ABSTRACT

It has been assumed that populism has become mainstream in the Western world, and that the media have substantially contributed to populism’s success and omnipresence in politics and society. To investigate populist elements in media coverage, extant research has mainly focused on election periods, or media populism in specific types of coverage and outlets. In this paper, we investigate if the use of populist elements in general media coverage has increased over time. Focusing on a 28-year period in the Netherlands, we find clear evidence for an increasing presence of people-centric, anti-elitist and right- and left-exclusionist coverage in newspapers. This trend is general, with only limited evidence for cross-outlet differences. Since our analysis was not limited to specific periods, sample frames or topics, our research offers first evidence for an unconditional increase of different elements of populist communication in traditional news coverage. An important implication is that the rise of populist news coverage has made populism more visible to the electorate, potentially setting the agenda for political parties and populist attitudes in public opinion.

Many scholars, journalists and politicians have argued that populism has been on the rise over the past decades. Populist discourse may color the ideas and communication of mainstream parties as well, a phenomenon that has been referred to as the “populist zeitgeist” (Mudde Citation2004). More recently, a growing number of scholars have extended the understanding of a populist zeitgeist by shifting their focus to the media as an important supply-side factor fueling the success of populist parties (e.g., Aalberg et al. Citation2017; Krämer Citation2014; Mazzoleni Citation2008). In its essence, populist communication entails the emphasis on the centrality of the ordinary or pure people. This virtuous in-group of the ordinary people is juxtaposed to the corrupt elites and/or dangerous others (e.g., Aalberg et al. Citation2017; Albertazzi and McDonnell Citation2008).

Research on the media’s role in populism can generally be divided into two approaches. First, one approach focuses on the role of the media in providing favorable opportunity structures for populist actors to speak to their electorate, also referred to as populism for or through the media (e.g., Bos and Brants Citation2014). In line with this, populist actors and ideas receive disproportional media attention because their focus on negativity, conflict, dramatization and common sense resonates well with the current media logic. The second conceptualization of the populism-media relationship assigns a more active role to the media, who may disseminate populist viewpoints themselves, referred to as populism by the media or media populism (e.g., Krämer Citation2014; Mazzoleni Citation2008).

Empirical evidence for this latter conceptualization of the media’s role in the spread of populist ideas is scarce (Bos and Brants Citation2014; Hameleers, Bos, and de Vreese Citation2017; Wettstein et al. Citation2018). The limited empirical support for a populist media bias may be explained when considering that populism is spread across the media in a fragmented way (Engesser et al. Citation2017)—which ties in with the “thinness” and incomplete nature of populism as a full-fledged ideology (Mudde Citation2004; Taggart Citation2000). Moreover, most previous content analyses have only zoomed in on a relatively short time period (for exceptions see e.g., Manucci and Weber Citation2017; Rooduijn Citation2014), therefore being unable to unravel trends in the dissemination of populist ideas by the media and to for example compare coverage in election years compared to routine periods. Although previous longitudinal content analyses by Manucci and Weber (Citation2017) and Rooduijn (Citation2014) have provided important insights into the development of populist communication over time—these approaches have focused on very specific periods of political communication: elections. Moreover, these studies did not analyze all types of coverage. Extending beyond existing research, this longitudinal content analysis investigates whether the presence of populist ideas in newspapers has increased over time, independent of specific developments in the political realm. Moreover, we look at the development of different indices of populism over the years, hereby incorporating recent findings that indicate that populism is spread in a fragmented way (Engesser et al. Citation2017).

Finally, although populism by the media may be overall a scarce phenomenon, segments of populist ideas may be more salient in some outlets in some periods (Hameleers, Bos, and de Vreese Citation2017). Against this backdrop, this paper investigates the presence of different indices of populism in different Dutch national newspapers over an extensive time period of 28 years. First and foremost, we are interested in investigating whether populism is indeed increasingly present in media coverage. Second, we investigate whether potential increases in populism are omnipresent, or more prevalent in certain newspapers.

In this paper, we define populist communication as a fragmented discourse that can rely on four elements: (1) people centrism (2) anti-elitism (3) right-wing exclusionism and (4) left-wing exclusionism (also see Jagers and Walgrave Citation2007). Although the first index may be regarded as a “thin” or “empty” indicator of populism, it does relate to the central and necessary interpretation of populist worldviews. Hence, in populist discourse, the pure, ordinary people and their will should be the focal point of politics. The other indices relate to the people’s enemy—the corrupt elites may for example deprive the people of their political and economic needs. In right-wing populism, this ideational core can be supplemented by the exclusion of societal out-groups, also defined as part of the host ideologies that can supplement populism’s thin core. In left-wing populism, these outgroups are likely to be defined in economic terms (i.e., the wealthy or the extreme-rich) (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2017).

To move forward within this research field, we analyzed the content of different broadsheet and popular newspapers for an extensive time period that included different election and routine periods. Extending previous longitudinal content analyses by Manucci and Weber (Citation2017) and Rooduijn (Citation2014), the findings of this paper allow us to explore whether there is indeed an overall increasing trend in the use of elements of populist discourse. Moreover, by investigating the differential use of different indices of populism in coverage in a range of outlets, we can establish whether potential increases are omnipresent, or limited to media with a certain signature or political leaning.

Conceptualizing Populist Communication

Although Mudde’s (Citation2004) conceptualization of populism as a thin-centered ideology revolving around the societal divide between the pure, ordinary people and the corrupt elites has been the dominant approach to defining populist political parties and ideas, more recent work into populist communication takes a more discursive approach to measuring populism (see Aslanidis Citation2016 for an overview). Among other things, populism has been understood as a political (communication) style (Moffitt Citation2016), a strategy (Barr Citation2009), a frame (e.g., Caiani and Della Porta Citation2011) or discourse (Laclau Citation2005). The commonality between these different approaches is that they all consider references to the centrality or monolithic will of the pure, ordinary people as the minimal requirement of populism. Most research further considers the people’s opposition to the corrupt, self-interested elites as a defining characteristic of populism. Populism may thus be Manichean, since it constructs a binary view on politics and society (Mudde Citation2004).

Still, consensus has not been reached on whether the potential exclusion of societal out-groups (i.e., immigrants in right-wing populism and wealthy segments of the population in left-wing populism) is a defining characteristic of populism. Within this debate, some scholars point to the potential conflation of nativism with populism (De Cleen and Stavrakakis Citation2017). A crucial distinction between exclusionism in populism opposed to nativism is reflected in the construction of the people. Specifically, nativism refers to the people’s identification with the nation, whereas populism refers to the people’s closeness to the in-group of pure, ordinary people.

In this paper, we approach populism as a communication phenomenon. In line with the empirical findings of Engesser et al. (Citation2017), we recognize the fragmented nature of the dissemination of populist ideas. Extending this argument, references to one single index may implicitly, or by extension, refer to or prime related components of populism. References to the centrality and failed representation of the ordinary people may for example imply that the political elites are failing to represent their citizens. Against this backdrop, we argue that, while related, the indices of populism can occur in different compositions and have different salience in media coverage and are thus worthwhile to consider separately. Specifically, we distinguish four indices of populist communication: people-centrism, anti-elitism, right-wing exclusionism and left-wing exclusionism.

People-centrism

The minimal defining characteristic of populist communication consists of references to the people (Aalberg et al. Citation2017; Jagers and Walgrave Citation2007). More specifically, populism regards the “pure” or “ordinary” people as a monolithic or homogenous in-group (e.g., Canovan Citation1999; Mudde Citation2004). The people belonging to this in-group are typically regarded as a “silenced majority” (Taggart Citation2000). This implies that the people’s voice should be reflected in political-decision making, but that the elites in power are currently not listening to the majority’s voice. In that sense, populism aims to give the power back to the ordinary people, who are able to decide on their own fate. By making the people the focal point of political-decision-making, populism aims to express the general will of the ordinary people (Mudde Citation2004).

Anti-elitism

The conceptualization of people centrism already implies that the people are opposed to an outsider that is obstructing their goals. This outsider can first of all be understood as the “corrupt” and self-interested elites (Mudde Citation2004; Taggart Citation2000). Hence, the ordinary people are seen in opposition to the corrupt elites that oppress them. The people are seen as being unresponsive to the needs of the ordinary people, and may be accused of prioritizing the needs of other groups in society (Elchardus and Spruyt Citation2016). The second index of anti-elitism is thus logically related to people-centrism: the elites are seen as corrupt and self-interested because they do not put their “own” people first. They prioritize their own needs instead of the people’s needs, which makes them incapable of representing the silenced majority of the people.

Although the two indices of people centrality and anti-elitism are integrated in the conceptualization of populism as a thin ideology (Mudde Citation2004; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2017), we will regard them as discursive elements of populism that may be spread in a more fragmented way (Aslanidis Citation2016; Engesser et al. Citation2017). Hence, our core aim is not to assess in detail how populism as an ideology is represented in media coverage, but rather how discursive indices of populism are spread across the media, and how their representation has developed over time.

Right-wing Exclusionism

Although extant research has not reached consensus on whether exclusionism can be regarded as a defining characteristic of populism, we do regard the exclusion of horizontal out-groups perceived as not belonging to the “pure” people as a potential indicator of right-wing populist discourse (also see Jagers and Walgrave Citation2007). Albertazzi and McDonnell (Citation2008), for example, regard the exclusion of “dangerous” others that deprive the sovereign people of their rights as a central component of populism. In Western Europe, these dangerous others are mainly defined on a religious or cultural basis. Many populist actors, such as Geert Wilders in the Netherlands or HC Strache in Austria, regard the Islam as the largest threat to the ordinary people. They are oftentimes connected to a rising threat to the safety of the ordinary people, for example as populist actors argue that immigrants with an Islamic backgrounds are more likely to be terrorists than “our” ordinary native people. Moreover, immigrants are regarded as a threat to the welfare of the ordinary people, as they profit unfairly from the scarce resources that should be invested in the ordinary people. To keep the ordinary people safe, and to protect their welfare, right-wing populism emphasizes that immigrants should be excluded from the ordinary people’s heartland.

Here, it is important to address the potential conflation of populism with nativism or nationalism (see De Cleen and Stavrakakis Citation2017 for an elaborate discussion). Populism cultivates an in-group of ordinary people, whereas nativism refers to the national in-group as the basis of identification and belonging. Populist discourse, in contrast, may deny belonging to the national identity, and rather stress the disconnect of the ordinary people to national identity. The ordinary people are seen as having lost their connection to the nation, as the corruption of the national elites, the European unification and the influx of migrants have gone too far—making the heartland an imaginary space that belongs to the past.

Left-wing Exclusionism

If we regard populism as a set of ideas that frame the virtuous and homogenous people against the “corrupt” elites and/or “dangerous” out-groups that are together accused of depriving the people (also see Albertazzi and McDonnell Citation2008), it is important to also consider “dangerous” others on a non-native level. More specifically, in the light of the rise of many left-wing populist movements and the salience of the European economic crisis as a favorable opportunity structure for populism (e.g., Aalberg et al. Citation2017), we regard left-wing exclusionism as an important element of populist communication (also see Hameleers et al. Citation2018). More specifically, populist ideas may also frame the deprived people in opposition to culpable others on a horizontal, economic level. These others can, for example, be defined as the “extreme” rich minority, CEOs of large corporations, or managers of banks. The exclusion of such out-groups from the ordinary people ties in with references to the “culture of greed” or “greedy minorities” and the gap between the extreme rich and extreme poor that is perceived as widening as a consequence of the profiting others.

The Varying Presence of Populist Communication

In studying the development of a populist zeitgeist over time, it is crucial to focus our empirical investigation of the prominence of the four populism indices over an extensive time period. Although extant research already acknowledged the potential role of time, this is mainly applied to the comparison of a shorter period, for example within routine or election coverage (Bos and Brants Citation2014; Rooduijn Citation2014).

Moving forward, this paper aims to assess the overall increase in the prominence of populism as a fragmented discourse in both routine and election periods. As argued by Rooduijn (Citation2014), the diffusion of populism in public opinion articles has become more prominent over the years. One explanation of this increase may be the rise of electorally successful populist parties over the last decades (e.g., Aalberg et al. Citation2017). More specifically, as political parties have gained more success in using populist discourse, the public may also be more receptive to these populist ideas. In order to respond to the increased appeal of populism among the public, news media may have increasingly relied on populist framing (e.g., Mazzoleni Citation2008). As a consequence, journalists may have relied more on common sense, people centrism and the circumvention of elites—which resonates with populist coverage.

A second, related, explanation may be an increasing commercial focus of the mass media over the last decades (Plasser and Ulram Citation2003). As the media’s pressure on appealing to larger audiences may have increased as a consequence of commercialization, references to the experience of the “common man” and the “ordinary” people may have become more central in journalistic reporting. A similar point is made by Hallin and Mancini (Citation2004): the media have become the mouthpiece of the ordinary people, and no longer represent the political elites. In this era, an increase in media populism can be expected (Krämer Citation2014). Specifically, media populism’s emphasis on the ordinary people and the circumvention of elites and out-groups that do not belong to the people should be more prominent in times of increasing commercialization and a media logic geared towards the popular tastes of the mass audience. Similar to Rooduijn’s (Citation2014) empirical conclusion, albeit tested in an electoral setting, we raise the first central hypothesis of this study.

Hypothesis 1 (H1): The prominence of the people centrality, anti-elitism and exclusionism index in media coverage have increased over time.

Yet, it needs to be stressed here that not all longitudinal studies have provided empirical support for an overall increase of populist discourse (see Manucci and Weber Citation2017). This may be explained by at least three reasons: (1) the focus on different countries may reveal different patterns; (2) the more favorable discursive opportunity structure for the expression of populism in election periods studied in extant research may reveal a stronger emphasis on populist rhetoric, irrespective of the year, therefore diluting the visibility of overall trends, and (3) previous studies have focused on a more restricted definition of populist discourse, not taking into account that the fragmented spread of different indices may have increased over time. For this reason, this study aims to move beyond existing approaches by including more time points that are not restricted to electoral events whilst exploring different indices of populism that relate to the fragmented spread of its thin ideological core.

Populist Communication in Popular and Broadsheet Outlets

On the one hand, the developments that underlie the first hypothesis are of a general, societal nature, and assume there might not be any substantial differences across different outlets. On the other hand, some newspapers might be more prone to populist tendencies than others. Especially popular or broadsheet newspapers are argued to provide a fertile ground for populist communication (e.g., Mazzoleni Citation2008) and might therefore show a steeper over-time increase in the presence of populist elements compared to broadsheet papers.

This alleged populist bias of popular outlets has been understood in the light of the different media logics and audiences of broadsheet versus popular outlets (e.g., Krämer Citation2014; Mazzoleni Citation2008). More specifically, popular outlets are assumed to focus more on the experience of ordinary people, whilst circumventing elites and experts (Mazzoleni Citation2008). Moreover, these outlets are assumed to rely more on common sense, dramatization, personalization and conflict coverage than broadsheet papers, which resonates with a preference for “common sense” and people centrism among the audience of popular newspapers. Broadsheet newspapers, in contrast, are expected to rely more on expert sources and technical, nuanced language. Taken together, the journalistic routines of popular newspapers may resonate stronger with a populist media logic than the coverage of broadsheet outlets (Krämer Citation2014). Despite these theoretical expectations, previous empirical research has failed to demonstrate a strong populist bias in popular outlets (e.g., Akkerman Citation2011), while empirical research into differential trends is largely absent. Yet, we know too little about the increased salience of populism in popular versus broadsheet newspapers.

We therefore pose the following research question:

(RQ1) Do popular and broadsheet newspapers differ in the changes in prominence of the people centrality, anti-elitism and (left- and right-wing) exclusionism index?

Methods

We rely on a computer-assisted, dictionary-based content analysis of the five largest national newspapers in the Netherlands (also see Rooduijn and Pauwels Citation2011). The Netherlands is generally considered a relevant case to study populism as it has witnessed a strong and early rise of populist (mainly right-wing) parties, such as the List Pim Fortuyn (LPF) in the early years of this century, and Geert Wilders’ Freedom Party (PVV). The Netherlands has been classified as a country with a corporatist media system (Hallin and Mancini Citation2004), with relatively high (yet decreasing) levels of newspaper readership and a strong protection of the journalistic freedom and independence. In the recent period, the Netherlands has witnessed strong tendencies of media commercialization (Brants and van Praag Citation2017).

We use the whole period of digital availability of each of them in the digital archive LexisNexis. NRC Handelsblad (1990–2017), de Volkskrant (1995–2017), Trouw (1992–2017), de Telegraaf (1998–2017) and Algemeen Dagblad (1992–2017). The latter two can be classified as popular newspapers, the first three as broadsheet ones. We constructed the dictionaries by the following approach.

First, based on existing literature, we composed a list of words and combinations of words that can be considered indicative for the various aspects of populism we identified. Similar to Rooduijn and Pauwels (Citation2011), we based our dictionary on empirical and theoretical concerns. Extending the dictionary of Rooduijn and Pauwels (Citation2011), we included indicators of (1) people centrism, (2) anti-elitism, and (3) right- and (4) left-wing exclusionism. As it may be difficult to find valid indicators of populism based on a single word (Rooduijn and Pauwels Citation2011), we also used specific combinations of words that, for example, indicate references to the “ordinary” people central in populist discourse (i.e., the hardworking tax-payer).

Second, based on these search strings, we collected material and went through the articles manually. We adjusted, extended and fine-tuned the search strings based on theoretical considerations (i.e., does the word offer an indicator of the fragmented ideology of populism?). We also checked for exclusivity (i.e., is the word likely to be an exclusive indicator of populism’s thin ideology?). For the final corpus for each indicator, we took a random sample of 100 articles and manually checked whether the article was indeed containing (a) the respective populist element and (b) whether it dealt with a domestic or international issue. Results were satisfactory, with relevance scores of 90% for people centrism, 96% for anti-elitism, 93% for right-wing exclusionism and 96% for left-wing exclusionism.

Overall, we had to strike a balance between precision (making sure that our results do not contain too many ‘false positives’) and recall (making sure we did not miss too many references to populism— “false negatives”). We for example excluded the foreign affairs sections of each newspaper, since our main interest lies in domestic politics. The final search strings can be found in the Appendix (in Dutch and English). Third, we collected all available articles for each of the four indices and counted for each of them, per outlet, the yearly number of articles that contained one or more of the (combination of) words included in the search strings. It is worth noting that the co-occurrence of the various indicators in individual newspaper articles is indeed limited, which is a clear indication of the fragmented nature of the presence of populism in media.Footnote1

We chose to rely on the absolute number of articles instead of shares of coverage because they are easier to interpret. We checked whether absolute volumes of newspapers in terms of number of articles differed systematically overtime, but this did not turn out to be the case. We also considered not using the number of articles, but the number of search terms (“hits”). The correlations between the resulting series and the one we use in this paper are very high (r = .88 for people centrism; r = .97 for anti-elitism; r = .98 for right-wing exclusionism and r = .97 for left-wing exclusionism) and results for analyses with this alternative operationalization are similar to the ones presented in the results section. The yearly aggregation level allows us to identify broader over-time trends. provides the descriptive statistics for each index and newspaper. We do not focus on absolute differences across outlets, since they might be a consequence of differences in overall sizes of newspapers, or of specific sections in newspapers.

Table 1. Mean scores and standard deviations of number of articles containing each of the populism indicators per newspaper per year.

To test our hypothesis and answer our research question, we conducted two types of analyses:

A regression analysis with dummy variables for newspapers that include a linear trend variable with a score of 0 for 1990, and adding one for each subsequent year. Standard errors are clustered in newspapers.

A regression analysis that includes interactions between newspaper dummy and the trend variable, to capture differential trends across outlets.

As literature suggests that media coverage during election times might be substantially different than during routine times (see e.g., Walgrave and Van Aelst Citation2006), we included as a control variable a dummy that captures whether a national parliamentary election took place during the year to which the observation relates. Since our data are strictly speaking count data, one could argue that a Poisson model is more appropriate than a linear regression model. We decided against this strategy for two reasons. First, our data shows large variation and closely mimics normal distributions. Second, count models limit the opportunity to test linear trends over-time, which are a central element of our investigation.

Results

Before looking into our hypothesis and research question, we look at the correlations in the presence of the various indices between newspapers. If these correlations are strong, this can be considered an indication of trends that go beyond a single newspaper and thus relating to broader societal developments, as is assumed by the notion of the Populist Zeitgeist. As shows, correlations across outlets are substantial, with averages between .73 (anti-elitism) and .85 (right-wing exclusion). These results show that Dutch newspapers indeed vary largely in tandem when it comes to the prominence of different aspects of populism.

Table 2. Correlations for presence of populism indicators per year across newspapers.

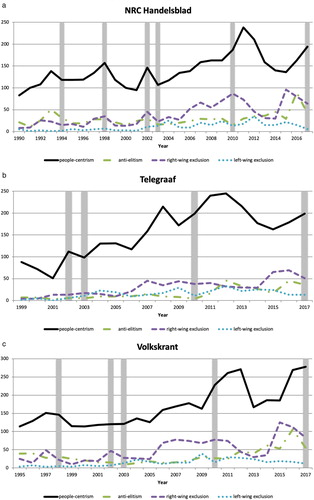

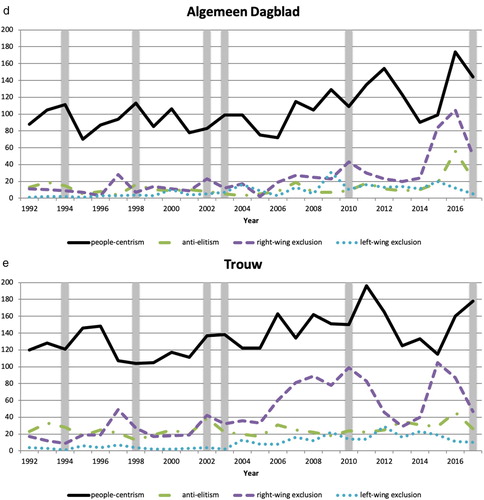

We now move to the first hypothesis: does the prominence of populist media coverage indeed increase over time? The results in provide an affirmative answer. We find that, controlled for absolute newspaper differences and election years, all aspects of populism become more prominent in media coverage. Especially the rise of people-centrism is substantial (on average an increase of more than 11 articles per newspaper per year). For the other indices, the increase is less big in substantial terms, ranging from just below 1 (anti-elitism and left-wing exclusion) to over 2.5 (right-wing exclusion), but in all instances the increase is highly significant (p < .001). Our analysis thus provides clear and unequivocal support for the first hypothesis. Additionally, differences between election and routine years are relatively limited: there are somewhat more articles containing references to people-centrism in election years, and a bit less left-wing exclusionism, but differences are relatively limited.

Table 3. Predicting the yearly number of articles containing each of the populism indicators in Dutch media coverage (main effects).

Is the trend similar across different newspapers? provides an answer. The interactions between newspaper dummies and the trend variable are most informative. Positive (and significant) coefficients indicate that for the respective newspaper, the overtime increase is larger than that of the reference category, in this case NRC Handelsblad. Overall, we see relatively little variation across newspapers, with two noteworthy exceptions: both in de Volkskrant and de Telegraaf people-centrism and anti-elitism have increased significantly more in those two newspapers compared to the NRC Handelsblad, and also the other newspapers. These findings indicate that, although references to the centrality of the people and anti-elitism have increased more in some newspapers than others, this difference cannot be ascribed to the difference between popular and broadsheet newspapers or ideological leanings. Both a right-wing popular newspaper (de Telegraaf) and a left-wing broadsheet outlet (de Volkskrant) have populism-ized more. When estimating an interaction model including a dummy variable for popular newspapers instead of dummies for individual newspapers, we find no significant interaction effects between time and newspaper types for any of the populism indicators. Contrary to expectations that only popular newspapers increasingly rely on populist indices over time, we find a less clear-cut tabloid bias of the rise of populism.

Table 4. Predicting yearly number of articles containing each of the populism indicators.

The reasons might be rather case-specific and might (partly) relate to the large decline in readership that those two newspapers have undergone and the strategic choices trying to revert these declining numbers. Overall, research question 1 needs to be answered by refuting the theoretical premise that there is a popular bias in the increase of populist indices in newspapers: while cross-newspaper differences exist, no structural differences in trends between popular and broadsheet newspapers can be identified.

For each of the newspapers, shows how the presence of the various populism indices indeed increases over time, and in comparable ways across newspapers.

Figure 1. (a–e) Trends in populist coverage in various newspapers. Note. Vertical bars indicate election years.

Conclusion and Discussion

This study set out to investigate whether the “populist zeitgeist”, as frequently discussed as a defining characteristic of many contemporary Western societies, finds its reflection in increasing presence of populist elements in general media coverage. Focusing on a 28-year period in the Netherlands, we indeed find clear evidence for an increasing presence of people-centric, anti-elitism and right- and left-exclusionism in newspapers. This trend is general, with only limited evidence for cross-outlet differences.

Our findings demonstrate that populist rhetoric is not as overtly dominant in media coverage as theoretically assumed (Mazzoleni Citation2008). Yet, the overall increase of populist coverage confirms the empirical findings of Rooduijn (Citation2014), who found an increase of populist rhetoric focusing specifically on election years and opinion articles. As an important next step, our results indicate that this increase is not simply driven by election coverage and opinion articles, but robust across different years, article types and topics. We do not find support for the theoretical premise that popular outlets are more likely to use populist elements in their coverage than broadsheets (Mazzoleni Citation2008). More specifically, we see an increase of people centrism and anti-elitism in the popular newspaper de Telegraaf and the left-wing broadsheet outlet de Volkskrant, which contradicts the theoretical premise of a strong and growing populist bias in popular outlets only. Our findings hereby support the conclusions of Akkerman (Citation2011) and Rooduijn (Citation2014), who did not find evidence for a strong relationship between popular outlets and populism. We do believe that the distinction between popular and broadsheet outlets made in this paper is transferable to other settings, although it may be argued that country-level differences in the ideological underpinnings and journalistic traditions and routines of newspapers may correspond to a different emphasis on populist elements in popular versus broadsheet outlets. Future comparative research may further assess the generalizability of the popular-broadsheet distinction.

Not all indices of populism are present at equal levels in newspaper coverage. Dutch newspapers thus represent discursive elements of populism in an uneven way. People centrism was the most salient indicator, followed by right-exclusionism. This result can be explained as people-centrism forms the common denominator of populism (e.g., Jagers and Walgrave Citation2007). This result corroborates the conceptualization of “empty” populism (also see Aalberg et al. Citation2017). In addition, following recent empirical evidence that points to the fragmented spread of populism in the press (e.g., Engesser et al. Citation2017), we believe that the relatively high levels of people-centrism correspond to the uneven dissemination of different components of populist ideas in mainstream media, indicating that people-centrism does not always co-occur with references to other populist ideas in single interpretations. In addition, the actual composition of the word list measuring people centrism moved beyond the mere presence of any reference to the people. More specifically, informed by theoretical and conceptual research on the thin ideology of populism (e.g., Mudde Citation2004) we actually included terms that indicated an inherently populist definition of the people (i.e., “ordinary Dutch citizens”).

The finding that elements of left-wing populism were relatively less salient than right-wing populist elements can be related to the electoral setting and discursive-level opportunity structures in the Netherlands (also see Aalberg et al. Citation2017). Hence, the presence of a successful and media-savvy right-wing populist actors in the Netherlands, Wilders, may also explain the relatively higher visibility of right-populist elements in the press. At the same time, the electoral success of a right-wing politician in the Netherlands can be connected to the pervasiveness of right-wing populist perceptions of the electorate. The Netherlands may thus provide a more fertile breeding ground for the cultivation of right-wing populist sentiments than left-wing populist ideas, which may be partially related to the salience of the immigration and refugee debate. We do not believe that the differences in the salience of populism indices are driven by a skewed distribution of the political orientations of the included newspapers: the sample of newspapers in the Netherlands was relatively balanced, and there are no identifications of parallelisms between the ideological leaning of newspapers and the presence of left- versus right-wing populist indices.

How can we then explain the overall increase in populist elements in different newspapers? One explanation may be the overall increase in support for populist parties in the period studied (also see Rooduijn Citation2014). In other words, since populist parties have become more successful over time, the overall support for populist issue positions has increased in public opinion. In order to respond to the increased appeal of populism in society, media outlets may have adopted the populist zeitgeist by adjusting their communication strategy to the audience they aim to appeal to. Second, and related, as the media have increasingly commercialized (e.g., Hallin and Mancini Citation2004), they should have become more responsive to the demands of the mass audience. In other words, as the audience has become more susceptible to populist viewpoints, newspapers should follow suit by responding to the dominant tastes of their audience.

Alternatively, it may be argued that the influences between the media, politics and society flow in multiple directions at the same time. We may thus identify different patterns of agenda-setting and agenda-building (Van Aelst and Walgrave Citation2016). Although it has been demonstrated that the political realm is more likely to follow the media agenda than the other way around (e.g., Soroka Citation2002; Vliegenthart et al. Citation2016), an alternative explanation is that the media are following politics when zooming in on specific events (Bennett Citation1990). As political populism may be fairly issue-specific (i.e., right-wing populist actors are assumed to “own” the issue of immigration), it might well be that changing media content is a direct consequence of the increased presence of certain (relatively new) political parties in for example the parliamentary realm, or, even more broadly, of changing political discourse by established parties. In that sense, this reversed pattern of agenda building may also serve as an explanation for the trend of an increased populist zeitgeist.

Irrespective of the causal direction of influence, the media may be regarded as an important factor in public opinion formation, and the increased references to the centrality of the people, distance to elites and the exclusion of out-groups may have important political consequences. More specifically, the cultivation of a deprived in-group of “the people” and the attribution of blame to various scapegoats may persuade and mobilize the public, as demonstrated by social identity framing research (e.g., Gamson Citation1992; Polletta and Jasper Citation2001). Indeed, experimental research shows that populist media coverage can increase people’s intention to vote for populist parties (Hameleers et al. Citation2018). Over the years, the audience has been exposed to more populist viewpoints through the media, which may prime and activate likeminded interpretations of societal reality—eventually boosting support for populist parties.

Our study has some limitations. First, we may not be able to establish a clear causal relationship between the increasing trend of populist references in media coverage and increasing support for populist ideas and parties in public opinion. Future research that explicitly links populist media coverage to panel survey data collected over an extensive period may reveal such causal patterns in a more valid and reliable way. Moreover, we focused on the “fragmented” dissemination of populist elements, which deviates from the dominant thin-ideological approach (e.g., Mudde Citation2004). Yet, in line with recent empirical evidence, we believe that the different elements of populist communication do not always co-occur in single interpretations or articles, but that the spread of populist ideas follows a more fragmented flow of communication (Engesser et al. Citation2017).

Another limitation concerns the potential validity issues related to our dictionary-based automated content analysis. Although our manual validity checks confirm that the indices of populism can accurately be measured using a dictionary approach (also see Rooduijn and Pauwels Citation2011)—it could be argued that the rich nature of populist discourse cannot be comprehensively measured by relying on an automated content analysis. Hence, populism may describe complex interrelationships between references to the people and anti-elitist sentiments. Although we do suggest future research to empirically explore the co-occurrence and patterns of different indices in more detail, we do believe that our method is able to measure the fragmented nature of populism in news media (e.g., Engesser et al. Citation2017). More specifically, as manual content analyses have indicated that the thin populist ideology is typically present in the form of separate elements in a news media text, our dictionary approach is able to capture the actual nature of populist ideas in political communication.

Finally, our single country design begs the question to what extent results are also found in different contexts. Given that many West-European countries have faced similar societal and political developments as the Netherlands, we have good reason to believe the results are generalizable, but whether that is actually the case remains an open empirical question. Future research may investigate how different elements co-occur in patterns of news coverage, for example based on a typology of different forms of populist communication (Jagers and Walgrave Citation2007). Finally, although we have sampled an extensive time period covering a variety of (electoral) events, we recommend future research to rely on a comparative research design to see how the trend of an intensified populist zeitgeist in the media holds across different settings that (Aalberg et al. Citation2017).

Despite these limitations, our study has provided important evidence for an overall, outlet-independent increase of a populist media bias in newspapers, which may have important ramifications for trends in public opinion and voting. As voters rely on the media as an information source guiding their electoral decisions, media coverage that offers an increasingly prominent place to “the people” whilst scapegoating the “corrupt” elites may contribute to the electoral success of populist parties.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 People centrism and anti-elitism co-occur in 117 articles (.69% of all articles containing people centrism, 4.14% of anti-elitism); for people centrism and right-wing exclusionism this number is 190 (1.12% and 4.13% respectively); people centrism and left-wing exclusionism 83 (.49% and 5.89%); anti-elitism and right-wing exclusionism 47 (1.66% and 1.02%); anti-elitism and left-wing exclusionism 25 (.89% and 1.77%); right- and left-wing exclusionism 11 (.24% and .78%).

References

- Aalberg, T., F. Esser, C. Reinemann, J. Strömbäck, and C. H. de Vreese, eds. 2017. Populist Political Communication in Europe. London: Routledge.

- Akkerman, T. 2011. “Friend or Foe? Right-wing Populism and the Popular Press in Britain and the Netherlands.” Journalism 12 (8): 931–945. doi: 10.1177/1464884911415972

- Albertazzi, D., and D. McDonnell. 2008. Twenty-first Century Populism. The Spectre of Western European Democracy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Aslanidis, P. 2016. “Is Populism an Ideology? A Refutation and a new Perspective.” Political Studies 64 (1): 88–104. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12224

- Barr, R. R. 2009. “Populists, Outsiders and Anti-establishment Politics.” Party Politics 15 (1): 29–48. doi: 10.1177/1354068808097890

- Bennett, W. L. 1990. “Toward a Theory of Press-state Relations in the United States.” Journal of Communication 40 (2): 103–127. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1990.tb02265.x.

- Bos, L., and K. Brants. 2014. “Populist Rhetoric in Politics and Media: A Longitudinal Study of the Netherlands.” European Journal of Communication 29 (6): 703–719. doi: 10.1177/0267323114545709

- Brants, K., and P. van Praag. 2017. “Beyond Media Logic.” Journalism Studies 18 (4): 395–408. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2015.1065200

- Caiani, M., and D. Della Porta. 2011. “The Elitist Populism of the Extreme Right: A Frame Analysis of Extreme Right-wing Discourses in Italy and Germany.” Acta Politica 46 (2): 180–202. doi: 10.1057/ap.2010.28

- Canovan, M. 1999. “Trust the People! Populism and the Two Faces of Democracy.” Political Studies 47: 2–16. doi:10.1111/1467-9248.00184.

- De Cleen, B., and Y. Stavrakakis. 2017. “Distinctions and Articulations: A Discourse Theoretical Framework for the Study of Populism and Nationalism.” Javnost – the Public 24 (4): 301–319. doi: 10.1080/13183222.2017.1330083

- Elchardus, M., and B. Spruyt. 2016. “Populism, Persistent Republicanism and Declinism: An Empirical Analysis of Populism as a Thin Ideology.” Government and Opposition 51 (1): 111–133. doi:10.1017/gov.2014.27.

- Engesser, S., N. Ernst, F. Esser, and F. Büchel. 2017. “Populism and Social Media: How Politicians Spread a Fragmented Ideology.” Information, Communication & Society 20 (8): 1109–1126. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2016.1207697.

- Gamson, W. A. 1992. Talking Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hallin, D. C., and P. Mancini. 2004. Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hameleers, M., L. Bos, and C. H. de Vreese. 2017. “They did it: The Effects of Emotionalized Blame Attribution in Populist Communication.” Communication Research 44 (6): 870–900. doi:10.1177/0093650216644026.

- Hameleers, M., L. Bos, N. Fawzi, C. Reinemann, I. Andreadis, and N. Weiss. 2018. “Start Spreading the News: A Comparative Experiment on the Effects of Populist Communication on Political Participation in 16 European Countries.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 23: 517–538. doi: 10.1177/1940161218786786

- Jagers, J., and S. Walgrave. 2007. “Populism as Political Communication Style: An Empirical Study of Political Parties’ Discourse in Belgium.” European Journal of Political Research 46 (3): 319–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00690.x

- Krämer, B. 2014. “Media Populism: A Conceptual Clarification and Some Theses on its Effects.” Communication Theory 24: 42–60. doi: 10.1111/comt.12029

- Laclau, E. 2005. On Populist Reason. London: Verso.

- Manucci, L., and E. Weber. 2017. “Why The Big Picture Matters: Political and Media Populism in Western Europe Since the 1970s.” Swiss Political Science Review 23 (4): 313–334. doi: 10.1111/spsr.12267

- Mazzoleni, G. 2008. “Populism and the Media.” Chap. 3 in Twenty-First Century Populism: The Spectre of Western European Democracy, edited by D. Albertazzi and D. McDonnell, 49–64. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

- Moffitt, B. 2016. The Global Rise of Populism: Performance, Political Style, and Representation. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Mudde, C. 2004. “The Populist Zeitgeist.” Government and Opposition 39 (4): 541–563. doi:10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x.

- Mudde, C., and C. Rovira Kaltwasser. 2017. Populism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Plasser, F., and P. A. Ulram. 2003. “Striking a Responsive Chord: Mass Media and Right-wing Populism in Austria.” Chap. 2 in The Media and Neo-populism, edited by G. Mazzoleni, J. Stewart, and B. Horsfield, 21–44. London: Praeger.

- Polletta, F., and J. M. Jasper. 2001. “Collective Identity and Social Movements.” Annual Review of Sociology 27 (1): 283–305. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.283

- Rooduijn, M. 2014. “The Mesmerising Message: The Diffusion of Populism in Public Debates in Western European Media.” Political Studies 62 (4): 726–744. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12074

- Rooduijn, M., and T. Pauwels. 2011. “Measuring Populism: Comparing Two Methods of Content Analysis.” West European Politics 34 (6): 1272–1283. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2011.616665

- Soroka, S. N. 2002. “Issue Attributes and Agenda-setting by Media, the Public, and Policymakers in Canada.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 14 (3): 264–285. doi:10.1093/ijpor/14.3.264.

- Taggart, P. 2000. Populism. Buckingham & Philadelphia: Open University Press.

- Van Aelst, P., and S. Walgrave. 2016. “Information and Arena: The Dual Function of the News Media for Political Elites.” Journal of Communication 66 (3): 496–518. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12229

- Vliegenthart, R., S. Walgrave, F. R. Baumgartner, S. Bevan, C. Breunig, S. Brouard, and L. C. Bonafont, et al. 2016. “Do the Media Set the Parliamentary Agenda? A Comparative Study in Seven Countries.” European Journal of Political Research 55 (2): 283–301. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12134

- Walgrave, S., and P. Van Aelst. 2006. “The Contingency of the Mass Media’s Political Agenda-setting Power: Toward a Preliminary Theory.” Journal of Communication 56 (1): 88–109. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00005.x.

- Wettstein, M., F. Esser, A. Schulz, D. S. Wirz, and W. Wirth. 2018. “News Media as Gatekeepers, Critics, and Initiators of Populist Communication: How Journalists in ten Countries Deal with the Populist Challenge.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 23 (4): 476–495. doi:10.1177/1940161218785979.

Appendix

Search terms (originally in Dutch, translated into English)

People-centrism

(((de gewone Nederlander! OR gewone Nederlanders OR de hardwerkende burger! OR hardwerkende burgers OR de gewone burger! OR gewone burgers OR de normale Nederlander! OR de normale burger! OR hardwerkende Nederlander! OR de hardwerkende belastingbetaler! OR ons eigen volk OR het gewone volk OR ons eigen land OR onze eigen cultuur OR de gewone man OR de gewone vrouw OR (Henk en Ingrid) OR (Jan met de Pet) OR de modale man OR Jan Modaal) AND NOT SECTION(buitenland))

(((The ordinary Dutch citizen! OR ordinary Dutch people OR hard-working citizen! OR hardworking citizens OR the ordinary citizen! OR ordinary citizens OR the normal Dutch people! Or the normal citizen! OR hard-working Dutch citizen! OR hard-working taxpayer! OR our own people OR the ordinary people OR our own country OR our own culture OR the ordinary man OR the ordinary woman OR (Henk and Ingrid) OR (Jan with the hat) OR the modal man or Jan Modal) AND NOT SECTION (foreign affairs))

Anti-elitism

((((regering OR elite OR politici OR politiek) w/2 (corrupt! OR zelfingenomen! OR leugenachtig! OR laf! OR zelfzuchtig! OR zelfverrijkend! OR graaiend!)) OR Eurofielen OR Nexit OR corrupte EU OR bureaucratische EU OR neppolitici OR nepkabinet AND NOT SECTION(buitenland) AND NOT (“Fraude en corruptie” w/2 “politiek”))

((((government OR elite OR politician! OR politics) w/2 (corrupt! OR self-interested OR lying OR coward! OR arrogant! OR self-serving! OR greed!)) OR Europhiles OR Nexit OR corrupt! EU OR bureaucratic EU OR fake politician! OR fake cabinet AND NOT SECTION (foreign affairs) AND NOT (“Fraud and corruption” w/2 “politics”))

Right-wing Exclusion

((islamiser! OR de-islamiser! OR grenzen dicht OR gelukzoeker! OR asielprofiteurs! OR (profite! w/2 (immigrant! OR asielzoeker! OR vluchteling)) AND NOT SECTION(buitenland))

((Islamize! OR de-islamize! OR close borders OR furtune seeker! OR asylum profiteer OR (profiteer! w/2 (immigrant! OR asylum seeker! OR refugee!)) AND NOT SECTION (foreign affairs)

Left-wing Exclusion

((extreem-rijken OR (extre! w/2 rijk!) OR (rijk! w/2 1%) OR graaicultuur OR ((graai! OR zelfverrijke! OR zelf-verrijk! OR corrupt!) w/5 (manager! OR bankier!)) OR (zelfzuchtig! w/2 rijk!) AND NOT SECTION(buitenland))

((the extreme-rich OR (extre! w/2 rich!) OR (rich! w/2 1%) OR culture of greed OR (greed! OR self-serving! OR self-serf! OR corrupt!) w/5 (manager! OR banker!)) OR (selfish! w/2 rich!) AND NOT SECTION (foreign affairs)