ABSTRACT

This article focuses on the role of passion in news journalism from a managerial perspective. The analysis is based on a data set of 40,621 web-based job advertisements obtained from Journalismjobs.com, from the year 2002 to 2017. The quantitative analysis shows that passion has been on the rise as only 4% of the job advertisements in 2002 asked for “passionate” journalists, increasing to almost 16% in 2013. The authors also performed a qualitative analysis of job advertisements mentioning the word “passion” for the periods 2002–2003 and 2017. These advertisements express a shift from a normative role of journalists to journalism as an activity: when mentioned within the context of personal character, the desired temperament of journalists has given way to descriptions of desired behaviour. The normative focus on journalism as an ideal has decreased while the focus on performance—that journalists should feel passionate about reporting and storytelling—has risen dramatically. In the texts, passion emerges as something that can be applied in a range of contexts as a strategic resource. The findings point to commodification of feelings and exploitation of emotional labour in journalism.

Introduction

The digital transformation of the news media sector and the subsequent crisis in journalism has forced media managers to rethink their business models and become more innovative (Lehtisaari et al. Citation2018; Villi et al. Citation2020). After the financial crisis in 2008 some newsrooms have embraced the ethos of entrepreneurial journalism as a way to achieve salvation. Entrepreneurial journalism can be expressed by enterprising individuals who harness digital technologies (Briggs Citation2012; Cohen Citation2015), or then manifested in the renewal of journalism by addressing new niches, exploring new styles and formats, and building a new relationship with the audiences (Ruotsalainen and Villi Citation2018).

In this article, we connect entrepreneurship and emotions in journalism by focusing on journalistic passion from a managerial perspective. We explore how media managers convey the need to hire passionate journalists through analysing advertisements from the US web site Journalismjobs.com. Our article is grounded in the use of the word “passion” in the texts. The managerial perspective is connected to industrial efficiency and organisational success, which have spread to the private and public sectors, including the news media (Waldenström, Wiik, and Andersson Citation2019). The managerial perspective concerns the structure, processes and operations of an organisation, including human resource management (Raviola and Hartmann Citation2009); management itself is the process of giving direction, providing leadership and deciding how to use resources to accomplish organisational goals.

We trace the rise of passion in news media to the attention economy (Davenport and Beck Citation2001: Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2016; Wu Citation2016), social and digital media (Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2020), together with passion in entrepreneurship (Hamel Citation1999; Cardon et al. Citation2009; Maas and Ester Citation2016). This combination is the mix that makes up the so-called Silicon Valley discourse (Lindén Citation2020). It is celebrated in the ethos of entrepreneurial journalism in which an entrepreneurial skill set—and mind set—is seen as being vital to the renewal and future of the journalistic field (Briggs Citation2012; Pein Citation2014; Vos and Singer Citation2016). As Deuze and Prenger note:

Passion is the extreme emotional energy that keeps the engine running, both in terms of how workers make sense of themselves and their role in the ‘creativity machine’ of the media industries, and how the work gets ‘sold’ to newcomers and outsiders: as something you have to be passionate about. (Citation2019, 24)

Similarly, Couldry and Littler (Citation2011) connect passion to the work culture of contemporary neoliberalism and the demand for unlimited commitment to the employer's needs. However, there is a gap in understanding the strategic aspects of linking journalism and passion. In this, our paper contributes theoretically by critically examining emotions in journalism from a managerial perspective.

Audience Engagement

The rise of passion in journalism can be tracked to the emergence of digital media and social media platforms that rely on more emotional and embodied forms of storytelling (Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2020). Social media became gradually established in newsrooms between 2005 and 2010 (Belair-Gagnon Citation2015). Orgeret (Citation2020, 294) notes that: “As digital journalism is interactive, multi-platform, multi-linear and participatory, audiences’ emotions are projected back to the journalist more or less immediately.” Audience engagement has become a strategic resource to survive in the digital age (Lischka Citation2020).

Audience engagement is a somewhat confusing concept (Nelson Citation2018) that in essence “refers to the cognitive, emotional, or affective experiences that users have with media content or brands” (Broersma Citation2019, 1). Traditionally, journalists have shown little interest in engaging with the audience, and this question has not been at the forefront for the media industry until lately, even as social media and other online platforms allow better opportunities for audience engagement. Some of the forerunners in audience engagement are US-based digital news start-ups such as Buzzfeed, Quartz and Voice of San Diego that have built their business models on emotions and integrated it in their editorial processes, with sophisticated readership metrics to track the impact (Hansen and Goligoski Citation2018).

At Quartz, reporters are free to choose the subjects they care most about (their so-called “obsessions”) if they are related to the business topics Quartz covers (Küng Citation2015; Ruotsalainen and Villi Citation2018). And looking at the audience, Quartz sees “love” as a foundation for the business model. According to Sari Zeidler, its former director of growth:

We can see how often people are returning and what journey they’re taking down the funnel, but what we really want to know is do they love us, and how do we impact them? That's what journalism is about: Did we have an impact on their life? (interviewed in Kramer and O’Donovan Citation2019)

In Sweden, Tenor (Citation2019) finds that one of the main driving entrepreneurial forces of the people behind so-called hyperlocal media is “passion.” Overall, journalists need to come across as taking part in the discussion, being passionate about their jobs and open about how they perceive the world (Ruotsalainen, Hujanen, and Villi Citation2019). Wilkins (Citation1997, 78) also underlines how as an educator he teaches that passion is the most important ingredient in journalism. Journalists must “love the story” and “love being in a newsroom” to sustain a life course “in a difficult, demanding profession.” The emotional turn in journalism studies coincides with the resurfacing of passion in workplace research in which the love of one's work, often as addiction to work and work-devotion, is seen as “an expression of passion for work” (Snir and Harpaz Citation2012, 236).

Journalistic Emotions as Commodity

Journalism can be defined as a cultural commodity for sale in the marketplace. McNair (Citation2006) sees journalists as suppliers of a commodity of value to buyers, whether the product is news or journalism as entertainment. Early on, McManus (Citation1992) analysed news as a market-driven product and commodity. In this article we focus on the marketplace for journalism jobs where specific skills and characteristics of people have become a commodity for sale, turning into emotional labour. Emotional labour is a term coined by Hochschild (Citation1983) to describe how service industry workers, flight attendants in their specific case, were supposed to display emotion in their work. Emotional labour includes not only the suppression of feelings but also forced expression of certain emotions (Hochschild Citation1983; Cantillon and Baker Citation2019): “Put simply, emotional labour is prescribed while emotional work is felt” (Thomson Citation2018, 3).

Theoretically we have been informed by the sociology of emotions (Turner and Stets Citation2005; Bericat Citation2016) and particularly inspired by the emotion-management perspective (Hochschild Citation1979, Citation1983). We consider journalists belonging to a meaning-making service profession that places a premium on the individual's capacity to control emotions at work according to social guidelines. Journalism supports deliberative democracy, providing transparency and guidance, which is a specific form of sense-making (Deuze Citation2008; Lindén, Hujanen, and Lehtisaari Citation2019).

According to Hochschild (Citation1979), standardised perceptions of emotion may come to assume the properties of a commodity through which the task is to create and sustain meanings appropriate to the employer. Emotions and their management are a resource to the company, but it is a resource to be used to make money so there is a clash between professional and managerial logics (Lischka Citation2020). From the management side, emotions as a commercial engagement concept were originally embraced by the Gallup Organization, which developed a set of survey questions that connected employee engagement to productivity, profitability, employee retention, and customer service (Buckingham and Coffman Citation1999).

Passion in work can be defined in myriad ways, but the core of all definitions contains some sense of personal fulfilment and mission connected to job involvement (Zigarmi et al. Citation2009). In this paper, we define passion as the pleasure of an interest or activity, or more precisely, emotional engagement in journalistic work that encompasses “enthusiasm, enjoyment, interest, fun, and satisfaction” (Skinner, Pitzer, and Brule Citation2014, 336).

The claim to an emotional turn in journalism has inspired us to study passion from the managerial perspective. Job announcements from the US web site Journalismjobs.com were our data. The research questions are as follows:

RQ1 How has the use of “passion” in Journalismjobs.com advertisements changed between 2002 and 2017?

RQ2 What kind of skills and qualities does “passion” refer to in the job advertisements?

Data and Method

The data for this article consists of a text corpus of job announcements for journalists. The data were originally collected for another research project and the theme “passion” unexpectedly emerged during close readings of job announcement texts. This initial finding was both interesting and exciting as emotions are not usually linked in research into journalistic ideals. We saw “passion” as an outlier in normative theory—the ideal of journalism or what journalists should be—and decided to explore its use.

We find the content of job announcements to be a reflection of management's strategies to transform labour capacities into the kind of labour skills and capabilities required in the processes of news production (Morini, Carls, and Armano Citation2014). Managers decide what journalism should be as they hire, fire and train journalists as well as define work tasks (Young and Carson Citation2018).

There is a rich literature on the demand for journalistic skills and capabilities mainly based on interviews and surveys (see Örnebring and Mellado Citation2018 for an overview), which shows that basic journalistic skills are in high demand (Pierce and Miller Citation2007). However, few researchers have studied the significance of recruitment or turned to advertisements as empirical evidence, so this is a neglected source of data although these texts offer rich material with many dimensions (Kramer Citation2017).

Journalismjobs.com have previously been used as a data source by Carpenter (Citation2009) who tried to determine what skills journalism schools should teach, and Massey (Citation2010) who studied the demand for multiplatform journalists. Others have used job announcements on Indeed.com to find out how journalistic expertise is defined (Guo and Volz Citation2019), or evaluated journalistic skills from job postings on company websites (Wenger and Owens Citation2013; Wenger, Owens, and Cain Citation2018).

We have no access to information about who wrote the job announcements at Journalismjobs.com, but we understand that they reflect the preferences of media managers and HR experts who are also designated contact persons in these advertisements. Thus, we consider that formulations in the texts reflect a managerial perspective.

The data were analysed using both quantitative and qualitative methods. We acquired new job advertisements by downloading them from Journalismjobs.com, which was founded in August 1998 by Dan Rohn, a former journalist. As claimed, this is also the largest and most-visited resource for journalism jobs in the United States (US) and receives between 2.5 and 3 million pageviews a month.

We asked the owner of the website for a data dump of historical data, but this request was denied, and the owner recommended web scraping. For the data extraction we used a Python-based web scraper, which downloaded new announcements every week. The script was based on Python requests and BeautifulSoup libraries. The data are stored as a Python dictionary in a.Json file for further processing. The data contains the unique ID for each advertisement, the headline, and the basic information: date, location, industry, salary and the description or the actual text.

We applied the web scraper to the Internet archive/Wayback Machine web site. Through that procedure we could download 45,562 job advertisements that had been posted to Journalismjobs.com between 2002 and early 2018. Our scraper did not come up with any announcements before 2002 and only a few hundred during the first two years, 2002–2003. Duplicate job ads were removed and the remaining 40,621 job ads were included in the final dataset. We also encountered a problem with missing data from 2016, which is probably due to a change in the Journalismjobs.com site structure, which took place at that time. Web archive bots could no longer access the new adverts and therefore we could not save them in the database.

To reduce the complexity of the empirical material we performed a keyword in context analysis in Quanteda, an R package for managing and analysing text. This produced a report with a concordance that provided five words before and after the keyword “passion.” In this way, we acquired the context with which to interpret keyword frequencies (Ryan and Bernard Citation2003). We assessed the frequency of themes rather than words, which helped to incorporate context into the analysis, which is a helpful and simple analytical technique (Namey et al. Citation2008). Simple keyword searches or word counts within a data set can allow a quick comparison of the words used by different subpopulations within an analysis but through keyword in context the result is a multidimensional data set. The first time we excluded stop words (the most common, short function words, such as the, is, at, which, on), but realised that they are important for understanding context so we performed a new analysis including them.

For the qualitative, thematic analysis we decided to use data from two periods, 2002–2003 at the beginning of the study period and 2017 at its end, to observe the changes during this period. We included two years instead of one at the beginning because of the limited volume of samples and 2017 since it was our last year with full data. We used the data we had extracted through keywords in context (“passion”) from the whole data set of all job announcements. We performed the thematic analysis according to the four task methods proposed by Ryan and Bernard (Citation2003, 85): (1) discovering themes and subthemes, (2) winnowing themes to a manageable few (i.e., deciding which themes are important in any project), (3) building hierarchies of themes or codebooks, and (4) linking themes into theoretical models. Through detailed readings of raw data, researchers can derive concepts, themes, or a model through interpretations made from the raw data (Thomas Citation2006). To analyse the keywords in context data, we built an initial coding scheme inspired by previous research (Guo and Volz Citation2019; Wenger, Owens, and Cain Citation2018) to categorise the specific contexts in which passion was mentioned. We performed a pilot study on a smaller set of 20 texts to find and define categories. After this, two researchers and a research assistant tested the initial coding scheme on a larger set of 50 advertisements for intercoder reliability (86%) and made a few adjustments before two of the researchers started the final coding process of the keyword in context data set. For a few announcements that were hard to categorise, we used the full text for help. As a result, the selected job advertisements were classified into six main categories: 1. Personal character (behaviour or temperament), 2. Orientation towards journalism (ideals, profession, media, communication), 3. Personal interest or beat (sports, hobby and lifestyle, society, technology), 4. Competence and skills (reporting and storytelling, editing and design, video, photography and audio, leadership, digital), 5. Audience engagement (local news, community journalism, audience) and 6. Other.

Our research builds on the assumption that US media companies use Journalismjobs.com as the preferred site for finding new employees. However, Massey (Citation2010) also points out that Journalismjobs.com is not a complete source. Many news-media corporations maintain their own online databases of job openings. Employers also use other, more informal channels for recruiting new journalists, for example, industry conferences or member lists of organisations such as IRE—Investigative Reporters & Editors.

There is also some discrepancy with results from other scholarly papers based on analyses of job advertisements for journalists. For instance, Guo and Volz (Citation2019) looked at Indeed.com, a US-based job search engine for six months in 2017 and found 669 relevant announcements for “journalist,” “reporter,” “correspondent,” “writer,” “editor,” “producer” and “photographer.” That is, about 30% of what was available on Journalismjobs.com. What is striking in comparison was that 85% of job announcements on Indeed.com mentioned multimedia skills, while multimedia was mentioned only 14% of times in our dataset during the comparable period. This indicates the risks of comparing results based on data acquired from different sources.

Findings

Journalismjobs.com Data Set: A Quantitative Approach

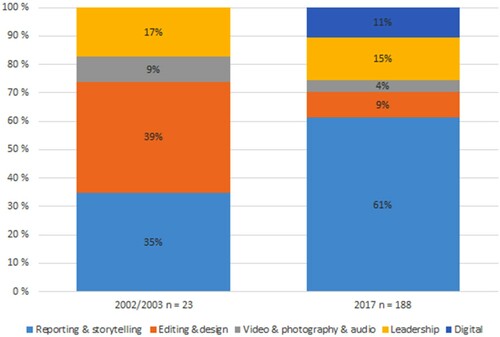

From quantitative analysis of the job advertisements on Journalismjobs.com in which passion is mentioned, we found the following development. Between 2002 and 2017, the number of relevant texts overall increased from fewer than 700 per year to over 4,500 (see ), although the total number of advertisements has fluctuated quite significantly and the impact of the financial crisis in 2007–2009 can be seen in the reduced number of announcements.

Figure 1. Number and share of job ads with the word “passion” on Journalismjobs.com 2002–2017. * Data for 2016 were not available due to configuration changes that broke the web scraper.

During the analysis period, the total number of texts including “passion” was 4,097. This accounts for one-tenth (10.1%) of all job advertisements published during the review period. The proportion of texts with “passion” in 2002 was only four per cent. Thereafter, it grew relatively steadily until 2013 when it peaked at nearly sixteen per cent (15.9%).

could possibly be presented as a hype curve of “passion” in management discourse. This development is temporally connected both with the rise of entrepreneurial journalism after 2008 (Cohen Citation2015) and with the emergence of digital and social media in newsrooms (Belair-Gagnon Citation2015).

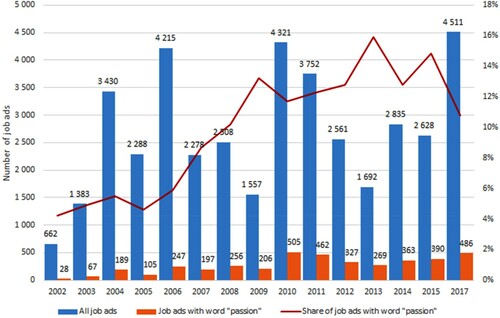

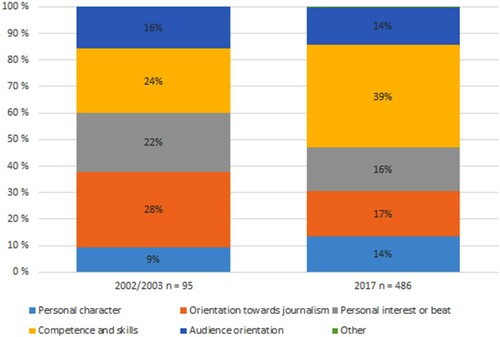

As described in the Data and method section, all job advertisements containing the word “passion” published between 2002 and 2017 were classified into six main categories: Personal character, Orientation towards journalism, Personal interest or beat, Competence and skills, Audience engagement, and Other. In 2002/2003, the number of cases containing the word “passion” was 95, and 486 in 2017. In 2002/2003, more than a quarter (28%) of the texts we analysed were classified in the main category Orientation towards journalism. Another quarter of texts (24%) belonged to the Competence and skills category, and approximately one-fifth (22%) were classified in the Personal interest or beat category. When looking at the distribution among the main categories over time, we can observe significant differences. In 2017, well below one-fifth (17%) still fell into the Orientation towards journalism category. By contrast, the proportion in the Competence and skills category had increased significantly to almost two-fifths (39%). (See .)

Figure 2. Job advertisements with word “passion” by the main category in 2002/2003 and 2017, n = 95 and 486.

The job advertisements containing the word “passion” in each main category were further divided into subcategories. The results of this analysis are presented in .

Table 1. Distribution of job advertisements containing the word “passion” by the main and subcategory in 2002/2003 and 2017, n = 95 and 486.

One intriguing result of the main category level analysis of the quantitative data was the significant changes in the proportion in the main category Competence and skills (). It increased from approximately a quarter in 2002/2003 to close to two-fifths in 2017. In addition, there were significant changes within the category itself. In 2002/2003, well above one-third (39%) in the main category Competence and Skills fell into the Editing and design sub-category. In 2017, by contrast, the proportion in that subcategory had collapsed to less than one-tenth (9.0%). Concurrently the proportion in the Reporting and storytelling subcategory increased considerably from one third (35%) to approximately three-fifths (61%). Digital transition of the media industries is also reflected in how the proportion belonging to the Digital subcategory increased from zero to about one-tenth (11%).

Journalismjobs.com Data Set: A Qualitative Approach

The function of job announcements is for managers to hire journalists with a certain skill set, mindset and personality to perform specific work tasks; it is a market for buyers and sellers of journalistic expertise. The rise of advertisements that emphasise the need for passion indicates a development in the job market for journalists in which emotions are increasingly commodificated: there is a premium for journalists who are passionate in the job and they sell a personality that is connected to their professional role performance (Mellado and Van Dalen Citation2014). Journalists are expected to manage their emotions to produce a strong involvement in what they do. We have previously noted that journalists belong to a profession that creates and sustains appropriate meanings, more precisely reporting as sense-making that is an important component in the media business model (Lindén, Hujanen, and Lehtisaari Citation2019). Passion can be conceived as a standardised perception of feeling that has become a commodity in emotional labour (Hochschild Citation1979).

To understand these above-discussed quantitative changes in the job adverts and the various categories better, we explored in more detail the categories in which “passion” emerges and analysed the job announcements from a qualitative perspective. Below, we look more closely at “passion” as a keyword in context, in some cases including more background for illustrating our point. For this, we focused on the years 2002/2003 and 2017.

Personal Character (Behaviour, Temperament, Emotion)

As mentioned, personal character is not a prominent feature in the data, even though its proportion rose slightly from the first analysed period (2002/2003) to the second (2017). Within this category, there is a trend from passion as temperament (passive) towards preferred behaviour (active). In other words, there seems to be a shift in market value from who journalists are to what they do. That means going from a normative to a performance approach, going from journalism as role conception and rhetoric to practice (Mellado and Van Dalen Citation2014).

Advertisements tend to carry stereotypical expressions such as “passion and imagination,” “passion and curiosity is key,” “passion, vision and a knack for … ,” “passion, skills and collaborative spirit.” The need for a certain personality is sometimes deliberately exaggerated. In 2002, the preferred personality was described as: “You love your job, and your colleagues and readers know it. In fact, they can't help getting caught up in your enthusiasm.” Samples from 2017 include the following text, which points to passion as an active, goal-directed trait and a source of motivational energy:

If you’re someone who loves to get people excited about grabbing their piece of the pie in this complex world, who's fanatical for assisting others to get the most out their time and efforts, but can maintain a sense of humor no matter what level of chaos is going on around you, talk to us.

Orientation Towards Journalism (Ideals and Profession, Certain Media, Communication)

This category shrank between 2002/2003 and 2017 by almost 12 percentage points, which might also be explained with the change towards less rigid conceptions of the ideals of the profession: who journalists are and how they think. Adverts in 2002/2003 include expressions such as these: “[The journalist] must be passionate about being the first to break news stories and about posting well-written, crisp, concise, clear prose” and show a “ … demonstrated passion for journalism” and be “passionate about journalism.” In 2017, there is not much difference, applicants should still be passionate about “journalism” and “news,” “breaking news,” “news and online journalism” and “watchdog journalism.” Passion was also required for the “mission and vision” of the employer and its output: “The candidate must care passionately about excellence in all aspects of the programme and be able to inspire contributors to deliver excellence.” These requirements also point to a performative role which sees journalism as an act or a process defined by the employer, rather than a normative one, connected to the ideals of journalism.

Personal Interests and Beats (Sport, Hobby & Lifestyle, Society, Technology)

The demand for journalists who are passionate about a certain topic and beat decreased overall between 2002/2003 and 2017, but it is especially interesting to note that passion for sport has lost its dominance as have passion for hobby and lifestyle, while passion for society has risen. What we see is a shift towards passion for a wide area covering politics and economics but also other topics such as education. Here are two examples from 2002/2003: “Smart, hungry, entrepreneurial reporters needed. Must have passion for business and business journalism” and “passion for progressive politics.” In 2017, “a passion for social and economic policy” was for instance required, as well as “a passion for government.” In 2017 there was less demand for reporters feeling passionate about a hobby or lifestyle, even though managers were still looking for reporters who wanted to “combine your passion for model railroading and editing,” and also “for smart, passionate and hungry hunting writers.” This shift, we argue, points to the development of such journalism that is focused on large societal issues rather than interests of specialist segments of the audience.

Competence and Skills (Reporting & Storytelling, Editing & Design, Video & Photography & Audio, Leadership, Digital)

As described earlier, the demand for passion about certain competencies and skills was the category which had grown most between 2002/2003 and 2017, which shows the trend towards doing journalism (performance) instead of being a journalist (normative). In 2002/2003, media managers were looking for journalists with a passion for “editing, design,” copy editors with a “passion for accuracy,” or “a passionate beat reporter with exceptional writing.” In 2017, the demand for passion reflected the increasing use of new technology and included “tech skills,” “social platforms,” “social media,” “quality digital content,” “digital emerging media,” and “online media.” This demonstrates how the expanded use of passion is linked to both the digitalisation of the media sector and entrepreneurial journalism. However, regarding older media technology a need was also expressed for such people who are passionate about “all things print”—this is understandable as printed newspapers for many US media companies still are the main source of revenue.

Interestingly, in the Competence and skills category, the proportion of job adverts demanding passion about basic skills rose from 35% in 2002/2003–61% in 2017. This indicates that media managers in the second period were increasingly looking for journalists passionate about writing, editing, reporting and storytelling. This is also reflected in previous research in which media managers were mainly asking for basic journalism skills such as basic writing and shooting good pictures, while producing multimedia content for different platforms was somewhat less important when they recruit new journalists (Pierce and Miller Citation2007). Thus, in line with Young and Carson (Citation2018), media managers seem to express quite conservative views about journalism as a practice.

Audience Engagement (Local News, Community Journalism, Audience)

As there is so much industry talk about audience engagement, we would expect a strong correlation between passion and the range of connections to community news and journalism, local news or even mentions of the existence of an audience. As illustrated in the quantitative part of the study, it is difficult to detect such a trend. Between 2002 and 2017 the proportion declined slightly and different forms of mentioning a community were largely absent, as well as references to an audience. However, we found some examples of this in 2002, including this dramatic request for help: “We need a passionate, committed individual to throw heart and soul into our community and blood and sweat into the newspaper.” Another newspaper claimed to “dominate our share of the market with solid community-focused journalism, surprising enterprise and a collective passion that is unmatched in the industry.”

The closest we came to a definition of audience engagement was a phrase in one advertisement that searched for someone who could “coach and develop a newsroom to deliver balanced, fair, relevant and engaging coverage of the community we serve.” A predefined and shared understanding of what constitutes “community news,” “community journalism” or “local news” can be expected to exist, but it is rendered invisible to the outsider.

When “community” is mentioned it often comes down to the quality of life in a certain geographical area, not any specific way of reporting about the people living there. Many announcements list the positive attributes of the location of the community, such as: “Background should include a passion for issues affecting the West's landscapes and communities. Perks include: small town living; the Rocky Mountains in your backyard; red rock desert in your front yard; a five-minute commute—on your bike.” Landscape is a selling point also in another text: “Have a passion for community journalism? The Kent Reporter, a twice-monthly newspaper covering the rapidly growing city of Kent in beautiful Western Washington.”

In another announcement, candidates are offered a chance “to work in a community that is rich in history and natural beauty. Yosemite and the Sierra Nevada provide limitless outdoor opportunities.” In 2017 candidates needed to have “passion for exploring Kansas City,” “for Montana's outdoor resources” and for “the Rocky Mountain lifestyle.” The pride of small communities can take fascinating forms, and this example has a very special offering: “We are an a.m. daily that publishes Tuesdays through Sundays in a city that's world famous for the ‘Flying Saucer’ report of 1947.”

In 2017, we can see some explicit demands for audience engagement such as “passion for readership engagement,” “passion for finding powerful stories happening” or “passion for building an audience” but this is still presented as jargon and empty rhetoric. This is a finding that resonates with other research (Schmidt, Nelson, and Lawrence Citation2020). Based on the job advertisements, it seems that the idea of a close relationship between engaged journalists and their audience is mostly a theoretical construct (Nelson Citation2018).

Metrics Mindsets

Related to audience engagement we specifically looked for empirical support of technical analysis of user data spreading in newsrooms (Batsell Citation2015). In relation to the word “passion,” we could find no examples asking for journalists who were passionate about audience metrics. However, metrics of some kind were mentioned 137 times in the 2017 dataset consisting of more than 4,500 announcements. Metrics were related to measurement systems of economic success and organisational performance, as well as audience engagement and tracking activities on social media. The texts were written in dry and formal prose and usually described the need for technical skills, which obviously indicates that a “technician” need not be passionate. In 2002/2003, the word metrics occurred six times, and only two advertisements were seeking journalists capable of measuring audience engagement. One announcement was from a public radio station, which was looking for a person who “develops, analyses and reports web metrics for NPR.org.”

A Special Case: Sinclair Broadcast

Our inductive approach revealed some interesting features related to the Sinclair Broadcast Group, which claims to be the leading local news provider in the US. The company owns, operates and/or provides services to 191 television stations with 609 channels in local 89 markets (Sinclair Broadcast Group Citation2020). Sinclair has a politically conservative orientation and strongly expresses this view (Napoli and Dwyer Citation2018). The media company stands out as a special case where their advertisements often refer to “passion,” in a standardised form.

The Sinclair Broadcast Group had long been focused on reporting local news but had recently shifted its focus to the national level. This shift has raised concerns (Martin and McCrain Citation2018): even though media in the US are free to portray their own views on topics, Sinclair Broadcast has diverted from journalistic standards and rules. Sinclair is a clear conservative pro-Trump media company that wants to create uniformity among its viewers.

Sinclair manages its local newscasts centrally, which means they foster a unified ideological orientation among their newscasts. This can be seen as contradicting ethics in journalism based on presenting diverse viewpoints, something state-level regulations in the US also try to support (Napoli and Dwyer Citation2018). One scandal that arose during 2018 was when Sinclair provided the same script in support of Donald Trump to all news anchors at their local TV stations (Martin and McCrain Citation2018).

The quantitative analysis of job advertisements from 2017 revealed that there had been 778 of them from Sinclair, of which 14% mentioned “passion.” When it comes to passion there was an overrepresentation in the material, as Sinclair's proportion of all announcements was 17% but of texts mentioning passion, Sinclair represented 23% of the total. This fact caught our curiosity and we decided to profile this controversial company.

The texts that contained the word “passion” often used the same sentence: “A passion for storytelling is absolutely essential in this position” (86 times or 77%). There were several variations such as: “The ideal candidate will possess excellent communication skills, an enthusiastic and passionate personality, have a tenacious yet empathetic attitude, and a drive to succeed!”

In the job advertisements by Sinclair, community is mentioned 89 times in contexts such as “Help increase the station's viewing audience by serving the interests of the community” or “Create a mutually beneficial relationship with clients in the community.” Community seems to equal an audience relationship that is both superficial and transactional, the community emerges as part of the business model and as a source of story ideas.

The personal traits of job seekers were also underlined in the Sinclair job adverts: personality was mentioned in them 93 times. This also comes in uniform ways, as in 2017, Sinclair was looking for “an enthusiastic and passionate personality, have a tenacious yet empathetic attitude” or people that “have an enthusiastic and outgoing personality, along with a drive to succeed.”

It seems that the Sinclair job announcements have been templated centrally and distributed to television stations throughout the country, which points to the lack of diversity, not just in reporting, but also in the format in which these texts are written and through which people are recruited. As a point of interest, 612 out of 728 texts (84%) from Sinclair end in this way: “Equal Opportunity Employer and Drug Free Workplace!”

Conclusions and Discussion

Expressions of emotion are playing an increasingly important part in the business model of the news media as people's time and emotions have become a commodity in the attention economy (Lischka Citation2020). While “the emotional turn” in journalism has been traced to the increasing influence of social media and the changing affordances of digital journalism (Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2016, Citation2020), we also see the rise of passion in journalism as a process simultaneous with the emergence of the Silicon Valley culture of passion and entrepreneurialism (Maas and Ester Citation2016) and the platformisation of cultural industries such as news media (Bell and Owen Citation2017).

In this article, we have analysed this development from a managerial perspective by tracing the rise of a specific emotion, passion, on the marketplace for journalistic jobs. These advertisements indicate that passion is organisationally incorporated in the editorial processes of the media. In the texts, passion is less seen as a natural personal trait of journalists, but rather something that can be applied in different contexts as a strategic resource. The results point to a commodification of feelings and exploitation of emotional labour in journalism. We especially build our argument based on the case with Sinclair Broadcast Group and their extensive but templated use of the word “passion.”

Our data give us a unique view of the managerial perspective of passion in journalism. We note that passion seems to have become part of recruitment standard language as a marketable skill. Based on our analysis, we agree with Guo and Volz (Citation2019) in that the writing quality of journalists’ job descriptions is uneven, to say the least. Kramer (Citation2017) notes that listings for journalism jobs are often “layered with jargon and wording that would likely turn a lot of good candidates away before they even applied.” To us, it seems that the word “passion” belongs in such a category of routinised and non-reflective statements that is framed within the idea of entrepreneurial journalism as an engine of change and renewal (Ruotsalainen and Villi Citation2018). Here is one text sample expressing what we think must be the irony of this approach: “Our ideal candidate will be able to jump in with both feet and hit the ground running with little to no hand-holding, as well as produce and identify quality writing—unlike the mixed metaphors earlier in this sentence.”

We consider that the higher frequency of the word “passion” in job advertisements thus needs to be critically evaluated and tested empirically with other methods, for instance, interviews with recruiters. We do not think that the routinised use of “passion” necessarily indicates an actual emotional turn in journalism but rather a transformation of management language that might reflect the mimicking of Silicon Valley jargon, “Valley speak” (Kopp and Ganz Citation2016). We, for instance, note that an empirical study of contemporary British journalism finds that it is a professional culture “relatively unaffected by the turn to affect” (Richards and Rees Citation2011, 854).

Despite finding so many instances where the advertisements stress emotional involvement, we found little guidance on what passion or being passionate means and how emotions can be operationalised in journalistic work. In this aspect, we agree with Zigarmi et al. (Citation2009, 301) that there is “very little room for the use of vague or contradictory concepts that give no conceptual understanding or practical application.” If journalists are supposed to act as if they were passionate there is a risk that their real feelings are hidden, and from a managerial perspective, the separation of feeling and display is hard to keep up over long periods (Hayes and Kleiner Citation2001).

The rhetorical demand for passion is possibly aspirational and seems to be driven by factors that are not grounded in a clear conception of the business model for journalism. Very little of the rhetoric attends to the practical questions of actually getting things done in the newsroom, and “passion” is rather treated as an abstract panacea for organisational revitalisation where managers are desperately seeking newness (for a discussion on management hype, see Eccles, Nohria, and Berkley Citation2003).

The jargon in job adverts might reflect larger phenomena in media management. Frederic Filloux, a former media executive and entrepreneur has compared HR practices in the media industry with Netflix and notes that media companies have not understood the value of hiring and retaining the best possible experts: “I’m absolutely certain that the current state of the media industry has something to do with these management deficiencies” (Filloux Citation2020). We also note that traditional media companies that have made a successful transformation to a digital business model, such as New York Times in the US and Dagens Nyheter in Sweden, are hiring the most admired talents in journalism, people with specialist knowledge that cannot be regarded as a commodity (Smith Citation2020).

Management in news organisations expects that employees in the newsroom, from reporters to copy editors, designers, photographers and news editors should be passionate about what they do, but it remains unclear what they actually mean by passion. Therefore, inspired by Morini, Carls, and Armano (Citation2014) we consider it useful to study the experiences of journalists and the extent to which their expectations, desires and needs are in fact considered in employment conditions and how this affects intrinsic work motivation. Our initial suspicion was that passion is a code word used in the context of precarious work, since this has been a focus in studies of other creative industries such as fashion (Arvidsson, Malossi, and Naro Citation2010). As Morini, Carls, and Armano (Citation2014) have found out, media workers’ experiences of passion and precarisation lay closely together, as the organisation of work is increasingly dominated by market imperatives. Bakker (Citation2012) also discusses “low pay and no pay” jobs in the context of new forms of digital journalistic work.

While journalists are driven by their passion and love for their work, they also face precariousness that is a feature of all creative industries, arising from intermittent employment, long hours, low pay, (Hesmondhalgh and Baker Citation2011). In the current media industry where newsrooms have been downsized, “passion” seems to act in the gap between unceasing demands from management and the finite personal resources of journalists.

However, we could not analyse this topic in our study as very few texts mention salary. Still, drawing from many explicit descriptions in our data how journalists should be prepared to work long hours, including nights and weekends and under stress, indicates that there are signs of precarisation in the demand for passion that could be further analysed.

Finally, we believe that emotions in the newsroom is too important a topic to be discussed only in terms of precarious forms of work or the commodification of passion. The digitalisation of media work and automation of routine tasks—algorithms in the newsroom—means that journalists need to to think harder at defining their core human capabilities, such as developing emotional and social intelligence, curiosity, authenticity, humility, empathy and the ability to become better listeners, collaborators and learners (Lindén Citation2017, 71). Glück (Citation2016) especially underlines the need for empathy as a form of “emotional capital” in journalism. With the development of affective computing, systems and devices that can recognise, interpret, process, and simulate human effects, the challenge becomes almost urgent: there are already people designing virtual journalists with human emotions (Bowden et al. Citation2017). These are issues that are very much in need of a strong managerial perspective that does not fall into the hype trap with the routine use of empty expressions such as “passion.”

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Ian R. Dobson for proofreading as well as Laszlo Vincze and Leo Leppänen for help with the data analysis. The results of this article reflect only the authors’ view and the EU Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arvidsson, A., G. Malossi, and S. Naro. 2010. “Passionate Work? Labour Conditions in the Milan Fashion Industry.” Journal for Cultural Research 14 (3): 295–309.

- Bakker, P. 2012. “Aggregation, Content Farms and Huffinization: The Rise of Low-Pay and No-Pay Journalism.” Journalism Practice 6 (5-6): 627–637.

- Batsell, J. 2015. Engaged Journalism: Connecting with Digitally Empowered News Audiences. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Belair-Gagnon, V. 2015. Social Media at BBC News: The Re-making of Crisis Reporting. New York: Routledge.

- Bell, E., and T. Owen. 2017. The Platform Press: How Silicon Valley Reengineered Journalism. New York: Tow Center for Digital Journalism. https://www.cjr.org/tow_center_reports/platform-press-how-silicon-valley-reengineered-journalism.php.

- Bericat, E. 2016. “The Sociology of Emotions: Four Decades of Progress.” Current Sociology 64 (3): 491–513.

- Bowden, K. K., T. Nilsson, C. P. Spencer, K. Cengiz, A. Ghitulescu, and J. B. van Waterschoot. 2017. “I Probe, Therefore I Am: Designing a Virtual Journalist with Human Emotions.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1705.06694.

- Briggs, M. 2012. Entrepreneurial Journalism: How to Build What’s Next for News. Thousand Oaks, CA: CQ Press.

- Broersma, M. 2019. “Audience Engagement.” In The International Encyclopedia of Journalism Studies, edited by T. P. Vos, F. Hanusch, and D. Dimitrakopoulou. Wiley. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118841570.

- Buckingham, M., and C. Coffman. 1999. First, Break All the Rules: What the World’s Greatest Managers Do Differently. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Cantillon, Z., and S. Baker. 2019. “Affective Qualities of Creative Labour.” In Making Media: Production, Practices, and Professions, edited by M. Deuze, and M. Prenger, 287–296. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Cardon, M. S., J. Wincent, J. Singh, and M. Drnovsek. 2009. “The Nature and Experience of Entrepreneurial Passion.” Academy of Management Review 34 (3): 511–532.

- Carpenter, S. 2009. “An Application of the Theory of Expertise: Teaching Broad and Skill Knowledge Areas to Prepare Journalists for Change.” Journalism & Mass Communication Educator 64 (3): 287–304.

- Cohen, N. S. 2015. “Entrepreneurial Journalism and the Precarious State of Media Work.” South Atlantic Quarterly 114 (3): 513–533.

- Couldry, N., and J. Littler. 2011. “Work, Power and Performance: Analysing the ‘Reality’ Game of The Apprentice.” Cultural Sociology 5 (2): 263–279.

- Davenport, T. H., and J. Beck. 2001. The Attention Economy: Understanding the New Currency of Business. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Deuze, M. 2008. “The Changing Context of News Work: Liquid Journalism for a Monitorial Citizenry.” International Journal of Communication 2 (18): 848–865.

- Deuze, M., and M. Prenger, eds. 2019. Making Media; Production, Practices, and Professions. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Eccles, R. G., N. Nohria, and J. D. Berkley. 2003. Beyond the Hype: Rediscovering the Essence of Management. Washington, DC: Beard Books.

- Filloux, F. 2020. “Managing a News Operation the Netflix Way.” October 2. https://mondaynote.com/managing-a-news-operation-the-netflix-way-235b7ec96c40.

- Glück, A. 2016. “What Makes a Good Journalist? Empathy as a Central Resource in Journalistic Work Practice.” Journalism Studies 17 (7): 893–903.

- Guo, L., and Y. Volz. 2019. “(Re)defining Journalistic Expertise in the Digital Transformation: A Content Analysis of Job Announcements.” Journalism Practice 13 (10): 1294–1231.

- Hamel, G. 1999. “Bringing Silicon Valley Inside.” Harvard Business Review 77 (5): 71.

- Hansen, E., and E. Goligoski. 2018. “Guide to Audience Revenue and Engagement.” Accessed January 6, 2021. https://www.cjr.org/tow_center_reports/guide-to-audience-revenue-and-engagement.php/.

- Hayes, S., and B. H. Kleiner. 2001. “The Managed Heart: The Commercialisation of Human Feeling – and Its Dangers.” Management Research News 24 (3/4): 81–85.

- Hesmondhalgh, D., and S. Baker. 2011. Creative Labour: Media Work in Three Cultural Industries. London: Routledge.

- Hochschild, A. R. 1979. “Emotion Work, Feeling Rules, and Social Structure.” American Journal of Sociology 85 (3): 551–575.

- Hochschild, A. 1983. The Managed Heart: The Commercialisation of Human Feeling. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Kopp, R., and S. Ganz. 2016. Valley Speak: Deciphering the Jargon of Silicon Valley. Redwood City: Genetius Publishing.

- Kramer, M. 2017. 5 Ways to Make Your Journalism Job Descriptions Better. Poynter. Accessed May 21, 2020. https://www.poynter.org/news/5-ways-make-your-journalism-job-descriptions-better.

- Kramer, M., and B. O’Donovan. 2019. How to Build a Metrics-Savvy Newsroom. American Press Institute. Accessed May 20, 2020. https://www.americanpressinstitute.org/publications/how-to-build-a-metrics-savvy-newsroom/single-page/.

- Küng, L. 2015. Innovators in Digital News. London, New York: I.B. Tauris.

- Lehtisaari, K., M. Villi, M. Grönlund, C. Lindén, B. Mierzejewska, R. Picard, and A. Roepnack. 2018. “Comparing Innovation and Social Media Strategies in Scandinavian and US Newspapers.” Digital Journalism 6 (8): 1029–1040.

- Lindén, C.-G. 2017. “Algorithms for Journalism: The Future of News Work.” The Journal of Media Innovations 4 (1): 60–76.

- Lindén, C.-G. 2020. Silicon Valley och makten över medierna. Gothenburg: Nordicom.

- Lindén, C.-G., J. Hujanen, and K. Lehtisaari. 2019. “Hyperlocal Media in the Nordic Region.” Nordicom Review 40 (s2): 3–13.

- Lischka, J. A. 2020. “Fluid Institutional Logics in Digital Journalism.” Journal of Media Business Studies 17 (2): 113–131.

- Maas, A., and P. Ester. 2016. Silicon Valley, Planet Startup: Disruptive Innovation, Passionate Entrepreneurship and Hightech Startups. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Martin, G. J., and J. McCrain. 2018. Yes, Sinclair Broadcast Group Does Cut Local News, Increase National News and Tilt Its Stations Rightward. Accessed May 22, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2018/04/10/yes-sinclair-broadcast-group-does-cut-local-news-increase-national-news-and-tilt-its-stations-rightward/.

- Massey, B. L. 2010. “What Job Advertisements Tell Us about Demand for Multiplatform Reporters at Legacy News Outlets.” Journalism & Mass Communication Educator 65 (2): 142–155.

- McManus, J. H. 1992. “What Kind of Commodity Is News.” Communication Research 19 (6): 787–805.

- McNair, B. 2006. Cultural Chaos: Journalism and Power in a Globalised World. New York: Routledge.

- Mellado, C., and A. Van Dalen. 2014. “Between Rhetoric and Practice: Explaining the Gap between Role Conception and Performance in Journalism.” Journalism Studies 15 (6): 859–878.

- Morini, C., K. Carls, and E. Armano. 2014. “Precarious Passion or Passionate Precariousness? Narratives from Co-research in Journalism and Editing.” Recherches sociologiques et anthropologiques 45 (2): 61–83.

- Namey, E., G. Guest, L. Thairu, and L. Johnson. 2008. “Data Reduction Techniques for Large Qualitative Data Sets.” In Handbook for Team-based Qualitative Research, edited by G. Guest and K. M. MacQueen, 137–161. Lanham: Altamira Press.

- Napoli, P. M., and D. L. Dwyer. 2018. “U.S. Media Policy in a Time of Political Polarization and Technological Evolution.” Publizistik 63: 583–601.

- Nelson, J. L. 2018. “The Elusive Engagement Metric.” Digital Journalism 6 (4): 528–544.

- Orgeret, K. S. 2020. “Discussing Emotions in Digital Journalism.” Digital Journalism 8 (2): 292–297.

- Örnebring, H., and C. Mellado. 2018. “Valued Skills Among Journalists: An Exploratory Comparison of Six European Nations.” Journalism 19 (4): 445–463.

- Pein, C. 2014. Amway Journalism. Accessed December 31, 2020. http://www. thebaffler.com/blog/amway-journalism/.

- Pierce, T., and T. Miller. 2007. “Basic Journalism Skills Remain Important in Hiring.” Newspaper Research Journal 28 (4): 51–61.

- Raviola, E., and B. Hartmann. 2009. “Business Perspectives on Work in News Organizations.” Journal of Media Business Studies 6 (1): 7–36.

- Richards, B., and G. Rees. 2011. “The Management of Emotion in British Journalism.” Media, Culture & Society 33 (6): 851–867.

- Rosen, J. 2011. “If ‘He Said, She Said’ Journalism Is Irretrievably Lame, What’s Better?” Accessed May 22, 2020. http://pressthink.org/2011/09/if-he-said-she-said-journalism-is-irretrievably-lame-whats-better/#aftermatter.

- Ruotsalainen, J., J. Hujanen, and M. Villi. 2019. “A Future of Journalism Beyond the Objectivity–Dialogue Divide? Hybridity in the News of Entrepreneurial Journalists.” Journalism, online first.

- Ruotsalainen, J., and M. Villi. 2018. “Hybrid Engagement: Discourses and Scenarios of Entrepreneurial Journalism.” Media and Communication 6 (4): 79–90.

- Ryan, G. W., and H. R. Bernard. 2003. “Techniques to Identify Themes.” Field Methods 15 (1): 85–109.

- Schmidt, T. R., J. L. Nelson, and R. G. Lawrence. 2020. “Conceptualizing the Active Audience: Rhetoric and Practice in ‘Engaged Journalism’.” Journalism, 1464884920934246.

- Sinclair Broadcast Group. 2020. About. http://sbgi.net/.

- Skinner, E., J. Pitzer, and H. Brule. 2014. “The Role of Emotion in Engagement, Coping, and the Development of Motivational Resilience.” In International Handbook of Emotions in Education, edited by R. Pekrun, and L. Linnenbrink-Garcia, 331–347. New York/London: Routledge.

- Smith, B. 2020. “Why the Success of the New York Times May Be Bad News for Journalism.” Accessed October 10, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/01/business/media/ben-smith-journalism-news-publishers-local.html?smtyp=cur&smid=fb-nytimes.

- Snir, R., and I. Harpaz. 2012. “Beyond Workaholism: Towards a General Model of Heavy Work Investment.” Human Resource Management Review 22 (3): 232–243.

- Tenor, C. 2019. “Logic of an Effectuating Hyperlocal.” Nordicom Review 40 (s2): 129–145.

- Thomas, D. R. 2006. “A General Inductive Approach for Analyzing Qualitative Evaluation Data.” American Journal of Evaluation 27 (2): 237–246.

- Thomson, T. 2018. “Mapping the Emotional Labor and Work of Visual Journalism.” Journalism. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884918799227.

- Turner, J. H., and J. E. Stets. 2005. The Sociology of Emotions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Villi, M., M. Grönlund, C. Lindén, K. Lehtisaari, B. I. Mierzejewska, R. G. Picard, and A. Röpnack. 2020. ““They’re a Little Bit Squeezed in the Middle”: Strategic Challenges for Innovation in US Metropolitan Newspaper Organisations.” Journal of Media Business Studies 17 (1): 33–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/16522354.2019.1630099.

- Vos, T. P., and J. B. Singer. 2016. “Media Discourse about Entrepreneurial Journalism: Implications for Journalistic Capital.” Journalism Practice 10 (2): 143–159.

- Wahl-Jorgensen, K. 2016. “Emotion and Journalism.” In The SAGE Handbook of Digital Journalism, edited by T. Witschge, C. W. Anderson, D. Domingo, and A. Hermida, 128–143. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Wahl-Jorgensen, K. 2020. “An Emotional Turn in Journalism Studies?” Digital Journalism 8 (2): 175–194.

- Waldenström, A., J. Wiik, and U. Andersson. 2019. “Conditional Autonomy: Journalistic Practice in the Tension Field between Professionalism and Managerialism.” Journalism Practice 13 (4): 493–508.

- Wenger, D., and L. C. Owens. 2013. “An Examination of Job Skills Required by Top U.S. Broadcast News Companies and Potential Impact on Journalism Curricula.” Electronic News 7 (1): 22–35.

- Wenger, D. H., L. C. Owens, and J. Cain. 2018. “Help Wanted: Realigning Journalism Education to Meet the Needs of Top U.S. News Companies.” Journalism & Mass Communication Educator 73 (1): 18–36.

- Wilkins, D. M. 1997. “Despite Computers, Journalism Remains a Human Enterprise.” Journalism & Mass Communication Educator 52 (1): 72–78.

- Wu, T. 2016. The Attention Merchants. London: Atlantic Books.

- Young, S., and A. Carson. 2018. “What is a Journalist? The View from Employers as Revealed by Their Job Vacancy Advertisements.” Journalism Studies 19 (3): 452–472.

- Zigarmi, D., K. Nimon, D. Houson, D. Witt, and J. Diehl. 2009. “Beyond Engagement: Toward a Framework and Operational Definition for Employee Work Passion.” Human Resource Development Review 8 (3): 300–326.