ABSTRACT

The debate over China’s economic influence on the European Union has grown prominent on both political and media agendas. However, little is known about how the UK media have framed EU–China trade relations in the past two decades. This case study employs a manual quantitative content analysis to investigate trends over time in the presence of frames and tone in UK newspaper coverage of EU–China trade relations (2001–2021) and to further explore differences between newspaper types in their portrayal of this topic (N = 600). Popular newspapers paid much less attention to EU–China trade relations than financial and quality newspapers but featured the most negative tone. Significant frame variation was detected over time and across newspapers, with the risk frame being the most visible. We also identified a significant negative correlation between tone and various frames. The findings not only contribute to existing economic news research by expanding on the theories of framing, negativity bias, and economic newsworthiness in the context of international trade relations but also carry implications for policy-makers and journalists.

Introduction

China has emerged as a political and economic power in the international arena, attracting growing global media attention over the past decades (Lams Citation2016; Willnat and Luo Citation2011). Since the Chinese government launched the “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI) in 2013, the debate over China’s economic influence on the European Union (EU) has gained further prominence, both in the political and media realms (Christiansen and Maher Citation2017; Zhang Citation2020).Footnote1 A plethora of research investigated media coverage of the BRI in EU countries (e.g., Andrews Citation2020; Liu Citation2023). However, the BRI is seen as an alternative to regional trade agreements (i.e., trade relations between China and individual EU member states) (European Parliament Citation2016a), which cannot represent the whole picture of EU–China trade relations at the international level. Empirical research on EU–China trade relations in the field of journalism is still scarce, especially when compared to investigations on US–China trade relations. Therefore, this paper aims to examine the media portrayal of EU–China trade relations.

Unlike US–China trade relations, there is no clash of fundamental interests or geopolitical conflicts between the EU and China (Mission of China to the European Union Citation2021). Nevertheless, EU–China trade relations are facing mounting challenges in terms of internal disputes (e.g., froze the ratification of Comprehensive Agreement on Investment due to the conflict of human rights) and external threats (e.g., Brexit, US–China trade war) (Di Carlo Citation2022; European Commission Citation2019). Grounded in framing theory (Lecheler and De Vreese Citation2019; Pan and Kosicki Citation1993; Scheufele Citation2008), its complexity also allows journalists to portray bilateral trade relations from various perspectives through modifying narrative angles in news coverage. In brief, a comprehensive analysis of how the media frame EU–China trade relations has the potential to improve the understanding of journalistic roles in the mediated debate as well as to identify emerging frames that will supplement future research on economic news.

This study aims to contribute to existing research on EU–China trade relations from four aspects. First, we examine the dynamics and changes in the media portrayal of EU–China trade relations in the past two decades (2001–2021) from a longitudinal perspective. Compared to Zhang (Citation2011) that studied how general EU–China relations were reported by People’s Daily, Financial Times, The Economist, and International Herald Tribune from 1989 to 2005, this study zooms in on “trade relations” in particular and provides latest insights into this topic. Second, we build on existing economic news research (e.g., Vliegenthart et al. Citation2021) and explore differences between newspaper types (i.e., financial vs. quality vs. popular) in their reporting on this topic. This comparative analysis not only corroborates previous findings on economic newsworthiness and newspaper types (Boukes and Vliegenthart Citation2020), but it also demonstrates the impact of media organizations on the shaping of economic news content in light of the Hierarchy-of-Influences Model (Reese and Shoemaker Citation2016). Third, we investigate the tone of framing EU–China trade relations to empirically validate the negativity bias identified in qualitative studies (Fingleton Citation2016; Nimmegeers Citation2016). To provide deeper insights into this topic, we delve further into the relationship between tone and framing. Fourth, existing research on EU–China trade relations has mainly focused on Asian or Chinese media perceptions of the EU (e.g., Chaban and Elgström Citation2014; Lai and Zhang Citation2013), despite a few observations to the contrary (e.g., Lams Citation2016; Zhang Citation2016). This study, therefore, adds to existing scholarship by particularly providing a UK perspective.

The UK has traditionally been regarded as the EU’s “awkward” partner, with a high level of Euroscepticism (George Citation1998). This Eurosceptic position has a profound influence on its media landscape, resulting in not only rather limited interest and trust in EU institutions compared to other European countries, but also a parochial pattern in news reporting, namely basing the narrative of EU-related issues on national interests and domestic concerns (Barbieri and Campus Citation2015; Pfetsch, Adam, and Eschner Citation2008). Specifically, previous research has proved that the UK is different from the rest of European countries in its way of reporting the EU—paying scarce attention to the EU but devoting extensive attention to its economic issues (e.g., Machill, Beiler, and Fischer Citation2006). This “British exceptionalism” (see Diez Medrano and Gray Citation2010) in news reporting provides a unique perspective to understand the mediated debate over EU–China trade relations.

In addition, the UK was an important player within the EU’s economic affairs before Brexit and its printed media, especially Financial Times, deemed to have an influential role in shaping public perceptions of economic issues as global (Salgado, Nienstedt, and Schneider Citation2015). Furthermore, the UK media landscape is oriented toward commercial goals (Aalberg, Van Aelst, and Curran Citation2010). As a result, news items are chosen with the goal of reflecting and capturing the concerns of as wide a lay audience as possible. Compared to newspapers in other European languages, English-language newspapers also reach relatively larger international audience.

In a nutshell, this study employs a manual quantitative content analysis (N = 600) to investigate how news coverage of EU–China trade relations varies over time and across newspaper types in the UK. We will first provide a longitudinal perspective by briefly introducing the history of EU–China trade relations and then distinguish three types of newspapers to explain macro- and meso-level factors. Next comes the theoretical analysis of main investigated elements (i.e., framing and tone) in the news coverage.

Theoretical Framework

Dynamics in EU–China Trade Relations

In 1975, the European Community (EC) and China established formal diplomatic relations (European Commission Citation1987). Following the Brussels negotiations in 1978, a non-preferential trade agreement between the European Economic Community (EEC) and China was reached and came into force (European Commission Citation1979). In 1985, this non-preferential trade agreement was replaced by the EEC-China Trade and Economic Cooperation Agreement, which aimed at promoting biliteral trade relations and encouraging the steady expansion of economic cooperation (European Union Citation1985). In 1995, the European Commission released a long-term policy for China-Europe relations, which marked a turning point in the history of bilateral trade relations (European Commission Citation1995). In 1998, the EC upgraded EU–China relations to “a comprehensive partnership” and supported China’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) (European Commission Citation1998).

In 2001, China became the 143rd member state of the WTO, which prompted its integration into the global economy and subsequently attracted global media attention (Hu and Ji Citation2012). Following that, the European debt crisis (2009–2015) led to a serious economic recession in European countries and posed new challenges to EU–China trade relations (European Parliament Citation2011). In 2013, the BRI sparked political and media debates about China’s growing economic influence in EU countries (European Parliament Citation2020). As the first G7 country, Italy’s signing up for the BRI in 2019 further escalated the ongoing debate (Vagnoni Citation2019). In the meantime, Brexit brought uncertainty to the development of EU–China trade relations (Summers Citation2017). As a result, both EU and China had to seek more balanced and reciprocal conditions governing trade and economic relations (Wang Citation2022). In 2021, the European Parliament froze the ratification process of the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) due to EU–China bilateral sanctions (European Parliament Citation2021a). More recently, EU officials and politicians have expressed increasing concerns over China’s economic expansionism and human rights violations (European Parliament Citation2021b). With all these dynamics—and ups and downs—in the EU–China trade relations, it is interesting to explore how this is reflected by over-time variations in news coverage on this topic.

Newspaper Types

As each type of newspaper caters to a distinct target audience, journalists may rely on various news factors to ensure newsworthiness when depicting EU–China trade relations (Kepplinger and Ehmig Citation2006). In line with previous research (e.g., Arrese and Vara Citation2015; Damstra and Vliegenthart Citation2018), this study explores differences between financial, quality and popular newspapers.

Financial newspapers report prominently on economic developments, with a special interest in economic and trade agreements, consumer confidence, currency exchange rates, stock market, and unemployment rates, among many others (Van Dalen et al. Citation2018). With a specific target group that is generally “educated, informed and relatively literate on issues related to the economy” (Doyle Citation2006, 436), financial journalists have to rely less on the use of news factors to make their financial news newsworthy compared to quality and popular newspapers (Boukes and Vliegenthart Citation2020), because this type of news is, by definition, newsworthy for their audience. To comply with professional norms, financial journalists are expected to ensure the analytical depth and breadth of financial reporting and to guide economic decisions of citizens (Parsons Citation1989; Van Dalen et al. Citation2021).

Quality newspapers also delve beneath the surface of stories, but approach them by highlighting political and societal relevance (Reinemann et al. Citation2012). Thus, influence and relevance are likely to guide their journalistic decisions on prominence (Boukes, Jones, and Vliegenthart Citation2022). By contrast, popular newspapers are driven by market forces relatively the most (Strömbäck, Karlsson, and Hopmann Citation2012), aiming to reach as large an audience as possible by incorporating more attractive news factors, such as personalization (Akkerman Citation2011) and negativity (O’Neill and Harcup Citation2009).

In terms of the distinction between different types of newspapers, previous research has shown higher levels of external plurality (i.e., how much newspapers differ from each other in a country) in UK media coverage of the European debt crisis (Salgado, Nienstedt, and Schneider Citation2015), which could provide an underpinning for investigating potential differences in news coverage of EU–China trade relations at the organizational level.

Framing

Journalists use framing to emphasize certain aspects of reality by modifying the wording and narrative angles in news coverage (Pan and Kosicki Citation1993; Scheufele and Tewksbury Citation2007). In this study, we employ issue-specific frames to examine the media portrayal of EU–China trade relations since the event-focused nature allows for a more in-depth understanding of this topic, especially when compared to generic frames, which are typically applied to compare different topics and contexts (Lecheler and De Vreese Citation2019; Semetko and Valkenburg Citation2000).

Previous research has inspected a plethora of frames in economic news coverage. For instance, Mao (Citation2014) studied five generic frames (i.e., economic consequences, conflict, human interest, morality, and responsibility) of the Asian financial crisis and the European debt crisis in the People’s Daily. Moreover, Yang and Van Gorp (Citation2021) identified 14 culture-embedded frames of the BRI in Australia, China, Japan, India, the UK, and the US. Damstra and Vliegenthart (Citation2018) investigated five issue-specific frames (i.e., business frame, financial frame, individual frame, Eurozone frame, and moral system frame) in Dutch newspapers during the economic crisis. Furthermore, competing and strategy frames were analyzed in news coverage of the US–China trade war (Ha et al. Citation2020; Liu, Boukes, and De Swert Citation2023). In addition, James and Boukes (Citation2017) examined how Chinese and Western media employed the opportunity frame, risk frame and morality frame to construct the economy of the East African Community. Due to the common characteristics of trade and economic events, some of them could be contextualized and adapted to analyze EU–China trade relations.

EU–China trade relations are potentially double-edged in their consequences (European Parliament Citation2016b), which corresponds well with valanced frames that carry negative and/or positive elements (De Vreese and Boomgaarden Citation2003). Specifically, Western media outlets framed China as either “a leading economic actor” or “an (unreliable) economic rival” in the international arena (Lams Citation2016, 148). In line with this ambiguous presentation, China is perceived as not only a cooperation and negotiating partner but also an economic competitor and a systematic rival for the EU (European Commission Citation2019). Hence, both opportunity and risk frames are included for the current investigation. Expanding on previous research (Schuck and De Vreese Citation2006), the former stresses positive consequences of EU–China trade relations, whereas the latter emphasizes negative consequences of EU–China trade relations. Building on the widely applied generic conflict frame, we also identify the trade conflict frame, which captures audience interest by highlighting disagreements or disputes between bilateral trade relations (Semetko and Valkenburg Citation2000).

In summary, we investigate both issue-specific frames adapted from prior research and inductively identified frames (i.e., the human rights frame and the US-intervention frame) to explore potential frame variation in news coverage of EU–China trade relations (see for frame conceptualization; see Method for details about the identification of two emerging frames). Thereby, we come up with the following questions:

RQ1a: How does the presence of frames in news coverage of EU–China trade relations vary over time?

RQ1b: How does the presence of frames in news coverage of EU–China trade relations differ across financial, quality and popular newspapers?

Table 1. Frame conceptualization in news coverage of EU-China trade relations (2001–2021).

Tone

Previous research identified systematic negativity biases in economic news coverage (Damstra and Boukes Citation2021; Soroka et al. Citation2018). With regard to news content, the negativity bias indicates that the news media are inclined to highlight negative aspects compared to positive aspects of economic issues and events (Hester and Gibson Citation2003). In terms of news effects, people also pay more attention to negative economic information than to positive economic information and, therefore, are more strongly influenced by negative cues than by positive cues (Soroka Citation2006; Citation2014). Many Western media outlets are inclined to portray the Chinese economy in a negative way, such as highlighting potential threats or disregarding accomplishments (Boden Citation2016; Nimmegeers Citation2016). For instance, Andrews (Citation2020) found growing negative media portrayals of the BRI across Europe. Under the influence of Eurosceptic tradition, the UK media also have a long history of covering EU-related issues negatively, for instance, exercising “destructive dissent” in reporting of European integration (Daddow Citation2012).

The negativity bias in news coverage might be explained by different factors (Reese and Shoemaker Citation2016). At the micro level, journalists themselves assume negativity as an important criterion for judging newsworthiness (Damstra and De Swert Citation2021). The journalist-initiated negativity is usually portrayed as negatively framed news stories or negative quotes from institutional actors (Galpin and Trenz Citation2019). At the meso level, negative reporting has the potential to benefit media organizations, especially market-driven newspapers, as the emphasis on negativity is likely to attract larger audience (McIntyre Citation2016). At the macro level, government trade policy and ideological differences could largely account for why China’s economic growth may not contribute to, and may even have the opposite effect on, the promotion of a positive international image in foreign news coverage (Hufnagel, von Nordheim, and Müller Citation2023; Peng Citation2004).

In line with previous research (Soroka et al. Citation2018), this study investigates the negativity bias by scrutinizing the tone of EU–China trade relations (i.e., negative vs. neutral vs. positive) in the news coverage. Thus, two questions are proposed:

RQ2a: How does the tone of EU–China trade relations in the news coverage vary over time?

RQ2b: How does the tone of EU–China trade relations in the news coverage differ across financial, quality and popular newspapers?

Method

A manual quantitative content analysis was conducted to investigate news coverage of EU–China trade relations in UK newspapers printed between 1 January 2001 and 31 December 2021. The starting point of the sampling period was consciously determined because China’s accession to the WTO in 2001 not only deepened China’s integration with the global trading system but also provided foreign countries with greater access to the Chinese market (Chen Citation2009). Thus, this marked the starting point of China’s growing economic influence.

Data Collection

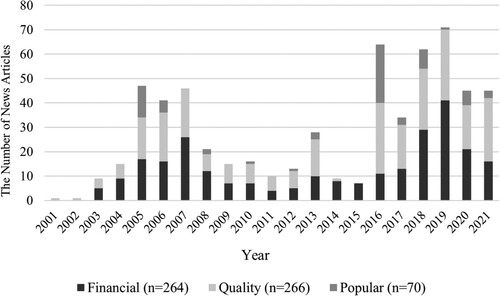

To examine the variation across different types of newspapers, we analyzed one financial newspaper, three quality newspapers, and five popular newspapers (see ). The purpose of studying a wide selection of outlets—especially for the popular outlets—is twofold: (a) to provide a comprehensive picture of the UK media landscape, and (b) to make it possible to perform statistical analyses with sufficient statistical power given its small sample size. All news articles were retrieved from the Nexis Uni Database and Dow Jones Factiva Database.Footnote2 We developed extensive search strings (see Appendix A) to ensure data comprehensiveness. After applying rigorous exclusion criteria for data collection,Footnote3 600 articles remained for the final analysis, among which only 70 articles were published by popular newspapers (11.7% of the full sample), while articles in the financial newspaper (n = 264) and quality newspapers (n = 266) took up 44.0% and 44.3% of all samples, respectively (see for over-time distribution). We included the entire sample of popular newspapers (n = 70) to compensate for the unbalanced sample size between types of newspapers.

Table 2. An overview of newspaper selection and sample size.

Measurements

Units of analysis are full-text newspaper articles. The codebook included detailed operationalizations and coding instructions (see Appendix B).

Dependent Variables

Tone of EU–China trade relations was measured by a three-point scale (Negative = −1; Neutral = 0; Positive = 1; see Soroka Citation2006).

In line with previous research (see Liu, Boukes, and De Swert Citation2023), the presence of frames was coded using dichotomous categories (No = 0; Yes = 1).

The following frames were adapted from existing research (see Schuck and De Vreese Citation2006; Semetko and Valkenburg Citation2000), namely, opportunity frame, risk frame, and trade conflict frame.Footnote4 To provide a comprehensive understanding of frames employed in the media portrayal of EU–China trade relations, we inductively diagnosed the human rights frame and the US-intervention frame via a systematic three-step approach—open coding, axial coding, and selective coding (see Appendix C for a detailed identification process). For this qualitative pilot study, a stratified random sampling technique was employed to collect articles about EU–China trade relations from each type of UK newspaper from 2001 to 2021 (N = 45).Footnote5

Independent Variables

In line with existing research (e.g., Damstra and Boukes Citation2021), time was measured by the year of publication, ranging from 2001 to 2021. Newspaper type was operationalized by three categories (i.e., financial vs. quality vs. popular). Control variables include article length (i.e., word count in numbers) and article type. The former was standardized using a z-score, and the latter was a dichotomous variable to distinguish regular news from opinion pieces.

Coding Procedure

The coding was performed by two independent coders with different cultural and academic backgrounds. During the two-week coder training in the fall of 2021, a purposive sampling strategy was adopted and in which 55 representative news articles were selected for pre-tests.Footnote6 The purpose of pre-tests was to examine the clarity of coding instructions and to identify reasons for inconsistencies. After the coder training, we employed 15% (of the final sample size) as the threshold and retrieved articles from the newswire of Reuters for the final inter-coder reliability test.Footnote7 The Krippendorff’s alpha scores of all tested variables ranged from 0.84 to 1.00 (see Appendix D), which revealed high levels of agreement between the coders.

Analysis

Descriptive statistical analyses were applied to give an account of whether and how the presence of different aspects in news coverage of EU–China trade relations varied across newspapers and over the studied time frame. Ordinal logistic regression was conducted when tone was the dependent variable. Binary logistic regressions were separately carried out between dichotomous dependent variables and independent variables. All models included article length and article type as control variables. In addition, a Spearman’s rank-order correlation analysis was performed to explore the relationship between tone and various issue-specific frames.

Results

Framing

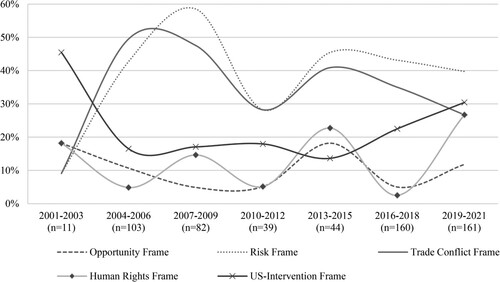

In terms of longitudinal variation (RQ1a), the presence of the risk frame and trade conflict frame were much more prominent than other frames over the studied period (see ). For each year, the human rights frame, Exp(B) = 1.07, p = .006, and the US-intervention frame, Exp(B) = 1.04, p = .035, became more likely to be present, whilst the probability to find a trade conflict frame, Exp(B) = 0.95, p = .002, decreased over time. Both opportunity and risk frames did not significantly vary across years (see Table 1 in Appendix E).

With regard to differences across newspapers (RQ1b), the risk frame was the most frequently emphasized frame in all types of newspapers (see ) and was featured more prominently (on average: 42.8%) than the much less visible opportunity frame (on average: 9.0%). Only 35 articles (5.8% of the full sample) emphasized both opportunity and risk frames, with financial (45.7%; 16 out of 35) and quality newspapers (51.4%; 18 out of 35) having nearly equal proportions, whereas popular newspapers accounted for the lowest proportion (2.9%; 1 out of 35). Compared to popular newspapers, the financial newspaper was less likely to present a risk frame, Exp(B) = 0.53, p = .022, but was more likely to present a human rights frame, Exp(B) = 4.47, p = .045. No significant differences were detected between financial and quality newspapers in terms of the presence of a risk frame, a human rights frame, and a US-intervention frame. The probability of identifying a human rights frame, Exp(B) = 5.88, p = .017, and a US-intervention frame, Exp(B) = 2.72, p = .013, in quality newspapers were also higher than in popular newspapers. There were no significant differences in the presence of an opportunity frame and a trade conflict frame in all types of newspapers.

Table 3. Presence of frames in news coverage of EU-China trade relations (2001–2021) (across newspapers).

Tone

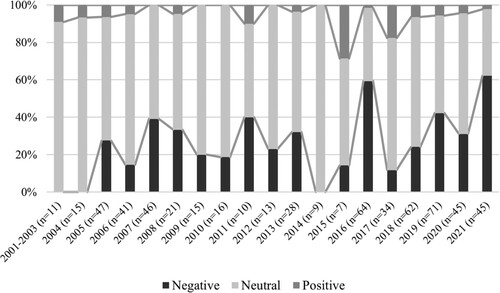

In the full dataset (N = 600), 62.3% of articles presented a neutral tone, while 32.7% of articles used a negative tone. A positive tone was rarely employed; this only made up 5.0% of all articles. In terms of over-time variation (RQ2a), the overall tone of news coverage of EU–China trade relations became more negative with every subsequent year. The negative tone emerged in 2005 and reached two peaks in 2016 and 2021 (see ), which were in line with three trade disputes: EU’s anti-dumping investigation of Chinese textiles and shoes (2005), EU’s anti-dumping duties on Chinese steel products (2016), and EU’s resolution to freeze the ratification of the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) (2021). The establishment of the BRI in 2013 might account for the “neutral” tone in 2014, which should be interpreted as a “balanced” tone, as the mediated debate mainly focused on delivering factual knowledge, portraying both pros and cons of the BRI. The relative prominence of a positive tone in 2015 reflected promising prospects for developing EU–China trade relations during Chinese President Xi’s visit to the UK. The shift in tone from 2015 to 2016 was probably caused by the EU’s hesitancy to raise tariffs on cheap Chinese imports, which resulted in job losses and bankruptcy in the UK steel industry.

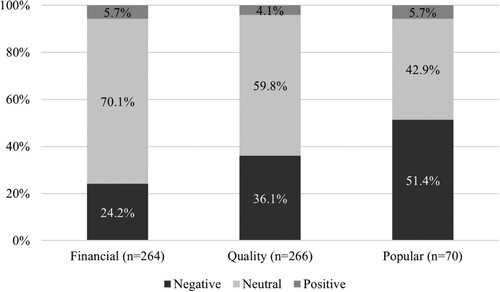

Ordinal logistic regression was applied to examine the effect of time and newspaper type on the tone (see Table 2 in Appendix E). For a one-unit increase in years, the proportional odds of positive coverage versus neutral or negative coverage decreased by 0.96 (p = .005), which suggested a negative over-time trend. With regard to differences across newspapers (RQ2b), popular newspapers framed EU–China trade relations more negatively than financial and quality newspapers, whilst the financial newspaper composed EU–China trade relations more neutrally than quality and popular newspapers (see ). Both the financial newspaper, Exp(B) = 3.30, p < .001, and quality newspapers, Exp(B) = 1.93, p = .016, held a more positive tone than popular newspapers. The tone featured by the financial newspaper was also more positive than quality newspapers, Exp(B) = 1.71, p = .004. In addition, we examined the predicted probability of tone by year and newspaper type while keeping other variables constant (see Figure 1 and Figure 2 in Appendix F).

Figure 4. The tone of EU-China trade relations in the news coverage (2001–2021) (across newspapers).

Furthermore, a Spearman’s rank-order correlation was performed to explore the relationship between tone and frames. The analyses revealed a significant but weak positive correlation between tone and opportunity frame (rs = .218, p < .001), suggesting that the more opportunity frame was employed, the more positive tone was used to frame EU–China trade relations, and vice versa. We also found a significant but weak negative correlation between tone and risk frame (rs = −.285, p < .001), trade conflict frame (rs = −.228, p < .001), human rights frame (rs = −.139, p = .001), and the US-intervention frame (rs = −.115, p = .005). The finding indicated that the negative tone played a role in the framing of EU–China trade relations.

Discussion

Our research yielded three major findings. First, we detected significant frame variation over time: the human rights frame and the US-intervention frame gained prominence, whereas the trade conflict frame became less visible. Second, the tone of EU–China trade relations showed an increase in negativity, with popular newspapers clearly being the most negative. Third, except for the opportunity frame, we identified the prominent role of negativity in the framing process of EU–China trade relations.

In terms of framing analysis, this study expands on previous research (Schuck and De Vreese Citation2006) and extends the application scope of “opportunity” and “risk” frames from EU internal affairs (i.e., EU enlargement) to EU external affairs (i.e., EU–China trade relations). The prevalence of risk over opportunity frames over time reflects long-lasting concern about the potential negative consequences of promoting EU–China trade relations and echoes the “China Threat” policy frame narrated by European think tanks (Rogelja and Tsimonis Citation2020). The salience of risk frame in popular newspapers corroborates existing findings on ambiguous economic news—popular newspapers had the lowest proportion of emphasizing both positive and negative consequences of economic news stories (Svensson et al. Citation2017). The journalistic tendency to emphasize negative aspects of EU–China trade relations is also consistent with the profit motive of popular newspapers, given their market-driven characteristics (Strömbäck, Karlsson, and Hopmann Citation2012).

The conflict is considered one of the most important criteria determining newsworthiness (Bartholomé, Lecheler, and De Vreese Citation2015). No significant differences in the presence of a trade conflict frame were detected across three types of newspapers, which contradicts the previous finding that Dutch financial newspapers emphasized less conflict than quality and popular newspapers (Boukes and Vliegenthart Citation2020). On the one hand, different contexts and time frames make the findings less comparable. On the other hand, as the UK media landscape is highly commercialized, the financial newspaper (i.e., Financial Times) also has market-based considerations to capture audience interest (Allern Citation2002). The emphasis on conflict may make news stories more prominent to attract a large audience (Lee Citation2009).

The growing prominence of human rights and US-intervention frames, accompanied by the decreasing visibility of a trade conflict frame, indicates the increasing politicization of EU–China trade relations over time. This finding is in line with observations from other disciplines, such as international relations (Eckhardt Citation2019). It is also the first time that this finding (i.e., increasingly politicized EU–China trade relations) has been empirically validated in journalism research. Specifically, existing studies mainly examined “human rights” and “US intervention” as topics rather than issue-specific frames in media coverage (e.g., Krumbein Citation2015; Mermin Citation1999). For instance, “economic/trade/finance/business” and “human rights” are operationalized as two sub-categories of news topics to study EU–China relations (i.e., Zhang Citation2011). Therefore, this study sheds lights upon how the emphasis on human rights and US intervention shape news coverage of EU–China trade relations. In particular, the considerable prominence of both human rights and US-intervention frames on quality newspapers corroborates that quality newspapers tend to frame news stories from a political perspective (Reinemann et al. Citation2012). There are two possible explanations for the great emphasis on the US perspective in all types of newspapers. First, in light of the indexing hypothesis and information subsidies (Bennett Citation1990; Berkowitz and Adams Citation1990), journalists are likely to lend credibility to news coverage by indexing institutionally powerful sources. Second, the UK’s Eurosceptical stance may play a part in accounting for the finding, because existing research has demonstrated limited trust in EU institutions among the UK press (Barbieri and Campus Citation2015). The emphasis on the US perspective in reporting EU–China trade relations could potentially enhance the credibility of UK news coverage on EU-related issues. Besides, the prominent role of the US in news coverage of EU–China trade relations reflects economic interdependence among three major powers in reality (Besch, Bond, and Schuette Citation2020).

We identified the role of negativity in the framing process of EU–China trade relations. Specifically, the employment of risk, trade conflict, human rights, and US-intervention frames more frequently can result in a more negative tone, and vice versa. This may contribute to the growing negative trend of portraying EU–China trade relations. More importantly, this increased negativity corroborates previous research on Euroscepticism in the UK press—a clear negativity bias in framing EU-related news stories (e.g., Daddow Citation2012; Galpin and Trenz Citation2019). Despite increased negativity over time, the overall tone of mediated EU–China trade relations (2001–2021) was more often neutral than negative, which partially contradicts previous findings on the predominance of negative reporting on China-related topics (Fingleton Citation2016; Nimmegeers Citation2016). On the one hand, neutral reporting may indicate that UK journalists perform a watchdog role in reporting EU–China trade relations (Bennett and Serrin Citation2005). On the other hand, neutrality reflects a long-standing debate over EU–China trade relations (i.e., weigh up the pros and cons). Popular newspapers featured the most negative tone toward EU–China trade relations, which corroborates that popular newspapers are likely to emphasize negativity compared to the financial and quality newspapers (e.g., Boukes and Vliegenthart Citation2020; Skovsgaard Citation2014). The financial newspaper, by contrast, possessed a more neutral and less evaluative tone, which conformed to their professional norms (e.g., objectivity) (Pollach and Hansen Citation2021).

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the current study concentrated on UK newspapers; a follow-up study could include a broader range of outlets from various EU countries to examine the generalizability of our findings. Second, we conceptualized the EU in a narrow scope and did not inspect bilateral trade relations between individual EU member states and China, which may lead to a rather small sample size. Further studies might explore how news media covered the impact of Brexit, specifically, on triangle trade relations among the EU, the UK, and China. Third, we examined the differences between financial, quality, and popular newspapers. Future research could also detect potential differences between outlets with different political stances (i.e., left vs. right). Fourth, despite systematic coding instructions, only two coders were involved in the coding process. More coders might be helpful to strengthen the explanatory power of the current findings.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this study (a) addresses a clear research gap and provides a comprehensive picture of the UK media portrayal of EU–China trade relations over the past two decades; (b) identifies new issue-specific frames (i.e., human rights and US-intervention frames) employed by the UK journalists to shape news content of EU–China trade relations; (c) expands on previous economic news research by validating relevant findings (see details above). In terms of societal implications, politicians and government officials might realize the increasing politicization of EU–China trade relations and, thereby, use the media to strategically promote trade policy. Journalists, on the other hand, should be aware of the increasing trend of reporting EU–China trade relations in negative terms—and consider whether this is simply a reflection of the current political situation or whether they are contributing to the growing frictions between both economic powers.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (2.1 MB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank three anonymous reviewers, Prof. Dr. Sora Park and Dr. Willem Joris for their constructive feedback on a previous version of this manuscript.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Due to Brexit, the UK is not counted as an EU country since 1 January 2021. In this study, the EU refers to EU institutions (e.g., European Council, European Commission, and European Parliament). Therefore, trade relations between individual EU member states and China are not counted as EU-China trade relations.

2 News articles in The Daily Telegraph were retrieved from the Dow Jones Factiva database; news articles in other eight newspapers were collected from the Nexis Uni database.

3 We manually screened and eliminated news briefs, letters to editors, book reviews, and long lists of reported economic figures and indicators (see Soroka, Stecula, and Wlezien Citation2015). News articles longer than 3,000 words were excluded considering coding efficiency and topic relevance (see Lasorsa and Dai Citation2007). This is also because the longer articles excluded are exclusively from the Financial Times and The Guardian, which were, in absolute terms, already overrepresented in the sample. Including these longer articles would make the sample even more unbalanced (i.e., more articles from financial/quality newspapers but fewer articles from popular newspapers). In line with comparable studies, duplicate and irrelevant news articles were also removed (see Soroka et al. Citation2018). Contrary to Temple et al. (Citation2016), we included all relevant editorials and opinion pieces, because these articles not only reflect the perspective of news organizations but also shed light upon the mediated debate about EU-China trade relations.

4 We coded the presence of eight frames at an early stage. Three frames, namely “economic moral system”, “individual”, and “business” were consciously left out of the revised version because they were all adapted from existing research conducted in the Dutch context (Damstra and Vliegenthart Citation2018) and they turned out to be not very salient in the context of our study.

5 The stratified sampling technique was employed to ensure each type of newspaper could be adequately represented in the sample: Financial Newspaper (n = 20), Quality Newspaper (n = 20), Popular Newspaper (n = 5). As the total sample size (N = 600) is small, news articles (n = 45) analyzed for identifying emerging frames in this qualitative pilot study were also included in the final analysis.

6 News articles for Pre-ICR Tests were selected from The Independent (2001–2021).

7 News articles in Reuters were retrieved from the Dow Jones Factiva database. The same search string was applied for data collection (see Appendix A). Reuters was used for two reasons. First, almost all UK newspapers were employed for the final analysis; thus, these could not be used for the checks of inter-coder reliability. Moreover, the number of relevant articles in other newspapers (e.g., The Irish Times) did not reach the benchmark (15% of the final sample size). Second, existing research (Jonkman et al. Citation2020) has provided empirical evidence that news agencies and newspapers provide comparable results for economic news.

References

- Aalberg, T., P. Van Aelst, and J. Curran. 2010. “Media Systems and the Political Information Environment: A Cross-National Comparison.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 15 (3): 255–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161210367422.

- Akkerman, T. 2011. “Friend or Foe? Right-Wing Populism and the Popular Press in Britain and the Netherlands.” Journalism 12 (8): 931–945. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884911415972.

- Allern, S. 2002. “Journalistic and Commercial News Values: News Organizations as Patrons of an Institution and Market Actors.” Nordicom Review 23 (1–2): 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1515/nor-2017-0327.

- Andrews, D. 2020. “All Roads Lead to Europe: Media Perceptions of the Belt and Road Initiative in the European Union.” Master’s thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Carolina Digital Repository. https://cdr.lib.unc.edu/concern/dissertations/c247dz52h?locale=en.

- Arrese, Á, and A. Vara. 2015. “Divergent Perspectives? Financial Newspapers and the General Interest Press.” In The Euro Crisis in the Media: Journalistic Coverage of Economic Crisis and European Institutions, edited by R. G. Picard, 149–176. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Barbieri, G., and D. Campus. 2015. “Who Will Fix the Economy? Expectations and Trust in the European Institutions.” In The Euro Crisis in the Media: Journalistic Coverage of Economic Crisis and European Institutions, edited by R. G. Picard, 63–80. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Bartholomé, G., S. Lecheler, and C. H. De Vreese. 2015. “Manufacturing Conflict? How Journalists Intervene in the Conflict Frame Building Process.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 20 (4): 438–457. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161215595514.

- Bennett, W. L. 1990. “Toward a Theory of Press-State Relations in the United States.” Journal of Communication 40 (2): 103–127. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1990.tb02265.x.

- Bennett, W. L., and W. Serrin. 2005. “The Watchdog Role.” In The Press, edited by G. Overholser, and K. Jamieson, 169–188. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Berkowitz, D., and D. B. Adams. 1990. “Information Subsidy and Agenda-Building in Local Television News.” Journalism Quarterly 67 (4): 723–731. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769909006700426.

- Besch, S., I. Bond, and L. Schuette. 2020. Europe, the US and China: A Love-Hate Triangle? Centre for European Reform. https://www.cer.eu/sites/default/files/pbrief_us_china_eu_SB_IB_LS.pdf.

- Boden, J. 2016. “Mass Media: Playground of Stereotyping.” International Communication Gazette 78 (1–2): 121–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048515618116.

- Boukes, M., N. P. Jones, and R. Vliegenthart. 2022. “Newsworthiness and Story Prominence: How the Presence of News Factors Relates to Upfront Position and Length of News Stories.” Journalism 23 (1): 98–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884919899313.

- Boukes, M., and R. Vliegenthart. 2020. “A General Pattern in the Construction of Economic Newsworthiness? Analyzing News Factors in Popular, Quality, Regional, and Financial Newspapers.” Journalism 21 (2): 279–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884917725989.

- Chaban, N., and O. Elgström. 2014. “The Role of the EU in an Emerging New World Order in the Eyes of the Chinese, Indian and Russian Press.” Journal of European Integration 36 (2): 170–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2013.841679.

- Chen, C., ed. 2009. China’s Integration with the Global Economy: WTO accession, Foreign Direct Investment, and International Trade. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Christiansen, T., and R. Maher. 2017. “The Rise of China—Challenges and Opportunities for the European Union.” Asia Europe Journal 15: 121–131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-017-0469-2.

- Daddow, O. 2012. “The UK Media and ‘Europe’: From Permissive Consensus to Destructive Dissent.” International Affairs 88 (6): 1219–1236. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2346.2012.01129.x.

- Damstra, A., and M. Boukes. 2021. “The Economy, the News, and the Public: A Longitudinal Study of the Impact of Economic News on Economic Evaluations and Expectations.” Communication Research 48 (1): 26–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650217750971.

- Damstra, A., and K. De Swert. 2021. “The Making of Economic News: Dutch Economic Journalists Contextualizing Their Work.” Journalism 22 (12): 3083–3100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884919897161.

- Damstra, A., and R. Vliegenthart. 2018. “(Un)covering the Economic Crisis? Over-time and Inter-media Differences in Salience and Framing.” Journalism Studies 19 (7): 983–1003. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2016.1246377.

- De Vreese, C. H., and H. Boomgaarden. 2003. “Valenced News Frames and Public Support for the EU.” Communications 28 (4): 361–381. https://doi.org/10.1515/comm.2003.024.

- Di Carlo, I., ed. 2022. EU-China Trade Relations at a Crossroads. European Policy Centre. https://epc.eu/content/PDF/2022/EU-China_Think-Tank_Compendium.pdf.

- Diez Medrano, J., and E. Gray. 2010. “Framing the European Union in National Public Spheres.” In The Making of a European Public Sphere: Media Discourse and Political Contention, edited by R. Koopmans, and P. Statham, 195–220. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Doyle, G. 2006. “Financial News Journalism: A Post-Enron Analysis of Approaches Towards Economic and Financial News Production in the UK.” Journalism 7 (4): 433–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884906068361.

- Eckhardt, J. 2019. “Law and Diplomacy in EU–China Trade Relations: A Historical Overview.” In Law and Diplomacy in the Management of EU–Asia Trade and Investment Relations, edited by C.-H. Wu, and F. Gaenssmantel, 58–74. London: Routledge.

- European Commission. 1979. The People’s Republic of China and the European Community. http://aei.pitt.edu/8242/1/31735055282226_1.pdf.

- European Commission. 1987. EEC-China Joint Committee. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/MEMO_87_3.

- European Commission. 1995. A Long Term Policy for China-Europe Relations. https://eeas.europa.eu/archives/docs/china/docs/com95_279_en.pdf.

- European Commission. 1998. Building a Comprehensive Partnership with China. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:1998:0181:FIN:EN:PDF.

- European Commission. 2019. EU-China: A Strategic Outlook. https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2019-03/communication-eu-china-a-strategic-outlook.pdf.

- European Parliament. 2011. EU-China Trade Relations. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/etudes/join/2011/433861/EXPO-INTA_ET(2011)433861_EN.pdf.

- European Parliament. 2016a. One Belt, One Road (OBOR): China’s Regional Integration Initiative. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2016/586608/EPRS_BRI(2016)586608_EN.pdf.

- European Parliament. 2016b. New Trade Rules for China? Opportunities and Threats for the EU. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2016/535021/EXPO_STU%282016%29535021_EN.pdf.

- European Parliament. 2020. EU-China Trade and Investment Relations in Challenging Times. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2020/603492/EXPO_STU(2020)603492_EN.pdf.

- European Parliament. 2021a. EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2021/679103/EPRS_BRI(2021)679103_EN.pdf.

- European Parliament. 2021b. People’s Republic of China: Partner or Rival? https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2021/690654/EPRS_BRI(2021)690654_EN.pdf.

- European Union. 1985. “Agreement on Trade and Economic Cooperation between the European Economic Community and the People’s Republic of China.” Official Journal of the European Communities. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:21985A0919%2801%29:EN:HTML#d1e37-2-1.

- Fingleton, W. 2016. “The Quest for Balanced Reporting on China in the EU Media: Forces and Influences.” International Communication Gazette 78 (1–2): 83–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048515618114.

- Galpin, C., and H. J. Trenz. 2019. “Converging towards Euroscepticism? Negativity in News Coverage during the 2014 European Parliament Elections in Germany and the UK.” European Politics and Society 20 (3): 260–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/23745118.2018.1501899.

- George, S. 1998. An Awkward Partner: Britain in the European Community. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ha, L., Y. Yang, R. Ray, F. Matanji, P. Chen, K. Guo, and N. Lyu. 2020. “How US and Chinese Media Cover the US-China Trade Conflict: A Case Study of War and Peace Journalism Practice and the Foreign Policy Equilibrium Hypothesis.” Negotiation and Conflict Management Research. Advance Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/ncmr.12186.

- Hester, J. B., and R. Gibson. 2003. “The Economy and Second-Level Agenda Setting: A Time-Series Analysis of Economic News and Public Opinion about the Economy.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 80 (1): 73–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769900308000106.

- Hu, Z., and D. Ji. 2012. “Ambiguities in Communicating with the World: The “Going-out” Policy of China’s Media and its Multilayered Contexts.” Chinese Journal of Communication 5 (1): 32–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750.2011.647741.

- Hufnagel, L. M., G. von Nordheim, and H. Müller. 2023. “From Partner to Rival: Changes in Media Frames of China in German Print Coverage between 2000 and 2019.” International Communication Gazette 85 (5): 412–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/17480485221118503.

- James, E. K., and M. Boukes. 2017. “Framing the Economy of the East African Community: A Decade of Disparities and Similarities Found in Chinese and Western News Media’s Reporting on the East African Community.” International Communication Gazette 79 (5): 511–532. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048516688130.

- Jonkman, J. G. F., M. Boukes, R. Vliegenthart, and P. Verhoeven. 2020. “Buffering Negative News: Individual-Level Effects of Company Visibility, Tone, and Pre-Existing Attitudes on Corporate Reputation.” Mass Communication and Society 23 (2): 272–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2019.1694155.

- Kepplinger, H. M., and S. C. Ehmig. 2006. “Predicting News Decisions. An Empirical Test of the Two-Component Theory of News Selection.” Communications 31 (1): 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1515/COMMUN.2006.003.

- Krumbein, F. 2015. “Media Coverage of Human Rights in China.” International Communication Gazette 77 (2): 151–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048514564028.

- Lai, S.-Y., and L. Zhang. 2013. “Challenging the EU’s Economic Roles? The Impact of the Eurozone Crisis on EU Images in China.” Baltic Journal of European Studies 3 (3): 13–36. https://doi.org/10.2478/bjes-2013-0019.

- Lams, L. 2016. “China: Economic Magnet or Rival? Framing of China in the Dutch- and French-Language Elite Press in Belgium and the Netherlands.” International Communication Gazette 78 (1–2): 137–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048515618117.

- Lasorsa, D., and J. Dai. 2007. “When News Reporters Deceive: The Production of Stereotypes.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 84 (2): 281–298. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769900708400206.

- Lecheler, S., and C. H. De Vreese. 2019. News Framing Effects. Oxford: Routledge.

- Lee, J. H. 2009. “News Values, Media Coverage, and Audience Attention: An Analysis of Direct and Mediated Causal Relationships.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 86 (1): 175–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769900908600111.

- Liu, L. 2023. “Network Analysis: A Cross-Country Comparison of Peer Attention among EU Countries in Response to China with the Media Data.” Journal of Contemporary European Studies 31 (3): 797–817. https://doi.org/10.1080/14782804.2022.2047618.

- Liu, S., M. Boukes, and K. De Swert. 2023. “Strategy Framing in the International Arena: A Cross-National Comparative Content Analysis on the China-US Trade Conflict Coverage.” Journalism 24 (5): 976–998. https://doi.org/10.1177/14648849211052438.

- Machill, M., M. Beiler, and C. Fischer. 2006. “Europe-topics in Europe’s Media: The Debate about the European Public Sphere: A Meta-Analysis of Media Content Analyses.” European Journal of Communication 21 (1): 57–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323106060989.

- Mao, Z. 2014. “Cosmopolitanism and Global Risk: News Framing of the Asian Financial Crisis and the European Debt Crisis.” International Journal of Communication 8: 1029–1048. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/2240/1115.

- McIntyre, K. 2016. “What Makes “Good” News Newsworthy?” Communication Research Reports 33 (3): 223–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2016.1186619.

- Mermin, J. 1999. Debating War and Peace: Media Coverage of U.S. Intervention in the Post-Vietnam Era. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Mission of China to the European Union. 2021. EPC’s Sixty-Minute Briefing with Chinese Ambassador Zhang Ming. November 19. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/wjb_663304/zwjg_665342/zwbd_665378/202111/t20211119_10450476.html.

- Nimmegeers, D. 2016. “Presentation of China in Online West European Media: More Fairness and Accuracy Required.” International Communication Gazette 78 (1–2): 104–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048515618115.

- O’Neill, D., and T. Harcup. 2009. “News Values and Selectivity.” In The Handbook of Journalism Studies, edited by K. Wahl-Jorgensen, and T. Hanitzsch, 161–174. New York: Routledge.

- Pan, Z., and G. M. Kosicki. 1993. “Framing Analysis: An Approach to News Discourse.” Political Communication 10 (1): 55–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.1993.9962963.

- Parsons, W. 1989. The Power of the Financial Press: Journalism and Economic Opinion in Britain and America. Aldershot: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Peng, Z. 2004. “Representation of China: An across Time Analysis of Coverage in the New York Times and Los Angeles Times.” Asian Journal of Communication 14 (1): 53–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/0129298042000195170.

- Pfetsch, B., S. Adam, and B. Eschner. 2008. “The Contribution of the Press to Europeanization of Public Debates: A Comparative Study of Issue Salience and Conflict Lines of European Integration.” Journalism 9 (4): 465–492. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884908091295.

- Pollach, I., and L. V. Hansen. 2021. “Tone Variation in Financial News: A Comparison of Companies, Journalists and Financial Analysts.” European Journal of Communication 36 (5): 511–526. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323121999524.

- Reese, S. D., and P. J. Shoemaker. 2016. “A Media Sociology for the Networked Public Sphere: The Hierarchy of Influences Model.” Mass Communication and Society 19 (4): 389–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2016.1174268.

- Reinemann, C., J. Stanyer, S. Scherr, and G. Legnante. 2012. “Hard and Soft News: A Review of Concepts, Operationalizations and Key Findings.” Journalism 13 (2): 221–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884911427803.

- Rogelja, I., and K. Tsimonis. 2020. “Narrating the China Threat: Securitising Chinese Economic Presence in Europe.” The Chinese Journal of International Politics 13 (1): 103–133. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjip/poz019.

- Salgado, S., H.-W. Nienstedt, and L. Schneider. 2015. “Consensus or Discussion? An Analysis of Plurality and Consonance in Coverage.” In The Euro Crisis in the Media: Journalistic Coverage of Economic Crisis and European Institutions, edited by R. G. Picard, 103–124. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Scheufele, D. A. 2008. “Framing Effects.” In The International Encyclopedia of Communication, edited by W. Donsbach, 1862–1868. Malden, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- Scheufele, D. A., and D. Tewksbury. 2007. “Framing, Agenda Setting, and Priming: The Evolution of Three Media Effects Models: Models of Media Effects.” Journal of Communication 57 (1): 9–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0021-9916.2007.00326.x.

- Schuck, A. R. T., and C. H. De Vreese. 2006. “Between Risk and Opportunity: News Framing and Its Effects on Public Support for EU Enlargement.” European Journal of Communication 21 (1): 5–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323106060987.

- Semetko, H. A., and P. M. Valkenburg. 2000. “Framing European Politics: A Content Analysis of Press and Television News.” Journal of Communication 50 (2): 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2000.tb02843.x.

- Skovsgaard, M. 2014. “A Tabloid Mind? Professional Values and Organizational Pressures as Explanations of Tabloid Journalism.” Media, Culture & Society 36 (2): 200–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443713515740.

- Soroka, S. N. 2006. “Good News and Bad News: Asymmetric Responses to Economic Information.” The Journal of Politics 68 (2): 372–385. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2508.2006.00413.x.

- Soroka, S. N. 2014. Negativity in Democratic Politics: Causes and Consequences. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Soroka, S. N., M. Daku, D. Hiaeshutter-Rice, L. Guggenheim, and J. Pasek. 2018. “Negativity and Positivity Biases in Economic News Coverage: Traditional Versus Social Media.” Communication Research 45 (7): 1078–1098. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650217725870.

- Soroka, S. N., D. A. Stecula, and C. Wlezien. 2015. “It’s (Change in) the (Future) Economy, Stupid: Economic Indicators, the Media, and Public Opinion.” American Journal of Political Science 59 (2): 457–474. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12145.

- Strömbäck, J., M. Karlsson, and D. N. Hopmann. 2012. “Determinants of News Content: Comparing Journalists’ Perceptions of the Normative and Actual Impact of Different Event Properties When Deciding What’s News.” Journalism Studies 13 (5–6): 718–728. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2012.664321.

- Summers, T. 2017. Brexit: Implications for EU–China Relations. Chatham House. https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/research/2017-05-11-brexit-eu-china-summers.pdf.

- Svensson, H. M., E. Albæk, A. Van Dalen, and C. H. De Vreese. 2017. “The Impact of Ambiguous Economic News on Uncertainty and Consumer Confidence.” European Journal of Communication 32 (2): 85–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323116677205.

- Temple, L., M. T. Grasso, B. Buraczynska, S. Karampampas, and P. English. 2016. “Neoliberal Narrative in Times of Economic Crisis: A Political Claims Analysis of the U.K. Press, 2007–14.” Politics & Policy 44 (3): 553–576. https://doi.org/10.1111/polp.12161.

- Vagnoni, G. 2019. “Italy endorses China’s Belt and Road plan in first for a G7 nation.” Reuters, March 23. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-italy-china-president-idUSKCN1R40DV.

- Van Dalen, A., M. Skovsgaard, C. H. De Vreese, and E. Albæk. 2021. “Economic Beat Journalists: Which Audience Perceptions, what Conception of Democracy?” Journalism Practice 15 (9): 1272–1288. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2021.1972028.

- Van Dalen, A., H. Svensson, A. Kalogeropoulos, E. Albæk, and C. H. De Vreese. 2018. Economic News: Informing the Inattentive Audience. New York: Routledge.

- Vliegenthart, R., A. Damstra, M. Boukes, and J. Jonkman. 2021. Economic News: Antecedents and Effects. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wang, Q. 2022. “The China–EU Relation and Media Representation of China: The Case of British Newspaper’s Coverage of China in the Post-Brexit Referendum Era.” Asia Europe Journal 20: 283–303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-021-00611-9.

- Willnat, L., and Y. Luo. 2011. “Watching the Dragon: Global Television News about China.” Chinese Journal of Communication 4 (3): 255–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750.2011.594552.

- Yang, H., and B. Van Gorp. 2021. “A Frame Analysis of Political-media Discourse on the Belt and Road Initiative: Evidence from China, Australia, India, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2021.1968794.

- Zhang, L. 2011. News Media and EU-China Relations. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Zhang, Z. 2016. “A Narrative Future for Europe–China Economic Relations after the Financial Crisis.” Global Media and China 1 (1–2): 49–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/2059436416646270.

- Zhang, L. 2020. “China’s Belt and Road Initiative in the European Media: A Mixed Narrative?” In One Belt, One Road, One Story? Towards an EU-China Strategic Narrative, edited by A. Miskimmon, B. O’Loughlin, and J. Zeng, 115–137. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.