ABSTRACT

During recent years, worries about fake news have been a salient aspect of mediated debates. However, the ubiquitous and fuzzy usage of the term in news reporting has led more and more scholars and other public actors to call for its abandonment in public discourse altogether. Given this status as a controversial but arguably effective buzzword in news coverage, we know surprisingly little about exactly how journalists use the term in their reporting. By means of a quantitative content analysis, this study offers empirical evidence on this question. Using the case of Austria, where discussions around fake news have been ubiquitous during recent years, we analyzed all news articles mentioning the term “fake news” in major daily newspapers between 2015 and 2018 (N = 2,967). We find that journalistic reporting on fake news shifts over time from mainly describing the threat of disinformation online, to a more normalized and broad usage of the term in relation to attacks on legacy news media. Furthermore, news reports increasingly use the term in contexts completely unrelated to disinformation or media attacks. In using the term this way, journalists arguably contribute not only to term salience but also to a questionable normalization process.

The term “fake news” is a global buzzword—used frequently by some, loathed by others (e.g., McNair Citation2017). While originally used as a niche term by communication scholars to describe formats of political satire (e.g., Baym Citation2005), it has since 2016 come to characterize a variety of phenomena related to questions of truth and factuality in journalism and political communication. In response to this new scope of the term's usage, scholars have begun to design conceptual and operational definitions of the term “fake news” (e.g., Tandoc, Lim, and Ling Citation2018). These definitions suggest that, essentially, the term stands for two major challenges to modern democracies. On the one hand, it is used to describe disinformation that masquerades as news articles and is often spread online (e.g., Lazer et al. Citation2018; Tandoc, Lim, and Ling Citation2018). On the other hand, an increasing number of political actors have begun to use the term to discredit legacy news media (e.g., Lischka Citation2019), with the potential to decrease citizens’ levels of media trust (e.g., Guess, Nyhan, and Reifler Citation2017). Egelhofer and Lecheler (Citation2019), therefore, suggest distinguishing between fake news as a genre of disinformation and the fake news label as a political instrument to delegitimize journalism (but see also McNair Citation2017).

While our scholarly view of the causes and consequences of fake news has become clearer, we lack empirical evidence on how the debate around fake news manifests itself in social reality. At this moment, all we know is that there is rising criticism regarding the frequent and fuzzy public use of the term (e.g., Habgood-Coote Citation2019), seen as problematic because the overuse of the term by news media and other public actors may already render it more important in people's minds than it actually is. Furthermore, increased salience alone might lead to a normalization of the term, rendering its meaning equal to anything that is false. Trivializing a term that clearly has a negative connotation could further encourage its use “as an unreflected designation for the media”.

Before we can move to understand these effects, we must first collect empirical evidence on the nature of the fake news debate itself. Journalists face a dilemma when it comes to using the term “fake news” in their reporting. While some might be aware of the worries about the term (e.g., Badshah Citation2018), it also functions as an effective cue in news reporting to increase audience interest and engagement. However, so far there is only limited evidence of how journalists actually use the term in their reporting. We study the case of Austria, a country where fake news debates have been frequent, and where a number of political actors have used the term in political discourse. Thereby, we provide a European perspective on the journalistic use of the fake news terminology. By means of a content analysis of all fake news-related articles in eight major newspapers, we show how journalistic use of the term has developed during recent years. Additionally, we investigate how fuzzy or concrete journalists’ use of the term is in describing disinformation threats and media-critical debates where the term is used to attack journalism. By looking into fake news as a multidimensional concept, we (a) test how applicable theoretical distinctions of different fake news dimensions are in public discourse and (b) provide first answers to the question of whether journalists are perhaps normalizing a term that is used against them by critical political elites.

Fake News: One Term, Three Concepts

The term “fake news” has been described as “problematic,” “ambiguous,” “inadequate and misleading,” and “unhelpful” (Albright Citation2017; DiFranzo and Gloria-Garcia Citation2017; HLEG Citation2018; Wardle Citation2017). This is, in large part, related to the fact that the term does not have one fixed meaning (Habgood-Coote Citation2019). However, by and large, research on fake news refers to one of three contexts in which the term is used: First, fake news as a genre of disinformation online; second, the weaponization of the term by critical political actors as a label to delegitimize news media (Egelhofer and Lecheler Citation2019); and third, “fake news” is also seen as an empty buzzword, simply used to describe something as false or bad (e.g., Habgood-Coote Citation2019).

The Fake News Genre

While originally the term “fake news” was used to describe formats of political satire (e.g., Baym Citation2005), during the 2016 US presidential elections, scholars and journalists adapted it to characterize made-up news articles (e.g., Mourão and Robertson Citation2019; Silverman Citation2016), such as for the infamous “pizzagate” story. Since then, these stories have spiraled into a salient public debate, in which citizens, politicians, journalists, and scholars have shared their concerns about the possibly detrimental influence of fake news on political events. Also since 2016, a growing number of studies have offered theoretical clarifications and definitional characteristics of the concept, mostly characterizing it as a form of disinformation (e.g., Lazer et al. Citation2018; Tandoc, Lim, and Ling Citation2018). Disinformation—in contrast to misinformation—is “false, inaccurate, or misleading information” that is created intentionally (HLEG Citation2018, 10). This means that fake news consists of factually incorrect information that is created intentionally, distinguishing it from inaccurate information that is generated unknowingly or by mistake.Footnote1 Furthermore, fake news is characterized by its resemblance to news (e.g., Egelhofer and Lecheler Citation2019; Lazer et al. Citation2018; McNair Citation2017; Tandoc, Lim, and Ling Citation2018).

The Fake News Label

However, the term “fake news” has also become important when studying media criticism. US President Donald Trump successfully redirected a public debate about disinformation and democracies by labeling legacy outlets as “fake news.” This was effective, as the term already had an inherent connotation as a potentially dangerous development in modern democracies. By using the term against news outlets, Trump (and with him several other politicians in a number of countries) were thus “borrowing some of the phrase's original power” (Kurtzleben Citation2017, para. 17). As such, the fake news label is used by political leaders to “muzzle the media on the pretext of fighting false information” and thereby defending censorship (RSF Citation2017, para. 1). These actors are also almost always labeled as populists, as one of the core attributes of populism is anti-elitism discourse, which can be directed at political elites but also against the media (e.g., De Vreese Citation2017; Jagers and Walgrave Citation2007; Krämer Citation2018). For example, in many European countries, such as Austria, France, Germany, and the Netherlands, verbal attacks on the media by populist politicians are increasing (RSF Citation2018a).

The Empty Buzzword

Beyond these two meanings of the term, however, we can observe a third trend: Increasingly, the “fake news” term has become a way of stating that something is incorrect or debatable. It has become “elastic to a fault” (Mourão and Robertson Citation2019, 1). For example, some scholars are using the term as a catchy academic title element in articles that are unconnected to disinformation, media criticism, or communication in general (e.g., “Is Successful Brain Training Fake News?” Fitzgerald Citation2017). Others use it as a means to describe the current time period (e.g., “the ‘Fake News’ Era”; Berghel Citation2017), where facts increasingly seem to be contested, relating to terms like “post-truth” and “alternative facts.” Therefore, the term “fake news” has become part of a larger debate about epistemic instability. In this context, some scholars suggest that, by now, fake news has become “a catch-all for bad information” (Habgood-Coote Citation2019, 8). This is why scholars have also described it as a “fluid descriptor” (Carlson Citation2018, 6) and a “floating signifier” (Farkas and Schou Citation2018, 300), which is used differently in different contexts. Relating to this, a recent content analysis of the Twitter discourse surrounding “fake news” shows that it is a highly politicized term that is mainly used to discredit statements by the opposition as false (Brummette et al. Citation2018). Consequently, the term has become so popular that it now is a normal set of words to describe falsity in general, regardless of intentionality and journalistic design.

In sum, the term “fake news” has thus been studied in the context of (1) disinformation and (2) media criticism, but also to simply describe (3) a larger development of increasing insecurity about truth in modern societies. Research on these three meanings seems to suggest that journalistic attention to a “fake news crisis” has at least in part contributed to this development. In the following, we describe why precise knowledge of how journalists might have done so is relevant.

Why Could Using the Term “Fake News” in Journalistic Reporting Be Problematic?

We argue that there are two main reasons why understanding how journalists give meaning to the term “fake news” is relevant for journalism research: First, as discussed before, the term lacks a “stable public meaning” (Habgood-Coote Citation2019, 2). Thus, when described as a threat to democratic societies in media coverage, it is left to citizens to define what exactly constitutes this threat. Second, using the term in mediated debates may have contributed toward weaponizing the term for critical political actors, who use the fake news label to delegitimize journalism as a democratic institution (e.g., Lakoff Citation2018).

When a new term enters public discourse, it is not unusual that its use and meaning are debated. For example, the concept of “populism” has long been characterized as ambiguous due to a lack of consensus regarding what exactly is described by the term (e.g., Reinemann et al. Citation2016). This ambiguity can be found in academic research, where scholars use it differently, but even more so in journalistic coverage. For instance, a content analysis of British media coverage of the terms “populism” and “populist” shows that these terms are used very imprecisely by journalists, who often apply them to label political enemies. The media are thereby describing a variety of unrelated actors as populists (e.g., Bale, van Kessel, and Taggart Citation2011). This is seen as problematic, as inconsistencies between scientific and vernacular understandings of concepts can impede dialogue between science and society and thereby hamper social science's impact and contribution for citizens (e.g., Bale, van Kessel, and Taggart Citation2011; Reinemann et al. Citation2016).

In the same line, fuzzy journalistic usage of the term “fake news” to describe a variety of concepts that are only loosely connected to falsehood and inaccuracy will simply make the term usable in a variety of situations, thereby inflating its salience. This means that fake news might be perceived as a disproportionately important problem by audiences. For example, polls showed that in 2019, US citizens ranked fake news as a bigger threat to their country than climate change, racism, or terrorism (Mitchell et al. Citation2019). Scientific studies, however, suggest that the actual impact of fake news in terms of the share of citizens exposed to intentionally created pseudojournalistic stories is relatively small, compared to the individuals who visit established news sites (Fletcher et al. Citation2018; Nelson and Taneja Citation2018; see also Grinberg et al. Citation2019).

More importantly, however, the term is potentially dangerous for journalism as a democratic institution. Starting with President Trump in the US, the term has been instrumentalized by politicians around the world to delegitimize critical reporting, turning it into a “frontal attack on traditional core values of journalistic practice” (Farkas and Schou Citation2018, 308). Therefore, a growing number of public actors call for its abandonment in public discourse (e.g., Badshah Citation2018; HLEG Citation2018; Habgood-Coote Citation2019; Wardle and Derakhshan Citation2017).

This fake news label is dangerous, as elite media criticism has the potential to influence citizens’ media perceptions (e.g., Ladd Citation2012). Importantly, there is initial evidence suggesting that the mere presence of the term in news articles (Guess, Nyhan, and Reifler Citation2017) or in elite discourse on Twitter (Van Duyn and Collier Citation2019) is sufficient to lower media trust for (some) citizens. Therefore, by repeating the term “fake news” constantly, the press might be complicit in turning it into an effective weapon that is used against journalism (Lakoff Citation2018). Relating to this, Watts and colleagues (Citation1999) suggested that media bias perceptions of many US citizens might have been a consequence of the news media's extensive coverage of conservative elites’ media bias claims.

In sum, all of the above suggests the crucial need to understand how journalists use the term “fake news” in their coverage. This seems of particular relevance in times where skepticism appears to be the status quo for many citizens when considering the trustworthiness of news (Carlson Citation2017).

Observing “Fake News” as a Three-Dimensional Concept in the News

We thus argue that there is a need to understand how journalists use the term in their reporting. More specifically, we consider it relevant to investigate which of the three contexts fake news is mentioned in is most visibly discussed and how this might have changed over time.

When thinking about how journalists cover fake news, we wonder not only how visible the term is in terms of absolute numbers, but also how commonly journalists make a connection between the core understanding of the term as disinformation and other, more watered-down or even unrelated understandings of the term. Recent research on audiences shows that the public's understanding of the term seems to vary from “poor journalism” to propaganda, (native) advertising, and more (Nielsen and Graves Citation2017). This might also be a result of the press using the term too freely in their reporting (Funke Citation2018)—but empirical data on this assumption is missing. One exception to this is presented by Tandoc, Jenkins, and Craft (Citation2019), who analyzed US-newspaper editorials on fake news from 2016 to 2017. Their results showed that there were hardly any efforts to offer explicit definitions of the concept. In sum, we thus suggest observing the visibility of the term and its definitions over time, starting with the first journalistic discussions of the term during the 2016 US presidential election campaign. Therefore, our first research question reads:

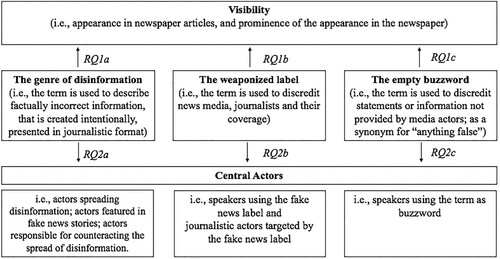

RQ1: In which of the following contexts do journalists use the term “fake news” most visibly: (a) the genre of disinformation, (b) the weaponized label, (c) the empty buzzword.

While these studies offered crucial first insights into who the central actors in journalistic discussions of fake news are, they must be complemented with a broader overview of the use of the term over time. What is more, we lack any knowledge on the actors that are facilitating the usage of the term in contexts unrelated to disinformation or media criticism (i.e., the empty concept). Based on the above, we pose the following research question (see also ):

RQ2: Who are the central actors in media coverage of fake news relating to (a) the genre of disinformation, (b) the weaponized label, and (c) the empty buzzword?

Method

The Austrian Case

The studies discussed above focused on the United States and leave much unexplained in other contexts where fake news has become an equally salient issue (e.g., Newman et al. Citation2018). This is why Tandoc, Jenkins, and Craft (Citation2019) called for studies on discourses on fake news in non-US media. For example, the central actors might differ here. We do know that in the United States, fake news stories have mostly featured political actors, especially the 2016 presidential candidates (e.g., Allcott and Gentzkow Citation2017; Mourão and Robertson Citation2019). However, in German-speaking countries, fake news has more often featured immigrants (Humprecht Citation2019). What is more, our knowledge about central actors in the weaponization of the term is restricted to President Trump, while scholars and anecdotal evidence suggest that the term is used by other political leaders as well (e.g., Wardle and Derakhshan Citation2017). Especially in German-speaking countries, we can witness an increase in right-wing populist media attacks, some referring to the fake news label and related terms (e.g., “lying press”).

Therefore, following the call of Tandoc and colleagues, we analyze news coverage on fake news in Austria. Fake news is increasingly discussed as a possible threat to democracy in Austria. For example, around half of Austrian voters feared that fake news would influence the 2017 national election outcome (Wagner et al. Citation2018). During the election campaign, there was an instance of dirty campaigning (where false-flag Facebook pages spread disinformation about political candidates) that was prominently reported under the fake news umbrella (e.g., Die Presse Citation2018a).

The use of the fake news label against the news media is also worrying Austrian citizens—even more so (56%) compared to the US public (46%) (Newman et al. Citation2018, 38–39). These worries might be related to a number of instances where Austrian politicians have used the fake news label to attack critical news coverage. For example, the then leader of the far-right Freedom Party (FPÖ), and former Vice-Chancellor Heinz-Christian Strache, used it to dismiss critical media reports (Die Presse Citation2018b) and to attack the public broadcaster ORF (Reuters Citation2018). The FPÖ is in general highly critical of the ORF and is publicly demanding to abolish license fees, which has caused international observers to express their worries about the state of press freedom in Austria (e.g., Newman et al. Citation2019; RSF Citation2018b).

Based on the above, we suggest that the Austrian context is a most likely case to find a lively journalistic debate on fake news outside the US context—not only relating to the US case but also to Austrian politics.

Study Sample

To answer the research questions, we analyzed all articles published in eight Austrian daily newspapersFootnote2 that mentioned the term “fake news” over the course of three and a half years, between 1 January 2015 and 1 May 2018 (N = 2,967). We focused on newspaper coverage, as it plays a crucial role in Austria. The Austrian media system fits the democratic-corporatist model and is characterized by high newspaper circulation (comparable to Germany and Switzerland, for example) (Eberl, Boomgaarden, and Wagner Citation2017; Hallin and Mancini Citation2004). Focusing on newspaper coverage enabled us to investigate the usage of the term not only by journalists but also by politicians and other actors. The time period was chosen to cover the genesis of the usage of the term “fake news” as well as its evolution over time. The sample consisted of national daily news outlets that have the widest reach in Austria (Media Analyse Citation2015–2018; for more information on circulation figures of each outlet, please see online Appendix A). The sample was varied in terms of ideological leaning and media genre, containing newspapers that are perceived to be more left-leaning (e.g., Der Standard) and more right-leaning (e.g., Die Presse), as well as broadsheets (Der Standard, Die Presse, Salzburger Nachrichten), tabloid (Kronen Zeitung, Österreich, Heute), and mid-range newspapers (Kurier, Kleine Zeitung).

Coding Procedure and Variables

For the manual content analysis, three coders (i.e., two authors and a graduate student) coded the content of each newspaper article that used the term “fake news,” using the online content analysis tool AmCAT. For each article coders read the title, the first paragraph, and all other paragraphs in which the term appeared. Coder training featured an initial discussion of the codebook and multiple rounds of coding, discussing and evaluating the codings until all disagreements were resolved and acceptable intercoder reliability was achieved.Footnote3

Fake News Concepts

The first set of variables were dichotomously coded and considered if the article used “fake news” in the context of the genre of disinformation, relating to fake news label attacks, or used it as an empty buzzword.

Visibility

To answer the research question about the visibility of the term “fake news” (RQ1), we automatically analyzed how often the term appeared in articles, and whether it was used in the title or the text body. All other variables were coded manually.

Definitions

To understand how visible academic definitions of fake news were in the context of disinformation (RQ1), we coded whether the article provided definitional information when using the term (in articles relating to the fake news genre). We based our definitional categories on characteristics derived from previous studies that have defined fake news (e.g., Egelhofer and Lecheler Citation2019; Lazer et al. Citation2018; Tandoc, Lim, and Ling Citation2018). Specifically, we distinguished three categories: (a) false information (i.e., the article mentioned that fake news consists of wrongful information), (b) intentionality (i.e., the article mentioned that fake news is created and/or spread deliberately), and (c) pseudojournalistic design (i.e., fake news was described as something that looks like news). All categories were coded as a dichotomous variable, distinguishing whether the characteristic was mentioned or not.

Actors

For fake news as a genre of disinformation, we distinguished three categories of central actors: actors that were reported (a) to spread disinformation, (b) to be featured in fake news stories, or (c) to be responsible for counteracting the spread of disinformation. For the fake news label we distinguished (a) actors that were reported to be using the fake news label and (b) journalistic actors against whom the fake news label was used. Actors in the empty concept were all actors that used the term to simply state that something was incorrect, or as a synonym for lies or falsehood. All actors were coded as an open text field, which was harmonized after coding was finalized.Footnote4 We mostly distinguished between political actors (e.g., from Austria, the United States, and Russia) and unpolitical and private actors. However, we also characterized one major group of political actors as populist by relying on previous studies that categorized parties and politicians as populist (e.g., Rooduijn et al. Citation2019; Wettstein et al. Citation2019). Accordingly, we characterized the following actors that appeared in our data set as populist: Donald Trump and his government, the Austrian party FPÖ and its splinter party the Alliance for the Future of Austria (BZÖ), the Austrian government between the People's Party (ÖVP) and the FPÖ, the German Alternative for Germany (AfD), the French Front National, the Italian Five Star Movement and Forza Italia, the Hungarian party Fidesz, and all these parties’ members.

Intercoder Reliability

Intercoder reliability scores were calculated based on a sample of 200 articles in total (i.e., approximately 7% of the sample). Three separate reliability codings were conducted: one before, one during, and one after the coding of the data. Krippendorff's α ranged from 0.70 to 0.84, except for one variable (i.e., actors reported to spread fake news), where Krippendorff's α was 0.52. However, this variable had a very skewed distribution, in which case the Krippendorff's alpha might be too conservative (e.g., Lombard, Snyder-Duch, and Bracken Citation2002). Therefore, we additionally calculated Scott's Pi as well as Brennan and Prediger's kappa, measures that are suggested to be more robust for assessing agreement of variables that are not well distributed (Quarfoot and Levine Citation2016). These showed acceptable scores for all variables (Scott's Pi ranged from 0.70 to 0.83; Brennan and Prediger's κ ranged from 0.78 to 0.94; percentage agreement ranged from 0.86 to 0.94). All coefficients are reported in online Appendix C.

Results

Visibility

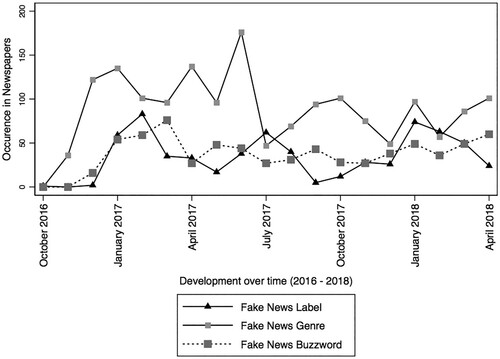

Of all 2,967 articles, 57% (1,678) considered fake news as a genre of disinformation, 22% (653) referred to the weaponized fake news label, and about 43% (713) used the empty buzzword.Footnote5, Footnote6 To understand which of the three concepts of fake news was most visible in news coverage (RQ1), we first examined how many news articles on each concept were produced over time. Second, we investigated how often the term was used in the whole article as well as whether it was used in the title or not in order to understand how central the concept was in the article.

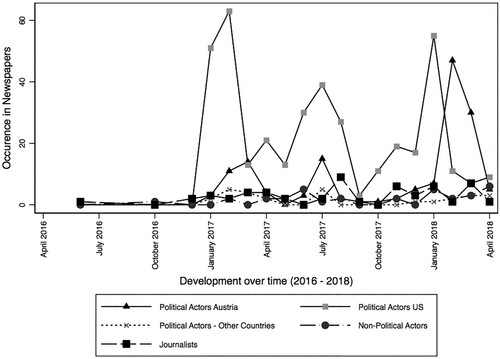

Before October 2016, there were no articles by Austrian newspapers on fake news. This finding is in line with authors who have suggested that the 2016 US presidential election was the origin of the fake news debate (e.g., Farkas and Schou Citation2018; McNair Citation2017). As seen in , news coverage on fake news started out focusing on disinformation. Articles on attacks on journalism (and false information in general) emerged a few months later, between December 2016 and January 2017. This finding is in line with a content analysis of Donald Trump's Twitter discourse, which showed that he started weaponizing the fake news term after he was elected in December 2016 (Meeks Citation2019). While the coverage of fake news as a genre of disinformation slightly decreased over time, over the whole time span there was steadily more journalistic discussion of this original concept, compared to the fake news label and the empty buzzword.

Next we looked at how often the term was used in the whole article as well as in the title to understand how central the concept was in the article. About 15% of all articles used the term “fake news” in their title, most often referring to the fake news genre (). Furthermore, most articles referred only once to the term. However, articles on the genre used the term comparatively more often.

Table 1. Number of “fake news” mentions in title and text body.

Relating to the original concept, we further investigated whether journalists defined the fake news term when they used it and which of the scholarly characteristics was most visible. Of all articles that used fake news in the context of disinformation, about 44% (732 articles) provided definitional information for it. Of these, most articles mentioned that fake news consists of false information (44.2%). Journalists used the characteristics journalistic design (28.5%) and intentionality (27.4%) almost equally often when characterizing fake news.

In sum, while news coverage connected to the weaponized label and the empty buzzword increased over time, the term still was most visible in the news on the original context of disinformation, where journalists mostly defined it as false information.

Central Actors

Turning to central actors in the journalistic coverage of fake news, we distinguished three actor categories for the fake news genre of disinformation. Articles could feature actors that were said to be (a) spreading fake news, (b) featured in fake news, or (c) responsible for counteracting fake news.

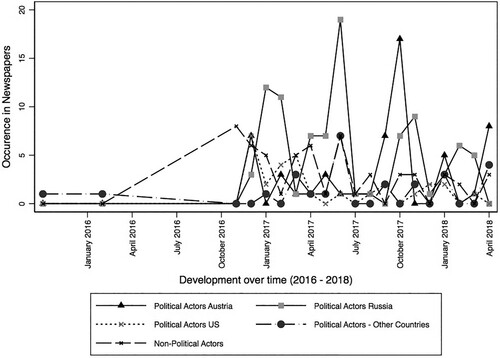

In 15.6% of the articles on the fake news genre, actors who were spreading fake news were mentioned. visualizes all mentioned actors over time. We can see that Russian actors (i.e., mostly Vladimir Putin and his government) were most prominently mentioned (35.6%). In the beginning private actors were also often reported (14.9%). Here, articles most often related to young Macedonian citizens who were found to be spreading pro-Trump fake news for financial reasons (e.g., Silverman and Alexander Citation2016). Interestingly, compared to US actors (11%), Austrian actors (21.5%) were reported not only more often but also earlier, at the beginning of journalistic coverage—suggesting that the topic of disinformation was relevant early on in the Austrian context. Moreover, considering Austrian actors, we can see a peak in October 2017, where the legislative elections took place—highlighting that fake news as disinformation appeared to be a particularly salient topic in election contexts. Political actors from other countries (e.g., France, Hungary, the UK, Italy, and Germany) and nonpolitical actors (e.g., NGOs, websites, academics) were reported less often (in 10% and 7% of the cases, respectively).

Turning to actors that were reported to be featured in fake news stories (in 16.4% of news articles on the genre context), we can see that political actors from the United States (22.6%) dominated news coverage in the beginning. However, later on, political actors from other countries (28.3%—mainly actors from France, Hungary, Russia, the UK, and Germany), as well as nonpolitical actors (36.7%—including refugees and immigrants, NGOs, prominent actors from culture and sports), were discussed much more. Political actors from Austria (12.4%) were least mentioned in this context ().

In sum, fears of interference by Russia and other fake news creators in the 2016 election was highly discussed in Austrian news coverage. However, the fake news (genre) discussion very quickly spread to other political and election contexts.

In 35% of the articles on the fake news genre context, counteracting actors were discussed. Similarly to the qualitative studies mentioned above (Carlson Citation2018; Farkas and Schou Citation2018; Tandoc, Jenkins, and Craft Citation2019), our results showed that when it came to counteracting fake news, responsible actors were mostly from politics (25%), social media (26.5%), and journalism (25.1%). To a certain degree, citizens’ levels of media literacy (12.9%) and efforts of fact-checking organizations (10.5%) were also part of discussions on counteracting fake news’ effects.

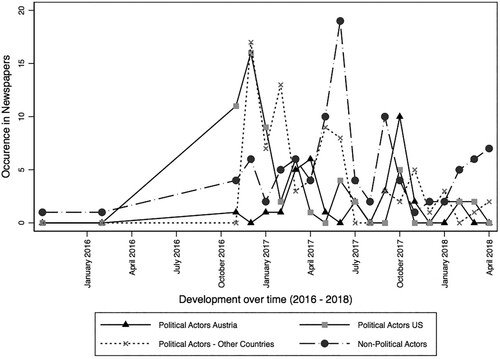

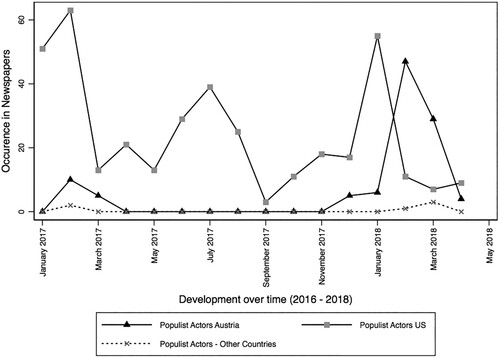

Central actors in the weaponized context were (a) actors said to be using the fake news label against (b) journalistic actors. As seen in , political actors were again prevalent, especially actors from the United States (59.6%). Here, most articles related to Donald Trump (57.1%), who was the first and most reported actor using the label during the analyzed period. Later on, articles on Austrian politicians increased (23.4%). Our results further showed that journalistic actors also sometimes used the fake news label to discredit other journalistic actors (8.3%). Nonpolitical actors and political actors from other countries (e.g., France and Russia) received less coverage (6.3% and 2.5%, respectively). considers populist political actors specifically, which constituted 76% of all actors using the fake news term as a label. It shows that the trend for the United States almost perfectly overlaps with the trend in . This indicates that in the US, only populist political actors (mainly Trump) applied the term this way. The trend line for Austria shows a completely different picture: the spikes in the spring and summer of 2017 for Austrian political actors, as shown in , were not caused by populist political actors. This might imply that using the fake news label in the US context was exclusively part of a populist strategy, and especially connected to Donald Trump, who coined the phrase. However, in Austria, newspapers also paid attention to non-populist actors using the fake news label. Furthermore, our results seem to suggest that in both the US and the Austrian case, politicians started using the fake news label once they were elected.Footnote7 Apparently, once populist politicians are in power, they express their anti-media sentiments more publicly.

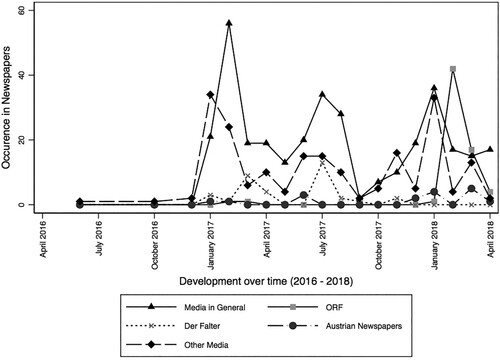

Considering actors that were discredited by the fake news label (), we saw that most articles did not report on specific outlets, but that the media in general was being attacked (44.1%). Furthermore, media outlets from the United States were again often reported (30%), showing that Trump's accusations received much attention in Austrian news reporting. In comparison, Austrian news outlets were reported in 21.5% of the cases (ORF: 14.3%, Der Falter: 4.7%, and other newspapers: 2.5%).

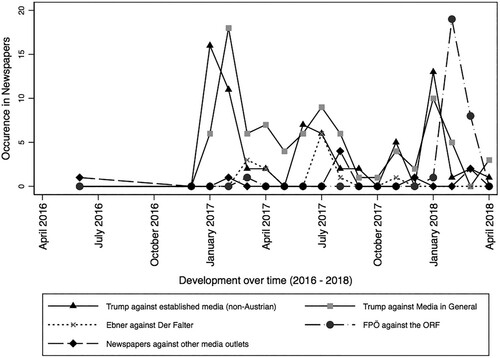

More in detail, we examined the most frequently occurring actor combinations for the fake news label. shows that Trump first used the term in December 2016 to attack the media in general and established media actors in the United States. The second two highest spikes relate to reports on Donald Trump discrediting news reports about his relation to Russia in summer 2017 (Die Presse Citation2017a) and a number of articles that reported on his announcement of the “winners” of the “fake news awards” in January 2018 (Kirby and Nelson Citation2018).

From 2017 onwards, there was an increase in the use of the term by Austrian political actors. The first reported Austrian actor was Bernhard Ebner, of the ÖVP lower Austria, who attacked the magazine Der Falter in the spring of 2017 (e.g., Brandl Citation2017). Articles reported on this instance again in the summer of 2017, when the chief editor of Der Falter, Florian Klenk, filed a lawsuit against Ebner and his party (e.g., Die Presse Citation2017b). In 2018, the FPÖ was reported to frequently use the label against the ORF. Here, articles reported on a meme Heinz-Christian Strache (then leader of the FPÖ) posted on Facebook attacking the ORF, accusing the public broadcaster of spreading fake news, lies, and propaganda (DerStandard.at Citation2018).

Interestingly, later on, journalistic actors also used the term to describe other journalistic actors. This indicates that the use of the fake news label was established by political actors but became somewhat socially acceptable over time, to be used by nonpolitical and media actors.

Finally, of all actors using the term as an empty buzzword (in 713 articles), we found that journalists were the biggest group using fake news to simply describe something as false (46.1%), with the majority being those journalists who wrote the analyzed articles (41.2%). Furthermore, nonpolitical actors (e.g., from culture and sports; 20.6%), political actors from the United States (13.7%) and Austria (13.6%), and political actors from other countries (6%) were reported to use the term to discredit a piece of information as false. The fact that journalistic actors used the empty buzzword most often is consonant with the finding that “false information” is the most visible definitional characteristic of fake news. For the analyzed newspapers, fake news was mostly an issue of falsehood, and they have adopted the term to express that something is incorrect.

Conclusion

Since 2016, fake news appears to have become one of the most worrisome issues for citizens (e.g., Mitchell et al. Citation2019). At the same time, members of academia (e.g., HLEG Citation2018), journalism (e.g., Badshah Citation2018), and politics (Murphy Citation2018) have criticized the use of the term widely, and the term itself has become a weapon that is used against the news media as democratic institutions. Nevertheless, since 2016, news coverage on fake news has exploded in the United States (McNair Citation2017). We showed that this excessive interest in fake news can also be observed in Austrian media discourses. Here, the term was used in three different contexts. It was applied to describe forms of disinformation (i.e., the fake news genre). These fabricated stories first gained attention during the 2016 US presidential election but became a much-discussed issue in Austria as well. Second, the term has been instrumentalized by a number of political actors, who have used it as a label to critically attack the news media (i.e., the fake news label). Third, we showed that it has also been applied more generally to articulate a disagreement with a statement or information provided by a non-media actor—or simply used as a synonym for “falsehood” or “lie.” Consequently, while fake news started out as a problem of an increase in disinformation, it has become a discussion of attacks on the news media and has been normalized as a catchy buzzword to express doubts about information in general.

In sum, our analysis shows that in the studied time period the discourse surrounding fake news as a genre was most prevalent—suggesting that fake news was still first and foremost a discussion about disinformation. However, other journalistic discourses on fake news have developed over time. One discussion centers around the fake news label, where journalists have mostly reported on populist political actors using the term against established media and the media in general. However, in some instances, they used the label themselves against other media outlets. Furthermore, journalists have characterized fake news predominantly as false information, and they have enlarged the discussion around this concept by using it as a catchy buzzword for anything that is inaccurate. In all three contexts, actors from the United States played a central role. However, actors from Austria and other countries also received notable coverage in the news about fake news. By using the term “fake news” frequently in different contexts, journalists contributed to its salience as well as ambiguity and, importantly, assisted in its normalization.

There are a number of caveats in our study. First of all, we present the results of a broad and descriptive analysis of media content. While this limits our conclusions on some dimensions, we do answer a call by a number of scholars for more descriptive studies on developments over time in communication research, which seems particularly important in the context of rather new phenomena such as fake news. We hope our baseline findings inspire future research to further disentangle the conditions under which a fake news debate has and will develop in the news media. For example, such work might study the use of specific news frames or discussion patterns in relation to “fake news”, and thus identify more elaborate evaluations of the term and its consequences. Future researchers could also zoom in on only one of the dimensions in our study; for example, they could study only coverage of the fake news label and how journalists evaluate such attacks. While one study has already provided some insights on how The New York Times reacts to such attacks on its own coverage (Lischka Citation2019), it is also relevant to investigate how the media evaluate instances where the fake news label is applied against other outlets or—more broadly—to the media as a democratic institution. What is more, we see our results as a foundation for more comparative and longitudinal content analysis, which will show when a journalistic debate such as this one about fake news peaks and decreases (e.g., Vasterman Citation2005). This kind of research can show how the journalistic coverage of the term “fake news” evolves in the coming years to see whether the somewhat excessive use of the term was a short-lived novelty or whether the term and all its concepts are here to stay.

Furthermore, we are at this point only able to speculate on the effects this analyzed media coverage has on citizens. In the most general sense, future studies must focus on whether the prominence of the term alone in public debates matters. For instance, we have argued that the normalization of the term is dangerous, as it might strengthen the effectiveness of the fake news label. Available research on repetitive framing (e.g., Lecheler and de Vreese Citation2013) and repetition in persuasion (e.g., Dechêne et al. Citation2010) has showed that repeated exposure increases message effects. However, too much repetition of a message may cause reactance in citizens (Koch and Zerback Citation2013). Constant repetition of the fake news label could, therefore, also backfire and weaken the perceived credibility of politicians who repeatedly use the term, compared to citizens’ trust in the news media that are being attacked. A next step may be more specific studies on the conditions under which detrimental effects of exposure to the term could occur. For instance, effects of the fake news label are likely related to partisan ideology (e.g., Guess, Nyhan, and Reifler Citation2017) and may differ widely between countries and media systems.

Nonetheless, the potential risk that the fake news label might be an effective instrument in influencing media perceptions of (at least some) citizens should be reason enough to rethink the use of the term—especially considering that it has no intrinsic meaning independent of the context in which it is used. In sum, our results thus suggest that journalists’ usage of the term “fake news” contributes to its continuing salience and might even strengthen its trivialization. While a complete abandonment of the term in the news might be unrealistic, we urge journalists to use the term less often and more consciously. This is in line with other scholars, who have demanded a more conscious usage of the term in science as well as in journalism and who have proposed a return to the use of more meaningful notions, such as “disinformation” or simply “false news” (e.g., Egelhofer and Lecheler Citation2019; HLEG Citation2018; Wardle and Derakhshan Citation2017; Zimmermann and Kohring Citation2020).

Furthermore, as “even findings that are well-established by social scientists” are often not known to the journalistic community (e.g., Lazer et al. Citation2017, 9), we see a great need to strengthen the dialogue between (social) science and journalism. Specifically, journalists need to be informed that a trivialization of the term might backfire and damage their work's credibility.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (1.6 MB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 However, it is noteworthy that while fake news is created intentionally, its dissemination can be unintentional (see also Egelhofer and Lecheler Citation2019, 100).

2 We included articles of the print versions of all eight newspapers, and additionally all articles by the online versions (of four news outlets).

3 A translated version of the codebook (from German to English) can be found in online Appendix B.

4 Except for actors responsible for counteracting, here we coded dichotomously if the following actor categories were mentioned in the context of counteracting measures: political actors, social media companies, journalistic actors, fact-checking agencies, and citizens (in the context of media literacy).

5 These percentages exceed 100%, as some articles included several fake news types, and categories were thus not mutually exclusive.

6 We did not have access to the online versions of four out of eight of the analyzed newspapers. Specifically, of the three tabloid newspapers we could analyze only the print version, which is why articles by broadsheets are overrepresented in our sample. To ensure that our results are not strongly influenced by the uneven distribution of outlets, we conducted the analysis exclusively with print articles as well. However, the results do not differ substantially from those presented here (see online Appendix D).

7 The inauguration of Donald Trump was in January 2017; the inauguration of the ÖVP-FPÖ coalition was in January 2018.

References

- Albright, J. 2017. “Welcome to the Era of Fake News.” Media and Communication 5 (2): 87–89. doi: 10.17645/mac.v5i2.977

- Allcott, H., and M. Gentzkow. 2017. “Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 31 (2): 211–236. doi: 10.1257/jep.31.2.211

- Badshah, N. 2018. “BBC Chief: ‘Fake News’ Label Erodes Confidence in Journalism.” https://www.theguardian.com/media/2018/oct/08/bbc-chief-fake-news-label-erodes-confidence-in-journalism.

- Bale, T., S. van Kessel, and P. Taggart. 2011. “Thrown Around with Abandon? Popular Understandings of Populism as Conveyed by the Print Media: A UK Case Study.” Acta Politica 46 (2): 111–131. doi: 10.1057/ap.2011.3

- Baym, G. 2005. “The Daily Show: Discursive Integration and the Reinvention of Political Journalism.” Political Communication 22 (3): 259–276. doi: 10.1080/10584600591006492

- Berghel, H. 2017. “Alt-News and Post-Truths in the ‘Fake News’ Era.” Computer 50 (4): 110–114. doi: 10.1109/MC.2017.104

- Brandl, M. 2017. “Ebner zu Falter-Fake-News: Verzweifelter Versuch mit alter Geschichte sinkende Verkaufszahlen am Leben zu halten” [Ebner about Falter Fake News: Desperate Attempt to Keep Declining Sales Figures Alive with Ancient Story] (Press release). https://www.ots.at/presseaussendung/OTS_20170110_OTS0123.

- Brummette, J., M. DiStaso, M. Vafeiadis, and M. Messner. 2018. “Read All About It: The Politicization of ‘Fake News’ on Twitter.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 95 (2): 497–517. doi: 10.1177/1077699018769906

- Carlson, M. 2017. Journalistic Authority: Legitimating News in the Digital Era. New York City: Columbia University Press.

- Carlson, M. 2018. “Fake News as an Informational Moral Panic: The Symbolic Deviancy of Social Media During the 2016 US Presidential Election.” Information, Communication & Society 19 (13): 1879–1888.

- Dechêne, A., C. Stahl, J. Hansen, and M. Wänke. 2010. “The Truth About the Truth: A Meta-Analytic Review of the Truth Effect.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 14 (2): 238–257. doi: 10.1177/1088868309352251

- DerStandard.at. 2018. “ORF-Anchor Armin Wolf klagt Strache wegen Vorwurfs der Lüge” [ORF-Anchor Armin Wolf Sues Strache for Accusation of Lying]. https://derstandard.at/2000074159501/ORF-Anchor-Armin-Wolf-klagt-Strache-wegen-Vorwurf-der-Luege.

- De Vreese, C. H. 2017. “Political Journalism in a Populist Age (Policy Paper).” https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Political-Journalism-in-a-Populist-Age.pdf?x78124.

- Die Presse. 2017a. “Trump wettert gegen US-Medien” [Trump Rages against US Media]. June 27. https://diepresse.com/home/ausland/aussenpolitik/5242341/Trump-wettert-gegen-USMedien.

- Die Presse. 2017b. “Pröll-Privatstiftung: Zivilprozess um ‘Fake News’-Vorwurf” [Pröll Private Foundation: Civil Suit Over ‘fake News’ Accusation]. July 3. https://diepresse.com/home/kultur/medien/5245707/ProellPrivatstiftung_Zivilprozess-um-Fake-NewsVorwurf?direct=5252669&_vl_backlink=/home/innenpolitik/5252669/index.do&selChannel=.

- Die Presse. 2018a. “Mehrheit der Österreicher glaubt, dass Fake News Wahl beeinflusst haben” [Majority of Austrians Believes Fake News Influenced Election Outcome]. January 19. https://diepresse.com/home/innenpolitik/5356510/Mehrheit-der-Oesterreicher-glaubt-dass-Fake-News-Wahl-beeinflusst.

- Die Presse. 2018b. “Affäre um NS-Liederbuch: Strache wehrt sich gegen ‘Fake News’” [Strache Defends Himself Against ‘fake news’]. January 26. https://diepresse.com/home/innenpolitik/noewahl/5360576/Affaere-um-NSLiederbuch_Strache-wehrt-sich-gegen-Fake-News.

- DiFranzo, D., and K. Gloria-Garcia. 2017. “Filter Bubbles and Fake News.” XRDS: Crossroads, The ACM Magazine for Students 23 (3): 32–35. doi: 10.1145/3055153

- Eberl, J. M., H. G. Boomgaarden, and M. Wagner. 2017. “One Bias Fits All? Three Types of Media Bias and their Effects on Party Preferences.” Communication Research 44 (8): 1125–1148. doi: 10.1177/0093650215614364

- Egelhofer, J. L., and S. Lecheler. 2019. “Fake News as Two-Dimensional Phenomenon: A Framework and Research Agenda.” Annals of the International Communication Association 43 (2): 97–116. doi: 10.1080/23808985.2019.1602782

- Farkas, J., and J. Schou. 2018. “Fake News as a Floating Signifier: Hegemony, Antagonism and the Politics of Falsehood.” Javnost – The Public 25 (3): 298–314. doi: 10.1080/13183222.2018.1463047

- Fitzgerald, S. 2017. “Is Successful Brain Training Fake News? Neurologists Parse Out the Messaging for Patients.” Neurology Today. April 6. https://journals.lww.com/neurotodayonline/Fulltext/2017/04060/Is_Successful_Brain_Training_Fake_News__.6.aspx.

- Fletcher, R., A. Cornia, L. Graves, and R. K. Nielsen. 2018. “Measuring the Reach of ‘Fake News’ and Online Disinformation in Europe.” https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/our-research/measuring-reach-fake-news-and-online-disinformation-europe.

- Funke, D. 2018. “Reporters: Stop Calling Everything ‘Fake News’.” Poynter. https://www.poynter.org/fact-checking/2018/reporters-stop-calling-everything-fake-news/.

- Grinberg, N., K. Joseph, L. Friedland, B. Swire-Thompson, and D. Lazer. 2019. “Fake News on Twitter during the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election.” Science 363 (6425): 374–378. doi: 10.1126/science.aau2706

- Guess, A., B. Nyhan, and J. Reifler. 2017. “‘You’re Fake News!’ The 2017 Poynter Media Trust Survey.” https://poyntercdn.blob.core.windows.net/files/PoynterMediaTrustSurvey2017.pdf.

- Habgood-Coote, J. 2019. “Stop Talking About Fake News!” Inquiry 62 (9–10): 1033–1065. doi: 10.1080/0020174X.2018.1508363

- Hallin, D. C., and P. Mancini. 2004. Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- HLEG. 2018. “A Multi-Dimensional Approach to Disinformation.” https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/final-report-high-level-expert-group-fake-news-and-online-disinformation.

- Humprecht, E. 2019. “Where ‘Fake News’ Flourishes: A Comparison Across Four Western Democracies.” Information, Communication & Society 22 (13): 1973–1988. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2018.1474241

- Jagers, J., and S. Walgrave. 2007. “Populism as Political Communication Style: An Empirical Study of Political Parties’ Discourse in Belgium.” European Journal of Political Research 46 (3): 319–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00690.x

- Kirby, J., and L. Nelson. 2018. “The ‘Winners’ of Trump’s Fake News Awards, Annotated.” VOX. January 17. https://www.vox.com/2018/1/17/16871430/trumps-fake-news-awards-annotated.

- Koch, T., and T. Zerback. 2013. “Helpful or Harmful? How Frequent Repetition Affects Perceived Statement Credibility.” Journal of Communication 63 (6): 993–1010. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12063

- Krämer, B. 2018. “How Journalism Responds to Right-Wing Populist Criticism.” In Trust in Media and Journalism, edited by K. Otto and A. Köhler, 137–154. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Kurtzleben, D. 2017. “With ‘Fake News,’ Trump Moves from Alternative Facts to Alternative Language.” NPR. February 17. https://www.npr.org/2017/02/17/515630467/with-fake-news-trump-moves-from-alternative-facts-to-alternative-language.

- Ladd, J. 2012. Why Americans Hate the Media and How It Matters. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Lakoff, G. 2018. “How You Help Trump.” Medium. May 24. https://medium.com/@GeorgeLakoff/how-you-help-trump-9d0139b9d4c9.

- Lazer, D., M. Baum, J. Benkler, A. Berinsky, K. Greenhill, M. Metzger, B. Nyhan, et al. 2018. “The Science of Fake News.” Science 359 (6380): 1094–1096. doi: 10.1126/science.aao2998

- Lazer, D., M. Baum, N. Grinberg, L. Friedland, K. Joseph, W. Hobbs, and C. Mattsson. 2017. “Combating Fake News: An Agenda for Research and Action Drawn from Presentations By.” May. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Combating-Fake-News-Agenda-for-Research-1.pdf.

- Lecheler, S., and C. H. de Vreese. 2013. “What a Difference a Day Makes? The Effects of Repetitive and Competitive News Framing Over Time.” Communication Research 40 (2): 147–175. doi: 10.1177/0093650212470688

- Lischka, J. A. 2019. “A Badge of Honor?” Journalism Studies 20 (2): 287–304. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2017.1375385

- Lombard, M., J. Snyder-Duch, and C. C. Bracken. 2002. “Content Analysis in Mass Communication: Assessment and Reporting of Intercoder Reliability.” Human Communication Research 28 (4): 587–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2002.tb00826.x

- McNair, B. 2017. Fake News: Falsehood, Fabrication and Fantasy in Journalism. New York: Routledge.

- Media Analyse. 2015–2018. “Studien [Studies].” https://www.media-analyse.at/p/2.

- Meeks, L. 2019. “Defining the Enemy: How Donald Trump Frames the News Media.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 97 (1): 211–234. doi: 10.1177/1077699019857676

- Mitchell, A., J. Gottfried, S. Fedeli, G. Stocking, and M. Walker. 2019. “Many Americans Say Made-Up News Is a Critical Problem That Needs To Be Fixed.” Pew Research Center. https://www.journalism.org/2019/06/05/many-americans-say-made-up-news-is-a-critical-problem-that-needs-to-be-fixed/.

- Mourão, R. R., and C. T. Robertson. 2019. “Fake News as Discursive Integration: An Analysis of Sites That Publish False, Misleading, Hyperpartisan and Sensational Information.” Journalism Studies. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2019.1566871.

- Murphy, M. 2018. “Government Bans Phrase ‘Fake News’.” The Telegraph. October 23. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/2018/10/22/government-bans-phrase-fake-news/.

- Nelson, J. L., and H. Taneja. 2018. “The Small, Disloyal Fake News Audience: The Role of Audience Availability in Fake News Consumption.” New Media & Society. doi:10.1177/1461444818758715.

- Newman, N., R. Fletcher, A. Kalogeropoulos, D. A. L. Levy, and R. K. Nielsen. 2018. “Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2018.” media.digitalnewsreport.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/digital-news-report-2018.pdf?x89475.

- Newman, N., R. Fletcher, A. Kalogeropoulos, D. A. L. Levy, and R. K. Nielsen. 2019. “Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2019.” https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2019-06/DNR_2019_FINAL_1.pdf.

- Nielsen, R. K., and L. Graves. 2017. “‘News You Don’t Believe’: Audience Perspectives on Fake News.” https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2017-10/Nielsen%26Graves_factsheet_1710v3_FINAL_download.pdf.

- Quarfoot, D., and R. A. Levine. 2016. “How Robust Are Multirater Interrater Reliability Indices to Changes in Frequency Distribution?” The American Statistician 70 (4): 373–384. doi: 10.1080/00031305.2016.1141708

- Reinemann, C., T. Aalberg, F. Esser, J. Strömbäck, and C. H. de Vreese. 2016. “Populist Political Communication.” In Populist Political Communication in Europe, edited by T. Aalberg, F. Esser, C. Reinemann, J. Stromback, and C. De Vreese, 12–25. New York: Routledge.

- Reuters. 2018. “Austrian Broadcaster Sues Far-Right Leader over Fake News Claim.” February 26. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-austria-politics-media/austrian-broadcaster-sues-far-right-leader-over-fake-news-claim-idUSKCN1GA2T2.

- Rooduijn, M., S. Van Kessel, C. Froio, A. Pirro, S. De Lange, D. Halikiopoulou, P. Lewis, C. Mudde, and P. Taggart. 2019. “The PopuList: An Overview of Populist, Far Right, Far Left and Eurosceptic Parties in Europe.” http://www.popu-list.org.

- RSF. 2017. “Predators of Press Freedom Use Fake News as a Censorship Tool.” Reporters without Borders. https://rsf.org/en/news/predators-press-freedom-use-fake-news-censorship-tool.

- RSF. 2018a. “2018 World Press Freedom Index.” Reporters without Borders. https://rsf.org/en/ranking/2018#.

- RSF. 2018b. “More Far-Right Threats to Austria’s Public Broadcaster.” Reporters without Borders. https://rsf.org/en/news/more-far-right-threats-austrias-public-broadcaster.

- Silverman, C. 2016. “This Analysis Shows How Fake Election News Stories Outperform Real News on Facebook.” https://www.buzzfeed.com/craigsilverman/viral-fake-election-news-outperformed-real-news-on-facebook?utm_term=.df1X0G6eG#.joeLeg8xg.

- Silverman, C., and L. Alexander. 2016. “How Teens in the Balkans Are Duping Trump Supporters with Fake News.” Buzzfeed News. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/craigsilverman/how-macedonia-became-a-global-hub-for-pro-trump-misinfo.

- Tandoc Jr., E. C., J. Jenkins, and S. Craft. 2019. “Fake News as a Critical Incident in Journalism.” Journalism Practice 13 (6): 673–689. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2018.1562958

- Tandoc, E. C. J., Z. W. Lim, and R. Ling. 2018. “Defining ‘Fake News’.” Digital Journalism 6 (2): 137–153. doi: 10.1080/21670811.2017.1360143

- Van Duyn, E., and J. Collier. 2019. “Priming and Fake News: The Effects of Elite Discourse on Evaluations of News Media.” Mass Communication and Society 22 (1): 29–48. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2018.1511807

- Vasterman, P. L. 2005. “Media-Hype: Self-Reinforcing News Waves, Journalistic Standards and the Construction of Social Problems.” European Journal of Communication 20 (4): 508–530. doi: 10.1177/0267323105058254

- Wagner, M., J. Aichholzer, J.-M. Eberl, T. Meyer, N. Berk, N. Büttner, H. Boomgaarden, S. Kritzinger, and W. C. Müller. 2018. AUTNES Online Panel Study 2017 – Dataset. Vienna.

- Wardle, C. 2017. “Fake News. It’s Complicated.” https://medium.com/1st-draft/fake-news-its-complicatedd0f773766c79.

- Wardle, C., and H. Derakhshan. 2017. “Information Disorder: Toward an Interdisciplinary Framework for Research and Policymaking.” Council of Europe report, DGI (2017), 9.

- Watts, M. D., D. Domke, D. V. Shah, and D. P. Fan. 1999. “Elite Cues and Media Bias in Presidential Campaigns: Explaining Public Perceptions of a Liberal Press.” Communication Research 26 (2): 144–175. doi: 10.1177/009365099026002003

- Wettstein, M., F. Esser, F. Büchel, C. Schemer, D. S. Wirz, A. Schulz, N. Ernst, S. Engesser, P. Müller, and W. Wirth. 2019. “What Drives Populist Styles? Analyzing Immigration and Labor Market News in 11 Countries.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 96 (2): 516–536. doi: 10.1177/1077699018805408

- Zimmermann, F., and M. Kohring. 2020. “Mistrust, Disinforming News, and Vote Choice: A Panel Survey on the Origins and Consequences of Believing Disinformation in the 2017 German Parliamentary Election.” Political Communication. doi:10.1080/10584609.2019.1686095.