ABSTRACT

The transformation of both journalism and the European education landscape opened up a debate about the challenges of digitalisation and the aims of adequate journalism education and training programs. The article discusses how education institutions draw on journalism education discourse, how they adapt their programs in order to respond to the practical demands of professional journalism in the digital age, and which skills and knowledge are considered as the core of journalism education. In addition, it contributes to journalism theory with the development of a dispositive of journalism. This theoretical framework is employed to interpret the status quo of curricula and teaching practices in relation to journalism practice. The empirical case study of journalism training and education includes a comprehensive content analysis of sixty-seven programs and 1818 individual courses in Austria, and guided interviews with twenty-nine stakeholders about the status quo and the challenges of an adequate journalism education. Results show that the digitalisation of journalism is fully integrated in the curricula and that educators are aware of trends in both education discourse and journalism. The results also point at gaps regarding innovation and the teaching of certain topics, and show possible reasons why education practice lags behind education discourse.

Introduction: Changes in Journalism, Changes in Education

Digitalisation has had a profound impact on the technological, economic and social foundations of journalism and changed journalistic skills and work processes in many ways. This transformation coincides—and is partly related to—an intensification of the discourse about journalism’s role in society: On the one hand, journalism comes under pressure from governments and political interest groups and its democratic worth is being questioned by those who see it as little more than the mouthpiece of power elites. On the other hand, we can detect a growing sensitivity regarding the societal role of journalism and a renewed interest in strengthening journalistic quality.

At the same time, journalism education is undergoing changes as well. In many countries, a growing number of educational institutions and programs lead to more competition, and in Europe the Bologna process, the European Qualification Framework and the ongoing exchange among journalism educators lead to more standardization on an international level (Nowak Citation2019). Education institutions not only face the task of preparing students for a rapidly changing work environment, which is growing ever more complex. They often find themselves in education markets with constant restructurings, adaptations and increased competition.

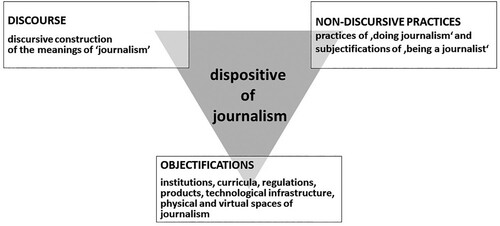

This article explores how education and training institutions draw on academic discourses about journalism education, how they adapt their programs in order to respond to the demands of professional journalism in the digital age, and which skills, knowledge and values should ultimately form the core of journalism education. In addition, it contributes to journalism theory with the development of a theoretical and analytical framework: The “dispositive of journalism” is based on Foucault’s (Citation1980) concept of dispositif and its subsequent development by the German Critical Discourse Analysis and Sociology of Knowledge Approach (Jäger and Maier Citation2016; Bührmann and Schneider Citation2008; Keller Citation2018). In brief, it consists of the relations between journalism discourse, non-discursive journalistic practices and the manifest objectifications of discourses and practices—education institutions and curricula being a part of the latter.

The theoretical framework is described in in section two. Section three discusses the current debates and trends in journalism education, followed by sections on the methodology and results of an empirical case study of education and training programs in Austria and their relation to both education discourse and practices.

Theoretical Framework: The Dispositive of Journalism

In media and communication studies le dispositif has been translated as both apparatus (following the English editions of Foucault’s work and a seminal text by Jean Baudry) and more recently as dispositive (cp. Bussolini Citation2010). Within this field of research the concept is for the most part used to theorize the ideological effects of situated media technologies such as the cinematographic apparatus (Baudry Citation1975), the television dispositive (Hickethier Citation1995), the internet apparatus (White Citation2006) or the social media dispositive (Zajc Citation2015), which are viewed as apparatuses/dispositives in their own right. Other works focus on the practices with which subjects constitute themselves in their digital, mobile and networked interactions—and therefore less on the relationship between subjects and media technologies than on the relationship between subjects as mediated by media technology (Dorer Citation2008; Steinmaurer Citation2016). Finally, a more recent branch of research is centered on practices of surveillance and control, for which media provide the technological infrastructure (e.g., Couch et al. Citation2015; Romele et al. Citation2017).

This article extends the use of le dispositif in media and communication studies by introducing a “dispositive of journalism” with which historical and current developments of journalism can be conceptualized and empirically observed with regards to actors’ journalistic practices, the material manifestations of journalism, and not least the discursive understanding of what characterizes journalism. It follows Bussolini’s (Citation2010) proposal to use the term dispositive instead of apparatus in order to delineate the strategic arrangement which has what we think of as news as its outcome instead of concentrating on the more concrete technical devices (distribution channels, investigative methods, genres etc.) that these strategies put into action. In contrast to other applications of the concept of dispositive in media and communication, the focus is on the historically contingent construction of journalism as an object of investigation, and on the strategic function of the dispositive as exemplified by Critical Discourse Analysis and the Sociology of Knowledge Approach rather than communication processes in general or the more technology-oriented apparatus theory approaches.

Arguably the most comprehensive and accessible definition of a dispositive by Michel Foucault stems from an interview conducted by French psychoanalysts in 1977. During their conversation, Foucault was asked about the “meaning or the methodological function” (Foucault Citation1980, 194) of the term dispositive and responded with the following description:

What I'm trying to pick out with this term is, firstly, a thoroughly heterogeneous ensemble consisting of discourses, institutions, architectural forms, regulatory decisions, laws, administrative measures, scientific statements, philosophical, moral and philanthropic propositions - in short, the said as much as the unsaid. Such are the elements of the apparatus. The apparatus itself is the system of relations that can be established between these elements. Secondly, what I am trying to identify in this apparatus is precisely the nature of the connection that can exist between these heterogeneous elements. … Thirdly, I understand by the term “apparatus” a sort of - shall we say - formation which has as its major function at a given historical moment that of responding to an urgent need. The apparatus thus has a dominant strategic function. (Foucault Citation1980, 194–195)

While it is understood that “there is nothing specifically social which is constituted outside the discursive” (Laclau Citation1980, 87), a methodological distinction is made between discourse as linguistically performed practices (Jäger and Maier Citation2016), and the non-discursive practices, whose meanings are no longer negotiated in discourse. As subjectifications they have become unquestionable self-evidences which need no explication, or a habitualized “know how to do” which can no longer be explicated because it has become part of the “flesh and bone” (Bührmann and Schneider Citation2008, 100).

Summarizing these considerations, the dispositive of journalism is conceptualized as the historically contingent interplay of journalism discourse, non-discursive journalistic practices and their objectifications, whose purpose is to react to a specific urgent need—namely the technological and social transformations of journalism (cp. ). Located on the meso-level, it produces social change and responds to it, thus mediating “between societal causes and consequences of what is occasioned by the dispositive” (Bührmann Citation2010, 26).

The journalism discourse delineates the borders between journalism and other practices of communicating information. Thematically, it is the place where journalism’s legitimate actors, acceptable practices, functions for society, and indeed all notions about contemporary and future journalism are contested and agreed upon. Discourses consist of interconnected “discourse strands”, each of which “centers on a common topic” (Jäger and Maier Citation2016, 121), e.g., professionalization, values or education.

The journalism discourse both draws from and influences the non-discursive journalistic practices of producing and distributing news. These routines of doing journalism and their subjectifications by the journalists form the second element of the dispositive. They are no less normalizing than the discourse, because through their practices of investigating, fact-checking, interviewing, writing, presenting, establishing objectivity etc.—by doing journalism—the journalists also define what journalism is. While the non-discursive practices of doing and teaching journalism are obviously not the same thing, they are nonetheless closely connected because journalism educators and practitioners share the same conceptions about journalistic professional roles, journalism teachers have for the most part practical experience in journalism and journalistic skills are usually taught by practical example (cp. Drok Citation2019).

Routines of doing and teaching journalism are rarely reflected upon because they seem “natural” and are incorporated by those who identify themselves as journalists and/or journalism teachers. However, as the intensified discourse of the last twenty years indicates, they are made explicit and reflected upon when faced with an “urgent need” such as the disruptive effects of digital media technologies and their use.

Materializations or objectifications are the visible outcome of both discursive and non-discursive practices (Bührmann Citation2010, 26). Just as non-discursive practices are informed by discourse and discourses are updated and reinforced through non-discursive practices, the objectifications are “objects” only in so far as they carry discursively created meaning and transmit meaning back into the discursive and non-discursive practices (Jäger and Maier Citation2016, 112 and 115).

The most obvious objectifications as results of discursive and non-discursive practices are the journalistic products whose formats and production routines react to the expansion of the internet and social media (Nielsen Citation2016, 61). Less obvious objectifications, however, include spatial developments such as newsroom convergence, which is not only a product of economic constraints and new technical possibilities, but also an expression of certain ideas about how journalism works—for example in the design of office spaces in which (editorial) groups can be reassembled as required (Usher Citation2014). Likewise, journalism also manifests itself in media and journalism-related laws and internal professional regulations (such as press codes), as well as the training standards and curricula of journalism schools, which are the object of this research.

Literature Review: Journalism Education for the Twenty-First Century

The dual pillars of teaching of journalism and teaching about journalism have long characterized journalism education. While the teaching of journalism comprises the skills necessary for news production, the teaching about journalism contextualizes those skills and gives them meaning (Bjørnsen, Hovden, and Ottosen Citation2007, 385). Following Cheetham and Chivers (Citation2005), competencies are defined as cognitive competence (“know-why”), functional competence (the ability “to do”), personal/behavioural competence and values/ethical competence. In journalism these correspond with professional knowledge, journalistic skills, personal capabilities and general as well as professional values that a journalist needs to possess for an effective job performance (Schorr Citation2003, 28; Bjørnsen, Hovden, and Ottosen Citation2007, 384; Guo and Volz Citation2021). These competencies are included in programmatic papers such as the UNESCO “Model curriculum for journalism education” (Banda Citation2013) and the “Tartu Declaration” of the European Journalism Training Association (EJTA Citation2020). Within their specific cultural settings, journalism programs worldwide address the societal functions of journalism and teach practical skills of newsgathering, selection and presentation as well as knowledge about media systems and communication processes.

The Journalism Education Discourse

When after the turn of the century the digital transformation of journalism accelerated and the traditional business model of media organizations faced a widespread crisis, the debate about the relative significance of skills, knowledge and critical reflection became more urgent. The number of desirable competencies has increased over the last decade to include e.g., entrepreneurship, intellectual property rights, understanding data and algorithms, curating content and managing social networks (Berger and Foote Citation2017, 249). This poses a considerable challenge to curriculum developers, who not only have to choose the most relevant content in the face of limited resources but also have to keep up with the speed of digital transformation and anticipate medium-term developments to meet the demands of the labor market (Marcus Citation2014).

The relationship between journalism education and the media industry has often been uneasy because it touches on questions of mutual independence and collaboration, innovation and quality standards. However, the recent trend towards more collaboration between education institutions and media organizations can be beneficial for both sides (Berger and Foote Citation2017, 253), for example in developing and testing innovative products in student news labs (Spillman, Kuban, and Smith Citation2017, 104). But serving the media industry interests and serving the public is not always the same thing and education has to negotiate its place between the two (Mensing Citation2010, 514), upholding its emphasis on critical reflection and adequate quality standards as means to fulfill journalism’s democratic function (cp. Banda Citation2013; EJTA Citation2020).

In the face of strategic disinformation, fake news, political micro-targeting and a loss of trust in legacy media in parts of the public, many educators feel that fact-checking skills, media and data literacy, knowledge about media ethics and accountability become ever more important competencies for journalism students (Nordenstreng Citation2009), and that the future tasks of journalists lie in a slower and more sustainable journalism (Drok Citation2019, 42–44).

Lastly, both journalism educators and practitioners call for innovative teaching methods in order to meet the growing competency demands on young journalists and to maintain societal relevance (cp. Finberg Citation2013; Folkerts Citation2014). For example, the widely debated “teaching hospital” model promotes classroom innovation, entrepreneurship and collaborations between journalism schools and media industry (Anderson et al. Citation2011). Innovative teaching methods include hybrid learning, immersive learning, experiential learning and community-oriented learning among others (for a detailed description cp. Spillman, Kuban, and Smith Citation2017, 200–203).

Briefly summing up the internationally discernible tendencies in the discourse on journalism education (cp. Deuze Citation2006; Nordenstreng Citation2009; Mensing Citation2010; Anderson et al. Citation2011; Pavlik Citation2013; Banda Citation2013; Goodman and Steyn Citation2017; Drok Citation2019; Nowak Citation2019; EJTA Citation2020 among others), it is widely assumed that the following issues will become more important for future journalists:

entrepreneurial skills and knowledge;

data skills and knowledge;

a deeper understanding and critical reflection of media technologies and communication processes in an environment, which is increasingly characterized by immersion in ubiquitous media rather than ritualized interaction with media and in which the dynamics of fragmentation and networking have changed;

understanding the role of journalism in society, communicating social values and responsibility, and integrating oneself as a journalist into a community;

networking, collaboration and team orientation;

innovation, creativity and experience-based learning.

The following issues are assumed to lose importance:

to train for the “market”, i.e., for the needs of media companies which have less and less demand for journalists;

to provide all conceivable skills—especially in the technological field—because, in view of the large number and accelerated development of new technologies, this can no longer be achieved by training and, in view of the short-lived nature of some technological trends and digital platforms, it hardly seems appropriate.

Journalism Education Practice

While trends in education discourse are easily identifiable through position papers, recommendations and statements by educators and researchers, empirical studies on actual teaching practices are often limited to single topics such as teaching entrepreneurship or data journalism or to best practice case studies (e.g., Casero-Ripollés, Izquierdo-Castillo, and Doménech-Fabregat Citation2016; Splendore et al. Citation2016; Treadwell et al. Citation2016). Studies in this field tend to emphasize the positive effects of immersive, experiential and community-oriented learning and of collaborative efforts between education institutions and media organizations. However, regarding the use of innovative teaching methods in the United States a recent study of keywords in course descriptions found that “well-established words such as ‘capstone’ and ‘practicum’ are still frequently used to describe educational experiences in journalism. Absent, for the most part, are terms such as ‘entrepreneurial’, ‘collaborative’, ‘experiential’, and ‘innovative’—all of which indicate, at least via course catalogs, that schools are not heeding the call for change from top journalism observers.” (Spillman, Kuban, and Smith Citation2017, 207) Studies from European countries show a similar gap between what is believed to be important tasks for journalism education and the actual teaching practice (Bettels-Schwabbauer et al. Citation2018; Drok Citation2019).

In addition, teaching journalism has always been concerned with finding the right balance between “theory” and “practice”—or between knowledge and skills—sometimes flanked by questions about whether academics or professionals make better journalism teachers (Folkerts Citation2014, 275–278). Findings from surveys suggest that the overall opinion of both journalists and journalism educators is that a reflective practice needs knowledge. Yet there is no definite answer on the exact nature of this relationship and the long-standing debate continues (e.g., Greenberg Citation2007; Hirst Citation2010; Finberg Citation2013).

Objectifications of Journalism Education

Journalism programs and curricula are the concrete manifestations of education discourse and practice. Several studies research accreditation and evaluation processes (Blom, Bowe, and Lucinda D. Citation2019; Nowak Citation2019) or measure the learning outcomes of programs through surveys among journalism students (e.g., Seamon Citation2010; Gossel Citation2015). Content analyses of curricula have mostly been carried out on a national level, for example in Australia (Adams and Duffield Citation2006), the United States (Lowrey, Becker, and Vlad Citation2007), Korea (Kang Citation2010), Flanders (Opgenhaffen, d’Haenens, and Corten Citation2013) and Russia (Vartanova and Lukina Citation2017). Comparisons are an exception (Cervi, Simelio, and Tejedor Calvo Citation2020). The studies collected data about aims and structure, competencies/learning outcomes, course topics, skills for different media platforms and/or the importance of media industry demands for curriculum development. While some authors point out the diversity of degrees on offer (e.g., Adams and Duffield Citation2006), others note a discrepancy between the topics of journalism education and profession (e.g., Opgenhaffen, d’Haenens, and Corten Citation2013).

Education discourse, non-discursive practices and objectifications are inextricably interwoven, influencing and reflecting on each other. One aim of the study was to find out how journalism educators relate to what has been identified as trends in journalism education discourse in the literature review. The first research question therefore consists of two parts:

RQ 1.1: What do journalism educators consider as important characteristics of an adequate journalism education?

RQ 1.2: In how far do their opinions reflect the international journalism education discourse?

Because the digital transformation of journalism is a fast and in many ways uncertain process, journalism educators are faced with the dual challenges of having to keep up with technological developments and changing media platforms and having to select from a growing number of potentially relevant skills and knowledge. Thus, the practices of program development and implementation are the focus of the following research questions:

RQ 2.1: How do journalism educators receive impulses for new curriculum content?

RQ 2.2: How do journalism educators select content for courses and modules?

In addition, innovative teaching methods have repeatedly been emphasized as a way to strengthen the “digital first” classroom (cp. Lynch Citation2015). With regard to the didactic practices of journalism education and their potential for innovation, this study asks:

RQ 3.1: What do journalism educators consider as good practice examples of journalism-related courses?

RQ 3.2: How innovative are the teaching methods the journalism educators describe?

The introduction of new content into journalism education is an ongoing process. Within the theoretical framework proposed in section two, journalism-related curricula are viewed as objectifications of both discourses and practices. Therefore, the final set of research questions is concerned with how some of the cornerstones of journalism education discourse and practice manifest themselves in course programs.

As discussed in the literature review, journalism education differentiates between knowledge, skills, personal and ethical competencies as possible learning outcomes. Their relative importance is the aim of RQ 4.1:

RQ 4.1: Which competencies are taught in the education and training institutions?

The past two decades have seen the rise of social media, platform convergence and cross media production. Against this background, the next research question addresses preferences for the teaching of journalistic and technological skills for different types of media:

RQ 4.2: On which type of media does the teaching of skills focus?

Moving from the teaching of competencies to the content of the individual courses, the following research question looks at the choices, which have been made about classroom topics:

RQ 4.3: What are the most frequent course topics?

The final two questions, which take up themes relevant to the journalism education discourse, are limited to those parts of the curricula, which are explicitly labeled as journalism classes: With regard to the omnipresence of digital media in news production and consumption, it seems important to learn how frequently digital competencies, i.e., knowledge about and specific skills and values for online and social media, are taught in connection to journalism:

RQ 4.4: How often are online and social media made a subject of journalism classes?

The last question in this set refers to the fact that journalism education has a long tradition of debating the relation between “theory” and “practice”. In addition, a long-standing demand of journalism education has been that practical skills and knowledge ought to be applied in class, e.g., in student newsrooms. Thus, this question is aimed at whether journalism courses are indeed more application-oriented than other courses:

RQ 4.5: How application-oriented are journalism classes?

While guided interviews with journalism educators were used to answer the first three sets of research questions, the fourth set of research questions was answered through a content analysis of course programs.

Methods

In Austria journalism education was long characterized by a predominance of training on the job and a very limited number of formalized non-academic programs. In academia, communication studies were offered at three universities. The educational market has expanded since the 1990s after a reform of the education system, which introduced private universities and universities of applied sciences (Dorer, Götzenbrucker, and Hummel Citation2010). At the same time, the number of non-academic institutions (backed by the state, federal governments, political and private interest groups or the churches) started to grow as well. Since the 2000s the education landscape has become more decentralized and diversified, and today it offers a wide range of programs with varying lengths, target groups and thematic focus.

Sample

This comprehensive study is based on a total of sixty-seven programs offered by thirty-one different institutions and ranging from Bachelor and Master studies to advanced training with theme-oriented workshops. Because of the differences in structure between a day-long workshop and a semester-long lecture (which roughly translates into three workdays plus self-teaching elements), results for universities, universities of applied sciences and advanced training institutions are presented separately throughout the results section. Despite their obvious differences in structure, they are, however, comparable in their main focus on certain competencies, topics or type of media skills.

The sample includes thirty-six basic and advanced training programs for journalists from all non-academic training institutions and—as a case example—four major community media. With regard to the universities and universities of applied sciences, a broader approach was adopted, because Austria does not have schools of journalism as such. At the universities, journalism classes and modules are offered under the larger roof of communication studies. At the universities of applied sciences, journalism and communication classes or modules are often a part of interdisciplinary programs and combined with e.g., computer sciences or economics. In both cases all available Bachelor, Master and certified programs were selected for the sample (fifteen programs at universities and sixteen programs at universities of applied sciences).

Empirically, the study followed a two-tier approach, combining a quantitative analysis of curricula and semi-structured interviews with curriculum developers and program directors. The quantitative content analysis was based on the online descriptions of both the programs (n=67) and the individual courses available between September 2018 and August 2019 (n=1818). The qualitative semi-structured interviews with twenty-nine program representatives in leading positions were conducted in spring and summer 2019. All interview partners were in leading positions as curriculum developers, program directors and executives. In the interviews, they took a double role: they were research subjects when they answered questions about their own institutions (e.g., about the specifics of the curriculum and curriculum management) and experts when they answered questions about the wider field of journalism education (e.g., its evolution, aims and challenges).

Interviews

In answer to RQ 1.1 and RQ 1.2 the key topics of the education discourse were addressed in the interviews. Interview partners were asked about the most important skills and knowledge an adequate journalism education should teach; about the relevance of teaching new—esp. digital—skills compared to the teaching of basics such as research, storytelling etc.; the relevance of critical reflection and journalistic values in the classroom; journalism education’s role with regard to journalism practice and the industry; about what they consider as the core of a good journalism education; and about the challenges of the rapid evolution of digital media.

RQ 2.1 and RQ 2.2 concerning the practices of selecting course content and finding impulses for new content were asked more or less directly with follow-up questions to explain the points in depth or to describe examples regarding e.g., the implementation of new content, best practices of innovative teaching methods or unsuccessful developments.

To answer RQ 3.1 the interview partners were first asked to describe examples of good practice courses from their programs. Follow-up questions explored the teaching methods in detail and asked about experiences with other methods. Only after that were the interview partners asked about innovative teaching methods they had not previously mentioned (RQ 3.2). Depending on the answers to the previous questions these would include e.g., inverted classroom, design thinking, peer group learning and community- or service-oriented learning. A considerable number of interview partners had not heard of such methods before and asked for an explanation.

Other than that and because all interview partners are experts involved in the planning and implementation of journalism curricula, very few explanatory remarks by the interviewers were needed. The interviews were carried out by two interviewers who had undergone a thorough schooling in the interview guide. The interviews lasted between about forty and ninety minutes, with most interviews around sixty minutes. With the exception of one video call due to scheduling problems, all interviews were conducted face-to-face. All interviews were transcribed literally and the transcripts were analysed in MaxQDA, employing qualitative content analysis (Mayring Citation2014).

Content Analysis

Competencies (RQ 4.1): This study uses a detailed definition of competencies, based on the analytical grid of Gossel (Citation2015), which defined competencies both theoretically—using the model of competencies developed by Nowak (Citation2007) on the basis of an extensive literature review – and empirically through a list of course contents. Professional knowledge (“Fachkompetenz”) includes both theoretical and factual knowledge about e.g., social theory, media and communication law or journalism cultures. Professional skills (“Handlungskompetenz”) refer to the use of methods, which enable a person to actually work in the media, e.g., news research and selection, storytelling, presentation techniques or cross media production. Media technology skills (“Technikkompetenz”), by contrast, are focused on skills necessary for handling media hardware and software, e.g., camera training, video production or data visualization. The type of specialized knowledge necessary to work in various thematic fields like politics or sports journalism is referred to as department knowledge (“Sachkompetenz”). Entrepreneurial knowledge (“unternehmerische Kompetenz”) includes knowledge about how to set up a business, about self-marketing and the necessary background in both economics and law. Basic skills (“Basiskompetenzen”) include skills for communication, presentation, creative processes, negotiation and team building.

Two modifications from Gossel (Citation2015, 5) were made: Because of the crucial importance of ethics and values and the ongoing debate about journalism quality, media ethics were taken from “professional knowledge” and orientation towards values and responsibility as well as analytical and reflective skills were taken from “basic skills” to form a separate competency social orientation. Following Weischenberg’s (Citation1990) definition, social orientation thus relates to “critical awareness of the professional role, critical reflection of profession tasks and autonomy awareness” (Schorr Citation2003, 28).

Lastly, this set of journalism-related competencies was expanded for the present study to cover the interdisciplinary curricula of universities of applied sciences. Additional competencies, which are not directly related to journalism, focus on knowledge and skills in information technology as well as management and economics. They also include other knowledge from scientific fields like political and social science or law and other skills like foreign languages, drawing or theater directing.

Skills for different types of media (RQ 4.2): professional and technological skills for different type of media include production for print, homepages and blogs (or unspecified; summarized as “text”), social media, video and audio production, photography, animation and multimedia as well as specific courses for cross media production.

Course topics (RQ 4.3) were modeled after Gossel’s (Citation2015) description of course contents and finalized after a discussion of their applicability and several rounds of testing. The main topic was coded according to each course’s title. In addition, up to five further topics were coded based on the course descriptions. These, however, did not substantially change the ranking of the prevalent topics and are not included in the results section.

Online and social media orientation of journalism classes (RQ 4.4): Courses belonging to the category of online and social media orientation explicitly put phenomena, knowledge and/or skills of the digital age at the heart of their course descriptions. In order to be classified as journalism course, the description had to identify the subject explicitly and by name as journalism. While it has to be acknowledged that this leaves out topics that are of potential interest to journalists, the rationale was to filter those courses that directly link online and social media with journalism. These cover a broad range of topics from e.g., social media reporting to fake news to web programming for journalists.

Application-orientation (RQ 4.5): Courses were categorized as application-oriented if the description explicitly mentioned practical experience, if a mandatory practical assignment completed the course and/or—due to the specifics of the Austrian education system—if the course was held by an external lecturer with a background in journalism.

The coding was conducted by two independent coders. Several rounds of pre-testing were necessary for the final definition of each coding rule because due to the wide range of institutions the depth of information in the course descriptions varied. During the development phase, intercoder reliability was repeatedly tested informally to identify borderline cases and to ensure applicability to a variety of institutions and courses. In order to establish intercoder reliability for the final version of the codebook, the two coders were trained to code 190 randomly drawn courses (10.45% of the sample).

Reliability coefficients (Krippendorff's alpha) were above 0.7 for “course topics” and “application-orientation” and above 0.8 for the other variables. Krippendorff's alpha should ideally be above 0.8, but preliminary conclusions can also be drawn from variables with values in the range of 0.667–0.80 (Krippendorff Citation2004, 241).

Results of the Guided Interviews with Representatives from Education Programs

RQ 1.1 and 1.2: Perspectives on Journalism Education and Relation to International Discourse

The first aim of the interviews was to find out how the stakeholders’ perspectives on journalism training and education relate to the international discourse about an adequate journalism education for the digital age. Overall, the stakeholders of education institutions in Austria reflect current positions identified in the literature review. The interviews show that ethical awareness, responsibility and critical reflection are considered as the most important attributes for young journalists, and one major goal of any journalism training and education should be to strengthen awareness for journalistic responsibility and quality. While the emphasis on teaching of values in journalism education discourse is hardly new, in the present day’s context it also reflects the unease about targeted disinformation, fake news, echo chambers and loss of trust in established media, which were frequently mentioned during the interviews.

Accordingly, the core content of training should consist of news research and fact checking, storytelling, knowledge of the media system etc. and not primarily of skills for dealing with new technological tools. In the opinion of the interviewees, mastering technology is of little use if it cannot be used to tell stories.

The speed of technological development is generally seen as a major challenge of digitalization. In the eyes of the interview partners the discourse and practices of journalism combine in a constant demand for new tools, the associated teaching of new technical skills and a new “mind set” (cp. Nordenstreng Citation2009, 514; Anderson et al. Citation2011, 2). The overall increase in the number of relevant skills is seen as an excessive demand on journalists and as a problem for the quality of reporting. Many curriculum developers described this as the biggest challenge to education because limited resources force them to make choices about which developments in journalism practice need to be addressed in the classroom.

Notably, some interview partners were sceptical about following developments in journalism without reflecting its consequences for both the profession and society. They felt that a certain degree of independence is needed in their relationship with the media industry and that education ought to do more than just aim at the labor market. Despite such considerations, the industry’s and students’ demand for “new” skills—particularly in multiple platform publishing, data journalism and entrepreneurialism—is widely acknowledged, which fits in with studies from other European countries (cp. Bettels-Schwabbauer et al. Citation2018, 90). A number of interview partners addressed the difficulty of balancing out such demands with their financial and technological resources and the lack of experienced teachers. Thus, programs often have difficulties to respond to developments in journalism as fast as they would like. In this context many interview partners also remarked on the effects of digital transformation on media organizations and their newsroom staff. The common opinion appears to be that declining resources are often an impediment for in-depth workshops and current updates of personal skills. This impression is backed by an explorative study (n=152), according to which about thirty percent of the Austrian journalists attend one course a year, while about seventeen percent do not attend any further education courses at all. The largest obstacles by far are the lack of personal financial resources, time and the companies’ willingness to pay training fees (Kaltenbrunner and Luef Citation2015).

RQ 2.1 and 2.2: Practices of Program Development and Implementation

Understanding and communicating transformation processes and recognizing which changes in journalism are really important, are central tasks of curriculum development in the present age. Therefore, the second aim of the interviews was to gain deeper insights into the stakeholders’ practices of selecting and implementing content.

For the selection of course content, most of the interviewees trust in the regular exchange with professional journalists. On the one hand, this is obvious and sensible, since in this way developments in the newsrooms are directly reflected in the classroom. However, it also bears the danger of simply continuing to update the tried and tested non-discursive practices. Alternative possibilities such as networking with other educational institutions, attending relevant conferences, market analyses and research in scientific publications and industry magazines are mentioned much less frequently as opportunities to recognize developments and gain ideas for new content. Likewise, few stakeholders mentioned the need to use scientific data or debates to anticipate the journalism five or ten years from now.

The implementation of content was similar in all institutions with a fixed curriculum structure. New and innovative topics such as mobile reporting or Instagram journalism are tried out in the more flexible courses or modules, while basic courses and modules are reserved for what is considered as core content of journalism education.

RQ 3.1 and 3.2: Innovative Potential of Teaching Methods

One place where non-discursive practices of journalism are reproduced and changed is the classroom. Here they are also linked to specific teaching practices, notably a strong orientation towards experiential learning (Folkerts Citation2014). Thus journalism education practice has traditionally maintained links with journalism practice outside the classroom through student media outlets, the hiring of journalism practitioners as teachers, and didactic methods that actively engage students in news production and give them feedback.

In the interviews, practical learning on concrete projects, framed by input and feedback from the teachers, was predominantly recommended as the best method of teaching journalism, and it has certainly proven its worth. Very few interview partners, however, spoke about developing and supporting the course participants' creativity, letting them experiment with products and try themselves out. The idea that education could also be a source of inspiration and shape both the media industry and the profession is still an exception in educational practice.

According to information from the interview partners, innovative learning and teaching methods are not widely spread. While the need for such approaches is often repeated in education discourse (e.g., Pavlik Citation2013; Spillman, Kuban, and Smith Citation2017), methods such as inverted classroom, peer group learning, community-oriented learning or design thinking are only occasionally known and/or applied. This is probably related to a lack of didactic training for teachers. Such training is only carried out in the higher education sector and limited to occasional courses which are neither compulsory nor in most cases open for external lecturers.

Results of the Quantitative Content Analysis

RQ 4.1: Competencies (n=1818)

The teaching of competencies in journalism, media and communication is based on three pillars—professional knowledge, professional skills and media technology skills—and thus reflects discourses on journalism education and training. It also reflects the broader educational practice in Austria and corresponds with the educational aims of the different institutions (cp. ).

Table 1. Media-, communication- and journalism-related competencies taught in individual courses of various types of institutions (n=1818, multiple codings).

Thus universities put a strong emphasis on professional knowledge (67.3%), while non-academic institutions focus on professional skills (50.3%). Universities of applied sciences are more evenly balanced between professional knowledge, professional skills and media technology skills. They also teach a more varied set of competencies due to their interdisciplinary approach.

The results also show that entrepreneurial knowledge and social orientation—as key learning outcomes of a course—are marginalized in all types of institutions. In other words, what is deemed important in the educational discourse and is recognized as such by the interview partners—who are responsible for the content of programs—does not necessarily show in educational practice.

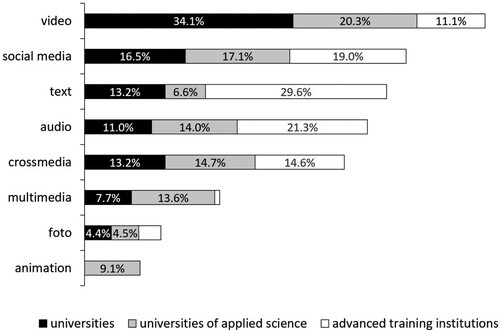

RQ 4.2: Type of Media Skills (n=630)

Journalism for different media involves a different set of communication and technology skills. The teaching of professional and technological skills for journalists therefore reflects what is considered useful for the journalism practice of the day. In the media skills classes—ranked by their total number—video production is closely followed by production for social media and text production either for print, homepages or unspecified (cp. ).

Yet again, differences can be found between the types of education institutions, where universities tend to focus on video production and advanced training institutions emphasize text production skills. The latter can be explained by the technological and financial means of these training institutions and by their emphasis on what is considered as the basis of journalism—namely “how to write”. Social media skills for the production of journalism on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram etc. are an important part of the media skills courses in all types of institutions.

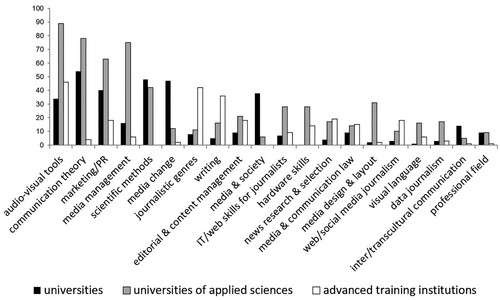

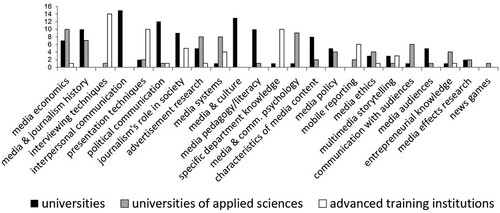

RQ 4.3: Course Topics (n=1445)

Topics of media and journalism-related courses were identified by their learning outcomes (n=1445). Therefore courses which have been coded as teaching additional competencies in IT, management and economics, languages etc. (n=373) are not included in the results.

With reference to what is deemed important in both international discourse and the interview part of this research, it is obvious that some topics are better implemented than others. Coded by title and sorted by their over-all absolute number, the twenty most frequent topics are led by skills for audio-visual tools, communication theory and marketing (cp. ).

While both various skills for digital media and journalism management show in the top twenty content, that is mostly due to the universities of applied sciences. At the far end of the list of twenty-three further topics for courses are some, which feature heavily in both scientific research on journalism and the discourse on journalism education (usually because they are considered as new and/or important phenomena of journalism in the digital age). These include e.g., entrepreneurial skills and knowledge, skills for mobile reporting, multiplatform and multimedia storytelling as well as knowledge about audience behavior and skills for communication with audiences (cp. ).

It is assumed that the explanation can be found in the relationship between journalism practice and educational practice: While journalism is evolving fast, education tends to lag behind due to structural constrains, e.g., the implementation process for new course modules or the costs for new hard- and software.

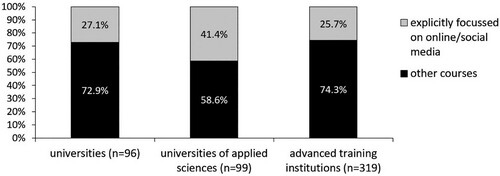

RQ 4.4: Online and Social Media Orientation of Journalism Classes (n=514)

On a very general level journalism training in Austria has answered the call of digitalisation. Digital media practice and discourses are integrated into the curricula by making related skills and knowledge one of the dominant topics. In fact they have become so ubiquitous that a number of programs explicitly carry the label “digital”, such as the master programs Digital Communication Leadership, Digital Journalism, Digital Media Production and Journalism and New Media at universities and university of applied sciences in Salzburg, Krems, St. Pölten and Vienna or certified programs like Digital Communication by the Austria Press Agency/APA Campus.

Between one quarter and almost one half of the courses which teach journalism (and not another media-related topic) center on online and social media issues in one way or another (cp. ). To these, the courses which make no explicit reference to online and social media in the course descriptions must be added (e.g., a course in cross media production is likely to include online and social media issues).

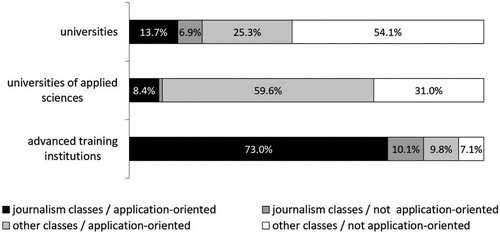

RQ 4.5: Application-orientation of Journalism Classes (n=1818)

Putting knowledge and skills to practice plays an important role in journalism education. The discourse on journalism education has long been concerned with the relationship between theory and practice, and although a proper “ratio” can certainly not be established, the value of experiential learning—preferably in combination with theory-based reflection—is commonly accepted (cp. Nordenstreng Citation2009, 516; Mensing Citation2010, 514–515; Folkerts Citation2014, 2382–41; Drok Citation2019, 5–6).

As can be expected, application-orientation is highest in advanced training institutions, where courses are in fact often workshops. It is lowest at the universities, all of which offer degrees in communication and thus include a broad range of “theoretical” knowledge (cp. ). In sum, however, the percentage of application-oriented courses—journalism classes and other combined—is high in all types of institutions, with 82.8% at the advanced training institutions, 68.0% at the universities of applied sciences and 39.0% at the universities. Journalism courses in particular are very clearly more often application-oriented than not.

Conclusion

Despite differences in the respective national educational landscapes, journalism training and education across Europe is facing similar challenges in view of digitalization and the changes in journalism that accompany it. The content analysis and the interviews with stakeholders from the various education and training institutions have shown that these challenges are largely perceived in Austria as well, although not all of them have (yet?) found their way into the curricula.

Most program directors and developers are aware of the topics of the international journalism education discourse. They see the need of keeping in touch with the developments of journalism in the digital age and tend to give the core competencies of research, fact-checking and storytelling precedence over specific media technology and platform skills. In response to “post-truth” and “alternative facts” they also emphasize the democratic function of journalism, the importance of professional standards and personal accountability. The practices of program development and teaching methods both tend towards the well-established, relying on input from professional journalists and on project-based learning and individual feedback, with little room for innovation. Journalism curricula as manifest objectifications of journalism education shape and are shaped by education discourses and non-discursive practices. Thus they are reflective of the digital transformation of journalism, and the integration of digital knowledge and skills in the curricula is wide-spread. Yet some topics are more frequently addressed than others—curricula are often particularly slow in adopting specific skills for e.g., mobile reporting, entrepreneurialism and data journalism.

In order to understand the discrepancy of what is deemed important in education discourse and what is actually happening in the education institutions, it is not enough to look at the interrelations of objectifications, discursive and non-discursive practices of journalism education. Indeed, what is happing in other parts of the dispositive of journalism provides a tentative explanation.

Programs and their curricula are limited by journalism discourse and practice because they rely to a large degree on professional journalists as teachers and because they have to meet the expectations of media industry and journalism students, as a number of interview partners noted. They are also limited by institutional constraints and forces outside of the dispositive of journalism such as the dispositive of (higher) education (cp. Gillies Citation2013), which sets the framework for universities with the Bologna Process, and the organizational dispositive of the media (cp. Altmeppen Citation2007), which is a dispatcher (“disponent”) of resources. Together these forces place a major constraint on training and education, limiting the available temporal and financial resources.

Journalism is going through a “moment of mind-blowing uncertainty” (Franklin Citation2014, 488) and it is no coincidence that the uncertainties of the past decade about the future societal role, economic basis, professional self-perception and work processes of journalism fall together with an intensified interest in journalism education. Books, research articles, conferences and countless informal discussions stress the point that a sustainable journalism education makes an important contribution to ensure journalistic quality. Just as the dispositive of journalism as a whole is tasked with responding to the “urgent need” of digital transformation, so is journalism education.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams, Debra A., and Lee R. Duffield. 2006. “Profiles of Journalism Education: What Students are Being Offered in Australia.” Proceedings journalism education association, annual conference, Griffith University, Queensland; https://eprints.qut.edu.au/3918/1/3918_1.pdf.

- Altmeppen, Klaus-Dieter. 2007. “Das Organisationsdispositiv des Journalismus.” In Journalismustheorie: Next Generation. Soziologische Grundlegung und Theoretische Innovation, edited by Klaus-Dieter Altmeppen, Thomas Hanitzsch, and Carsten Schlüter, 281–302. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Anderson, C. W., Tom Glaisyer, Jason Smith, and Marika Rothfeld. 2011. Shaping 21st Century Journalism. Leveraging a “Teaching Hospital Model” in Journalism Education, https://www.academia.edu/1220873/Shaping_21st_Century_Journalism_Leveraging_a_Teaching_Hospital_Model_in_Journalism_Education.

- Banda, Fackson. ed. 2013. Model Curricula for Journalism Education. A Compendium of New Syllabi. Paris: Unesco. http://www.unesco.org/new/en/communication-and-information/resources/publications-and-communication-materials/publications/full-list/model-curricula-for-journalism-education-a-compendium-of-new-syllabi/.

- Baudry, Jean-Louis. 1975. “Ideological Effects of the Basic Cinematographic Apparatus.” Film Quarterly 28 (2): 39–47. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1211632.

- Berger, Guy, and Joe Foote. , 2017. “Taking Stock of Contemporary Journalism Education: The End of the Classroom as We Know It.” In Global Journalism Education: Challenges and Innovations, edited by Robyn S. Goodman and Elaine Steyn, 245–266. Austin/TX: Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas. https://journalismcourses.org/ebook/global-journalism-education-challenges-and-innovations/.

- Bettels-Schwabbauer, Tina, Nadia Leihs, Gábor Polyák, Annamária Torbó, Ana Pinto Martinho, Miguel Crespo, and Raluca Radu. 2018. Newsreel. New Skills for the Next Generation of Journalists. Erasmus+ Research Report. https://newsreel.pte.hu/sites/newsreel.pte.hu/files/REPORT/new_skills_for_the_next_generation_of_journalists_-_research_report.pdf.

- Bjørnsen, Gunn, Jan Fredrik Hovden, and Rune Ottosen. 2007. “Journalists in the Making.” Journalism Practice 1 (3): 383–403. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17512780701505085.

- Blom, Robin, Brian J. Bowe, and Davenport Lucinda D. 2019. “Accrediting Council on Education in Journalism and Mass Communications Accreditation: Quality or Compliance?” Journalism Studies 20 (10): 1458–1471. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2018.1526641.

- Bührmann, Andrea D. 2010. “The Death of the Subject and its Sociological Rebirth as Subjectification: Future Research Perspectives.” In Self-Controlling/Self-Regulation or Self-Caring -the Sociology of the Subject in 21st Century, edited by Andrea D. Bührmann, and Stefanie Ernst, 14–35. London: Cambridge Scholar Press.

- Bührmann, Andrea D., and Werner Schneider. eds. 2008. Vom Diskurs zum Dispositiv. Eine Einführung in die Dispositivanalyse. Bielefeld: Transcript.

- Bussolini, Jeffrey. 2010. “What is a Dispositive?” Foucault Studies 10: 85–107. doi:https://doi.org/10.22439/fs.v0i10.3120.

- Casero-Ripollés, Andreu, Jessica Izquierdo-Castillo, and Hugo Doménech-Fabregat. 2016. “The Journalists of the Future Meet Entrepreneurial Journalism.” Journalism Practice 10 (2): 286–303. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2015.1123108.

- Cervi, Laura, Núria Simelio, and Santiago Tejedor Calvo. 2020. “Analysis of Journalism and Communication Studies in Europe’s Top Ranked Universities: Competencies, Aims and Courses.” Journalism Practice, doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2020.1762505.

- Cheetham, Graham, and Geoff Chivers. 2005. Professions, Competence and Informal Learning. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Couch, Danielle, Gil-Soo Han, Priscilla Robinson, and Paul Komesaroff. 2015. “Public Health Surveillance and the Media: A Dyad of Panoptic and Synoptic Social Control.” Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine 3 (1): 128–141. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21642850.2015.1049539.

- Deuze, Mark. 2006. “Global Journalism Education: A Conceptual Approach.” Journalism Studies 7 (1): 19–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700500450293.

- Dorer, Johanna. 2008. “Das Internet und die Genealogie des Kommunikationsdispositivs. Ein medientheoretischer Ansatz nach Foucault.” In Kultur - Medien – Macht, edited by Andreas Hepp, and Rainer Winter, 353–365. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Dorer, Johanna, Gerit Götzenbrucker, and Roman Hummel. 2010. “The Austrian Journalism Education Landscape.” In European Journalism Education, edited by Georgios Terzis, 81–92. Bristol: Intellect.

- Drok, Nico. 2019. Journalistic Roles, Values and Qualifications in the 21th Century. How European journalism educators view the future of a profession in transition. Windesheim; Zwolle: EJTA. https://www.ejta.eu/sites/ejta.eu/files/2019%2004%2012%20DROK%20Report%20RVQ.pdf.

- EJTA. 2020. Tartu Declaration 2020, https://www.ejta.eu/tartu-declaration-2020.

- Finberg, Howard. 2013. Rethinking Journalism Education: A Call for Innovation. St. Petersburg/FL: Poynter Institute. http://www.newsu.org/course_files/StateOfJournalismEducation2013.Pdf.

- Folkerts, Jean. 2014. “History of Journalism Education.” Journalism & Communication Monographs 16 (4): 227–299. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1522637914541379.

- Foucault, Michel. 1980. “The Confession of the Flesh. A Conversation of Alain Grosrichard, Gerard Wajeman, Jaques-Alain Miller, Guy Le Gaufey, Dominique Celas, Gerard Miller, Catherine Millot, Jocelyne Livi and Judith Miller.” In Power/Knowledge. Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972-1977, edited by Colin Gordon, 194–228. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Franklin, Bob. 2014. “The Future of Journalism.” Journalism Studies 15 (5): 481–499. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2014.930254.

- Gillies, Donald. 2013. Educational Leadership and Michel Foucault: Critical Studies in Educational Leadership, Management and Administration. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Goodman, Robyn S., and Elaine Steyn, eds. 2017. Global Journalism Education: Challenges and Innovations. Austin/TX: Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas. https://journalismcourses.org/ebook/global-journalism-education-challenges-and-innovations/.

- Gossel, Britta M. 2015. “Quo Vadis Journalistenausbildung? Teil 2: Beschreibung, Bewertung und Verbesserung der Journalistischen Ausbildung.” In Diskussionspapiere Menschen – Märkte – Medien – Management, edited by Andreas Will. https://www.db-thueringen.de/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/dbt_derivate_00032011/DMMMM-2015_02.pdf.

- Greenberg, Susan. 2007. “Theory and Practice in Journalism Education.” Journal of Media Practice 8 (3): 289–303.

- Guo, Lei, and Yong Volz. 2021. “Toward a New Conceptualization of Journalistic Competency: An Analysis of U.S. Broadcasting Job Announcements.” Journalism & Mass Communication Educator 76 (1): 91–110. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1077695820925306.

- Hickethier, Knut. 1995. “Dispositiv Fernsehen. Skizze Eines Modells.” ” Montage/AV 4 (1): 63–84.

- Hirst, Martin. 2010. “Journalism Education ‘Down Under’.” Journalism Studies 11 (1): 83–98. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470903217345.

- Jäger, Siegfried. 2001. “Discourse and Knowledge. Theoretical and Methodological Aspects of a Critical Discourse and Dispositive Analysis.” In Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis, edited by Ruth Wodak, and Michael Meyer, 32–62. Los Angeles: Sage, 1st edition.

- Jäger, Siegfried, and Florentine Maier. 2016. “Analysing Discourses and Dispositives: a Foucauldian Approach to Theory and Methodology.” In Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis, edited by Ruth Wodak, and Michael Meyer, 109–136. London: Sage Publications, 2nd edition.

- Kaltenbrunner, Andy, and Sonja Luef. 2015. GeneralistInnen vs. SpezialistInnen. Zur Veränderung von Berufsfeld und Qualifikationsbedarf im Journalismus. Studie des Medienhauses Wien, Forschungsbericht. https://www.rtr.at/de/ppf/Kurzbericht 2014/ MHW-Forschungsbericht_Ver%C3%A4nderung_von_Berufsfeld_und_Qualifikationsbedarf_im_Journalismus.pdf.

- Kang, Seok. 2010. “Communication Curricula at Universities in the Republic of Korea: Evolution and Challenges in the Digital age.” Asia Pacific Media Educator 20: 53–68.

- Keller, Reiner. 2018. The Sociology of Knowledge Approach to Discourse. Investigating the Politics of Knowledge and Meaning-Making. Abingdon; New York: Routledge.

- Krippendorff, Klaus. 2004. Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Laclau, Ernesto. 1980. “Populist Rupture and Discourse.” Screen Education 34: 87–93.

- Lowrey, Wilson, Lee B. Becker, and Tudor Vlad. 2007. Organizational Constraints on Curricular Adaptation in U.S. Journalism and Mass Communication Education. https://grady.uga.edu/coxcenter/Conference_Papers/Public_TCs/Lowrey%20Becker%20Vlad%20IAMCR%202011%20Merged.pdf.

- Lynch, Dianne. 2015. Above and Beyond. Looking at the Future of Journalism Education. Miami/FL: The Knight Foundation. https://knightfoundation.org/reports/above-and-beyond-looking-future-journalism-educati/.

- Marcus, Jon. 2014. “Rewriting J-School. How journalism schools are trying to connect classrooms to newsrooms.” Nieman Reports, Spring 2014, https://niemanreports.org/articles/rewriting-j-school/.

- Mayring, Philipp. 2014. Qualitative Content Analysis. Theoretical Foundation, Basic Procedures and Software Solution. Klagenfurt: SSOAR. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173.

- Mensing, Donica. 2010. “Rethinking (Again) the Future of Journalism Education.” Journalism Studies 11 (4): 511–523. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14616701003638376.

- Nielsen, Rasmus K. 2016. “The Business of News.” In The Sage Handbook of Digital Journalism, edited by Tamara Witschge, C. W. Anderson, David Domingo, and Alfred Hermida, 51–67. London: Sage.

- Nordenstreng, Kaarle. 2009. “Soul-searching at the Crossroads of European Journalism Education.” In European Journalism Education, edited by Georgios Terzis, 511–517. Bristol: Intellect.

- Nowak, Eva. 2007. Qualitätsmodell für die Journalistenausbildung. Kompetenzen, Ausbildungswege, Fachdidaktik. Dortmund: Dissertation. https://d-nb.info/997731125/34.

- Nowak, Eva. 2019. Accreditation and Assessment of Journalism Education in Europe. Qualitative Evaluation and Stakeholder Influence. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Opgenhaffen, Michaël, Leen d’Haenens, and Maarten Corten. 2013. “Journalistic Tools of the Trade in Flanders.”.” Journalism Practice 7 (2): 127–144. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2012.753208.

- Pavlik, John V. 2013. “A Vision for Transformative Leadership: Rethinking Journalism and Mass Communication Education for the Twenty-First Century.” Journalism & Mass Communication Educator 68 (3): 211–221. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1077695813499561.

- Romele, Alberto, Francesco Gallino, Camilla Emmenegger, and Daniele Gorgone. 2017. “Panopticism is not Enough: Social Media as Technologies of Voluntary Servitude.” Surveillance & Society 15 (2), doi:https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v15i2.6021.

- Schorr, Angela. 2003. “Communication Research and Media Science in Europe: Research and Academic Training at a Turning Point.” In Communication Research and Media Science in Europe: Perspectives for Research and Academic Training in Europe's Changing Media Reality, edited by Angela Schorr, William Campbell, and Michael Schenk, 3–56. Berlin; New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Seamon, Marc C. 2010. “Value of Accreditation: An Overview of Three Decades of Research Comparing Accredited and Unaccredited Journalism and Mass Communication Programs.” Journalism & Mass Communication Educator 65 (1): 9–20.

- Spillman, Mary, Adam J. Kuban, and Suzy J. Smith. 2017. “Words Du Jour: An Analysis of Traditional and Transitional Course Descriptors at Select J-Schools.” Journalism & Mass Communication Educator 72 (2): 198–211. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1077695816650118.

- Splendore, Sergio, Philip Di Salvo, Tobias Eberwein, Harmen Groenhart, Michael Kus, and Colin Porlezza. 2016. “Educational Strategies in Data Journalism: A Comparative Study of six European Countries.” Journalism 17 (1): 138–152.

- Steinmaurer, Thomas. 2016. Permanent vernetzt. Zur Theorie und Geschichte der Mediatisierung. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Treadwell, Greg, Tara Ross, Allan Lee, and Jeff Kelly Lowenstein. 2016. “A Numbers Game: two Case Studies in Teaching Data Journalism.” Journalism & Mass Communication Educator 71 (3): 297–308. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1077695816665215.

- Usher, Nikki. 2014. Moving the Newsroom: Post-Industrial News Spaces and Places. Report for the Tow Center for Digital Journalism. New York: Columbia University.

- Vartanova, Elena, and Marina Lukina. 2017. “Russian Journalism Education: Challenging Media Change and Educational Reform.” Journalism & Mass Communication Educator 72 (3): 274–284. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1077695817719137.

- Weischenberg, Siegfried. 1990. “Das 'Paradigma Journalistik': Zur kommunikationswissenschaftlichen Identifizierung der hochschulgebundenen Journalistenausbildung.” Publizistik 35 (1): 45–61.

- White, Michele. 2006. The Body and the Screen: Theories of Internet Spectatorship. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Zajc, Melita. 2015. “The Social Media Dispositive and Monetization of User-Generated Content.” The Information Society 31 (1): 61–67. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2015.977636.