ABSTRACT

Media freedom has deteriorated across the world over the past 15 years with populist leaders attacking journalism in both democratic and repressive states. Since the rise of online misinformation and disinformation, concern is growing that governments are using fake news language and related laws to muzzle the press. Studies find labelling reporters and their stories as fake news can threaten journalistic norms and practices and have implications for trust relationships with sources and audiences. Less understood is the effects of fake news laws on journalism. This article addresses this gap and examines consequences for journalistic practices in Singapore and Indonesia when journalists and sources are targets of fake news laws. Through 20 in-depth expert interviews with journalists, editors, their sources and fake news experts in Indonesia and Singapore, the article identifies “chill effects” on reporting when faced with the threat of new legal sanctions. However, it also identifies adaptations to newsroom practices to manage this threat. We conclude with lessons learned from the Asia Pacific on how journalists in other jurisdictions might manage the potential chilling effects on news reporting when fake news laws are in place.

Introduction

With the global spread of COVID-19 misinformation and disinformation, reining in fake news on digital platforms has become a top-level policy concern for governments around the world. Inaccurate information circulating online can counter public health messages and lead to serious harm, or even death, when people rely on falsehoods about dangerous COVID-19 treatments (Shepherd Citation2020). Acknowledging the extent of the problem, the World Health Organisation labelled the online spread of COVID-19 misinformation and disinformation a global “infodemic” (World Health Organisation Citation2021).

While the urgency of tackling fake news online is not in dispute, how to mitigate online falsehoods is by no means clear-cut or a one-size-fits-all approach. Meese and Hurcombe (Citation2020, 3) identify three distinct political approaches that governments around the world have taken to address this serious problem. They include: (i) non-regulatory “supporting activities” such as government funding of digital literacy campaigns and fact-checking units to mitigate the harm of online falsehoods; (ii) voluntary or mandatory co-regulatory measures involving digital platforms and existing media authorities; and (iii) legislative measures such as anti-fake news laws. As the number of countries that have adopted these laws (colloquially known as fake news laws) grows, so too does concern about the political motivations for introducing such laws and their impacts on press freedom (Mchangama and Fiss Citation2019; Carson and Fallon Citation2021).

This article focuses on the impacts on journalists and their sources when countries respond to the problem of online falsehoods by taking the third option: a legislative approach. Among the countries adopting fake news laws are states that already limit the political and media freedoms of their citizens (Mchangama and Fiss Citation2019, 17). In the Asia Pacific, two early adopters are Singapore, with its 2019 Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA), and Indonesia’s 2016 Information and Electronic Transactions Law (ITE).

Singapore and Indonesia are pertinent case studies to examine the impact of fake news laws on media, politics, and public discourse for several reasons. First, these laws have influenced other governments’ responses to online misinformation and disinformation and are credited with shaping the legislative responses in Malaysia, Nigeria, and Sri Lanka (Teo Citation2021a). Second, as the next section details, Singapore and Indonesia have a history of suppressing media and political freedoms and are currently rated in democracy indices as states that are “partly-free” (Freedom House Citation2021b; Citation2021a). Singapore scored 48 out of 100 on Freedom House’s Global Freedom Index (Freedom House Citation2021b) and is in the lowest quartile for press freedom, scoring 160 out of 180 countries on the Press Freedom Index (Reporters without Borders Citation2021b). Similarly, Indonesia scored 59 out of 100 on Freedom House’s index (Freedom House Citation2021a) and is ranked 113 out of 180 on the Press Freedom Index (Reporters without Borders Citation2021a). Third, Singapore and Indonesia are understudied countries in misinformation and disinformation scholarship, which tends to originate from the United States and Europe. Understanding their experiences is important as the two countries cover a large proportion of the Asia Pacific population and are influential leaders in the region (Teo Citation2021a).

We address this research gap with the aim of understanding how Singapore and Indonesia’s legislative responses to online misinformation and disinformation impact on journalism practices and reporters’ relationships with their sources. We do so by undertaking semi-structured interviews with key informants to examine how journalists and their sources fulfil their normative functions in the public sphere (McNair Citation2018, 24–25). These include informing and educating the public, providing a forum for political discourse, a place for dissent and advocacy, and holding power to account in a political environment where politicians enact laws that enshrine them as both the architects and arbiters of what is fake news.

We find fake news laws in both countries are having a chilling effect on journalism, but not enough to deter independent reporting. A “chilling effect” is a term originating from the United States to describe how the threat of legal sanction (such as lengthy, complex defamation lawsuits) against journalists can “chill” media speech and thus limit the quality of public debate about political and public interest matters (Marjoribanks and Kenyon Citation2003, 2). In this paper, we apply the term to journalists’ fears of recriminations against their sources, themselves, and/or employers arising not from defamation action as in the past, but from the threat of sanction under nascent fake news laws.

The article proceeds by reviewing key literature on the impact of fake news on journalism, legislative approaches to misinformation and disinformation, historic debates on media freedom and censorship, and a brief discussion of the media environments of Singapore and Indonesia. We then outline the method and key findings. We conclude with a warning about possible contagion effects for journalism practices in other countries if fake news laws become the norm and ways in which journalists in other jurisdictions might guard against "chilling effects".

Fake News and Media Freedom

At the outset, we concede “fake news” is a nebulous phrase often used as an umbrella term to refer broadly to both misinformation and disinformation (for a detailed examination of definitions see Tandoc et al. Citation2018). In this article, we define misinformation as the spread of inaccurate or misleading content that may (or may not) cause harm (Gibbons and Carson Citation2022). We define disinformation more narrowly as the spread of misleading, inaccurate or deceptive content using decisive actions with the aim of causing harm or deriving a benefit such as a financial windfall or political advantage (Gibbons and Carson Citation2022).

Fake news is not new but its rapid spread beyond geographical borders in the internet age offers new potency that can be corrosive to public trust of information and quality discourse. Fake news enables various harms but is particularly potent when it borrows from the “legitimacy of journalism” and citizens unwittingly share it across online platforms (Carson, Gibbons, and Phillips Citation2021, 19–20).

More recently, fake news has become a weaponised term used by politicians to discredit journalists and political opponents (Farhall et al. Citation2019). Popularised by former US President Donald Trump, the term has since been “appropriated by politicians around the world to describe news organizations whose coverage they find disagreeable” (Wardle and Derakhshan Citation2017, 3). Studies find labelling reporters and their stories as fake news can threaten journalistic norms and practices and have implications for trust relationships with sources and audiences (Panievsky Citation2021).

Given the harms that fake news can cause, it is unsurprising that mitigating the spread of misinformation and disinformation is a chief concern for governments across the globe. More than 17 countries have adopted laws and regulatory frameworks to tackle misinformation and disinformation (Meese and Hurcombe Citation2020). As noted above, Meese and Hurcombe (Citation2020) have identified three distinct government approaches and our study concerns the legislative response in the form of anti-fake news laws. Countries such as Germany, Russia, the UK, France, Singapore, Malaysia, Taiwan, and Brazil have adopted or indicated support for laws to tackle misinformation and disinformation in the media across digital and analogue platforms (Meese and Hurcombe Citation2020, 3-4). It typically involves bypassing “the consultative or voluntary approaches … and instead create new laws or, in the case of France, new judicial processes to regulate platforms” (Meese and Hurcombe Citation2020, 3). These laws provide power to governments to ban specific content, to label content as false, or deter the pursuit and publication of content by enforcing criminal penalties including fines and jail terms.

Countries with low levels of media freedom especially have been accused of using fake news laws to further restrict freedom of speech (Reporters without Borders Citation2021b; Neo Citation2021, 3). Research has shown that socioeconomic, political, and cultural factors – such as levels of media freedom and degrees of authoritarianism – shape how countries respond to misinformation and disinformation with those with lower levels of liberalism tending to favour this approach (Neo Citation2021).

Among the early adopters of fake news laws, Mchangama and Fiss (Citation2019, 17) identified that 10 out of 13 nations were classified as “not free” or “partially free.” Among them are our case countries, Indonesia and Singapore. Singapore’s POFMA law has been found to have mostly targeted opposition groups and journalists (Teo Citation2021b); while Indonesia’s ITE law has led to journalists and political opponents, who are accused of spreading fake news, facing jail time (up to 6 years) and large fines (Carson and Fallon Citation2021). Critics argue that these laws have been misused to suppress free speech, target political opponents, and undermine civil and political liberties (Mchangama and Fiss Citation2019; Teo Citation2021a).

Prominent examples of the effects of fake news laws in other settings include Russia since its invasion of Ukraine. In March 2022, Russia’s parliament amended its Criminal Code to make the spread of “fake” information an offence punishable with fines and jail terms of up to 15 years (Reuters Citation2022). As in other jurisdictions with similar laws the government determines what is considered to be “fake” news. Within a month of the law taking effect, 28 arrests were made targeting both journalists and their sources. These included investigative reporter Mikhail Afanasyev who was detained after he reported how Russian National Guard members embarrassed the Putin government by refusing to fight in Ukraine. Human rights activists and other journalists’ sources were also pursued by police under the amended law, among them a Mayoral aide detained after relaying information critical of the Russian government on a Telegram account (Roth Citation2022).

Media Censorship

Media censorship is not new (Tapsell Citation2012; MacKinnon Citation2011; Neo Citation2021). In times of crises such as war, censorship laws have been used by both democratic and non-democratic states to control political discourse, protect sensitive operations, and to limit, or spread propaganda. During World War I and II, major media organisations supported press censorship because it was deemed necessary to protect the state from existential threats (McCallum and Putnis Citation2008). This century, governments introducing fake news laws offer similar justifications for censoring online content.

In the digital era, fake news is often framed as a national security threat (McGonagle Citation2017; Teo Citation2021a; Neo Citation2021). As Neo observes, “fake news can be understood as an archetypal security issue – it is novel, socially salient, and has the potential to adversely impact not just upon social harmony but also foundational democratic institutions” (Citation2021, 2). As such, states claim fake news laws are necessary to protect citizens from the harmful effects of misinformation. For example, the Singaporean government argued that fake news laws were necessary for national security reasons (Benner Citation2019), along with other Southeast Asian governments invoking similar language (Ong and Chew Citation2019). In doing so such states legitimise their “right to censor content and revoke the licence of any media outlets for the purposes of maintaining peace and society cohesion” (Neo Citation2021, 12). In this way, fake news laws are legal tools that can consolidate power and help maintain control over information (Teo Citation2021a).

Fake news laws are considered a distinctive form of “information control” (Teo Citation2021a, 4809). They reinforce the perception that the government is the ultimate arbitrator of truthful and credible information thereby granting states greater perceived legitimacy and influence over political discourse (Teo Citation2021a, 4805–4807). Anyone subjected to prosecution under the law potentially has their credibility undermined when publicly accused of spreading falsehoods, and thus may become subject to “public vilification” by politicians and other actors including the media (Teo Citation2021a, 4801).

Structure of the News Media in Singapore and Indonesia

News media are integral to open societies by ensuring citizens have the necessary information to make informed political choices (McNair Citation2018). Providing access to information is crucial to maintaining a “democratic culture” and vibrant public sphere (McNair Citation2018). As noted above, Singapore and Indonesia are not considered fully free societies according to democratic indices and this is reflected in their media systems and structures.

Scholars have drawn attention to Singapore and Indonesia’s concentrated media ownership, and political ties between media owners and state actors (Mietzner Citation2020; George and Venkiteswaran Citation2019). In Indonesia, reforms of Indonesia’s media landscape in 1999 paved the way for a more liberal media with the relaxation of some press controls, leading to more media outlets (Setiawan and Tomsa Citation2022, 107–109). This century, about a dozen media conglomerates dominate the market share and most are linked to politicians and elites (George and Venkiteswaran Citation2019; Setiawan and Tomsa Citation2022, 107–109; Winarnita et al. Citation2022). For example, Indonesian billionaire Hary Tanoesoedibjo founded PT Global Mediacom Tbk which owns three national television channels with a combined audience share of 40 per cent. It also owns pay TV channels, newspapers, websites and radio stations (NikkeiAsia Citation2023). He founded the political party, Indonesian Unity Party, Perindo (Partai Persatuan Indonesia) (Mietzner Citation2020, 10). Similarly, Surya Paloh, founder of the National Democrat mass organisation that gave rise to the Nasdem Party and a former advisory board chairman of Indonesia’s Golkar Party, owns Media Group, a conglomerate company with large print, television and radio holdings.

Unlike Indonesia, Singapore has only two mainstream media organisations, both of which have close ties to the government, and a handful of alternative media sources (Wu Citation2021, p. 4–5). These mainstream outlets are Singapore Press Holdings (SPH) and Mediacorp. Singapore Press Holdings (SPH) is a publicly-listed corporation and is the dominant owner of, “local daily newspapers, including the flagship Straits Times” (George and Venkiteswaran Citation2019, 22). Mediacorp, a state-owned media company owned by Temasek – the holding company owned by the Government of Singapore – owns most television, radio, and digital media assets in the country (George and Venkiteswaran Citation2019, 22). With close government ties to its national media, the Singaporean press is often criticised for being largely a pro-government institution (George and Venkiteswaran Citation2019, 23).

An ongoing concern for critics is that Singaporean and Indonesian governments use coercive tactics to promote favourable pro-government coverage (Mietzner Citation2020; George and Venkiteswaran Citation2019). In Indonesia, the weaponisation of laws against media companies and their owners has been identified as instrumental to “the creation of a predominantly pro-government television landscape” (Mietzner Citation2020, 10). It is argued that legal cases against Indonesian media owners have been frozen or dropped in exchange for more friendly news coverage (Mietzner Citation2020, 10). Another obstacle to a free press is that Singaporean publishers are required to obtain licences from the government, with the information minister empowered to reject or revoke an application giving the government the power to silence political opponents (George and Venkiteswaran Citation2019, 23). It is argued this enables the Singaporean government to exercise significant control over commercial media and to reward trusted outlets that promote friendly content (George and Venkiteswaran Citation2019, 27).

Notwithstanding these restrictive practices operating within Singapore and Indonesia’s media environments, both countries have news organisations (e.g., Tempo; Project Multatuli, The Conversation, in Indonesia; Mothership, BBC, The Independent Singapore, Rice Media and New Naratif in Singapore) operating within their borders with missions to produce independent journalism akin to McNair’s normative perspective of the role of journalism in liberal democracies.

However, the enactment of POFMA (in Singapore) and the ITE (in Indonesia) offers new obstacles to press freedom. While these laws are ostensibly used to protect individuals from the harms of online misinformation, legal experts argue that “in practice, the Government and law enforcement officials have abused the law to silence political dissidents” (Hamid Citation2019, n.p.).

Singapore and Indonesia’s Fake News Laws

Fake news laws provide governments with broad surveillance powers. Although government officials may not have the capacity to monitor every online post or action, the prosecution of certain high-profile individuals can serve as a warning to others and create fear among internet users (MacKinnon Citation2011, 41). It is argued that the highly visible punishment of individuals is a form of coercion to encourage self-censorship among the broader populace and to silence critical opinions (Teo Citation2021a, 4798).

Singapore introduced the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA) in 2019 ostensibly to stop the viral spread of online misinformation and disinformation said to be threatening election integrity, social cohesion, and confidence in pubilc institutions. POFMA provides cabinet ministers with sweeping powers to force the removal of online content thus paving the way to prosecute persons or organisations for allegedly spreading falsehoods (Jayakumar, Ang, and Anwar Citation2021). Consequences for law breaches are considerable. The use of fake accounts or bots to spread fake news carries penalties of up to S$1m (approximately USD$733,700) and a jail term of up to 10 years (Wong Citation2019).

Another criticism of these laws is that they do not clearly define terms such as “misleading” or “falsehoods” leaving it open to interpretation by government officials (Wong Citation2019). In addition to POFMA, several existing laws and regulations were utilised to stop the spread of alleged misinformation, including the Defamation Act and Protection from Harassment Act 2014. However, POFMA has since become the primary legal instrument used by the Singaporean Government to tackle online misinformation, which often targets journalists (Carson and Fallon Citation2021). Data tracking of POFMA use from inception to May 2021 found media outlets and journalists were targets 50 times out of 165 cases, second only to civil society actors who received 51 POFMA orders (Teo Citation2021b).

Opposition political candidates have also raised concerns that the ruling political party is using the laws to suppress alternative political viewpoints, spread misinformation, manipulate public opinion, and maintain its hold on political power (see Carson and Fallon 2021, 21). For example, of the 18 POFMA orders issued during the 2020 general election campaign in Singapore, 12 orders targeted opposition political statements, including five orders against websites which had published statements made by Singaporean Democratic Party leaders (Carson and Fallon Citation2021, 20).

Indonesia has similar legislative powers to tackle online misinformation known locally as hoaxes (hoaks). In 2016, the Indonesian Government revised its Information and Electronic Transactions Law (ITE) that empowers government officials with the authority to target “any person who knowingly and without authority … manipulates, creates, alters, deletes, [or] tampers with electronic information” to make it “seem to be authentic” (UU ITE, Article 35). Breaches of the ITE law may result in severe penalties, including up to six years jail and fines up to Rp1billion (approximately $USD 69,500) (UU ITE, Article 27(3); Article 45(3))Footnote1. Similar to Singapore’s POFMA, the ITE does not define “misleading content” or “falsehoods” leaving it open to authorities’ interpretation. ITE has been used to jail journalists and editors for critical reportage of the authorities (IFJ Citation2021).

Civil society groups have taken issue with the vagueness of these nascent laws. The Southeast Asia Freedom of Expression Network (SAFEnet) argues that the ITE has so many interpretations that it creates legal uncertainty and opens opportunities for individuals to use the law against opponents (Lukman Citation2014). In Singapore, stakeholders have raised concerns about POFMA, questioning whether ministers should be given such wide-ranging powers to interpret the laws as they see fit (Jayakumar, Ang, and Anwar Citation2021). Media practitioners have argued that a journalist with a different interpretation of facts than the government is vulnerable to prosecution for reporting stories that challenge official accounts (Wong Citation2019).

A 2020 analysis of POFMA orders found that independent media, in particular, were targets of the law accounting for 33 out of 71 orders (Carson and Fallon 2021, 20). As such, civil society actors, activists, and academics criticised the Singaporean Government for using POFMA to undermine journalistic autonomy (Carson and Fallon Citation2021). Activists in Indonesia have made similar claims. SAFEnet observed that the ITE law was used 263 times from 2008 to 2018 primarily against members of the public, journalists and media. In 2017 and 2018, journalists were among the most targeted professionals (deidentified 2021, 8). Human rights groups and media professionals have argued that such laws curtail public debate, threaten freedom of expression, and give the government “unchecked power” over public discourse (Wong Citation2019). Academics fear the laws set an international precedent and could lead to “copycat legislation” (Academia SG Citation2019).

While Singapore and Indonesia’s fake news laws have been criticised in academic and popular discourse, the effect of these laws upon journalistic practices is not well understood. Critics argue the laws negatively impact media freedom (see Wong Citation2019; Teo Citation2021a; Tapsell Citation2019), yet few empirical studies have investigated such claims. With exceptions (see Teo Citation2021a), little is known about how journalists are responding to fake news laws and navigating this new legal-political environment to continue to produce (independent) journalism in the Asia-Pacific.

This paper aims to address this overarching question by examining how journalists are critically reporting news in a political environment where politicians design laws and label journalists as fake news. Through in-depth expert interviews, we address four sub-questions to understand how Singapore and Indonesia’s fake news laws impact journalism practices and are perceived to alter public discourse (if at all) in the case countries. The questions are:

Who do interviewees perceive are the primary targets of fake news laws?

What are the effects (if any) of the laws on journalism?

What do interviewees perceive are the consequences of fake news laws for political discourse?

Are journalists adapting to the laws to continue independent reporting? If so, how?

Method

We take a case-study approach using semi-structured interviews with journalism and fake news experts in Singapore and Indonesia. Interviewees were identified through an extensive literature review and snowball sampling methods.Footnote2 The purposive sample included journalists, editors, digital platform experts, academics, and civil society actors (see Online Supplementary material for interview schedule). Twenty interviews were undertaken between July 2020 and August 2022 using Zoom due to COVID-19 restrictions on travel. The majority of interviewees were journalists and editors, but also included their sources and fake news experts such as factcheckers and media academics in order to address all four research questions. The inclusion of experts beyond working journalists was deliberate as it was considered important to understand different perceptions of fake news laws on journalism and their sources from myriad expert perspectives.

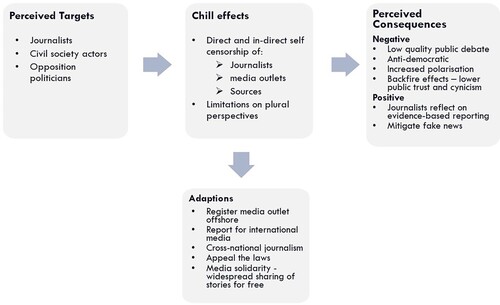

Interviews were evenly divided across Singapore and Indonesia (see Online supplementary material). Total interview time was 30 hours (averaging 1.5 hours per interviewee). Respondents were asked open-ended questions about the impacts of fake news and fake news laws upon journalism, their work and political discourse in their respective countries.Footnote3 To analyse the interviews, each was transcribed and coded using qualitative software, NVivo, to create topic “nodes” that revealed key themes in the data. We utilised inductive coding and grounded theory (see Corbin and Strauss Citation2014) until there was saturation of the key themes. The themes provided rich qualitative data of the interviewees’ first-hand experiences that addressed the research questions. In the next section, we detail the qualitative findings for both countries using the research questions as headings to order the findings. Findings are graphically summarised in .

Findings

Perceived Targets of Fake News Laws

Most respondents across the two countries (19 out of 20) felt that fake news laws had been used at some point to attack and discredit independent media, politicians, or civil society actors in their country.

Indonesia’s Metro TV News Director and Editor-in-Chief Arief Suditomo had a dissenting opinion from a majority view that was concerned about government overreach. As a former politician with the Hanura Party (Partai Hati Nurani Rakyat) and committee member that instigated the ITE law, Suditomo saw ITE as a necessary and positive development that has “drastically changed” the scale of threats to society inherent with the spread of fake news. “We use the ITE law for protection, not for putting some innocent people in jail. That’s not the spirit of ITE law,” he said (Arief Suditomo, Indonesia, July 18, 2022).

Suditomo said levels of education varied across Indonesia, and were generally lower than Singapore, and therefore the revised ITE was necessary in order to prevent the public naively spreading malicious fake news. He said organised groups disseminated disinformation for political purposes or financial gain and took advantage of “those who don’t know how to use social media wisely,” (Arief Suditomo, Indonesia, July 18, 2022). He said the main targets of the laws were those who intentionally or systematically spread falsehoods (Arief Suditomo, Indonesia, July 18, 2022). Citizens who inadvertently spread fake news were unlikely to go to jail, but instead dealt with at the local police station through an alternative system called “restorative justice” that focused on digital literacy, Suditomo said.

Other interviewees perceived the new laws less benignly and identified journalists and their sources as prominent targets of content removal orders under both the POFMA and ITE (i.e., Kirsten Han, Singapore, August 25, 2020; PJ Thum, Singapore, August 20, 2020; Andreas Harsono, Indonesia, August 20, 2020). Journalists were fearful of large fines and the threat of jail terms if their reporting was deemed misinformation under the laws in Indonesia (Andreas Harsono, Indonesia, August 20, 2020). In Singapore, PJ Thum, activist and managing director of independent news site New Naratif, said the threat of prosecution fostered a culture of fear among some journalists that could potentially lead to self-censorship:

The Government can simply ban us. They can block access to our site. And because I’m a Singaporean, they can come after me and haul me into court and charge me with whatever they want under the law … And then they can come after New Naratif for up to half a million dollars. So, these are the things hanging over our heads. (PJ Thum, Singapore, August 20, 2020)

A Singaporean freelance journalist observed that POFMA orders were more often directed towards social media and alternative media because mainstream media were less likely to challenge the status quo (Interview 13, Singapore, July 22, 2022). POFMA enabled the government to directly censor content by ordering it be removed from a news site, or to publicly label a story as false, to discredit the article. One interviewee explained why alternative media than mainstream journalists were more likely to be targets of POFMA:

POFMA is used to tackle stuff that the [Singapore Government] cannot control through the mainstream media, because in the mainstream media, they can call up the editor and ask, “Why are you running this?” You know, and they get a clarification published. It’s online where they cannot control the posts that go viral. So they really want to clamp down hard on it. (Interview 13, Singapore, July 22, 2022)

A range of actors were also targets of fake news laws in Singapore and Indonesia. The laws’ vague definitions enabled governments to target various groups, as one interviewee stated:

It [POFMA] contains a vague article that says something that could disrupt the harmony or stability in the community, it is illegal essentially. And so the Government has used that law to prosecute people for you know, all kinds of things that they post on social media. (Interview 1, Singapore, August 7, 2020)

Singaporean participants noted that the government was cautious and strategic in silencing political opponents (Interview 1, Singapore, August 7, 2020; Interview 15, Singapore, July 21, 2022; Interview 13, Singapore, July 22, 2022; PJ Thum, Singapore, August 20, 2020). Rather than targeting opposition politicians directly, governments sometimes targeted the messenger –journalists and social media outlets – who give a platform to opposition political candidates. An example was media that covered opposition politician Paul Tambyah, a doctor and professor of infection diseases, over his statements about the outbreak of COVID-19 in foreign worker dormitories in 2020. As PJ Thum explained:

[The People’s Action Party] were very careful about it … they did not hit the Singapore Democratic Party or Paul Tambyah himself with POFMA, even though he was the source of the statement. They hit the outlets which reported his statement, which means he had no standing to appeal. Only the media outlets could challenge it. And given the very short election period … by the time that (media outlets) appealed, the election was pretty much over. So I do feel that this did sway the results against Tambyah (PJ Thum, Singapore, August 20, 2020).

Effects on Journalism

The interviews reveal that using fake news laws to target journalists and their sources has had detrimental impacts on journalistic practices, making it difficult to publish some stories.

Some described the introduction of fake news laws as having a “chilling effect” on independent journalism (Interview 11, Singapore, August 20, 2020), others said it added to a pre-existing culture of “deference to the ruling government” (Interview 20, Singapore, August 29, 2022).

An Indonesian editor said she “worries” her newsroom will be targeted by ITE and that it would jeopardise their public credibility and formal media accreditation (Interview 17, Indonesia, July 19, 2022). Consequently, she did not publish stories unless fully verified. An Indonesian investigative editor explained how one of their stories, which was critical of police, was digitally stamped as a hoax by police and circulated on social media to discredit the story. In turn, a separate police source saw the label and “refused to talk to us … obstructing a journalist from doing their job” (Interview 14, Indonesia, July 20, 2022).

Respondents believe the laws were creating an environment whereby outlets were cautious about publishing stories that contradicted official government accounts without a strong evidentiary basis (PJ Thum, Singapore, August 20, 2020). In Singapore, fear of retribution could compel journalists and their sources to self-censor.

A lot of these laws create fear so that people end up self-censoring. So the Government can say that they didn’t do anything. They didn’t actually apply the law. (PJ Thum, Singapore, August 20, 2020)

Several Singaporean journalists (Interviews 13, 15, 19, 20) from small and large media organisations pointed out that a culture of self-censorship of journalists and of sources existed before POFMA was enacted due to existing laws such as the Broadcasting Act and (now repealed) Sedition Act. “POFMA is another law that is being used to do what the previous laws have been used for, to curtail and censor what was going on” (Interview 11, Singapore, August 20, 2020).

The introduction of POFMA was considered a “slippery slope” by some, which may lead to more draconian forms of censorship:

I think the fear now is this is a slippery slope kind of situation where POFMA will be used as a tool for politically motivated censorship. During the [2020] elections, there were instances where it bordered on politically motivated censorship. (Interview 11, Singapore, August 20, 2020)

In Indonesia, a culture of self-censorship was evident among online media users. Editor-in-chief of Tempo Magazine, Wahyu Dhyatmika, observed that the laws in Indonesia were (paradoxically) constraining freedom of expression online because people feared they would be targeted by government actors for the content they posted.

You can see it from chats, response or comments that we have for our content on social media. The commenters, the users will remind each other, careful with your comment. Don’t post anything that’s sensitive because who knows what will happen. (Wahyu Dhyatmika, Indonesia, August 24, 2020)

In sum, the perceived effects on journalism were that journalists and their sources were impacted by the fake news laws through direct censorship (stories taken down by authorities) and self-censorship (fear of retribution). Independent journalism in Indonesia and Singapore was considered particularly vulnerable to being discredited by authorities by having their stories labelled as fake news. We now turn to the question of what are the perceived consequences of these chilling effects on political discourse more generally?

Perceived Consequences of Fake News Laws on Public Discourse

Experts expressed views that the introduction of misinformation laws had stifled freedom of expression, undermined the public contest of ideas, and led to an overall decline in the quality of public debate (Interview 3, Singapore, August 18, 2020; PJ Thum, Singapore, August 20, 2020).

Laws such as POFMA encourage a blind obedience and dependence on the government, and that’s what the PAP government prefers. A critical populace, a critical citizenry, asked questions of the government, first and foremost … they [the ruling party] prefer to write laws which just give them vast sweeping amounts of power, and just tell people to just blindly listen. (PJ Thum, Singapore, August 20, 2020)

If you criticise certain or high official or somebody, they could report you to the director of crime in the police. Indonesia and democracy suffers from this restriction, particularly freedom of speech. According to a number of surveys, more and more Indonesian are afraid to express their criticism, express their opinion, publicly. (Professor Azyumardi Azra, Indonesia, July 22, 2022)

One Indonesian editor said he believed that journalists’ sources were scared to talk to the press for fear of being labelled as spreading fake news, which made it more difficult to publish some types of stories particularly about sex crimes. “Sexual abuse victims, they’re very, very afraid of ITE law. So they usually don’t want to speak to the press,” (Interview 14, Indonesia, July 20, 2022).

In Singapore, Cabinet ministers could declare information to be “false or misleading” and issue correction notices that force publishers, online platforms, or individuals to remove the content. PJ Thum said the lack of consistent definitions allowed governments to designate all sorts of statements as falsehoods, and by doing so, it silenced their critics.

It became very clear from almost the very first use of POFMA that it was about interpretations of statements, and that the Attorney- General’s chambers held the position that as long as any interpretation of a statement could be construed as false, the Government was entitled to use POFMA. (PJ Thum, Singapore, August 20, 2020)

If the government is the one that can say, what’s real and what’s fake, it’s really hard for, for me as a journalist or as an activist to, to kind of circumvent that. You know, particularly because in Singapore, we don’t have access to information either, there’s no Freedom of Information, right? So that the government holds pretty much all the cards in terms of data. So I can say something, and they go: “that’s not actually true, because, you know, our data shows this’, and then I can’t do anything.” (Kirsten Han, Singapore, August 25, 2020)

Kirsten Han also identified a backfire effect and argued that people were questioning the laws and politicians’ justifications for their existence.

It didn’t seem like POFMA orders were taken that seriously … it feels like people see POFMA not as a fact checking tool but as a political tool … It’s definitely not escaped notice that no PAP politicians have been POFMA’ed. It’s always opposition politicians, and its mainly independent news sites. (Kirsten Han, Singapore, August 25, 2020)

In contrast, it was also perceived that the laws could yield both intended and unintended positive outcomes. Among the intended positive impacts Arief Suditomo (Indonesia, July 18, 2022) said ITE had played a major role in limiting the spread of mis and disinformation in Indonesia. An unintended but positive consequence, suggested Han and one Indonesian editor (Interview 17, Indonesia, July 19, 2022), was that the fear of being “POFMA’ed” or subjected to ITE law forced journalists to produce more rigorously researched news stories. Han said “[POFMA] pushes you to find more evidence to support the story” (August 25, 2020).

The interview data suggests that fake news laws can limit free speech, journalistic freedom, and diversity of political voices in the public sphere. Positive assessments of the misinformation laws were rarer, with most interviewees prefacing it with the negative implications for public discourse in their respective countries. Nonetheless, there was recognition that the laws appeared to be effective at mitigating COVID-19 misinformation, suppressing hate speech, preventing harm, and promoting more collaboration between digital platforms and civil society groups (Interview 9, Indonesia, September 8, 2020; Interview 11, Singapore, August 20, 2020).

Despite numerous challenges created by fake news laws, journalists, editors, and their sources such as civil society groups show resilience, finding new ways to overcome the laws’ constraints so that diverse voices might be heard. In the next section, we identify five ways in which journalists and media outlets were adapting to resist the chilling effects of fake news laws, these include registering media companies offshore; reporting offshore; cross-national collaborations; appealing the laws, and widespread sharing of news stories.

Media Adaptations and Counteractions

Kirsten Han observed that the laws might be effective in silencing domestic critics, but POFMA were largely ineffective against foreign actors. As such, Han would look to write for international publications on sensitive government topics, such as Singapore’s death penalty, to ensure her reporting was “outside of government control” (Kirsten Han, Singapore, August 25, 2020).

Recognising the jurisdictional limitations of misinformation laws, some proprietors of independent news sites have moved their operations offshore.

We are registered in the UK, and we have a subsidiary organisation in Malaysia and we’re headquartered in Kuala Lumpur. (PJ Thum, Singapore, August 20, 2020)

We collaborate with several experts on this issue, we have a good network with [the] Medical Association. So they will be able to immediately respond to our request for clarification or for interviews for clarification. We also collaborate with the tech platforms … We have a fellowship for health experts that will be stationed in Tempo paid by Facebook, that will help us tackle this issue in a more timely fashion (Wahyu Dhyatmika, Indonesia, August 24, 2020).

Another tactic was to disseminate news stories as widely as possible to make it difficult to take them down or discredit them. An Indonesian editor said she overcame the authorities who had labelled an investigative story as fake by calling on media solidarity and sharing the story freely with other media to republish. “The power of the readers, and also the solidarity of other media, very effectively backfired against the powerful,” she said (Interview 17, Indonesia, July 19 2022).

provides a conceptual map of the targets, perceived journalistic impacts and perceived consequences of fake news laws in Singapore and Indonesia, and journalistic adaptations to the changed media environment.

Discussion and Conclusion

This article’s aim was to understand how Singapore and Indonesia’s legislative responses to misinformation and disinformation have impacted journalism practices, reporters’ relationships with sources, and perceptions of public discourse more broadly. We conclude that the overall impacts are similar in both countries, as is detailed below in answer to the four research questions, however there are some notable country differences. Indonesia has arguably a more acute fake news problem to address than Singapore due to its greater geographical and cultural diversity and overall media literacy levels. Singapore, compared to Indonesia, has far fewer media outlets and its fake news law tend to capture alternative media more so than mainstream organisations.

In answer to our first and second research questions about fake news laws’ perceived targets and its perceived effects, we find interviewees name journalists, independent media outlets, and news coverage of political opponents as perceived key targets of the laws. Interviewees identified that fake news laws enabled direct censorship of news reporting by ordering content to be taken down, or labelled as “fake” thus potentially discrediting the media outlet. This finding is consistent with other studies that have found that fake news laws disproportionally target journalists, civil society actors, political figures, and social media platforms (Teo Citation2021b).

More subtly, this study finds the laws can engender a culture of indirect self-censorship among journalists, news organisations, and their sources if they fear retribution by publishing content that challenges official government accounts. Notably, Singaporean mainstream media had a tolerance for avoiding highly sensitive political topics prior to POFMA’s enactment due to a lack of constitutional freedoms to enable sources to speak freely (Interview 20, Singapore, August 29, 2022). This perhaps reflects news reporting conventions in response to Singapore’s historic political culture.

Responding to our third question, experts perceived fake news laws were contributing to an overall decline in the quality of public discourse in the absence of adaptations to circumvent the laws’ effects. Also evident was an unintended backfire effect impacting political trust. By discrediting the media, respondents believed governments risked undermining public trust in news and paradoxically could make it more difficult to tackle harmful misinformation, which the laws were ostensibly designed to address. The decline in POFMA orders since the 2020 general election was suggested as one indication of government recognition of public dissatisfaction with its interference of free speech.

Concerning adaptations to the laws, we find that journalists were highly resourceful in identifying ways to circumvent legal obstacles and potential for reputational damage in both countries. These workarounds included registering media outlets offshore to be out of the laws’ reach and working with international journalists to minimise being targeted or labelled as fake news. However, Singapore recently passed the Foreign Interference (Countermeasures) Bill (FICA) in late 2021, a law that has the power to crackdown on this workaround measure by labelling offshore-based or funded media outlets as agents of “foreign interference.” While it is too early to understand its potential effects on Singapore’s journalism (as it has yet to be tested at the time of writing), the new law is identified here as an important subject for future study. Similarly, after shelving an unpopular draft law in 2019 that led to mass street protests, the Indonesia government has recently (Dec 2022) passed a revised version of its Criminal Code (RUU KUHP) containing provisions that have been widely criticised for further curtailing freedom of expression. The late Professor Azra argued it would have the power to criminalise journalistic work that would “further restrict the freedom of the press” (Indonesia, July 22, 2022). Again, this recent development is an imminent area for future research on this laws’ impact on journalism.

In sum, we find there is evidence of chilling effects on journalism and free speech in Indonesia and Singapore as a consequence of nascent fake news laws. But we also find that independent journalism is resilient, with reporters and their outlets finding new ways to adapt to this hostile media environment. This study contributes several important observations about the impacts of fake news laws in Indonesia and Singapore that may apply more broadly. The most obvious is that fake news is an entrenched global problem that can cause real-world harms, which extends beyond our studied countries. It is clear that governments need to respond and manage the spread of fake news, and that this spread seems to be a greater problem in Indonesia – a large society spread across a diverse archipelago with generally lower levels of media literacy – than the smaller, highly educated state of Singapore. Yet, it is also clear that democratic and non-democratic states have choices in how they respond. Other measures to tackle fake news include public education campaigns, fact-checking, collaboration with social media platforms, regulating platforms and so forth. Fake news laws are the latest approach to an age-old problem for state and non-state actors who may benefit from silencing the media. Previously, defamation laws were leveraged by governments to create a chill effect on journalism to restrain public debate (Marjoribanks and Kenyon Citation2003). Consistent with recent studies, we find fake news laws are perceived by most expert interviewees in Singapore and Indonesia to echo this tradition, providing a new legal weapon for governments to misuse to curtail free speech for political ends.

The case countries highlight how fake news laws are perceived as having the capacity to serve anti-democratic agendas by enabling governments to create a social and political environment with the potential to suppress opposition voices, including media speech, which can stifle public expression and debate. Exposing the democratic harms that arise intendedly and unintendedly from Singapore and Indonesia’s fake news laws is an important first step to caution more broadly against copycat laws in other countries and to prevent democratic backsliding, globally. For countries that have opted to introduce similar fake news laws, the case studies here reveal a number of ways media outlets and sources have demonstrated resilience to shelter from the laws’ adverse impacts on independent reporting, which may assist journalists and editors in other jurisdictions.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (19.4 KB)Acknowledgement

I would like to thank the special editors and the anonymous peer reviewers for their time and effort suggesting improvements to our work which has been of great benefit to us.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In early 2023 the Indonesia Government drafted amendments to the ITE Act, including to its penalties, to harmonise it with the newly revised Criminal Code (UU KUHP).

2 Most interviewees participated on the condition of anonymity and are randomly anonymised using numeric nomenclature as per La Trobe University's human ethics approval requirements. Some interviewees insisted on identification in order to have a public voice in the debates and are thus identified in the findings (see online supplementary material).

3 The semi-structured interview schedule is available from the authors by request.

4 Professor Azyumardi Azra sadly passed away on 18 September 2022.

References

- Academia, S. G. 2019. “POFMA: Letter to Education Minister.” Academics Against Misinformation, April 11. http://www.academia.sg/pofma-letter/.

- Benner, Tom. 2019. “Singapore Passes New Law to Police Fake News Despite Concerns.” Aljazeera, March 9. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/5/9/singapore-passes-new-law-to-police-fake-news-despite-concerns.

- Carson, Andrea, and Liam Fallon. 2021. Fighting Fake News: A Study of Online Misinformation Regulation in the Asia Pacific. Melbourne: La Trobe University.

- Carson, Andrea, Andrew Gibbons, and Justin Phillips. 2021. “Recursion Theory and the ‘Death Tax’.” Journal of Language and Politics 20 (5): 696–718. doi:10.1075/jlp.

- Corbin, Juliet, and Anslem Strauss. 2014. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/basics-of-qualitative-research/book235578.

- Farhall, Kate, Andrea Carson, Scott Wright, Andrew Gibbons, and William Lukamto. 2019. “Political Elites’ Use of Fake News Discourse Across Communications Platforms.” International Journal of Communication 13: 4353–4375. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/10677.

- Freedom House. 2021a. “Indonesia: Freedom in the World 2021 Country Report.” Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/country/indonesia/freedom-world/2021.

- Freedom House. 2021b. “Singapore: Freedom in the World 2021 Country Report.” Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/country/singapore/freedom-world/2021.

- George, Cherian, and Gayathry Venkiteswaran. 2019. Media and Power in Southeast Asia. 1st ed. Cambridge: University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108665643.

- Gibbons, Andrew, and Andrea Carson. 2022. “What is Misinformation and Disinformation? Understanding Multi-stakeholders’ Perspectives in the Asia Pacific.” Australian Journal of Political Science 57 (3): 231–47. doi:10.1080/10361146.2022.2122776.

- Hamid, Usman. 2019. “Indonesia’s Information Law Has Threatened Free Speech for More than a Decade. This Must Stop.” The Conversation, November 25. http://theconversation.com/indonesias-information-law-has-threatened-free-speech-for-more-than-a-decade-this-must-stop-127446.

- International Federation of Journalists (IFJ). 2021. “Indonesia: ITE Convictions Threaten Press Freedom.” International Federation of Journalists, December 3. https://www.ifj.org/media-centre/news/detail/category/press-releases/article/indonesia-ite-convictions-threaten-press-freedom.html.

- Jayakumar, Shashi, Benjamin Ang, and Nur Diyanah Anwar. 2021. “Fake News and Disinformation: Singapore Perspectives.” In Disinformation and Fake News, edited by Shashi Jayakumar, Benjamin Ang, and Nur Diyanah Anwar, 137–158. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Lukman, Enricko. 2014. “How Indonesia’s Problematic Internet Law Will Impede Freedom of Expression.” SAFEnet, September 10. https://safenet.or.id/2014/09/how-indonesias-problematic-internet-law-will-impede-freedom-of-expression/.

- MacKinnon, Rebecca. 2011. “Liberation Technology: China’s ‘Networked Authoritarianism’.” Journal of Democracy 22 (2): 32–46. doi:10.1353/jod.2011.0033.

- Marjoribanks, Tim, and Andrew T. Kenyon. 2003. “Negotiating News: Journalistic Practice and Defamation Law in Australia and the US.” The University of Melbourne Faculty of Law Legal Studies Research Paper 67: 1–23.

- McCallum, Kerry, and Peter Putnis. 2008. “Media Management in Wartime: The Impact of Censorship on Press–Government Relations in World War I Australia.” Media History 14 (1): 17–34. doi:10.1080/13688800701880390.

- McGonagle, Tarlach. 2017. “‘Fake News’: False Fears or Real Concerns?” Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights 35 (4): 203–209. doi:10.1177/0924051917738685.

- Mchangama, Jacob, and Joelle Fiss. 2019. “The Digital Berlin Wall: How Germany (accidentally) Created a Prototype for Global Online Censorship.” Justitia, https://futurefreespeech.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/analyse-the-digital-berlin-wall-how-germany-accidentally-created-a-prototype-for-global-online-censorship.pdf.

- McNair, Brian. 2018. An Introduction to Political Communication. 6th edn. London: Routledge.

- Meese, James, and Edward Hurcombe. 2020. Regulating Misinformation: Policy Brief. Melbourne: RMIT University. https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2020-11/apo-nid309357.pdf.

- Mietzner, Marcus. 2020. “Authoritarian Innovations in Indonesia: Electoral Narrowing, Identity Politics and Executive Illiberalism.” Democratization 27 (6): 1021–1036. doi:10.1080/13510347.2019.1704266.

- Neo, Ric. 2021. “When Would a State Crack Down on Fake News? Explaining Variation in the Governance of Fake News in Asia-Pacific.” Political Studies Review, 1–20. doi:10.1177/14789299211013984.

- Nikkei Asia. 2023. PT Global Mediacom Tbk. https://asia.nikkei.com/Companies/PT-Global-Mediacom-Tbk.

- Ong, Elvin, and Isabel Chew. 2019. “‘Fake News’, the Law and Self-Censorship in Southeast Asia.” East Asia Forum, August 2. https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2019/08/02/fake-news-the-law-and-self-censorship-in-southeast-asia/.

- Panievsky, Ayala. 2021. “Covering Populist Media Criticism: When Journalists’ Professional Norms Turn Against Them.” International Journal of Communication 15: 2136–2155. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/15299.

- Reporters without Borders. 2021a. “Indonesia : Press Freedom Still Pending in Jokowi’s Second Term.” Reporters without Borders. 2021. https://rsf.org/en/indonesia.

- Reporters without Borders. 2021b. “Singapore: An Alternative Way to Curtail Press Freedom.” Reporters without Borders. 2021. https://rsf.org/en/singapore.

- Reuters. 2022. “Russia Fights Back in Information War with Jail Warning.” Reuters, March 4, 2022, sec. Europe. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russia-introduce-jail-terms-spreading-fake-information-about-army-2022-03-04/.

- Roth, Andrew. 2022. “‘I’m Waiting to Be Arrested’: Russian ‘Fake News’ Law Targets Journalists.” The Guardian, April 21, 2022, sec. World news. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/apr/21/im-waiting-to-be-arrested-russian-fake-news-law-targets-journalists.

- Setiawan, Ken M.P., and Dirk Tomsa. 2022. Politics in Contemporary Indonesia: Institutional Change, Policy Challenges and Democratic Decline. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780429459511.

- Shepherd, Katie. 2020. “A Man Thought Aquarium Cleaner with the Same Name as the Anti-Viral Drug Chloroquine Would Prevent Coronavirus. It Killed Him.” Washington Post, March 24. https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/03/24/coronavirus-chloroquine-poisoning-death/.

- Tandoc, Edson C., Zheng Wei Lim, and Richard Ling. 2018. “Defining ‘Fake News’.” Digital Journalism 6 (2): 137–153. doi:10.1080/21670811.2017.1360143.

- Tapsell, Ross. 2012. “Old Tricks in a New Era: Self-Censorship in Indonesian Journalism.” Asian Studies Review 36 (2): 227–245. doi:10.1080/10357823.2012.685926.

- Tapsell, Ross. 2019. “Indonesia’s Policing of Hoax News Increasingly Politicised.” ISEAS 75: 1–10. https://www.iseas.edu.sg/images/pdf/ISEAS_Perspective_2019_75.pdf.

- Teo, Kai Xiang. 2021a. “Civil Society Responses to Singapore’s Online ‘Fake News’ Law.” International Journal of Communication 15: 4795–4815. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/17910/3593.

- Teo, Kai Xiang. 2021b. “About.” POFMA’ed. November 9. http://pofmaed.com/.

- UU ITE. [Law No. 11 of 2008 on Information and Electronic Transactions (Indonesia) [revised 2016]]. HUKUM Online. https://www.hukumonline.com/pusatdata/detail/lt584a7363785c8/node/lt56b97e5c627c5/uu-no-19-tahun-2016-perubahan-atas-undang-undang-nomor-11-tahun-2008- tentang-informasi-dan-transaksi-elektronik.

- Wardle, Claire, and Hossein Derakhshan. 2017. “Information Disorder: Toward an Interdisciplinary Framework for Research and Policymaking.” The Council of Europe. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/PREMS-162317-GBR-2018-Report-de%CC%81sinformation.pdf.

- Winarnita, Monika, Nasya Bahfen, Adriana Rahajeng Mintarsih, Gavin Height, and Joanne Byrne. 2022. “Gendered Digital Citizenship: How Indonesian Female Journalists Participate in Gender Activism.” Journalism Practice 16 (4): 621–636. doi:10.1080/17512786.2020.1808856.

- Wong, Tessa. 2019. “Singapore Fake News Law Polices Chats and Online Platforms.” BBC News, May 9. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-48196985.

- World Health Organisation. 2021. “Infodemic.”. https://www.who.int/westernpacific/health-topics/infodemic.

- Wu, Shangyuan. 2021. “As Mainstream and Alternative Media Converge?: Critical Perspectives from Asia on Online Media Development.” Journalism Practice 0 (0): 1–17. doi:10.1080/17512786.2021.1976072.