ABSTRACT

In this paper, we explore the ways in which we can employ arts-based research methods to unpack and represent the diversity and complexity of journalistic experiences and (self) conceptualisations. We address the need to reconsider the ways in which we theorise and research the field of journalism. We thereby aim to complement the current methodologies, theories, and prisms through which we consider our object of study to depict more comprehensively the diversity of practices in the field. To gather stories about journalism creatively (and ultimately more inclusively and richly), we propose and present the use of arts-based research methods in journalism studies. By employing visual and narrative artistic forms as a research tool, we make room for the senses, emotion and imagination on the part of the respondents, researchers and audiences of the output. We draw on a specific collaboration with artists and journalists that resulted in a research event in which 32 journalists were invited to collaboratively recreate the “richness and complexity” of journalistic practices.

Introduction

The field of journalism is undergoing major changes. The challenges are so profound that the question that is asked is how it will survive and what shape it will take (Kasem, van Waes, and Wannet Citation2015). With new institutions, publishing platforms, news producers, and ways of working, journalism is more amorphous than ever. In turn, journalists are increasingly making efforts to defend and define what journalism is and what it is for (Carlson and Lewis Citation2015). Such “boundary work” shows that the where, what and who of journalism are in flux. In this article, we address the need for complementary research approaches to address the changes in journalism.

First, “where” journalism is produced is no longer easily recognisable. Traditionally, journalism has been performed in editorial settings such as the newsroom. Today, more and more work is done in fluid networks that transcend newsrooms (Heinrich Citation2014; Deuze and Witschge Citation2019). Journalism is done as freelance work, in start-up settings and new constellations. In the Netherlands, for example, already in 2013 more than half of the journalists worked as freelancers or independently (Vinken and IJdens Citation2013). This is impacting journalistic work, as research starts to show (see, for instance, Hunter Citation2015). With myriad spaces and ways of working, researchers are realising that it is increasingly difficult to capture journalistic work (Robinson and Metzler Citation2016).

Second, and related; “what” is produced “for whom” is also shifting. Given the changes, it is important to trace what journalism looks like today, and to research these practices in ways that go beyond current perspectives, distinctions and methodologies. Journalism is deemed an important media genre because it provides information for citizens, mediates between them and their representatives, and holds those in power in check (Peters and Witschge Citation2014). However, in the current media landscape—where journalists have to work more like entrepreneurs and find a balance between commercial and editorial work (Fisher Citation2015; Vos and Singer Citation2016)—we need to reconsider “what” journalism is and how it comes into being (Deuze and Witschge Citation2019).

Third, there are many new actors in the field of journalism gaining prominence, be they marketeers, animators, web developers, hackers or others (the “who”). These actors are looking for new ways to collaborate with each other—in interdisciplinary teams—in order to produce new kinds of journalism that meet changing habits and interests of users. We need to reconceptualise who we consider to be a journalist to gain insight into the broader set of activities performed by those involved in the journalism production process (see also Lewis and Zamith Citation2017; Witschge and Harbers Citation2018).

To this end, we discuss some of our initial experiences using arts-based research approaches for studying journalism. Arts-based research methods are characterised by working towards experiential, bottom-up knowledge (re)presented as an open-ended and imaginative invitation (Shields and Penn Citation2016). Employing an inclusive and collaborative, open-ended approach allows us to acknowledge that “contingency, creativity and complexity are fundamental to our understanding” (Nayak and Chia Citation2011, 283). We first briefly discuss the challenges that developments in journalism pose for researchers in this field, as a number have done before us. We then introduce arts-based research, tracing its origins and discuss the core features that allow us to address the challenges of journalism. In the main part of this article, we focus on our own recent research projects to suggest the specific insights that the application of arts-based research can provide. In our concluding remarks, we discuss some of the challenges that we face in applying this type of research approach.

Transformations in Journalism

Within academia, there have been a number of calls to alter the way that we define and research journalism (see for instance Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2009; Anderson Citation2011). They offer complementary ways of conceptualising journalism from a scholarly perspective (see also the various contributions to the Sage Handbook of Digital Journalism (Witschge et al. Citation2016)). These have been important and insightful additions, that we seek to contribute to by providing a focus on the perspective and experiences of makers. As such we seek to highlight an approach that allows for:

Understanding journalism beyond existing normative frameworks: Inspired by practice theory (Witschge and Harbers Citation2018), we acknowledge that journalism is both a discourse and a set of activities, and that what we understand to be journalism is ever evolving. The question of who counts as a journalist, who as source, subject and/or audience, is even less straightforward given the participatory practices that have increasingly included non-professionals in production processes. Rather than defining it a priori, we want to address the diversity and multiplicity present in the field.

Including seemingly opposing values and practices: Journalists are important but also contested knowledge producers, as many do not simply aim to mirror society, but rather aim to move society (Gyldensted Citation2015). Previous classifications of media practices would try to understand these practices in either/or binary oppositions: objective vs subjective; fiction vs nonfiction; journalism vs art or activism (see, for instance, Wagemans, Witschge and Harbers Citation2018). By acknowledging that media making processes transcend such theoretical frameworks and classifications, we aim to contribute to research approaches, theories and vocabularies that allow us to reflect this. Acknowledging that the media field is characterised by hybridity, “contradictions”, and messiness (Witschge et al. Citation2019), we provide examples of how to research this in a way that engages with the “richness and complexity” (Knowles and Cole Citation2008, 6) of journalistic practices.

Exploring the experiential dimension of practices: By considering journalism as complex and as featuring inconsistencies and dissonances, we aim to provide an understanding of the making processes that corresponds with makers’ experiences. An experientialist approach (how do makers experience making?) provides insights into “feelings, aesthetic experiences, [and] moral practices” (Lakoff and Johnson Citation2003, 193).

Knowledge from within the field: Recognising and embracing the need for experiential knowledge (Wagemans and Witschge Citation2019), we here explore ways to tap into the knowledge of those we are studying in such a way that their insights and knowledge queries are at the heart of the research, rather than an addendum. Including “practitioners as partners in the work of knowledge creation” (Bradbury–Huang, cited in Wagemans and Witschge Citation2019, 214), we explicitly position and consider those involved in the making process as partners rather than “mere” research participants.

As Lewis and Zamith (Citation2017, 111) point out, “the difficulty [is with] (…) understanding this thing called journalism”. To address this difficulty, we propose a methodology that allows us to broaden our perspective to include creativity, diversity and doubt (Costera Meijer Citation2016).

Arts-based Research

As a response to the limits of existing methodologies, and particularly to include non-traditional perspectives and provide other ways of viewing and presenting research, qualitative research has increasingly employed artistic tools and strategies. There are different terms to denote this development, including artistic research (Borgdorff Citation2012), a/r/tography (Springgay, Irwin, and Kind Citation2005) and scholARTistry (Cahnmann Citation2006). We will in this article refer to the commonly used term of arts-based research. In this section, we outline the affordances of arts-based methods for researching how journalists experience their profession.

In the early 1980s, arts-based research methods were developed to complement existing forms of data collection (Cahnmann-Taylor Citation2017). The early arts-based researchers echoed concerns that were at the heart of representational concerns in the social sciences (Cahnmann-Taylor Citation2017). Because of the complexity of our world, social scientists, among other researchers, challenged key assumptions of dominant scholarly knowledge-making practices, including the “presumption of representing or speaking for others” (Brosius Citation2006, 684). This “representational crisis” brought about “multifaceted debates on reflexivity, objectivity, epistemology, culture, ethnography of the world system, and the politics of representation” (Zenker Citation2014: online). The underlying argument is that traditional research methods are insufficient to address the complexity, diversity and messiness of the socio-cultural and political environment (Springgay, Irwin, and Kind Citation2005). Researchers identified the need to reflect on the politics of representation and positionality, making room for more open-ended, participatory, inclusive and experimental ways of conducting research (Cahnmann-Taylor Citation2017). Within anthropology, for instance, this led to the increased popularity of visual anthropology and sensory ethnography—employing film as a participatory and open-ended medium to address cultural diversity (Sniadecki Citation2014).

Arts-based research methods gained momentum parallel to these debates and developments. Though the practices that can be considered part of this research approach have a longer history, the actual term arts-based research was coined by Eisner in 1993 at a conference that was designed to develop research strategies that include aesthetics, artistic expression and methodological experimentation (Barone and Eisner Citation2012a). One of the principal aims is to overcome the dualism between science and the arts. Arts-based research is considered as “an effort to utilize the forms of thinking and forms of representation that the arts provide as a means through which the world can be better understood” (Barone and Eisner Citation2012a, xi).

Whereas in the 1980s and early 1990s most arts-based methods employed writing and linguistic modes of communication and dissemination, currently the research practice includes a broader variety of methods, such as theatre, filmmaking, dance, sketching and printmaking. The proliferation and diversity in these practices have resulted in the proliferation of terms for, and alternatives to, arts-based research such as “(critical) arts-based inquiry” (Finley Citation2005) and “art for scholarship’s sake” (Haywood-Rolling Citation2010), in addition to the ones mentioned above (artistic research, a/r/tography and scholARTistry). The aims and definitions differ slightly, but there is a shared interest in employing artistic tools to study the complexity of lived experience. Arts-based research methods “adapt the tenets of the creative arts in order to address social research questions in holistic and engaged ways in which theory and practice are intertwined” (Leavy Citation2015, 4). In doing so, arts-based researchers aspire to speak to audiences and participants both within and outside scholarly environments, with the aim of presenting open-ended research projects as an imaginative invitation (Shields and Penn Citation2016).

Because of journalism’s ever-changing nature and its rapid socio-cultural and technological developments, we have found arts-based research methods useful to reconsider epistemological and methodological assumptions. Arts-based research allows for the kind of intervention in journalistic practice that enables us to elicit, question and “re-create” its complexity. We highlight three features of arts-based research methodologies that make them particularly complementary to existing methods used in journalism studies. First, the research is participatory, which allows for a bottom-up understanding of the journalistic profession. At various levels, arts-based research strives for inclusivity—echoing the diversity of our cultural and socio-political landscape. Arts-based research allows us to “study with people, rather than making studies of them” (Ingold Citation2018, 11) and as such allows us to include a diversity of perspectives.

Second, arts-based research is specifically suited to research experiences, using artistic forms that are “attentive to the sensual, tactile, and unsaid” (Springgay, Irwin, and Kind Citation2005, 899). It allows us to tell new, experiential stories from the field of journalism (see also Archetti Citation2017). Whether it is via creative writing, filmmaking, drawing or the performative arts, arts-based research methods aspire for ways of knowing that are situated, practical, tactile and lived.

Third, arts-based research can be viewed as an invitation towards interpretation (Shields and Penn Citation2016, 9). Its outcomes are not limited to conference papers and academic writing. Rather, the output of arts-based research may include the production of films, dances, theatre performances, drawings, installation pieces, to name but a few artistic forms. Within arts-based research, knowledge and meaning reside in the production of the research outcomes and artworks, as much as in the interpretation of these works by its audience. Documentary maker and visual anthropologist Sniadecki (Citation2014) summarises a comparable process of “reader” interpretation in his discussion on using film for research: By drawing on the “expansive potential of aesthetic experience and experiential knowledge” we do not suffer from the “reductionism of abstract language” (Sniadecki Citation2014, 26). In this way, we are able to draw from “an expanded field of knowledge production that entails greater involvement from the audience/reader” (Sniadecki Citation2014, 27). The imaginative invitation to interpretation done with arts-based research means that the “the viewer/audience [is invited] to participate in the interpretive processes, rather than crafting definitive representative products” (Shields and Penn Citation2016, 9).

Applying Arts-based Research in Journalism Studies

Arts-based research thus offers ways of understanding the messiness, hybridity and inconsistencies moving through journalism, and does so by positioning the knowledge and experiences from within the field at its core. Providing multiple viewpoints and experiential knowledge on journalism, arts-based research has the potential to challenge strictly defining roles (researcher/practitioner), aims (knowledge/making) and frameworks (theory/practice). Thus, these methods have the potential to do justice to the complexity of a phenomenon, community or issue, by refusing absolutes whilst working towards provisional, perspectival and intersubjective knowledge. In this section, we provide insight into how and to what end we can use arts-based research methods in journalism studies by drawing on our experiences in employing such methods.

As part of two projects funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (Exploring Journalism’s Limits: Enacting and Theorising the Boundaries of the Journalistic Field, number 314-99-205; Entrepreneurship at Work: Analysing Practice, Labour, and Creativity in Journalism, number 276-45-003), we experimented with a number of arts-based research methods to study the lived experiences of journalists in the Netherlands. The journalists who took part in the research projects are mostly working in a new start-up environment, are self-employed or are otherwise at the margins or outside of established legacy media self-representation, but to compare these data we have also included those working at more traditional media outlets. We particularly aimed to address the journalists’ working environments, everyday routines and self-understanding. The art-based projects were conducted between 2017 and 2019, in close collaboration with artists, VersPers (Dutch platform for emerging journalists) and A-Lab (a creative incubator space). The research included visiting newsrooms, organising research workshops and developing interactive assignments in collaboration with artists and journalists.

In this section, we discuss the employment of three arts-based methods to highlight the added value of these approaches for journalism studies. Specifically, we draw on three workshops that we conducted as part of the journalistic research event “Academic (re)searches Journalist” which was organised in collaboration with our partners VersPers and A-lab in May 2018, Amsterdam. The event was open to anyone who was interested in reflecting on the profession and their own role in it. It consisted of five workshops, three of which we unpack in this article (for a discussion of all five workshops, see Witschge, Deuze, and Willemsen Citation2019): (i) The production of a collaborative artwork that represents journalists’ perspectives on their role in society in the form of a cityscape; (ii) Elicited graphic visualisations of journalistic networks to gain insight into how journalists experience the boundaries of journalism; (iii) A fictional letter of resignation, which is based on multiple resignation letters written by journalists and addressed to the journalistic profession.

The Multiplicity of Journalists’ Roles in Society: A Collaborative Artwork

During the past couple of decades there have been myriad attempts to understand and analyse how journalists define their societal roles and profession, whether it presents the journalist as watchdog, lapdog, guard dog, whistle-blower (Christians et al. Citation2009) or how journalists conceptualise journalism—as “selection”, “construction”, or “power game” (Gravengaard Citation2012). With the first study we present here, we aspired to gain insight into the multiplicity of conceptualisations of journalism’s role in society. Rather than suggesting that there is one or a handful of ways in which journalists view their role, we aimed to inspire journalists to consider their envisaged role in society more freely and fully (allowing them to move outside mainstream metaphors and understandings).

To this end, we initiated a collaboration with Yotka Kroeze and Jobbe Holtes from artists’ collective OneDayArtist (https://www.onedayartist.nl), and together designed a workshop for the research event. After a series of conversations with OneDayArtist, specialised in providing workshops using art to broaden perspectives, we settled on the following assignment: Guided by Yotka and Jobbe, journalists would visualise the object in the public realm that represents best their role in society. After a general introduction, participants were invited to consider and write down which three values they deemed key to their work. The workshop (bringing together 10–12 journalists per 30-minute workshop) continued with a meditative visualisation guided by the two artists, who played soundscapes of the built environment, musicalised by nearly imperceptible, low-frequency melodies. They asked participants to close their eyes, so as to fully experience the depth of the soundtrack and to imagine themselves walking around a self-chosen city. The journalists were then asked to think of an object that they could identify with, that is, an object that had the potential of representing and perhaps even embodying their self-image as a journalist, particularly in relation to the key values they identified in the beginning. The participants spent the remaining minutes sketching the object that they felt represented their role best, exchanging thoughts with fellow participants or the workshop leaders if so desired. As such, it was not an entirely individual process: in conversation with artists and other participants, the journalists would also at times reconsider their chosen object.

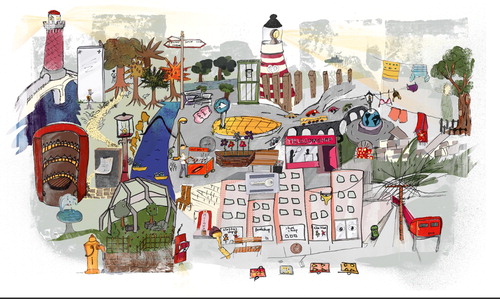

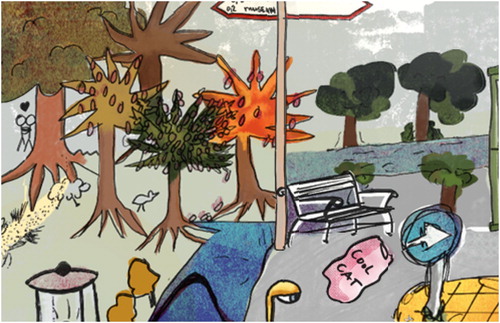

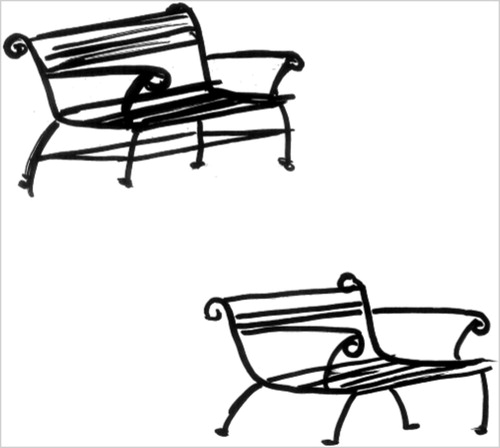

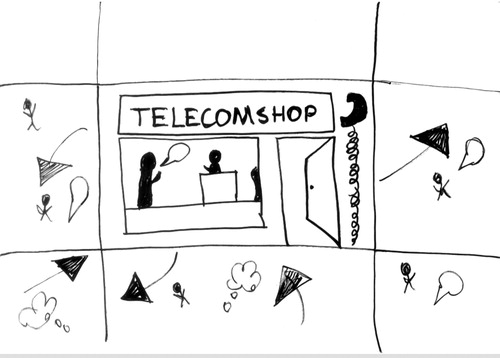

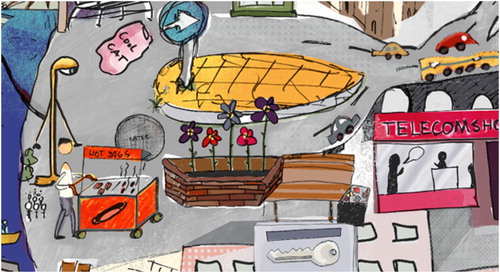

The final artwork () shows the diversity as well as the interrelatedness of the objects, which include a mailbox, a Wizard of Oz-esque yellow brick lane, four trees that symbolise the four seasons, a sponge, clotheslines, a lighthouse, trees, water sources, a hot dog stand, lamp posts and roundabouts. , and show a range of individual sketches of the participants that were then integrated into the final artwork, where the artists incorporated journalists’ responses, sketches and discussions. What is interesting is that although the sketches are already evocative in themselves, the combined artwork, enhanced with composition and colour by the artists from OneDayArtist, is even more powerful in showing how journalistic self-conceptualisations are as expressive and heterogeneous as the built environment (for an explanation of all the different objects, please see the online version of the artworkFootnote1).

Figure 2. Sketch of journalism’s role represented as a public bench: a place to listen to and look at one’s surroundings, 2018.

Figure 3. Sketch of journalism’s role represented as a hot dog salesman: in touch with everyone, regardless of their social background or viewpoints, 2018.

Figure 4. Sketch of journalism’s role represented as a telecom shop: connecting members of society with each other, 2018.

The final artwork provides an imaginative invitation to contemplate what the current, dynamic landscape of journalism could look like. It shows the myriad of roles and perspectives next to each other. Rather than looking for patterns in journalistic self-perceptions about their role in society, and focussing on these, the piece allows for the connections, overlaps and tensions to co-exist. Instead of having individual input which is then analysed for patterns and incongruencies, OneDayArtist created a shared experience within which journalists developed their self-image alongside peers and colleagues, and where each perspective is integrated in the whole (see and for examples of how the sketches () above are integrated into the whole) . Encouraging participants to narrow down a complicated process of reflecting on their identity to three keywords and, ultimately, one sketch, OneDayArtist, opened up a space for imagination, experimentation, associative thinking and, above all, rich storytelling.

Figure 6. Close-up of hot dog stand, roundabout, artwork, lamp post and telecom shop in OneDayArtist’s artwork, 2018.

This provides space for the “viewer” of the artwork to interpret the input of the participants more directly; they are invited to participate in making sense of the data. The journalist-made and journalism-inspired city allows for multiple scales, networks, meanings, textures, affectivities, viewpoints, roles, experiences, affordances to come to the fore within one whole. As such it provides not only a unique insight into but also a unique experience of, the significance of multiplicities, differences and discrepancies in journalists’ experience of their roles and profession, especially given the sensory nature of the artwork.

It is important to note, that though the act of visualising and drawing of objects allowed participants (and the viewer of the artwork) to move beyond the limits of verbal language, discourse is still very much present in the artwork. More often than not, participants discussed, tested, and explained their object before, during and after drawing. These verbal explanations are helpful insofar as they elicit a particular way of interpreting the sketches and artwork: they can contribute to understanding whether the litter bin represents a place where stories are dropped and thus collected, indiscriminate of the types of stories “dropped” into it, or whether it’s the place where the dirt of society can be found. Indeed, the value of such contextualisation made us decide to publish a digital version of the artwork that includes written explanations of the objects on the basis of verbal explanations expressed during the workshop (https://adobe.ly/2lGR0El). At the same time, we might argue that the real promise of such methods of collecting and representing data is actually their open-ended and multi-interpretable nature: adding words, even to contextualise, may strip away from this key feature. It is clear that the two versions of the artwork (a printed version which speaks for itself and a digital interactive version which gives the contextualisation of the objects) provide different experiences of the journalists’ perceived and aspired societal role, as it facilitates a different type of engagement with the material for the audience of the artwork.

Experiencing the Complexity of Professional Boundaries: Metaphorical Network Visualisations

Whereas the artwork provides insight into how the journalist’s role in society is imagined, the second study we discuss here focuses on how the profession of journalism itself is conceptualised. In the current media landscape, there is an increased effort undertaken by journalists to defend and define both what journalism is and what it is for (Carlson and Lewis Citation2015). Studies that focus on such boundary work often aim to define where boundaries emerge in a changing journalistic landscape (see for instance Borger Citation2016), or how they are forged (see, for instance, Lewis Citation2012). Such research, however insightful, does not really give us insight into how such boundaries are experienced from a more individual and temporal point of view. Rather than suggesting that boundaries are monolithic and suggestive of a fixed understanding of where journalism ends and something else begins, we are interested in the individual experiences of boundaries in journalism.

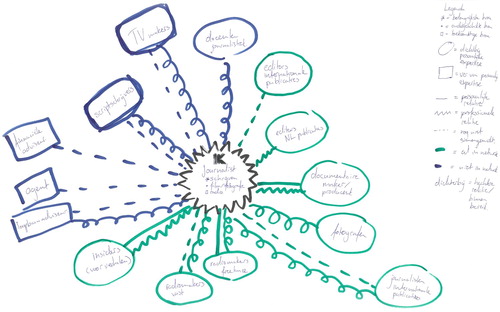

To this end we invited the participating journalists to visualise their own network, indicating with whom they collaborate in making journalism, representing who they deem within and who outside the field of journalism, thus identifying its boundaries. We asked them to reflect both on the people, disciplines and professional skill sets that they engage with in their current practice and those they would like to bring in in future work. To include an experiential perspective of these boundaries, we asked them to indicate the network graphically, using colours, boxes, lines, etc., but also, if desired, words to delineate and to denominate, including visualising the quality of the relationship to the people, disciplines and skills depicted (e.g., close collaboration or not as close as desired)—see for an example of these visualisations.

The collection of produced networks reflected multidimensional complexity in form, content and visual language. Rather than looking for patterns and commonalities between these visualisations, we are interested in the diversity of personal perspectives and experiences (and the ways in which these gain shape in the drawings). Such an artistic and sensory methodology allowed us to make sense of this multidimensionality and the fluid nature of the definition and boundaries of journalism as held by the participants. One of the interesting elements in the network map, and a theme we followed up on, was how journalists self-identified in their visualisation: how they describe themselves in the network. Participating journalists did not self-identify as simply “journalists”, if they use the term at all. If they did use the word journalist to signify themselves in the network map, they either added the medium they work with (e.g., a newspaper, magazine or social media), the skills they apply (e.g., photography or writing) or even a second profession (e.g., advisor or researcher). Others did not use the word “journalist” at all and used labels such as “digital nomad”, “storyteller” and “entrepreneur”. These ways of self-denoting helped us understand that we need to explore in more detail how participants identify and position themselves respective to the boundaries they draw, acknowledging that “journalism” does not exist as a fixed or homogenous category (see also Deuze and Witschge Citation2019). In what ways, then, can we research how journalists relate to surrounding professional fields and practices?

In our research, we used the concept of metaphor to access an immediate and embodied understanding of the journalists’ experience of the self, other actors, and their profession. As Lakoff and Johnson (Citation2003) argue, metaphors are not just words. They emerge from thought patterns—and in turn, structure them. We understand the world through embodied experience and interaction with the physical and socio-cultural world. Metaphors, therefore, allow us to gain rich insight into how journalists experience their profession and its boundaries, and to represent this in such a way that it reverberates the richness and variety of the experiences. To gain more insight into exactly these experiences, as well as further develop our thinking on how best to represent them, we followed up with in-depth interviews with four makers.

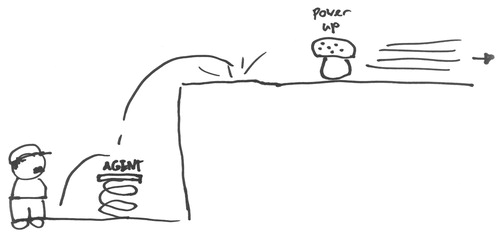

One of the interviewees developed a ludic metaphor to describe their relation to their profession and to other disciplines they interact with (see ). Although they never use the actual word “game”, they repeatedly mention how creating a story feels like “playing” to them and, furthermore, explains that they experience the different disciplines that they employ (writing, video and sound) as separate “playing fields” with their own sets of “rules”. These rules are attributed to an external authority, who akin to a referee might “catch” them on the foul play if they do not follow them. They struggle with the friction between the different playing fields and describes their switching between each discipline as “roleplaying”. The “journalism as a game” metaphor becomes particularly clear in their drawing of a scene from the video game Super Mario Bros, including both a springboard to jump higher and a mushroom that gives them superpowers. These objects represent the business agent, an actor, who they earlier referred to as someone who operates outside the field of journalism and helps them to access new opportunities. In their drawing, the opportunities that this agent provides them with are depicted as higher grounds that would be difficult to access without such a springboard or superpowers.

This example, which demonstrates what metaphor underlies the journalist’s relation to her profession and the disciplines they work with, displays how we can move beyond literal meanings of words used in in-depth interviews. It allows us to tap into everyday lived experiences and expressions of “meanings that otherwise would be ineffable” (Barone and Eisner Citation2012a, 1). Not only does such an analysis bring about rich descriptions that reveal personal meaning and association, but it also makes it easier to “read” the network visualisations in such a way that we can critically address their richness, multiplicity and complexity. A graphic representation can help us retain the evocative nature of metaphors, and as such we are currently working to translate the insights into another kind of representation that represents the complex, multidimensional experience of journalistic boundaries.

The Affective Nature of Journalistic Work: Resignation Letter

The last example we explore here focuses on the affective dimensions of journalistic work. It is clear that journalists are working under great pressure. Long working hours and low pay are quite common, even if generally accepted as an implicit norm in the field of journalism (see also Brouwers and Witschge Citation2019). Because these norms are implicit, it can be challenging to research whether and how journalists question them, and more broadly how they relate to the challenges they face professionally and personally in their work. To tease out the frustrations, anxieties, disappointments and tensions that journalists experience in their everyday work, we organised a workshop in which participants were invited to write a letter of resignation to their profession. Participants were asked what kind of motivations they would provide were they to quit the profession as a whole. Each journalist was given a piece of paper which was blank apart from the start that read “Dear Journalism, Herewith I resign. In this letter, I share my main reasons for my resignation. When I started working as a journalist … ”, a middle part “But now, after [blank space] years, I noticed that … ”; and a closing “Yours sincerely, a journalist”.

Individually, each of these handwritten letters provides unique and very lively insights into the challenges and developments of contemporary journalism, and showcases the affective ways in which journalists relate to their profession. Encouraged to freely write a hypothetical resignation letter, participants expressed their feelings, thoughts and concerns on their own terms. Collectively, these letters proved to provide highly powerful and moving access to current concerns in the field of journalism: Sofie Willemsen reorganised the fictitious resignation letters into one that empathically depict the sentiments expressed (for a full version of the letter, see: Witschge, Deuze, and Willemsen Citation2019). What is most striking is how this letter of less than 1000 words is able to make some of the practitioners’ key concerns come alive: financial instability and job insecurities, competitiveness, confirmation bias, a lack of proper research and click bait articles. As Witschge, Deuze, and Willemsen (Citation2019, 3) highlight, this method provides “an alternative, and we hope, engaging way to present the ways in which journalists experience their profession”.

Using creative writing methods, both the individual letters and the composite resignation letter allow us to evoke the affective dimensions of journalism, which provides an important point of access if we want to understand journalism as it is currently practiced (Deuze and Witschge Citation2019). As Stewart (Citation2007, 1–2) states, affects:

are the varied, surging capacities to affect and to be affected that give everyday life the quality of a continual motion of relations, scenes, contingencies, and emergences. They’re the things that happen. They happen in impulses, sensations, expectations, daydreams, encounters, and habits of relating.

Addressing the affective dimension through an arts-based research approach enables us to access and theorise journalists’ emotional ties to the profession and practice. Making room for experiencing, feeling and articulating one’s hopes, doubts, desires, motivations and frustrations, the letters of workshop participants point towards some shared doubts, hesitations and frustrations, such as the commercialisation of journalism. A striking example from the letters is how one of the journalists shared their experiences as a non-male and non-white practitioner, pointing towards a lack of diversity within the profession:

You kept telling me that my otherness is what you need, but that’s not enough. Words are not enough. I want to have the space to tell stories, including those you wouldn’t write and make yourself (…) Do you know what I find challenging? Insecurity. I don’t know what I can expect from you and whether I can make it as a journalist.

Ps. What didn’t help are all those times that my ideas were stolen. And all those test assignments that “I was allowed to” make. Being kept in suspense. For me it’s the last time!

I got caught in a chasm between form and content. It’s exhausting! That’s how I feel. And because I’m a human with feelings, because I’m blood and flesh, and because I’ve got a family with whom I want to spend time. And because I want to sleep, recover, rest. And because I want to acquire new powers, whatever they will be … . That’s why I resign.

Concluding Remarks: How to Deal with Open-Endedness in Research

In this article, we aimed to demonstrate how arts-based research methods provide alternative perspectives on a field that is in flux. It is important to note that we do not suggest that these methods need to be employed as stand-alone, nor do we necessarily advocate that all journalism researchers should work towards employing them. Rather, we see this approach as complementary to other methodologies, in particular given the specific difficulties we currently face in trying to “get journalism to hold still for a moment” so that “we might assess what has happened to it, as an occupational field and paradigmatic form during a period of seemingly unending and upending change” (Lewis and Zamith Citation2017, 111). In this light, arts-based research allows us to ask a number of crucial questions around the nature of our research practices, how we access this thing called “journalism” and how we aim to make an impact on the field. Arts-based research may help us raise and consider these questions. It, however, does not provide ready-made answers, and also comes with a range of questions itself: What is the nature of knowledge? How do we view our research subjects and the knowledge they have? And what methods allow us to gain access to the richness and diversity of journalistic practices, self-understanding and output?

Arts-based research is certainly not the only answer to address the methodological challenges that exist in the field (for a consideration of the need for new research strategies in journalism studies, see, for instance, Witschge Citation2016; Karlsson and Sjøvaag Citation2017). Creative methods, and in particular arts-based methods, though, have the potential to provide us with alternative viewpoints to our object of study. The application of these methods is not without challenges. In this section we highlight three issues that we have encountered and that we view as particularly relevant to consider in light of the theme of this special issue of Journalism Studies: (i) How to deal with the open-ended nature of arts-based research; (ii) How to (re)present findings while staying true to the nature of arts-based methods; (iii) Where does the role of the artist end and that of the academic start?

First, we have argued that one of the main features of arts-based research is its open-ended nature. Indeed, arts-based research is not “a quest for certainty” (Barone and Eisner Citation2012a, 1). However, this challenges many of the ways of researching and writing that are rather common in academia, including journalism studies. When doubt and uncertainty are central to a method, rather than a mere corollary, how does this manifest in the way we present our research? Arts-based research may indeed play “by rules that differ from those applied to more conventional (…) research” (Barone and Eisner Citation2012b, 101–102), but if the rules to which we are held are those of conventional research, how do we get to include results from arts-based research without moulding them into a shape that would entail reducing the presentation in such a way that it loses the exact qualities that it is meant to show: multiplicity, messiness and open-endedness? Barone and Eisner (Citation2012b, 102) suggest four criteria to critically appraise arts-based research, which may allow us to assess the quality of arts-based research while staying true to its nature: its “illuminating effect”, “generativity”, “incisiveness” and “generalisability”. Illumination is the extent to which research reveals something that was not noticed before. Generativity denotes the potential of research to generate more questions and broaden perspectives. Incisiveness refers to its capacity to address core issues. And generalisability questions the relevance of research beyond a particular case study. Some of these may look more familiar than others, and, ultimately, the qualitative appraisal of the application of arts-based research is as much a matter as the receptive predisposition of the intended audience (Barone and Eisner Citation2012b, 102–103).

This leads us to our second question: How do we then reach and reach out to this audience? Who is the audience of arts-based research? Does this differ from other academic research output? And perhaps most importantly, how do we disseminate the “results” while staying true to the open-ended nature of arts-based approaches. “Messy data spills over in messy analysis and in messy dissemination” (Brown Citation2019), but can we leave our audiences with a mess, or do we find ways to tidy it up and guide our audiences in certain directions? To this end, we have found the viewpoint that we “invite” our audiences towards interpretation very helpful. (Re)presenting our findings as an imaginative invitation, we respect the open-ended and shared nature of knowledge. Imaginative invitations, as conceptualised by Shields and Penn (Citation2016, 9), mean that we ask “the viewer/audience to participate in the interpretive processes, rather than crafting definitive representative products”. The imaginative invitation is then an “open request to engage in the action of forming new ideas”, encouraging “the reader to question and seek out their own understandings” (Shields and Penn Citation2016, 10). (Re)presentation in this view is a process that invites multiple interpretations, acknowledging that experience, context, and reference all matter. If we want to show the processual nature of journalism—meaning that it is not a fixed stable phenomenon, but constantly becoming (Deuze and Witschge Citation2019)—we cannot reduce the messy, complex and multiple experiences uncovered by our research to singular explanations. Precisely by viewing the artistic expression that is at the basis or the product of arts-based research as “an affective site of individual experience” (Shields and Penn Citation2016, 9), we are able to expand our perspective of journalism.

Last, our experiences with this approach have left us with the question of what the role of the academic is: Where does the role of the artist end and that of the academic start? And are installations, artworks and media productions valid academic representations by themselves? This remains a site of contention, even within our team of researchers, which includes those with an artistic background: what can we legitimately produce? And related: How open can open-ended be? Do we need to layer the work with further analysis and reflection in the form that is more “common” to academia? How far can we push our experientialist research approaches? Do we view arts-based methods as complementary to the textual presentation of findings? Or are experiences, complexity and multiplicity best represented through equally multiple, complex and experiential translations? We hope that the reader views this article as an open invitation to explore these questions with us, reflecting on the opportunities and limitations of arts-based research in the critical interrogation of current journalistic practices.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Tamilla Ziyatdinova for her detailed reading and editing of the manuscript and the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

References

- Anderson, C. 2011. “Blowing Up the Newsroom: Ethnography in an Age of Distributed Journalism.” In Making Online News, edited by D. Domingo and C. A. Paterson, 151–160. New York: Peter Lang.

- Archetti, C. 2017. “Journalism, Practice and … Poetry: Or the Unexpected Effects of Creative Writing on Journalism Research.” Journalism Studies 18 (9): 1106–1127. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2015.1111773

- Barone, T., and E. Eisner. 2012a. Arts Based Research. London: Sage.

- Barone, T., and E. Eisner. 2012b. “Arts-based Educational Research.” In Handbook of Complementary Methods in Education Research, edited by J. Green, G. Camilli, and P. Elmore, 95–109. London: Taylor and Francis.

- Borgdorff, H. 2012. The Conflict of the Faculties. Perspectives on Artistic Research and Academia. Leiden: Leiden University Press.

- Borger, M. 2016. Participatory Journalism: Rethinking Journalism in the Digital Age? Amsterdam: Uitgeverij BoxPress.

- Brosius, J. P. 2006. “Common Ground Between Anthropology and Conservation Biology.” Conservation Biology 20 (3): 683–685. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00463.x

- Brouwers, A., and T. Witschge. 2019. “‘It Never Stops’: The Implicit Norm of Working Long Hours in Entrepreneurial Journalism.” In Making Media, edited by M. Deuze, and M. Prenger, 441–451. Amsterdam: AUP.

- Brown, N. 2019. “Emerging Researcher Perspectives: Finding Your People: My Challenge of Developing a Creative Research Methods Network.” In: International Journal of Qualitative Methods 18: 1–3.

- Cahnmann, M. 2006. “Reading, Living, and Writing Bilingual Poetry as ScholARTistry in the Language Arts Classroom.” In: Language Arts 83 (4): 342–352.

- Cahnmann-Taylor, M. 2017. “Arts-based Approaches to Inquiry in Language Education.” In Research Methods in Language and Education, 353–365, edited by K. King, Y. Lai, and S. May. 3rd ed. Cham: Springer Nature.

- Carlson, M., and S. C. Lewis. 2015. Boundaries of Journalism: Professionalism, Practices and Participation. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Christians, G., T. Glasser, D. McQuail, K. Nordenstreng, and R. A. White. 2009. Normative Theories of the Media: Journalism in Democratic Societies. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Costera Meijer, I. 2016. “Practicing Audience-Centered Journalism Research.” In The Sage Handbook of Digital Journalism, edited by T. Witschge, C. W. Anderson, D. Domingo, and A. Hermida, 546–561. London: Sage.

- Deuze, M., and T. Witschge. 2019. Beyond Journalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Eagleton, T. 1990. The Ideology of the Aesthetic. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Finley, S. 2005. “Arts Based Inquiry: Performing Revolutionary Pedagogy.” In Sage Handbook of Qualitative Inquiry, edited by N. Denzin and Y. Lincoln, 681–694. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Fisher, C. 2015. “Managing Conflict of Interest.” Journalism Practice 10 (3): 373–386. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2015.1027786

- Gravengaard, G. 2012. “The Metaphors Journalists Live By: Journalists’ Conceptualisations of Newswork.” Journalism 13 (8): 1064–1082. doi: 10.1177/1464884911433251

- Gyldensted, C. 2015. From Mirrors to Movers: Five Elements of Constructive Journalism. Charleston, SC: GGroup Publishing.

- Haywood-Rolling, J. 2010. “A Paradigm Analysis of Arts-based Research and Implications for Education.” A Journal of Issues and Research 51–2: 102–114.

- Heinrich, A. 2014. Network Journalism: Journalistic Practice in Interactive Spheres. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hunter, A. 2015. “Crowdfunding Independent and Freelance Journalism: Negotiating Journalistic Norms of Autonomy and Objectivity.” New Media & Society 17 (2): 272–288. doi: 10.1177/1461444814558915

- Ingold, T. 2018. Anthropology: Why It Matters. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Karlsson, M., and H. Sjøvaag. 2017. Rethinking Research Methods in an Age of Digital Journalism. London: Routledge.

- Kasem, A., M. J. F. van Waes, and K. C. M. E. Wannet. 2015. “Anders nog nieuws: Scenario’s voor de toekomst van de journalistiek [What’s New(s)? Scenarios for the Future of Journalism].” In Stimuleringsfonds Voor de Journalistiek. www.journalism2025.com.

- Knowles, G. J., and A. L. Cole. 2008. Handbook of the Arts in Qualitative Research. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Lakoff, G., and M. Johnson. 2003. Metaphors We Live by. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Leavy, P. 2015. Method Meets Art. Arts-based Research Practice. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Lewis, S. C. 2012. “The Tension Between Professional Control and Open Participation: Journalism and Its Boundaries.” Information, Communication & Society 15 (6): 836–866. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2012.674150

- Lewis, S. C., and R. Zamith. 2017. “On the Worlds of Journalism.” In Remaking the News: Essays on the Future of Journalism Scholarship in the Digital Age, edited by P. J. Boczkowski and C. W. Anderson, 111–128. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Nayak, A., and R. Chia. 2011. “Thinking Becoming and Emergence: Process Philosophy and Organization Studies.” In Philosophy and Organization Theory [Research in the Sociology of Organizations], edited by H. Tsoukas and R. Chia 32: 281–309. Bingley: Emerald Group.

- Peters, C., and T. Witschge. 2014. “From Grand Narratives of Democracy to Small Expectations of Participation.” Journalism Practice 9 (1): 19–34. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2014.928455

- Robinson, S., and M. Metzler. 2016. “Ethnography of Digital News Production.” In Sage Handbook of Digital Journalism, edited by T. Witschge, C. W. Anderson, D. Domingo, and A. Hermida, 447–459. London: Sage.

- Shields, S., and L. Penn. 2016. “Do You Want to Watch a Movie? Conceptualizing Video in Qualitative Research as an Imaginative Invitation.” Art/Research International: A Transdisciplinary Journal 1 (1): 5–23. doi: 10.18432/R2VC75

- Sniadecki, J. P. 2014. “Chaiqian/Demolition: Reflections on Media Practice.” Visual Anthropology Review 30 (1): 23–37. doi: 10.1111/var.12028

- Springgay, S., R. Irwin, and S. Kind. 2005. “A/r/Tography a Living Inquiry Through Art and Text.” Qualitative Inquiry 11 (6): 897–912. doi: 10.1177/1077800405280696

- Stewart, K. 2007. Ordinary Affects. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Vinken, H., and T. IJdens. 2013. Freelance Journalisten, Schrijvers en Fotografen: Tarieven en auteursrechten, onderhandelingen en toekomstverwachtingen. Tilburg.

- Vos, T. P., and J. B. Singer. 2016. “Media Discourse About Entrepreneurial Journalism.” Journalism Practice 10 (2): 143–159. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2015.1124730

- Wagemans, A., and T. Witschge. 2019. “Examining Innovation as Process: Action Research in Journalism Studies.” Convergence 25 (2): 209–244. doi: 10.1177/1354856519834880

- Wagemans, A., T. Witschge, and F. Harbers. 2018. “Impact as Driving Force of Journalistic and Social Change.” Journalism 20 (4): 552–567. doi: 10.1177/1464884918770538

- Wahl-Jorgensen, K. 2009. “News Production, Ethnography, and Power: On the Challenges of Newsroom-Centricity.” In Journalism and Anthropology, edited by S. E. Bird. Bloomington, 21–35. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- White, D. 2017. “Affect: An Introduction.” Cultural Anthropology 32 (2): 175–180. doi: 10.14506/ca32.2.01

- Witschge, T. 2016. “Part IV: Research Strategies.” In Sage Handbook of Digital Journalism, edited by T. Witschge, C. W. Anderson, D. Domingo, and A. Hermida, 443–446. London: Sage.

- Witschge, T., C. W. Anderson, D. Domingo, and A. Hermida. 2016. Sage Handbook of Digital Journalism. London: Sage.

- Witschge, T., C. W. Anderson, D. Domingo, and A. Hermida. 2019. “Dealing with the Mess (We Made): Hybridity, Normativity and Complexity in Journalism.” Journalism 20 (5): 651–659. doi: 10.1177/1464884918760669

- Witschge, T., M. Deuze, and S. Willemsen. 2019. “Creativity in (Digital) Journalism Studies: Broadening Our Perspective on Journalism Practice.” Digital Journalism 7 (7): 972–979. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21670811.2019.1609373.

- Witschge, T., and F. Harbers. 2018. “Journalism as Practice.” In Handbooks of Communication Science: Journalism, edited by T. Vos, 101–119. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

- Zenker, O. 2014. “Writing Culture.” In Oxford Bibliographies . http://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199766567/obo-9780199766567-0030.xml.