ABSTRACT

Satirical news shows constitute an innovative hybrid genre that mixes regular news and fiction. The discursive integration hypothesis posits that the defining characteristic of satirical news shows is that news and fiction elements are integrated such that boundaries between the preexisting genres have blurred. The current study quantitatively tests this hypothesis on both long-running American shows such as The Daily Show and more recent shows such as Last Week Tonight. We collected transcripts of fifteen satirical news shows, eleven regular news shows, and fourteen fiction shows from 2018 (9,824,249 words). Transcripts were automatically tagged for over fifty linguistic features to identify register dimensions, patterns in linguistic features unique to genres, which we used to determine the presence of discursive integration. Findings revealed that two-thirds of satirical news shows were indeed characterized by discursive integration (which we labeled “complete hybrids”), while one-third manifested through the already existing hybrid genre of opinionated news (which we labeled “hybrid-genre echoes”). These two categories of shows demonstrate the importance of genre hybridity for defining satirical news across different shows.

Over the last decades, the social and political significance of satirical news shows (e.g., The Daily Show, Last Week Tonight) has received much attention (Becker and Waisanen Citation2013). For many individuals, satirical news shows are an important source of information about current affairs (Becker and Bode Citation2017). This is in the first place because they contain similar amounts of substantive information to regular news shows (Fox, Koloen, and Sahin Citation2007), but also because they comment on regular news by pointing out inaccuracies and falsehoods in news stories (Painter and Hodges Citation2010). Consequently, an ever-growing body of literature has examined the impact of satirical news shows on political attitudes and behaviors (Becker and Waisanen Citation2013). Previous research has for instance found that satirical news shows can promote general political engagement (Lee and Kwak Citation2014) and can decrease support for targeted political candidates (Baumgartner and Morris Citation2006).

In order to explain satirical-news effects, a question central to much theoretical work is how satirical news combines elements from different genres. Various scholars have argued that satirical news mimics regular news by reporting on news issues and mimics fiction through the use of play and pretense because satirists often act as “real” journalists (e.g., Baym Citation2005; Berkowitz and Schwartz Citation2016; Waisanen Citation2011). As a result, these scholars argue that satirical news relies on discursive repertoires reflecting the combination of these imitations, which grants it the status of a distinct hybrid news genre.

Baym (Citation2005) labeled this blurring of genre boundaries between regular news and fiction discursive integration. He proposed discursive integration to be a defining characteristic of satirical news shows, and argued that it was discursive integration that explained the innovativeness of The Daily Show with Jon Stewart—the most popular satirical news show at the time. Today, the concept of discursive integration is more generally used to describe and explain what could potentially make satirical news shows a one-of-a-kind type of hybrid genre (e.g., Becker and Waisanen Citation2013; Berkowitz and Schwartz Citation2016; Feldman Citation2017). However, despite the popularity of the concept, empirical evidence for it is still limited. A first aim of this paper is therefore to test Baym’s (Citation2005) discursive integration hypothesis through a quantitative analysis of a large corpus of show transcripts.

Moreover, the American media landscape has become more diverse since Baym’s (Citation2005) publication, making it unclear whether the hypothesis holds true for all shows in similar ways. Various alumni of The Daily Show (e.g., John Oliver, Samantha Bee, Hasan Minhaj) for instance started hosting satirical news shows of their own. Their shows stand out from The Daily Show in journalistic approach by providing more in-depth analyses in support of their critiques on news issues and production (Becker and Bode Citation2017; Jennings, Bramlett, and Warner Citation2019; Michaud Wild Citation2019). For this reason, the second aim of this paper is to update the literature by taking into account contemporary shows such as Last Week Tonight with John Oliver, Full Frontal with Samantha Bee, and Patriot Act with Hasan Minhaj. We thus tested the presence of discursive integration in present-day satirical news shows.

Defining Satirical News Shows

As a genre of satire, satirical news can be defined by its communicative aim (Hutcheon Citation2000; Peifer and Lee Citation2019) and target preferences (Hutcheon Citation2000; Kreuz and Roberts Citation1993). That is, satirical news aims to criticize socially and politically important targets (e.g., actors, organizations, institutions) as well as inform the public about the reasons for this critique (Peifer and Lee Citation2019). In order to do so, satirical news shows adopt conventions of both the genres of news and fiction, which is for instance reflected in the notion that show hosts “play” the anchor of a news show.Footnote1

According to Baym (Citation2005), how satirical news shows blend genre conventions of regular news and fiction is another defining characteristic. On the one hand, blends between both types of genres can be observed in surface features such as show décor and the use of videoclips and correspondents. On the other hand, more profound blends exist at the higher level of discourse, that is, in terms of how current affairs are more generally discussed and understood. This “discursive integration” (Baym Citation2005) adds a new level of meaning to news issues and events covered in satirical news shows, because, in satirical news content “the silly is interwoven with the serious, resulting in an innovative and potentially powerful form of public information” (273). The distinctions between regular news and fiction in satirical news shows have thus in creative ways been collapsed.

Discursive Integration in Satirical News Shows

While Baym’s (Citation2005) article about discursive integration is often cited to describe what makes satirical news shows stand out in the news media landscape (e.g., Becker and Waisanen Citation2013; Berkowitz and Schwartz Citation2016; Feldman Citation2017; Hoffman and Young Citation2011; Holbert et al. Citation2007; LaMarre, Landreville, and Beam Citation2009), how exactly it manifests has received little scholarly attention. Valuable previous work has been conducted from a critical-cultural perspective, qualitatively analyzing a number of examples (e.g., Berkowitz and Schwartz Citation2016; Waisanen Citation2011). An important finding of these studies is that satirical news seems to position itself as a hyper-realistic alternative to mainstream journalism. Through discursive integration, the genre is able to delegitimize information that would otherwise be considered “true” or “authentic” (Berkowitz and Schwartz Citation2016; Waisanen Citation2011). This paper bridges research from the critical-cultural and quantitative traditions of journalism research by quantitatively analyzing how such lines between fact and fantasy in satirical news are blurred in a large corpus of episodes from multiple satirical news shows.

This study also answers calls for more research into the identifying characteristics of satire across satirical news shows (Becker and Waisanen, Citation2013; Holbert et al. Citation2011). Satirical news used to be mostly studied as a monolithic concept, which means that different instances of satirical news were addressed as one (Holbert et al. Citation2011). Scholarly attention today focuses on how satirical news may be a considerably more diverse concept instead, for instance having different effects when presented differently (Holbert et al. Citation2011). Many of these studies have examined different types of jokes (e.g., Baumgartner, Morris, and Coleman Citation2018; Becker Citation2012; Holbert et al. Citation2011; Matthes and Rauchfleisch Citation2013; Polk, Young, and Holbert Citation2009). In the current paper, we examine diversity at the higher level of journalistic approaches. We take a bottom-up approach to determine whether levels of discursive integration are similar among a broad range of satirical news shows characterized by different comedy types.

Since Baym published his article in 2005, The Daily Show has become a “launchpad for a new generation of political humor” (Michaud Wild Citation2019, 344). This evolution in the format of contemporary satirical news shows is reflected in a shift to more information-rich programming (Becker and Bode Citation2017; Jennings, Bramlett, and Warner Citation2019; Michaud Wild Citation2019). Shows such as Last Week Tonight are more than before characterized by explanatory and investigative segments that also tend to focus more on issues that have been underreported in the traditional press (Becker and Bode Citation2017; Jennings, Bramlett, and Warner Citation2019; Michaud Wild Citation2019). This suggests that satirical news shows are moving more towards opinion news formats, which raises the question whether discursive integration (Baym Citation2005) is still an overarching characteristic of all satirical news shows in today’s news media landscape.

This study identified the presence of discursive integration in contemporary satirical news shows by studying linguistic register, because previous research suggests that this is a valid and reliable method to distinguish between genres (Biber Citation2014). Genres differ in their communicative functions (Bhatia Citation1997; Swales Citation1990). Linguistic registers are genre-specific patterns of co-occurrences of linguistic features that reflect these functions (Scarcella Citation2003). For instance, the register of news is more abstract than the register of fiction (Biber Citation1995) probably as the result of journalists’ desire to remain “neutral” (e.g., Thomson, White, and Kitley Citation2008). This is reflected in the use of more conjuncts (e.g., moreover, therefore) and more agentless passives (e.g., decision were made) in news than in fiction. By contrast, the register of news contains less narrativity than the register of fiction (Biber Citation1995) because journalists typically have a less immersive style of storytelling than fiction writers do. This is demonstrated by, among others things, the use of fewer third-person pronouns (e.g., she, him, themselves) and fewer public verbs (e.g., suggests, explains, argues). These and other genre-specific patterns in language are considered relatively stable (Biber Citation1995; Scarcella Citation2003).

This means that we can determine the presence of discursive integration in satirical news shows by identifying how satirical news scores on register dimensions that characterize regular news and fiction. We would find support for the discursive integration hypothesis (Baym Citation2005) when the genre of satirical news scores in between regular news and fiction shows in terms of linguistic register. For this reason, we hypothesized:

H1: At the genre level, satirical news shows score in between regular news shows and fiction shows on identified register dimensions.

H2: At the show level, all satirical news shows score in between regular news shows and fiction shows on identified register dimensions.

Method

This study was conducted by means of the multidimensional-analysis method (MDA) developed by Biber (Citation1988). MDA identifies register dimensions by examining patterns of co-occurrences of linguistic features in collections of texts. This method has been the leading computer-automated method to study register variation between genres (Friginal Citation2013; see Biber Citation2014, for an overview of studies that have used this method). MDA has for instance been applied to genres such as scientific papers (Gray Citation2013), online blogs (Grieve et al. Citation2011), and editorials (Huang and Ren Citation2019). With regard to television shows, MDA studies have focused on a broad range of television shows such as soap operas (Al-Surmi Citation2012) and game shows (Sardinha and Pinto Citation2017). To the best of our knowledge, this study is both the first to analyze linguistic register of satirical news shows and to use this analysis of linguistic register as a measure of discursive integration.

Inclusion Criteria

The first step of MDA (Biber Citation1988) is to decide which texts to collect. We made decisions regarding (1) modality, (2) country of origin, and (3) time frame. With regard to (1) modality, spoken and written language typically differ in linguistic dimensions such as clarity and formality (e.g., Redeker Citation1984), which is why spoken and written satirical news may also differ in such dimensions. This study focused on satirical news shows because Baym’s (Citation2005) concept of discursive integration was inspired by The Daily Show. With regard to (2) country of origin, differences in satirical news content have been attributed to differences in political, journalistic, and humor cultures (Matthes and Rauchfleisch Citation2013). We therefore focused on American shows only because the US media landscape allowed us to include multiple shows per genre. Finally, with regard to (3) time frame, styles of news reporting have changed over time (Esser and Umbricht Citation2014). In order to provide contemporary evidence, we only focused on show episodes first broadcast in the calendar year 2018.

We next determined which shows to include per genre. We included as many satirical news shows as possible to capture the diversity of show segments such as monologues and parody sketches. We identified seventeen relevant shows based on whether the networks and/or show hosts have described them as containing segments that criticize news through humor. Some shows were included completely because they were satirical from start to finish (e.g., Last Week Tonight with John Oliver, Full Frontal with Samantha Bee, Patriot Act with Hasan Minhaj). Of most other shows, only certain segments were included, which were satirical monologues (e.g., The Daily Show with Trevor Noah, Real Time with Bill Maher; the “A Closer Look” and “The Check In” segments in Late Night with Seth Meyers) and satirical sketches (e.g., the “Cold Open” and “Weekend Update” segments in Saturday Night Live). Non-satirical segments such as celebrity interviews were excluded from the study. In this paper, we thus use the term satirical news show to refer to news shows that were either completely satirical or that contained satirical news segments.

With regard to the regular news shows, the number of possible shows to include was extensive. In contrast to some satirical news shows, regular news shows are broadcast each evening, resulting in a great amount of available data. We therefore, instead, selected a smaller number of typical shows. Because language use in news discourse can depend on political group membership (Cichocka et al. Citation2016), we separately selected traditional news shows, liberal news shows and conservative news shows. The selected traditional news shows were the evening-news programs of the three largest US television networks: ABC, CBS, and NBC. The liberal news shows were four prime-time programs of liberal network MSNBC. The conservative shows were four prime-time programs of conservative network FOX News. Prime-time programs were shows broadcast on weekdays at 7PM, 8PM, 9PM, and 10PM ET.

Finally, fiction shows were selected based on topical resemblance with the included news shows. This meant that, first, the story world needed to mirror the current day world. Utopian, dystopian, and science-fiction series were therefore excluded from the study. Second, because satirical and regular news often focus on politics, we selected only political fiction shows. Political fiction shows where operationalized as shows in which at least one main character was active in at least one of the three branches of the US government: (a) executive branch (e.g., President, Cabinet, executive departments, FBI, CIA), (b) legislative branch (e.g., House of Representatives, Senate), and (c) judicial branch (e.g., Supreme Court). Third, episodes needed to be broadcast in the calendar year 2018 for the first time. Reruns were excluded. Based on these criteria, we identified fourteen relevant political fiction shows (e.g., Designated Survivor, Homeland, House of Cards, Madam Secretary).

Collection of Transcripts

The second step in MDA (Biber Citation1988) is to collect texts. Transcripts of the satirical news shows and the liberal and conservative news shows were collected by means of the command-line program youtube-dl (available at: http://ytdl-org.github.io/youtube-dl/), which we used to download automatic captions from YouTube. We used YouTube because previous research has found such automatic speech-to-text transcriptions to be accurate (Ziman et al. Citation2018). In some respects, they may even be more reliable than the original US television subtitles because real-time subtitles can contain typos and are subject to strict character and time restrictions (Szarkowska, Cintas, and Gerber-Morón Citationin press). Visual inspection of the downloaded transcripts also indicated a high level of accuracy.

By collecting transcripts from YouTube, we relied on the availability of videos with automatic captioning. At this stage of the study, the satirical news shows Conan with Conan O’Brien and The Greg Gutfeld Show were excluded because captions were unavailable. The transcripts of the traditional news shows were collected using NexisUni (available at: https://www.lexisnexis.com), an online news database. Finally, the transcripts of the political fiction series were collected through Springfield! Springfield! (available at: https://www.springfieldspringfield.co.uk/), an online script database.

We prepared the transcripts for linguistic tagging by removing document information (e.g., names of journalists, date broadcasting) as well as script details such as [door opens] and [laughs]. Transcripts were also merged by broadcast date to be able to generalize findings to the level of entire episodes. The final corpus consisted of 2,485 transcripts and 9,824,249 words. By way of comparison, this corpus was ten times larger than Biber’s corpus of almost one million words used in his seminal 1988 work.

Linguistic-Feature Tagging

Following MDA (Biber Citation1988), the third step of this study was to tag the transcripts for the presence of a predetermined list of linguistic features. We used the Multidimensional Analysis (MAT) tagger (Nini Citation2015) which included all features analyzed by Biber (Citation1988) and which is based on the Stanford tagger for American English. Frequency counts were normalized to a text length of 100 words and standardized.

A consequence of having collected the transcripts of the satirical news shows and the liberal and conservative news shows from YouTube was that these transcripts did not include punctuation because in spoken language punctuation is not made explicit. In order to prevent punctuation from therefore being a potentially confounding variable, tags that were either completely or partially dependent on punctuation were left out of the analysis.Footnote2 Hence, all transcripts were tagged for a total of 57 linguistic features (e.g., verb tenses, types of pronouns, types of modals, types of clauses, conjuncts, adjectives, adverbs).

Factor Analysis

The next step of MDA (Biber Citation1988) consisted of the identification of register dimensions by means of an exploratory factor analysis. The advantage of MDA as a bottom-up register analysis approach is that all identified dimensions reflect the communicative aims of the target genres (Biber Citation2014). The most common techniques of exploratory factor analysis are principal component analysis (PCA) and principal axis factoring (PAF; Morrison Citation2009). Like Biber (Citation1988), we used PAF to identify the register dimensions because PAF does not assume multivariate normality (Morrison Citation2009). With regard to the two types of rotations that can be applied (i.e., orthogonal and oblique), a disadvantage of orthogonal rotations is that factors are not allowed to correlate (Morrison Citation2009). We thus followed factor analysis recommendations by Morrison (Citation2009) and selected the promax rotation as one of the oblique rotation methods. Finally, a scree-test was conducted to determine the optimal number of subtracted factors (Cattell Citation1966). The plot indicated a three-factor solution, presented in Appendix A on the Open Science Framework (OSF): https://osf.io/jruye/.

The register dimensions were computed in line with MDA (Biber Citation1988). The dimension scores of each genre were calculated by summing the standardized frequency counts of features that loaded positively on each dimension. This sum was subtracted by the sum of standardized frequency counts of features with negative loadings on the dimension. Linguistic features with loadings lower than 0.3 were dropped from the analysis given low communality. When one feature loaded on multiple dimensions, we kept the feature with the highest loading, except when the difference was 0.1 or less, making the features insufficiently distinctive of a dimension. In these scarce cases, both features were dropped.Footnote3 Results are shown in Appendix B on the OSF: https://osf.io/jruye/.

The analysis revealed three dimensions. The first dimension, which we called “involved vs. informational discourse”, reflected one of Biber’s (Citation1988) original dimension “involved vs. informational production”. The features that loaded positively indicated a focus on personal involvement and interpersonal interaction, such as first and second person pronouns (e.g., me, myself, you), present tense verbs (e.g., he believes, she thinks), and demonstrative pronouns (e.g., that looks like). The presence of many first- and second-person pronouns, for example, indicates contact between speaker and one or more addressees (Chafe Citation1985). The features that loaded negatively signaled more distant and precise presentation of information, such as time and space adverbials (e.g., today, previously; below, nearby), perfect aspect verbs (e.g., we had discovered), and long words. Time and place adverbials are often used to highlight the physical and temporal context of a text (Crawford Citation2008). Since informational discourse is more distant than involved discourse, the former is also characterized by past-tense verbs and the latter by present-tense verbs.

We labeled the second dimension “evaluative vs. referential discourse”. The features that loaded positively indicated the expression of personal stance (Shelke, Deshpande, and Thakre Citation2012), such as adverbs (e.g., beautifully, carefully), adjectives (e.g., this is useful), and private verbs (e.g., assumes, knows, fears). By contrast, the features that loaded negatively predominantly consisted of nouns (e.g., country, policy, elections), which are generally used to establish specific reference to objects, issues or events (Fonteyn, Heyvaert, and Maekelberghe Citation2015).

Finally, the third dimension, “deliberative discourse”, was only characterized by features that loaded positively, such as relative clauses (e.g., the topic that I like most is), conjuncts (e.g., moreover, therefore), and amplifiers (e.g., absolutely, completely, strongly). Particularly prominent in this dimension were relative clauses, which are strongly associated with the communicative act of deliberation (Tse and Hyland Citation2010) in which people recognize and try to reconcile conflicting views when they communicate about an issue (Wessler Citation2008). The reason for this association is that an important function of relative clauses is to link an identified subject (e.g., person, topic, event) to more information about it (Swan Citation1996). Conjuncts typically serve to show the direction of relationship between statements (Quirk et al. Citation1985). Amplifiers in this context may signal emphasis on expressions of (perceived) truth (Bolinger Citation1972). Together, these linguistic features thus indicate a discussion of perspectives.

Data Analysis

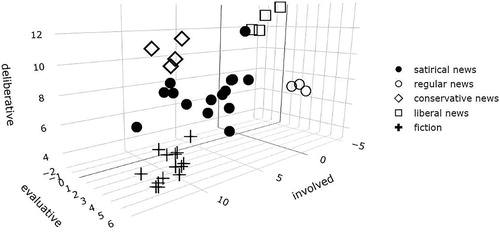

The final step in this study was comparing the dimension means. We used two statistical methods to test our hypotheses: (1) multilevel analysis and (2) cluster analysis. The multilevel analysis served to compare dimension means at the genre level, while the cluster analysis served to do so at the show level. In this way, we determined whether register differences existed between the target genres (H1) and also assessed whether these differences were consistent across shows (H2). Dataset, syntax, and output are made available on our OSF page: https://osf.io/jruye/. The show and genre means are shown in .

Table 1. Mean dimension scores of all shows and genres.

Results

Multilevel Analysis

A multilevel analysis was conducted to examine whether satirical news’ register represents a mix of the regular news and fiction registers (H1). Because shows were nested in genres, we fitted three linear mixed-effects models with a random intercept for show using the lme4 package (version 1.1-21; Bates et al. Citation2015) for R (version: 3.5.2). We fitted one model for each register dimension to compare dimension means between genres (see ). By choosing this type of analysis, differences in the number of transcripts collected per genre and per show were taken into account.

With regard to the degree of involved vs. informational discourse, satirical news contained significantly more involved discourse than traditional news (t = 13.13, SE = 0.93, p < 0.001) and liberal news (t = 4.98, SE = 0.83, p < 0.001), but more informational discourse than political fiction (t = −9.39, SE = 0.58, p < 0.001; see ). No significant difference was found between satirical news and conservative news (t = 0.40, SE = 0.83, p = 0.69).

Table 2. Differences in linguistic register between satirical news and the integrated genres.

Concerning the degree of evaluative vs. referential discourse, satirical news contained significantly more evaluative discourse than conservative news (t = 5.07, SE = 0.88, p < 0.001). By contrast, satirical news contained significantly more referential discourse than political fiction (t = −3.65, SE = 0.59, p < 0.001; see ). The results suggested no significant differences between satirical news and traditional news (t = 0.92, SE = 0.99, p = 0.37) and between satirical news and liberal news (t = −1.33, SE = 0.88, p = 0.19).

Finally, in terms of the degree of deliberative discourse, satirical news contained significantly more deliberative discourse than political fiction (t = 6.98, SE = 0.45, p < 0.001) but significantly less deliberative discourse than liberal news (t = −7.34, SE = 0.63, p < 0.001) and conservative news (t = −3.55, SE = 0.64, p < 0.01; see ). We found no significant difference between satirical news and traditional news (t = 1.57, SE = 0.71, p = 0.13). Thus, the results showed that in case of all three register dimensions, satirical news scored in between political fiction and regular news, even though which differences with the news categories existed depended on the dimension. This means that the data supported H1.

Cluster Analysis

A cluster analysis was conducted to examine whether the multilevel results were consistent across satirical news shows (H2). The cluster analysis included all forty shows. The gap statistic, which has been shown to outweigh other methods for determining the optimal number of clusters (Tibshirani, Walther, and Hastie Citation2001), estimated that the cluster analysis best included five clusters (see Appendix A for the gap-statistic plot: https://osf.io/jruye/), which was in line with the number of genres. Because we were only interested in a single partitioning, we used non-hierarchical k-means clustering (Jain Citation2010) to identify the clusters.

The results showed that the regular news shows and political fiction shows each formed a separate cluster, indicating that these genre categories were indeed characterized by a unique register. Ten out of fifteen satirical news shows (e.g., Full Frontal with Samantha Bee, The Daily Show with Trevor Noah, The Tonight Show with Jimmy Fallon) also formed a separate cluster. This left five satirical news shows that clustered differently. One satirical news show was detected in the liberal news cluster: Last Week Tonight with John Oliver, possibly because it scored much higher on deliberative discourse than the other satirical news shows (see ). The other four formed a cluster with the conservative news shows: (1) Jimmy Kimmel Live, (2) Saturday Night Live (SNL), (3) The Late Late Show with James Corden, and (4) The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, which had in common that they scored high on referential discourse just like the conservative news shows (see ). Given the differences in clustering, the data did not support H2.

Apart from the result that the satirical news shows did not constitute one homogenous group, one other pattern in the plot is also worth emphasizing. That is, a 3D scatter plot, available on our OSF page: https://osf.io/jruye/, demonstrates that the satirical news cluster of ten shows is positioned independently and nearly in the middle of the clusters of the other genres. Thus, in line with the multilevel results, the cluster analysis seemed to support the hypothesis that satirical news score in between regular news and fiction in terms of linguistic register. This register is not only distinguishable from the registers of the genres that are integrated in satirical news, it also seems to be a balanced combination of the registers of the integrated genres. is a 2D representation of the 3D scatter plot. The interactive version allows you to rotate the plot and see which dot belongs to which show.

Figure 1. 3D scatter plot of the show means on the register dimensions.

Note. Click here for the interactive version of the plot.

Discussion and Conclusion

Implications of Main Findings

The objective of this study was to quantitatively test whether and how present-day satirical news shows are characterized by discursive integration, a concept described as a defining characteristic of satirical news shows (Baym Citation2005). In doing so, this study bridged research from the critical-cultural and quantitative traditions of journalism research. Moreover, the study answered calls for more research into the similarities and differences in characteristics between satirical news shows to improve our understanding of the genre as well as the effects exposure to the genre can have on audiences (Becker & Waisanen, Citation2013; Holbert et al. Citation2011).

Our findings showed that, on average, satirical news shows are characterized by distinctive register features because satirical news shows scored in between regular news shows and political fiction shows in different ways per register dimension, which supports the discursive integration hypothesis (H1). Findings also demonstrated that two-thirds of satirical news shows clustered together in a separate cluster that was positioned in the middle of those of traditional news, liberal and conservative news, and political fiction. This study thus confirms that discursive integration (Baym Citation2005) is at the heart of the majority of contemporary satirical news shows. Against our prediction, however, not all shows were found to be characterized by discursive integration (H2).

In contrast to Baym’s (Citation2005) discursive integration hypothesis, results showed that one-third of satirical news shows clustered together with non-satirical liberal and conservative news shows. This finding provides evidence for the validity of a different type of definition of satire than one using discursive integration (Baym Citation2005), which is that satire is pre-generic (e.g., Holbert et al. Citation2011; Knight Citation2004; Simpson Citation2003). The term refers to the notion that satire transcends the level of genre by actually manifesting through a genre (e.g., Holbert et al. Citation2011; Knight Citation2004; Simpson Citation2003). This view of satire is different from discursive integration because it assumes that satire is not a genre. Instead, satire is considered a type of higher-order discourse because it “needs to adopt a genre in order to express its ideas as representation” (Knight Citation2004, 4).

The term pre-generic implies the imitation of an original genre (Knight Citation2004), but our results demonstrate that the imitated genre can also be a hybrid genre since some scholars argue that liberal and conservative news are hybrid genres (e.g., Boukes et al. Citation2014). The reason being that opinionated news often deviates from genre conventions of traditional news towards those of entertainment genres by focusing more on emotions for example (Boukes et al. Citation2014). This means that this paper can reconcile research that has either defined satirical news shows by means of discursive integration or pre-genericness, because it shows a shared implication of both perspectives: satirical news shows rely on some kind of hybridity of genre conventions to convey criticism of a societal target. They are hybrid in two ways: they (1) combine conventions of news and fiction themselves (i.e., discursive integration; Baym Citation2005) or (2) manifest through the already hybrid genre of opinionated news (i.e., pre-generic; Knight Citation2004).

Variation between Shows

Why some satirical news shows clustered together with opinionated news shows could have different reasons. Last Week Tonight was found in the liberal news show cluster presumably because it contained a similarly high degree of deliberative discourse, which is in line with observations of the show containing many researched segments (Jennings, Bramlett, and Warner Citation2019). Previous research has also associated the use of deliberative discourse more with liberals than conservatives (Cichocka et al. Citation2016). This is because, on average, liberals score relatively high on integrative complexity: the degree to which individuals recognize and appreciate the legitimacy of multiple perspectives and their connections to each other (Carney et al. Citation2008). John Oliver thus seems to have embraced liberal news shows’ coverage style of synthesizing opposing political viewpoints by often carefully discussing arguments from both sides when conveying his critique.

There was also a group of satirical news shows that resembled conservative news shows in terms of their linguistic profile (i.e., Jimmy Kimmel Live, SNL, The Late Late Show with James Corden, and The Late Show with Stephen Colbert). Even though this study examined language use and not the expression of political opinions, this is a striking finding because all these satirical news shows have a liberal bias. In the case of SNL, an explanation for this finding could be the presence of parodies of conservative politicians and news reporters that therefore contained imitations of conservative speech, such as Alec Baldwin’s imitation of US President Donald Trump. A similar argument could be made for The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, which also often contains imitations. Nevertheless, Jimmy Kimmel Live and The Late Late Show with James Corden contain far fewer imitations than these two shows. More importantly, other shows that can contain imitations of political actors such as The Daily Show with Trevor Noah and The Tonight Show with Jimmy Fallon did not cluster together with the conservative news shows. This suggests that there is an alternative explanation as to why the four shows clustered the way they did.

This alternative explanation might have to do with the fact that the register dimension of referential discourse consisted almost entirely of nouns. Previous research has consistently shown that nouns have conservatives’ preference over adjectives and verbs when communicating their thoughts and opinions (Cichocka et al. Citation2016). This is presumably both due to the nature of the conservative ideology and that of nouns (Cichocka et al. Citation2016). Whereas liberals’ psychological needs have been shown to more likely involve openness and creativity, conservatives’ psychological needs typically tend to center around certainty (Carney et al. Citation2008). Nouns are more likely than other parts of speech to satisfy needs to manage uncertainty because they are more abstract and are subsequently more likely to facilitate inferences that are in line with prior beliefs (Cichocka et al. Citation2016). By using more nouns than other satirists, Kimmel, Cordon, and Colbert seem to share conservative news shows’ degree of certainty with which they present political news.

Limitations and Future Research

Some limitations of this study as well as recommendations of this study for future research could be pointed out. First, we could not include segment type as a variable in the study because many episodes of the satirical news and regular news shows were characterized by multiple segment types that often overlapped. Consequently, our results did not take an influence of segment differences (e.g., monologues are less interactive than sketches) on linguistic register into account. Future research could investigate the influence of types of show segments on register differences between satirical news and the integrated genres to further advance our knowledge of the various types of satirical news programming.

Furthermore, the included satirical news shows were all liberal in nature. We had to exclude Fox News’ The Greg Gutfeld Show from the study, the only conservative satirical news show broadcast in the US at the time of data collection, because no transcripts were available. Given that some scholars argue that there may be fundamental differences between liberal and conservative satirical news in characteristics (Dagnes Citation2012; Young Citation2019), future research could compare both types of satirical news shows on features such as linguistic register but also prosodic characteristics (e.g., laughter, intonation, and pauses), visual characteristics (e.g., show décor, camera shots, facial expressions) and, finally, the news items that are covered and the political opinions that are expressed to understand how liberal and conservative satirical news can be distinguished from each other.

Findings of this study also have relevance for journalism research beyond the topic of satirical news. More specifically, they challenge common conceptualizations of infotainment genres. Infotainment genres in journalism are typically defined as genres that have integrated a news genre and an entertainment genre (e.g., Otto, Glogger, and Boukes Citation2017). This study tested this hypothesis for the infotainment genre of satirical news. Our study reveals, however, that infotainment genres may not by definition involve the integration of a news genre and an entertainment genre. They could also exploit integrations that characterize existing hybrid news genres to achieve their own communicative aim. The classification of the two types of satirical news shows presented in this paper may therefore be used in future research to improve our understanding of the effects of infotainment genres in journalism across hybrid genre forms.

First of all, scholars could compare effects of regular news shows on viewing outcomes such as learning and persuasion to those of the two types of satirical news shows identified in this study. Previous research has shown that how large effects of satirical (vs. regular) news are on persuasion can depend on content factors such as how playful the type of humor used is (e.g., Horatian vs. Juvenalian satire; Holbert et al. Citation2011) and to whom the humor is directed (e.g., other-directed vs. self-directed; Becker Citation2012). Distinguishing in effects research between satirical news shows that seem to be characterized by discursive integration, on the one hand, and satirical news shows that reflect satire’s pre-generic nature, on the other, may help explain some of the variation in effect sizes of satirical news effects reported in the literature.

Future research could additionally examine effects of the two types of satirical news shows on regular news consumption. There is evidence that watching satirical news shows serves as a gateway to increased regular news consumption, but that audiences of certain shows are more likely to consume certain types of regular news (e.g., local news, cable news, news radio) than others (e.g., Young and Tisinger Citation2006). Future studies may look into whether the type of satirical news show as identified in this study could predict these regular news consumption patterns. Previous research suggests that such studies should not only focus on viewing frequencies, but also on how audiences transition between shows of different genres (Perks Citation2014).

To conclude, this paper presented a quantitative comparison of linguistic register between satirical news, regular news and political fiction, thereby testing Baym’s (Citation2005) discursive integration hypothesis in the modern American media landscape. Our findings demonstrated that satirical news shows can take two forms: (1) complete hybrids, which combine elements of regular news and political fiction, and (2) hybrid-genre echoes, which mimic an already existing hybrid genre. While the first group of shows represents evidence for the discursive integration hypothesis (Baym Citation2005), the second group represents evidence for claims made about satire being pre-generic (e.g., Holbert et al. Citation2011; Knight Citation2004; Simpson Citation2003). This study thus identified two categories of satirical news shows that symbolize the inherent genre hybridity of satirical news. Together, they provide new insight into satirical news’ position in the news media landscape.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Bob Brugman for his assistance in collecting the transcripts.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available on the Open Science Framework (OSF) at https://osf.io/jruye/.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For this reason, satirical news shows are sometimes also labelled news parody (e.g., Tandoc, Lim, and Ling Citation2018). News parody differs from satirical news, however, in that it typically has a humorous aim (not a critical one; Peifer and Lee Citation2019; Hutcheon Citation2000) and that it targets the genre itself (Kreuz and Roberts Citation1993; Hutcheon Citation2000). This means that, while genre imitation in news parody may be the objective, in satirical news it is the means through which to convey critiques of current affairs.

2 These tags were: direct WH-questions, discourse particles, independent clause coordination, past participle clauses, present participial clauses, pro-verb do, sentence relatives, stranded preposition, and that verb complements.

3 This decision applied to the following four out of 57 linguistic features: possibility modals (dimension 1 vs. dimension 2, 0.33 vs. 0.39), split auxiliaries (dimension 1 vs. dimension 2, −0.36 vs. 0.43), WH-clauses (dimension 1 vs. dimension 2, 0.41 vs. 0.32), and pied-piping relative clauses (dimension 1 vs. dimension 3, 0.33 vs. 0.35).

References

- Al-Surmi, M. 2012. “Authenticity and TV Shows: A Multidimensional Analysis Perspective.” Tesol Quarterly 46 (4): 671–694. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.33.

- Bates, D., M. Maechler, B. Bolker, and S. Walker. 2015. “Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4.” Journal of Statistical Software 67 (1): 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01.

- Baumgartner, J. C., and J. S. Morris. 2006. “The Daily Show Effect: Candidate Evaluations, Efficacy, and American Youth.” American Politics Research 34 (3): 341–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673(05280074).

- Baumgartner, J. C., J. S. Morris, and J. M. Coleman. 2018. “Did the “Road to the White House run Through” Letterman? Chris Christie, Letterman, and Other-Disparaging Versus Self-Deprecating Humor.” Journal of Political Marketing 17 (3): 282–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377857.2015.1074137.

- Baym, G. 2005. “The Daily Show: Discursive Integration and the Reinvention of Political Journalism.” Political Communication 22 (3): 259–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600591006492.

- Becker, A. B. 2012. “Comedy Types and Political Campaigns: The Differential Influence of Other-Directed Hostile Humor and Self-Ridicule on Candidate Evaluations.” Mass Communication and Society 15 (6): 791–812. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2011.628431.

- Becker, A. B., and L. Bode. 2017. “Satire as a Source for Learning? The Differential Impact of News Versus Satire Exposure on net Neutrality Knowledge Gain.” Information, Communication & Society 21 (4): 612–625. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1301517.

- Becker, A. B., and D. J. Waisanen. 2013. “From Funny Features to Entertaining Effects: Connecting Approaches to Communication Research on Political Comedy.” Review of Communication 13 (3): 161–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/15358593.2013.826816.

- Berkowitz, D., and D. A. Schwartz. 2016. “Miley, CNN and The Onion: When Fake News Becomes Realer Than Real.” Journalism Practice 10 (1): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2015.1006933.

- Bhatia, V. K. 1997. “The Power and Politics of Genre.” World Englishes 16 (3): 359–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-971X.00070.

- Biber, D. 1988. Variation Across Speech and Writing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Biber, D. 1995. Dimensions of Register Variation: A Cross-Linguistic Comparison. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Biber, D. 2014. “Using Multi-Dimensional Analysis to Explore Cross-Linguistic Universals of Register Variation.” Languages in Contrast 14 (1): 7–34. https://doi.org/10.1075/lic.14.1.02bib.

- Bolinger, D. 1972. Degree Words. The Hague: Walter de Gruyter.

- Boukes, M., H. G. Boomgaarden, M. Moorman, and C. H. De Vreese. 2014. “News with an Attitude: Assessing the Mechanisms Underlying the Effects of Opinionated News.” Mass Communication and Society 17 (3): 354–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2014.891136.

- Carney, D. R., J. T. Jost, S. D. Gosling, and J. Potter. 2008. “The Secret Lives of Liberals and Conservatives: Personality Profiles, Interaction Styles, and the Things They Leave Behind.” Political Psychology 29 (6): 807–840. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2008.00668.x.

- Cattell, R. B. 1966. “The Scree Test for the Number of Factors.” Multivariate Behavioral Research 1: 245–276. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr0102_10.

- Chafe, W. 1985. “Linguistic Differences Produced by Differences Between Speaking and Writing.” In Literacy, Language, and Learning: The Nature and Consequences of Reading and Writing, edited by D. R. Olson, N. Torrance, and A. Hildyard, 105–123. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cichocka, A., M. Bilewicz, J. T. Jost, N. Marrouch, and M. Witkowska. 2016. “On the Grammar of Politics: Or why Conservatives Prefer Nouns.” Political Psychology 37: 799–815. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12327.

- Crawford, W. J. 2008. “Place and Time Adverbials in Native and Non-native English Student Writing.” In Corpora and Discourse: The Challenges of Different Settings, edited by A. Ädel, and R. Reppen, 267–287. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Dagnes, A. 2012. A Conservative Walks Into a Bar: The Politics of Political Humor. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Esser, F., and A. Umbricht. 2014. “The Evolution of Objective and Interpretative Journalism in the Western Press: Comparing Six News Systems Since the 1960s.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 91: 229–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699014527459.

- Feldman, L. 2017. “Assumptions about Science in Satirical News and Late-Night Comedy.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Science of Science Communication, edited by K. H. Jamieson, D. M. Kahan, and D. A. Scheufele, 321–342. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Fonteyn, L., L. Heyvaert, and C. Maekelberghe. 2015. “How do Gerunds Conceptualize Events? A Diachronic Study.” Cognitive Linguistics 26 (4): 583–612. https://doi.org/10.1515/cog-2015-0061.

- Fox, J. R., G. Koloen, and V. Sahin. 2007. “No Joke: A Comparison of Substance in The Daily Show with Jon Stewart and Broadcast Network Television Coverage of the 2004 Presidential Election Campaign.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 51 (2): 213–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838150701304621.

- Friginal, E. 2013. “Twenty-five Years of Biber’s Multi-Dimensional Analysis: Introduction to the Special Issue and an Interview with Douglas Biber.” Corpora 8 (2): 137–152. https://doi.org/10.3366/cor.2013.0038.

- Gray, B. 2013. “More Than Discipline: Uncovering Multi-Dimensional Patterns of Variation in Academic Research Articles.” Corpora 8 (2): 153–181. https://doi.org/10.3366/cor.2013.0039.

- Grieve, J., D. Biber, E. Friginal, and T. Nekrasova. 2011. “Variation among Blogs: A Multidimensional Analysis.” In Genres on the Web: Computational Models and Empirical Studies, edited by A. Mehler, S. Sharoff, and M. Santini, 303–322. New York, NY: Springer.

- Hoffman, L. H., and D. G. Young. 2011. “Satire, Punch Lines, and the Nightly News: Untangling Media Effects on Political Participation.” Communication Research Reports 28 (2): 159–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2011.565278.

- Holbert, R. L., J. Hmielowski, P. Jain, J. Lather, and A. Morey. 2011. “Adding Nuance to the Study of Political Humor Effects: Experimental Research on Juvenalian Satire Versus Horatian Satire.” American Behavioral Scientist 55 (3): 187–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764210392156.

- Holbert, R. L., J. L. Lambe, A. D. Dudo, and K. A. Carlton. 2007. “Primacy Effects of The Daily Show and National TV News Viewing: Young Viewers, Political Gratifications, and Internal Political Self-Efficacy.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 51 (1): 20–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838150701308002.

- Huang, Y., and W. Ren. 2019. “A Novel Multidimensional Analysis of Writing Styles of Editorials from China Daily and The New York Times.” Lingua 235: 102781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2019.102781

- Hutcheon, L. 2000. A Theory of Parody: The Teachings of Twentieth-Century art Forms. New York, NY: University of Illinois Press.

- Jain, A. K. 2010. “Data Clustering: 50 Years Beyond k-Means.” Pattern Recognition Letters 31 (8): 651–666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patrec.2009.09.011.

- Jennings, F. J., J. C. Bramlett, and B. R. Warner. 2019. “Comedic Cognition: The Impact of Elaboration on Political Comedy Effects.” Western Journal of Communication 83 (3): 365–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/10570314.2018.1541476.

- Knight, C. A. 2004. The Literature of Satire. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Kreuz, R. J., and R. M. Roberts. 1993. “On Satire and Parody: The Importance of Being Ironic.” Metaphor and Symbol 8 (2): 97–109. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327868ms0802_2.

- LaMarre, H. L., K. D. Landreville, and M. A. Beam. 2009. “The Irony of Satire Political Ideology and the Motivation to See What you Want to See in The Colbert Report.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 14 (2): 212–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161208330904.

- Lee, H., and N. Kwak. 2014. “The Affect Effect of Satiric News: Sarcastic Humor, Negative Emotions, and Political Participation.” Mass Communication and Society 17 (3): 307–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2014.891133.

- Matthes, J., and A. Rauchfleisch. 2013. “The Swiss “Tina Fey Effect”: The Content of Late-Night Political Humor and the Negative Effects of Political Parody on the Evaluation of Politicians.” Communication Quarterly 61 (5): 596–614. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463373.2013.822405.

- Michaud Wild, N. 2019. “‘The Mittens of Disapproval are on’: John Oliver’s Last Week Tonight as Neoliberal Critique.” Communication, Culture & Critique 12 (3): 340–358. https://doi.org/10.1093/ccc/tcz021.

- Morrison, J. T. 2009. “Evaluating Factor Analysis Decisions for Scale Design in Communication Research.” Communication Methods and Measures 3 (4): 195–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312450903378917.

- Nini, A. 2015. Multidimensional analysis tagger (Version 1.3). http://sites.google.com/site/multidimensionaltagger.

- Otto, L., I. Glogger, and M. Boukes. 2017. “The Softening of Journalistic Political Communication: A Comprehensive Framework Model of Sensationalism, Soft News, Infotainment, and Tabloidization.” Communication Theory 27 (2): 136–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/comt.12102.

- Painter, C., and L. Hodges. 2010. “Mocking the News: How The Daily Show with Jon Stewart Holds Traditional Broadcast News Accountable.” Journal of Mass Media Ethics 25 (4): 257–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/08900523.2010.512824.

- Peifer, J., and T. Lee. 2019. “Satire and Journalism.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.871.

- Perks, L. G. 2014. Media Marathoning: Immersions in Morality. New York, NY: Lexington Books.

- Polk, J., D. G. Young, and R. L. Holbert. 2009. “Humor Complexity and Political Influence: An Elaboration Likelihood Approach to the Effects of Humor Type in The Daily Show with Jon Stewart.” Atlantic Journal of Communication 17 (4): 202–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/15456870903210055.

- Quirk, R., S. Greenbaum, G. Leech, and J. Svartvik. 1985. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman.

- Redeker, G. 1984. “On Differences between Spoken and Written Language.” Discourse Processes 7 (1): 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/01638538409544580.

- Sardinha, T. B., and M. V. Pinto. 2017. “American Television and off-Screen Registers: A Corpus-Based Comparison.” Corpora 12 (1): 85–114. https://doi.org/10.3366/cor.2017.0110.

- Scarcella, R. 2003. Academic English: A Conceptual Framework. University of California Linguistic Minority Research Institute. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6pd082d4.

- Shelke, N. M., S. Deshpande, and V. Thakre. 2012. “Survey of Techniques for Opinion Mining.” International Journal of Computer Applications 57 (13): 30–35.

- Simpson, P. 2003. On the Discourse of Satire: Towards a Stylistic Model of Satirical Humour. Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins.

- Swales, J. 1990. Genre Analysis: English in Academic and Research Settings. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Swan, M. 1996. Practical English Usage. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Szarkowska, A., J. D. Cintas, and O. Gerber-Morón. in press. “Quality is in the Eye of the Stakeholders: What do Professional Subtitlers and Viewers Think About Subtitling?” Universal Access in the Information Society, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-020-00739-2.

- Tandoc, E. C., Z. W. Lim, and R. Ling. 2018. “Defining “Fake News” A Typology of Scholarly Definitions.” Digital Journalism 6 (2): 137–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2017.1360143.

- Thomson, E. A., P. R. White, and P. Kitley. 2008. “‘Objectivity’ and “Hard News” Reporting Across Cultures: Comparing the News Report in English, French, Japanese and Indonesian Journalism.” Journalism Studies 9 (2): 212–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700701848261.

- Tibshirani, R., G. Walther, and T. Hastie. 2001. “Estimating the Number of Clusters in a Data Set Via the Gap Statistic.” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology) 63 (2): 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9868.00293.

- Tse, P., and K. Hyland. 2010. “Claiming a Territory: Relative Clauses in Journal Descriptions.” Journal of Pragmatics 42 (7): 1880–1889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2009.12.025.

- Waisanen, D. J. 2011. “Crafting Hyperreal Spaces for Comic Insights: The Onion News Network’s Ironic Iconicity.” Communication Quarterly 59 (5): 508–528. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463373.2011.615690.

- Wessler, H. 2008. “Investigating Deliberativeness Comparatively.” Political Communication 25 (1): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600701807752.

- Young, D. G. 2019. Irony and Outrage: The Polarized Landscape of Rage, Fear, and Laughter in the United States. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Young, D. G., and R. M. Tisinger. 2006. “Dispelling Late-Night Myths: News Consumption among Late-Night Comedy Viewers and the Predictors of Exposure to Various Late-Night Shows.” The Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics 11 (3): 113–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/1081180(05286042).

- Ziman, K., A. C. Heusser, P. C. Fitzpatrick, C. E. Field, and J. R. Manning. 2018. “Is Automatic Speech-to-Text Transcription Ready for use in Psychological Experiments?” Behavior Research Methods 50 (6): 2597–2605. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-018-1037-4.