Abstract

This article analyses the discursive representations of trans people in 15,901 mainstream Swedish newspaper articles between 2000 and 2017 using topic modelling and critical discourse analysis. Drawing from critical perspectives on gender it was found that the articles to various degree assisted in maintaining heteronormativity. The discursive strategies employed by the journalists included trivialisation of trans expressions as dress-up and incorporation of them within binary stereotypes. Trans people were also excluded and deemed as deviant in some articles through insensitive gender descriptions and descriptions. Through the voices of experts, trans people were silenced and pathologized and while some representations of trans people were meant to empower, and offered a slightly less rigid view on gender, these articles too reinforced heteronormativity through continuous referral to binary gender.

Introduction

Sweden is considered one of the most progressive countries in the world when it comes to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) rights (ILGA-Europe Citation2015; McCarthy Citation2015). In the 1990s through the 2000s several laws were passed expanding LGBTQ rights with respect to anti-discrimination, same-sex adoption, artificial insemination and equal marriage practices. During this period trans people gained recognition in Sweden after being included into the agenda of The Swedish Federation for LGBTQ Rights (RFSL) in 2001. In 2009 transvestitism was no longer considered a mental illness (Ernhagen Citation2008) and in 2013 the legal requirement of sterilisation when undergoing transition was removed (SFS Citation2013, 405).

While Sweden has come further towards equal rights than others, it is in no regards equal for all. Although transvestitism is no longer considered a mental illness, transsexualism is, resulting in long and demanding medical evaluation processes. According to the Public Health Agency of Sweden (Citation2015) discrimination, violence and low trust in societal institutions affect trans people’s health, where one in three trans people have considered suicide. For trans people much of these issues stem from heteronormativity, defined by Ambjörnsson (Citation2016, 47) as “the institutions, laws, structures, relations and actions that uphold heterosexuality as something uniform, natural and universal”, marking non-conformers as deviant (Rosenberg Citation2011; Ryan Citation2009).

News media play an important role in creating these possibilities and limitations of transgender people’s rights and identities. Mainstream media outlets reach many and have the power not only to decide what becomes news but also how that news is framed (McQuail Citation1994). It is therefore imperative to study news media representations of trans people in a country like Sweden, where there is a perception of progressiveness, yet, where representations of trans people in the media are still largely unexplored.

For a broad scope that encompasses a period of major change in transgender people’s rights, articles published between 2000 and 2017 are studied with the aim of analysing discursive representations of trans people in mainstream Swedish newspapers. The article focuses on how trans people have been reported on in the Swedish printed press over time and in relation to the reporting on LGBTQ in general, how reporting on trans issues have been constructed as a means of both maintaining and challenging heteronormativity and on how featured voices have contributed to the representation of trans people in the articles.

Representations of Trans People in the Media

Mainstream news media have a history of marginalising, stereotyping and pathologizing representations of trans people (Barker-Plummer Citation2013). Ever since the public “transformation” of American trans woman Christine Jorgensen in the 1950s was among the first to cause headlines, trans people have often been covered in a sensationalistic way by news media (Arune Citation2006; Cloud Citation2014; Hackl, Becker, and Todd Citation2016; Meyerowitz Citation1998). Often figuring in soft news stories (Capuzza Citation2014, Citation2016), research has found tabloids to cover trans issues in a particularly delegitimising manner (Billard Citation2016).

This paper explores the ways in which reporting on trans people work as a means to maintain or challenge heteronormativity. The way in which pronouns are used is one way of communicating gendered identity values (Parks Pieper Citation2015), and contributes to how trans people are perceived by news consumers. A large body of research has documented media’s insensitivity towards different definitions of trans, and misuse of pronouns and names (Barker-Plummer Citation2013; Capuzza Citation2015, Citation2016; Gupta Citation2018; Hackl, Becker, and Todd Citation2016), therein undermining the expressed identity as an alias or an act, rather than a legitimate gender identity (Willox Citation2003). Often, research has found that news media focus on sexual organs, as well as binary expressions of masculinity and femininity in terms of defining trans people (Baptista and Himmel Citation2016; MacKenzie and Marcel Citation2009; Sloop Citation2000; Squires and Brouwer Citation2002).

Trans people are sometimes framed as deceptive through use of offensive language (Capuzza Citation2016; MacKenzie and Marcel Citation2009) but also media coverage set out to be inclusive can marginalise and suppress trans people (Riggs Citation2014). However, trans expressions in the media face varying degrees of marginalisation and discrimination. Where trans expressions are a means of necessity, without outspoken link to personal identity, Ryan (Citation2009) argues that the person becomes less exposed to stigmatisation. Also, trans people who appear to be embracing the binary gender norms, adhering to the “good transsexual” narrative are represented more favourably (Skidmore Citation2011, 205; see also Espineira Citation2016; Glover Citation2016; Mackie Citation2008).

In terms of who is voiced in articles regarding trans issues, often, the subject is commented on by experts – people in legal, political, scientific and medical positions of power (Graber Citation2017). Stories in which trans people are considered experts themselves often regard personal issues such as self-perception. When it comes to voicing trans issues, research has found transwomenFootnote1 more likely to represent trans people in articles than other trans identities (Capuzza Citation2014; Li Citation2018). Especially absent, are generally representations of non-conforming trans identities (Billard Citation2016).

While trans people are gaining an increasingly large presence in the news (Capuzza Citation2016) and although, as illustrated, there is a relatively large body of research concerning trans people in these settings, there is an evident lack of studies in a Swedish context.

Hetero- and Cisnormative Discourse

Butler (Citation1990) argues that the gendered body is performative. That it is only real because of the acts that maintain it. As sexuality is thereby located within the body, the political regulations that control it are kept from view.

Men and women are expected to feel desire only for each other, which in turn maintains views of men and women as complementary opposites with different social roles (Ambjörnsson Citation2016; Schilt and Westbrook Citation2009). This is often determined through biology (Westbrook and Schilt Citation2014). Trans bodies are in this manner experienced as deceitful, threatening binary gender norms and risking social sanctions as they signal one gender despite being “the other” (Ryan Citation2009; Schippers Citation2007). Those who “pass” as cisgenderFootnote2 are simultaneously more legitimate and more deceitful (Billard, forthcoming). This is closely linked to the notion of cisnormativity, which is the belief that all people are cissexual (Bauer et al. Citation2009) and content with the sex they were born into (Serano Citation2007). Much like heteronormativity, which concerns “the institutions, laws, structures, relations and actions that uphold heterosexuality as something uniform, natural and universal” (Ambjörnsson Citation2016, 47), assumption of cissexuality shape societal institutions, rendering trans people invisible. Expectations of conformity are at the core of transgender oppression, making analyses of normalisation practices important (Ambjörnsson Citation2016; Rosenberg Citation2011).

Media contributes to reproducing unequal power relations through seemingly natural ways of positioning people in their reporting (Fairclough Citation1995). Language plays a crucial role in these manifestations of hegemonic power as it is concerned with maintaining certain ways of defining meaning. Ideology is assumed and appears natural and inherent, based on beliefs grounded in conventions that constitute and authorize hegemonic power relations (Fairclough Citation2001). A critical perspective on normative gender performance is therefore applied in this paper, as well as a critical approach to journalistsFootnote3 use of discursive strategiesFootnote4 in their representations of trans people, as a means of contributing to, maintaining, or challenging discourses.

Research Design

In this study, I combine quantitative topic modelling and discourse analysis. Topic modelling handles the common problem where the few texts chosen for discourse analysis are exceptions, selected not for being typical but instead for standing out. The methods complement each other as topic modelling focuses on larger patterns in the dataset, whereas critical discourse analysis (CDA) allows for in depth analysis of the meaning of these patterns, thereby strengthening the discourse analysis and limiting bias.

The tool used for topic modelling in this paper is the Machine Learning for Language Toolkit or MALLET, a java-based, open sourced software (McCallum Citation2002). It is based on Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA), a probabilistic statistical model that inductively clusters words together, creating topics based on their probable distribution over the corpus (Blei, Ng, and Jordan Citation2003). LDA assumes that a text consists of a determined number of topics and that each of the texts in the dataset to various degrees are made up of these topics (Blei Citation2012).

The number of appropriate topics vary between datasets, there are no standard number of topics. Research has found that traditional metrics for measuring topic coherency are out-performed by human judgement (Chang et al. Citation2009). Therefore, the number of topics must be based upon how coherent the topics turn out. Through the typical trial-and-error approach, where a number of constellations where tried, it was found that a suitable number of topics for this dataset was 50, as few topics then became overly generic, while still nuanced.

This paper has studied articles from large mainstream, Swedish newspapers. Including three metropolitan morning papers and two tabloids, often used in news media studies due to their larger readerships (see Heber Citation2011; Scott and Enander Citation2017). Having print readerships of between 322,000 and 652,000 and national coverage, these five are important in shaping Swedish public discourse. Recognising the importance of regional papers, two local papers - one from southern Sweden with 189,000 readers and one from northern Sweden with 73,000 readers were also analysed. Six of these newspapers are published every day and one publishes six days a week.

In total 15,901 articles were collected using the media archive Retriever. The articles were published between 2000 and March 2017, a time frame which encompasses a period with several reasons for increased media interest regarding LGBTQ issues, as mentioned in the introduction. The search words were based on the glossary of RFSL (Citation2015), where terms representing sexual identities and preferences in relation to LGBTQ were chosen with asterisks (*) to include all suffixed versions of the words. This of course limited which transgender identities could be represented in the article selection, but it could also be assumed gender identities not listed in RFSL’s glossary, are unlikely to be represented in mainstream news media to any larger extent, demonstrating news media’s authority to set the public agenda. These search words include not only trans related words, but also gay, bisexual and lesbian related terms in order to situate representations of trans people within a larger context of LGBTQ and thus provide an initial understanding of how trans people have been reported on in the press compared to reporting on other LGBTQ issues. Translated versions of the terms are seen below:

bigender/bigender* OR bi sex/bisex* OR gay* OR cis OR drag king* OR drag queen* OR dyke* OR ftm OR gay* OR gender queer*/genderqueer OR lgbt* OR homo* OR non-binar* OR non binar*/nonbinar* OR inter gender*/intergender* OR inter sex*/intersex OR lesbi* OR mtf OR non-gender* OR non gender*/nongender OR pan sex*/pansex OR queer* OR trann* OR transgender* OR trans person* OR transvestit*

Appendix A provides a table of all topics’ manually given names, their weight over the dataset, the first appearance of “trans*” among the most important words, and to give an indication of the theme of the topic - it's first, and most related five words. Generally, the “trans*” stem was far down in the list of relevant words. Only in a handful of topics did “trans*” appear among the top words. Of these few topics, one mainly concerned the Pride Festival and one The Swedish Federation for LGBTQ Rights (RFSL). This left two topics, which did not just contain “trans*” among their most important words, other terms also indicated that trans issues were the foci for the topic. “Trans people A” with the top ten words: woman, transvestite, Sara, men, transvestites, Claes, clothes, women’s clothes, women and dress, and “Trans people B”, with the top ten words: sex/gender, trans people, transsexual (plural), woman, transsexual (singular), sex change, people, changing, transgender person and body indicate two contrasting perspectives on trans issues. Through the MALLET output, the ten strongest correlating articles to each of these two trans related topics, with more than seventy-five words, were chosen for qualitative analysis if trans people was the main subject. The articles chosen for discourse analysis were distributed over all news sources.

Critical Discourse Analysis

Critical Discourse Analysis focuses on both micro and macro structures, and the relationship between these (Fairclough Citation2010). It can be used to make systematic connections between news media texts and society, with the goal to expose inequality through language use, as a step towards social change (Fairclough Citation1992). The use of Fairclough’s method of critical discourse analysis has meant studying the articles from the tree dimensions of text, discursive practice and social practice. The articles were read extensively and in practical terms, a number of questions were asked to the texts in accordance with these three dimensions.

In the textual part of CDA, focus is with the textual elements themselves (Fairclough Citation1992). For this paper that meant analysing the mood, transitivity, exchanges, speech functions and modality of the articles to get a sense of how the journalists committed to the texts, what type of information was being mediated and in what way. Moving further from the texts themselves, the focus of the analysis shifted to studying how intertextuality, news source and placement in the papers could have influenced the text. Intertextuality concerns the incorporation of other texts (Fairclough Citation2003). For this study it was defined as concrete reference to other texts by the journalists in the articles. Further, assumptions made by the journalist based on what was not written in the articles were considered. This is connected closely to ideological relations and structures, as well as to implicit and explicit evaluations of what could be considered desirable and undesirable, and in extension, hence also to hegemonic power and heteronormativity.

When studying the sociocultural dimension of a text, social structures, and ideological and political aspects of discourse are analysed (Fairclough Citation1992). The analysis, while taking all three dimensions into consideration, focuses mainly on the discursive and social practices.

Analysis

The following section first presents the quantitative results, thereafter follows a discussion of the use of three primary discursive strategies in the reporting. Following that is an analysis of the way voices are incorporated in the articles to silence or empower trans people.

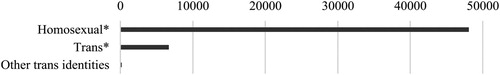

Out of the 15,901 articles studied, articles containing the search terms made up simply 8.5 percent of all articles in the dataset. Articles with the specific word “trans*” and words representing other trans identitiesFootnote5 were, in comparison to “homosexual*”, largely marginalised, as seen in .

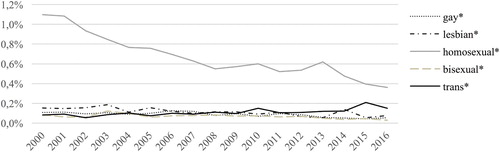

Representation of LGBTQ people in Swedish press, was especially earlier on, largely left to that of homosexuality as a term as seen in . Other terms included in the LGBTQ acronym gain equally little attention as trans issues, and in the later part of the period, even less. And while that difference in reporting is less obvious later in the studied period, this seems to be more closely related to less reporting on homosexuality rather than an increased attention to other terms in the acronym. This is also evident in the table provided in Appendix A, where there are several highly weighted topics concerning homosexuality.

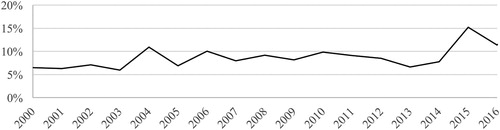

Still, unlike Capuzza (Citation2016) who did not find an increase in articles in three large, mainstream, American newspapers between 2009 and 2013, reporting on trans people did increase in Sweden, not only during this period but also in general, as seen in , from 6 percent in 2000, to 11 percent of the articles in the dataset in 2016. Based on Retriever data, there was no increase in the number of published articles over the studied period, therefore this does not seem to indicate a proportional decrease.

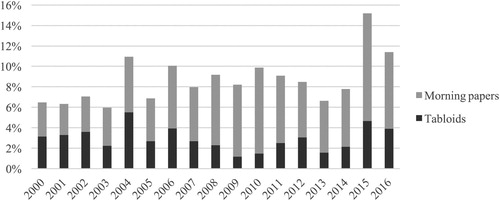

This increase in reporting comes mainly from the morning papers. As seen in , the tabloids contribute with half of the related articles until 2005, but less than 39 percent between 2012 and 2016.

Of the 50 topics making up the dataset, only two indicated a centrality around the subject of trans people, and neither of these where of great importance to the dataset, further indicating the marginalisation of trans issues. “Trans people A” is focused on the shallower perspective of the “appearance” of gender, with words like hair, women’s clothes and make-up among the topic’s most important, possibly indicating it containing softer news. “Trans people B” is centred around legal and medical aspects of transgender issues. Central words such as body, sterilisation and sex/gender indicating it possibly containing harder news articles. Some aspects differed between the articles of the two topics in terms of the manner of representing transgender people. Five of the ten articles in “Trans people A”, the seemingly shallower topic, came from tabloids, possibly indicating news of a softer character. The relevance of the articles to the topic ranged from around 44 to 54 percent and they had an average length of 596 wordsFootnote6. The articles from “Trans people B” tended to be shorter, at an average of 352 words. Six of them were smaller news items, four of those originated from the news bureau TT. Here, the relevance of the articles ranged between 53 and 70 percent and were thus more strongly connected to the topic than articles related to “Trans people A”. This could mean that the way in which trans issues are discussed in the articles of “Trans people A” is less evidently related to trans issues, while the articles in “Trans people B” generally focus more of their textual content to trans issues.

Despite indications towards the topics separate focuses, they overlap. Body, looks, transsexual, transvestite, doctor and gender are among the words they have in common which indicates elements of both a more superficial nature as well as words typically related to the medical aspects of transgender issues. Articles are therefore not analysed separately based on topic relations, as that would constrict the findings of the analysis.

Discursive Representations of Trans People

This following section demonstrates three discursive strategies by which the media positioned trans people. First, a strategy of trivialising trans expressions as entertainment, second, of incorporating trans expressions into binary gender norms and third, a strategy of exclusion, deeming trans people as deviant. In reality, these strategies overlap but for the purposes of detailing them, they are analysed separately.

Trivialising trans expressions

Present in several of the articles is a desire by the journalists to represent trans expressions as just for fun done by cisgender, white men. These soft news articles are connected to “Trans people A” and they are all published in the tabloids, echoing previous research where tabloids delegitimise trans expressions (Billard Citation2016). While cisgender expressions of trans people do not fit under the trans umbrella, it must be remembered that the representations of trans people by news media is in focus here and if these are in part carried out by people who do not identify with trans identity as a legitimate gender expression, then that indicates a lack of fair opportunity for transgender people to be heard. Resulting in that cisgender, white men come to represent not only transwomen but also the trans community in general, in mainstream, printed media.

The journalists of these articles keep the men’s trans expressions at a distance from their “real” identities. In a tabloid article, for instance, a Norwegian prince in drag is according to the journalist “play[ing] transvestite” (Lindwall Citation2010). In another article headlined “I wanted to sing in female clothing”, a cisgender, male band is described by the journalist as planning a “transvestite coup” in an upcoming music competition and the singer is quoted as having the “silly idea” that they would “dress in women’s clothes” (Lindstedt Citation2002). Thus, equating transvestite here to wearing female clothing for laughs. In another article headlined “Robbie’s new look”, it is suggested that:

Pop artist Robbie Williams has a whole new style – as transvestite. In the video of the song ‘She’s Madonna’ he performs as a drag show artist (Joo Citation2007).

There are other examples where trans is trivialised. An article where a male journalist tries drag on Pride, includes numerous examples where trans identity is reduced to dress-up:

[I] approach the trannies Melitta and Tiffany and introduce myself as Laura. They are both close to 1,90 [meters] tall. Drag queens are often very tall guys (Kriisa Citation2000).

Playing with transgender expressions can be a way to exposing gender as simply a construct that can be imitated but here it contributes to reinforcing stereotypes and heterosexual hegemony. The misuse of definitions and pronouns, enhanced by such claims as the “homo world is a jungle of terms” (Kriisa Citation2000) equates trans people’s identities to homosexual expression, discrediting all definitions of “trans” as too complicated to learn or engage in and contributing to transgender issues not being taken seriously.

Incorporating trans expressions

The articles contain examples of when the journalists compare cisgender, white men’s representations of trans people to stereotypical male and female. One article included, transphobically headlined “MALE FASHION ‘You are wrongly classed as transvestite’” (Eriksson Citation2011), is about a cisgender man wearing stockings. However, it seemingly centres around trans issues, as the article focuses largely on proving the person to be a cisgender man. In comparison to the previously mentioned cisgender men “doing trans as dress-up”, this man wears stockings as a personal preference and thereby risks stigmatisation to a much larger extent. Possibly fearing his deviation from the male dress code would threaten his manhood, and in extension disturb the heteronormative order (see Schippers Citation2007), the interviewee wants to remain anonymous to not be labelled a “pansy” (Eriksson Citation2011).

Other articles contrasted transgender expressions to heteronormative values. By affirming that the previously mentioned prince of Norway is “a husband and father of three” (Lindwall Citation2010), facts unrelated to the article itself, the journalist contrasts the trans expression with the “real” man. He, who has asserted his manliness in the most heteronormative manner by having children (with a spouse of the “opposite” sex).

Underlying ideological and hegemonic assumptions of heteronormativity are visible also through a misogynistic, sexualising of the femininely coded trans body. Legs are acknowledged as “good looking” (Lindwall Citation2010) and putting on bra and stockings is “kinky” (Lindstedt Citation2002). The journalist trying drag at Stockholm Pride acknowledges his transformation from man to woman in a Pride make-up tent as successful through objectification by men:

[I] take a few steps out of the make-up tent and look around. A middle-aged man in a cap stops. – I just have to say it, you look good, he says and keeps walking. […] Maybe it is so, [I] press up the fake breasts (Kriisa Citation2000).

Excluding trans expressions

Heteronormativity is further cemented by the creation of an image where trans people are unintelligible and devious. Three articles of a harder character, depict the legal process of a person defending their claim to change from a traditionally male name to a traditionally female one. One quoting a law stating that names should not cause “disgust to others or be assumed to lead to inconvenience to the bearer” (Johansson Citation2001) implies that when people do not conform to cisnormativity, they risk sickening others. The person’s preferred pronoun and gender is not stated in these articles. However, journalists assert otherness by an insensitive reference to the person’s gender:

The man is transvestite and wants to be named Christina (TT/Aftonbladet Citation2001).

The man who for a long time has been called Christina by friends and family is transsexual (Johansson Citation2001).

The provincial court reach the conclusion that the female name, considering the man lives openly as transvestite, cannot cause him the ‘discomfort’ of which the law speaks. (TT/Göteborgs-Posten Citation2001).

For four years Claes Schmidt has lived openly as Sara Lund […] he was supposed to speak on March 8th. (Abrahamsson Citation2008).

These examples show how trans people, rather than being forced into hetero- and cissexual norms, are excluded for not conforming fully in both anatomy and gender expression. The tactic ensures that the heteronormative order remains intact and legitimate by not acknowledging transgender expressions as genuine. These examples do not contain any examples of the journalists or featured voices self-positioning as trans people, rather it is cisgender people positioning trans people as the “deviant” others.

Silencing and Empowering Voices

In the following examples, two ways of including voices on trans issues were used – to position trans people, and self-identification with transgender identity. These cannot be considered discursive strategies themselves, nevertheless, still impact the constructions of trans representations in the articles.

Voicing trans issues through experts

Several articles intend to illuminate transgender issues using authority voices, finding like others, that news media rely heavily on experts (Capuzza Citation2014).

Legal and religious institutions restrict trans people in society, and experts also set the boundaries for transgender expressions in the newspaper articles studied. Here, stories are of a harder news character, published exclusively in morning papers around the time of the removal of the sterilisation law and connected to “Trans people B”. Therefore, it is not unexpected that the articles are often intertextually related to the pathologization of transgender people. This, in pointing to structural problems with how trans people are received in the health care system (Sjöström Citation2011), comparing sterilisation laws between USA and Sweden (TT/Dagens Nyheter Citation2011) and trans people victimisation by the government (TT/Dagens Nyheter Citation2013). In these articles, transgender people are passive and faceless, referred to only as “trans people” rather than naming individuals.

While the trans community might be better served through media directing their attention to hard news (Capuzza Citation2016), these representations can sometimes be counterproductive. An emeritus professor in women’s health argues for mandatory transition surgery to be allowed to change social security number, claiming the need to protect women in bathing facilities:

Because legal gender is only determined by social security number a man can without surgical correction, but with a female social security number demand entry to the women’s section. Is that desirable? (Bygdeman Citation2012).

Most of the articles speaking about, or on behalf of transgender people, do not do so as a means of suppressing rights. Just as in an article where an attorney and RFSL representatives were voiced in relation to a to lawsuit for forced sterilisation damages:

Kerstin Burman tells Svenska Dagbladet that she will demand at least 200 000 Swedish kronor per person. RFSL expect more to join (TT/Dagens Nyheter Citation2013).

Other have had a heartfelt wish for such a surgery but have due to the demand for sterilisation been prohibited to save sex cells that could mean parenthood. It was a big relief for many when the demand for sterilisation was put out of play (Gidlund et al. Citation2013).

Health care is gender conservative and is thereby causing transgender people unnecessary suffering, according to a new dissertation (Sjöström Citation2011).

Riggs (Citation2014) argues that even coverage intended to be inclusive, still might not be. Although structural issues are sometimes raised and recognised in this reporting, they are rarely questioned. Having no other voices, difference is suppressed. The journalists and experts state facts in these large conflicts related to trans representations in such a way that it makes trans people appear small and helpless. Despite these articles taking on real issues, it seems trans people are more frequently silenced in harder news, and despite often speaking on the behalf of trans people, the expert voices work as an oppressing hegemonic power, as they define meaning. They thereby assist in forming a discursive strategy that contributes to positioning trans people as victims.

Empowering trans voices

Representations of transgender people in the articles are here primarily male-to-female trans peopleFootnote7. However, the representations of female-to-male trans people in the sample are the most progressive. Here, in a different manner than presented so far, gender is “performed” as means of empowerment. Only one tabloid article represented trans people in this way and all five articles that could be considered progressive are written in the latter half of the studied period, possibly indicating a more positive trend in recent years.

These articles all have a sensitivity to pronouns and gender definitions in common, using preferred pronouns and the Swedish, gender-neutral pronoun hen. A transgender person is for instance described as following in a local news article:

For Ziggi Askaner there is no way of separating drag identity from gender identity. But zeFootnote8 is careful in pointing out that this is not the case for all non-binary or all drag artists (Wahlstedt Citation2016).

It should be recognised that the play with gender is, instead of being something insensitive and sensationalistic, something positive in these articles, aiming for a genuine and inclusive representation. The goal is to bend gender rules, as these two articles argue:

This is not about bringing out some inner man, it is more a game that messes with the two-gender norm (Lundström Citation2008).

It is in part about pushing the boundaries of what you can and cannot do as a woman, but also to try to destabilise the image of gender and dissolve the boundaries between femininity and masculinity. It is a resistance against the feminism that is based on biological sex and against heteronormativity (Andersen Citation2015).

Discussion

I have demonstrated how three primary discursive strategies were used by the journalists in their representation of trans people. Surprisingly, trans expressions were often carried out by cisgender men. These, often sensationalising tabloid depictions, led transgender expressions to be trivialised as dress-up. Echoing previous research, where transgender expressions are often delegitimised through offensive language use (Capuzza Citation2015, Citation2016; Gupta Citation2018; Hackl, Becker, and Todd Citation2016; Parks Pieper Citation2015; Willox Citation2003), different trans related terms were used interchangeably, without regard to their meaning, contributing to the reinforcement of stereotypes and heterosexual hegemony.

In line with previous research, media deployed a rigid view of gender, comparing and incorporating trans expressions into binary gender norms (Baptista and Himmel Citation2016; Espineira Citation2016; Glover Citation2016; Sloop Citation2000). While there are trans people who identify either as “man” or “woman”, the point here should not be to assign trans people a true gender (Squires and Brouwer Citation2002). Often, gender definitions were simply assumed and statements declaring the preferred definitions of trans people represented in the articles were absent. In order to improve their representations of trans people, news media must acknowledge and mediate people’s preferred gender definitions to a much larger extent.

Trans people were branded as deviant and deceiving in the reporting. This in some regards made trans people incomprehensible and “wrong”. It has been found to be a prominent part of media’s reporting on trans people (Capuzza Citation2016), as it is a way for the dominant, cisgender group to oppress and subordinate trans people (Billard, forthcoming) and ensures that the heteronormative order remains intact and legitimate by not acknowledging transgender expressions as genuine. Often, this trope of deception has been present in American reporting concerning violence against transgender people (e.g. Barker-Plummer Citation2013; MacKenzie and Marcel Citation2009; Sloop Citation2000). However, while also an issue in Sweden (Public Health Agency of Sweden Citation2015), depictions of violence were absent in the articles analysed.

The incorporation of “expert” voices is a common strategy deployed by news media (Capuzza Citation2014; Graber Citation2017) and worked here to make trans people weak and anonymous - pathologizing trans expressions. While Barker-Plummer (Citation2013) suggests that a “Wrong Body” representation by the media is better than marginalisation, it rids trans issues of complexity.

Through controlling whose perspective and voice was heard, news media trivialised, incorporated, excluded and silenced trans people. If these were the foremost ways in which heteronormativity was upheld, then the opposite strategies worked somewhat towards questioning it. Articles that in any real sense aimed to positively portray trans people, did so primarily through the voices of womenFootnote9 doing drag, by pointing to gender as constructs, and elevated, included and voiced trans people. However, these were not without issue. The voices were primarily allowed to speak only on issues of personal identity and these representations were still confined to “men” and “women”.

Research from around the world find that transgender people are becoming more visible in the media (Capuzza Citation2015; Mackie Citation2008; Roen, Blakar, and Nafstad Citation2011), and reporting on trans issues increased over time also in this paper. However, it is not enough for trans expressions to figure in news media, it is also crucial that these representations go further than simply reproducing stereotypes. While others have found increasingly positive media representations of trans people (Zhang Citation2014), Swedish news media still have far to go. Binary gendered language needs to be challenged in favour of more inclusive linguistic practices (Parks Pieper Citation2015). As gender is often only acknowledged if non-conforming (Barker-Plummer (Citation2013), a step towards enabling trans people would be either to disregard gender categorisations entirely or recognise all gender identity in news media reporting. Allowing trans people to speak on their own behalf, respectful uses of pronoun and gender definitions also seem decisive in empowering representations of trans people in this study and should always permeate news media’s language.

The concluding question needs to be whether a less rigid approach to gender norms is enough, when even the seemingly most progressive representations of gender in these articles relate trans expressions to the gender dichotomy? Westbrook (Citation2010) argues that depictions of transgender people stabilise heteronormativity, as trans people are identified in terms of gender. In these articles non-conforming transgender identities were absent, thus contributing to reinforcing cisnormative values (Capuzza Citation2014). Despite Sweden being considered among the most progressive countries in the world in terms of transgender rights, when society is so rigorously structured around cis- and heteronormativity, no other forms of identity can ever be completely embraced, and news media’s language will continue to reflect that.

Stereotypical representations of transgender people in the news may have negative influence on popular beliefs about gender diversity (Capuzza Citation2014) and not to mention on trans people themselves (Ringo Citation2002). The present study has begun to explore how Swedish mainstream press works as a means of both maintaining and challenging heteronormativity and how featured voices have contributed to these representations. However, representations of trans people in Swedish media are vastly under-explored. Future studies should investigate representations of trans people also in broadcasted news and on social media.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Dr. Samuel Merrill at Umeå University for your advice and input on earlier versions of this manuscript. Many thanks also to the anonymous reviewers whose feedback greatly improved this article.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. Transwoman is defined as a person anatomically born male, living or expressing female. Male-to-Female (MtF).

2. Cis is Latin for ‘on the same side’ (Ambjörnsson Citation2016, 96), describes a non-transgender person.

3. The complexity of the publishing process is recognised but journalist is used throughout when referring to the article producer.

4. Intentional, as well as unconscious strategies.

5. bigender*, FtM*, genderqueer, non-binary*, intergender*, intersex*, MtF*, non-gender* and pansex*.

6. Average of 472 words without one considerably longer article.

7. 6 identified as FtM, 5 as MtF, and 5 cis gender male trans expressions.

8. ze (nominative reflexive) and translated from the Swedish hen.

9. People defined by the journalists as born anatomically female, not considering current expressed gender.

REFERENCES

- Abrahamsson, Karin. 2008. ““Pingstkyrka säger nej till transvestit” [Pentecostal Church turns down transvestite]. Aftonbladet.” March 5.

- Ambjörnsson, Fanny. 2016. Vad är Queer? [ What is Queer?]. 2nd ed. Stockholm: Natur & kultur.

- Andersen, Ivar. 2015. “Målet: Att få vara människa” [The goal: To be human]. Expressen, August 1.

- Arune, Willow. 2006. “Transgender Images in the Media.” In News and Sexuality: Media Portraits of Diversity, edited by Laura Castañeda, and Shannon B. Campbell, 110–133. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Baptista, Maria, and Rita Himmel. 2016. “‘For Fun’: (De) Humanizing Gisberta — The Violence of Binary Gender Social Representation.” Sexuality & Culture 20 (3): 639–656. doi:10.1007/s12119-016-9350-5.

- Barker-Plummer, Bernadette. 2013. “Fixing Gwen: News and the Mediation of (Trans)Gender Challenges.” Feminist Media Studies 13 (4): 710–724. doi:10.1080/14680777.2012.679289.

- Bauer, Greta R., Rebecca Hammond, Robb Travers, Matthias Kaay, Karin M. Hohenadel, and Michelle Boyce. 2009. “‘I Don’t Think This Is Theoretical; This Is Our Lives’: How Erasure Impacts Health Care for Transgender People.” Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 20 (5): 348–361. doi:10.1016/j.jana.2009.07.004.

- Billard, Thomas J. 2016. “Writing in the Margins: Mainstream News Media Representations of Transgenderism.” International Journal of Communication 10: 4193–4218.

- Billard, Thomas J. forthcoming. “‘Passing’ and the Politics of Deception: Transgender Bodies, Cisgender Aesthetics, and the Policing of Inconspicuous Marginal Identities.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Deceptive Communication, edited by Tony Docan-Morgan. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Blei, David M. 2012. “Topic Modeling and Digital Humanities.” Journal of Digital Humanities 2 (1).

- Blei, David M., Andrew Y. Ng, and Michael I. Jordan. 2003. “Latent Dirichlet Allocation.” Journal of Machine Learning 3 (4-5): 993–1022. doi:10.1162/jmlr.2003.3.4-5.993.

- Butler, Judith. 1990. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge.

- Bygdeman, Marc. 2012. “‘En man som bytt kön till kvinna ska inte kunna bli far’” [‘A man who changed gender should not be able to become a father’]. Dagens Nyheter, March 31.

- Capuzza, Jaime C. 2014. “Who Defines Gender Diversity? Sourcing Routines and Representation in Mainstream U.S. News Stories About Transgenderism”. International Journal of Transgenderism 15 (3–4): 115–128. doi:10.1080/15532739.2014.946195.

- Capuzza, Jamie C. 2015. “What’s in a Name? Transgender Identity, Metareporting, and the Misgendering of Chelsea Manning.” In Transgender Communication Studies: Histories, Trends, and Trajectories, edited by Leland G. Spencer, and Jamie C. Capuzza, 93–110. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- Capuzza, Jaime C. 2016. “Improvements Still Needed for Transgender Coverage.” Newspaper Research Journal 37 (1): 82–94. doi:10.1177/0739532916634642.

- Chang, Jonathan, Jordan L. Boyd-Graber, Sean Gerrish, Chong Wang, and David M. Blei. 2009. “Reading tea Leaves: How Humans Interpret Topic Models.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 22: 288–296.

- Cloud, Dana L. 2014. “Private Manning and the Chamber of Secrets.” QED 1 (1): 80–104. doi: 10.14321/qed.1.1.0080

- Eriksson, Jenny. 2011. “Manligt Mode ‘Man blir felaktigt klassad som transvestit’” [MALE FASHION ‘You are wrongly classed as transvestite’]. Sydsvenskan, November 22.

- Ernhagen, Silvia. 2008. “RFSU välkomnar Socialstyrelsens beslut om att inte klassa BDSM som en sjukdom” [RFSU welcomes the Public Health Agency of Sweden’s decision to not class BDSM as an illness]. RFSU. November 17. http://www.rfsu.se/sv/Sex--relationer/Sexteknik-och-praktik/BDSM/RFSU-valkomnar-Socialstyrelsens-beslut--att-inte-klassa-BDSM-som-sjukdom.html.

- Espineira, Karine. 2016. “Transgender and Transsexual People’s Sexuality in the Media.” Parallax 22 (3): 323–329. doi: 10.1080/13534645.2016.1201922

- Fairclough, Norman. 1992. Discourse and Social Change. Cambridge: Polity.

- Fairclough, Norman. 1995. Media Discourse. London: Edward Arnold.

- Fairclough, Norman. 2001. Language and Power. 2nd ed. Harlow: Longman.

- Fairclough, Norman. 2003. Analysing Discourse: Textual Analysis for Social Research. New York: Routledge.

- Fairclough, Norman. 2010. Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language. 2nd ed. Harlow: Longman.

- Gidlund, Lina, Kerstin Burman, Alfie Martins, Ulrika Westerlund, Immanuel Brändemo and Gisela Janis. 2013. “‘Rättighet att slippa påtvingade ingrepp’” [‘The Right to not have to undergo forced procedures’]. Dagens Nyheter, August 16.

- Glover, Julian Kevon. 2016. “Redefining Realness? On Janet Mock, Laverne Cox, TS Madison, and the Representation of Transgender Women of Color in Media.” Souls 18 (2-4): 338–357. doi: 10.1080/10999949.2016.1230824

- Graber, Shane M. 2017. “The Bathroom Boogeyman: A Qualitative Analysis of How the Houston Chronicle Framed the Equal Rights Ordinance.” Journalism Practice, online first 12: 870–887. doi:10.1080/17512786.2017.1358651.

- Gupta, Kat. 2018. “Response and Responsibility: Mainstream Media and Lucy Meadows in a Post-Leveson Context.” Sexualities, online first. 10: 136346071774025. doi:10.1177/1363460717740259.

- Hackl, Andrea M., Amy B. Becker and Maureen E. Todd. 2016. “‘I Am Chelsea Manning’: Comparison of Gendered Representation of Private Manning in U.S. and International News Media.” Journal of Homosexuality 63 (4): 467–486. doi:10.1080/00918369.2015.1088316.

- Heber, Anita. 2011. “Fear of Crime in the Swedish Daily Press – Descriptions of an Increasingly Unsafe Society.” Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention 12 (1): 63–79. doi:10.1080/14043858.2011.561623.

- ILGA-Europe. 2015. ILGA-Europe Rainbow. http://www.ilga-europe.org/sites/default/files/Attachments/side_a_rainbow_europe_map_2015_a3_no_crops.pdf.

- Johansson, Lars-Ove. 2001. “Christina alltför feminint för en man” [Christina too feminine for a man]. Göteborgs-Posten, November 20.

- Joo, Natalie. 2007, January 22. “Robbies nya look [Robbie’s new look]. Expressen, January 22.

- Kriisa, Lennart. 2000. “Vi bytte kön för en dag. Expressens reportrar passade på att ta steget fullt ut” [Vi changed genders for a day. Expressen’s reporters took the leap fully]. Expressen, August 5.

- Li, Minjie. 2018. “Intermedia Attribute Agenda Setting in the Context of Issue-Focused Media Events: Caitlyn Jenner and Transgender Reporting.” Journalism Practice 12 (1): 56–75. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2016.1273078

- Lindstedt, Karin. 2002. “‘Jag ville sjunga i kvinnokläder’” [‘I wanted to sing in female clothing’]. Aftonbladet, January 31.

- Lindwall, Johan T. 2010. “SNYGGA BEHN, ARI!” [NICE LEGS (BEHN), ARI!] Expressen. September 1.

- Lundström, Anna. 2008. “Tjejer förvandlas till män hos dragking-Lina” [Girls are turned into men at drag king Lina’s]. Västerbottens-Kuriren, September 26.

- MacKenzie, Gordene, and Mary Marcel. 2009. “Media Coverage of the Murder of U.S. Transwomen of Color.” In Local Violence, Global Media: Feminist Analyses of Gendered Representations, edited by Lisa M. Cuklanz, and Moorti Sujata, 79–106. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Mackie, Vera. 2008. “How to be a Girl: Mainstream Media Portrayals of Transgendered Lives in Japan.” Asian Studies Review 32 (3): 411–423. doi: 10.1080/10357820802298538

- McCallum, Andrew Kachites. 2002. MALLET: A Machine Learning for Language Toolkit. http://mallet.cs.umass.edu.

- McCarthy, Justin. 2015. “European Countries among Top Places for Gay People to Live.” Gallup, June 26. http://www.gallup.com/poll/183809/european-countries-among-top-places-gay-peoplelive.aspx?utm_source=World&utm_medium=newsfeed&utm_campaign=tiles.html.

- McQuail, Denis. 1994. Mass Communication Theory: An Introduction. 3rd ed. London: SAGE Publications.

- Meyerowitz, Joanne. 1998. “Sex Change and the Popular Press: Historical Notes on Transsexuality in the United States, 1930–1955.” GLQ 4 (2): 159–187. doi: 10.1215/10642684-4-2-159

- Parks Pieper, Lindsay. 2015. “Mike Penner ‘or’ Christine Daniels: the US Media and the Fractured Representation of a Transgender Sportswriter.” Sport in Society 18 (2): 186–201. doi:10.1080/17430437.2013.854472.

- Public Health Agency of Sweden. 2015. “ Hälsan och hälsans bestämningsfaktorer för transpersoner. En rapport om hälsoläget bland transpersoner i Sverige [Health and the decisive factors of health for trans people.” A rapport on the current health situation amongst Swedish trans people] https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/contentassets/a55cb89cab14498caf47f2798e8da7af/halsan-halsans-bestamningsfaktorer-transpersoner-15038-webb.pdf.

- RFSL. 2015. Begreppsordlista [Glossary]. http://www.rfsl.se/hbtq-fakta/hbtq/begreppsordlista/.html.

- Riggs, Damien W. 2014. “What Makes a man? Thomas Beatie, Embodiment, and ‘Mundane Transphobia’.” Feminism & Psychology 24 (2): 157–171. doi:10.1177/0959353514526221.

- Ringo, Peter. 2002. “Media Roles in Female-to-Male Transsexual and Transgender Identity Formation.” International Journal of Transgenderism 6 (3).

- Rosenberg, Tina. 2011. Queerfeministisk Agenda [Queer Feminist Agenda]. Stockholm: Atlas.

- Roen, Katrina, Rolv Mikkel Blakar, and Hilde Eileen Nafstad. 2011. “‘Disappearing’ Transsexuals? Norwegian Trans-discourses, Visibility, and Diversity.” Psykologisk Tidsskrif 1: 28–33.

- Ryan, Joelle Ruby. 2009. “Reel Gender: Examining the Politics of Trans Images in Film and Media.” PhD diss., Bowling Green State University.

- Schilt, Kristen, and Laurel Westbrook. 2009. “Doing Gender, Doing Heteronormativity: ‘Gender Normals’, Transgender People, and the Social Maintenance of Heterosexuality.” Gender & Society 23 (4): 440–464. doi:10.1177/0891243209340034.

- Schippers, Mimi. 2007. “Recovering the Feminine Other: Masculinity, Femininity, and Gender Hegemony.” Theory and Society 36 (1): 85–102. doi:10.1007/s11186-007-9022-4.

- Scott, David and Ann Enander. 2017 “Postpandemic Nightmare: A Framing Analysis of Authorities and Narcolepsy Victims in Swedish Press.” Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 25 (2): 91–102. doi: 10.1111/1468-5973.12127

- Serano, Julia. 2007. Whipping Girl: A Transsexual Woman on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Femininity. Emeryville, CA: Seal.

- SFS 2013:405. Lag om ändring i lagen (1972:119) om fastställande av könstillhörighet i vissa fall. [ Changes to the Act (1972: 119) regarding determination of gender in some cases]. Stockholm: Ministry of Health and Social Affairs.

- Sjöström, Mia. 2011. “Transvård orsakar onödigt lidande” [Trans care causes unnecessary suffering]. Svenska Dagbladet, November 22.

- Skidmore, Emily. 2011. “Constructing the ‘Good Transsexual’: Christine Jorgensen, Whiteness, and Heteronormativity in the mid-Twentieth-Century Press.” Feminist Studies 2 (37): 270–300.

- Sloop, John M. 2000. “Disciplining the Transgendered: Brandon Teena, Public Representation, and Normativity.” Western Journal of Communication 64 (2): 165–189. doi: 10.1080/10570310009374670

- Squires, Catherine, and Daniel Brouwer. 2002. “In/Discernible Bodies: the Politics of Passing in Dominant and Marginal Media.” Critical Studies in Media Communication 19 (3): 283–310. doi:10.1080/07393180216566.

- TT/Aftonbladet. 2001. “Transvestit får heta Christina” [Transvestite gets the right to be named Christina]. Aftonbladet, March 3.

- TT/Dagens Nyheter. 2011. “Thomas Beatie inviger Pride” [Thomas Beatie inaugurates the Pride festival]. Dagens Nyheter, August 1.

- TT/Dagens Nyheter. 2013. “Transpersoner kräver skadestånd” [Trans people demand legal damages]. Dagens Nyheter, January 11.

- TT/Göteborgs-Posten. 2001. “Nu får han heta Christina” [Now he can be named Christina]. Göteborgs-Posten, March 5.

- Wahlstedt, Sally. 2016. “Glitter och rakskum utmanar könsgränserna” [Glitter and shaving foam challenges gender boundaries]. Sydsvenskan, August 2.

- Westbrook, Laurel. 2010. “Becoming Knowably Gendered: The Production of Transgender Possibilities and Constraints in the Mass and Alternative Press from 1990–2005 in the United States.” In Transgender Identities: Towards a Social Analysis of Gender Diversity, edited by Sally Hines, and Tam Sanger, 43–63. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Westbrook, Laurel, and Kristen Schilt. 2014. “Doing Gender, Determining Gender: Transgender People, Gender Panics, and the Maintenance of the Sex/Gender/Sexuality System.” Gender & Society 28 (1): 32–57. doi: 10.1177/0891243213503203

- Willox, Annabelle. 2003. “Branding Teena: (Mis)Representations in the Media.” Sexualities 6 (3–4): 407–425. doi: 10.1177/136346070363009

- Zhang, Qing Fei. 2014. “Transgender Representation by the People’s Daily Since 1949.” Sexuality & Culture 18 (1): 180–195. doi: 10.1007/s12119-013-9184-3

Appendix A

Overview of topics