ABSTRACT

As digital technologies have made their way into news production, allowing news organizations to measure audience behaviors and engagement in real-time, click-based and editorial goals have become increasingly intertwined. Ongoing developments in algorithmic technologies allow editors to bring their audience into the newsroom using specialized tools such as Chartbeat or Google Analytics. This article examines how these technologies have affected the composition of the audience and their power to influence news-making processes inside two Chilean newsrooms. Drawing on several months of newsroom ethnography, we identify how the pursuit of “clickable news” impacts editorial processes and journalistic priorities by changing the datafied audience opinion power behind news production. Shifts in opinion power, loss of control, and increased platform dependency may contribute to a concentrated media landscape. Our findings show that opinion power has shifted to a datafied version of the audience, raising new questions about platform dependency and editorial autonomy in media organizations. These results carry significant implications for understanding the chase for traffic in current multiplatform newsrooms and how this phenomenon impacts news production.

Vignette

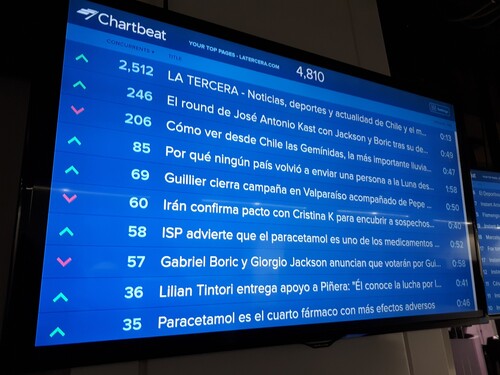

Two large blue screens hang from the wall in the middle of the newsroom of the Chilean daily newspaper La Tercera. The displays show data supplied by Chartbeat (see ), a technology company that provides analytics about the behavior of online audiences to publishers and media organizations around the world (Lamot and Van Aelst Citation2020; Petre Citation2015; Usher Citation2013). Hovering over the newsroom, the screens show the number of concurrent readersFootnote1 presently visiting any site page. Immediately after publishing an article on the web, any digital journalists in the room can spin their chairs around and look at the screens to see how many people, if any at all, are reading their pieces at this very moment in real-time.

Image 1. Screens showing Chartbeat data for La Tercera's website (Photo: Lead author during fieldwork. December 2017).

Much like a group of friends watching a race on television, digital journalists at La Tercera joke about their own articles moving up or down in the concurrent list and gloat unapologetically if their articles remain in the top three for an extended period. Unlike linear television ratings and viewership numbers, which measure only the current content on screen, Chartbeat creates a strange sense of competition among journalists, for it informs reporters about people’s preferences between all the content available on the website. It is a direct message about how the audience values and rewards the topics journalists have been working on and bestows upon the winner a feeling of success over their co-workers based solely on the number of times someone has clicked on their story.

Like many other communication-related industries, news media companies are facing a growing global financial crisis, moving inexorably towards a scenario of hyper-competition ruled by a new attention economy (Myllylahti Citation2020; Nixon, Citation2020; Thurman and Myllylahti Citation2009). The race to capture an ever more connected and yet ever more fragmented audience has encouraged media organizations to seek strategies to report the news that better align with this new need for attention-grabbing journalism (Carlson Citation2018; Ferrer-Conill and Tandoc Citation2018; Fletcher and Nielsen Citation2017). It is in this context that the rapid datafication of the audience, thanks to new algorithms and analytics tools, has become key to estimating the popularity of news production (Christin Citation2018; Zamith Citation2018), as well as to quantifying individual journalists’ production rates (Christin Citation2020; Powers Citation2018). Indeed, rather than working as a tool to promote inclusion or foster a more diverse exposure for the audience, popularity-driven metrics have arguably become a strongly detailed, low-cost click-counter for the performance of individual news items online (Welbers et al. Citation2016).

As technologies that help media organizations measure audience behavior have become ubiquitous in newsrooms across the globe during the last decade (Petre Citation2015), the benefits of software like Chartbeat have become more evident among newsmakers looking to maximize materialistic and non-materialistic rewards (Fengler and Ruß-Mohl Citation2008). According to Moyo, Mare, and Matsilele (Citation2019), measuring the performance of news stories could allow editors to effectively compare themselves with a rival news organization, identify areas of the newsroom that could be underperforming, and perhaps most importantly, increase their advertising revenues. Blanchett Neheli (Citation2018) further argues that by employing analytics to understand the audience’s likes and dislikes, newsrooms can further boost their readers’ engagement with news articles.

Nevertheless, along with these benefits, audience metrics are also transforming routines, practices, and even professional codes within newsrooms (Anderson Citation2011; Fürst Citation2020). The creation of a “culture of data” (Lamot and Paulussen Citation2020) in news organizations is changing the way reporters approach their work, generating the need for new routines while at the same time transforming old, already established practices (Hanusch Citation2017). Although some recent literature has examined audience metrics in journalism and their effect on reporters’ practices (Christin Citation2020; Coddington, Lewis, and Belair-Gagnon Citation2021; Petre Citation2021; Walters Citation2022), no prior research has explored the way popularity driven-metrics constitute a new form of opinion power. In this article, we explore how popularity-driven metrics transform editorial processes and journalistic practices by changing the opinion-sharing power behind news production and how popularity-driven metrics constitute a new form of opinion power. Drawing on extensive ethnographic work, this article aims to understand how the datafication of the audience is changing the power dynamics between the public and the journalists that produce the news.

In this paper, we show that introducing these algorithmic-based technologies has impacted the newsmaking process in at least two ways. Firstly, by making journalists cover topics and issues that they feel go against their ideals of newsworthiness but that they feel will perform well with the audience. Secondly, we show here that with this data-driven turn, editorial decision-making power is no longer limited to the editor inside the newsroom but is subjected to a complex set of stakeholders. In catering to a datafied audience, some journalists report feeling conflicted with the topics they need to cover, a phenomenon that could signal a change in legacy media’s capacity to shape public and individual opinions. Therefore, this article discusses the following question: How has the datafication of the audience in the newsroom shifted opinion power in the news production process?

Literature Review

The development of social media departments inside newsrooms and news organizations has directly impacted the popularisation of quantitative audience measurement techniques (Anderson Citation2011; Christin Citation2020). Following the literature on audience metrics, we argue that this change has increased the tension between data-driven approaches to audience measurements and journalistic autonomy (Peterson-Salahuddin and Diakopoulos Citation2020). In a context where media outlets are vying for a place on users’ social media platforms, the need for a more detailed, instant picture of the public behind the screens has forced the industry to find a better way to understand their readers (Tandoc and Vos Citation2016). Consequently, some have argued that audience analytics effectively change the audience's role in constructing the news (Petre Citation2021; Tandoc Citation2014). The public has become a group of atomized individuals who actively seek the information they want to consume and reject, rather strongly, those issues that they dislike (Groot Kormelink and Costera Meijer Citation2014; Wagner and Boczkowski Citation2019). According to the literature, the audience’s personal preferences have become increasingly difficult to disregard for editors and journalists, even in those cases where reporters have a negative perception of technologies for audience measurement (Belair-Gagnon, Nelson, and Lewis Citation2019). The audience’s online behavior is ever-present inside the newsroom, either behind a computer screen or hanging from the ceiling in the middle of the room (Petre Citation2021).

However, the concept of the audience itself needs to be problematized. Unlike previous studies (see Gajardo, Costera Meijer, and Domingo Citation2021), we argue that the audience journalists now engage with is an algorithmic construction and cannot be considered an accurate representation of the audience. Audiences had always influenced the opinion formation process, even before digital platforms existed, either by buying newspapers or choosing what topics to discuss in online forums. However, in the context of metrics, the datafied version of the audience holds the power to shape opinion formation by influencing newsrooms in deciding what is popular. Indeed, journalists writing for an algorithmic public assume a measured audience construction because the information acquired by the journalists are metrics given to them by a third-party, external platform. The knowledge about the audience can therefore be only inferred through this data and is not the result of direct engagement with readers (Bucher Citation2018). Groot Kormelink and Costera Meijer alert, for example, that metrics such as clicks “just capture a limited range of users’ interests or preferences” (Citation2018, 681); therefore, metrics should not be equated with the idea of what people supposedly “want.” According to Zamith (Citation2018), the representation of the audience through detailed metrics has allowed the public to exercise control over the content. However, he also argues that the metrics in the newsroom are still quantified representations of the audience that can misrepresent public interests on a broader level.

News organizations are just one stakeholder interested in increasing technologies related to audience measurement and datafication. The forces behind the quantified representations of the audience can promote third-party stakeholders’ self-interests in different ways, such as controlling the distribution of the information and promoting specific measurements over others (Galloway and Swiatek Citation2018). The control over the virtual representation of the audience and the power to datafy and extract meaning, rankings, and priorities from the audience is, therefore, a new form of data power (Vu Citation2014). Indeed, digital platforms have created a new market and economic model for newsrooms to place their articles (Napoli Citation2010). As Myllylahti argues, “digital journalism has become entwined with the platform ecosystem as news companies distribute their news through platforms to gain audience attention and reader revenue” (Citation2020, 567). In the process of writing for a datafied audience driven by metrics, some journalists have stopped writing—according to their values—for a general audience (Belair-Gagnon and Holton Citation2018). Instead, as a consequence of audience datafication, reporters now write to satisfy the black box algorithms that will distribute their news stories across different digital platforms (Gallagher Citation2017), and therefore for an imperfect datafied audience.

Moreover, perhaps the most exciting characteristic of algorithmic publics for this article is that their composition is often opaque (Gallagher Citation2020). This increases the challenge for journalists to establish first-hand knowledge about their audiences. The literature on this issue has discussed how algorithms are complex “black boxes” not only because the mathematical models can only be understood through their inputs and outputs but because, from a societal perspective, the data-driven decision-making process lacks transparency on many of the algorithmic platforms — such as social media, search engines, and so on (Christin Citation2020). However, the composition of the datafied audience is also opaque. Often newsrooms have no information about how audiences are rendered, how biased or not these compositions may be, and who exactly is represented or left out.

Due to these technological transformations, the popularisation of quantitative audience measurements has successfully modified the news-making and distribution process to encompass the new “measured” audience preferences. Anderson (Citation2011) refers to this phenomenon as “algorithmic public,” a concept that encapsulates the influence those perceptions end up having on the development of news making. This, in part, occurs because data analytics are further employed to determine which content gets covered at the end of the day (Zamith Citation2018). According to Tandoc and Thomas (Citation2015, 246), “this is part of the gradual flattening of the power structure between journalists and their audiences.”

Before presenting the results from our fieldwork, in the following section, we argue that the results that we can observe from the literature on audience metrics and journalistic autonomy can further be problematized through the lens of the concept of opinion power (Neuberger Citation2018). Instead of observing a “flattening of the power structure between journalists and their audiences,” as Tandoc and Thomas put it, we discuss how journalists’ gatekeeping power has slowly shifted from the media to what we call a datafied audience opinion power.

Opinion Power

Opinion power as a normative concept can be defined as the “ability of the media to influence processes of individual and public opinion formation” (Helberger Citation2020, 845). The news media play a fundamental role in realizing democratic values and enable free, open, and independent opinion formation, particularly by acting as guardians of the flow of information, as the forum allowing the public to engage in debate and exchange opinions and viewpoints on a plurality of topics and issues, as well as by acting as public watchdogs (Trappel and Tomaz Citation2021). Because democracy cannot truly function without plurality (Barnett and Townend Citation2015), it is crucial to ensure a democratic distribution of power when it comes to the public sphere, where no one actor may hold a dominant position of opinion power (Karppinen Citation2013). Such a dispersal of power is needed to enable an inclusive debate involving the whole society and representing a diversity of opinions and viewpoints (Baker Citation2006). More precisely, “imbalances in the ability to influence the process of public opinion formation can pose a danger to a pluralistic media landscape and democracy” (Helberger Citation2020, 845).

Due to the news media’s gatekeeping and journalists’ editorial decision-making power, where they select the topics and issues for public debate and broader democratic functions, they wield both opinion and political power (Helberger Citation2020, 843). As Bagdikian argues, media power consists of “carefully avoiding some subjects and enthusiastically pursuing others” (2000, p. 16), thus telling the readers what to think about but also shaping how people think about issues (Kim, Scheufele, and Shanahan Citation2002). This power must not be concentrated but dispersed to prevent far-reaching implications for democracy. Any “structural abilities” to trigger effects on opinion formation alone are relevant. Hence, opinion power must be dispersed to pre-emptively avoid the concentration of power and protect journalistic autonomy, media plurality, and democracy (Neuberger Citation2018).

With the rise of the news platformization (van Dijck, Poell, and Waal Citation2018), these power dynamics are shifting (Diakopoulos Citation2019; Helberger Citation2019). Although a higher level of technologically enhanced participation possibilities can be assumed from the audience perspective, the reallocation of power not only serves individual and public participation. The reallocation of opinion power in the media may trigger increasing power asymmetries, with platforms as providers of data, technology, and infrastructures, and lead to media concentration.

In the context of popularity-driven metrics, opinion power is shifting to those that collect and unlock audiences’ data. The audience itself is here paradoxically powerless because of their limited influence on how they are represented; instead, it is third-party firms and social media companies that construe audiences. The ability to control algorithms and steer information, access user data, create user profiles, and control the digital communication infrastructure are crucial elements that trigger a shift and change in the nature of opinion power (Kristensen Citation2021). More precisely, opinion power is changing because there is a shift over who controls the means to connect with the audience, as well as to define who the audience is and what the audience wants (Dvir-Gvirsman and Tsuriel Citation2022; Nielsen and Ganter Citation2022).

While this development may, in fact, empower a datafied audience, the more significant power shift is towards the platforms and technology companies that provide the “means,” namely infrastructure, metrics, and data. Although news media can reach audiences better by shaping news content based on interests, as understood through data analysis and metrics, they are nonetheless compelled to play by the logic of those that datafy the audience and predict what the audience wants. As Kleis Nielsen and Ganter (Citation2018, 1601–1602) further emphasize, “news media are becoming dependent upon increasingly powerful digital intermediaries that structure the media environment in ways not only we as individual citizens but also large […] powerful organizations have to adapt to.” That development is significant as, despite the news media’s privileges and protections, it is losing control over its communication channels and becomes even more dependent on platforms for connecting with the audience (Meese and Hurcombe Citation2021).

In this context, the power to expose the audience to specific news items and the power to control the way the public is measured is a concept we refer to as datafied audience opinion power.

We, therefore, argue that the shifts in opinion power, loss of control, and increasing dependency on platforms are aspects that may trigger a concentrated media landscape (Simon Citation2022). The concept of opinion power, thus, helps us demonstrate the gradual transformation of power dynamics within newsrooms, from legacy media to those behind generating and analyzing audience data.

Methodology

We conducted several months of newsroom ethnography in two media outlets in Chile to test the impact of the datafied audience opinion power in contemporary multiplatform newsrooms. The fieldwork for this research took place between August 2017 and February 2018 in Santiago, Chile, by this article’s lead author. The duration of the fieldwork was divided equally between the two newsrooms. During the first stage, the lead author conducted ethnographic work, including participant observation, at the television station Canal 13, a Chilean free-to-air television channel. The focus was mainly on the journalists working at Teletrece, Canal 13’s news department and newscast, and T13.cl, its website. During the second fieldwork stage, newsroom ethnography was conducted at La Tercera, a daily newspaper controlled by the Chilean conglomerate Copesa. Data was collected not only from over a dozen interviews but also from informal conversations, messaging apps, field notes, editorial meetings, and semi-structured interviews throughout the fieldwork in these organizations.

By using participant observation, the lead author was able to experience first-hand the rhythms of the relationships between sources, journalists, and platforms. He also had the opportunity to pitch his own stories and witness first-hand what reasons were given to justify the newsworthiness of a story.

The Chilean media market offers a unique opportunity to study how journalism and journalistic practices are changing with the introduction of new technologies. Predominantly closed to external investments until the 1980s, the Chilean economy has experienced an accelerated process of privatization and deregulation in all industrial sectors, including news and entertainment media companies. Unlike other countries in the region, which have substantial subsidies and state benefits for the creation of state-public media outlets, Chilean television channels and newspapers, with some exceptions (see Wiley Citation2006), have had to invest large amounts of their own capital in bolstering the technological innovations in their newsrooms. The competition to capture the ever-more connected and ever-more fragmented audience has encouraged media conglomerates to seek new and better strategies to report the news, including the injection and adaptation of state-of-the-art digital tools inside their newsrooms (Gronemeyer Citation2013).

This is why the Chilean market is an excellent case to study the use of popularity-driven metrics. While today the media sector in Chile is smaller than other countries in the region, such as Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina, “it is particularly dynamic, predominantly market-driven, and mostly open to foreign investors” (Godoy Citation2016, 641). For Godoy, the fact that digital infrastructure in Chile is owned “by a few powerful, large telecom companies” (643) explains the rush of technological investment that media companies have experienced in recent decades to control the market and increase their profits.

The methodology for this research was particularly useful because ethnography aims to “make direct contact with social agents in the normal courses and routine situations of their lives to try to understand something of how and why these regularities take place” (Willis Citation2013, xiii); consequently, the strength and value of newsroom ethnographies like the one we present here, is that they enable an analysis of journalistic practices and newsroom structures concurrently (Willig Citation2013). For Bishara, ethnography on media production “makes clear that news is not the product of a narrow, unified ideology. Instead, it is shaped by journalism’s on-the-ground and collaborative – though by no means egalitarian – exchanges” (Citation2013, 24). Bishara highlights the complex chain of production, which is often overlooked by the media audience and consumers and even by media researchers responsible for the publication and broadcasting of news bits, which is under no circumstance the product of the work of one journalist alone. Similarly, Peterson argues that “to understand what a journalist writes, it is necessary to understand his or her place in the journalistic field [and] the status of the newspaper for which the journalist writes” (Citation2003, 81). Thus, by drawing on the data collected during months of ethnographic work, we were able to analyze journalists’ responses during interviews, their daily interactions with audience metric technologies, and colleagues and editors who were also involved in using these technologies.

The data from the interviews, field notes, and chat groups were analyzed using an inductive technique. This ensures that once the raw data was analyzed between the co-authors, our results were conceived from the data itself rather than pre-established categories in the literature (Sandelowski Citation2004).

In the following sections, we present the results from this seven-month-long fieldwork. We aim to examine how audience metric technologies have affected the datafied audience’s power to influence news-making processes inside two Chilean newsrooms.

Results

During the fieldwork at Teletrece, it was common to hear the phrase, “Yes! That would do very well on social networks!” This sentence not only indicated the approval and encouragement of the web editors but also denoted that the journalist who had asked whether to cover a topic had stumbled upon a rather enviable gem. “A tingling of excitement wounded its way along my spine every time I heard the thrill in my editor's voice; but what topic are we about to cover that is going to break the Internet, I wondered” (Field note, lead author, 2017).

Over the months of fieldwork in Canal 13, the lead author for this article was assigned the workstation right across the alley from the content editor of T13.cl. Hence, it was easy to overhear the editor’s conversations with other journalists trying to pitch a story on their own or scrounging around to find something new to write about. Only on rare occasions the editor rejected an idea or lead for a story up front. Instead, he would usually have proposed a better angle or a different argument to report the same event.

Nevertheless, this “would do very well in social networks” sentence appeared to be used indistinctively for many subjects that did not seem to be related to each other. According to the field notes collected during that time, the editor used this phrase when he was referring to news articles about Grey’s Anatomy, the Cirque du Soleil, and Kim Kardashian. We are naming those topics because not all the medical dramas on television, or entertainment or circus events, or even members of the Kardashian family received the same type of reaction and attention from the editor.

My excitement would soon fade away when I realized that what would have been a significant impact on social media was a story about a returning character or the latest unexpected pregnancy in Grey’s Anatomy, a long-running medical drama on ABC (United States). But as time went by, I started wondering how my editor had this alarming level of specificity in his knowledge regarding which topic would end up doing well, that is to say, having a significant impact on social networks. (Field note, lead author, 2017).

“Our audience is very, very strange,” the web content editor said with a snigger. “It is not a homogenous audience. We have two types of audiences at the same time.” One of these audiences, he argued, is a 16 years-old, “super-young,” heavy Facebook user. “I know that writing about Selena Gomez will cause such a furor among them […]. I know that any of these it girls-things will always work,” he added.

“So, today, for example, I saw Selena Gomez giving a speech. She started crying because one of her friends gave her a kidney for a transplant, and I knew immediately that this article was going to work,” he said quite unabashedly. After the interview, the data from Chartbeat was checked. Indeed, Selena Gomez’s kidney transplant article had at least 500 concurrent readers on the website all morning; A good number for this newsroom’s metrics.

After it was created in 2014, the main objective of T13 was to create an influential website to captivate their television audience when they were not at home watching TV. As a social networks editor put it during our interview, this was an important step for the station because social networks would be the way to capture new audiences and bring traffic to the site; “it is how we tell people what is happening on the TV news,” especially younger generations who do not necessarily turn on their televisions when they are home.

Each social network utilized by Teletrece now has its own target group. Initially, the editor remembered, Twitter was considered equal to Facebook, and his team published the same type of information on both: politics, business, viral stories, sports, international, and so on. However, they gradually realized that Twitter was not producing significant traffic on the site but was instead generating considerable levels of influence. People retweeted and commented on Teletrece’s posts more than they clicked on them. The tweet itself, rather than the news article, was the product with which users interacted more frequently. Therefore, they decided to utilize Twitter to address politics (including politicians’ quotes) and breaking news. Facebook, however, would be employed to “post the most important news of the day, but also to enhance fans’ loyalty, to chat with them, to read their opinions, to generate interaction,” argued a social networks editor. This decision was not random. According to this editor, if social networks brought approximately 70% of the traffic to T13.cl, then Facebook was responsible for 90% of that. Perhaps, however, what he said immediately after was most revealing: “Because Facebook is an incredible traffic generator, we look for the best way to make our content go viral, utilizing Facebook’s language.” This meant, he said as an example, that if the news on television told a story with the most significant bits of news at the end, then the social network team would rearrange that, so the most important information was at the beginning of the post. Another example was the usage of titles as cliffhangers, which pushed the audience to click on the title if they wished to know “what part of your breakfast could be giving you cancer.” “We need to capture the attention of the guy on his phone who has 8,000 tabs open. […] The first 10 seconds are really important,” the editor explained. The report offered by Google Analytics proved his point. At the time of that interview, the lead author for this article checked the metrics online; indeed, 75% of the total audience (n = 2,454 at that moment) was accessing the website via mobile phones, with the majority of active users coming from Facebook.

However, the phrase “Facebook’s language” was perhaps the most interesting bit of his answer. He did not say “T13’s language” or “journalists’ language;” instead, he said “Facebook’s language.” Facebook is not only a social media platform but also a real, material company with office buildings, paid workers, economic interests, and lobby representatives in Chile. Consequently, the social networks editor was asked directly about their relationship with Facebook:

We have to play along because they are … Imagine this is a big supermarket, and they are the shelves. So, if we follow what they tell us to do, they will put us on a very visible shelf; otherwise, they will put us on the back, where nobody can see us.

Journalists, however, often resented the number of stories they had to write about Grey’s Anatomy, Friends, and other TV programs or celebrity culture. Although these stories offered satisfactory reception by the datafied audience, they fell outside what the journalists felt was newsworthy and created an increasing feeling of professional dissonance in their work — a mismatch between professional values and job tasks.

As a result of the new digital platforms that have overtaken the publishing process, journalists have real-time insight regarding what kind of information the datafied audience is consuming. Thus, the temptation for those profiting from advertisements is difficult to resist. This has been empirically proven by Welbers et al., who, after analyzing the print and online editions of five Dutch newspapers, conclude that “using a cross-lagged analysis covering six months, we found that storylines of the most-viewed articles were more likely to receive attention in subsequent reporting, which indicates that audience clicks affect news selection” (Citation2016, 1037). We saw this in action during the fieldwork: when in doubt, Teletrece’s content editor would publish an online story about events in “that show” to lure readers to the website, as this strategy had proven successful on the web.

One of the social media journalists interviewed during the fieldwork at La Tercera offered additional insight into this process: someone who did not write articles or did any reporting but picked which of those written by the digital and paper journalists they thought would succeed on the platforms because, as he stated, “We already know which type of news would “have a click;” for example, an article about two pandas that had a baby panda. … Animals are a hit on Facebook,” he explained. Although this may seem like a trivial story, it indicates a preference or priming for specific topics over others, highlighting and rewarding the work of those who write less informative political news and cultural content in exchange for “hits for the web.” Their awareness is limited regarding this issue; hence, the same team member later added, “Sometimes there are articles that we do not put on the networks, but that are receiving a lot of visits anyway, so we would post them on Facebook and Twitter anyway.” The social media team’s work was to determine what type of article would generate the most traffic on social media platforms rather than to understand the newsworthiness of the topic itself.

Journalists may resent the number of articles they must produce about Grey’s Anatomy and other TV and reality programs. However, they have also learned to utilize these publications to satisfy their own journalistic ideals and reduce the level of professional dissonance in their daily work. As the social networks editor said during the interview, “Using social networks is the way to capture new audiences, is the way to get traffic to the site, it is how we let people [who only consume online news] know what it is happening on our television news, or in our radio station, or what it is happening on T13.” News articles that “do well” with the datafied audience according to the KPIs of software like Chartbeat and platform like Facebook were being utilized as a lure to capture the attention of the social media users and bring them to the homepage of the media organizations, where journalists felt it was easy placing stories that complied with their journalistic ethos.

In some ways, digital journalists were utilizing gossip and reality programs as a hook to bring digital platforms’ users to the website. Once the user entered the T13 homepage, then they were exposed to the rest of the content that journalists felt was less appropriate for social media but more interesting from a journalistic perspective. As a digital reporter told us during an interview, “There are decisions that I make because of the clicks, but there are also decisions that I take against the clicks. Some things are important for the audience to know, even when most people will not [click on them and] read it, but these are things that they need to know.” Instead of submitting to the pressures of the platformization of news, some journalists, particularly at T13, were hacking the way these platforms work, “testing [and tempting] the audience with topics that are safe bets,” a digital reporter told me, to increase the traffic to the website, where a less clickable story waits to be read. As Duffy and Cheng argue, “traditional newsroom practice has been that editorial and commercial operate under contradicting values which require partition” (Citation2022, 1). According to these authors, when that “wall” falls, media workers enter a state of cognitive dissonance in which they struggle to understand how things should be and how they are. To reduce this feeling of discomfort, we found journalists at Canal 13 attempting to hack the system by utilizing external social media platforms to attract readers to the website with clickable stories, where, in their words, “the worthy” information was waiting for them. It was a mechanism to solve conflicting values by doing things the way they were done without stopping to cover those topics that should be covered.

Discussion

In this article, we argued that opinion power has shifted from audience preferences to an increased metrification of the audience produced by third-party platforms because journalists and editors are increasingly focusing on audience metrics for deciding which topics to cover. The metrics, in turn, also serve as a signal to validate journalists’ perceived importance levels of issue salience.

As the interviews during fieldwork show, it is now the datafied version of the audience that holds power to influence newsrooms’ decisions about what should be covered. For example, in Teletrece, although journalists cannot understand how Facebook constructs its audiences, editors decided to cover news about Mexican shows to bring positive metrics into the newsroom.

Popularity-driven metrics made the importance of the news content secondary to the success that a story could have on different platforms. This case also suggests higher possibilities of audience participation due to technological interactions, as the Mexican public can demand more content of their interest on a Chilean website. However, it also shows how the reallocation of opinion power is increasing power asymmetries because platforms like Facebook or Twitter provide the data, technologies, and infrastructures to link datafied audiences with newsrooms worldwide.

Something similar happened in La Tercera. Facebook’s and Twitter’s representation of the audience and decision on what metrics are essential for news making have made journalists enthusiastically pursue news stories about baby pandas and zoo animals. Journalists might be guiding their work not by the editorial newsworthiness of a story but by the likelihood that the piece would become “a hit on social media,” as one of the social media journalists put it.

Under these circumstances, audience metrics indirectly affect opinion power because they influence what and how journalists and editors decide to publish. However, the power to shift to audience metrics does not directly resonate with an authentic audience representation but rather with a datafied version of the public created by different stakeholders like Chartbeat, Facebook, or Google Analytics. Each platform utilizes different models to estimate engagement depending on their respective key performance indicators (KPIs). It would therefore be more precise to identify the power shift in the digital context as the datafied audience opinion power. With the introduction of new audience metric technologies, it might not be the journalists or editors alone who decide what is relevant to the public. Instead, the values behind a third-party company’s measurement technologies and an aggregate of what has been measured as the preferences and interests of the audience increasingly influence decision-making.

Consequently, the platformization of news is increasing the datafied audience opinion power by making journalists more dependent on those who measure, analyze, and predict the audience.

This research occurred in an ecosystem of highly data-driven news production, distribution, and consumption in which popularity-driven metrics increasingly inform editorial decisions and other audience metrics (Christin Citation2020; Kristensen Citation2021; Petre Citation2021). Journalists are progressively pressured to perform well to satisfy the datafied audience (Anderson Citation2011; Christin Citation2020). Thus, feelings of professional anxiety begin to proliferate across multiplatform newsrooms. To reduce this dread that reporters are experiencing, media workers may oppose the increasing opinion power of the datafied audience or the obscure algorithm of third-party platforms behind audience metrics (Anderson Citation2011). However, this would disrupt existing production patterns and potentially negatively affect advertising revenues. Although news organizations depend on a process of active bureaucracy (Salinas Muñoz and Stange Marcus Citation2015) and flexible negotiations between reporters and editors (Gessesse Citation2020; Mellado Citation2020), third-party platforms exercise indirect opinion power by the way they datafy the audience, as their production and analysis, in the end, determine what journalists write. Contesting the algorithms behind digital platforms will disrupt the already established practices with which media organizations have decided to work (Hanusch Citation2017). In this way, the “flexible negotiations” between journalists and editors become less open, less of a compromise between the two, and more of a mandate of how journalists need to feed third-parties’ algorithms. Journalists have less room to protest, and the gap between values and practices becomes ever wider (Bastian, Helberger, and Makhortykh Citation2021; Dodds Citation2019).

In this study, we observed three competing—and often conflicting—influences and stakeholders: what journalists report as newsworthy, what the data collected by software like Chartbeat suggests users find newsworthy and engaging, and what platforms would like to see go viral because of good advertising. The new audience metric technologies are forcing journalists to cover topics they deem irrelevant or improper for their profession (Wendelin, Engelmann, and Neubarth Citation2017). This is not to say, nor do we argue in this paper, that clicks are an accurate reflection of the audience (Bucher Citation2018). These measurements are but a statistical representation of the engagement of some and overrepresented part of the public (Ferrer-Conill and Tandoc Citation2018). The under or overrepresentation of specific sectors of the audience necessarily raises ethical questions about the non-representation of others and how the focus on more audience orientation can move the media agenda away from serving communities that are less visible in the data from an algorithmic perspective. The example of the Mexican audience that consumes local entertainment news on a Chilean website is particularly telling, as it shows that journalists struggle to make sense of their audiences.

Interestingly, the audience remains, in addition to that, a somewhat abstract mass of people, despite all the promises of data-driven audience insights. According to the interviewed editors, despite some identifiable variables such as age, platform usage, and country of origin, the audience's vision within these newsrooms is not necessarily representative of the real audience, which is problematic when this data is so prominent in influencing editors’ decisions.

In this article, we have argued that a shift is observable in the opinion power of the datafiers of the audience. Journalists have now taken a more passive role as consumers of (audience) data. In contrast, the audience is perceived as an active agent that clicks, comments, shares their preferences, and informs the work of media professionals within newsrooms (Gallagher Citation2017; Vu Citation2014). However, the editorial decisions by editors are further influenced by a growing array of external parties and stakeholders such as social media engagement editors, marketing departments, Chartbeat, and perhaps most importantly, social media platforms like Facebook and Google.

With that in mind, one could wonder where the agenda-setting power sits these days. The growing opinion power that the datafied audience enjoys is only sustained by the algorithmic decisions that external platforms like Facebook are taking. Once that changes, the entire balance of power in newsmaking could get transformed as well.

Based on our results and field observations and following our research question — How has the datafication of the audience in the newsroom shifted opinion power in the news production process? — we concluded that there had been a power shift from the audience and newsroom to audience metrics and those who define and construe them. We argue that rather than giving power to the audience, these metrics are shifting the opinion power to a measure and datafied version of the public created by digital platforms. This ultimately concentrates power in those platforms that can construct the audience and distribute the content, a process we call datafied audience opinion power.

Conclusion

In this research, we conceptualized audience metrics’ influence on news production. We approached the study of the impact of metrics on the newsrooms through the lens of opinion power, for journalists and editors are no longer the only decision-makers of the relevant news for the public. We argue that a shift in the audience’s opinion power is in place. In the context of popularity-driven metrics, this article argues that opinion power is shifting from legacy media to a datafied version of the audience and other stakeholders, producing a mismatch between journalists’ professional values and job tasks.

Although the actions performed by the audience seem to inform newsrooms on journalistic content preferences, external parties can quickly determine the content audiences react to and modify the way metrics are constructed. Thus, the editorial practices in the newsrooms are affected mainly by other stakeholders such as Facebook and Google. Most importantly, this audience construction is often an opaque process determined by third-party institutions.

Moreover, we also found that newsrooms guide their content based on the representation of the public without considering the non-represented audience that does not necessarily engage with news. Thus, it is essential to re-consider the role of journalists and editors serving the public reflected in the metrics. In this context, journalists, guided by their professional values, still try to accommodate the situation and consider ways to inform the audience with news that need to be known by the public. However, journalists may not be rewarded by the metrics. This tension between audience metrics and the willingness to inform the public constantly makes journalists feel under pressure to perform well through the lens of the metrics. In addition, contrary to other measurements, such as television ratings, the current metrics create a sense of competition between journalists in the newsroom.

Our results are not without limitations. For instance, the methodology in place can elicit journalists to provide socially desirable responses, although the combination of observation and interviews helped us to avoid those biases.

Although the data for this article was collected between 2017 and 2018, our results transcend ephemerality. As we have shown, popularity-driven metrics and dependency on social media platforms are only increasing in news organizations worldwide. We believe that scholars working on similar issues should still be able to observe the ongoing datafication of the audience, its impact on the news agenda, and the dependency on platforms.

Moreover, every newsroom is different; comparing these observations with other institutions is essential. In this sense, future research should study the relationship between journalistic digital platforms such as Chartbeat and social media news intermediaries like Twitter or Facebook. Future studies should also research the influence of audience metrics on agenda-setting power to quantify its impact on the public.

We encourage future scholars to focus on the neutrality of data and analytics companies such as Chartbeat. Some possible questions include: What is the relationship between Chartbeat and digital platforms such as Twitter and Facebook? Is datafication empowering platforms like Chartbeat and Facebook to exercise influence on the agenda-setting power of the media, further taking away power from the audience? An aspect that needs to be addressed is the politics behind metrics, namely, the political considerations of those who collect and analyze the data and the process of analyzing the data itself. As these technologies only seem to be getting more popular, and newsrooms are even more dependent on this data, we need to understand better the full dynamics behind the new datafied audience opinion power.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 According to the Chartbeat website, concurrent visitors are measured as ‘the total number of people on your site at any given moment, as measured by the number of simultaneous open browsing sessions to your site’.

References

- Anderson, C. 2011. “Between Creative and Quantified Audiences: Web Metrics and Changing Patterns of Newswork in Local US Newsrooms.” Journalism 12 (5): 550–566. doi:10.1177/1464884911402451.

- Baker, C. E. 2006. Media Concentration and Democracy: Why Ownership Matters. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511810992

- Barnett, S., and J. Townend. 2015. “Plurality, Policy and the Local.” Journalism Practice 9 (3): 332–349. doi:10.1080/17512786.2014.943930.

- Bastian, M., N. Helberger, and M. Makhortykh. 2021. “Safeguarding the Journalistic DNA: Attitudes Towards the Role of Professional Values in Algorithmic News Recommender Designs.” Digital Journalism 9 (6): 835–863. doi:10.1080/21670811.2021.1912622.

- Belair-Gagnon, V., and A. E. Holton. 2018. “Boundary Work, Interloper Media, And Analytics In Newsrooms.” Digital Journalism 6 (4): 492–508. doi:10.1080/21670811.2018.1445001.

- Belair-Gagnon, V., J. L. Nelson, and S. C. Lewis. 2019. “Audience Engagement, Reciprocity, and the Pursuit of Community Connectedness in Public Media Journalism.” Journalism Practice 13 (5): 558–575. doi:10.1080/17512786.2018.1542975.

- Bishara, A. A. 2013. Back Stories: U.S. News Production and Palestinian Politics. Stanford University Press.

- Blanchett Neheli, N. 2018. “News by Numbers.” Digital Journalism 6 (8): 1041–1051. doi:10.1080/21670811.2018.1504626.

- Bucher, T. 2018. If … Then: Algorithmic Power and Politics. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190493028.001.0001

- Carlson, M. 2018. “Confronting Measurable Journalism.” Digital Journalism 6 (4): 406–417. doi:10.1080/21670811.2018.1445003.

- Christin, A. 2018. “Counting Clicks: Quantification and Variation in Web Journalism in the United States and France.” American Journal of Sociology 123 (5): 1382–1415. doi:10.1086/696137.

- Christin, A. 2020. Metrics at Work: Journalism and the Contested Meaning of Algorithms. Princeton University Press. https://press.princeton.edu/books/ebook/9780691200002/metrics-at-work.

- Coddington, M., S. C. Lewis, and V. Belair-Gagnon. 2021. “The Imagined Audience for News: Where Does a Journalist’s Perception of the Audience Come from?” Journalism Studies 22 (8): 1028–1046. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2021.1914709.

- Diakopoulos, N. 2019. Automating the News: How Algorithms Are Rewriting the Media (Illustrated edition). Harvard University Press.

- Dodds, T. 2019. “Reporting with WhatsApp: Mobile Chat Applications’ Impact on Journalistic Practices.” Digital Journalism 7 (6): 725–745. doi:10.1080/21670811.2019.1592693.

- Duffy, A., and L. Cheng. 2022. ““It’s Complicated”: Cognitive Dissonance and the Evolving Relationship Between Editorial and Advertising in US Newsrooms.” Journalism Practice 16: 87–102. doi:10.1080/17512786.2020.1804986.

- Dvir-Gvirsman, S., and K. Tsuriel. 2022. “In an Open Relationship: Platformization of Relations Between News Practitioners and Their Audiences.” Journalism Studies 23: 1308–1326. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2022.2084144.

- Fengler, S., and S. Ruß-Mohl. 2008. “Journalists and the Information-Attention Markets: Towards an Economic Theory of Journalism.” Journalism 9 (6): 667–690. doi:10.1177/1464884908096240.

- Ferrer-Conill, R., and E. C. Tandoc. 2018. “The Audience-Oriented Editor.” Digital Journalism 6 (4): 436–453. doi:10.1080/21670811.2018.1440972.

- Fletcher, R., and R. K. Nielsen. 2017. “Are News Audiences Increasingly Fragmented? A Cross-National Comparative Analysis of Cross-Platform News Audience Fragmentation and Duplication.” Journal of Communication 67 (4): 476–498. doi:10.1111/jcom.12315.

- Fürst, S. 2020. “In the Service of Good Journalism and Audience Interests? How Audience Metrics Affect News Quality.” Media and Communication 8 (3): 270. doi:10.17645/mac.v8i3.3228.

- Gajardo, C., I. Costera Meijer, and D. Domingo. 2021. “From Abstract News Users to Living Citizens: Assessing Audience Engagement Through a Professional Lens.” Journalism Practice 0(0): 1–17. doi:10.1080/17512786.2021.1925949.

- Gallagher, J. R. 2017. “Writing for Algorithmic Audiences.” Computers and Composition 45: 25–35. doi:10.1016/j.compcom.2017.06.002.

- Gallagher, J. R. 2020. “The Ethics of Writing for Algorithmic Audiences.” Computers and Composition 57: 102583. doi:10.1016/j.compcom.2020.102583.

- Galloway, C., and L. Swiatek. 2018. “Public Relations and Artificial Intelligence: It’s not (Just) About Robots.” Public Relations Review 44 (5): 734–740. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2018.10.008.

- Gessesse, K. B. 2020. “Mismatch Between Theory and Practice? Perceptions of Ethiopian Journalists Towards Applying Journalism Education in Professional News Production.” African Journalism Studies 41 (1): 49–64. doi:10.1080/23743670.2020.1735470.

- Godoy, S. (2016). Media Ownership and Concentration in Chile. In E. M. Noam (Ed.), Who Owns the World’s Media?: Media Concentration and Ownership Around the World. Oxford University Press.

- Gronemeyer, M. E. 2013. “Digitalization and its Effect on Journalism Products and Practices in Chile.” Palabra Clave - Revista de Comunicación 16 (1): 101–128. doi:10.5294/pacla.2013.16.1.4.

- Groot Kormelink, T., and I. Costera Meijer. 2014. “Tailor-Made News.” Journalism Studies 15 (5): 632–641. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2014.894367.

- Hanusch, F. 2017. “Web Analytics and the Functional Differentiation of Journalism Cultures: Individual, Organizational and Platform-Specific Influences on Newswork.” Information, Communication & Society 20 (10): 1571–1586. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2016.1241294.

- Helberger, N. 2019. “On the Democratic Role of News Recommenders.” Digital Journalism 7 (8): 993–1012. doi:10.1080/21670811.2019.1623700.

- Helberger, N. 2020. “The Political Power of Platforms: How Current Attempts to Regulate Misinformation Amplify Opinion Power.” Digital Journalism 8 (6): 842–854. doi:10.1080/21670811.2020.1773888.

- Karppinen, K. 2013. Rethinking Media Pluralism. Fordham University Press. doi:10.5422/fordham/9780823245123.001.0001

- Kim, S.-H., D. A. Scheufele, and J. Shanahan. 2002. “Think About It This Way: Attribute Agenda-Setting Function of the Press and the Public’s Evaluation of a Local Issue.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 79 (1): 7–25. doi:10.1177/107769900207900102.

- Kleis Nielsen, R., and S. A. Ganter. 2018. “Dealing with Digital Intermediaries: A Case Study of the Relations Between Publishers and Platforms.” New Media & Society 20 (4): 1600–1617. doi:10.1177/1461444817701318.

- Kormelink, T. G., and I. C. Meijer. 2018. “What Clicks Actually Mean: Exploring Digital News User Practices.” Journalism 19 (5): 668–683. doi:10.1177/1464884916688290.

- Kristensen, L. M. 2021. “Audience Metrics: Operationalizing News Value for the Digital Newsroom.” Journalism Practice 0(0): 1–18. doi:10.1080/17512786.2021.1954058.

- Lamot, K., and S. Paulussen. 2020. “Six Uses of Analytics: Digital Editors’ Perceptions of Audience Analytics in the Newsroom.” Journalism Practice 14 (3): 358–373. doi:10.1080/17512786.2019.1617043.

- Lamot, K., and P. Van Aelst. 2020. “Beaten by Chartbeat?” Journalism Studies 21 (4): 477–493. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2019.1686411.

- Meese, J., and E. Hurcombe. 2021. “Facebook, News Media and Platform Dependency: The Institutional Impacts of News Distribution on Social Platforms.” New Media & Society 23), doi:10.1177/1461444820926472.

- Mellado, C. 2020. Beyond Journalistic Norms: Role Performance and News in Comparative Perspective. Routledge.

- Moyo, D., A. Mare, and T. Matsilele. 2019. “Analytics-Driven Journalism? Editorial Metrics and the Reconfiguration of Online News Production Practices in African Newsrooms.” Digital Journalism 7 (4): 490–506. doi:10.1080/21670811.2018.1533788.

- Myllylahti, M. 2020. “Paying Attention to Attention: A Conceptual Framework for Studying News Reader Revenue Models Related to Platforms.” Digital Journalism 8 (5): 567–575. doi:10.1080/21670811.2019.1691926.

- Napoli, P. M. (2010). Audience Evolution: New Technologies and the Transformation of Media Audiences (p. 272). Columbia University Press.

- Neuberger, C. 2018. “Meinungsmacht im Internet aus kommunikationswissenschaftlicher Perspektive.” UFITA 82 (1): 53–68. doi:10.5771/2568-9185-2018-1-53.

- Nielsen, R. K., and S. A. Ganter. 2022. The Power of Platforms: Shaping Media and Society. Oxford University Press.

- Nixon, B. 2020. “The Business of News in the Attention Economy: Audience Labor and MediaNews Group’s Efforts to Capitalize on News Consumption.” Journalism 21 (1): 73–94. doi:10.1177/1464884917719145.

- Peterson-Salahuddin, C., and N. Diakopoulos. 2020. “Negotiated Autonomy: The Role of Social Media Algorithms in Editorial Decision Making.” Media and Communication 8 (3): 27. doi:10.17645/mac.v8i3.3001.

- Peterson, M. A. 2003. Anthropology & Mass Communication: Media and Myth in the New Millennium. Berghahn Books.

- Petre, C. 2015, May 7. The Traffic Factories: Metrics at Chartbeat, Gawker Media, and The New York Times. Columbia Journalism Review. https://www.cjr.org/tow_center_reports/the_traffic_factories_metrics_at_chartbeat_gawker_media_and_the_new_york_times.php/.

- Petre, C. 2021. All the News That’s Fit to Click: How Metrics Are Transforming the Work of Journalists. Princeton University Press.

- Powers, E. 2018. “Selecting Metrics, Reflecting Norms.” Digital Journalism 6 (4): 454–471. doi:10.1080/21670811.2018.1445002.

- Salinas Muñoz, C., and H. Stange Marcus. 2015. “Burocratización de las rutinas profesionales de los periodistas en Chile (1975-2005).” Cuadernos Info 0 (37): 121–135.

- Sandelowski, M. 2004. “Using Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Health Research 14 (10): 1366–1386. doi:10.1177/1049732304269672.

- Simon, F. M. 2022. “Uneasy Bedfellows: AIrjrin the News, Platform Companies and the Issue of Journalistic Autonomy.” Digital Journalism 10 (10): 1832–1854. doi:10.1080/21670811.2022.2063150.

- Tandoc, E. C. 2014. “Journalism is Twerking? How Web Analytics is Changing the Process of Gatekeeping.” New Media & Society 16 (4): 559–575. doi:10.1177/1461444814530541.

- Tandoc, E. C., and R. J. Thomas. 2015. “The Ethics of Web Analytics.” Digital Journalism 3 (2): 243–258. doi:10.1080/21670811.2014.909122.

- Tandoc, E. C., and T. P. Vos. 2016. “The Journalist Is Marketing the News.” Journalism Practice 10 (8): 950–966. doi:10.1080/17512786.2015.1087811.

- Thurman, N., and M. Myllylahti. 2009. “Taking the Paper Out of News.” Journalism Studies 10 (5): 691–708. doi:10.1080/14616700902812959.

- Trappel, J., and T. Tomaz. 2021. “Democratic Performance of News Media: Dimensions and Indicators for Comparative Studies.” In The Media for Democracy Monitor 2021: How Leading News Media Survive Digital Transformation: Vol. 1, edited by J. Trappel, and T. Tomaz, 11–58. Nordicom. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:norden:org:diva-12100.

- Usher, N. 2013. “Al Jazeera English Online.” Digital Journalism 1 (3): 335–351. doi:10.1080/21670811.2013.801690.

- van Dijck, J., T. Poell, and M. de. Waal. 2018. The Platform Society: Public Values in a Connective World. Oxford University Press.

- Vu, H. T. 2014. “The Online Audience as Gatekeeper: The Influence of Reader Metrics on News Editorial Selection.” Journalism 15 (8): 1094–1110. doi:10.1177/1464884913504259.

- Wagner, M. C., and P. J. Boczkowski. 2019. “The Reception of Fake News: The Interpretations and Practices That Shape the Consumption of Perceived Misinformation.” Digital Journalism 7 (7): 870–885. doi:10.1080/21670811.2019.1653208.

- Walters, P. 2022. “Reclaiming Control: How Journalists Embrace Social Media Logics While Defending Journalistic Values.” Digital Journalism 10 (9): 1482–1501. doi:10.1080/21670811.2021.1942113.

- Welbers, K., W. van Atteveldt, J. Kleinnijenhuis, N. Ruigrok, and J. Schaper. 2016. “News Selection Criteria in the Digital Age: Professional Norms Versus Online Audience Metrics.” Journalism 17 (8): 1037–1053. doi:10.1177/1464884915595474.

- Wendelin, M., I. Engelmann, and J. Neubarth. 2017. “User Rankings and Journalistic News Selection.” Journalism Studies 18 (2): 135–153. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2015.1040892.

- Wiley, S. B. C. 2006. “Transnation: Globalization and the Reorganization of Chilean Television in the Early 1990s.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 50 (3): 400–420. doi:10.1207/s15506878jobem5003_4.

- Willig, I. 2013. “Newsroom Ethnography in a Field Perspective.” Journalism 14 (3): 372–387. doi:10.1177/1464884912442638.

- Willis, P. 2013. The Ethnographic Imagination. John Wiley & Sons.

- Zamith, R. 2018. “Quantified Audiences in News Production.” Digital Journalism 6 (4): 418–435. doi:10.1080/21670811.2018.1444999.