ABSTRACT

Although it is generally acknowledged that the raison d'être for public service media (PSM) is to serve the public, there is much less agreement about what the term specifically means. This contribution, using a recent newsroom conflict at the Slovak public service broadcaster Radio and Television of Slovakia (RTVS) as a case study, explores how PSM journalists and managers perceive and interpret the essence of public service in PSM, how their interpretations differ from the academic and legal framework, how diverse the understanding of public service can be within one newsroom, and what consequences this variability can have for the functioning of that newsroom. It shows that the RTVS journalists’ and managers’ shared perception of PSM is closer to the market-failure perspective than to a more comprehensive democracy-centric perspective (Donders Citation2021). They construct PSM mainly as an antithesis to commercial media and see its value in the production of niche programmes and genres that are important, although not popular. Although they agreed in many aspects as to what public service obtains, the differences in the notion of objectivity and proper power distance were enough to cause permanent newsroom clashes and struggles, and eventually contributed to a significant staff turnover.

Introduction

Public service, which is the foundation for public service media (PSM), is a concept that is used (and occasionally abused) by various stakeholders to assess, praise, or criticise the functioning of PSM and to legitimise or delegitimise its very existence. Although it is extensively discussed and examined by media scholars (e.g., Donders Citation2012; Donders Citation2021; Moe and Syvertsen Citation2009; Murdock Citation2005; Scannel Citation1990), much less is known about how the concept is understood and articulated by the key actors whose everyday jobs are to put it in practice: namely, the actual journalists and the managers of public service media organisations.

This contribution uses a newsroom conflict at the Slovak public service broadcaster Radio and Television of Slovakia (RTVS) in 2018 as a case study. Through 16 semi-structured interviews with journalists and managers from the RTVS newsroom it explores how they perceived and interpreted the concept of public service, how their interpretations differed from the academic and legal framework, how diverse its understanding was within one newsroom, and what the consequences of this variability had on the functioning of the PSM. The newsroom conflict started after the election of a new Director General in summer 2017 and culminated in a wave of protest resignations and layoffs in 2018 (see Urbániková Citation2021 for details). Differing views on the nature of public service and how best to fulfil it were identified by the actors of the conflict as one of the major sources for the upheaval.

The contribution of this paper is twofold. First, it examines the concept of public service from a rarely applied perspective. Typically, the scholarship on PSM takes a normative stance and focuses on what public service and PSM could or should mean in a democratic society and what its mission should be (e.g., Donders Citation2012; Donders Citation2021; Murdock Citation2005). Or, it takes an institutional and policy perspective to focus on how PSMs behave as institutions (e.g., Larsen Citation2014; Moe and Syvertsen Citation2007) and how, and with what effect, they are regulated (e.g., Hanretty Citation2011; Nowak Citation2014). This study adds to the scarce literature on how the ideal of public service is constructed and interpreted by the key stakeholders. The research so far concentrated on the audiences (Just, Büchi, and Latzer Citation2017; Lamuedra, Martín, and Broullón-Lozano Citation2019; Lamuedra Graván, Mateos, and Broullón-Lozano Citation2020; Reiter et al. Citation2018) and PSM managers (Larsen Citation2010; Larsen Citation2014; Lowe and Maijanen Citation2019; Maijanen Citation2015). This article explores how the concepts of public service and public service mission are perceived and interpreted by journalists and managers who work for a PSM organisation. Since they are the ones who put the concepts into practice in their daily work, their perspective is particularly important because it can inform their professional performance and subsequently the content they create, which in turn shapes the overall performance of PSM. Besides, who else but PSM journalists and managers should have a clear idea of the essence and value of PSM such that they can explain it convincingly to the public? Moreover, the paper shows how inherently different the understanding of public service and the idea of its fulfilment in practice can be within a single media organisation, and it demonstrates how damaging the consequences of disagreement can be for a PSM organisation.

Second, this paper contributes to the under-researched area of PSMs in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). The literature on PSMs predominantly focuses on Western Europe and only recently has started to look more intensely at other regions, including CEE (e.g., Jusić et al. Citation2021; Milosavljević and Poler Citation2018; Połońska and Beckett Citation2019), with attention mostly paid to the cases in Hungary (Bajomi-Lazar Citation2017; Polyák Citation2015) and Poland (Chapman Citation2017; Węglińska Citation2021).

Public Service Media and Public Service in Journalism

Public Service Media Mission

The provision of a public service is the sole purpose of public service media. Not only is it part of the actual name, but the public service remit is explicitly defined in legal acts that govern PSM, and its fulfilment is regularly assessed and evaluated. What, then, are the fundamental principles and core values of PSM? In addition to the legal perspective, there is an academic perspective and perspectives of the audience, PSM managers, and journalists.

To the Reithian triad of “informing, educating and entertaining”, UNESCO (Citation2005) added additional roles and functions: providing access to participation in public life; promoting access to culture; fostering interactions among citizens; serving the interest of people as citizens rather than as consumers; contributing to social inclusion; and the strengthening of civil society. The European Broadcasting Union, an alliance of PSM organisations that represents the managerial perspective, set out six core values for PSM: universality, independence, excellence, diversity, accountability, and innovation (EBU Citation2014). Other elements frequently mentioned in the academic literature include the provision of plural and quality information; the provision of open access to information and the actions of power holders; the provision of interpretations and explanations; the cultivation of an informed and enlightened democracy; the support of domestic culture and cultural cohesion (Lamuedra, Martín, and Broullón-Lozano Citation2019; Lowe and Maijanen Citation2019; Murdock Citation2005; Scannel Citation1990).

On a more conceptual level, according to Schweizer and Puppis (Citation2018), media laws and decrees typically include three elements of PSM remits: genres; goals and functions; and the characteristics of journalistic practice. Even more broadly, Donders (Citation2021) recognises two models or perspectives on PSM: a market failure and a democracy-centric perspective. According to the market failure view, PSM should provide only the services that commercial media companies do not sufficiently deliver (e.g., domestic children's content, documentaries, local news, investigative journalism), and thus limit its scope to niche services. The democracy-centric perspective assumes that PSM is at the core of democracy and is a valuable asset to society that contributes to the realisation of a public sphere that is accessible to all. From this perspective, PSM should not limit its services to those not readily available on the market. Rather it should, regardless of profit, provide citizens with equal access to high-quality information, education, and entertainment. While the market-failure perspective can be linked to the perception of broadcasting as a public good that should be provided as long as audiences consume it, the democracy-centric perspective is such that broadcasting is a merit good that should be provided regardless of consumption patterns (Ali Citation2016; Donders Citation2012).

Although much has been written about how the PSM mission is understood by media theorists and set out in legal acts and documents issued by international organisations, surprisingly little is known about how the idea of public service is perceived and interpreted by the key stakeholders — namely, the PSM staff (journalists and managers) who are responsible for putting this idea in practice, and the public whose interest PSM should fulfil. Regarding the public's perspective, studies from Switzerland (Just, Büchi, and Latzer Citation2017), Austria (Reiter et al. Citation2018), and Spain (Lamuedra, Martín, and Broullón-Lozano Citation2019; Lamuedra Graván, Mateos, and Broullón-Lozano Citation2020) show that people appreciate the PSM concept and consider it highly important but they are not satisfied with how the national PSM actually fulfil the public service remit. When it comes to audience expectations, citizens adhere to the traditional values of independence, professionalism, and the provision of accurate and unbiased information (Campos-Rueda and Goyanes Citation2022). In terms of performance attributes, a study from Germany and the United Kingdom suggests that citizens prefer a combination of a small license fee and advertisements in exchange for balanced programming with a noteworthy share of entertainment content (Lis, Nienstedt, and Günster Citation2017).

Several studies (Larsen Citation2010; Larsen Citation2014; Lowe and Maijanen Citation2019; Maijanen Citation2015) focused on how the public service mission is defined by the PSM managers and how they legitimise the PSM position. The results showed that the views of PSM managers in Finland, Germany, Norway, and Sweden are, to a large extent, coherent with the usual legal and theoretical perspectives on PSM: they see the public service mission in developing and defending democracy; providing independent information; providing relevant content for all; ensuring high journalistic standards; defending and creating national culture; and sustaining national language and identity (Larsen Citation2010; Larsen Citation2014; Lowe and Maijanen Citation2019; Maijanen Citation2015).

Interestingly, almost no research attention has been paid to the perspectives of PSM journalists. A rare exception is a questionnaire survey study by Ibarra and Nord (Citation2013), which shows that PSM journalists in Sweden and Spain share similar journalistic values and newsroom practices with their counterparts in commercial media, but they are more critical and concerned by increasing commercialisation and the decreasing quality of journalism. To fill this gap, using RTVS as an example, this study will focus on how journalists and managers understand and interpret the PSM mission.

“Public Service” in Journalism and Public Service Journalism

The provision of public service is not only the mission of PSM. It is also one of the basic normative expectations of journalism, irrespective of whether it is practiced in PSM or commercial media. Public service is one of the core ideal-typical values of journalism's ideology (Deuze Citation2005; Kovach and Rosenstiel Citation2001). As Deuze (Citation2005, 447) puts it, “journalists share a sense of ‘doing it for the public’, of working as some kind of representative watchdog of the status quo in the name of people”. An orientation toward public service (i.e., the belief that journalism's function in society is to provide public service and produce the news in the public interest) versus market orientation is one of the key cleavages that indicates a different role orientation and, in a broader sense, journalistic cultures (Hanitzsch Citation2007). In this respect, empirical research mostly quantitatively examines how journalists perceive their professional role and to what extent they see their audiences as citizens (i.e., public service orientation) or consumers (i.e., market orientation) (Hanitzsch Citation2011; Hanitzsch et al. Citation2019).

A different but related stream of literature explores how journalists (Hujanen Citation2009; Jenkins and Nielsen Citation2020) and citizens (van der Wurff and Schoenbach Citation2014) construct quality journalism (Lacy and Rosenstiel Citation2015), and to what extent journalists’ perception of quality journalism align with the views of the public (Gil de Zúñiga and Hinsley Citation2013; Loosen, Reimer, and Hölig Citation2020; Riedl and Eberl Citation2022; Tsfati, Meyers, and Peri Citation2006; Vos, Eichholz, and Karaliova Citation2019). On a conceptual level, quality can be understood as a prerequisite for journalism to properly fulfil its public service role. Also, the quality of services and output is an often-cited principle of PSM (Born and Prosser Citation2001), and this inherently applies to journalism. In short, public service journalism (i.e., journalism in PSM) should be quality journalism.

So what are the foundations of quality journalism? When confronting journalism theorists, practitioners, and public views (Deuze Citation2005; Hanitzsch Citation2011; Hujanen Citation2009; Jenkins and Nielsen Citation2020; Kovach and Rosenstiel Citation2001; Lacy and Rosenstiel Citation2015; Loosen, Reimer, and Hölig Citation2020; Riedl and Eberl Citation2022; Tsfati, Meyers, and Peri Citation2006; van der Wurff and Schoenbach Citation2014; Vos, Eichholz, and Karaliova Citation2019), several common values and traits appear. Journalists expect (and are expected) to be the watchdogs, hold the powerful to account, be objective, be neutral, be impartial, be fair, and report different views and perspectives as completely as possible. They should disseminate important information in a timely manner, provide the audience with analysis and interpretation of the news, empower citizens to develop their own opinions, and motivate them to participate in public life. Transparency, independence, and the verification of facts also belong to frequently mentioned principles.

A particularly contentious aspect of quality journalism is objectivity (with the related concepts of balance, impartiality, neutrality, and fairness). This principle is even more important for PSM journalism. PSM are publicly funded and tasked with delivering a public service, so the requirement that their journalism be impartial and not favour or disadvantage any person, group, or opinion, is even more stringent. Similar provisions tend to be explicitly set out in PSM laws and statutes: for instance, Article 3(3) letter (b) of the RTVS Act provides that the RTVS programme should “provide impartial, verified, unbiased, up-to-date, comprehensible and in its entirety balanced and pluralistic information on events in the Slovak Republic and abroad for the free formation of opinions”.

Objectivity is a value that is notoriously difficult to define and operationalise. Its frequently mentioned elements are the separation of facts from opinions; the presentation of an emotionally detached view of the news; fairness; and balance, which involves giving voice to both sides in a conflict (DeFleur and Dennis Citation1991). A more specific operationalisation is offered by Skovsgaard et al. (Citation2013), who build on Donsbach and Klett (Citation1993). They accentuate four aspects of objectivity: a) no subjectivity (i.e., journalists should be detached observers); b) balance; c) hard facts (i.e., accuracy, factuality); and d) value judgments (i.e., journalists should not merely describe reality but they should make the better position clear).

In their seminal work, Kovach and Rosenstiel (Citation2001, 72) argue that objectivity should be understood as “a consistent method of testing information” and “a transparent approach to evidence” with the goal of preventing journalistic work from being distorted by bias. They also point out that objectivity does not mean the absence of a point of view and that balancing multiple points of view should never be a goal unto itself. In addition, they warn that the original notion of objectivity was replaced by balance and the tendency to measure the time and space devoted to each side, which can lead to distortion. In short, the pursuit of objectivity should not lead to “false balance” (Brüggemann and Engesser Citation2017). This would not only reduce the quality of journalism, but, in the case of PSM, it would mean that such journalism would not fulfil its mission.

Public Service Media in Slovakia and the Newsroom Conflict at RTVS

Although independence and autonomy are among the key principles of the functioning of PSM, without which its very purpose is threatened (Murdock Citation2005), PSM in post-communist countries have repeatedly encountered serious shortcomings in this regard. RTVS is no exception. It suffers from several caveats typical for PSM in the CEE region (Milosavljević and Poler Citation2018). In particular, the lack of political independence and insufficient financial resources are two critical challenges for RTVS. Both personnel and financial matters are controlled directly by politicians: the Parliament elects the Director General and together with the Government decide on financial matters.

The low de jure independence of PSM enables politicians to exert their influence if they wish. As the past years have shown, this has not been hypothetical. Throughout its history, RTVS has repeatedly been used as a political tool, most flagrantly under Prime Minister Vladimír Mečiar during his autocratic style of government (1994-98). This was achieved through the dismissals of the Director General and the members of the PSM Council, the appointments of loyal personnel, and subsequent mass dismissals (Gindl Citation1996). The independence of PSM in Slovakia was also widely discussed in 2007 after the appointment of a new Director General, when 15 editors and reporters resigned in protest against alleged interference in favour of the ruling coalition led by the Smer-SD party (Vagovič Citation2007).

The most recent conflict at RTVS began when the Slovak Parliament elected the new Director General of RTVS in June 2017. In April 2018, approximately 60 RTVS journalists signed an open letter to declare their distrust of their superiors and describe the working atmosphere as hostile and tense (“Otvorený list [Open letter]” Citation2018). By summer 2019, approximately two-thirds of the TV reporters and editors had resigned in protest, or their contracts were not prolonged.Footnote1

According to information published in the media, the dissenting reporters and editors objected to several main points (Urbániková Citation2021). First, the selection of the new Director General, both procedurally and personally, raised concerns about the future independence of the Slovak PSM. In a secret ballot, the Slovak Parliament elected Jaroslav Rezník, a person with a questionable professional track record (see, e.g., Transparency International Slovakia Citation2015). He had alleged ties to the then-ruling Slovak National Party, a nationalistic party with a pro-Russian orientation, which significantly helped to push through his nomination.

Second, the managerial decisions of the new Director General amplified the concerns. Soon after he took office, he appointed three former press officers from ministries and state organisations to be top managers directly responsible for the TV and radio newscasts. He disregarded that there could be a conflict of interest. In addition, the new management of RTVS decided to shut down its only investigative programme after it broadcast a story critical of an organisation to which the new Director General had personal ties (see Urbániková Citation2021 for further details).

Third, and most importantly, the public statements of the actors of the conflict (the RTVS journalists and managers) showed that both sides referred to the concept of verejnoprávnosť when formulating their objections to the behaviour of the opposing party. Verejnoprávnosť (noun) is a term that has no simple translation in English; the adjective verejnoprávny is the Slovak equivalent of the German adjective öffentlich-rechtlich, which is used to describe legal entities of public law and can be translated as public or public service. Thus, the English term public service media translates in Slovak as verejnoprávne médiá (similar to the German expression öffentlich-rechtliche Medien). Verejnoprávnosť could then be loosely translated as the spirit and the essence of public service media; in short, it is what makes public service media public service media. Its meaning mainly draws on two theoretical concepts described above: the mission of public service media and, from a more narrow perspective, public service in journalism.

From a legal perspective, the definition of public service media and the specification of its mission is stipulated by Act No. Citation532/Citation2010 Coll., on the Radio and Television of Slovakia (hereinafter “the RTVS Act”). Article 1(3) point (2) of the RTVS Act provides that in the realm of broadcasting, public service means the provision of a programme service, which is:

universal in its geographical coverage, offers a diverse range of programmes, prepared in line with principles of editorial independence by qualified staff with a feeling of social responsibility and which raises the cultural level of its listeners and viewers, provides space for contemporary cultural and artistic activities, presents the cultural values of other nations, and is financed primarily from public funds.

This study asks two research questions: 1. How did the RTVS journalists and managers understand and interpret the concept of public service (verejnoprávnosť), specifically, how did they perceive the PSM mission and PSM journalism? 2. What role did disagreements between RTVS journalists and managers over the concept of public service (verejnoprávnosť) play in the newsroom conflict at RTVS?

Data and Method

This paper explores how the journalists and managers who worked for the Radio and Television of Slovakia (RTVS), the Slovak nationwide public service broadcaster, perceived the essence of public service (verejnoprávnosť) (i.e., how they interpret the PSM mission and public service journalism), and how their interpretations differed from the academic and legal framework. Furthermore, it examines the role that different conceptions played in the newsroom conflict that started after the Parliament elected a new Director General in 2017.

The clash between (some) reporters and editors, on one hand, and the new managers, on the other hand culminated in layoffs and resignations of roughly two-thirds of the TV newsroom by 2019 (Urbániková Citation2021). Although it affected both the radio and TV divisions of RTVS, the paper concentrates solely on the TV newsroom because the confrontation was more intense and led to a higher staff turnover.

As a broader methodological strategy, a case study approach — “an empirical method that investigates a contemporary phenomenon (the ‘case’) in-depth and within its real-world context” (Yin Citation2018, 15) — was used to untangle the roots of the newsroom conflict in RTVS. Initial insight into the case was gained through publicly available information about the conflict (e.g., from media articles and interviews). This was supplemented by two informal interviews with two RTVS reporters who took different stances towards the conflict (i.e., one decided to leave in protest, the other stayed at RTVS), which were conducted in the pre-research phase, and which served for the initial mapping of the situation. Because the organisation chart of the RTVS newsroom and the list of its staff are not publicly available, one of the RTVS reporters provided the author with a list of RTVS reporters and editors (including whether they resigned, were forced to leave, or stayed on); this information was then independently verified by another RTVS reporter.

Based on the pre-research, the key groups of actors with different positions within the RTVS newsroom and/or with different views on the conflict were identified. Purposive sampling was then used to ensure that the participants were recruited from all of the relevant opinion groups, and, where possible, to maximise the diversity of the sample from the viewpoints of gender, age, position, and length of work experience. In total, I conducted 16 semi-structured interviewsFootnote2 with the five key groups of actors: the journalist whose contract were not prolonged by the new management (1 participant); the journalists who resigned in protest (4); the journalists who decided to stay at their jobs (5; although, one of them resigned shortly after the interview); newly appointed managers (4); and members of the previous management, who resigned (2). The years of experience of the 5 female and 11 male participants ranged from 3 years to more than 20. With one exception, none of the addressed participants declined the invitation to participate in the research study.

The pre-research suggested that, in addition to other reasons, different perceptions of public service (verejnoprávnosť) and different ideas about its proper fulfilment in practice by RTVS journalists and managers were among the causes of the conflict. That is why this study focuses on this topic. It is, however, part of a larger project conducted by the author that aimed to explore the roots of the conflict in RTVS and its consequences, the forms and types of perceived interference in journalistic autonomy, and the resistance strategies the journalists used to cope with the perceived interference. Therefore, the interview guide covered two main areas. First, it asked the participants to narrate the course of events from the appointment of the new Director General in July 2017 to the present, describe the course of the conflict, and identify its sources. Second, it included questions about how participants perceived and defined public service in journalism, the PSM mission, and objectivity, and how they believed these concepts were perceived by other actors in the conflict. Specifically, the participants were asked how they perceived the mission of PSM, how they saw the future of PSM, how they would explain to people that they should pay a licence fee, and what journalism in PSM should ideally be like.

The participants were informed in advance about the topic of the study, and their informed consent was obtained.Footnote3 To ensure anonymity in the following text, the names of the participants were changed and their gender was randomly assigned when the pseudonyms were created. The interviews were conducted face-to-face by the author between July 2018 and September 2019. All were recorded, anonymised, transcribed verbatim, and subjected to coding in Atlas.ti. To analyse the data, I used thematic analysis, “a method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) within data” (Braun and Clarke Citation2006, 79). The coding and analysis process followed the analytic procedure suggested by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006): it started with becoming familiar with the data and generating initial codes, continued with searching for themes (i.e., collating the codes in potential themes) and reviewing the themes (i.e., including the creation of a thematic map), and ended with defining and naming themes, and producing the report. For reasons of brevity, in the following text, the term “journalists” is employed to describe the dissenting reporters and editors (who made up the majority of the newsroom).

Results and Findings: Untangling the Concept of Public Service

Before exploring how the journalists and managers working for RTVS understood and interpreted the public service mission of their organisation in general, and public service journalism in particular, the analysis starts with an examination of how different understandings of public service contributed to the conflict.

Different Understandings of Public Service as One of the Sources of the Newsroom Conflict

The interviews with RTVS journalists and managers supported the preliminary finding that was suggested by the pre-research (based on publicly available information about the conflict and supplemented by two initial informal interviews with two different RTVS journalists). Everyday life in the newsroom was affected by profound differences in how the journalists and the new managers understood the public service and the quality journalism that would fulfil the PSM mission. Several participants mentioned that this was at the heart of the conflict:

This was the biggest stumbling block, that two worlds with a completely different notion of objectivity and public service have clashed. This was the central core of all the conflicts. (Interview with an RTVS reporter, February 2019)

I can feel the difference [between public service and commercial media]. It seems quite important to me — some of them [the dissenting journalists] still have no idea — for them [the dissenting journalists] to realise why they are working here and what the difference is. […] And that means that they have to understand […] what the public service medium is and what the public service is in the conception of our broadcasting. (Interview with an RTVS manager, September 2018)

The dispute over what is meant by public service escalated especially after [one of the new managers] came up with the public service issue. He arrived, and at the very first meeting — I saw him for the first time in my life at that moment — he introduced himself as a man who was born with public service [verejnoprávnosť] in his blood and knows what public service [verejnoprávnosť] is. He simply presented himself as the embodiment of public service [verejnoprávnosť] in its material form. And, according to him, public service [verejnoprávnosť] means that contradictory opinions should be presented side by side and given the same space. This means that — and this is a quote — if I find six political scientists who say the same thing, I have to find a seventh who will say something else and give him the same space as the six. (Interview with an RTVS ex-reporter, October 2018)

PSM Mission from the Viewpoint of the RTVS Journalists and Managers: Non-Commercial and Catering to Minority Interests

Several RTVS journalists and managers stated that the dispute over the meaning of public service (verejnoprávnosť) was at the core of the conflict, so it is important to know what the individual actors understood by this term. In order to disentangle the concept, the analysis focuses on two aspects: the perception of the PSM mission, in general, and the perception of public service journalism (in the sense of journalism in PSM), in particular. Interestingly, when asked about their perception of public service and PSM, some of the participants reacted in surprise and labelled the question as “too complicated”, “academic”, or “theoretical”.

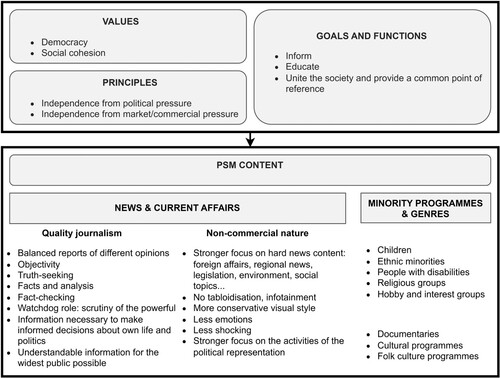

Based on their responses and accounts, a classification scheme of what the actors perceived as the essence of public service in PSM was inductively developed (). In their explanations, four elements of the PSM remit could be traced: values (i.e., the key ideals to be promoted and developed by the PSM); principles (i.e., fundamental rules of its operation); goals and functions (i.e., the aims and purposes that the PSM should pursue and deliver); and the characteristics of the PSM content (i.e., news, current affairs, other programmes). The perception of the values and principles on which PSM stands and which it should promote determines how the participants understand its the goals and functions, and all of these translate to how they envisage the desirable characteristics of the PSM content.

In general, the RTVS journalists and managers largely agreed on the essence of public service in PSM and mentioned similar concepts and elements when describing it (although they did not always agree on their interpretations). There was almost universal agreement on independence from market pressure as the key principle of PSM, together with a strong focus on hard news content (i.e., information citizens need to make informed decisions) and the production of programmes and genres for minority viewers. On the contrary, none of the participants mentioned high-quality entertainment, sports, or innovation. The rest of this section describes the four elements of PSM as seen by the participants and analyses the differences between the two sides of the conflict in their understanding of public service.

The first aspect, the values behind the PSM concept, was surprisingly rarely discussed by the RTVS journalists and managers. When sharing their perspective on PSM, very few of them pointed out that PSM is essential for democracy and contributes to social cohesion. Much more attention was paid to the second element, the organising principles of PSM. Almost all the participants mentioned independence as the essential characteristic of PSM; however, they focused primarily on independence from market pressure while independence from political pressure was much less often discussed.

The biggest advantage of public service broadcasting is that it is paid by licence fees, that it is not dependent on any sponsorship gifts, it is not dependent on any owner who may have some economic interests. […] This is probably the biggest advantage - that we don't have to look at the circulation figures or rating figures. (Interview with an RTVS reporter, February 2019)

It [PSM] aims to educate society and encourage the better side of people. For example, in our broadcast about the migration crisis, we firmly stood up for migrants and showed solidarity, despite the protests of a large part of the public, and said that we should simply show these people basic human emotions, such as solidarity and belonging. (Interview with an RTVS reporter, September 2018)

I see it as a great advantage of public service media that other television [channels] do not have, that we cater to minority audiences. […] Private, commercial media will simply never cover the interests of minority viewers. That's why I think that public service media should exist. (Interview with an RTVS reporter, February 2019)

Contested Issues in the Understanding of Public Service Journalism: Power Distance and Objectivity

In summary, when it comes to PSM values, principles, goals, and functions, and the characteristics of its non-journalistic content, managers and journalists largely agreed on the essence of public service in PSM. However, the domain to which they devoted their attention, and where significant contradictions emerged, concerned the journalistic content. The RTVS journalists and managers discussed at length what public service journalism should look like. They used two strategies: they put it in contrast to commercial television, and, less often, they focused on the characteristics of the quality journalism that should be produced by PSM.

First, both the journalists and the managers stressed the non-commercial nature of the public service news and current affairs programmes, pointing out that it should focus on the hard news content and cover the topics that are relevant for the citizens, even though they are not necessarily commercially attractive (e.g., foreign affairs, regional news, legislation, environment, social topics, minorities). They also stressed that public service news and current affairs are not, and should not be, affected by infotainment and tabloidization, and they should be more factual and analytical, less shocking, less emotional, and use a more conservative visual style.

Commercial media in recent years is just infotainment. They cover the topics in a way that entertains the audience, and it goes at the expense of information. […] We [at RTVS] tried to bring information without emotion. […] And even those topics — there are many topics that do not get into the commercial media, but are important for people's lives. (Interview with an RTVS ex-reporter, September 2018)

Compulsory figures have always been here and always will be. Where else but in the public service media should top politicians present their boring official trips that would never be broadcast by commercial media because it will not bring them advertising and money. And that is why it is the role of the public service media, which is also paid by the voters of these parties. (Interview with an RTVS manager, September 2019)

In my opinion, it [the conflict] is about how to look at public service media and its overall role. I think they [the new management] got stuck in time, and they still think that public service television is supposed to be a medium in service of governmental circles and that this is encoded in their DNA. […] That they do not think of it as of a sovereign entity. (Interview with an RTVS Reporter, September 2018)

In my opinion, we should seek the truth and bring reliable information, of course, true information, as comprehensively as possible to the widest possible audience, so as to increase the ability — by members of that audience — to make competent decisions about their lives and their electoral decisions. […] And different opinions should be given space. (Interview with an RTVS ex-manager, October 2018)

We insisted on objective and balanced reporting. That means that if I quote a left-wing analyst, I should also give space to a right-wing perspective. And they didn't want to do that. They refused to do it because they know where the truth is. They know what the report is supposed to look like, what's right, and they're going to broadcast it that way. (Interview with an RTVS manager, September 2018)

The current management professes the so-called formal objectivity, an example of which is the famous five minutes to Jews, five minutes to Hitler, and the listeners, the viewers, should make their own opinion. (Interview with an RTVS reporter, February 2019)

Several examples can illustrate the disagreement. For instance, several interviewed journalists mentioned that after one of them made a TV story based on an international research study on pro-Russian propaganda, the Russian disinformation campaign, and hybrid threats in the countries of Eastern Europe, the leadership sharply criticised him for not giving space to the “other side” – the representatives of the Russian Federation, even though the Slovak Prime Minister himself had already stated the existence of these threats.

Another example could be the anti-government protests that took place in 2018 in the wake of the murder of the journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancée Martina Kušnírová. The murder sparked the biggest anti-government protests since the Velvet Revolution in 1989 (more than 120,000 people gathered in various Slovak cities to demonstrate) and culminated with the resignation of Prime Minister Robert Fico and his cabinet. Several interviewed journalists mentioned that the new management instructed the reporters who were covering the demonstrations to include the voices of ordinary people who did not take part in the protests so that the opinion of the “other side” could also be heard. As one of the interviewed journalists described, they found it absurd and did not comply:

For example, during yesterday's protests, they [the management] came up with the idea that we should go into the side streets and reach out to people who did not go to demonstrate to the main square. So that we could have a second opinion. My colleague and I laughed about it and agreed to say that it was not possible. (Interview with an RTVS reporter, February 2019)

Discussion

The analysis of how RTVS journalists and managers perceive the PSM mission and public service journalism provides at least two interesting findings that are worthy of further discussion. First, their perception of the PSM mission proved to be surprisingly reductive. To start, when it comes to the basic principles on which the PSM and its functioning should be based, both the managers and the journalists mostly mentioned independence from market pressure, but rarely referred to independence from political power, despite RTVS's recurring problems with political pressures. Also, they tended to describe the purpose and the position of PSM mainly in contrast to commercial media and not so much in contrast to state or state-funded media, even though RTVS was created by the transformation from a state-owned media organisation after the change of the political regime in 1989, and anecdotal evidence suggests that some members of the public (and even some politicians) still do not fully distinguish between the concepts of the state and public media. This could be explained by the fact that, as there are currently no state media in Slovakia, the only competitors for RTVS are commercial outlets. Nevertheless, given Slovakia's communist history and its long tradition of state media, and given that political pressure and the lack of political independence is such a widespread caveat typical for PSM in the post-communist countries (Milosavljević and Poler Citation2018; Šimunjak Citation2016), failing to stress the political independence of PSM when explaining this concept seems to be a missed opportunity.

A rather narrow understanding of the PSM mission on the side of the RTVS journalists and managers is also evident from the comparison of their perceptions with the definition of PSM in the scholarly literature and the legal framework. Although in many aspects their views are coherent with the usual legal and theoretical understanding of PSM, several important differences appear. Besides the complete omission of entertainment, the last part of the Reithian triad of “informing, educating and entertaining” which is also stated in the RTVS Act, surprisingly few journalists and managers stressed that PSM news and current affairs should scrutinise the powerful, and none mentioned the provision of interpretations and explanations, even though these are considered to be at the core of the PSM remit (Murdock Citation2005). Also, the aim of developing national identity and preserving national culture that is captured in the RTVS Act, and that was also identified as an essential element in the public debate on PSM in Norway (Larsen Citation2014) and as an aspect that is important to the German, Swedish, and Finnish PSM managers (Lowe and Maijanen Citation2019), was not mentioned by the Slovak participants. In addition, the RTVS journalists and managers overwhelmingly emphasised output rather than audiences when interpreting the public service mission. Although this is understandable given their production role, it suggests that the public itself (and its participation) is present rather indirectly in their conception of public service mission.

To summarise, the shared perception of PSM from the viewpoint of the RTVS journalists and managers seems to be closer to the market-failure perspective rather the democracy-centric perspective on PSM (Donders Citation2021). They construct PSM mainly as an antithesis to commercial media and see its value in the production of niche programmes and genres that are important, although not popular. On the one hand, this could be explained by the professional specialisation of the research participants. As they are all journalists or managers responsible for news and current affairs programmes, it is likely that their conception of public service stems from their everyday work, and their understanding of the broader PSM remit, especially when it comes to culture, entertainment, and sports, may be limited. After all, the characteristics of the PSM content, particularly public service journalism, was the most widely discussed element of the PSM remit, while the more abstract elements of PSM values, principles, and goals and functions attracted considerably less attention.

On the other hand, such a narrow understanding of PSM in line with market-failure perspective is unnecessarily reductive and defensive, and disregards PSM's broader contribution to a democratic public sphere. Also, it may not help much in convincing the public that PSM is worth paying for and deserves protection from political pressure. In this respect, who but the PSM journalists and managers should be able to convincingly explain the meaning of PSM and its contribution to society? An Austrian study of young people's perceptions and valuation of PSM (Reiter et al. Citation2018) noted that their knowledge of the meaning of the public value was shallow; this, to an extent, applies to the Slovak PSM journalists and managers as well. This may be a consequence of a long history of state-controlled media in Slovakia and the relative novelty of the PSM concept.

Second, another area that deserves attention is the deep disagreement over some of the core values of quality journalism, namely objectivity and power distance. In terms of the four aspects of objectivity described by Skovsgaard et al. (Citation2013), both sides of the conflict agreed on the principle of no subjectivity. This is where the agreement ends. The opposing journalists and the new managers disagreed on the importance of hard facts simply because they disagreed on where facts end and opinions begin, and whether there is such a thing as hard facts at all. This subsequently translated into disagreements over balance and value judgments. Because the new managers tended to hold agnostic views and because they were sceptical of the idea that it was possible to know where the truth lay, they interpreted objectivity as giving equal space to all sides of an argument and leaving the judgement up to the audience. At the same time, in their view, it is not the role of journalists to suggest which side of a dispute has a better position (e.g., in terms of truthfulness or relevance).

Thus, based on the interviews, it seems that the opposing journalists understood the concept of objectivity in line with the usual definition used in journalism studies (Donsbach and Klett Citation1993; Kovach and Rosenstiel Citation2001; Skovsgaard et al. Citation2013), while the new managers professed a rather limited understanding of objectivity and effectively reduced it to balance, or, more precisely, to what Brüggemann and Engesser (Citation2017) call “false balance”. This shows that the notion of objectivity is not only culture- or country-specific (Donsbach and Klett Citation1993), but it can also vary within a single newsroom. When such a disagreement occurs in one newsroom, as this case study demonstrates, serious conflicts can arise.

While the interpretation and implementation of the objectivity norm is undoubtedly a matter of debate in journalistic communities around the world and the question of the appropriate power distance is similarly contentious, the deep division within the RTVS newsroom is striking. The lack of basic consensus on the fundamentals of journalism points to the fragility of the journalism profession and the journalistic culture in Slovakia. This may still be a consequence of the profound transformation that the Slovak media system and journalism underwent after the change of the political regime in 1989. Here is an example to illustrate the poor level, or rather the absence of serious professional debate: while the BBC's Editorial Guidelines are 220 pages long, with a 10-page section on impartiality (BBC Citation2019), there is no similar document in the case of RTVS. The RTVS Programme Staff Charter merely reiterates the legal provision that RTVS should provide balanced and pluralistic information, emphasises the importance of distinguishing between news and commentary, and states that all sides of an argument should be given space (RTVS Citation2011).

Conclusion

While it is hardly surprising that different actors have different views of what public service means, one would expect the people whose job it is to apply this idea in practice, such as the journalists and managers working for PSM, would share a basic understanding of it. The case study of the conflict that took place in the Radio and Television of Slovakia demonstrates what can happen in a newsroom where the journalists and their managers differ significantly in how they perceive public service and interpret the PSM mission, including PSM journalism.

This does not mean that their views were fully divergent. Especially when it comes to PSM values, principles, goals and functions, and its non-journalistic content, managers and journalists largely agreed on their perceptions of the essence of public service in PSM. As the key features, almost all of them named independence from market pressure and a strong focus on hard news content (i.e., the information citizens need to make informed decisions), educational function, and the production of programmes and genres for minority viewers. On the contrary, none of the participants mentioned high-quality entertainment, sports, or innovation.

Public service journalism is the domain to which the RTVS journalists and managers devoted the most attention, and where significant contradictions emerged. Despite many similarities, the journalists and the new managers differed significantly in two important aspects: the interpretation of power distance and objectivity. First, the opposing journalists suspected the new managers of being too subservient to the ruling politicians and complained, for instance, of having to cover mundane activities of the top political representatives. The new managers considered such coverage to be a part of the PSM mission.

Second, and more importantly, the opposing journalists and the new managers had a profoundly different notion of objectivity (even though they referred to the same term). While the new managers were inclined to see the role of journalists in giving equal space to as wide a range of opinions (which are not illegal) as possible, the opposing journalists argued that the relevance of these opinions must be assessed and confronted with facts. In the view of journalists, if the news coverage is reduced to a simple overview of different opinions, it leads to an erosion of truth and facts and prevents the media from fulfilling their critical role. In short, a constant presentation of many different versions of reality can be as dangerous as insisting on a single truth.

Thus, while the new managers and journalists accused each other of not knowing what public service was, failing to deliver it, and even threatening it, the reference to public service served more as a discursive figure and a rhetorical means to justify and legitimise own position and contrast it with the opponents’ (supposedly flawed) stance. Indeed, the core of the conflict concerned merely the interpretation of objectivity and the power distance that are integral parts of journalistic culture (Hanitzsch Citation2007) and important aspects of quality journalism. However, quality journalism is only one, albeit undoubtedly significant, part of the PSM mission. Still, these disagreements were enough, together with mutual distrust and differences in political views, to cause permanent clashes and fuel mutual suspicions of being biased and politically motivated, and eventually led to protest resignations and dismissals of two thirds of the TV newsroom.

The good news, however, is that both sides of the conflict clearly embraced the concepts of public service and public service media. Although the RTVS journalists and managers differed in their understanding of the selected aspects of public service journalism, public service was clearly a value held dear by all of them, and the interviews suggest that the discursive references to it were genuine and sincerely meant. None of the positions and interpretations could be understood as a blatant rejection of what the concept stands for or as an inclination towards the notion of state or government led PSM (even if the new managers seem to place less importance on the critical watchdog role). For Slovakia, a country with a long history of state media, this is no small item.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Jaromír Volek for his help with the interviews and the research participants for sharing their perspectives and giving their valuable time to contribute to this research. I also wish to thank Karen Donders and the participants of the RIPE@2021: “Public Service Media's Contribution to Society” conference for their helpful suggestions, and the two anonymous reviewers for their careful reading and constructive comments, which have greatly enhanced the quality of the paper.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The proportion of the reporters and editors who resigned or did not have their contracts prolonged was calculated on the basis of data obtained from a source at RTVS who provided the author with a list of names of RTVS reporters and editors (including whether they resigned, were forced to leave, or stayed on); this information was then independently verified by another RTVS reporter.

2 Three of the 16 interviews were conducted by the author in collaboration with Jaromír Volek, whom the author would like to thank for his help.

3 According to the rules of the ethics committee of the Masaryk University, ethical approval was not required because the research project did not involve the use of biomedical techniques or vulnerable research subjects.

References

- Act No. 532/2010 Coll. On the Radio and Television of Slovakia. Retrieved from https://www.culture.gov.sk/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/act_RTVS_340-2.pdf.

- Ali, C. 2016. “The Merits of Merit Goods: Local Journalism and Public Policy in a Time of Austerity.” Journal of Information Policy 6: 105–128. doi:10.5325/jinfopoli.6.2016.0105.

- Bajomi-Lazar, P. 2017. “Particularistic and Universalistic Media Policies: Inequalities in the Media in Hungary.” Javnost - The Public 24 (2): 162–172. doi:10.1080/13183222.2017.1288781.

- BBC. 2019. The Editorial Guidelines. London: BBC. Retrieved from http://downloads.bbc.co.uk/guidelines/editorialguidelines/pdfs/bbc-editorial-guidelines-whole-document.pdf.

- Born, G., and T. Prosser. 2001. “Culture and Consumerism: Citizenship, Public Service Broadcasting and the BBC’s Fair Trading Obligations.” Modern Law Review 64 (5): 657–687. doi:10.1111/1468-2230.00345.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research In Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Brüggemann, M., and S. Engesser. 2017. “Beyond False Balance: How Interpretive Journalism Shapes Media Coverage of Climate Change.” Global Environmental Change 42: 58–67. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.11.004.

- Campos-Rueda, M., and M. Goyanes. 2022. “Public Service Media for Better Democracies: Testing the Role of Perceptual and Structural Variables in Shaping Citizens’ Evaluations of Public Television.” Journalism, OnlineFirst. doi:10.1177/14648849221114948.

- Chapman, A. 2017. Pluralism Under Attack: The Assault on Press Freedom in Poland. Washington, New York: Freedom House. Retrieved from https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/FH_Poland_Report_Final_2017.pdf.

- DeFleur, M. L., and E. E. Dennis. 1991. Understanding Mass Communication. 4th ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Deuze, M. 2005. “What is Journalism? Professional Identity and Ideology of Journalists Reconsidered.” Journalism 6 (4): 442–464. doi:10.1177/1464884905056815.

- Donders, K. 2012. Public Service Media and Policy in Europe. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Donders, K. 2021. Public Service Media in Europe: Law, Theory and Practice. London and New York: Routledge.

- Donsbach, W., and B. Klett. 1993. “Subjective Objectivity. How Journalists in Four Countries Define a key Term of Their Profession.” Gazette (Leiden, Netherlands) 51 (1): 53–83. doi:10.1177/001654929305100104.

- European Broadcasting Union. 2014. Public Service Values, Editorial Principles and Guidelines. Geneva: European Broadcasting Union.

- Gil de Zúñiga, H., and A. Hinsley. 2013. “The Press Versus the Public.” Journalism Studies 14 (6): 926–942. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2012.744551.

- Gindl, E. 1996. Médiá [The Media]. Slovensko 1995: Súhrnná správa o stave spoločnosti [Slovakia 1995: Summary Report on the State of the Society], 219-236. Retrieved from http://www.ivo.sk/buxus/docs//publikacie/subory/Slovensko_1995_web.pdf.

- Hanitzsch, T. 2007. “Deconstructing Journalism Culture: Toward a Universal Theory.” Communication Theory 17 (4): 367–385. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2007.00303.x.

- Hanitzsch, T. 2011. “Populist Disseminators, Detached Watchdogs, Critical Change Agents and Opportunist Facilitators.” International Communication Gazette 73 (6): 477–494. doi:10.1177/1748048511412279.

- Hanitzsch, T., F. Hanusch, J. Ramaprasad, and A. S. De Beer. 2019. Worlds of Journalism: Journalistic Cultures Around the Globe. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Hanretty, C. 2011. Public Broadcasting and Political Interference. New York: Routledge.

- Hujanen, J. 2009. “Informing, Entertaining, Empowering: Finnish Press Journalists’ (Re)Negotiation of their Tasks.” Journalism Practice 3 (1): 30–45. doi:10.1080/17512780802560724.

- Ibarra, K. A., and L. W. Nord. 2013. “Still Something Special?: A Comparative Study of Public Service Journalists’ Values in Spain and Sweden.” Journal of Applied Journalism & Media Studies 2 (1): 161–179. doi:10.1386/ajms.2.1.161_1.

- Jenkins, J., and R. K. Nielsen. 2020. “Proximity, Public Service, and Popularity: A Comparative Study of How.” Local Journalists View Quality News. Journalism Studies 21 (2): 236–253. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2019.1636704.

- Jusić, T., M. Puppis, L. C. Herrero, and D. Marko. 2021. Up in the Air? The Future of Public Service Media in the Western Balkans. Budapest, New York: Central European University Press.

- Just, N., M. Büchi, and M. Latzer. 2017. “A Blind Spot in Public Broadcasters’ Discovery of the Public: How the Public Values Public Service.” International Journal of Communication 11: 992–1011. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/6591.

- Kovach, B., and T. Rosenstiel. 2001. The Elements of Journalism: What Newspeople Should Know and the Public Should Expect. New York: Crown.

- Lacy, S., and T. Rosenstiel. 2015. Defining and Measuring Quality Journalism. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers School of Communication and Information.

- Lamuedra, M., C. M. Martín, and M. A. Broullón-Lozano. 2019. “Normative and Audience Discourses on Public Service Journalism at a “Critical Juncture”: The Case of TVE in Spain.” Journalism Studies 20 (11): 1528–1545. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2018.1528880.

- Lamuedra Graván, M., C. Mateos, and M. A. Broullón-Lozano. 2020. “The Role of Public Service Journalism and Television in Fostering Public Voice and the Capacity to Consent: An Analysis of Spanish Viewers’ Discourses.” Journalism 21 (11): 1798–1815. doi:10.1177/1464884919847593.

- Larsen, H. 2010. “Legitimation Strategies of Public Service Broadcasters: The Divergent Rhetoric in Norway and Sweden.” Media, Culture & Society 32 (2): 267–283. doi:10.1177/0163443709355610.

- Larsen, H. 2014. “The Legitimacy of Public Service Broadcasting in the 21 st Century: The Case of Scandinavia.” Nordicom Review 35 (2): 65–76. doi:10.2478/nor-2014-0015.

- Lis, B., H.-W. Nienstedt, and C. Günster. 2017. “No Public Value Without a Valued Public.” International Journal on Media Management 20 (1): 25–50. doi:10.1080/14241277.2017.1389730.

- Loosen, W., J. Reimer, and S. Hölig. 2020. “What Journalists Want and What They Ought to Do (In)Congruences Between Journalists’ Role Conceptions and Audiences’ Expectations.” Journalism Studies 21 (12): 1744–1774. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2020.1790026.

- Lowe, G. F., and P. Maijanen. 2019. “Making Sense of the Public Service Mission in Media: Youth Audiences, Competition, and Strategic Management.” Journal of Media Business Studies 16 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1080/16522354.2018.1553279.

- Maijanen, P. 2015. “The Evolution of Dominant Logic: 40 Years of Strategic Framing in the Finnish Broadcasting Company.” Journal of Media Business Studies 12 (3): 168–184. doi:10.1080/16522354.2015.1069482.

- Milosavljević, M., and M. Poler. 2018. “Balkanization and Pauperization: Analysis of Media Capture of Public Service Broadcasters in the Western Balkans.” Journalism 19 (8): 1149–1164. doi:10.1177/1464884917724629.

- Moe, H., and T. Syvertsen. 2007. “Media Institutions as a Research Field: Three Phases of Norwegian Broadcasting Research.” Nordicom Review 28 (2): 149–167. https://bora.uib.no/bora-xmlui/handle/1956/2332.

- Moe, H., and T. Syvertsen. 2009. “Researching Public Service Broadcasting.” In The Handbook of Journalism Studies, edited by K. Wahl-Jorgensen, and T. Hanitzsch, 398–412. Abingdon, New York: Routledge.

- Murdock, G. 2005. “Public Broadcasting and Democratic Culture: Consumers, Citizens, and Communards.” In A Companion to Television, edited by J. Wasko, 174–198. Malden, Oxford, Carlton: Blackwell Publishing.

- Newton Media. 2018. Politická vyváženosť spravodajstva RTVS: Mika vs. Rezník [Political balance of RTVS news: Mika vs. Rezník]. Retrieved from https://www.newtonmedia.sk/politicka-vyvazenost-spravodajstva-rtvs-mika-vs-reznik/.

- Nowak, E. 2014. Autonomy and Regulatory Frameworks of Public Service Media in the Triangle of Politics, the Public and Economy: A Comparative Approach. Working Paper. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. Retrieved from https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/FH_Poland_Report_Final_2017.pdf.

- Otvorený list [Open letter]. 2018, April 4. Otvorený list členov Sekcie spravodajstva a publicistiky RTVS (plné znenie) [Open Letter of the Members of the News and Current Affair Section to the Viewers and Listeners (Full Text)]. Sme. Retrieved from https://domov.sme.sk/c/20795636/otvoreny-list-clenov-sekcie-spravodajstva-a-publicistiky-rtvs-plne-znenie-reznik.html.

- Połońska, E., and C. Beckett. 2019. Public Service Broadcasting and Media Systems in Troubled European Democracies. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Polyák, G. 2015. “The Hungarian Media System. Stopping Short or Re-Transformation?” Südosteuropa 63 (2): 272–318. doi:10.1515/soeu-2015-630207.

- Reiter, G., N. Gonser, M. Grammel, and J. Gründl. 2018. “Young Audiences and Their Valuation of Public Service Media: A Case Study in Austria.” In Public Service Media in the Networked Society, edited by K. D. H. Van den Bulck, and G. F. Lowe, 211–226. Göteborg: Nordicom.

- Riedl, A., and J.-M. Eberl. 2022. “Audience Expectations of Journalism: What’s Politics got to do with it?” Journalism 23 (8): 1682–1699. doi:10.1177/1464884920976422.

- RTVS. 2011. Štatút programových pracovníkov a spolupracovníkov Rozhlasu a Televízie Slovenska [The RTVS Programme Staff Charter]. Bratislava: RTVS. Retrieved from: https://www.rtvs.org/media/a542/file/item/sk/0000/statut-programovych-pracovnikov-a-spolupracovnikov-rtvs.52.pdf.

- RTVS. 2018. Stanovisko generálneho riaditeľa a vedenia spravodajstva a publicistiky RTVS k otvorenému listu niektorých redaktorov a editorov [Statement of the Director General and the management of RTVS news and current affairs on the open letter of some reporters and editors] [Online]. Retrieved February 12, 2023, from RTVS Website: https://www.rtvs.org/aktualne-oznamy-tlacove-spravy-pr/160807_stanovisko-generalneho-riaditela-a-vedenia-spravodajstva-a-publicistiky-rtvs-k-otvorenemu-listu-niekto.

- Scannel, P. 1990. “Public Service Broadcasting: The History of a Concept.” In Understanding Television, edited by A. Goodwin, and G. Whannel, 11–29. London, New York: Routledge.

- Schweizer, C., and M. Puppis. 2018. “Public Service Media in the ‘Network’ Era: A Comparison of Remits, Funding, and Debate in 17 Countries.” In Public Service Media in the Networked Society, edited by G. F. Lowe, H. Van den Bulck, and K. Donders, 109–124. Göteborg: Nordicom.

- Šimková, M. 2018, May 3. “Vahram Chuguryan: Verejné kritizovanie vedenia predsa nemôže zaručovať externistom imunitu [Vahram Chuguryan: Public Criticism of the Leadership Cannot Guarantee Immunity for Outsiders].” Hospodárske noviny. https://hnonline.sk/slovensko/1738858-vahram-chuguryan-verejne-kritizovanie-vedenia-predsa-nemoze-zarucovat-externistom-imunitu.

- Šimunjak, M. 2016. “Monitoring Political Independence of Public Service Media: Comparative Analysis Across 19 European Union Member States.” Journal of Media Business Studies 13 (3): 153–169. doi:10.1080/16522354.2016.1227529.

- Skovsgaard, M., E. Albæk, P. Bro, and C. de Vreese. 2013. “A Reality Check: How Journalists’ Role Perceptions Impact Their Implementation of the Objectivity Norm.” Journalism 14 (1): 22–42. doi:10.1177/1464884912442286.

- Transparency International Slovakia. 2015. “TASR robí za štátne volebnú kampaň SNS [TASR is doing an election campaign for SNS using public money] [Online].” Retrieved from https://transparency.blog.sme.sk/c/383543/tasr-robi-za-statne-volebnu-kampan-sns.html.

- Transparency International Slovakia. 2019. “Po TASR pomáha Rezník Dankovi aj v RTVS [After TASR, Rezník also helps Danko at RTVS] [Online].” Retrieved from https://transparency.sk/sk/po-tasr-pomaha-reznik-dankovi-aj-v-rtvs/.

- Tsfati, Y., O. Meyers, and Y. Peri. 2006. “What is Good Journalism? Comparing Israeli Public and Journalists’ Perspectives.” Journalism 7 (2): 152–173. doi:10.1177/1464884906062603.

- UNESCO. 2005. Public Service Broadcasting: A Best Practices Guide. New York, NY: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

- Urbániková, M. 2021. “Resisting Perceived Interference in Journalistic Autonomy: The Study of Public Service Media in Slovakia.” Media and Communication 9 (4): 93–103. doi:10.17645/mac.v9i4.4204.

- Vagovič, M. 2007, August 9. “Spravodajstvo STV je v rozklade [STV's news service is in a decay].” Denník SME. https://www.sme.sk/c/3431507/spravodajstvo-stv-je-v-rozklade.html.

- van der Wurff, R., and K. Schoenbach. 2014. “Civic and Citizen Demands of News Media and Journalists.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 91 (3): 433–451. doi:10.1177/1077699014538974.

- Vos, T. P., M. Eichholz, and T. Karaliova. 2019. “Audiences and Journalistic Capital: Roles of Journalism.” Journalism Studies 20 (7): 1009–1027. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2018.1477551.

- Węglińska, A. 2021. Public Television in Poland: Political Pressure and Public Service Media in a Post-Communist Country. London and New York: Routledge.

- Yin, R. K. 2018. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Zuzana Kovacic Hanzelova. 2018, April 27. Dnešným dňom ohlásilo vedenie prepúšťanie externistov. Teda, prepáčte, ako to povedalo naše vedenie, nie prepúšťanie, ale ukončenie spolupráce [Today, management announced layoffs of freelancers. I mean, I apologise, as our management put it, not redundancies, but the termination of cooperation]. [Status update]. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/zuzana.hanzelova.1/posts/10213832579461357.