Abstract

Journalism's appeal to the public is in decline and the causes and remedies for this are debated in society and academia. One dimension that has garnered attention is that of journalistic norms and how they are performed; it has been proposed that a journalism based on a different, more transparent, normative base can better connect with citizens, compared with the current prevailing norm of journalistic objectivity. However, the opinions of citizens themselves have been remarkably absent and, in order to inform the debate, this study inductively investigates how citizens view and relate to the notion of good journalism. Drawing upon a theoretical framework of Bourdieu's concept of doxa, journalistic role performance, and social contract theory, this study is based on the results of 13 focus groups. The findings suggest that the respondents’ views about good journalism are quite in accordance with the traditional norms of the journalistic field; however, there is more emphasis on stylistic and linguistic qualities. Few calls are made for transparency. The results suggest that a remedy to the decreasing trust in news may not lay in the changing of norms, but rather in how already established norms and values of the journalistic field are performed.

Introduction

Journalism is not just any form of information production; it is associated with certain skills, practices and norms, and role orientations and performances (Mellado Citation2015; Hanitzsch and Vos Citation2017), that separate it from other genres (Schudson Citation2001). However, as research has shown, the norms of journalism varies with time and space (Hanitzsch et al. Citation2011) and is ultimately socially constructed as research based on Social Contract Theory (SCT) illustrates (Wilkins Citation1990; Ward Citation2005; Sjøvaag Citation2010; Merrill Citation2011). Currently, the social contract regarding journalism is under pressure as the public's attention to and trust in news media is in decline (van der Wurff and Schoenbach Citation2014). The decline is deeply problematic for the journalistic field where trust and credibility are constitutive; without these, the public will turn to other sources for information (Flanagin and Metzger Citation2007; Kohring and Matthes Citation2007). Viewed from an SCT perspective, the decrease in trust from the public can be interpreted as a mismatch between what the public expects from journalism and what journalism delivers, suggesting that the contractual ties are weakened or even dissolving. When that happens, journalism needs to discursively renegotiate its role orientations, performances and relationships with the public and other actors (Hanitzsch and Vos Citation2017). Some observers suggest that changing to a more transparent way of doing news could possibly counter the trend and, instead, be a remedy to restore and even increase the trust and credibility of journalism (Karlsson Citation2010; Plaisance Citation2007; Vos and Craft Citation2017; Chadha and Koliska Citation2015). However, in most discussions about the viability of different journalistic role orientations and performances (although see Coleman, Morrison, and Anthony Citation2012 for a notable exception), a crucial part of the puzzle is regularly overlooked – the views of the public and how they understand and evaluate journalism. Through the use of 13 focus groups (n=82), this study uses an inductive approach to investigate the public's understanding of what constitutes, in broad terms, good journalism.

Journalistic Doxa, Role Performances and Relationships with the Public

There are firm opinions about what journalism really is or, put in the setting of this study, socially appropriate forms of journalistic performance. In this context, the Bourdieuan concept of doxa (Bourdieu Citation2005; Schultz Citation2007) is helpful because it points to the tacit presuppositions and values that are considered to be the ultimate or natural way to construct the world, seeking to be recognised by others (politicians, academics or, as in our case, the public) as “legitimate categories of construction of the social world” (Bourdieu Citation2005, 37). The establishment of the proper categories of journalism also helps define what actors and behaviours are “in” or “out” of the journalistic field. But the implementation and legitimacy of the doxa faces at least two challenges. First, the doxa has to be, somehow, put into practice by members of the field (e.g. journalists) in ways that can be observed and recognised as such by both insiders and outsiders of the field. Members of the field must also avoid engaging in anti-doxic behaviours because this would compromise the doxa and themselves. Second, the doxa is not a constant, but varies across space and time meaning that the “natural” and, thus, the only way of performing journalism will vary. This leads to situations where previously ortodoxic norms and performances become heterodoxic and vice versa, with consequences for how journalism can be legitimised vis-à-vis various actors. Bourdieu's theoretical framework is primarily constituted to understand and explain the production side of journalism and the reproduction of status and position in and between different social fields (e.g. political, economic, and journalistic). It is configured less to investigate how the doxa is actually performed and how members of the public, with some degree of autonomy and agency of their own, identify and evaluate legitimate doxic practices (e.g. Benson and Neveu Citation2005). In order to be better able to detail the struggle between the journalistic field and the social field in which the public resides, we draw from other theoretical frameworks that help analyse the two challenges outlined above: namely, journalistic role performance and SCT.

Starting with the former, theories about journalistic roles are helpful as they allow to investigate how more abstract doxic values are converted into observable ways of how individuals and institutions are performing, thinking, and arguing about journalism, in a public space (e.g. news media) in order to achieve legitimacy (Mellado Citation2015; Hanitzsch and Vos Citation2017). In short, journalistic role performance is concerned with the ties between norms and daily practice (Mellado Citation2015) which also enables the public to see the doxa in practice. Members of the field define and defend the borders by performing certain strategic rituals (Tuchman Citation1972; BLINDED) through, for instance, verification, use of multiple sources, and identifying conflicts between different actors. When the established borders are transgressed, the paradigm needs to be discursively repaired in public (Bennett, Gresset, and Haltom Citation1985), denouncing deviant behaviour and ensuring that old familiar rules still apply.

When researchers are investigating journalistic role performance from the perspective of journalists and audiences, they are simultaneously: examining the doxa; detailing doxic criteria against which journalism should be evaluated; and, arguably, making a case for the doxa and how it should be manifested. Research that investigates role performance for journalists, then, will effectively put forth a catalogue of dimensions of the doxa in practice. Indeed, research in the field has pointed out some dimensions that are emphasised and are widespread. Some of the well-known dimensions include being a watchdog of the government, providing useful information for citizens, impartiality, detachment, keeping journalists’ personal views out of reporting, verifying information, and following universal principles regardless of the circumstances (Schudson Citation2001; Hanitzsch et al. Citation2011; Mellado Citation2015). Moreover, these journalistic role conceptions also overlap, almost to the point of being identical, with the ethical guidelines of professional organisations, such as the Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ) in the US and “Rules for the press, radio and television” by the Swedish Union of Journalists in Sweden (the country of our study). With this in mind, it is only logical that members of the journalistic and academic fields try to nail down the true – or doxic – elements of journalism in a 10-point list (e.g. Kovach and Rosenstiel Citation2007).

Despite the existence of 10-point lists and a cohesive professional and scholarly understanding of what constitutes proper journalistic role performance, journalism is less stable than it appears since, as Hanitzsch and Vos (Citation2017, 129) point out, “Journalism and journalistic roles have no ‘true’ essence; they exist because and as we talk about them”. This highlights the dialogical and unsettled foundations of journalism or, to paraphrase Carlson (Citation2017), the complex social relations through which journalism possesses and exercises authority, in turn pointing towards journalism as a social contract, where different actors (e.g. the public) have some autonomy and agency to determine “the terms of their association” (Merrill Citation2011, 26). Moreover, in order for the social contract to function, there needs to be consent between the different actors involved, but the contract must also be flexible enough to allow for changes and heterogeneity of many journalistic forms. Thus, journalisms societal role is subjected to an ongoing public negotiation and re-negotiation between the journalists themselves and various stakeholders (Wilkins Citation1990; Ward Citation2005; Sjøvaag Citation2010; Merrill Citation2011). Hence, as pointed by Schudson (Citation2001) discussing the emergence of objectivity (i.e. its introduction into the field of journalism as a legitimate practice) as a new norm, the establishment of norms involves a process of asking for public approval.

From a SCT standpoint, there needs to be an agreement between, for example, the journalists, the state and the citizens on the role of journalism in society and the role performance of journalists. Using Bourdieu's nomenclature, it can be argued that all actors involved need to share a basic understanding of journalism's doxa in order for it to be perceived as legitimate. The doxa (and its components and expressions) cannot be upheld if it is not seen as a legitimate way of socially constructing the world. Differences between expectations and performances are likely to result in a doxic gap. Importantly, Bourdieu (Citation2005) considers the autonomy of the journalistic field to be low, implying that the doxa is rather susceptible to change through pressure from other fields such as, in our case, the social field in which the Swedish public reside. A recent example of change in journalistic doxa is the increased emphasis on transparency by both scholars and, as a recent review of changes to SPJ's code of conduct shows (Vos and Craft Citation2017), professional journalists.

To summarise, good journalism from the public's perspective can be understood as a performance, in accordance with doxa (or script, to stick with the performance metaphor), by an actor on a stage presented as a journalistic venue, which will be evaluated based on the public's understanding of said performance, doxa, actors, and stage. The scholarly debate so far has centred on the performance, actors, doxa, and stage – asking how far from hard news, which is processed according to ideals of objectivity and presented by a professionally trained journalist in a traditional news outlet, can journalism stray before it ceases to be journalism – rather than the reception of the play. However, citizens are key spectators and evaluators of journalistic role performance and constitute a principal part of journalism's social contract who can “either challenge or reinforce the doxa and cultural capital of the journalistic field” (Craft, Vos, and David Wolfgang Citation2016, 680; see also Carlson Citation2017). In this context, it is perplexing that citizens are commonly left out of the discussion altogether of what journalism can and should be (van der Wurff and Schoenbach Citation2014). While the public have rarely been asked what they perceive to be pertinent norms, values, and performances in journalism, there are some exceptions reviewed next.

Journalistic Role Performance and the Public

While there is little research on audience perspectives on what comprises good journalism (e.g. adequate journalistic performance), there are some exceptions.

Scholars have mainly used two methodological approaches to tap into how the public views journalism – surveys and mixed methods (e.g. interviews, focus groups, observations). The surveys start from a predetermined, fixed and a priori conception of what constitutes good journalism. Citizens have been asked to tick boxes related to how well journalism performs or about their attitudes towards predefined dimensions of “good” journalism. However, these lines of investigation are impregnated with the risk of “trigger effects”; i.e. certain characteristics are deemed important because they have been prompted by the studies themselves (e.g. the survey questions).

This kind of research conducted in Holland (van der Wurff and Schoenbach Citation2014; van der Wurff and Schönbach Citation2014), Israel (Tsfati, Meyers, and Peri Citation2006), and the US (Gil de Zúñiga and Hinsley Citation2013) has used surveys to ask about people's attitudes towards journalistic norms and performances. The results show that the public's expectations were rather aligned with those of journalists and experts. A study (Craft, Vos, and David Wolfgang Citation2016) investigating reader comments on ombudsman columns found that traditional values such as objectivity were still strong, suggesting stability in the field. However, the study also noted that there were newer, what the authors label “social”, criteria for criticism where journalists were considered to be pompous, sloppy, self-absorbed, and dehumanising.

To the best of our knowledge, there are three studies that approach the issue from a more qualitative and inductive approach seeking the perspectives of citizens. Costera Meijer (Citation2012, Citation2003) has studied valuable journalism from the perspective of news users finding that news user participation can make for a “[…] more truthful, multi-vocal journalism” (766), suggesting that (good) journalism should be truthful and have room for a multiplicity of voices. Nielsen (Citation2016) used the concept of folk theories of journalism as a way of understanding how people relate to journalism. Nielsen shows that people consider it important to keep themselves informed about current affairs (in this case, local current affairs), and they (some) view the newspaper as an important way to keep society together. From this, we can infer that (good) journalism should inform the public about current (local) affairs, and it should function as a social glue, keeping society together. The study that has perhaps best probed how citizens understand good journalists are Coleman and colleagues (Citation2012) found that their focus groups participants believed news to be a hybrid of useful, reliable, and amusing information. Conversely, the respondents found journalism failing when the news stories were not adequately explained and researched.

Since the public's view of good journalism is fundamental to journalism's social contract, the journalistic doxa and, in turn, the journalistic performance that is considered legitimate, we need to address this gap and gain knowledge about the public's view. Against this background, the broad question guiding this study is: What are Swedish citizen's opinions about what constitutes good journalism?

An Inductive Approach to Studying Citizen's Views on Journalistic Norms

In an effort to gain an understanding of audiences’ perceptions about what constitutes good journalism, this study used an open approach with focus groups, where the respondents were asked open-ended questions such as “What are your thoughts when I say ‘news’?”. The data comes from a larger research project about transparency and credibility in online news. For the study, we used 13 focus groups, with a total of 82 respondents drawn from a representative sample of the Swedish population in the age range 18–74 (average age=45). The process for recruiting participants included a screening survey which focused on news consumption (high or low) and trust in journalism and the media (high or low) and there were at least three focus groups of each combination (e.g. high consumption and high trust, low consumption and high trust, and so on). This was done to ensure that the topic had input from a variety of perspectives – from news fans to news critics, from news junkies to news avoiders – and also allowed comparisons between the groups. The focus group sessions were conducted in collaboration with TNS Sifo (a Swedish polling institute), with professional moderators following a line of questioning developed by the researchers. The sessions took place in the cities of Stockholm (at TNS Sifo) and Karlstad (in a conference room at a hotel). Each session lasted at least 90 minutes and one of the researchers monitored the sessions via a live feed (after eight sessions we saw that the sessions ran as expected and that the virtual presence of the researcher was not necessary). All sessions were recorded using both video and audio, and they were also transcribed for further analysis using NVivo software.

In line with Krueger and Casey (Citation2009), we wanted to “promote self-disclosure among participants”. Consequently, the sessions started with broad questions about, for example, news consumption, in order to get all the participants talking and feeling somewhat comfortable in the group. The first question was to ask each participant to present him-/herself. This was followed by the question “If I say ‘news’, what do you think about?”. This was followed by questions about what types of news (if any) the respondents consume, which outlets they used most frequently, if they had any favourite journalist, and why (the question “why” gave some information pertaining to what they considered to be “good journalism”). The explicit question about “good journalism” was introduced some 20–30 minutes into the discussions, after some conversation about the other questions; this allowed for an open and broad discussion about journalism and its norms. After a general discussion about what good journalism is, each of the respondents were asked to write down five thoughts on post-it notes that, in their view, constituted or were affiliated with good journalism. The respondents were then asked to group all post-it notes into stacks as they saw fit and label each of the stacks with terms of their choice, such as “integrity” or “proper presentation and relevance”. After that, the labels and contents of all the stacks were elaborated and discussed in terms of how and why they were connected to good journalism.

Analysing the Data

At the initial stage of the analysis, the structure of the focus group questionnaire was followed and all audio-visual recordings and transcriptions were viewed and read. This allowed to both get a sense of how easily accessible and grounded their views on good journalism were and to see the points of entry into that discussion. The second phase of analysis was to code all material pertaining to “good journalism” explicitly for further analysis in the NVivo software.

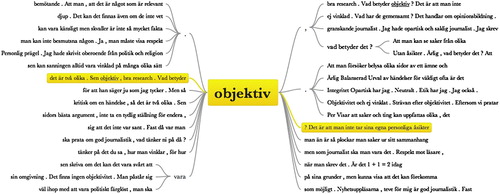

During the analysis, certain topics and/or concepts were deemed more prominent, such as objectivity, truth, contextualisation, proper language, first-hand information and good research, to mention a few. Using the tools Text search and Word trees in NVivo, we checked for prominence and context of the various topics/concepts. The figure below illustrates a search for “objective” (16 hits in the material).

This was a way to learn more about the contexts in which certain important concepts appeared. In the highlighted section in , we can see that one respondent says (following another sentence) “ … and also objective, good research”, upon which the moderator asks “What does objective mean?” This was followed by the reply “That one does not take one's own opinion into account” (approximate translation from Swedish).

FIGURE 1 Illustration of a word tree for the term “objective” (“objektiv” in Swedish). The word tree is a good tool to understand the context in which certain terms/concepts are used

After viewing, listening, and reading through the material several times, it was possible to distinguish aspects of good journalism. The notions that were seen as more prominent were checked with word counts as a way to validate what might be seen as a subjective opinion held by the researcher (i.e. reading through the material gave an “impression”, this impression was then checked and validated in more detail with NVivo). For example, “language”, “using correct/good/understandable language” seemed to be mentioned quite a lot. By using a word count, this “feeling” could then be validated – there were 31 instances of sentiments pertaining to language, such as “The language should be correct/good”, “That the journalist uses good and clear language”. Using these various means of analysis, we found aspects of good journalism that are salient to the respondents.

Findings

Regardless of how the focus groups were composed along the lines of news consumption (high or low) and trust in journalism (high or low), all of them strongly acknowledged the journalistic doxa (similar to the findings of Craft, Vos, and David Wolfgang Citation2016). There were no detectable key differences between the focus groups regarding what constitutes good journalism. They do differ, however, in their assessment of how well journalism is performing; the groups with low trust were more inclined to criticise, occasionally ferociously, journalists and news organisations for failing to meet required standards. Similarly, sometimes what the respondents thought was good journalism was chiselled out through elaborations of the opposite – by defining poor journalism. In addition to the doxa being firmly anchored, all focus groups offered a lot of thoughts and opinions about journalism and they were quick to engage with the issues, suggesting that they are at least somewhat at ease with and can relate to the topic. The reasons why they used and what they were expecting from news in general confirmed the findings from Coleman, Morrison, and Anthony (Citation2012, 39) that news should be “useful, reliable and amusing”. The presentation of the results will begin with the dimensions that are connected to and overlap with the doxa and move on to the dimensions less covered by the literature and professional guidelines.

Objective, Non-partisan and Verified Journalism

The most prominent concept in the discussion about good journalism was objectivity. However, the groups had different focuses when they discussed what objectivity was; some groups were more inclined towards the issue of non-partisanship (sometimes referred to as the problem of partisan journalism/journalists), while others emphasised verification or the factual dimension. However, both these dimensions of objectivity were found in all groups and are also well-grounded in the professional code of ethics and in previous research. When asked “What does objectivity mean?”, respondents said things such as “keeping one's own opinions out of the reporting”, “being able to see things from different perspectives”, “hearing both [all] sides”, that journalists “should not take sides” but treat all parties equal, and that “the content should be sufficiently rich so the listener or reader can make up their own mind, and not have it made up by the journalist” (Group 1). Furthermore, objectivity is referred to as not letting ones political views shine through: “It's when one doesn't bring one's own opinions to the table. That you look at the actual facts, and do not get coloured by personal beliefs” (Group 3). Thus, the principle of objectivity is important but, according to some respondents, hard (or impossible) to adhere to since all reporting is based on various selections, and these selections will be coloured by, for example, the journalist's background and/or beliefs. According to the respondents, being non-partisan is very important for good journalism. This also includes being neutral. The main issues in this regard is that “the journalist should not take sides”, when reporting on conflicts “both sides should be heard”, and the reporting should not be biased. Group 1 discussed neutrality and one respondent stated “I think that when they do interviews in television, different political parties get different kinds of questions. Of course, sometimes different questions are interesting but the treatment can differ”. Another participant chimed in saying “Yes exactly, the treatment can feel very different”. Asked to elaborate the first respondent gave an example “As soon as Sverigedemokraterna [Right wing populists] are interviewed it feels like the journalists are eager to pose questions that put them in a tight spot. The results are often the reverse”. Some respondents povide additional information about bias, such as the use of certain camera angles (perspectives) and the reporters “being more interested in advancing their thesis than seeking the truth” (Group 5). This line of argument is perhaps best summarised by a quote from Group 9: “The most important thing in journalism is to present the best argument from all sides and that the journalists does not take the part of either side”. It is the journalists job to tell all sides of the story and leave it to the public to draw their own conclusions and analysis.

The other point of entry into objectivity was related to verification, facts and truth (truthful, be true, etc.). After analysing the data, a suitable summary of the respondents’ views is that good journalism presents the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. “I want the information to be truthful” and journalists should “write about what has happened and not ‘spice up’ the story” (Group 6). It also seems to be important for the respondents that news focuses on facts and “real events” and that journalism should refrain from reporting stories that could be considered to be pure gossip or related to celebrities. The concept of truth, however, is related to different aspects – on the one hand, the aspect of telling a true story, on the other hand “stick to the truth, even if it's inconvenient”. However, for some respondents, truth, like objectivity, is not a straightforward concept: “It would be presumptuous to say that ‘truth’ is not important, but the truth can be different things to different people” (Group 12). The respondents do separate news from opinion and it is quite clear that they do not expect objectivity in editorials.

In the discussions, facticity was understood in three dimensions: getting the facts right, getting the right facts, and getting the facts first-hand (i.e. first-hand information, preferably based on the journalist not only “being there”, but also being knowledgeable about the local context). “If you’re reporting about a specific place, you should be there. For example, when we had that thing in Husby [a location of unrest, including burning cars] – there were no journalists who went there” (Group 5). According to the respondents, good journalism can then, for example, be that the journalist is “well informed”, “does good research” and presents news “based on facts”, “ … that it is well-grounded, that they check everything so that it's correct before they publish” (Group 5). In relation to getting the facts right (and getting the right facts), the respondents stress the need for proper source criticism with regards to documents as well as human sources; i.e. good journalism checks its sources thoroughly to make sure they can be trusted.

I’ve become more critical to the national newspapers and get mentally exhausted from reading them so I have opted for a local paper. I can't lose this feeling that journalism withholds important information from me. They sift too much information so there is too much missing in their stories, which leads me to distrust them. (Group 11)

Samir Abu Eid, the middle east correspondent in Istanbul from Public Broadcasting Radio, is good. You will always get a good report from him. He is proficient, at the frontline, knows the culture and can communicate with the locals so you will get a lot of interested things from him (Group 3).

Another issue was the position of journalists in news stories at the expense of facts. Several concerns were expressed about the journalists themselves taking too much space in news and, hence, standing in the way of or diverting attention from the non-partisan and factual news that should be the centrepiece. A quote from Group 8 conveys some of these feelings: “I feel there is a competition about who will be seen and heard most and it's not that important what kind of news that they bring to the public, as long as they are at the centre of attention themselves”. Although this issue is stressed in several focus groups, the theme was more prevalent in the focus groups with low trust in news media. This line of argument has a clear resemblance to the “social criteria” of Craft, Vos, and David Wolfgang (Citation2016) who suggest that journalists are viewed as pompous. In relation to journalistic role performance, it can be noted that, first, this is something that members of the public observe and, second, they criticise this because the actors stand in the way of the story (in keeping with the performance metaphor).

Ethical Journalism

Although not the most prominent issue, ethics is also of importance to the respondents. For the respondents, ethics are primarily associated with an ethical code of conduct which those journalists meet in their line of work and not a general ethical code for all aspects of journalistic work. Here, ethics is more understood in the spirit of “minimising harm” as in the SPJ's code of ethics and “respecting personal integrity” in the guidelines offered by the Swedish Union of Journalists. For instance, when discussing “good journalism”, someone would say something along the lines of “good journalism must be ethical”. When asked to elaborate what being ethical entails, the person would then explain how journalists should treat other people they meet in their line of work. How people are treated by journalists was also brought up in other groups, but not necessarily under the label of “ethics”. The people referred to in the discussions were particularly victims of crimes and their relatives, interviewees in general, sources providing sensitive information, but also the general public (by not exposing them to obnoxious stories). Some respondents emphasise the importance of how interview subjects are treated: “You should have respect for the person you interview. You should not be putting words in their mouths. Not draw your own conclusion or behave badly to get a good news story” (Group 6). A similar issue was raised in Group 10: “There are a lot of journalist that writes to take someone down, to put dirt on them. That goes for the media in general”. In another group, the importance “to have a humane way of editing – that you don't edit things out of context” was stressed (Group 4). How victims of a crime are treated are perceived as important:

I think ethics and morals are important. I get so upset when journalists … , take the case of Uddevalla [a murder] with this young people that got shot and they [the journalists] find a friend of the girl and interview them, although she is still in shock – you just don't do that! Don't go after people that are in shock, it is terrible! (Group 7).

Other aspects of ethics are that journalists should await publication until they actually know what has happened (what is true) and not speculate, and that they should refrain from publishing details and images that could be traumatic for victims of, for example, a crime or an accident. The discussion of ethical issues was complicated by the simultaneous need for an audacious journalism.

Audacious Journalism

In both the professional codes of conduct and the scholarly literature (Kovach and Rosenstiel Citation2007; van der Wurff and Schoenbach Citation2014; van der Wurff and Schönbach Citation2014), the investigative and watchdog functions of journalism are deemed to be very important; however, for the respondents in the focus groups, these are not among the top issues that come to mind. Nevertheless, this does not mean that they do not consider these to be important. Moreover, as we interpret the discussions, there are two related but different points of departure into this issue which are structured around trust. The first point of departure echoes previous research and professional codes of conduct because it stresses the watchdog function of journalism or, as one of the participants said, “For me, the purpose of journalism is to be a watchdog of power and question things that are wrong with the society” (Group 10). Detailing a specific journalist on Public Broadcasting Television as a favourite, one respondent argued: “There is this woman, Anna or something, she is middle-aged. She feels … she puts people against the wall, she doesn't cave in. She is fierce, she won't let them go” (Group 2). This line of argument was found in the groups with high trust in journalism. The second point of departure submitted to the idea that journalists should be a watchdog, but also criticised journalism, sometimes fiercely, for fundamentally failing to do so. Instead, they claimed that journalism was laced with political correctness and the influence of the establishment (echoing some of the findings from Coleman, Morrison, and Anthony Citation2012), especially in topics pertaining to immigration. This reasoning was associated with the focus groups with low trust and especially those groups combining low trust with low news consumption. Here, respondents thought that the journalist should be “[…] fearless. By that I don't mean that they shouldn't be concerned about their safety, but rather they need to investigate those in power and those who have influence. They shouldn't be frightened by politicians” (Group 13). According to a respondent in Group 4, journalists have become worse when it comes to really investigating subjects: “The fourth estate,[…]as a journalist one should have the drive to scrutinise, dig up and present things and conditions in the society, but I believe they have become worse at doing that”. In Group 3 the respondents shared concerns about journalists not being independent from particular political coalitions, one respondent offering his thoughts:

Well, I think that the journalists want to control … they think that people are uncritical and accepts everything, but I think that people have started to learn that there is a lot coming out from The Greens and The Left and that they try to control us in that direction, but I’m not buying into that! Also, I don't experience any critique towards politicians but rather that the journalists are running errands for politician instead of scrutinizing them politically.

Another respondent added: “Except in some cases when they decide it is a scandal. It is either or. Either they do not give a damn about what politicians say or do, then the day after they say, well, let's chase this person some”. The first respondent replying: “Well, that depends on what politician it is. If it is one on the right he might be in more trouble compared to a green or leftist”.

Being audacious also means to have the strength to be inconvenient; e.g. “Journalists should go against the grain. To have the courage to shine the light on inconvenient and non-politically correct truths. To be able to have a debate about immigration politics without being labelled a racist, to shine light on what is problematic with immigration” (Group 12). This inconvenience includes the journalists’ own profession: “journalists are very keen on scrutinizing politicians, but they are not at all interested in scrutinizing each other, and that is bad” (Group 3).

Is Transparent Journalism Good Journalism?

Transparency has been promoted by both academics and professional associations (SPJ have recently added transparency to their code of ethics; see Craft, Vos, and David Wolfgang Citation2016 for further discussion) as a new normative standard and as a measure to improve journalistic credibility and win back lost news consumers. Thus, it was important to understand to what extent the respondents associated various forms of transparency with good journalism. Interestingly enough, transparency related facets were mentioned quite rarely and, when they were, they were not the focus of attention for very long. However, there were a few occasions when features tangential to transparency came up. A couple of times, attention was directed towards the issue that journalists should be open about their personal opinions; e.g. “It is okay if they have their opinion, but then it should be stated” (Group 3). There were also a few mentions in passing about publishing faulty information and correcting this afterwards: “If they dare to correct themselves it feels honest and straightforward, but sometimes there should be no subterfuge” (Group 9). Other than on those few occasions, transparency was not mentioned or discussed by the focus groups in relation to what they perceived to be good journalism (transparency was introduced explicitly by the researchers at a later stage of the discussions, reported elsewhere – Karlsson and Clerwall Citation2018). The lack of attention to transparency is interesting, since this indicates that a more transparent journalism will most likely not have any immediate large impact on how the public views journalism.

Journalism That Use Proper Language Is Well-designed and Pleasant-to-consume

A second strong theme that arose in the focus groups – in addition to objectivity as discussed in relation to non-partiality and verification – is what can be referred to as criteria that evaluate the linguistic and aesthetic qualities of journalism. These are both associated with the mode of delivery rather than the specific journalistic content. The theme was a somewhat surprising finding, as previous research does not probe this dimension and it is not an explicit part of the professional associations’ codes of ethics. Actually, as Barnhurst and Nerone convincingly argue (Citation2001; see also Carlson Citation2017), the role that form has in journalism is important, but rather underestimated in journalism studies. In that context, it is remarkable that all of the focus groups stressed the huge importance of non-content dimensions and especially the issue of language in one way or another. Using proper, correct and interesting (in the sense that it should encourage further reading) language is of great importance for good journalism: “There is an impoverishment of the language that is horrible. I have a hard time with that. For example, the subtitling on television news, they are misspelled in every news broadcast. One wonders what kind of people that writes them” (Group 11). A few participants announced that they would stop reading altogether if they came across a spelling error as this respondent “I think my preferred paper is good except when they misspell because then I stop reading the article immediately [Laugher from the rest of the group]. Yes, sometimes I don't get to read a lot of the paper” (Group 3). Expanding on the issue of under what circumstances a proper language is important in journalism one respondent said “In all serious journalism. For a news story to be taken serious it must be apparent that the journalist has read through the text at least once before he/she clicks to publish it” (Group 4). The issue of language can be further divided. One already mentioned aspect is the use of proper language – i.e. correct spelling, proper Swedish and complete sentences – and it seems very important to the respondents that journalists be able to handle this. This applies both to written journalism as well as to television news where the news anchor is supposed to talk calmly, clearly and pronounce words correctly. Another aspect has to do with target group adaption; i.e. that the journalist should know to whom they are speaking: “I think it's really important to adapt it [the language] to the readers. If it is a school paper, the language can't be too advanced, but if it's DN [Dagens Nyheter, a Swedish broadsheet paper], it can be adapted for that” (Group 6). In Group 5 the respondents noticed that the morning broadcast of the local news was moved to a larger city and felt that this put a dent in the trustworthiness because “They are just sitting there, reading from a paper without any local connection. They can't pronounce the place names correctly. It becomes less true … but no. I think it is sad. That blocks me from hearing the rest of the broadcast”. Yet a third aspect has to do with storytelling, in the sense that the news should be presented in a way that encourages the audience to start reading news and then make it interesting enough for the audience to keep on reading by using humour and other techniques to increase audience interest and curiosity. “It has to be compelling or I won't read” (Group 7).

While language is clearly more important in discussions of form, there are also a few focus groups that discussed aesthetic dimensions of news: “The design of the homepage will determine whether I will even look at it or not. If it looks proper I will look at it. It's all about the packaging; to me it matters a lot” (Group 5). Discussing his favourite news outlet, a respondent motivated his preferred option, Public Service Television, because “They have a very nice website, I think, that also work great on the cell phone. There are no commercials and, therefore, the site load very fast” (Group 1). In another group (Group 7), the font, typesetting and the overall composition and structure of the news – individual items as well as whole outlets – are discussed as important for increasing readability and avoiding confusion.

To conclude, if the findings were translated into a tentative definition of good journalism, it would read something like: Good journalism is objective, unbiased, and based on verified facts from many different and reliable sources. It is a watchdog of power and presents citizens with relevant information about the societies they live in. It is carried out by professionals who do not have a personal stake or an agenda of their own in the subjects they cover, but who have great, preferably first-hand, contemporary and historical knowledge of the subject matter. They have empathy towards those they meet in their line of work, yet they do not shy away from asking uncomfortable questions, nor do they stop asking them, despite evasive manoeuvres. Good journalism takes great measures to tell news stories in an interesting, well-designed, correct, and easy-to-read manner adapted to its audiences.

Embracing the Doxa and Evaluating Journalists Accordingly

Reading the results from this study is, with one notable exception, like reading a professional code of conduct. The public is, as Craft, Vos, and David Wolfgang (Citation2016, see also the results from various countries in the theory section) suggest, more than anything else an ally to journalists and largely embraces the journalistic doxa, although the same words (e.g. objectivity) may not carry identical meanings for the public. All respondents agree that journalists should be objective, but they may not agree upon what objectivity is.

Viewed from a Bourdieuan outlook, the perceived heterodoxic journalistic performance raises questions about the autonomy of the journalistic field and how much journalists and citizens have to say about it, despite the large doxic overlap between them. While it is beyond what can be concluded from this study, it stresses the need to probe actors and forces outside the journalistic field in determining what or who that have the greatest influence over what journalism is.

Anyhow, the journalistic field has been rather successful in exporting their doxa to other fields of society; in this case, the social field in which the public resides. The reason for this is impossible to trace, but a possible explanation might be that the education system in Sweden includes media literacy (in a broad sense) in the curriculum, and Swedish students read about the role of the media in society and about rules and regulation for the press, television and radio (Skolverket/Swedish National Agency for Education 2015). Furthermore, knowledge about the “system” can also be connected to the fact that, for example, critiques from the “Review board for radio and television” is, by regulation, presented to the public on air. That is, as a news consumer you are on occasion exposed to information about news not adhering to, for example, the rules of objectivity and non-partisanship. Thus, school teaches students about, for example, journalism ethics, and these values are internalised. Using Bourdieuan terminology, the journalistic field has been successful at exporting the doxa to the field of education. In this regard, it might be expected then, when prompted, that citizens bring notions such as objectivity, being neutral, hearing both sides, etc., to the fore.

The general impression is that the public share journalists’ views about what constitutes “good journalism”. From an SCT perspective, then, the social contract of what norms should guide journalism and what performance journalists ought to execute seems constant between the relevant parties – a pillar of SCT theory (Wilkins Citation1990; Ward Citation2005; Sjøvaag Citation2010; Merrill Citation2011). Following this, it would be difficult to argue that the decline of journalism has to do with the norms as such, as they are shared with the public to a large extent. Rather, it could be related to the perceived upholding of these norms (as indicated by results from Coleman, Morrison, and Anthony Citation2012) or, feasibly, factors other than journalistic performance per se that are the causes of the decline. This also points towards a limited effect of an alleged increase, or halted decline, in credibility by shifting journalistic ideals to a more transparent way of doing journalism, as some research suggests (BLINDED; Plaisance Citation2007; Chadha and Koliska Citation2015; Vos and Craft Citation2017). In short, if traditional journalistic norms (or doxa) are not the problem, then changing them doesn't seem like an adequate, or full, solution. Maybe a part of the answer instead lies in something as unpretentious as hiring more proofreaders.

While there is much agreement between the journalistic doxa and what the respondents think constitutes good journalism, there is also one critical difference. Only second to objectivity, the linguistic and aesthetic qualities of journalism are critical to the respondents, but not acknowledged in previous research or codes of conduct. Still, linguistic and aesthetic qualities are not strange creatures to journalism; rather, the contrary is true. However, these are based on a more technically oriented journalistic skillset (e.g. Carlson Citation2017) but not an explicit (e.g. codified in professional guidelines) part of the doxa. If we accept that journalism has no true essence (Hanitzsch and Vos Citation2017) and is shaped in discourse with different actors, including citizens, then, by extension, a journalism adhering to high linguistic and aesthetic standards will most likely strengthen ties with citizens and lead to greater legitimacy. It can even be argued that the linguistic and aesthetic dimensions are more important than other dimensions because the citizens can see and understand them. Put bluntly, it is possibly easier for a layman to evaluate journalistic performance on the basis of spelling than by identifying the most relevant parties or the most important sources in a current issue. It will be much more difficult, perhaps impossible, for citizens to evaluate if journalists are loyal or adversarial and to whom, or how the gathering and processing of the material was conducted. Indeed, what is available for citizens to base their evaluations on, is what they can see or otherwise derive from content or the interface. While spelling and layout is rather technical in nature, the respondents let this inform their overall assessment of journalism.

The results also raise an ontological issue. Typically, what journalism really is is often answered in terms of its ambitions (serving the public) or its defining treatment of information (e.g. verification and the use of multiple and independent sources). However, the results indicate, in line with what Barnhurst and Nerone (Citation2001) suggest, that form is also a dimension of what journalism really is. Thus, following Carlson’s (Citation2017, 53) definition of journalistic form as “the persisting visible and narrative structure of news”, it is of great significance that journalism studies should take larger notice of, and identify journalism's unique linguistic and aesthetic dimensions. Form should be given greater consideration in a range of issues, from discussions concerning what the journalistic doxa is, to inclusion in studies on news consumption and trust in news media, to how journalistic role performance is conceptualised, and to issues as mundane as what questions researchers ask in surveys. For journalism practice, upholding linguistic and aesthetic standards and advocating them is a good opportunity to build legitimacy, and, at the same time, promote unique journalistic skills. Moreover, form as the “persisting visible and narrative structure of news”, in turn, raises questions in relation to the practice of hybrid forms of journalism and PR (such as native advertising) that mimic the form but not other parts of journalism. If form is so crucial for how and what citizens perceive to be journalism, then the transfer of journalistic form to other information genres cannot be casually accepted. Contrarily, since the results suggests this is already a tacit part of the doxa, journalistic forms could be explicitly included in, and protected by, codes of conduct.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Barnhurst, Kevin G., and John C. Nerone. 2001. The Form of News. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Bennett, Lance, Lynne Gresset, and William Haltom. 1985. “Repairing the News: A Case Study of the News Paradigm.” Journal of Communication 35 (2): 50–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1985.tb02233.x

- Benson, Rodney, and Erik Neveu. 2005. “Introduction: Field Theory as a Work in Progress.” In Bourdieu and the Journalistic Field, edited by Rodney Benson and Erik Neveu, 1–25. Cambridge: Polity.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 2005. “The Political Field, the Social Science Filed, and the Journalistic Field.” In Bourdieu and the Journalistic Field, edited by Rodney Benson and Erik Neveu, 29–47. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Carlson, Matt. 2017. Journalistic Authority Legitimizing News in the Digital era. New York: Columbia university press.

- Chadha, Kalyani, and Michael Koliska. 2015. “Newsrooms and Transparency in the Digital age.” Journalism Practice 9 (2): 215–229. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2014.924737

- Coleman, Stephen, David E. Morrison, and Scott Anthony. 2012. “A Constructivist Study of Trust in the News.” Journalism Studies 13 (1): 37–53. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2011.592353

- Costera Meijer, Irene. 2003. “What Is Quality Television News? A Plea for Extending the Professional Repertoire of Newsmakers.” Journalism Studies 4 (1): 15–29. doi: 10.1080/14616700306496

- Costera Meijer, Irene. 2012. “Valuable Journalism: The Search for Quality From the Vantage Point of the User.” Journalism 14 (6): 754–770. doi: 10.1177/1464884912455899

- Craft, Stephanie, Tim P. Vos, and J. David Wolfgang. 2016. “Reader Comments as Press Criticism: Implications for the Journalistic Field.” Journalism 17 (6): 677–693. doi: 10.1177/1464884915579332

- Flanagin, Andrew, and Miriam Metzger. 2007. “The Role of Site Features, User Attributes, and Information Verification Behaviors on the Perceived Credibility of Web-Based Information.” New Media & Society 9 (2): 319–342. doi: 10.1177/1461444807075015

- Gil de Zúñiga, Homero, and Amber Hinsley. 2013. “. “The Press Versus the Public: What Is ‘Good Journalism?’”.” Journalism Studies 14 (6): 926–942. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2012.744551

- Hanitzsch, Thomas, Folker Hanusch, Claudia Mellado, Maria Anikina, Rosa Berganza, Incilay Cangoz, Mihai Coman, et al. 2011. “Mapping Journalism Cultures Across Nations.” Journalism Studies 12 (3): 273–293. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2010.512502

- Hanitzsch, Thomas, and Tim P. Vos. 2017. “Journalistic Roles and the Struggle Over Institutional Identity: The Discursive Constitution of Journalism.” Communication Theory 27 (2): 115–135. doi: 10.1111/comt.12112

- Karlsson, Michael. 2010. “Rituals of Transparency: Evaluating Online News Outlets' Uses of Transparency Rituals in the United States, United Kingdom and Sweden.” Journalism Studies 11 (4): 535–545. doi: 10.1080/14616701003638400

- Karlsson, Michael, and Christer Clerwall. 2018. “Transparency to the Rescue?” Journalism Studies, doi:10.1080/1461670X.2018.1492882.

- Kohring, Matthias, and Jörg Matthes. 2007. “Trust in News Media: Development and Validation of a Multidimensional Scale.” Communication Research 34 (2): 231–252. doi: 10.1177/0093650206298071

- Kovach, Bill, and Tom Rosenstiel. 2007. The Elements of Journalism: What Newspeople Should Know and the Public Should Expect. New York: Three Rivers Press.

- Krueger, Richard, and Mary Ann Casey. 2009. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide to Applied Science. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Mellado, Claudia. 2015. “Professional Roles in News Content: Six Dimensions of Journalistic Role Performance.” Journalism Studies 16 (4): Taylor & Francis: 596–614. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2014.922276

- Merrill, John C. 2011. “Overview. Theoretical Foundations for Media Ethics.” In Controversies in Media Ethics, edited by David Gordon, John Michael Kittross, John C Merrill, William Babcock, and Michael Dorsher, 3–32. New York: Routledge.

- Nielsen, Rasmus Kleis. 2016. “Folk Theories of Journalism.” Journalism Studies 9699 (May): 1–9.

- Plaisance, Patrick Lee. 2007. “Transparency: An Assessment of the Kantian Roots of a Key Element in Media Ethics Practice.” Journal of Mass Media Ethics 22 (2–3): Routledge: 187–207. doi: 10.1080/08900520701315855

- Schudson, M. 2001. “The Objectivity Norm in American Journalism.” Journalism 2 (2): 149–170. doi: 10.1177/146488490100200201

- Schultz, Ida. 2007. “The Journalistic Gut Feeling.” Journalism Practice 1 (2): 190–207. doi: 10.1080/17512780701275507

- Sjøvaag, Helle. 2010. “The Reciprocity of Journalism’s Social Contract.” Journalism Studies 11 (6): 874–888. doi: 10.1080/14616701003644044

- Tsfati, Yariv, Oren Meyers, and Yoram Peri. 2006. “What Is Good Journalism? Comparin Israeli Public and Journalists’ Perspectives.” Journalism 7 (2): 152–173. doi: 10.1177/1464884906062603

- Tuchman, Gaye. 1972. “Tuchman 1972 Objecitivity as a Strategic Ritual.” The American Journal of Sociology 77 (4): 660–679. doi: 10.1086/225193

- van der Wurff, Richard, and Klaus Schoenbach. 2014. “Civic and Citizen Demands of News Media and Journalists: What Does the Audience Expect From Good Journalism?” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 91 (3): 433–451. doi: 10.1177/1077699014538974

- van der Wurff, Richard, and Klaus Schönbach. 2014. “Audience Expectations of Media Accountability in the Netherlands.” Journalism Studies 15 (2): 121–137. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2013.801679

- Vos, Tim P., and Stephanie Craft. 2017. “The Discursive Construction of Journalistic Transparency.” Journalism Studies 18 (12): 1505–1522. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2015.1135754

- Ward, Stephen J A. 2005. “Philosophical Foundations for Global Journalism Ethics.” Journal of Mass Media Ethics : Exploring Questions of Media Morality 20 (1): 3–21. doi: 10.1207/s15327728jmme2001_2

- Wilkins, Lee. 1990. “Taking the Future Seriously.” Journal of Mass Media Ethics 5 (2): 88–101. doi: 10.1207/s15327728jmme0502_2