ABSTRACT

Technological disruptions and increasing competition in the digital mediascape have fundamentally altered the market conditions for news media companies, raising corresponding concerns about the future of journalism. News media firms can adapt their business models by more purposefully focusing on media innovation, or the development and implementation of new processes, products or services. Specifically, this article focuses on innovation-centric coordination and collaboration—namely, coordination of knowledge and innovation activities among social actors in news media organizations. In doing so, this article builds on the knowledge-based view (KBV) of the firm and its core argument that coordination of knowledge is essential for organizational innovation. It presents findings from a series of cross-sectional surveys with newspaper executives carried out bi-annually from 2011 to 2017, examining executives’ perceptions of collaborative potential for digital media innovation at the intersection of editorial, business, and information technology (IT) departments. The findings suggest that there has been a significant increase in perceived collaboration more recently, and that the IT department is perceived to have become more important to innovation over time.

Introduction

This article builds on a simple formula—introduced briefly here and explained more fully below—that reveals important insights about the role of knowledge in a news media business enterprise: In the context of heightened market-based Competition (A) and the need for firm-initiated Change (B) in response, Coordination and Collaboration (C)—particularly within a media firm and across its editorial, business, and information technology teams—are essential knowledge-sharing conditions for fostering and furthering digital media innovation.

Ongoing technological disruptions and increasing Competition (A) in the digital mediascape have fundamentally changed the market situation for news media companies, raising concerns about the future sustainability of journalism and its practice in many parts of the world. Such external forces indeed influence journalism and those who oversee its production—from publishing companies to their executives to their media workers. However, these social actors should not be seen as passively being affected, as they also have agency to influence their situation and future. News publishers can Change (B) in diverse ways, such as by intervening or responding through an adaptation of business models or cutting costs. They can also develop and implement digital media products and services associated with journalism and news work. Industry representatives in Scandinavia often talk about this as working with “new media,” which is part of their language for describing digital developments and innovation. This includes more purposefully focusing on media innovation, which refers to developing and implementing new media-related processes, products or services (Storsul and Krumsvik Citation2013). Many industries work under the assumption that innovation is critical for maintain relevance in the market, and the news industry is no exception, where change has produced many opportunities (Picard Citation2014). Research shows that media executives perceive innovation as crucially important and often believe that they can manage it with the expertise they have inside the organization (Appelgren & Nygren Citation2019). The journalism sector is marked by a is a pro-innovation bias (Steensen and Westlund Citation2020), and innovation clearly cannot solve all problems. In approaching media innovation, news organizations most likely have to enlist diverse specialists throughout their organization in Coordination (C). This involves media workers (Deuze Citation2007) coordinating with each other across departments in working toward shared organizational goals—a far cry from some managerial approaches (common in the past) that separate members into distinct functional units and discourage them from communicating with each other. A recent Dutch survey with two news organizations found that “shared goals” was perceived as most important when it comes to fostering innovative learning cultures (Porcu, Hermans, and Broersma Citation2020), and a recent Finnish study found that a psychologically safe communication climate (PSCC) as well as intentional idea sharing and development habits were important to innovation (Koivula, Villi, and Sivunen Citation2020). Coordination of media work may include only limited cross-departmental communication by media workers who otherwise remain distant from one another; nevertheless, such efforts may also result in closer engagement across boundaries and thus generate a sort of Collaboration. In this article, we treat these two concepts, coordination and collaboration, as distinct yet related.

There are a great number of reports into what sorts of innovations executives and managers think are important, produced by World Association of Newspapers (WAN-IFRA), the International News Media Association (INMA) and Global Editors Network (GEN), including studies by scholarly researchers as well. There are also many studies into how journalists and newsrooms resist, alternatively embrace, appropriate, and normalize innovations and digital media (García-Avilés et al. Citation2018). How news organizations have approached the intra-organizational dynamics of media innovation, however, remains an open question. Particularly unclear is how people or departments with specialized knowledge inside the organization each contribute, or are perceived to contribute, relative to one another. This article offers an analysis of such patterns over time among media workers, from the viewpoint of newspaper executives. Ultimately, while this is a study of executives’ perceptions, its focus lies with their perceptions about participation and coordination among media workers.

Our study into coordination and innovation is relevant for journalistic work, as news organizations increasingly seek to develop new practices in ways that require coordinating expertise within the newsroom as well as across teams and units (e.g., Cueva Chacón and Saldaña Citation2020; Koivula, Villi, and Sivunen Citation2020). Importantly though, coordination practices vary with different types of journalism. Breaking news, for example, is sometimes carried out autonomously and efficiently from the online desk, while at other times requiring intense coordination amongst diverse social actors (Ekström, Ramsälv, and Westlund Citation2020). Recent studies have pointed to changing dynamics between journalists, on the one hand, and technologists and businesspeople, on the other. Hereafter we will use media workers as an umbrella concept referring to these professionals (cf. Deuze Citation2007). Such research suggests an ongoing shift from a state of separation to one of collaboration (e.g., Cornia, Sehl, and Nielsen Citation2018; Drew & Thomas Citation2018) and goes in concert with similar developments that were emerging roughly a decade ago, when technologists began to assume a growing role in news organizations (Nielsen Citation2012; Westlund Citation2011) and indeed in the journalism field more broadly (Lewis and Usher Citation2013; Lewis and Usher Citation2016; Lewis and Zamith Citation2017). There is a growing line of research into such intra-organizational collaboration (Lewis and Westlund Citation2015) as well as inter-organizational collaboration (Konieczna Citation2020), including as it occurs across countries (Cueva Chacón and Saldaña Citation2020). This article, however, focuses exclusively on the intra-organizational dimension.

In a similar vein, scholars recently have called for research on digital journalism to account for a greater variety of actors claiming a journalistic belonging (Belair-Gagnon, Holton, and Westlund Citation2019; Eldridge Citation2017, Citation2018; Schapals, Maares, and Hanusch Citation2019). Among these are “strangers to the profession” such as amateur journalists, mobile app designers, and web analytics managers (Holton and Belair-Gagnon Citation2018) as well as foundation funders of citizen bloggers producing news alongside or in close collaboration with news publishers (Ostertag and Tuchman Citation2012). Foundation funders may influence the character of journalistic autonomy and also lead to journalists being required to handle non-editorial tasks (Scott, Bunce, and Wright Citation2019). Indeed, it is important to acknowledge a plethora of entrants into the journalistic field, as in the case of venture-backed news startups (Usher Citation2017). Some external actors, such as data- and fact-checking organizations, may operate with journalistic goals, albeit without working within a news media institution (Cheruiyot and Ferrer-Conill Citation2018). Then there are other external actors, such as analytics companies, that introduce metrics that disrupt news production routines—and yet they refrain from assuming journalistic responsibility (Belair-Gagnon and Holton Citation2018). Moreover, Lowrey and colleagues (Citation2019) conclude that “ancillary” organizations, such as foundations and professional associations (e.g., WAN-IFRA), may function as agents of innovation (see also Lewis Citation2012).

Towards Coordination and Collaboration

In this article, we build upon Lewis and Westlund (Citation2015) in arguing that internally to the news organization there is a wide ensemble of social actors, principally businesspeople and technologists in addition to journalists. However, existing literature in journalism studies, and also research in media management and media innovation, has done little to systematically explore and explain how different social actors in news organizations coordinate and collaborate with each other—that is, how various groups, in relative and comparative ways, act in coordination (or not) in carrying out the firm’s goals. Thus, in the broader context of Competition (A) and Change (B), this article focuses on Coordination and Collaboration (C) as manifest in the pursuit of media innovation. The article discusses media innovation and the broader concept of innovation, but our study focuses more specifically how the media have approached innovation in the salient case of “new media.” In the context of the Norwegian media industry, both executives and media workers have referred to “new media” in discussions of digital media.

Coordination may lead to and go hand-in-hand with collaboration, but members of organizations also may coordinate (synchronizing activities) while experiencing tensions that keep them from collaborating (productively working together). A number of single-site case studies point to the generative potential for cross-departmental collaboration, primarily among journalists, businesspeople, and technologists (e.g., Baack Citation2018; Drew and Thomas Citation2018; Nielsen Citation2012; Westlund Citation2011). A cross-national interview study in six European countries provides insights into contemporary norms about separation and collaboration (Cornia, Sehl, and Nielsen Citation2018). Moreover, public service media (PSM), for example, are experiencing pressures to organize for newsroom integration. The authors conclude that few PSM have accomplished this to date, yet they see this as necessary to work efficiently across platforms (Sehl et al. Citation2018). Coordination is also important for media innovation. Consider this quote from a Spanish news innovator, from a study by García-Avilés et al. (Citation2018, 9): “‘It’s not a question of everybody being an expert in design, but you do need to know the basics to understand the limitations and which things work and which don’t.’” García-Avilés and colleagues further discuss the prevalence of horizontal decision-making, and how communication technologies such as Telegram and Slack are being used in routine everyday work as a means of knowledge coordination.

While there are numerous such studies to date, research has yet to clarify the perceptions of executives across the industry within a given country. This article takes up that question by exploring how news media executives perceive opportunities for intra-organizational coordination and collaboration among different types of social actors in their firms. In the news industry historically, both coordination and collaboration—for example, between Editorial and Marketing departments, or Marketing and Information Technology (IT), or all three together—have been the exception rather than the rule, for functional reasons and because of normative concerns about preserving journalistic autonomy (e.g., Achtenhagen and Raviola Citation2009; Coddington Citation2015; Djerf-Pierre and Weibull Citation2011; Drew and Thomas Citation2018; Nielsen Citation2012). Research about editorial leaders in Sweden have found that they have begun embracing managerialism (Andersson & Wiik, Citation2013), and more recent research from Sweden show that the managers and managerialism have been gaining traction in news organizations, giving greater weight to efficiency and business performance, in contrast to journalistic practice and editorial processes (Waldenström, Wiik, and Andersson Citation2018). Indeed, such bureaucratic “silos” may have suited a period of relatively stable, routinized, and profitable news production, like the kind enjoyed by newspapers and broadcasters during the latter half of the twentieth century. However, as many observers have noted, contemporary pressures facing legacy news media call for more deliberate and sustained attention to media innovation. Such investments in media innovation need not undermine journalistic professionalism and practice, but rather may be about transforming a firm’s cultural and technological orientation to better serve news consumers in a changing media environment—for example, by switching from a product focus to a service orientation.

Management theory points to the potential efficacy of cross-departmental coordination. In particular, Grant’s (Citation1996) knowledge-based view as a theory of the firm starts from the premise that (1) the primary purpose of an organization is to integrate the specialized knowledge resident in individuals (and in groups and departments), (2) such expertise is the most important resource of the firm, and thus (3) “the primary task of management is establishing the coordination necessary for this knowledge integration” (120). Notably, the theory argues that certain organizational structures, such as the bureaucratic model, can be detrimental to the coordination of complex, heterogeneous knowledge within a firm—thus requiring dedicated and contextually sensitive efforts to coordinating knowledge among different individuals and groups.

Given the challenges facing the news media and their necessity for knowledge-based innovation, we draw on Grant’s (Citation1996) perspective to explore two inter-related elements of innovation: coordination and collaboration. First, we examine how news executives perceive the relative interest in innovation across the editorial, business, and information technology (IT) departments of their organizations. Second, we consider whether newspaper executives perceive that collaboration among such departments has increased over time.

The empirical analysis draws on series of bi-annual cross-sectional survey studies (2011, 2013, 2015, 2017) of Norwegian top-level news executives. Results show that while various explorations of digital media were not perceived as having fostered increased collaboration among the three departments in the first half of the period, there has been a significant increase in perceived collaboration more recently. Multivariate analysis reveals that technologists’ apparent interest in change is a key predictor for perceived change in intra-organizational collaboration. This finding points to the role of the IT department in developing innovation in the production and distribution of news. More broadly, this article examines the innovative potential of greater coordination and collaboration in news media organizations.

The Media Innovation Context: Competition, Change, Coordination and Collaboration

Competition

Fierce competition is disrupting the mediascape for news media organizations, as once-prosperous business models for subsidizing news have been diminished, bit by bit, year by year (see examples and discussion in Nielsen Citation2016; Picard Citation2014). Losses in advertising revenues have been especially painful because of digital intermediaries in general and Google and Facebook in particular (Ohlsson and Facht Citation2017). In short, news publishers have generated much news content appearing on Facebook but have seen limited revenue return to their own business (Myllylahti Citation2018; Citation2020). Indeed, of the many changes introduced in the digital era, few have been so consequential for news media companies as the emergence of globally dominant digital intermediaries. Situated between news producers and news consumers, these platforms shape much of how digital information moves and is monetized. Such intermediaries control the vast majority of digital advertising revenue, thus undercutting news business models, and also control a growing share of user time and attention, thus weakening the reach and impact of news organizations’ sites and apps (Nielsen and Ganter Citation2018; Ohlsson and Facht Citation2017). People may be stumbling upon news more frequently, often through incidental exposure on social media, but the platform providers, rather than news organizations, are the ones that have been reaping most of the rewards of such attention (Newman et al. Citation2017). In extension of this, some publishers are reportedly engaging in “platform-counterbalancing,” in which they try to reduce their dependence on the platform companies (Chua and Westlund Citation2019) rather than continuing to build a presence on platforms non-proprietary to them (Steensen and Westlund Citation2020).

This ongoing shift in news consumption from proprietary to non-proprietary platforms has resulted in a dislocation of news journalism, partly decoupling news items from their original publishers (Ekström and Westlund Citation2019). Scholars have also questioned what influence news media have over gatekeeping, considering that platforms, algorithms, and users have gained enhanced significance (Wallace Citation2018). While digital intermediaries offer their platforms for anyone who want to publish, they also often declare that they are not to be held accountable for the content itself (Gillespie Citation2018), including misinformation and so-called “fake news” (Tandoc, Lim, and Ling Citation2018), junk content fueled by revenues coming from the ad-tech industry, where fake bot traffic plays a significant role (Braun and Eklund Citation2019). And, in addition to dominating the market for digital advertising, platform providers learn far more about news audiences and their interests than news organizations do, leading to asymmetries in audience understanding that limit opportunities to compete. In the view of Axel Springer, the largest digital publisher in Europe, digital intermediaries “have a scale, they have the direct customer relations, they have the data, they have all the insights, and they can connect the dots, and they are doing this a lot better than we will ever be able to … I see a huge, huge, huge threat coming up through Google and Facebook … it’s frightening” (Küng Citation2017, 12).

Change

Amid this loss of control to social media gatekeepers, it’s nevertheless true that many news media firms remain profitable enterprises—and yet, the need for the industry broadly to retool business models, develop new products and services, and otherwise innovate to survive is becoming more pronounced. Pundits, practitioners, and researchers alike have called for news media companies to invest more in research and development and altogether expand their capacity for media innovation (see, e.g., Küng Citation2017; Nel Citation2017; Picard Citation2014; Storsul and Krumsvik Citation2013; Westlund and Lewis Citation2014). Importantly, there is a strong link between media innovation and organizational change. For example, Küng (Citation2017) shows the need for scholars to turn to the dynamics at play inside news organizations. She draws on in-depth interviews with 60 informants at 18 international or national news media companies around the world, and concludes:

Established media run the risk of undermining their content transformation because they are putting too little effort into transforming their organisations. As a result, they are being outperformed by new players, although their content, brands, and commitment to their readers are often far superior. This threatens sustainability and viability—and is unnecessary. They are leaving opportunities for growth and leadership on the table (9).

Media innovation is inexorably linked to societal innovation (Bruns Citation2014), and may include many elements of media change, such as how media firms develop new platforms, reconfigure and develop their business models, to the ways in which they are producing content (Aitamurto and Lewis Citation2013; Storsul and Krumsvik Citation2013). As a concept, media innovation comprises both the innovation of media technology and media work. Such approaches may involve changes in product, process, market position, paradigm, and more specific genre innovations (e.g., Miller Citation2016). Technological developments, institutional factors, and sociocultural conditions are identified as the main drivers of media innovation, and industry norms are one of the key institutional factors that define the scope of such innovation efforts (Krumsvik et al. Citation2019).

For example, the “church and state” separation between marketing and journalism (Coddington Citation2015) has implications for the influence of commercial considerations in the development of new products and services, and thus may define the competences of personnel chosen to develop innovations at the intersection of news and business (Krumsvik et al. Citation2019).

More broadly, change as a concept and point of emphasis should not be taken for granted. The study of change has assumed “almost paradigmatic status” in journalism studies, with researchers so fixated on change that they run the risk of merely chasing the latest technological fads and thereby adopting “the rather predictable form of identifying how X is changing and what this means for journalism” (Peters and Carlson Citation2018, 3). Indeed, as Carlson and Lewis (Citation2018) further argue, scholars studying change should keep in mind the challenging matter of time, adopting a “temporal reflexivity” that leads toward a critical self-reflection about whether the phenomenon being studied “is indeed a break from what came before, a continuation of what has existed, or some middle-ground mutation” (3). In the spirit of that reflexivity, this article tracks change over time, seeking to understand how ideas about change, indeed, have changed from one period to another.

Moreover, let us be clear that while there may be a difference between perceived change (in an epistemological sense) and “actual” change (in an ontological sense), this cannot be determined. The study and analysis of change—or any other reality, for that matter—is an epistemological, knowledge-producing exercise, regardless of the methods used. This is not to say that there is no difference between methods relying on self-reported measures such as interviews and surveys and methods such as ethnography conducted through many observations over weeks or months—rather, it simply is to acknowledge the limitations of any research methods in definitively explaining a given state of affairs because of limits in human perception, awareness, and expression. Nevertheless, insofar as perceptions serve as a reasonable proxy for actual attitudes and actions—as they do in virtually all surveys conducted—then they matter for representing actual change in this study. This is particularly so when those perceptions are gathered from informants who are in a good position to know, as is the case with the newspaper executives studied here.

Coordination and Collaboration

To innovate, a company must use and apply its knowledge in developing something new (or partially new), and put it into use, and both of these aspects of innovation depend on coordination and collaboration occurring among specialists involved. Examples of media innovation in news organizations include the developing and deploying of mobile news applications (Weber and Kosterich Citation2018; Westlund Citation2011) as well as systems for audience metrics, such as those configured in-house or by third-parties and then appropriated and sometimes further developed by journalists (see, e.g., Belair-Gagnon and Holton Citation2018; Carlson Citation2018; Zamith Citation2018).

Media innovation requires different kinds of knowledge. Such heterogeneous expertise resides with individuals and different groups of the media firm (cf. Grant Citation1996; Nielsen Citation2012; Westlund Citation2011). Media innovation in the form of a new mobile news application, for instance, may require a news media organization coordinating knowledge-sharing among its journalists, technologists, and businesspeople (Westlund Citation2011; Citation2012). These groups have different forms of knowledge, and by coordinating them (and possibly facilitating the further step of collaboration) the organization can achieve more than it could by having people and teams working in isolation (cf. Grant Citation1996)—thereby developing and/or sustaining what is famously known as competitive advantage (Porter Citation1979).

Historically, however, many news media firms have deliberately organized in ways that prevent some of their social actors from formally coordinating with each other. There has long been a dividing line—a veritable “wall”—between journalists and businesspeople within news organizations. This functional separation has served the purpose of distinguishing the “words” (the news production process by seemingly independent journalists) from the “money” (the commercial forces such as advertisers and investors, managed by the businesspeople). It has been symbolically erected to ensure the autonomy and professionalism of journalists and has traditionally been seen as essential to maintaining the credibility and legitimacy for independent journalism (Coddington Citation2015; Djerf-Pierre and Weibull Citation2011; Raviola Citation2010). Essentially, this is a form of “duality management” in which an editor takes charge of the journalism and a CEO takes responsibility for the company as a whole—but does not interfere with the news operation (Achtenhagen and Raviola Citation2009).

Such an approach, of one side mostly ignoring the other, may have worked well enough during a period of stability and often oligopolistic control in local markets for legacy news organizations, but it unravels amid the present need for wholesale reconfiguration of media businesses to match the contemporary environment. Of course, simply allowing business types to “rule the newsroom” has long been acknowledged as a failing strategy. A more strategic and less unidimensional strategy is one that better recognizes the diverse sets of expertise represented by a variety of people in the organization—including, beyond the newsroom, businesspeople and technologists (Lewis and Westlund Citation2015), which constitute three key groupings.Footnote1 The former includes marketers, managers, and other revenue-minded specialists, while the latter includes a growing array of technologically oriented workers who bring specialties in data, design, and programming and otherwise help to build and maintain the software architecture for news applications and publishing. Technologists, in particular, have assumed a growing role in news organizations and, correspondingly, have become a focus in journalism studies (Lewis and Usher Citation2013; Usher Citation2016; Weber and Kosterich Citation2018). Some technologists have backgrounds in news and may work on news-facing products (see examples in Usher Citation2016), but technologists as a category also (and perhaps especially) includes Information Technology (IT) specialists who manage information systems for the media organization as a whole. As a result, both businesspeople and technologists may function as “intralopers” (Holton and Belair-Gagnon Citation2018), or interstitial actors who may possess non-traditional approaches to journalism but yet may contribute to disrupting or reshaping what counts as news and how it is produced.

Several studies throughout the 2010s have used qualitative methods to examine intra-organizational coordination among journalists, businesspeople, and technologists (Baack Citation2018; Nielsen Citation2012; Westlund Citation2011). One U.S.-based study indicates that former walls are gradually becoming reconfigured, with movements toward more collaboration between businesspeople and journalists (Drew and Thomas Citation2018). At present, there are few quantitative studies of these points of coordination and collaboration, as cross-national surveys such as the Worlds of Journalism project focus almost exclusively on journalists alone. The few exceptions in the research literature, however, do suggest that intra-organizational collaboration may be developing in news media companies (see, e.g., Westlund and Krumsvik Citation2014).

Knowledge-based View: Social Actors Coordinating Toward Shared Organizational Goals

This article integrates a social emphasis on distinct actors in news media organizations with Grant’s (Citation1996) knowledge-based view from management studies. His approach suggests that firms develop strategies in correspondence with their organizational capabilities, which are closely linked to knowledge. An organization can be seen as both an engine and repository of knowledge, producing, storing, and implementing knowledge. For example, various forms of organizational learning—most notably experiential learning (i.e., learning from positive and/or negative experiences) and vicarious learning (i.e., observing other organizations/industries)—may combine to form an overall body of organizational knowledge (March Citation1991). Such knowledge acquisition and application, however, depends on social actors communicating and coordinating their work and experiences with each other. The knowledge-based view works under the assumption that knowledge, and in particular the coordination of knowledge within an organization, is crucial to a firm’s performance.

There is much debate about what constitutes knowledge. Like Grant and other management scholars, we find that it suffices to say that there is an important epistemological distinction between people’s explicit knowledge and their tacit knowledge. Explicit knowledge refers to “objective” and declarative knowledge in the form of knowing about. By contrast, tacit knowledge encompasses implicit, personal, and procedural knowledge in the form of knowing how. To make the best of both types of knowledge, organizations need to develop and implement shared goals and ensure that employees coordinate their work with each other (Grant Citation1996). Few individuals possess the expertise and time necessary to accomplish everything in a company. The larger the company becomes, the more important it is to delegate responsibilities to different staff members, thus requiring more and more people with varied forms of expertise. Drawing on extant literature, Lewis and Westlund (Citation2015) have made the case that journalists, businesspeople, and technologists are currently the three most important actors inside news media organizations, each representing three key domains of expertise that are particularly necessary for the functioning of the organization.

According to the knowledge-based view, an organization’s overall capability, and therefore competitive advantage in the market, is the outcome of how knowledge is being used and integrated by its diverse sets of individual specialists (Grant Citation1996). Organizational coordination of individual specialists and what they know is presumed to be the engine that drives the creation and application of organizational knowledge. The knowledge-based view thus suggests that the organization is an institution working toward integrating knowledge. Limitations apply to the capacity of individual humans, yet knowledge is a prerequisite for human productivity. People develop their individual sets of expertise through education, training, experiences, and so forth. Organizations need different kinds of expertise and thus employ different professionals to perform distinct tasks, by themselves or in collaboration with others. As Cestino and Matthews (Citation2016, 26) write, “As a result of the efficiency gains of specialization, the central exercise of organizations is to coordinate the work of different specialists.” In principle, all theories of the firm suggest specialized knowledge is a fundamental premise to organizations and their production activities. If there were no gains and advantages connected to specialization, there would be no need for organizations in hiring multiple individuals. What matters, in this case, is to understand the relative value of such coordination of knowledge across departments and within organizations.

Toward a Synthesis: Knowledge Coordination and Intra-organizational Collaboration

The knowledge-based view highlights the importance of knowledge coordination, which is a concept interrelated with collaboration. At first glance, these concepts seem synonymous, but they carry different meanings. Knowledge is the key concept in this context, and concepts such “diffusion,” “transfer” or “dissemination” of knowledge imply that knowledge is something which can be communicated from Person A to Person B (or from one group of employees to another). This may work relatively easily with forms of explicit knowledge, which are tangible and can be expressed in words or numbers. But the transfer of tacit knowledge is more complicated, as it may require people to work with each other, closely observing how things are done (Grant Citation1996).

Grant (Citation1996) finds that many organizational scholars focus on problems relating to collaboration. This includes but is not limited to problems surfacing as different social actors seek to reconcile their different professional goals. The aforementioned literature in journalism studies and media management has provided many examples of ongoing tensions among different professionals in news media organizations (cf. Achtenhagen and Raviola Citation2009; Drew and Thomas Citation2018). Knowledge coordination involves interacting with each other in working toward shared organizational goals. Coordination may facilitate collaboration, but it is also possible that people in organizations coordinate with one another but nevertheless experience tensions that lead them to resist collaboration. In this sense, collaboration speaks to an individual’s or group’s willingness to work with cross-department colleagues around a shared objective. If collaboration is impeded—whether by choice, by organizational structure, or by management directive—then even the mere act of knowledge coordination will be difficult.

Research Questions and Methods

Conceptually, media innovation encompasses both the invention and implementation of something new, whether products, services or processes (e.g., Storsul and Krumsvik Citation2013). Turning to the news industry, and more specifically the Scandinavian news industry, media innovation is described as including “digital developments” and the advancements and implementations of “new media” in a somewhat generic sense (c.f. Westlund Citation2011; Citation2012). Indeed, the news industry more generally is known for its pursuit to appropriate digital technology, although not necessarily with well-informed strategies, as firms too often chase the latest technology fads without a coherent framework (Posetti Citation2018). Overall, there is a pro-innovation bias in the journalism sector, and, as such, this has also led to a substantial body of research on journalism and media innovation (Steensen and Westlund Citation2020).

This article focuses on newspaper executives’ perceptions regarding intra-organizational dynamics relating to what scholars refer to as media innovation, or what executives and other practitioners sometimes generically refer to as digital developments. The article draws upon the knowledge-based view and its emphasis on knowledge coordination, in combination with research on collaboration among social actors in news media organizations.

This study is concerned with two primary research questions. The first seeks to investigate the perceived interest in cross-departmental coordination among diverse social actors. The second focuses on whether their digital media innovation work (and the coordination it involved) has resulted in more intra-organizational collaboration. Ultimately, the two research questions attempt to study perceptions about the inter-relationship of coordination and collaboration in intra-organizational dynamics over time.

RQ1: Over time, do newspaper executives perceive that there is comparatively more or less interest in participating in the coordination of change activities across the editorial, business, and information technology departments of their organization?

RQ2: Amid ongoing change and interest in participating in change, do newspaper executives perceive that collaboration among members of their editorial, business and information technology departments has changed over time?

These questions were explored by analyzing data from Norway, a democratic-corporatist media system where newspapers and digital media occupy strong positions in terms of reach and usage (Hallin and Mancini Citation2004). Like their counterparts in most countries, Norwegian newspapers have had a tradition of separating editorial and marketing/business departments. The overall reach of the press has historically been stronger in Scandinavia compared to the United States and elsewhere in the developed world (except for Japan and Switzerland). Nonetheless, newspapers in all of these countries have faced relatively similar challenges to their conditions for running a journalism business. Norwegian news publishers, like publishers around the world, have continuously engaged in different types of innovations. For example, this includes developing mobile news and applications for smartphones and tablets (Duffy et al. Citation2020; Weber and Kosterich Citation2018) as well as infrastructures for analytics and metrics for editorial processes through involvement of external parties (Belair-Gagnon and Holton Citation2018). While the focus here is on the perceptions of Norwegian top executives regarding journalists, businesspeople, and technologists, the results nonetheless hold wider significance for understanding digital media innovation in newspaper organizations and in news media more broadly, particularly in mature media markets where print is in decline and digital is on the rise.

The empirical analysis draws upon four surveys of Norwegian newspaper executives, conducted in 2011, 2013, 2015, and 2017. Chief executives (Editor-in-Chief, Managing Director, and Publisher) representing print newspapers responded to survey questions. Invitations were sent by e-mail to addresses provided by the Norwegian Media Businesses’ Association (MBL) and the National Association of Local Newspapers (LLA). The surveys were conducted through the web-based research service QuestBack. Respondents were not sampled, as all member newspapers of these two associations were included, and non-response was interpreted as negative self-selection. The response rate was between 46 and 60 percent () after three rounds of email reminders. An advantage of surveying executives in this way has to with developing knowledge about overall patterns across many publishers in the country, and over time. Disadvantages in the research design includes issues of whether executives are sufficiently informed to express perceptions about the collaboration among their media workers, and also that what counts as “new media” changes over time. Ultimately, to date there is limited research available across publishers and over time, and thus this is a unique study in that regard.

Table 1. Respondents and response rates.

There is a general tendency in these surveys of a lower response rate among Managing Directors. In the 2011 survey, 107 (47%) respondents were Editors-in-Chief, 68 (30%) Managing Directors, and 30 (13%) Publishers, while 24 (10%) had other positions or chose not to answer this question (these have been excluded from the analyses). Organizations do not have a register of management models in member newspapers; however, the dual management model of an Editor-in-Chief (EiC) and a Managing Director (MD) is the standard model in Norway. The EiC is then responsible for the editorial department and the MD for sales and marketing, with both reporting to the board of directors as joint chief executives. At some newspapers, the same person fills both roles, functioning as Publisher, according to this media system.

The surveys focused on the perceptions of executives, the people responsible for developing strategy for their respective newspapers. The research questions were operationalized into single-item survey measures of how they assess the role of key actors in their organization—namely, the different departments involved in digital media innovation. To assess the first research question, regarding perceptions of departmental interest in participating in the coordination of digital media innovation, survey respondents were asked, “How would you assess the general interest/willingness to participate in the development of new media in these groups?” For the second research question, regarding perceptions about whether intra-organizational collaboration has increased because of digital media innovation work, respondents were asked, “To what extent has the collaboration between the following groups increased as a result of working with new media?” Statistical tests (T-tests and linear regression) were used to assess the results, with an alpha level of 0.05 applied.

By using these methods, we obtained reliable and valid data. The study should generate theoretically generalizable insights, both in the Norwegian newspaper setting and for other traditional news media in countries with similar media ecologies.

Results

This section presents findings of the newspaper executives’ perceptions of the interest that media workers in the editorial, business, and IT departments have in participating in the coordination of digital media innovation (RQ1). It also analyzes whether newspaper executives perceive that specific forms of intra-organizational collaboration have increased, in light of coordinating their digital media innovation work and also the perceived interest in such activities among departments (RQ2).

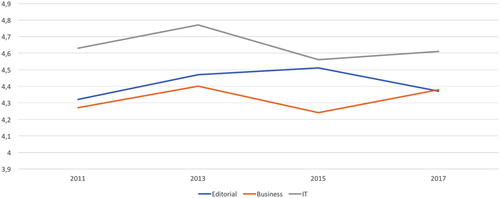

Perceptions about the Interest in Participating in the Coordination of Digital Media Innovation (RQ1)

There is a parallel development and a consistent significant difference in the perceived interest in digital media innovation, when comparing the IT department and the business department, with the mean difference varying from 0.37 in 2013–0.23 in 2017 (see ). In the latter year, the perceived interest of the IT department (m=4.66, s=1.12) was also significantly higher than that of the editorial department (m=4.38 s=1.08), t(142) = 3.328, p=.001.

Figure 1. Relative interest by department in participating in media innovation, 2011–2017 (as perceived by newspaper executives).

Note: Question in survey: How would you assess the general interest/willingness to participate in the development of new media in these groups? 1 = low degree 6 = high degree.

Taking a closer look at the two main groups of executives, we find that managers perceived the IT department’s interest higher than the editors. The mean difference was statistically significant in both 2011 and 2015 (see ).

Table 2. Perceptions of departmental interest (for IT and business departments) in participating in coordinating media innovation, 2011–2017 (Mean).

The managers also had a tendency to score the business department to be significantly more interested than the editors did, from 2011 to 2015. In 2017, the mean difference was not statistically significant (see ). There was no statistically significant mean difference between editors and managers in the perception about interest in participating in their coordination of digital media innovation in the editorial department.

Perceptions of Organizational Collaboration (RQ2)

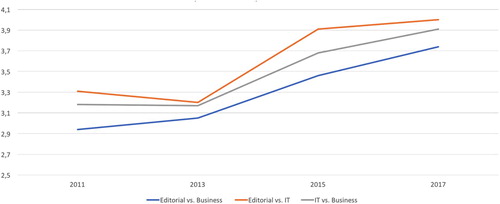

The results reveal a positive trend in the perceptions of increased intra-organizational collaboration as a result of working with new media, representing different forms of digital media innovation (). Importantly, the general interest and willingness to participate in the coordination and development of new media at the IT departments are the strongest predictors for how executives perceive the level of collaboration. Hence, in the relationship with other departments, the interest in new media development at the IT department is always the strongest predictor. On the other side, the willingness to develop new media in the editorial department is not the strongest predictor for increased collaboration in any of the relationships (see ).

Figure 2. Perceptions about whether intra-organizational collaboration has increased because of media innovation work (2011–2017).

Note: Question in survey: To what extent has the collaboration between the following groups increased as a result of working with new media? 1 = to a small extent 6 = to a large extent.

Table 3. Perceptions about departmental interest in participating in media innovation, as predictors for perceptions of intra-organizational collaboration (2011–2017).

Discussion and conclusion

Embedded in a context of increasing Competition (A) and Change (B) in the digital media environment, this article has analyzed intra-organizational dynamics in the news media industry, with specific emphasis on Coordination and Collaboration (C). Building on Grant’s (Citation1996) knowledge-based view of the firm, and drawing on a series of cross-sectional surveys with Norwegian newspaper executives, this study advances our understanding of how diverse social actors in news organizations are perceived to be working with each other and to what effect for media innovation.

The first research question sought to explore how various workers are perceived to engage in cross-departmental coordination of digital media innovation. Overall, the findings show that the IT department representatives were perceived to be significantly more interested than the business department in media innovation. On the one hand, the news media would benefit from having their entire workforce interested in developing and making best use of digital media innovations. On the other hand, one should avoid assuming a non-reflexive, pro-innovation stance, as practitioners, think tanks, foundations, and even researchers tend to do. “Often,” Creech and Nadler (Citation2018) remind us, “ahistorically and uncritically deployed notions of innovation elide questions of digital journalism’s democratic aspirations in favor of market-oriented solutions” (182). Moreover, media companies should avoid equating innovation with the latest technological fad—otherwise known as “Shiny Things Syndrome,” or “the obsessive pursuit of technology in the absence of clear and research-informed strategies” (Posetti, Citation2018, p. 7). Indeed, in her cross-national study of news innovation, Posetti (Citation2018) found that the “relentless, high-speed pursuit of technology-driven innovation could be almost as dangerous as stagnation” because it led to “innovation fatigue” in an era of continuous change (7). Innovation, therefore, must be critically situated in a broader context.

Because technologists at the IT department are employed to develop and maintain technological tools and systems, being interested in media innovation may feel like an extension of their job description, particularly at a time when, as Posetti (Citation2018) shows, so much of what passes as news innovation is situated as inherently technological. Journalists and businesspeople, on the other hand, may well spend most of their time at work producing and publishing a daily news product, on the one hand, or managing advertising, reader revenue, and subscriber churn, on the other.

While perhaps to be expected in the context of what they do, the perceived differences between these groups in their interest in media innovation nevertheless presents a longer-run problem for media organizations. This is particularly so because innovation—when developed carefully and deployed strategically, in a sustainable rather than chaotic way (Posetti Citation2018)—is a crucial bridge to the digital future for legacy news media. As featured in a 2017 WAN-IFRA World News Publishers Outlook, “when asked, ‘What is the single most important risk to your news organization’s future success?’, the largest number of executives in our study (26 percent) answered: their organizations’ reluctance to innovate” (Nel Citation2017, 5).

This brings us to the second research question, regarding the perceived increase in intra-organizational collaboration. This goes in harmony with other studies concluding that there are important cultural shifts taking place inside news organizations, in other parts of Scandinavia (Westlund Citation2011), in the U.S. (Drew and Thomas Citation2018), and beyond (Cornia, Sehl, and Nielsen Citation2018). The results reveal a positive trend in the perceptions of increased intra-organizational collaboration (see ). A key finding is the interest and willingness to participate in the coordination and development of new media at the IT departments as the strongest predictors for how executives perceive the level of collaboration.

Ultimately, the two research questions attempt to study perceptions about the interrelationship of coordination and collaboration in intra-organizational dynamics over time. Results show that while the various explorations of digital media were not perceived to have fostered increased collaboration among people in the three departments in the first half of the period (2011 and 2013), there has been a significant increase in perceived collaboration more recently. Multivariate analysis reveals that technologists’ apparent interest in change is a key predictor for perceived change in intra-organizational collaboration. This finding points to the important role of the IT department for developing innovation in the production and distribution of news. Importantly, this means that innovation seems to be driven from a support function (i.e., the IT department) rather than by the core operational functions of the business (i.e., business and/or editorial). The editorial representatives are perceived to play a less-pronounced role, which may result in their tacit and explicit knowledge not being used as much in internal processes of innovation. Over the course of 2011–2017, the news media industries have, of course, carried out substantial digital developments and established a variety of digital partnerships. The news industry as a whole, and particularly so in Norway, has seen more sophisticated audience analytics and metrics, improved editorial content management systems and automated forms of news publishing, among other things. However, the moving target of innovation, particularly in a mad scramble for solutions to crises in journalism perhaps has led news executives to note only moderate levels of interest in media innovation among their subordinates. And yet, the coordination of digital media innovation seems to have brought journalists, technologists, and businesspeople more closely together, with significant increases in perceived levels of collaboration. This study reinforces how actors outside of the newsroom are seen as driving media innovation, and thus supports calls for incorporating other social actors into the study of journalistic work (Lewis and Westlund Citation2015) and innovation (Westlund and Lewis Citation2014)—and the field of journalism studies more broadly. It is essential for journalism studies scholars to more systematically study social actors beyond the newsroom, and to evaluate the interactions that occur among them, to better understand the true breadth of media work and the changing conditions for journalism. (This is true even as the fallout of the Covid-19 global pandemic hastens the move toward increasingly virtual, networked forms of interaction that may complicate traditional forms of news ethnography.)

Furthermore, scholars should pay more attention to how journalists coordinate their expertise with each other, and with other social actors, in both journalistic work and media innovation. Chua and Duffy (Citation2019) say that four forms of proximity—physical, temporal, professional, and control—are important for understanding how different people may influence forms of news work and media innovation broadly. They identify the emergence of hybrid roles, as peripheral actors gradually become recognized for their contributions to journalistic work (Chua and Duffy Citation2019).

Ultimately, future research should look more specifically into how these individuals and departments coordinate their diverse sets of explicit and tacit knowledge. This applies to specific kinds of media innovation processes as well as journalistic work routines demanding coordination among a diverse set of journalists and technologists to accomplish organizational goals (Westlund and Lewis Citation2014). It is also important to study if and how they collaborate more closely on some media innovation projects compared to others. Additionally, researchers could study which social actors in news organizations take part in eventual activities geared toward coordinating and collaborating with external partners—from other media firms to digital intermediaries such as Facebook and Google, such as around questions of audience metrics, fact-checking, and misinformation. Finally, it matters to consider how innovation is socially constructed and materially enacted at multiple levels within media organizations, and how coordination and collaboration are together associated with such definitions and developments.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Most social actors working within news organizations can be classified into one of these three primary groups—journalists, businesspeople, and technologists—though inevitably there will be some exceptions, such as employees operating printing presses. Nevertheless, even where departments such as Circulation have been rebranded as “Audience Development,” the people in such groups have a business imperative that positions them within the businesspeople category.

References

- Achtenhagen, L., and E. Raviola. 2009. “Balancing Tensions During Convergence: Duality Management in a Newspaper Company.” JMM International Journal on Media Management 11 (1): 32–41.

- Aitamurto, T., and S. C. Lewis. 2013. “Open Innovation in Digital Journalism: Examining the Impact of Open APIs at Four News Organizations.” New Media & Society 15 (2): 314–331.

- Andersson, U., and J. Wiik. 2013. “Journalism Meets Management.” Journalism Practice 7 (6): 705–719. doi:10.1080/17512786.2013.790612.

- Appelgren, E., and G. Nygren. 2019. “HiPPOs (Highest Paid Person’s Opinion) in the Swedish Media Industry on Innovation: A Study of News Media Leaders’ Attitudes towards Innovation.” The Journal of Media Innovations 5 (1): 45–60. doi:10.5617/jomi.6503.

- Baack, S. 2018. “Practically Engaged.” Digital Journalism 6 (6): 673–692.

- Belair-Gagnon, V., and A. E. Holton. 2018. “Boundary Work, Interloper Media, And Analytics In Newsrooms.” Digital Journalism 6 (4): 492–508.

- Belair-Gagnon, V., A. Holton, and O. Westlund. 2019. “Space for the liminal.” Media and Communication 7 (4): 1–4.

- Braun, J., and J. L. Eklund. 2019. “Fake News, Real Money: Ad Tech Platforms, Profit-Driven Hoaxes, and the Business of Journalism.” Digital Journalism 7 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1080/21670811.2018.1556314.

- Bruns, A. 2014. “Media Innovations, User Innovations, Societal Innovations.” The Journal of Media Innovations 1 (1): 13–27.

- Carlson, M. 2018. “Confronting Measurable Journalism.” Digital Journalism 6 (4): 406–417.

- Carlson, M., and S. C. Lewis. 2018. “Temporal Reflexivity in Journalism Studies: Making Sense of Change in a More Timely Fashion.” Journalism 642–650. doi:10.1177/1464884918760675.

- Cestino, J., and R. Matthews. 2016. “A Perspective on Path Dependence Processes: The Role of Knowledge Integration in Business Model Persistence Dynamics in the Provincial Press in England.” Journal of Media Business Studies 13 (1): 22–44.

- Cheruiyot, D., and R. Ferrer-Conill. 2018. “Fact-Checking Africa.” Digital Journalism 6 (8): 964–975. doi:10.1080/21670811.2018.1493940.

- Chua, S., and A. Duffy. 2019. “Friend, foe or Frenemy? Traditional Journalism Actors’ Changing Attitudes Towards Peripheral Players and Their Innovations.” Media and Communication 7 (4): 112–122. doi:10.17645/mac.v7i4.2275.

- Chua, S., and O. Westlund. 2019. “Audience-centric Engagement, Collaboration Culture and Platform Counterbalancing: A Longitudinal Study of Ongoing Sensemaking of Emerging Technologies.” Media and Communication 7 (1): 153–165.

- Coddington, M. 2015. “The Wall Becomes a Curtain: Revisiting Journalism’s News–Business Boundary.” In Boundaries of Journalism: Professionalism, Practices and Participation, edited by M. Carlson and S. C. Lewis, 67–82. London: Routledge.

- Cornia, A., A. Sehl, and R. K. Nielsen. 2018. “‘We no Longer Live in a Time of Separation’: A Comparative Analysis of how Editorial and Commercial Integration Became a Norm.” Journalism 146488491877991: 172–190.

- Creech, B., and A. M. Nadler. 2018. “Post-industrial fog: Reconsidering Innovation in Visions of Journalism’s Future.” Journalism 19 (2): 182–199.

- Cueva Chacón, L., and M. Saldaña. 2020. “Stronger and Safer Together: Motivations for and Challenges of (Trans)National Collaboration in Investigative Reporting in Latin America.” Digital Journalism, doi:10.1080/21670811.2020.1775103.

- Deuze, M. 2007. Media work. Cambridge: Polity.

- Djerf-Pierre, M., and L. Weibull. 2011. “From Idealist-Entreprenur to Corporate Executive.” Journalism Studies 12 (3): 294–310.

- Drew, K. K., and R. J. Thomas. 2018. “From Separation to Collaboration.” Digital Journalism 6 (2): 196–215. doi:10.1080/21670811.2017.1317217.

- Duffy, A., R. Ling, N. Kim, E. Tandoc Jr., and O. Westlund. 2020. “News: Mobiles, Mobilities and Their Meeting Points.” Digital Journalism 8 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1080/21670811.2020.1712220.

- Ekström, M., A. Ramsälv, and O. Westlund. 2020 – in press. “The Epistemologies of Breaking News.” Journalism Studies.

- Ekström, M., and O. Westlund. 2019. “The Dislocation of News Journalism: A Conceptual Framework for the Study of Epistemologies of Digital Journalism.” Media and Communication 7 (1): 259–270.

- Eldridge, S. A. 2017. “Hero or Anti-Hero?” Digital Journalism 5 (2): 141–158.

- Eldridge, S. A. 2018. Online Journalism From the Periphery : Interloper Media and the Journalistic Field. London: Routledge.

- García-Avilés, J. A., M. Carvajal-Prieto, F. Arias, and A. De Lara-González. 2018. “How Journalists Innovate in the Newsroom. Proposing a Model of the Diffusion of Innovations in Media Outlets.” Journal of Media Innovations 5 (1). doi:10.5617/jomi.v5i1.3968.

- Gillespie, T. 2018. Custodians of the Internet: Platforms, Content Moderation, and the Hidden Decisions 611 That Shape Social Media. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Grant, R. M. 1996. “Toward a Knowledge-Based Theory of the Firm.” Strategic Management Journal 17 (S2): 109–122.

- Hallin, D. C., and P. Mancini. 2004. Comparing Media Systems : Three Models of Media and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Holton, A. E., and V. Belair-Gagnon. 2018. “Strangers to the Game? Interlopers, Intralopers, and Shifting News Production.” Media and Communication 6 (4): 70–78.

- Koivula, M., M. Villi, and A. Sivunen. 2020. “Creativity and Innovation in Technology-Mediated Journalistic Work: Mapping out Enablers and Constraints.” Digital Journalism, doi:10.1080/21670811.2020.1788962.

- Konieczna, M. 2020. “The Collaboration Stepladder: How One Organization Built a Solid Foundation for a Community-Focused Cross-newsroom Collaboration.” Journalism Studies 21 (6): 802–819. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2020.1724182.

- Krumsvik, A. H., K. Kvale, and P. E. Pedersen. 2017. “Market Structure and Innovation Policies in Norway.” In Innovation Policies in the European News Media Industry: A Comparative Study, edited by H. Van Kranenburg, 149–160. Geneva: Springer.

- Krumsvik, A. H., S. Milan, N. Ni Bhroin, and T. Storsul. 2019. “Making (Sense of) Media Innovations.” In Making Media: Production, Practices, and Professions, edited by M. Deuze, and M. Prenger, 193–205. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Küng, L. 2017. Going Digital - A Roadmap for Organisational Transformation. Oxford: RISJ, Oxford University.

- Lewis, S. C. 2012. “From Journalism to Information: The Transformation of the Knight Foundation and News Innovation.” Mass Communication and Society 15 (3): 309–334. doi:10.1080/15205436.2011.611607.

- Lewis, S. C., and N. Usher. 2013. “Open Source and Journalism: Toward new Frameworks for Imagining News Innovation.” Media Culture & Society 35 (5): 602–619.

- Lewis, S. C., and N. Usher. 2016. “Trading Zones, Boundary Objects, and the Pursuit of News Innovation: A Case Study of Journalists and Programmers.” Convergence 22 (5): 543–560.

- Lewis, S. C., and O. Westlund. 2015. “Actors, Actants, Audiences, and Activities in Cross-Media News Work: A Matrix and a Research Agenda.” Digital Journalism 3 (1): 19–37.

- Lewis, S. C., and R. Zamith. 2017. “On the Worlds of Journalism.” In Remaking the News: Essays on the Future of Journalism Scholarship in the Digital Age, edited by P. J. Boczkowski, and C. W. Anderson, 111–128. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Lowrey, W., L. Sherrill, and R. Broussard. 2019. “Field and Ecology Approaches to Journalism Innovation: The Role of Ancillary Organizations.” Journalism Studies, doi:10.1080/1461670X.2019.1568904.

- March, J. G. 1991. “Exploration and Exploitation in Organizational Learning.” Organization Science 2 (1): 71–87. doi:10.1287/orsc.2.1.71.

- Miller, C. R. 2016. “Genre Innovation: Evolution, Emergence or Something Else?” Journal of Media Innovations 3 (2): 4–19.

- Myllylahti, M. 2018. “An Attention Economy Trap? An Empirical Investigation Into Four News Companies’ Facebook Traffic and Social Media Revenue.” Journal of Media Business Studies 15 (4): 237–253.

- Myllylahti, M. 2020. “Paying Attention to Attention: A Conceptual Framework for Studying News Reader Revenue Models Related to Platforms.” Digital Journalism 8 (5): 567–575.

- Nel, F. 2017. World News Publishers Outlook 2017 - The Annual Perspective on the News Media Industry. Paris: WAN-IFRA.

- Newman, N., R. Fletcher, Antonis Kalogeropoulos, D. A. L. Levy, and R. Nielsen. 2017. The Reuters Institute’s Digital News Report 2017. RISJ - The Reuters Institute’s Digital News Report 2017. Oxford.

- Nielsen, R. K. 2012. “How Newspapers Began to Blog: Recognizing the Role of Technologists in old Media Organizations’ Development of new Media Technologies.” Information, Communication & Society 15 (6): 959–978.

- Nielsen, R. K. 2016. “The Business of News.” In The SAGE Handbook of Digital Journalism, edited by T. Witschge, C. W. Anderson, D. Domingo, and A. Hermida, 128–143. London, England: Sage UK.

- Nielsen, R. K., and S. A. Ganter. 2018. “Dealing with Digital Intermediaries: A Case Study of the Relations Between Publishers and Platforms.” New Media & Society 20 (4): 1600–1617.

- Ohlsson, J., and U. Facht. 2017. Ad Wars. Gothenburg: Nordicom.

- Ostertag, S., and G. Tuchman. 2012. “When Innovation Meets Legacy.” Information, Communication & Society 15 (6): 909–931. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2012.676057.

- Peters, C., and M. Carlson. 2018. “Conceptualizing Change in Journalism Studies: Why Change at all?” Journalism 146488491876067, doi:10.1177/1464884918760674.

- Picard, R. G. 2014. “Twilight or New Dawn of Journalism?” Digital Journalism 2 (3): 273–283. doi:10.1080/21670811.2014.895531.

- Porcu, O., L. Hermans, and M. Broersma. 2020. “Unlocking the Newsroom: Measuring Journalists’ Perceptions of Innovative Learning Culture.” Journalism Studies 21 (10): 1420–1438. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2020.1758956

- Posetti, J. 2018. Time to Step Away from the ‘Bright, Shiny Things’? Towards a Sustainable Model of Journalism Innovation in an Era of Perpetual Change. RISJ Research Report. Oxford: University of Oxford.

- Porter, M. 1979. “How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy.” Harvard Business Review 57 (2): 137–145. doi:10.1097/00006534-199804050-00042.

- Raviola, E. 2010. Paper Meets Web. Jönköping: Jönköping University Press.

- Schapals, A., P. Maares, and F. Hanusch. 2019. “Working on the Margins: Comparative Perspectives on the Roles and Motivations of Peripheral Actors in Journalism.” Media and Communication 7 (4): 19–30.

- Scott, M., M. Bunce, and K. Wright. 2019. “Foundation Funding and the Boundaries of Journalism.” Journalism Studies, doi:10.1080/1461670X.2018.1556321.

- Sehl, A., A. Cornia, L. Graves, and R. K. Nielsen. 2018. “Newsroom Integration As An Organizational Challenge.” Journalism Studies, doi:10.1080/1461670X.2018.1507684.

- Steensen, S., and O. Westlund. 2020. What is Digital Journalism Studies. London: Routledge.

- Storsul, T., and A. H. Krumsvik. 2013. “What is Media Innovation?” In Media Innovations. A Multidisciplinary Study of Change, edited by T. Storsul, and A. H. Krumsvik, 13–26. Oslo: Nordicom.

- Tandoc, E. C., Z. W. Lim, and R. Ling. 2018. “Defining “Fake News.”.” Digital Journalism 6 (2): 137–153.

- Usher, N. 2016. Interactive Journalism: Hackers, Data, and Code. Urbana-Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Usher, N. 2017. “Venture-backed News Startups and the Field of Journalism.” Digital Journalism 5 (9): 1116–1133. doi:10.1080/21670811.2016.1272064.

- Waldenström, A., J. Wiik, and U. Andersson. 2018. “Conditional Autonomy.” Journalism Practice, 1–16. doi:10.1080/17512786.2018.1485510.

- Wallace, J. 2018. “Modelling Contemporary Gatekeeping.” Digital Journalism 6 (3): 274–293.

- Weber, M. S., and A. Kosterich. 2018. “Coding the News: The Role of Computer Code in Filtering and Distributing News.” Digital Journalism 6 (3): 310–329.

- Westlund, O. 2011. Cross-Media News Work Sensemaking of the Mobile Media (R)Evolution. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg, 1–367.

- Westlund, O. 2012. “Producer-centric Versus Participation-Centric: On the Shaping of Mobile Media.” Northern Lights 10 (1). doi:10.1386/nl.10.107-1.

- Westlund, O., and A. H. Krumsvik. 2014. “Perceptions of Intra-Organizational Collaboration and Media Workers’ Interests in Media Innovations.” The Journal of Media Innovations 1 (2): 52–74.

- Westlund, O., and S. C. Lewis. 2014. “Agents of Media Innovations: Actors, Actants, and Audiences.” The Journal of Media Innovations 1 (2): 10–35.

- Zamith, R. 2018. “Quantified Audiences in News Production: A Synthesis and Research Agenda.” Digital Journalism 6 (4): 418–435.