ABSTRACT

Understanding journalistic truth has always been important in Journalism Studies, but it is increasingly significant in a society influenced by constantly evolving digital technologies and information disorder. This article explores the potential of “actor-network theory” to enhance the understanding of journalistic truth, surpassing the limitations of existing perspectives that categorise it as objective, subjective, or a combination of the two. Alternatively, through the utilisation of a plausibility probe case study in investigative journalism, the article suggests examining news-making as black-boxing and conceptualises journalistic truth as arising from the skilful construction of journalistic chains comprising heterogeneous actors. We discuss these as pivotal steps toward gaining a deeper understanding of journalistic truth that paves the way for constructing an alternative but empirical account of journalism.

The concept of “journalistic truth” has always been a topic of debate in the world of journalism, but recent technological advancements, new business models in journalism, and allegations of fake news have brought renewed attention to the subject (Godler, Reich, and Miller Citation2020; Muñoz-Torres Citation2012; Steiner Citation2018). As a result, Scholars are now criticising how journalism scholarship understands journalistic truth, specially the “epistemology of journalism”; how journalists and news organisations know what they know, and how knowledge claims are articulated and justified (Ekström and Westlund Citation2019; Lau Citation2004; Ward Citation2018). The primary criticism revolves around the dichotomised theoretical assumptions that separate news into either a matter of fact or a social construction. As a result, there is a demand for a better, theory-informed, nuanced, alternative understanding of journalistic truth (Ward Citation2018). This article proposes that Actor-Network Theory (ANT) can offer an alternative, more robust, and an empirically grounded understanding of journalistic truth. Specifically, by drawing on ANT concepts of black-boxing and proposing the idea of journalistic chains, the article puts forth an alternative perspective on news-making that enable us to avoid the subject-object divide in the epistemology of journalism. Our proposition is to view news-making as a process of progressive black-boxing, and to see journalistic truth as the emerging result of establishing journalistic chains. Through an investigation of a case study in investigative journalism, the article aims to answer “How can we rethink journalistic truth and the epistemology journalism with ANT?

Concept of Truth in Journalism and its Epistemology

The concepts of truth in journalism have been extensively debated among professionals, in public discourse, and academia, primarily revolving on two opposing philosophical perspectives (Broersma Citation2010; Ekström and Westlund Citation2019; Ward Citation2018; Witschge et al. Citation2019a). At one end of the spectrum, journalistic truth is defined based on the philosophical assumption of “realism”. The label “realism” refers to a broader group of ideas that emphasises the objective existence of a reality independent of human perceptions: “objectivity”, “positivism” and “empiricism” (Maras Citation2012, 82). These different ideas can take on different forms, ranging from naïve realism (also known as common-sense realism) (Coddington Citation2015; Ward Citation2018), which assumes that what human perceive with their senses is absolute truth, to a more nuanced and professional version that recognises the challenges of reporting an objective truth while still emphasising certain practices and notions that may help achieve it, such as “objectivity” or “fact based” or “verified” (Anderson and Schudson Citation2019; Curry and Stroud Citation2021; Muñoz-Torres Citation2007; Rupar Citation2006; Wien Citation2017). This “realism” perspective, while less common in academia, is predominantly prevailing among professionals as their way of understanding (and idealising) journalistic truth (Hearns-Branaman Citation2018; Muñoz-Torres Citation2007; Rupar Citation2006).

On the other end of the spectrum, mainstream academia has defined journalistic knowledge through an anti-realistic perspective, arguing for journalistic knowledge to be a social construction (Ekström and Westlund Citation2019; Godler, Reich, and Miller Citation2020, 214). The label “social constructivism” here refers to a broader set of ideas that emphasises the reality (Truth and knowledge) is constructed by humans using concepts, beliefs, perspectives, values, and social institutions (Hearns-Branaman Citation2018, 81; Ward Citation2018). This approach to journalism research draws on seminal works in the “60 and “70 exploring social constructivism such as: Berger & Luckman’s social construction of reality (Berger and Luckmann Citation1991), and Hall’s cultural studies (Hall Citation1973) (Hearns-Branaman Citation2018; Wahl-Jorgensen and Hanitzsch Citation2009). Similarly, to “realism”, “social constructivism” also takes different forms. On one end, it could take a radical social constructivist approach, claiming that “Fact […] simply as that which is accepted as reality.” (Ericson Citation1998). Alternatively, social constructivism can also take on a softer and more operationalised form, which suggests that; “The production of news is a social achievement, in order for something to be acceptable as news, it has to be the product of certain socially approved procedure” (Hearns-Branaman Citation2018, 81). These softer perspectives acknowledge the subjectivity inherent in news production but seek to demonstrate how news is constructed within a socially approved framework (Curry and Stroud Citation2021; Prochazka and Obermaier Citation2022).

Epistemology of journalism is an area that specifically examines these debates related journalistic knowledge (truth) and seek to understand how journalists acquire knowledge, and how they articulate and validate their claims (Ekström and Westlund Citation2019; Ettema and Glasser Citation1984; Graves Citation2016; Uscinski and Butler Citation2013). Though, even if the term “epistemology” is fundamentally philosophical, the area of “epistemology of journalism” has been mainly sociological hence “flourished” with social constructivist work (Ekström and Westlund Citation2019; Godler, Reich, and Miller Citation2020; Hearns-Branaman Citation2018). For instance, Tuchman's (Citation1980) seminal work is an example of this anti-realism approach in epistemology of journalism, where she views supporting evidence—what a realist would otherwise describe as fact—as a social construction of knowledge rather than a truth-oriented concept nuanced in a philosophical ground (Godler, Reich, and Miller Citation2020; Lau Citation2004; Tuchman Citation1980).

Limitations and Alternative Theories

Both the realist and social constructivist approaches to journalistic truth (journalistic knowledge) have been recently criticised by scholars as incomplete, inadequate, and bifurcated (Godler, Reich, and Miller Citation2020; Lau Citation2004; Martine and De Maeyer Citation2019; Ward Citation2018). Mindful of Kant’s “Critique of Pure Reason”, realist assumptions regarding objective truth have been questioned on the grounds that journalists are human beings and therefore subjective, making the idea of an objective “view from nowhere” impossible (Maras Citation2012; Romano Citation1986; Rosen Citation1993). This criticism is connected to a professional critique that accuses journalists of “frame blindness” enabled by the pursuit of objectivity. “Frame-blindness” describes a situation in which journalists fail to recognise the ideological nature of their own framing of issues (Maras Citation2012, 66).

Moreover, scholars argue that the pursuit of objective truth and factual reporting in journalism overlooks the inherently subjective nature of socio-political contexts and the subjective nature of opinions that are often discussed in politics (Gaitano, López-Escobar, and Martín Algarra Citation2022; Graves Citation2016; Uscinski and Butler Citation2013). Moreover, the emphasis on objectivity in journalism has downgraded other forms of reporting, such as advocacy, opinion, and citizen journalism, to the side-lines (Waisbord Citation2008). These genres are academically considered separate from “hard news” and are often explained in a more subjective manner, while hard news is presented as factual. (This asymmetrical treatment raises important theoretical questions that will be discussed later).

Similarly, while the social constructivist approach does well to account for the socio-political context in news-making, it has also been criticised for undermining the credibility of journalism and making it indistinguishable from propaganda or falsehood (Godler, Reich, and Miller Citation2020; Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2016). For instance, when describing a fact within a social constructivist framework, it becomes challenging to differentiate between the truth and falsehood (Molotch and Lester Citation1974, 104) as both of them are now a mere subjective matter of concern that vary depending on cultural, historical, and political contexts. Additionally, the approach is also faced criticism for its inability to fully account for the recent role of technological actors in the generation and consumption of journalistic knowledge (Stalph Citation2019). New digital platforms, algorithms, and big data have become significant sources of information for journalists, shaping the content they produce, and the way it is consumed by the public (Turner Citation2005b; Wölker and Powell Citation2021) but their impact have not been adequately addressed in social constructivist approaches (Domingo, Masip, and Meijer Citation2015; Turner Citation2005a).

To overcome these limitations, go beyond the subject and object divide, and account for new changes in journalism, recent theoretical developments have emerged drawing from various disciplines, such as general epistemology, critical theory, science and technology studies, and political science (Ekström and Westlund Citation2019). While different among each other, they all explore new theories and aim to redefine and rethink journalistic truth and epistemology of journalism beyond the traditional divide. For example, scholars like Farkas and Schou Citation2019) and Stuart Allan Citation2006) ground their work on Gramsci’s ideas and argue for the existence of facticity in “subjective” reporting. On the other hand, while Lau (Citation2004) aims to redefine journalistic truth by building his work on Roy Bashkar's critical realism, Martine and De Maeyer's (Citation2019) use the work of Bruno Latour to propose an alternative description of news-making. Other works promote different ideas and professional changes in journalism practices as a remedy: Curry & Stroud’s idea of transparency (Citation2021) or Stainer’s rigorous methods inspired by feminist theory (Citation2018). All these alternative theories seek to address the underlying philosophical problem of the realism vs social constructivism divide while at the same time they seek to protect the reliability of journalism and prevent unwarranted attacks, such as accusations of fake news that serve others’ interests. They also aim to bridge the contrast gap between how theory and practice define the truth, with professionals often resorting to realism while scholarships resorting to social constructivism. Finally, they all aim to ground notions of journalistic truth in empirical research by examining the actual practices of those who gather and report the news, including the impact and role of new emerging technologies.

Despite these goals, the proposed alternatives also have limitations and have been subject to criticism. A group of scholars — who initial contributed for alternative theories — highlighted some of these constraints (Witschge et al. Citation2019b). First, most of these approaches are developed in reaction to the blurring boundaries and recent changes of journalism, particularly to understand digital journalism (Stalph Citation2019), thus implicitly suggesting a sort of historical purity in journalism. Second, in the context of comprehending the emerging role of technology in journalism, these approaches seem to undervalue the importance of journalistic norms and values, resulting in a classification of all aspects as a convoluted combination of subjectivity and objectivity (social and technological) (Witschge et al. Citation2019a). These criticisms extend also to those works that utilises ANT and which we review soon. However, we contend that the criticism to these ANT’s inspired works stems from a partial use of ANT, and that ANT still has untapped potentials to address some of the issue characterising Journalism Studies and epistemology today. To explore these potentials, we now introduce ANT with a particular focus on the concept of “black box” and “chain”. Drawing on these notions, we propose a redefinition of news-making as black-boxing and of journalistic truth as emerging from the establishment of journalistic chains.

Actor-Network Theory in Journalism Studies

Actor-network theory (ANT) emerged in the 1970s as a response to the deterministic and reductionistic approaches used to study science and technology. Developed by Bruno Latour (e.g., Citation1988), Michel Callon (e.g., 1999), and John Law (e.g., 1992), ANT proposes that all phenomena arise from heterogeneous and dynamic networks of relationships between various actors, including humans and non-humans (Law Citation2007). An actor is defined by its ability to act (do thing) in the network and includes people, tools, machines, natural entities, words, institutions, laws, and anything whose absence would lead to a different outcome or social reality. Hence ANT aims to understand how these actors work together to shape reality. With these premises that are critical of both the realism and the social constructivism perspectives, scholars in Journalism Studies have adopted ANT to further explore alternatives to face some of the field's challenges (see Primo and Zago Citation2015; Stalph Citation2019; Turner Citation2005a; Weiss and Domingo Citation2010). For instance, Hemmingway Citation2005) uses ANT to better conceptualise the agency of technology in news construction emerging from the interaction of a plurality of actors. Domingo and Wiard Citation2016) used ANT to show the evolution of journalism as a contingent yet relatively stable institution whose everyday practices are shaped by power struggles over its role in society. However, fewer attempts have used ANT to discuss the notion of truth. For instance, Martine and De Maeyer (Citation2019) have attempted to reconceptualised journalistic objectivity through ANT by adapting the notion of “Chain of reference” (explained below) as an alternative approach to define truth beyond absolute terms (either objective or subjective) or subtractive terms (objectivity is achieved when journalists expunge values from facts). Similarly, Pantumsinchai (Citation2018) proposed utilising ANT to map social construction of falsehood in social media platforms related to (fake) news distribution (Pantumsinchai Citation2018). As mentioned, while we praise these early attempts to use ANT, we believe these applications of the theory to be partial and limited. It will soon become apparent to the reader that Martine and De Maeyer's (Citation2019) work shares similarities with ours in terms of proposing how journalists can build chains of actor leading to the establishment of journalistic truth. We will however contend that their use of the Laturian term of “reference” limit their considerations solely to the genre of factual writing (Martine and De Maeyer Citation2019, 7). Pantumsinchai’s proposal is also interesting but only uses ANT to specifically describe the falsehood of news, especially in social media platforms, and how to extend the same approach to other truth-reporting processes remains unexplored and unclear.

These limitations, partial explanations as well the divide in Journalism Studies, echo a debate that was much influential in the early positioning of ANT itself and which is worth rekindling here. The “Strong empirical programme in the sociology of knowledge” was first to put forward a principle of symmetry to be used when looking at the production of (scientific) knowledge. A fundamental tenet of this approach was that the same type of cause should explain both the establishment of a true or a false belief (Bloor Citation1991). This approach rejected the idea of explaining true beliefs, such as scientific facts, as determined by nature (a realist position), while false beliefs, such as hoaxes, as determined and produced by humans, groups, or society (a constructivist position). Bloor’s et al. (also known as the School of Edinburgh and Bath) proposed an as ambitious as controversial, strong sociological programme that would use the same type of social explanation for both truth or falsity, success or failure, rationality or irrationality thus avoiding to offer different type of (biased) explanation when dealing with one or another. For us, this refers to Martine & De Maeyer’s concentration on journalism as science, or to Pantumsinchai’s focus on falsehood.

Departing and distinguishing from the EPOR’s idea of sociological symmetry, Latour further developed the principle of generalised symmetry which sees agency (the ability to act, do make a difference, to cause change) as an emerging effect of network of associations between humans and not humans thus making them co-responsible for action and transformations in our world (e.g., the establishment of a new scientific fact, but also of a fraud). This position is agnostic because it refuses any apriori explanatory framework that attribute causal agency to either the humans (like the EPOR programme and all the constructivist perspectives) or the non-humans (like the realist perspectives). Instead of imposing predetermined explanations based on a sociological or materialist perspective, ANT’s generalised symmetry asks the researcher to map and describe the formation, stabilisation, and constant shifting of such networks. This is how Latour has applied Actor-Network Theory (ANT) to a series of domains, also referred to as different “truth regimes': Law, as seen in “Making of Law” (Citation2010a); technological innovation, exemplified by “Aramis, or, the love of technology” (Citation1996); religion, explored in “Beyond belief” (Citation2010b); politics; and ecology, as discussed in “Politics of Nature” (Citation2004) and “Facing Gaia” (Citation2017). Despite the seemingly disparate areas of inquiry, Latour has consistently mapped and described these different areas of our modern life as heterogeneous networks which come together, gets aligned and stabilise to act as a whole. This brings us to our first proposition suggesting looking at news-making as black-boxing.

News-making as a Black-boxing

In ANT, the term black-box is used when a network of heterogeneous human and non-human actors aligns and stabilises its association to act as a whole so that it is accepted as a single actor. Black-boxing then becomes the process of making a joint production of action, facts or artefacts entirely opaque (Latour Citation1999). Callon and Latour Citation1981) explain, “a black box contains that which no longer needs to be reconsidered, those things whose contents have become a matter of indifference”. Latour uses H2O as an example and asks, “who refers now to Lavoisier’s paper when a writing formula for H2O” (Latour Citation1988). All the paperwork, all the enabling theories and calculations, the models, books, and instruments that Lavoisier used have been carefully aligned together to produce a new scientific statement about the structure of a water molecule. Resonating the Heideggerian notion of breakdown, Latour explains that we notice a black box only when it stops working as a whole: no more than a hammer, a projector suddenly turns into a complicated assemblage of parts, a controversy, as soon as it stops functioning. Throughout his works, Latour has shown how all modern human activities aim at creating such durable and unquestionable black boxes. This could vary from manufacturing an engine to establishing a social relationship like marriage or doing a degree (Harman Citation2009a), or, as in our case, making a piece of news.

It is crucial to distinguish the meaning of “black box” in ANT from its use in journalism transparency discourse to avoid confusion. In journalism transparency, “black box” has a negative connotation, referring to information produced in newsrooms that are concealed from public scrutiny (Ananny and Crawford Citation2018; Curry and Stroud Citation2021). In contrast, in ANT, “black boxing” denotes the process of stabilising and aligning individual contributions to a collective action. While both meanings involve opaqueness, their implications differ. In ANT, black-boxing signifies alignment, whereas, in journalism transparency, it implies secrecy and non-disclosure. “News you can trust is news you can use” —is a tagline that appeared on the BBC website (Alderhill Citation2021).—impeccably summarises our first proposition, which is to see journalistic truth as a black box, a well built one which the audience can trust and use without “unpacking” it, that is, without questioning the multitude of actors that have been aligned and associated together during its “making”.

Looking at journalistic truth as a black box begs us to pose the questions of how this black box is established, of what becomes opaque and indifferent in news-making, of what heterogeneous actors get together, and how their associations are made and maintained. These questions lead us to our second proposition, which requires us to counterbalance the generality of the notion of network and black box (in ANT everything is a network, and everything stable is a black box). This leads us to investigate at the particular way in which humans and non-humans are aligned and black box in journalistic networks that enable the creation of truthful, trustworthy, and ready-to-use news.

Journalistic Truth as What Emerge from Journalistic Chains

For Latour, things can exist and be truthful (be black boxed) scientifically, religiously, legally, politically and in many other ways. Throughout the years, Latour tried to identify the specificities of these different truth regimes, that is to see how black boxed are established in these different regimes. It is crucial that these regimes are not to be confused with different domains, somehow suggesting a sort of purity within the individual domains: Latour spent the first thirty years of his work continuously repeating that things are never pure. Thus, not everything in the establishment of a scientific fact (scientific black box) is scientific: lots of different actors (e.g., natural, but also legal, technical, political, etc.) partake in its establishment (and the same goes for a political or technical or legal fact to be established). This heterogeneity of actors (e.g., legal, natural, technical, perhaps political) and of their associations (e.g., physical, legal, financial) is captured by the notion of network, but this notion says nothing about how these entities are (or ought to) be aligned together to form a solid black box. To be scientific, namely for a network of heterogeneous actors to be correctly black boxed into a scientific fact, a network of heterogeneous actors must be articulated and aligned in a particularly scientific way. And our argument is precisely that for a network of heterogeneous actors to be black boxed into news, these actors must be aligned together in a specific way. To capture the way in which heterogeneous entities are progressively associated together and aligned to create a solid black box, Latour proposes the subsequent term of chains which looks at the order and criteria of associating and translating actors.

Possibly the most popular example from Latour is that of “chains of reference,” which he used to account for the establishment of a scientific fact. When Latour looks at science, everything hinges on the question of the correspondence between the world (a phenomenon) and statements about the world (a published article about the phenomenon). Latour first presents this notion in his famous “Circulating Reference: Sampling the Soil in the Amazon Forest” (Latour Citation1999), where he shadowed a group of scientists trying to establish if the Amazonian forest is expanding (or not) in certain areas. First, the trees in the jungle are labelled with numbers and marked on a map. Then, nearby soil samples are collected and ordered in a pedo-comparator which allows comparing the colours (via a Mansell chart) of samples from different locations. These comparisons will become entries in a spreadsheet, and then in a diagram plotting certain “movements of the forest”. At each passage (translation is the ANT term here), something is lost (reduced), and something is gained (amplified). For instance, in putting soil samples on a sorting box (pedo-comparator), we move from a muddy and messy “world” in the middle of the jungle to ordered and comparable “signs. In losing direct contact with the forest, scientists get closer to a publication establishing a new scientific fact about the forest. At each passage, a discontinuity occurs, yet associations are made in a way that a scientific continuity is maintained and made re-traceable. Latour calls these chains of circulating references, each one pointing to the one before: going backwards, the prose of the final report speaks of a diagram, which summarises the comparisons displayed by the pedo-comparator, which extracted, classified, and coded the soil, which, in the end, was marked, ruled, and designated through the crisscrossing of coordinates, maps, jeeps, labelled trees and local guides, etc. If all goes well, such a chain of reference will result in augmenting both the mobility (from world to statements about the world) and the immutability of the expansion of the forest (the fact being transported/verified/established/black boxed through a chain of circulating reference).

The idea of “chain of reference” is the very idea that Martine and De Maeyer (Citation2019) have been used to describe journalistic truth (Martine and De Maeyer Citation2019). At a first glance, the correspondence between the world (a fact) and statements about the world (a published news about that fact) is central in journalism too. However, as previously mentioned, Martine & De Maeyer proposed an approach that encourages us to view journalistic chains in a manner similar to how Latour perceive circulating references among scientists. Although this perspective may facilitate comprehension of factual reporting, regarding journalistic actions merely as references obstructs the ability to fully capture the uniqueness of journalism. By comparing journalism to the assumed superior standard of science and its epistemology, their proposition overlooks what sets journalism apart and hinders a comprehensive understanding of its distinct qualities. Latour would call this a “category mistake”, something that happens when we confuse and mix the different ways in which these chains are established and black boxed in various regimes. If we rather want to “speak well” (Latour Citation2013, 58) about journalism, we suggest we need to investigate and focus on qualifying journalistic chains as distinct from scientific ones (but also from legal, religious, etc …). For instance, in his book “The making of law”, Latour (Citation2010b) focuses on legal truth and looks, again, at how legal facts are established, black boxed. In ethnographically shadowing lawyers, he identified how much of their work is that of tracing factual elements (e.g., a piece of evidence) to pre-recorded “qualifications’ (e.g., legal definitions of what count as evidence) which bind their behaviour. Similarly, to scientists, lawyers also work with heterogeneous actors, and they align them by establishing chains. However, in this case, Latour proposes to call them “chains of obligations’ instead of references because what these actors do is different: they do refer to an earlier step in some manner, but what sets legal chains apart is their binding to behaviour. In this way, establishing chains of obligations is the legal way to black box a legal truth. It is our job now to look at a case study, trying to investigate news-making as black-boxing, specifically trying to capture how journalistic chains emerge and journalistic truth achieved.

Methodology

Our goal is to illustrate the potential of using ANT to redefine and reconceptualise journalistic truth. To elaborate and exemplify our arguments, a plausibility probe case study in investigative journalism is used. According to George and Bennett Citation2005), plausibility probes are a type of (preliminary) case study focused on relatively untested theories and hypotheses to determine whether more intensive, laborious testing is warranted. Therefore, our aim is not to formulate a conclusive argument on journalistic truth but to explore and emphasise the potential application of ANT in journalism studies to help redefine truth. Furthermore, we also offer an attempt to develop a graphical notation to visualise the news-making process under scrutiny.

In this study, the making of a single news article (from the very first moment a journalist start to collect information to the final publication of a news) represents our complex unit of analysis and the focus of our investigation. Ethnographic methods (e.g., interviews and shadowing, but also artefact analysis) are used to inform the case. Specifically, news-making reconstruction in-depth interviews are used as they records — retrospectively — the ways in which news becomes “news’ (Reich and Barnoy Citation2020). This method is selected for its ability to produce a macro picture of the process and uncover journalists’ selection of sources and development, which is otherwise difficult to capture by studying the published output or by directly observing their practices.

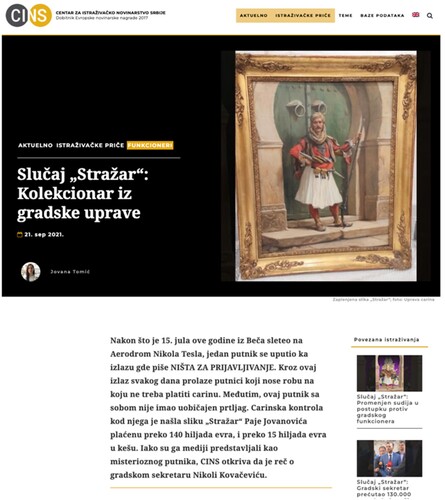

The case involves an investigative journalist, Jovana Tomić, from the Centre for Investigative Journalism of Serbia (CINS), who published an article on cins.rs in September 2021. The article is about an individual working in the Belgrade municipality who allegedly attempted to smuggle a valuable painting and an illegal sum of money through the airport in July 2021. The in-depth interviews of news-making reconstruction with the journalist took place in April 2022.

The “Guardian” Case: An Overview

On 16 July 2021, the official website of the Customs Administration of the Republic of Serbia (CARINA) reported an attempt to illegally import a valuable painting named The Sentient, by Paja Jovanović (see ). Serbian news channels also reported on this incident. However, none of them revealed the perpetrator’s identity, referring only to “a Belgrade citizen”. The deputy mayor of Belgrade posted on Facebook later that day, expressing happiness that the painting had ended up in the city and revealing the municipality's earlier intention to purchase it. (See ). The journalist launched an investigation after the post and sent a Freedom of Information (FOI) request to CARINA for details on the perpetrator. Her two-month investigation revealed suspicious aspects of the incident and potential corruption in the lawsuit, which she detailed in an article published on 21 September (see ).

Figure 1. The Serbian Customs Administration’s official website first reported on the painting without mentioning the name of the perpetrator. (Source: www.carina.rs).

Figure 2. The deputy mayor’s Facebook post about the painting. (Source: www.facebook.com/Goran.Vesic.zvanicna.stranica).

Figure 3. A screenshot of the final news article. (Source: www.cins.rs).

Black-Boxing “the Guardian”

shows the final news article published by the journalist on the CINS website. Our first move is to look at that news as a black box, which is a result of heterogenous actors being drawn together to act as one. In this case, we have a black box news ready to be consumed with no reason to question how it was “assembled together”. Its truthiness is a result, never a starting point. As Latour (Citation1988b) explains “A sentence does not hold together because it is true, but because it holds together, we say that it is “true.” What does it hold onto? Many things. Why? Because it has tied its fate to anything at hand that is more solid than itself. As a result, no one can shake it loose without shaking everything else” (pg.186). To elaborate on this idea, we will now describe how the news article in became a black box, or how this news is tied “to many things at hand that is more solid than itself” so to became a truthful news.

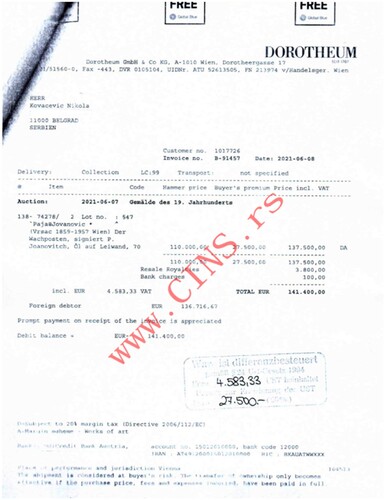

Consider one of the article’s opening sentences: “CINS can reveal that the passenger in question is a Belgrade city administration secretary, Nikola Kovačević”. Though the statement may seem to be a simple arrangement of a few words, the journalist had to work hard to be able to make such a claim, or “to tie the fate of the sentence to many solid things’. According to the journalist, she sent two FOI requests at the start of her investigation to determine the details of the incident, the first to CARINA and the second to the Misdemeanour Court of Belgrade. However, CARINA declined her request and only the Misdemeanour Court replied via an email. The email had an attachment containing all the documents related to the case, ranging from scanned copies of invoices to scanned copies of the official’s passport (see ). However, vital details in these documents (such as personal addresses, email addresses and contact numbers) were censored, except for the name of the perpetrator and his photo on the copy of his passport. Recalling the incident, the journalist said: “After going through the documents, I said to my editor that I got all the documents but at the same time I know nothing about this person except his name”. She was presented with the challenge of finding out more about Kovačević. She first attempted to search for his name using Google and on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, which gave hundreds of search results related to all the Nikola Kovačevićes on the internet. However, one Google search included an image from a Belgrade City Council press release which matched the face on the passport, and the image description contained the same name. The image description revealed that the perpetrator worked as a secretary for the Belgrade City Council. With this new information about his occupation as a public service officer, she moved her investigation from Google to the Serbian open database of public officers.

Figure 4. One of the scanned documents received after a FOI request to the Misdemeanour Court. (Source: www.cins.rs).

This action of finding the person in question using Google may seem so uncomplicated and obvious that it is easy to overlook the multitude of actors coming together. Here, a journalist who only knew the legal name of a person and their appearance saw the same face and same name on an official website of the Belgrade City Council now assumed that she had found the person about whom she had thought she knew “nothing”. In terms of ANT, Nikola Kovačević (the person) is not just a biological body, but an actor resulting (emerging) from many other actors and networks, such as his legal name, biological body, occupation, education, family relationships and even the incident with the painting. The journalist was attempting to find parts of this larger network reality of “Nikola Kovačević” to investigate the incident. Latour explained and exemplified the process of knowing (talking about) an actor as follows: “A marine biologist, a fisherman and a tribal elder are telling myths about ichthian deities. All of them talk about a fish, yet none of them really (fully) knows what a fish is. To talk about fish, all must negotiate with the fish’s reality, remaining alert to its hideouts, migration patterns, skeleton and sacral or nutritional properties” (Harman Citation2009b). Similarly, by searching on the internet and by moving from Google to a Serbian database, the journalist was negotiating Nikola Kovačević’s network reality. Earlier, the journalist’s negotiation with the two actors (his legal name and biological face) were limited (isolated); therefore, it was not sufficient to talk about the perpetrator. The superposition of old actors with the new actors (the website image) opened a larger reality regarding Nikola Kovačević. Now, the journalist knew where to look for more information about this person, namely the Serbian open database of public officers.

Consequently, she began searching the Serbian open database of public servants to eventually find Nikola Kovačević’s office telephone number, salary details, wealth declarations and business partnerships. Particularly, one of these business partnership documents included his home address and contact details. Based on this new information, she went to his address to observe his house from the outside and to confirm the address. She also called his home phone, which was answered by a child. In the absence or ineffectiveness of these actors, the journalist's investigation would have come to a standstill, with no means to locate Nikola Kovačević, had any attempt been made to eliminate any of the involved actors, tamper with the server hosting the Serbian open database, manipulate Google's search algorithm, distort the image quality on the Belgrade City Council website, or corrupt the bureaucratic system or personnel of the Misdemeanor Court. However, all actors were well aligned and drawn together, enabling the journalist to confidently write the sentence: “CINS reveals that the passenger in question is a Belgrade city administration secretary, Nikola Kovačević”. Echoing Latour’s words, the sentence above, a black box, is true because it is linked to many strong actors. If one wants to “shake” the truthfulness of the sentence, one needs to challenge many of the actors, such as the Misdemeanour Court’s official documents, the Belgrade City Council press release, Google, local databases, the reliability of Serbian telecommunication networks and even the human vision of the journalist.

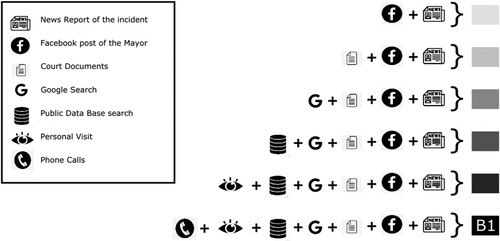

In this sense, the work of the journalist — who draws things together and connects and aligns them — progressively develop chains of associations between heterogenous actors which, at some point, are strongly tied enough to act as one (statement in this case). visualises this gradual process of forming chains of association between heterogeneous actors forming a black box. All the actors mentioned above (each of which contributed to the truthful final sentence mentioned above) have been allocated a symbol. The grayscale tone of the righthand square symbolises the strength of the black box and depicts how the chain gradually reaches this status, namely, the point where no further association is required. In this sense, the black box (B1) which claims the identity of the perpetrator is well formed and ready to be used as a single actor. All the progressively associated actors are disappearing in this black box. Chains looks at how these are aligned (+), black box refers to the product of such alignment.

While B1 was being created, the journalist had also started to build another black box in the background. This involved determining whether Nikola Kovačević had the financial capacity to buy the painting while earning a relatively low salary. Once again, she negotiated with different actors (in this case, including the Serbian Anti-Corruption Database, government salary details, the real-estate register and the perpetrator’s home architecture) to build another black box. It is important to mention here that although these black boxes are discussed consecutively for the purpose of explaining, they were actually being built simultaneously. When explaining her visit to the perpetrator’s home address, she said: “Once I had found his residential address in an old business contract under his name, I paid the location a visit. I was not planning to knock on his door, because at that stage of the investigation I did not have enough information to interview him. I just wanted to confirm the address and to check his living status’.

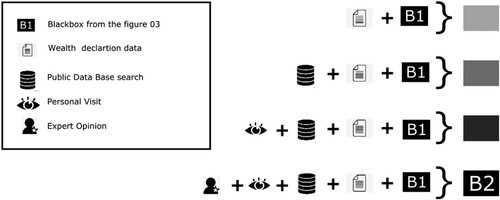

Continuing the investigation, the journalist spoke to an anti-corruption expert from the organisation Transparency Serbia. She discussed her findings with him, and during this discussion, he mentioned “the whole situation is strange”, while explaining why he found it strange. Here, the journalist changed her way of negotiating with the networks. Instead of comparing numbers and signs via computer or by personally visiting the perpetrator’s house, she presented all her findings (actors and their associations) and invited an expert to comment on them. This expert’s opinion thus became another actor — in the form of a written interview extraction — in the chain, which was aligned with other heterogenous actors to create a new black box (B2). This new black box refers to the truth about the “strangeness or dubious nature of the incident” (see ).

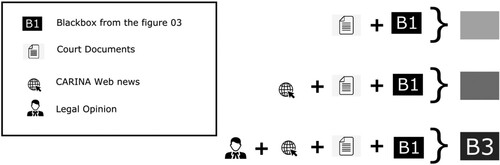

Next, the article mentions an illegal sum of money: “In addition to the precious painting, at the airport Kovačević was also found to be carrying €15,550 in cash. Since the permitted amount that can be taken across the border without being declared is €10,000, The Sentinel and €5,550 were confiscated, to be kept until the case is solved”. These words refer to an action by Kovačević on the day of the incident, as well as the legal aspect of the case. First, the journalist read about these legal particulars in the detailed news article published on the official website of CARINA about the incident, and they were also mentioned in the documents she had received from the court. Apart from dealing with these words and signs, once again she had involved another (human) actor, who was a lawyer. “We have a lawyer we often refer to for legal advice related to our investigation and he confirmed these misconducts and possible penalties,” she said. As with the previous two black boxes, here the journalist had built another black box (B3) regarding the amount of illegal money in the case. This chain also translated into a truthful statement (a black box) which was stronger and unshakeable due to the solid alignment of convincing actors such as lawyers, court documents and official statements from the Serbian government (see ) which, again, are all disappearing in the final statement.

At a certain stage, she decided to reach out to Nikola Kovačević for an interview. This was to further investigate the case and “to give him an opportunity to express his side of the story”. After a few attempts, she managed to convince him to agree to speak to her. This interview was a test for the black boxes, a test to check the strength of the association these chains made between heterogenous actors. It could also be an opportunity for Nikola Kovačević to questions the making of black box, open them, tear them, and send the journalist back to the beginning of the investigation by destroying all her progress. According to her, the black boxes were not torn open, and they passed the test: “I think he did not expect me to be that thorough in my investigation, but my findings were solid by that time, and I had clear questions’. Here, the same journalist who once said she knew nothing about Nikola Kovačević was now interrogating him by presenting her well-formed black boxes which he himself struggled to tear open. Interestingly, the journalist never witnessed the incident and never saw him physically but solely relied on her journalistic work and her making of solid chains or well-formed black boxes to question him.

Not only did Kovačević fail to break these associations, but during the interview, he strengthened the black boxes by adding more actors, namely making contradictory statements. At one point, he claimed they were a family of art collectors but later he mentioned that he never knew the process of legally importing an art piece. Likewise, while attempting to prove his innocent intentions, he stated: “My intention was like when you’re coming to Egypt and bringing parts of a pyramid and you say, My dear country, here, I’ve brought parts of a pyramid from another country”. Regarding this moment of the interview, the journalist said: “At that moment, I wrote “Egypt” in my notebook and marked the rough timecode of the interview. I knew it was an interesting and ironic statement”. Later, she used this statement by Kovačević at the beginning of the final news article. Here, it could be said that she was linking more actors to her previous black boxes, making them more and more difficult to tear open; thereby, making it difficult to challenge her claim of “something [being] wrong” with this incident. In this case, the actors are extracts from her interview with Kovačević in the form of words and sentences. These actors not only contributed to B2, but they are also chained to B1, which identified Kovačević as being involved in this incident. When Kovačević did not deny his involvement but expressed his innocence, each statement contributed to strengthening the first black box (B1).

Once the final interview was complete, the journalist prepared a draft of the final news article and sent it to the fact-checker. This is a member of the CINS team whose responsibility, according to the journalist, is to take a fresh look at the article and check the work by cross analysing the sources, the method of acquiring data and how it has been presented. This represents another test for the black boxes, as the fact-checker might suggest removing, rewriting, or adding sentences. This is another precaution to reduce the opportunity for others to tear open or question the black box. Meanwhile, the journalist and the chief editor selected the cover photo to accompany the article: “We used the painting as the main photo, because nobody knew about this person, but everyone knows about the painter and this painting”. When everything was finalised, the final black box had been created (see ). In the final illustration, an additional symbol was used to represent “many other actors’ who were either not discussed here or not revealed during the data collection process. As a collective attempt to chain together all these heterogenous actors (see ), including the hidden actors of earlier black boxes which are now seen as part of a single opaque actor, the final black box has been created. It can be equated to the final single actor (the truthful news) shown in . Each of these actors (databases, phone calls, experts, scanned documents, and so forth) are concrete parts of the black box. Following Latour, we say, none of these features can be scraped away like an ornamental feature of the news or like an unwanted cobweb. All features belong to the black box, the journalistic chain itself speaking the truth: “a force utterly deployed at any given moment, entirely characterised by its full set of features” (Harman Citation2009b).

Discussion

Latour, in his work on soil scientists in Amazon Forest, invites us to “slow our pace a bit and set aside all our time-saving abstractions” if we want to rethink scientific knowledge (Latour Citation1999, 24). In a similar vein, our case study helps to encourage scholars of journalism to adopt a similar slower approach by taking the time to establish a robust foundation for rethinking journalistic truth. Our two propositions, Blackbox and journalistic chains, contribute to this endeavour by enabling us to carefully build a detailed and empirically grounded inventory of journalism, free from category mistakes, bifurcation, or purification. The traditional abstractions of journalistic truth, which initially seen through subjectivity and objectivity or a fusion of the two, can now be seen as an entirely different phenomenon, encompassing black-boxing and journalistic chains, as revealed by our case study. For us, this represents a contribution to the epistemology of journalism toward untapped potentials of ANT in understanding (empirically as well as philosophically) news-making and journalistic truth.

Particularly our approaches allow us to bring symmetry and diplomacy into truth inquiry in journalism studies. It allows us to become agnostic to different journalism genres, different times, different actors and forces influencing journalistic truth including technology, and without falling into the object/subject divide or in assumptions (theoretical) about what counts in news-making. Once the news is defined and investigated as a black box, all types of news are included in the definition, whether it is a hard or opinion-based, whether we are dealing with a historical case in traditional media or data-journalism permeated with digital media, whether it appeals at the value of scientific evidence or to any other value like advocacy, politics or religion. Such agnostic investigation allows us to dive headfirst into the chaos of dynamics of journalism (Deuze and Witschge Citation2018). Winking at Latour masterpiece “we never been modern”, we can say that “we (journalists) never reported facts’, not because journalistic truth is not about facts, but because the journalistic truth of facts that ends up in news is a Blackbox and it is rather achieved (not given or transported) by the messy establishment of journalistic chains made of heterogeneous material through which news can emerge and reach their audiences. Yet, the contribution of this renewed and slowed-down account of new-making is only partial. Saying that everything is a network, a black box or a chain fails to fully capture what exactly is unique about news-making, how the journalistic chains are specifically made, and what precisely is being black boxed in journalism. The questions posed here represent a second contribution of this work. Once again, Latour's more recent works offer valuable guidance in formulating answers. Turning upside down 40 years of research telling us what we are not (we are not modern, we are not pure objects or subjects, nature or culture), Latour latest project was that of finding a positive and affirmative way of defining modernity for what it is, a way of, in Latour words, “speaking well to one’s interlocutors about what they are doing—what they are going through, what they are—and what they care about.”(Latour Citation2013, 64). This project takes the name of “an inquiry into modes of existence” where our notion of network and of chains, but also what we called the regimes of science, or law, religion, are all becoming distinct “modes of existence” through which our modern society produces knowledge and truth (Latour Citation2013). This positive framing, the “anthropology of moderns,” opens up the possibility of interrogating journalism as a mode of existence and asking empirically sound and novel questions about journalistic truth. In this sense news-making as black-boxing journalistic chains becomes (only) a first key step toward “speaking well” about journalism (beyond using ANT to merely deconstruct or to make a category mistake) and empirically find ways to answers more specific questions about how journalistic chains are built, what exactly “circulate” in these chains, what discontinuities are allowed from one passage to another to maintain a certain “journalistic” (not subjective, objective, political, scientific, or cultural) continuity, how these chains cross with other chains from other regimes, and so on. In other words, our intention is to backtrack a step from Marine & De Maeyer's suggestion of regarding journalistic truth as a product of “references.” Instead, we aim to raise specific questions about journalistic truth itself. Although we do not currently present a definitive alternative to the concept of reference, our argument posits that perceiving new-making as progressive black-boxing and viewing journalistic truth as emerging from the establishment of journalistic chains opens up avenues for novel perspectives and inquiries regarding journalistic truth. This approach is grounded in empirical evidence and informed by ethnographic insights, providing a theoretical and methodological framework capable of addressing demands for an alternative theory for the epistemology of journalism. It allows for a more cautious and diplomatic account of journalistic truth, transcending genres, time periods, and mediums.

Conclusion

In this work, we argued that ANT has much to contribute to the current debates and theoretical demands in the epistemology of journalism. We argued and used a case study to illustrate news-making as black boxing and offer a view of journalistic truth as emerging from the (laborious) establishment of journalistic chains made of heterogeneous materials and associations. As Latour describes his lifelong research, it is a systematic empirical philosophy to offer modernist a different representation of themselves (may it be scientists, lawyers, engineers, economists or fictional writers), a descriptions that would not crush their values to the benefits of the others (Latour Citation2010a; Citation2013). Hence our two proposition paves the way for epistemology of journalism to offer an alternative representation that would not crush values in journalism to the benefits of the science, or politics, or technology, while fulling ambitious demands of an alternative theory in the epistemology of journalism. The work to do is only at the beginning though, as we acknowledge this paper has led to more specific questions about the networks, black boxes, and the chains we identified. This will hopefully lead to a more extensive and mature inquiry into today’s journalism and journalistic “truth” as one of the “modes of existence” in our modern life and societies.

Ethics Statement

The human subject interview was conducted in April 2022 under the informed consent of the participant. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Science Faculty, University of Limerick.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alderhill. 2021. “BBC news registration? - Telecoms & TV - Toytown Germany.” https://www.toytowngermany.com/forum/topic/389695-bbc-news-registration/#comment-3867835.

- Stuart, Allan. 2006. “News, Truth and Postmodernity: Unravelling the Will to Facticity.” In Theorizing Culture An Interdisciplinary Critique After Postmodernism, edited by Barbara Adam and Stuart Allan, 147–162. London: Routledge.

- Ananny, M., and K. Crawford. 2018. “Seeing Without Knowing: Limitations of the Transparency Ideal and its Application to Algorithmic Accountability.” New Media & Society 20 (3): 973–989. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816676645.

- Anderson, C. W., and M. Schudson. 2019. “Objectivity, Professionalism, and Truth Seeking.” In The Handbook of Journalism Studies (2nd ed.), edited by K. Wahl-Jorgensen and T. Hanitzsch, 136–151. New York, NY: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315167497-9.

- Berger, P. L., and T. Luckmann. 1991. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge (Repr. in Penguin Books). London: Penguin Books.

- Bloor, D. 1991. Knowledge and Social Imagery. 2nd Edition. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Broersma, M. 2010. “The Unbearable Limitations of Journalism: On Press Critique and Journalism’s Claim to Truth.” International Communication Gazette 72 (1): 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048509350336.

- Callon, Michel, and Bruno Latour. 1981. “Unscrewing the Big Leviathan: How Actors Macro- Structure Reality and How Sociologists Help Them To Do So.” In Advances in Social Theory and Methodology: Toward an Integration of Micro- and Macro-Sociologies, edited by Karin Knorr Cetina and A.V. Cicourel, 277–303. Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Coddington, M. 2015. “Telling Secondhand Stories: News Aggregation and the Production of Journalistic Knowledge Committee” PhD diss., Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The University of Texas at Austin]. https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/32174.

- Curry, A. L., and N. J. Stroud. 2021. “The Effects of Journalistic Transparency on Credibility Assessments and Engagement Intentions.” Journalism 22 (4): 901–918. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884919850387.

- Deuze, M., and T. Witschge. 2018. “Beyond Journalism: Theorizing the Transformation of Journalism.” Journalism 19 (2): 165–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884916688550.

- Domingo, D., P. Masip, and I. C. Meijer. 2015. “Tracing Digital News Networks: Towards an Integrated Framework of the Dynamics of News Production, Circulation and use.” Digital Journalism 3 (1): 53–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2014.927996.

- David D., and V. Wiard. 2016. “News Networks.” In The SAGE Handbook of Digital Journalism, edited by Tamara Witschge, C. W. Anderson, David Domingo, and Alfred Hermida, 397–409. SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Ekström, M., and O. Westlund. 2019. “Epistemology and Journalism.” In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Journalism Studies, edited by Henrik Örnebring. New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.806.

- Ericson, R. V. 1998. “How Journalists Visualize Fact.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 560 (1): 83–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716298560001007.

- Ettema, J., and T. L. Glasser. 1984, August 1. “On the Epistemology of Investigative Journalism.” https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/On-the-Epistemology-of-Investigative-Journalism.-Ettema-Glasser/2685b5e92bba38ec670729de40c36fbba37040a9.

- Farkas, J., and J. Schou. 2019. Post-Truth, Fake News and Democracy: Mapping the Politics of Falsehood. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Gaitano, N. G., E. López-Escobar, and M. Martín Algarra. 2022. “Walter Lippmann’s Public Opinion Revisited.” Church, Communication and Culture 7 (1): 264–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/23753234.2022.2042344.

- George, A. L., and A. Bennett. 2005. Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

- Godler, Y., Z. Reich, and B. Miller. 2020. “Social Epistemology as a new Paradigm for Journalism and Media Studies.” New Media & Society 22 (2): 213–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819856922.

- Graves, L. 2016. “Anatomy of a Fact Check: Objective Practice and the Contested Epistemology of Fact Checking.” 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/cccr.12163.

- Hall, S. 1973. “Encoding and Decoding in the Television Discourse.” Centre for contemporary cultural studies.

- Harman, G. 2009a. Prince of Networks : Bruno Latour and Metaphysics. In Re.press.

- Harman, G. 2009b. Prince of Networks : Bruno Latour and Metaphysics. In Re.press.

- Hearns-Branaman, J. O. 2018. Journalism and the Philosophy of Truth: Beyond Objectivity and Balance (First Issued in Paperback). New York, London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Hemmingway, E. 2005. “PDP, The News Production Network and the Transformation of News.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 11 (3): 8–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/135485650501100302.

- Latour, B. 1988. Science in Action How to Follow Scientists and Engineers through Society. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Latour, B. 1996. Aramis, or, The Love of Technology. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Latour, B. 1999. Pandora’s Hope: Essays on the Reality of Science Studies. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Latour, B. 2004. Politics of Nature -How to Bring the Sciences Into Democracy. Cambridge: In Harvard University Press.

- Latour, B. 2010a. “Coming out as a Philosopher.” Social Studies of Science 40 (4): 599–608. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312710367697.

- Latour, B. 2010b. On the Modern Cult of the Factish Gods. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Latour, B. 2013. An Inquiry Into Modes of Existence. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. http://www.elsevier.com/locate/scp.

- Latour, B., and C. Porter. 2017. Facing Gaia: Eight Lectures on the new Climatic Regime. Medford, MA: Polity.

- Lau, R. W. K. 2004. Critical Realism and News Production. Media, Culture & Society 26 (5): 693–711. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443704045507.

- Law, J. 2007. “Actor Network Theory and Material Semiotics 1.” http://www.

- Maras, S. 2012. Objectivity in Journalism. Malden, MA: Polity Press.

- Martine, T., and J. De Maeyer. 2019. “Networks of Reference: Rethinking Objectivity Theory in Journalism.” Communication Theory 29 (1): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qty020.

- Molotch, H., and M. Lester. 1974. “News as Purposive Behavior: On the Strategic Use of Routine Events, Accidents, and Scandals.” American Sociological Review 39 (1): 101–112. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094279.

- Muñoz-Torres, J. R. 2007. “Underlying Epistemological Conceptions in Journalism: The Case of Three Leading Spanish Newspapers’ Stylebooks.” Journalism Studies 8 (2): 224–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700601148838.

- Muñoz-Torres, J. R. 2012. “Truth and Objectivity in Journalism: Anatomy of an Endless Misunderstanding.” Journalism Studies 13 (4): 566–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2012.662401.

- Pantumsinchai, P. 2018. “Armchair Detectives and the Social Construction of Falsehoods: An Actor–Network Approach.” Information Communication and Society 21 (5): 761–778. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1428654.

- Primo, A., and G. Zago. 2015. “Who and What do Journalism?: An Actor-Network Perspective.” Digital Journalism 3 (1): 38–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2014.927987.

- Prochazka, F., and M. Obermaier. 2022. “Trust Through Transparency? How Journalistic Reactions to Media-Critical User Comments Affect Quality Perceptions and Behavior Intentions.” Digital Journalism 10 (3): 452–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.2017316.

- Reich, Z., and A. Barnoy. 2020. “How News Become “News” in Increasingly Complex Ecosystems: Summarizing Almost Two Decades of Newsmaking Reconstructions.” Journalism Studies 21 (7): 966–983. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2020.1716830.

- Romano, C. 1986. “What? The Grisly Truth About Bare Facts.” In Reading the News: A Pantheon Guide to Popular Culture (1st ed), edited by R. K. Manoff, and M. Schudson, 38–78. Pantheon Books.

- Rosen, J. 1993. “Beyond Objectivity.” In Nieman Reports.

- Rupar, V. 2006. “Reflections on Journalism and Objectivity: An Episode, Ideal or Obstacle.” MEDIANZ: Media Studies Journal of Aotearoa New Zealand 9 (2): 12–17. https://doi.org/10.11157/medianz-vol9iss2id76.

- Stalph, F. 2019. “Hybrids, Materiality, and Black Boxes: Concepts of Actor-Network Theory in Data Journalism Research.” Sociology Compass 13 (11): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12738.

- Steiner, L. 2018. “Solving Journalism’s Post-Truth Crisis With Feminist Standpoint Epistemology.” Journalism Studies 19 (13): 1854–1865. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2018.1498749.

- Tuchman, G. 1980. “Making News: A Study in the Construction of Reality (First Free Press paperback ed).” Free Press [u.a.].

- Turner, F. 2005a. “Actor-Networking the News.” Social Epistemology 19 (4): 321–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/02691720500145407.

- Turner, F. 2005b. “Where the Counterculture Met the New Economy: The WELL and the Origins of Virtual Community.” Technology and Culture 46 (3): 485–512. https://doi.org/10.1353/tech.2005.0154.

- Uscinski, J. E., and R. W. Butler. 2013. “The Epistemology of Fact Checking.” Critical Review 25 (2): 162–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/08913811.2013.843872.

- Wahl-Jorgensen, K. 2016. “Is There a ‘Postmodern Turn’ in Journalism?” Rethinking Journalism Again: Societal Role and Public Relevance in a Digital Age, 97–111. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315716244.

- Wahl-Jorgensen, K., and T. Hanitzsch. 2009. “Introduction: On why and how we Should do Journalism Studies.” In The Handbook of Journalism Studies, edited by K. Wahl-Jorgensen and T. Hanitzsch, 3–16. New York, NY: Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203877685-8.

- Waisbord, S. (2008). Advocacy Journalism in a Global Context. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203877685.CH26

- Ward, S. 2018. “Epistemologies of Journalism.” In Journalism, edited by T. P. Vos, 63–82. Berlin: De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781501500084-004.

- Weiss, A. S., and D. Domingo. 2010. “Innovation Processes in Online Newsrooms as Actor-Networks and Communities of Practice.” New Media and Society 12 (7): 1156–1171. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444809360400.

- Wien, C. 2017. “Defining Objectivity Within Journalism.” Nordicom Review 26 (2): 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1515/nor-2017-0255.

- Witschge, T., C. W. Anderson, D. Domingo, and A. Hermida. 2019a. “Dealing with the Mess (we Made): Unraveling Hybridity, Normativity, and Complexity in Journalism Studies.” Journalism 20 (5): 651–659. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884918760669.

- Witschge, T., C. W. Anderson, D. Domingo, and A. Hermida. 2019b. “Dealing with the Mess (we Made): Unraveling Hybridity, Normativity, and Complexity in Journalism Studies.” Journalism 20 (5): 651–659. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884918760669.

- Wölker, A., and T. E. Powell. 2021. “Algorithms in the Newsroom? News Readers’ Perceived Credibility and Selection of Automated Journalism.” Journalism 22 (1): 86–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884918757072.