ABSTRACT

Audience engagement has become a key concept in contemporary discussions on how news companies relate to the public and create sustainable business models. These discussions are irrevocably tied to practices of monitoring, harvesting and analyzing audience behaviours with metrics, which is increasingly becoming the new currency of the media economy. This article argues this growing tendency to equate engagement to behavioural analytics, and study it primarily through quantifiable data, is limiting. In response, we develop a heuristic theory of audience engagement with news comprising four dimensions—the technical-behavioural, emotional, normative and spatiotemporal—and explicate these in terms of different relations of engagement between human-to-self, human-to-human, human-to-content, human-to-machine, and machine-to-machine. Paradoxically, this model comprises a specific theory of audience engagement while simultaneously making visible that constructing a theory of audience engagement is an impossible task. The article concludes by articulating methodological premises, which future empirical research on audience engagement should consider.

Introduction

Audiences have been ascribed a diverse set of roles with varying degrees of significance throughout the history of media and communication research in general and journalism studies in particular. They have been portrayed as masses that are manipulated, citizens that are informed, consumers that select, products that are sold, individuals that seek or avoid, networks that form, participants that co-produce, users that interact, groups that meet, and phantom constructs that are imagined, among many other—often incommensurable—conceptualizations (Napoli Citation2003; Lewis, Inthorn, and Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2005). Even though such varying notions of audiences have different discursive “baggage”, most of them imply a common interest in audiences as behaviouristic beings. It is the behaviour of audiences that primarily drives media companies and researchers’ interest in them: what they do when they engage with news and other forms of media content; how, where, and when they do it; and what motivates their behaviour.

In recent years, as we have entered the “media analytics stage” of technological media (Manovich Citation2018), audience metrics have come to the fore in these discussions, especially within the news industry, which relies on metrics not only to monitor audience behaviour but also, increasingly, as the preferred way to analyze the inner and perhaps unconscious motivations driving audience engagement (e.g American Press Institute Citation2019). Academics focusing on the institutional state-of-the-art understandably follow in tandem, researching the uses, feelings, and social integration of analytic systems (e.g., Tandoc Citation2019; Zamith, Belair-Gagnon, and Lewis Citation2019). However, marshalling data in this way conflates what metrics actually do (a system logic that aggregates measurable digital signals, and correlates this with pre-existent data through models, algorithms, and machine learning) with what they seem to imply (a market logic that hopes to predict people’s preferences and predispositions). Within journalism studies, researchers have been preoccupied with the connections between audience metrics, engagement and news, arguing that engagement is a significant factor for the business models of digital-born and legacy news media (e.g., Batsell Citation2015; Nelson and Webster Citation2016), and that newsroom practices are increasingly shaped by the analysis of audience metrics in order to create news suited to engage the audience (e. g. Cherubini and Nielsen Citation2016; Ferrer-Conill and Tandoc Citation2018; Zamith, Belair-Gagnon, and Lewis Citation2019) even though the adoption of audience metrics in newsrooms might have been slower and less universal than first assumed (Nelson and Tandoc Citation2019). In recent years, new roles such as “engagement editor”, “engagement reporter”, “head of audience engagement” and similar titles have emerged in newsrooms, predominantly in the US, the UK and Australia. Their work is “to distill the information gathered about the audience, conveying audience behaviour to the editorial team and proposing a course of action that considers and aligns with audience insight”, according to Ferrer-Conill and Tandoc (Citation2018, 444).

There are, however, at least two interwoven conceptual and empirical challenges with the ways in which industry representatives and some researchers often deal with issues of engagement in the current stage of media analytics. First, engagement—which is closely linked to personal wants and needs, emotions and other qualitative aspects of social life—is typically treated as a quantifiable and measurable phenomenon. It is therefore difficult to assess to what degree audience metrics can actually capture the essence of engagement. Second, engagement metrics are not, in reality, metrics of engagement—they are actually measures of interaction and participation, or simple popularity cues (Haim, Kümpel, and Brosius Citation2018). In other words, the metrics used to analyze engagement are aggregated snapshots of digital traces that signal behavioural actions which do not necessarily translate to key considerations of how engagement occurs. In other fields of research, such as social psychology, public engagement is often linked to concepts with more ethereal qualities like trust and respect. Similarly, in political communication and social movements literature, engagement is frequently equated with ideals of citizenship. Boeckmann and Tyler (Citation2002), for example, found that civic engagement increases when people feel they are respected members of a community, something which is difficult to capture and measure with behavioural metrics. The broader problem, to put it simply, is that while engagement can take many forms, the metrics media companies are able to generate and rely upon only provide insights into a small portion of what engagement is and entails. Moreover, researchers tend to adopt this industry discourse, which further conflates audience metrics with audience engagement.

This article addresses these issues to argue against the continuation of a tendency to truncate our knowledge of what audience engagement is in relation to news, lest we lose sight of its more profound conceptual implications. Specifically, we illustrate how the dominant technical and metrics-oriented understanding and operationalization of audience engagement leads to a confusion between engagement as an emotional state that spans across time and space on the one hand, and technical behaviours like digital interaction and participation that carry normative implications on the other. Based on this argument, we unpack four dimensions we believe should be invoked to theoretically assess audience engagement with news: (1) the technical-behavioural dimension, which accounts for the actions that come out of audience engagement and the digital traces those actions leave behind; (2) the emotional dimension, which covers how audience engagement is the result of social-psychological and affective connections between media and audiences; (3) the normative dimension, in which distinctions between wanted and unwanted, good and bad forms of audience engagement are made; and (4) the spatiotemporal dimension, which makes visible that audience engagement is shaped by social context across time and space, as opposed to something that spontaneously occurs in the here and now, only to then abruptly vanish again. Following from this, we explicate these dimensions in terms of different relations of audience engagement, specifically between human-to-self, human-to-human, human-to-content, human-to-machine, and machine-to-machine.

It is crucial to note that this four-dimensional heuristic approach to conceptualize audience engagement is not intended to be an all-encompassing, “grand theory”. Rather, we argue that audience engagement is so complex that, at best, one can modestly aim to problematize, systematize and clarify key dimensions that shape engagement. In order to offer pragmatic ways to attend to such challenges, in the final sections of this article, we highlight some of the implications of our audience-centric theorizing of engagement, deconstruct our own argument to expose some of its limitations, before finally offering some methodological premises to help inform research designs.

What is Audience Engagement?

Several scholars have raised explicit concerns about the lack of concrete definitions of engagement (Ferrer-Conill and Tandoc Citation2018; Meier, Kraus, and Michaeler Citation2018; Nelson Citation2018). However, scholarship on audience engagement often agrees that it “refers to the cognitive, emotional, or affective experiences that users have with media content or brands” (Broersma Citation2019, 1). Such an open approach positions engagement as a slippery concept because it is experiential, which implies concrete forms of action and interaction, while at the same time emotional, which connotes a highly subjective relation with media. In that sense, Hill (Citation2019:, 6) offers a pragmatic conception of engagement, which posits it as an all-encompassing term to represent how audiences “experience media content, artefacts and events, from (their) experience of live performances, to social media engagement, or participation in media itself”. We align with such an audience-centric understanding of engagement, but recognize that this only accounts for one possible perspective of engagement related to journalism. Nelson (Citation2019), for instance, distinguishes between reception-oriented and production-oriented engagement, the latter pointing to how news organizations encourage audiences to contribute content and story ideas to news. However, such a distinction is not as clear-cut as it may seem, as the ways in which news publishers utilize reception-oriented engagement through audience metrics clearly impact the production of news (Tandoc Citation2015), and vice versa. For example, if reception-oriented metrics indicate that certain types of news create more engagement, news organizations will probably choose to produce more such news. Similarly, the algorithmic prioritization of most read, liked, or shared stories makes audiences more likely to encounter and potentially “engage” with them. This means that such automated parsing of behavioural engagement can shape news consumption by recommending readers what others have consumed.

In this respect, distinguishing between reception and production-oriented engagement can be important in understanding how, for example, for-profit and nonprofit news providers relate differently to audience engagement (Belair-Gagnon, Nelson, and Lewis Citation2019). However, such a distinction does little to address the underlying epistemological problem, namely that engagement is predominantly conceptualized as behavioural. A first step towards a clearer understanding of audience engagement is therefore to distinguish between felt and behavioural engagement. Felt engagement relates to affective outcomes and intentions, while behavioural engagement relates to performance (Stumpf, Tymon, and van Dam Citation2013) and what Lawrence, Radcliffe, and Schmidt (Citation2018) call “practiced engagement”. In practice, the issue is that identifying and quantifying engagement favours behaviour over emotion. This is likely attributable to the fact that behaviour is, undoubtedly, easier to pinpoint. As humans—and relatedly, as researchers—while we are not always adept at identifying emotions, we have learned to observe behaviour, as well as building systems to record and interpret it. The result is increasingly sophisticated technical systems that operationalize a desire to quantify behaviour in all walks of social life (Espeland and Stevens Citation2008). Measuring felt engagement is much more difficult, despite continued efforts in disciplines such as psychology, computer science, neuroscience, and linguistics to model quantifiable behavioural cues—such as facial expression or word choice (Zeng et al. Citation2009), and even mouse cursor movements (Hibbeln et al. Citation2017)—said to capture particular affective states.

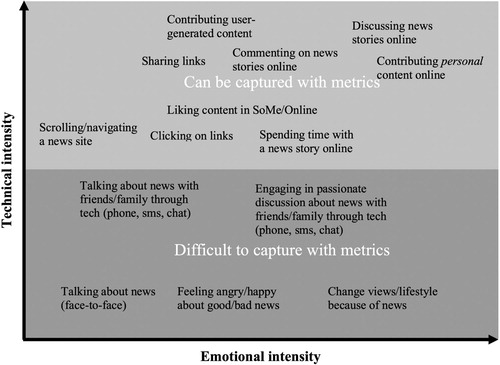

In , which offers a heuristic overview of some common practices of engagement with the news, we can clearly see this challenge. The figure illustrates various kinds of audience engagement with news along two axes, technicality and emotionality, which also vary in terms of intensity. The types of engagement on the upper half of the figure, the ones that news organizations tend to spend time and money capturing, are the only ones that can be reliably captured and measured by audience metrics. Paradoxically, the types of engagement in the lower half of the figure, the ones that are difficult to capture with audience metrics, are the ones that might be the most profound. This is the kind of engagement that affects people, that perhaps changes views and behaviours and therefore has democratic impact. This kind of engagement can manifest itself as technical engagement, but—as audience research has clearly shown (e.g., Swart, Peters, and Broersma Citation2018; Ytre-Arne and Moe Citation2018)—quite often it does not. The perhaps somewhat banal but nonetheless crucial point is that people can be emotionally engaged with news even if they do not participate in it by creating content, commenting, sharing or liking news stories online. And most often, they do not.

Figure 1. The challenge of metrics. Examples of audience engagement with varying degrees of emotional and technical intensity

The second step towards a clearer understanding of audience engagement with news is untangling its spatiotemporal and normative aspects. Engagement builds, fluctuates, and diminishes over time, and relates to time in both linear (i.e., cumulative awareness, developing knowledge) and non-linear (i.e., monitorial interest, affective sentiment) ways. And yet, it is almost impossible to properly demarcate when engagement starts and ends, or for that matter, how it spreads. Moreover, engagement is linked to socio-cultural and geographical contexts. The same news event or experience might cause different degrees of engagement in different spaces. Also, assessing the quality of engagement declares an obvious normative dimension that is often forgotten or implicit in both industry and scholarship (Nelson Citation2018). The emotional responses people may have to news and the consequent actions they might perform—what Couldry, Livingstone, and Markham (Citation2010) refer to as the “public connection” that bridges people’s private worlds to the world beyond—can range from constructive to destructive, in relation to civic ideals. Engagement can be normatively positive or negative, however, news companies’ drive to increase user engagement as a key performance indicator (KPI) positions engagement as an inherently positive aspect. Yet, as instances of harassed journalists (Chen, Pain, and Chen Citation2018), disinformation campaigns (Quandt Citation2018), or the increase of incivility in comments sections (Su et al. Citation2018) evidently indicate, high engagement is often demonstrably harmful.

Engagement carries dialectical tensions of objective actions and subjective experiences, of material and symbolic practices, of behaviour and emotion that, when flattened through metrics-based fiat, quickly become reductionist because they fail to capture the social, spatial, temporal, and normative. In the following sections, we unpack this complexity by looking more closely at four central dimensions of audience engagement that are, to varying degrees, explicit and implicit in public discourse surrounding it: the technical-behavioural, emotional, normative and spatiotemporal.

The Technical-Behavioural Dimension of Audience Engagement

Media companies and researchers have long monitored audience behaviour, although recent years have seen this done in increasingly sophisticated ways. Indeed, audience metrics have become so complex, rich and powerful in the digital era that they are targeted as a business model in themselves (Belair-Gagnon and Holton Citation2018). The real value of global mega-companies like Google, Amazon and Facebook lies in their sophisticated methods for harvesting, analyzing and capitalizing from tremendous amounts of big data on user behaviour, which empowers them not only with knowledge and insights that advertizers are willing to pay for, but also with a wider control over cultural and social networks (Taplin Citation2017). The rapid expansion of computational power, ubiquity of digital tracking, and relative affordability of many straightforward analytics measures and packages has made the “datafication” of citizens, publics, consumers, audiences, or users increasingly foundational for institutions across society, often not only as a tool, but as an entirely new epistemological paradigm for making sense of the world (cf. Kitchin Citation2014; Bolin and Velkova Citation2020).

In newsrooms, these trends have gained increasing prominence over the past decade. As news media increasingly rely on quantification (Coddington Citation2015; Ferrer-Conill Citation2017), user metrics become the embodiment of the audience in the newsroom. The current dominant position of metrics and analytics to “make sense” of digital news audiences, makes the technical-behavioural dimension of audience engagement quite powerful. It is not our claim that audience behaviour and the digital traces they leave behind are irrelevant to engagement. However, there is conceptual and empirical value in specifying and distinguishing between different types of behaviours and interactions to elicit a more comprehensive account of how they relate to engagement. Ksiazek, Peer, and Lessard (Citation2014) place engagement on a continuum from exposure to interactivity, while McMillan’s (Citation2005) overview of different kinds of interactivity and thereby behaviours of engagement offers a productive way to start unpacking the various aspects of the technical-behavioural dimension of audience engagement. McMillan distinguishes between human-to-human, human-to-computer and human-to-content interactivity, and argues that these three kinds of interactivity can be divided in features, processes and perceptions. Features are the characteristics of the communication environment that make it interactive (the technologies, platforms, etcetera that facilitate interactions), while processes are the actual activity of interacting. Perceptions, on the other hand, are the beliefs in, and assessments of, the degrees to which the features have affordances that enable interaction. These three categories, or phases, of interactivity are therefore to a certain degree similar to our distinction between technicality, behaviours, emotions and normativity, as the features are inherently technical, the processes are behavioural and the perceptions are both emotional and normative. (In a later review of interactivity research, McMillan (Citation2019) exchanged “processes” with “actions”, thereby underlining to an even greater extent this categories’ connection with the behavioural.) The important point arising from this—and elaborated upon further below, see —is that technical-behavioural interactions with news (and other media content), and thereby engagement with such content, are inherently tied to things that are difficult to measure, like beliefs, value assessments, and emotions. McMillan’s original model of interactivity therefore establishes a fruitful point of reference not only when attempting to construct a model of audience engagement in which various interactions, or relations, are accounted for, but also for understanding how the technical-behavioural dimension is related to both the emotional dimension and the normative dimension.

Table 1. Examples of audience engagement dependent on relations and dimensions.

The Emotional Dimension of Audience Engagement

It seems evident that one of the key assumptions of audience engagement, namely an affective disposition toward mediated information, is challenging to capture with traditional metrics. Similarly, from a conceptual point of view, models that neglect to attend the attitudinal and affective underpinnings of the emotional dimension of engagement are incomplete (Gastil and Xenos Citation2010). Affect is conventionally understood as the basic sense of feeling, while emotions are the expression of those feelings. Intimately imbricated, affect can be thought of as the unconscious potentiality that prefigures engagement, a “general way of sense-making,” that extends beyond feeling to inform our “sensibility toward the world surrounding us, which is inclusive of potentialities” (Papacharissi Citation2015, 15). Emotion is the expression of affect, often individualized and—by definition—relational, that is to say directed toward something (e.g., a person, issue, technology, etcetera), in a way that blurs the misguided binary between emotion/reason or cognition/affect. Whether in a commonsensical, literal, or conceptual sense, the notion of engagement presupposes some degree of affective potential and emotional interaction with the activity or orientation under investigation. While it need not presume the strength, nor the specific character or quality of the disposition, attentiveness to the emotional aspects of engagement are central given their significance “in the constitution of social relationships, institutions, and processes” (Barbalet Citation2001, 9).

Journalism, like most institutions in the creative industries, is—and always has been—an emotional industry that in programmed ways gives rise to fear and anger, inspires joy and affection, begets sadness and surprise, and many other emotional dispositions (Peters Citation2011; Steensen Citation2017; Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2019). This occurs across a variety of news-related practices, experienced with varied intensities by different members of the audience. This subjective potential—the idea of bridging between the particular and identifying with something “greater” (Steensen Citation2017)—is what is frequently meant when we speak of engagement, with emotion typically thought of as the more intense and visible manifestation therein. A person can become acutely-concerned, passionately-discuss, even actively-campaign around an issue of public affairs through their engagement with journalism. Engagement can also be emotionally less intense and require limited audience investment, in line with what Picone et al. (Citation2019) label “small acts of engagement”, such as liking, sharing, and commenting.

Accordingly, a theoretical approach to audience engagement with news absent affect and emotion—no matter how helpful in broadening our understanding of the relative value of different digitally-measurable actions—is left wanting. This should be fairly uncontroversial, given the influence of the affective turn that swept across the humanities and social sciences in the 1990s. When thinking about audience engagement with news, the value and necessity of such a perspective becomes evident—engagement is about the potential to act. It is about understanding what combination of forces actually cause a transformative shift to occur, be it action, behaviour, or sentiment. Moreover, it is about indeterminacy, the “never-quite-knowing” quality of affect, which points to the fact that the sociocultural and political implications of engagement will not necessarily be something positive. Affective engagement and heightened emotional investment in the news may lead to outpourings of positive sentiment, as when donations soar in response to a humanitarian disaster, but such moments of promise can also lead to harmful outcomes, as when migrants are attacked—or killed—by those fearing the humanitarian crisis witnessed from afar is becoming a threat at home. This is precisely why engagement often remains so elusive to news organizations (Nelson Citation2018), and so difficult to capture for researchers, who both tend to focus on the here and now of news audiences as opposed to their processes of becoming over time (Peters and Schrøder Citation2018). In the ongoing era of digital fragmentation, journalism increasingly comprises and facilitates entry into a diverse range of affective spaces, meaning the types of audience engagement that occur are potentially quite diverse, not only in terms of their technical practices, but their associated emotional sentiments.

The Normative Dimension of Audience Engagement

Emotions are irrevocably tied to normativity and normative assumptions around engagement establish the structures by which society assesses and accepts or rejects specific behaviours. Neither emotions nor behaviours are neutral, they have impact and value with positive or negative outcomes on an individual, group or collective level. As Hall (Citation1973) noted in his formative work on audience reception, readings of a text cannot be uniformly assumed but are “decoded” in a variety of ways by audiences. Complexifying the point, it is evident that engagement is shaped by a host of personal factors, which have a significant possible impact on its normative intensity, direction, and character; be it gender, ethnicity, race, class, nationality, political outlook, generation, educational level, regional affiliation, or other social factors. While it is important to remark that identity is not determinative of the form engagement takes, it points to the fact that normative assessments and values are key to understanding how engagement relates to the sense-making practices of the audience (Chua and Westlund Citation2019).

However, the normative dimension is often overlooked or taken for granted in journalism scholarship and industry discourses on audience engagement. The traditional debates of engagement in journalism studies revolve around political participation and civic engagement (see Dahlgren Citation2009; Skoric et al. Citation2016), in which the normative underpinnings more often than not are presupposed. An idealist and normative understanding of journalism presupposes that consuming news is crucial for civic engagement, to ignite and maintain political knowledge, interest, and participation. Thus, in democratic societies, normative pressures establish that engagement with news is desirable and that news organizations should strive to enhance it. However, there is limited empirical support for this expected positive impact of engagement (see Rowe et al. Citation2008). In fact, a quick stroll outside of such normative assumptions would consider authoritarian propaganda as a call to engagement. In this respect, negative, or “dark participation” (Quandt Citation2018) is an equally valid and oftentimes highly “successful” form of engagement, albeit one that happens to carry negative values and harmful outcomes. Criticism and harassment online, for example, are clear signs of behavioural and emotional engagement. To address this normative conundrum, Hill (Citation2019) proposes a spectrum of engagement where the distinction between positive and negative forms of engagement is fluid, often difficult to demarcate. Similarly, Corner (Citation2017:, 2) argues there are different levels of engagement “ranging from intensive commitment through to a cool willingness to be temporarily distracted right through finally to vigorous dislike”. Thus, engagement in itself should be thought of as the enactment of agency, where audiences are able to identify behavioural and emotional regularities as norms and to decide, with varying degrees of awareness, whether or not to act within the contours of the normative standard.

Aligning the behavioural, emotional, and normative dimensions of engagement is often an elusive proposition. For instance, developments in news production and consumption that have promoted the emotional dimension of audience engagement have sometimes had the opposite effect on the normative dimension. More concretely, an increased emphasis on human interest stories and other softer feature genres boosted emotional engagement with news and made journalism popular to a broader public (Hughes Citation1981; Steensen Citation2018). However, the same genres have also been ridiculed and mocked for rendering journalism unimportant and irrelevant for the production of civic engagement and interest in public affairs (e.g., Franklin Citation1997). Such critique presupposes that “proper” journalism is supposed to be distanced, objective and fact-oriented in order to boost the kind of (positive) engagement that serves a democratic ideal (Benson Citation2008), and that emotionally engaging news can corrupt this alleged positive engagement. In deliberative democratic theory, which “lacks an account of affectivity” (Hoggett and Thompson Citation2002, 107), rationality is a virtue and emotional engagement is often neglected or rendered dubious and might therefore be viewed as something which obscures “good” engagement. The behavioural, emotional and normative dimensions of audience engagement are therefore involved in complex relationships, which might be evaluated differently depending on how one ascribes value to the public sphere and the spatiotemporal contexts in which they occur.

The Spatiotemporal Dimension of Audience Engagement

While metrics capture acts of engagement that occur at a specific place and time, and thereby only the processes/actions category of interactivity identified by McMillan (Citation2005, Citation2019), the spatiotemporal conditions of audience engagement generally transcend the significance of the discrete moment being measured. For instance, it has long been recognized in journalism that the spatiotemporal proximity of a news event tends to greatly impact public interest in it (Tuchman Citation1978). Furthermore, moments of engagement, not just for journalism but with most forms of media, tend to be interwoven within the routines and flows of daily life; one can think of examples from reading news during the daily commute, to scanning social media during “in between” moments, to sitting down in the evening to binge watch a favoured TV serial, and many more. In other words, while patterns of engagement can surely be detected from capturing and linking the spatiotemporal characteristics of each particular case, what tends to make such acts of engagement with media meaningful are how they relate to other structures, practices, and social interactions in everyday life. The social aspect of engagement is therefore closely connected with the spatiotemporal dimension, as this dimension accounts for the relational aspects of engagement between people across time and space.

Engagement, in this regard, is difficult to capture in terms of its spatiotemporal complexities. Memory, for instance, is a social, emotional form of engagement that occurs at non-linear space-times (Zelizer and Tenenboim-Weinblatt Citation2014), while habit is an autonomous, individual behavioural form of engagement that tends to follow strict spatiotemporal patterns (Peters and Schrøder Citation2018). Moreover, engagement is not only something shaped in certain spaces and across certain times—the inverse is also the case. Engagement conditions how space–time itself is experienced. To give but a few examples, engagement with the news has been shown to: help define generations and elicit their history (Zelizer and Tenenboim-Weinblatt Citation2014); engender feelings of societal stasis (nothing ever changes) or radical change (everything does) (Keightley and Downey Citation2018); and shape feelings of safety or threat in particular regions or places (Romer, Jamieson, and Aday Citation2003). In other words, the spatiotemporal dimension of engagement is central to a comprehensive appreciation of how audiences experience this. Acknowledging this spatiotemporal dimension of audience engagement encourages a shift from conceptualizing it as something that comes into being at precisely the moment and place it can be measured to instead consider more sustained patterns of media use. Such a shift corresponds with recent trends within audience studies and what Alasuutari (Citation1999) recognized as the “third wave of audience research”, which moved away from the behavioural paradigm to study media use against the fabric of everyday life.

Considering the spatiotemporal dimension of engagement thus allows us to draw connections between audience engagement and longer, historical trends and developments in modes of news production and consumption. The “time spent” metric, which most news organizations use to assess how readers engage with the news (Groot Kormelink and Costera Meijer Citation2020) fails to measure when users start thinking about the news, what feelings prompted them to seek it out, which identities and social relations shaped their interpretation of it, the emotions that consumption evoked and, perhaps most importantly, the time that sentiments and understanding linger as readers ponder and maybe discuss the news with others.

In sum: such is the problem of engagement. As the spatiotemporal and other three dimensions we outline above indicate, “optimal measurement” of engagement is an oxymoron, because measuring all four dimensions of engagement is unattainable. And yet, this is still the objective of news organizations worldwide and much related scholarship on engagement. We understand why quantification has led to this situation, but it is this almost wholesale acceptance of industry terminology that simplifies and fails to recognize the social complexity of such a concept. A reductionist approach based on measurable traces may help to understand individual dimensions of engagement, but further solidifies the notion that engagement is primarily behavioural and quantifiable. Instead, we believe that assembling a model of audience engagement that embraces the immeasurable—based on the aforementioned four dimensions—confronts the complexity of the concept more holistically. Ironically, it also brings to the fore the impossibility of reaching a complete and general understanding of all aspects of audience engagement.

A Model of Audience Engagement (And How It Falls Apart)

The four dimensions of audience engagement discussed above are by no means mutually exclusive. Most instances of audience engagement with media will involve some technical-behavioural aspects, elicit degrees of emotional intensity, embody normative implications or presuppositions, and connect with spatiotemporal contexts. Bolin and Velkova’s (Citation2020) experimental study of Facebook users who were exposed to the Facebook Demetricator plugin (created by associate professor Ben Grosser at the University of Illinois), which removes representational metrics (timestamps, number of likes, shares, comments and so on) from Facebook posts, demonstrates this connection between the four dimensions. First, removing timestamps created emotional distress and confusion among the Facebook users concerning how to engage with pieces of information. Second, removing the number of likes, shares, comments and so on made apparent that such metrics are essential for “crafting the experience of sociality” (9) and for determining the value of content. In other words; removing technical-behavioural aspects had an impact on the emotional, spatiotemporal and normative dimensions of engagement. Hence, each dimension is more aptly conceived of as highlighting pivotal aspects of audience engagement, which thereby facilitates and clarifies analysis of relative magnitude and respective significance. Taking this a step further, in terms of journalism scholarship, the next step is then to identify the central (mediated) contexts that shape key questions of impact for the particular research inquiry, specify the relationships and practices therein that influence engagement and, finally, clarify scope to design (multi-method) research approaches that are able to tackle them.

By way of example, below builds upon the four dimensions to develop a conceptual model of audience engagement with news and other media content which identifies and explicates key features across a number of relational contexts central to its enactment. These relations, inspired by McMillan’s (Citation2005) previously discussed model of interactivity, augment her account by adding “human-to-self” and “machine-to-machine” as relevant relations, and replace “computer” in McMillan’s model with “machine” to more broadly account for all technologies that might be involved in media consumption. The human-to-self relation is important, because it makes apparent that engagement always implies a subjective experience with media, in which past and present are connected and relate to sensory, subjective neuro-technical processes as well as wider socio-cultural contexts and emotions. These connections, in turn, allow individuals to ascribe meaning and value to media. The “machine-to-machine” relation is equally important because it accounts for increasingly ubiquitous automated production and distribution processes, and exchanges of information facilitated by “smart” media technologies and algorithms, that happen between audiences, media and tech companies, and other institutions, without the audience knowing about it (Kammer Citation2018). Such processes of datafication are not only technological-behavioural mechanisms, they also have emotional, spatiotemporal and normative implications (Kitchin Citation2014), which are important for understanding both the economic value (Nelson and Webster Citation2016) and sociopolitical impacts (Dencik, Hintz, and Cable Citation2016) of audience engagement.

It is essential to note that the bullet points offered in are not intended to be interpreted as unique and exhaustive “types” of engagement but rather as marked examples of the sorts of diverse, interrelated features, processes and perceptions that are potentially germane to operationalize in research. While it is impossible to capture all elements in a single design, helps facilitate reflection on the conceptual prioritizations different choices in the research process afford and restrict, which heavily shapes our empirical understandings of why audiences engage with media, how it happens and, to some extent, why it matters. The table accordingly explicates what a more holistic accounting of audience engagement might attend to, when viewed not only from the behavioural paradigm but also from the individual audience member’s point of view, and augments this to also account for machine-to-machine relations.

could be expanded with other relations that go beyond the individual audience member, for instance “machine-to-company”, “machine-to-cloud network”, “machine-to-media producer” and “company-to-society”. Furthermore, infusing these relations with a social component that recognizes the amplification effects that groups have on engagement might be helpful to clarify that engagement is predominantly a communicative social phenomenon. The table is therefore not a complete overview of all aspects related to audience engagement—it is restricted to the direct relations involving individual members of an audience. And it is an overview in which engagement is predominantly understood and theorized from an audience perspective. Alternatively, if we were to take a media industry perspective on audience engagement, it is obvious that —and our whole discussion in the previous sections, for that matter—would greatly underestimate the importance of engagement as a commodity good (Corner Citation2017).

Moreover, does not account for the overlapping dynamics between the four dimensions. They are related in a myriad of possible ways, which renders impossible any attempt at creating a “totalizing” or “grand” theory that encompasses them all. Acknowledging this leaves us precisely at the point at which Knapp and Michaels (Citation1982) found that theorizing is pointless. As argued in their foundational article “Against Theory”; theory seems possible or relevant only “when theorists fail to recognize the fundamental inseparability of the elements involved” (Citation1982, 724), as we do here. Therefore—and as the title of this article suggests—our theory of audience engagement with news is as much an argument against a theory of audience engagement. However, even if we believe a closed theory of audience engagement might be both impractical and impossible, we argue that proposing these four building blocks of engagement, and the ways in which they align with various relations involved in engagement, have real-life implications for scholars interested in the concept and its attendant complexities and impacts.

Implications for Research

An important argument of this article is that the trend toward embracing, or at least acquiescing to, metrics-oriented discourse on audience engagement, both within industry and research, is somewhat short-sighted. If it continues unchecked, we risk hollowing the complexity of the concept out. But how then to change course, to methodologically address multiple dimensions of audience engagement with news in empirical research? While full operationalizations are specific to each research goal, and therefore beyond this article’s remit, one can translate our discussion to this point into common premises for doing media and communication research into audience engagement, namely:

Premise #1: Researching engagement necessitates operationalizing emotion. In studies of journalism qualitative approaches could probe how, and to what extent, news flows encourage people to actualize previous affective sentiments (Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2019), and find within such spheres an emotional potentiality to experience some aspect of society, and potentially even change it. Consequently, researchers aiming at exploring the emotional dimension of engagement could benefit from moving beyond the behavioural paradigm and tap into the discussions on methodological innovation within the sociology of emotions (Olson, Godbold, and Patulny Citation2015) and within advertising research (Poels and Dewitte Citation2006). In addition, research within human computer interaction studies has demonstrated important connections between the technical-behavioural dimension and the other dimensions, for instance in how mouse cursor movement can signal emotional engagement (Hibbeln et al. Citation2017).

Premise #2: Researching engagement means questioning normative assumptions. The overarching assumption in journalism studies as in many other fields of media and communication research is that more engagement—be it voting, buying products, or reading news—is positive. Trolling, harassment, and other forms of “dark participation” (Quandt Citation2018), are forms of negative engagement that demand comparable communicative recognition. Moreover, questions of identity are often ignored when considering structural reasons that establish the normative frameworks of engagement. In US journalism, for instance, a willingness to engage around discussions of race in the news is strongly influenced by experiences of privilege (Robinson Citation2017). Such normative considerations are crucial when one considers that research has shown that metrics push news workers to make editorial decisions that maximize KPIs of engagement and extend their use (Ferrer-Conill and Tandoc Citation2018). As established debates around reflexivity remind us (Mauthner and Doucet Citation2003), what constitutes positive engagement and why, is not only a question of methodology but of normative presuppositions.

Premise #3: Researching engagement demands contextual sensitivity to space and time. Measuring acts of audience engagement, through metrics, network analytics and other established approaches, often demands start and end points. While bracketing the object of analysis, and identifying the appropriate population and sample are necessary in communication research, it is important to remind ourselves that the experience of engagement generally escapes these spatiotemporal limitations of methods. Engagement is not merely a reactive pattern of behaviours related to distinct events. In journalism, the development of news repertoires rely on sustained patterns of engagement that incorporate longer, historical trends over time and place (Peters and Schrøder Citation2018). Complexifying research instruments into engagement could be aided by considering designs that incorporate insights from memory studies, human geography and related fields (Keightley and Downey Citation2018).

These premises, while not exhaustive, offer a useful baseline for research designs, one which: avoids an uncritical adoption of the industry discourse on audience engagement with news; acknowledges the complexity of the concept in its varied dimensions; and operationalizes key features by crafting multi-method, qualitative and quantitative designs that go beyond viewing engagement principally in terms of acts that leave digital traces. It is our hope that the model of audience engagement we have presented in this article (see ) can serve as a methodological guideline concerning which relations and dimensions of audience engagement one should consider, and consequently which methods to potentially use, when designing a research project on audience engagement. This, in turn, would hopefully lead to research in audience engagement which recognizes the limits of what audience metrics and the behavioural paradigm can tell us, and augments such data with data acquired through complementary methods.

Conclusion

Our argument towards a broad conceptualization of audience engagement proposes three major conclusions. First, engagement is a multidimensional phenomenon that carries dynamics rooted in technical-behavioural, emotional, normative, and spatiotemporal dimensions. Thus, attempts to study audience engagement only from the standpoint of the technical-behavioural dimension fail to capture the full spectrum of audience engagement. Second, the relations of audience engagement incorporate an intricate array of interactions between human and non-human actors. This further complicates the formation, trajectories, and dissipation of specific instances of audience engagement. Finally, the formulation of a single universal theory of audience engagement, appealing as it may be, seems to pose insurmountable challenges and complexities. Our approach to theorizing audience engagement is therefore a social-constructivist one, in which social and cultural contexts, subjective perspectives and experiences, individual variances and spatiotemporal elements construct types of engagement beyond what a single theory can encompass. As such, our approach to theorizing audience engagement aligns with Livingstone’s recent reflections on audience studies:

[A]udiences are necessarily social, embedded in society and history in many more ways than through their relation with the media, so the critical analysis of audiences cannot be satisfied with sporadic inclusion of disembodied, decontextualized observations of behavior or cherry-picked survey percentages but must engage with audiences meaningfully in and across the contexts of their lives. (Citation2019, 179)

We believe our proposed theory of audience engagement (and the arguments against it) has merit beyond the sphere of news and journalism. Even though we acknowledge there are different cultures and logics connected with different media, platforms and contexts in which audiences operate, we believe that the four dimensions of audience engagement developed in this article are relevant for studying anything from communicative engagement with music, film, literature and reality tv-shows, to social media posts, public affairs and marketing campaigns, and beyond. We may not be able to propose a “grand theory” of audience engagement, but by developing a more comprehensive way of thinking about the concept, we hope this article encourages further explorations of engagement “in the wild”. For that reason, we have also proposed a set of premises to help transcend from abstract theoretical building blocks into approaches that can guide empirical research. In this way, it is our hope that by articulating a framework—simultaneously for and against a theory of audience engagement—future research will continue to problematize and clarify the concept, and thus move beyond analysis decreed by metrics-based fiat.

Acknowledgments

Earlier versions of this paper were presented to research groups at OsloMet and Karlstad University, as well as at the Future of Journalism and ICA 2020 conferences. We thank numerous colleagues for their helpful feedback at various stages. Special thanks go to Michael Karlsson and Matt Carlson for detailed feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alasuutari, P. 1999. Rethinking the Media Audience: The New Agenda. London, Thousand Oaks, and New Delhi: Sage publications.

- American Press Institute. 2019. “Metrics and Measurement.” Accessed October 21, 2019. https://www.americanpressinstitute.org/topics/metrics-and-measurement/.

- Barbalet, J. M. 2001. Emotion, Social Theory, and Social Structure: A Macrosociological Approach. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Batsell, J. 2015. Engaged Journalism: Connecting with Digitally Empowered News Audiences. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Belair-Gagnon, V., and A. E. Holton. 2018. “Boundary Work, Interloper Media, And Analytics In Newsrooms.” Digital Journalism 6: 492–508.

- Belair-Gagnon, V., J. L. Nelson, and S. C. Lewis. 2019. “Audience Engagement, Reciprocity, and the Pursuit of Community Connectedness in Public Media Journalism.” Journalism Practice 13: 558–575. doi:10.1080/17512786.2018.1542975.

- Benson, R. 2008. “Journalism: Normative Theories.” In The International Encyclopedia of Communication, edited by W. Donsbach. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/9781405186407.wbiecj007.

- Boeckmann, R. J., and T. R. Tyler. 2002. “Trust, Respect, and the Psychology of Political Engagement.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 32: 2067–2088. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb02064.x.

- Bolin, G., and J. Velkova. 2020. “Audience-metric Continuity? Approaching the Meaning of Measurement in the Digital Everyday.” Media, Culture & Society, 0163443720907017. doi:10.1177/0163443720907017.

- Broersma, M. 2019. “Audience Engagement.” In The International Encyclopedia of Journalism Studies, edited by T. P. Vos, F. Hanusch, and D. Dimitrakopoulou, et al. Wiley. doi:10.1002/9781118841570.

- Chen, Gina Masullo, Paromita Pain, Victoria Y Chen, Madlin Mekelburg, Nina Springer, and Franziska Troger. 2018. “‘You Really Have to Have a Thick Skin’: A Cross-Cultural Perspective on how Online Harassment Influences Female Journalists.” Journalism, doi:10.1177/1464884918768500.

- Cherubini, F., and R. K. Nielsen. 2016. Editorial Analytics: How News Media are Developing and Using Audience Data and Metrics. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Chua, S., and O. Westlund. 2019. “Audience-centric Engagement, Collaboration Culture and Platform Counterbalancing: A Longitudinal Study of Ongoing Sensemaking of Emerging Technologies.” Media and Communication 7: 153–165. doi:10.17645/mac.v7i1.1760.

- Coddington, M. 2015. “Clarifying Journalism’s Quantitative Turn.” Digital Journalism 3: 331–348. doi:10.1080/21670811.2014.976400.

- Corner, J. 2017. “Afterword: Reflections on Media Engagement.” Media Industries Journal 4 (1). doi:10.3998/mij.15031809.0004.109.

- Couldry, N., S. Livingstone, and T. Markham. 2010. Media Consumption and Public Engagement: Beyond the Presumption of Attention. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Dahlgren, P. 2009. Media and Political Engagement: Citizens, Communication, and Democracy. Communication, Society and Politics. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Dencik, L., A. Hintz, and J. Cable. 2016. “Towards Data Justice? The Ambiguity of Anti-Surveillance Resistance in Political Activism.” Big Data & Society 3 (2). doi:10.1177/2053951716679678.

- Espeland, W. N., and M. L. Stevens. 2008. “A Sociology of Quantification.” European Journal of Sociology 49: 401–436. doi:10.1017/S0003975609000150.

- Ferrer-Conill, R. 2017. “Quantifying Journalism? A Study on the Use of Data and Gamification to Motivate Journalists.” Television & New Media 18: 706–720. doi:10.1177/1527476417697271.

- Ferrer-Conill, R., and E. C. Tandoc Jr. 2018. “The Audience-Oriented Editor.” Digital Journalism 6: 436–453. doi:10.1080/21670811.2018.1440972.

- Franklin, B. 1997. Newszak and News Media. London: Arnold.

- Gastil, J., and M. Xenos. 2010. “Of Attitudes and Engagement: Clarifying the Reciprocal Relationship Between Civic Attitudes and Political Participation.” Journal of Communication 60: 318–343. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2010.01484.x.

- Groot Kormelink, T., and I. Costera Meijer. 2020. “A User Perspective on Time Spent: Temporal Experiences of Everyday News use.” Journalism Studies 21: 271–286. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2019.1639538.

- Haim, M., A. S. Kümpel, and H.-B. Brosius. 2018. “Popularity Cues in Online Media: A Review of Conceptualizations, Operationalizations, and General Effects.” Studies in Communication | Media 7 (2): 186–207. doi:10.5771/2192-4007-2018-2-58.

- Hall, S. 1973. “Encoding and Decoding in the Television Discourse." Paper for the Council Of Europe Colloquium on "Training In The Critical Reading Of Televisual Language". Organized by the Council & the Centre for Mass Communication Research, September, Leicester, UK: University of Leicester

- Hibbeln, M. T., J. L. Jenkins, C. Schneider, Joseph Valacich, Markus Weinmann. 2017. How Is Your User Feeling? Inferring Emotion Through Human-Computer Interaction Devices. ID 2708108, SSRN Scholarly Paper. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. Accessed March 21, 2020. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2708108.

- Hill, A. 2019. Media Experiences: Engaging with Drama and Reality Television. London and New York: Routledge.

- Hoggett, P., and S. Thompson. 2002. “Toward a Democracy of the Emotions.” Constellations (Oxford, England) 9 (1): 106–126. doi:10.1111/1467-8675.00269.

- Hughes, H. M. 1981. News and the Human Interest Story. Reprint, Originally Published by University of Chicago Press in 1940. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

- Kammer, A. 2018. “Resources Exchanges and Data Flows Between News Apps and Third Party Actors: The Digitizaion of the News Industry.” In: 68th Annual ICA Conference, Prague, 24 May 2018.

- Keightley, E., and J. Downey. 2018. “The Intermediate Time of News Consumption.” Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 19 (1): 93–110.

- Kitchin, R. 2014. “Big Data, New Epistemologies and Paradigm Shifts.” Big Data & Society 1 (1). doi:10.1177/2053951714528481.

- Knapp, S., and W. B. Michaels. 1982. “Against Theory.” Critical Inquiry 8 (4): 723–742.

- Ksiazek, T. B., L. Peer, and K. Lessard. 2014. “User Engagement with Online News: Conceptualizing Interactivity and Exploring the Relationship Between Online News Videos and User Comments.” New Media & Society 18: 502–520. doi:10.1177/1461444814545073.

- Lawrence, R. G., D. Radcliffe, and T. R. Schmidt. 2018. “Practicing Engagement.” Journalism Practice 12 (10): 1220–1240. doi:10.1080/17512786.2017.1391712.

- Lewis, J., S. Inthorn, and K. Wahl-Jorgensen. 2005. Citizens or Consumers?: What the Media Tell Us about Political Participation. Maidenhead, UK: Open University Press.

- Livingstone, S. 2019. “Audiences in an Age of Datafication: Critical Questions for Media Research.” Television & New Media 20 (2): 170–183. doi:10.1177/1527476418811118.

- Manovich, L. 2018. “Digital Traces in Context| 100 Billion Data Rows per Second: Media Analytics in the Early 21st Century.” International Journal of Communication 12: 473–488.

- Mauthner, N. S., and A. Doucet. 2003. “Reflexive Accounts and Accounts of Reflexivity in Qualitative Data Analysis.” Sociology 37 (3): 413–431.

- McMillan, S. J. 2005. “The Researchers and the Concept.” Journal of Interactive Advertising 5 (2): 1–4.

- McMillan, S. J. 2019. “Interactive Advertising: Untangling the Web of Definitions, Domains, and Approaches to Interactive Advertising Scholarship from 2002–2017.” In Advertising Theory. 2nd ed., edited by S. Rodgers, and E. Thorson. New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781351208314-28.

- Meier, K., D. Kraus, and E. Michaeler. 2018. “Audience Engagement in a Post-Truth Age.” Digital Journalism 6 (8): 1052–1063. doi:10.1080/21670811.2018.1498295.

- Napoli, P. M. 2003. Audience Economics: Media Institutions and the Audience Marketplace. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Nelson, J. L. 2018. “The Elusive Engagement Metric.” Digital Journalism 6 (4): 528–544. doi:10.1080/21670811.2018.1445000.

- Nelson, J. L. 2019. “The Next Media Regime: The Pursuit of ‘Audience Engagement’ in Journalism.” Journalism, 1464884919862375. doi:10.1177/1464884919862375.

- Nelson, J. L., and E. C. Tandoc Jr. 2019. “Doing “Well” or Doing “Good”: What Audience Analytics Reveal About Journalism’s Competing Goals.” Journalism Studies 20 (13): 1960–1976. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2018.1547122.

- Nelson, J. L., and J. G. Webster. 2016. “Audience Currencies in the Age of Big Data.” International Journal on Media Management 18 (1): 9–24. doi:10.1080/14241277.2016.1166430.

- Olson, R., N. Godbold, and R. Patulny. 2015. “Introduction: Methodological Innovations in the Sociology of Emotions Part Two – Methods.” Emotion Review 7 (2): 143–144. doi:10.1177/1754073914555276.

- Papacharissi, Z. 2015. Affective Publics: Sentiment, Technology, and Politics. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Peters, C. 2011. “Emotion Aside or Emotional Side? Crafting an ‘Experience of Involvement’ in the News.” Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 12 (3): 297–316. doi:10.1177/1464884910388224.

- Peters, C., and K. C. Schrøder. 2018. “Beyond the Here and Now of News Audiences: A Process-Based Framework for Investigating News Repertoires.” Journal of Communication 68 (6): 1079–1103. doi:10.1093/joc/jqy060.

- Picone, Ike, Jelena Kleut, Tereza Pavlíčková, Bojana Romic, Jannie Møller Hartley, and Sander De Ridder. 2019. “Small Acts of Engagement: Reconnecting Productive Audience Practices with Everyday Agency.” New Media & Society 21 (9): 2010–2028. doi:10.1177/1461444819837569.

- Poels, K., and S. Dewitte. 2006. “How to Capture the Heart? Reviewing 20 Years of Emotion Measurement in Advertising.” Journal of Advertising Research 46 (1): 18–37. doi:10.2501/S0021849906060041.

- Quandt, T. 2018. “Dark Participation.” Media and Communication 6 (4): 36–48. doi:10.17645/mac.v6i4.1519.

- Robinson, S. 2017. Networked News, Racial Divides: How Power and Privilege Shape Public Discourse in Progressive Communities. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Romer, D., K. H. Jamieson, and S. Aday. 2003. “Television News and the Cultivation of Fear of Crime.” Journal of Communication 53 (1): 88–104. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2003.tb03007.x.

- Rowe, Gene, Tom Horlick-Jones, John Walls, Wouter Poortinga, and Nick F. Pidgeon. 2008. “Analysis of a Normative Framework for Evaluating Public Engagement Exercises: Reliability, Validity and Limitations.” Public Understanding of Science 17 (4): 419–441. doi:10.1177/0963662506075351.

- Skoric, Marko M, Qinfeng Zhu, Debbie Goh, and Natalie Pang. 2016. “Social Media and Citizen Engagement: A Meta-Analytic Review.” New Media & Society 18 (9): 1817–1839. doi:10.1177/1461444815616221.

- Steensen, S. 2017. “Subjectivity as a Journalistic Ideal.” In Putting a Face on It: Individual Expose and Subjectivity in Journalism, edited by B. K. Fonn, H. Hornmoen, and N. Hyde-Clarke, et al., 25–47. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Academic Press.

- Steensen, S. 2018. Feature Journalism. Oxford, UK: Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.810.

- Stumpf, S. A., W. G. Tymon, and N. H. M. van Dam. 2013. “Felt and Behavioral Engagement in Workgroups of Professionals.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 83 (3): 255–264. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2013.05.006.

- Su, Leona Yi-Fan, Michael A Xenos, Kathleen M Rose, Christopher Wirz, Dietram A Scheufele, Dominique Brossard, et al. 2018. “Uncivil and Personal? Comparing Patterns of Incivility in Comments on the Facebook Pages of News Outlets.” New Media & Society 20 (10): 3678–3699. doi:10.1177/1461444818757205.

- Swart, J., C. Peters, and M. Broersma. 2018. “Shedding Light on the Dark Social: The Connective Role of News and Journalism in Social Media Communities.” New Media & Society 20 (11): 4329–4345.

- Tandoc Jr, E. C. 2015. “Why Web Analytics Click.” Journalism Studies 16 (6): 782–799. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2014.946309.

- Tandoc, E. C. 2019. Analyzing Analytics : Disrupting Journalism One Click at a Time. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781138496538.

- Taplin, J. 2017. Move Fast and Break Things: How Facebook, Google, and Amazon Have Cornered Culture and What It Means For All Of Us. Basingstoke, UK: Pan Macmillan.

- Tuchman, G. 1978. “The News Net.” Social Research 45 (2): 253–276.

- Wahl-Jorgensen, K. 2019. Emotions, Media and Politics. Oxford, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- Ytre-Arne, B., and H. Moe. 2018. “Approximately Informed, Occasionally Monitorial? Reconsidering Normative Citizen Ideals.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 23 (2): 227–246. doi:10.1177/1940161218771903.

- Zamith, R., V. Belair-Gagnon, and S. C. Lewis. 2019. “Constructing Audience Quantification: Social Influences and the Development of Norms About Audience Analytics and Metrics.” New Media & Society. doi:10.1177/1461444819881735.

- Zelizer, B., and K. Tenenboim-Weinblatt. 2014. Journalism and Memory. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Zeng, Z., M. Pantic, G. I. Roisman, T. S. Huang. 2009. “A Survey of Affect Recognition Methods: Audio, Visual, and Spontaneous Expressions.” IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 31 (1): 39–58. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2008.52.