ABSTRACT

This article analyses two digital-native news organisations, BuzzFeed News UK and Vice News (UK), and explores how they use emotional forms of storytelling in their election reporting. Drawing on a qualitative textual analysis of 280 news articles published during the 2017 UK general election, we scrutinise the textual and visual elements of emotional storytelling across three distinct groupings: (1) language and tone; (2) visual, formatting, and interaction, and (3) production and editorial choices. We argue that BuzzFeed and Vice draw on an emotional vernacular to engage with and relate to their young audience, while simultaneously providing a gateway to convey sophisticated political content. Both organisations embrace internet culture in their reporting, drawing on subjective, confessional, and personalised forms of expression that characterise communication on social media. The journalistic work required to wrap long-form, analytical election reporting in an emotive narrative provides evidence of innovative audience-orientated practice. In doing so, BuzzFeed and Vice offer election coverage that is uniquely tailored to a younger audience.

On 13 May Citation2020, BuzzFeed's news editor Alan White posted a thread on Twitter:

Unlike newspapers at the time we generally treated things happening on social media with the seriousness they deserved—we understood things that happened online weren't just an “internet story,” they had to be treated with the rigour we’d report anything else. (…) We realised there was a lot of weird pageantry around how news is presented. Tell the story as you’d tell it to your friends in a pub; the internet's a social place.

In 2017, then Prime Minister Theresa May unexpectedly announced a snap election, in an attempt to consolidate her majority in advance of the Brexit negotiation process. The result, however, backlashed against the Conservatives and, despite having won, May lost her majority in Parliament and, unexpectedly, the Labour Party led by Jeremy Corbyn gained seats. This was a historical election equally because of another unforeseen outcome: a growth in youth turnout that some called a “youthquake” in British politics (Sloam and Henn Citation2018). This highlights the pressing need to explore news sources that directly target younger voters, particularly online news media.

This article analyses how emotional storytelling devices are used in election reporting by digital-native news organisations BuzzFeed News UK and Vice News (UK). Drawing on a qualitative textual analysis of 280 news articles published during the 2017 UK general election, we scrutinise the textual and visual elements of emotional storytelling across three distinct groupings: (1) language and tone; (2) visual, formatting, and interactive opportunities, and (3) production and editorial choices. We see the election coverage in BuzzFeed and Vice as part of a broader informalisation of the management of public emotions (Wouters Citation2007), and subsequent informalisation of politics (Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2020) and journalism. The central argument defended in this paper is that, instead of dismissing these digital natives as infotainment, we consider the informalisation of news as a gateway to serious political coverage, that readjusts long-established paradigms of political journalism. Their unique work, we argue, is carefully and emotionally crafted envisioning an experience of involvement (Peters Citation2011), and designed for a particular audience. This includes drawing on subjective, confessional, and personalised forms of expression that characterise communication on social platforms. In this sense, journalists at BuzzFeed and Vice draw on an emotional vernacular strategically (Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2019, Citation2020) and with the functionality (Pantti Citation2010) of engaging with their audience. In the aftermath of the closure of BuzzFeed News UK and the downsizing of Vice News (UK), we present evidence of this innovative audience-orientated practice, reflect on its significance for young audiences, and consider its future.

To understand the use of emotional storytelling in election reporting at BuzzFeed and Vice, the following sections consider their approach to journalism and explore the idea of a distinctive emotional vernacular. We identify the production and consumption norms of both organisations and illustrate how emotional discourse is central to their editorial voice. This is contrasted to existing research that shows similarities between legacy news media and digital-native news organisations in the way elections are reported.

News Production and Consumption at BuzzFeed and Vice

To understand the role of emotion in election reporting at BuzzFeed and Vice, it is necessary to consider their unique approach to journalism. Founded in 2006 by current CEO and Huffington Post alumni, Jonah Peretti, BuzzFeed was designed to track and share viral content. It has since become renowned for its listicles, memes, and obsession with cats, with 22,500 articles about or including cats between 2006 and 2014 (Küng Citation2015). Despite this reputation, the organisation began producing investigative and long-form journalism in 2011, choosing Ben Smith as global editor-in-chief. A UK arm was launched in 2013, with Jim Waterson appointed as political editor.

Emerging as an underground counterculture magazine in Montreal in 1994, Vice's editorial style chimes with its abrasive and controversial founder, Shane Smith. It strongly opposes conventional orthodoxy in journalism, seeking to offer hip, edgy, alternative perspectives to the legacy media agenda. Despite its background in print journalism, Vice is best characterised as a digital-first news organisation (Nicholls, Shabbir, and Nielsen Citation2017). Vice Media is primarily associated with video journalism, producing and distributing documentaries online and on television, through collaborations with HBO and Showtime and on its cable channel, “Vice on TV.” Vice News launched in the UK in 2014.

Similarities exist in news production at BuzzFeed and Vice. Firstly, their networked and decentralised newsrooms are made up of predominantly young journalists (Küng Citation2015; Stringer Citation2018, Citation2020). Secondly, and as a result of this lived experience, both are heavily influenced by internet culture and the communicative norms on social media (Tandoc and Jenkins Citation2017; Stringer Citation2018, Citation2020; Tandoc and Foo Citation2018). Editors at BuzzFeed and Vice highlight how a distinctive digital vernacular shapes their editorial voice. Thirdly, both cover progressive issues, such as civil rights, drugs legislation, and mental health, that are either ignored by legacy media or not given the same level as exposure as traditional beats (Harmer and Southern Citation2019; Stringer Citation2018). This helps to distinguish these brands from their competitors.

There are also notable similarities in the audience for BuzzFeed and Vice. Both target a young demographic, aged between 18 and 30 years old (Stringer Citation2018). This influences the content of their journalism, as BuzzFeed News and Vice News draw on audience-orientated editorial practices (Stringer Citation2020). BuzzFeed is driven, in part, by analytics. By using attention and engagement metrics, the organisation measures audience preferences and feeds this into journalistic decision-making (Küng Citation2015; Tandoc and Foo Citation2018). At Vice, the editorial team recognise the tastes and dispositions of their young audience, drawing on “a more subjective and involved style of reporting” as a result (Stringer Citation2018, 1995).

Existing research has analysed: (1) the structure of these organisations and the makeup of their workforce (Küng Citation2015; Stringer Citation2020); (2) differences in norms and practices with legacy news media (Tandoc and Jenkins Citation2017; Tandoc Citation2018); and (3) the issue focus of news coverage (Stringer Citation2018). We add to the literature on digital-native news organisations through a textual and visual analysis of news content, evaluating how this unique editorial voice is represented through emotional storytelling.

Emotional Forms of Storytelling

BuzzFeed and Vice are examples of digital-native news organisations that combine entertainment and news, blurring the boundaries in journalism, and disrupting the definition of what journalism is and the practices and norms that it embodies (Lewis Citation2012; Chadwick Citation2013; Stringer Citation2018). By selectively adapting practices that lend legitimacy, both organisations introduce new forms of capital to journalism (Stringer Citation2018). This rejection of the dichotomous approach that opposes legacy media to digital-native news organisations is recognised by professionals. BuzzFeed journalists, for example, claim that they engage “in differentiation (what makes the brand unique) and de-differentiation (how this fits into legacy news media logics/practices)” (Tandoc and Foo Citation2018). Both organisations show, however, evidence of adopting legacy news media norms and practices: story preparation, ethical guidance, concerns in fact-checking and accuracy, and fair use of sources (Tandoc and Jenkins Citation2017; Stringer Citation2018; Tandoc Citation2018), including in contexts of election coverage (Harmer and Southern Citation2019; Thomas and Cushion Citation2019).

What these organisations do differently is to adopt elements of storytelling that are part of an emotional discourse at the diverse levels of production and reception of news texts. While this stands at odds with the dispassionate style of delivery associated with traditional journalism (Edgerly and Vraga Citation2020), emotional expression can facilitate audience understanding and engagement (Pantti Citation2010). For political topics, highlighting a personal angle or using emotive language can make a complex issue “softer” and more approachable for younger audiences (Edgerly and Vraga Citation2020).

This editorial style stands up well as an example of the presence of emotion as a defining element for journalism practice. This scrutiny of the election coverage by BuzzFeed and Vice contribute to the “emotional turn” (Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2020) in journalism studies, that pays particular attention to the “institutionalised modes in which emotions are constructed and circulate within media texts” (Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2019, 9). Studies in political communication highlight how entertainment could potentially bring a solution to a disengaged and apathetic public, rather than dumbing it down. In this sense, entertaining narratives, satirical news, and personalised news were defended as a more pleasurable mode for the consumption of political news (Zelizer Citation2000; Jones Citation2005; Van Zoonen Citation2005). This informalisation of news became evident with the popularisation of satire, and has shown journalistic discourses that avoid the formalism and distance habitually guarded by the ideal of objectivity (Cameron Citation2004). The informalisation of journalism, amplified now by the rise of internet and social media, in its turn, exists in tandem with the “informalization of politics” (Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2020), through which politicians increasingly communicate in a casual style, so they cultivate affective bonds with their voters. The informalisation of politics and journalism is part of what Wouters described as an “emancipation of emotions”. Wouters (Citation2007) traces these shifts in the management of public manners and emotions over time, and described a general social process of informalisation, an “emancipation of emotions”, that allowed the diminishing of social distancing.

Emotion becomes, in this sense, an essential element in the link between journalists, messages and audiences’ engagement. Journalistic formats that promote more informal narratives have flourished due to a lively and varied digital media ecology. Contemporary journalism exists in an emotionally charged networked environment, and our engagement with the world of news is increasingly personal and emotional, predominantly established through our mobile devices (Papacharissi Citation2014; Beckett and Deuze Citation2016; Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2020). This digital landscape and the emergence of digital-native news organisations that depart from established conventions of professional journalism has further challenged the conventional definitions of journalism and the normative ideal of objectivity. Papacharissi (Citation2014; Citation2015) refers to a rise of “affective news” – news that combines information with personal experience, opinion and emotion; these, in turn, bond more effectively with audiences or “affective publics”.

The media is not a separate objective experience that we engage with outside of emotions; our relationship with journalism is through the prism of everyday experiences, especially for political issues and during elections (Dennis Citation2018). Newer media invite people to feel their own place in current events and in the production and dissemination of news (Papacharissi Citation2014). The human factor is a central element in journalism, as Beckett and Deuze argue, and people “want the full range of emotions (…) as well as reliable and timely narratives. Trustworthiness in the networked journalism age is, we argue, increasingly determined by its emotional authenticity.” (Citation2016, 4).

Journalists at both BuzzFeed and Vice News are more willing to embrace personal and emotional forms of discourse that communicate directly to the readership while rejecting conventional, “objective” styles of journalistic storytelling (Stringer Citation2018). We suggest that these news organisations use a distinct emotional vernacular for their political and campaign reporting, that is the emotional discursive construction heavily centred on the digital environment and language, and internet vernacular developed within social media platforms, shaping, this way, their editorial voice.

Election Reporting at BuzzFeed and Vice

Journalists play a critical role during elections, acting as the primary source of information for citizens deciding whether and how to vote. News organisations are tasked with supplying the electorate with information from the competing parties and candidates, to help facilitate an informed citizenry. We draw on the 2017 UK general election as our sample because of this. Elections represent a unique moment where politics is at the forefront of everyday life, in which ordinary people pay attention and seek out political news. Whether news media fully perform this function is open to debate. Existing research on legacy news media has highlighted that, historically, journalists do not focus on policies. Instead, reporting is centred on the horserace between parties, the characteristics and personalities of candidates, and the process of the election itself, highlighting campaign strategies (Cushion and Thomas Citation2018; Harmer and Southern Citation2019; Thomas and Cushion Citation2019). In light of this, research on election reporting is predominantly focused on content.

Despite the majority of studies focusing on broadcast and print media coverage (Harmer and Southern Citation2019, 99), there is an increasing body of work exploring digital-native news organisations. The results show that BuzzFeed's coverage looks remarkably similar to legacy news media. Thomas and Cushion (Citation2019) investigate election reporting on the website in the 2015 and 2017 general elections. They found a notable shift in their editorial agenda, with BuzzFeed providing more coverage of policies, relying on institutional sources, and employing more journalists with a formal political specialism in 2017. Harmer and Southern (Citation2019) also analysed this latter election and highlighted the reporting on progressive topics, such as issues facing LGBTQ+ and ethnic minority communities. However, the focus on the horserace and personalities of the party leaders was still dominant. To date, there has been no academic study of election reporting on Vice News UK.

We deviate from this literature by examining the presence of emotional storytelling in the election coverage. While other studies have assessed objectivity in the reporting by BuzzFeed (Tandoc Citation2018; Tandoc and Foo Citation2018; Thomas and Cushion Citation2019) and Vice (Stringer Citation2018), there is a lack of research on how digital-native news organisations strategically use emotion in their political journalism. While Thomas and Cushion (Citation2019) examine tone in their study, the dichotomy of serious and humorous journalism overlooks the increasing hybridity between quality news and entertainment. Tandoc (Citation2018, 207) also focuses on objectivity. However, by coding for the presence of personal opinion in reporting, he recognises that this does not represent the strategic use of emotion as a storytelling device. This is significant, as research shows that journalists at BuzzFeed (Tandoc and Foo Citation2018, 49) and Vice (Stringer Citation2018, 1995) recognise that a conversational, subjective, and personalised style of news reporting is central to their brand.

Methods

This article explores how emotion is used in coverage of the 2017 UK general election from BuzzFeed News UK and Vice News. We identified two research objectives. Firstly, we seek to establish how emotional storytelling is used during the reporting of the campaign and describe the characteristics of the emotional vernacular that these news organisations embrace. Existing interview-based research with editors of BuzzFeed and Vice has identified that their reporting is more subjective than traditional outlets, adopting a personalised style that resembles the form and tone of everyday communication online (Stringer Citation2018; Tandoc and Foo Citation2018). We analyse how this emotional storytelling is represented in news content. Secondly, we aim to understand how emotional storytelling fits within the existing research on how digital-native news organisations report elections. Harmer and Southern (Citation2019) and Thomas and Cushion (Citation2019) use content analysis to show how election coverage from BuzzFeed News UK resembles the reporting norms of legacy media competitors in its focus on the process of the election and the personalities involved. We contribute to this literature by analysing how emotional elements in media texts intersect with existing election reporting practices.

We use qualitative textual analysis to examine these objectives (see, for example, Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2018). All articles were coded manually using three analytical categories to identify the presence and function of emotional storytelling devices. Firstly, language and tone, referring to the wording, tone, and style of the text. Secondly, visual, formatting, and interaction, alluding to imagery, visual structure, and opportunities for audience engagement. These categories provide a more holistic sense of how emotion is deployed within election coverage by examining language alongside visual cues and interactive opportunities. This is central for these news sites, as both have a reputation for innovation in these areas: BuzzFeed for quizzes and humorous imagery and Vice for its focus on visual narratives (Beckett and Deuze Citation2016). Furthermore, existing work on the election reporting of digital-native news organisations focuses predominantly on content (namely, text), rather than interactive and visual design (Thomas and Cushion Citation2019, 1335).

Our third category is production and editorial choices, and examines the organisation of content, themes, and storytelling strategies used. By using behavioural analytics and trending topics on social media to guide editorial decision-making, digital-native news organisations have been accused of prioritising light-hearted and shallow “clickbait” content that captures the attention of social media users (Tandoc Citation2018; Stringer Citation2020). This is particularly significant as BuzzFeed and Vice rely on distributed discovery, whereby users find content via digital intermediaries like Facebook for their audience (Küng Citation2015; Nicholls, Shabbir, and Nielsen Citation2017; Stringer Citation2020). Research shows that emotional cues can trigger such engagement (Pantti Citation2010; Beckett and Deuze Citation2016). The organisation of content and editorial style is a central element to understand the possibilities for this engagement with their audiences. We draw on studies on the communicative architecture of news that reflect on how news are routinely organised, the resources used, how issues are communicated, and what topics are prioritised (Cottle and Rai Citation2006; Sampaio-Dias Citation2016).

We consider all articles related to the 2017 UK general election published from its announcement in parliament until polling day, inclusive (19/04/2017 to 08/06/2017). As illustrates, the sample consists of 280 articles in total. The imbalance in the sample can be explained in several ways. Firstly, in general, BuzzFeed News UK had more staff than Vice News UK in 2017; 44 of the 140-strong team at BuzzFeed UK were journalists (Kanter Citation2018), compared to a staff of 21 at Vice (Ponsford Citation2016). Secondly, political reporting was an editorial priority for BuzzFeed at the time, with investments made in specialist reporters (Thomas and Cushion Citation2019, 1338). Finally, although Vice had a smaller overall total, articles tended to be longer. While BuzzFeed reported the day-to-day changes in the campaign, Vice provided a more detailed analysis of specific issues.

Table 1. Details of sample.

Data was collected from relevant sections and topics associated with the election. For BuzzFeed, articles were organised in their Politics section and signified by an “Election 2017 badge”, a label that the organisation uses to categorise content. Vice organised its coverage across five overlapping sections: Election 2017, General Election, General Election 2017, Oh Snap, and Tory Week. To increase the transparency of our empirical work, we include links to the full dataset and attach this as an online appendix. Each article has been assigned a unique identification number to point readers to specific examples of coverage.

This study faces some limitations. Notably, we do not account for the context of production and how journalists experience this, nor how the audience reacted to the coverage. We draw on Fürsich's defence of textual analysis in journalism research, highlighting that this approach can reveal “the narrative structure, symbolic arrangements and ideological potential of media content” (Citation2009, 239).

Language and Tone

Both Vice and BuzzFeed draw on terminology that is representative of their young and digitally-savvy audience. This was evident in BuzzFeed's headlines, such as “Tim Farron Vs A Pro-Leave Pensioner Is The Most WTF Moment Of The Election So Far” (38). The language in this article, however, is formal and represents the storytelling conventions that we would associate with legacy news media outlets. In “Jeremy Corbyn Slid Into The Comments Of Theresa May's Facebook Live Event To Challenge Her To A Debate” (89), the organisation adapts the phrase “slide into the DMs.” This is a colloquial expression used most commonly by young people in digital contexts to refer to someone sending a direct message on social media, generally to a romantic prospect, in a smooth fashion. The article itself does not refer to the phrase. This disconnection in style between the headline and the story was a common feature across the sample. It points towards how BuzzFeed relies on distributed discovery for their audience, capturing the attention of users on social media feeds by adopting the norms of expression on these platforms.

Other headlines illustrate what Beckett and Deuze (Citation2016, 3) describe as the curiosity gap, enticing a reader to click on a link through the promise of revelatory information. “Here's Why The General Election Will Actually Be Really Fascinating” (1), is a rigorous analysis of polling data to identify key marginal constituencies. This was also the approach used in a piece on the methodology of polling (80) and “These Are All The Parliamentary Reports You May Have Missed Before The Election” (40). In the excitement of an election, it might come as a surprise that BuzzFeed provided a summary of findings from reports published by parliamentary select committees before parliament was dissolved. These articles are significant as they distinguish this practice from accusations of clickbait, where deceptive headlines are used for attention. Instead, conversational headlines direct audiences to long-form, quality journalism.

A conversational tone is interweaved with more refined writing throughout all Vice News coverage. There are several linguistic tools that confirm this tone, strengthening Vice's connection to its younger readers. Perhaps the most striking tool adopted is cursing. Vice is famously comfortable with swearing and uses it as an instrument of strategic emotionality (Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2019). Firstly, foul-mouthed coverage (either quoting interviewees or in the journalist's own words) is a form of identification with readers while affirming, at the same time, their reputable edginess. Secondly, cursing is also used as a hook to more serious pieces. In the latter case, swearing is added sparingly in opinion pieces, or in the headlines, but not necessarily anywhere else in the text. Titles such as “Labour Needs to Do More for People in Crap, Unstable Jobs” (213) and “The Tories’ Mental Health Proposals Are Utter Bullshit” (223) are examples of swearing as strategically used to grab the attention for long-reads on central social issues, covered in a more formal language and deeper content, resembling the reporting style in legacy media. Cursing is generally used mildly but consistently throughout the sample, except in occasional pieces that seem to read like a script for a stand-up act. In these, profanities are abundant and confirm tones of sarcasm and anger. For example, in an unconventional newspaper round up the day after the announcement of the snap election, author Joel Golby comments on the front-cover of the Sun:

You’ve got to hand it to the Sun, that intolerance-inciting shitrag, for having the election-themed headline “BLUE MURDER” less than 12 months after the death of MP Jo Cox, who was killed at the peak of Brexit hype last June. I mean, I might be being sensitive here, but it's very much more likely that the Sun is being fucking dead-brained and moronic, again, isn't it. (193)

Like “Kid A” and “To Pimp a Buttery” before it, the Labour Party's manifesto has been leaked ahead of the official release date. But, just like those era-defining albums, the leak might have ended up serving its authors well: everybody is talking about it, and they’ll get a chance to talk about it again when it's properly launched next week. (224)

All aboard for the bi-annual Being Savaged By a Dead Sheep Finals. In the red corner: Jeremy “Herbivorous Mugwump” Corbyn and his view that we should fill our Nautilus subs with pressed daisies and aim these bouquets of love at Moscow. In the blue, Theresa “Melting Animatronic” May and her revolutionary idea that we should all trust her because she keeps her Brexit notes in alphabetised ring-binders with tabbed dividers and reinforced sticky-backed plastic. (240)

Although the language of much of the coverage adopts a similar style to election reporting in legacy news media, humour still serves several functions for BuzzFeed. Firstly, some articles are designed to entertain. Although stories such as “18 Photos Of British Politicians Improved By ‘Game Of Thrones’ Quotes” (39) and “Would You Like To Smell Tim Farron's Spaniel?” (19) do refer to electoral topics, they do not interpret the broader political significance. Secondly, and most frequently in the sample, humour acts as a gateway to serious political content, particularly evident in the coverage of May's campaign. Subject to widespread criticism, BuzzFeed occasionally drew on sarcasm to illustrate this. Rather than the journalist editorialising or quoting critiques from expert sources, they curated the Prime Minister's own words to make this point, such as transcripts of questions that she failed to answer (149), or a list of the 57 times that Theresa May had used the slogan “strong and stable leadership” during the first nine days of the campaign (24). Finally, evidence of humour can also be seen in the URLs of the articles. Here, readers can find “easter eggs,” secret jokes hidden for the most observant. In an exclusive, BuzzFeed revealed that one month into the campaign, Jeremy Corbyn had only visited two of the Labour Party's 100 most vulnerable seats. This was contrasted to his visit to Sheffield, Brightside and Hillsborough, a constituency with a 34.5% majority. The URL for this story contains the phrase “open-up-my-eager-eyes-im-sheffield-brightside” (95), an adaptation of the lyrics from the popular song Mr Brightside by The Killers.

Visual, Formatting and Interaction

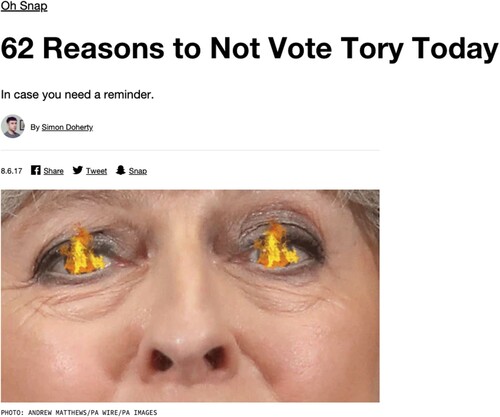

Like its language and tone, the imagery on Vice News was also controversial. Articles were illustrated with purposely unfavourable photos of political figures. May was represented showing unlucky facial expressions, or during inopportune mouthful “chip-eating” moments, making evil faces, or in inconvenient poses where her shadow seemed to give her an extra pair of arms (evoking a threatening spider). Corbyn was often portrayed making goofy faces, and also in inconvenient fraction-of-a-second shots where he seemed to inappropriately kiss an elderly lady. The Labour leader, however, was not as vilified as the Prime Minister, who was never portrayed favourably. These choices reflect and strengthen their provocative tone. , for example, shows a photo manipulated to depict a flaming-eyed Theresa May (274).

By curating content from across the social web, predominantly Instagram and Twitter, visual humour was a key feature of storytelling for BuzzFeed News. Several pieces were made up entirely of amusing images from social media users, which were either embedded into the article or captured as a screenshot. The purpose of these pieces varied. Some were compilations of what authors deemed to be engaging content (156; 184). Journalists such as Robin Edds worked exclusively on this, bringing together memes, jokes, and comical photography. In amplifying viral content, BuzzFeed taps into the distinctive emotional vernacular developed within social platforms. For instance, contributions often reference pop culture, such as the revered, 80s films Home Alone (58) and Die Hard (75) shown in .

Others adapted images to fit a specific narrative. Fiona Rutherford examined reactions on Twitter to Theresa May's confession that the naughtiest thing she had ever done was to “run through fields of wheat” (161). Matthew Champion explored how Labour Party MP, Ed Miliband, used humour to discredit opponents and highlight similarities between the Conservatives manifesto and the 2015 Labour manifesto that he stood on as leader (41).

Regarding format, lists were commonly used across the sample for BuzzFeed. The majority of articles that used a list structure were examples of serious election reporting. Some simplified complex stories, such as polling data (152) and party manifestos (70), explaining the priorities of young people and the policies that would affect them. Others provided guides to help their young audience understand the practicalities of the election, such as a breakdown of seats that the SNP could lose (7) and an hour-by-hour guide to election night (179), explaining the significance of the exit poll, the importance of timing in the reporting of the results, and the seats that could determine the outcome of the contest.

Quizzes, another staple of BuzzFeed, were also used. “Can You Guess Who These Dogs Are Going To Vote For?” is a quintessential example of the organisation's approach, fusing humour, pictures of cute animals, and a viral moment on social media (170). While journalists at legacy news media have dismissed the seriousness of the organisation because of their typically frivolous tone (Tandoc and Jenkins Citation2017), some of those created during the election were designed to educate and entertain. This included providing historical knowledge of British politics (173) and raising awareness of manifesto commitments (107). This interactive content is humorous in tone but informative in substance, providing details to help their audience cast their vote.

Vice's election reporting also displayed interactive elements, including materials that complemented the written coverage (links to their election podcast, documentaries or videos). Pieces often included links to register to vote, as part of mobilisation efforts that we will explore further in the next section of our analysis.

Production and Editorial Choices

This section analyses the editorial and political choices that affect the (a) organisation of content, (b) focus and angle, and (c) themes and topics.

Organisation of Content

BuzzFeed and Vice organised their election coverage in specific sections that reflect their editorial vision and aim to connect with their audience. Both produced serious election reporting that simultaneously embraced the norms of communication and sharing on social media.

While the majority of content was organised under the badge “Election 2017,” BuzzFeed included two substantive sections that illustrate this approach. Election 2017 Debunked featured a collection of stories correcting false information shared online. These articles came in two formats. Firstly, exposés of inaccurate viral images from social media, such as an image of a woman making an offensive hand gesture at Jeremy Corbyn while canvassing (74). Secondly, BuzzFeed posted long-form rebuttals to misinformation that was of direct relevance to their target audience. For example, Tom Phillips combined data from the Office for National Statistics, polling firm Ipsos, and a survey from the Higher Education Policy Institute to contest a tweet claiming that if more people under 25 voted, it would swing the election in Labour's favour (90).

The BuzzFeed Social Barometer provided a weekly insight into the most shared links about the general election across social media. The results illustrated a remarkably different picture to the agendas present in traditional media. The most shared stories were overwhelmingly positive about the Labour leader (54), reflected on significant levels of youth engagement (85), and revealed the popularity of alternative, left-wing news sites, such as Another Angry Voice, Evolve Politics, and The Canary.

Vice also entwined traditional forms of journalism with their renowned Gonzo style, exemplified by the two sections Oh Snap and Tory Week. These sections displayed a lively, participatory writing style showing the author as the protagonist, and providing a combination of social critique and self-satire, including the telling of intimate anecdotes, personal experiences and emotions. Some of the pieces drawn upon humour and entertainment, using sarcasm, exaggeration and swearing and, while others disclosed personal accounts, appeals and displays of personal emotion. Oh Snap acted as the main category for traditional forms of reporting, but still instilled generalised feelings about the upcoming election; for example, dreading the election itself, as the opening of the section said:

Welcome to VICE's Coverage of the Worst Election Ever

Join us in hell's waiting room.

Once every five years – or, apparently, “whenever the government feels like it” – we’re treated to a jamboree of sketchy promises, stump speeches in empty out-of-town warehouses and rosette-wearing nerds knocking on your door attempting to make some sort of connection. It falls to political journalists to whip the public into a frenzy, or at least make the people give a shit. (212)

Tories – they live amongst us, yet we know so little about them. Okay, yes: they’re generally in favour of keeping everything exactly the way it is, because that's been working out just fine. We know that. They’re the least compassionate of all parties. We know that to be true. They present themselves as inherently the most reliable. We know that to be dubious. We know all this, yes, but what about the stuff we don't know? What's it like to live the life of a Tory – to spend your weekends drinking champagne and playing cricket in idyllic Middle England, or buying a £3.5 million house like the housing crisis doesn't even exist? (247)

Focus and Angle

BuzzFeed amplifies youth voices in its coverage. Drawing on extensive interview quotes and social media posts, it provides first-hand accounts of how issues affect individuals. This includes what workers in the gig economy thought of the manifestos (103), why young people may abstain from voting (114), and views on proposals to scrap tuition fees for university study by the Labour Party (68). One article focused on “Bun the Tories”—bun as slang meaning forget or fuck—a campaign led by young Labour supporters designed to reach apathetic young people from minority groups (174). The piece interviews one of the founding members, exploring the efficacy of Instagram as a campaigning tool, and a number of those who had purchased stickers and badges, raising funds for a homeless shelter in the process. These interviews highlighted how personal experiences were key to understanding why the campaign resonated with people.

Furthermore, in a story focusing on the marginal seat Birmingham Edgbaston (150), we see large images of young voters and can read their voting intentions. Spanning over 2,500 words and drawing on quotes from 11 interviewees, this piece weaves together an analysis of key issues facing younger generations with testimonies of what they mean in their day-to-day life. Entitled “Could Young Voters Swing The Election Result? In This Key Seat, They Say They Can”, it illustrates the impact and efficacy of youth engagement on a personal level.

Vice's storytelling style adopts a personal approach to journalism, but from the perspective of the author, reporting individual experiences and emotions as part of the election coverage. We found examples of the journalists’ exposure of private emotions in long reads and investigative pieces, such as this example from an article on the illicit use of data to target political advertisements:

Greetings, fellow young people. Much like you, as a millennial I spend my time surfing the web, browsing my favourite internet websites and applications. Like my peers I have mastered the disciplines of scrolling, liking and sharing. Typically, I also have a casual disregard for my personal data and regularly volunteer the intimate details of my character to corporations, for the price of a clever new way to make my face look like a wasp or puppy. As such, I am prey to dark forces. (236)

Yes, I’ve booked a viewing. But before I arrive I need a makeover. I genuinely live in a shed and eat curly fries three nights a week, and you can absolutely tell it from looking at me. (…). I need to become a Tory. Turns out, all you need to do that – looks-wise, at least – is a comb, a white M&S shirt and some trousers your nan would approve of. (242)

But who is this capacious “we”? One answer we’ve been telling ourselves recently: young people. You. Me. The millennials – to use a demographic-cum-marketing term that we once laughed off – who came of age as Lehman Brothers collapsed; who cruised through the decade with receding job prospects, stagnant wages and mushrooming debt. Precarious, jaded, polarised. Too scared to reproduce. Sympathetic to radical politics. (217)

Themes and Topics

As Harmer and Southern (Citation2019) identify, BuzzFeed extensively covered the process of the campaign and how the election was reported across legacy news media but also gave prominence to progressive issues. Many of these topics anticipated the priorities of younger voters, such as the gig-economy (33; 103), LGBTQ+ rights (15; 112; 126), and the digital campaign (118; 142; 148; 158; 168). One issue in particular stands out due to the volume of articles: how the election affected ethnic minority communities.

Reporters Aisha Gani and Fiona Rutherford focused on the political efficacy of BAME citizens. This included examples of effective advocacy, such as the Muslims for Change initiative, set up to crowdfund for candidates who committed to challenging anti-Muslim sentiment (71), and the hashtag #AbbottAppreciation (165), where Twitter users shared positive stories to celebrate Diane Abbott's achievements in politics after the shadow home secretary stepped back from the campaign due to illness. Gani also published a detailed interview with Sahar Al-Faifi, a molecular geneticist who toured TV studios defending face coverings following the announcement of a UKIP policy to ban them (22). This piece reflects on Sahar's personal experiences of wearing a niqab in everyday life and the emotional impact of her media exposure, from the joy in receiving messages of support to being called a “fucking bomber” by a member of the public during a live BBC interview. With the title “This Muslim Woman Who Wears Niqab Spent Most Of This Week Shutting Down Haters,” the feature is designed to celebrate the courage of Sahar.

Furthermore, BuzzFeed also focused on informing about options at the ballot box by providing a summary of policies targeting ethnic minority voters (147). This is accompanied by expert analysis from academics and relevant professionals and is framed around the inequalities that ethnic minorities experience in everyday life:

Life in the UK comes with a different set of challenges for ethnic minorities. If you have a foreign-sounding name it's harder to get a job. Even with a degree you can expect to earn around 10% less than your white counterparts. You are more likely to access mental health services through the back door – through the courts or the prison system, for example – rather than via a GP. And research repeatedly shows worse health outcomes for people from black, Asian, and minority ethnic (BAME) backgrounds.

This is all the more reason why ethnic minorities should be voting in this year's general election, but, historically, they’re among the least likely to head to the polls.

What becomes clear about Vice News’ coverage is that they voiced a fierce criticism against the Conservatives, and, in particular, against Theresa May. The coverage slowly evolved to an appeal in supporting anything but the Conservatives, presenting Corbyn initially as weak or inflexible, but then as the best possible chance to defeat May. They have portrayed a fragile and fragmented Labour Party and depicted the Conservatives as rich, posh, elitist and shallow. Along with provocative criticism, Vice News pushed a more serious agenda raising awareness for LGBTQ+ rights (211), anti-racism (231), and other themes related to social injustice. In the week before the election, Vice shared a series of long-form, traditional investigative reporting, tagging these as Vice Manifesto, introducing it with the statement:

There are loads of things wrong with this country that aren't being discussed enough in this election. Until the 8th of June we’ll be talking about all of them. Today: hidden homelessness. (249)

Further, they distilled feelings of apathy and a sense of unrepresentativeness towards current politics and politicians, moving then to passionately convince its readers to register to vote. As the election day loomed, Vice appealed to their audience not to vote Conservative. For example, with attention-grabbing titles such as “How the Tories Fucked the Country” (270), or “62 Reasons to Not Vote Tory Today” (274), in an editorial effort to avidly convince their readers. And Vice News seemed to be well aware of the power of this demographic group; on the day of the election, Vice wrote the following piece: “Don't Just Vote: Swing the Vote. This whole election now comes down to youth turnout. That means we’re going to have to do more today than put an X in a box.” The article went on to explain:

How you vote is up to you. But it's not enough just to vote today. You need to do more. (…) Think patiently about why you’re voting the way you are, and then post a personal message to tell others to do the same on Facebook, Instagram or Snapchat. If you’re heading to work or university, make voting the only thing you talk about. Buy anyone who's voted for the first time a drink, then get them to do the same to someone else. That's just a start. (275)

Discussion and Conclusion

By analysing coverage of the 2017 UK general election from BuzzFeed News and Vice News, we argue that both use emotion to connect with their young audience. They do this by adopting a language and visual style that are relatable to them: conversational tone, swearing, internet culture terminology, pop culture references, for example. All these elements contribute to the informalisation of campaign reporting as a form of narrating politics to an audience that is perceived to be disengaged and apathetic towards politics. The emotional vernacular of campaign reporting is translated by this effort to speak directly to the audience. In doing so, we provide evidence of the audience-centric storytelling that staff at BuzzFeed (Tandoc Citation2018; Tandoc and Foo Citation2018) and Vice (Stringer Citation2018) have identified in interview-based research.

The coverage from both represents a split between emulating existing election reporting norms and innovating by using emotional language and imagery to engage young people (Stringer Citation2018). To varying degrees, formal practices are embedded in a broader structure of humour. This fusion of legacy norms and innovation is significant within the context of election reporting and work as their own rituals of strategic emotionality (Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2019) that help develop an audience-centric voice for the young electorate.

We argue that these creative, funny, and provocative forms of emotional storytelling used to make election reporting engaging are significant. The aggregation of comical content from across the social web by BuzzFeed News and the provocative reporting from Vice News should not be casually dismissed as clickbait content. The journalistic work to wrap election reporting in an appealing, youth-focused, narrative illustrates evidence of innovative audience-orientated practice. It is further evidence of boundary-blurring, merging news genres, such as hard news/soft news, and formats, like factual/interpretive content (Lewis Citation2012; Chadwick Citation2013; Edgerly and Vraga Citation2020).

Past research has observed how social media is key to understanding the editorial priorities of BuzzFeed and Vice, from the focus on viral stories (Stringer Citation2018, Citation2020) to the reliance on distributed discovery (Nicholls, Shabbir, and Nielsen Citation2017). We also propose that the emotional style used by both draws on the affective norms and modes of expression used on social platforms; BuzzFeed and Vice tap into the vernacular of the internet and social media, one formed around emotive expression, humour, and provocation (Papacharissi Citation2014; Phillips Citation2015).

Here, the young newsrooms play a crucial role (Küng Citation2015; Stringer Citation2018) and reflect their target audience. These journalists themselves are immersed in internet culture and understand the subtleties of digital communication. Through this lived experience, journalists at BuzzFeed and Vice authentically draw on forms of emotional storytelling that exist online. For their young audience who are exposed to this content on social media, emotion acts as a gateway to informative political journalism. Whether through BuzzFeed's headlines or the swearing present in Vice's coverage, this style of election reporting is attractive to this audience because it feels like a contribution from a friend. Indeed, as the quote from BuzzFeed News Editor Alan White at the start of this article shows, it is explicitly designed in this way.

The impact of this emotional vernacular on the norms of election reporting, and its utility for young voters, requires further research. We contend that much of the coverage is useful for the electorate, meeting the conditions of what journalism should be: articles are fact-based, built on wide-ranging expertise, and designed to provide reliable information to aid young citizens in a core democratic act (Eldridge Citation2019, 859). For BuzzFeed News UK, while its focus on the process and personalities of the election resembles the coverage of legacy media competitors (Harmer and Southern Citation2019; Thomas and Cushion Citation2019), our study illustrates how emotional storytelling differentiates the brand.

The results for Vice are less clear. Much of the coverage was ideological in tone, with explicit appeals for its readers to withhold support from the Conservative Party. However, we do not believe that this is a simple case of partisanship seen in the election coverage of tabloid news outlets. Rather, this illustrates how journalism as a profession, and the norms and practices associated with it, are in a state of flux (Eldridge Citation2019). Just as we see debates over the objective ideal, informalisation, and the merits of soft news, this represents the tensions of the emotional turn in election reporting. The provocative tone of Vice's reporting attracts the attention of younger readers and provides a gateway to detailed analysis of social issues, but these reflect an agenda that is often associated to a left-wing orientation. We suggest this represents a different type of boundary blurring; Vice rejects the sourcing practices and horserace coverage drawn upon by BuzzFeed, instead drawing on a more evidently militant voice to support their reporting. In this way, Vice resembles what Eldridge (Citation2019, 857–858) describes “interloper media”, “who originate from outside the boundaries of the traditional journalistic field, but whose work nevertheless reflects the socio-informative functions, identities, and roles of journalism.”

Such a conclusion is significant for future research on the role of emotional storytelling in election coverage. The closure of BuzzFeed News UK in 2020 and the sizeable layoffs at Vice News UK pose questions about whether this emotional vernacular will be present in the reporting of future elections. We add to the literature on digital-native news organisations by recognising innovation in journalistic practice. Alongside the pioneering use of data science to inform editorial decision-making (Küng Citation2015; Stringer Citation2018, Citation2020), journalists at BuzzFeed and Vice have also developed this emotional vernacular to speak with authenticity to younger audiences. In the aftermath of the aforementioned financial challenges, staff are taking these skills to new locations, with several taking up positions at Bloomberg (Fiona Rutherford, BuzzFeed), the Guardian (Jim Waterson, BuzzFeed; Yohann Koshy and Tess Reidy, Vice), and the Sunday Times (Emily Dugan, BuzzFeed). Further research should examine whether this approach to storytelling is adapted when writing for legacy news media to understand how these digital-native news organisations have had on informalisation in news production more broadly.

Acknowledgements

We thank Milan Kreuschitz-Markovič for his assistance throughout this project. We are also grateful to the guest editors, Karin Wahl-Jorgensen and Mervi Pantti, and the anonymous reviewers for Journalism Studies for helping us develop this paper and more clearly articulate our contribution. Any errors or shortcomings are our own.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Beckett, C., and M. Deuze. 2016. “On the Role of Emotion in the Future of Journalism.” Social Media+Society 1 (1): 1–6.

- Cameron, D. 2004. “Truth or Dare?” Critical Quarterly 46 (2): 124–127.

- Chadwick, A. 2013. The Hybrid Media System. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cottle, S., and M. Rai. 2006. “Between Display and Deliberation: Analyzing TV News as Communicative Architecture.” Media, Culture & Society 28 (2): 163–189.

- Cushion, S., and R. Thomas. 2018. Reporting Elections. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Dennis, J. 2018. Beyond Slacktivism. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Dennis, J., and S. Sampaio-Dias. 2017. “Not Just Swearing and Loathing on the Internet: Analysing BuzzFeed and VICE During #GE2017.” In UK Election Analysis 2017, edited by E. Thorsen, D. Jackson, and D. Lilleker, 66–67. Bournemouth: Bournemouth University.

- Edgerly, S., and E. K. Vraga. 2020. “Deciding What’s News: News-Ness as an Audience Concept for the Hybrid Media Environment.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly. Advance online publication, 1–9.

- Eldridge, S. A. 2019. “‘Thank God for Deadspin’: Interlopers, Metajournalistic Commentary, and Fake News Through the Lens of ‘Journalistic Realization.’” New Media and Society 21 (4): 856–878.

- Fürsich, E. 2009. “In Defense of Textual Analysis.” Journalism Studies 10 (2): 238–252.

- Harmer, E., and R. Southern. 2019. “Alternative Agendas or More of the Same? Online News Coverage of the 2017 UK Election.” In Political Communication in Britain: Campaigning, Media and Polling in the 2017 General Election, edited by D. Wring, D. Mortimore, and S. Atkinson, 187–208. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Jones, J. 2005. Entertaining Politics: Satiric Television and Political Engagement. New York: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Kanter, J. 2018. Inside BuzzFeed UK's ‘Brutal’ Jobs Cull. January 29. https://www.businessinsider.com/inside-buzzfeed-uk-brutal-jobs-cull-2018-1/.

- Küng, L. 2015. Innovators in Digital News. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Lewis, S. 2012. “The Tension Between Professional Control and Open Participation.” Information, Communication & Society 15 (6): 836–866.

- Nicholls, T., N. Shabbir, and R. K. Nielsen. 2017. The Global Expansion of Digital-Born News Media. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, University of Oxford.

- Pantti, M. 2010. “The Value of Emotion: An Examination of Television Journalists’ Notions on Emotionality.” European Journal of Communication 25 (2): 168–181.

- Papacharissi, Z. 2014. Affective Publics: Sentiment, Technology, and Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Papacharissi, Z. 2015. “Toward New Journalism(s) Affective News, Hybridity, and Liminal Spaces.” Journalism Studies 16 (1): 27–40.

- Peters, C. 2011. “Emotion Aside or Emotional Side? Crafting an “Experience of Involvement” in the News.” Journalism 12: 297–316.

- Phillips, W. 2015. This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things: Mapping the Relationship Between Online Trolling and Mainstream Culture. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Ponsford, D. 2016. Vice News UK Recruits Eight Journalists Ahead of Launching Nightly Half-Hour TV Newscast. October 17. https://www.pressgazette.co.uk/vice-news-uk-recruits-eight-journalists-ahead-of-launching-nightly-half-hour-tv-newscast/.

- Sampaio-Dias, S. 2016. Reporting Human Rights. New York: Peter Lang.

- Sloam, J., and M. Henn. 2018. Youthquake 2017: The Rise of Young Cosmopolitans in Britain. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Stringer, P. 2018. “Finding a Place in the Journalistic Field: The Pursuit of Recognition and Legitimacy at BuzzFeed and Vice.” Journalism Studies 19 (13): 1991–2000.

- Stringer, P. 2020. “Viral Media: Audience Engagement and Editorial Autonomy at BuzzFeed and Vice.” Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture 15 (1): 5–18.

- Tandoc, E. C. 2018. “Five Ways BuzzFeed Is Preserving (or Transforming) the Journalistic Field.” Journalism 19 (2): 200–216.

- Tandoc, E. C., and C. Y. W. Foo. 2018. “Here’s What BuzzFeed Journalists Think of Their Journalism.” Digital Journalism 6 (1): 41–57.

- Tandoc, E. C., and J. Jenkins. 2017. “The BuzzFeedication of Journalism? How Traditional News Organizations are Talking about a New Entrant to the Journalistic Field Will Surprise You!” Journalism 18 (4): 482–500.

- Thomas, R., and S. Cushion. 2019. “Towards an Institutional News Logic of Digital Native News Media? A Case Study of BuzzFeed’s Reporting during the 2015 and 2017 UK General Election Campaigns.” Digital Journalism 7 (10): 1328–1345.

- Van Zoonen, L. 2005. Entertaining the Citizen: When Politics and Popular Culture Converge. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Wahl-Jorgensen, K. 2018. “Media Coverage of Shifting Emotional Regimes: Donald Trump’s Angry Populism.” Media, Culture & Society 40 (5): 766–778.

- Wahl-Jorgensen, K. 2019. Emotions, Media and Politics. Cambridge: Polity.

- Wahl-Jorgensen, K. 2020. “An Emotional Turn in Journalism Studies?” Digital Journalism 8 (2): 175–194.

- White, A. [aljwhite]. 2020. Tweet. May 13. Accessed June 6, 2020. https://twitter.com/aljwhite/status/1260658829571747844.

- Wouters, C. 2007. Informalization: Manners and Emotions Since 1890. London: Sage.

- Zelizer, B. 2000. “Foreword.” In Tabloid Tales: Global Debates over Media Standards, edited by C. Sparks, and J. Tulloch, ix–xi. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield.