ABSTRACT

The epistemic authority of journalism has undergone significant theorization and empirical investigations in past years. This article contributes to this growing body of scholarship by analyzing how collected images and videos are used as evidence in 14 visual video investigations by The New York Times. A visual discourse analysis following the Sociology of Knowledge Approach to Discourse (SKAD) is conducted to map out how an investigative way of seeing is established by coexisting discursive practices, including narrativization, coding schemes, highlighting techniques, and juxtaposition of video footage in split-screen mode. The article argues that these discursive practices serve as markers of authority which together facilitate a demonstration that recontextualizes collected visuals into evidence, reanimating them as external objects of knowledge that can be interrogated in epistemic struggles concerning the definition of controversial events.

Introduction

The killing of George Floyd, a Ukrainian commercial airplane engulfed in flames, Uyghurs forced to work in Chinese factories; all caught on video and used as evidence by The New York Times (NYT) to claim epistemic authority over how events transpired. Without these images of transgressions, our knowledge and certainty of these injustices would have been limited. In a world saturated with cameras and surveillance, visual information can be retrieved of people, places, and incidents that were unthinkable before the digital transformation of the media industry. Visuals captured by non-professionals sit at the heart of this epistemic shift and have been studied in relation to revolutions (Adami Citation2016), wars (Chouliaraki Citation2015; Mast and Hanegreefs Citation2015), nature disasters (Robinson Citation2009), and terror attacks (Allan Citation2014; Ibrahim Citation2014). Others have noted how verification practices (Brandtzaeg, Lüders, and Spangenberg Citation2016), gatekeeping models (Schwalbe, Silcock, and Candello Citation2015) and photojournalism (Greenwood and Thomas Citation2015) are changing as a consequence of citizen journalism and digital witnessing (Allan Citation2013; Mortensen Citation2014). However, how these transformations are affecting the different subdisciplines of journalism, including investigative reporting, is a topic that seems to be less covered by the literature.

This paper will explore how collected images and videos are reconstructed and used as evidence in online investigative journalism by studying the work of NYT’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Visual Investigations team (henceforth the Team). Their methods are inspired by how open-source material and user-generated content are used by scientists, investigators in law and human rights, and the intelligence community. Their reporting covers many different topics from police violence to extrajudicial killings and war crimes, but the one common thread is the visual, which is the main source of knowledge, the method of inquiry, and the primary mode of representation. Together with interdisciplinary organizations such as Bellingcat and Forensic Architecture (Dubberley, Koenig, and Murray Citation2020; Müller and Wiik Citation2021; Weizman Citation2017), the Team of NYT are part of an emerging field that Fuller and Weizman (Citation2021) have theorized as investigative aesthetics. Investigative aesthetics involves collecting, interpreting, and noticing unintentional evidence registered in visual, audio, or data files or the material composition of the environment. Collected artifacts are then reconstructed into visual stories where the artifacts’ correspondence with each other is highlighted, creating a poly-perspectival assemblage of truth-production (13–25). This paper aims to examine the epistemological and discursive foundation of this type of visual journalism; the forms of knowledge it produces, how it constructs its visual authority and where it intersects with a more traditional investigative epistemology (Ettema and Glasser Citation1985). The study deploys a visual discourse analysis inspired by The Sociology of Knowledge Approach to Discourse (SKAD) on 14 video investigations produced by the Team in 2020 to examine how images and videos are mobilized, narrativized, interlinked, juxtaposed, and (re)contextualized using different discursive practices to reconstruct them into external objects of knowledge that can be interrogated as evidence in epistemic contests.

I start by explicating how images and videos can be constructed into evidence through the establishment of a professional vision (Goodwin, Citation1994). I then trace the role of visuals in investigative journalism before discussing the epistemological tensions and aesthetic differences that reside in visuals captured by non-professionals and fixed cameras. Following a presentation of the study’s dataset, research question, and methodological approach, an in-depth analysis is conducted. Finally, I sum up the most important takeaways, addresses reservations towards my findings, and make suggestions for further research.

The Construction of Visual Evidence

To understand how images and videos are used as evidence, it is crucial to first address their uniqueness as artifacts. Historically, the notion that still- and moving images show and speak the truth stems from their correspondence to the real (Dufour and Delage Citation2015). This inherent indexicality is a prerequisite for the cultural status of visuals as truth-telling objects (Newton Citation2001). Visual meaning is derived from the layers of denotation and connotation. Denotation refers to the indexical bond with people, objects, events, and places represented, while connotation refers to everything that is culturally associated with what is represented, and how it is represented aesthetically (Barthes Citation1977). This has led scholars to argue that the authority of visuals does not reside in the artifacts themselves, but in the viewer, as an effect or response to the viewing context, suggesting that photographic truth is ambiguous (Phillips Citation2009; Sturken and Cartwright Citation2017; Zelizer Citation2005). Equally important as the image itself is how it is used in narratives and arguments and (re)contextualized by people, professions, and knowledge-producing fields (Bal Citation2003).

Still- and moving images are not the same and have different ways of creating their “truth effects” (Cubitt Citation2002). Whereas a photograph is polysemic and needs linguistic messages to anchor, relay, or contextualize its meaning, raw video has kinetic and chronemic qualities that function on their own. This is not to suggest that moving images are unaffected by discursive practices. Their meaning can be affixed by a voiceover, a caption, or a label, too. However, raw video has also temporal, technological, phenomenological, and semiological affordances that combined create an artifact with a narrative structure that on one level speaks for itself (Bock and Schneider Citation2017).

Although visuals are not objective artifacts, they have been mobilized as such since the dawn of photography. Drawing on Foucault (Citation1977), Tagg (Citation1999), and Sekula (Citation1986) have demonstrated how the photograph has been used to regulate social deviance by surveilling, archiving, and identifying criminals and other outcasts. From the state’s point of view, the photograph represented a powerful tool in their regimes of truth precisely because it appeared as incontestable evidence of the real. Yet, photographs and videos have a long and complicated history in the field of law. American judges in the second half of the nineteenth century grouped photographs alongside other visual representations, thereby giving them secondary status as illustrative evidence part of witness testimony, rather than recognizing them as independent proof (Mnookin Citation1998). This analogy backfired and brought into existence a new epistemic category that strengthened the evidentiary status of maps and diagrams which in turn paved way for a “culture of construction” in the courtroom: “Evidence was now something not only to be found but to be made” (66).

The fragility of visuals as forensic objects and their contingency on context were famously demonstrated in the 1992 Rodney King trial, a pivotal moment in the history of visual evidence (see Fiske Citation1996; Nichols Citation1995; Schwartz Citation2009). King, a black motorist, was pulled over for speeding and beaten by four white LAPD officers. The beating was filmed by George Holiday, a bystander, and used as evidence by both legal teams in court, albeit in opposing narratives and different formats. While the prosecutor played the tape in its entirety without offering an explicit interpretation, thus mistakenly entrusting only its denotative power, the defense decontextualized the tape by abstracting still images from it, cropping, printing, enlarging, and displaying them in front of the jury as well as freeze-framed on a monitor. Furthermore, they marked King’s body movements on the printouts, replayed segments, and summoned expert witnesses that gave testimonies that framed King’s behavior as aggressive and the policemen’s actions as routine responses to this aggressiveness. The defenses’ recontextualization of the tape convinced the jury that the beating was reasonable from a professional point of view.

Professional Vision

Goodwin (Citation1994) analyzes the King trial in tandem with an archaeological field excavation and identifies three discursive practices which he argues are key in building and contesting a professional vision: (1) coding schemes, (2) highlighting techniques, and (3) articulations and production of material representations. Coding schemes transform the world into categories and events that are relevant to the work of a profession. Highlighting techniques such as hand gestures, arrows, and drawn lines make some elements more salient than others. While material representations, or what Latour and Woolgar (Citation1986) call inscriptions, can “organize phenomena in ways that spoken language cannot – for example, by collecting records of a range of disparate events onto a single visible surface” (Goodwin, Citation1994, 611). Important inscriptions in the King trial were the printouts and the monitor. Inscriptions are often multi-layered and manufactured through many stages, forming what Latour calls cascades of inscriptions (Citation1986). Their effect, in addition to interlinking and recontextualizing different kinds of knowledge and thereby constricting the room for interpretation, is that each layered inscription strengthens the artifacts’ evidentiary weight:

Although in principle any interpretation can be opposed to any text or image, in practice this is far from the case: the cost of dissenting increases with (…) each new labeling, each new redrawing (…) Thus, one more inscription (…) to enhance contrast, (…) to decrease background (…) might be enough, all things being equal, to swing the balance of power and turn an incredible statement into a credible one (…). (18–19)

The Epistemology of Investigative Journalism

Investigative reporters seek to expose wrongdoings and transgressions in society that are unknown or hidden from the public. Consequently, their truth claims about events are often more comprehensive, controversial, and more moralistic than in other types of journalism (Ettema and Glasser Citation1998; Protess, Cook, and Doppelt Citation1991). Following Park (Citation1940) and Berger and Luckmann (Citation1966), Ettema and Glasser (Citation1985) were the first to sketch the epistemology of investigative journalism, studying how investigative reporters know what they know, and what counts as evidence within their context of justification. This approach to epistemology is sociological, not philosophical, and part of a strand of scholarship within journalism studies that focus on journalism’s different forms of knowledge, and how knowledge claims are articulated, implied and justified within news organizations and in news texts (Ekström and Westlund Citation2019a). The principle of the epistemology of investigative journalism is an ingrained skepticism towards the veracity of knowledge claims in general. Claims are usually cross-verified by checking their correspondence with each other, regardless of their origin and the circumstances surrounding their retrieval. This is different from “daily news journalism” where verification procedures are more random (Godler and Reich Citation2017). In running news coverage, claims from authoritative sources are often accepted at face value and treated as pre-justified without assessing their truth value: “Daily reporters can merely accept claims as news, whatever their truth may be, investigative reporters, however, must decide what they believe to be the truth” (Ettema and Glasser Citation1998, 160). This makes investigative reporting essentially a moral enterprise which Ettema and Glasser (Citation1998) argue employs recurring narratives about social injustice in which innocence cannot exist without the antimatter of guilt. While victims and transgressors are frequent figures, the aim is usually to expose the failings of a system, anchoring wrongdoings in larger political and cultural contexts (34). Thus, central to the epistemology of investigative journalism is the ability to interrelate and balance epistemic and moral claims (Ekström and Westlund Citation2019b). This is usually achieved by evaluating exposed transgressions with established criteria of conduct, such as the law, ethical codes, and expert opinions.

According to Ettema and Glasser (Citation1985), a videotape of someone caught in the act is considered the heaviest kind of proof within the investigative hierarchy of evidence, but this is only touched upon briefly, probably because such footage was so rare in the 1980s. Overall, visual evidence does not have a central place in the literature on investigative journalism. Perhaps not so strange since much of it was written in the early years of the Internet, where today’s myriad of visual practices was unthinkable. Another reason could be that investigative reporters most often dig into incidents of the past. Before smartphones, social media, and the democratization of photography, the most common ways to visually show misdeeds were either through reenactments or by framing targets filming them in secret (Bromley Citation2005). Ekström (Citation2002) notes that rules, routines, and institutionalized epistemic procedures vary according to media context, genre, and program type. In an article about the epistemologies of TV journalism, he argues that presentation and visualization are crucial to investigative journalism on TV and that access to visual material decides what gets investigated (265). Still, he does not provide an elaborate discussion on how visuals may have an evidentiary value beyond their illustrative function.

Traditionally there has been an institutional divide between different forms of filmic narration and ways of using visuals. While TV news has favored diegetic narratives with interviews, declarative voice-overs, and images as illustrations, documentaries have experimented more with mimetic narratives where images are shown without any additional commentary. Documentary scholar Bill Nichols argues that documentaries, like all fact-based discourses, seek to externalize and objectivize evidence “to place it referentially outside the domain of the discourse itself, which then gestures to its location there, beyond and before interpretation” (Citation2016, 99). The image is ideally suited for this purpose because of its indexicality. Visual evidence, then, when used in a filmic narrative is “charged with a double existence: it is part of the discursive chain but also gives the vivid impression of residing external to it” (Citation2016, 99). This externalization process is eased without any temporal constraints. Online newspapers today can present longer videos and combine diegetic and mimetic narration in a hybridized form that differs from ordinary TV journalism (Bock Citation2012). Furthermore, newspapers such as The New York Times and Wall Street Journal which have embraced investigative aesthetics in their work, do not just use images to investigate stories and visualize facts – they also investigate the image itself, working to uncover facts that are grounded in the visual. This reflexive and critical meta-perspective is partly facilitated by new visualization techniques and flexible forms of interactive storytelling, but the main driving force is that the investigations mainly build on visual material captured by others than the newspapers themselves.

Citizen and Robotic Witnessing

Scholars have noted that visual material captured by citizens, surveillance cameras, and other types of devices have different epistemological underpinnings and aesthetics than visuals made by professionals (Allan and Peters Citation2015; Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2015). In user-generated visuals, there is often a noticeable subjectivity present – shaky camera movements, grainy footage, and imperfect framing. While this signals the need for verification, it also gives the footage perceived authenticity and credibility which enable epistemic truth-telling (Williams, Wahl-Jorgensen, and Wardle Citation2011; Zelizer Citation2007). Allan (Citation2013) notes that the distinction between truth and truth-claim is a vital one in this regard, given that witnessing appeals to the former while revolving around the latter. “Testimony is no guarantor of truth, but rather a personal attestation to perceived facticity; in other words, to be truthful does not imply possession of Truth” (108). The “truth effects” are different in footage from surveillance cameras, dashboard cameras, and other fixed devices. Although programmed and installed by humans, these cameras appear to be operating on their own representing a form of robot witnessing (Gynnild Citation2014), producing footage that has an “aesthetics of objectivity” which is culturally considered unmatchable as visual proof (Gates Citation2013). According to Levin (Citation2002), the rhetorical force of surveillance images lies in their temporal indexicality of always recording, no matter what happens.

Together with big data, digital maps, satellite imagery, and drones (Lewis and Westlund Citation2015; Parasie Citation2015; Usher Citation2020), witness media have transformed journalistic knowledge production, enabling new sensing and sense-making capabilities. While these technologies have the potential to uncover previously uncharted strata in the environment and society, they also pose epistemological and ethical challenges to journalism and its claim to authority. The epistemic authority of journalism, or “the legitimate power to define, describe and explain bounded domains of reality” (Gieryn Citation1999, 1) is inextricably linked up with journalism’s institutionalized procedures as well as the display of these procedures within news texts (Carlson Citation2017, 18). While there is literature that addresses how collected images and videos can be verified from a practical perspective (e.g., Hahn and Stalph Citation2018; Higgins Citation2021; Wardle Citation2014), less attention has been given to how these new epistemic procedures may be integrated and argued as discursive practices in news texts to articulate and justify knowledge claims visually. Studies that can shed light on this from an analytical perspective seem to be in demand.

Data, Research Question, and Method

The Visual Investigation team launched in April 2017 (Jolkovski Citation2020), only months after an NYT report had concluded that a priority of the newsroom should be making its reporting more visual (Leonhardt, Rudoren, and Galinsky Citation2017). The Team defines their work as a combination of visual forensics analysis, digital sleuthing, and traditional investigative reporting (Browne, Willis, and Hill Citation2020b). Their reports are usually presented as stand-alone web documentaries that mix still images, video footage of various kinds, motion graphics, 3D models, satellite imagery, digital maps, music, and voice-over commentary. All videos are published at NYTimes.com, and some on YouTube. Three award-winning investigations are described in the newest edition of the book Investigative Journalism (De Burgh and Lashmar Citation2021), but Gates (Citation2020) is so far the only scholar who has taken an analytical interest in their work. In an analysis of one investigation from 2018, she argues that the video exemplifies how media forensics have become a product of popular sense-making, suggesting that the investigation combines forensic and journalistic epistemologies in its storytelling. However, she does not engage with any literature on investigative journalism, nor does she discuss how visuals are reconstructed into evidence. Therefore, based upon reviewing existing literature and watching all videos produced by the Team since its foundation, the following research question was developed:

RQ: How are visual artifacts such as images and videos reconstructed into evidence in NYT’s visual investigations from 2020?

The method used for this study was visual discourse analysis (Rose Citation2016) following the Sociology of Knowledge Approach to Discourse (SKAD). SKAD was developed in the late 1990s by German sociologist Reiner Keller (Keller Citation2011, Citation2012; Keller, Hornidge, and Schünemann Citation2018). The approach has since informed research across the social sciences, including studies of urban sociology (Christmann Citation2008), online memory practices (Sommer Citation2012), public debates (Wu Citation2012), and legislation processes (Stückler Citation2018). SKAD is not a method, but a research program that offers dynamic tools and guidelines for doing empirical research that must be customized according to the specificity of academic fields and research questions. The theoretical underpinnings of SKAD are Foucault and his concepts of discourses as regimes of knowledge/power (Citation2002) recontextualized within the broader framework of the sociology of knowledge devised by Berger and Luckmann (Citation1966). Following SKAD entails focusing on how knowledge is objectivized and legitimized and how discourses produce their “effects of truth” (Keller, Hornidge, and Schünemann Citation2018).

According to Foucault, knowledge is always dependent on discursive practices (Citation2002, 201) which SKAD defines as observable and describable typical ways of acting out statement production whose implementation requires interpretive competence and active shaping by social actors (Keller Citation2011, 55). This is in line with Goodwin’s definition which states that

discursive practices are used by members of a profession to shape events in the domains subject to their professional scrutiny. The shaping process creates the objects of knowledge that become the insignia of a profession’s craft: the theories, artifacts, and bodies of expertise that distinguish it from other professions. (Goodwin, Citation1994, 606)

So far, the Team has released more than 70 videos. A preliminary inspection of all videos revealed that some discursive practices for invoking and interrogating the visual as evidence were more prevalent than others, suggesting that it was paramount to analyze a larger sample to map out the different ways knowledge claims could be articulated and implied visually. The 2020-batch emerged as the most consistent and representative as it made use of all the main visualization techniques the Team has developed throughout the years. A limited sample from a given year would be large enough to uncover recurring practices and commonalities across various types of investigations, and small enough to delve deep into each video following the criteria for in-depth analysis in qualitative visual methodologies (Rose Citation2016). Three videos were exempted because they did not fulfill the criteria of being full-fledged investigations, resulting in a sample of 14 videos with an average playtime of eight minutes. In previous years, the Team has mainly focused on human rights abuse and conflicts abroad. 2020 started similarly with the downing of Ukrainian Flight 752 over Iran. However, during the ongoing pandemic, George Floyd was killed, sparking riots and unrest across the US, making transgressions perpetrated by police at home the Team’s focus the rest of the year.

All videos were imported to a database in MAXQDA. The software offers a way of selecting and coding clips and segments, which in turn can be retrieved for comparison and analysis. The coding process was informed, but not deductively guided by existing theory. SKAD, like other qualitative approaches, favors sequential analysis of audiovisual data, a frame-by-frame elaboration of categories that give labels to meaning-making activities (Keller, Hornidge, and Schünemann Citation2018). Multiple detailed viewings generated a codebook that was revised and expanded upon numerous times. Every single sequence was assigned multiple codes, resulting in some videos having more than a hundred. One set of codes concerned the artifact/source type present (witness video, still image, document, etc.); another set placed the artifact within a narrative structure (mapping where, how, and when they were deployed), a third set coded how artifacts, actors, and events were classified and framed by the voice-over, while the fourth set of codes focused on superimposed storytelling techniques that were used to underscore a truth claim or to add an evidentiary effect (zooming, encircling, split screens, etc.). Although SKAD forms the theoretical baseline of the study, equally important is Goodwin’s analytical framework. The concepts that emerged from the empirical material were analyzed in relation to coding schemes, highlighting techniques, and other discursive practices that are key in establishing a professional vision and further merged with similar analytical categories recommended by SKAD for analyzing discursive practices and statement production, such as narrative structures, classification systems, and interpretive frames (Keller, Hornidge, and Schünemann Citation2018).

In line with SKAD’s principles of reflexivity, it is important to state that the analysis was guided by the researcher’s hermeneutic point of departure. The study does not argue that the findings pertain to every investigation produced by the Team, or to visual investigations across newsrooms in general. The aim was not to generalize findings in this sense, but rather to generate context-specific conceptualizations (Keller, Hornidge, and Schünemann Citation2018, 63) regarding the visual as evidence, which could function as starting points for further empirical explorations into the visualities of investigative journalism.

Analysis: Discursive Practices as Markers of Authority

NYT’s visual investigations are overwhelmingly dense with information. Approaching such complex material analytically demands a clearly defined point of entry. Based upon the literary review, the analysis will, therefore, mainly be concerned with how truth claims are established visually by discursive practices such as narrativization, coding schemes, and other forms of articulation and representation.

Narrativization: The Distribution and Organization of Visual Artifacts

The analysis starts with a closer look at the various kinds of visual artifacts used in the investigations, and by mapping out how these artifacts are being deployed in the videos’ narrative structure to give them more evidentiary weight. According to SKAD, narrative structures integrate the various statements of discourses into a coherent and communicable form and provide a scheme for the narration with which the discourse can address an audience (Keller, Hornidge, and Schünemann Citation2018, 34). The following section is not a narrative analysis in the classical sense, but rather an attempt to uncover some regularities concerning when, how, and in what order key clips are being introduced.

As shows, witness videos are the most common type of artifact used by the Team, while still images (often used to identify victims and perpetrators) and digital maps also are key components. Every investigation from 2020 apart from one, contains news footage of some kind. This footage is generally used circumstantially to explain how a concrete transgression fits into a larger cultural and political context, setting up the discursive frames where key clips can be constructed into evidence. The transgressive acts are mostly caught on surveillance footage or by witnesses recording with their cellphones. This key footage is given evidentiary weight by how and when it is distributed within the narrative structure of the videos. All investigations are presented in a simple narrative with an introduction phase that sets up the analysis, followed by a walkthrough of the collected visual material. Generally, artifacts that serve explicitly as evidentiary objects to lay epistemic claim to a transgression, reemerge numerous times during an investigation. This repetition is key to establishing a professional vision, as a situated way of seeing a phenomenon in a particular way must be learned (Goodwin, Citation1994). Snippets of key footage are usually teased and explained in the introduction phase, once, twice, or even three times over. As the investigation progresses, key footage is replayed again, at least twice. First, it is played raw in a mimetic narrative, without any additional sound or explanatory commentary, familiarizing the viewer more in-depth with its content, but also demonstrating that NYT has not tampered with the images. And then key footage is replayed again, this time in a diegetic narrative (e.g., Browne and Engelbrecht Citation2020; Browne and Tiefenthäler Citation2020; Browne and Xiao Citation2020; Koettl, Tabrizy, and Xiao Citation2020). The web video format enables NYT to present events seemingly in real-time, as in the investigation into the murder of George Floyd (Hill, Triebert, and Willis Citation2020b), emphasizing the artifacts’ inherent temporality. But also in key moments, by replaying crucial segments over and over. The Team’s combination of these discursive practices strengthens the images’ credibility while simultaneously constricting their meaning potential.

Table 1. Most footage used in NYT’s visual investigations are collected from open sources.

Coding Schemes: Classifying and Interpreting the Visual

Arranging, replaying, and dwelling upon certain clips to emphasize their importance, does not turn them into evidence. To serve such a purpose, the images must be classified, interpreted, and worked on (Dufour and Delage Citation2015). Classifications in the form of coding schemes (Goodwin, Citation1994) are a highly effective form of social typification processes. According to SKAD, classifications divide the worldly given into entities that provide the basis for their conceptual experience, interpretation, and ways of being dealt with (Keller, Hornidge, and Schünemann Citation2018, 33).

Naturally, investigating and interpreting police violence and wildfires demands different coding schemes. Still, viewing all 14 investigations together, there are two sets of overarching coding schemes that the Team uses regardless of the topic they are covering. One set pertains to how the journalists classify collected artifacts and one set pertains to the classifications of the depicted events. The latter schemes vary, but there are regularities across the dataset that establish a moral world of transgressions with systemic failures, victims, and perpetrators, similar to the one detailed by Ettema and Glasser (Citation1998). However, these coding schemes are not invented by the journalists but rather derived from established rules for proper conduct. The actual documents where laws or internal regulations are written are usually shown on screen, hence their prevalence as recurring artifacts (). Key paragraphs are highlighted and read aloud, thereby objectivizing the classification of the uncovered and depicted transgressions, seemingly removing any attached value judgments. Overall, the voice-over commentary is descriptive and neutral, actions are usually not classified as transgressions unless they can be supported by official documents (Browne and Engelbrecht Citation2020; Hill, Triebert, and Willis Citation2020b), statements from external experts (Xiao, Willis, and Koettl Citation2020) or colleagues of the perpetrators (Browne, Singhvi, and Reneau Citation2020a).

The other set of coding schemes the Team uses has epistemological implications and classifies the various types of artifacts used. In six videos, images are explicitly classified by the voice-over as “evidence”. Generally, the word is articulated either at the beginning of an investigation to describe the collected artifacts about to be shown: “We’ll walk you through the evidence, minute by minute (…)” (Tiefenthäler, Triebert, and Hurst Citation2020), or after a damning piece of footage has been presented. For example, when a police officer forgets that his body camera is still on and indirectly admits to a colleague that he knew that Rayshard Brooks (a black man he has just shot twice in the back) was unarmed, Malachy Browne, senior producer of the Team, comments: “This and other evidence will be scrutinized in what has now become a homicide investigation” (Browne and Xiao Citation2020). The combination of the self-incriminating comment made by the officer, Browne’s classification of the clip as evidence, and the surveillance footage of the shooting (having been shown three times over; twice in its entirety), establishes a particular way of seeing and interpreting the depicted events ().

Figure 1. Screengrab 1: Coding schemes transform phenomena observed in a specific setting into the objects of knowledge that animate the discourse of a profession (Goodwin, Citation1994, 606). The screenshot shows surveillance footage and a digital map being classified as evidence in the investigation Ukrainian Flight 752: How a Plane Came Down in 7 Minutes. © 2020 THE NEW YORK TIMES COMPANY.

The reporters also classify collected images and videos further into specific subcategories such as witness videos, surveillance footage, etc. This has at least two epistemic consequences. First of all, it actuates and regulates verification procedures, but it also grants the artifacts an external authenticity beyond that bestowed by the discourse, making their visibilities appear as facts rather than inventions (Nichols Citation2016, 99). However, this does not mean that what appears to be self-evident footage is accepted as pre-justified knowledge. On the contrary, even the George Floyd video – which other news outlets previously had published without questioning its’ veracity, is picked apart, reconstructed, and treated with skepticism which manifests itself explicitly in the different ways clips are geolocated, cross-referenced, and sourced on screen (with photo credits inscribed), but also more implicitly in self-scrutiny and transparency, articulated by the voice-over. The Team states in several investigations that surveillance videos may display the wrong timestamp, that there are gaps in their reconstructions due to missing footage, and that there may still exist unearthed visual artifacts telling a different story (e.g., Browne and Tiefenthäler Citation2020).

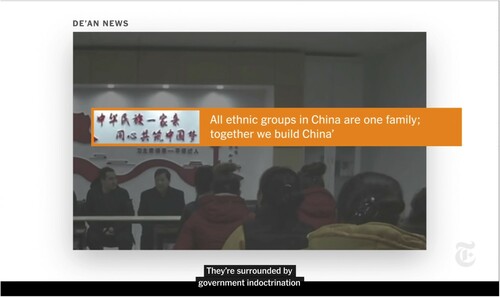

An investigative way of seeing does not only involve chrono- and geolocating, cross-referencing, and retracing how footage emerged on social media, but also investigating the content of the images themselves. In the investigations into Iran’s shadow wars (Willis, Koettl, and Tabrizy Citation2020) and China’s labor camps (Xiao, Willis, and Koettl Citation2020), footage from state television is used as the main source of information. While the images seemingly only contain the official account of events, recontextualized and scrutinized frame by frame, clues and connections are discovered telling a different story ().

Figure 2. Screengrab 2: According to the Times, this footage from Chinese State Television shows Uighurs, a Muslim ethnic minority, unwillingly participating in assimilation programs. An example of what the Times calls “government indoctrination” is discovered and highlighted in the footage. © 2020 THE NEW YORK TIMES COMPANY.

In footage that is either captured by a victim or by a transgressor, the level of visible recontextualization and reinterpretation is more restrained. In one investigation, a local video activist provides NYT with key footage of an incident where he and other protestors in Philadelphia are trapped and tear-gassed by the police (Koettl, Tabrizy, and Xiao Citation2020). NYT uses the footage mostly in a mimetic narrative and lets the viewer experience the widespread panic from the perspective of the protesters for almost an entire minute. The clip, which resurfaces again at the end of the investigation, gives a compelling account of enduring what seems like deliberate wrongdoing from the police. Generally, the Team seems reluctant to address any emotions that may arise from looking at these images of transgressions. By focusing on what the footage shows in a purely denotative sense, the affective side is left to work implicitly. Journalists are careful not to overemphasize trauma and pain to create identification and solidarity with those depicted (Andén-Papadopoulos and Pantti Citation2014). The use of mimetics and the outsourcing of moral judgment enables NYT to keep their professional distance, positioning themselves “close, but not too close” (Silverstone Citation2004, 444) to the events they are investigating.

Synchronization, Juxtaposition, Inscriptions, and Highlighting Techniques

Another way of reconstructing visual artifacts as evidence, albeit more implicitly, is to reference the epistemic procedures involved in the process of retrieving and analyzing them: “The Times examined witness videos, security footage, police bodycam, and dash-cam videos. We synchronized and slowed down those videos so we can see and hear what unfolded” (Browne and Tiefenthäler Citation2020). Gathering, collecting, analyzing, combing through, examining, breaking down, slowing down, forensically mapping, assembling – all these procedures are mentioned by the voiceover, and most of them are visualized on-screen as discursive practices. In seven investigations, a grid of artifacts is displayed somewhere in the narrative structure, most often in the introduction phase. This grid is essentially a visualization of a familiar trope in investigative journalism; namely that the reporting builds on a vast amount of collected evidence which will only make sense if pieced together as a whole. Such an epistemological jigsaw puzzle would perhaps be more familiar if it were invoked as documents laid systematically out on the floor or as a network map hanging on the wall, but its role as a self-referential authoritative statement pattern within the discourse nevertheless remains the same ().

Figure 3. Screengrab 3: Two body cameras attached to the police officers (left-hand side), one dashboard camera and one witness video displayed simultaneously in a grid in the investigation The Killing of Rayshard Brooks: How a 41-Minute Police Encounter Suddenly Turned Fatal. © 2020 THE NEW YORK TIMES COMPANY.

The grid also serves as a starting point for explaining how knowledge claims are verified and justified. In accordance with the epistemology of investigative journalism, collected footage is usually verified in correspondence with each other. In this case by synchronization. The Team uses video editing software and/or manual comparison of details found in the images or in the sound of the footage to piece together the unfolding of events from multiple perspectives subsequently placing corresponding clips on a timeline in the correct order. The footage is then displayed simultaneously in a split-screen mode, showing the same transgression from two, three, or even four different angles. While the grid on the one hand highlights the subjectivity of each video and thus reveals their constructive nature, it also functions as an inscription device that transforms this embodied subjectivity into inter-subjectivity, creating an all-seeing eye that objectifies the knowledge of the events we are seeing (Berger and Luckmann Citation1966). The split-screen is also used to demonstrate the location of witnesses. A digital map with motion graphics showing camera positions and their cones of vision is displayed on one side, while the geolocated footage runs on the other (Hill, Triebert, and Willis Citation2020b; Koettl and Botti Citation2020; Tiefenthäler, Triebert, and Hurst Citation2020). The maps are perceived as real, not because of their correspondence to reality, but due to their correspondence with the adjacent video footage. Simultaneously, the truth-value of the footage is strengthened vice versa by the very same logic: When NYT pinpoints on maps where the footage was taken, coherence is made between the two artifacts, generating a dynamic where they validate each other ().

Figure 4. Screengrab 4: A juxtaposed digital map with superimposed inscriptions and video footage from the investigation The David McAtee Shooting: Did Aggressive Policing Lead to a Fatal Outcome. © 2020 THE NEW YORK TIMES COMPANY.

Noticeable inscriptions (Goodwin, Citation1994) in the split-screen above are the cones of vision, the map itself, the text above the building, the camera devices, the street names, the greyscale filter, the timestamp of the surveillance video, and the NYT logo. These cascades of inscriptions (Latour Citation1986) increase the artifacts’ evidentiary weight while simultaneously discursively constructing an optical device that synthesizes multiple forms of evidence, putting the viewer above and at the scene at the same time. By combining the act of both “being there” and witnessing from afar, a form of hyper-aesthetics arises with an inherent “interlinkedness” that mutates and becomes reflexive (Fuller and Weizman Citation2021, 57). The split-screen mode represents a repeated inscription device within the discourse. It is a form of evidence that goes beyond the visual, with a logic that is based on the epistemological principles of cross-verification.

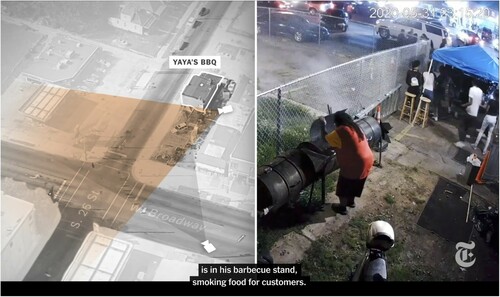

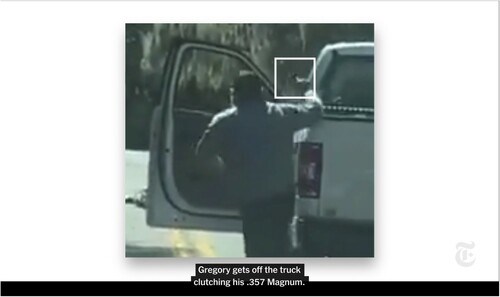

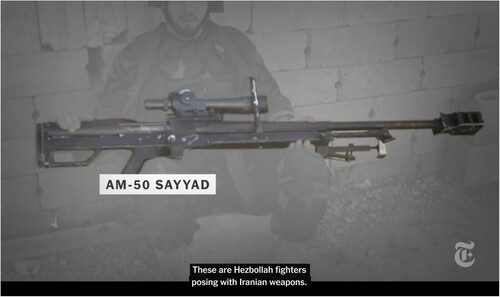

Other recurring discursive practices instrumental in NYT’s professional vision are so obvious and simple that they are hardly noticed. When footage of crucial events is replayed, images are sometimes either slowed down or frozen. In addition, the camera may also zoom in on important elements and encircle them. Or the image itself may be cropped on-screen so that what remains displayed is the element that NYT wants the viewer to notice (Cooper, Hill, and Hurst Citation2020; Hill, Tiefenthäler, and Browne Citation2020a; Willis, Koettl, and Tabrizy Citation2020). Again, the web video format’s flexibility is demonstrated as it enables NYT to toggle seamlessly between still- and moving images, creating a hybridization of the opposing strategies in the Rodney King trial. By decontextualizing video footage into still images, the work of the viewer is radically changed as it enables and encourages a close reading, freezing crucial moments in time, before NYT recontextualizes the images yet again back to their original temporal state. To help the viewer even further, highlighting techniques are added whose epistemological purpose is to make certain objects, actions, and actors more salient. Guns are typically highlighted, as well as patches and other insignias on clothes and uniforms. Sometimes the victim is singled out against a chaotic background, other times the aggressors are brought into focus. In isolation, these highlighting techniques in themselves have little authoritative effect, but when they are combined in an active interplay between coding schemes, other forms of discursive practices, and the domain of scrutiny to which they all are being simultaneously applied, “they mutually enhance each other, creating a demonstration that is greater than the sum of its part” (Goodwin Citation1994, 620).

On the next pages are four different highlighting techniques frequently deployed by the Team in their visual investigations in 2020 ().

Figure 5. Screengrab 5: Footage is stopped, and a gun is highlighted in Ahmaud Arbery’s Final Minutes: What Videos and 911 Calls Show. © 2020 THE NEW YORK TIMES COMPANY.

Figure 6. Screengrab 6: A weapon is singled out and the background desaturated in How Did Iran’s Qassim Suleimani Wield Power? We Tracked the Quds Force Playbook. © 2020 THE NEW YORK TIMES COMPANY.

Discussion and Conclusions

In this study, I have mapped some of the most prominent discursive practices used by NYT to establish an investigative way of seeing events. In their 2020-videos, the Visual Investigations team uses two overarching coding schemes. Together they construct a multidimensional discursive framework with epistemological and moral implications that classifies and interprets collected artifacts and depicted events. The Team also replays key footage and uses highlighting techniques such as zooming, cropping, and encircling to call attention to indexical elements in the images, further shaping the viewer’s perception of important moments and crucial details. However, equally important as the content of collected singular artifacts is the relations between them. Inscriptions in the form of split screens and grids are used to interlink visuals that otherwise would be difficult to see simultaneously, such as witness videos filmed in different locations. Taken together these discursive practices serve as markers of authority that externalize and reconstruct collected images and videos into evidence of moral and legal transgressions. The authority of the Team’s investigative vision is discursive, relational, and a product of the sociopolitical and historical context in which it is embedded (Canella Citation2021). The fact that it is NYT – one of the world’s most legendary and trustworthy newspapers, that claim epistemic authority over these events is thus of course not without significance.

This study contributes mainly to two strands of scholarship within journalism studies. The first is journalism as witnessing (Ashuri and Pinchevski Citation2009; Pantti Citation2020). When witness media is used in investigative journalism, indexical temporality and correspondence between artifacts are highlighted, while the affective is left to work implicitly. Investigative aesthetics enable new ways of showing and verifying witness media, mapping subjective truth-claims poly-perspectival (Fuller and Weizman Citation2021), thereby overcoming many of the epistemological tensions that are associated with singular citizen-generated visuals in existing literature (Allan and Peters Citation2015). In the longer run, these visual forms of cross-verification can have an impact on how witness media is displayed in other forms of journalism as well, especially when reporters are physically prevented from being present on the ground.

The study also contributes to the literature on the epistemologies of digital journalism (Carlson Citation2020; Ekström and Westlund Citation2019a) by bringing attention to how images and videos are used and constructed as evidentiary objects in online investigative journalism. Contrary to what was the standard in the mid-1980s (Ettema and Glasser Citation1985), the findings indicate that visual knowledge is treated as any other type of knowledge within the investigative hierarchy of evidence. Even though a video of someone performing a transgression may look like incontestable proof, it still needs to be weighed, analyzed, and verified in relation to other knowledge claims stemming from the same incident to qualify as a justified belief and serve as evidence.

Lastly, this study has introduced and combined the Sociology of Knowledge Approach to Discourse (SKAD) (Keller, Hornidge, and Schünemann Citation2018) with the analytical framework of Goodwin’s (Citation1994) professional vision as a novel approach for analyzing visual journalism. SKAD has proven especially fitting for several reasons. First, the approach acknowledges visuals as empirical data on the same level as other textual forms. Second, SKAD comes with an adjustable toolbox for analyzing discursive practices that seems especially relevant for researchers that conceptualize journalism as knowledge production. Third, by viewing discourse as a heuristic device for regulating statements, SKAD can relate the visual and visual practices to greater theories of knowledge and other stocks of knowledge, thereby preventing visual essentialism, a term coined by Bal (Citation2003) to describe when visuals are deprived of relevant contexts, proclaimed pure and pinned against other modes of representation in a hierarchy of primacy.

Despite SKAD’s flexibility, there are some noticeable disadvantages with the macro-perspective it establishes: Its sociology of knowledge-based terminology, level of abstraction, and focus on discursive regularities can complicate existing vocabulary, take lesser important artifacts for granted, and overlook non-recurring practices, thereby neglecting knowledge that stakeholders may hold as important. Another shortcoming is that the study has focused mostly on NYT’s way of seeing while paying less attention to other competing visions. Further research should choose different sample strategies to investigate epistemic struggles where conflicting knowledge stocks and ways of seeing are equally represented. Researchers should also pay more attention to how emerging visual practices are carried out in newsrooms: How are open-source intelligence techniques being combined with traditional journalistic procedures? How can journalists know that they have collected all the crucial evidence about an incident? And which artifacts do not make it into the final reporting and why? Ethnographic research seems necessary to explore these questions further.

Finally, this has been a study first and foremost of the visibilities of investigative journalism, ignoring largely the parts that cannot be depicted. Further studies should also try to assess its invisibilities, namely what is hidden or displayed as compensatory artifacts. Schmid (Citation2012) suggests a simple, but effective analytical move in this regard: We need to ask which specific absence that generates the origin of a specific presence. Compensatory elements such as the 3D model in the investigation into the killing of Breonna Taylor and the animation superimposed on the maps in the investigations into the killings of Ahmaud Arbery and Michael Reinoehl are examples of inscription devices that function as stand-ins for missing footage. These objects and their epistemological function should be explored and theorized more in-depth in future studies.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the reviewers and my supervisors for their feedback and comments. Thanks also to NYT for letting me use eight screenshots in my article.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adami, E. 2016. “How Do You Watch a Revolution? Notes From the 21st Century.” Journal of Visual Culture 15 (1): 69–84.

- Allan, S. 2013. Citizen Witnessing: Revisioning Journalism in Times of Crisis. Oxford: Polity Press.

- Allan, S. 2014. “Witnessing in Crisis: Photo-Reportage of Terror Attacks in Boston and London.” Media, War & Conflict 7 (2): 133–151.

- Allan, S., and C. Peters. 2015. “Visual Truths of Citizen Reportage: Four Research Problematics.” Information, Communication & Society 18 (11): 1348–1361.

- Andén-Papadopoulos, K., and M. Pantti. 2014. Amateur Images and Global News. Bristol: Intellect Books.

- Ashuri, T., and A. Pinchevski. 2009. “Witnessing as a Field.” In Media Witnessing: Testimony in the Age of Mass Communication, edited by P. Frosh, and A. Pinchevski, 133–157. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bal, M. 2003. “Visual Essentialism and the Object of Visual Culture.” Journal of Visual Culture 2 (1): 5–32.

- Barthes, R. 1977. Rhetoric of the Image. Image Music Text. New York: Hill and Wang.

- Berger, P. L., and T. Luckmann. 1966. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. New York: Anchor Books.

- Bock, M. A. 2012. “Newspaper Journalism and Video: Motion, Sound, and New Narratives.” New Media & Society 14 (4): 600–616.

- Bock, M. A., and D. A. Schneider. 2017. “The Voice of Lived Experience: Mobile Video Narratives in the Courtroom.” Information, Communication & Society 20 (3): 335–350.

- Brandtzaeg, P. B., M. Lüders, J. Spangenberg. 2016. “Emerging Journalistic Verification Practices Concerning Social Media.” Journalism Practice 10 (3): 323–342.

- Bromley, M. 2005. “Subterfuge as Public Service: Investigative Journalism as Idealized Journalism.” In Journalism: Critical Issues, edited by S. Allan, 313–327. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

- Browne, M., and C. Engelbrecht. 2020. “The David McAtee Shooting: Did Aggressive Policing Lead to a Fatal Outcome?” The New York Times.

- Browne, M., A. Singhvi, and N. Reneau. 2020a. “How the Police Killed Breonna Taylor.” The New York Times.

- Browne, M., and A. Tiefenthäler. 2020. “Ahmaud Arbery’s Final Minutes: What Videos and 911 Calls Show.” The New York Times.

- Browne, M., H. Willis, and E. Hill. 2020b. “How The Times Makes Visual Investigations.” YouTube.

- Browne, M., and M. Xiao. 2020. “The Killing of Rayshard Brooks: How a 41-Minute Police Encounter Suddenly Turned Fatal.” The New York Times.

- Canella, G. 2021. “Journalistic Power: Constructing the “Truth” and the Economics of Objectivity.” Journalism Practice, 1–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2021.1914708.

- Carlson, M. 2017. Journalistic Authority: Legitimating News in the Digital Era. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Carlson, M. 2020. “Journalistic Epistemology and Digital News Circulation: Infrastructure, Circulation Practices, and Epistemic Contests.” New Media & Society 22 (2): 230–246.

- Chouliaraki, L. 2015. “Digital Witnessing in War Journalism: The Case of Post-Arab Spring Conflicts.” Popular Communication 13 (2): 105–119.

- Christmann, G. B. 2008. “The Power of Photographs of Buildings in the Dresden Urban Discourse. Towards a Visual Discourse Analysis.” Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research 9 (3). doi:https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-9.3.1163.

- Cooper, S., E. Hill, and W. Hurst. 2020. “I Am On Your Side: How the Police Gave Armed Groups a Pass in 2020.” The New York Times.

- Cubitt, S. 2002. “Visual and Audiovisual: From Image to Moving Image.” Journal of VCculture 1 (3): 359–368.

- De Burgh, H., and P. Lashmar. 2021. Investigative Journalism. London: Routledge.

- Dubberley, S., A. Koenig, and D. Murray. 2020. Digital Witness: Using Open Source Information for Human Rights Investigation, Documentation, and Accountability. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dufour, D., and C. Delage. 2015. Images of Conviction: The Construction of Visual Evidence. Paris: Le Bal.

- Ekström, M. 2002. “Epistemologies of TV Journalism: A Theoretical Framework.” Journalism 3 (3): 259–282.

- Ekström, M., and O. Westlund. 2019a. “The Dislocation of News Journalism: A Conceptual Framework for the Study of Epistemologies of Digital Journalism.” Media and Communication 7 (1): 259–270.

- Ekström, M., and O. Westlund. 2019b. “Epistemology and Journalism.” In Oxford Encyclopedia of Journalism Studies, edited by Henrik Örnebring. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ettema, J. S., and T. L. Glasser. 1985. “On the Epistemology of Investigative Journalism.” Communication 8 (2): 183–206.

- Ettema, J. S., and T. L. Glasser. 1998. Custodians of Conscience: Investigative Journalism and Public Virtue. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Fiske, J. 1996. Media Matters: Race & Gender in US Politics. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

- Foucault, M. 1977. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Pantheon.

- Foucault, M. 2002. Archaeology of Knowledge. New York: Routledge.

- Fuller, M., and E. Weizman. 2021. Investigative Aesthetics: Conflicts and Commons in the Politics of Truth. London: Verso.

- Gates, K. 2013. “The Cultural Labor of Surveillance: Video Forensics, Computational Objectivity, and the Production of Visual Evidence.” Social Semiotics 23 (2): 242–260.

- Gates, K. 2020. “Media Evidence and Forensic Journalism.” Surveillance & Society 18 (3): 403–408.

- Gieryn, T. F. 1999. Cultural Boundaries of Science: Credibility on the Line. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Godler, Y., and Z. Reich. 2017. “Journalistic Evidence: Cross-Verification as a Constituent of Mediated Knowledge.” Journalism 18 (5): 558–574.

- Goodwin, C. 1994. “Professional Vision.” American Anthropologist 96 (3): 606–633.

- Greenwood, K., and R. J. Thomas. 2015. “Locating the Journalism in Citizen Photojournalism: The Use and Content of Citizen-Generated Imagery.” Digital Journalism 3 (4): 615–633.

- Gynnild, A. 2014. “The Robot Eye Witness: Extending Visual Journalism Through Drone Surveillance.” Digital Journalism 2 (3): 334–343.

- Hahn, O., and F. Stalph. 2018. Digital Investigative Journalism. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Higgins, E. 2021. We Are Bellingcat. London: Bloomsbury.

- Hill, E., A. Tiefenthäler, and M. Browne. 2020a. “Videos Show How Federal Officers Escalated Violence in Portland.” The New York Times.

- Hill, E., C. Triebert, and H. Willis. 2020b. “How George Floyd Was Killed in Police Custody.” The New York Times.

- Ibrahim, Y. 2014. “Social Media and the Mumbai Terror Attack.” In Citizen Journalism: Global Perspectives, edited by E. Thorsen, and S. Allan, 15–26. New York: Peter Lang.

- Jolkovski, A. 2020. “NY Times’ Pioneering Visual Investigations: Behind the Scenes.” WAN-IFRA.

- Keller, R. 2011. “The Sociology of Knowledge Approach to Discourse (SKAD).” Human Studies 34 (1): 43.

- Keller, R. 2012. “Entering Discourses: A New Agenda for Qualitative Research and the Sociology of Knowledge.” Qualitative Sociology Review 8 (2): 23–56.

- Keller, R., A.-K. Hornidge, and W. J. Schünemann. 2018. The Sociology of Knowledge Approach to Discourse: Investigating the Politics of Knowledge and Meaning-Making. London: Routledge.

- Koettl, C., and D. Botti. 2020. “How an Oregon Wildfire Became One of the Most Destructive.” The New York Times.

- Koettl, C., N. Tabrizy, and M. Xiao. 2020. “How the Philadelphia Police Tear-Gassed a Group of Trapped Protesters.” The New York Times.

- Latour, B. 1986. “Visualization and Cognition.” Knowledge and Society 6 (6): 1–40.

- Latour, B., and S. Woolgar. 1986. Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Leonhardt, D., J. Rudoren, and J. Galinsky. 2017. Journalism That Stands Apart. https://www.nytimes.com/projects/2020-report/index.html.

- Levin, T. Y. 2002. “Rhetoric of the Temporal Index: Surveillant Narration and the Cinema of “Real Time”.” In Rhetorics of Surveillance from Bentham to Big Brother, edited by Thomas Y. Levin, Ursula Frohne, and Peter Weibel, 578–593. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Lewis, S. C., and O. Westlund. 2015. “Big Data and Journalism: Epistemology, Expertise, Economics, and Ethics.” Digital Journalism 3 (3): 447–466.

- Mast, J., and S. Hanegreefs. 2015. “When News Media Turn to Citizen-Generated Images of War: Transparency and Graphicness in the Visual Coverage of the Syrian Conflict.” Digital Journalism 3 (4): 594–614.

- Mnookin, J. L. 1998. “The Image of Truth: Photographic Evidence and the Power of Analogy.” Yale JL & Human 10: 1.

- Mortensen, M. 2014. Journalism and Eyewitness Images: Digital Media, Participation, and Conflict. London: Routledge.

- Müller, N. C., and J. Wiik. 2021. “From Gatekeeper to Gate-Opener: Open-Source Spaces in Investigative Journalism.” Journalism Practice, 1–20.

- Newton, J. 2001. The Burden of Visual Truth: The Role of Photojournalism in Mediating Reality. New York: Routledge.

- Nichols, B. 1995. Blurred Boundaries: Questions of Meaning in Contemporary Culture. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Nichols, B. 2016. Speaking Truths With Film: Evidence, Ethics, Politics in Documentary. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Pantti, M. 2020. “Journalism and Witnessing.” In The Handbook of Journalism Studies, edited by K. Wahl-Jorgensen, and T. Hanitzsch, 151–164. London: Routledge.

- Parasie, S. 2015. “Data-Driven Revelation? Epistemological Tensions in Investigative Journalism in the Age of “Big Data”.” Digital Journalism 3 (3): 364–380.

- Park, R. E. 1940. “News as a Form of Knowledge: A Chapter in the Sociology of Knowledge.” American Journal of Sociology 45 (5): 669–686.

- Phillips, D. 2009. “Actuality and Affect in Documentary Photography.” In Using Visual Evidence, edited by R. Howells, and R. Matson, 55–77. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

- Protess, D. L., F. L. Cook, and J. Doppelt. 1991. The Journalism of Outrage: Investigative Reporting and Agenda Building in America. New York: Guilford Press.

- Robinson, S. 2009. “If You Had Been With Us: Mainstream Press and Citizen Journalists Jockey for Authority Over the Collective Memory of Hurricane Katrina.” New Media & Society 11 (5): 795–814.

- Rose, G. 2016. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching With Visual Materials. London: Sage.

- Schmid, A. 2012. “Bridging the Gap: Image, Discourse, and Beyond-Towards a Critical Theory of Visual Representation.” Qualitative Sociology Review 8: 2.

- Schwalbe, C. B., B. W. Silcock, and E. Candello. 2015. “Gatecheckers at the Visual News Stream: A New Model for Classic Gatekeeping Theory.” Journalism Practice 9 (4): 465–483.

- Schwartz, L.-G. 2009. Mechanical Witness: A History of Motion Picture Evidence in US Courts. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sekula, A. 1986. “The Body and the Archive.” October 39: 3–64.

- Silverstone, R. 2004. “Regulation, Media Literacy and Media Civics.” Media, Culture & Society 26 (3): 440–449.

- Sommer, V. 2012. “The Online Discourse on the Demjanjuk Trial: New Memory Practices on the World Wide Web?” Journal for Communication Studies 5: 10.

- Stückler, A. 2018. “Legislation and Discourse: Research on the Making of Law by Means of Discourse Analysis.” In The Sociology of Knowledge Approach to Discourse: Investigating the Politics of Knowledge and Meaning-Making, edited by R. Keller, A.-K. Hornidge, and W. J. Schünemann, 112–132. London: Routledge.

- Sturken, M., and L. Cartwright. 2017. Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Tagg, J. 1999. “Evidence, Truth and Order: A Means of Surveillance.” In Visual Culture: The Reader, edited by S. Hall, and J. Evans, 244–273. London: Sage.

- Tiefenthäler, A., C. Triebert, and W. Hurst. 2020. “Ukrainian Flight 752: How a Plane Came Down in 7 Minutes.” The New York Times.

- Traue, B., M. Blanc, and C. Cambre. 2019. “Visibilities and Visual Discourses: Rethinking the Social with The Image.” Qualitative Inquiry 25 (4): 327–337.

- Usher, N. 2020. “News Cartography and Epistemic Authority in the Era of Big Data: Journalists as Map-Makers, Map-Users, and Map-Subjects.” New Media & Society 22 (2): 247–263.

- Wahl-Jorgensen, K. 2015. “Resisting Epistemologies of User-Generated Content? Cooptation, Segregation and the Boundaries of Journalism.” In Boundaries of Journalism: Professionalism, Practices and Participation, edited by M. Carlson, and S. C. Lewis, 169–185. London: Routledge.

- Wardle, C. 2014. “Verifying User-Generated Content.” In Verification Handbook: A Definitive Guide to Verifying Digital Content for Emergency Coverage, edited by C. Silverman, 24–33. Maastricht: European Journalism Centre.

- Weizman, E. 2017. Forensic Architecture: Violence at the Threshold of Detectability. New York: MIT Press.

- Williams, A., K. Wahl-Jorgensen, and C. Wardle. 2011. “More Real and Less Packaged: Audience Discourse on Amateur News Content and Its Effects On Journalism Practice.” In Amateur Images and Global News, edited by K. Andén-Papadopoulos, and M. Pantti, 195–209. Bristol: Intellect Books.

- Willis, H., C. Koettl, and N. Tabrizy. 2020. “How Did Iran’s Qassim Suleimani Wield Power? We Tracked the Quds Force Playbook.” The New York Times.

- Wu, A. X. 2012. “Hail the Independent Thinker: The Emergence of Public Debate Culture on the Chinese Internet.” International Journal of Communication 6: 2220–2244.

- Xiao, M., H. Willis, and C. Koettl. 2020. “Wearing a Mask? It May Come From China’s Controversial Labor Program.” The New York Times.

- Zelizer, B. 2005. “Journalism Through the Camera’s Eye.” In Journalism: Critical Issues, edited by S. Allan, 167–176. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

- Zelizer, B. 2007. “On “Having Been There”:“Eyewitnessing” as a Journalistic Key Word.” Critical Studies in Media Communication 24 (5): 408–428.