shawn M. Glynn, Tom Hamilton, and Margaret Penland. 1983. “Use of Cognitive Capacity in Reading: Effects of Some Content Features of Text.” Discourse Processes 6 (1): 39–57. doi: 10.1080/01638538309544553

- Busselle, Rick, and Helena Bilandzic. 2009. “Measuring Narrative Engagement.” Media Psychology 12 (4): 321–347. doi: 10.1080/15213260903287259

- Chaffee, Steven H. 1973. “Applying the Interpersonal Perception Model to the Real World: An Introduction.” The American Behavioral Scientist (pre-1986) 16 (4): 465–468. doi: 10.1177/000276427301600401

- Costera Meijer, Irene. 2007. “The Paradox of Popularity: How Young People Experience the News.” Journalism studies 8 (1): 96–116. doi: 10.1080/14616700601056874

- Curran, James, Sharon Coen, Toril Aalberg, and Shanto Iyengar. 2012. “News Content, Media Consumption, and Current Affairs Knowledge.” How Media Inform Democracy: A Comparative Approach 1: 81–97.

- Delli Carpini, Michael X., and Scott Keeter. 1996. What Americans Know About Politics and Why it Matters. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Diamond, Adele. 2013. “Executive Functions.” Annual Review of Psychology 64: 135–168. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750

- Donsbach, Wolfgang. 2011. “News Exposure and News Knowledge of Adolescents. Final Report.” Accessed March 10, 2017.

- Emde, Katharina, Christoph Klimmt, and Daniela M. Schluetz. 2016. “Does Storytelling Help Adolescents to Process the News? A Comparison of Narrative News and the Inverted Pyramid.” Journalism Studies 17 (5): 608–627. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2015.1006900

- Findahl, Olle, and Brigitta Höijer. 1985. “Some Characteristics of News Memory and Comprehension.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 29 (4): 379–396. doi: 10.1080/08838158509386594

- Frieske, David A., and Denise C. Park. 1999. “Memory for News in Young and Old Adults.” Psychology and Aging 14 (1): 90–98. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.14.1.90

- Fry, Don. 1999. “Writers Should Avoid the Perverted Pyramid.” American Editor 74 (4): 24–25.

- Galston, William A. 2001. “Political Knowledge, Political Engagement, and Civic Education.” Annual Review of Political Science 4 (1): 217–234. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.4.1.217

- Galston, William A. 2007. “Civic Knowledge, Civic Education, and Civic Engagement: A Summary of Recent Research.” International Journal of Public Administration 30 (6-7): 623–642. doi: 10.1080/01900690701215888

- Green, Melanie C., Timothy C. Brock, and Geoff F. Kaufman. 2004. “Understanding Media Enjoyment: The Role of Transportation Into Narrative Worlds.” Communication Theory 14 (4): 311–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2004.tb00317.x

- Hill, Robert D., Thomas H. Crook, Anastasia Zadek, Javaid Sheikh, and Jerome Yesavage. 1989. “The Effects of Age on Recall of Information From a Simulated Television News Broadcast.” Educational Gerontology: An International Quarterly 15 (6): 607–613. doi: 10.1080/0380127890150605

- Høyer, Svennik, and Hedda A. Nossen. 2015. “Revisions of the News Paradigm: Changes in Stylistic Features Between 1950 and 2008 in the Journalism of Norway’s Largest Newspaper.” Journalism 16 (4): 536–552. doi: 10.1177/1464884914524518

- Johnson-Laird, Philip Nicholas. 1983. Mental Models: Towards a Cognitive Science of Language, Inference, and Consciousness. No. 6. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Johnston, Jane. 2007. “Turning the Inverted Pyramid Upside Down: How Australian Print Media is Learning to Love the Narrative.” Asia Pacific Media Educator 1 (18): 1–15.

- Kintsch, Walter. 1988. “The Role of Knowledge in Discourse Comprehension: A Construction-Integration Model.” Psychological Review 95 (2): 163–182. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.95.2.163

- Kintsch, Walter, and Teun A. Van Dijk. 1978. “Toward a Model of Text Comprehension and Production.” Psychological Review 85 (5): 363–394. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.85.5.363

- Kleemans, Mariska, Paul G. J. Hendriks Vettehen, Johannes W. J. Beentjes, and Rob Eisinga. 2012. “The Influence of Age and Gender on Preferences for Negative Content and Tabloid Packaging in Television News Stories.” Communication Research 39 (5): 679–697. doi: 10.1177/0093650211414559

- Knobloch, Silvia, Grit Patzig, Anna-Maria Mende, and Matthias Hastall. 2004. “Affective News Effects of Discourse Structure in Narratives on Suspense, Curiosity, and Enjoyment While Reading News and Novels.” Communication Research 31 (3): 259–287. doi: 10.1177/0093650203261517

- Knobloch-Westerwick, Silvia. 2014. Choice and Preference in Media Use: Advances in Selective Exposure Theory and Research. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Kramer, Mark. 2000. “Narrative Journalism Comes of Age.” Nieman Reports 54 (3): 5–8.

- Lang, Annie. 1989. “Effects of Chronological Presentation of Information on Processing and Memory for Broadcast News.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 33 (4): 441–452.

- Lang, Annie. 2000. “The Limited Capacity Model of Mediated Message Processing.” Journal of Communication 50 (1): 46–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2000.tb02833.x

- Lang, Annie. 2006. “Using the Limited Capacity Model of Motivated Mediated Message Processing to Design Effective Cancer Communication Messages.” Journal of communication 56 (s1): S57–S80. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00283.x

- Lang, Annie, Deborah Potter, and Maria Elizabeth Grabe. 2003. “Making News Memorable: Applying Theory to the Production of Local Television News.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 47 (1): 113–123. doi: 10.1207/s15506878jobem4701_7

- Leary, Mark R., and Nicole R. Buttermore. 2003. “The Evolution of the Human Self: Tracing the Natural History of Self-Awareness.” Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 33 (4): 365–404. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-5914.2003.00223.x

- Lee, Angela M., and M. X. Delli Carpini. 2010. “News Consumption Revisited: Examining the Power of Habits in the 21st Century.” In 11th International Symposium on Online Journalism, Austin, TX 23 (24): 1–32.

- Lewis, Robert J., Ron Tamborini, and René Weber. 2014. “Testing a Dual-Process Model of Media Enjoyment and Appreciation.” Journal of Communication 64 (3): 397–416. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12101

- Livingstone, Sonia, and Ellen Helsper. 2007. “Gradations in Digital Inclusion: Children, Young People and the Digital Divide.” New Media & Society 9 (4): 671–696. doi: 10.1177/1461444807080335

- Machill, Marcel, Sebastian Köhler, and Markus Waldhauser. 2007. “The Use of Narrative Structures in Television News: An Experiment in Innovative Forms of Journalistic Presentation.” European Journal of Communication 22 (2): 185–205. doi: 10.1177/0267323107076769

- Marchi, Regina. 2012. “With Facebook, Blogs, and Fake News, Teens Reject Journalistic “Objectivity”.” Journal of Communication Inquiry 36 (3): 246–262. doi: 10.1177/0196859912458700

- Mindich, David T. Z. 2000. Just the Facts: How “Objectivity” Came to Define American Journalism. New York, NY: NYU Press.

- Mindich, David T. Z. 2005. Tuned Out: Why Americans Under 40 Don’t Follow the News. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Nabi, Robin L., and Marina Krcmar. 2004. “Conceptualizing Media Enjoyment as Attitude: Implications for Mass Media Effects Research.” Communication Theory 14 (4): 288–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2004.tb00316.x

- Norris, Pippa. 2000. A Virtuous Circle: Political Communications in Postindustrial Societies. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- Oliver, Mary Beth, and Anne Bartsch. 2010. “Appreciation as Audience Response: Exploring Entertainment Gratifications Beyond Hedonism.” Human Communication Research 36 (1): 53–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2009.01368.x

- Oliver, Mary Beth, and Anne Bartsch. 2011. “Appreciation of Entertainment.” Journal of Media Psychology 23: 29–33. doi: 10.1027/1864-1105/a000029

- Oliver, Mary Beth, James Price Dillard, Keunmin Bae, and Daniel J. Tamul. 2012. “The Effect of Narrative News Format on Empathy for Stigmatized Groups.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 89 (2): 205–224. doi: 10.1177/1077699012439020

- Oliver, Mary Beth, and Julia K. Woolley. 2010. “Tragic and Poignant Entertainment: The Gratifications of Meaningfulness.” In Handbook of emotions and mass media, edited by K. Döveling, C. von Scheve, and E. Konijn, 134–147. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Park, Denise C., Anderson D. Smith, Gary Lautenschlager, Julie L. Earles, David Frieske, Melissa Zwahr, and Christine L. Gaines. 1996. “Mediators of Long-Term Memory Performance Across the Life Span.” Psychology and Aging 11 (4): 621–637. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.11.4.621

- Patterson, Thomas E. 2007. Young People and News: A Report From The Joan Shorenstein Center on The Press, Politics, and Public Policy. Cambridge, MA: John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University.

- Pew Research Center for People and the Press. 2012. “In Changing News Landscape, Even Television ss Vulnerable. Trends in News Consumption: 1991–2012.” Accessed March 10, 2017.

- Pew Research Center for People and the Press. 2016. “The Modern News Consumer: News Attitudes and Practices in the Digital Era.” Accessed March 10, 2017.

- Phillips, Lynn W., and Brian Sternthal. 1977. “Age Differences in Information Processing: A Perspective on The Aged Consumer.” Journal of Marketing Research 14: 444–457. doi: 10.2307/3151185

- Pöttker, Horst. 2003. “News and its Communicative Quality: The Inverted Pyramid—When and Why Did it Appear?” Journalism Studies 4 (4): 501–511. doi: 10.1080/1461670032000136596

- Quintero Johnson, Jessie M., and Angeline Sangalang. 2016. “Testing the Explanatory Power of Two Measures of Narrative Involvement: An Investigation of the Influence of Transportation and Narrative Engagement on the Process of Narrative Persuasion.” Media Psychology 20: 144–175. doi: 10.1080/15213269.2016.1160788

- Ramscar, Michael, Peter Hendrix, Cyrus Shaoul, Petar Milin, and Harald Baayen. 2014. “The Myth of Cognitive Decline: Non-Linear Dynamics of Lifelong Learning.” Topics in Cognitive Science 6 (1): 5–42. doi: 10.1111/tops.12078

- Rodríguez, María José González. 2004. “Between Narrative and Non-Narrative: Make Up of the News Story.” Revista Canaria de Estudios Ingleses 49: 135–156.

- Rogers, Tony. 2010. “The Technology of Journalism Improves, But Young People Still Ignore the News: Is There Enough Emphasis on Attracting the Next Generation of Readers and Viewers?” http://journalism.about.com/od/trends/a/youngpeople.htm.

- Salthouse, Timothy A. 2016. Theoretical Perspectives on Cognitive Aging. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Sangalang, Angeline, Jessie M. Quintero Johnson, and Kate E. Ciancio. 2013. “Exploring Audience Involvement with an Interactive Narrative: Implications for Incorporating Transmedia Storytelling Into Entertainment-Education Campaigns.” Critical Arts 27 (1): 127–146. doi: 10.1080/02560046.2013.766977

- Schank, Roger C., and Robert P. Abelson. 1995. “Knowledge and Memory: The Real Story.” Advances in Social Cognition 8: 1–85.

- Schudson, Michael. 1982. “The Politics of Narrative Form: The Emergence of News Conventions in Print and Television.” Daedalus 111: 97–112.

- Schudson, Michael. 2005. “News as Stories.” In Media Anthropology, edited by Mihai Coman and Eric W. Rothenbuhler, 121–128. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Shim, Hoon. 2014. “Narrative Journalism in the Contemporary Newsroom: The Rise of New Paradigm in News Format?” Narrative Inquiry 24 (1): 77–95. doi: 10.1075/ni.24.1.04shi

- Sternadori, Miglena M., and Kevin Wise. 2010. “The Effects of Story Structure on the Cognitive Processing of Text.” Journal of Media Psychology 22 (1): 14–25. doi: 10.1027/1864-1105/a000003

- Stine, Elizabeth Ann Lotz, Arthur Wingfield, and Sheldon D. Myers. 1990. “Age Differences in Processing Information From Television News: The Effects of Bisensory Augmentation.” Journal of Gerontology 45 (1): P1–P8. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.1.P1

- Tamborini, Ron, Matthew Grizzard, Nicholas David Bowman, Leonard Reinecke, Robert J. Lewis, and Allison Eden. 2011. “Media Enjoyment as Need Satisfaction: The Contribution of Hedonic and Nonhedonic Needs.” Journal of Communication 61 (6): 1025–1042. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01593.x

- Tulving, Endel. 1979. “Relation Between Encoding Specificity and Levels of Processing.” In Levels of Processing in Human Memory, edited by Laird S. Cermak and Fergus I. Craik, 405–428. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Tulving, Endel. 2002. “Episodic Memory: From Mind to Brain.” Annual Review of Psychology 53 (1): 1–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135114

- Turel, Ofir, and Alexander Serenko. 2012. “The Benefits and Dangers of Enjoyment with Social Networking Websites.” European Journal of Information Systems 21 (5): 512–528. doi: 10.1057/ejis.2012.1

- Van Dijk, Teun A. 1983. “Discourse Analysis: Its Development and Application to the Structure of News.” Journal of Communication 33 (2): 20–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1983.tb02386.x

- Vorderer, Peter, Christoph Klimmt, and Ute Ritterfeld. 2004. “Enjoyment: At the Heart of Media Entertainment.” Communication Theory 14 (4): 388–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2004.tb00321.x

- Vorderer, Peter, Silvia Knobloch, and Holger Schramm. 2001. “Does Entertainment Suffer From Interactivity? The Impact of Watching an Interactive TV Movie on Viewers’ Experience of Entertainment.” Media Psychology 3 (4): 343–363. doi: 10.1207/S1532785XMEP0304_03

- Wayne, Mike, Julian Petley, Craig Murray, and Lesley Henderson. 2010. Television News, Politics and Young People: Generation Disconnected? New York, NY: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Wise, Kevin, Paul Bolls, Justin Myers, and Miglena Sternadori. 2009. “When Words Collide Online: How Writing Style and Video Intensity Affect Cognitive Processing of Online News.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 53 (4): 532–546. doi: 10.1080/08838150903333023

- Yaros, Ronald A. 2006. “Is It the Medium or the Message? Structuring Complex News to Enhance Engagement and Situational Understanding by Nonexperts.” Communication Research 33 (4): 285–309. doi: 10.1177/0093650206289154

- York, Chance. 2013. “Overloaded by the News: Effects of News Exposure and Enjoyment on Reporting Information Overload.” Communication Research Reports 30 (4): 282–292.

- Ytreberg, Espen. 2001. “Moving out of the Inverted Pyramid: Narratives and Descriptions in Television News.” Journalism Studies 2 (3): 357–371. doi: 10.1080/14616700118194

- Zerba, Amy. 2008. “Narrative Storytelling: Putting the Story Back in Hard News to Engage Young Audiences.” Newspaper Research Journal 29 (3): 94–102. doi: 10.1177/073953290802900308

- Zwaan, Rolf A., Joseph P. Magliano, and Arthur C. Graesser. 1995. “Dimensions of Situation Model Construction in Narrative Comprehension.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 21 (2): 386–397.