ABSTRACT

Journalism is presented as fundamental to democratic accountability in that news media are both able and expected to hold power to account. Such normative expectations, which justify the protections given journalists and news media, are most frequently studied with regards to state power as the natural object of press scrutiny. This article reports on a successful effort to conduct a replicable analysis of a paradigmatic case of corporate power, the UK chicken meat production industry, that asked whether and how newspapers hold corporate power to account. The analytic framework that we developed to support our two-stage framing analysis decomposed accountability into problematization, causal interpretation and attributions of responsibility, thus allowing us to systematically describe how newspapers shape the public debates in a large heterogeneous dataset. We examined a census of relevant articles from seven UK outlets published between 1985 and 2016 (N = 766). While we were pleased to find that our method, if labor intensive, was fully workable, we were concerned to find that media practice was not compatible with holding corporate power to account. These findings raise serious concerns at the levels of this case, for media practice and for media scholarship.

Journalism is fundamental for democratic accountability (Bovens, Schillemans, and Goodin Citation2014; Norris Citation2014), and defended as “an independent watchdog, a monitor of unchecked power, a tribune of the people, a defender of the weakest, a fourth estate, a public sphere” (Fenton Citation2019, 36). State and government are most often presented as the locus of power, so the government is frequently identified as the primary enemy of freedom (Christians et al. Citation2010), and the natural object for press scrutiny (Curran Citation2005). While argued also to be important, far less attention is paid by the press to the power exercised by the private sector (Hanitzsch et al. Citation2019) and is arguably part of the normative core of the journalistic profession. Critical theorists argue that news media’s failure to systematically tackle corporate power is more than a side effect of their focus on state power: it is structural (Curran and Seaton Citation2002; Fenton Citation2010; Freedman Citation2014).

The standards to which media are held in democratic societies (Callaghan and Schnell Citation2001) attract diverse empirical investigations, (e.g., Carson (Citation2014), Hallin and Mellado (Citation2018)), but fewer ask after the extent to which practice meets these ideals (Mellado and Van Dalen Citation2017). Consistently with the traditional liberal theory of the free press (Curran Citation2005), most peer studies build on a notion of accountability grounded on the watchdog role, and consequently focus their attention on political power. When it comes to normative expectations of media practice with respect to corporate power, we lack even consensus on the definition let alone their operationalization (Porenta Citation2019). The lack of consensus handicaps our ability to even describe whether news media support corporate accountability.

Journalism scholarship has long paid attention to the mechanisms by which media, in particular investigative journalism, hold power to account (Wahl-Jorgensen and Hunt Citation2012). Studies of the role of media in accountably, predictably, frequently focus exclusively on investigative journalism (e.g., Stetka and Örnebring (Citation2013), Waisbord (Citation2000)). Rao (Citation2008) for example, starts their definition of accountability as revealing information after extensive and close scrutiny. However, this focus highlights some types of journalism at the expense of others (Hanusch Citation2019). Focusing analyses solely on investigative reporting produces insights relevant for researchers seeking to understand select media practices, but does not meet the requirements for studies on the role of media in setting agendas (Scheufele and Tewksbury Citation2007). Research on agenda requires consideration of the full spectrum of media practice. Consistent with recognition of power as context-shaping (Hay Citation1997), we hold that discussions of the extent to which the fora created by news media support corporate accountability require balanced consideration of the full set of media behaviors on a given topic.

In this study we propose and successfully operationalize an analytical framework that permits examination of the full set of media behavior relevant to a given topic. Inspired by the framing and accountability literature, our operationalization allows us to systematically describe how the framing of issues in diverse reporting formats shapes the range and quality of the arguments that inform public debate (D'angelo Citation2002; Kristiansen, Painter, and Shea Citation2021), thus shaping the field that delimits subsequent actions. The action of interest to us, and for which our analysis is structured, is accountability. Our operationalization, therefore, decomposes accountability into problematization, causal interpretation and attributions of responsibility. By so decomposing accountability, it is possible systematically to describe how newspapers shape public debates in a large heterogeneous dataset in a manner consistent with an understanding of power as context-shaping (Hay Citation1997).

We chose to focus our study on food production chains as that sector supports generalization to corporate power more broadly (Clapp and Fuchs Citation2009; Opel, Johnston, and Wilk Citation2010). Food production is also of intrinsic interest for the increasing entanglements of food production systems with issues such as climate change, biodiversity, infectious diseases and antimicrobial resistance. Within food production, we chose industrialized chicken as that is paradigmatic (Boyd Citation2001). In UK, this industry exhibits high levels of integration and concentration (Jackson, Ward, and Russell Citation2010), making it recognizable to outsiders, it is the site of very well publicized contaminations, which demands media attention, and there is and was a great deal of relevant scientific literature, which provided the press with all the evidence needed for them to step forward and meet our expectations.

We chose to study this industry in the UK as that is the formative context within which normative expectations of news media were shaped. The concern over the depressed watchdog role has been argued to have a decidedly Western and, more specifically, Anglo-American normative underpinning (Stetka and Örnebring Citation2013). UK broadsheets continue to be exemplars (Cushion et al. Citation2018; Langer and Gruber Citation2020), with a proven track record (Felle Citation2016), and justified pride in their inquisitorial and reporting skills (Blumler and Esser Citation2019). British newspapers and the chicken meat production industry in the UK provide the intersection most favorable for detection of practice consistent with normative expectations that media hold power to account.

At the outset of our study we recognized that, for the media to meet their normative expectations, they must first describe corporate power in ways that are compatible with accountability. Therefore, this study sought to answer the following research question: Was media speakers’ framing of the chicken meat production industry in newspaper coverage from seven UK outlets between 1985 and 2016 compatible with holding corporate power to account?

As introduced above, we decomposed accountability into problematization, causal interpretation and attribution of responsibility, which were then operationalized. We analyzed a census of articles from national circulation outlets from the UK published over 31 years (N = 766), for empirical evidence relevant to news media’s normative expectation of holding corporate power to account.

Background

Journalism and Holding Corporate Power to Account

Watchdog journalism is so fundamental to democracy that privileges and protections for the media are enshrined in laws and constitutions around the world (Felle Citation2016). If news media discharge their responsibility to serve as watchdogs, the ideas shared through their presses must create a forum adequate to support accountability.

Whether or not one endorses this normative goal – and, given the lack of consensus and the need to make ourselves accountable, it is worth noting that we do – scrutinizing business and economic elites and holding powerful private actors accountable is part of what journalists say they do and what they consider their role to be (Hanitzsch et al. Citation2019; Strauß Citation2021). It is also what functioning democracies (Ogbebor Citation2020) and corporate governance (Tambini Citation2010) require them to do. Empirical evidence tends to confirm the positive effects of news media on the quality of democratic and corporate governance, suggesting that an independent press does contribute to accountability (Norris Citation2014). It is in recognition of this role in corporate governance – by holding companies to account, investigating illegal behavior, and disseminating this information to the public – that journalistic rights and privileges have been granted (Tambini Citation2010).

The minimal conceptual consensus on accountability entails that journalists are expected to make power answerable to others with a legitimate claim to demand an account (Bovens, Schillemans, and Goodin Citation2014). For political actors, this usually means being answerable to voters, who may punish at the polls. There is less agreement on what this means for private actors. Building on the principle of affected rights and interests, third parties may demand accountability from private organizations when some agent harms their right or interest; such demands are especially relevant in the case of private bodies that receive public funding or exercise public privileges (Bovens, Schillemans, and Goodin Citation2014), as is the case of corporationsFootnote1 (Ciepley Citation2013).

The increase and concentration of corporate power and its links to numerous social, economic, and environmental harms (Clapp and Fuchs Citation2009; Hathaway Citation2018) suggest that they should indeed be held accountable. While states are often thought responsible to control corporate (mis)behavior, corporations influence governance and policy in their favor (Fuchs Citation2005). The careful embedding of discourse is a key, yet overlooked, longer-term mechanism by which corporations can realize their interests (Hathaway Citation2018). Given the heavily mediatized character of contemporary societies, this discursive or ideational power frequently operates in, with, and through media to frame issues in the public sphere. The media as a forum in which corporations shape the space of possibilities in their favor should then also be a key foci of analyses of their power (Fuchs Citation2005).

The exposure of misconduct in the media is one important tool in targeting the legitimacy of business (Fuchs Citation2005). Research suggests that attributions of responsibility exert a powerful hold on behavior (Iyengar Citation1991); in particular, attributions of responsibility in the media can play an important role in directing the public’s judgments and responses to corporations and the industry (Jeong, Yum, and Hwang Citation2018). Therefore, journalists exposé of corporate (mis)behavior justifies their special privileges and protections, which should counterbalance corporate power, and be a mechanism for corporate governance.

Case Selection: Everything Tastes Like Chicken

Agricultural food production has always attracted public scrutiny (Luhmann and Theuvsen Citation2016). With recent trends of corporate consolidation in other sectors, this industry has both consolidated and been increasingly linked to a long list of negative impacts, including social, economic, environmental and other forms of injustice and inequality, increased corporate control on policy-making and society more broadly (Clapp and Fuchs Citation2009; Howard Citation2016), and human and non-human animal health risks. The livestock sector is one of the top three most significant contributors to some of the most serious environmental problems we face today, including anthropogenic climate change, land degradation, biodiversity loss, and air and water pollution (Happer and Wellesley Citation2019).

Chicken meat production mirrors the trends and consequences of industrialization in agri-business (Jackson, Ward, and Russell Citation2010), and changes related to the intensification of animal production haven been more dramatic in the chicken meat production industry than in any other livestock sector (Bessei Citation2018). The sheer number of lives implicated in chicken meat production makes this an especially urgent case to address in light of the critiques levied against all mass animal production industries (Almiron, Cole, and Freeman Citation2018).

The similar links between chicken meat production, industrial agriculture and other industrial systems, in addition to the intrinsic relevance and visibility of the negative impacts of the industry itself, and the scale of the lives effected, all make the British chicken meat production industry a relevant, appropriate, and friendly case in which to ask if newspapers are covering the industry in ways that support accountability. The British poultry industry has also been at the heart of several food scandals over the period under study, as chicken meat consumption in the UK has been frequently linked with infections in humans related to Salmonella, Listeria, and Campylobacter, all three significant foodborne pathogens (Brizio and Prentice Citation2015) with Campylobacter being the largest cause of bacterial gastroenteritis in the developed world, and chicken being identified as the main source of human disease. The British poultry industry has specifically been pilloried on this issue: “It is time for the British poultry industry to hold up its hands and take responsibility for the lion’s share of this epidemic of human infection in the UK” (Strachan and Forbes Citation2010, 666). Another salient issue in the public debate during the period under study include the use of antibiotics in animal agriculture, which has been linked to the increase in antibiotic resistance (Finlay and Marcus Citation2016). While these, alone, would be sufficient to justify our case selection, they amount to not much more than footnotes when compared to the outbreak of the highly pathogenic H5N1 strand of avian influenza in the UK, which is one in longer list of emerging infectious diseases of zoonotic origin linked to global food production and with the worrying potential to spark another global pandemic (Canavan Citation2019; Rohr et al. Citation2019).

The ready availability of relevant scientific evidence and examples from popular media expressing concerns about chicken meat production supports our expectation that this case favors finding that that media provide a forum adequate to support accountability. One example are the “campaigning culinary documentaries” fronted by celebrity chefs (Bell, Hollows, and Jones Citation2017; Phillipov Citation2016). The media have also covered other crises related to poultry husbandry, including welfare issues related to fast-growing breeds and food safety scandals (Van Asselt et al. Citation2018). Finally, UK newspapers in particular have been shown to fulfill their role as watchdogs in their reporting on British politicians and authorities. They were found to create space for critical voices and contestations of the hegemonic industrial food discourse (Roslyng Citation2011). With regards to the avian flu outbreak, British media played an important role in amplifying the emergent rhetoric of fear, blame and uncertainty in ways that had consequences for the policy-making process and the public understanding of science (Nerlich and Halliday Citation2007). These observations suggest that, if we are to find media discharging their responsibility to serve as corporate watchdogs anywhere, we will find evidence in coverage of the chicken meat production industry in the UK in the period examined.

Running counter to the arguments we have just laid out, corporate actors and, notably, agrifood firms, use formal and informal channels to maintain favorable regulatory regimes (Clapp and Scrinis Citation2017). Hathaway (Citation2018) proposes a theoretical framework that considers decision-making, agenda-setting or bias-mobilization, and discursive or ideational elements of power, acknowledging that agency and structure can operate in each of these dimensions. The chicken meat production industry in the UK provides us with examples from across the range of mechanisms of influence that Hathaway (Citation2020) identifies and classifies according to his framework. For example, the industry boasts a strong lobby in the British Poultry Council (BPC), which serves as the voice of the industry and whose member businesses account for the vast majority of UK production, and that illustrates agential visible mechanisms of influence. The industry is also known to strive to influence both public opinion and public policy. Perhaps the most poignant and less known example of this is the use of profits from chicken meat production to finance the establishment of the Institute of Economic Affairs (Jackson, Ward, and Russell Citation2010), an influential think-tank in British politics that exemplifies both agential hidden and structural invisible mechanisms of influence: “That the intensification of chicken production was shaped by the rise of neo-liberal political ideology is relatively well-established. Less widely recognized is the role of chicken production in the development of neo-liberalism” (Jackson, Ward, and Russell Citation2010, 167).

Analytical Framework

For this study, we decomposed accountability into problematization, causal interpretation and attributions of responsibility, which were translated into concrete, operational steps through framing analysis. Problematizing, or naming something as a problem, is the first step for accountability: problematization is possible only after an issue has been defined as being inappropriate, wrong, undesirable or problematic in some way that demands for explanation, justification or resolution can arise (Maia Citation2009). At minimum, knowledge about a problem is a requirement; the public cannot be expected to take a position or action on a problem until they know about it (Neff, Chan, and Smith Citation2009). In the case of news media, they may be perceived as promoting accountability by making issues visible, directing attention to and encouraging public debate about them (Maia Citation2009).

For journalism to deliver on normative expectations and fulfil their critical-monitorial role of holding corporate power to account, problematization alone is not enough. Making actors answerable also requires exploration of the causes of the problem and attribution of responsibility for them (Maia Citation2009). An investigation of the extent to which newspapers hold corporate power to account in our case must examine whether the chicken meat production industry is constructed and recognized as a social and moral agent that can be held accountable for its actions. Following Iyengar (Citation1991), we distinguish between causal responsibility (attribution of responsibility for the creation of a problem), and treatment responsibility (attribution of responsibility for the resolution of the problem). Following Maia (Citation2009), we also distinguish between identifying something as cause of a problem (causal interpretation), and attributing causal responsibility, because it is possible to cause a problem but not be subject to be held responsible or accountable for it. For example, it is possible to identify a specific industry practice – say, overcrowding sheds – as the cause of animal welfare problems, yet not attribute causal or treatment responsibility to any actor in a manner that would allow for them to be held accountable. It is also possible to not be responsible for causing a problem, yet be called on to solve it. Using the previous example, while industry practice may have been identified as the cause of the problem, treatment responsibility in such cases is commonly attributed to governmental authorities via calls for regulation. Therefore, we used a conceptualization of accountability that incorporates cause identification, as well as attributions of causal and treatment responsibility.

Building on the clearly stated and accepted normative expectations, and given the wealth of relevant material available to journalists, it was reasonable for us to expect newspaper coverage of chicken meat production to frame the chicken meat production industry in a manner consistent with accountability. If newspapers met normative expectations, we expected to see media speakers problematizing the chicken meat production industry in a manner that suggests that the industry is the problem. We also expected to see industry presented as a cause of the problems being discussed. Finally, we expected to see the industry as a social and moral agent that is possible and proper to hold accountable for its actions.

Materials and Methods

Data Collection and Curation

To investigate if and how newspapers hold the chicken meat production industry to account, we examined newspaper coverage of chicken meat production from 1985 (when articles were more consistently digitized) to 2016 (when analysis started).

We selected seven daily newspapers from the ten highest circulation outlets in the UK with different formats, editorial perspectives and target audiences: Daily Mail, Daily Mirror, The Daily Telegraph, The Express, The Times, Financial Times, and The Guardian. We designed, piloted and refined a search string to retrieve relevant articles from LexisNexis and adapted it for outlets’ private archives for those years where data was not available on LexisNexis. The 2544 articles returned were subjected to a further relevance screening that yielded a final dataset of 766 articles. Finally, because we were interested specifically in how news media were framing the chicken meat production industry – and not how other actors are framing the industry in or through newspapers – our analyses privileged statements by media speakers: journalists, newspapers, other media outlets, and media in general, which amount to 2854 (almost 40%) of the 7227 statements (continuous topically constrained utterance by the same speaker(s)) found in the 766 relevant articles. Taken together, statements by journalists and newspapers in general (editorials or articles without an author in the byline) make up over 97% of the statements by media speakers.

Framing Analysis

As demonstrated by the work of Iyengar (Citation1991), Entman (Citation2009), and Maia (Citation2009), substantive issue framing is appropriate for studying accountability that depends on how social actors define events, assign blame, and attribute responsibilities. Substantive issue frames construct particular meanings and advance specific ways of seeing issues by their patterns of emphasis, interpretation and exclusion (Carragee and Roefs Citation2004); these selective views on issues construct reality in way that leads to different evaluations and recommendations (Matthes Citation2011). Frames are not a singular message, but rather refer to a pattern involving issue interpretation, attribution and evaluation; these frame elements are tied together in logically consistent ways (Matthes and Kohring Citation2008). In their approach to frame analysis, rather than coding the whole frame, Matthes and Kohring (Citation2008) suggest to split up the frame into the different framing elements, which can then be coded in a content analysis; this requires a frame concept that provides a clear operational definition of such framing elements. We also built on Entman’s (Citation1993) conceptualization of framing as a process of selection and salience to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for an issue. We used these four functions of a frame as the basis for a theory-informed two-stage coding strategy to identify the framing elements in the news texts: problem, cause, solution, judgment. We complemented these with framing elements that refer to the social identity of actors in relation to the issue (Hameleers et al. Citation2021), in line with Entman’s conceptualization of framing: as responsible for causing the problem (villain), as responsible for bringing about the solution to the problem (solver), and as suffering the consequences of the problem (victim). Together, these framing elements allow us to describe how a topic is problematized and constructed as an issue, and how attributions of responsibility are assigned with regards to this issue.

For our first stage, which was inductive, we worked with a randomly selected subsample of 200 articles to identify the topics that were being problematized, and used Entman’s functions to extract the specific framing elements from the news texts. The resulting values for the different framing elements were then iteratively abstracted to construct broader categories for each framing element. These categories were then used as the base for a deductive coding scheme: a set of framing element variables with their respective values and codes. This coding scheme was refined through three rounds of piloting with separate independent coders to improve internal validity, and then translated into a complete coding handbook for deductive use.

We used our inductively developed coding handbook to deductively code the full dataset, which were then systematically applied to the 766 articles, in random order. The results from the deductive content analysis were translated into frequency counts and co-occurrence frequency counts and exported to Excel for quantitative analyses. Inter-coder reliability (ICR) was calculated using Atlas.ti. To this end, two independent coders applied the coding handbook to a randomly selected subsample of 80 articles. Inter-coder reliability was calculated using Atlas.ti’s built-in Krippendorff’s c-Alpha-binary agreement coefficient. Additional details on this calculation, and our interpretation of the improbable score yielded (0.917), can be found in the supplemental material. Given the size and complexity of our coding scheme, coupled with the length and breadth of our dataset, additional measures were taken to increase internal validity of our results. The first author coded over 80% of the dataset, and reviewed the coding done by a second coder.

Operationalization

Research on accountability in contexts of agricultural production has argued that the relevant agent to recognize is an aggregate of the entire industry (Irani, Sinclair, and O'Malley Citation2002). However, there is no agreement on how to operationalize such an aggregate identity. The relevant literature makes use of diverse strategies to conceive of and operationally represent the industry. Since we did not know if or how the industry would be conceived of or problematized, we chose to cast a wide net. We structured our analysis to capture the full diversity of possibilities we had encountered so that our results would not be artifactual ().

Table 1. Summary of operationalization of analytical framework.

Building on problematization as the first step in accountability (Maia Citation2009), the first possibility for accountability is to problematize the industry. According to Entman (Citation2007), the first function of framing is defining problems worthy of public and government attention. By constructing the industry as an issue or problem that requires attention and merits debate, it becomes contestable. This is operationalized via the issue variable, which codes for what is being defined as the problem for discussion. Further context is provided via the problem definition and victim variables, which code for the terms in which the issue is being defined as problematic and the victim(s) identified as suffering the consequences of the problem, respectively.

Building on insights from substantive issue framing (Entman Citation1993, Citation2009; Matthes Citation2011), a second possibility in which the industry is constructed in a manner that speaks to holding it accountable is through causal interpretations that identify the industry as the cause of the problem. This is operationalized via the cause variable, which codes for what is being identified as the cause of the problem, as signaled by words that indicate causality (e. g. cause, have an effect, shape, influence, etc.).

These first two operationalizations speak to a broad understanding of the industry as a sector, that is, the chicken meat production sector as a whole. This includes references to the broiler, poultry or chicken meat production industry; conventional, industrial or intensive production as well as alternative production (free-range and organic); factory farming; industry practices (including husbandry, feeding, housing, and processing practices, such as use of antibiotics or fast-growth breeds, etc.); industry standards; the value chain; and chicken meat production in general, as either the problem (“in animal welfare terms, much – or even most – chicken production is a disaster”Footnote2) or the cause of the problem (“This is due to the misuse of antibiotics in the poultry industry ”).

However, neither problematization nor causal interpretation necessarily attribute causal and treatment responsibility to the industry in a manner that recognizes them as social and moral agents that can and should be held accountable for their actions. Simply put, it is possible to cause a problem but not be (held) responsible for it. Therefore, from an actor-oriented perspective, a third possibility for accountability is to construct the industry as an actor, ascribing agency in a manner that allows for the industry to be held accountable for its actions. Our analysis incorporates two possibilities in this regard, via attributions of responsibility. One possibility is for newspapers to attribute causal responsibility to the industry. This is operationalized via the villain variable, which codes for the actor(s) identified as responsible for causing the problem. The other possibility is for newspapers to attribute treatment responsibility to the industry. This is operationalized via the solver variable, which codes for the actor(s) identified as responsible for bringing about the solution. In framing the identity of the industry as an actor, whether a villain or a problem solver, there is a recognition of agency that renders the industry subject to be held accountable as social and moral agent.

Finally, it is also possible for the industry to be framed as an actor in another capacity related to the consequences of a problem (Hameleers et al. Citation2021), that of victim. In contrast to framing an actor as a villain or solver, and thus attributing responsibility, framing as a victim highlights an actor as suffering the consequences of the problem, in a manner that might inhibit processes of accountability. In our study, this is operationalized via the victim variable, which codes for the actor suffering the consequences of the problem. ()

Since we did not know beforehand how newspapers would define the industry as an actor and, in the case of a collective actor, who would be included in such an understanding, we divided the actors in the chicken meat production chain and coded at a lower level (actor, subgroup, group), while maintaining the possibility of aggregation. This allowed us to conduct the analyses at different levels for those categories of actors that would reasonably be included for an understanding of corporate power, and collapse categories where there were no analytically relevant differences. For the purpose and scope of this study, we focused on a narrow understanding of the industry as an actor, including only explicit mentions of the industry and industry bodies. [See supplemental material]

Research Questions

This study focuses on three specific research questions, each addressed in a subsection of the results. The first two specific research questions build on problematization as the first step in accountability, and refer to the construction of the industry as either the problem or the cause of the problem.

RQ1. Did media speakers construct the industry as a problem and if so, how?

RQ2. Did media speakers make causal interpretations that construct the industry and industry practices as cause of the problem and if so, how?

The third research question builds on attributions of responsibility as central to accountability by examining the extent to which media speakers’ attributions of responsibility construct the industry as a social and moral agent subject to be held accountable for its actions. Construction of the industry solely as a victim paints the industry as suffering consequences in a manner that is not compatible with holding industry to account.

RQ3. Did media speakers explicitly attribute causal or treatment responsibility to the industry, thus constructing it as a social and moral agent subject to accountability and if so, how?

While the literature clearly expects the behaviors our method is designed to detect, there are no clear justified expectations with respect to either the frequency or the conditions that are relevant in predicting the frequency of such behavior. Therefore, frequency is operationalized as raw and relative occurrence and co-occurrence.

Results

Problematization of the Industry

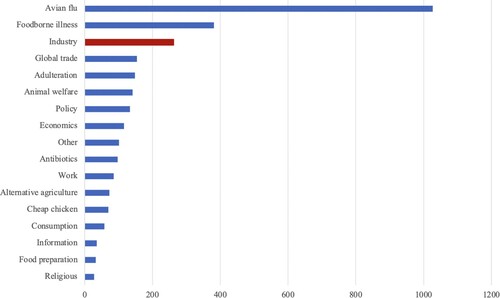

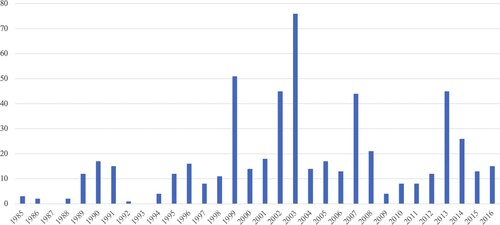

Out of 2854 statements by media speakers, 547 explicitly problematize the chicken meat production industry. Roughly one in five statements () discussed the industry in a way that suggested that this is the problem, in a manner that can lead to demands of explanation or justification and, eventually, attributions of responsibility, as part of processes of accountability (Maia Citation2009). This figure was higher for investigative reports (n = 29), with just over one in three constructing the industry as a problem. This shows that the industry itself was problematized in newspaper coverage to varying degrees over time (). However, the industry was not the issue that received most coverage. The issue most often problematized throughout our dataset was avian influenza, with 1027 mentions (35%). Looking at the period during which avian influenza was relevant (the H5N1 outbreak between 2003-2008) on average, we found 31 media speaker statements that problematized the industry per year (18 for the entire period of study), while there were an average of 159 mentions of avian influenza.

Figure 2. Frequency distribution of statements by media speakers that problematize the industry per year.

Other problems mentioned in our dataset include global trade, animal welfare, policy, economics, etc. [see supplemental material]. Over 93% of media speaker statements that discuss other issues related to chicken meat production do so in a way that does not suggest that the industry is a problem [see supplemental material]. For foodborne illness, the second most frequently mentioned issue at 13% of statements (and the most frequently mentioned issue in investigative reports), some statements problematize chicken meat production: “A bacteria called campylobacter, found in almost three-quarters of chicken sold in the UK, is the biggest cause of food poisoning in the UK”; but statements, as indicated in the following quotation, typically made no such connection: “Salmonella is still quite likely to be an uninvited guest at some wedding feasts. Last year, salmonella poisoned more than 600 guests at 10 wedding receptions”. Here, foodborne illness arises from naturally occurring bacteria so is not framed in a manner that suggested that the chicken meat production industry is the problem.

Causal Interpretation

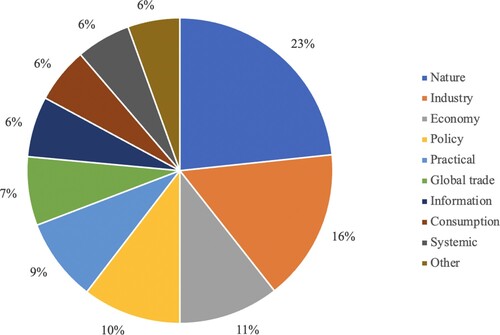

Industry was identified as a cause in 16% of the cases where causes were identified (). Coverage that does not place industry as the primary cause and relatively evenly distributes attribution between eight other options, particularly in light of the rich scientific evidence available at the time pointing to industry, is not consistent with the expectation that newspaper coverage supports corporate accountability.

We identified thirteen categories of causal interpretations and coded 1980 statements by media speakers that indicate causation. From those, 318 identified the industry and its practices as a cause (59 of these occurred in investigative reports). Some of these explicitly framed the poultry industry’s growth as a cause: “The huge growth in this country's poultry industry over the last 30 years (…) has triggered a massive increase in food poisoning”. The methods and practices of industrial chicken meat production were also identified (“The idleness imposed by factory farming methods is being blamed for soaring obesity levels among chickens, a problem that affects conventionally and organically produced meat”; “There is increasing concern that growth-promoting antibiotics encourage farm bugs to mutate, causing food poisoning in humans that becomes ever harder to treat”). This last example illustrates the difference between constructing something as the problem or as the cause of the problem: the journalist identified a human health problem, namely foodborne illness, and identified the growth-promoting antibiotics as the cause of that problem without links to the industry.

Nature, at 23% of mentions, was the most frequently mentioned cause. These statements, for example, nominate wild bird migration, “it is likely the virus was brought into the country by migratory birds”, and pathogens, “The bacterium causes vomiting and diarrhea in around 280,000 healthy people every year and can kill those with vulnerable immune systems”. Other attributions nominated the economy “Heavy oversupply followed by a fall in demand will push some producers out of business” and policies “Under European Union rules, poultry labeled organic cannot be reared indoors. This could cause problems for producers of organic poultry”.

Other causes mentioned in our dataset related to the economy, policy and regulation, practical failures (including punctual food safety, biosecurity, traceability, or inspection and control failures), global trade, problematic or absent information, consumption and consumer behaviors, and systemic causes (e.g., commodification, globalization, industrialization, intensification, etc.). Other less frequently mentioned causes that have been grouped together include accidents, acts of deviance, activism, or other causes not included in the previous categories.

Investigative reports, which constitute 29 of the 766 articles reviewed, presented a different percentage distribution of causal interpretations. In these reports, the chicken meat production industry was the most frequently mentioned cause; just over a quarter of all the statements by media speakers that identified any cause for problems related to chicken meat production pointed the finger explicitly at the industry.

Attributions of Responsibility

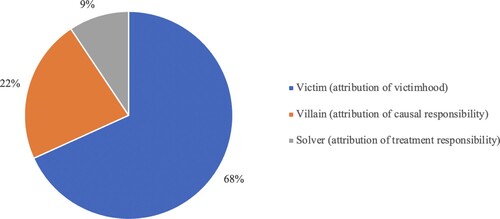

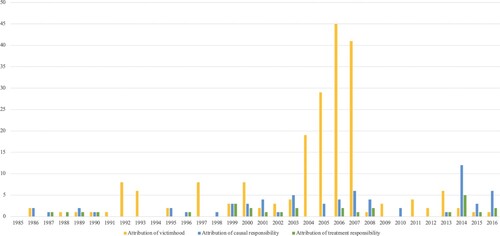

Media speakers seldom attributed causal or treatment responsibility to the chicken meat production industry in a manner consistent with their accountability. Media statements identifying the industry as the actor responsible for causing or bringing about the solution to the problem were rare, even when limiting analysis to those statements that also problematize or identify the industry as cause or villain, and particularly when compared to the more frequent framing of the industry as a victim (). Media speakers most often failed to construct the industry as a social and moral agent in a manner compatible with the expectation that news media hold corporate power to account.

We found 67 statements by media speakers that framed the industry as responsible for causing the problem which is 8% of the total attributive statements. Further, 13% of the statements identifying industry as cause and just under 8% of those that problematized the industry also attributed causal responsibility to the industry. This means that the vast majority of media speaker statements that identified the industry as a cause of the problem did not present industry as accountable. Failure to construct industry as a social and moral agent is not compatible with the expectation of newspaper coverage that presents industry as subject to being held accountable for its actions. For example, while in this quote industry is presented as accountable, “the environmental damage caused by industrial poultry production. Each year the industry in Britain produces 130,000 tonnes of nitrogen from chicken droppings, as well as phosphorus, both of which damage the environment”, in the following quote a practice is the cause for neither the industry nor any other actor is accountable, “A major cause of antibiotic resistance is the careless use of these drugs in treating non-bacterial infections in humans and in preventing diseases and promoting growth in animals”.

In a more poignant example, this extract hides those accountable by use of the passive voice “These chickens are reared for meat. Between March 2000 and March 2001 817 m chickens were reared for slaughter. Most are kept in dimly lit, crowded, windowless sheds, and have been selectively bred to reach their slaughter weight in 40–42 days (…) Roughly 2% of birds die from heart failure”.

We coded 28 news media statements that identified the industry as responsible for bringing about the solution to the problem, as in this example: “The policy of naming and shaming the dirtiest companies for their campylobacter rates has been a key part of the FSA's strategy to deal with industry's failure to tackle what is the commonest form of food poisoning in the UK”. Such statements made up roughly 3% of media speaker statements that attribute treatment responsibility. Government was more frequently framed as responsible for solving a problem even when the industry had been problematized or attributed causal responsibility. Media speakers’ coverage of chicken meat production did not highlight the industry as an actor responsible for solving the problem, even in those cases in which it was constructed as the problem or its cause.

While we found 28 statements that framed industry as a problem solver, we also found 204 statements that framed the industry as a victim () … a figure that nearly matches the frequency with which non-human animals are mentioned as victims. Most instances of the industry being framed as the victim relate to avian influenza, as illustrated here: “The warning is bound to add to fears that bird flu will devastate Britain's £3billion poultry industry”. We also found that the industry was framed as a victim of cheap imports and global trade, public policies, and even in an article discussing animal welfare problems in the industry. Even when we exclude articles covering the outbreak of avian influenza – in which 94% of media statements frame the industry as a victim –, almost half of all media speaker statements framed the industry as victim.

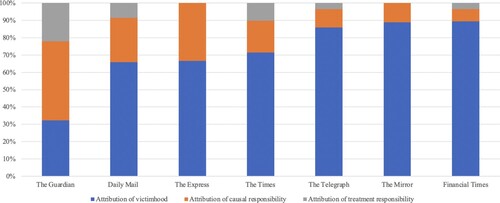

Though overall, media speakers most frequently framed the chicken meat production industry as a victim, the framing of the industry changed both over time and across outlets. shows that attribution of victimhood to the industry were very frequent between 2003 and 2008, illustrating how the industry was mostly framed as a victim of the avian influenza outbreak that occurred between those years. By contrast, the highest frequency of attributions of both causal and treatment responsibility occurred in 2014, during which coverage of foodborne illness – mostly due to campylobacter – was the most frequently covered issue in our dataset (and consistent with research suggesting poultry is the most likely cause of most human cases of campylobacteriosis (Royden et al. Citation2021)).

Figure 5. Frequency distribution of media speakers’ attributions of causal responsibility, treatment responsibility and victimhood to the industry per year.

Disaggregating the data by outlet also showed differences (). The Guardian was the only outlet that attributed responsibility to the industry more frequently than it framed it as a victim. By contrast, The Telegraph, The Mirror and the Financial Times almost exclusively framed the industry as a victim. What is more, The Guardian alone accounts for roughly half of all attributions of both causal and treatment responsibility attributions to the chicken meat production industry in our dataset.

Discussion

We examined a census of relevant articles for evidence that spoke to whether and how newspapers hold corporate power to account. We found that media speakers did problematize the industry, that they rarely constructed it as cause or attributed responsibility to it, and that they more frequently presented industry as a victim. While we found instances of problematization and attribution of responsibility towards the chicken meat production industry that are compatible with a broader approach to accountability, particularly in investigative reports, these instances represented less than 4% of our dataset, suggesting that media speakers’ contribution to the overall shape of that forum is not compatible with holding corporate power to account. Our findings raise serious concerns for this case, for media practice, and for media scholarship.

The infrequency with which the behavior expected by critical media scholars was encountered and the dilution of these instances with presentations of industry as victim do not encourage broad public acceptance of scientific understanding nor did they convey the urgency (Entman Citation2010) required for the launch of accountability processes. These findings echo research suggesting that the framing of chicken meat production in newspaper coverage effectively supports a form of hiding in plain sight that may protect industry more effectively than coerced silence (Garnier et al. Citation2020).

Our findings were particularly troubling given the availability of relevant scientific knowledge (e.g., Canavan (Citation2019), Strachan and Forbes (Citation2010), and Waltner-Toews (Citation2017)), and the presence of this knowledge in popular media (Bell, Hollows, and Jones Citation2017; Phillipov Citation2016). Our findings are consistent with those of Kristiansen, Painter, and Shea (Citation2021) who observed that responsibility for treatment is more frequently assigned to individual consumption rather than agricultural production methods or regulations.

Media speakers did not generally frame the chicken meat production industry in a manner compatible with recognizing it as social and moral agent that is subject to be held accountable for the problems they are presented as creating (with The Guardian being a notable exception). Moreover, if we accept attributions of treatment responsibility as an important part of accountability (Maia Citation2009) – the “you break it, you fix it” principle – then the infrequency of this argument in media speakers’ coverage is not compatible with the expectation that news media hold industry to account.

In our study, industry was frequently presented as a victim. If the prominence and repetition of framing elements improve their potential for influence (Entman Citation2009), and if the inclusion of diverse yet clearly minority perspectives is indicative of fairness, then readers would reasonably conclude that a fair examination of the chicken meat production finds industry to be the victim. This is not consistent with the expectation that news media hold corporate power to account.

Our findings have troubling implications for our collective ability to hold corporate power to account. Studies have shown that attributions of responsibility in the media influence the public’s attributions of responsibility for political issues, the likelihood of their holding political actors accountable (Iyengar Citation1991), as well as their judgment and responses to corporations and the industry (Jeong, Yum, and Hwang Citation2018). Our findings lend empirical weight to the findings of Iyengar (Citation1991) and Maia (Citation2009) who suggest that news media coverage effectively, though not necessarily intentionally, protects those they are to expose.

Our findings underscore the relevance of further research on the norms, practices, routines, and material environment of news production that yield the patters we describe. One of the limitations of the present study is that the data and research design do not support claims as to the reasons behind journalistic choices that result in the patterns described. However, the practical and theoretical implications of these patterns reinforces the need to better understand the conditions required for news media to deliver on the normative expectations that justify journalists’ own discursive construction of their profession’s centrality in democratic societies (Hanitzsch and Vos Citation2018; Hanitzsch et al. Citation2019).

Our findings do not support the argument that news media slavishly support corporate interests (Curran Citation2005). The examples we found where media speakers frame the industry in ways that fully meet these expectations – most notably, The Guardian – demonstrate that there are conditions under which media speakers can and do hold corporate power accountable, thus challenging and potentially transforming power relations (Fenton Citation2010). Investigative journalists problematized the industry more frequently; however, the rarity of their contributions renders their status more the exception that makes the rule than evidence that the forum for public debate created within the media is adequate to hold power to account.

The framework and methodology used in our study found contradictions in the practice of media speakers that are incompatible with rhetorically convenient but empirically naïve essentializations. Rather, we find empirical support for the recognition of journalism as fragmented, complex, and open-ended (Waisbord Citation2018) in ways that appear to be functional to short-term industry interests.

Despite the centrality of normative expectations to our understanding of journalism’s place in democracy and society, our findings echo concerns about their increasing disconnect with journalism’s realities (Hanitzsch and Vos Citation2018), pointing instead to a gap between a relatively broadly accepted, if naively conceived, normative expectations and the actual conditions of news media practice (Phillips, Couldry, and Freedman Citation2010). In this sense, our findings lend unexpected credibility to our deliberate choice not to focus our study on investigative reporting. Our study placed those reports in context in a manner that permitted us both to recognize their merits and their limited relevance for shaping a forum for accountability. Our findings echo calls for a revision of journalism scholarship. Instead of reifying and discursively reproducing normative patterns (Parks Citation2020) grounded on problematic assumptions (Bennett and Pfetsch Citation2018) and Western biases (Stetka and Örnebring Citation2013), we should develop analytic frameworks and methodologies fit to describe media practice, and elucidate the conditions under which media practice is able to interpret normative expectations born of perhaps a simpler understanding for current disrupted public spheres (Bennett and Pfetsch Citation2018) and high choice media environments (Van Aelst et al. Citation2017).

Taking into account the conceptual problems that restrict empirical investigations of corporate power (Hathaway Citation2018) and the obstacles for systematic empirical assessment of the performance of news media (Callaghan and Schnell Citation2001; Mellado and Van Dalen Citation2017), we have developed and operationalized an analytical framework that allows for a systematic and replicable examination of whether and how news media holds corporate power accountable.

The dimensions of accountability that our research has operationalized are not the only ones at play. Future research should find ways of making these other dimensions visible in ways that support systematic empirical analysis. Hathaway (Citation2018), for example, argues that scholarly focus on decision-making within the political arena could effectively hamper empirical research, as failure to recognize corporate power as part of capitalist democracy can mean that decisions that are taken off the governmental agenda are also taken off the research agenda. We hope that the model provided by the methodology we have developed and successfully applied will contribute to the struggle to understand and to support media that meet the expectations that justify their privileges.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (169.9 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive criticism.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data underlying this publication are available at https://doi.org/10.17026/dans-xuq-ve6a.

Notes

1 For a discussion of how the corporation came to be viewed as nothing more than a nexus of contracts among private individuals in a manner which exempted it from accountability, and how reducing corporations to private contract is problematic in numerous ways, see Ciepley (Citation2013).

2 Unless otherwise stated, emphasis in citations has been added by the authors of this publication. A list of the articles from which each example is extracted can be found in the supplemental material.

References

- Almiron, N., M. Cole, and C. P. Freeman. 2018. “Critical Animal and Media Studies: Expanding the Understanding of Oppression in Communication Research.” European Journal of Communication 33 (4): 367–380. doi:10.1177/0267323118763937.

- Bell, D., J. Hollows, and S. Jones. 2017. “Campaigning Culinary Documentaries and the Responsibilization of Food Crises.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 84: 179–187. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.03.014.

- Bennett, W. L., and B. Pfetsch. 2018. “Rethinking Political Communication in a Time of Disrupted Public Spheres.” Journal of Communication 68 (2): 243–253. doi:10.1093/joc/jqx017

- Bessei, W. 2018. “Impact of Animal Welfare on Worldwide Poultry Production.” World's Poultry Science Journal 74 (2): 211–224. doi:10.1017/S0043933918000028.

- Blumler, J. G., and F. Esser. 2019. “Mediatization as a Combination of Push and Pull Forces: Examples During the 2015 UK General Election Campaign.” Journalism 20 (7): 855–872. doi:10.1177/1464884918754850

- Bovens, M., Schillemans, T., & Goodin, R. E. (2014). Public Accountability. In M. Bovens, R. E. Goodin, & T. Schillemans (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Public Accountability (pp. 1-22). Oxford University Press.

- Boyd, W. 2001. “Making Meat: Science, Technology, and American Poultry Production.” Technology and Culture 42 (4): 631–664. doi:10.1353/tech.2001.0150.

- Brizio, A., & Prentice, C. (2015). Chilled Broiler Carcasses: A Study on the Prevalence of Salmonella, Listeria and Campylobacter [Article]. International Food Research Journal, 22(1), 55-58. <Go to ISI>://WOS:000422937100008.

- Callaghan, K., & Schnell, F. (2001). Assessing the Democratic Debate: How the News Media Frame Elite Policy Discourse. Political Communication, 18(2), 183-213. doi:10.1080/105846001750322970

- Canavan, B. C. 2019. “Opening Pandora's Box at the Roof of the World: Landscape, Climate and Avian Influenza (H5N1).” Acta Tropica 196: 93–101. doi:10.1016/j.actatropica.2019.04.021.

- Carragee, K. M., and W. Roefs. 2004. “The Neglect of Power in Recent Framing Research.” Journal of Communication 54 (2): 214–233. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2004.tb02625.x

- Carson, A. 2014. “The Political Economy of the Print Media and the Decline of Corporate Investigative Journalism in Australia.” Australian Journal of Political Science 49 (4): 726–742. doi:10.1080/10361146.2014.963025

- Christians, C. G., T. Glasser, D. McQuail, K. Nordenstreng, and R. A. White. 2010. Normative Theories of the Media: Journalism in Democratic Societies. University of Illinois Press.

- Ciepley, D. 2013. “Beyond Public and Private: Toward a Political Theory of the Corporation.” American Political Science Review 107 (1): 139–158. doi:10.1017/S0003055412000536.

- Clapp, J., and D. Fuchs. 2009. Corporate Power in Global Agrifood Governance. MIT Press.

- Clapp, J., and G. Scrinis. 2017. “Big Food, Nutritionism, and Corporate Power.” Globalizations 14 (4): 578–595. doi:10.1080/14747731.2016.1239806.

- Curran, J. (2005). Mediations of Democracy. In J. Curran & M. Gurevitch (Eds.), Mass Media and Society (4th ed.). Hodder Education.

- Curran, J., and J. Seaton. 2002. Power Without Responsibility: Press, Broadcasting and the Internet in Britain. Routledge.

- Cushion, S., A. Kilby, R. Thomas, M. Morani, and R. Sambrook. 2018. “Newspapers, Impartiality and Television News: Intermedia Agenda-Setting During the 2015 UK General Election Campaign.” Journalism Studies 19 (2): 162–181. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2016.1171163

- D'angelo, P. 2002. “News Framing as a Multiparadigmatic Research Program: A Response to Entman.” Journal of Communication 52 (4): 870–888. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2002.tb02578.x

- Entman, R. M. 1993. “Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm.” Journal of Communication 43 (4): 51–58. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

- Entman, R. M. 2007. “Framing Bias: Media in the Distribution of Power.” Journal of Communication 57 (1): 163–173. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00336.x.

- Entman, R. M. 2009. Projections of Power: Framing News, Public Opinion, and US Foreign Policy. University of Chicago Press.

- Entman, R. M. 2010. “Improving Newspapers’ Economic Prospects by Augmenting Their Contributions to Democracy.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 15 (1): 104–125. doi:10.1177/1940161209352371.

- Felle, T. 2016. “Digital Watchdogs? Data Reporting and the News Media’s Traditional ‘Fourth Estate’ Function.” Journalism 17 (1): 85–96. doi:10.1177/1464884915593246.

- Fenton, N. (2010). Drowning or Waving? New Media, Journalism and Democracy. In N. Fenton (Ed.), New Media, Old News: Journalism and Democracy in the Digital Age (pp. 3-16). SAGE Publications. doi:10.4135/9781446280010.n1

- Fenton, N. 2019. (Dis)Trust. Journalism 20 (1): 36–39. doi:10.1177/1464884918807068.

- Finlay, M. R., & Marcus, A. I. (2016). “Consumerist Terrorists”: Battles over Agricultural Antibiotics in the United States and Western Europe. Agricultural History, 90(2), 146-172. doi:10.3098/ah.2016.090.2.146

- Freedman, D. 2014. The Contradictions of Media Power. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Fuchs, D. (2005). Commanding Heights? The Strength and Fragility of Business Power in Global Politics. Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 33(3), 771-801. doi:10.1177/03058298050330030501

- Garnier, M., M. van Wessel, P. A. Tamás, and S. van Bommel. 2020. “The Chick Diffusion: How Newspapers Fail to Meet Normative Expectations Regarding Their Democratic Role in Public Debate.” Journalism Studies 21 (5): 636–658. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2019.1707705.

- Hallin, D. C., and C. Mellado. 2018. “Serving Consumers, Citizens, or Elites: Democratic Roles of Journalism in Chilean Newspapers and Television News.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 23 (1): 24–43. doi:10.1177/1940161217736888.

- Hameleers, M., D. Schmuck, A. Schulz, D. S. Wirz, J. Matthes, L. Bos, N. Corbu, and I. Andreadis. 2021. “The Effects of Populist Identity Framing on Populist Attitudes Across Europe: Evidence from a 15-Country Comparative Experiment.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research, doi:10.1093/ijpor/edaa018.

- Hanitzsch, T., and T. P. Vos. 2018. “Journalism Beyond Democracy: A new Look Into Journalistic Roles in Political and Everyday Life.” Journalism 19 (2): 146–164. doi:10.1177/1464884916673386.

- Hanitzsch, T., Vos, T. P., Standaert, O., Hanusch, F., Hovden, J. F., Hermans, E., Ramaprasad, J., & Oller Alonso, M. (2019). Role orientations: Journalists’ views on their place in society. Hanitzsch, T.; Hanusch, F.; Ramaprasad, J. (ed.), Worlds of Journalism: Journalistic Cultures Around the World, 161-198.

- Hanusch, F. 2019. “Journalistic Roles and Everyday Life.” Journalism Studies 20 (2): 193–211. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2017.1370977

- Happer, C., and L. Wellesley. 2019. “Meat Consumption, Behaviour and the Media Environment: A Focus Group Analysis Across Four Countries.” Food Security 11 (1): 123–139. doi:10.1007/s12571-018-0877-1.

- Hathaway, T. 2018. “Corporate Power Beyond the Political Arena: The Case of the ‘Big Three’ and CAFE Standards.” Business and Politics 20 (1): 1–37. doi:10.1017/bap.2016.12

- Hathaway, T. (2020). Neoliberalism as Corporate Power. Competition & Change, 24(3-4), 315-337, doi:10.1177/1024529420910382

- Hay, C. 1997. “Divided by a Common Language: Political Theory and the Concept of Power.” Politics 17 (1): 45–52. doi:10.1111/1467-9256.00033

- Howard, P. H. (2016). Concentration and Power in the Food System: Who Controls What we eat? (Vol. 3). Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Irani, T., Sinclair, J., & O'Malley, M. (2002). The Importance of Being Accountable - The Relationship Between Perceptions of Accountability Knowledge, and Attitude Toward Plant Genetic Engineering. Science Communication, 23(3), 225-242. doi:10.1177/107554700202300302

- Iyengar, S. 1991. Is Anyone Responsible?: How Television Frames Political Issues. University of Chicago Press.

- Jackson, P., Ward, N., & Russell, P. (2010). Manufacturing Meaning Along the Chicken Supply Chain: Consumer Anxiety and the Spaces of Production. Consuming Space: Placing Consumption in Perspective Eds MK Goodman, D Goodman, M Redclift (Ashgate, Aldershot, Hants) pp, 163-187.

- Jeong, S. H., Yum, J., & Hwang, Y. (2018). Effects of Media Attributions on Responsibility Judgments and Policy Opinions. Mass Communication and Society, 21(1), 24-49. doi:10.1080/15205436.2017.1362002

- Kristiansen, S., Painter, J., & Shea, M. (2021). Animal Agriculture and Climate Change in the US and UK Elite Media: Volume, Responsibilities, Causes and Solutions. Environmental Communication, 15(2), 153-172. doi:10.1080/17524032.2020.1805344

- Langer, A. I., and J. B. Gruber. 2020. “Political Agenda Setting in the Hybrid Media System: Why Legacy Media Still Matter a Great Deal.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 0 (0): 19s40161220925023. doi:10.1177/1940161220925023

- Luhmann, H., and L. Theuvsen. 2016. “Corporate Social Responsibility in Agribusiness: Literature Review and Future Research Directions.” Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 29 (4): 673–696. doi:10.1007/s10806-016-9620-0

- Maia, R. C. M. (2009). Media Visibility and the Scope of Accountability. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 26(4), 372-392. doi:10.1080/15295030903176666

- Matthes, J. (2011). “Framing Politics: An Integrative Approach.” American Behavioral Scientist, 0002764211426324.

- Matthes, J., and M. Kohring. 2008. “The Content Analysis of Media Frames: Toward Improving Reliability and Validity.” Journal of Communication 58 (2): 258–279. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.00384.x

- Mellado, C., and A. Van Dalen. 2017. “Changing Times, Changing Journalism: A Content Analysis of Journalistic Role Performances in a Transitional Democracy.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 22 (2): 244–263. doi:10.1177/1940161217693395

- Neff, R. A., I. L. Chan, and K. C. Smith. 2009. “Yesterday's Dinner, Tomorrow's Weather, Today's News? US Newspaper Coverage of Food System Contributions to Climate Change.” Public Health Nutrition 12 (7): 1006–1014. doi:10.1017/S1368980008003480

- Nerlich, B., and C. Halliday. 2007. “Avian flu: The Creation of Expectations in the Interplay Between Science and the Media.” Sociology of Health & Illness 29 (1): 46–65. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.00517.x

- Norris, P. (2014). Watchdog Journalism. In M. Bovens, R. E. Goodin, & T. Schillemans (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Public Accountability (pp. 525-541). Oxford University Press.

- Ogbebor, B. (2020). British Media Coverage of the Press Reform Debate: Journalists Reporting Journalism. Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-37265-1.

- Opel, A., Johnston, J., & Wilk, R. (2010). Food, Culture and the Environment: Communicating About What We Eat. Environmental Communication, 4(3), 251-254. doi:10.1080/17524032.2010.500448

- Parks, P. 2020. “Researching With Our Hair on Fire: Three Frameworks for Rethinking News in a Postnormative World.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 97 (2): 393–415. doi:10.1177/1077699020916425

- Phillipov, M. (2016). The new Politics of Food: Television and the Media/Food Industries. Media International Australia, 158(1), 90-98. doi:10.1177/1329878×15627339

- Phillips, A., N. Couldry, and D. Freedman. 2010. “An Ethical Deficit? Accountability, Norms, and the Material Conditions of Contemporary Journalism.” New Media, old News: Journalism & Democracy in the Digital Age, 51–68. doi:10.4135/9781446280010.n4

- Porenta, F. 2019. “Was Piketty Right? Empirics of CCC Model: Corporate Power, Consumption, Debt and Inequality.” Panoeconomicus 66 (4): 439–464. doi:10.2298/PAN160920019P

- Rao, S. 2008. “Accountability, Democracy, and Globalization: A Study of Broadcast Journalism in India.” Asian Journal of Communication 18 (3): 193–206. doi:10.1080/01292980802207041

- Rohr, J. R., Barrett, C. B., Civitello, D. J., Craft, M. E., Delius, B., DeLeo, G. A., Hudson, P. J., Jouanard, N., Nguyen, K. H., Ostfeld, R. S., Remais, J. V., Riveau, G., Sokolow, S. H., & Tilman, D. (2019). Emerging Human Infectious Diseases and the Links to Global Food Production. Nature Sustainability, 2(6), 445-456. doi:10.1038/s41893-019-0293-3

- Roslyng, M. M. 2011. “Challenging the Hegemonic Food Discourse: The British Media Debate on Risk and Salmonella in Eggs.” Science as Culture 20 (2): 157–182. doi:10.1080/09505431.2011.563574

- Royden, A., R. Christley, T. Jones, A. Williams, F. Awad, S. Haldenby, P. Wigley, S. P. Rushton, and N. J. Williams. 2021. “Campylobacter Contamination at Retail of Halal Chicken Produced in the United Kingdom.” Journal of Food Protection 84 (8): 1433–1445.. doi:10.4315/JFP-20-428

- Scheufele, D. A., and D. Tewksbury. 2007. “Framing, Agenda Setting, and Priming: The Evolution of Three Media Effects Models.” Journal of Communication 57 (1): 9–20. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00326.x.

- Stetka, V., and H. Örnebring. 2013. “Investigative Journalism in Central and Eastern Europe.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 18 (4): 413–435. doi:10.1177/1940161213495921

- Strachan, N. J. C., & Forbes, K. J. (2010). The Growing UK Epidemic of Human Campylobacteriosis. The Lancet, 376(9742), 665-667. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60708-8

- Strauß, N. 2021. “Covering Sustainable Finance: Role Perceptions, Journalistic Practices and Moral Dilemmas.” Journalism 0(0): 14648849211001784. doi:10.1177/14648849211001784

- Tambini, D. 2010. “What are Financial Journalists for?” Journalism Studies 11 (2): 158–174. doi:10.1080/14616700903378661

- Van Aelst, P., Strömbäck, J., Aalberg, T., Esser, F., De Vreese, C., Matthes, J., Hopmann, D., Salgado, S., Hubé, N., & Stępińska, A. (2017). Political Communication in a High-Choice Media Environment: A Challenge for Democracy? Annals of the International Communication Association, 41(1), 3-27. doi:10.1080/23808985.2017.1288551

- Van Asselt, M., Poortvliet, P. M., Ekkel, E. D., Kemp, B., & Stassen, E. N. (2018). Risk Perceptions of Public Health and Food Safety Hazards in Poultry Husbandry by Citizens, Poultry Farmers and Poultry Veterinarians. Poultry Science, 97(2), 607-619. doi:10.3382/ps/pex325

- Wahl-Jorgensen, K., and J. Hunt. 2012. “Journalism, Accountability and the Possibilities for Structural Critique: A Case Study of Coverage of Whistleblowing.” Journalism 13 (4): 399–416. doi:10.1177/1464884912439135

- Waisbord, S. R. 2000. Watchdog Journalism in South America: News, Accountability, and Democracy. Columbia University Press.

- Waisbord, S. R. 2018. “Truth is What Happens to News: On Journalism, Fake News, and Post-Truth.” Journalism Studies 19 (13): 1866–1878. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2018.1492881

- Waltner-Toews, D. (2017). Zoonoses, One Health and Complexity: Wicked Problems and Constructive Conflict. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 372(1725), 1-9. doi:10.1098/rstb.2016.0171