ABSTRACT

Previous research has shown that right-wing hyperpartisan media have been quite successful online and on social media—especially in comparison with their mainstream media counterparts. However, the bulk of this research has not taken the theme of the media products themselves into account, looking into the types of themes dealt with by different types of media actors—and how such themes appear to influence audience engagement. With this in mind, the study presented here provides insights into news use during the COVID-19 pandemic. Focusing on Facebook and differentiating between news related to and not related to the pandemic, we ask: Does the success of Scandinavian hyperpartisan media outlets prevail also in times of societal crisis? Results indicate that for pandemic-related news, what are referred to as established media outlets perform better than hyperpartisan actors in terms of having their posts shared. As such the study differentiates our knowledge of hyperpartisan popularity online, providing further insights into how this popularity is fashioned in the three Scandinavian countries.

Introduction

As news are increasingly consumed online—especially, it would seem, on social media like Facebook—insights into citizen use of differentiated news providers become crucial for scholars and practitioners alike. Indeed, initial scholarship into online news provision and consumption was largely optimistic, foreseeing large-scale collaborations between “the people formerly known as the audience” (Rosen Citation2006) and media professionals (Gillmor Citation2004; Larsson Citation2012; Lewis, Holton, and Coddington Citation2014), citizen journalism efforts (e.g., Örnebring Citation2013) and the “mutualization” (Rusbridger Citation2009) of the journalistic trade. Hopes were undeniably high that consumers would emerge online as “prosumers” (Toffler Citation1980), “produsers” (Bruns Citation2010) or indeed “e-actors” (Fortunati and Sarrica Citation2010) in the journalistic context.

While interesting examples of such collaborations are indeed available, more recent academic as well as professional debates appear as more focused on the problems deriving from increased audience participation rather than the opportunities arising from such endeavours. For instance, research has pointed to the rise of online hate speech and the online prowess and popularity of content posted by non-traditional—some might say problematic—news providers (Quandt Citation2018; Larsson Citation2019b; Reimer et al. Citation2021). Indeed, research has shown that “fake news” (Tandoc, Lim, and Ling Citation2018), supposedly provided by alternative or hyperpartisan (Bastos and Mercea Citation2019; Kalsnes and Larsson Citation2021) outlets yield higher amounts of engagement on Facebook, thereby reaching viral status (Berger and Milkman Citation2012; Nahon and Hemsley Citation2013). As audience members engage with Facebook posts provided by news outlets—sharing, liking and commenting on their offerings—such “news use” (Picone Citation2016) expediates the spread and visibility of information. Thus, “the democratic significance of everyday news use” (Moe and Ytre-Arne Citation2022, 52) becomes quite clear—posts engaged with to comparably higher degrees will enjoy further spread on platforms such as Facebook, possibly expanding their influence.

These developments arguably come to the fore in times of societal crisis—such as during the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, as citizens intensify their monitoring of “constantly updated news streams” (Ytre-Arne and Moe Citation2021, 1739), online engagement becomes especially interesting as it can help “amplify” (Zhang et al. Citation2018) the offerings of certain news actors, spreading them further across networks of users as discussed above. While previous work has indicated the social media success of hyperpartisan actors in comparison to what can be referred to as their mainstream competitors (Kalsnes and Larsson Citation2021; Larsson Citation2019a), such scholarly efforts have not studied news use during times of crisis—such as during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study presented here provides insights into news engagement patterns in relation to different news providers in the three Scandinavian countries—Denmark, Norway and Sweden. In order to further our insights into the apparent success of hyperpartisan actors, the study differentiates between news related to the pandemic and news not related to the pandemic as offered by four different types of news providers across the three mentioned countries—public service broadcasters, broadsheets, tabloids and hyperpartisans. Juxtaposting the strong role of the three former types of media outlets in Scandinavia (Newman et al. Citation2021) with the social media success of hyperpartisan news providers as mentioned above, the study proposes the following research question: how does online news use during crisis differ between different types of news outlets? The literature review provided in the next chapter complements this overarching research question with a series of hypotheses based on expectations raised by previous scholarly efforts.

Beyond the need to differentiate our insights into the online success of hyperpartisan news providers during times of societal crisis, the study at hand contributes to our knowledge on news use in three ways. First, it compares news engagement across different types of media outlets (as suggested by e.g., Malik and Pfeffer Citation2016). Second, it is focused on non-US contexts (as suggested by e.g., Newman et al. Citation2021)—contexts where Facebook is consistently the most commonly used social media platform for news consumption and indeed use (Newman et al. Citation2020, Citation2021). Third, it features a comparative cross-country approach—as more generally suggested in relation to journalism studies (Esser and Hanitzsch Citation2012) as well as more specifically in relation to the topic at hand (Ihlebæk and Nygaard Citation2021).

Literature Review

News Users

Instead of viewing news consumers as active collaborators in the news-making process, more current conceptualizations from practitioners (Krumsvik Citation2018) and scholars (Picone Citation2016) alike tend to focus on the activities undertaken by consumers in relation to the finished news product (Hille and Bakker Citation2013; Karlsson et al. Citation2015). Indeed, the influx and seemingly ever-increasing importance of social media such as Facebook during nearly all stages of news production and consumption processes appears to have led to a strengthening of traditional roles. Rather than being allowed to participate in news production, audiences are increasingly encouraged to participate by means of liking, commenting and sharing news items on social media platforms. Chadwick, Vaccari, and O’Loughlin (Citation2018) point out that in this way, “professionally produced news not only reaches its audiences directly but also indirectly, when social media users share articles” (Citation2018, 4, emphasis in orginal; see also Bene Citation2018). As such, while their direct influence on news selection and creation may be limited, when Facebook audiences like, share and comment news they nevertheless contribute by “actively shaping media flows” (Jenkins, Ford, and Green Citation2013, 2). Previous research has indeed proposed that the influence of such “quantified audiences” (Anderson Citation2011) on editorial prioritizations is less profound than one might first assume (Zamith Citation2018). However, contrasting tendencies are also visible, as the bulk of scholarship has suggested clear influences of online audience preferences and metrics such as likes, comments and shares over editorial decisions (e.g., Tandoc Citation2014; Vu Citation2014; Welbers et al. Citation2016). With these developments in mind, the study presented here moves away from more active conceptualizations of news consumers and instead adopts the perspective of news users. As such, we consider “audience members as more than merely receivers of content” (Picone Citation2017, 382), and indeed more than “armchair audiences” (Bjur et al. Citation2014)—but we also take into account that the ways in which audiences can actually take part in the news cycle is primarily by means of “sharing the news and commenting on it” (Kalogeropoulos et al. Citation2017, 1).

News Focus and Use During Crisis

Major societal events, such as political elections, uprisings and crisis will generally lead to heightened and possibly altered levels of news attention and consumption (e.g., de León et al. Citation2021; Ørmen Citation2019). Given the global nature of the COVID-19 virus, news regarding the pandemic dominated the media agendas in a series of countries. Indeed, Ytre-Arne and Moe (Citation2021) suggest that news stories about the continued spread of the virus nearly eclipsed “political turmoil or raging wildfires in the headlines of the international news agenda” (Citation2021, 1739). In France, for instance, president Macron famously declared that the country was now “at war with the virus” (Macron Citation2020). UK audiences saw PM Johnson spearhead press briefings characterized by “short, memorable slogans and distinctive ‘emergency’ graphics” (Garland and Lilleker Citation2021, 166). Such tendencies in the European and indeed global media environment were of course mirrored in Scandinavia. In one of our case countries, Norway, March 2020 saw the ruling conservative government imposing “the strongest and most invasive measures in Norway during peacetime” (Regjeringen Citation2020: translation by the author). As pointed out by Kalsnes and Skogerbø (Citation2021, 232), this phrase—or varieties of it—was subsequently repeated during several public appearances of governmental officials, clearly showing the agenda-setting efforts of then-PM Solberg and her colleagues. In Sweden—idiosyncratically labelled as a “lone hero or stubborn outlier” (Johansson and Vigsø Citation2021, 155) in reference to the very different prioritizations made when compared to their Scandinavian neighbors—statements made by government officials in the initial phase of the pandemic appears to have differed from the Norwegian case. In their analysis of political communication in Sweden during the pandemic, Johansson and Vigsø (Citation2021) discuss an initial speech held by then-PM Löfven, describing it as “sombre and serious” albeit containing “few specific points”, leading the authors to chiefly characterize it as “a call for collective efforts” (2021, 156) rather than containing harsh measures. Regardless of the difference in tone and content when compared to the Norwegian example, daily televised press conferences were key aspects of the communication efforts undertaken by the Swedish government and the health authorities (Johansson and Vigsø Citation2021). Furthermore, while Norway and Denmark made use of lockdowns to slow the spread of the COVID-19 virus, Sweden did not—a fact that led to increased international media focus and, as an effect, increased domestic discussion about disease prevention and whether the Swedish strategy was indeed the correct one or not (Nord Citation2022). Denmark, then, emerged as similar to Norway with regards to initial actions undertaken—indeed, entering into a lockdown the day before Norway (Kalsnes and Skogerbø Citation2021) serves as illustrative of “Denmark’s rapid and centralised crisis management” especially when compared to “Sweden’s reliance on soft policy measures” (Sandberg Citation2023, 31).

Understandably, the overwhelming media coverage surrounding the pandemic led to increased media attention among publishers and broadcasters—as well as increased media consumption among the citizenry in each country (e.g., Dahlgren Citation2021, Ytre-Arne and Moe Citation2021). While differences regarding news use between countries have indeed been found (e.g., Lycarião et al. Citation2021), we nevertheless draw on the reasoning provided above and make the initial assumption that regardless of country and type of media outlet, Facebook news use will be more plentiful in relation to news related to the pandemic when compared to news not related to the pandemic. Our first hypothesis is thus formulated as follows:

H1: Facebook posts related to the pandemic will enjoy higher levels of news use than Facebook posts not related to the pandemic, regardless of media type or country.

Different Types of News Providers

Detailing news provision during times of crisis, the study at hand differentiates between tabloids, broadsheets, public service broadcasters (PSB) and hyperpartisan media outlets. While the three former classifications are well-established in journalism scholarship (e.g., Djerf-Pierre, Ghersetti, and Hedman Citation2016; Hedman and Djerf-Pierre Citation2013; Karlsson and Clerwall Citation2013; Karlsson et al. Citation2015), the latter category refers to a relatively new media phenomenon. While “alternative media” is sometimes used almost synonymously with the hyperpartisan variety, the former of these terms also carries connotations of progressive, left-wing editorial efforts (Atton Citation2001; Harcup Citation2011) or indeed of “concepts of active citizenship and empowerment” (Mayerhöffer Citation2021, 122). Following previous scholarship (Bastos and Mercea Citation2019; Fletcher et al. Citation2018; Kalsnes and Larsson Citation2021; Larsson Citation2019a, Citation2019b), hyperpartisan actors are understood here as media outlets who portray themselves as supposedly truthful, straightforward alternatives to established media. Holt, Figenschou and Frischlich (Citation2019) suggest that these types of media outlets often perceive themselves as a “self-perceived corrective” (Citation2019, 862) to the assumed ailments of contemporary media environments. Along those same lines, Strömbäck (Citation2023, 3) points to tendencies of “anti-systemness” within the respective rationales of these types of media outlets. Often describing themselves as in clear ideological conflict with mainstream media outlets or with specific political persuasions, hyperpartisan media outlets thus clearly diverge from some of the core principles often associated with the practice of journalism (e.g., Tuchman Citation1978). Common themes and talking points for Scandinavian hyperpartisan outlets tend to revolve around notions of steadily decreasing levels of safety in Denmark, Norway and Sweden, often linking immigration to increased crime rates (Ihlebæk and Nygaard Citation2021).

As alluded to above, previous research has shown themes and frames relating to crime and immigration have resulted in the social media success of hyperpartisan actors when compared to their mainstream competitors. Indeed, empirical work from Norway (Kalsnes and Larsson Citation2021; Larsson Citation2019a) and Sweden (Larsson Citation2019b) has shown followers of hyperpartisan Facebook Pages to be more active in liking, commenting and sharing than Facebook followers of other news media. While the popularity of hyperpartisan actors elsewhere online appears to have dwindled slightly (Newman et al. Citation2021), they nevertheless appear to have established themselves as media actors to be reckoned with in Scandinavia and beyond. Although previous scholarship has provided useful insights into the online popularity and spread of hyperpartisan content through “democratically dysfunctional news sharing” (Chadwick, Vaccari, and O’Loughlin Citation2018), our insights into what specific type of themes appears to drive such popularity remains somewhat limited. Indeed, while their focus on “a narrow set of issues” (Strömbäck Citation2023, 4) such as immigration appears to be somewhat of a constant fixture, we nevertheless expect that these as well as other media outlets shifted gears during the COVID-19 pandemic to devote increased attention to reporting on related events and issues. Differentiating between news use undertaken in relation to pandemic-related and non-pandemic-related content as posted by a series of different media outlets across the three Scandinavian countries, the study at hand provides useful insights into the supposedly varying prowess of different types of media actors online. Specifically, on the one hand, hyperpartisan actors have proven highly popular on social media like Facebook as discussed above. On the other hand, we expect such online allegiances to shift during times of crisis such as during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, we expect the strong role of established media outlets such as public service broadcasters in the three Scandinavian countries to yield influence over news use patterns in this regard.

While levels of media trust are likely to vary across a broader selection of countries than those studied here (Kalogeropoulos et al. Citation2019), the three Scandinavian countries have often been pointed to as examples of the “media welfare state” (Syvertsen et al. Citation2014)—media systems (Hallin and Mancini Citation2004) that traditionally have featured high levels of trust in actors such as public service broadcasters (see also Neff and Pickard Citation2021). With our current research question in mind, we expect such high levels of trust to be reflected as higher degrees of news use in times of pandemic-induced crisis. For instance, the Norwegian respondents interviewed by Ytre-Arne and Moe (Citation2021) regarding their news consumption patterns during the pandemic appeared to mainly have consumed or indeed used news from the Norwegian public service broadcaster (NRK) and from leading tabloids. Similarly, Kalsnes and Skogerbø (Citation2021) suggested that the pandemic found the Norwegian PSB enjoying growth in viewership as well as in trust among the public. Indeed, in a survey conducted on behalf of the Norwegian Media Authority in March 2020, 83% of the respondents said they had fairly high or very high trust in the news provided by the NRK. By contrast, a mere 4% of the surveyed reported that they trusted one of the most well-known hyperpartisan news outlets—Document.no—to similar degrees (Andersen Citation2020; The Norwegian Media Authority Citation2020). In Sweden, a series of nationally representative surveys undertaken by the SOM institute at the University of Gothenburg (Andersson Citation2021) found that trust in SVT, the PSB broadcaster increased in 2020 (81% of the surveyed expressing high or very high trust) before decreasing in 2021 to levels of trust reminiscent of pre-pandemic conditions (73% expressing high or very high trust). Similar findings were reported by Kaun, Jakobsson, and Stiernstedt (Citation2020), who provided survey findings corroborating the previously mentioned high trust in SVT in the Swedish population. Moreover, the same survey indicated low trust and use of hyperpartisan media outlets, further strengthening the role of public service broadcasters during times of crisis. Finally for Denmark, the Reuters Institute Digital News Report for 2020 showed that while media trust had fallen substantially—down 11%—from the year before, trust in specific media brands remained at high levels (Newman et al. Citation2020). Specifically, while 78% of the Danish population reported to trust the main public service broadcaster DR, that same statistic for one of the main tabloid newspapers—Ekstra Bladet—was gauged at 32%. These results could perhaps be seen in light of the “preference for neutral news” (Newman et al. Citation2020, 15) measured at higher levels in Denmark than for the other Scandinavian countries under scrutiny here.

Based on the above discussion, we expect Facebook posts not related to the pandemic posted by hyperpartisan actors to yield higher levels of news use than the same types of posts provided by other types of news outlets. Conversely, as Scandinavian citizens appear to trust PSB outlets more than hyperpartisan varieties, we expect Facebook posts related to the pandemic provided by PSB actors to yield higher levels of news use than the same types of posts provided by other types of news outlets. Thus, our final two hypotheses are formulated accordingly:

H2: For Facebook posts not related to the pandemic, hyperpartisan media across all studied countries will be more successful than other types of media outlets with regards to higher levels of news use.

H3: For Facebook posts related to the pandemic, PSB media across all studied countries will be more successful than other types of media outlets with regards to higher levels of news use.

Method

Data Collection

The tabloid, broadsheet, PSB and hyperpartisan outlets to be included in the study were selected based on their weekly on- and offline reach as reported by the Reuters Institute.

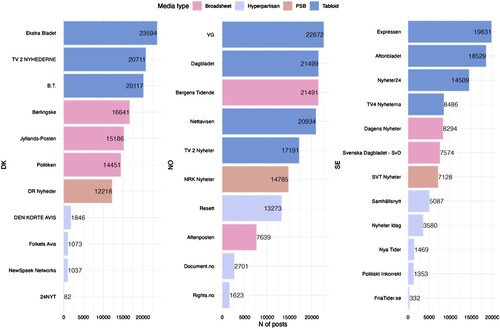

Digital News Report (Newman et al. Citation2021). The selection was further complemented with media outlets—primarily of the hyperpartisan variety—that had been identified by previous research (Ihlebæk and Nygaard Citation2021; Kalsnes and Larsson Citation2021; Larsson Citation2019b; Mayerhöffer Citation2021). Given the proverbial “ebb and flow” of hyperpartisan actors, achieving a comprehensive overview of such media outlets at any given time is difficult (as suggested by Ihlebæk and Nygaard Citation2021, 267). With this important caveat in mind, the media outlets included in the study at hand are presented in .

Data collection for the Facebook Pages of the included media outlets was undertaken by means of CrowdTangle, archiving all posts made by the Pages between 2020-01-01 and 2021-10-31. As this time period included the rising awareness of the pandemic as well as the coming and going of the societal restrictions that derived from it, the time span was deemed suitable for our purposes. CrowdTangle, then, is a service owned by Meta which allows for access to the full history of Facebook Page posts. Beyond the actual content of the posts themselves, CrowdTangle also provides different types of metadata regarding each post—such as the number of times that it had been shared at the time of data collection (for other studies that employed similar modes of data collection, please refer to, for example, Fletcher et al. Citation2018; Larsson Citation2023a, Citation2023b, Citation2019b).

Mirroring the results of previous scholarship from studied region (Kalsnes and Larsson Citation2018, Citation2021; Larsson Citation2018), indicates that tabloid news outlets are the most frequent posters on Facebook (expressed as the total number of posts), followed by broadsheets, PSB outlets and finally hyperpartisan actors. This pattern of activity remains largely the same across the three studied countries, suggesting similar editorial principles and ideas regarding the frequency of social media use.

Data Analysis

While we can think of a number of ways in which Facebook allows for news use as discussed previously, we focus here on the number of shares per post as a gauge of post popularity. The act of sharing news content on Facebook might be more socially complex than one might at first suspect. Sharing content makes it visible on the user’s own profile page, which may or may not fit with the need to curate one’s social media presence as expressed by users (Bene Citation2017; Costera Meijer and Groot Kormelink Citation2015). Once sharing is performed, though, this particular activity has been suggested as perhaps the most important metric to drive visibility on the platform at hand (Bene Citation2018; Larsson Citation2015; Socialbakers Citation2014). Indeed, Chadwick and co-authors (Citation2018) point out that Facebook posts not only reach potential news users directly through media outlet Facebook Pages—once a post is shared by a Page follower, it reaches audiences indirectly. Given the aforementioned scepticism towards the engagement type at hand, we make the assumption here that once sharing is executed, it is done in relation to content that the news user deems worthy of a wider audience—for whatever reason that might be. With these complexities in mind, focusing on shares as a representation of news use and indeed post popularity was deemed a suitable approach.

Posts were classified as pandemic-related or not pandemic-related by means of a variable constructed to query the collected data for a selection of keywords adapted to the three languages. Based on extensive test searches, any post that included localized versions of pandemic*, covid*, covid-19*, covid 19* and corona* was classified as pandemic-related, effectively indicating posts that did not contain one or more of these keywords as not pandemic-related. While it is possible that posts could be related to the pandemic without explicitly mentioning the many varieties of the searched for words that are possible, the argument is made here that the selected approach will nevertheless allow us to differentiate between posts that clearly revolve around the pandemic from those that do not. As the data did not meet normality assumptions, nonparametric analyses were undertaken by means of a series of Mann–Whitney U and Kruskal–Wallis tests (a suitable method for country comparison suggested by, for example, Esser and Vliegenthart Citation2012), the details of which are described in the subsequent results section.

Results

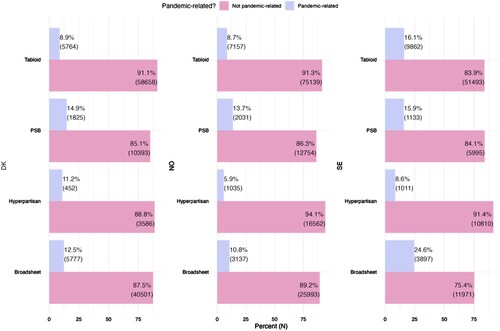

As the different types of media outlets are represented by different numbers of outlets for each country, we should perhaps focus primarily on the percentages reported in . That being said, the raw numbers indicate a dominance of tabloids in terms of the total number of posts made—and largely in terms of posts related to the pandemic (with the exception of Denmark). Looking at the relative share of pandemic-related posts, PSB actors were the most ardent in Denmark (with 14.9% of their posts dealing with the pandemic) and Norway (with 13.7% of their posts). For Sweden, broadsheet actors (24.6% of posts were related to the pandemic) came in just ahead of their tabloid (16.1% of posts) PSB competitors (with 15.9% of posts). For hyperpartisan actors, their focus during our studied time period appears to have primarily been aimed towards other issues than the pandemic. Specifically, while they provided the smallest relative amount of such posts in Norway (5.9%) and in Sweden (8.6%), they came second to last in the Danish case (11.2%).

As such, Tabloid actors seemingly adhere to what could perhaps be referred to as a flooding strategy for their Facebook presence (see Larsson Citation2016b, for similar results). By contrast, more traditional actors, such as PSBs and broadsheets, typically devote larger shares of their Facebook activity to news about the pandemic. Hyperpartisans, then emerge here as more interested in chiefly devoting their Facebook Pages to other topics.

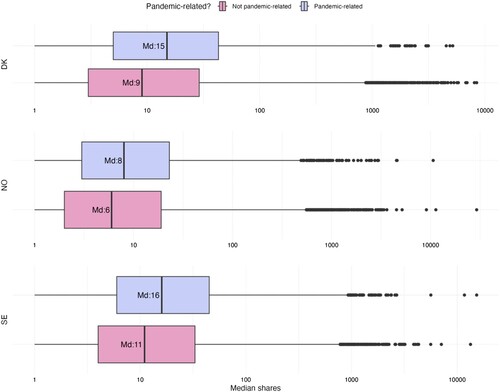

Next, we move on to assess the popularity of posts related to and not related to the pandemic as provided by the different media types. Starting with country-by-country differences, details the median amount of shares per posts related or not related to the pandemic regardless of what type of media provided the posts. Given that our data does not meet the assumption of normal distribution, we employ non-parametric tests—Mann–Whitney U tests to determine significance levels and Wilcoxon effect size tests (r) to gauge effect sizes.

Figure 3. Median shares of news related to and not related to the pandemic. Logarithmic scales presented.

In order to gauge the popularity—defined here as the median of shares—of news outlet Facebook posts related to or not related to the pandemic across our three case countries, a series of Mann–Whitney U tests were performed comparing these two categories Denmark, Norway and Sweden respectively. As can be seen in , the reported median differences follow a similar pattern for all three countries. For Denmark, posts related to the pandemic provided by the included media outlets received a higher median (Md = 15) than non-pandemic-related posts (Md = 9; p < .001; r = .08). The same pattern was found for Norway—although with a slightly smaller difference between pandemic-related posts (Md = 8) than posts that did not include such references (Md = 6; p = <.001; r = .04). Finally, the Swedish case exhibits similar tendencies—pandemic-related posts emerged as more shared (Md = 16) than posts not referencing the pandemic (Md = 11). Much like for the Danish and Norwegian contexts, the Mann–Whitney U test for the Swedish case emerged as statistically significant (p < .001), albeit with a similarly small effect size (r = .09). Thus, given the overwhelming societal repercussions of the pandemic, the result that media outlet Facebook posts dealing with such matters emerged as more shared than posts that did not confirm our first hypothesis.

While the results presented in provide us with an overarching view of news sharing during the studied period, they say little about how different categories of media outlets (as previously defined) succeeded in spreading their content on the platform under scrutiny. (for posts not related to the pandemic) and (for posts related to the pandemic) provide more detail in this regard, allowing us to address our second and third hypotheses. For the statistical analyses performed in relation to these figures, we use a combination of non-parametric tests for assessing significance levels (Kruskal–Wallis rank sum tests), effect sizes (epsilon squared, ϵ2, suggested by King et al. Citation2018) and post hoc testing (Dunn’s test).

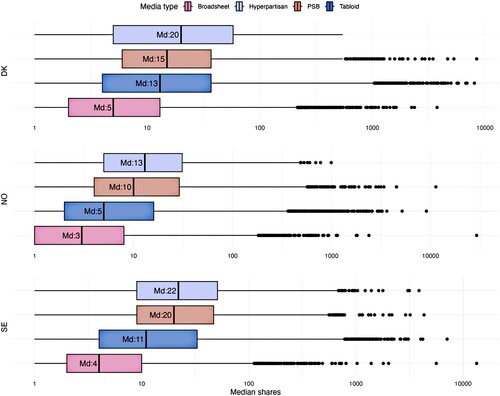

Looking first at the Danish results, visible in the upper section of , a Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test indicated significant differences among the reported medians (p < .001, ϵ2 = .08). Post-hoc testing employing Dunn’s test revealed all median differences to be statistically significant (p < .05), save for the medians reported for hyperpartisan (Md = 20) and PSB actors (Md = 15; p = .962). For Norway, a Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test indicated significant differences among the studied media outlets (p < .001, ϵ2 = .07). Post-hoc testing, again utilizing Dunn’s test, revealed all median differences to be statistically significant (p < .001 across all comparisons). Finally for posts not related to the pandemic, the Swedish results were similar to those emanating from Norway. To be precise, the Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test again indicated significant differences (p < .001, ϵ2 = .09). Performing post-hoc testing in a similar fashion as described above revealed all mean differences to be statistically significant. Specifically, p was gauged at <.001 for all comparisons save for the difference between hyperpartisan actors (Md = 22) and PSB actors (Md = 20), where significance was gauged at a different level (p < .05). In sum, for the sharing of posts not related to the pandemic, our results indicate that hyperpartisan media outlets emerge as more popular in this regard than their competitors across all three countries with an exception for the Danish case as noted above. Furthermore, regardless of country, tabloids and broadsheets find themselves in similar situations when offering content not related to the pandemic. Placing themselves at the very bottom of each section of , it is clear that the content published by these news outlets did not fare as well in terms of being shared as the content provided by their competitors. In sum, with two out of three countries falling in line with our expectations as previously discussed, we can confirm our second hypothesis.

Moving on, allows us to investigate our third and last hypothesis. With this in mind, is organized in a similar fashion as , albeit with a focus on posts related to the pandemic.

In order to gauge the statistical significance of the median differences reported for the different media types in each country in , a series of Kruskal–Wallis rank sum tests were performed—one for each country. Much like in relation to the results presented in , this approach allows for country-level insights into what actors were most successful in having their pandemic-related content shared to higher extents than their competitors.

First, for Denmark, the Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test indicated significant differences among the studied media outlets (p < .001, ϵ2 = .15). Post-hoc testing using Dunn’s test revealed all median differences to be statistically significant (p < .001). Slightly differing results emerged from the Norwegian case. Specifically, the Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test did indeed indicate significant median differences among the Norwegian media types (p < .001, ϵ2 = .06). Post-hoc testing was performed in the same fashion as described above, finding all differences to be statistically significant (p < .001) save for the comparison between hyperpartisan and tabloid actors (p > .05). Finally, the Swedish results emerged as quite similar to the results emanating from Denmark. Much like for this previous case, a Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test suggested significant differences between the media types in terms of post shares (p < .001, ϵ2 = .12). Moreover, post-hoc testing using Dunn’s test revealed all reported differences to be statistically significant (p < .001). Taken together, the results presented in suggest that across all three Scandinavian countries, the sharing of news posts related to the pandemic was dominated by PSB actors. With these results in mind, we can confirm our third hypothesis. Finally, while tabloid and hyperpartisan actors compete for the runner-up position in this regard, broadsheet actors emerge in a similar position here as presented in relation to —regardless of theme, these latter actors are not succeeding in gaining traction—in terms of having their posts shared—on Facebook.

Discussion

While previous scholarship has shown that hyperpartisan news providers are quite successful on Facebook when compared to their mainstream competitors, the results presented here show that such online prowess is challenged during wide-reaching societal crisis events—such as the COVID-19 pandemic. By studying news use during times of crisis, the results presented here make a contribution to the field of journalism studies by expanding our knowledge on the factors that drive the spread of online news—especially in relation to news that emanate from different sources. The findings presented above are elaborated on in the following.

Given the overwhelming nature of the pandemic and its repercussions for society at large, we should perhaps not be very surprised at the initial result that across all countries and all media types, posts including pandemic-related keywords as discussed previously came out on top with regards to the median number of shares per post. Be that as it may, if we look a bit closer at the results emerging from the different countries—and specifically from the different media actors within those countries—some interesting patterns start to appear.

First, for Facebook posts not related to the pandemic, suggested very similar patterns of news use across our three studied countries. For this type of news, hyperpartisan actors came out on top with regards to median shares per post, followed by PSB actors, tabloids and finally broadsheets. But while hyperpartisans appear to continue enjoying higher amounts of news use, post-hoc testing revealed some median differences for hyperpartisans and PSBs to be non-signficant (in the Danish case) or gauged at a comparably lower level of significance (in the Swedish case). While these uncovered differences must be described as small, the argument is made here that they are nevertheless testament to the important role that PSB actors have played and continue to play in the Scandinavian media systems scrutinized here.

Second, moving on to news items not related to the pandemic, the results presented in were in line with our third hypothesis which suggested that PSB media across all studied countries would be more successful than other types of media outlets with regards to higher levels of news use. PSB actors did indeed come out on top for all three countries as shown in , followed by tabloid actors in Denmark and Sweden or what could perhaps be referred to as a shared second place (given the non-significant post-hoc test as reported previously) between tabloids and hyperpartisans in Norway. On the one hand, this result could be a reflection of the tabloid format as functioning well when adapted to the short and fast nature of social media such as Facebook (Bird Citation2009; Chadwick, Vaccari, and O’Loughlin Citation2018; Larsson Citation2016a). On the other hand, the uncovered strong position of PSB actors in relation to pandemic-related content is likely related to the aforementioned steadfast role that this type of actor enjoys in the countries under scrutiny.

In conclusion, the results presented here suggest that when societal crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic strikes, Scandinavian news users appear to keep or perhaps even strengthen their trust in established news actors, resulting in increased news use in relation to PSB actors when compared to hyperpartisans. As discussed above, while previous research has shown this latter category of news providers to be particularly successful on Facebook, societal crises appear to change such patterns of news use. Seemingly related to “rally round the flag” effects suggested by Mueller (Citation1970), voters in a series of countries (Kritzinger et al. Citation2021; Lilleker et al. Citation2021; Maarek Citation2022) did indeed expressed increased support for their elected political leaders—and news usage appeared to shift more towards established actors, especially public service broadcasters as shown here (see also Ytre-Arne and Moe Citation2023). Based on these findings, future research might find it useful to detail news sharing from hyperpartisan Facebook Pages in more detail. For instance, interviews or go-along type studies of hyperpartisan news consumers or indeed users could be useful in order to gauge the degree to which the commonly used immigration narratives succeed in sparking reaction and engagement for different types of news (Chadwick, Vaccari, and O’Loughlin Citation2018; Holt Citation2016).

Finally, while this study has differentiated our insights into hyperpartisan media popularity, it nevertheless has a series of limitations that need to be duly addressed. First, the decision to focus on shares as a gauge of news use was explained previously. While sharing may be highly important, looking closer at the other ways in which news users are allowed to engage might also help deepen our insights into the popularity of news online. For instance, while commenting on Facebook is often thought of as seeking to be part of a discussion, the practice of “personal sharing” (Kalsnes and Larsson Citation2021) suggests news users simply “tagging” their friends in the comment field. This notifies the tagged friend, effectively allowing the original tagger to alert someone to the existence of a news item without having to go through the process of sharing it—which, as discussed above, can be seen as problematic and undesirable. Given the social stigma that consuming hyperpartisan news can sometimes have (Holt Citation2016), commenting in this way could serve as a way to get the messages across without promoting them openly on one’s own Facebook profile as a result of sharing. Thus, looking closer at other metrics—such as comments—could serve as a suitable step forward here. Even better, perhaps, would be if the opportunity arose to scrutinize post visibility. Specifically, if we could gauge how many users have seen or engaged with a specific post in relation to how many of those users that actually follow the Page offering said post, this would allow for more detailed scrutiny of the types of activities studied here. Indeed, “shareworthiness” (e.g., Bene Citation2021; Haim et al. Citation2021; Trilling et al. Citation2017; Wischnewski, Bruns, and Keller Citation2021) is a complex phenomenon and while our findings have pointed to the Facebook prowess of PSB as well as hyperpartisan in this regard, further insights using even more detailed data could illuminate these differences even further. However, given the current “APIcalypse” (Bruns Citation2019) and a seemingly expanding “data abyss” (de Vreese and Tromble Citation2023) such developments appear as somewhat unlikely.

Moreover, while Facebook is currently one of the most important platforms for news actors, a plethora of other such online arenas also exist. Given our focus on Facebook, perspectives from other platforms such as Twitter or Instagram are missing here. Indeed, Wischnewski, Bruns, and Keller (Citation2021) suggest the need to study hyperpartisans on different platforms, mirroring the need for comparative work expressed elsewhere (Esser and Hanitzsch Citation2012; Malik and Pfeffer Citation2016). While Twitter has been studied somewhat extensively in this regard (Engesser and Humprecht Citation2015; Hargittai Citation2020), insights into hyperpartisan use of Instagram appears as more limited. Detailing hyperpartisan employment of this latter platform could thus be a suitable way forward for interested researchers—especially since it is often pointed to as particularly important for younger media consumers (e.g., Bast Citation2021).

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Andersen, Jacob. 2020. “Nordmenn har høyest tillit til nyhetene fra NRK1 og TV 2 under koronakrisen.” In Kampanje. https://kampanje.com/medier/2020/03/nordmenn-har-hoyest-tillit-til-nyhetene-fra-nrk1-og-tv-2-under-koronakrisen/.

- Anderson, C. W. 2011. “Between Creative and Quantified Audiences: Web Metrics and Changing Patterns of Newswork in Local US Newsrooms.” Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 12 (5): 550–566. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884911402451.

- Andersson, Ulrika. 2021. “Förtroende för medier: Vinnare och förlorare under pandemin.” In SOM-undersökningen om coronaviruset 2021, 1–12. Gothenburg: Nordicom.

- Atton, Chris. 2001. Alternative Media. London: SAGE.

- Bast, Jennifer. 2021. “Managing the Image. The Visual Communication Strategy of European Right-Wing Populist Politicians on Instagram.” Journal of Political Marketing, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377857.2021.1892901.

- Bastos, Marco T., and Dan Mercea. 2019. “The Brexit Botnet and User-Generated Hyperpartisan News.” Social Science Computer Review 37 (1): 38–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439317734157.

- Bene, Marton. 2017. “Sharing Is Caring! Investigating Viral Posts on Politicians’ Facebook Pages During the 2014 General Election Campaign in Hungary.” Journal of Information Technology & Politics 14 (4): 387–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2017.1367348.

- Bene, Marton. 2018. “Post Shared, Vote Shared: Investigating the Link Between Facebook Performance and Electoral Success During the Hungarian General Election Campaign of 2014.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 95 (2): 363–380. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699018763309.

- Bene, Márton. 2021. “Topics to Talk About. The Effects of Political Topics and Issue Ownership on User Engagement with Politicians’ Facebook Posts During the 2018 Hungarian General Election.” Journal of Information Technology & Politics 18 (3): 338–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2021.1881015.

- Berger, Jonah, and Katherine L. Milkman. 2012. “What Makes Online Content Viral?” Journal of Marketing Research 49 (2): 192–205. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.10.0353.

- Bird, E. 2009. “Tabloidization: What Is It, and Does It Really Matter?” In The Changing Faces of Journalism. Tabloidization, Technology and Truthiness., edited by B. Zelizer, 40–50. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Bjur, Jakob, C. Schrøder Kim, Hasebrink Uwe, et al. 2014. “Cross-Media Use: Unfolding Complexities in Contemporary Audiencehood.” In Audience Transformations: Shifting Audience Positions in Late Modernity, edited by Nico Carpentier, Kim C Schrøder, and Lawrie Hallet, 15–29. London: Routledge.

- Bruns, Axel. 2010. “From Reader to Writer: Citizen Journalism as News Produsage.” In Internet Research Handbook, edited by Jeremy Hunsinger, Lisbeth Klastrup, and Matthew Allen, 119–134. Dordrecht, NL: Springer.

- Bruns, Axel. 2019. “After the ‘APIcalypse’: Social Media Platforms and Their Fight Against Critical Scholarly Research.” Information, Communication & Society 22 (11): 1544–1566. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118x.2019.1637447.

- Chadwick, Andrew, Cristian Vaccari, and Ben O’Loughlin. 2018. “Do Tabloids Poison the Well of Social Media? Explaining Democratically Dysfunctional News Sharing.” New Media & Society 20 (11): 4255–4274. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818769689.

- Costera Meijer, Irene, and Tim Groot Kormelink. 2015. “Checking, Sharing, Clicking and Linking.” Digital Journalism 3 (5): 664–679. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2014.937149.

- Dahlgren, P. M. 2021. Medieinnehåll och mediekonsumtion under coronapademin [Media Content and Media Consumption During the Corona Pandemic]. Department of Journalism, Media and Communication, University of Gothenburg. https://www.gu.se/sites/default/files/2021-09/Nr88-Dahlgren-Medieinnehall.pdf. Accessed 2023-04-19.

- de Vreese, Claes, and Rebekah Tromble. 2023. “The Data Abyss: How Lack of Data Access Leaves Research and Society in the Dark.” Political Communication 40 (3): 356–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2023.2207488.

- Djerf-Pierre, Monika, Marina Ghersetti, and Ulrika Hedman. 2016. “Appropriating Social Media.” Digital Journalism 4 (7): 849–860. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2016.1152557.

- Engesser, Sven, and Edda Humprecht. 2015. “Frequency or Skillfulness.” Journalism Studies 16 (4): 513–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670x.2014.939849.

- Esser, Frank, and Thomas Hanitzsch. 2012. “On the Why and How of Comparative Inquiry in Communication Studies.” In The Handbook of Comparative Communication Research, edited by Frank Esser and Thomas Hanitzsch, 3–22. London: Routledge.

- Fletcher, Richard, Alessio Cornia, Lucas Graves, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2018. “Measuring the Reach of ‘Fake News’ and Online Disinformation in Europe.” In Fact Sheets, 1–10. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Fortunati, Leopoldina, and Mauro Sarrica. 2010. “The Future of the Press: Insights From the Sociotechnical Approach.” The Information Society 26 (4): 247–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2010.489500.

- Garland, Ruth, and Darren Lilleker. 2021. “The UK—From Concensus to Confusion.” In Political Communication and Covid-19—Governance and Rhetoric in Times of Crisis, edited by Darren Lilleker, Ioana A. Coman, Miloš Gregor, and Edoardo Novelli, 165–176. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Gillmor, Dan. 2004. We the Media: Grassroots Journalism by the People, for the People. Sebastopol: O'Reilly.

- Haim, Mario, Michael Karlsson, Raul Ferrer-Conill, Aske Kammer, Dag Elgesem, and Helle Sjøvaag. 2021. “You Should Read This Study! It Investigates Scandinavian Social Media Logics.” Digital Journalism 9 (4): 406–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1886861.

- Hallin, Daniel, and Paolo Mancini. 2004. Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Harcup, Tony. 2011. “Alternative Journalism as Active Citizenship.” Journalism 12 (1): 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884910385191.

- Hargittai, Eszter. 2020. “Potential Biases in Big Data: Omitted Voices on Social Media” Social Science Computer Review 38 (1): 10–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439318788322.

- Hedman, Ulrika, and Monika Djerf-Pierre. 2013. “The Social Journalist.” Digital Journalism 1 (3): 368–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2013.776804.

- Hille, Sanne, and Piet Bakker. 2013. “I Like News. Searching for the ‘Holy Grail’ of Social Media: The Use of Facebook by Dutch News Media and Their Audiences.” European Journal of Communication 28 (6): 663–680. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323113497435.

- Holt, Kristoffer. 2016. ““Alternativmedier”? En Intervjustudie om Mediekritik och Mediemisstro [“Alternative Media?” An Interview Study About Media Criticism and Media Distrust.”].” In Migrationen i Medierna—Men Det Får en Väl lnte Prata om [The Migration in the Media], edited by Lars Truedson, 113–149. Stockholm: Institutet för mediestudier.

- Holt, Kristoffer, Tine Ustad Figenschou, and Lena Frischlich. 2019. “Key Dimensions of Alternative News Media.” Digital Journalism 7 (7): 860–869. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2019.1625715.

- Ihlebæk, Karoline Andrea, and Silje Nygaard. 2021. “Right-wing Alternative Media in the Scandinavian Political Communication Landscape.” In Power, Communication, and Politics in the Nordic Countries, edited by Eli Skogerbø, Øyvind Ihlen, Nete Nørgaard Kristensen, and Lars Nord, 263–282. Gothenburg: Nordicom.

- Jenkins, Henry, Sam Ford, and Joshua Green. 2013. Spreadable Media: Creating Value and Meaning in a Networked Culture. New York: New York University Press.

- Johansson, B., and O. Vigsø. 2021. “Sweden: Lone Hero of Stubborn Outlier?” In Political Communication and Covid-19: Governance and Rhetoric in Times of Crisis, edited by D. Lilleker, I. A. Coman, M. Gregor, and E. Novelli, 155–164. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003120254.

- Kalogeropoulos, Antonis, Samuel Negredo, Ike Picone, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2017. “Who Shares and Comments on News? A Cross-National Comparative Analysis of Online and Social Media Participation.” Social Media + Society 3 (4): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305117735754.

- Kalogeropoulos, Antonis, Jane Suiter, Linards Udris, and Mark Eisenegger. 2019. “News Media Trust and News Consumption: Factors Related to Trust in News in 35 Countries.” International Journal of Communication 13: 3672–3693.

- Kalsnes, Bente, and Anders Olof Larsson. 2018. “Understanding News Sharing Across Social Media.” Journalism Studies 19 (11): 1669–1688. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2017.1297686.

- Kalsnes, Bente, and Anders Olof Larsson. 2021. “Facebook News Use During the 2017 Norwegian Elections—Assessing the Influence of Hyperpartisan News.” Journalism Practice 15 (2): 209–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2019.1704426.

- Kalsnes, Bente, and Eli Skogerbø. 2021. “Norway—From Strict Measures to Pragmatic Flexibility.” In Political Communication and Covid-19—Governance and Rhetoric in Times of Crisis, edited by Darren Lilleker, Ioana A. Coman, Miloš Gregor, and Edoardo Novelli, 231–238. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Karlsson, Michael, Annika Bergström, Christer Clerwall, and Karin Fast. 2015. “Participatory Journalism—the (r)Evolution That Wasn’t. Content and User Behavior in Sweden 2007-2013.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 20 (3): 295–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12115.

- Karlsson, Michael, and Christer Clerwall. 2013. “Negotiating Professional News Judgment and ‘Clicks’” Nordicom Review 34 (2): 65–76. https://doi.org/10.2478/nor-2013-0054.

- Kaun, Anne, Peter Jakobsson, and Fredrik Stiernstedt. 2020. “Medier, information och tillit—preliminära resultat“. http://www.mediekom.se/?p=2196#_edn1. The Swedish Association for Media and Communication Research (FSMK). Accessed 2024-04-28.

- King, B. M., P. J. Rosopa, and E. W. Minium. 2018. “Some (Almost) Assumption-Free Tests.” In Statistical Reasoning in the Behavioral Sciences, 7th ed., edited by Bruce M. King, Patrick J. Rosopa, and Edward W. Minium. London: Wiley.

- Kritzinger, Sylvia, Martial Foucault, Romain Lachat, Julia Partheymüller, Carolina Plescia, and Sylvain Brouard. 2021. “‘Rally Round the Flag’: The COVID-19 Crisis and Trust in the National Government.” West European Politics 44 (5-6): 1205–1231. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1925017.

- Krumsvik, Arne H. 2018. “Redefining User Involvement in Digital News Media.” Journalism Practice 12 (1): 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2017.1279025.

- Larsson, Anders Olof. 2012. “Understanding Nonuse of Interactivity in Online Newspapers: Insights from Structuration Theory.” The Information Society 28 (4): 253–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2012.689272.

- Larsson, Anders Olof. 2015. “Comparing to Prepare: Suggesting Ways to Study Social Media Today–and Tomorrow.” Social Media + Society 1 (1): 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305115578680.

- Larsson, Anders Olof. 2016a. “I Shared the News Today, Oh Boy.” Journalism Studies 19 (1): 43–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670x.2016.1154797.

- Larsson, Anders Olof. 2016b. “In it for the Long Run? Swedish Newspapers and Their Audiences on Facebook 2010-2014.” Journalism Practice 11 (4): 438–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2015.1121787

- Larsson, Anders Olof. 2018. “The News User on Social Media.” Journalism Studies 19 (15): 2225–2242. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670x.2017.1332957.

- Larsson, Anders Olof. 2019a. “News Use as Amplification: Norwegian National, Regional, and Hyperpartisan Media on Facebook.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 96 (3): 721–741. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699019831439.

- Larsson, Anders Olof. 2019b. “Right-wingers on the Rise Online: Insights From the 2018 Swedish Elections.” New Media & Society 22 (12): 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819887700.

- Larsson, Anders Olof. 2023a. “The Rise of Instagram as a Tool for Political Communication: A Longitudinal Study of European Political Parties and Their Followers.” New Media & Society 25 (10): 2744–2762. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211034158.

- Larsson, Anders Olof. 2023b. “‘Win a Sweater With the PM’S Face on It’—A Longitudinal Study of Norwegian Party Facebook Engagement Strategies.” Information, Communication & Society 26 (7): 1322–1341. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118x.2021.2006743.

- León, Ernesto de, Susan Vermeer, and Damian Trilling. 2021. “Electoral News Sharing: A Study of Changes in News Coverage and Facebook Sharing Behaviour During the 2018 Mexican Elections.” Information, Communication & Society 26 (6): 1193–1209. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2021.1994629.

- Lewis, Seth C., Avery E. Holton, and Mark Coddington. 2014. “Reciprocal Journalism.” Journalism Practice 8 (2): 229–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2013.859840.

- Lilleker, Darren G., Ioana A. Coman, Miloš Gregor, and Edoardo Novelli. 2021. Political Communication and COVID-19: Governance and Rhetoric in Times of Crisis. London: Routledge.

- Lycarião, Diógenes, Marcelo Alves dos Santos, and Ana Beatriz Leite. 2021. “The News Sharing Gap.” Brazilian Journalism Research 17 (3): 706–735. https://doi.org/10.25200/BJR.v17n3.2021.1453.

- Maarek, Philippe J, Stylianos Papathanassopoulos, and Susana Salgad, eds. 2022. “Manufacturing Government Communication on Covid-19—A Comparative Perspective.” In Springer Studies in Media and Political Communication, 1–395. Cham: Springer.

- Macron, Emmanuel. 2020. Adresse aux Français du Président de la République Emmanuel Macron. https://www.elysee.fr/emmanuel-macron/2020/03/16/adresse-aux-francais-covid19, accessed 2023-04-19.

- Malik, Momin M., and Jürgen Pfeffer. 2016. “A Macroscopic Analysis of News Content in Twitter.” Digital Journalism 4 (8): 955–979. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2015.1133249.

- Mayerhöffer, Eva. 2021. “How Do Danish Right-Wing Alternative Media Position Themselves Against the Mainstream? Advancing the Study of Alternative Media Structure and Content.” Journalism Studies 22 (2): 119–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670x.2020.1814846.

- Moe, Hallvard, and Brita Ytre-Arne. 2022. “The Democratic Significance of Everyday News Use: Using Diaries to Understand Public Connection Over Time and Beyond Journalism.” Digital Journalism 10 (1): 43–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2020.1850308.

- Mueller, John E. 1970. “Presidential Popularity From Truman to Johnson.” American Political Science Review 64 (1): 18–34. https://doi.org/10.2307/1955610.

- Nahon, Karine, and Jeff Hemsley. 2013. Going Viral. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Neff, Timothy, and Victor Pickard. 2021. “Funding Democracy: Public Media and Democratic Health in 33 Countries.” The International Journal of Press/Politics. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/19401612211060255.

- Newman, Nic, Richard Fletcher, Antonis Kalogeropoulos, David A. L. Levy, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2018. “Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2018.” Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Newman, Nic, Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2020. “Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020.” Oxford, United Kingdom: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Newman, Nic, Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, Craig T. Robertson, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2021. “Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2021.” Oxford, United Kingdom: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Nord, Lars. 2022. “No Lockdown Please, We Are Swedish. How the Middle Way Country Became an Extreme Case of Government Communication.” In Manufacturing Government Communication on Covid-19, edited by Philippe J. Maarek, 107–120. Cham: Springer.

- The Norwegian Media Authority. 2020. “Tillitsmåling for utvalgte norske medier fra Medietilsynet Mars 2020”. https://www.medietilsynet.no/globalassets/dokumenter/203023_tillitsmaling_medier.pdf, accessed 2023-04-19.

- Ørmen, Jacob. 2019. “From Consumer Demand to User Engagement: Comparing the Popularity and Virality of Election Coverage on the Internet.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 24 (1): 49–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161218809160.

- Örnebring, H. 2013. “Anything You Can Do, I Can Do Better? Professional Journalists on Citizen Journalism in Six European Countries.” International Communication Gazette 75 (1): 35–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048512461761.

- Picone, Ike. 2016. “Grasping the Digital News User.” Digital Journalism 4 (1): 125–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2015.1096616.

- Picone, Ike. 2017. “Conceptualizing Media Users Across Media.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research Into New Media Technologies 23 (4): 378–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856517700380.

- Quandt, Thorsten. 2018. “Dark Participation.” Media and Communication 6 (4): 36–48. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v6i4.1519.

- Regjeringen. 2020. “Statsministerens innledning på pressekonferanse om nye tiltak mot koronasmitte.” https://www.regjeringen.no/no/aktuelt/statsministerens-innledning-pa-pressekonferanse-om-nye-tiltak-mot-koronasmitte/id2693335/. Accessed 2023-04-19.

- Reimer, Julius, Marlo Häring, Wiebke Loosen, Walid Maalej, and Lisa Merten. 2021. “Content Analyses of User Comments in Journalism: A Systematic Literature Review Spanning Communication Studies and Computer Science.” Digital Journalism, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1882868.

- Rosen, Jay. 2006. “The People Formerly Known as the Audience.” In PRESSthink—Ghost of Democracy in the Media Machine, edited by Jay Rosen. New York.

- Rusbridger, Alan. 2009. “I've Seen the Future and It’s Mutual.” British Journalism Review 20 (3): 19–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956474809348260.

- Sandberg, Siv. 2023. “The Role of Administrative Tradition in Government Responses to Crises A Comparative Overview of Five Nordic Countries.” In Communicating a Pandemic—Crisis Management and Covid-19 in the Nordic Countries, edited by Bengt Johansson, Øyvind Ihlen, Jenny Lindholm, and Mark Blach-Ørsten, 31–52. Gothenburg: Nordicom.

- Socialbakers. 2014. “Understanding & Increasing Facebook EdgeRank.” Accessed August 15th. http://www.socialbakers.com/blog/1304-understanding-increasing-facebook-edgerank.

- Strömbäck, Jesper. 2023. “Political Alternative Media as a Democratic Challenge.” Digital Journalism 11 (5): 880–887. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2023.2178947.

- Syvertsen, Trine, Gunn Enli, Ole J. Mjøs, and Hallvard Moe. 2014. The Media Welfare State: Nordic Media in the Digital Era. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

- Tandoc, Edson C. 2014. “Journalism Is Twerking? How Web Analytics Is Changing the Process of Gatekeeping.” New Media & Society 16 (4): 559–575. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814530541.

- Tandoc, Edson C., Zheng Wei Lim, and Richard Ling. 2018. “Defining ‘Fake News.” Digital Journalism 6 (2): 137–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2017.1360143.

- Toffler, Alvin. 1980. The Third Wave. New York: Bantam.

- Trilling, Damian, Petro Tolochko, and Björn Burscher. 2017. “From Newsworthiness to Shareworthiness: How to Predict News Sharing Based on Article Characteristics.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 94 (1): 38–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699016654682.

- Tuchman, Gaye. 1978. Making News: A Study in the Construction of Reality. New York: Free Press.

- Vu, Hong Tien. 2014. “The Online Audience as Gatekeeper: The Influence of Reader Metrics on News Editorial Selection.” Journalism 15 (8): 1094–1110. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884913504259.

- Welbers, Kasper, Wouter van Atteveldt, Jan Kleinnijenhuis, Nel Ruigrok, and Joep Schaper. 2016. “News Selection Criteria in the Digital Age: Professional Norms Versus Online Audience Metrics.” Journalism 17 (8): 1037–1053. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884915595474.

- Wischnewski, Magdalena, Axel Bruns, and Tobias Keller. 2021. “Shareworthiness and Motivated Reasoning in Hyper-Partisan News Sharing Behavior on Twitter.” Digital Journalism 9 (5): 549–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1903960.

- Ytre-Arne, Brita, and Hallvard Moe. 2021. “Doomscrolling, Monitoring and Avoiding: News Use in COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown.” Journalism Studies 22 (13): 1739–1755. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2021.1952475.

- Ytre-Arne, Brita, and Hallvard Moe. 2023. “Citizens’ News Use During Covid-19.” In Communicating a Pandemic: Crisis Management and Covid-19 in the Nordic Countries, edited by Bengt Johansson, Øyvind Ihlen, Jenny Lindholm, and Mark Blach-Ørsten, 303–324. Gothenburg: Nordicom, University of Gothenburg.

- Zamith, Rodrigo. 2018. “On Metrics-Driven Homepages.” Journalism Studies 19 (8): 1116–1137. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2016.1262215.

- Zhang, Yini, Chris Wells, Song Wang, and Karl Rohe. 2018. “Attention and Amplification in the Hybrid Media System: The Composition and Activity of Donald Trump’s Twitter Following During the 2016 Presidential Election.” New Media & Society 20 (9): 3161–3182. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817744390.