ABSTRACT

The increasing reliance on social media as a source of news, particularly among adolescents, raises important questions for democracy regarding the potential of these platforms to promote engagement with politics. This study sought to examine adolescents’ affective (emotions, feelings), behavioural (actions and issue-specific interest), and cognitive (issue-specific knowledge) responses to political news on Instagram Stories. We conducted a field experiment among adolescents in the Netherlands (N = 149). We exposed respondents for seven days to political news items from fictive news organizations. Respondents received either (i) Stories with a link to a news item or (ii) Stories with a link to a news item and interactive feedback features (i.e., polls, quiz stickers, and emoji sliders). The results showed no significant differences in affective, behavioural, and cognitive responses between adolescents who have been exposed to Instagram Stories with high interactivity compared to those who received a link to a news item, indicating that interactivity had no effect on these responses. The results indicate that political interest increased for all respondents throughout the experiment—irrespective of the interactivity of the Instagram Stories. This possibly indicates that exposure to political news through Instagram Stories fosters engagement with politics and current events among adolescents.

Social media journalism has become an important part of contemporary journalism, with many news organizations increasingly using social media platforms (e.g., TikTok, YouTube, Facebook) to produce and distribute news content. One platform that has seen significant increase in its use for news production and consumption is Instagram, particularly among younger people. With over one billion monthly active users, Instagram use for news has nearly doubled since 2018, thereby overtaking Twitter, particularly among younger generations (Newman et al. Citation2022). As a result, many news organizations are trying to attract a younger audience by actively sharing news on Instagram. In the Netherlands, for example, the online news service of the Dutch public broadcaster NOS has an Instagram channel, known as @nosstories, to inform Dutch adolescents between the ages of 13 and 18. They have nearly one million followers at the time of writing. Similarly, in other countries, broadcasters such as VRT in Belgium (@nws.nws.nws) and CBC in Canada (@cbckidsnews) have Instagram channels that aim to inform and engage young audiences. In this way, social media platforms such as Instagram could provide new and interesting ways for young citizens to connect with politics and current affairs.

The widespread use of Instagram and other social media platforms for news provides ample opportunities to encourage active engagement with the news, particularly through the visual and interactive features of such platforms (Hase, Boczek, and Scharkow Citation2022). With Instagram, and in particular its Stories, journalists can include interactive elements such as question stickers and polls in their news stories to encourage users to respond or reflect on a news topic, with responses updated in real time, which could further enhance the potential of social media in the process of (political) learning among young people.

Yet, there are only a limited number of studies examining the use of Instagram for news. For instance, Vázquez-Herrero, Direito-Rebollal, and López-García (Citation2019) conducted a quantitative content analysis to examine how different news organizations in various countries use Instagram Stories. More recently, Hendrickx (Citation2021) combined interviews and a quantitative content analysis to examine the news production and content of @nws.nws.nws (i.e., a popular Instagram channel targeting teenagers in Belgium). To date, there is no experimental evidence and therefore little knowledge about the effects of Instagram use for news on political behaviour and attitudes among young adults. In this study, we will therefore focus on the question: To what extent can interactive Instagram Stories facilitate learning about politics and current events among Dutch adolescents? More specifically, we examine affective (i.e., emotions, feelings), behavioural (i.e., actions and issue-specific interest), and cognitive (i.e., issue-specific knowledge) responses to interactive Instagram Stories.

We conducted an online field experiment based on the research design of Vermeer et al. (Citation2021). In our field experiment, participants between the ages of 12 and 18 (N = 149) followed Instagram Stories from a fictitious news organization for seven days and received daily either (i) Stories with a link to a news item or (ii) Stories with a link to a news item and interactive feedback features (i.e., polls, quiz stickers, and emoji sliders). We focus particularly on young news consumers as they often turn to Instagram for news (Newman et al. Citation2022), and their political interest is still developing (Neundorf, Smets, and García-Albacete Citation2013). Since adolescents tend to be less involved in politics and current events than older adults (Neundorf, Smets, and García-Albacete Citation2013), Instagram could serve as a resource to engage adolescents in politics and current events.

We contribute to the literature in two important ways. First, we aim to shed light on how adolescents respond to political news on Instagram Stories. Since people, especially younger generations, are informed through social media, they may be exposed to news incidentally, regardless of their willingness to be informed about political and current events (Fletcher and Nielsen Citation2018a). Second, existing research on the use of Instagram for news has relied on quantitative content analysis or interview methods (Hendrickx Citation2021; Vázquez-Herrero, Direito-Rebollal, and López-García Citation2019). By conducting an experimental study among adolescents, we aim to provide an empirical exploration of the democratic implications of the increasing popularity of Instagram Stories, such as political interest and political learning. In addition, this study aims to provide insights for news organizations to understand whether, and if so, how they can use Instagram Stories to increase engagement with politics and current events among younger generations. Adolescents are a critical audience for news organizations around the world, and for the sustainability of the news, but they are increasingly difficult to reach and may require different strategies to engage them (Eddy Citation2022).

News Production and News Consumption on Social Media

Social media platforms have become an important part of the news ecosystem, fundamentally changing the way journalistic content is produced, shared, and consumed (Humayun and Ferrucci Citation2022; Vázquez-Herrero, Direito-Rebollal, and López-García Citation2019; Weaver and Willnat Citation2016). News organizations are now using platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok to engage and connect with their audiences, particularly younger groups of citizens (Galan et al. Citation2019). Social media can be used to get feedback from the audience (e.g., user comments, see e.g., Ksiazek Citation2018; Reimer et al. Citation2021; Trilling Citation2015; Ziegele, Breiner, and Quiring Citation2014). Furthermore, social media platforms are increasingly being used to share news stories, with previous research highlighting their suitability for providing information on current affairs in real time (see e.g., Neuberger, Nuernbergk, and Langenohl Citation2019; Thurman and Newman Citation2014; Vis Citation2013), and to attract attention to traditional news content or news organizations’ websites or apps (see e.g., Ju, Jeong, and Chyi Citation2014; Larsson Citation2018; Vermeer et al. Citation2020). News organizations and journalists also use social media as an online source to gather background information on breaking stories (see e.g., Lecheler and Kruikemeier Citation2016), gauge public opinion (McGregor Citation2019), expand their network (see e.g., Verweij and Van Noort Citation2014), identify eyewitnesses (see e.g., Andén-Papadopoulos and Pantti Citation2013), and collect multimedia content (i.e., pictures and videos; Allan and Peters Citation2015; Kristensen and Mortensen Citation2013).

News organizations and journalists face the challenge of managing multiple social media platforms simultaneously (Hassan and Elmasry Citation2019), raising the question of whether different types of social media are used for different purposes (see e.g., Hermida and Mellado Citation2020). In a study of 105 editors-in-chief in German newsrooms, Neuberger, Nuernbergk, and Langenohl (Citation2019) analyzed the profiles of different social media and newsroom strategies. The study found that Facebook and Twitter were used for multiple journalistic purposes, such as sharing breaking news, contacting elite sources, and obtaining background information, while YouTube was used for more specific journalistic purposes (e.g., publishing videos).

The integration of social media into the news ecosystem has not only changed the way news is produced but also influenced the way people consume and connect with and are affected by news (Kümpel Citation2022). Younger groups of citizens are increasingly and predominantly using social media to get informed about the world around them (Galan et al. Citation2019). For instance, previous research in the Netherlands has shown that although a large share of young adults turn to traditional media for news consumption, a growing number of adolescents (51 percent; Newman et al. Citation2022) use social media platforms, such as Instagram and YouTube, to consume news (Geers Citation2020).

According to previous work, adolescents have four motivations for turning to social media (see e.g., Romero Saletti, Van den Broucke, and Van Beggelaer Citation2022; Throuvala et al. Citation2019). Besides satisfying adolescents’ need for connection (i.e., keeping in touch with friends and family), need for entertainment (i.e., watching entertaining and funny content), and need for inspiration (e.g., watching dance videos to learn new choreography), adolescents use social media when they are in need for information. In a recent study, van der Wal, Valkenburg, and van Driel (Citation2022) used a qualitative approach to understand individual differences in adolescents’ motives for social media use, their social media-related mood management, and the effects of social media use. Relying on eight focus groups with 55 Dutch adolescents between the ages of 14 and 17, they find considerable homogeneity in young people’s motives for turning to social media. Their results confirm that the need for information is one of the main reasons for adolescents to use social media platforms, such as Instagram.

Yet, news consumption patterns of young adults are increasingly shaped by incidental exposure (Boczkowski, Mitchelstein, and Matassi Citation2018). They are often directed to news that is sent, shared, or liked by their friends, family, and acquaintances and they rely on algorithms that tailor search results or sort news based on digital traces of personal data. Rather than looking for news content, adolescents may unintentionally see short news previews shared by their friends while simply browsing their feeds or messages for the latest social updates (see e.g., Fletcher and Nielsen Citation2018b). When using social media, adolescents click on news items only sporadically and spend little time engaging with the content (Boczkowski, Mitchelstein, and Matassi Citation2018). As a result, their news consumption can be defined to be predominantly passive, possibly due to a lack of intrinsic motivation (Tamboer, Kleemans, and Daalmans Citation2022).

Instagram’s Visual and Interactive Affordances

With Instagram becoming more popular over the past years, many news organizations have turned to this platform (Newman Citation2022). Instagram offers news organizations specific affordances, most importantly the immersive features of visuality and interactivity (Hermida and Mellado Citation2020). Revolving around instant snapshots to capture moments, Instagram is primarily a visual platform (Al Nashmi Citation2018; Hermida and Mellado Citation2020; Perreault and Hanusch Citation2023). The emphasis on visual content sets Instagram apart from other social media platforms, such as Twitter, which prioritizes textual content and is primarily used for (quick) sharing of news and links (Hermida and Mellado Citation2020). Although Instagram is known as a platform for sharing personal photos and selfies, which can generally be considered apolitical (Perreault and Hanusch Citation2023), its unique affordances for visual storytelling have made it an ideal platform for news producers to promote and communicate news content in a visually appealing way—an approach that particularly resonates with young people, who are attracted to the platform’s aesthetically driven video and photo content (Nee Citation2019).

Instagram’s visual appeal is further amplified and maximized by the platform’s introduction of new functions, most notably Instagram Stories in 2016, which opened up a wealth of opportunities for news organizations to leverage the platform’s visual potential (Vázquez-Herrero, Direito-Rebollal, and López-García Citation2019). Instagram Stories are all about sharing (unfiltered) moments of your day, in a natural, documentary style and everyday feel. What sets Instagram Stories apart is their ephemerality, with each Story lasting only 24 h (Bainotti, Caliandro, and Gandini Citation2021). These characteristics align with the narrative and momentary format of news stories. Hence, many news organizations use Stories to present information in a visually-rich and engaging format (Towner and Muñoz Citation2022; Vázquez-Herrero, Direito-Rebollal, and López-García Citation2019).

The engaging format of Instagram, and Instagram Stories in particular, owes much to the platform’s interactive functionality. By facilitating conversational interactive elements and feedback tools such as polls, quizzes, and emoji sliders, users can actively engage with both the sender and other users to communicate about the content they are viewing (Bucy and Tao Citation2007; Yang and Shen Citation2018). In the context of news consumption, this interactivity can turn passive news readers into active participants in the news experience (Deuze Citation1999; Opgenhaffen and d’Haenens Citation2011; Yang and Shen Citation2018). Each feature that Instagram offers is designed to elicit a specific response and increase engagement with the (news) content. Polls provide users with the opportunity to vote on a specific topic and express their thoughts and ideas. Quizzes enable users to test their knowledge on a particular topic, while (emoji) sliders allow them to express their opinions or feelings. The immediate processing of responses allows users to compare their own responses to others in real-time, creating a more engaging experience.

The use of Instagram Stories by news organizations has been examined by previous research, revealing how these organizations are adapting to the platform’s unique features and catering to user preferences. For example, Hendrickx (Citation2021) used a mixed-methods research design of qualitative interviews and quantitative content analysis to examine the news production and content of @nws.nws.nws, an Instagram channel maintained by the national public-service broadcaster in Flanders that targets 13–17 year olds. The findings show that the Instagram channel specifically targets its audience with news that they want or specifically ask for via comments or direct messages. Hence, for instance, political news was hardly represented on their Instagram channel—which may be even more important for adolescents whose political interest is still developing (Neundorf, Smets, and García-Albacete Citation2013). Furthermore, Vázquez-Herrero, Direito-Rebollal, and López-García (Citation2019) conducted a quantitative content analysis and a small-scale questionnaire to examine how both legacy and digital native news organizations from seven countries (such as the New York Times in the United States, El Mundo in Spain, Le Monde in France, and The Guardian in the United Kingdom) use Instagram Stories to disseminate news. Their findings indicate that news organizations are using ephemeral Instagram Stories to adapt to the platform’s affordances and user preferences. With photos and videos demonstrated as key resources in Stories that feature news, Instagram is a highly visual platform that, while similar to Facebook and Twitter in its use of content to drive users to a website, offers unique advantages for creating deeper and more specific formats, such as quizzes.

Affective, Behavioural, and Cognitive Responses to Interactive Instagram Stories

In a recent focus group study, Tamboer, Kleemans, and Daalmans (Citation2022) show that while adolescents consider news to be important, they often find it boring, repetitive, negative, and disconnected from their lives. Despite the efforts of news organizations to bridge this gap with news channels, young people often do not take their endeavours seriously. However, the study found one notable exception: the Instagram channel of the Dutch public news broadcaster, which was positively received by the majority of participants. This finding suggests that Instagram’s visual and interactive affordances may offer a solution to this problem. In this way, adolescents can be drawn to the informal, entertaining style of visual media platforms—describing them as more personalized and diverse compared to, for instance, television news Eddy (Citation2022).

As Deuze (Citation2003) notes, interactivity is a uniquely defining feature of online news engagement, and Instagram’s visual and interactive features allow journalists and news organizations to provide engaging content to attract users and encourage interaction with both content and other users (Ksiazek, Peer, and Lessard Citation2016), potentially making news consumption more interesting for young people. In other political contexts, research by Tedesco (Citation2007) shows that interactive features on political websites make young people feel more involved in the political process and believe that their opinions are valued and heard. Consistent with this, previous research has generally found that interactivity on websites has a positive effect on users’ emotional experiences and affective responses, often in the form of enjoyment (e.g., Coursaris and Sung Citation2012) and satisfaction (e.g., Sun and Hsu Citation2013). These findings were supported by a meta-analysis conducted by Yang and Shen (Citation2018). Therefore, we anticipate that interactive Instagram Stories will foster positive emotions and feelings among users.

Beyond affective responses, we turn our attention to examining behavioural responses, specifically whether individuals are motivated to seek out additional information, discuss a news topic with their peers and family, or develop a heightened interest in a news topic as a result of engaging with it through interactive Instagram Stories. The interactive and conversational nature of consuming news on social media can shape individuals’ inclination to become more politically engaged and inspire them to actively seek out information, as demonstrated by research from Gil de Zúñiga, Jung, and Valenzuela (Citation2012). More specifically, as argued above, interactive features can make young people feel more involved in the political process and believe that their opinions are valued and heard, which can instil a sense of responsibility in young people and engage them in democracy, for example by valuing voting as an important engagement activity (Tedesco Citation2007). In addition, research by Torcal and Maldonado (Citation2014) found that exposure to a variety of viewpoints in the media can lead to increased political interest and increased political engagement among citizens. The interactive feedback features of Instagram Stories, with responses updated in real time, allow users to come into contact with different perspectives, which could contribute to this effect. Overall, we expect that interactive Instagram Stories will encourage information seeking and interest in information about politics.

In addition, we expand our focus to the potential of Instagram Stories in improving information retention and knowledge acquisition. Previous studies have revealed that Instagram, as a visually dominant platform, is more effective in facilitating information recall compared to Twitter, which primarily relies on text-based content (Arceneaux and Dinu Citation2018). Additionally, interactive features have been identified in the literature as a factor that contributes to greater information efficiency by facilitating further engagement with relevant information in a meaningful and memorable way. For example, Warnick et al. (Citation2005) showed that interactive features on an online (news) site can increase the amount of time users spend on the site and their ability to recall information (i.e., specifically, in the case of their study, remembering the issue positions of political candidates). Other scholars, such as Eveland (Citation2004) and Kwak et al. (Citation2004) argue and support that (online) discussions about a (political) news topic can motivate users to engage more deeply with the information and increase their understanding and knowledge of the topic. The reasoning behind this mechanism is that talking to others (online) and sharing information and interpretations about what one has read or seen in a news story can help people understand such a topic in all its complexity (Scheufele Citation2002; Yamamoto and Nah Citation2018). Given that Instagram Stories and its interactive features allow for real-time interactions between users where they can exchange ideas and perspectives, we expect that adolescents’ will be encouraged to engage with news content and reflect on their opinions and knowledge. For example, by actively participating in question-stickers and quizzes, users are likely to think more critically about the news they consume and compare their own responses to those of others. This conscious engagement is likely to lead to a more thorough consolidation of information in long-term memory, promoting an issue-specific knowledge-building process (see for a similar argument, Opgenhaffen and d’Haenens Citation2011).

We therefore hypothesize the following:

H1: Exposure to Instagram Stories for news with interactive features (i.e., polls, quiz stickers, and emoji sliders) leads to more positive (a) affective responses, (b) behavioural responses, and (c) cognitive responses compared to exposure to less interactive Instagram Stories for news (i.e., with merely a hyperlink to a news article).

Method

We conducted a field experiment with adolescents between 12 and 18 years old to examine the effects of Instagram Stories from news accounts.

Procedure, Respondents, and Design

Respondents were recruited by a panel company (Kantar Public). Panel members between 12 and 18 years old with an Instagram account were allowed to participate. For panel members between the ages of 12 and 16, parental consent was required to participate in the study. The University approved the study under ERB protocol number 2022-PCJ-15491.

We collected data in October and November 2022. In total, 170 respondents completed the entire experimental procedure (81.0 percent). We only included respondents who indicated that they have been exposed to the Instagram stories on at least 3 days (N = 149).Footnote1 55.7 percent were female, mean age was 15.05. 14.8 percent was in the first grade, 16.8 percent was in the second grade, 14.1 percent was in the third grade, 12.8 percent was in the fourth grade, 20.8 percent was in the fifth grade, and 20.8 percent was in the sixth grade. In the Netherlands, VWO is the highest level of secondary education (duration 6 years), HAVO is the level below that (duration 5 years), and VMBO is the level below that (duration 4 years). Most respondents were in the highest level of education (VWO): 33.6 percent. 14.1 percent were in a HAVO/VWO classroom.

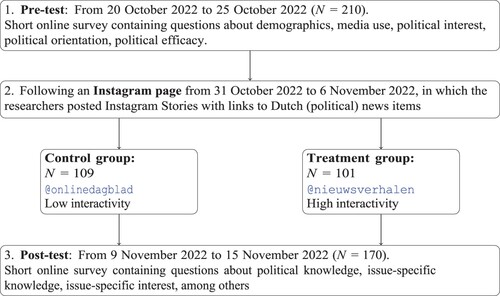

The data collection involved three distinct stages: (1) a pre-test, (2) a main stage in which respondents followed an Instagram channel (managed by the researchers) for seven days, and (3) a post-test (see for a flow diagram of the procedure). We discuss each of these stages in more detail below.

First Stage

In the first stage, respondents filled out a short online survey that contained questions about their demographics (e.g., age, gender, education), media use, news interest, political interest, political efficacy, political orientation, and Instagram use for news.

Second Stage

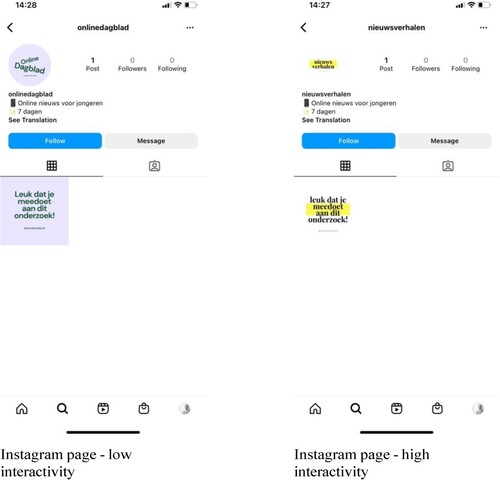

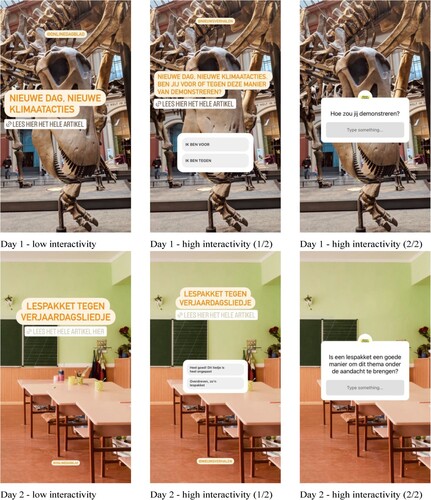

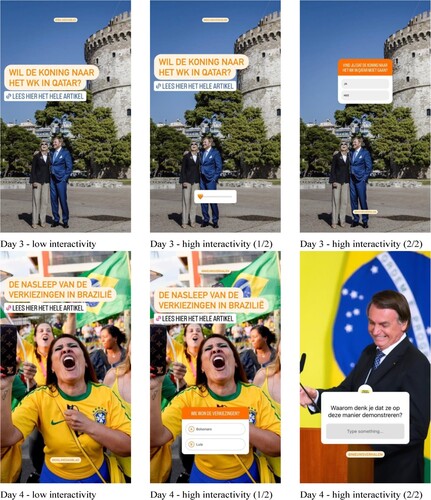

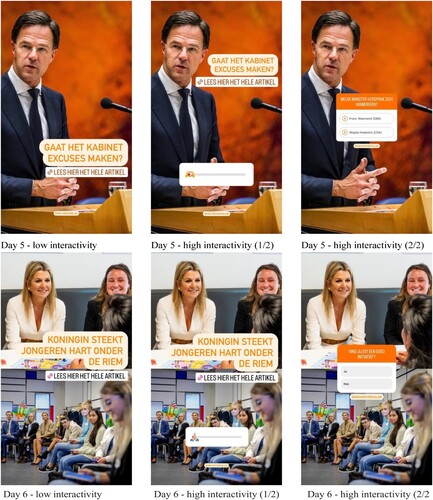

In the next stage, respondents were randomly assigned to one of the two experimental conditions. The experiment had a between-subjects design. Respondents were either exposed to (i) Instagram Stories with interactive features or (ii) Instagram Stories with less interactive features. We created two Instagram accounts with two dissimilar names to prevent that respondents would accidentally follow the wrong Instagram account: @nieuwsverhalen and @onlinedagblad (see Appendix A). Respondents were exposed to Instagram Stories for seven days. During these days, the researchers shared Instagram Stories at random time points during the day, but never during school hours or at night between 20.30 and 7.00.

Third Stage

Finally, respondents received another short online survey a few days after the end of the experiment. The survey included questions about their recall, political interest, affective responses (e.g., emotions, feelings), behavioural responses (e.g., actions and behavioural intentions related to media use, issue-specific interest), cognitive responses (e.g., issue-specific knowledge), political interest, as well as questions about trust and news avoidance.

Stimulus Material

We shared links to Dutch online news items of AD.nl (i.e., the news website of one of the largest newspapers in the Netherlands “Algemeen Dagblad”) as stimulus material, as it is a widely used news website, but not too popular among young audiences, allowing us to present them with articles they have not yet come across (Newman et al. Citation2022). By using two items, we examined whether respondents trust AD.nl as a news outlet (from strongly disagree to strongly agree, 7-point scale): “AD.nl publishes reliable and objective news” (M = 4.64, SD = 1.19), and “One can trust AD.nl” (M = 4.78, SD = 1.18). The news items covered political and current affairs news and focused on the following seven topics: Climate activism, Racism in primary education, World Cup in Qatar, Brazilian elections, Apologies for historic involvement in slavery, Mental health problems among young people, and Protests by conspiracy theorists. 39.6 percent of the respondents considered Mental health problems among young people to be the most interesting news item, 18.1 percent considered the criticism in the run-up to the World Cup in Qatar to be the most interesting topic, whereas Climate activism was the most interesting news item for 11.5 percent of the respondents. Appendix A presents all Instagram Stories that have been presented to the respondents.

Measures

Independent Variable

The independent variable of this experiment is interactivity. Interactivity is 1 if the respondent followed the Instagram account in which they received a link to a news item and were asked to give feedback (through polls, quiz stickers, and emoji sliders; N = 69), and 0 if the respondent followed the Instagram account in which merely a link to the news item has been shared (N = 80).

Dependent Variables

We used the following set of dependent variables:

Affective responses. We measured affective responses by asking respondents to indicate whether they think the Instagram Stories were interesting, boring, informative, difficult, relevant, disturbing, professional, unreliable (from “definitely not” to “definitely” on a 7-point scale). We performed a factor analysis to uncover the underlying structure of our variables. We report the total amount of variance in the variables explained by the common factor. We combined negative responses (boring, difficult, unreliable, disturbing; α = .69, M = 3.10, SD = 1.00), and positive responses (interesting, informative, relevant, professional; α = .83, M = 4.85, SD = 1.05).

Behavioural responses. We asked respondents to indicate whether the Instagram Stories they followed during their participation in the study made them more inclined to e.g., (i) “follow an Instagram page of another news organization”, (ii) “search for more information on news topics that appeared in the Instagram Stories”, (iii) “talk to friends and/or family about news topics that appeared in the Instagram Stories” (from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”, 7-point scale). A mean score was calculated (1–7) and used to examine behavioural change (α = .89, M = 3.88, SD = 1.21).

Additionally, we measured issue-specific interest for each topic in the news items shown during the second stage of the field experiment, by asking respondents to indicate whether the Instagram Stories increased their issue-specific interest (from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”, 7-point scale). A mean score was calculated (1–7) and used to examine issue-specific interest (α = .87, M = 3.65, SD = 1.15).

Cognitive responses. Finally, we will examine issue-specific knowledge by asking a set of multiple-choice questions (i.e., three answer options and an “I don’t know” option) about the news articles shared on the Instagram page. We operationalized issue-specific knowledge by counting the number of correct answers (maximum 7 points; M = 3.70, SD = 1.60). We started with one practice question: “Who is the current Prime Minister of the Netherlands?” (148 respondents answered this question correctly). We also included a timer for each question.

Additional Variables

We included a set of additional control variables—that have been shown in previous literature to have an impact on our dependent variables—in the pre-test. We included various sociodemographics, such as age, gender, and current education level. We also included political interest. This is measured by asking “How interested are you in politics?”, ranging from 1 (not at all interested) to 7 (very interested).

Analysis

We conducted different regression models to examine whether respondents in the treatment group (i.e., high interactivity; respondents received a link to a news item and were asked to give feedback through polls, quiz stickers, and emoji sliders) indicate stronger positive affective responses (i.e., interesting, informative, relevant, professional) compared to the control group (i.e., low interactivity; respondents merely received a link to a news item). We also expect that respondents in the control group indicate stronger negative responses (i.e., boring, difficult, unreliable, disturbing). Next, we examined whether respondents in the treatment group indicate stronger behavioural responses: whether their participation makes them more inclined to, for example, search issue-specific information, discuss news items with their family and friends. And, whether following an Instagram page from a news account increased their issue-specific interest. Finally, we explored whether respondents in the treatment group indicate a higher score on issue-specific political knowledge (cognitive responses).

Appendix B reports a check of the randomizations.

Results

Before we examine whether exposure to Instagram Stories for news with interactive features (i.e., polls, quiz stickers, and emoji sliders) lead to stronger (a) affective responses, (b) behavioural responses, and (c) cognitive responses compared to exposure to less interactive Instagram Stories for news, we focus our attention to some descriptive findings.

14.8 percent of the respondents uses Instagram more than ten times per day, 19.5 percent six to ten times per day, and the majority (34.9 percent) two to five times per day. On average, respondents are not often exposed to news by newspapers (M = 1.12 days per week, SD = 0.40; on a scale from 0 days per week to 7 days per week), television (M = 3.36 days per week, SD = 2.15), radio (M = 2.56 days per week, SD = 1.91), websites of newspapers (M = 2.83 days per week, SD = 2,13), or online news websites (M = 2.76 days per week, SD = 1.17). Instead, respondents often use social media to find news (M = 5.10 days per week, SD = 2.60). Young audiences increasingly rely on visually focused platforms for news. For instance, 74.5 percent uses Instagram for news, 47.0 percent uses TikTok for news, 40.3 percent uses YouTube for news, 28.9 percent uses WhatsApp for news, and 24.8 percent uses Snapchat for news. Facebook (22.2 percent) and Twitter (14.1 percent) are less popular platforms for news use among adolescents. We also examined news avoidance among adolescents (based on Newman et al. Citation2022). Around a third of the respondents indicate that news has a negative effect on their mood (31.2 percent) and that they are worn out by the amount of news (29.5 percent). 24.2 percent say that it leads to feelings of powerlessness. 18.8 percent of the respondents indicates that it is too hard to understand. A small proportion of just 6.0 percent of the respondents indicate that news is untrustworthy or biased.

The results indicate that political interest increased for all respondents throughout the experiment. We found a significant increase in political interest in the week after the experiment (M = 3.50, SD = 1.58) compared to the week before the experiment (M = 3.20, SD = 1.61), t(148) = −2.92 p = .004. We found this effect for both groups (treatment group: t(68) = −1.67, p = .01; control group: t(79) = −2.49, p = .01). This indicates that Instagram Stories covering news items could be an interesting way to foster political interest, irrespective of the level of interactivity.

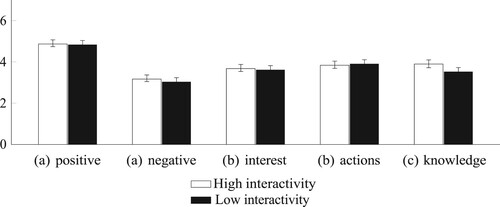

Affective Responses

First, we examined whether exposure to Instagram Stories for news with interactive features (i.e., polls, quiz stickers, and emoji sliders) leads to weaker negative responses and stronger positive responses. We conducted multi-level regression analyses in which we included several sociodemographic variables such as age, gender, and education. The results are shown as estimated marginal means (predictive margins) in and regression coefficients in . The bars in represent marginal means by condition, after controlling for age, gender, and education. In this way, the mean response has been adjusted for any other variables in our model.

Figure 2. Predictive margins and SEs of (a) affective responses, (b) behavioural responses, and (c) cognitive responses to Instagram Stories.

Table 1. Regression analyses to predict (a) affective responses, (b) behavioural responses, and (c) cognitive responses to interactive Instagram Stories.

As shown in , the results however demonstrate no effects for positive responses (e.g., interesting, relevant; b = .03, p = .87). We also did not find any significant effects for negative responses (e.g., boring, disturbing; b = .13, p = .43). In other words, our results show that respondents who have been exposed to interactive Instagram Stories do not consider these as more positive (e.g., interesting, relevant), or less negative (e.g., boring, disturbing), thereby not supporting H1a.

Behavioural Responses

Next, we examined whether exposure to interactive Instagram Stories is associated with stronger behavioural responses (see ). We used a regression model in which we also included control variables such as age, gender, and education as well as an additional control variable that might have an impact on our dependent variable (political interest). Again, the estimated marginal means are shown in . The bars represent marginal means by condition, after controlling for age, gender, and education, as well as political interest. The regression coefficients are shown in .

We found no significant effects for behavioural changes (b = −.07, p = .72), such as following an Instagram page of another news organization, sharing a news item on Instagram, visiting online news websites, or searching additional issue-specific information.

Furthermore, we found that respondents in the treatment condition did not indicate more issue-specific interest in the news topics that have been discussed in the group conversation (b = .07, p = .72). Overall, exposure to Instagram Stories for news with interactive features (i.e., polls, quiz stickers, and emoji sliders) did not lead to stronger behavioural responses compared to exposure to less interactive Instagram Stories for news (i.e., with merely a link to a news article). We found no support for H1b.

Cognitive Responses

Finally, we examined whether exposure to interactive Instagram Stories is positively associated with issue-specific knowledge. We calculated a negative binomial generalized linear model in which we also included our additional control variable (political interest) as well as sociodemographic variables (age, gender, and education) that might have an impact on our dependent variable. The estimated marginal means are shown in . The bars represent marginal means by condition, after controlling for political interest, as well as age, gender, and education.

As shown in , the results demonstrate that respondents in the treatment condition did not significantly have more knowledge about the news topics that have been shared in the Instagram Stories (b = .10, p = .24). The results do not indicate that exposure to Instagram Stories for news with interactive features (i.e., polls, quiz stickers, and emoji sliders) leads to stronger cognitive responses compared to exposure to less interactive Instagram Stories for news (i.e., with merely a link to a news article), thereby not supporting H1c.Footnote2

Discussion

News organizations are increasingly turning to social media platforms to create and disseminate news content. As a result, social media journalism has become an important part of contemporary journalism. The current study was set out to uncover the impact of the use of Instagram Stories for news. Specifically, we examined whether interactive Instagram Stories facilitate learning about politics and current events among Dutch adolescents. By using a novel field experiment, this study adds to the existing literature by empirically exploring the democratic implications of Instagram Stories for news.

Our work aims to grasp the increasingly dominant role of social media platforms, such as Instagram, in different aspects of contemporary journalism and news content production, diffusion, and consumption. One of the characteristics of social media journalism relies on the idea that news organizations can become “platform complementors” (Nieborg and Poell Citation2018)—which means that journalists have to align and integrate their daily journalistic practices with, for instance, the technological affordances of social media platforms. The findings of our study support the growing understanding that the role of social media platforms—and Instagram in particular—has become increasingly important in news consumption, especially for younger generations (Eddy Citation2022). Young audiences are shifting their attention away from Twitter and Facebook (or, in many cases, never started using these platforms). Instead, they rely on more visual-based platforms such as Instagram (74.5 percent), TikTok (47.0 percent), YouTube (40.3 percent), and Snapchat (24.8 percent).

Turning to the effects of Instagram Stories for news, the findings from our field experiment showed no significant differences in affective (emotions, feelings), behavioural (actions and issue-specific interest), and cognitive (issue-specific knowledge) responses between adolescents who were exposed to Instagram Stories with high interactivity (i.e., polls, quiz stickers, and emoji sliders) and those who were exposed to Instagram Stories with merely a hyperlink to a news article, suggesting that interactivity had no effect on these responses. On the one hand, our inability to demonstrate learning effects of interactive Instagram Stories among youth is consistent with previous research suggesting a lack of political learning through social media among adults. Specifically, studies have found that for adults, relying solely on social media to follow news about politics and current events does not result in the same level of understanding and knowledge as using traditional news media (Beckers et al. Citation2021; Shehata and Strömbäck Citation2021). On the other hand, there may be other plausible explanations for these null findings that still allow for the possibility that Instagram (Stories) contribute to adolescents’ knowledge of political and current events. These alternative explanations are discussed in detail in the following section.

A possible explanation for these null findings can be found in previous research suggesting that visual-dominant platforms such as Instagram may be more effective for information recall than text-dominant platforms such as Twitter, regardless of interactivity (e.g., Arceneaux and Dinu Citation2018). In particular, Instagram Stories may have a positive effect on information recall, irrespective of the level of interactivity, as they inherently contain more visual elements, suggesting that the level of interactivity may not be as important as suggested in this context. Another explanation can be found in the fact that there lies a journalistic challenge in ephemeral stories, as their content is exposed to users for a very short period of time, ranging from tenths of a second to up to 15 s (Vázquez-Herrero, Direito-Rebollal, and López-García Citation2019). This challenge is amplified by the constant flow of information on social media platforms, which can lead to cognitive overload and hinder learning (van Erkel and Van Aelst Citation2021). One of the constraints that can be raised is that such processes could disrupt traditional news selection and production processes. Our field experiment, which took place in adolescents’ real-world Instagram environment, may have revealed that these challenges are particularly relevant to Instagram Stories. The abundance of posts may have caused participants to overlook or skip the interactive elements of the Stories, or only interacting with them quickly. Alternatively, we can argue that in our experimental setting, even those who received non-interactive stories may have been motivated or triggered to read the news. Future research should therefore extend our research design by including a control group that receives news stories directly from an online news outlet, rather than via Instagram. This will allow for a more accurate assessment of (political) learning from interactive and visual journalistic Instagram Stories. Exploring fully visual tools on Instagram, such as Reels, may be another promising avenue for future research. News organizations are increasingly using Reels on Instagram channels that target the youth demographic, and they may offer a solution to some of the challenges we observed. Reels cater to the visual preferences of younger generations and eliminate the need to read (long) articles, which could lead to improved learning outcomes.

Another possible explanation lies in the interplay between the features of online news and the complexity of the story being presented. Research by Opgenhaffen and d’Haenens (Citation2011) suggests that there is a need to examine the effects of features such as interactivity in conjunction with the level of story complexity in future studies. This means that the degree of interactivity may have a different effect on audience engagement and news understanding depending on the complexity of the story. For example, a complex news story may require more interactive features to help the audience better understand the story, while a simple news story may require less interactivity. Because adolescents have shorter attention spans and may lack the cognitive maturity to fully comprehend complex news stories, we deliberately selected news articles that were not overly complex for our study to ensure that adolescent participants could engage with and understand the content. However, this decision may have resulted in news stories that did not require much interactivity, which could be an explanation for the results of the study.

Furthermore, our results indicate that political interest increased for all respondents throughout the experiment. A possible explanation for this finding might be that exposure to political news increased for all respondents. Previous research has shown that there is a causal relationship between news media consumption and degree of political interest (see e.g., Holt et al. Citation2013; Strömbäck and Shehata Citation2010). Another explanation for this result might be that Instagram Stories covering news items positively affect political interest, regardless of the degree of interactivity. Here too, the visual nature of Instagram Stories, which fits well with young people’s preferences, can provide an explanation. Yet, it is widely acknowledged that political interest plays a crucial role in shaping political engagement, participation, and other forms of political behaviour (Torcal and Maldonado Citation2014; Vermeer et al. Citation2021). As political interest among adolescents is still evolving, it is essential to provide them with easily accessible and captivating resources that can assist them in forming informed opinions and becoming more politically engaged. Future research should examine whether Instagram Stories can indeed serve as a powerful instrument for involving adolescents in politics and current events, ultimately leading to a more informed and politically active society.

Methodologically, this study was set out to create a feasible approach for investigating the use of Instagram for news, with a specific focus on Instagram Stories, in a setting that closely mirrors everyday Instagram use. By presenting the Instagram Stories in the adolescents’ familiar, everyday Instagram environment, we aimed to replicate real-world conditions. However, this research design also had one crucial limitation. The field experiment format made it difficult to control and account for external variables that could potentially influence the results. Future research may address other relevant factors that could play a role in citizen’s responses to Instagram Stories, such as viewing time, Stories completion (i.e., watching an Instagram Story to the end), issue involvement, pre- and post-exposure, and political socialization.

Despite this limitation, our study clearly advances existing research on this topic. Possibly the greatest advantage of this study was our ability to show the potential for Instagram Stories to serve as a tool for informing and engaging adolescents. In doing so, we have contributed to the literature in two important ways. Adolescents increasingly use Instagram to get informed about the world around them. This means that they can get exposed to news accidentally, regardless of their will to get informed about political and current events. Second, existing research on Instagram use for news relied on quantitative content analysis or interview methods (Hendrickx Citation2021; Vázquez-Herrero, Direito-Rebollal, and López-García Citation2019). By conducting an experimental study among adolescents, we have offered an empirical exploration of the democratic implications of the increasing popularity of Instagram Stories, such as political interest and political learning.

Furthermore, adolescents are a critical audience for news organizations around the world, and for the sustainability of the news, but are increasingly hard to reach and may require different strategies to engage them (Eddy Citation2022). This study shows that Instagram Stories provide a new challenge as well as a unique opportunity for news organizations to produce and disseminate political news in an appealing way. The results of our study show that Instagram Stories may positively affect political interest, regardless of the degree of interactivity. In this way, Instagram Stories may serve as a resource for engaging adolescents with politics and current events. In the current study, the goal of the Instagram Stories has been to inform and to create traffic (by addressing the audience to the website to read the news item) (as described by; Vázquez-Herrero, Direito-Rebollal, and López-García Citation2019). Yet, future work should examine to what extent different types of topics (e.g., international politics) or different formats (e.g., summaries, reports) can help news organizations to reach and engage younger audiences. As social media platforms have their own contingencies and constraints, it would be interesting to examine the implications of social media journalism on other popular platforms among young generations, such as Snapchat and TikTok. This could help to understand how news organizations can attract and retain attention to news content as well as facilitating a democratic and participatory relationship with their audiences.

All in all, this study has provided the first exploratory findings relevant to the social and political implications of Instagram Stories for news. By conducting a field experiment using Instagram, these findings not only update and advance earlier research about social media journalism, but also provide a further understanding of the role of Instagram Stories in our current media ecosystem.

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by the Digital Communication Methods Lab of the University of Amsterdam.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 We ran the same analyses with data including all respondents, as well as excluding respondents who indicated that they have been exposed to the Instagram stories on at least 4 days (N = 133), 5 days (N = 103), 6 days (N = 72), and 7 days (N = 49). The analyses yielded identical findings for all hypotheses.

2 We also examined whether high issue-specific interest positively affects issue-specific knowledge. This did not indicate any significant effects.

References

- Allan, S., and C. Peters. 2015. “Visual Truths of Citizen Reportage: Four Research Problematics.” Information, Communication & Society 18 (11): 1348–1361. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1061576.

- Al Nashmi, E. 2018. “From Selfies to Media Events: How Instagram Users Interrupted their Routines after the Charlie Hebdo Shootings.” Digital Journalism 6 (1): 98–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2017.1306787.

- Andén-Papadopoulos, K., and M. Pantti. 2013. “Re-imagining Crisis Reporting: Professional Ideology of Journalists and Citizen Eyewitness Images.” Journalism 14 (7): 960–977. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884913479055.

- Arceneaux, P. C., and L. F. Dinu. 2018. “The Social Mediated age of Information: Twitter and Instagram as Tools for Information Dissemination in Higher Education.” New Media and Society 20 (11): 4155–4176. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818768259.

- Bainotti, L., A. Caliandro, and A. Gandini. 2021. “From Archive Cultures to Ephemeral Content, and Back: Studying Instagram Stories with Digital Methods.” New Media & Society 23 (12): 3656–3676. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820960071.

- Beckers, K., P. Van Aelst, P. Verhoest, and L. d’Haenens. 2021. “What do People Learn from Following the News? A Diary Study on the Influence of Media Use on Knowledge of Current News Stories.” European Journal of Communication 36 (3): 254–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323120978724.

- Boczkowski, P. J., E. Mitchelstein, and M. Matassi. 2018. “News Comes across When I’m in a Moment of Leisure”: Understanding the Practices of Incidental News Consumption on Social Media.” New Media & Society 20 (10): 3523–3539. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817750396.

- Bucy, E. P., and C.-C. Tao. 2007. “The Mediated Moderation Model of Interactivity.” Media Psychology 9 (3): 647–672. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213260701283269.

- Coursaris, C. K., and J. Sung. 2012. “Antecedents and Consequents of a Mobile Website’s Interactivity.” New Media & Society 14 (7): 1128–1146. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444812439552.

- Deuze, M. 1999. “Journalism and the Web: An Analysis of Skills and Standards in an Online Environment.” International Communication Gazette 61 (5): 373–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016549299061005002.

- Deuze, M. 2003. “The Web and its Journalisms: Considering the Consequences of Different Types of Newsmedia Online.” New Media & Society 5 (2): 203–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444803005002004.

- Eddy, K. 2022. The Changing News Habits and Attitudes of Younger Audiences (Tech. Rep.). Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Eveland, W. P. 2004. “The Effect of Political Discussion in Producing Informed Citizens: The Roles of Information, Motivation, and Elaboration.” Political Communication 21 (2): 177–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600490443877.

- Fletcher, R., and R. K. Nielsen. 2018a. “Are People Incidentally Exposed to News on Social Media? A Comparative Analysis.” New Media & Society 20 (7): 2450–2468. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817724170.

- Fletcher, R., and R. K. Nielsen. 2018b. “Are People Incidentally Exposed to News on Social Media? A Comparative Analysis.” New Media & Society 20 (7): 2450–2468. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817724170.

- Galan, L., J. Osserman, T. Parker, and M. Taylor. 2019. “How Young People Consume News and the Implications for Mainstream Media (Tech. Rep.).” Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Geers, S. 2020. “News Consumption Across Media Platforms and Content: A Typology of Young News Users.” Public Opinion Quarterly 84 (S1): 332–354. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfaa010.

- Gil de Zúñiga, H., N. Jung, and S. Valenzuela. 2012. “Social Media use for News and Individuals’ Social Capital, Civic Engagement and Political Participation.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 17 (3): 319–336. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2012.01574.x.

- Hase, V., K. Boczek, and M. Scharkow. 2022. “Adapting to Affordances and Audiences? A Cross-platform, Multi-modal Analysis of the Platformization of News on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, and Twitter.” Digital Journalism, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2022.2128389.

- Hassan, M. M., and M. H. Elmasry. 2019. “Convergence Between Platforms in the Newsroom: An Applied Study of Al-Jazeera Mubasher.” Journalism Practice 13 (4): 476–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2018.1507681.

- Hendrickx, J. 2021. “The Rise of Social Journalism: An Explorative Case Study of a Youth-oriented Instagram News Account.” Journalism Practice 17:1810–1825. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2021.2012500.

- Hermida, A., and C. Mellado. 2020. “Dimensions of Social Media Logics: Mapping Forms of Journalistic Norms and Practices on Twitter and Instagram.” Digital Journalism 8 (7): 864–884. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2020.1805779.

- Holt, K., A. Shehata, J. Strömbäck, and E. Ljungberg. 2013. “Age and the Effects of News Media Attention and Social Media Use on Political Interest and Participation: Do Social Media Function as Leveller?” European Journal of Communication 28 (1): 19–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323112465369.

- Humayun, M. F., and P. Ferrucci. 2022. “Understanding Social Media in Journalism Practice: A Typology.” Digital Journalism 10 (9): 1502–1525. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2022.2086594.

- Ju, A., S. H. Jeong, and H. I. Chyi. 2014. “Will Social Media Save Newspapers? Examining the Effectiveness of Facebook and Twitter as News Platforms.” Journalism Practice 8 (1): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2013.794022.

- Kristensen, N. N., and M. Mortensen. 2013. “Amateur Sources Breaking the News, Metasources Authorizing the News of Gaddafi’s Death: New Patterns of Journalistic Information Gathering and Dissemination in the Digital Age.” Digital Journalism 1 (3): 352–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2013.790610.

- Ksiazek, T. B. 2018. “Commenting on the News: Explaining the Degree and Quality of User Comments on News Websites.” Journalism Studies 19 (5): 650–673. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2016.1209977.

- Ksiazek, T. B., L. Peer, and K. Lessard. 2016. “User Engagement with Online News: Conceptualizing Interactivity and Exploring the Relationship between Online News Videos and User Comments.” New Media & Society 18 (3): 502–520. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814545073.

- Kümpel, A. S. 2022. “Social Media Information Environments and their Implications for the Uses and Effects of News: The Pings Framework.” Communication Theory 32 (2): 223–242. https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qtab012.

- Kwak, N., A. E. Williams, X. Wang, and H. Lee. 2004. “Talking Politics and Engaging Politics.” Communication Research 32 (1): 87–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650204271400.

- Larsson, A. O. 2018. “‘I Shared the News Today, oh Boy’ News Provision and Interaction on Facebook.” Journalism Studies 19 (1): 43–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2016.1154797.

- Lecheler, S., and S. Kruikemeier. 2016. “Re-evaluating Journalistic Routines in a Digital age: A Review of Research on the use of Online Sources.” New Media & Society 18 (1): 156–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815600412.

- McGregor, S. C. 2019. “Social Media as Public Opinion: How Journalists use Social Media to Represent Public Opinion.” Journalism 20 (8): 1070–1086. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884919845458.

- Nee, R. C. 2019. “Youthquakes in a Post-truth Era: Exploring Social Media News Use and Information Verification Actions among Global Teens and Young Adults.” Journalism & Mass Communication Educator 74 (2): 171–184. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077695818825215.

- Neuberger, C., C. Nuernbergk, and S. Langenohl. 2019. “Journalism as Multichannel Communication: A Newsroom Survey on the Multiple Uses of Social Media.” Journalism Studies 20 (9): 1260–1280. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2018.1507685.

- Neundorf, A., K. Smets, and G. M. García-Albacete. 2013. “Homemade Citizens: The Development of Political Interest during Adolescence and Young Adulthood.” Acta Politica 48 (1): 92–116. https://doi.org/10.1057/ap.2012.23.

- Newman, N. 2022. Journalism, Media, and Technology Trends and Predictions 2022 (Tech. Rep.). https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/journalism-media-and-technology-trends-and-predictions-2022.

- Newman, N., R. Fletcher, C. T. Robertson, K. Eddy, and R. K. Nielsen. 2022. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2022 (Tech. Rep.). https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2022.

- Nieborg, D. B., and T. Poell. 2018. “The Platformization of Cultural Production: Theorizing the Contingent Cultural Commodity.” New Media & Society 20 (11): 4275–4292. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818769694.

- Opgenhaffen, M., and L. d’Haenens. 2011. “The Impact of Online News Features on Learning from News. A Knowledge Experiment.” International Journal of Internet Science 6 (1): 8–28.

- Perreault, G. P., and F. Hanusch. 2023. “Normalizing Instagram.” Digital Journalism, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2022.2152069.

- Reimer, J., M. Häring, W. Loosen, W. Maalej, and L. Merten. 2021. “Content Analyses of User Comments in Journalism: A Systematic Literature Review Spanning Communication Studies and Computer Science.” Digital Journalism, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1882868.

- Romero Saletti, S. M., S. Van den Broucke, and W. Van Beggelaer. 2022. “Understanding Motives, Usage Patterns and Effects of Instagram Use in Youths: A Qualitative Study.” Emerging Adulthood 10 (6): 1376–1394. https://doi.org/10.1177/21676968221114251.

- Scheufele, D. A. 2002. “Examining Differential Gains from Mass Media and their Implications for Participatory Behavior.” Communication Research 29 (1): 46–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365020202900103.

- Shehata, A., and J. Strömbäck. 2021. “Learning Political News from Social Media: Network Media Logic and Current Affairs News Learning in a High-choice Media Environment.” Communication Research 48 (1): 125–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650217749354.

- Strömbäck, J., and A. Shehata. 2010. “Media Malaise or a Virtuous Circle? Exploring the Causal Relationships between News Media Exposure, Political News Attention and Political Interest.” European Journal of Political Research 49 (5): 575–597. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2009.01913.x.

- Sun, J.-n., and Y.-c. Hsu. 2013. “Effect of Interactivity on Learner Perceptions in Web-based Instruction.” Computers in Human Behavior 29 (1): 171–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.08.002.

- Tamboer, S. L., M. Kleemans, and S. Daalmans. 2022. “We are a Neeeew Generation’: Early Adolescents’ Views on News and News Literacy.” Journalism 23 (4): 806–822. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884920924527.

- Tedesco, J. C. 2007. “Examining Internet Interactivity Effects on Young Adult Political Information Efficacy.” American Behavioral Scientist 50 (9): 1183–1194. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764207300041.

- Throuvala, M. A., M. D. Griffiths, M. Rennoldson, and D. J. Kuss. 2019. “Motivational Processes and Dysfunctional Mechanisms of Social Media Use among Adolescents: A Qualitative Focus Group Study.” Computers in Human Behavior 93:164–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.12.012.

- Thurman, N., and N. Newman. 2014. “The Future of Breaking News Online? A Study of Live Blogs Through Surveys of their Consumption, and of Readers’ Attitudes and Participation.” Journalism Studies 15 (5): 655–667. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2014.882080.

- Torcal, M., and G. Maldonado. 2014. “Revisiting the Dark Side of Political Deliberation: The Effects of Media and Political Discussion on Political Interest.” Public Opinion Quarterly 78 (3): 679–706. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfu035.

- Towner, T. L., and C. L. Muñoz. 2022. “A Long Story Short: An Analysis of Instagram Stories During the 2020 Campaigns.” Journal of Political Marketing 21 (3–4): 221–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377857.2022.2099579.

- Trilling, D. 2015. “Two Different Debates? Investigating the Relationship between a Political Debate on TV and Simultaneous Comments on Twitter.” Social Science Computer Review 33 (3): 259–276. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439314537886.

- van der Wal, A., P. M. Valkenburg, and I. I. van Driel. 2022. “In their Own Words: How Adolescents Differ in their Social Media Use and How it Affects Them.” https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/mvrpn

- van Erkel, P. F., and P. Van Aelst. 2021. “Why don’t We Learn from Social Media? Studying Effects of and Mechanisms Behind Social Media News Use on General Surveillance Political Knowledge.” Political Communication 38 (4): 407–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2020.1784328.

- Vázquez-Herrero, J., S. Direito-Rebollal, and X. López-García. 2019. “Ephemeral Journalism: News Distribution through Instagram Stories.” Social Media and Society 5 (4): 205630511988865. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119888657.

- Vermeer, S. A. M., S. Kruikemeier, D. Trilling, and C. H. de Vreese. 2021. “WhatsApp with Politics?!: Examining the Effects of Interpersonal Political Discussion in Instant Messaging Apps.” International Journal of Press/Politics 26 (2): 410–437. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220925020.

- Vermeer, S. A. M., D. Trilling, S. Kruikemeier, and C. H. de Vreese. 2020. “Online News User Journeys: The Role of Social Media, News Websites, and Topics.” Digital Journalism 8 (9): 1114–1141. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2020.1767509.

- Verweij, P., and E. Van Noort. 2014. “Journalists’ Twitter Networks, Public Debates and Relationships in South Africa.” Digital Journalism 2 (1): 98–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2013.850573.

- Vis, F. 2013. “Twitter as a Reporting Tool for Breaking News: Journalists Tweeting the 2011 UK Riots.” Digital Journalism 1 (1): 27–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2012.741316.

- Warnick, B., M. Xenos, D. Endres, and J. Gastil. 2005. “Effects of Campaign-to-User and Text-based Interactivity in Political Candidate Campaign Web Sites.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 10 (3). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2005.tb00253.x.

- Weaver, D. H., and L. Willnat. 2016. “Changes in us Journalism: How do Journalists Think about Social Media?” Journalism Practice 10 (7): 844–855. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2016.1171162.

- Yamamoto, M., and S. Nah. 2018. “Mobile Information Seeking and Political Participation: A Differential Gains Approach with Offline and Online Discussion Attributes.” New Media & Society 20 (5): 2070–2090. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817712722.

- Yang, F., and F. Shen. 2018. “Effects of Web Interactivity: A Meta-analysis.” Communication Research 45 (5): 635–658. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650217700748.

- Ziegele, M., T. Breiner, and O. Quiring. 2014. “What Creates Interactivity in Online News Discussions? an Exploratory Analysis of Discussion Factors in User Comments on News Items.” Journal of Communication 64 (6): 1111–1138. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12123.

Appendices

Appendix A Stimulus Material

Appendix B Results Instagram Stories

Day 1: 88.0 percent of the users in the treatment group thought that attacking art (by climate activists) is a bad way of protesting. Some respondents argue there are better ways to protest: “Start an online demonstration via a social media platform or website”, “Anything except vandalism or other acts of violence”, “By protesting with large groups in order to get media attention”.

Day 2: 67.0 percent of the users argues that it is too much of an exaggeration that highlighting the racist stereotypes of Chinese in a birthday song should form part of children’s education: “Such a subject is easily brought to children’s attention through schools”, while other argue “Just don’t sing it anymore”.

Day 3: 54.0 percent of the users argues that the King, Willem-Alexander should not attend the Qatar World Cup.

Day 4: 83.8 percent of the users knew that Lula won the Brazilian elections (instead of Bolsonaro). They thought people started blocking roads and highways in the country “To disrupt” and “Negative attention is also attention”.

Day 5: 71.1 percent of the users knew that Franc Weerwind (instead of Wopke Hoekstra) made a slip about plans of the prime minister to apologize, on behalf of the Dutch State, for the Dutch involvement in enslaving people during the colonial era.

Day 6: 100 percent of the users supports the initiative of Queen Máxima writing a letter to adolescents struggling with mental health issues.

Day 7: 82.1 percent knew that David Icke was the conspiracy theorist who was banned from Netherlands (instead of Willem Engel, Alex Jones or Steve Bannon).

Appendix C Randomization Check

To verify randomization, we regressed the control and experimental condition on a set of additional control variables (political interest), and we conducted chi-square tests for the demographics (gender, age, and education). In all cases, the null hypothesis cannot be rejected, indicating successful randomization (all p > .22). To account for chance differences in demographics or additional control variables we have examined the effects of our control variables (see Results section).

Figure A2. Instagram Stories.