ABSTRACT

Based on a longitudinal research design (2006–2017), this article analyses how Guardian journalists engage in “below the line” comment spaces; what factors shape this engagement; and how this has evolved over time. The article combines a large-scale quantitative analysis of the total number of comments made (n = 110,263,661) and a manual content analysis of all comments made by 26 journalists (n = 5448) and their broader writing practices with 18 semi-structured interviews conducted in two phases (13 in 2012 and 5 repeated in 2017–18). The results show that there is considerable interest in comment spaces amongst readers, with exponential growth in user commenting. Furthermore, there has been significant engagement below the line by some Guardian journalists, and this is often in the form of direct and sustained reciprocity. Journalist commenting has waned in recent years due to difficulties coping with the volume of comments; changes in editorial emphasis; concerns over incivility and abuse; and a decrease in perceived journalistic benefits of commenting, alongside the rise in importance of Twitter. When journalists comment, they do so in a variety of ways and their comments are often substantive, significantly adding to the story by, for example, defending and explaining their journalism practice.

Introduction

“Below the line” (BTL) comment spaces have grown to be one of the most popular and widely engaged with forms of user-generated content on news websites. Comment spaces provide a space for public debate in which journalists can hear from, and directly engage with, their audience (Manosevitch and Walker Citation2009, 681; Lewis, Holton, and Coddington Citation2014; Graham and Wright Citation2015). It was thought that this might amount to a “dramatic conceptual and practical shift for journalists” (Singer et al. Citation2011, 277) that facilitated dialogical (Deuze Citation2003), participatory (Domingo et al. Citation2008) or reciprocal journalism (Lewis, Holton, and Coddington Citation2014) in which journalists engaged with their audience and perhaps even produce news in a more collaborative manner. It was hoped that comments might both improve the practice of journalism, and provide an economic benefit by encouraging a more engaged audience. While there was initially much hope for journalist-audience interaction (Borger et al. Citation2013), a number of issues have been identified that impede this, including incivility, abuse, comment overload, and journalistic norms and cultures. Several companies have either rolled back or dropped comment spaces (Finley Citation2015).

The Guardian has been a pioneer in comment spaces through its Open Journalism project, and its comment spaces have proved quantitatively successful, making it an important and interesting case (Rusbridger Citation2012). The tone of comments at the Guardian has been found to be broadly deliberative, and journalists have expressed a commitment to engaging in comment spaces (Graham and Wright Citation2015). However, the quantitative success of their comments has created a quandary for the Guardian that amounts to a:

tension between the editorial and commercial motives: if comments are to have editorial value, journalists need to be able to find the useful comments and enter into genuine dialogue with readers; but if they are to have commercial value, comments need to be high in volume, making this almost impossible. (Gardiner Citation2018, 604)

Theorising Journalist-Audience Interaction

There was initial hope that the internet would lead to a new form of interactivity between journalists and their audience (Pavlik Citation2001), and this is something that journalists often aspired to themselves (Deuze, Neuberger, and Paulussen Citation2004), though there were differences of opinion within newsrooms between innovators or convergers and more cautious traditionalists (Robinson Citation2010). Domingo (Citation2008) argued that interactivity was a myth that exists in the minds of journalists, but did not happen in practice because it clashes with journalistic norms. However, in making this argument, Domingo was not claiming that interactivity is not occurring – he finds that journalists were often reading the comments and sometimes “engaged in small conversations in the comments area, answering the most direct proposals” (Domingo Citation2008, 694). Rather, he argues that this interactivity fails to meet the hype. This approach is problematic because it may undervalue the significance of incremental change; it is possible to interpret Domingo's findings as evidence of interaction rather than as a myth (Wright Citation2012).

In recent years, renewed attention has been placed on the idea of journalist-audience interaction, particularly as there has been a push towards subscription-based business models. Significant investment has been placed into the idea of building community and engaged journalism (see e.g., https://engagedjournalism.com/). Focus is often placed on local or hyperlocal news. However, as Robinson (Citation2014) argues, in a digital world physical proximity is exploded, and comment spaces may constitute a form of “third space” (Wright Citation2012) in which it may make sense to think of readers as citizens rather than a geographic place, and connectivity rather than physical meetings (Reader Citation2012; Robinson Citation2014), what may be a form of geo-social journalism (Hess and Waller Citation2014). For Robinson (Citation2014), journalists “must complete that communicative loop” with audiences in comment spaces “to ensure the connection has been maintained and that it is re-affiliated continuously” and this is likely to influence audience participation (Meyer and Carey Citation2014).

Lewis, Holton, and Coddington’s (Citation2014) concept of reciprocal journalism has been particularly influential. They identify three forms of reciprocal journalism. First, there is direct reciprocity, which refers to “more frequent and purposeful forms of direct exchange” that can “encourage others in the community to more actively reciprocate” because of its one-to-one structure (233–234). Second, there is indirect reciprocity, in which “the beneficiary of an act returns the favour not to the giver, but to another member of the social network” and is one-to-many in structure (234). Finally, sustained reciprocity “encompasses both direct and indirect reciprocity, but does so by extending them across temporal dimensions” (235) and may generate longer-term relationships.

While the concept of reciprocal journalism is of value for encouraging us to pay attention to patterns of interaction between journalists and audiences, it does not really address the content of their comments. Lewis, Holton, and Coddington’s (Citation2014) approach assumes that sustained engagement builds community, but it seems likely that this is dependent not just on the fact of engagement but the content too. As they note, reciprocity is “broadly defined as [an] exchange between two or more actors for mutual benefit” and to assess benefit implies a deeper analysis than whether or not there is a reply/sustained engagement (Lewis, Holton, and Coddington Citation2014, 231). For example, if a journalist was to reply accusing the reader of being an idiot, it might be harmful to the relationship and brand more broadly.

Thus this article assesses whether journalists were engaged in direct, indirect and sustained reciprocity, but extends this theory by looking in detail at the content and function of their comments. Moreover, it does so not in the context of local journalism but in a large, global comment space. Before the method is presented, some of the key challenges that may impede journalist-audience interaction are presented.

The Practice of Journalist Engagement in Comment Spaces

Empirical studies of whether and how journalists engage in comment spaces suggest mixed results. Studies have found that journalists and editors are reluctant to engage in comment spaces (Jönsson and Örnebring Citation2011; Singer et al. Citation2011; Martin Citation2015) even though they consider it normatively desirable (Domingo et al. Citation2008; Ihlebæk and Krumsvik Citation2015). A study of US news blogs found that 80% of journalists never replied at all, and those that did barely replied (Dailey, Demo, and Spillman Citation2008). Nielsen (Citation2014, 470) concludes that: “journalistic norms and conceptions of expertise prevent journalists from engaging with readers”, while others have linked it to the perception that comments are offensive, untrustworthy, and unrepresentative (e.g., Viscovi and Gustafsson Citation2013; Bergström and Wadbring Citation2015). However, Santana (Citation2010) reports that 69% of journalists often or sometimes read online comments, while Nielsen (Citation2014) states that 35.8% of journalists read them frequently or always, and Garden’s (Citation2016, 338–339) analysis of political news blogs on Australian mainstream media found that journalists made up to 18% of all comments – what might amount to a hybrid approach to engagement that speaks to an “ethic of participation” (Lewis Citation2012, 851). Larsson’s (Citation2017) study of Swedish newspaper activity on Facebook found that journalists were commenting, but there were variations across different institutions, with an overall decline in journalist engagement over time. Graham and Wright’s (Citation2015) analysis of the Guardian's comment spaces found limited journalist comments in their sample, though most journalists reported engaging below the line in interviews and it was positively impacting their journalism practice. The different findings might be explained by changes in practice over time, but there is a lack of longitudinal studies.

Research has identified a series of challenges that can impede journalist engagement in comment spaces (Ziegele et al. Citation2017). Arguably the biggest challenge is that comments can be uncivil (Erjavec and Kovačič Citation2012; Coe, Kenski, and Rains Citation2014) and abusive (Binns Citation2012) and this can generate negative emotions for journalists (Chen et al. Citation2018). Gardiner’s (Citation2018) analysis of the Guardian found that stories by female and ethnic minority journalists’ have systematically more blocked messages (2.16%) than male journalists (1.62%). In total, 1.4 million of 70 million comments were blocked by moderators. It should be noted that blocked comments were a proxy for “abusive or dismissive” comments, and thus we cannot be sure whether the messages actually were abusive. It also assumes that moderation rules were applied effectively (Gardiner Citation2018, 595–596). Her survey of Guardian journalists found that 80% had experienced comments “that went beyond acceptable criticism of their work to become abusive” (suggesting 20% had not). The results were similar for male and female journalists – with ridicule the most common form of abuse (84%), and the abuse of female journalists was more personal. Journalists reported that this abuse had made them angry (8%), depressed (43%) and led to symptoms of anxiety (37%). Abuse led 53% of Guardian journalists to stop reading comments, 33% to stop engaging in debates, and 14% said they had seriously considered quitting journalism with female journalists more likely to change their behaviour.

While this suggests a deeply negative picture, some studies find comment debates to be of a reasonably high deliberative quality. Ruiz et al.’s (Citation2011) cross-national comparison found that there were variations across national contexts with the Guardian and the New York Times closest to Habermasian ideals, while Freelon’s (Citation2015) cross-platform analysis found that comment spaces exhibited some deliberative norms, and Graham and Wright (Citation2015) found that Guardian comments were broadly deliberative. Sindorf’s (Citation2013) analysis of local and national newspaper comments found that local comment sections were more respectful and contained some moments of deliberation – a finding broadly supported by Strandberg and Berg (Citation2013) and Manosevitch and Walker (Citation2009). These studies suggest that the nature of the debate is linked to the topic, with structural features such as moderation impacting debate (Ruiz et al. Citation2011).

A second concern is that commenters are atypical: most users read rather than comment (Larsson Citation2011, 1192; Barnes Citation2014); a small group of “super-posters” dominate (Graham and Wright Citation2014); there is a strong male gender bias (Martin Citation2015); and there are attempts to strategically manipulate online debate (Elliott Citation2014).Footnote1 Given these issues, it raises the question: should journalists engage BTL, especially if it impacts their journalism practice (Graham and Wright Citation2015)?

In summary, while there is a significant amount of literature assessing comments spaces, two important gaps have been identified. First, there has been no systematic analysis of how journalists actually comment, such as how often they comment, what they say and do when commenting, and whether they engage in reciprocal communication. Second, there have been limited studies that have systematically analysed how below the line comments have changed over time, and how, in turn, this is related to journalists’ engagement. Understanding how journalists participate is important for two principal reasons. First, as noted above, it directly addresses one of the key theoretical debates about the impact of the internet on journalism – namely the potential for participatory, dialogic, or reciprocal journalism. Second, it allows us to assess one of the key claims about comment spaces: that they might enhance interaction between journalists and their audience, and this might facilitate critical reflection and improve journalism practice. Given these important gaps, this study addresses three research questions (RQs):

RQ1: How has the volume of commenting BTL by users and journalists changed (2006–17)?

RQ2: How and why has commenting by journalists evolved at The Guardian?

RQ3: What is the nature and function of journalist comments?

Research Design and Method

To answer the research questions a longitudinal and multi-method research design was adopted, combining a large-scale quantitative analysis of the estimated total number of comments made on the Guardian each year from 2006 to 2017 (n = 110,263,661); a manual content analysis of all of the comments made by 26 Guardian journalists from 2006 to 2017 (n = 5448); an analysis of the number of articles written by the journalists for the Guardian and whether they were opened to comments; and a total of 18 semi-structured interviews conducted in two phases (2012 and again in 2017–18).

To analyse the total number of comments each year, this article uses the date-stamped permalink of each comment. These are numbered sequentially. For example, the first comment (deleted by a moderator) was posted in March 2006 (http://discussion.theguardian.com/comment-permalink/1) and the last (http://discussion.theguardian.com/comment-permalink/110263661) comment of 2017 is number 110,263,661. The first and last comment of each year was manually identified. It was not possible or ethical to scrape all of the comments. To enhance validity, a date-ordered stratified random sample of 1000 URLs was asssessed over the entire range to see if there were any errors. All comments from 2011 to 2017 were in sequential date order, but some issues were identified with the sequential ordering between 2006 and 2010, so the year-by-year analysis of all comments begins in 2011.Footnote2 The total number of comments does not appear to be affected. Nevertheless, the data is treated as an estimate as there may be gaps or errors that were not visible. The analysis of journalist comments focused on the individual journalist's public comment profile – a page that lists all of their comments and replies (https://profile.theguardian.com/user/id/XX). All comments were collected for further analysis.

The 26 journalists were from the same cohort as the original study (Graham and Wright Citation2015), which focused on a random sample of journalists who wrote articles about the Copenhagen Climate Change Summit in the Guardian.Footnote3 In total, 21 of the sampled journalists were male, and all but one was white. While the majority were environmental journalists, it also included journalists from beats such as politics, business, science, and media. Furthermore, several of the environmental journalists have gone on to work on other beats, and this is likely to make the sample more representative than if all were from a single beat. The decision to focus on the same group of journalists at The Guardian was made for two reasons. First, as noted above, interviewees in our previous study largely reported being engaged in comment spaces and that it was positively impacting their practice – but there was limited evidence of actual comments by journalists in the sample for the content analysis. This may have been because of a short sample period when environment journalists were particularly busy, or it may be that the engagement was overstated. How journalists comment remains an important and unanswered question. Second, given the need for longitudinal studies, we chose to focus on the same journalists and to contextualise this with the overarching analysis of all comments. Importantly, this allowed us to draw on the first phase of the interviews so we could assess how and why practice has evolved.

Interviews

The semi-structured interviews were conducted in two phases. In phase one (2012), 10 journalists and two affiliated contributors were interviewed, plus the head moderator (the others declined/did not reply). In phase two (2017–18), we attempted to re-interview the original cohort of interviewed journalists, managing to re-interview 5. While the smaller sample is a limitation, we draw greater confidence that they reflect broader practice because all of the responses were strikingly similar. A second limitation is that none of the five female journalists from the original sample agreed to be interviewed in the first phase. Given our concerns over this limitation, we re-contacted the five female journalists from our original sample to see if they would be interviewed, but none replied (most have left). The one Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) journalist was interviewed in round 1. Building on the identified need for analysis of longitudinal change, the second round of interviews focused on their perception of comments over time; how their own practice had changed over time; and what had driven these changes in practice. In this article, we only quote from the second phase of interviews, but refer to the earlier published work. All interviews were transcribed, and they were analysed by two authors.

Content Analysis

For the content analysis, the unit of analysis was the comment, and the context unit of analysis was the article and comment thread in which the comment was made. Our code frame was built from the existing theoretical and empirical literature, the findings from our earlier study, and it was also supported by the interview data in phase two. A pilot study was also conducted to assess whether the codes were capturing the content of comments; no changes were necessary. First, we coded what can broadly be described as context: the genre of the article (e.g., news article, feature, blog post). Genre is important because it structures the form of news content and this may influence reader's expectations both for the article, and potentially in the comments too (Broersma Citation2010). It was assumed that there would be variations in how journalists’ comment depending on the genre of the article, with formats such as blogs and commentaries – where there is arguably a norm of reciprocity – being more interactive (Wright Citation2008). Second, we coded the section in which the article was placed (e.g., environment, politics, UK). The section was coded because this is an indicator of the topic of the article as categorised by the Guardian, and we assumed that the topic might impact the willingness to comment because it can influence the nature of the debate (Graham and Wright Citation2015).Footnote4 Furthermore, interviewees stated that there were different approaches to commenting across different sections, and thus this was considered important. Third, we coded whether the comment occurred under an article they had authored or was under another journalist's article (which might indicate a deeper engagement with comment spaces).

Fourth, we operationalised Lewis, Holton, and Coddington’s (Citation2014) concept of reciprocal journalism, in which they distinguish between direct, indirect, and sustained reciprocity. A direct reply to another commenter is considered direct reciprocity and a general (undirected) reply to a thread is deemed indirect reciprocity. Lewis, Holton, and Coddington (Citation2014, 235) provide less information to guide the operationalisation of sustained reciprocity, but they note it may be both direct and indirect. Thus, we argue that if journalists comment more than once in a thread (direct or indirect), it is a form of sustained reciprocity. Furthermore, following their emphasis on the temporal dimension to sustained reciprocity, we further argue that a journalist who comments regularly over time – even if only once per thread – is also engaged in sustained reciprocity because they show a commitment to the community. This was operationalised as more than 100 comments in total, as it indicated sustained engagement BTL. To assess reciprocity all journalist comments were coded in context by reading the comments and determining if they were a direct reply or general comment. While this process is time consuming, just focusing on threading (i.e., when someone clicks reply to a person) is often inaccurate as people often reply without doing this, and may press reply without actually replying to the person.

Finally, we coded the dominant function of the comment. While reciprocity is interesting – it is argued that the fact of engagement should not be separated from its content. Thus, here we propose to look not just at whether they engage, but how. Thirteen functions were identified through the literature review (see, e.g., Brems et al. Citation2017 – ).

Table 1. Overview of coding categories for the function of journalists’ comments.

In those cases where a comment contained multiple functions, coders were trained to use a set of rules and procedures for identifying a single dominant function (e.g., the function comprising of the most characters). Inter-coder reliability was conducted on a random sample of 250 comments by three coders (Riffe, Lacy, and Fico Citation2005), and focused on the latent codes only. Calculated using Cohen's Kappa, coefficients met appropriate acceptance levels (Viera and Garrett Citation2005): reciprocity (.78) and function (.77). While also forming part of the content analysis, genre, section and authorship were highly manifest variables, where many of the codes were in the article URL itself (where the coder drew them from), and were therefore not subject to inter-coder reliability tests.

The Evolution of Comment Spaces at The Guardian (RQ1)

It is hard to assess and verify how the total number of comments has evolved, as the Guardian does not report this data. It has stated that they received around 600,000 comments a month in 2013 and a total of 9,035,964 comments in 2013.Footnote5 Gardiner reports that: “Overall the volume of comments increased dramatically – from under one million in in 2007 to 18 million in 2015” (Citation2018, 598). As explained above, we assessed this manually using the date-stamped permalinks to each comment; we did not scrape the comments. Thus the data presented here should be treated as an estimate. However, it correlates with what the Guardian has reported (Elliott Citation2012). There is a variation with what Gardiner reports for 2015, but this appears to be because we included all comments, including ones that are no longer visible, were deleted and so on.

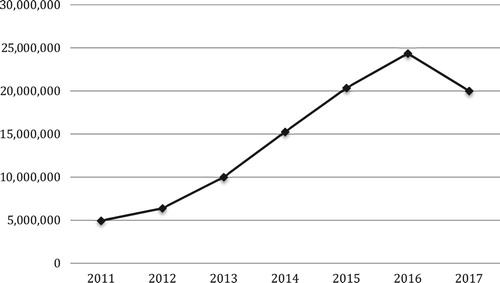

As shows, comments have risen rapidly since 2011 when 5 m were made to a peak of 24.3 m in 2016, before falling to 20 m in 2017 – though still far more than a few years ago. While part of the explanation is that the Guardian's audience has multiplied over the period, with international bureaus in the USA and Australia and a number of big stories, the rise suggests that commenting grew exponentially in popularity. The recent fall in comments may be linked to an apparent decrease in the number of articles open to comments (see ), or it may be that people are moving to other formats because of concerns over tone, abuse, and the like. Having provided the broader commenting context, we now turn to the 26 journalists in our sample for the remainder of the analysis.

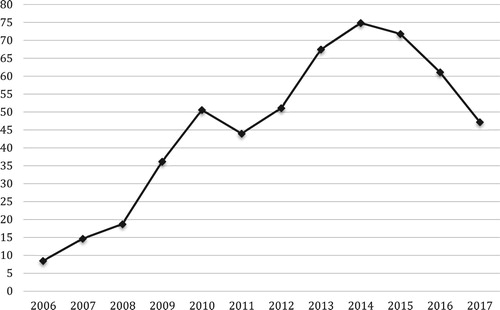

First, we assessed whether the articles written by the 26 journalists were opened to comments (). Moderating comments is a significant expense: the Guardian employs numerous moderators. While comments may provide economic (e.g., stickiness, longer time-on-site, and richer metadata generate advertising revenue), and journalistic benefits (Graham and Wright Citation2015), poorly moderated comments “devalues our journalism and offends our readers” (Pritchard Citation2016). The Guardian considers both their moderating capacity and the nature of the topic (comments are generally not opened on the topics of race, immigration, and Islam) when deciding which stories to open to comment (Pritchard Citation2016). In certain circumstances, all comments may be pre-moderated, but the general process is user-led flagging, and moderators may close comments early if threads degenerate (Graham and Wright Citation2015).

The data show that the number of articles opened to comments grew rapidly until 2014 when 75% of articles were opened, declining to 48% in 2017.Footnote6 Regarding our sampled journalists, there were variations from journalist to journalist – four journalists had over 80% of all of their articles open to comments. Furthermore, the journalists are also now writing fewer stories. Interviewees reported that this was a change in strategic direction by the new editor, Katherine Viner, to “do fewer stories and do them well rather than just churn through immense numbers of stories that most people don't read” (Journalist 1). As the journalists wrote fewer stories, and fewer stories were opened to comments, the total volume of comments spiked. This suggests that to cope with the surge in comment volume, fewer articles were opened to comment. This might help to limit the rise in volume, or at least centralise the comments onto a smaller group of stories to make moderation easier. To examine this further, we look at the average number of comments per open article in our sample.

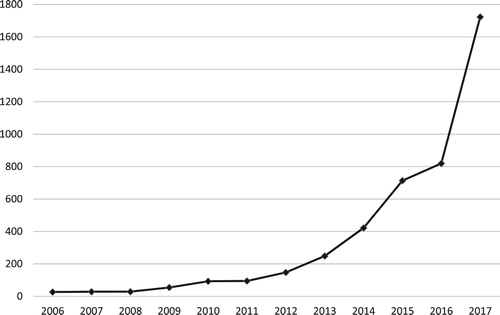

In the sample the average number of comments per open article has gone up exponentially since 2013 (), spiking as the number of articles with open comments declined. While this may help moderators cope, both the quantitative and interview data presented below suggests that rising comment volume negatively impacted the ability of journalists to engage – supporting Gardiner's paradox argument.

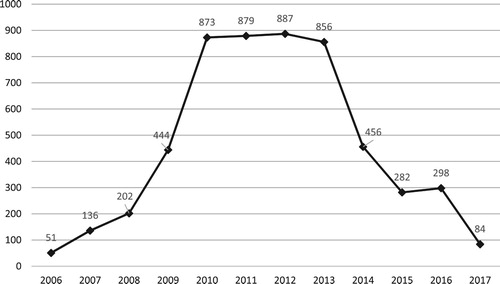

Focusing now on the journalists’ own comments (), the pattern of participation among the 26 journalists is striking, with a sharp rise from 2006 to 2010, at which point there was a levelling out, before a similarly sharp decrease from 2013 to 2015, then again another decrease in 2017 (). In total, the 26 journalists posted 5448 comments, with 64.1% of these occurring between 2010 and 2013. The average number of comments posted by the journalists was 209.54, but this varied significantly between the journalists (SD = 405.13): four journalists posted no comments while three “super-posters” (Graham and Wright Citation2014) had made over a thousand comments in total.

The participation of female and ethnic minority journalists is particularly important given the abuse towards these groups (Gardiner Citation2018). The 5 female journalists in the sample had made a total of just 115 (2.1%) comments, while the one (male) BME journalist had made a total of 157 comments over the sample period. While further systematic research is needed, it seems likely that female journalists comment significantly less - probably due to incivility and abuse (Gardiner Citation2018).

The Drivers of Change in Journalist Participation (RQ2)

This section asks why comment behaviour by journalists has changed, using interview data. Comparing the interview data from 2012 and 2017–18, there were clear differences in the way that journalists perceived comment spaces. In 2012, the interviewees were, on the whole, positive about the role of comment spaces, speaking enthusiastically about various benefits for their own journalistic practice, as well as the broader culture of participation they brought to the Guardian website (Graham and Wright Citation2015). In the second phase interviewees were much more negative:

I think sadly, my experience since we last spoke, I feel like I’ve changed from a fairly enthusiastic advocate of debate in the comment section to maybe a more jaded […] and reluctant participant who feels that it's not rewarding in terms of the time you spend and the energy you put in. (Journalist 1)

The single most significant change was the increase in the volume of comments – as shown in the figures above. The journalists reported that this directly impacted their practice:

The main thing is just the sheer volume. […] In terms of the tenor of the conversations, I don't think they’ve changed that much, to be honest with you. I think it's still quite polarised and you still have your mix of quite constructive, interesting people adding to the conversation and people who are just trying to derail it for some agenda or amusement. So I don't think that's changed hugely, but the one thing that has changed is volume. Which, as a journalist does make it tricky because the one thing you don't have a lot of is time. So, just trying to – getting into a thread early in the past might have changed the direction it went in. These days the conversation can be 50, 100, 200 comments before you’ve even had a chance to respond and it's not really worth bothering by that point. (Journalist 3)

Journalist 2 emphasised concerns over the tone of comments, which were initially “polite” but “within about three months the whole thing had gone completely hysterical.” Journalist 1 was similarly concerned about abuse and incivility: a “lot of the time it leaves me feeling emotionally not so good, so why would I … there's not that much incentive to go into it. You sort of go into it with your teeth slightly grit”. Tone was perceived to differ by topic, with comments in the environment section considered to be higher quality. The environment section was also said to have placed more weight on comments than other sections because it “has never had a dedicated place in the paper” (Journalist 3). Another noted that when they moved from the environment to a politics beat comments were “much more vituperative” and “the criticism obviously hurt from time to time” (Journalist 1).

Another change was that comment sections had lost their novelty, and journalists had shifted their engagement to Twitter, which was seen as more valuable:

My sense is that there may be a slight weariness now, world-weariness, of the journalists that just basically can't be bothered now to go below the line and get involved compared to what it was six, seven years ago, when it was a bit more interesting and exciting. Maybe the novelty's slightly worn off … (Journalist 4)

One final factor that impacted how journalists engaged in the comments was a change in editorial direction. Comments were championed by then editor, Alan Rusbridger, particularly around the time of the Open Journalism initiative (around 2012). Journalist 1 explained:

During the Rusbridger time, the Guardian was very, very, it was, what's the word? It was incredibly optimistic about what the Web represents and the potential for online discussion and public discourse and reaching out to huge audiences and sharing and we try to do that. I think we were very successful in doing that under Rusbridger.

Context, Function and Reciprocity (RQ3)

The first step was to assess whether journalists were commenting on their own articles, or under someone else's. It was assumed that the vast majority would be under their own articles, given time and other pressures, and that commenting under another journalist's article was an indicator of a deeper level of engagement with the comment spaces. A significant minority (16.5%) of comments were under other people's work. To help understand this finding, a qualitative reading of the comments was undertaken. The majority of the comments were by a journalist who had an editorial function as part of their role. They were particularly in the blog and comment areas, with the editor responding to comments on behalf of the author. When this author shifted roles, these kinds of comments largely stopped (this was confirmed in an interview). There were also examples of journalists commenting seemingly for personal interest and humour – a more organic form of engagement that may suggest a more general interest in comments – but these were less frequent.

Focusing on the genre of article under which journalists commented, nearly half (49.1%) of comments were under blogs and columns (). Comment is FreeFootnote7 (CiF) articles accounted for nearly a quarter (23.4%) of the comments posted. Interestingly, 91% of these comments were posted beneath their own (authored) articles, often defending via arguing and debating (see function category below) the opinions, claims, and arguments made in their CiF articles. analyses the news section in which journalists’ commented. Given that our original sample focused on environmental journalists, it is unsurprising that this section received the most comments. That said, journalists did comment in a wide range of news sections.

Table 2. Genre of article under which journalists commented (N = 5448).

Table 3. News section under which journalists commented (N = 5448).

Turning to the assessment of reciprocity (Lewis, Holton, and Coddington Citation2014), 85% of BTL comments by journalists were in reply to a specific user (direct reciprocity) with 15% being indirect (general reciprocity). We assessed sustained reciprocity in two ways. First, focusing on individual threads we found that while 1620 threads had only one comment from a journalist, there were 958 threads with at least two comments (3828 total comments). The most comments in one thread were 57, and there were 56 threads with more than 10 comments by journalists – indicative of deeper engagement (often they were arguing and debating, or had called for reader participation). Second, focusing on responses over time, seven of the 26 journalists had made a total of over 100 comments and were deemed as engaging in sustained reciprocity as individual journalists. These journalists were, unsurprisingly, responsible for the bulk of both forms of sustained reciprocity. Overall, we conclude that direct and sustained reciprocity were the dominant forms of communication amongst the Guardian journalists in our sample, but this was driven largely by a core group of highly engaged journalists.

It was not possible to read all of the comments to see if commenters replied to the journalist. While noting the limitations outlined above, the number of threaded replies (i.e., someone clicks reply to journalist 1 and posts a comment that is directed at them) to journalist comments was assessed. Interestingly, on average there were 1.7 replies to each journalist comment. While this is direct reciprocity and may be sustained, it seems surprising that, with the sheer volume of comments, people rarely replied directly to journalists.

Finally, the analysis of the dominant function of each comment made by the journalists is presented. In doing this, the article sheds new light on the nature of journalistic contributions to comment spaces, and in what ways these might represent new forms of journalistic practice. It also helps to further illuminate the assessment of reciprocal journalism: with the exception of analysis/interpretation (14.3%) and promotion (0.7%), all of the function codes required the journalist to have read user comments and to be engaging in some form of dialogic exchange. Three key findings emerge from the data.

The first is the sheer range and diversity of activities that journalists were undertaking in comment spaces, with no single function dominating (see ). These ranged from low-cost and quick acknowledgements, further information or clarifications, to higher threshold activities requiring cognitive investment such as arguing and debating.

Table 4. Dominant function of comment (N = 5448).

The second key finding is how repertoires of commenting behaviour are nuanced according to the genre and section-specific norms. For example, shows that arguing and debating (22.4%) was narrowly the most common function of journalist comments overall. But beneath this figure, it was far more common in CiF articles (45.8% of all comments within this genre) than news articles/features (17.5%) or blogs/columns (16.4%); and more prevalent in sections such as opinion (44.5%) than environment (16.1%) or science (11.9%). Typically, opinion articles received the most reader comments. As a result, heated debates often emerged, which journalists then engaged in. In this often adversarial atmosphere, journalists retained a role of authority source, typically defending their position, and adding further analysis and information to their argument.

If acting as an authority source is a longstanding role of the journalist, then within the other news genres, we saw more evidence of behaviours that challenge this professional norm. This links to the third key finding: that journalists are using comment spaces to reflect upon and improve their journalism. Three function codes directly addressed this point: correction/clarification/retraction (12.3%), journalism practice (12.9%), and requesting reader input (2.8%). Normatively, the latter two functions are of particular interest for journalism studies, as they hint towards a more open and collaborative form of journalism that scholars had hoped the internet might facilitate (Bruns Citation2005). Here, the comment space is used to utilise the resources and expertise of readers for future stories (reader input) and reflect upon the process of journalism itself (journalism practice) based on the comments from readers. Environment journalists from our 2012 interviews spoke with great enthusiasm about how they used comments fields for such purposes (Graham and Wright Citation2015). These findings suggest that journalists across a number of other beats also gained similar benefits.

Conclusion

Through the use of a multi-method design, this paper has documented how Guardian journalists engage in comment spaces; what factors shape this engagement; and how this has evolved over 11 years. The Guardian represents a compelling case study with which to examine these questions, as it was an early and prominent adopter of reader comment sections. This study has made a number of important findings.

First, it expands our knowledge of comment spaces through its focus on both journalists and news consumers, and the interactions between the two. Our data attests to the considerable interest in comment spaces amongst readers, with exponential growth in user commenting during the sample period. A decline in commenting during 2017 – though still hugely popular – may be due to reduced numbers of articles opened to comment; participants being driven away by incivility and abuse; or a shift to other websites or social media.

Second, this study has found that, quantitatively speaking, there was significant engagement below the line by many of the journalists in the sample, though this has declined somewhat in recent years. Many reasons for this decline were identified during the interviews, though unlike most previous literature, these did not include professional journalistic norms (Domingo Citation2008; Hermida and Thurman Citation2008; Nielsen Citation2014). Instead, they concern the scale of reader engagement BTL; a shift to Twitter; editorial leadership and associated incentive structures; and a broader response to shifting cultures of the internet. Of particular concern here is the perception of a growing culture of abuse and harassment. We suspect it is no coincidence that whilst 19% of journalists in the sample were female, they accounted for only 2.1% of all comments. Where journalist abuse occurs in online spaces, one coping strategy is to disengage (Chen et al. Citation2018; Gardiner Citation2018).

Third, this study operationalised and applied Lewis, Holton, and Coddington’s (Citation2014) concept of reciprocal journalism to the Guardian's comment spaces. The analysis finds that journalists were largely engaged in direct reciprocity (85% of comments). This was also often sustained reciprocity: 70.3% of comments were made in a thread with two or more journalist comments, and there were numerous threads with multiple comments by a journalist – often arguing and debating. Furthermore, 27% (7) of journalists had made more than 100 comments in total – indicative of sustained reciprocity over time. However, on average a journalist comment received only 1.7 replies. Given the millions of comments and comparatively infrequent comments by journalists, this is surprisingly low. Further research is needed into how commenters perceive journalist comments BTL, but it may be that they would prefer journalists to stay above the line.

A fourth key contribution is to extend the concept of journalistic reciprocity to assess the function of journalists’ comments. The data shows that when journalists comment, they do so in a variety of ways. Their comments are often substantive, significantly adding to the story by, for example, adding in new information and evidence, and defending and explaining their journalism practice. Furthermore, the content analysis of comment functions demonstrated a predominance of interactive practices in comment spaces.

In summary, this study has documented the collision between the potential of open journalism projects and the realities of participating in and managing online news communities. As other studies have found (e.g., Binns Citation2012), methods of managing such communities have lagged. In contrast to the hope and optimism of the Rusbridger era, the Guardian now speaks of implementing “policies and procedures to protect our staff from the impact of abuse and harassment online” (Hamilton Citation2016, np). In spite of the myriad challenges, in the language of Domingo (Citation2008), we conclude that interactivity is not a myth, but it is uneven. Some journalists have engaged extensively BTL, and in substantive ways that significantly add to journalism practice. Participation has, however, declined in recent years. We link this to what Gardiner (Citation2018) has described as a paradoxical challenge for comment spaces. On the one hand, comments at the Guardian are increasingly successful when measured in terms of the volume of comments, and this likely has economic benefits. On the other hand, this has made it more difficult for journalists to engage due to time constraints and perceived lower journalistic benefits. Ultimately, the costs for journalists are now generally thought to outweigh the benefits, and many have moved their participatory practices to Twitter for story development and reader interaction. Future research might comparatively analyse how journalists engage (or not) across different platforms; to compare how gender and other demographic characteristics relate to, and impact, commenting; and how the audience perceives and responds to such engagement.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Scott Wright http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4087-9916

Daniel Jackson http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8833-9476

Todd Graham http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5634-7623

Notes

1 Astroturfing refers to the manipulation of online debate by people or groups posting content (paid or unpaid) to support an agenda (e.g., lobby groups, government-backed). The Guardian has claimed that there have been astroturfing of its comments spaces around the topic Ukraine/Russia and fossil fuels (Elliott Citation2014).

2 Furthermore, five pages were removed (the website stated that: “This could be because it launched early, our rights have expired, there was a legal issue, or for another reason.”), 6 were to blogs using an old format in which comments were not accessible, 3 were to cartoons where the number of comments could be seen but comments would not load and appeared to be a page formatting issue, and 8 URLs were inactive. The remainder were active links to comments. Messages removed by moderators are visible, though it is unclear what happens if specific accounts or articles are deleted (this may explain the missing comments).

3 The original study involved a sample of 85 articles written by 47 separate authors. However, only 27 of these were considered Guardian journalists, and we focused on these for the interviews. We removed one person from the sample for this analysis as it was determined they were not a journalist, and had only co-authored one piece on the environment – thus the sample size is 26 (they were not interviewed in round one).

4 One journalist, in particular, in round one of interviews noted that they had changed to a politics beat, and that the tone of the comments was very different and they had decided to stop commenting.

5 Note that this does not cover all of 2013, and we do not know whether this is all messages or excludes moderated posts.

6 Determining how many articles are opened to comment is difficult. The Guardian does not state that an article was not opened to comments; they merely show the comments, or it is blank. We can assume that most articles with no comments were not opened as most articles receive numerous comments (particularly in recent years), but it seems likely that some were opened, no one commented, and comments were closed. Given this, we focus on articles with at least one comment, so that we know for sure that comments were opened.

7 Comment is Free is the “home of Guardian and Observer comment and debate” (https://www.theguardian.com/help/2008/jun/03/1). It incorporates all of the regular Guardian and Observer main commentators, but is best known for its outside contributors such as politicians, academics, writers, scientists, and activists.

References

- Barnes, Renee. 2014. “The ‘Ecology of Participation’. A Study of Audience Engagement on Alternative Journalism Websites.” Digital Journalism 2 (4): 542–557. doi:10.1080/21670811.2013.859863.

- Bergström, Annika, and Ingela Wadbring. 2015. “Beneficial Yet Crappy: Journalists and Audiences on Obstacles and Opportunities in Reader Comments.” European Journal of Communication 30 (2): 137–151. doi:10.1177/0267323114559378.

- Binns, Amy. 2012. “Don’t Feel the Trolls! Managing Troublemakers in Magazines’ Online Communities.” Journalism Practice 6 (4): 547–562. doi:10.1080/17512786.2011.648988.

- Borger, Merel, Anita van Hoof, Irene Costera Meijer, and José Sanders. 2013. “Constructing Participatory Journalism as a Scholarly Object: A Genealogical Analysis.” Digital Journalism 1 (1): 117–134.

- Brems, Cara, Martina Temmerman, Todd Graham, and Marcel Broersma. 2017. “Personal Branding on Twitter: How Employed and Freelance Journalists Stage Themselves on Social Media.” Digital Journalism 5 (4): 443–459. doi:10.1080/21670811.2016.1176534.

- Broersma, Marcel. 2010. “Journalism as a Performative Discourse. The Importance of Form and Style in Journalism.” In Journalism and Meaning-Making: Reading the Newspaper, edited by Verica Rupar, 15–35. Cresskill: Hampton Press.

- Bruns, Axel. 2005. Gatewatching: Collaborative Online News Production. New York: Peter Lang.

- Chen, Gina Masullo, Paromita Pain, Victoria Y Chen, Madlin Mekelburg, Nina Springer, and Franziska Troger. 2018. “‘You Really Have to Have a Thick Skin’: A Cross-Cultural Perspective on How Online Harassment Influences Female Journalists.” Journalism: Theory, Practice, and Criticism, 1–19. doi:10.1177/1464884918768500.

- Coe, Kevin, Kate Kenski, and Stephen A. Rains. 2014. “Online and Uncivil? Patterns and Determinants of Incivility in Newspaper Website Comments.” Journal of Communication 64 (4): 658–679. doi:10∂i.1111/jcom.12104.

- Dailey, Larry, Lori Demo, and Mary Spillman. 2008. “Newspaper Political Blogs Generate Little Interaction.” Newspaper Research Journal 29 (4): 53–65. doi:10.1177/073953290802900405.

- Deuze, Mark. 2003. “The Web and Its Journalisms: Considering the Consequences of Different Types of Newsmedia Online.” New Media & Society 5 (2): 203–230. doi:10.1177/1461444803005002004.

- Deuze, Mark, Christoph Neuberger, and Steve Paulussen. 2004. “Journalism Education and Online Journalists in Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands.” Journalism Studies 5 (1): 19–29. doi:10.1080/1461670032000174710.

- Domingo, David. 2008. “Interactivity in the Daily Routines of Online Newsrooms: Dealing with an Uncomfortable Myth.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 13 (3): 680–704. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2008.00415.x.

- Domingo, David, Thorsten Quandt, Ari Heinonen, Steve Paulussen, Jane B. Singer, and Marina Vujnovic. 2008. “Participatory Journalism Practices in the Media and Beyond: An International Comparative Study of Initiatives in Online Newspaper.” Journalism Practice 2 (3): 326–342. doi:10.1080/17512780802281065.

- Elliott, Chris. 2012. “The Readers’ Editor on … the Switch to a ‘Nesting’ System on Comment Threads.” The Guardian, December 24. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2012/dec/23/switch-nesting-system-comment-threads.

- Elliott, Chris. 2014. “The Readers’ Editor on … Pro-Russia Trolling Below the Line on Ukraine Stories.” The Guardian, May 4. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/may/04/pro-russia-trolls-ukraine-guardian-online.

- Erjavec, Karmen, and Melita P. Kovačič. 2012. “‘You Don’t Understand, this is a New War!’ Analysis of Hate Speech in News Web Sites’ Comments.” Mass Communication and Society 15 (6): 899–920. doi:10.1080/15205436.2011.619679.

- Finley, Klint. 2015. “Have Comment Sections on News Media Websites Failed?” Wired, May 10. https://www.wired.com/2015/10/brief-history-of-the-demise-of-the-comments-timeline/.

- Freelon, Deen. 2015. “Discourse Architecture, Ideology, and Democratic Norms in Online Political Discussion.” New Media & Society 17 (5): 772–791. doi:10.1177/1461444813513259.

- Garden, Mary. 2016. “Australian Journalist-Blogs: A Shift in Audience Relationships or Mere Window Dressing?” Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 17 (3): 331–347. doi:10.1177/1464884914557923.

- Gardiner, Becky. 2018. “‘It’s a Terrible Way to Go to Work:’ What 70 Million Readers’ Comments on the Guardian Revealed about Hostility to Women and Minorities Online.” Feminist Media Studies 18 (4): 592–608. doi:10.1080/14680777.2018.1447334.

- Gardiner, Becky, Mahana Mansfield, Ian Anderson, Josh Holder, Daan Louter, and Monica Ulmanu. 2016. “The Dark Side of Guardian Comments.” The Guardian, April 12. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/apr/12/the-dark-side-of-guardian-comments.

- Graham, Todd, and Scott Wright. 2014. “Discursive Equality and Everyday Talk Online: The impact of ‘Super-Participants’.” Journal of Computer- Mediated Communication 19 (3): 625–642.

- Graham, Todd, and Scott Wright. 2015. “A Tale of Two Stories from ‘Below the Line’: Comment Fields at the Guardian.” International Journal of Press/Politics 20 (3): 317–338.

- Hamilton, Mary. 2016. “The Guardian Wants to Engage with Readers, But How We Do It Needs to Evolve.” The Guardian, April 8. https://www.theguardian.com/media/2016/apr/08/the-guardian-wants-to-engage-with-readers-but-how-we-do-it-needs-to-evolve.

- Hermida, Alfred, and Neil Thurman. 2008. “A Clash of Cultures: The Integration of User-Generated Content within Professional Journalistic Frameworks at British Newspaper Websites.” Journalism Practice 2 (3): 343–356. doi:10.1080/17512780802054538.

- Hess, Kristy, and Lisa Waller. 2014. “Geo-Social Journalism: Reorienting the Study of Small Commercial Newspapers in a Digital Environment.” Journalism Practice 8 (2): 121–136. doi:10.1080/17512786.2013.859825.

- Ihlebæk, Karoline Andrea, and Arne H Krumsvik. 2015. “Editorial Power and Public Participation in Online Newspapers.” Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 16 (4): 470–487. doi:10.1177/1464884913520200.

- Jönsson, Anna Maria, and Henrik Örnebring. 2011. “User-Generated Content and the News: Empowerment of Citizens or Interactive Illusion?” Journalism Practice 5 (2): 127–144. doi:10.1080/17512786.2010.501155.

- Larsson, Anders Olof. 2011. “Interactive to Me – Interactive to You? A Study of Use and Appreciation of Interactivity on Swedish Newspaper Websites.” New Media & Society 13 (7): 1180–1197. doi:10.1177/1461444811401254.

- Larsson, Anders Olof. 2017. “In It for the Long Run? Swedish Newspapers and their Audiences on Facebook 2010–2014.” Journalism Practice 11 (4): 438–457. doi:10.1080/17512786.2015.1121787.

- Lewis, Seth C. 2012. “The Tension between Professional Control and Open Participation: Journalism and Its Boundaries.” Information, Communication and Society 15 (6): 836–866. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2012.674150.

- Lewis, Seth C., Avery E. Holton, and Mark Coddington. 2014. “Reciprocity Journalism: A Concept of Mutual Exchange between Journalists and Audiences.” Journalism Practice 8 (2): 229–241. doi:10.1080/17512786.2013.859840.

- Manosevitch, Edith, and Dana Walker. 2009. “Readers Comments to Online Opinion Journalism: A Space of Public Deliberation.” 10th International Symposium on Online Journalism, Austin, TX, April 17–18.

- Martin, Fiona. 2015. “Getting My Two Cents Worth in: Access, Interaction, Participation and Social Inclusion in Online News Commenting.” In #ISOJ, the Official Research Journal of International Symposium on Online Journalism.

- Meyer, Hans K., and Michael C. Carey. 2014. “In Moderation: Examing How Journalists’ Attitudes towards Online Comments Affect the Creation of Community.” Journalism Practice 8 (2): 213–228.

- Nielsen, Carolyn E. 2014. “Coproduction or Cohabitation: Are Anonymous Online Comments on Newspaper Websites Shaping News Content?” New Media & Society 16 (3): 470–487. doi:10.1177/1461444813487958.

- Pavlik, John. 2001. Journalism and New Media. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Pritchard, Stephen. 2016. “The Readers’ Editor on … Closing Comments Below the Line.” The Guardian, March 27.

- Reader, Bill. 2012. “Community Journalism: A Concept of Connectedness.” In Foundations of Community Journalism, edited by Bill Reader, and John Hatcher, 3–20. London: Sage.

- Riffe, Daniel, Stephen Lacy, and Frederick G. Fico. 2005. Analyzing Media Messages: Using Quantitative Content Analysis in Research. New York: Routledge.

- Robinson, Sue. 2010. “Traditionalists vs. Convergers: Textual Privilege, Boundary Work, and the Journalist—Audience Relationship in the Commenting Policies of Online News Sites.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 16 (1): 125–143. doi:10.1177/1354856509347719.

- Robinson, Sue. 2014. “Introduction.” Journalism Practice 8 (2): 113–120. doi:10.1080/17512786.2013.859822.

- Ruiz, Carlos, David Domingo, Josep Lluís Micó, Javier Díaz-Noci, Koldo Meso, and Pere Masip. 2011. “Public Sphere 2.0? The Democratic Qualities of Citizen Debates in Online Newspapers.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 16 (4): 463–487. doi:10.1177/1940161211415849.

- Rusbridger, Alan. 2012. “The Guardian: A World of News at Your Fingertips.” The Guardian, February 29. https://www.theguardian.com/help/insideguardian/2012/feb/29/open-journalism-at-the-guardian.

- Santana, Arthur. 2010. “Conversation or Cacophony: Newspapers Reporters’ Attitudes Toward Online Reader Comments.” Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, Denver, CO, August 4.

- Sindorf, Shannon. 2013. “Deliberation or Disinhibition? An Analysis of Discussion of Local and National Issues on the Online Comments Forum of a Community Newspaper.” The International Journal of Technology, Knowledge, and Society 9 (2): 157–171.

- Singer, Jane B., Alfred Hermida, David Domingo, Ari Heinonen, Steve Paulussen, Thorsten Quandt, Zvi Reich, and Marina Vujnovic. 2011. Participatory Journalism: Guarding Open Gates at Online Newspapers. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Strandberg, Kim, and Janne Berg. 2013. “Online Newspapers’ Readers’ Comments – Democratic Conversation Platforms or Virtual Soapboxes?” Comunicação e Sociedade 23: 132–152.

- Viera, Anthony J., and Joanne M. Garrett. 2005. “Understanding Interobserver Agreement: The Kappa Statistic.” Family Medicine 37 (5): 360–363.

- Viscovi, Dino, and Malin Gustafsson. 2013. “Dirty Work. Why Journalists Shun Reader Comments.” In Producing the Internet: Critical Perspectives of Social Media, edited by Tobias Olsson, 85–101. Gothenburg, Sweden: Nordicom, University of Gothenburg.

- Wright, Scott. 2008. “Read My Day? Communication, Campaigning and Councillors’ Blogs.” Information Polity 13 (1/2): 41–55.

- Wright, Scott. 2012. “Politics as Usual? Revolution, Normalization, and a New Agenda for Online Deliberation.” New Media & Society 14 (2): 244–261.

- Ziegele, Marc, Nina Springer, Pablo Jost, and Scott Wright. 2017. “Online User Comments across News and Other Content Formats: Multidisciplinary Perspectives, New Directions.” Studies in Communication and Media (SCM) 6 (4): 315–332.