ABSTRACT

This paper explores the proximity of local media to audiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is based on a case study of Italian daily L’Eco di Bergamo combining two sets of data: a list of initiatives the newspaper took in 2019 and 2020 to be closer to audiences, and interviews shedding light on how staff viewed the paper’s relationship with audiences during that time. An analysis of these two datasets shows that the pandemic increased the newspaper’s proximity to audiences but did not fundamentally change the way in which it related with audiences, despite significant changes in journalists’ work routines. Based on these findings, the paper proposes a conceptualization of proximity as a dynamic balance between three structuring dimensions (gatekeeping, social and commercial), with a focus on audiences as a plural figure determined by news organizations’ strategies.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a time of upheaval for local journalism. On the one hand, it has disrupted journalists’ work routines and weakened news organizations that were already struggling financially amidst an unfinished digital transformation. On the other, it created a high demand for fast, reliable news about the spread of the virus and the public health measures undertaken in each area and sparked increased trust in news media (Newman et al. Citation2021). Since news organizations are expected to be available to help in times of crisis (McQuail Citation2013), it seemed that the pandemic would be a time when news media would strengthen or reconfigure their relationship with audiences in order to meet audiences’ information needs, accommodate their own market imperatives, and help strengthen the community.

This paper uses a case study of Italian local daily L’Eco di Bergamo (L’Eco) to explore local media’s proximity to audiences during the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic and the impact of this situation on audience proximity. It does so by listing and comparing the initiatives the newspaper took to create a connection with audiences in 2019 and 2020 and by analyzing semi-structured interviews with its staff that provide insight into how employees assigned meaning to these initiatives and experienced the paper’s relationship with audiences. L’Eco is a pertinent case study for this issue because it has a long history, has been dominant in its market, and is located in Bergamo, a region that became the epicenter of the pandemic in Europe in 2020 (Bernucci, Brembilla, and Veiceschi Citation2020). Indeed, L’Eco’s 11-page-long obituary section and images of coffins being ferried to neighboring provinces for cremation when local hospitals and funeral homes were overwhelmed provided a shocking testament to the local crisis.

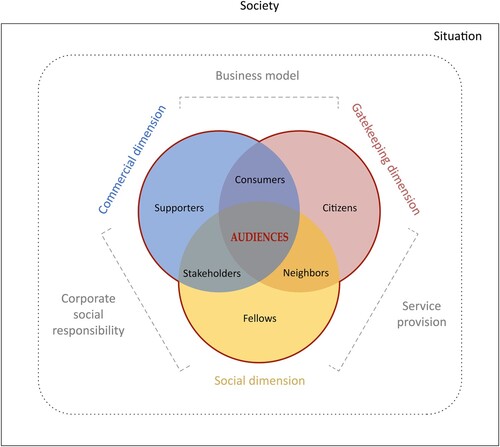

Based on these results, I suggest that proximity to audiences can be understood as a dynamic balance between three structuring dimensions brought together in a central core: the plural figure of audiences. The gatekeeping dimension refers to the editorial philosophy determining what type of content the newspaper will publish and defining the news-making process. The commercial dimension refers to the strategy that sustains a news organization in its market. The social dimension refers to actions to create a sense of mutuality with and between audiences by fostering social interaction and/or solidarity. News organizations’ proximity to audiences is shaped by the interplay of these dimensions, which is in turn reflected in the nuanced and plural roles audiences are expected to play in relating to a news organization.

This paper is intended to contribute to conceptualizations of shared notions in local journalism (Gulyas and Baines Citation2020) while adding to the comparatively small number of empirical studies on local media in southern Europe as opposed to in Nordic or English-speaking countries (Guimerà, Domingo, and Williams Citation2018). The large body of literature on phenomena associated with proximity affirms both the plasticity of this concept and its centrality in journalism. Few studies, however, consider these factors together whilst studying them through the prism of local media. By focusing on local media and assigning only three dimensions to proximity, my conceptualization helps reduce the ambiguity of this notion, thus allowing for more comparability between studies.

Proximity to Audiences as a Three-dimensional Concept

Proximity has been associated with a broad spectrum of phenomena, ranging from objective factors to subjective feelings of connection to normative values. Despite this variety, however, most studies define proximity in terms of dynamics that reduce distance in various ways (e.g., with regard to geographic location, cultural traits, or feelings of connection). That definition is also the starting point of this study. In examining local media’s relationship to audiences, I align with the idea of proximity as “an impression produced by actors successfully conducting strategies to get closer” (Le Bart and Lefebvre Citation2005, 15). In line with this, Ahva and Pantti (Citation2014) have mapped proximity in digital media as a broad organizational strategy that aims to connect news organizations with audiences as citizens or customers. My conceptualization builds on these scholars’ research. It includes some of the factors in Ahva and Pantti’s model but considers them in terms of local media’s intention in relating to audiences. A non-exhaustive selection of theoretical and empirical studies making use of the concept of proximity are presented below according to the dimension they inform (i.e., gatekeeping, social or commercial) in my conceptualization of proximity.

Gatekeeping Dimension

This dimension refers to the editorial strategy setting out what type of content will be published and the organization’s approach to news-making. It concerns the production, coverage and presentation of information in ways that connect with audiences. It recalls the traditional role of journalists as gatekeepers engaged in “the process of selecting, writing, editing, positioning, scheduling, repeating and otherwise massaging information to become news” (Shoemaker, Vos, and Reese Citation2009, 73).

In general, local media seek to provide relevant information to their audiences in order to be closer to them. This involves publishing stories that allow citizens to make decisions on matters of politics or public interest, which is considered a defining role of local media. It is associated with the idea of journalism as a fourth estate, where journalists hold power to account (Hanitzsch and Vos Citation2018). It also involves providing non-political information on topics in everyday life relating to consumption, emotion and identity (Hanitzsch and Vos Citation2018). Similarly, Bousquet (Citation2015) showed that French regional newspapers have historically been providers of “news as service” (i.e., non-editorialized news), which helps organize everyday life in the newspaper’s area of diffusion while creating connections with and between local citizens.

The notion of proximity also comes into play when selecting news for its relevance to audiences. As news selection criterion, proximity has been associated with objective (e.g., time distance) or subjective (e.g., cultural similarity) factors (Galtung and Ruge Citation1965). Furthermore, Shoemaker et al. (Citation2007) define news value in terms of geographical distance (i.e., “proximity”) and journalists’ assessment of an event’s psychological closeness to audiences (i.e., “scope”). Hess (Citation2013) uses these notions of proximity and scope to develop her concept of geo-social news. She explains that local newspapers cover stories that are physically close to their area of publication and act as mediators by interpreting national or global stories through a local lens, thus enhancing their relevance for their audiences.

Proximity also refers to the way local journalists manage distance from their sources (Franklin and Carlson Citation2011), particularly local administrative, political, social and economic institutions, which are typically a journalist’s main sources in producing local news (Ballarini Citation2008). In relying primarily on these sources, local journalists have been described as “passive recipients” of information rather than investigators, which undermines their role as gatekeepers (O’Neill and O’Connor Citation2008). Moreover, if a local news organization maintains a close relationship with the political authorities they are expected to hold to account, this brings their watchdog role into question (Le Bohec Citation1998).

In addition, proximity to audiences can be created through the discursive mechanisms used to present news (e.g., story angles). The combination of journalistic genres and writing techniques with topics related to the editorial line (described as “editorial proximity”) allows journalists to present their selected information a way that fosters closeness with audiences (Ringoot and Rochard Citation2005).

Developing ways to include audiences in the news-making process is another means of strengthening audience proximity. This strategy goes by a number of names. For example, participatory journalism refers to audience participation in the construction of news (Paulussen et al. Citation2007), while engaged journalism (Wenzel and Nelson Citation2020) aim to create collaborative relations with citizens by bringing them into the news-production process.

Social Dimension

This dimension of proximity pertains to the self-assigned role of news media in constructing a feeling of mutuality through strategies to promote social interaction and solidarity. It entails local media creating social bonds with and between locals based on living alongside one another, as well as strengthening community cohesion and well-being. This is done geographically and relationally, in both physical and virtual spaces. It involves news media being present in their region of distribution through heightened visibility or accessibility. This aligns with the “proximity principle” in social psychology, which suggests that people tend to form relationships with people nearby in a physical space rather than with those further away (e.g., Marmaros and Sacerdote Citation2006). Furthermore, it means not only being present, but taking action by creating specific opportunities for discussion and/or mutual help outside the scope of the editorial and commercial interests.

Creating social bonds and developing opportunities for social interaction are considered distinctive features of local media (Gulyas and Baines Citation2020), which have the ability to turn a space into a place (Hess and Waller Citation2017). One of the historical characteristics of local media is their geographical ties with their audiences: local journalists identify with their region and share their audience’s lives even as they report on them (Bousquet Citation2018). Research has shown that news outlets’ presence in the areas they cover contributes to a feeling of collectivity (Arnold and Blackman Citation2021). Mostly in-person but also technologically mediated initiatives organized by local news media also nurture social bonds with audiences by creating opportunities to socialize with and/or help fellow locals, for example through festive events or charity fundraisers (Pignard-Cheynel and Amigo Citation2022). Additionally, because solidarity leads to mutual support and cooperation to solve social problems, it is likely that there will be a stronger demand for solidarity when a crisis arises (Lindenberg 1998 as cited in Wallaschek, Starke, and Brüning Citation2008), and thus that local media will develop more strategies to respond to this demand.

Commercial Dimension

The commercial dimension refers to strategies to sustain a news organization from a market perspective. These strategies translate into different revenue streams in which audiences play a part, such as sales, memberships and audience insight monetization. Marketing plays a key role here, as it aims to promote and provide services and products to consumers and third parties (e.g., advertisers) to increase brand awareness and organizational growth (Geana Citation2009). This dimension is grounded in the idea that news organizations are first and foremost commercial ventures. Matthews (Citation2015) historical study shows local newspapers are essentially commercial propositions relating to audiences in a market-driven perspective, and this is what defines their other characteristics.

Although in some places news media continue to be sustained by the traditional combination of revenue streams from readers and advertisers (Reader and Hatcher Citation2020), transformations in the media landscape and information practices have pushed news organizations to innovate in order to accommodate changing market demands. Research has showed that local media are exploring new revenue streams, from putting up paywalls to using analytics to personalize content (Jenkins and Nielsen Citation2020). This implies that these media are rethinking the roles audiences are expected to play in financially supporting them. Furthermore, even if newsrooms followed marketing principles before the digital era (Hubé Citation2010), marketing today plays a larger role in news organizations’ efforts to cope with the industry’s economic downturn (Sommer Citation2018). News media increasingly rely on user analytics to understand their readers’ preferences and consumption patterns, which are used to make editorial decisions (Nelson Citation2021). Indeed, the development of audience-monitoring activities led to the emergence of specific roles within newsrooms such as the audience-oriented editor (Ferrer-Conill and Tandoc Citation2018). Moreover, scholars have claimed that in light of the current economic challenges, organizations would benefit from strategies based on nurturing relationships with consumers, and from the continual product and service improvement that derives from these strategies (Villi and Picard Citation2019). This would entail developing relationships that “evoke emotions, senses of belonging, involvement and perhaps also a sense of ‘ownership’ of the media brand” (Villi and Picard Citation2019, 126).

Although the three dimensions of proximity have been presented separately for analytical purposes, they are not mutually exclusive. Instead, they create interplays reflecting alignments and tensions specific to each dimension’s paradigm. For example, the intersection of the gatekeeping and the commercial dimensions gives rise to tensions that manifest in journalists’ resistance to adopting marketing logic in the news-making process (Tandoc and Vos Citation2016). While both dimensions seek to engage audiences by providing them with content suited to them, the tension stems from the different choice of criteria guiding this effort: journalistic considerations center around producing news that empowers citizens, while marketing logic centers around feeding audiences content they prefer so as to gain their attention and generate revenue. Neither position can afford to ignore the other.

Contextuality

While the three dimensions of proximity are present in all local media, creating proximity to audiences is always a situated process. The balance of the dimensions is best understood as a negotiated order (Strauss Citation1992) resulting from the interactions of staff who represent a dimension through their professional role (e.g., journalist, marketing manager, director), both within the organization and in the larger context in which it operates. Proximity to audiences is tied to a complex combination of factors related to the news organization (e.g., media type, history or work practices), which is itself part of a media system located in a society with specific political, social, cultural, economic, and technological configurations that cannot be manipulated. Therefore, both the balance of the dimensions and the way this materializes through strategies carried out by news organizations may vary from case to case. Conversely, organizational proximity—which refers to the level of similarity in norms and routines between organizations steeped in cultural and institutional frameworks at the national or regional levels (Knoben and Oerlemans Citation2006)—may result in similar audience proximity strategies across different news media.

The balance between the dimensions is also dynamic, for several reasons. First, in the long(er) term, broad societal transformations reconfigure the way news media relate with audiences. Journalism history research has shown that journalism has varied in the ways it has engaged with politics, technology, economics and culture in different historical periods (Conboy Citation2004). Second, less structural changes at the national level (e.g., new public policies) or the news organization level (e.g., a new business model) may affect the balance of the dimensions. Third, certain types of events (e.g., natural disasters) may lead organizations to develop strategies shaped primarily by a specific dimension of proximity to address the impact of the events on the local context. The literature has described these situations as “key events” (Brosius and Eps Citation1995), since they break the stability of daily life, are intensively covered by journalists and influence news selection criteria. More long-term changes may result from “critical incidents”, defined as pivotal moments that cause journalists to reconsider important aspects of their professional practice (Zelizer, Citation1992). Examples of critical incidents have included drug wars, terrorist attacks, and the COVID-19 pandemic (Tandoc et al. Citation2021).

Considering proximity to audiences as a three-dimensional concept expressed through a news organization’s strategies to relate with audiences, and knowing that the process of creating proximity can be affected by situations that arise and may impact the local context, I posed the following research questions:

RQ1. What concrete initiatives did L’Eco undertake to foster a close relationship with audiences in 2020 (i.e., the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic) in terms of the three dimensions of proximity?

RQ2. How did L’Eco’s staff view these actions and their relationship with audiences during that time?

RQ3. How did the pandemic affect L’Eco’s proximity to audiences with regard to the three dimensions of proximity?

L’Eco di Bergamo During the Pandemic

Founded in 1880 (and still owned) by the Curia of Bergamo, L’Eco is one of the oldest local newspapers in Italy. It employs 66 people, including 51 journalists. Each edition includes local, national and international news, lengthy crime news and obituary sections, and sports, culture, classifieds and “life events” sections. It has historically combined coverage of relevant local issues with the provision of material help to address them (e.g., through fundraising); this commitment to regional issues is a testament to the newspaper’s Christian roots (Amigo Citation2022). The reconfiguration of the Italian media landscape over the last twenty years, largely due to the growth of digital media, has weakened the position of local news organizations (Splendore Citation2017), and L’Eco is no exception: its readership has been steadily shrinking over the last two decades (ADS Citation1979–2021). To remain afloat, Italian local outlets have sought to redefine their relationship with audiences in an approach oscillating between tradition and experimentation (Murru and Pasquali Citation2020).

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in Bergamo city and province in 2020 was dramatic. Bergamo was one of the most affected areas in Europe: its death toll was 260% higher in 2020 than in 2019, with most deaths occurring in the first half of 2020 (Nicotra Citation2021). In February, the rapid spread of the virus led the government to introduce restrictions (on movement, gathering, etc.). This was followed by two main phases: a “lockdown phase” (from mid-March to May) characterized by a severe general disruption; and a “post-lockdown and pre-vaccine phase” (from May to end of December) characterized by prolonged disruption and dilemmas of adjustment (Garavaglia, Sancino, and Trivellato Citation2020).

In crises such as these, local media play a key role in informing citizens, contributing to their safety and building community resilience (e.g., Hess and Waller Citation2021). They are important vectors of reliable, timely, local information while helping preserve the social order. In Italy in 2020, this was reflected in the increased consumption of local news (Castriota, Delmastro, and Tonin Citation2020), which helped people keep up with developments in the pandemic, particularly in light of the proliferation of misinformation. It could also be seen in the general increase in trust in news media, which in Italy reversed the downward trend of previous years (Cornia Citation2021). Local media also played a significant role in the pandemic response by communicating public health information in clear ways and by encouraging locals to follow heath guidelines (Mheidly and Fares Citation2020). To do this, many European news media modified their paywalls so that everyone could freely access pandemic news (Charon Citation2020). Besides “saving lives” through providing information, local media also acted as a “cheerleader of their community” (Wahl-Jorgensen, Garcia-Blanco, and Boelle Citation2021). Many European local news organizations developed initiatives to foster informal exchanges and mutual aid networks (Quinton Citation2020).

Crises like COVID-19 also pose challenges to journalists’ work routines. The pandemic forced journalists to telework and adapt their organizational processes to comply with public health restrictions such as social distancing requirements (García-Avilés Citation2021). Moreover, journalists who may have had little experience in dealing with distressing stories of death suddenly found themselves covering a traumatic situation (Jukes, Fowler-Watt, and Rees Citation2021) while being exposed to the virus themselves.

In addition, the pandemic affected journalists’ relationship with their information sources. Beyond the obvious difficulty in obtaining in-person interviews, journalists’ relationship with the authorities was sometimes regarded as problematic. Research has shown that reporting collaboratively with medical experts during the pandemic was both valued and considered a risk factor (Perreault and Perreault Citation2021). In certain cases, the pandemic led to the establishment of political control over the news and journalistic work, curtailing news organizations’ autonomy and democratic role (Casero-Ripollés Citation2021).

Lastly, journalists were in a vulnerable position because the pandemic hurt the overall economic health of their organizations (Newman et al. Citation2021). In Italy, local media dealt with a sharp drop in advertising and overall decline in revenues (AGCOM Citation2020). Local media in general sought to combine revenue streams (Pavlik Citation2021) to ensure their sustainability.

Method

The starting point for this study was a database of 163 ongoing or new initiatives carried out by L’Eco in 2020 and 2019 to create or strengthen its connection with audiences. Initiatives are actions that invite audiences to participate in an activity with a main purpose (to fuel news production, foster sociability, generate sales, etc.) taking place in a physical and/or digital space (Pignard-Cheynel and Amigo Citation2022). They are one aspect of broader strategies to create proximity to audiences that are formally or informally transmitted within news organizations (e.g., through business models or the editorial line). Initiatives are publicized on news organizations’ websites, broadcasts, social media accounts, etc., usually with a brief description. To identify the initiatives, I read all the editions published by L’Eco in 2020 and 2019 and closely checked the content posted on its social media accounts during that period. Based on their publicized descriptions, the initiatives were coded into different types based on their main characteristics (Pignard-Cheynel and Amigo Citation2022). Later, each initiative was coded again based on the main dimension (i.e., gatekeeping, social or commercial) informing the audience relationship.

The initiatives examined in this study were extracted from a larger inventory of 490 initiatives undertaken by L’Eco since 1880, since this paper is part of a larger research project studying L’Eco’s proximity to audiences since its founding. In the findings section, initiatives are identified as “I-n”, where “n” refers to the corresponding database entry number; each entry includes a short description of the initiative and its start and end year(s). The raw database is available here. ()

Table 1. Criteria for categorizing initiatives according to their main dimension.

The database helped me to gain an overview of the initiatives carried out by L’Eco to connect with audiences during the outbreak of the pandemic and to identify variations in the number, type and dimension of initiatives between 2019 and 2020 from quantitative perspective. Each initiative was counted as one entry regardless of its duration or the resources needed to carry it out. Consequently, the most rudimentary initiatives are listed alongside the most highly developed, and the shortest-lived alongside the longest-term. Also, although the database used for this paper is intended to be as complete and systematic as possible, I cannot claim that it is exhaustive.

In addition, 10 semi-structured interviews with an average length of 56 min were conducted face-to-face with L’Eco staff in July 2021. Considering that the relationship with audiences is fostered by people from different professions, the sampling design aimed to obtain the widest possible diversity of respondent profiles (not a representative sample of L’Eco professionals). To recruit respondents, I reached managers, editors, journalists, etc. identified online and through the initiative inventory and asked for their cooperation and help to locate others. Respondents, who were guaranteed anonymity, were four journalists, two editors-in chief, the newspaper’s director and general secretary (identified as “directors”), and a sales and a marketing manager (identified as “managers”). Following an interview guide, respondents were asked about their understanding of proximity to audiences, their views on L’Eco’s relationship with audiences before and after the outbreak of the pandemic, and the specific initiatives listed (e.g., who was involved in the initiatives, why they were carried out, how the pandemic affected ongoing and new initiatives). A qualitative content analysis approach was used to identify the semantic universe and underlying meanings through data coding (Bardin Citation1977). This resulted in a back and forth process between data and interpretative categories. Indeed, the verbatim transcripts were coded according to categories related to the interview questions; simultaneously, new (sub)categories were developed inductively, based on the information collected. Responses were considered as declarative material revealing how interviewees represented themselves, the newspaper and their experience both within L’Eco and the broader context in which the newspaper operates. L’Eco’s initiatives were also linked to all these categories, which allowed to identify areas of (in)congruence between initiatives and sayings. The newspaper’s proximity to audiences was then understood as intertwined forms of actions and discourses (on them).

Findings

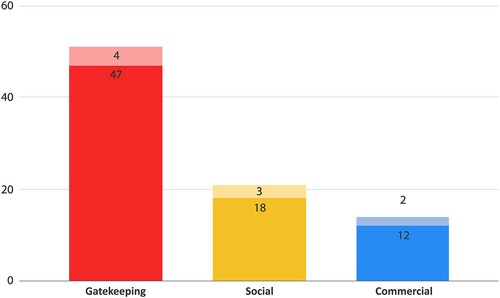

“Covid has brought us closer”

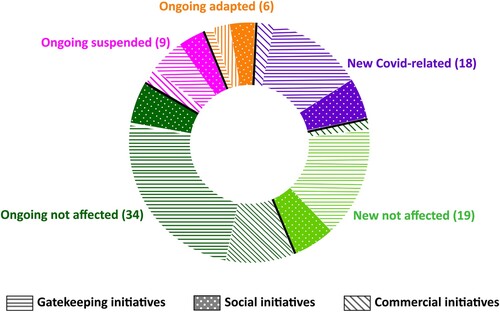

In 2020, L’Eco carried out 86 initiatives, the majority of which were gatekeeping initiatives, followed by social and commercial initiatives (see below). Of that total, 49 had already been carried out in 2019.Footnote1 These ongoing initiatives mainly consisted of an invitation to submit material (e.g., questions, images, messages) that was sometimes published. Most had been held annually for a number of years, such as the “Tell us a story” initiative inviting audiences every summer since 2015 to submit stories on local volunteers to feature in a dedicated section [I-276]. Nearly 70% of these ongoing initiatives were not affected by the outbreak of the pandemic. One explanation is that these initiatives are embedded in the newspaper’s processes and require few resources to set up (since the audience relationship is technologically mediated rather than based on in-person encounters). Additionally, the collected submissions generated material to fuel news production, which was especially useful when disrupted work routines and canceled social and commercial activities made it more difficult to produce content.

Figure 1. Distribution of 2020 initiatives by main dimension. Initiatives suspended due to COVID-19 appear in lighter color. Source: Author.

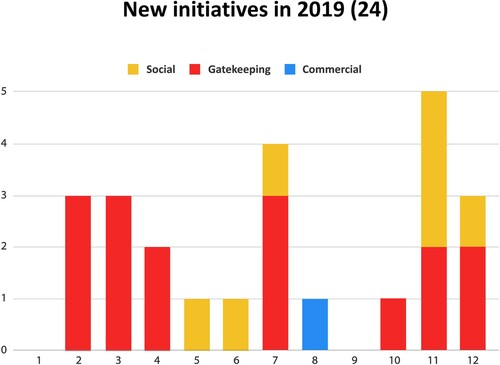

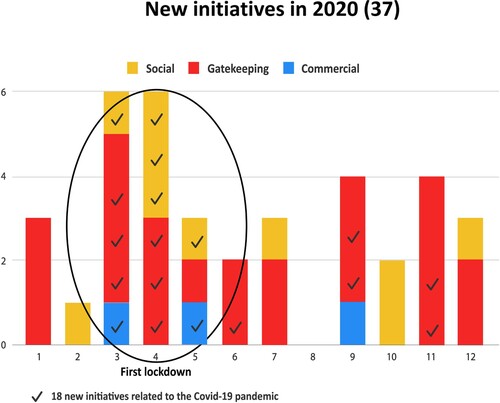

Of the 37 initiatives introduced for the first time in 2020, 19 were unrelated to the pandemic. Most were carried out either before or after the first lockdown. In the latter case, the impact of the pandemic was hardly visible, as the initiatives had already been planned taking restrictive measures into account and were similar to previous initiatives (e.g., a request to submit children’s letters to Saint Lucy [I-474], who is said to bring presents in December).

However, COVID-19 directives restricting social and commercial activities forced the newspaper to suspend nine initiatives relating to all three dimensions of proximity. This included, for example, “Bergamondo” [I-133], an annual soccer tournament that aims to help immigrants integrate into the local community by bringing together players from different nationalities living in the city; the L’Eco subscribers club [I-235], which offers commercial benefits to members; and an annual invitation to submit photos of the local carnival [I-147]. The pandemic also led L’Eco to adapt six initiatives, mostly by transforming in-person encounters into digital ones (e.g., holding via Zoom an annual debate on journalism [I-17]).

The pandemic’s impact on the newspaper’s proximity to audiences can also be observed by comparing initiatives launched in 2020, shown in purple and light green in , with those launched in 2019 (see and below). The 65% growth in new initiatives in 2020 shows that the pandemic led the newspaper to try to increase its proximity to audiences, particularly during the first lockdown.

Source: Author.

Half of all new initiatives in 2020 occurred in March, April and May, and 77% of these were related to the pandemic. While all three dimensions of proximity were represented, there was an emphasis on social followed by commercial initiatives, particularly during the lockdown phase.

In line with these findings, staff reported that the pandemic resulted in greater proximity to audiences. For them, the crisis strengthened a bond that had been weakening over time, reflected by the continual drop in circulation. As an editor-in-chief put it, “Covid brought us closer. It restored trust and a relationship we hadn’t had in years. (…) In fact, sales increased” (Editor-in-chief 1). Staff said they felt the pandemic did not change the way in which the paper related with audiences, but rather strengthened the existing relationship; one staff member referred to it as “a moment when readers remembered that L’Eco is necessary to feel you are from Bergamo” (Director 2).

Serving the Community by Providing Information

Journalists and editors-in-chief reported that “all colleagues shared the intention to provide our readers with information that was as accurate as possible. In situations of emergency like this one, the newsroom focuses on its role of service from the point of view of information” (Journalist 1). In this, L’Eco’s journalists faced three main challenges that were common to local media during the pandemic. First, “[they] were forced to adapt [their] routines to work from home” (Journalist 4). Second, they had to “select and report reliable news from within the chaos of (mis)information about Covid-19” (Journalist 1). Third, they had to cover a dramatic local situation while dealing with the disease on a personal level: “many journalists at L’Eco contracted Covid-19 and we all knew someone who was sick or had died because of the virus” (Journalist 3).

On the one hand, the newspaper fostered proximity by addressing audiences as citizens to be informed on matters of public interest, giving them the necessary keys to understand what was happening in their area and what to do to protect themselves and others. It launched the section “Bergamo’s front”, which provided locals with health guidelines and translated national directives into up-to-date practical information for the local context. News was to be presented “in a very clear way, understandable to all” (Journalist 2), often using infographics. This was seen as a key factor in dealing with the pandemic. Another factor staff considered important in creating proximity and trust was an in-depth investigation that helped correct highly inaccurate official records concerning the province’s death toll and helped locals make sense of what was happening in Bergamo. In early 2020, “people fell sick but doctors didn’t arrive fast enough; the obituary section increased enormously, yet the number of officially reported deaths remained low” (Journalist 2).

On the other hand, staff reported that the connection with audiences was reinforced by “L’Eco of life” [I-447], a section launched in March consisting of around two pages per day of audiences’ writings, drawings, poems, or other content about the pandemic. This initiative positioned the newspaper as a kind of glue holding the community together, as staff believed that stay-at-home directives kindled the “need for connection and social interaction” (Journalist 3). Staff stated that this initiative fostered togetherness and showed that L’Eco cared about its community: “People realized that a newspaper is a place where one can be understood” (Editor-in-chief 2). “L’Eco of life” supplemented “Case in festa”, the paper’s traditional “life section” [I-61] that publishes readers’ pictures and messages celebrating graduations, anniversaries, etc.

In general, journalists sought to become closer to audiences by bringing them into the news-making process and giving them the role of contributor (a standard way of relating to audiences, as discussed above). In total, 70% of new or ongoing gatekeeping initiatives carried out in 2020 involved this type of audience inclusion. Of the 24 gatekeeping initiatives launched in 2020, 21 were invitations to submit some kind of material that could fuel news-making. This included initiatives organized both during the lockdown (e.g., the “L’Eco of life” section) and after (e.g., an invitation to submit questions regarding new governmental directives published in June [I-459]).

The way proximity to audiences was fostered reflects Western journalists’ traditional roles of gatekeepers (i.e., reporting trustworthy information, in this case specifically health information) and watchdogs of democracy (i.e., scrutinizing those in power), as well as the role more common among Italian journalists of “letting people express their view” (Splendore Citation2016).

Serving the Community by Addressing Social Needs

Of the 21 social initiatives initially planned for 2020, three were suspended because they would have entailed gatherings around the time of the lockdown (e.g., “Bergamondo” [I-133], mentioned above). The rest were adapted to the subsequent restrictions and went forward, thus creating an opportunity for locals to socialize (e.g., “Millegradini”, a sociocultural walk in the old city [I-163]). The number and variety of initiatives fostering social connection (sport activities, festive events, etc.) led one of the directors to describe L’Eco’s closeness to audiences as the result of “a relationship built day after day. It’s not only an editorial proximity, it’s also a physical one” (Director 1).

The impact of the pandemic can be clearly seen in the social initiatives organized during the lockdown (see and and ), which emphasized solidarity and social interaction. The combination of these initiatives with the provision of information was said to reflect L’Eco’s approach to work based on the common good of its readers: “If there is a serious emergency, in addition to the news front, a social front of solidarity, of fundraising, is immediately launched. This is the difference in our work” (Editor-in-chief 1). Three initiatives were unanimously highlighted across all interviews as bringing the newspaper closer to audiences:

A distribution of 120,000 flags with the inscription “We love Bergamo” [I-450]. This initiative was intended to enhance togetherness and to be “a symbol giving courage to people and representing their desire to keep going despite everything, because so many people died here” (Journalist 3). It was said to be inspired by a similar initiative organized in 2019 to show support for the city’s soccer team [I-424].

A fundraiser that collected 3.5 million euros for facilities hosting COVID-19 patients [I-449]. Fundraising appeared to be a common way of encouraging solidarity between local residents. In 2020, L’Eco also organized three other fundraisers, including one for underprivileged children that it has run since 1951 [I-27].

An online memorial to commemorate the deceased [I-454]. Locals could submit pictures, messages or prayers for people they had known and add names to the list of the deceased. Due to the strict restrictions imposed by the government and the dramatic local situation, Bergamo residents “couldn’t say goodbye, organize funerals, or observe the local custom of gathering in the home of the deceased to mourn together” (Director 1). This was particularly painful because the worship of the deceased is a serious tradition in Bergamo, one of Italy’s most deeply Catholic provinces (Luchetta Citation2020). One of the directors explained:In London you go running in the cemetery. In Paris, you visit them for their artistic value. Here, it’s different. Cemeteries are very busy places because they are cemeteries. Here, there is a city of the living and a city of the dead. So, all we did was give a voice to a need that existed. (Director 2)

Table 2. Initiatives launched between March and May in 2019 and 2020.

It is noteworthy that death has long been an accepted theme of L’Eco. This is related to its ownership by the Church and the legacy of Spada, its former priest-director of 51 years, who greatly expanded the obituaries and small crime news sections (Amigo Citation2022). Today, a yearly booklet commemorating the deceased [I-375] and a section for extended obituaries [I-222] continue this tradition. Locals have even nicknamed L’Eco “the newspaper of the dead” and joke that “no one is really dead until you see it in L’Eco”. In line with this, staff claimed that the newspaper “usually publishes around 70% of deaths in the area” (Manager 2); one stated that “many people buy L’Eco for that reason: to see who died” (Journalist 4). Indeed, L’Eco’s death notices and its in-depth investigation were the main records used to compile the list of the deceased used for the memorial. Staff noted that this gave the paper “the legitimacy to host this event” (Editor-in-chief 2), showing their proximity to the community in a way they felt could not be seen as mere rhetoric by locals.

Together, the initiatives carried out in 2020 reflect L’Eco’s willingness to support the community emotionally and materially whilst fostering a sense of mutuality in terms of social interaction and solidarity. The pandemic intensified this commitment and highlighted the social responsibility taken on by the newspaper in contributing to the wellbeing of its community and helping address some of Bergamo’s challenging problems.

“Price is also a sign of closeness”: Creating Commercial Ties against a Backdrop of Solidarity

In 2020, 14 initiatives were initially planned by marketing and sales staff to increase proximity to audiences in a market perspective. “Because all activity was severely restricted during the first lockdown” (Manager 2), two initiatives were suspended: the subscribers’ club granting members commercial benefits [I-235] and a game organized every year since 1987 based on watching soccer matches in bars [I-62]. The remaining 9 ongoing initiatives largely consisted of marketing games, subscription campaigns and audiences’ ad-based sections. These initiatives invited audiences to help keep L’Eco going by purchasing the newspaper and built customer loyalty through entertainment. For example, “Bollinopoli” [I-354] is an annual contest in which audiences collect stamps published in the newspaper to win prizes.

Commercial initiatives focused on the print edition of the newspaper, which has the most subscriptions and is considered L’Eco’s core business (its website simply reproduces content from the print edition). Staff were largely convinced that “current readers [wouldn’t] adopt the digital version” (Manager 1) and thus tried to “make sure that readers who are hooked today stay for as many years as possible” (Director 1). Because of L’Eco’s slow digital transition, the paper was hit particularly hard by the pandemic. Advertising revenues dropped sharply, and printing and distributing copies became difficult. Consequently, the pandemic pushed L’Eco to develop its commercial connection with audiences, as it can be seen in the greater number of market-driven initiatives in early 2020 (see and and ).

Directors mentioned the two subscription campaigns launched in 2020 [I-444, I-458] as a way of creating proximity to audiences. The price (one euro per week) was considered “a sign of closeness” (Director 2) and translated the desire to provide a service accessible to everyone in a time when people desperately needed information. This effort was also supported by campaign slogans displaying emotional proximity: “Apart but together” and “Starting again, side by side”. While addressing audiences as financial supporters of its business, the newspaper appealed to their solidarity. In times of trouble, it reached out to audiences to show that they were enduring hardship together and that they were doing their best to help but needed help in return. Such an approach echoes Villi and Picard’s (Citation2019) suggestion of adopting audience-based strategies that evoke emotions and a sense of belonging and involvement. The campaigns were considered a success: the paper saw a 30% increase in subscriptions in 2020.

The only commercial initiative that was adapted to conform to pandemic restrictions was “L’Eco-Café” [I-200], a marketing initiative aimed at promoting brand image and sales. In past years, staff would “sell subscriptions at a special price while offering coffee in a stand decorated like a traditional town bar” (Manager 1). Essentially this initiative fostered commercial proximity by recreating a “third place”, a term used by Oldenburg and Brissett (Citation1982) to describe a social environment that is key in establishing social ties and feelings of connection. During the pandemic, this marketing-heavy initiative relied much more on the social dimension by turning into a series of meetings with local organizations’ representatives that were streamed online; the paper also publicized fundraisers supporting these organization’s projects.

Discussion

This paper has examined L’Eco di Bergamo’s proximity to audiences in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. There was a general congruence between actions taken by L’Eco and staff’s discourse. Regarding RQ1, results show that the pandemic prompted L’Eco to make a greater effort to be closer to audiences through specific initiatives. These were shaped by the gatekeeping (particularly “L’Eco of life” section inviting readers to contribute material), commercial (two subscription campaigns) and social (the distribution of a flag, a fundraiser and a memorial) dimensions of proximity. With respect to RQ2, staff also reported a greater closeness to audiences and higher public trust in the newspaper during this time. This was based on higher demand for information and subscriptions, as well as audiences supporting the community through fundraising, grieving together, and expressing their attachment to the social collective by participating in the “L’Eco of life” section and displaying the flag “We love Bergamo”. Explored by RQ3, the impact of the pandemic on L’Eco’s proximity to audiences can be observed not only in staff’s perception of a strengthened connection with audiences, but also in the growth in new initiatives, with an emphasis on initiatives shaped by the social followed by the commercial dimension of proximity, particularly during the first lockdown. The recalibration of the three dimensions brought about by the pandemic shows that creating proximity is both a dynamic and a situated process. It is carried out in dialogue with situations affecting the local context (such as the way the pandemic hit Bergamo) and depends on both the configurations within a news organization (for example, initiatives were suggested by staff from different departments) and the larger society in which the organization operates. Despite staff having to adapt their work routines and deal with a distressing local situation, proximity was created in ways that were consistent with the newspaper’s usual strategies. This was highlighted by staff, who claimed that during the pandemic they worked as they usually do in times of emergency, i.e., providing news and promoting solidarity. In addition, a comparison of pandemic-related initiatives to the rest of the initiatives carried out in 2019 and 2020 shows that the newspaper had already organized fundraisers and subscription campaigns, created a flag, and invited audiences to submit material to fuel news production outside the context of the pandemic. The memorial was the only novel initiative, and even this was in line with L’Eco’s established vocation of worshiping the deceased as exemplified by its local nickname as well as the commemorative booklet and the extended obituaries section.

These results align with studies on how local media navigated the pandemic (discussed above in the section on L’Eco’s context), whether with regard to economic difficulties (Newman et al. Citation2021; AGCOM Citation2020), the significance of news production and provision and the challenges faced in this area (Jukes, Fowler-Watt, and Rees Citation2021; García-Avilés Citation2021; Mheidly and Fares Citation2020; Charon Citation2020), or facilitating acts of mutual help between locals (Quinton Citation2020). This paper thus adds to research demonstrating the meaningful role local media have played in building resilience in their community and helping cope with the pandemic (Hess and Waller Citation2021; Wahl-Jorgensen, Garcia-Blanco, and Boelle Citation2021). Furthermore, this broad alignment suggests that the three dimensions of proximity to audiences observed in L’Eco’s case also shaped other news outlets’ proximity to audiences, although the specific balance of the dimensions and their manifestations were likely different, as these result from factors specific to each news organization.

Results also showed that different strategies to create proximity were undertaken simultaneously, so that L’Eco related with audiences in multi-layered ways. This led me to consider audiences as an elastic figure determined by these strategies, which are shaped by the interplay of the three dimensions and assign audiences various and combined roles to play. The diagram below outlines the different aspects of the plural figure of audiences, as informed by the three-dimensional structure of proximity.

shows that audiences can take on one or more figures related to the roles they are expected to play. Three figures are directly related to each of the dimensions of proximity, while three others reflect the various intersections of the dimensions. These six figures are illustrated below by discussing findings from this study.

Figure 5. The plural figure of audiences, informed by the three dimensions of proximity. Source: Author.

The commercial dimension of proximity concerns strategies that sustain a news organization in a market perspective. Audiences are addressed as direct or indirect providers of financial support, whether as buyers of the newspaper, as a commodity to sell to advertisers, as users producing online data to be monetized, or as members or funders of the news organization or one of its projects or products. This dimension is best reflected by the marketing games organized by L’Eco in 2020 enticing audiences to buy the newspaper to win commercial benefits.

The gatekeeping dimension refers to selecting, producing and presenting news in ways that make it relevant to audiences. Audiences are seen as citizens to be informed about political and non-political issues, and who are more or less actively included in the news-making process. This inclusion ranges from providing audiences with insight into how news is produced to asking them to contribute material to fuel the news-making process to inviting them to co-produce content (Pignard-Cheynel and Amigo Citation2022). For instance, L’Eco’s investigation on the local death toll provided citizens with information empowering them in local civic life, while the “Bergamo’s front” section provided them with practical and health information to cope with the pandemic. The “Tell us a story” section on work done by local volunteers was an example of informing audiences through non-political content, as well as of including audiences in news-making as contributors of material that may be used in news production.

The social dimension refers to news media’s self-assigned role of constructing a feeling of mutuality through strategies to promote social interaction and solidarity. Here, audiences and news organizations act as fellows who take part in and support processes that contribute to the cohesion and well-being of the community. In 2020, for example, L’Eco and its audiences took part in initiatives to foster connections whether virtually (e.g., the memorial) or physically (e.g., “Millegradini”), and provided mutual emotional (e.g., the “We love Bergamo” flag) and material (e.g., fundraising) support.

The intersection of the commercial and gatekeeping dimensions sees audiences as consumers who directly or indirectly support a news organization in exchange for information they consider relevant. This dimension is reflected in local media’s business models which “explain the business logic of specific enterprises and the products, services, and relationships upon which the business and activities are based” (Villi and Picard Citation2019, 121). L’Eco’s business model relies in part on audiences’ purchase of its service as promoted by its annual subscription campaign.

The intersection of the social and gatekeeping dimensions relates to the notion of social spheres, that is, “social situations and environments including those mediated through journalism in which people form connections to others [and] make sense of who they are as individuals as well as collectives” (Hess Citation2013, 484). It involves local media producing content to foster mutuality by enabling audiences to connect or to help each other. Audiences are addressed as “neighbors” living together, with reference to Heider, Mccombs, and Poindexter (Citation2005)’s claim that audiences expect local media to act as a “good neighbor” by “caring about the local community” as well as “offering solutions to community problems”. This intersection is illustrated by staff fostering togetherness and conversation through the “L’Eco of life” section.

The intersection of the commercial and social dimensions refers to local media’s corporate social responsibility (CSR), in which audiences play the role of stakeholder. CSR is based on the idea that “an organization has obligations to serve beyond just financial gains” and implies that companies can do good for people and their community (Scheinbaum, Lacey, and Liang Citation2017, 411). This intersection can be seen in local media carrying out strategies shaped by the social dimension of proximity even as they remain a commercial venture. Here, local media relate with audiences as stakeholders by seeking to understand their concerns and views regarding the issues that affect the community and then to incorporate those concerns in their strategies. This way of relating to audiences not only promotes the collective well-being but also the news organization’s own profitability. Research has shown that associating an organization with relevant social actions may have positive effects on brand attitude and potential purchase of a product (Ferrell et al. Citation2019). In this perspective, audiences’ financial support for a news organization demonstrates a deeper identification with the organization’s values, principles or ideology and a recognition of the impact it has on its community. The two subscription campaigns launched by L’Eco during the lockdown illustrate this intersection. During the pandemic, the newspaper sought commercial proximity by indicating that it was a company that did good for local society, and therefore asked for audience’s support using slogans that conveyed solidarity and togetherness.

It is noteworthy that many of the new pandemic-related initiatives in 2020 were infused by a sense of mutuality and correspond to the latter two intersections involving the social dimension. This reflects the increased importance of this dimension of proximity during the pandemic outside of the purely social initiatives undertaken at that time.

Conclusion

This study proposed a conceptualization of proximity to audiences as a dynamic balance between three structuring dimensions—gatekeeping, social, and commercial—with a focus on audiences as a plural figure encompassing citizens, fellows, financial supporters, consumers, neighbors, and/or stakeholders. This conceptualization was developed based on a case study of the Italian daily L’Eco di Bergamo. Findings of this case study showed that the COVID-19 pandemic led L’Eco to seek greater closeness with audiences through overlapping and complementary strategies shaped in particular by the social dimension of proximity. However, while staff discourse and the greater number of initiatives taken indicate that L’Eco’s proximity to audiences increased during the pandemic, the crisis does not seem to have produced significant changes in the types of initiatives taken to relate with audiences, despite changes in staff work routines. Initiatives organized in 2020 were similar to those in 2019 and previous years, and staff claimed that they proceeded as they usually did in times of emergency. Further research could test this finding by looking at a broader time period to explore whether the increase in proximity and rebalancing of its dimensions simply represented a “bump” or a more long-lasting change.

This study aimed to contribute to conceptualizations of shared notions in local journalism (Gulyas and Baines Citation2020), specifically proximity to audiences. My conceptualization brings together various aspects of proximity that are usually discussed separately in the literature, thus offering a more comprehensive framework for analyzing local media’s proximity to audiences. At the same time, it reduces the ambiguity of this notion by assigning only three dimensions to proximity, hence allowing for more comparability between studies. Further research could explore how the proposed three-dimensional structure of proximity is manifested in other news media and time periods, since this paper is based on a single case. A deeper understanding would also be gained by exploring proximity from an audience perspective. Rather than a one-sided construction, proximity is a circular relationship that is constantly being renegotiated, based on audiences and news organizations’ practices and expectations about what local journalism should be.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 A total of 77 initiatives were carried out in 2019.

References

- Accertamenti Diffusione Stampa (ADS). 1979–2021. https://www.adsnotizie.it.

- Ahva, L., and M. Pantti. 2014. “Proximity as a Journalistic Keyword in the Digital era.” Digital Journalism 2 (3): 322–333. doi:10.1080/21670811.2014.895505.

- Amigo, L. 2022 “Local Media’s Proximity to Audiences through a Historical Lens: The Case of L’Eco di Bergamo”. Manuscript in preparation.

- Arnold, C., and S. Blackman. 2021. “Retrieving and Repurposing: A Grounded Approach to Hyperlocal Working Practices Through a Subcultural Lens.” Digital Journalism 1–19. doi:10.1080/21670811.2021.1880330.

- Autorità per le Garanzie nelle Comunicazioni (AGCOM). 2020. “Communications in 2020. The Impact of Coronavirus in Regulated Areas.” https://www.agcom.it/documents/10179/19412594/Documento+generico+30-07-2020/b632ff6b-e5a0-4043-9a28-ff1151585f96?version=1.0.

- Ballarini, L. 2008. “Presse locale, un média de diversion.” Réseaux 148-149 (2): 405–426. doi:10.3166/Réseaux.148-149.405-426.

- Bardin, L. 1977. L’analyse de contenu. Paris, France: Presses Universitaires de France.

- Bernucci, C., C. Brembilla, and P. Veiceschi. 2020. “Effects of the Covid-19 Outbreak in Northern Italy: Perspectives from the Bergamo Neurosurgery Department.” World Neurosurgery 137: 465–468.e1. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2020.03.179.

- Bousquet, F. 2015. “L’information service au cœur de la reconfiguration de la presse infranationale française.” Réseaux 5: 163–191. doi:10.3917/res.193.0163.

- Bousquet, F. 2018. “Les correspondants locaux, acteurs dans la constitution de communautés de lecteurs et producteurs d’informations.” Le Temps des Médias 31: 62–75. doi:10.3917/tdm.031.0062.

- Brosius, H.-B., and P. Eps. 1995. “Prototyping Through key Events.” European Journal of Communication 10 (3): 391–412. doi:10.1177/0267323195010003005.

- Casero-Ripollés, A. 2021. “The Impact of Covid-19 on Journalism: A Set of Transformations in Five Domains.” Comunicação e Sociedade 40: 53–69. doi:10.17231/comsoc.40(2021).3283.

- Castriota, S., M. Delmastro, and M. Tonin. 2020. National or Local? The Demand for News in Italy During Covid-19. Bonn, Germany: Institute of Labor Economics (IZA). ISSN: 2365-9793.

- Charon, J.-M. 2020, March 24. “La presse écrite à l’épreuve de la pandémie. Alternatives économiques.” https://www.alternatives-economiques.fr/presse-ecrite-a-lepreuve-de-pandemie/00092248.

- Conboy, M. 2004. “New Configurations for the Definition of Journalism.” In Journalism a Critical History, edited by M. Conboy, 222–237. London: SAGE.

- Cornia, A. 2021. “Italy.” In Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2021, edited by N. Newman, R. Fletcher, A. Schulz, S. Andı, C. Robertson, and R. K. Nielsen, 87. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Ferrell, O., D. Harrison, L. Ferrell, and J. Hair. 2019. “Business Ethics, Corporate Social Responsibility, and Brand Attitudes: An Exploratory Study.” Journal of Business Research 95: 491–501. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.039.

- Ferrer-Conill, R., and E. Tandoc. 2018. “The Audience-Oriented Editor.” Digital Journalism 6 (4): 436–453. doi:10.1080/21670811.2018.1440972.

- Franklin, B., and M. Carlson, eds. 2011. Journalists, Sources, and Credibility. New York: Routledge.

- Galtung, J., and M. Ruge. 1965. “The Structure of Foreign News: The Presentation of the Congo, Cuba and Cyprus Crises in Four Norwegian Newspapers.” Journal of Peace Research 2: 64–90. doi:10.1177/002234336500200104.

- Garavaglia, C., A. Sancino, and B. Trivellato. 2020. “Italian Mayors and the Management of Covid-19: Adaptive Leadership for Organizing Local Governance.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 62 (1): 76–92. doi:10.1080/15387216.2020.1845222.

- García-Avilés, J. 2021. “Journalism as Usual? Managing Disruption in Virtual Newsrooms during the Covid-19 Crisis.” Digital Journalism 9 (9): 1239–1260. doi:10.1080/21670811.2021.1942112.

- Geana, M. 2009. “Marketing.” In Encyclopedia of Journalism, edited by C. Sterling, 872–876. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Guimerà, J., D. Domingo, and A. Williams. 2018. “Local Journalism in Europe. Reuniting with its Audiences.” Sur le Journalisme, About Journalism, Sobre Jornalismo 7 (2): 20–27. doi:10.25200/SLJ.v7.n2.2018.355.

- Gulyas, A., and D. Baines. 2020. “Introduction. Demarcating the Field of Local Media and Journalism.” In The Routledge Companion to Local Media and Journalism, edited by A. Gulyas and D. Baines, 1–23. London: Routledge.

- Hanitzsch, T., and T. Vos. 2018. “Journalism Beyond Democracy: A New Look Into Journalistic Roles in Political and Everyday Life.” Journalism 19 (2): 146–164. doi:10.1177/1464884916673386.

- Heider, D., M. Mccombs, and P. Poindexter. 2005. “What the Public Expects of Local News.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 82: 952–967. doi:10.1177/107769900508200412.

- Hess, K. 2013. “Breaking Boundaries: Recasting the ‘Local’ Newspaper as ‘Geo-social’ News in a Digital Landscape.” Digital Journalism 1 (1): 48–63. doi:10.1080/21670811.2012.714933.

- Hess, K., and L. Waller. 2017. Local Journalism in a Digital World. London: Palgrave.

- Hess, K., and L. Waller. 2021. “Local Newspapers and Coronavirus: Conceptualizing Connections, Comparisons and Cures.” Media International Australia 178 (1): 21–35. doi:10.1177/1329878X20956455.

- Hubé, N. 2010. “La “Une” comme outil marketing de “modernisation” de la presse quotidienne.” Questions de Communication 17: 253–272. doi:10.4000/questionsdecommunication.389.

- Jenkins, J., and R. Nielsen. 2020. “Preservation and Evolution: Local Newspapers as Ambidextrous Organizations.” Journalism 21 (4): 472–488. doi:10.1177/1464884919886421.

- Jukes, S., K. Fowler-Watt, and G. Rees. 2021. “Reporting the Covid-19 Pandemic: Trauma on our own Doorstep.” Digital Journalism, 1–18. doi:10.1080/21670811.2021.1965489.

- Knoben, J., and L. Oerlemans. 2006. “Proximity and Inter-Organizational Collaboration: A Literature Review.” International Journal of Management Reviews 8 (2): 71–89. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2370.2006.00121.x.

- Le Bart, C., and R. Lefebvre. 2005. “Une nouvelle grandeur politique ?” In La proximité en politique, edited by C. Le Bart and R. Lefebvre, 11–30. Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes.

- Le Bohec, J. 1998. “La Question du ‘Rôle Démocratique’ de la Presse Locale en France.” Hermès 26-27: 185–198.

- Luchetta, A. (Director). 2020, September 13. “Mòla mia” [documentary]. RAI1.

- Marmaros, D., and B. Sacerdote. 2006. “How do Friendships Form?” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 121 (1): 79–119. doi:10.1093/qje/121.1.79.

- Matthews, R. 2015. “The Provincial Press in England: An Overview.” In The Routledge Companion to British Media History, edited by M. Conboy and J. Steel, 239–249. London: Routledge.

- McQuail, D. 2013. Journalism and Society. London: SAGE.

- Mheidly, N., and J. Fares. 2020. “Leveraging Media and Health Communication Strategies to Overcome the COVID-19 Infodemic.” Journal of Public Health Policy 41 (4): 410–420. doi:10.1057/s41271-020-00247-w.

- Murru, M., and F. Pasquali, eds. 2020. “Local matters. Le sfide et le opportunità dell’informazione locale.” Problemi dell’informazioni 15 (3). Bologna.

- Nelson, J. 2021. “The Next Media Regime: The Pursuit of “Audience Engagement”.” Journalism 22 (9): 2350–2367. doi:10.1177/1464884919862375.

- Newman, N., R. Fletcher, A. Schulz, S. Andi, C. Robertson, and R. K. Nielsen. 2021. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2021. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Nicotra, F. 2021. La mortalità in Lombardia nel 2020. Milan: Polis Lombardia.

- Oldenburg, R., and D. Brissett. 1982. “The Third Place.” Qualitative Sociology 5: 265–284. doi:10.1007/BF00986754.

- O’Neill, D., and C. O’Connor. 2008. “The Passive Journalist.” Journalism Practice 2 (3): 487–500. doi:10.1080/17512780802281248.

- Paulussen, S., A. Heinzonen, D. Domingo, and T. Quandt. 2007. “Doing it Together. Citizen Participation in the Professional News Making Process.” Observatorio Journal 3: 131–154. doi:10.15847/obsOBS132007148.

- Pavlik, J. 2021. “Engaging Journalism: News in the Time of the Covid-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Media and Communication Research 13 (1): 1–17.

- Perreault, M., and G. Perreault. 2021. “Journalists on Covid-19 Journalism: Communication Ecology of Pandemic Reporting.” American Behavioral Scientist 65 (7): 976–991. doi:10.1177/0002764221992813.

- Pignard-Cheynel, N., and L. Amigo. 2022. “(Re)connecting with Audiences. An Overview of Audience-inclusion Initiatives in European French-speaking Local News Media.” Manuscript submitted.

- Quinton, F. 2020, March 16. “Face à l’épidémie de Covid-19, les médias locaux veulent jouer un rôle actif dans les solidarités.” La Revue des Médias. https://larevuedesmedias.ina.fr/epidemie-coronavirus-covid-19-medias-locaux-role-solidarites.

- Reader, B., and J. Hatcher. 2020. “Business and Ownership of Local Media: An International Perspective.” In The Routledge Companion to Local Media and Journalism, edited by A. Gulyas and D. Baines, 205–214. New York: Routledge.

- Ringoot, R., and Y. Rochard. 2005. “Proximité éditoriale : normes et usages des genres journalistiques.” Mots. Les Langages du Politique 77: 73–90. doi:10.4000/mots.162.

- Scheinbaum, A., R. Lacey, and M. Liang. 2017. “Communicating Corporate Responsibility To Fit Consumer Perceptions.” Journal of Advertising Research 57 (4): 410–421. doi:10.2501/JAR-2017-049.

- Shoemaker, P., J. Lee, G. Han, and A. Cohen. 2007. “Proximity and Scope as News Values.” In Media Studies: Key Issues and Debates, edited by E. Devereux, 231–248. London: SAGE.

- Shoemaker, P., T. Vos, and S. Reese. 2009. “Journalists as Gatekeepers.” In The Handbook of Journalism Studies, edited by K. Wahl-Jorgensen and T. Hanitzsch, 73–87. New York: Routledge.

- Sommer, C. 2018. “Market Orientation of News Startups.” The Journal of Media Innovations 4 (2): 35–54. doi:10.5617/jomi.v4i2.1507.

- Splendore, S. 2016, November. “Italy. Country Report. Worlds of Journalism Study.” https://worldsofjournalism.org/country-reports/.

- Splendore, S. 2017. Giornalismo ibrido. Come cambia la cultura giornalistica in Italia. Roma: Carocci.

- Strauss, A. 1992. La trame de la négociation. Sociologie qualitative et interactionnisme. Paris: L’Harmattan.

- Tandoc, E., J. Jenkins, R. Thomas, and O. Westlund, eds. 2021. Critical Incidents in Journalism: Pivotal Moments Reshaping Journalism Around the World. London: Routledge.

- Tandoc, E., and T. Vos. 2016. “The Journalist is Marketing the News: Social Media in the Gatekeeping Process.” Journalism Practice 10 (8): 950–966. doi:10.1080/17512786.2015.1087811.

- Villi, M., and R. Picard. 2019. “Transformations and Innovation of Media Business Models.” In Making Media. Production, Practices, and Professions, edited by M. Deuze and M. Prenger, 121–131. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Wahl-Jorgensen, K., I. Garcia-Blanco, and J. Boelle. 2021, September 23. The Role of Community Journalists: The “Cheerleader” and the Challenge to Role Conceptions. Paper presented at the Future of Journalism Conference, Cardiff University, Wales.

- Wallaschek, S., C. Starke, and C. Brüning. 2008. “Solidarity in the Public Sphere: A Discourse Network Analysis of German Newspapers.” Politics and Governance 8 (2): 257–271. doi:10.17645/pag.v8i2.2609.

- Wenzel, A., and J. Nelson. 2020. “Introduction “Engaged”.” Journalism: Studying the News Industry’s Changing Relationship with the Public. Journalism Practice 14 (5): 515–517. doi:10.1080/17512786.2020.1759126.

- Zelizer, B. 1992. “CNN, the Gulf War, and Journalistic Practice.” Journal of Communication 42 (1): 66–81. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1992.tb00769.x.