ABSTRACT

This article examines the post-award implications of international prize culture within the journalism profession. Through qualitative interviews with winners of CNN competitions, this paper specifically investigates how news professionals discursively construct the notion of excellence within the space of international award practice, and then how they subsequently perceive their roles in the post-award dispensation. The key findings show that journalists’ understanding of excellence through awards is fluid and based on individual, institutional as well as professional notions of what constitutes par/sub-par journalism. These “bearers of excellence” perceive themselves as promoters of high standards of journalistic practice and champions of normative roles, such as the watchdog role, which fits into the broader mission of the specific institution sponsoring the awards.

Introduction

Today’s awards in/for journalism—whether it is the Pulitzer Prize to a non-journalist like Darnella Frazier, or from external institutions like the Nobel Peace Prize committee to journalists Maria Ressa and Dmitry Muratov—all raise critical questions on journalistic authority. In particular, the award practice within journalism, beyond the ritualism and symbolism (Pallas, Wedlin, and Grünberg Citation2016), stirs tensions within the profession because of the fanfare surrounding the nominations, the award ceremonies, the publicity surrounding the winners and the capital accumulated through the awards, e.g., fellowships, scholarships, career mobility, etc. The awards and associated practice inevitably instigate discursive struggles, especially when they validate and enhance the “value” of a specific cadre of news professionals (Heinich Citation2009; Nölleke, Hanusch, and Maares Citation2022; Volz Citation2013). Such tensions and recent shifts in journalistic “prize culture” and an accompanying proliferation of awards in society (English Citation2002; Lanosga Citation2014), suggest an urgent need to re-evaluate awards and their possible implications for journalism as a profession. In this paper, we particularly focus on the international award practice—facilitated through the international competitions targeting journalists across the globe—and the attendant imaginaries about excellence that this promotes within journalistic cultures.

Often, there is consensus among journalism scholars that the Anglo-American hegemonic model of journalism has shaped professional role orientations, despite journalistic culture-specific variances around the world (Hanitzsch et al. Citation2019; Mabweazara and Mare Citation2021; Nerone Citation2012). There is, however, insufficient understanding into how practices of international awards reinforce this cultural hegemony, mainly of Minority World Countries,Footnote1 thus, possibly influencing societal expectations and behaviour of journalists.

Existing studies show journalistic awards as markers of “excellence”—rigour in news reporting, creativity, professionalism, and social impact (Beam, Dunwoody, and Kosicki Citation1986; Shapiro, Albanese, and Leigh Citation2006; Volz Citation2013)—in a discursive environment of quality journalism. Indeed, studies of journalistic awards have focused mostly on the criteria that define professional achievements. However, while awards “produce professional consensus and uniformity” through appraising journalistic work, they also present a dilemma over what should constitute “excellence” in the practice of journalism (Volz Citation2013, 392). If excellence is the currency of journalistic awards, its nature as an aspirational quality for news professional could be shaping journalistic behaviour and societal expectations of the profession (Biddle Citation1979). We, therefore, consider journalistic excellence and professional roles as interdependent and inextricable. In that sense, we argue that understanding how award practices shape journalistic role orientations, helps us to shed light on how normative roles emerge within a specific journalistic culture.

Relatedly, recent studies have expanded the conceptions of the profession beyond the traditional journalistic practice(s) and field, for example, through interrogating pre-professional roles, quasi-professional roles or even non-journalistic (or non-human) roles (see Bowe et al. Citation2021; Schapals, Maares, and Hanusch Citation2019; Weber and Kosterich Citation2018). We take the cue from these studies seeking to fully encapsulate role orientations amid today’s disruptions in journalism, and argue that it is important as well to unravel how the different dispositions of the “bearers of excellence” (Botma Citation2017) within the profession shape their post-award role orientations.

The aim of this paper is, therefore, to examine how award-winning journalists perceive their roles in a discursive space of international awards. We empirically interrogate how winners of the “CNN African Journalist of the Year Awards” perceive their roles as shaped by their notion of excellence through the international award practice. This study focuses on the case of the winners of the Africa edition of the competitions that ran between 1995 and 2016. CNN’s journalism awards were considered the “most prestigious” on the continent, with more than 300 journalists from all around Africa receiving these prizes (some occupying influential positions within traditional and peripheral news organisations today).

Our results point to an understanding of excellence and roles performed by award winners that is ever shifting based on individual, institutional, and professional notions of what constitutes outstanding journalistic practice within national cultures. Secondly, journalists view themselves as champions of normative roles (but promoters of mostly monitorial journalism), which fits into the criteria of winning entries in the CNN competitions. Thirdly, journalists consider their role as agents of “Pan-African journalism”, which implies a monolithic idea of journalism(s) on the continent as promoted through the awards. However, career journalists conflate “Pan-African journalism” with “alternative excellent journalism”, implying an aspiration for a substitute for the Anglo-American cultural hegemony that CNN represents. This aspiration also reveals their post-colonial reflexivity of CNN’s practices that accentuate racial stereotypes in the news coverage of Majority World Countries. This study contributes to journalism studies by unravelling post-award role perceptions and conceptualisations of journalistic excellence in a discursive regime of international award practice.

Literature Review

The popularity of awards in the digital age has mostly followed the diversifications of journalism (e.g., new forms of journalism and new actors such as non-profits), the quest to maintain journalistic authority and generally an awards culture tied to fame and “audit society” (Carlson Citation2017; Pallas, Wedlin, and Grünberg Citation2016, 1070). Professional awards/prizes and other symbolic rewards of journalistic achievement are further recognised as expanding journalistic practice. As “symbolic systems”, awards promote both the celebration and celebritisation of journalists (even when this is not the intended outcome of the fanfare and publicity surrounding award ceremonies). We argue that awards could shape journalists’ relationship with the profession, and thus the ways they perceive their roles. Beyond symbolism, awards have an evaluative value that benefits organisations and audiences (Pallas, Wedlin, and Grünberg Citation2016), and further recognising journalists marginalised within newsrooms (Nölleke, Hanusch, and Maares Citation2022; Volz and Lee Citation2013).

This paper considers that viewing career journalists from the lens of an international awards practice, is important because of three significant factors: First, is because of the shifting meaning of journalistic “excellence” today. The profession is experiencing constant change despite a dominant cultural hegemony of Minority World Countries (Nerone Citation2012) as well as different conceptions of “good” journalism emerging from within and outside the journalistic field (Örnebring and Jönsson Citation2004). Two, CNN’s international practice and awards have had implications on global journalism. We argue that award practices promoted through the international news organisation have possibly contributed to idealised forms of “good” journalism in different journalistic cultures, which are yet to be explored in journalism scholarship. Third, post-award role orientations of journalists are worth interrogating, especially when the status of journalists shifts from that of a mere professional to award-winner. It is, therefore, worthwhile to examine what these professionally excellent journalists think they do after they win awards, and subsequently how the markers of recognition within the profession shape societal expectations (see Hellmueller and Mellado Citation2015).

Excellence Within an Award Practice

Excellence is vaguely defined in journalism studies but is mostly used to refer to practices that meet but exceed traditional standards of journalism, or attributes within the professional and institution of journalism that are deemed exceptional. Existing studies describe excellence through awards as an appraisal of journalists’ achievements, an object of metajournalistic discourse, a symbol of journalistic authority and social status, boundary marker (what is par/sub-par journalism) and a bulwark of journalistic autonomy and press freedom (Carlson Citation2017; Jenkins and Volz Citation2018; Lough Citation2021). There is an interdependence between professionalism and excellence. Excellence is a marker of a common ideology within the profession in regard to the highest standards of journalism (Bogart Citation2004). Such an interdependence raises two problems. First, the contentious nature of professionalism especially in the digital age raises questions as to whether there can be a common understanding of journalistic standards today. Second, it is increasingly acknowledged that ideas about journalistic standards are incongruent with those of the public they claim to serve (Banjac Citation2022; Karlsson and Clerwall Citation2018). This incongruence also occurs at the level in which journalists perceive good journalistic practice, and what is perceived as good for the audience (Bogart Citation2004; Coddington, Lewis, and Belair-Gagnon Citation2021).

Scholars acknowledge there is largely a consensus as to what constitutes journalism within the profession, and within a discursive regime of journalistic awards/prizes, such a uniformity in acknowledgement of the highest standards is legitimised through a peer-review process. It is also acknowledged that changes in journalism standards over time have to do with journalistic cultures, such as the importance of objectivity in liberal democracies (Bogart Citation2004). Markers of excellence in themselves could be vague and complex even when they are associated with high standards. For example, when a story is referred to as “interesting”, it implies a highly subjective nature that may not breed a common understanding among intended audiences (Bogart Citation2004). Moreover, the prize culture within journalism is increasingly showing the malleability of the profession. For example, non-journalistic actorsFootnote2 have recently received journalism awards.

However, through journalistic awards, the profession is also legitimised in two ways. First, as a profession striving for the highest standard possible to fulfil its public function, and two, as a profession that rises beyond its institutional limitations. Thus, the profession is not beholden to corporate interests or market demands (that is why, for example, the institutional success of a story, e.g., ratings, is often not a criterion for journalistic excellence). This then leads us to the following research question pertinent to understanding how news professionals conceptualise journalistic excellence:

RQ1: What do award winners’ self-perceptions of journalistic excellence reveal about international awards practice?

Finally, in most cases, most awards tend to go to career journalists in resource-rich news organisations. Moreover, while awards could promote professionalism, they inspire a “prize frenzy” that could divert attention from journalism’s core mission to inform the public as journalists’ labour is invested in winning content and strategies, rather than audiences’ needs (Shepard Citation2000; cf. English Citation2002). Additionally, the attention to winners could mean that news organisations pay less attention to the “loser” professional, making it possible for awards to have a “demoralising effect” (Coulson Citation1989; Shepard Citation2000, 25).

Post-award Roles in Journalistic Cultures

Journalism awards mostly apply to professional. Through the awards, individual journalists gain recognition and credibility, not only at the organisational level, but also among their peers and the field of journalism (Jenkins and Volz Citation2018). This recognition can translate into social, cultural, and economic capital. Social capital materialises as prestige, respect and having a good position in the journalistic hierarchy, while economic capital is evident in promotions and hiring (Willig Citation2013; cf. Beam, Dunwoody, and Kosicki Citation1986; Bourdieu Citation1986; Nölleke, Hanusch, and Maares Citation2022). As such, the forms of capital inherent in journalism awards institutionalise and shape what it means to do journalism. Award-winning entries are signals to standards of journalism and best practices, and this creates a strong relationship between awards and journalism (Jenkins and Volz Citation2018; Lanosga Citation2014; Lough Citation2021, 306). We argue, therefore, that award practices are part and parcel of the construction of roles.

Further, awards introduce a set of self-referential practices (Kristensen and Mortensen Citation2017; Nöth Citation2007); for example, journalism award ceremonies, which go towards the accumulation of capital for the journalists. Self-referentiality through awards is important here because in the discursive construction of normative roles, audiences are oftentimes the reference groups (Mellado Citation2020). Research into professional roles has mostly focused on how audiences as reference groups shape how journalists construct their roles (see, among others, Ojala and Pöyhtäri Citation2018). Scholars acknowledge that roles emerge when either certain unconsciously assimilated ideas, beliefs or tasks form a pattern of practice (Coyne Citation1984) or through social interactions (Hellmueller and Mellado Citation2015).

Moreover, in journalism scholarships, there is a tendency to acknowledge roles as defined within social interactions and internalised by journalists within mostly the Anglo-American journalistic cultures, which is widely criticised in the journalism field (Hanitzsch Citation2018; Josephi Citation2005; Nerone Citation2012). The hegemonic model of journalism takes it for granted that in their practice of journalism, news professionals enjoy their autonomy to speak truth to power (Nerone Citation2012). This explains the tendency to, for example, assume the watchdog role must be present across journalistic cultures if journalism is to function as it should. Recent comparative studies into role orientations across journalistic cultures demonstrate that traditional roles like the watchdog role are embraced widely (Hanitzsch et al. Citation2019), but its performance is complex and dependent on multiple factors such as media ownership or political parallelism in specific journalistic cultures.

The role orientations which often lean towards a hegemonic model could also be a product of a dominant journalistic scholarship that often assumes universal applicability. There is an assumption that the democratic model is the lens through which to understand “other” journalism(s) that may exist across global cultures (Baack, Cheruiyot, and Ferrer-Conill Citation2022; Josephi Citation2013). Closely related to this is the thinking that American journalism is the “gold standard” through which other journalisms should be assessed. Such an assumption is problematic considering this US journalistic culture, for example, in the examination of role orientations, is an outlier (Hanitzsch et al. Citation2019). We consider that this “gold-standardism” is tied to the notion of journalism dominance of institutions in Minority World Countries as exemplified in award practices – in this case, that of CNN journalism awards.

Awards in themselves can inculcate exclusionary practices between the “professional” and unprofessional or standard/sub-standard or excellent/mediocre. Awards have been used to legitimise the practices and performance of certain groups of journalists based on their race or allegiance to the state; and in this way, they become objects of control and discrimination (Botma Citation2017; Huang Citation2013). For the most part, generations of correspondents from North America and Europe—mostly responsible for ooga booga or “heart-of-darkness” journalism about Africa—have established and reinforced negative narratives of the continent that are so entrenched globally (Bunce, Franks, and Paterson Citation2017; Hawk Citation1992; Nothias Citation2020; Nothias and Cheruiyot Citation2019). These journalists not only accumulate capital through becoming “experts” of the continent in North American and European capitals but claim journalistic authority through being winners of awards like the American Pulitzer Prize. Effectively, the awards recognising such journalism in Minority World Countries end up legitimising racialised media representations, as “professional” or “quality journalism” (see Nothias Citation2020). Such an “award-driven” notion of good journalism is then taken as the “gold standard” internationally, both in practice and in academia. The field of journalism studies seldom interrogates such fallacies of “professionalism” promoted through international awards from Minority World Countries.

While the awards are considered to lead to uniformity through recognising and appraising journalistic work (Volz Citation2013, 392), they also present a discursive dilemma over what should constitute “excellence” in the practice of journalism. We argue here that there is an urgent need to re-evaluate the notion of journalistic excellence, as defined through the discursive input of journalistic awards, and its implications for professional culture today. In this paper, we are, therefore, guided by the following research question:

RQ2: How do winners of journalism prizes perceive their roles in a discursive space of international award practice?

Lastly, it is important to note that winners’ role orientations (or even performance) cannot be seen to exist within a vacuum as there is interdependence between a variety of actors such as fellow journalists (as peer reviewers), media managers (who steer and fund the production) and the judges, as assessors (Jenkins and Volz Citation2018). Furthermore, award practices need to be placed within the broader commercial logic of journalistic institutions. Scholars have shown how award practice, in for instance the US context, has turned into a “social enterprise” (Volz Citation2013, 393) where prize culture is oriented towards attracting advertising revenue and sponsorship. This “for-profit” agenda of award practice further contributes to the saturation of awards and “prize punditry” (English Citation2002, 109), which drives the cultural (re)production of competitions in society.

Drawn from the potential of both winners and their entries to serve as quality signals (Wellbrock and Wolfram Citation2019) with potential symbolic and economic capital, media managers, editors and reporters invest time and money into the awards. In the process, award practices create tension over a variety of interests within journalism, which leads Jenkins and Volz (Citation2018, 924) to argue that “excellent journalism” is the outcome of negotiations of a variety of ideas of journalism. We explore such tensions in our empirical study.

Method and Context

This study employs qualitative interviews with the view to understand how journalists perceive and interpret the context of their practice (Creswell and Poth Citation2018) as shaped by a prize culture. Specifically, this research is based on in-depth interviews with 14 journalists, the recipients of awards from the “CNN Journalism of the Year” competition (Africa edition) between 1995 and 2016. We have selected journalists as opposed to other actors in the international award practice, such as judges (who operationalise the mission and vision of the award institution) because the perspectives of the news workers are representative of journalism as a profession.

We employed purposive sampling with the specific intention of achieving “loose representation” (Lynch Citation2013) and a special focus on the following characteristic in our sample: that there is a good spread of years during which the respondents won the awards; the journalists chosen won awards in a variety of categories; that all respondents practised journalism after winning the CNN awards; and, most importantly, the respondents are from different parts of Africa.

The representation across the continent is theoretically significant to this study because we sought to understand how excellence and professional roles are perceived in different journalistic cultures represented in the list of award winners. Further, we sought to achieve representation outside English-speaking Africa because, most often, research in journalism studies has a strong, Anglophone bias, leaving other parts of the continent such as Arab-speaking or Francophone Africa understudied (Cheruiyot Citation2021; Frère Citation2012). We however note that as a limitation to the study, this endeavour to achieve representation may conceal disparities in the African media landscape.

Initially, we were only interested in journalists that are still practising journalism in legacy organisations on the continent. However, this proved difficult because most award-winners we contacted (37), have since left the practice. Finding practising journalists was harder especially in countries with fewer winners (see on p. 9). We eventually decided to expand our criteria to include journalists that currently work with peripheral organisations, who are increasingly identified as critical in the expanding news ecology. Further, we included two journalists who had left the news industry within two years from the date of the interview. The journalists interviewed were from Nigeria (2), South Africa (2), Uganda (2), Ghana (1), Malawi (1), Kenya (2), Zambia (1), Egypt (1), Mauritius (1) and Algeria (1). All of them won the CNN prize in different categories between 2002 and 2016. Among the respondents was one who had won the top prize, “CNN African Journalist of the Year Award”. Ten of the journalists were female, and four were male, drawn from both broadcast and print commercial news outlets. At the time of submitting their entries, the respondents served in various roles, for example, producer, general news reporter, news anchor, etc. Post-award, seven of these respondents have remained within journalism and media profession, five have moved on to public relations, and two have doubled up as media entrepreneurs and academics. In addition, all respondents reported more than 10 years or more, of professional journalism experience.

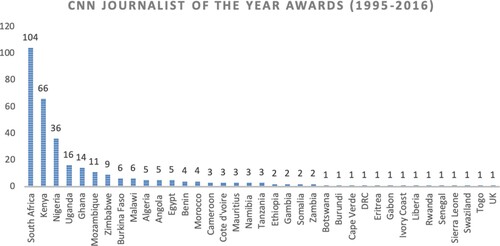

Figure 1. Distribution of winners from 37 countries. Source: edition.cnn.com/WORLD/africa/africanawards/finalists.

Ten semi-structured interviews were conducted virtually, while four were done in-person in 2020 and 2021. Each interview lasted an average of 37 min. The questions focused on the journalists’ views about their winning entries, the award scheme, their view of journalistic practice as award winners, and how they viewed themselves as award-winners in relation to the expectations within and outside the profession, after receiving the awards. The corresponding data were thematically analysed using Dedoose, a qualitative data analysis software.

As all former journalists ourselves, the authors experienced the challenge of “interviewing sideways” i.e., speaking to individuals with whom we have formerly shared a profession. In our data collection, therefore, we occasionally gave back reflexivity to the respondents by requesting them to clarify their views or experiences further, “for the record”, even if we as interviewers were already conversant with the issue we were inquiring about (see Plesner Citation2011).

Our analysis of the implications of the CNN awards was at two levels. The first was how award-winners interpret the notion of “journalistic excellence” as defining their news practices, and the second was on how the CNN awards have shaped how they perceive their roles. In the next section, we provide a brief context of the CNN Awards.

“CNN African Journalist of the Year” Competitions

CNN launched the competition in 1995 to promote recognition of journalists and “excellence in African journalism” (Tropics Citation2011). In the 90s, the competition had a few categories, mostly attracting entries from former British colonies, and in the 2000s, more categories were introduced to make the competitions more inclusive and attract journalists and news organisations in Francophone and Lusophone Africa. The overall prize was the “African Journalist of the Year Award”. By the year 2000, the competitions were receiving more than 1000 entries from across the continent. In 2016, which was the last edition to date, there were 15 categories that included “News Impact, Health & Media”, “Environment, Sports Reporting, Culture”, “Energy & Infrastructure” and “Press Freedom”. There was also the “Portuguese Language Television General News Award”. These suggest a deliberate cognisance of underrepresented beats, and regions (e.g., Lusophone countries). Further, the “Press Freedom Award” went to victims of state repression and harassment which could suggest the awards appreciated the difficult work of journalists on the continent. Most of the nominated and winning entries were investigative news stories (especially those that highlighted corruption, syndicated crimes, or misuse of power) as well as stories about calamities like famine. This could suggest that either there were more entries received around these subjects, or the awards inspired entries that spoke to the African condition (cf. Lugalambi and Schiffrin Citation2018).

CNN was the main organiser and sponsor of the awards until 2005 when MultiChoice Africa, a satellite TV company owned by South Africa’s Naspers Media Group, became its official partner. During the years of the competitions, CNN worked with several corporate partners that sponsored several categories of the competitions: for example, South Africa Broadcasting Corporation (SABC), Ecobank, and the Coca-Cola Company Africa Foundation.

Although the journalism awards have ceased since 2016, they were considered the “most prestigious” on the continent with journalists from North, South, East and West Africa, all represented. However, there were more winners from Anglophone Africa. In the 20 competitions between 1995 and 2016 (they were not held in 1996), a total of 328 journalists and news organisations received the awards. South Africa received the highest (104), while Kenyan journalists won 66 awards. Nigeria won 36 awards, followed by Uganda's 16, Ghana's 14, Mozambique's 11, Zimbabwe's 9, Burkina Faso's 6, and Malawi's 6. Other countries won between 1 and 5 awards. See .

Although South African journalists and news organisations received most of the awards, Kenya was also a constant winner in the competitions, with its journalists winning the overall category, “Africa Journalist of the Year Award” nine out of 20 times, while South Africa had five. Most of the award ceremonies were held in Johannesburg, South Africa, and in other years in cities like Maputo in Mozambique and Nairobi, Kenya. Judges were selected from across the continent and the US. In attendance at the award ceremonies were nominees of the prizes, CNN executives, African leaders like former Kenyan president Uhuru Kenyatta, among others.

Prizes included cash, plaques, and fellowships at CNN headquarters in Atlanta. CNN Journalism of the Year award-winners have gone on to become media executives/managers, correspondents of international media as well as academics, top civil servants, and business leaders in corporate and multinational companies on the continent and beyond.

Findings

In response to our first research question, what do award winners’ self-perceptions of journalistic excellence reveal about international awards practice?, we present the following emerging themes based on the thematic analysis of data: Markers of excellence, Homogeneity of excellence and Rewards of excellence. In the second part, we address the second research question, how do award winners perceive their roles in a discursive space of journalistic awards? Here we explain the following perceived roles of award winners emerging from our analysis: Champions of existing roles, “Missionaries” of excellence, and Representational role.

Markers of Excellence

The general attributes of excellence that our respondents cited included the following: audience-centeredness (stories that directly focus on the needs of the audience); compelling nature (a story with an edge or out of the ordinary); competitiveness (aspects that make a nominee and the entry stand out from their peers); impact (the perceived change a story could bring e.g., exposing grand theft of public resources); novelty (the newness of a story idea); positivity (optimism in a story or a story attribute that spurs positive emotions); professional (the cumulative effort to meet and exceed traditional journalistic standards); innovativeness (the effort to incorporate various technologies to achieve better news presentation e.g., creative data visualisation in story telling); rigour (meticulousness and the general effort such as time or resources, invested towards successful storytelling); depth (the level of detail and thoroughness of the story); courage (bold approach to storytelling especially through challenging governments or long-held cultural practices); and risk factor (risks involved in investigative work e.g., publishing an exposé despite state surveillance or arrests).

In our case, however, there were nuances to these traditional attributes of excellence (see Shapiro, Albanese, and Leigh Citation2006). The attribute of journalism that stood out in our interviews was the “African factor” in a winning story, to which our respondents implied the level of localisation of a winning entry. To some respondents, this meant the extent to which a story was “authentically African” (Mauritius Winner #1), an element that we found as vague and based on individual perceptions. Some of the examples included entries that depicted social and political tensions or stories of resilience in everyday life, like a story which exposed a dubious link between a murderous vigilante and local politicians. Oftentimes, respondents conflated African “authenticity” with impact through journalism, as this award-winner expressed it:

You do all the stories, and you expose all the corruption. You talk about press freedom, civil liberties, all of those things, and nothing changes. But it's the little thing that you have created—some form of consciousness in the minds of people, and then it has triggered knowledge. (Nigeria Winner #2)

I don't believe we read enough stories about people in African countries getting things right, doing cool things, and being at the cutting edge of science in a certain field. (South Africa Winner #1)

Homogeneity of Excellence

The claim to identify common criteria for the measurement of excellence suggests the standardisation of attributes of good journalism. According to the respondents, the continental award practice overlooked the varieties of journalisms within the continent and the assumed values or standards of journalism. For example, the number of awards to mostly journalists from Anglophone Africa (like Kenya, South Africa, and Nigeria) suggests professionals from these regions would most likely meet the awards criteria. At the same time, according to the respondents, entries from other regions, for example, Arab-speaking Africa, like Egypt and Algeria, had to at least attempt to fit into the “format of journalism” (in the words of an award winner from Egypt) practised in the English-speaking regions.

As mentioned before, the awards placed emphasis on “Pan-African” journalism, which to our respondents mostly implied a continental understanding of one standard of journalism. While it may have been perceived to be biased towards Anglophone Africa and the resource-rich journalistic cultures like Kenya and South Africa, the awards were still seen as diverse in comparison to national or regional awards on the continent that are critiqued over ethnic, gender or racial bias (see Botma Citation2017).

Moreover, the contention over what a “true African story” (South Africa Winner #2) meant seems to also question the meaning of excellence as promoted through the CNN award practice. We see the conceptions of excellence as fitting into two prisms. First, is the sense in which the CNN awards manifest a similar nature of quality or good journalism, but at the same time appear to reinforce a strong Anglo-American view of excellence. To give an example, from the respondents’ perspective, the awards suggested that winning entries had to appeal to the audiences of Minority World Countries to be considered compelling. One of the journalists expressed it this way:

The one or two times that they had awards for science and tech stories, they (CNN) highlighted work done in South Africa on something as arcane as ocean robots. No one was talking about the story of a Zimbabwean researcher who spent his whole life trying to monitor how a river floods in order to save communities’ livelihoods because that's not sexy science. (South Africa Winner #1)

Rewards of Excellence

Awards fall short as indicators of journalistic excellence when the focus is on the rewards. In the view of our respondents, excellence represents the functioning of journalism as it should be, but awards are “side attractions” (Ghana winner #1) or “bonus” (Algeria winner #1). However, the awards came with forms of professional capital, including promotions, better chances for professional mobility (a “CV boost,” according to the Malawian award winner), invitations to prestigious local and international award juries, nominations for influencer positions like the top “women to watch” lists, celebrity statuses, or success in grant applications.

Professionally, the respondents were more inclined towards the capital they accumulate within the profession. But it is also important to highlight how that capital could be converted to other forms like network capital when this leads to more sources or international collaborative work with other journalists, or economic capital. For example, one of the winners went on to start her own newspaper, currently a leading daily in her country.

Journalistic Roles of Award Winners

CNN Africa Journalist of the Year Award winners perceived their post-award roles in multiple ways. Largely, we consider that the roles they exemplified were mostly about enhancing the normative roles, but our findings also show that alternative roles emerged as they acquired new statuses within their journalistic cultures. From our data, therefore, we identified the following three dimensions of role orientations through international award practice: champions of existing roles, “missionaries” of excellence, and representational roles.

Champions of Existing Roles

Award-winners largely consider their roles as those of enhancing the traditional roles of journalism both as considered within political and everyday life, for example, the watchdog role. Even so, awards in themselves were sometimes hindrances to performing normative roles when the zeal to accumulate symbolic capital overshadowed professional goals. In the interviews, our respondents expressed the tensions between the aspirations to meet the criteria of award-winning entries and the normative expectations of the profession. For example, according to this award winner:

If these (awards) would become the main focus of your work, then you fail to do what you are supposed to do as a journalist, especially in terms of holding government officials and everyone accountable. Our primary job is to educate, inform and entertain. At the end of the day, whatever you do, awards are a just that: a plus. Besides, you can imagine the millions of journalists who do not submit their work for any awards, yet their stories are having impact, and making changes wherever they are. (Ghana Winner #1)

“Missionaries” of Excellence

The award winners imagine themselves as purveyors of “high standards” of journalism within the profession. In the following extract, the award winner describes the “mission” towards journalism in spiritual terms, which suggests not only the function of awards in promoting journalistic authority and professionalisation, but also the fluidity of journalism as a profession:

The award was a sign from God that I was on the right track in my career bearing in mind I was not a trained journalist. The award boosted my reputation at my workplace and thus my suggestions moving forward were taken more seriously. The award came with a small training package that opened my eyes to the next level of journalism. (Kenya Winner #1)

Mentor

As mentors, these journalists saw their role as that of guiding fellow journalists towards achieving “high standards” of journalism. The goal here is, therefore, to empower their peers through sharing useful tips and techniques of doing excellent journalism.

Model

The award-winners considered themselves as best examples of outstanding practices in journalism. The winning entries of our respondents were used as examples through which their peers would attempt to model their own work. The award winners viewed themselves as examples of the “best that journalism has to offer” (Mauritius Winner #1) to the profession and society.

Motivator

The journalists perceived their role as that of inspiring and motivating their peers, especially the young and inexperienced journalists. Given that winners view their awards as the pinnacle of professional validation, this is understandable. Closely related to the mentor role, motivation was mostly about how the win represented what their peers could achieve as well.

Appraiser

As appraisers or peer reviewers, award winners aimed to provide specific criteria for best journalistic practices. After the awards, some of the respondents took on editorial production roles where they served as reviewers or gatekeepers of their peers’ work. They also participated in brainstorming session for story ideas and even pre-judged proposed entries for the CNN awards in their newsrooms.

The Representational Role

Apart from the prestige associated with CNN through the awards, this news organisation further provided the impetus to spotlight journalism within the continent. Our findings show that this goal of the award and the award giver/sponsor are interdependent in shaping the perceived roles of the winners. Journalists, therefore, saw their role as representational in two ways. First, as the journalists in the spotlight within and outside the profession for their outstanding “Pan-African” journalistic products, they considered themselves examples of exceptional journalistic practices. Representation, in this sense, has to do with showing what journalism on the continent looks like, but also within the specific journalistic cultures of the winners themselves. While the representational role emphasises the celebration of the journalists and their achievements, there is the risk that it breeds celebritisation of the professionals. The second perspective to this representational role emerged from how the respondents expressed their roles of telling “truly African stories” or showing “another side of Africa” (South Africa winner #2). When we asked how she perceived the significance of CNN as the award giver, a winner in Uganda expressed it this way:

I felt, while it was a chance for us to be recognised as African journalists, it was also the time for us to educate CNN and the Western media about Africa, about true Africa. (Uganda winner #2)

Discussion

In evaluating the conceptualisations of excellence in international award practice, we surmise from our findings that, discursively, excellence as defined through CNN award practice and its mission through the prize, presented the news professionals with tensions over journalistic standards fit for a “monolithic” Africa. Our analysis show that the awards inevitably promoted generalised visions of excellence in journalism. The attributes of excellence that the award winners mentioned such as audience-centeredness, compelling nature, novelty, innovativeness, rigour and depth largely conform to findings from previous studies, for example, Shapiro, Albanese, and Leigh (Citation2006) in evaluating what judges of journalism awards consider as important. This implies that, largely, the perspective of journalists and that of judges align, and this could be because award schemes set the criteria for winning entries and journalists are socialised into these standards, which inadvertently could also shape their journalistic practice. Indeed, what we draw from the interviews is that the career journalists’ conceptualisations of excellence point to a professional consensus built over time based on the criteria for the CNN competitions as well as juries’ public statements/decisions and citations.

Furthermore, our findings reveal tensions over the understanding of excellence based on what journalists consider to be the most important markers of excellence. For example, what the journalists referred to as “African factor” in winning entries was the implied authentic nature of storytelling in capturing the social, cultural, and political conditions of the continent. The varied interpretations of authenticity of an “African story” as an attribute of excellence could suggest tensions in professional ideologies (Waisbord Citation2013) that arise when the international awards practice of CNN seeks to homogenise journalism. Similar to authenticity is the constructiveness of a journalistic piece. Ideas about constructive approaches to reporting, while they have become popularised globally in recent years, through training and journalistic fellowships, are not necessarily alien to traditional journalism on the continent (Kasoma Citation1996, for example, recognises constructivity through “Afri-ethics”). However, the liberal model of journalism that emphasises the watchdog role promotes coverage of the abuse of power through, for example, consistent news coverage of corruption in African countries. Seen from a broader perspective, these tensions over what excellence could mean to professional journalism suggest the CNN award winners engage in “post-colonial reflexivity” (Nothias Citation2020) through their awareness of the image that the international news coverage of Africa conjures. While it was a major sponsor of the global award scheme, CNN's global influence—sometimes referred to as “CNN effect/factor” (Hawkins Citation2002; Robinson Citation2005)—presents a paradox. In Africa, in particular, CNN is considered a promoter of best practices in reporting through the awards, but at the same time, a perennial transgressor through its coverage that reinforces myths and stereotypes (see, among others, Bunce, Franks, and Paterson Citation2017; Kalyango Citation2011).

When it comes to the self-perception of award-giving procedures as a representation of journalism excellence, our findings largely showed that prizes reinforce already existing journalistic roles, but news professionals acquire new ones when their statuses change to award winners. The shift in role perception could be expected given that awards elevate and validate their professional status among their peers and news organisations, but it also legitimises their professional authority and credibility. In addition, winning the awards affirm their expertise among their peers and their audiences. The calibration of role perceptions resonates with previous research on journalism awards (see Jenkins and Volz Citation2018; Volz Citation2013), which found that winning awards confers forms of symbolic capital and therefore elevates journalists’ authority as professionals and their expertise. Furthermore, the symbolic capital through awards spotlights and reinforces the normative role expectations (Dong Citation2013).

The promotion of existing roles in a post-award dispensation is not unusual, granted that journalists worldwide have typically perceived their primary roles within an ideological framework of democracy. Under this framework, journalism as practised in democratic societies, has a responsibility to supply the citizenry with information, inclusive of diverse opinions and to expose misconduct (Asp Citation2007). This information should be objective and accurate, helping citizens make rational and informed choices (McNair Citation2009, 238–240). Roles that concern public accountability and speaking truth to power are mostly embraced around the world (Hanitzsch et al. Citation2011). Thus, as active promoters of “watchdog” journalism, award winners embrace a “critical” role of journalism, whose main purpose is to proactively scrutinise and hold to account political and business leaders (Hanitzsch and Vos Citation2018). In the African journalistic cultures, this role perception reflects a professionalisation of journalism that has largely possibly been shaped by a curriculum from the US and Europe (Umejei Citation2018). However, the enactment of this role carries with it several risks to journalistic safety.

Our findings also revealed that as award winners, the journalists perceive themselves as missionaries of excellent journalism. The missionary role manifests itself in four dimensions, i.e., mentor, model, motivator, and appraiser. In previous studies, when journalists have been termed as “missionaries”, they have considered their professional identity as being critical to promoting certain values or visions of the world (Hanitzsch and Vos Citation2018; Köcher Citation1986). As award winners, they indeed still champion values they consider important to their national cultures, e.g., development or social change as we mentioned earlier. However, they believe that they have been bequeathed a “new mission” to transform the profession as “bearers of excellence”.

In essence, the missionary role suggests that award winners’ referentiality is both internal (to peers) and external (audiences). What the awards do is foster personal motivation (Hanitzsch and Vos Citation2018) whilst also conferring journalistic authority to the individual, and at same time, their own news practice. In the audience approach to journalistic roles, the mentor role is identified as a sub-dimension to the service role, where journalists perceive the audience as clients (Roses and Humanes Citation2020). In this role, the award winners consider themselves as being in service to excellence through their obligation to their peers. The appraiser role resonates with the intended outcome of professional awards, which is to identify and reward best practices in the field (Volz Citation2013). Winning the award positions the journalists as experts and earns them the right to evaluate and judge the work of their peers.

What we note as well is that the award winners perceive roles as operationalising the supposed “high” standards as exemplified through international media practices such as that of CNN. International news organisations are often critiqued for robbing their African audiences of their agency through negative portrayal of the continent. Our respondents showed an awareness of the production of racialised (mis)representations in media like CNN. And while this representational role is not necessarily about indicting CNN, it is more about “correcting” the images and “reforming” CNN by showing that “locally-produced” journalism could be different.

Conclusion

This article has interrogated the post-award imaginaries and implications of the CNN international award practice. The empirical data was drawn from qualitative interviews with CNN award-winners based in Arab-speaking, Francophone, Lusophone, and Anglophone countries in Africa. Our results point to an understanding of excellence and roles performed by winning journalists that is fluid based on individual, institutional, and professional ideas of outstanding journalistic practice within national cultures.

Award winners essentially champion existing roles as opposed to reinventing new ones. This is not unusual, granted that the performance of those roles in part contributes to their award. It is, therefore, expected that they would then “play up” those roles or even “excel” in them in their news practice. Thus, the roles identified in previous studies can be presented independent of each other, but they are not mutually exclusive as award winners can perceive, enact, or perform multiple roles at the same time. It is appreciated in existing research that roles are fluid and could shift social, cultural, technological or political situations influencing journalism; for example, during periods of health crises (Klemm, Das, and Hartmann Citation2017); or as a result of technological disruptions (Mellado and Hermida Citation2021). It could be argued, therefore, that when journalists acquire new statuses, their role perception shifts, but in the case of award practices, this does not necessarily mean they abandon their traditional roles.

Moreover, we surmise from the findings that international award practices promote universalist visions of journalism or even cosmopolitan views of journalism (Reese Citation2001), but they in no way establish a common professional culture (Hanitzsch Citation2007). Global culture has fostered the possible rise of “cosmopolite” or global journalist – with a common vision of transnationalised practices and visions of journalism (Reese Citation2001, 178); a trend that over the years has been reinforced through the rise of networked technologies (Heinrich Citation2011). However, the understanding of excellence could suggest “counterhegemonic articulations” of journalism (Hanitzsch Citation2007, 370). Journalists we interviewed consider their role as agents of “Pan-African journalism”, which implies a monolithic idea of journalism(s) on the continent as promoted through the awards. However, “Pan-African journalism” also stands for “alternative excellent journalism” in place of the Anglo-American cultural hegemony that CNN represents through a post-colonial critique of the news organisation's culture of accentuating negative tropes and racial stereotypes in reporting about Africa.

Finally, this research contributes to journalism studies by assessing the post-award role perceptions of award-winners and how the journalists reflect on and discursively define excellence in a precarious period for journalism. Through the lens of journalistic cultures (Hanitzsch Citation2007), this study further highlights the tensions that emerge over an idealised perspective of professional journalism through award practices.

As a limitation of this study, it is important to clarify that while it is anticipated that most journalists across different journalistic cultures would acknowledge similar roles, such as the watchdog role, it should not be assumed that the performance of this role would be universal. Hellmueller and Mellado (Citation2015) remind us that context-specific dynamics that may shape the way journalism is performed in different cultures might reveal more differences than is often assumed in scholarly works, mostly from the Minority World Countries. Secondly, and as already suggested, it is necessary for future studies to assess exactly how the roles that award winners conceptualise are performed. It is the gap between role conceptualisation and performance that can reveal how awards actually shape journalism (cf. Hellmueller and Mellado Citation2015).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Chikezie Uzuegbunam, Sandra Banjac, Raul Ferrer-Conill, Brian Ekdale, Edson Tandoc, anonymous reviewers and editors for their valuable feedback throughout the development of this paper. We would also like to say to the many award-winning journalists from across Africa, who made time to speak to us: Asante sana!

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 In this article, “Minority World Countries” refers to North America, Europe, and Australasia, while “Majority World Countries” is used in reference to Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East. In journalism studies, these concepts are increasingly being used in place of the “Global North” and “Global South” owing to their inaccurate description of the epistemological dominance of the former.

2 A case in point is that of Darnella Frazier, who received the American Pulitzer Prize in 2021 for recording a video of the police murder of African-American George Floyd, which stirred global protests.

References

- Asp, Kent. 2007. “Fairness, Informativeness and Scrutiny: The Role of News Media in Democracy.” Nordicom Review 28 (Jubilee Issue): 31–49.

- Baack, Stefan, David Cheruiyot, and Raul Ferrer-Conill. 2022. “Journalism is not a one-way Street: Recognizing Multi-Directional Dynamics.” In The Institutions Changing Journalism: Barbarians Inside the Gate, edited by Patrick Ferrucci, and Scott A. Eldridge, 103–117. Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Routledge.

- Banjac, Sandra. 2022. “An Intersectional Approach to Exploring Audience Expectations of Journalism.” Digital Journalism 10 (1): 128–147. doi:10.1080/21670811.2021.1973527.

- Beam, Randal A., Sharon Dunwoody, and Gerald M. Kosicki. 1986. “The Relationship of Prize-Winning to Prestige and Job Satisfaction.” Journalism Quarterly 63 (4): 693–699. doi:10.1177/107769908606300403.

- Biddle, Bruce J. 1979. Role Theory: Expectations, Identities, and Behaviors. New York: Academic Press.

- Bogart, Leo. 2004. “Reflections on Content Quality in Newspapers.” Newspaper Research Journal 25 (1): 40–53. doi:10.1177/073953290402500104.

- Botma, Gabriël J. 2017. “Cultural Capital and the Distribution of the Sensible: Awarding Arts Journalism in South Africa (2013–2014).” Journalism Studies 18 (2): 211–227. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2015.1046996.

- Bourdieu, P. 1986. “The Forms of Capital.” In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by John Richardson, 241–258. New York: Greenwood.

- Bowe, Brian J., Carolyn Nielsen, Arwa Kooli, Rafia Somai, and Joe Gosen. 2021. “After the Revolution: Tunisian Journalism Students and a News Media in Transition.” Journalism, , Advance online publication. doi:10.1177/14648849211018942.

- Bunce, Melanie, Suzanne Franks, and Chris Paterson. 2017. Africa's Media Image in the 21st Century: From the “Heart of Darkness” to “Africa Rising”, Communication and Society. London; New York: Routledge.

- Carlson, Matt. 2017. Journalistic Authority: Legitimating News in the Digital era. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Cheruiyot, David. 2021. “The (Other) Anglophone Problem: Charting the Development of a Journalism Subfield.” African Journalism Studies 42 (2): 94–105. doi:10.1080/23743670.2021.1939750.

- Coddington, Mark, Seth C. Lewis, and Valerie Belair-Gagnon. 2021. “The Imagined Audience for News: Where Does a Journalist’s Perception of the Audience Come from?” Journalism Studies 22 (8): 1028–1046. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2021.1914709.

- Coulson, David C. 1989. “Editors’ Attitudes and Behavior Toward Journalism Awards.” Journalism Quarterly 66 (1): 143–147. doi:10.1177/107769908906600119.

- Coyne, Margaret U. 1984. “Role and Rational Action.” Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 14 (3): 259–275. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5914.1984.tb00497.x.

- Creswell, John W., and Cheryl N. Poth. 2018. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. 4th ed. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Dong, Dong. 2013. “Legitimating Journalistic Authority under the State's Shadow: A Case Study of the Environmental Press Awards in China.” Chinese Journal of Communication 6 (4): 397–418. doi:10.1080/17544750.2013.845110.

- English, James F. 2002. “Winning the Culture Game: Prizes, Awards, and the Rules of Art.” New Literary History 33 (1): 109–135.

- Frère, Marie-Soleil. 2012. “Perspectives on the Media in ‘Another Africa’.” Ecquid Novi: African Journalism Studies 33 (3): 1–12. doi:10.1080/02560054.2012.732218.

- Hanitzsch, Thomas. 2007. “Deconstructing Journalism Culture: Toward a Universal Theory.” Communication Theory 17 (4): 367–385. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2007.00303.x.

- Hanitzsch, Thomas. 2018. “Journalism Studies Still Needs to fix Western Bias.” Journalism 20 (1): 214–217. doi:10.1177/1464884918807353.

- Hanitzsch, Thomas, Folker Hanusch, Claudia Mellado, Maria Anikina, Rosa Berganza, Incilay Cangoz, Mihai Coman, et al. 2011. “Mapping Journalism Cultures Across Nations: A Comparative Study of 18 Nations.” Journalism Studies 12 (3): 273–293. doi:10.1080/1461670x.2010.512502.

- Hanitzsch, Thomas, and Tim P. Vos. 2018. “Journalism Beyond Democracy: A new Look Into Journalistic Roles in Political and Everyday Life.” Journalism 19 (2): 146–164. doi:10.1177/1464884916673386.

- Hanitzsch, Thomas, Tim P. Vos, Olivier Standaert, Folker Hanusch, Jan Fredrik Hovden, Liesbeth Hermans, and Jyotika Ramaprasad. 2019. “Role Orientations: Journalists’ Views on Their Place in Society.” In Worlds of Journalism: Journalistic Cultures Around the Globe, edited by Thomas Hanitzsch, Folker Hanusch, Jyotika Ramaprasad, and A. S. De Beer, 161–198. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Hawk, Beverly G. 1992. Africa's Media Image. New York: Praeger.

- Hawkins, Virgil. 2002. “The Other Side of the CNN Factor: The Media and Conflict.” Journalism Studies 3 (2): 225–240. doi:10.1080/14616700220129991.

- Heinich, Nathalie. 2009. “The Sociology of Vocational Prizes: Recognition as Esteem.” Theory, Culture & Society 26 (5): 85–107. doi:10.1177/0263276409106352.

- Heinrich, Ansgard. 2011. Network Journalism: Journalistic Practice in Interactive Spheres. New York: Routledge.

- Hellmueller, Lea, and Claudia Mellado. 2015. “Professional Roles and News Construction: A Media Sociology Conceptualization of Journalists’ Role Conception and Performance.” Communication & Society 28 (3): 1–11.

- Huang, Shun-Shing. 2013. “From Control to Autonomy? Journalism Awards and the Changing Journalistic Profession in Taiwan.” Chinese Journal of Communication 6 (4): 436–455. doi:10.1080/17544750.2013.845234.

- Jenkins, Joy, and Yong Volz. 2018. “Players and Contestation Mechanisms in the Journalism Field: A Historical Analysis of Journalism Awards, 1960s to 2000s.” Journalism Studies 19 (7): 921–941. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2016.1249008.

- Josephi, Beate. 2005. “Journalism in the Global age: Between Normative and Empirical.” Gazette (Leiden, Netherlands) 67 (6): 575–590. doi:10.1177/0016549205057564.

- Josephi, Beate. 2013. “De-coupling Journalism and Democracy: Or how Much Democracy Does Journalism Need?” Journalism 14 (4): 441–445. doi:10.1177/1464884913489000.

- Kalyango, Yusuf, Jr. 2011. “Critical Discourse Analysis of CNN International's Coverage of Africa.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 55 (2): 160–179.

- Karlsson, Michael, and Christer Clerwall. 2018. “Cornerstones in Journalism: According to Citizens.” Journalism Studies 20 (8): 1184–1199. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2018.1499436.

- Kasoma, Francis P. 1996. “The Foundations of African Ethics (Afriethics) and the Professional Practice of Journalism: The Case for Society-Centred Media Morality.” African Media Review 10 (3): 93–116.

- Kivikuru, U. 2009. “From an Echo of the West to a Voice of its own? Sub-Saharan African Research Under the Loophole.” Nordicom Review 30 (Jubilee): 187–195.

- Klemm, Celine, Enny Das, and Tilo Hartmann. 2017. “Changed Priorities Ahead: Journalists’ Shifting Role Perceptions When Covering Public Health Crises.” Journalism 20 (9): 1223–1241. doi:10.1177/1464884917692820.

- Köcher, Renate. 1986. “Bloodhounds or Missionaries: Role Definitions of German and British Journalists.” European Journal of Communication 1 (1): 43–64. doi:10.1177/0267323186001001004.

- Kristensen, Nete Norgaard, and Mette Mortensen. 2017. “Self-referential Practices in Journalism: Metacoverage and Metasourcing.” In The Routledge Companion to Digital Journalism Studies, edited by Bob Franklin, and Scott A. Eldridge, 274–284. London; New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Lanosga, Gerry. 2014. “The Power of the Prize: How an Emerging Prize Culture Helped Shape Journalistic Practice and Professionalism, 1917–1960.” Journalism 16 (7): 953–967. doi:10.1177/1464884914550972.

- Lough, Kyser. 2021. “Judging Photojournalism: The Metajournalistic Discourse of Judges at the Best of Photojournalism and Pictures of the Year Contests.” Journalism Studies 22 (3): 305–321. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2020.1867001.

- Lugalambi, George William, and Anya Schiffrin. 2018. African Muckraking: 75 Years of Investigative Journalism from Africa. Chicago: Jacana Media.

- Lynch, Julia F. 2013. “Aligning Sampling Strategies with Analytic Goals.” In Interview Research in Political Science, edited by Mosley Layna, 31–44. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Mabweazara, Hayes Mawindi, and Admire Mare. 2021. Participatory Journalism in Africa: Digital News Engagement & User Agency in the South, Disruptions: Studies in Digital Journalism. New York: Routledge.

- McNair, Brian. 2009. “Journalism and Democracy.” In The Handbook of Journalism Studies, edited by Karin Wahl-Jorgensen, and Thomas Hanitzsch, 237–249. New York: Routledge.

- Mellado, Claudia. 2020. “Theorizing Journalistic Roles.” In Beyond Journalistic Norms: Role Performance and News in Comparative Perspective, edited by Claudia Mellado, 22–45. London: Routledge.

- Mellado, Claudia, and Alfred Hermida. 2021. “The Promoter, Celebrity, and Joker Roles in Journalists’ Social Media Performance.” Social Media + Society 7 (1): 2056305121990643. doi:10.1177/2056305121990643.

- Nerone, John. 2012. “The Historical Roots of the Normative Model of Journalism.” Journalism 14 (4): 446–458. doi:10.1177/1464884912464177.

- Nölleke, Daniel, Folker Hanusch, and Phoebe Maares. 2022. “The Ambivalence of Recognition: How Awarded Journalists Assess the Value of Journalism Prizes.” Journalism, Advance online publication. doi:10.1177/14648849221109657.

- Nöth, Winfried. 2007. “Self-referential Media: Theoretical Frameworks.” In Self-reference in the Media, edited by Winfried Nöth, and Nina Bishara, 3–29. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Nothias, Toussaint. 2020. “Postcolonial Reflexivity in the News Industry: The Case of Foreign Correspondents in Kenya and South Africa.” Journal of Communication 70 (2): 245–273. doi:10.1093/joc/jqaa004.

- Nothias, Toussaint, and David Cheruiyot. 2019. “A “Hotbed” of Digital Empowerment? Media Criticism in Kenya Between Playful Engagement and co-Option.” International Journal of Communication 13 (2019): 136–159.

- Ojala, Markus, and Reeta Pöyhtäri. 2018. “Watchdogs, Advocates and Adversaries: Journalists’ Relational Role Conceptions in Asylum Reporting.” Media and Communication 6 (2): 11. doi:10.17645/mac.v6i2.1284.

- Örnebring, Henrik, and Anna Maria Jönsson. 2004. “Tabloid Journalism and the Public Sphere: A Historical Perspective on Tabloid Journalism.” Journalism Studies 5 (3): 283–295. doi:10.1080/1461670042000246052.

- Pallas, Josef, Linda Wedlin, and Jaan Grünberg. 2016. “Organizations, Prizes and Media.” Journal of Organizational Change Management 29 (7): 1066–1082. doi:10.1108/JOCM-09-2015-0177.

- Plesner, Ursula. 2011. “Studying Sideways: Displacing the Problem of Power in Research Interviews With Sociologists and Journalists.” Qualitative Inquiry 17 (6): 471–482. doi:10.1177/1077800411409871.

- Reese, Stephen D. 2001. “Understanding the Global Journalist: A Hierarchy-of-Influences Approach.” Journalism Studies 2 (2): 173–187. doi:10.1080/14616700118394.

- Robinson, Piers. 2005. “The CNN Effect Revisited.” Critical Studies in Media Communication 22 (4): 344–349. doi:10.1080/07393180500288519.

- Roses, Sergio, and María Luisa Humanes. 2020. “Audience Approach: The Performance of the Civic, Infotainment, and Service Roles.” In Beyond Journalistic Norms: Role Performance and News in Comparative Perspective, edited by Claudia Mellado, 125–144. London: Routledge.

- Schapals, Aljosha Karim, Phoebe Maares, and Folker Hanusch. 2019. “Working on the Margins: Comparative Perspectives on the Roles and Motivations of Peripheral Actors in Journalism.” Media and Communication 7 (4): 12. doi:10.17645/mac.v7i4.2374.

- Shapiro, Ivor, Patrizia Albanese, and Doyle Leigh. 2006. “What Makes Journalism “Excellent”? Criteria Identified by Judges in two Leading Awards Programs.” Canadian Journal of Communication 31 (2): 425–445. doi:10.22230/cjc.2006v31n2a1743.

- Shepard, Alicia. 2000. “Journalism’s Prize Culture.” American Journalism Review 22 (3): 23–31.

- Tropics. 2011. “About the “CNN African Journalist of the Year Competition”.” Tropics Magazine, Last Modified January 27. Accessed April 20. http://tropicsmagazine.over-blog.com/article-about-the-cnn-african-journalist-of-the-year-competition-65880324.html

- Umejei, Emeka. 2018. “Hybridizing Journalism: Clash of two “Journalisms” in Africa.” Chinese Journal of Communication 11 (3): 344–358. doi:10.1080/17544750.2018.1473266.

- Volz, Yong. 2013. “Journalism Awards as a Site of Contention in the Field of Journalism.” Chinese Journal of Communication 6 (4): 391–396. doi:10.1080/17544750.2013.854820.

- Volz, Yong Z., and Francis L. F. Lee. 2013. “What Does it Take for Women Journalists to Gain Professional Recognition? Gender Disparities among Pulitzer Prize Winners, 1917-2010.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 90 (2): 248–266. doi:10.1177/1077699013482908.

- Waisbord, Silvio R. 2013. Reinventing Professionalism: Journalism and News in Global Perspective. Cambridge: Polity.

- Weber, Matthew S., and Allie Kosterich. 2018. “Coding the News: The Role of Computer Code in Filtering and Distributing News.” Digital Journalism 6 (3): 310–329. doi:10.1080/21670811.2017.1366865.

- Wellbrock, Christian-Mathias, and Marvin Wolfram. 2019. “Effects of Journalism Awards as Quality Signals on Demand.” Journalism 22 (10): 2531–2547. doi:10.1177/1464884919876223.

- Willig, Ida. 2013. “Newsroom Ethnography in a Field Perspective.” Journalism 14 (3): 372–387. doi:10.1177/1464884912442638.