Abstract

Over the latest decade, the availability of news media from various countries of the globe has increased dramatically as both media production and consumption have been steered towards digital and social platforms. This de-territorialized news ecology has been widely researched in terms of content and distribution, while its broader consequences for news audiences have been less studied. Focusing on the case of Sweden, this article analyses social variations in transnational news consumption including platform selections, motivations, and attitudes connected to this news use. Results show that transnational news consumption is more widespread among people with a background in other countries than Sweden, but all together, more than a quarter of the Swedish population and nearly half of the younger generation are weekly consumers of news from other countries. Hence, transnational news consumption is no longer restricted to a specific elite-segment of society, which has been a common argument in scholarly debates around the globalization of news. Another central finding is that transnational news consumption is rooted in a willingness to understand the outside world through alternative perspectives, rather than in a dissatisfaction with the quality or trustworthiness of the news produced by Swedish outlets.

Introduction

On the 8th of February 2017, US president Donald J. Trump held a public rally in Florida where he mentioned an incident in Sweden as an example of the dangers facing countries that are open to migration. Given that nothing special had happened, “last night in Sweden” rapidly became a globally discussed topic as news institutions and social media users started to speculate about the meaning of Trump’s words. Former prime and foreign minister of Sweden, Carl Bildt, who first responded on Twitter with the question “What has he been smoking?”, presented a more serious criticism in a column of the Washington Post some days later entitled “The truth about refugees in Sweden”.Footnote1 The Swedish anti-immigration party, The Sweden Democrats, responded in a parallel article published in The Wall Street Journal entitled “Trump is right: Sweden’s Embrace of Refugees Isn’t Working”.Footnote2 Trump himself later admitted on Twitter that what he was referring to in the speech was a news report on Fox News, depicting multicultural Sweden in turmoil.Footnote3 This, in turn, sparked reactions among numerous Swedish news media institutions, who started to publish articles in English as a way of counteracting Fox News’ “sweeping statements, exaggerations and clear errors” by providing “the real story” for an international audience.Footnote4 Concurrently, the coverage written for the Swedish audience included hyperlinks to international news sites and social media accounts as the intensity of the debate escalated.

These examples, from the global Fox News story and Trump’s speech and tweets, to the international counter-initiatives of Swedish politicians and journalism institutions, are key indicators of an increasingly transnational media environment where cross-border flows of information challenge domestic forms of news production and consumption. Moreover, they illuminate that foreign news media—just like social media—can serve as discursive spaces for both inter-national and intra-national political debates. As Richard Jomshof, party secretary of the Sweden Democrats, put it in an interview with Swedish Public Service Television: “The world is global, news travel from one part of the world to another. An opinion piece in the USA makes it visible also in Europe and Sweden” (SVT Citation2017).Footnote5 Hence, the formerly sharp lines between domestic and foreign news consumption are becoming less distinct as the open borders of the Internet enables immediate access to other countries’ news on a daily basis and in real-time. This digital mobility of content across borders raises new questions regarding transnational news consumption both in Sweden and elsewhere.

Over the past decade, the availability of foreign news media across the globe has increased dramatically as both media production and consumption of journalism have been steered towards digital and social platforms. Online environments in general, and social media platforms in particular, allow for blended and highly personalized news feeds (Thurman Citation2011), reflecting an increasingly de-territorialized online news ecology inhabited by media institutions that easily can cross borders and distribute content to audiences on a transnational scale (Athique Citation2016; Heinrich Citation2012). Likewise, giant secondary gatekeepers such as Google and Facebook generate Internet traffic to news companies based on individual consumption patterns, social affinity and “user-generated visibility” within digital networks rather than solely on geography or language (Nielsen Citation2017; Singer Citation2014).

Tendencies toward collapsing spatial boundaries of journalism have been a key theme in media studies for many years, especially with regard to content and distribution (e.g. Chalaby Citation2005; Thurman Citation2007; Reese Citation2010). Plenty of studies have also looked at transnational media habits of migrants and diaspora communities, particularly from an ethnographic lens (cf. Christiansen Citation2004; Georgiou Citation2006; Khvorostianov, Nelly, and Nimrod Citation2012). There is, however, a dearth of research that discusses broader patterns of transnational news consumption beyond specific groups or consumption contexts.

The aim of this article is to map the reach and character of transnational news consumption in Sweden, and moreover identify what motives and attitudes that are associated with this consumption during times of enhanced digital mobility of media content across countries and regions. Transnational consumption is defined here as consumption of “foreign news media”, e.g. any type of news produced by media companies outside of Sweden, irrespectively of language, platform, market, target group or country of origin. Hence, this very broad category includes everything from global news channels and international business news, to national or local newspapers and various types of specialized niche news products on all types of platforms. Content mobility, in turn, refers to journalism’s increased capacity to reach out beyond preferred audiences and territories, especially in online and social media contexts. Hence, content mobility may disembed audiences from previously solid national zones of consumption in ways that have been addressed to a fairly marginal extent in previous research. Sweden is an interesting case for the study of transnational news consumption for several reasons. The country is among the most digitalized in the world, with high levels of Internet use (Eurostat Citation2016) as well as high levels of news consumption (Nordicom-Sveriges Mediebarometer Citation2017). Sweden is also a country that has been open for migration during several decades. Thus many people may have information needs or geographical news preferences that Swedish news media seldom cater to (Hultén Citation2016). Against this background, the article addresses the following research questions:

How widespread is transnational news consumption in Sweden and what platforms are most commonly used?

How does the consumption vary depending on social factors such as age, education-level, geography, political interest, homeland during childhood and broader patterns of news media use?

What social and professional motives are connected to transnational news consumption?

How do high consumers of news from other countries perceive the quality and trustworthiness of these services compared to Swedish news?

The article is structured as follows. The theoretical framework entwines research on the social and cultural functions of journalism in both national and global contexts with previously identified patterns of news consumption in Sweden. The subsequent section describes the survey and the empirical data including notes on some of the limitations of the method. This is followed by results, where transnational news consumption in Sweden and attitudes towards foreign news services are dissected. The article ends with a concluding discussion and suggestions for future research in the area.

The Sociality of Journalism: From Embedding to Disembedding and Back Again

Journalism is an institution of such a strong socio-historical significance that it has been labeled “the primary sense-making practice of modernity” (Hartley Citation1996, 12). As such, it has played a key role in debates around the quality and nature of the public sphere and it has also been understood as a provider of a cultural and social glue, connecting people across time and space through simultaneous and collective mediated experiences (Dahlgren Citation1995; Thompson Citation1995; Schudson Citation2003). The media’s ability to foster cultural integration and senses of belonging is often associated with Benedict Anderson’s (Citation1983) seminal work on “imagined communities” where he draws historical lines between print capitalism, audience formations and the cultivation of national identity. The centrality of the nation-state for political organization, common language, local advertising markets and political regulations are some of the overarching mechanisms behind journalism’s primarily national outlook. In addition, a crucial driving force behind news consumption has always been that people want to engage in issues and events that are relevant to their immediate everyday life (Barnhurst and Nerone Citation2001; Schudson Citation2003).

A distinctive feature of our time, however, is that local and national communities including nation-states are put under pressure by accelerating processes of globalization and individualization. Potentially, globalization adds new social layers to existing modes of cultural identification, and individualization, in turn, forces the individual to constantly choose between a multitude of identity positions (Beck and Levy Citation2013; Beck and Beck-Gernsheim Citation2002; Dahlgren Citation1995). Media is a central driving force in such processes of “disembedding” individualization (Giddens Citation1991b); in today’s online, multi-channel media world, the availability is almost endless as journalism from practically all countries of the globe is available on the Internet. The link between cultural globalization and potential variations in the way people select their news sources is not a new phenomenon in media research. In a US context, changes towards individualization in television habits were recognized for example by Ien Ang (Citation1996) already in the 1990s. In light of the simultaneous expansion, commercialization, internationalization and diversification of television, she saw the advent of specialized and personalized viewing patterns as expressions of a post-modern society, inhabited by citizens that use media as stimuli for individual interests, rather than as a source for broader collective experiences. In such situations, the cultural glue of television broadcasting becomes less “sticky”; with the increase in availability comes a decrease in the media’s ability to integrate people socially and culturally in the same ways as they did in the past (Bjur Citation2009; Syvertsen et al. Citation2014). Global “mediascapes”, to use the terminology of Arjun Appadurai (Citation1996), have a potential to uncoupling cultural representations from place, and thereby they can contribute to a heterogenization in available media formats as well as a fragmentation of audiences across previously solid (and primarily national) borders through diverse forms of transnational social imaginary. Appadurai’s argument was formulated in a different media environment than the one we witness today, but media scapes have since then become an even more significant element in processes of globalization due to the borderless infrastructure of the Internet.

Adjacent debates around media globalization have often revolved around the logics and significance of media institutions that actively target audiences on a transnational or global scale. Research, primarily on television, has showed that some global news broadcasters have developed new frameworks of news reporting, challenging the predominantly national ontology of most journalism institutions (Chalaby Citation2005; Robertson Citation2015; Widholm Citation2011). More pessimistic analyses of the same institutions see them as reflections of informational power struggles or “public diplomacy” between nation-states and foreign publics (Rai and Cottle Citation2007; Seib Citation2010). There are, however, also researchers that point to global journalism as an emerging news style which is activated when journalists describe problems through a diverse geographical outlook, and through a mix of domestic, foreign and global forms of representation. According to Berglez (Citation2013) such a news style is not bound to specific global media institutions, but can and have been adopted also by local and national media for example in depictions of truly global issues such as climate change.

Although these analyses often come to different conclusions regarding the consequences of media globalization, they seldom take a firm grip on one of the most fundamental aspects of this development, namely how news consumers respond to the growing global availability on the news market. About a decade ago Hafez (Citation2007) came to the conclusion that media globalization is a widespread academic myth, based on a failed distinction between technological reach and user reach. Commercial viewing statistics for global news channels still show very low figures, and those who are targeted as well as those who tune in tend to belong to the cosmopolitan elite segment of society, far from the living rooms of so-called ordinary people (cf. Ipsos Citation2015; Widholm Citation2016). Hafez clearly had a point when arguing that we need to approach media globalization with a large proportion of prudence. However, the impossibility of “the global” should not make us blind to how the structures of today’s media environment may push news consumers in a more transnational direction. News companies are no longer dependent on complex broadcasting infrastructures, national and international policy regulations or physical distribution, which makes even a small local newspaper or a niche outlet on for instance YouTube a potential cross-border news actor under the right circumstances. Thus, journalism of today comprises a tremendously long tale (e.g. Anderson Citation2009) of actors, representing a wide array of perspectives and viewpoints. What these actors have in common is their immediate technical reach online. Athique (Citation2016) has argued that media research needs to address this increasing multiplication of sources online in terms of a transnational mobility of content across borders including how various forms of media products reach large numbers of so-called “non-resident” audiences. That is, in the words of Giddens (Citation1991a), to see news users as spatially “disembedded”. Disembedding, in this context, is the “lifting out of social relations” (p. 18) from a primarily local/national scale to a transnational or global scale. Most news institutions are still marked by a national bias, but their informational dominance in certain spaces or territories has been increasingly challenged due to the borderless infrastructure of the Internet. This reinforced de-territorialization underlines news journalism as a resource for a transnational reflexivity, which may spark doubts about the “natural” perspectives presented by for example local newspapers or the national public service news on television in a country like Sweden. Disembedding can in that sense also generate re-embedding effects which may appear when news consumers to a larger extent replace rather than expand their news repertoire towards journalism from other countries. Central aspects that may influence such a process are perceived quality, relevance and trustworthiness of foreign news media vs domestic news media (see the method section for how these aspects are operationalized and analyzed). To date, media research has showed little interest in the extent to which people actually take advantage of this bulge of news—and how. A large body of research, however, has focused on changes related to local and domestic news contexts. This is discussed in the next section with a particular focus on Sweden.

Uses of News: Possibilities and Obstacles in a Changing Media Environment

Sweden is often described in media research as an example of a democratic corporatist media system (Hallin and Mancini Citation2004), which includes a high degree of newspaper circulation and consumption combined with strong public service media institutions that offer both local and national news in radio and television. In terms of media policy, this has also been understood as an extension of the welfare systems characterizing primarily the Scandinavian countries, where non-commercial news provision in tandem with a commercial press have served the democratic needs for all citizens of a “media welfare state” (Syvertsen et al. Citation2014). However, in the current era of digitalization and globalization, the broad consumption patterns of news across social groups and generations have started to erode. Recent years’ media research in Sweden has showed a decline in news consumption connected to for example television and printed newspapers, especially in the younger age groups. Young people have always consumed news to a less extent than older generations, but the news gap has increased over time (Wadbring, Weibull, and Facht Citation2016). Besides age, typical generative mechanism related to news consumption are political interest, education level and social class (although the media welfare state has sought to minimize their effects). Also these factors have proved to be increasingly important for news media consumption over time, even though age seems to the most important one (Andersson 2016; Ohlsson Citation2015). In times of growing availability, individual choices and preferences plays a more central role for the daily media diet. Paradoxically, this means that while there has never been more news around than today, it has never been easier to also avoid the news in favor of other types of content. For some, this development represents a new and broader distinction in society between “news seekers” and “news avoiders” which may have negative effects on social cohesion and democratic participation in the society (Aalberg, Blekesaune, and Elvestad Citation2013). More positive interpretations of the development point to the increase in social media use, especially in younger generations. Studies have showed that as many as 90 percent of young people in Sweden use social media on a daily basis, and these platforms have also become increasingly central also for consumption of news (Jervelycke Belfrage and Bergström Citation2017). Studies have also concluded that young people do show a strong interest in news, but their media habits and platform prioritizations are distinctly different from those of the older generations (Wadbring Citation2016). Thus, there is a polarization not only between those who consume news or not, but also between those who turn to traditional analogue sources vs. those who turn to social media platforms (Andersson 2016). Young news consumers are in that sense moving targets for the media industry, and they are seldom faithful to the same news brands year after year like the habits of older generations. Instead, their news consumption has been described as increasingly random, bound to the omnipresence of mobile and social media in the everyday “media life” (Antunovic, Parsons, and Cooke Citation2016; Deuze Citation2012; Jervelycke Belfrage and Bergström Citation2017). Furthermore, online news environments such as Facebook and Twitter provide “opportunities for people to encounter news in an incidental way as a byproduct of their online activities” (Yadamsuren and Erdelez Citation2010, 1). By collecting large amounts of behavioral user data, such media companies can also personalize their feeds and match global advertizers with local consumers, while still providing “an illusion of free choice” for their users (Appelgren Citation2017).

As indicated in above, the complex blending of different types of content in people’s social media feeds is paradoxical. On the hand news flows are individualized and generated by algorithms, specifically sensitive to personal interests and social affinity. On the other hand, the exposure of this news is often beyond the direct control of individual users, since much content on social media is generated and re-distributed by other members and actors in their networks (Nielsen Citation2017). According to Singer (Citation2014), such “user-generated visibility” involves people that “see as a natural part of their digital news experience the ongoing process of determining not only what is valuable to them as individuals but also what they believe will be important, interesting, entertaining, or useful to others” (Singer Citation2014, 58). A result of this development is that journalism of various sorts may be re-distributed to audiences that are considerably larger or broader than the audience it was originally intended and designed for. As noted by Jung (Citation2016), journalism is increasingly intertwined with “cross-level story flows”, especially in social media, where “a local story can move up to the global sphere without going through local mass media or other formal institutional routes” (Jung Citation2016, 2). This represents a re-scaling of journalism’s spatial boundaries from local and national to translocal and transnational depending on the type and character of the stories that go viral. Since young people tend to be more extensive online and social media users, they are also more likely to be exposed for that type of journalism (although we in empirical terms still no very little about this particular aspect of contemporary news consumption).

Despite the increasingly networked logics of news production and consumption outlined above, old obstacles such as language differences co-exist with the new transnational opportunities. Athique (Citation2016) notes that the language of the media is culturally and geographically situated, but it does not mean that media content in one country is impossible to understand somewhere else. He points for instance to language regions such as the Anglosphere, the Spanish sphere, and the Arab sphere where the mobility of media content works particularly smoothly since it is mutually comprehensible. Likewise, Sweden can be said to be part of a Scandinavian sphere, comprising journalism produced in Danish, Norwegian and Swedish. In order to transcend language boundaries, several news broadcasters, for example CNN, RT, Euronews, and Al-Jazeera, produce news in multiple language editions (Widholm Citation2011). For those who do not, Google as well as platforms such as Facebook and Instagram provide rapid automatic translation in a variety of languages directly in their user feeds. Although far from perfect, these translation services involve a great potential as vehicles for transnational content mobility.

At last, it is important to briefly address the question of language and foreign news media in relation to historical as well as more contemporary migration flows to Sweden. In 2016, 20 percent of the Swedish population had a background in another country than Sweden (Migrationsinfo Citation2017). Sweden’s generous migration policies date back to the post-war period of the 1950s when labor migration primarily from Scandinavia and a few European countries was extensive as a result of a thriving Swedish industry. In the 1970s, this policy was more or less abandoned and replaced by a more geographically varied asylum migration including migrants from countries such as Chile, Iran, Iraq, countries of former Yugoslavia and more recently Syria. Thus, lots of people of different generations may not necessarily quench their news thirst through consumption of Swedish news media only. A previous study of media consumption among immigrants in Sweden carried out in the early 2000s showed significantly lower levels of consumption of for example Swedish newspapers compared to the population in general (Wadbring Citation2001). The same study also pointed to a more prevalent usage of foreign newspapers and magazines in this group. As noted in the introduction, however, few studies have elaborated these findings in a digital and social media context. In addition, there are no studies of how the population at large have responded to the ever-growing availability of news from other countries.

Method and Data

The study builds on representative nation-wide survey data collected in cooperation with the Swedish SOM Institute (Society, Opinion, Media) during the autumn of 2015 and the spring of 2016. The SOM Institute has conducted statistically representative surveys in Sweden for more than 20 years. The method for data collection is systematic probability sampling, and the questionnaire used in this study went out by traditional mail to 3400 people living in Sweden, aged between 16 and 85. To increase the response rate, respondents could also submit their answers online. 1575 respondents (48,9 percent) answered the survey.

Respondents were asked how often they consume news journalism from other countries than Sweden, what platforms they use, as well as a series of questions relating to motives and attitudes towards journalistic quality and trustworthiness. The questions were designed so that they could capture three dimensions of transnational news consumption practices: habits, motives and attitudes. The questions were also constructed in such a way that they could generate knowledge about differences and relationships between domestic and transnational forms of news consumption. Questions on habits focused on frequency in usage on different platforms. Questions on motives tried to capture professional, social as well as informational dimensions. Attitudes, at last, were captured in terms of perceived quality. All questions and response options are detailed below.

Habits

How often do you consume news media from other countries than Sweden? The question could be answered for seven different platforms/media types: Newspaper, newspaper online, TV, TV online, Radio/podcast, social media, and other news service. The Response options were: Daily, 5–6 days a week, 3–4 days a week, 1–2 days a week, more seldom, and never. The same scale has been used in the national SOM survey for many years, yet with a focus on consumption of Swedish news media.

Motives and Attitudes

For what reasons do you consume news from other countries? Seven motives were given to which the respondents could respond on a four-point Likert-scale. The options were: completely correct, fairly correct, fairly incorrect, and totally incorrect. The motives were defined as follows:

They provide different perspectives than Swedish news media

They help me understand the outside world

They provide news in my mother tongue

They provide news about areas where I have relatives and friends

It is part of my work

They keep a higher quality than Swedish news media

They are more trustworthy than Swedish news media

Background Variables

Besides questions on attitudes and habits, the survey captured background variables such as region of residence, home country during childhood, age, education, and (Swedish) news media habits. As to consumption of Swedish news, the analysis draws on standard survey questions on readership of local and national newspapers and viewing/listening connected to Swedish public service radio and television. These are used as independent variables, illuminating potential differences between high and low/non-users of foreign news media. Chi-square test has been conducted to determine significant differences, and Cramer’s V to determine the strength of the association between variables in bivariate analyses.

Results

This section starts with a description of the overall transnational news consumption in Sweden including platform selection. This is followed by an analysis of factors related to high consumption and variations within different social groups. The third and final sections sets the focus on perceived quality and trustworthiness in comparison with Swedish news.

Habits: Scope and Platform Selection

At first glance, transnational news consumption in Sweden appears to be a highly marginal phenomenon, considering that the overall time spent on media has increased over the latest decade. The daily news consumption of news from other countries is low, varying from four per cent for television (which is the most popular daily medium), to three percent for online newspapers and around one percent for radio and printed newspapers. Thus, on many media platforms, and especially printed newspapers, the daily transnational news consumption is nearly non-existent ().

TABLE 1 Usage of foreign news media on different platforms (percent)

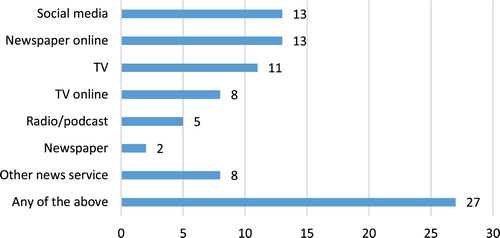

The picture does not change dramatically if we switch focus to those who use these media slightly more often. The numbers are still relatively low, but online newspapers and social media stand out as the most popular platforms. The patterns thus reflect a usage that is clearly different from the consumption of domestic news, which on the one hand is strongly rooted in traditions and social structures of everyday life (such as reading a newspaper in the morning or watching the evening newscast on television), and on the other hand related to a growing mobile news consumption, satisfying new digital needs of the present 24-hour news culture. There are both time, language and culture barriers that may hinder people from using foreign news media on a daily basis, and from a historical perspective, the open space of Internet-borne news is still a relatively new phenomenon. Thus, they can hardly be said to replace consumption of Swedish news. Rather, they add new, yet thin layers to the already existing media consumption. A more pertinent approach is therefore to look at the weekly rather than daily reach, not only for specific media types and platforms, but for transnational news consumption more broadly (See ). Both online newspapers and social media have a weekly reach of 13 percent. Moreover, 11 percent watch foreign news media on TV at least once a week, while 8 percent do it on digital platforms. Radio and especially printed newspapers, however, seem to be marginal also on a weekly basis.

FIGURE 1 Weekly reach of foreign news media on different platforms (per cent).

Note: The number of respondents that answered for each platform varied between 1462 and 1485

In order to gain a deeper knowledge about the use of foreign news media, one should not only focus attention on individual platforms but on the usage in a wider sense. An aggregation of the numbers for all platforms show that as much as 27 percent, more than a quarter of the Swedish population, consumes foreign news either through television, newspapers, radio, social media or other services on a weekly basis. This significantly higher reach indicates that the usage of different platforms do not always overlap, since media habits vary between generations and age groups. In the following, this will be discussed further, dissecting various factors that might impinge on the use of foreign news media.

Explaining High Consumption of Foreign News Media

How can we understand high consumers of journalism from other countries compared with those who seldom or never turn to this type of news? High consumers are defined here as those who consume foreign news media once a week or more often. Hence, this measure should not be confused with high consumption of domestic news, which is linked to historically established patterns of extensive daily and ritualized use (Arkhede and Ohlsson Citation2015; Ohlsson Citation2015).

In order to locate the results in a broader context, it can be helpful to briefly describe some of the defining characteristics of the high consumers as a group. They are for example more interested in politics (71 percent are very or quite interested) compared to the population as a whole (63 percent). The group is also more educated (41 percent) than the general population (31 percent), and it consists of people from all generations, although middle-aged and young people are over overrepresented. However, in order to illuminate the significance of these variables (as well as other factors) more precisely, it is better to use them as independent variables, and news consumption in the form of high and low/no consumption as the dependent variable. Are there any differences regarding factors such as age, education, geography and home country during childhood? And how does the consumption relate to political interest and consumption of Swedish journalism? below details these factors, including if and how strongly they correlate with high and low/non-usage of foreign news media.

TABLE 2 The significance of age, education level, geography, political interest, and news media habits for weekly transnational news consumption in Sweden (per cent)

The results show a significant moderate correlation between age and high consumption of foreign news media (Cramer’s V = .212). The share of high consumers is nearly 50 percent in the age span of 16–24, and more than twice as big as among those that have passed 50 (for whom the share varies between 19 and 23 percent). This should be seen in light of the flexible distinctly digital and social media habits of the younger generation, as well as the more stable, analogue and loyal media habits of the older (Ohlsson Citation2015). Education follows age in the sense that younger people are generally more educated (cf. SCB Citation2015), however its association with consumption of foreign news services is weaker (Cramer’s V = .148). While there are central differences related to age, there are few clear signs concerning the relationship between usage of Swedish and foreign news media. No significant results were found for either consumption of morning newspapers or evening tabloids. As illustrated in , however, the survey does show interesting indications regarding viewing of PSB television and printed newspaper subscribers. High consumers of foreign news media seem to be more common among those who never or seldom watch public service news, than among those who watch it more frequently (although, a Cramer’s V of .145 suggests a weak correlation). Similarly, there is a weak yet significant negative correlation between high consumers and printed newspaper subscribers (Phi = .154).

Potentially, a high degree of general news consumption could work as a gateway to other types of news. Conversely, dissatisfaction with Swedish news could lead to increased consumption of international alternatives. Yet as noted above, it is hard to draw any precise conclusions regarding this, given that the data points in different directions (see also the coming discussion on motives and attitudes).

The most striking results are related to social geography. Among people raised in Sweden, 23 percent are high consumers, while people with a background in other countries are far more inclined to use foreign news media. A Cramer’s V of .303 show a strong correlation, and it is reflected in the numbers for those who have grown up in the Nordic region (60 percent high consumers), and even more clearly for those who spent their childhood in other European countries (75 percent) and non-European countries (70 percent). However, it should be noted that migrants usually are underrepresented in national surveys, and that proficiency in Swedish was a prerequisite for participation. In addition, for people with nor or marginal knowledge in the Swedish language, there are few options (besides a multilingual service offered by Swedish radio) that deliver news with a primary focus on Sweden.

Sweden is a multicultural society, and migrants of different generations tend to gravitate towards major cities and larger towns. Stockholm, Gothenburg and Malmö, Sweden’s three big cities, are all blended social spaces where cultures, ideas and lifestyles are mixed. Large international businesses and creative industries are located there, as well as some of the big universities. Results from the survey show significant correlations (Cramer’s V = .161), and reflect differences mainly between big cities and towns on the one hand, and small towns and the countryside on the other. The high consumers constitute between 31 and 35 percent of the population in big cities and medium size towns, whereas people living in small towns and on the countryside seem to be less interested in news from other countries (15 and 20 percent respectively).

Last but not least, a noteworthy association concerns political interest. Political interest is often seen as a driving force behind news selection, and it has been argued that it plays an increasingly important role in the digital age (Strömbäck, Djerf-Pierre, and Shehata Citation2012). There is a significant and moderate correlation between political interest and high consumption of foreign news media (Cramer’s V = .224). The most important difference is between those who are very interested in politics (51 percent) and the rest (spanning people that are fairly interested to those not interested at all). However, the numbers do not increase consistently with age. Also among those who are totally disinterested in politics, there is a noteworthy share of transnational news consumers. This is probably linked to the fact that politics is just one of many areas of international significance in journalism. Technology, lifestyle, entertainment and sport are areas intimately intertwined with transnational and global processes, which may spark interest for journalism in other countries than Sweden.

Motives and Attitudes

There are of course many different reasons why people consume news. The following section sets the focus on motives and attitudes among the high consumers, e.g. people that use foreign news media at least once a week. The respondents could react to eight different statements, using a four-point Likert scale.

Three patterns crystallize in . First, it appears that foreign news media seem to interest high consumers on the basis of their capacity to providing alternative knowledge about the world. As many as 88 percent responded either “completely correct” or “fairly correct” to the statement that they use foreign news media because they “help me understand the outside world”. Nearly as many responded that journalism from other countries provide news with different perspectives (82 percent) compared to Swedish news. Thus, foreign news services fulfill orientation needs that Swedish media do not seem to satisfy. Second, it is clear that a considerable part, 23 percent, wants news in their mother tongue (15 and 8 percent, respectively, agree with that statement). An even larger share (37 percent) agrees with the statement that friends and relatives in other countries are motivations for their news use. These social or “connective” aspects of the news consumption are expressions of migration, but evidently also related to transnational social relations in a broader sense. It is also worth noticing that professional motives seem to be fairly marginal. In addition to orientational, professional and lingual needs, it may also be possible that some individuals choose foreign journalism due to dissatisfaction with the media in Sweden. That is at least not an unlikely connection, given that more than 80 percent of the high consumers confirm that they consume foreign news media to get acquainted with other topics and perspectives. However, only 35 percent of the respondents answered that they think that foreign news media hold a higher quality than Swedish news media (see ). Even fewer were those who answered that foreign news services are more trustworthy (23 percent). Although the responses to the two statements point in the same direction, quality seem to appear as a more versatile concept. Senses of objectivity and impartiality, but also selection of news topics, style, geographical outlook and language are aspects that may form the basis for a person’s evaluation of news quality. Trustworthiness, on the other hand, is more specifically related to ideals of truth-telling and impartial and objective news (Nygren and Widholm Citation2018; Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2017). That may explain the considerable difference (12 percentage points) between the responses to the two statements. No significant results were found as to potential differences between people with different backgrounds. Irrespectively of home country during childhood, high consumers do not see foreign news media as being more trustworthy. It should be noted, though, that the share of people born in other countries is significantly higher in the Swedish population than the share in the survey and the results should therefore be interpreted with prudence. Similarly, no significant results were found regarding differences pertaining to education or age. The attitude toward trustworthiness varied quite inconsistently. As to age, the share that held foreign news media as the better alternative varied between 10 and 21 percent. Together with the low figures for the daily consumption, these results can be taken as strong evidence for an enduring domination of national journalism institutions in most people’s news repertoire.

TABLE 3 Attitudes and motives towards foreign news media among weekly consumers (percent)

Concluding Discussion

This article has explored varieties of transnational news consumption in Sweden, and motives connected to foreign news services among weekly consumers. A considerable part of the Swedish population, 27 percent, consumes news produced in other countries on a weekly basis. The most common ways of getting transnational news are through social media and online newspapers followed by broadcast and online television news. Platform selections vary, primarily in different age groups, which explains the significantly larger aggregated reach for transnational news in general. Although there is no doubt that Swedish news media still is the most important source of information about current events on a daily basis, the figures can be taken as an indication of the transnational forces that are shaping the contemporary digital media culture. Two striking results of the survey is related to home country during childhood and age. People with a background in other countries than Sweden are significantly more prone to consume non-Swedish news media which goes in line with the results of previous studies (Vaage Citation2009; Wadbring Citation2001). As to age, the data analyzed reveals that young people are significantly more transnational in their news consumption habits compared with people of older generations. This gap also reflects a difference between those that get their news from traditional platforms, and those who turn to online and social media platforms. There is, for example, a negative correlation between consumption of PSB television news and consumption of foreign news media. A similar correlation was found concerning subscribers of morning newspapers. An important conclusion that can be drawn from these results is this that transnational news consumption goes far beyond the “elite” segments of society that so often are attributed do journalism in global and non-domestic settings (cf. Hafez Citation2007). There was for example only a weak correlation between education-level and transnational news consumption, and the difference in favor of the high-educated should first and foremost be seen as an effect pertaining to age. Political interest, which usually is a strong generative mechanism behind news consumption (Strömbäck, Djerf-Pierre, and Shehata Citation2012) proved to be significant also in a transnational context, but as noted in the analysis, a considerable share of those who are less interested in politics are also weekly transnational news consumers. This should above all be seen in light of the more open and blended news spaces that digital consumers encounter online, and especially on social media platforms.

Transnational mobility of content appear on multiple platforms (Athique Citation2016), but social media include a larger degree of incidental or “byproduct” media exposure (Yadamsuren and Erdelez Citation2010), since they are designed on the basis of social affinity and re-distribution of content within social networks rather than solely on active choices made by the users themselves. While this may weaken the position of traditional “catch all” legacy media institutions (Syvertsen et al. Citation2014), it may at the same time create a greater diversity with regard to geographical origin of the news that appear in media consumers’ news feeds.

Needles to say, strategies of domestication so often attributed to the practice of journalism (Nossek Citation2004) does not go away with potential transnational re-distribution. As Hafez notes, “the only thing universal or global about the world-view of different media systems is that they all suffer from the same problem: the domestication of the world” (Citation2007, 25). An important effect of the digital news environment is rather that it offers insights into the perspectives, viewpoints and news values of other outlets than those dominating in the media users’ local community or home country. As noted in the introduction, this is also a function that Swedish newspapers and public service broadcasters increasingly draw upon; when Sweden is mentioned in the international news flow, they often aim to contribute with a Swedish perspective to audiences outside their original target groups. Paradoxically, domestication constitutes the global selling point of such news, which can be seen as an indicator of why people want to take part of news from other countries. This relates to what Atad (Citation2017) has called “reversed domestication”, e.g. a transnational journalistic strategy that is sensitive to the newsworthiness of a clearly articulated connection between the country of origin of the news outlet and the events reported. The decoupling of audiences from space does inherit potential re-embedding effects. The article has addressed such effects by dissecting how media consumers perceive the quality and trustworthiness of the news as well as the different motives behind their consumption. Few high consumers—irrespectively of social factors such as age, education level or country during childhood—believe that other countries’ news are more trustworthy or of better quality than Swedish journalism. As to motives, however, a majority turn to other countries’ news in order to get insights into issues that Swedish news media do not cover. This article therefore concludes that transnational news consumption is not driven by dissatisfaction with Swedish news media, but rather on social curiosity regarding the world views of other countries’ news. In addition, transnational news consumption should first and foremost be understood in terms of an expansion rather than a replacement of the news repertoire (given that the daily consumption still is very low).

This study has not addressed geographical aspects of transnational news consumption. More research is needed as to how varied this consumption is with regard to media types and geographical origin as well as how it relates to zones of consumption such as lingual and cultural spheres (cf. Athique Citation2016). The centrality of online news and social media revealed in this study also raises important questions concerning the role of accidental news exposure. With no doubt, transnational news consumption will become increasingly important in the future, as new generations of (social) media users become active news consumers. Sweden is an interesting case for the study of transnational news given that the country has a comparatively high level of general news consumption combined with a well-developed digital infrastructure and an almost all-embracing Internet penetration and mobile media use among younger generations. These are probably central drivers behind transnational news consumption, but in future studies, their significance should also be addressed in comparative analyses between countries and regions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Many thanks to Ester Appelgren and Gunnar Nygren at Södertörn University for constructive comments on previous versions of this article.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. The truth about refugees in Sweden: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/global-opinions/wp/2017/02/24/the-truth-about-refugees-in-sweden/?utm_term=.4e7fa5a3b19d.

3. The tweet was formulated as follows: “My statement as to what’s happening in Sweden was in reference to a story that was broadcast on @FoxNews concerning immigrants & Sweden.” Tweet is available on Donald Trump’s Twitter account (accessed on December 12, 2017): https://twitter.com/realdonaldtrump/status/833435244451753984.

4. Quote from Sweden’s largest online newspaper Aftonbladet: https://www.aftonbladet.se/nyheter/a/g26Lk/after-trumps-last-night-in-sweden-here-are-the-errors-in-fox-news. Several of the English texts published during this period were among the most widely shared in social media in Sweden at the time. One of them published in Sweden’s largest daily, Dagens Nyheter, generated over 400,000 unique visitors alone in the same period.

5. Translation from Swedish by the author.

REFERENCES

- Aalberg, Toril, Arild Blekesaune, and Eiri Elvestad. 2013. “Media Choice and Informed Democracy: Toward Increasing News Consumption Gaps in Europe?” The International Journal of Press/Politics 18 (3): 281–303. doi: 10.1177/1940161213485990

- Anderson, Benedict. 1983. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

- Anderson, Chris. 2009. The Longer Long Tail: How Endless Choice is Creating Unlimited Demand. London: Random House Business.

- Ang, Ien. 1996. Living Room Wars: Rethinking Media Audiences for a Postmodern World. London: Routledge.

- Antunovic, Dunja, Patrick Parsons, and Tanner R Cooke. 2016. “‘Checking’ and Googling: Stages of News Consumption among Young Adults.” Journalism 1: 1–17.

- Appadurai, Arjun. 1996. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Appelgren, Ester. 2017. “The Reasons Behind Tracing Audience Behavior: A Matter of Paternalism and Transparency.” International Journal of Communication 11 (20): 2178–2197.

- Arkhede, Sofia, and Jonas Ohlsson. 2015. Nyhetsintresse och nyhetskonsumtion [News Interest and News Consumption]. SOM-rapport nr 2015:33. Göteborgs universitet: SOM-institutet.

- Atad, Erga. 2017. “Global Newsworthiness and Reversed Domestication: A new Theoretical Approach in the age of Transnational Journalism.” Journalism Practice 11 (6): 760–776. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2016.1194223

- Athique, Adrian. 2016. Transnational Audiences: Media Reception on a Global Scale. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Barnhurst, Kevin, and John Nerone. 2001. The Form of News: A History. New York: Guilford Press.

- Beck, Ulrich, and Elisabeth Beck-Gernsheim. 2002. Individualization: Institutionalized Individualism and its Social and Political Consequences. London: SAGE.

- Beck, Ulrich, and Daniel Levy. 2013. “Cosmopolitanized Nations: re-Imagining Collectivity in World Risk Society.” Theory, Culture & Society 30 (2): 3–31. doi: 10.1177/0263276412457223

- Berglez, Peter. 2013. Global Journalism: Theory and Practice. New York: Peter Lang.

- Bjur, Jakob. 2009. Transforming Audiences: Patterns of Individualization in Television Viewing. Gothenburg: Department of Journalism, Media and Communication, University of Gothenburg.

- Chalaby, Jean K. 2005. “Deconstructing the Transnational: A Typology of Cross-Border Television Channels in Europe.” New Media & Society 7 (2): 155–175. doi: 10.1177/1461444805050744

- Christiansen, Connie Carøe. 2004. “News Media Consumption among Immigrants in Europe the Relevance of Diaspora.” Ethnicities 4 (2): 185–207. doi: 10.1177/1468796804042603

- Dahlgren, Peter. 1995. Television and the Public Sphere: Citizenship, Democracy and the Media. London: Sage.

- Deuze, Mark. 2012. Media Life. Cambridge: Polity.

- Eurostat. 2016. “Internet Access and Use Statistics – Households and Individuals.” Accessed October 10, 2017. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Internet_access_and_use_statistics_-_households_and_individuals#Internet_use_by_individuals.

- Georgiou, Myria. 2006. Diaspora, Identity and the Media: Diasporic Transnationalism and Mediated Spatialities. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

- Giddens, Anthony. 1991a. The Consequences of Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Giddens, Anthony. 1991b. Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern age. Cambridge: Polity press.

- Hafez, Kai. 2007. The Myth of Media Globalization. Cambridge: Polity.

- Hallin, Daniel C., and Paolo Mancini. 2004. Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hartley, John. 1996. Popular Reality. London: Arnold.

- Heinrich, Ansgard. 2012. “Foreign Reporting in the Sphere of Network Journalism.” Journalism Practice 6 (5–6): 766–775. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2012.667280

- Hultén, Gunilla. 2016. “Den sårbara mångfalden [The Vulnerable Diversity].” In Människorna, medierna och marknaden. Medieutredningens forskningsantologi om demokrati i förändring, edited by Oscar Westlund, 329–250. Stockholm: Wolters Kluwers.

- IPSOS. 2015. “Affluent Europe 2015: Topline Media Results.” Accessed November 7, 2017. http://www.offremedia.com/media/deliacms/media/1357/135789-cf8b6f.pdf.

- Jervelycke Belfrage, Maria, and Annika Bergström. 2017. “Sociala medier: en nyhetsdistributör att räkna med [Social Media: A News Distributor to Count On].” In Larmar och gör sig till [Full of Sound and Fury], edited by Ulrika Andersson, Jonas Ohlsson, Henrik Oscarsson, and Maria Oskarson, 301–316. University of Gothenburg: SOM-institutet.

- Jung, Joo-Young. 2016. “Social Media, Global Communications, and the Arab Spring: Cross-Level and Cross-Media Story Flows.” In Mediated Identities and New Journalism in the Arab World: Mapping the “Arab Spring”, edited by Aziz Douai, and Mohamed Ben Moussa, 21–40. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Khvorostianov, Natalia, Elias Nelly, and Galit Nimrod. 2012. “‘Without it I am Nothing’: The Internet in the Lives of Older Immigrants.” New Media & Society 14 (4): 583–599. doi: 10.1177/1461444811421599

- Migrationsinfo. 2017. “Asylsökande i Sverige” [Asylum Seekers in Sweden]. Accessed November 2, 2017. http://www.migrationsinfo.se/migration/sverige/asylsokande-i-sverigeNielsen.

- Nielsen, Rasmus K. 2017. “News Media, Search Engines and Social Networking Sites as Varieties of Online Gatekeepers.” In Rethinking Journalism Again: Societal Role and Public Relevance in a Digital Age, edited by Peters Chris, and Broersma Marcel, 81–96. Abingdon Oxon: Routledge.

- Nordicom. 2017. Nordicom-Sveriges mediebarometer. Göteborg: Nordicom.

- Nossek, Hillel. 2004. “Our News and Their News: The Role of National Identity in the Coverage of Foreign News.” Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 5 (3): 343–368. doi: 10.1177/1464884904044941

- Nygren, Gunnar, and Andreas Widholm. 2018. “Changing Norms Concerning Verification: Towards a Relative Truth in Online News?” In Trust in Media and Journalism: Empirical Perspectives on Ethics, Norms, Impacts and Populism in Europe, edited by Kim Otto, and Andreas Köhler, 39–60. Wiesbaden: 0.

- Ohlsson, Jonas. 2015. “Nyhetskonsumtionens mekanismer [The Mechanisms of News Consumption].” In Fragment [Fragments], edited by Annika Bergström, Bengt Johansson, and Mari Oscarsson, 435–450. Göteborgs universitet: SOM-institutet.

- Rai, Mugdha, and Simon Cottle. 2007. “Global Mediations: On the Changing Ecology of Satellite Television News.” Global Media and Communication 3 (1): 51–78. doi: 10.1177/1742766507074359

- Reese, Stephen D. 2010. “Journalism and Globalization.” Sociology Compass 4 (6): 344–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2010.00282.x

- Robertson, Alexa. 2015. Global News: Reporting Conflict and Cosmopolitanism. New York: Peter Lang.

- SCB. 2015. “Utbildningsnivå för befolkningen efter inrikes/utrikes född, kön och åldersgrupp 2015 [Education Level in the Population in Relation to Country of Birth, Gender and Age Groups 2015].” Accessed November 2, 2017. http://www.scb.se/sv_/Hitta-statistik/Statistik-efter-amne/Utbildning-och-forskning/Befolkningens-utbildning/Befolkningens-utbildning/9568/9575/36661/.

- Schudson, Michael. 2003. The Sociology of News. New York: Norton.

- Seib, Phillip. 2010. “Transnational Journalism, Public Diplomacy, and Virtual States.” Journalism Studies 11 (5): 734–744. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2010.503023

- Singer, Jean B. 2014. “User-generated Visibility: Secondary Gatekeeping in a Shared Media Space.” New Media & Society 16 (1): 55–73. doi: 10.1177/1461444813477833

- Strömbäck, Jesper, Monica Djerf-Pierre, and Adam Shehata. 2012. “The Dynamics of Political Interest and News Media Consumption: A Longitudinal Perspective.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 24 (4): 414–435. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/eds018

- SVT. 2017. “Jimmie Åkesson (SD) skriver debattinlägg i Wall Street Journal.” Accessed October 31, 2017. http://www.svt.se/nyheter/utrikes/sd-svenska-judar-internflyktingar.

- Syvertsen, Trine, Gunn Enli, Ole J Mjøs, and Hallvard Moe. 2014. The Media Welfare State: Nordic Media in the Digital Era. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

- Thompson, John B. 1995. The Media and Modernity: A Social Theory of the Media. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Thurman, Neil. 2007. “The Globalization of Journalism Online: A Transatlantic Study of News Websites and Their International Readers.” Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 8 (3): 285–307. doi: 10.1177/1464884907076463

- Thurman, Neil. 2011. “Making ‘The Daily Me’: Technology, Economics and Habit in the Mainstream Assimilation of Personalized News.” Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 12 (4): 395–415. doi: 10.1177/1464884910388228

- Vaage, Odd F. 2009. Kultur-og mediebruk blant personer med innvandrerbakgrunn. Resultater fra Kultur-og mediebruksundersøkelsen 2008 og tilleggsutvalg blant innvandrere og norskfødte med innvandrerforeldre [Culture and Media Use Among People with Immigrant Background. Results from the Culture and Media Use Study]. Oslo and Kongsvinger: Statistik sentralbyrå.

- Wadbring, Ingela. 2001. Svenskars och invandrares medieinnehav och nyhetskonsumtion [Swedes’ and Immigrants’ Media Use and News Consumption]. Göteborg: Dagspresskollegiet/JMG, University of Gothenburg.

- Wadbring, Ingela. 2016. “Om dem som tar del av nyheter i lägre utsträckning än andra [On Those Who Take Part of News to a Less Extent Than Others].” In Människorna, medierna och marknaden. Medieutredningens forskningsantologi om demokrati i förändring [People, Media and the Market], edited by Oscar Westlund, 463–486. Stockholm: Wolters Kluwers.

- Wadbring, Ingela, Lennart Weibull, and Ulrika Facht. 2016. “Nyhetsvanor i ett förändrat medielandskap [News Habits in a Changing Media Landscape].” In Människorna, medierna och marknaden. Medieutredningens forskningsantologi om demokrati i förändring [People, Media and the Market], edited by Oscar Westlund, 431–462. Stockholm: Wolters Kluwers.

- Wahl-Jorgensen, Karin. 2017. “Is There a ‘Postmodern Turn’ in Journalism?” In Rethinking Journalism Again: Societal Role and Public Relevance in a Digital Age, edited by Peters Chris, and Broersma Marcel, 97–112. Abingdon Oxon: Routledge.

- Widholm, Andreas. 2011. Europe in Transition: Transnational Television News and European Identity. Stockholm: Stockholm University.

- Widholm, Andreas. 2016. “Global Online News from a Russian Viewpoint: RT and the Conflict in Ukraine.” In Media and the Ukraine Crisis: Hybrid Media Practices and Narratives of Conflict, edited by Mervi Pantti, 107–122. New York: Peter Lang.

- Yadamsuren, Borchuluun, and Sanda Erdelez. 2010. “Incidental Exposure to Online News.” American Society for Information Science and Technology 47 (1): 1–8.