ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 pandemic raised questions about trust in journalism and the quality of news reporting during societal crises. While journalists and media professionals frequently offered critical reflections based on personal experiences and observations, computational methods are not widely used to support these evaluative processes. We aim to extend the conversation on metajournalistic discourse by considering the inclusion of empirical methods for monitoring journalistic practices. By disclosing our findings about Dutch news media’s corona reporting between 2019 and 2022, we demonstrate how computational methods for content analyses of news texts can yield empirically informed insights into different facets of journalistic performance. The corpus includes 106,616 corona-related articles from national and regional newspapers in the Netherlands. We deployed text analytical methods such as topic modelling and named entity recognition to explore Dutch corona reporting in respect to different normative criteria (informing, monitoring, offering platforms for discussion and opinion, interpretation, analysis, and setting public agendas). The study was requested by a large Dutch newspaper to receive a systematic-empirical analysis of journalistic practice for self-evaluation. We argue that computational methods combined with qualitative analyses can stimulate dialogue and critical reflection among news media professionals.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic posed a complex challenge to journalism, negatively impacting press freedom also in liberal-democratic societies such as the Netherlands. Arguably, this was intertwined with political and social polarisation, induced by the escalating health crisis and corresponding governance measures. In the Dutch context, public trust in the press discernibly dwindled among segments of society, while animosity towards news media heightened. Amid intensifying tensions, Dutch public broadcaster Nederlandse Omroep Stichting (NOS) even decided to remove its logo from satellite vans used for on-site reporting—a direct response to threats against its journalists. Opponents of mainstream journalism circulated flyers stating, “our media are the virus,” and suggested “alternative” media for the “other side of the story.” In these attacks, journalists were accused of promoting governmental agendas and failing to provide a critical, balanced overview of diverse opinions. While political extremes often attempt to advance dubious agendas with their criticism, these tensions do raise vital questions about trust in journalism and the quality of news reporting during societal crises. Developments in the Netherlands echoed broader trends across Europe, where rifts between alternative and mainstream media discourses emerged in different countries (Frischlich et al. Citation2023). The proliferation of disinformation via digital networks complicated this volatile situation, contributing to social tensions around the pandemic. Furthermore, a perceived information overload led some Dutch citizens to avoid the news altogether (de Bruin et al. Citation2021).

Legacy news media play an integral role during health crises as “agents of information and persuasion” (De Coninck, d'Haenens, and Matthijs Citation2020). Accordingly, mainstream news media endeavoured to cover the pandemic in real-time, in detail, and from multiple perspectives. Their corona reporting elicited varied reactions across society, including justified and unjustified critiques of journalistic performance. Emerging health crises place news media in a challenging position with considerable uncertainties and journalists often rely on government sources during unfolding crisis situations. In the case of COVID-19, legacy news media largely viewed themselves as responsible for communicating the necessity of e.g., social distancing, mask wearing, and vaccinations. This opened them to accusations of being mouthpieces for the government (Perreault and Perreault Citation2021). Journalists strive to provide critical and balanced coverage of complex societal challenges but must avoid contributing to conspiracy theories and baseless rejections of health advice. It is a delicate balancing act for journalists facing considerable obstacles in crises contexts, such as remote work and limited source access (Quandt and Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2021).

Against this backdrop, the present paper addresses a challenging yet pressing question posed to the authors by a large Dutch newspaper that is part of Belgian media house De Persgroep (DPG): How “well” did Dutch newspapers cover the corona pandemic? The editor-in-chief sought quantitative insights into corona reporting to see if journalists’ experiences indicated structural issues and to assess journalistic quality. Journalistic quality measures how well reporting meets standards like accuracy, fairness, balance, diversity, and relevance, reflecting journalism's democratic mission (Jandura and Friedrich Citation2014; Urban and Schweiger Citation2014). However, questions about journalistic quality are difficult to assess, since “there are simply no universal evaluative criteria at hand, and many of those chosen often owe their relevance to the changing and passing circumstances of time or space”. Still, metajournalistic discourse, that is, how media professionals and other societal stakeholders discuss and perceive journalism, often centres on critically evaluating journalistic practices based on these quality criteria. Media professionals usually resort to anecdotal data, which is valuable yet limited. The request for the present research project signalled the newspaper's desire to enrich the professional metajournalistic discourse toolbox with empirical data.

We propose an integration of computational-quantitative and qualitative methods to critically explore journalistic performance. By disclosing our findings about Dutch news media's corona reporting between 2019 and 2022, we demonstrate how data-driven distant readings of large volumes of news texts (N = 106,616), combined with critical close readings of selected cases, yield insights into different dimensions of journalistic performance. Methodologically, we first analyse discussions among journalists and editors, and then assess if their claims hold empirically. The newspaper's request for a critical-systematic academic review of their work is by itself an important resource for metajournalistic discourse. It pushed us researchers to align our methods with practical use, while balancing academic goals. The analyses provided an empirical basis facilitating discussion about what journalism is and should be during a crisis. This connects to questions about the legitimacy of journalism by emphasising professional accountability and reflection.

Metajournalistic Discourse

Metajournalistic discourse encompasses discussions on journalistic norms and practices (e.g., Perreault, Perreault, and Maares Citation2022). Carlson defines it as the public evaluation of news content, the processes behind its creation, or the circumstances under which it is received. Journalists and non-journalists alike engage in this discourse across multiple platforms, both inside and outside news media. Digital media’s rise has broadened spaces for discussing journalistic performance. Arguably, this development has been ambiguous, moving from initial euphoria about watchdogs for watchdogs (Bruns Citation2009) to concerns about social media’s role in the distribution of disinformation, including false accusations against mainstream media for fabricating stories (Figenschou and Ihlebæk Citation2019). It is therefore vital to separate valid criticism from baseless attacks on journalism. Tools and methods for self-critical assessment of journalistic practice can help news media refute unfounded claims from their opponents.

Carlson suggests that metajournalistic discourse can be reactive, responding to specific incidents and controversies, or generative, when it stimulates wider discussions yielding recommendations for the role and specific goals of journalism in society as well desirable journalistic practices. Simply put, the former focuses on problems and issues that raise questions about journalistic performance, while the latter aims to prescribe ways forward with an eye on concrete practices. Both functions are interconnected. As he explains, “[j]ournalism’s status as an authoritative form of knowledge creation is not guaranteed or static, but the product of discourses that both delimit and legitimate its cultural forms” (Carlson Citation2015, 13). Metajournalistic discourse encompasses ideas both of what journalism is and what journalism should be (Carlson Citation2015), linking evaluative with prescriptive statements. Metajournalistic discourse may not lead to fixed rules for journalism, but it aids in identifying issues and guiding future actions towards preferred outcomes. It can foster professional self-reflection at both organisational and individual levels, potentially driving practical changes in how journalists execute their roles. Recent examples for metajournalistic discourses are critical reflections on AI in the newsroom (Moran and Shaikh Citation2022) and journalistic performance during the corona pandemic (Perreault, Perreault, and Maares Citation2022).

Professional Accountability and Reflection

Raising questions about journalistic practice and quality is part of daily business in the news domain and an important area in journalism studies (Meier Citation2023). While it is critical to acknowledge that no singular definition or form of journalism exists (Deuze and Witschge Citation2020), modernist conceptualisations influence the field. The underlying ideology, linking journalistic practice to democratic ideals and societal responsibility, shapes professional attitudes (Deuze Citation2019). Values and guidelines may vary by culture, news organisation, and journalist, but they typically prioritise journalism’s role in informing publics, holding elites accountable, and fostering balanced public debates on key issues. This is particularly true for “orienting journalism” (Deuze and Witschge Citation2020, 21) as practised by legacy news media. In the Dutch context, five normative functions of journalism as identified by sector organisation NDP Nieuwsmedia express these aspirations in concrete terms: (1) informing, (2) monitoring, (3) offering platforms for discussion and opinion, (4) offering interpretation and analysis, and (5) setting public agendas (NDP, n.d.).

These guidelines resonate with normative theories about journalism in academia, such as public sphere theory (Garman Citation2023), normative news media theories (Christians et al. Citation2010), and studies on journalistic norms (Hanitzsch and Vos Citation2018). They reflect journalists’ normative self-perception in political discussions, which seems consistent across cultures (Standaert, Hanitzsch, and Dedonder Citation2021). The five functions represent norms that are crucial for practitioners and their metajournalistic discourse, emphasising journalism's role in democracy (McNair Citation2009) without academics dictating top-down what “good journalism” is. Instead, these functions are defined and refined by the professional field itself. Ideally, journalistic practice should prioritise accuracy, balance, diversity, and societal relevance as key quality metrics. While not all journalism must serve a democratic or political normative function—a view that can be seen as one-dimensional (Hanitzsch and Vos Citation2018)—normative issues and political questions become important in crisis reporting. The Dutch news sector’s normative functions thus offer a useful framework for how news media professionals view and evaluate their work.

Normative goals set by journalists link to “obligations and expectations” that society holds towards journalism and shape its societal responsibility (McQuail Citation2003). Paraphrasing Hodges, Bardoel and d‘ Haenens (Citation2004, 7) argue, “responsibility has to do with defining proper conduct; accountability with compelling it.” Journalism must meet normative standards and quality criteria to uphold credibility and achieve its societal-democratic objectives (McQuail Citation2003). This includes ensuring transparency in journalistic practices and accountability, particularly amid waning public trust (Brants Citation2013; Henke, Leissner, and Möhring Citation2020). Accountability focuses on questions of whether news media live up to their own and society's expectations. Brants (Citation2013) defines professional accountability as voluntary actions by media practitioners to act according to their journalistic principles and the self-regulatory structures that support them. Various channels and instruments address accountability through sectoral reflection, such as ombudsmen, ethical codes, press councils, trade journals, and editorial weblogs (Bertrand Citation2018). These contribute to reflective metajournalistic discourse among professionals, academics, and regulators about journalistic performance and -quality, which can serve as a corrective measure to shortcomings and blind spots in journalistic practice (Perreault, Perreault, and Maares Citation2022).

Regarding media ethics, discussing professional accountability links to critical reflection. Crucially, reflection is not merely a tool for accountable reporting; instead, accountability relates to journalists’ reflective virtue and internal motivations (Bertrand Citation2018). Reflection supports accountable reporting but does not ensure it. Ramaker, van der Stoep, and Deuze (Citation2015) note that enforcing reflection from the outside clashes with journalists’ autonomy and is met with scepticism, as it can disrupt their workflow and sit at odds with their instincts. It should rather be seen as a means “to learn and improve the quality of one’s work” (ibid., 350). Routine plays an important role in understanding the prevalence of tacit, implicit knowledge. It is precisely this routine that becomes the object of critical inquiry. Building on Schön (Citation1983), Ramaker et al. distinguish between reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action. The former pertains to in-the-moment reflection, while the latter refers to post-event learning and improvement. They posit that critical reflection is different from evaluation as it “can help to recognize routine behaviour and open up the way for innovation” (Ramaker, van der Stoep, and Deuze Citation2015, 36).

Utilising Computational Methods for Supporting Critical Reflection

To enhance insights from news professionals’ qualitative self-reflections, which often happen ad-hoc, computational methods can provide additional quantitative data about various facets of journalistic practice. Many newsrooms already use data analysis to monitor their reach and audience engagement (Kristensen Citation2023) or deploy AI-tools for content creation and comment moderation (Diakopoulos Citation2019). Research on data-driven newsrooms often addresses either how metrics affect journalistic output (Christin Citation2020), the development of recommender systems (Bastian, Helberger, and Makhortykh Citation2021), or data journalism (Bounegru and Gray Citation2021). Prevailing uses of computational methods and data-driven work practices prioritise business considerations and content formats rather than questions of self-reflection and accountability. One study that illustrates alternative uses of computational methods investigated the potential for public service media (PSM) to understand their role in public discourses (Veerbeek, van Es, and Müller Citation2022). The researchers analysed a large volume of newspaper articles with topic modelling to identify thematic contexts in which PSM were mentioned. This enabled PSM to reflect on their role in society and take action to meet their normative organisational objectives.

The main argument of the present study is that journalistic organisations can productively use similar methods to critically reflect on their practices. Methods for automated content analysis such as topic modelling can help with tracking diversity and imbalances in the coverage of different societal domains affected by a crisis. Named entity recognition (NER) can uncover who is mentioned, cited, and what this says about voice representation. These examples illustrate how computational methods can be adapted for journalistic self-evaluation, critical reflection, accountability, and eventually enhancing trust with audiences. It is crucial to combine computational trend analysis with qualitative methods that focus on specific examples to further interpret quantitative data, particularly for stakeholders with little expertise in reading computational outputs.

Upon reviewing academic literature on coronavirus news coverage, it is noticeable that most studies explore the crisis’ initial months (Fox Citation2021; Hart, Chinn, and Soroka Citation2020; Hubner Citation2021; Mach, Salas Reyes, and Pentz Citation2021). Respective studies focus on societal effects of corona news, such as polarisation and shifting public attitudes, and not directly on journalism evaluation. Research that specifically turns to critical reflection on journalistic practice has investigated data literacy's growing importance for journalists (Nguyen et al. Citation2021), remote work's impact on professional routines (García-Avilés Citation2021), and storytelling in corona coverage (Nee and Santana Citation2022). These studies address pandemic-specific journalistic challenges: critical reporting with quantitative data, adapting to remote work, and eschewing sensationalism in corona reporting.

Focusing on the pandemic's early stages limits insights into how it has influenced journalistic practice over time, which often changes throughout a health crisis (Oh et al. Citation2012). This indicates that analyses should include the endemic phase for completeness. Additionally, current computational studies often examine specific aspects of corona news, like dominant topics (Gong and Firdaus Citation2022), topic-tone combinations (Fox Citation2021), main figures (Hart, Chinn, and Soroka Citation2020), or sentiment and framing (Hubner Citation2021). A broader understanding of journalism's pandemic role necessitates exploring and evaluating reporting's multiple dimensions for comprehensive self-evaluation.

Research Questions

A senior editor asked the researchers to critically review Dutch newspapers’ pandemic coverage, aiming for systematic, empirical insights for critical reflection and spotting areas for improvement in crisis reporting. The study centred on four research questions:

How did journalists and editors reflect on the journalistic quality of their reporting during the COVID-19 pandemic?

In terms of topics and thematic emphases, how did Dutch newspapers cover the COVID-19 pandemic? (Setting the public agenda and monitoring societal issues)

How diverse was the reporting on COVID-19? What societal actors were represented, and how did this contribute to offering a platform for discussion and analysis?

What role did different types of newspapers play in reporting on COVID-19, particularly in terms of informing the public and offering interpretation and analysis?

By exploring these questions with computational and qualitative methods, the authors created a report to spark internal debate among the newspaper's editors-in-chief. The findings are shared in this paper, highlighting the newspapers’ dedication to transparency.

Methods and Data

Thematic Analysis of Metajournalistic Discourse

First, we investigated how news professionals evaluated their work by examining their engagements with the public on Dutch journalism's role during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the Netherlands, journalists and media professionals frequently engaged in public dialogues about COVID-19 news coverage through various platforms, including conversations, podcasts, editor blogs, and TV shows. These formed the intricate sites of metajournalistic discourse, defined by Carlson (Citation2015, 13) as “where actors inside and outside of journalism debate and contest what the news ought to look like by presenting definitions, setting boundaries, and seeking legitimacy.” Through these outlets, journalists offered public accountability and assessments of their crisis reporting practices, while seeking justification and legitimisation for their approaches. We analysed diverse media interactions to capture reflections on journalistic practices. Starting with a roundtable called “Journalism in Times of Crisis” at De Balie, we broadened the analysis through including additional media moments identified via the snowballing technique (appendix 1). Using thematic analysis, (Braun and Clarke Citation2006), we reveal dominant themes and key arguments in the discussions about journalism during the pandemic.

Mixed Methods Analysis of COVID-19 Coverage

To tackle the remaining research questions and explore trends in Dutch COVID-19 news over time, our study utilises a mixed-methods design, blending computational automated text analysis with qualitative approaches to handle a large volume of articles. Influenced by digital humanities, we first applied quantitative “distant reading” to detect broad patterns (Janicke et al. Citation2015). This strategy enables a deeper exploration of these patterns through “close reading” techniques, aiming to “capture the trends and details of a situation” (Ivankova, Creswell, and Stick Citation2006, 3).

The quantitative methods enabled exploration of fundamental questions such as what, who, where, when, and how often, helping to move beyond anecdotal evidence and “gut feeling” often found in COVID-19 journalism evaluations. These techniques were crucial to assess if criticisms of news coverage were empirically grounded. However, the limitations of computational methods in capturing linguistic nuances highlighted the need for close readings to better grasp discourse aspects such as sentiment, tone, complexity, accessibility, and framing. Our methodology represents a “sequential explanatory design” (Ivankova, Creswell, and Stick Citation2006), starting with computational analysis to outline topics and stakeholders, followed by qualitative research to provide depth and context. For instance, topic modelling showed “Research & Vaccinations” as an important topic involving various societal actors, while qualitative analysis delved into how journalists handled this contentious issue in more detail (e.g., thematic foci within vaccination news, contexts in which stakeholders were referenced, use of headlines). Therefore, we included a critical discussion of representative articles per topic to link computational findings closer with journalistic practice. Explaining and enriching the quantitative findings qualitatively also made our insights more accessible for journalists.

The analysis unfolded in five phases: (1) Data collection from LexisNexis for the period between October 2019 and October 2022, covering regional and national newspapers; (2) Pre-processing and filtering of COVID-19 related articles; (3) Topic modelling for identifying key frames and themes in Dutch COVID-19 news; (4) Named Entity Recognition (NER) for extracting significant social entities from the texts; (5) “Close reading” of a subset of articles to add qualitative depth.

The news articles were sourced from four major national newspapers—AD/Algemeen Dagblad, de Volkskrant, Trouw, and Het Parool—plus 16 regional papers (appendix 2), all owned by DPG Media. Our research collaboration included access to their archives for this study. DPG Media is a dominant player in the Dutch newspaper market, holding about 53% of total market circulation as of 2019. The dataset comprises all articles published by these outlets within the designated timeframe, (N = 2,141,758), covering both COVID-19-related and unrelated materials. For focused text analysis, we specifically curated a subset of COVID-19-related articles (). This subset was compiled by filtering for articles mentioning COVID-19-related keywords at least once in the title or more than twice within the text (appendix 3).

Table 1. Corpus corona-related articles.

The study predominantly analysed print newspaper articles, as they likely feature the most significant news stories of the day, reflecting crucial agenda-setting choices due to the limited space in print media. This format also allows for an examination of how topics are positioned, shedding light on editorial perceptions of issues. Topic modelling, using Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA; Citation2003), identified thematic clusters after text pre-processing with the GENSIM Mallet package in Python. Eighteen topics were discerned based on coherence scores, with each manually labelled and validated through random article samples per topic. For certain analyses, these topics were grouped into eight larger meta-topics. Named Entity Recognition (NER) was performed using the Spacy package (model: nl_core_news_lg) to extract proper nouns.

A limitation of computational methods is their inability to critically assess the diverse roles newspapers played in the corona discourse, such as how they supported, contradicted, or related to one another. This required detailed article analyses of context and reporting style. We focused on four topics identified computationally for qualitative exploration: “Research & Vaccinations”, “Hospitals & Healthcare”, “Education”, and “Public Events.” The close readings sought to delineate each newspaper's reporting approach, selecting articles from each topic's peak periods throughout the pandemic. Insights from “Research & Vaccinations” exemplify the qualitative analysis. The reported results illustrate their potential contribution to metajournalistic discourse rather than providing an exhaustive discussion of each investigated aspect, which is beyond this study's scope.

Results

Dutch Metajournalistic Discourse about Covid-19 Reporting

A summary of self-reflective media moments highlights three primary concerns in COVID-19 news coverage among Dutch journalists: the portrayal of media as conduits for government information, a perceived knowledge crisis, and the role of journalists in preventing panic. Identifying these concerns sheds light on the motivations behind our commission to empirically research COVID-19 coverage.

The first concern is the overreliance on government sources. Critics argue that journalists’ dependency on governmental institutions such as the health ministry (RIVM) led to a lack of critical reporting on government policies. This ties to worries that the media's focus on medical aspects might have overlooked wider societal impacts (De Balie Citation2022). Pieter Klok, editor-in-chief of de Volkskrant, defended this approach, suggesting that too much criticism of e.g., lockdowns could undermine public adherence, risking public health (Morskate Citation2020). Additionally, restrictions on journalists’ mobility prompted discussions on potential exemptions in future crises (KRO-NCRV Citation2021). These critiques mainly highlight issues in early pandemic reporting, without denying journalism's role in emphasising the gravity of the crisis or the importance of public health measures.

The second point pertains to challenges of covering the pandemic as a complex and opaque topic for non-medical experts. Linking to the above, journalists’ limited expertise and time pressure resulted in heavy reliance on government sources (KRO-NCRV Citation2021). Some journalists pointed out that, retrospectively, more diverse disciplines and forms of expertise should have been consulted for reporting about the pandemic’s various dimensions. Journalists should have included experts in medical ethics, psychology, and governance, along with considering other knowledge forms, such as caregivers’ experiences in nursing homes, rather than focusing mainly on virologists (KRO-NCRV Citation2021). The media's focus on medical and government sources led to a delayed recognition of societal challenges, such as the adverse conditions in nursing homes and the effects of school closures on youth (De Balie Citation2022). Essentially, news outlets should have broadened their view on the pandemic's societal and policy implications, adopting a more critical approach to government policies and integrating personal stories from affected individuals (De Balie Citation2022).

The third point examines journalism's duty to avert public panic through responsible reporting. In February 2020, Lucas van Houtert, chief editor of Brabants Dagblad, defended his newspaper's reporting as factual, useful, and balanced against accusations of inciting corona panic. Nonetheless, sensational headlines and speculative reporting can adversely affect public sentiment during uncertain periods, underscoring the need to strike a balance between thorough crisis reporting and avoiding unfounded fears that might disrupt public discourse (Argos Medialogica Citation2020).

In summary, journalists offered various critiques and suggestions for improvement through critical-reflective meta-discourse during the pandemic. However, these insights frequently stemmed from personal experiences and anecdotal evidence.

The COVID-19 Pandemic Through the Lens of News Reporting

Analysing the timing, extent, and duration of news media's focus on COVID-19 related issues highlights the dynamics of coronavirus reporting and its role in shaping public agendas, especially regarding topic diversity.

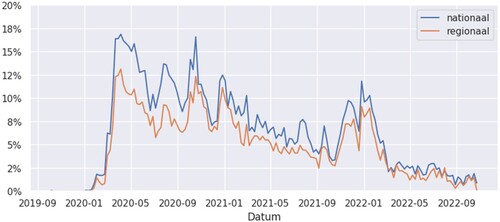

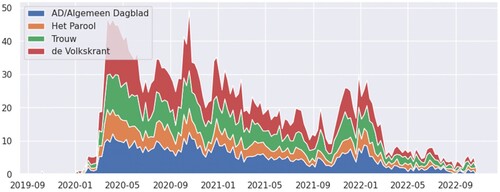

Coronavirus articles began proliferating in early 2020, coinciding with the first confirmed case in the Netherlands. Despite their prominence throughout the study period, coronavirus-related articles formed a minor fraction of all content. Notably, in the four national newspapers, coronavirus-focused articles averaged around 6% of all publications over the pandemic's three-year span ().

Table 2. Proportion of corona-articles in national newspapers.

Although the share of coronavirus-related articles may appear small, it is crucial to understand that the volume of articles does not directly correlate with their importance, quality, or coverage depth. In agenda-setting, articles’ placement within the news hierarchy is key, arguably more than quantity. Articles given front-page prominence are considered more significant than others. The four national newspapers often placed coronavirus articles within the first ten pages, indicating their priority.

shows the distribution of corona articles in both national and regional newspapers, with national outlets consistently offering more comprehensive coverage than regional ones. The peaks and valleys in publication volume generally align across both national and regional platforms, suggesting a consistent pattern in coronavirus reporting frequency at both levels. This uniformity could result from regional newspapers frequently republishing content from national sources.

Comparing the four national newspapers () shows a similar pattern of highs and lows in the number of corona-related articles. This implies two characteristics of Dutch corona reporting: (1) national newspapers attributed similar importance to corona-related issues throughout the pandemic years, and (2) they likely reported on the same topics and developments simultaneously. Media attention, gauged by publication volume, was nearly synchronous among the outlets.

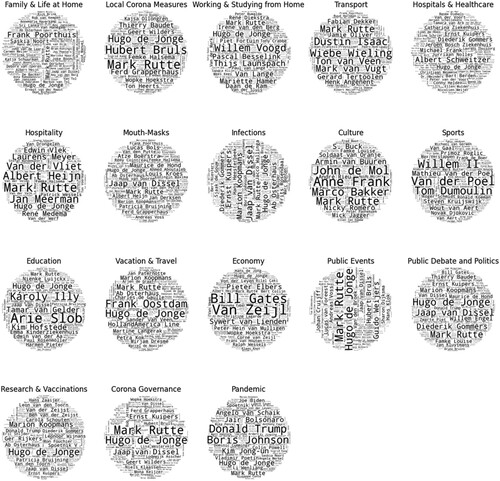

To explore how news coverage evolved during the pandemic, we analysed prevalent themes in the articles. presents the eighteen topics identified, including the top ten keywords for each and their average distribution in the corpus. These results show that news media generally reflected the diverse impacts of the pandemic across society. COVID-19 quickly moved beyond being a mere health issue, influencing politics, economy, education, and culture. This broadening focus required journalists to tackle the pandemic's extensive effects across various societal areas simultaneously.

Table 3. Topics as Emphasis Frames in Dutch Corona News.

The topics range from the personal sphere (“family & life at home”; “working & studying from home”), local measures, to national and international politics (“corona governance,” “pandemic,” “public debate & politics”). Most topics accounted for an average of 5% to 6% of news reporting. There are some exceptions, such as “hospitals & healthcare” (8.1%) and “infections” (11.8%), which were covered more frequently, while “working & studying from home” (3.4%), “transport” (3%), and “education” (3.5%) received less coverage. These observations reflect the overall distribution of all topics across all articles and do not necessarily suggest a lack of detailed coverage on these topics at certain times. They do, however, prompt reflection on the attention given to various aspects of the pandemic, leading to questions about the proportion and distribution of reporting about these topics. Here, a comparison between national and regional newspapers points to notable differences, which imply different functions for each ().

Table 4. Distinct topics per newspaper type (chi2, p-values < 0.05).

Topics emphasised in regional papers often receive less attention in national ones, and vice versa. Regional outlets covered local coronavirus impacts, while national newspapers reported about broader national and global developments, with less emphasis on local details. Thus, national, and regional newspapers play complementary roles.

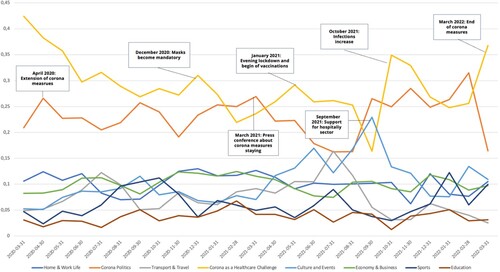

To further understand which topics received the most coverage over time and to track broader developments, the eighteen topics were grouped into eight “meta-topics,” based on their thematic similarities (see ).

Table 5. Meta-Topics.

shows the time-based distribution of meta-topics, with the y-axis indicating the chance of an article discussing one or more meta-topics. For example, in March 2020, articles mainly treated the coronavirus as a healthcare issue, with politics being significant but secondary. Reporting on other societal areas was less prominent in early coverage.

A notable shift occurred in September 2021, highlighted by discussions on government support for the hospitality industry, temporarily surpassing healthcare. News coverage peaks often matched government announcements on pandemic trends, like infection rates and hospitalisations, or policy updates on social distancing, mask mandates, and vaccinations. While the link between COVID-19 reporting and government actions is clear, it does not necessarily imply uncritical journalism. Yet, this relationship prompts vital questions about the dynamics between politics and journalism, including dependencies and power structures. Distinguishing between news that merely responds to events and news that actively shapes debates is challenging, as both can occur simultaneously. News media can trigger debates, influencing public agendas by sustained coverage. However, in crises like COVID-19, reporting typically relies on external, often governmental, sources due to the situation's unpredictability and complexity, leading to a more reactive journalistic approach. Investigating this relationship further, especially through interviews with journalists and editors, would provide deeper insights but is beyond this study's scope.

The topic analysis shows that Dutch newspapers provided comprehensive coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic as it evolved. Legacy media, including regional publications, increased their focus with the pandemic's onset in the Netherlands, driven by the news values of proximity and the event's significance. Political and medical issues were central in the coverage, but the reporting also covered the pandemic's wide-ranging social, cultural, economic, and political impacts. COVID-19 was quickly recognised as a complex challenge affecting more than healthcare, especially as hospitals faced case surges, leading to government measures like lockdowns that altered daily life. However, the coverage of other societal impacts, such as on education and remote work, was less pronounced compared to health and political topics. This prompts questions about potential overemphasis on the pandemic's medical aspects to the detriment of its wider societal consequences.

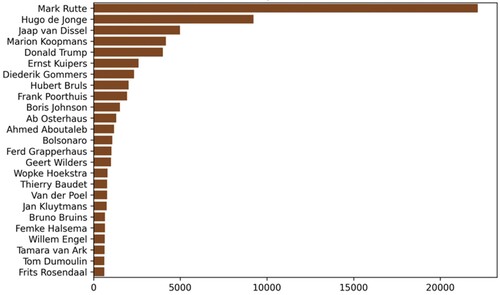

The Dominant Societal Actors in COVID-19 News

The Dutch metajournalistic discourse highlighted a heavy reliance on government sources. Beyond thematic focuses, it is vital to examine the spectrum of societal actors featured in crisis reporting to explore diversity or lack thereof in news reporting. The NER analysis () shows that Dutch politicians like Mark Rutte and Hugo de Jonge, along with health experts such as Jaap van Dissel, Diederik Gommers, and Marion Koopmans, were most frequently mentioned. These experts, crucial to the Outbreak Management Team (OMT) advising on pandemic responses, underscore the influence of specific viewpoints on COVID-19 policy. Despite some dissenting voices like virologist Ab Osterhaus, who criticised government policies, news media mainly focused on those directly involved in policymaking. This raises questions about the need for incorporating wider perspectives.

These results are consistent with (Mellado et al. Citation2021) observation of a focus on political figures during the COVID-19 crisis, which required them to be at the forefront. Additionally, mayors like Hubert Bruls, Ahmed Aboutaleb, and Femke Halsema, alongside international figures such as Boris Johnson and Jair Bolsonaro, were often cited, highlighting the pandemic's reach across various societal levels, from local to international. Our examination of frequently mentioned societal actors found uniformity between different news outlets: high-ranking government officials and healthcare experts were consistently spotlighted across them ().

Politicians and medical experts are also the most cited stakeholders across all topics. However, further review of the most mentioned individuals per topic () reveals that corona reporting pursued expert insights within certain crisis-related sub-discourses. For example, Dutch psychologist Thijs Launspach was often quoted in pieces about remote work and study, while Jan Meerman from INRetail, representing entrepreneurs, was frequently mentioned in discussions on the hospitality industry. Although these experts may not be household names, journalists seem to have valued their specialised knowledge. This highlights the need for further exploration into how journalists chose sources for reporting on the coronavirus's impact on specific sectors.

In summary, COVID-19 coverage was primarily driven by politicians, government officials, and medical experts, especially those shaping policy. The range of sources is mainly limited to well-known figures in politics, healthcare, and business, indicating a narrow array of perspectives that predominantly represent elite views. Mellado et al. (Citation2021) argue that the common presence of political figures during the pandemic is due to its nature, which “requires dramatic intervention into patterns of social life and affects all societal aspects, a crisis that inevitably places political authorities in a position of responsibility” (1279–1280).

The Role of Different Newspapers in the Dutch Corona Discourse

For close readings, articles were chosen based on the highest monthly publication frequency for each topic, ensuring at least one peak per newspaper was included. The qualitative analysis examined journalistic language in specific COVID-19 reporting, contextualisation of societal actors, and sourcing of information. We present a summary of insights for the “Research & Vaccinations” topic, which includes articles on general COVID-19 research and the development, production, and distribution of vaccines. Initially, the pandemic was often compared to the flu. As it progressed, focus shifted towards vaccine development. Later discussions emphasised vaccine benefits and risks, vaccine types, legal issues, vaccination campaigns, and booster shots. Public interest intensified with new research, healthcare, and policy developments. From 2021, attention moved to vaccination policies and overall pandemic management. For instance, in April and May 2020, the coverage mainly provided information and context about the virus, whereas by January 2021, as vaccinations started in the Netherlands, articles included critical perspectives and opinion pieces on slow governmental action or controversial measures.

A comparative analysis of the four national newspapers revealed difference in coverage patterns. For example, de Volkskrant allocated more space to this topic in September 2020, August 2021, and March 2022 compared to its counterparts. In contrast, Het Parool diverged from covering this topic in August 2022 when other outlets increased their focus. Moreover, AD saw a reduction in coverage from August to September 2021, unlike de Volkskrant, which experienced a surge.

Each newspaper exhibits a distinct approach to reporting on research and vaccinations. AD tends to provide accessible information but sometimes lacks depth, with headlines that can be interpreted as sensational or speculative, risking polarisation or fear. This somewhat mirrors the alarmist tone observed in Dutch media during the 2009 H1N1 flu outbreak. De Volkskrant emphasises scientifically grounded articles addressing readers’ concerns and hesitations about vaccines. Trouw combines informative articles with personal stories, maintaining a generally positive stance towards vaccination. Het Parool, however, pays relatively limited attention to the subject.

Collectively, these newspapers fulfil various journalistic roles: informing, monitoring, facilitating discussion and opinion, and offering interpretation and analysis. In terms of analysis and explanation, Dutch COVID-19 coverage blends informative reporting with interpretative commentary. Interpretative pieces probe fundamental questions about the virus, its transmission, and the adequacy of measures against it. Articles also critique government policies by providing evaluations. In opinion pieces, arguments are articulated for or against specific COVID-19 strategies, like booster shots. Nevertheless, the focal themes and key figures largely revolve around governmental policies and the public's demand for information, particularly during the pandemic's early stages.

Discussion

The presented results aimed to provide the commissioning newspaper with empirical data for critical self-reflection, thereby allowing us to explore the link between mixed-methods research of news reporting and metajournalistic discourse. We think such research efforts can enrich and inform metajournalistic discourse. The findings probed the performance of sampled Dutch news media against five normative functions: informing, monitoring, providing platforms for discussion and opinion, offering interpretation and analysis, and setting public agendas.

How did Dutch newspapers cover the COVID-19 pandemic with respect to topics and thematic emphases? The coronavirus pandemic posed a complex challenge to society and underscored the need for independent, expert, and accurate journalism. As far as the journalistic roles of informing and agenda-setting are concerned, Dutch newspapers devoted attention to the unfolding coronavirus pandemic right from the start. Generally, the coverage focused on the intensification, diversification, and politicisation of the various societal consequences of the virus. The pandemic and its multifaceted effects dominated the news media agendas for a significant part of the analysed period. In general, we observe that a considerable amount of attention in the reporting was devoted to healthcare issues and politics, as shown in the dominant topics “Corona as a Healthcare Challenge” and “Corona & Politics.” Taken together, the various newspaper articles provided a broad overview of the increasing complexity and multidimensionality of the pandemic. However, the number of articles that summarised this complexity was found to be limited. Many articles represented a standpoint from a single perspective. This does not mean that there were no articles that juxtaposed conflicting perspectives, but even these articles appeared to have a clear perspective on the direction that the coronavirus measures should take. The question remains as to how complex and comprehensive a single news article can be. Corona reporting also was often more reactionary than leading, but that is strongly linked to the nature of the pandemic as a profound societal crisis. Criticism here should consider the unfamiliarity and uncertainty of the general developments and the partially unpredictable consequences.

How diverse was the reporting around corona? What societal actors were represented? As criticised by Dutch journalists in the metajournalistic debate, reporting on the coronavirus was dominated by politicians, government representatives, and medical experts, particularly those involved with the Outbreak Management Team (OMT). Within specific topics, there are some variations, with domain experts appearing more dominant, but overall, diversity seemed confined to influential individuals in politics and healthcare. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that emphasis was placed on Western politicians. In terms of providing a platform for discussion and opinion, this suggests that the diversity of societal actors was somewhat limited to certain elites.

What role did different types of newspapers play in the corona reporting? Generally, we see considerable alignment between the different newspapers concerning the thematic emphases in their corona reporting. However, clear differences emerge from the qualitative analysis that pertains to deviations in the style of reporting and framing of specific issues. In the example of “Research & Vaccinations,” this observation can inform further critical reflection. What stood out was that some newspapers published accessible articles that aim to provide easy-to-understand reporting about pandemic events. Yet, these newspapers also leaned towards more sensational and speculative headlines. Others, such as de Volkskrant, assumed an informative role, frequently grounding their information in scientific research. The role of individual journalists and their expertise is a potentially decisive factor here, as they can set the overall agenda for covering crisis-related issues with a specific style of reporting. This point needs further research.

There are several recommendations that stem from this analysis, specifically related to (1) the utilisation of data and analytics for monitoring news coverage beyond mere business goals and (2) fulfilling the five normative commitments of journalism in crisis situations. Many news publishers already harness various data analyses to monitor their journalistic output for business aims, particularly in the context of their online platforms. These analyses deploy computational methods such as topic modelling and NER. While these methods are often employed for business-centric purposes like personalised content recommendations, they can serve to assess and evaluate journalistic practice based on normative objectives (informing, scrutinising, providing a platform for discussion and opinion, interpreting, and analysing, and agenda-setting), and relevant performance metrics. If “contemporary journalism [is] a complex and evolving ensemble of attitudes, activities, emotions, perceptions, and values” (Deuze and Witschge Citation2020, 29), then critical reflection supported by empirical insights won with computational methods enables journalists to hold themselves accountable to the very standards that they set for themselves—and that society projects onto the profession in its diverse forms. While the report was created based on a request, which already indicates a commitment to reflection and accountability, the analyses indeed stimulated critical discussion among editors when they were presented with the results. Our research contributed to their discourse on how journalism legitimises itself through reflection and accountability. Computational methods introduced an added layer of complexity to this process. Of course, we also cannot ignore that empirical data can be used strategically to help establish cultural authority through the suggestions of reflective and accountable practices.

What is important to underline here is that we do not advocate for another sort of “data-solutionism” but rather want to point out how computational analyses already in place can be critically integrated into more systematic approaches to critical reflection as a gateway to accountability for journalistic organisations. We offered here only a summarised overview of relatively common methods for automated text analysis (Atteveldt, Trilling, and Calderón Citation2022). Additional insights could be won with e.g., word embeddings for further refining topic models and sentiment analysis. Also, more complex methods that consider the attribution of space to cited sources could help with further exploring how journalists contextualise and prioritise cited actors. With the field of natural language processing constantly advancing, researchers and newsrooms alike should keep an eye on new methodologies and their potential value for self-evaluation and critical reflection. Obviously, implementing the sketched-out methodology requires a commitment of resources and the availability of expertise. Importantly, validation through close readings and critical discussion of findings are essential to distil useful insights from computational analysis and to avoid “data myopia.”

Conclusion

The present paper explored the use of computational methods to critically examine reporting on the corona pandemic in Dutch news outlets owned by DPG Media. Specifically, it analysed several dimensions of the reporting related to the functions of journalism: media attention to pandemic-related developments, topics, societal actors, and the roles of different newspapers. The study provides a bird's-eye view of almost three years of COVID-19 reporting across multiple newspapers. For application in editorial rooms, further granularity would be necessary, enabling detailed examinations of specific newspapers or individual articles. This would also facilitate investigations into how journalistic practices met or failed to meet their normative objectives in particular contexts or during specific “COVID-19 episodes” (e.g., riots, anti-vaxxer movements, anti-racism protests).

Given the absence of benchmarks for coronavirus coverage, making definitive statements about the diversity of coverage and societal actors involved poses a challenge. These are crucial discussions that should take place among editors and journalists. A significant limitation is that these analyses only reflect reported content, not what is overlooked. Moreover, incorporating additional computational methods could extend the analyses to quantify, for example, the alarmist tone identified in close readings by automating sentiment analysis for news headlines.

While we provided post-hoc reflection, we see computational methods as valuable for ongoing reflection. The empirical study of news reporting can assist editors and journalists in continuously reflecting on their practices. If integrated into dashboards in editorial rooms, this could serve as a tool for monitoring self-determined measures alongside these indicators. Despite computational methods potentially oversimplifying complexities of news reporting, we found editors and journalists skilled at interpreting and elucidating these insights. They can also discuss their desired roles or normative standards using these indicators. As noted, these analyses are already possible but require repurposing. However, there is a risk of potential misuse of these dashboards. We envision their function akin to a speedometer, aiding journalists in making informed decisions about what, who, and how they write about various topics.

Finally, it is important to address the conception of the present research project, initiated by practitioners in the field with a specific interest in having their journalistic work evaluated. On the one hand, this steered our research outlook towards the practical dimensions and implications of journalistic self-evaluation and metajournalistic discourse. While all of this is closely linked to journalism’s broader public mission and societal function, it nevertheless sketched out our analytical focus from the outset: we embarked on assessing corona reporting from a decidedly normative -and specific Western European perspective- and in terms of how our insights can inform concrete future actions among journalists. Consequently, other critical questions, such as what role corona news reporting played in public discursivity around the pandemic at a societal level within dynamic digital media ecologies, formed more of a backdrop than a primary research interest. On the other hand, the mission statement that we received was broad and sufficiently flexible to allow us to explore different critical-empirical approaches to observe and reflect on journalistic practice. The journalists’ interest in critical self-reflection as part of their professional self-understanding offered a valuable opportunity to link academic research to practical needs, from determining the research objective to the discussion insights in a transdisciplinary dialogue.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (16.1 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Alessandra Polimeno and Sahra Mohamed for the contributions to the analyses.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Argos Medialogica. 2020, May 19. “Ziektebeeld - over de media en het coronavirus.” NPO Start. https://www.npostart.nl/medialogica/19-05-2020/VPWON_1310564.

- Atteveldt, W. Van, D. Trilling, and C. A. Calderón. 2022. Computational Analysis of Communication. Hoboken, USA & Chichester, UK: Wiley Blackwell.

- Bardoel, J., and L. d‘ Haenens. 2004. “Media Responsibility and Accountability.” New Conceptualizations and Practices 29 (1): 5–25. https://doi.org/10.1515/comm.2004.007.

- Bastian, M., N. Helberger, and M. Makhortykh. 2021. “Safeguarding the Journalistic DNA: Attitudes Towards the Role of Professional Values in Algorithmic News Recommender Designs.” Digital Journalism 9 (6): 835–863. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1912622

- Bertrand, C. J. 2018. Media Ethics and Accountability Systems. New Brunswick, New Jersey : Routledge.

- Blei, D. M., A. Y. Ng, and M. I. Jordan. 2003. “Latent Dirichlet Allocation.” Journal of Machine Learning Research.

- Bounegru, L., and J. Gray. 2021. The Data Journalism Handbook: Towards A Critical Data Practice. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9789048542079.

- Brants, K. 2013. “Trust, Cynicism, and Responsiveness: The Uneasy Situation of Journalism in Democracy.” In Rethinking Journalism. Trust, Truth and Performance in a Transformed News Landscape, edited by C. Peters, and M. Broersma, 15–27. Milton Park and New York: Routledge.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Bruns, A. 2009. “News Blogs and Citizen Journalism: New Directions for e-Journalism.” In e-Journalism: New Media and News Media, edited by K. Prasad, 101–126. New Delhi, India: B.R. Publishing Corporation.

- Carlson, M. 2015. “Metajournalistic Discourse and the Meanings of Journalism: Definitional Control, Boundary Work, and Legitimation.” Communication Theory.

- Christians, C. G., T. Glasser, D. McQuail, K. Nordenstreng, and R. A. White. 2010. Normative Theories of the Media: Journalism in Democratic Societies. Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press.

- Christin, A. 2020. Metrics at Work: Journalism and the Contested Meaning of Algorithms. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- De Balie. 2022. “Journalistiek in Crisistijd.” https://debalie.nl/programma/media-in-crisistijd-26-11-2022/.

- de Bruin, K., Y. de Haan, R. Vliegenthart, S. Kruikemeier, and M. Boukes. 2021. “News Avoidance During the COVID-19 Crisis: Understanding Information Overload.” Digital Journalism 9 (9): 1286–1302. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1957967.

- De Coninck, D., L. d'Haenens, and K. Matthijs. 2020. “Forgotten key Players in Public Health: News Media as Agents of Information and Persuasion During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Public Health 183: 65–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2020.05.011.

- Deuze, M. 2019. “What Journalism is (not).” Social Media + Society 5 (3), https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119857202.

- Deuze, M., and T. Witschge. 2020. Beyond Journalism. Cambridge: Polity.

- Diakopoulos, N. 2019. Automating the News: How Algorithms are Rewriting the Media. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

- Figenschou, T. U., and K. A. Ihlebæk. 2019. “Challenging Journalistic Authority.” Journalism Studies 20 (9): 1221–1237. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2018.1500868.

- Fox, C. A. 2021. “Media in a Time of Crisis: Newspaper Coverage of COVID-19 in East Asia.” Journalism Studies 22 (13): 1853–1873. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2021.1971106

- Frischlich, L., L. Kuhfeldt, T. Schatto-Eckrodt, and L. Clever. 2023. “Alternative Counter-News use and Fake News Recall During the COVID-19 Crisis.” Digital Journalism 11 (1): 80–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2022.2106259.

- García-Avilés, J. A. 2021. “Journalism as Usual? Managing Disruption in Virtual Newsrooms during the COVID-19 Crisis.” Digital Journalism.

- Garman, A. 2023, September 20. “The Public Sphere and Journalism.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. Accessed February 6, 2024. https://oxfordre-com.proxy.library.uu.nl/communication/view/10.1093acrefore/9780190228613.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228613-e-880.

- Gong, J., and A. Firdaus. 2022. “Is the Pandemic a Boon or a Bane? News Media Coverage of COVID-19 in China Daily.” Journalism Practice 18 (3): 621–641. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2022.2043766

- Hanitzsch, T., and T. P. Vos. 2018. “Journalism Beyond Democracy: A new Look Into Journalistic Roles in Political and Everyday Life.” Journalism 19 (2): 146–164. https://doi-org.proxy.library.uu.nl/10.1177/1464884916673386. doi: 10.1177/1464884916673386

- Hart, S. P., S. Chinn, and S. Soroka. 2020. “Politicization and Polarization in COVID-19 News Coverage.” Science Communication 42 (5): 679–697. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547020950735

- Henke, J., L. Leissner, and W. Möhring. 2020. “How Can Journalists Promote News Credibility? Effects of Evidences on Trust and Credibility.” Journalism Practice 14 (3): 299–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2019.1605839.

- Hubner, A. 2021. “How did we get Here? A Framing and Source Analysis of Early COVID-19 Media Coverage.” Communication Research Reports 38 (2): 112–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2021.1894112

- Ivankova, N. V., J. W. Creswell, and S. L. Stick. 2006. “Using Mixed-Methods Sequential Explanatory Design: From Theory to Practice.” Field Methods 18 (1): 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05282260

- Jandura, O., and K. Friedrich. 2014. “Quality of Political Media Coverage.” In Handbook of Communication Science: Political Communication, edited by Carsten Reinemann, 351–373. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

- Jänicke, S., G. Franzini, M. F. Cheema, and G. Scheuermann. 2015. Eurographics Conference on Visualization (EuroVis) State of the Art Report (STAR). Eurographics Association.

- Kristensen, L. M. 2023. “Audience Metrics: Operationalizing News Value for the Digital Newsroom.” Journalism Practice 17 (5): 991–1008. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2021.1954058.

- KRO-NCRV. 2021. “Jet Bussemaker: ‘Meer tegenspraak en reflectie gewild over het coronabeleid’.” https://www.nporadio1.nl/nieuws/cultuur-media/1bd1ad01-dfa6-4bdb-a292-63aafd2fe1ed/jet-bussemaker-meer-tegenspraak-en-reflectie-gewild-over-het-coronabeleid.

- Mach, K. J., R. Salas Reyes, B. Pentz, J. Taylor, C. A. Costa, S. G. Cruz, K. E. Thomas, et al. 2021. “News Media Coverage of COVID-19 Public Health and Policy Information.” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 8: 220. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00900-z

- McNair, B. 2009. “Journalism and Democracy.” In The Handbook of Journalism Studies, edited by Karin Wahl-Jorgensen and Thomas Hanitzsch, 257–269. New York: Routledge.

- McQuail, D. 2003. Media Accountability and Freedom of Publication. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Meier, K. 2023. “Quality in Journalism.” In The International Encyclopedia of Journalism Studies, edited by T. P. Vos, F. Hanusch, D. Dimitrakopoulou, M. Geertsema-Sligh, and A. Sehl. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118841570.iejs0041.

- Mellado, Claudia, Daniel Hallin, Luis Cárcamo, Rodrigo Alfaro, Daniel Jackson, María Luisa Humanes, Mireya Márquez-Ramírez, et al. 2021. “Sourcing Pandemic News: A Cross-National Computational Analysis of Mainstream Media Coverage of COVID-19 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.” Digital Journalism 9 (9): 1261–1285. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1942114.

- Moran, R. E., and S. J. Shaikh. 2022. “Robots in the News and Newsrooms: Unpacking Meta-Journalistic Discourse on the use of Artificial Intelligence in Journalism.” Digital Journalism 10 (10): 1756–1774. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2022.2085129.

- Morskate, M. 2020, December 18. “Ook onze eigen hoofdredacteur dacht dat het allemaal wel mee zou vallen met corona.” De Volkskrant. https://www.volkskrant.nl/nieuws-achtergrond/ook-onze-eigen-hoofdredacteur-dacht-dat-het-allemaal-wel-mee-zou-vallen-met-corona~bad4d103/.

- Nee, R. C., and A. D. Santana. 2022. “Podcasting the Pandemic: Exploring Storytelling Formats and Shifting Journalistic Norms in News Podcasts Related to the Coronavirus.” Journalism Practice 16 (8): 1559–1577. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2021.1882874.

- Nguyen, A., X. Zhao, B. Lawson, and D. Jackson. 2021. “Reporting from a Statistical Chaos: Journalistic Lessons from the First Year of Covid-19 Data and Science in the News.” Bournemouth University, Royal Statistical Society, Association of British Science Writers.

- Oh, H. J., T. Hove, H. J. Paek, B. Lee, H. Lee, and S. K. Song. 2012. “Attention Cycles and the H1n1 Pandemic: A Cross-National Study of US and Korean Newspaper Coverage.” Asian Journal of Communication 22 (2): 214–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2011.642395

- Perreault, M. F., and G. P. Perreault. 2021. “Journalists on COVID-19 Journalism: Communication Ecology of Pandemic Reporting.” American Behavioral Scientist 65 (7): 976–991. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764221992813.

- Perreault, G., M. F. Perreault, and P. Maares. 2022. “Metajournalistic Discourse as a Stabilizer Within the Journalistic Field: Journalistic Practice in the Covid-19 Pandemic.” Journalism Practice 16 (2-3): 365–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2021.1949630.

- Quandt, T., and K. Wahl-Jorgensen. 2021. “The Coronavirus Pandemic as a Critical Moment for Digital Journalism.” Digital Journalism 9 (9): 1199–1207. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1996253.

- Ramaker, T., J. van der Stoep, and M. Deuze. 2015. “Reflective Practices for Future Journalism: The Need, the Resistance and the way Forward.” Javnost - The Public 22 (4): 345–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2015.1091622.

- Schön, Donald A. 1983. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. Vol. 5126. Basic Books.

- Standaert, O., T. Hanitzsch, and J. Dedonder. 2021. “In Their own Words: A Normative-Empirical Approach to Journalistic Roles Around the World.” Journalism 22 (4): 919–936. https://doi-org.proxy.library.uu.nl/10.1177/1464884919853183. doi: 10.1177/1464884919853183

- Urban, Juliane, and W. Schweiger. 2014. “News Quality from the Recipients’ Perspective.” Journalism Studies 15 (6): 821–840. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2013.856670.

- Veerbeek, J., K. F. van Es, and E. Müller. 2022. “Public Broadcasting and Topic Diversity in The Netherlands: Mentions of Public Broadcasters’ Programming in Newspapers as Indicators of Pluralism.” Javnost 29 (4): 420–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2022.2067956.