ABSTRACT

At a time when local journalism is under threat, regional newsrooms can play a crucial role in working with communities to confront shameful truths and profound failures. The regional city of Ballarat emerged as an “epicentre” of clergy sexual abuse through Australia’s landmark Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (2013–2017). This article examines how the regional city’s newspaper, The Courier, bore witness to these crimes and their impacts within its local community. A content and thematic analysis of coverage of child sexual abuse from 2010 to 2019 documents how The Courier’s locally produced journalism revealed to its audience the extent of abuse, helping to acknowledge and face crimes that had occurred in Ballarat’s local institutions. The interlinked themes of revelation, reckoning and recovery demonstrate how local journalism can work with its community to address traumatic events that occur within its geosocial space. Local media bore witness on multiple levels, as both the amplifier of stories told by survivors and the facilitator of community processes of reckoning and recovery. We refer to this special form of local journalism as “proximal” media witnessing.

Introduction

Ballarat and its institutions were an important focus of Australia’s landmark Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse 2013–2017 (RCIRCSA or Child Abuse Royal Commission). While this national inquiry was wide ranging in its scope, two of its highest profile Case Studies, 28 and 35, interrogated the Catholic Church’s response to decades of sexual abuse in orphanages, schools, and churches in the Ballarat diocese. Over five years of unprecedented national media coverage of the royal commission (Waller, Dreher, and Hess Citation2020), this regional Victorian city came to be widely recognised as an “epicentre” of clergy sexual abuse. Australian and global audiences were confronted by public commentaries that represented Ballarat as “one of the most dangerous places to be a child” in the 1970s, when local paedophile priests and Christian Brothers were enabled in their crimes through Catholic Church inaction and cover-ups (Marr Citation2013, 9).

The Child Abuse Royal Commission has been theorised as a national intervention that changed the nature of public understanding about sexual abuse of children in Australian institutions. According to Wright and Swain (Citation2018, 1), the Commission succeeded in bringing “ … into public consciousness the issue of child sexual abuse, making the problem nameable and the subject speakable in new ways”. News media was a significant actor in raising the issue of child sexual abuse on the public agenda and eliciting the public response through its reporting of the royal commission (see McCallum and Waller Citation2021). This reflected the global experience. For example, Powell and Scanlon (Citation2015) document the role of media in reporting on child sexual abuse in Ireland, saying that “the media has been instrumental in calling powerful institutions – notably the Catholic Church – to account for their handling of abuse”.

In Australia, journalism research has tended to focus on the work of investigative journalists, such as Joanne McCarthy of the regional Newcastle Herald, whose coverage of local clerical child sexual abuse is widely understood as a trigger for the RCIRCSA (McPhillips Citation2021; Muller Citation2017). Such campaigning journalism was critical to achieving a national inquiry, while national coverage of the commission kept the issue at the forefront of the national agenda. However, to date there has been little research addressing how local journalism reported on institutional child sexual abuse within communities that have been the focus of the national story (cf Hess et al. Citation2021). This article addresses that gap through a study of locally produced news examining how local journalism can bear witness to child sexual abuse. Our aim was to explore how journalists who were part of the Ballarat community took responsibility for witnessing the issue of institutional child sexual abuse in their midst. Our inquiry builds on a body of scholarship theorising the phenomenon of media witnessing (Chouliaraki Citation2010; Peters Citation2001; Zelizer Citation2002) by exploring witnessing in the local journalism context. Media witnessing typically focuses on how journalists experience distant suffering on behalf of their audiences, but here we are concerned with witnessing when the local media organisation is closely connected with the institutions and events in the community on which it is reporting. We draw on a recent body of research concerned with how media audiences experience, witness, and address suffering within their local contexts as a proximal phenomenon and everyday condition (eg: Ong Citation2015; Florea and Woelfel Citation2022). While it is widely accepted in journalism studies that news audiences want to know about their own community first (Van Dijk Citation1988), here we understand proximity is not limited to geographical and psychological closeness but also historical, social and cultural nearness that a news story is apt to realise (Florea and Woelfel Citation2022, 329). With a focus on the texts produced by journalists in this local context, we conceptualise a particular type of witnessing that is not distant but “proximal” (Ong Citation2015), where the local news media reveals past trauma, reckons with its impacts, and recovers with its community.

Our text-based approach acknowledges the social and discursive dimensions of proximity as being embedded in historical, social and political contexts of the event or issue (Van Dijk Citation1988, 124). We therefore conducted a textual analysis of reporting on child sexual abuse in the decade surrounding the Royal Commission (2010–2019) in Ballarat’s The Courier. A comprehensive search generated a corpus of 1267 news items that provided the basis for a qualitative thematic analysis.Footnote1 We first document the volume and sustained nature of locally produced journalism, editorial “ownership” and involvement in local community campaigns. The sections that follow present the thematic analysis, which is mapped across three phases: 1. From 2011 routine court reporting of criminal cases against priests and brothers for child sexual offences; 2. The Courier’s exclusive story of 40 historical suicides linked to child sexual offences by priests at a single Ballarat primary school, which was the catalyst for a state-based inquiryFootnote2 that in turn created the conditions for the calling of the national inquiry; and 3. Extensive local reporting of the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (2013–2017). We then examine the local newspaper’s role in working with the community to reckon with its past through survivor-centred journalism and editorial leadership, and taking part in its recovery through a public commitment to the Loud Fence movement. This community campaign began in Ballarat, and involves people tying ribbons to the fences of churches, schools and other local institutions where child sexual abuse has taken place in order to acknowledge and show solidarity with survivors and victims. Finally, we address questions about the enduring but changing place of local journalism in the contemporary media landscape and its role in the discussion of major issues in local communities.

We argue that while there has been extensive discussion about the fate of local journalism through the disruption to the news business model, closure of newsrooms, printed newspapers and “news deserts”, little attention has been paid to locally produced journalism as a source of evidence for public understanding of national issues in the communities that local news outlets serve. There is also a need to study closely the production, content and impact of local news texts to address how journalism can reckon with its own relevance in this time of extreme disruption (Hess and Waller Citation2017; Callison and Young Citation2020). We conclude that despite facing challenging economic and resourcing circumstances, The Courier’s editors and journalists committed to bearing witness on behalf of their audience, whose histories and futures are enmeshed with Ballarat’s institutional abuse.

Bearing Witness in Local News Contexts

Local journalism has always existed in a state of paradox because it is understood as both important and undervalued (Anderson Citation2020, 147). Once regarded by journalism scholars as not very exciting (Nielsen Citation2015a, xi), in recent times it has attracted growing attention for its role as “a key pillar in the lives of communities around the world” (Gulyas and Baines Citation2020, 1). These acknowledgements of the significant political and social roles played by local journalism are linked to its informational and community relationship functions. There has also been growing awareness of local journalism’s important, but endangered position in macro media ecosystems due to the breakdown of business models that once sustained it (Abernathy Citation2016; Wadbring and Bergström Citation2017).

There are three broad currents running through contemporary literature on local news. The oldest research tradition is concerned with local media’s backbone political function, highlighting its role in political communication and in underpinning democratic systems and processes in local communities (McNair Citation2018; Nielsen Citation2015b). The second relates to business models and the future of local journalism (Franklin Citation2014; Olsen Citation2021; Picard Citation2010). The third strand can be described as conceptualising local journalism in terms of community interaction and local journalists as “community champions” (Gulyas and Baines Citation2020). This focus also emphasises the importance of “sense of place” and local media’s role within the communities it serves (Gutsche and Hess Citation2020; Usher Citation2019; Yamamoto Citation2011). As we have argued elsewhere, while local news outlets are clearly influenced by technological advances and economic fluctuations, they closely reflect the specific historical, geographical, social, and political contexts out of which they have arisen (Hess and Waller Citation2017). Furthermore, when an event of national or international news value occurs within their “patch”, local newspapers play a different cultural role to their big city counterparts. While major news media move on to the next big story, the aftermath of a major local event like a heinous crime or natural disaster requires ongoing local coverage (Hess and Waller Citation2012). At these times, local newspapers can also play an important role in helping their audience come to terms with negative media representations of their place in the world by reaffirming an “insider” view (Hess and Waller Citation2020). The Opinion section, and especially the editorial, provides a key platform for navigating through painful and difficult public conversations because editorials are a vehicle for the newspaper to set a public agenda and state its position to influence reader responses (Le Citation2010). The carefully curated editorial space occupied by opinion pieces, cartoons and letters to the editor are also used to give expression to “insider” opinions the newspaper decides to sponsor and amplify.

Anderson (Citation2020, 146) argues much work remains to be done when it comes to gaining a deeper understanding of the world of local journalism. For example, there is a need for further critique and analysis relating to journalism ethics and questions of journalistic authority at the local level (Hess et al. Citation2021). It could be argued that the strong focus on the normative roles of local journalism and its precarious future have impeded scholarly interest in analysing local news texts for their social, political, and cultural significance.

One of Australia’s oldest newspapers, The Courier has served the Victorian city of 100,000 citizens since 1867. The 10-year period of our study was a challenging time for the newspaper and its journalists. Between 2010 and 2019 several hundred Australian mastheads closed, with regional areas hardest hit (ACCC Citation2019; Dodd and Ricketson Citation2021). Surviving newspapers underwent rapid change with impacts on production processes, staffing, and editorial resources (Nielsen Citation2015b; Hess and Waller Citation2017; Fisher, Nolan, and McGuinness Citation2022). In 2015, The Courier’s former owner, Fairfax Media, undertook a significant restructure that accelerated the pressure. Then in 2018, The Courier was among 160 regional mastheads that were part of Fairfax’s merger with Nine, before being sold to Australian Community Media (ACM) in 2019. We do not purport to make causal connections between The Courier’s struggle to remain economically, politically and socially viable, and the nature and content of its reporting. However, it is important to identify models of best practice local journalism as it reckons with its relevance in a time of severe disruption (Callison and Young Citation2020).

Proximal Witnessing

The concept of media witnessing provides an entry point through which to understand the role of The Courier in telling the story of institutional child sexual abuse to its audience. John Durham Peters in his landmark essay (2001) points out that witnessing is a key concept in both legal and media studies. In the law, the witness is “a privileged source of information for judicial decisions” (2001, 708) and witnessing “a subtle array of practices for securing truth from the facts” (2001, 209). Witnessing is understood as a process for truth-telling, acknowledgement and moral accountability (Hill Citation2019). Peters (Citation2001) says, “[t]o witness an event is to be responsible in some way to it”. Indeed, the Chair of the RCIRCSA, Justice Peter McClellan, identified taking responsibility as a key tenet of witnessing theory when he called on its commissioners to

[b]ear witness on behalf of the nation to the abuse and consequential trauma inflicted upon many people who have suffered sexual abuse as children. The bearing of witness is the process of making known what has happened … The bearing of witness informs the public consciousness and prepares the community to take steps to prevent abuses from being repeated in the future. (McClellan Citation2016)

Peters (Citation2001) reminds us that the transformation from experience to discourse lies at the heart of communication theory. In bearing witness, the journalist records and articulates the suffering on behalf of the audience. Chouliaraki argues that journalism “turns evidence of human suffering into moral discourse so as to invite our judgement and action upon it” (Citation2013b, 271). In this way, the text produced by the journalist and shared with the audience is a significant artefact of bearing witness. While Hill (Citation2019) suggests witnessing scholars such as Chouliaraki place too much emphasis on the text, we contend that media texts offer a lasting record of the act of witnessing and its outcomes. Zelizer (Citation2002) demonstrates how journalistic witnessing offers a way of collectively working through shared traumatic experience, by bringing individuals together towards recovery. Bearing witness “moves individuals from the personal act of “seeing” to the adoption of a public stance by which they become part of a collective working through trauma together” (Zelizer Citation2002, 698). She identifies three stages of recovery from a collective traumatic event in which news media organisations can play a role: establishing safety; engaging in remembrance and mourning, and reconnecting with ordinary life.

Scholarship on media witnessing typically concerns the mediation of distant suffering (Chouliaraki Citation2010, 12), whereby the journalist takes responsibility for bringing physically or historically distant traumas or atrocities to the attention of the public who was not there, positioning the audience as a witness to the depicted events (Frosh and Pinchevski Citation2009, 1). This dominant conceptualisation (Peters Citation2001; Zelizer Citation2002; Chouliaraki Citation2010) does not account for contexts where the audience and journalist is in close proximity to, and part of, the community where traumatic events took place. Proximity here encompasses both geographical closeness as well as historical, social and cultural nearness that will be realised as a journalist brings a previously untold news story to its audience (Florea and Woelfel Citation2022, 329). We contend that it is at the level of local journalism, whereby the local journalist is both the distant witness and a member of the local community, that the practices of bearing witnesses are most challenging, but that this aspect of witnessing has been under-studied.

Ong (Citation2015) provides an important baseline study of how audiences experience, witness, and address suffering within their local contexts. He says “The mediation of suffering is not only a distant but also a proximal phenomenon and even everyday condition” (Ong Citation2015, 607). We argue there has been little attention paid in media and journalism studies to the role of the journalist in “the everyday condition” of witnessing at the local level. This brings a range of understudied considerations, whereby the journalist working for a local media organisation, as an integral institution of the community, takes on the role of providing testimony to the community, about the community, on behalf of the community. There is a need for empirical research to investigate how a local news organisation might take responsibility for providing testimony about historical trauma and suffering that was, and continues to be, embedded in the social and cultural experience of its community. Local reporters and editors’ “sense of place” means they have a more intimate relationship with their sources and audiences, which we will argue enables them to bear witness “first hand” over a sustained period and from close range. Our study examines how The Courier bore witness on multiple levels, as both the amplifier of stories told by survivors and the facilitator of community processes of reckoning and recovery.

Research Approach

Our aim was to analyse how Ballarat’s local newspaper, The Courier, bore witness “proximally” to institutional child sexual abuse within and on behalf of its local community that was at the centre of allegations of clerical abuse through the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse. We asked:

RQ1: How did The Courier bear witness to institutional child sexual abuse within and on behalf of its local community?

RQ2: Did The Courier provide sustained coverage and significant investment of editorial resources in the issue of child sexual abuse from 2010 to 19?

RQ3: What were the main themes in The Courier’s coverage of child sexual abuse from 2010 to 19?

We first identified and retrieved all news texts pertaining to child sexual abuse published in The Courier between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2019.Footnote3 Articles were accessed using the NewsBank: Access Global and Factiva databases. Print and online content was included in our dataset to generate the most complete picture of The Courier’s coverage across all editions in the 10-year period, enabling an assessment of how the issue emerged, changes in volume and a judgement on whether editorial focus was sustained. To mitigate concerns about the “increasingly inconsistent and ad hoc nature” of online databases (Blatchford Citation2020, 143), articles were cross-referenced from NewsBank and Factiva and incomplete metadata was manually cross-checked against The Courier’s website, resulting in a dataset that we are confident represents the newspaper’s coverage of the issue. The final dataset consisted of 1267 unique articles. Article data and metadata consisting of the date, headline, author/s, page number (if applicable), word count, article type, source, and body text was collected and loaded into an Excel database.

The content analysis captured the volume of news and editorial content, key phases in the coverage, the number of locally produced stories, and the number of editorials. Editorials were an important focus because this is where newspapers state their position on, and take ownership of, an issue (Le Citation2010). We also paid close attention to authorship by local journalists as evidence of the news organisation’s ongoing commitment to, and resourcing of, the story. The second stage of the research entailed a thematic analysis of The Courier’s locally produced journalism. This method of textual analysis pays close attention to the historical context in which each story was produced, which Van Dijk (Citation1988) considers a contingent condition to proximity’s news value. It also emphasises the language used and the interrelation between news and editorial content (see McCallum and Waller Citation2020). Thematic analysis involved a close reading of articles produced during the key moments of coverage and the editorials identified through the content analysis. The textual analysis investigated the nature of reporting and editorialising and through this process three temporally-guided themes were identified: Revelation, whereby The Courier made public the scale and wide-reaching impacts of previously under-reported crimes that had taken place; Reckoning where through its editorials it confronted Ballarat’s institutional child sexual abuse, and Recovery, whereby The Courier worked with the community to come to terms with its past, particularly through its commitment to the survivor stories and the Loud Fence movement. Together, these themes explicate how a local news organisation such as The Courier can bear witness in the close context of the local community.

The Nature of Locally Produced News Content in the Courier 2010–2019

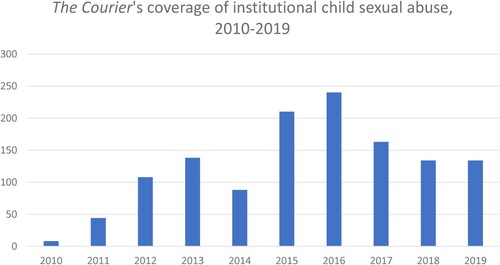

The content analysis revealed the yearly and monthly overall volume of reporting. Our findings show that The Courier provided sustained coverage of the issue, producing more than 1200 items across the 10-year period, with coverage peaking in 2015–2016 at the height of the Child Abuse Royal Commission (see ).

identifies the sustained nature of The Courier’s coverage and the key phases of its reporting. Barely registering for The Courier before 2011, routine court reporting of the prosecution of offending priests and brothers in 2011 raised the issue of child sexual abuse on its agenda. In 2012, its exclusive reporting of a leaked Victoria Police investigation by Detective Kevin Carson into 40 historical suicides linked to Catholic schools in the diocese helped create public pressure for a state-based inquiry. Reporting of the 2012–2013 Victorian Inquiry into the Handling of Child Abuse by Religious and other Non-government Organisations intensified the newspaper’s focus, while attention peaked during the national RCIRSA (2013–2017). The single highest monthly volume of coverage occurred in May 2015, during RCIRCSA public hearings into Case Study 28: Catholic Church Authorities in Ballarat. Other key peaks in coverage occurred in February 2016, when a group of survivors who had been abused in Catholic institutions in Ballarat travelled to Rome to bear witness to Cardinal George Pell’s virtual testimony before the RCIRCSA, and December 2017, when the RCIRCSA handed down its final report.

Table 1. Key phases in The Courier’s coverage of institutional child sexual abuse, 2010–2019.

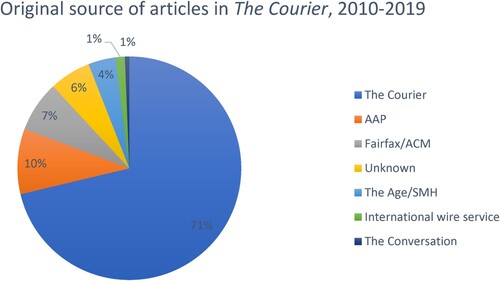

Our study is particularly concerned with the in-house production of news by local newsrooms. Author metadata enabled us to identify the source of the article: whether local (original reporting or commentary produced locally by The Courier), or external (sourced from another Fairfax/ACM newspaper or a news agency such as Australian Associated Press). This analysis revealed that contrary to expectations in a time of newsroom mergers and contraction, a significant majority (71%) of The Courier’s content was locally produced (see ).

Analysis of author metadata also showed that while many Courier reporters contributed articles over the study period, there tended to be one or two main reporters who produced most news reports at any given time. From May 2011 to February 2013, this was Tom McIlroy (55 articles, notably including report of the trials of former Christian Brother Robert Best and the Victorian inquiry). Fiona Henderson produced 100 articles from February 2013 through to December 2016, including intensive coverage of the May 2015 RCIRCSA public hearings held in Ballarat. Melissa Cunningham wrote more than 200 articles between May 2015 and March 2017, including dispatches from Rome where she had travelled with survivors to bear witness to Pell’s testimony.

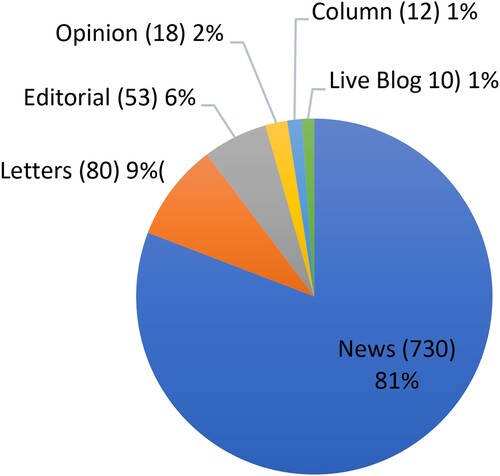

Analysis of the nature of The Courier’s locally produced content () shows that while news reports dominated, opinion pieces, letters to the editor and editorials played an important role. Newspaper editorials have been defined as “unsigned” opinion pieces that function “as official expressions of a media position on an issue they choose to highlight over all others in a given context” (Le Citation2010, 3). Editorials are also strategic sites for framing and agenda setting, with McCombs (Citation1997, 438) stating that they “actively seek to move issues onto the public agenda”. The Courier published 53 editorials related to the issue of child sexual abuse in the Catholic Church during the study period, or 6% of the total local coverage, suggesting a prioritising of the issue by The Courier’s editors.

Thematic Analysis: How The Courier Bore Witness to Child Sexual Abuse

Revelations of Ballarat’s Dark Past

The first theme identified through the textual analysis was the emergence of stories about historical child sexual abuse. Institutional child sexual abuse was not an issue on The Courier’s agenda before 2011 (), when it gave prominent coverage to the trial of former Ballarat Christian Brother Robert Best on six counts of indecent assault against schoolboys when he was a teacher and headmaster at St Alipius Boys’ School in Ballarat East from 1968 to 1973. Presented in the routine style of court reports, this early coverage gave little sense of the wider context of clergy sexual abuse or its impacts. From 2012, in line with the global awareness of the issue (Kitzinger Citation2004), The Courier’s reporting began to focus on the ongoing and devastating impacts of abuse on victims, their families and the wider community through suicide, mental illness and substance abuse. In April 2012, it broke the story that a Victoria Police investigation by Detective Kevin Carson had linked more than 40 deaths by suicide to clergy sexual abuse in the region, including 34 cases linked to Best and convicted paedophile priest Gerald Ridsdale (McIlroy Citation2012a). Reporter Tom McIlroy interviewed two survivors of Best, who together helped to forge a new survivor-focused style of reporting for The Courier by using their real names rather than pseudonyms or codes. One survivor was quoted: “When a victim is believed by the authorities there is such a relief of stress and pressure, you feel justified in going to the police” (McIlroy Citation2012a).

The Victorian Inquiry into the Handling of Child Abuse by Religious and other Non-government Organisations was also announced in April 2012. In September 2012, McIlroy described how a “dark history of abuse, torture, rape and shattered lives across the Ballarat region has been revealed by a group submission to the Victorian inquiry into clergy sexual abuse” (McIlroy Citation2012b). Reporting the testimonies of survivors and their families at the public hearings for the Victorian inquiry, held from October 2012 to June 2013, served as a further form of revelation. In a front-page precis McIlroy spoke directly to survivors, and families of those who had died by suicide, who still lived in Ballarat:

A new page was written into the tragic history of child sexual abuse in Ballarat yesterday as survivors and family members told their stories to a Victorian parliamentary inquiry. For the first time, the inquiry heard stories of courage and survival from those hardest hit by clergy sexual abuse in Ballarat's schools and parishes. Witnesses called for truth to replace silence, for offenders to be held to account for their crimes and for vulnerable victims to be protected. (McIlroy Citation2012c)

Through its reporting The Courier brought into focus, named, and gave discursive form to the sexual abuse of children on a massive scale that had dire and ongoing consequences. It did this by increasing the number and prominence of stories about abuse, and by shifting journalistic focus from law reporting that emphasised the perpetrator, on to the accounts of survivors and victims’ families.

Reckoning: Confronting Ballarat’s Past in the Spotlight of a National Inquiry

In journalism theory, the essential component of witnessing is to take responsibility for physically or historically distant trauma and pain on behalf of the audience (Peters Citation2001; Tait Citation2011). To bear witness, the journalist helps the audience confront the past, which can be understood as a form of community reckoning. Our textual analysis identified that The Courier not only revealed the extent and impacts of historical institutional child sexual abuse in the Ballarat region; it played a key role in working with the community to face up to, or reckon with, its history and continuing impacts of clergy sexual abuse.

As the depth and systemic nature of abuse in the Ballarat diocese was made evident through the Victorian inquiry, The Courier spoke directly to the community through its editorials. These included not only the voices of survivors and families of victims, but also the parishioners and clergy of the Catholic Church, acknowledging the public shame that would be brought about through the focus of inquiry on Ballarat:

Ballarat, which has become the epicentre of identified and alleged abuse of children by members of the Catholic Church, stands to endure more harrowing and confronting stories during the inquiry. While we remain absolutely determined to see that justice be done there is also a sense that our city and the church itself is continually damaged by the endless fallout from these despicable acts. (The Courier Citation2012a)

The people of Ballarat are about to face, arguably, one of the toughest periods in our history. Over the next three weeks, the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual abuse will sit at the Ballarat law courts. Paedophile priests and their victims will be required to provide insight into heinous offending which took place at local institutions. (The Courier Citation2015a)

The impact of the hearings on Ballarat will be huge – not just for survivors of abuse and their families and friends, not just for parishioners and Catholics, but for the entire community. There is simply no way to face the horrors that are a part of our city's history without feeling, at the very least, a sense of deep sadness. Also common may be feelings of anger, anxiety and disbelief. (The Courier Citation2015b)

If we as a community were once all somewhat to blame for not listening, not treating it seriously enough or not having the courage to act, then we too stand indited by this suffering. If priests claim they did not know, how many other community leaders, police officers, doctors, teachers, parishioners and parents had heard the rumours and dismissed them out of hand? This is not collective guilt but collective responsibility to make a better future. Ballarat has crossed the line. (The Courier Citation2017b)

Walking with Community in Recovery

Close analysis of The Courier news reports and editorials show that as the Royal Commission proceeded, it engaged closely with the community on the process of recovery. In particular, The Courier supported the Loud Fence movement in its mission to raise awareness and support victims and survivors by tying ribbons on the fences of local buildings where abuse has taken place. In doing so, Loud Fence gives victims and survivors a voice, creates awareness in the community of institutional child sexual abuse, and functions as a unifying act for the Ballarat community (Loud Fence Citation2021; McPhillips Citation2021; Wilson and Golding Citation2018). Courier journalists did not insert themselves directly into the story by documenting themselves tying ribbons to fences, but through its news and editorial coverage the paper was overt in its support. Editorials praised the initiative and expounded on its purpose and goals; they urged prominent Church figures to take part; and the newspaper had photographers on hand to provide the visual evidence. A February 2016 editorial captured the newspaper’s framing of Loud Fence as an act of community recovery when it said:

Loud Fence is getting louder … One of the darkest legacies of these crimes was to drive its victims out into a wilderness of guilt and self-destruction. But this gesture [tying ribbons to a fence] says in the simplest of ways the community recognises the wrong and is with you now. It is inclusive because it embraces not just victims but all those who have the courage to face the past and say this cannot happen again … Now Ballarat is also leading the way in how to move forward from all this wreckage. (The Courier Citation2016a)

Once outsiders, “lepers” tainted by despicable crimes are now seen if not as heroes, then heroic in their stoic perseverance for the truth. In the May 2015 hearings, almost no one would speak on radio for fear of being associated with the dark subject and now the Mayor proudly farewells the survivors at an official event and the Deputy Mayor goes on national TV to say how proud she is to have known these courageous men. (The Courier Citation2016b)

Unless you’re a regular churchgoer, you might not realise, clergy often voice support for survivors during a homily at a mass. But this goes further to break down the mentality of “us and them.” It shows the wider community outside the church that clergy are supporting survivors. (Cunningham Citation2016)

Loud Fence was a uniquely Ballarat inspired movement. It may have grown out of a dark past but it represented its best elements, courage, honesty and community support. The Courier has been proud to applaud this movement as it grew from the idea of a few passionate individuals, flourished with the energy of collective empathy over the scalding months of the hearings and transformed a city with its colourful ribbons. (The Courier Citation2017a)

Discussion and Conclusions

Proximal media witnessing has provided a useful conceptual framework for understanding how local journalism can serve a community in coming to terms with agonising truths and catastrophic failures. It encompasses not only geographical and psychological closeness but also historical, social and cultural nearness that local news can leverage to invite community acknowledgement and action on suffering in its midst. Through the textual analysis presented here we identified five aspects of local journalism practice that allowed proximal witnessing to occur in this case: a commitment to reporting the issue over a sustained period; investing significant resources in the production of original news stories; taking ownership of the story through editorials; involvement in grass-roots community campaigns; and amplifying the voices of marginalised or victimised community members in the face of powerful local institutions.

A central tenet of media witnessing is the commitment to take responsibility for recording and providing testimony of traumatic events on behalf of the audience. At the broadest level, The Courier took responsibility for bringing the national and global story of institutional child sexual abuse to its local readers (Chouliaraki Citation2010). By identifying the volume of news items and the key topics covered, we traced how the issue of child sexual abuse emerged and evolved through the pages of Ballarat’s local newspaper. We have argued elsewhere that journalism was historically one of the institutions complicit in the denial of the institutional nature of child sexual abuse (McCallum and Waller Citation2021; see also Wright, Swain, and McPhillips Citation2017; Mitchell Citation2020). The lack of coverage of the issues in The Courier prior to 2011 supports the contention that local journalism was part of the media system that silenced survivors globally. However, our analysis provides evidence that over the period of study The Courier broke the silence on child sexual abuse for the Ballarat audience by reporting previously untold stories, committing to a sustained focus on survivors and, and maintaining an “everyday” engagement with the wider community on the issue. For generations of Ballarat citizens to come, and for Australians more broadly, the 1267 articles we have identified offer a lasting record of coverage.

The Courier invested significant resources at a time of extreme pressure in the news industry to produce local journalism about child sexual abuse in Ballarat. Importantly, the analysis found more than 70 per cent of the coverage was generated in-house, and that the volume of coverage was sustained over time. The Courier’s editors consciously backed its reporters to expose the scale of abuse and amplified the institutional crimes and cover-ups that were made public through the Royal Commission. We identify this localised and “everyday” commitment to the issue as one of the key features of “proximal witnessing” (Ong Citation2015).

Chouliaraki (Citation2013b, 271) says journalism’s witnessing can facilitate a process of turning evidence of human suffering into ethical discourse and media practice. We argue that the earlier step of naming and making public the phenomenon being witnessed, or revelation, is a crucial initial phase of the witnessing process. The Courier’s revelatory reporting bore witness to the unfolding phenomenon of institutional child sexual abuse and played an important role in advancing the agenda that led to the establishment of both the Victorian and national inquiries.

Local media attention was a central part of the city’s reckoning with its past. While The Courier reported on a wide range of institutional failures addressed by the Child Abuse Royal Commission, its focus was on two of the most high-profile investigations, Case Studies 28 and 35, that pertained to clergy sexual abuse in the Ballarat Catholic diocese. These cases were also of intense interest to the Australian audience, dominating national coverage of the Royal Commission and receiving global attention (see Waller, Dreher, and Hess Citation2020). To the Ballarat community, these stories of national import had a painful proximity. The Courier’s editorials were used strategically to address the community about the process of reckoning with its past and the ongoing trauma of child sexual abuse. In doing so, the local paper helped enable its audience to acknowledge, confront and rectify past injustices (Tait Citation2011). By bearing witness at the local level, the Ballarat community was ultimately able to advance the objectives of the Child Abuse Royal Commission to ensure the prevention of future crimes against children.

Zelizer contends that media witnessing can help individuals “ … move on from the trauma, and help the collective unify” (Citation2002, 698). While we do not agree that a community can remain unchanged in the face of such revelations, or leave the legacies of historical institutional abuses behind, we find that The Courier was a key actor helping the Ballarat community collectively work through its trauma. This is particularly evident through its editorials and its support of the Loud Fence movement that sustained attention on historical institutional abuse and its contemporary manifestations. The ribbons tied on the fences of local institutions where crimes were perpetrated act as a material reminder of Ballarat’s past and its process of healing (Deas, McCallum, and Martin Citation2023).

We conclude The Courier was able to maintain its relevance and establish a change agenda for the local community that has been irreversibly changed through its reckoning with its past. We do not suggest that The Courier reported evenly on the past trauma of all survivors, or that all voices and experiences were heard (Golding Citation2018); or that many Ballarat people are not still living with the traumatic consequences of past events. However, our analysis of The Courier’s reporting showed that by witnessing proximally it helped the community reconnect with ordinary life. Survivor voices and stories were amplified, but Courier editorials were typically constructed to include Catholic institutions as part of the community, and its news stories highlighted the acts of individual priests and clergy in the process of reckoning and recovery. That The Courier did not publicly name itself as a key institution that hid institutional clergy sexual abuse in earlier times speaks to journalism’s limitation to reckon with its own responsibilities and histories (Hess and McCallum, Citation2022). But during that time of intense focus on Ballarat, the paper travelled with the community as they “worked through trauma together” (Zelizer Citation2002, 698).

Our study of The Courier’s coverage of institutional child sexual abuse informs wider scholarly debates about the role of local journalism in society (Callison and Young Citation2020). The crisis in journalism is potently felt though resourcing and staffing cuts in regional newsrooms, combined with increased expectations to produce more content across a hybrid media environment. Despite the deep economic and industrial challenges faced by local newspapers, The Courier invested in working through a major and ethically profound issue with its local audience (McCallum and Waller Citation2021). Through its reporting, The Courier was a proximal media witness to the impacts of institutional child sexual abuse on survivors, victims, their families and the city of Ballarat. Proximal witnessing, as explicated here, demonstrates the capacity for local journalism to marshal its resources to prioritise critical issues to produce a local journalism that is deeply embedded and invested in the community on which it reports. The Courier’s sustained and embedded reporting stands up as a model for best practice local journalism as it reckons with its relevance in a time of severe disruption. We have identified that the sustained commitment to uncovering local suffering and producing journalism that works with the community to recover is an important, but under-examined aspect of local journalism studies. It is in this “proximal” aspect of witnessing that local journalism can carry out some of its most meaningful work.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This research was conducted as part of the Breaking Silences project funded by the Australian Research Council (DP1901011282).

2 Victorian Inquiry into the Handling of Child Abuse by Religious and other Non-Government Organisations (2012–2013).

3 Articles were identified using a comprehensive search string: (“sex abuse” OR “sexual abuse” OR “child abuse” OR “indecent assault” OR “gross indecency”) AND (church OR school OR Catholic OR clergy OR “Christian Brothers” OR “Royal Commission” OR inquiry OR institution OR religious OR “non-government organisation” OR “Loud Fence”).

References

- Abernathy, P. M. 2016. The Rise of a New Media Baron and the Emerging Threat of News Deserts. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

- ACCC (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission). 2019. Digital Platforms Inquiry - Final Report. 26 July 2019. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. Accessed 19 August 2021. https://www.accc.gov.au/publications/digital-platforms-inquiry-final-report.

- Andén-Papadopoulos, K. 2014. “Citizen Camera-Witnessing: Embodied Political Dissent in the age of ‘Mediated Mass Self-Communication’.” New Media & Society 16 (5): 753–769. doi:10.1177/1461444813489863.

- Anderson, C. W. 2020. “Local Journalism in the United States: Its Publics, its Problems, and its Potentials.” In The Routledge Companion to Local Media and Journalism, edited by A. Gulyas, and D. Baines, 141–148. London: Routledge.

- Blatchford, A. 2020. “Searching for Online News Content: The Challenges and Decisions.” Communication Research and Practice 6 (2): 143–156. doi:10.1080/22041451.2019.1676864.

- Callison, C., and M. L. Young. 2020. Reckoning: Journalism's Limits and Possibilities. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Chouliaraki, L. 2010. “Ordinary Witnessing in Post-Television News: Towards a new Moral Imagination.” Critical Discourse Studies 7 (4): 305–319. doi:10.1080/17405904.2010.511839.

- Chouliaraki, L. 2013a. The Ironic Spectator: Solidarity in the Age of Post-Humanitarianism. Cambridge: Polity.

- Chouliaraki, L. 2013b. “Re-mediation, Inter-Mediation, Trans-Mediation.” Journalism Studies 14 (2): 267–283. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2012.718559.

- Cunningham, M. 2016. “Priest Shows Support.” The Courier, 8 January, online. Accessed 2 November 2020. https://www.thecourier.com.au/story/3652406/priest-shows-support/.

- Deas, M., K. McCallum, and K. Martin. 2023. “Mediating via Materiality: Continuing Critical Conversations Around Child Sexual Abuse in Australia.” In Difficult Conversations, edited by U. K. Frederick, A. Harrison, T. Ireland, and J. Magee, 19–31. London: British Council. doi:10.57884/6P72-TZ16.

- Dodd, A., and M. Ricketson. 2021. Upheaval: Disrupted Lives in Journalism. Sydney: NewSouth Books.

- Fisher, C., D. Nolan, and K. McGuinness. 2022. “Australian Regional Journalists’ Role Perceptions at a Time of Upheaval.” Media International Australia [Online First], doi:10.1177/1329878X221087726.

- Florea, S., and J. Woelfel. 2022. “Proximal Versus Distant Suffering in TV News Discourses on COVID-19 Pandemic.” Text & Talk 42 (3): 327–345. doi:10.1515/text-2020-0083.

- Franklin, B. 2014. “The Future of Journalism: In an age of Digital Media and Economic Uncertainty.” Journalism Practice 8 (5): 469–487. doi:10.1080/17512786.2014.942090.

- Frosh, P., and A. Pinchevski. 2009. Media Witnessing: Testimony in the Age of Mass Communication. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Frosh, P., and A. Pinchevski. 2014. “Media Witnessing and the Ripeness of Time.” Cultural Studies 28 (4): 594–610. doi:10.1080/09502386.2014.891304.

- Golding, F. 2018. “Sexual Abuse as the Core Transgression of Childhood Innocence: Unintended Consequences for Care Leavers.” Journal of Australian Studies 42 (2): 191–203. doi:10.1080/14443058.2018.1445121.

- Gulyas, A., and D. Baines. 2020. “Introduction: Demarcating the Field of Local Media and Journalism.” In The Routledge Companion to Local Media and Journalism, edited by A. Gulyas, and D. Baines, 1–22. London: Routledge.

- Gutsche, J. R. E., and K. Hess. 2020. “Placeification: The Transformation of Digital News Spaces Into “Places” of Meaning.” Digital Journalism 8 (5): 586–595. doi:10.1080/21670811.2020.1737557.

- Henderson, F. 2015a. “Victims of Paedophile Priest Gerald Ridsdale Walked out.” The Courier, 28 May, 5.

- Henderson, F. 2015b. “Loud Fence March to Show Support for Abuse Survivors.” The Courier, 28 May, online. Accessed 2 November, 2020. https://www.thecourier.com.au/story/3111670/loud-fence-march-to-show-support-for-abuse-survivors/.

- Hess, K., and K. McCallum. 2022. “Reflecting on a Painful Past.” Media History 1–16. doi:10.1080/13688804.2022.2092463.

- Hess, K., K. McCallum, L. Waller, and A. Myers. 2021. “Local Journalism and the Ethics of Inquiry.” Ethical Space: The International Journal of Communication Ethics 18 (3/4).

- Hess, K., and L. Waller. 2012. “The Snowtown we Know and Love: Small Newspapers and Heinous Crimes.” Rural Society Journal 21 (12): 116–125. doi:10.5172/rsj.2012.21.2.116.

- Hess, K., and L. Waller. 2017. Local Journalism in a Digital World: Theory and Practice in the Digital Age. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hess, K., and L. Waller. 2020. “Moral Compass: How a Small-Town Newspaper Used Silence in a Hyper-Charged Controversy.” Journalism 21 (4): 574–590. doi:10.1177/1464884919886441.

- Hill, D. W. 2019. “Bearing Witness, Moral Responsibility and Distant Suffering.” Theory, Culture & Society 36 (1): 27–45. doi:10.1177/0263276418776366.

- Kitzinger, J. 2004. Framing Abuse: Media Influence and Public Understanding of Sexual Violence Against Children. London: Pluto Press.

- Le, E. 2010. Editorials and the Power of Media: Interweaving of Socio-Cultural Identities. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Loud Fence. 2021. About Loud Fence.” Accessed 19 August 2021. https://www.facebook.com/loudfence/about/.

- Marr, D. 2013. “The Prince: Faith, Abuse and George Pell.” Quarterly Essay 51: 1–98.

- McCallum, K., and L. Waller. 2020. “Un-braiding Deficit Discourse in Indigenous Education News 2008–2018: Performance, Attendance and Mobility.” Critical Discourse Studies, 1–20. doi:10.1080/17405904.2020.1817115.

- McCallum, K., and L. Waller. 2021. “Truth, Reconciliation and Global Ethics.” In Handbook of Global Media Ethics, edited by S. Ward, 783–801. Switzerland: Springer.

- McClellan, P. 2016. “Chair of the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse announcement [speech].” https://www.childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au/speeches/announcement-chair-royal-commission.

- McCombs, M. 1997. “Building Consensus: The News Media's Agenda-Setting Roles.” Political Communication 14 (4): 433–443. doi:10.1080/105846097199236.

- McIlroy, T. 2012a. “Suicides Linked to Clergy Sexual Abuse.” The Courier, 13 April, online. Accessed 2 November, 2020. https://www.thecourier.com.au/story/63383/suicides-linked-to-catholic-clergy-abuse/.

- McIlroy, T. 2012b. “A Dark History of Abuse.” The Courier, 22 September, 5.

- McIlroy, T. 2012c. “A New Page Was Written.” The Courier, 8 December, 1.

- McIlroy, T. 2012d. “Quietly and Without any Official Acknowledgement.” The Courier 8 December: 4.

- McNair, B. 2018. An Introduction to Political Communication. 6th ed. London: Routledge.

- McPhillips, K. 2021. “Mobilising for Justice: The Contribution of Organised Survivor Groups in Australia to Addressing Sexual Violence Against Children in Christian Churches.” Journal for the Academic Study of Religion 34 (1): 3–28.

- Mitchell, M. 2020. “The Discursive Production of Public Inquiries: The Case of Australia’s Royal Commission Into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse.” Crime, Media, Culture, 1–22. doi:10.1177/1741659020953451.

- Muller, D. 2017. “Critical Mass: How Journalism got Australia the Child Abuse Royal Commission.” Meanjin 76 (2): 116–127.

- Nielsen, R. K. 2015a. “Introduction: The Uncertain Future of Local Journalism.” In Local Journalism: The Decline of Newspapers and the Rise of Digital Media, edited by R. K. Nielsen, 1–29. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Nielsen, R. K. 2015b. “Local Newspapers as Keystone Media: The Increased Importance of Diminished Newspapers for Local Political Environments.” In Local Journalism: The Decline of Newspapers and the Rise of Digital Media, edited by R. K. Nielsen, 51–72. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Olsen, R. K. 2021. “The Value of Local News in the Digital Realm – Introducing the Integrated Value Creation Model.” Digital Journalism, 1–22. doi:10.1080/21670811.2021.1973905.

- Ong, J. 2015. “Witnessing Distant and Proximal Suffering Within a Zone of Danger: Lay Moralities of Media Audiences in the Philippines.” International Communication Gazette 77 (7): 607–621. doi:10.1177/1748048515601555.

- Peters, J. D. 2001. “Witnessing.” Media, Culture & Society 23 (6): 707–723. doi:10.1177/016344301023006002.

- Picard, R. G. 2010. Value Creation and the Future of News Organizations: Why and How Journalism Must Change to Remain Relevant in the Twenty-First Century. Lisbon: Media XXI.

- Powell, F., and M. Scanlon. 2015. Dark Secrets of Childhood: Media Power, Child Abuse and Public Scandals. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Tait, S. 2011. “Bearing Witness, Journalism and Moral Responsibility.” Media, Culture & Society 33 (8): 1220–1235. doi:10.1177/0163443711422460.

- The Courier. 2012a. “The State Government's Announcement of a Parliamentary Inquiry.” 18 April, 17.

- The Courier. 2012b. “The Announcement by Prime Minister Julia Gillard of a Royal Commission.” 13 November, 15.

- The Courier. 2015a. “Public Hearings to Shine a Light on Ballarat's Sordid History.” 18 May, 13.

- The Courier. 2015b. “Difficult Week for Ballarat as Horrific Stories of Abuse Emerge.” 21 May, 11.

- The Courier. 2016a. “The Power of a Message of Community Hope.” 1 February, online. Accessed 2 November 2020. https://www.thecourier.com.au/story/3700149/the-power-of-a-message-of-community-hope/.

- The Courier. 2016b. “Proud Moments Born of Dark Past Days.” 3 March 2016, online. Accessed 2 November 2020. https://www.thecourier.com.au/story/3767772/proud-moments-born-of-dark-past-days/.

- The Courier. 2017a. “Keeping a Harsh Message Alive for the Future Generations.” 5 December, 15.

- The Courier. 2017b. “A Turning Point If We Can Grasp the Lessons of the Royal Commission.” 7 December, 13.

- Usher, N. 2019. “Putting “Place” in the Center of Journalism Research: A way Forward to Understand Challenges to Trust and Knowledge in News.” Journalism & Communication Monographs 21 (2): 84–146. doi:10.1177/1522637919848362.

- Van Dijk, T. 1988. News as Discourse. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Wadbring, I., and A. Bergström. 2017. “A Print Crisis or a Local Crisis? Local News Use Over Three Decades.” Journalism Studies 18 (2): 175–190. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2015.1042988.

- Waller, L., T. Dreher, K. Hess, et al. 2020. “Media Hierarchies of Attention: News Values and Australia’s Royal Commission Into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse.” Journalism Studies 21 (2): 180–196. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2019.1633244.

- Wilson, J. Z., and F. Golding. 2018. “The Tacit Semantics of ‘Loud Fences’: Tracing the Connections Between Activism, Heritage and New Histories.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 24 (8): 861–873. doi:10.1080/13527258.2017.1325767.

- Wright, K., and S. Swain. 2018. “Speaking the Unspeakable, Naming the Unnameable: The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse.” Journal of Australian Studies 42 (2): 139–152. doi:10.1080/14443058.2018.1467725.

- Wright, K., S. Swain, and K. McPhillips. 2017. “The Australian Royal Commission Into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse.” Child Abuse & Neglect 74: 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.09.031.

- Yamamoto, M. 2011. “Community Newspaper use Promotes Social Cohesion.” Newspaper Research Journal 32 (1): 19–33. doi:10.1177/073953291103200103.

- Zelizer, B. 2002. “Finding Aids to the Past: Bearing Personal Witness to Traumatic Public Events.” Media, Culture & Society 24 (5): 697–714. doi:10.1177/016344370202400509.