ABSTRACT

The public broadcaster RTV Slovenia strategically relied on non-standard employment for its permanent workers until the courts ruled that this was unlawful about a decade ago. The ensuing process of standardising employment has led to the regular employment of about 500 “permanently outsourced workers” under various arrangements. To interrogate the inverse, the study tests the Streeckian “beneficial constraints hypothesis”, whereby a reduction of external numerical flexibility should push RTVS on to the path of socially more sustainable flexibility in its internal functions that prove to be economically beneficial. The process expanded the standard employment and the grounding for the collective organisation of newsworkers, while the prevailing imperative of “rationalising” the tendencies for the norm of work intensification with greater workloads, saturated working time, and basic reskilling in the newsroom. Unlike the process of “proletarisation” that has economically subordinated journalists through the process of professionalisation and its ideologisation that sought to align their interests with those of media owners, the study reveals patterns of the “creative destruction of journalism” in response to the worsening material conditions of professional journalism, adapting newswork to the evolving commercial modes of digitised communication, introducing the ideology of non-professionalism to reskilling, while exposing newsworkers to pauperisation.

Labour relations in journalism have historically been re-negotiated through the conflict between the corporate goals of media management to “rationalise” the labour process and the public (cl)aims of journalists based on the ideas of press freedom and professionalism (Hardt Citation1996; Cohen Citation2016; Örnebring Citation2018). Scholarship on journalist employment indicates that causality runs from capital’s drive for profitability through market pressures for cost-cutting to technological innovations, resulting in contingent and individualised labour with grave implications for unionism and the collective struggle (Deuze Citation2007; Paulussen Citation2012; Gollmitzer Citation2014; Cohen Citation2015; Salamon Citation2019). Slovenian journalism is no exception, more a case in point since it is now more characterised by impoverishment than professionalisation, degrading journalists as workers (Vobič Citation2015; Citation2020).

The public broadcaster RTVS strategically relied on non-standard labour based on civil law contracts, as student work or freelancing as “independent journalists”, until the courts declared that these practices were unlawful (Vobič and Slaček Brlek Citation2014). What we call the process of standardisation at RTVS has led to regular labour arrangements (with employment contracts that are open-ended or fixed-term, full- or part-time) for about 500 “permanently outsourced workers” (POWs) who previously held various non-standard employment arrangements, as stated in the Annual Report of RTVS (for 2019, 141). This case offers a unique opportunity to interrogate the inverse causality at work in the presence of the “politically imposed” re-regulation of employment as well as the role of digital technologies within a labour-hostile environment that insists on cutting costs also in public institutions, such as RTVS.

By combining critical political economy of media and the sociology of newswork, we explore the dynamics between larger politico-economic forces in the news industry and the normalisation of contingent labour relations, conditions and processes in the newsrooms. The main aim is to interrogate a Streeckian “beneficial constraints hypothesis” whereby the reduction of external numerical flexibility (of POWs) should push RTVS on to the path of socially more sustainable flexibility (of regularly employed workers) regarding its internal functioning that might turn out to be economically beneficial. We hypothesise that an externally imposed constraint on the hiring decisions of news publishers could result in a process that is inversely related to the dominant rationale in the news industry, one proceeding from politically stabilised employment to reskilling with the aim of forming a well-trained and functionally flexible workforce. Based on in-depth interviews with managers, unionists, journalists and other newsworkers as well as analysis of publicly available documents, we explore the material and discursive aspects of journalism-as-labour within larger social and technological contexts.

Theoretical and Historical Background

The (re-)Proletarisation of Journalism-as-Labour

Journalism started to become firmly embedded in the capitalist mode of mass production in the late nineteenth century. Technological innovations, the increasing degree of labour division and greater organisational complexity added to the pace in the newsroom (Örnebring Citation2010). In capitalist societies, journalism underwent a process of “proletarisation”: through industrialisation and economic subordination it became mechanised, marked by low status, poor working conditions, and standard employment (Cohen Citation2016, 69–70). While some left the occupation, those who stayed adopted distinct strategies whose outcomes not only paved the way for forging a professional ideology, but also the social status of journalism.

The collective organisation of journalism labour was patterned either on the “unionism of skilled and industrial workers” or “upper-middle-class societies of physicians and lawyers” (Nerone Citation2013, 450). By following patterns of unrest in other industries, unionised journalists helped to improve their living and working conditions (Cohen Citation2016, 76). However, the main way of organising was in line with the “professionalisation project” pursued by the news industry and press owners to counter the growing public criticism of the business (Nerone Citation2013, 448). The professionalisation of journalism, with its public service ethos, was, on one hand, an “‘adaptation manoeuvre’ to insulate” media owners “against profit-threatening commercial crises, class conflicts and public disenchantment with the press” and, on the other, the “proletarisation of professionals” by economically subordinating journalists, while ideologically aligning them with the property interests of a capitalist economy (Kaul Citation1986, 48). With a “brokered settlement” between press owners and the public, journalists were promised professional status and autonomy (Nerone Citation2013, 448), while the notion of professionalisation became a “major ideological force” of management in the separation of newsworkers, weakening their potential for a collective labour struggle (Hardt Citation1996, 31).

There have been parallel, even contradictory, attempts to counter the proletarisation of journalism. By trying to restore “the creativity of professional journalism”, some journalists opted for “freelancing” in their attempt “to gain control over the labour process and the terms of commodification of their labour power”, while only a few could live from journalism alone, often occupying the margins of the industry (Cohen Citation2016, 76–77). A systemic attempt was the institutionalisation of public broadcasting as a “deviation from a ‘normal’ pattern of capitalist production” (Brats and De Bens Citation2000, 8–9), historically helping to affirm standard employment arrangements and to mandate the professional journalism of publicly owned, funded and accountable organisations. However, profound social, regulatory and ideological changes have loosened the public service consensus, exposing public broadcasting to cuts in both funding and advertising revenue, in turn affecting employment (ILO Citation2014, 8). The various kinds of contingent and individualised arrangements in which journalists work under civil law contracts, as interns or even without any formal agreement, have become common in the news industry (Deuze Citation2007; Paulussen Citation2012; Gollmitzer Citation2014; Örnebring Citation2018; Salamon Citation2019).

The concurrent rise of neoliberalism and digitalisation did away with the historical separation of technical skills from journalism-as-labour (Örnebring Citation2010, 64). Driven by the incessant imperative of “rationalisation”, capital has seised the opportunity given by digital innovations to chop the labour process up into micro tasks, intensifying newswork as journalists are required to do more with less time (Cohen Citation2015, 112–114). While under the pretence of civic emancipation the “ideology of non-professionalism” suggests that “anyone can be a journalist”, the growing number of journalists resembles easily replaceable “information workers” (Splichal and Dahlgren Citation2016, 8). In this context, the legacy media, also including public broadcasters, have been going through a “newsroom convergence” process, re-configuring the labour process across traditionally separated departments by introducing bi- and multimedia journalism, re-shaping newsworkers’ identities, and re-arranging the labour relationship through a variety of social, economic and cultural tensions (Robinson Citation2011; Larrondo Citation2016). These transformations define the labour process of a rising number of easy-to-replace journalists, whose multimedia and interactive tasks have intensified newswork so as to meet the “need for speed”, while their workday is extended by the need to always be online, flexible and contributing to the 24/7 news cycle of diverse platforms (Vobič Citation2015, 34). This intensification of work has eliminated the downtime of journalists and other newsworkers and expanded their work assignments by transforming their skill-sets, even by forging new modes of newswork (Cohen Citation2015, 103).

While media owners and their managers tackle economic and financial crises by implementing new technologies and organisational re-structuring, employment arrangements and the labour process are open to continuous change and marked by uncertainty, shrinking professional autonomy and the undermining of employment rights (Deuze Citation2007; Cohen Citation2015; Örnebring Citation2018). With the share of permanently employed and empowered journalists dwindling, non-standard jobs have expanded as the whip of the external market and the promise of regular employment ensures their discipline and readiness to endure amid precarity (Cohen Citation2015), with public broadcasting organisations being no exception (Mosco and McKercher Citation2008, 119–125; Vobič and Slaček Brlek Citation2014). Although the dominant trend is that both solidarity and union membership are shrinking (Paulussen Citation2012, 193–194), unions are responding by merging to form temporary networks and developing long-term labour convergence strategies among newsworkers, while freelancers are experimenting in alternative forms of organisation and digitised struggle (Salamon Citation2019; Proffitt Citation2019).

While journalism-as-labour in the early twenty-first century ideologically rests on the image of the flexible, self-sufficient and self-branding journalist, studies show it has been difficult for journalists in a state of precarity to frame their problems as collective problems (Örnebring Citation2018). Journalism being “primed for precarity” has deep historical roots in the professionalisation process, with journalists largely accepting precarity as a “natural part of journalism” and in line with key professional ideas—individualism, entrepreneurship and meritocracy (ibid.). The normalisation of non-standard employment may today be denoted for its embeddedness in the re-articulated “old” process: “re-proletarisation” (Cohen Citation2016, 76–78).

Journalism-as-Labour in Slovenia: The Unique Case of RTVS

After the collapse of the Yugoslav socialism three decades ago, journalists’ transformation from self-managing newsworkers to salaried professionals has been neither abrupt nor unambiguous (Vobič Citation2015, 33). The “independent” capitalist Slovenia adopted a privatisation model that enabled newsworkers to acquire the majority shareholding. While this prevented ownership concentration in the media, already in the 1990s many sold their shares to state-owned trusts and companies (Vobič Citation2020). Although journalism established shared normative grounds associated with the libertarian ideas of press freedom, the media developed within “paternal commercialism” (Splichal Citation2000), diversifying journalism-as-labour with respect to employment arrangements, working conditions and social statuses (Vobič Citation2015, 38). The media has started to increasingly rely on the use of non-standard employment for strategic reasons, especially to bring labour costs down and make the workforce more flexible, also leading to differences among journalists in their social status and political relevance (Vobič Citation2013; Vobič and Slaček Brlek Citation2014). These boundaries have been strengthened by digitisation, which has not only intensified work, but also reshaped the basic skill-set in converging newsrooms (Vobič Citation2013, 43–64), while eliminating certain skills specifically to develop an easily replaceable workforce, commonly under non-standard employment arrangements (91–112).

Since the early 2000s, the national professional organisations—mainly the Slovene Association of Journalists (DNS) and the Slovenian Union of Journalists (SNS)—have continuously addressed non-standard employment issues based on civil law contracts, student work or the formalised freelance status of an “independent journalist” (Čeferin, Poler, and Milosavljević Citation2017). While DNS (est. 1905) works as a guild that seeks to promote the profession and its autonomy, SNS (est. 1990) is a craft union that brings together “in-house unions” of the leading legacy media, including RTVS, with a section of freelancers and individual members, aiming to protect journalists’ material and social interests and their labour rights and boost solidarity among union members. While various kinds of contingent employment with limited labour rights have been normalised, non-standard employment is not always precarious because some well-established journalists have used it to bring their performance-based salaries up and/or lower their income tax obligations (SNS Citation2014). There is no national collective agreement and although some media establishments have negotiated their own, these agreements are subject to the risk of gradual degradation or even being ended, bringing instability and sometimes even programmed layoffs (SNS Citation2020). SNS also acknowledged the “discrepancy” between the legalised norms and employment practices, stressing the cases of those working under non-standard arrangements (Jurančič Citation2008). Other reasons include weak staffing and the lack of coordination of the tax, labour and media inspectorates (ibid.), while the state authorities have been “inactive” and hardly intervened in precarity (Čeferin, Poler, and Milosavljević Citation2017, 59).

At RTVS, journalism-as-labour has been configured by the “hybrid” managerial processes, defined not only by the “public good” but by commercial tendencies as well as narrow political interests entering the programme and supervisory councils (Vobič Citation2020). While it is financed from licence fees (more than two-thirds of its annual income), RTVS gets its commercial incomes, mostly from advertising (about one-fifth), on the saturated market with commercial broadcaster getting more than half of the gross advertising expenditure in the years before the pandemic (ibid.). RTVS has strategically aimed to “rationalise” its radio, television and online news operations by raising productivity and cutting labour costs, including through “spatial, technological and staffing integration” and its still ongoing aim to build a “multimedia news centre” (RTVS Citation2004). Since RTVS is part of the public sector, the labour relationships and conditions there are regulated by the law, while journalists’ basic salaries, allowances and bonuses should be consistent with the public sector salary system. However, besides regularly employing civil servants, in the 2000s and 2010s RTVS importantly relied on various forms of non-standard employment as part of its “normal managerial practices” (Vobič and Slaček Brlek Citation2014, 32). Particularly younger journalists complied with this precarious labour landscape, while entertaining the prospect of regular employment in the unforeseeable future. There was workforce flexibility between professionals with job security and career development (who were the majority) and semi-affiliated peripheral newsworkers self-regarded as an “abstract mass” at a “variable cost” (27). While these relations “manufactured discontent” among precarious public journalists, they were “fatalistic” not only about individual arrangements but any potential for greater change (31–32). Although POWs supported the collective struggle idea among journalists, unionism as a social mechanism appeared as a “maintainer of the status quo” (ibid.). By the end of the last decade, a profound change was coming in the public broadcaster, but not instantly.

Under mounting public debate and ever more successful court cases (Jurančič Citation2008), in 2009 and 2010 the Court of Audit (Citation2013, 21–23) declared there were irregularities at the public RTVS in its arrangement of permanent workers holding various non-standard labour forms. RTVS formed a special taskforce to not simply develop measures in line with the agreement and the labour legislation, but to form strategies for altering the policies of hiring POWs and substituting the “outsourced” labour with “regular” labour (22). From the outset, all three “in-house unions” were involved: Coordination of Journalist Unions (part of the SNS), Union of Cultural and Artistic Creators, and Union of Broadcasting Workers. According to the Annual Report of RTVS (for 2019, 141), the decade of standardising employment led to the standard employment of about 500 workers who had previously worked in various non-standard forms, sometimes for years. In its last Annual Report (for 2020, 29), RTVS no longer reports POWs.

Reconsidering the Phenomenon of Non-standard Employment

Conventional theories of non-standard employment may explain why employers have few incentives to stabilise employment. Most of these perspectives start from Becker’s (Citation1962) theory of human capital that distinguishes between general and specific training. While general training is useful in many firms, specific training is only useful in the company that provides it. Since after receiving general training the wage of a worker in a competitive labour market would increase, the firm providing will be unable to capture the gains of the worker’s increased productivity. Thus, rational companies are only interested in financing specific training while the costs of general training are borne by the worker. However, even in the case of specific training the workers could quit and the firm would then have to bear the additional costs of training a new employee. Hence, according to Becker, a rational firm will try to stabilise the employment relationship with workers who possess firm-specific skills by offering them long-term employment guarantees and higher wages.

Recent academic work on non-standard employment mostly follows this line of reasoning and distinguishes different sectoral or occupational regimes of employment according to skill-specific requirements (Eichhorst and Marx Citation2015; Boyer Citation2014). Eichhorst and Marx (Citation2015) claim that firms shape preferences for non-standard employment through the specificity of their skill requirements and the labour market conditions for a given occupation. While skill requirements define the labour market’s breadth for a specific occupation, the labour supply and demand conditions determine the manoeuvring space firms have available in terms of a worker’s replaceability. These theories thus predict that when general skills prevail in the conditions of oversupply in the hob market—as seems to be the case with the highly routinised labour process in today’s digitised newsroom—companies have no incentives to stabilise employment. This is what the ideology of non-professionalism, strategies of digitisation of the labour process, and newsroom convergence entail as news publishers pursue flexibility and work intensification in the presence of an ample supply of candidates holding general skills from who to choose to retain as newsworkers in non-standard employment.

Becker’s theory starts from the non-structured, flexible, neo-classical labour market while causality runs from the investment in specific skills to the stabilisation of labour relations. Alternative perspective is presented by Wolfgang Streeck (Citation1997), who turns Becker’s argument on its head, rejecting economic functionalism in analysis of political and economic institutions. Claiming that politically imposed constraints on the self-interested behaviour of capitalist firms are needed not only to ensure socially desirable outcomes but also economic efficiency, he makes the case for what we call the inverse. Insofar as market-rational capitalist actors are free to pursue their interests as they see fit, Streeck (Citation1997, 199) argues, they will fail to utilise capacities in an optimal way and end up performing below their potential. The main reason for this outcome is that employers often pursue short-term gains or they opportunistically defect from strategies involving long-term commitments even when the latter are arguably much more sustainable and offer higher returns over a longer period (200). Constraints on the behaviour of self-interested firms, for example “rigid” regulation of the labour market and the corresponding stabilisation of employment, force them to introduce new techniques for successful operation, to explore opportunities for learning and innovation (203). Unable to pursue short-term strategies reliant on low wages, deskilling and a precarious workforce, companies might be forced to step up their investments in research and development that could allow them to pursue more demanding competitive strategies where the involvement of workers and their skills becomes an asset. In other words, they might discover that they want to become high-quality producers, pursuing long-term strategies comprising investments in a highly qualified and functionally flexible workforce. Thus, externally imposed constraints might prove to be economically beneficial by forcing producers to reorient themselves to high-quality production. While Becker explains the stabilisation of employment with a firm’s investment in specific skills, Streeck explains skill formation by means of politically imposed constraints that preclude the use of precarious forms and force them to stabilise employment. Enhanced functional flexibility does not necessarily imply investment in skills and a shift to quality production. “Job enlargement” might imply work intensification, which we define as an increase in the quantity of labour (i.e., workload) of a worker within a given timespan by means of “a closer filling-up of the pores of the working day, i.e., a condensation of labour” (Marx Citation1867/1982, 534). The erosion of job demarcations could simply mean a swift movement from one de-skilled task to another (Tomaney Citation1990, 37).

The employment standardisation process at RTVS offers settings to explore the “beneficial constraints hypothesis” whereby the serious reduction of external numerical flexibility is pushing the “hybrid” public broadcaster, as discussed above, on to the path of internal functional flexibility enabled by technological innovations and reskilling. Applying Streeck’s line of argument, this study hypothesises that an externally imposed constraint on the hiring decisions of news publishers could well result in a process that is inversely related to the one described above, one proceeding from politically stabilised employment to reskilling with the aim of forming well-trained and functionally flexible newsworkers.

The Case Study: Standardisation of Employment at RTVS

The standardisation of employment at RTVS was selected due to its “extreme” character (Flyvbjerg Citation2006, 229–230), providing richer data about the conditions and relations of journalism-as-labour than the “typical” case. The process appears to be inverse with respect not only to larger social relations in journalism-as-labour discussed above, but also to RTVS’ longstanding strategic reliance on non-standard employment for a big share of its staff. As noted, RTVS is a diverse institution whose television, radio and online newsrooms vary by the size of the workforce, the budget, the labour process, and technological innovations. The broadcaster has evolved as a “hybrid” organisation pursuing the “public good”, aiming to “rationalise” its production through digitisation and re-organisation, and striving to market its programmes to gain commercial incomes. While exploring the case as a complex “integrated system” (Stake Citation1995, 2) with boundaries, working parts and institutionalised rationales, the flexible design allowed adaptations to be made after the study proceeded and to preserve “the multiple realities, the different and even contradictory views of what is happening” (12). Two qualitative research methods were used, namely, document analysis and in-depth interviews, and one quantitative method, simple descriptive statistics.

Research Methods

Document analysis was adopted as “the means of constructing a specific version of a process” (Flick Citation2006, 252). While approaching documents as “standardised artefacts”, this research refrained from understating them as static and predefined, instead exploring them as “integrated into fields of action” (246). Thus, this case study analysed RTVS’ publicly available Annual Reports (ARs) for 2009–2019, and the pivotal ruling of the Court of Audit. By considering the institutional purpose of these documents, the analysis not only constructed a “specific version” of the employment standardisation, but—combined with descriptive statistical analysis of data from the Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia (SURS)—recreated financial situation and employment regulation as well as highlighted discontinuities in the strategic rationale concerning functional flexibility, technological innovations and reskilling at RTVS.

The in-depth interviews were structured according to the central problem matter, but were flexible enough to construct a site of knowledge production. To ensure the selection of interviewees reflected RTVS’ organisational structure, the particular inner logics, employment arrangements, and the labour process, 15 conversations with representatives of management, unionists, editors, journalists and other newsworkers were considered (). Sampling was established through a combination of controlling the employment standardisation process at RTVS and striving for a variety in the sample based on theoretical and contextual considerations, the worker’s place in RTVS’ organisational diversity, and anecdotal information. Potential interviewees were recruited by e-mail.

Table 1 . Interviewees.

Both authors performed as interviewers. While one conversation was a group interview with two interviewees—marked with an asterisk in —the others had one interviewee. Three interview guides were developed according to the particular positions held by the three interviewee groups in the standardisation process: management, unionists and workers. The guides were later adapted to each interviewee’s individual circumstances, the department they worked for, their employment arrangements and previous experience. The following problem themes were common: RTVS as a workplace and varieties in the labour process, discontinuities in the standardisation of employment, and technological innovations, training, and the re-organisation of work. The interviews had an average length of 1 h 53 min (the shortest: 61 min, the longest: 156 min) were conducted in-person in the Slovenian language, audio recorded, and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts are available in the Social Sciences Data Archive in Ljubljana (Vobič and Bembič Citation2021). The multistep analysis outlined was used to analyse the interview data (Kvale Citation1996). The results of the interview analysis were triangulated with insights arising from the document analysis, which allowed us to test the hypothesis by understanding the converging and diverging dynamics between the specific institutional version of the employment standardisation and the narrated experience of those in the middle.

Findings

To interrogate the “beneficial constraints hypothesis”, the study explores the “external constraints” RTVS has faced as a “hybrid” public broadcasting organisation in the last decade (i.e., worsening financial situation and the regulation of regular employment) and indicates the outcomes of the employment standardisation process (i.e., RTVS’ economic performance and the employment, functional flexibility and skill formation, and effects on newsworkers).

Reconsidering External Constraints

Deteriorating Financial Situation

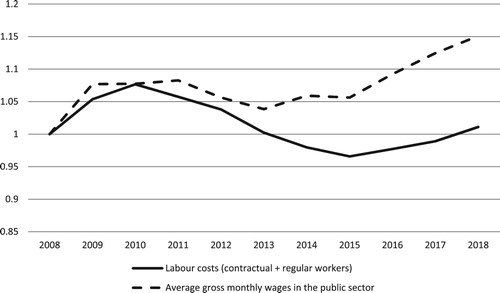

A salient factor shaping RTVS employment has been the financial situation, which deteriorated sharply after 2010. The management responded with “rational behaviour and efficient management as well as continuous reform of support processes and cost cutting” (AR for 2010, 32). One source of financial pressure has been the government’s reluctance to increase the obligatory RTVS fee since 2012, accounting for approximately two-thirds of total RTVS revenues (ARs for 2012–2019), while consumer prices increased in Slovenia by some 13.1% (January 2012–December 2019) (SURS data). Additional revenue was lost when the centre-right government lowered the RTVS fee by 5% in the first five months of 2013 (ARs for 2012–2013). Further, the great recession, amendments to legislation in 2012 and the increasingly tough competition from commercial television saw advertising revenues drop sharply by some 40% between 2010 and 2015 (ARs for 2010–2015).

The problem of decreasing revenues has been compounded by rising costs. Wages in the public sector (also applying to RTVS) started to increase once the austerity measures in the public sector were relaxed in 2015 (ARs for 2016, 2017, 2019). In 2018, nominal wages in the public sector were some 7% higher than in 2010 (SURS data). The process of the standardisation of employment has put additional strain on the costs since for every non-standard worker who became regularly employed the costs on average rose by some EUR 3,000 annually (AR for 2018, 6).

Until recently, RTVS had managed to cover its losses from its current operations by selling financial property from its mid-1990s’ investment made in Eutelsat Communications and in government bonds (AR for 2017, 19). By 2017, the stock of saleable financial assets had dropped substantially and could only cover a few years’ losses from current operations (AR for 2019).

Regular Employment Regulation

The process of employment standardisation has depended on the legislative regulation of labour, the agreements between RTVS and the unions, and the government’s measures for the public sector. The first piece of regulation was the agreement with SNS in 2010, followed by another agreement with all three “in-house unions”. These agreements created the path for standardising the employment of POWs.

The 2012 agreement was a response to the Revision Report of the Court of Audit which declared the employment practices regarding POWs at RTVS were illegal and demanded certain remedies (Court of Audit Citation2013, 40, 72). The agreement had two main elements. First, a gradual process for employing the POWs who met the educational requirements for the job was determined and, second, the contract workers agreed not to enforce their standard employment contracts by commencing legal procedures (22). Next came the government-imposed ban on the renewal of contracts with outsourced workers in 2012 that, while quite short-lived, was controversial, especially because it was followed by the government’s reduction of the obligatory RTVS fee for 2013 (AR for 2012, 11).

Another milestone was the agreement between RTVS and two of the unions in 2015. The 2015 agreement stipulated that RTVS would offer an employment contract to all POWs who met the educational requirements (UL RS 105/15). The last important piece of regulation came in 2018 in the form of a series of court rulings that required RTVS to offer employment contracts to those POWs with whom it has a de facto regular employment relationship, even those without the required education (AR for 2018, 5).

Interrogating the Beneficial Constraints

Employment and Labour Costs

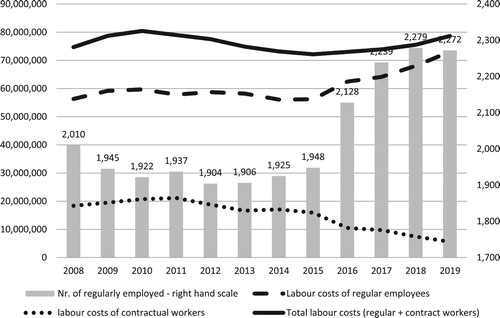

We observe three periods in the analysed data. In the first period (2008–2010), the number of regular (standard) employees was decreasing in line with the plan, but simultaneously the total labour costs rose by about 6.6% to EUR 80 million as the editors were filling vacant places with outsourced workers (). According to RTVS’ Director General, the rationale behind this substitution was, at least in part, the supervisory board’s insistence on cutting the number of employees.

I have to deliver on the number of employees. If, on the other hand, I give money away for some research, nobody will really care, at the end of the day. But if I surpass the planned number of employees, everybody will jump up and down at me. (DGint)

As the number of regularly employed fell, with managerial consent the editors turned to outsourced workers to create the programme. Thus, with a centralised policy of retrenchment, employing non-standard workers constituted a kind of a bypass around the employment plans.

The personnel department only dealt with those regularly employed […]. It has never dealt with workers under a contract. There was no central register of contract workers, no procedure as is the case with the regular employment. They [the editors] simply produced the people that they [needed]. (HHRint)

This decentralised approach suited both the general management and the newsrooms: while the staffing plans were duly observed, the editors obtained a disciplined workforce that it could keep on “a leash”.

The Director General said that he is not going to hire them because the plan does not allow it. The editor-in-chief said that it is better if they work for him in this way. He gives them the assignments. If they don’t deliver, they won’t be hired again the next month. (DGint)

In the second period (2010–2015), the total wage bill was gradually reduced to EUR 72 million in 2015, with two main factors behind this. First, the average wage of regular employees fell by some 5% in 2015 (ARs for 2010, 2017), roughly accounting for a EUR 4 million decrease in labour costs. This drop in the average wage can largely be attributed to the austerity measures in the public sector and the replacing of retiring experienced workers with high seniority bonuses with younger workers in receipt of starting wages. The management sought to minimise labour costs by turning the POWs turned into regular employees on the lowest rungs of the pay ladder:

[T]he institution had to sell shares in order to carry out the remediation of the employment situation. [The management] placed the newly hired workers, at least when it comes to journalists, in the lowest possible job for a journalist, the 30th salary grade. (CJUint)

Second, the cost of outsourced workers fell abruptly from a peak of EUR 21 million in 2011 to EUR 16 million in 2015 (ARs for 2011, 2017). The government-imposed ban on contract renewal with outsourced workers in 2012 and the financial uncertainty accelerated the standardisation process. The agreements between RTVS and the unions, on the other hand, ensured that the number of regular workers remained constant as outsourced workers occupied the vacant jobs left behind by regular workers who had left RTVS. Thus, the total number of workers—the sum of regular and outsourced workers—fell during this period ().

The third period (2016–2019) started with an agreement between the unions and RTVS in 2015. Total labour costs at RTVS rose significantly but in 2018 were still lower than in 2010. The main factor behind this increase was dual: a sharp increase in public sector wages when the austerity measures were relaxed in 2015, accompanied by the agreements between the government and the union confederations on the national level in 2016 and 2018. In contrast to the previous period, the 2016–2019 timeframe saw the number of regularly employed rise sharply from 1,948 in 2015–2,272 in 2019, which increased the total labour costs as average costs per standard employee were higher than for outsourced workers (AR for 2019, 6). While during this period RTVS standardised the employment of 495 POWs, the number of regular workers only rose by 324 since many of them replaced regular workers who had left (AR for 2019). That is, the total number of workers fell further during this period as the number of outsourced workers decreased by more than the net increase in the number of regular workers.

Not everybody ended up with standard employment. To prevent a de facto employment relationship arising, the management has limited the amount a contract worker may earn at EUR 500 gross, forcing them to look for additional sources of income or to simply leave:

In fact, we cannot let them work more, because otherwise we would have to employ them […] they cannot make ends meet with that [money] and most often they leave. (HMMCint)

Hence, those who were left behind and did not seek legal enforcement of their rights have simply “sailed away” (OJint). Others refused a regular contract because they were offered a low pay grade, meaning they would earn much less than they used to as “self-employed” able to take on high workloads.

While they used to earn EUR 2,000 when they were self-employed, now they can place them on a minimum wage. […] Of course, it is also about the money. You are well paid if you do a good job and if you work a lot. (IGDint)

Some refused regular employment, preferring to retain the student status with social benefits (subsidised lodging and meals) and various scholarships. In these cases, non-standard employment was not synonymous with precariousness.

They invited me several times and there was an option for regular employment. But I wanted to finish my studies, to make full use of the benefits of student life, enjoy some freedom and not be regularly employed. (RT, interview, 2019)

As soon as these student workers completed their studies and wanted to move on, the non-standard employment arrangement with imposed earning restriction led them to become precarious.

It worked well with student life, student lodging and all that. Now I have moved in with my girlfriend to the apartment she owns, but still the costs have risen […] If it’s going to stay this way, I’ll have to adjust somehow and find an additional job. (RJ2int)

For some newsrooms still relying on non-standard labour relations, student work presents a kind of entry point, enabling the management to test prospective workers, and simultaneously an indispensable source of flexibility:

Here we speak of the students in their first years of study – this is for them an entry point and we try to develop them […] This in turn provides us with flexibility which we really need. […] I cannot imagine the work without students, I truly cannot. (ECRAint)

Nevertheless, the large majority of POWs signed an employment contract during the observed period and only a relatively small fraction of total employment at RTVS’ newsrooms remained non-standard. Still, several non-core services continued to be outsourced, such as cleaning and security guards.

Functional Flexibility, Skill Formation and Quality Production

There is little doubt that the rearrangement of employment relations associated with the process of employment standardisation was a success in terms of “business rationalisation”. During the last decade, RTVS has not only regularised its employment relationships with its workforce, but managed to cut its total labour costs by some 6%, bringing them down to the 2008 level (). This suppression of labour costs is impressive since the average wage in the public sector system rose by about 7% in the same period.

To achieve this “success”, RTVS has turned to the more intensive use of internal sources by means of enhancing functional flexibility. As the data show, the workload has gradually risen for the existing regular employees and the dwindling number of outsourced workers. For example, in 2012 and 2013 when the expenditures for outsourced workers declined drastically and the number of regular workers marginally diminished as well, the reports state that:

Out of five employees who retired only three were replaced. […] The situation in certain newsrooms has reached a critical point and is becoming unbearable given the amount of work. (AR for 2012, 36)

[I]n 2013, we leaned on our internal sources, on regular employees more than ever before in order to fill the gaps that opened due to the shrinking funds for contract workers. (AR for 2013, 20)

From the perspective of regular workers, this successful “business rationalisation” was a form of work intensification, some of it springing from the persistent managerial attempts to enforce “bi-mediality” (DGint), converging the radio and television news production:

For there is always something suboptimal. We could certainly do more by going towards bi-mediality, multitasking, and gaining additional economies. (DGint)

Rationalisation is [a word] used by managers as a nice way to say reduction of employees. But what does it mean for the workload of these employees? […] Now even my colleagues from radio work for the television. […] For instance, […] a radio journalist who went to France has also reported for television. (TJint)

Much the same goes for the non-standard workers. As one student worker stressed, in the newsroom the number of assistant producers was reduced while the volume of work has remained the same:

If half a year ago there were three workers for a given term and two remained in the evening for [the evening news programme] Odmevi, now there are only two left. […] The scope of work is essentially the same but it is more intensive now. (ATVNPint)

The bulk of these changes in RTVS newsrooms came in the form of new online tasks with two interrelated developments. First, in 2012 the online newsroom, the RTVS Multimedia Centre (MMC), lost its autonomy and became “subordinated” to the radio and television programmes (AR for 2012, 78). This change inter alia facilitated stronger collaboration between various production units as broadcast journalists started to increase the volume of their online contributions. According to the data, the share of contributions going from broadcast newsrooms to MMC increased on a yearly basis (AR for 2012, 78; 2013, 74; 2014, 79). Second, some newsrooms retained their own websites and encouraged their journalists to extend their work online and boost their circulation by posting them on online social networks:

I personally never had a Facebook or Twitter account. But then it came that as journalists we need all these accounts to communicate and spread our work in this area. […] This represents additional obligations, though I do not see them as a major thing. But, yes, then you have to write an Internet article. […] This is definitely some kind of additional workload. But it is something that the younger generations take for granted. (RJ1int)

However, reducing the number of workers and spreading the workload among the remaining ones does not require strategic skill development. Simultaneously, additional routinised online tasks in broadcasting newsrooms does not have much in common with creating a creative multi-skilled worker. Quite the opposite, online journalists’ work mostly seems routinised and deskilled. As one interviewee put it, a newcomer at MMC becomes acquainted with the job and capable of performing the tasks by themselves “in about 3 days” (OJint). Here changes in the organisation of work hardly entail reskilling because the additional tasks only require basic online skills. Thereafter, the single most important aspect of functional flexibility that enabled RTVS to accomplish success in “business rationalisation” was the work intensification which has little to do with job enrichment or increased autonomy.

There are certain areas where attempts to transform the labour process and at substantial skill enlargement are being made. One example is the television newsroom where teamwork practices were designed with workers crossing the job demarcations between “technical” and “editorial” work. As the Editor-in-Chief of the Television News Programmes explained:

According to my plan, the video editor, at least those who have the best knowledge of the news contents, would be given a job on the desk … a kind of editor, a video producer who is autonomous enough in order to create video contents for our programmes. (ECTVNint)

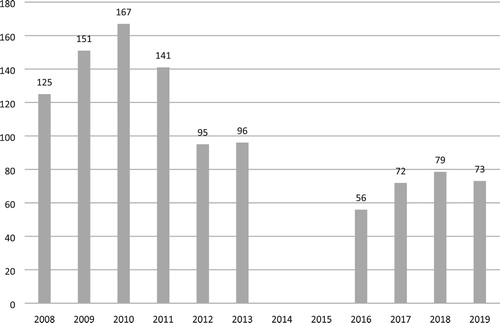

Such attempts to create a broadly skilled workforce are an exception. As data on training expenditures show, the organisation used to invest in skill formation, but the pressures for cost containment brought a sharp decline. Training expenditures per employee in 2019 were considerably below the 2010 level, signalling that the adding of routine tasks to the existing set of duties did not require much training ().

The data do not support the hypothesised turn to high-quality production. The constant cost-cutting pressures seem to have prevented several production units from realising their potential. The newsrooms continuously report their inability to realise “the plan”:

The situation in the area of finances and staffing established with the completion of the employment process of long-term [outsourced] workers, at the end of March 2016, and the reduced staffing and financial plan for the Regional Centre of Koper Capodistria for 2016 has caused a substantial reduction of production capacities for programmes and projects as well as for funding contract [outsourced] workers. […] Despite the extreme rationalisation and multi-tasking on the part of the great majority of employees […] we were unable to realise the programme and production plans at a level comparable with 2015. (AR for 2016, 74)

The evidence suggests that with the process of employment standardisation the organisation achieved significant economies by switching to functional flexibility, mostly accompanied by work intensification with reskilling rarely aimed at quality production.

Effects on Newsworkers

With respect to the benefits of the constraints for the workers in RTVS newsrooms, the data indicate they were affected in different ways by the employment standardisation. First, there appears to be little doubt that the status of the former POWs has improved considerably since they moved from insecure work to standard employment that grants them a certain level of job security. For instance, as the interviews indicate, the newsrooms used to rely on non-standard work as a sort of “flexibility buffer”:

It’s fine if you have at least a few students who enable you to cover […] certain peaks […] You could do it with overtime, but it is good to have some workers that can work a bit more or a bit less. (HMMCint)

However, what the organisation welcomed as a source of flexibility meant an unpredictable time schedule and great income insecurity for the “permanently outsourced”:

You never know how many hours you will actually work. […] First, the schedule is set for the regular workers and then the remaining holes are filled by the students, contract workers, the self-employed and all that. (OJint)

In turn, this affected non-standard workers who were, as a rule, willing to work longer hours and more intensively than the regular workers to please the editors and secure for themselves a renewal of their contract. In some cases, high job insecurity placed contract workers in relations of fierce competition where the prise was regular employment:

He will try to push himself very hard in order to get an employment contract. It is stupid because it is a rat race. (TVNPint)

The standardisation of employment substantially alleviated these pressures. Our interviewees from central management admitted that once they held a standard employment contract, the workers started to demand the minimum standards guaranteed by both the Labour Code and their contracts:

[E]ditors and other managers complain that before, when there were contract workers, they did all that [was asked from them] and they were able to earn more. Now, when they are regularly employed […] they read their job descriptions and we are bound by working time [regulations] and so on. (DDGint).

Being much more strictly regulated, the standard employment “[f]orces [the worker] to rest” (TJint). Moreover, the outsourced workers lacked paid holidays, sick leave and other elements of social security that come with standard employment. They also did not enjoy a stable place for work, such as a desk and a computer.

Second, the short-term benefits for regular workers are less straightforward. As shown above, regular workers encountered work intensification. While the POWs were cheaper, the conversion from civil to regular employment contracts meant, ceteris paribus, an increase in costs. Fearing that this might affect regular workers, the representatives of workers supported the supervisory board’s demands that management minimise the costs of the labour standardisation:

And then we said: “How much it will cost?” and we really pressed him [the Director General] hard because you have to take care not to cause too much of a financial shock to the institution. And I think that it was because we picked on him that he has to take care about the costs that the [newly employed] journalists and others got such low pay grades. […] Now we are faced with a new challenge. There is no more money […] and when the money runs out it will be the [regularly] employed to suffer the consequences. (CJUint)

The cost pressures on regular workers created adverse “political effects” by eroding the unity of newsworkers within the organisation. Yet, the long-term political effects for the regular workers seem more favourable. As explained by another union representative, outsourced workers were difficult to unionise and unions even treated them as some kind of strike-breakers (UBWint). This has changed for the better with the standardisation process.

Discussion and Conclusion

The case study evaluated the Streeckian hypothesis that constraints on the use of non-standard employment are linked not only to social sustainability but also to the competitive advantage of high-quality production, based on a functionally flexible workforce created by investments in skills and, in turn, by long-term quality production relations with workers (Streeck Citation1997). The findings of the study at the public RTVS support the functional flexibility part of the hypothesis. Doubly restrained by restrictions on the use of non-standard employment and a tight budget brought about by the stagnation of RTVS fee, falling advertising revenues and depletion of the stock of saleable financial assets, the organisation has managed to buffer the costs of employment standardisation coupled with the increase in collectively agreed public sector wages by resorting to a functionally flexible workforce. The “in-house unions” have not forced the employment standardisation process that was “politically imposed” by the courts’ decisions, but acted as “partners” supporting the employment of POWs, but they also “pressed” the management to “take care” of the financial implications of the process for the organisation. Generally, the standardisation process was a success in “business rationalisation” terms.

Still, the high-skills and high-quality part of the hypothesis fared less well. The “economic success” was not about a turn to functional flexibility requiring an investment in skills but hinged upon the reduction of total employment by increasing the work intensification by eliminating the downtime of workers, particularly journalists, and expanding their work assignments that mostly only required basic general skills. Instead of turning to quality production, the reduction of total employment started to take a toll on the programme once the working time became saturated and workers were unable to take on additional workloads. The effects of the standardisation process on workers appear to be positive, although the benefits have been spread unevenly. The process benefited the POWs by increasing their job and income security, providing more stable work conditions as well as the stricter observance of regulations regarding rest periods, paid leave and maximum working hours. For standard workers, the economic benefits seem less straightforward, but their “political gains” are substantial since a more uniform situation across the workforce enables them to forge a more unified front when facing the challenges lying ahead.

The study’s main contribution lies in the findings that indicate a “dualism of the standardisation of employment” at RTVS and the limited potential to counter the historical tensions arising from journalism-as-labour (Hardt Citation1996; Cohen Citation2016; Örnebring Citation2018) and organising newsworkers (Mosco and McKercher Citation2008; Salamon Citation2019). The process expanded the pool of permanent workers and the grounding for collective organisation of newsworkers, while the prevailing imperative of “rationalisation” at the “hybrid” public broadcaster normalised tendencies for work intensification with greater workloads, saturated working time, and basic reskilling in the newsroom, particularly for journalists. The study also contributes to critical assessments of the “proletarisation of professionals” in journalism. Unlike the parallel historical processes of “proletarisation” that economically subordinated journalists and professionalisation and its ideologisation which sought to align their interests with those of media owners (Kaul Citation1986; Hardt Citation1996), the study indicates the “creative destruction of journalism” in response to the material deterioration of professional journalism, adapting newswork to the evolving commercial modes of digitised communication, re-affirming the ideology of non-professionalism, while exposing newsworkers to pauperisation (Cohen Citation2015; Splichal and Dahlgren Citation2016). In this sense, the “re-proletarisation” of journalists has less to do with formal employment arrangements and the “old” ways of economic and technological subordination, and more with “new” larger material conditions in the digitised communication and ideological visions of “de-professionalisation”, normalising difficulties in journalists’ pursuit of public (cl)aims, maintaining long-term job security, and practising certain skills.

These problems are deeper when the historical tendencies of “paternal commercialism” (Splichal Citation2000) in Slovenia’s media environment are considered, defining the particular “hybrid” nature of RTVS. While nearly exhausting the stock of its financial assets so as to continually cover its losses accrued over the last decade, RTVS seems to be living on borrowed time in the face of external political pressure—discursive and material. Besides the current Prime Minister tweeting that there are “too many” workers at RTVS and they are “overpaid” (@JJansaSDS, 20 March 2020), prompting the Council of Europe (Citation2020) to issue its “media freedom alert”, the Slovenian state’s official response described the standardisation of employment at RTVS as “making a mockery of all the citizens who are paying monthly contributions for this institution”. Moreover, in July 2020 the government proposed legislative amendments aimed at divesting RTVS’ funds, redirect its fee revenues to other media, and forcing RTVS to compensate for the lost income through “liberated” advertising. Insofar as a public broadcaster’s mission is to provide a space for the confrontation of incommensurable ideological discourses, in an era when ideological dilemmas tend to be supressed and subordinated to the demands for competitiveness as a sine qua non of national survival and prosperity, no ideological dilemma can arise that makes the provision of such a framework largely superfluous. If RTVS and its workers are to carry out their mission, not only does a broader class-based approach in union and labour organisation countering commercialisation and precarity need to replace the ideologies of the professionalisation, but greater societal changes are also required if journalists together with other newsworkers are to become progressive forces.

The weaknesses of a single case study lie in the ability to generalise its findings to the wider problems of journalism-as-labour. To overcome these limitations, future research should not only expand the number of cases to explore varieties of employment standardisation, but also adopt other qualitative (focus groups, observations) and quantitative methods (surveys) to further the sociology of newswork in journalism research by integrating the material and discursive aspects of journalism-as-labour with the social relations, professional norms and organisation structures of media establishments.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Becker, G. 1962. “Investment in Human Capital.” Journal of Political Economy 70 (5): 9–49.

- Boyer, R. 2014. “Developments and Extensions of ‘Régulation Theory’ and Employment Relations.” In The Oxford Handbook of Employment Relations, edited by A. Wilkinson, G. Wood, and R. Deeg, 114–153. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Brats, K., and E. De Bens. 2000. “The Status of TV Broadcasting in Europe.” In Television Across Europe, edited by J. Wieten, G. Murdock, and P. Dahlgren, 7–22. London: Sage.

- Čeferin, R., M. Poler, and M. Milosavljević. 2017. “Prekarno delo novinarjev kot grožnja svobodi izražanja.” Javnost–The Public 24 (suppl.): S47–S63.

- Cohen, N. 2015. “From Pink Slips to Pink Slime.” The Communication Review 18 (2): 98–122.

- Cohen, N. 2016. Writers’ Rights. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Council of Europe. 2020. “Slovenian Prime Minister Attacks Radiotelevizija Slovenija on Social Media.” N°34/2020: 26 March. https://go.coe.int/FzZRD.

- Court of Audit. 2013. “Porevizijsko poročilo: Popravljalni ukrepi Radiotelevizije Slovenija.” http://www.rs-rs.si/fileadmin/user_upload/revizija/492/RTV_PP0910_porev.pdf.

- Deuze, Mark. 2007. Media Work. Cambridge: Polity.

- Eichhorst, W., and P. Marx. 2015. “Introduction.” In Non-standard Employment in Post-industrial Labour Markets, edited by W. Eichhorst, and P. Marx, 1–20. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Flick, U. 2006. An Introduction to Qualitative Research. London: Sage.

- Flyvbjerg, B. 2006. “Five Misunderstanding About the Case-Study Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 12 (2): 219–245.

- Gollmitzer, M. 2014. “Precariously Employed Watchdogs?” Journalism Practice 8 (6): 826–841.

- Hardt, H. 1996. “The End of Journalism.” Javnost–The Public 3 (3): 21–41.

- ILO. 2014. “Employment Relationships in the Media and Culture Industries.” https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_dialogue/@sector/documents/publication/wcms_240701.pdf.

- Jurančič, I. 2008. “Dninarstvo na novinarskem trgu delovne sile”. Medijska preža, May. http://mediawatch.mirovni-institut.si/bilten/seznam/31/polozaj/.

- Kaul, A J. 1986. “The Proletarian Journalist.” Journal of Mass Media Ethics 1 (2): 47–55.

- Kvale, S. 1996. Interviews. London: Sage.

- Larrondo, A., et al. 2016. “Opportunities and Limitations of Newsroom Convergence.” Journalism Studies 17 (3): 277–300.

- Marx, K. 1867/1982. Capital, Volume 1. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Mosco, V., and C. McKercher. 2008. The Laboring of Communication. Lanham: Lexington.

- Nerone, J. 2013. “The Historical Roots of the Normative Model of Journalism.” Journalism 14 (4): 446–458.

- Örnebring, H. 2010. “Technology and Journalism-as-Labour.” Journalism 11 (1): 57–74.

- Örnebring, H. 2018. “Journalists Thinking About Precarity.” International Symposium on Online Journalism 8 (1): 109–127.

- Paulussen, S. 2012. ““Technology and the Transformation of News Work”.” In The Handbook of Global Online Journalism, edited by E. Siapera, and A. Veglis, 192–208. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Proffitt, J. M. 2019. “Solidarity in the Newsroom.” Journalism 146488491986003.

- Robinson, S. 2011. “Convergence Crisis.” Journal of Communication 61 (6): 1122–1141.

- RTVS. 2004. “Strategija dolgoročnega razvoja RTV Slovenija 2004–2010.” https://www.rtvslo.si/files/ijz/strategija_rtv_slovenija_2004-2010-mediji-6-9-05.doc.

- Salamon, E. 2019. “‘Freelance Journalists’ Rights, Contracts, Labour Organizing, and Digital Resistance.” In The Routledge Handbook of Developments in Digital Journalism Studies, edited by Scott Eldridge II, and Bob Franklin, 186–197. London: Routledge.

- SNS. 2014. Samostojni novinarji. https://novinar.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/PREKERCI20141.pdf.

- SNS. 2020. “Medijski boj.” 23 January. http://sindikat-novinarjev.si/1167-2/.

- Splichal, S. 2000. “Reproducing Political Capitalism in the Media of East-Central Europe.” Medijska Istraživanja 6 (1): 5–17.

- Splichal, S., and P. Dahlgren. 2016. “Journalism Between De-professionalisation and Democratisation.” European Journal of Communication 31 (1): 5–18.

- Stake, R. 1995. The Art of Case Study Research. New York, London: Sage.

- Streeck, W. 1997. “Beneficial Constraints.” In Contemporary Capitalism, edited by J. Hollingsworth, and R. Boyer, 197–219. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Tomaney, J. 1990. “The Reality of Workplace Flexibility.” Capital and Class 14 (1): 29–60.

- Vobič, I. 2013. Journalism and the Web. Ljubljana: Založba FDV.

- Vobič, I. 2015. “Osiromašenje Novinarstva.” Javnost–The Public 22 (suppl.): S28–S40.

- Vobič, I. 2020. “Slovenia.” In The Sage International Encyclopedia of Mass Media and Society, edited by D. L. Merskin, 1584–1587. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Vobič, I., and B. Bembič. 2021. Segmentacija nestandardnega zaposlovanja v medijih, 2021 [dataset]. Ljubljana: Social Sciences Data Archive. https://doi.org/10.17898/ADP_ZAPMED21_V1.

- Vobič, I., and A. S. Slaček Brlek. 2014. “Manufacturing Consent Among Newsworkers at Slovenian Public Radio.” Javnost–The Public 21 (1): 19–36.