ABSTRACT

This paper introduces the concept of brokerage to the scholarship of local news. Drawing on anthropological conceptions of actors that bridge gaps in social structure and help information flow across such gaps, we propose that local journalists act as cultural brokers in rural towns. Building upon Gould and Fernandez (1989, “Structures of Mediation: A Formal Approach to Brokerage in Transaction Networks.” Sociological Methodology 19:89. https://doi.org/10.2307/270949), we employ a typology of five brokerage functions to classify relationships between local journalists, their sources, and their audiences. In addition to coordinating, itinerant, representative, liaison, and gatekeeping brokerage, our analysis reveals a novel type of brokerage: relay brokerage. We argue that this typology is useful to conceptualize information relationships in rural communities and to understand how information flows change when local journalism ebbs. Empirically, the paper presents a comprehensive study of staffing at rural newspapers in Alberta, Canada, revealing that local media are stretched so thin in many geographic areas, there is little left to cut. For scholars, this simplified media ecosystem is an environment where relationships between reporters, sources, and audiences may be more easily analyzed.

Introduction

“There just isn’t enough revenue to keep printing the paper,” says the discouraged owner of an independent rural newspaper in the western Canadian province of Alberta.Footnote1 Like local journalism in the United States (Abernathy Citation2020) Australia (Hess Citation2020) and the United Kingdom (Bagshaw Citation2019), Alberta’s rural news organizations have been hit hard by the contraction in local news. Many papers have cut staff, combined titles, reduced or stopped print editions, and closed competing titles. Alberta’s local news industry has been little studied so far, but the province offers an interesting case because of its vast and sparsely populated area, with local papers serving isolated rural communities. Rural journalism is a subset of local journalism—and quite distinct from urban local journalism. A distinctive trait of rural journalism is its isolation: rural publications are often the only news available in a community outside of urban and suburban centres (Mathews Citation2022). This raises the question of how rural citizens in Alberta communities can remain informed when the infrastructure for local news is degraded. This paper fills this gap in knowledge by introducing an anthropological concept — brokerage — to research on local journalism, helping to understand the positionality of a rural news reporter within a community information ecosystem.

Brokerage has been used to examine cultural flows in other contexts, and this paper argues the concept is useful to understand the current state of local journalism. Brokerage is “the process of connecting actors in systems of social, economic, or political relations in order to facilitate access to valued resources” (Stovel and Shaw Citation2012, 141). In this case, the valued resource is news. In a quantitative analysis of resource flows, Gould and Fernandez (Citation1989) propose a framework to typify five types of brokerage in social systems in general, classified according to the relationship of the broker to the other actors in the network. They distinguish between coordinating, itinerant, representative, liaison, and gatekeeping. However, the authors did not deal specifically with journalism in their conceptualization. Yanovitzky and Weber (Citation2019, 197) recognize that Gould and Fernandez’s knowledge broker categories require “further explication” in the context of journalism. This paper answers that call—first by exploring brokerage classifications in Alberta’s rural news ecosystems, and then by introducing a sixth type of brokerage, a relay brokerage, involving an additional actor, termed an interagent.

The Concept of Brokerage

The concept of brokerage stems from mid-twentieth century anthropological studies, for example Eric Wolf’s (Citation1956) work in Mexico and Clifford Geertz’ (Citation1960) research in Indonesia. “The crucial characteristics of brokers are that (a) they bridge a gap in social structure and (b) they help goods, information, opportunities, or knowledge flow across that gap” (Stovel and Shaw Citation2012). Initially, brokers were conceptualized as translating cultural practices and goods from a global culture to local cultures, and between locals and foreigners. This “cultural brokerage” concept was taken up by scholars, including contemporary ones, to explain how culture is translated from one group to another. For example, Szasz (Citation2001) employs it to describe cultural intermediaries between Indigenous American and settler cultures from the time of first contact to almost-present times. Lindquist (Citation2015) speculates on emergent types of brokerage in digital economies and at transnational scales, facilitated by neoliberal structures.

But brokerage happens at smaller scales as well. In fact, it can emerge wherever differences in a society occur: in skill differences or differences in access to particular organizational or material structures. For example, Hobbis and Hobbis (Citation2020) describe how digital brokers in Solomon Islands employ infrastructural assemblages to convey digital goods to local residents in areas without internet access. Termed mediators in Latour’s (Citation2005, 39) actor-network conceptualization of brokerage, brokers “transform, translate, distort, and modify the meaning or the elements they are supposed to carry”. Latour differentiates between mediators, who alter the material they handle, and intermediaries, who simply pass things along without transforming them. As modifying entities, these mediators wield power that intermediaries do not. In a communication context, they may shape a message to achieve an objective, be it self-serving or selfless. Latour’s definition of mediation (and brokerage) applies as well to journalistic practice as it does to cultural translation. In a move toward specificity in defining what, exactly, brokerage is, Gould and Fernandez examined resource flows in an Illinois city (Citation1989). They proposed five distinct types of brokerage which will be described later in this paper. These classifications, however, have never been applied to journalistic brokerage.

In a scholarly conception of journalistic brokerage, the reporter, story sources, and audiences are each actors in a network of relationships. Brokerage is how “intermediary actors facilitate transactions between other actors lacking access to or trust in one another” (Marsden Citation1982, 202). In the context of journalism, news workers can be viewed as brokers, gathering information from sources, translating it to increase its utility, and distributing it to audiences. Until recently, brokerage concepts were not commonly used by scholars to describe journalistic relationships (Yanovitzky and Weber Citation2019). A challenge, certainly, is that the historically large size of Western media newsrooms meant they could not be as conveniently explored through the lens of brokerage. This is because of the complexity of relationships involving news organizations, editorial managers, reporter teams and individual reporters, competing news organizations, sources, and readers is difficult to analyze. Another challenge is the disentanglement of who, exactly, is a broker: the news organization or the journalist?

We argue that in rural journalism increasingly the broker is the journalist, not the organization. Low staffing of rural news organizations has made the question somewhat moot: with so few workers at rural newspapers, the line between organization and the journalist begins to become less obvious and one may consider the relationship between journalists and their audiences with less consideration of the news organization as well. “At many community papers, if the editor gets sick, there’s no one to fill his shoes” (Lauterer Citation2006, 28). It is this position of the journalist in a network of rural actors that makes the application of brokerage to rural journalism insightful.

Sparse studies have applied brokerage concepts to journalists’ work. Drawing on Burt’s (Citation2005) conceptualization of “structural holes” — gaps between actors in a network, and entities that can bridge them, Hess employs mediated social capital theory to describe brokerage functions of individual local journalists: connecting citizens with each other (bonding and bridging) and with elites (linking) (Hess Citation2013; Hess and Waller Citation2016, 112). In a bonding role, journalists work to foster a sense of community in audiences. Bridging, by contrast, is constructive, in that the journalist is actively creating connections between people — in horizontal network relationships — “across cultural, social and economic spaces” (Hess and Waller Citation2016, 114). Lastly, the capacity of journalists to connect individuals in vertical network relationships, linking, is examined.

Relationships between journalists, audiences and elites are further explored by Yanovitzky and Weber (Citation2019, 196). In a policymaking context, they assert that “news media are knowledge brokers due to the crucial knowledge-related functions they now perform for the great majority of policy actors involved in public policymaking processes”. They propose five core journalistic brokerage functions: awareness, accessibility, engagement, linkage, and mobilization. The first three core functions refer to the ability of journalists to acquire, interpret and apply knowledge, while the last two describe the capacity for journalists to create connections between policy actors and create action (Yanovitzky and Weber Citation2019). All five functions, however, shape the flow of knowledge between actors and influence outcomes of the interaction (Weber and Yanovitzky Citation2021, 12).

These five functions are not equally present in every journalistic brokerage relationship. Gesualdo, Weber, and Yanovitzky (Citation2020) show how scientific writers function as brokers who bridge the gap between scientific research and popular press, and that they consciously perform awareness, accessibility and engagement roles, while relegating linkage and mobilization as lower priorities. Pentzold, Fechner, and Zuber (Citation2021) apply brokerage concepts to data journalism in the time of COVID-19 and corroborate Gesualdo, Weber, and Yanovitzky’s (Citation2020) findings on a general aversion to linkage and mobilizing functions, speculating that journalistic norms may be responsible for a general aversion toward interventionism. Excepting Hess and Waller’s work, much research so far focuses on the brokerage functions present in journalistic stories and relationships between the reporters and sources, and less on the relationships that journalists have with audiences. The journalist-source-audience triangle is an important, yet under researched relationship in the context of close-knit rural communities with low populations.

Rural Journalism

Scholars have concluded that there is a “frustrating lack of consensus” on definitions of local journalism (Ali et al. Citation2020, 455). In an attempt to address this problem, Ali et al. (Citation2020) offer a new term, “small market newspaper,” while Hess and Waller (Citation2016) advance the idea of local news’s geo-social context: comprising a connection to a physical space as well as the related social spaces and individual relationships. Gulyas and Baines (Citation2020, 4) offer key defining features of local media as a geo socio-political context; relationship with the community; and position in macro media ecosystems. Further frustrating this terminology is that, while rural journalism is a subcategory of local journalism, local journalism cannot be conflated with rural journalism.

Rural journalism remains little studied. Indeed, “journalism as it is practised outside metropolitan centres is still one of the least researched fields of journalism studies” (Hanusch Citation2015). Agreeing, Örnebring, Kingsepp, and Möller (Citation2020) identify a “metropolitan bias” in journalism research. Speaking in the case of the US, Ali et al. (Citation2020, 453) argue that grouping small-market media into the wider sector of newspapers in general does a disservice to the heterogeneity between major-market newspapers and local media. “Smaller publications face their own challenges and opportunities, and they define success and innovation on their own terms”. They argue for scholarship specifically focusing on smaller publications.

While some analysis of local journalism in general has focused on their vital role in fulfilling critical information needs (e.g., Friedland et al. Citation2012; Napoli et al. Citation2018), rural journalism in specific fulfills other functions in the communities they serve. This includes local boosterism—promoting the interests and reputation of their community (Hess and Waller Citation2016), and described by Mathews (Citation2021) as a “community caretaker” role. Such rural divergences from metropolitan journalistic norms date back nearly a century, with an early rural journalism text explicitly describing divergences from “big city” newspapers, and promoting roles for the “country newspaper” such as increasing community pride, curbing juvenile delinquency, and promoting local interests (Allen Citation1928). This continues today: rural newspapers’ connections with the community still run deep, instilling local pride (Mathews Citation2022).

An important characteristic of rural journalism is a close relationship between audiences and journalists (Perreault et al. Citation2024). “Community newspapers have something that city dailies lack – nearness to people” (Byerly Citation1961, 25). Lauterer (Citation2006, 33) argues that local newspapers

satisfy a basic human craving that most big dailies can’t touch, no matter how large their budgets—and that is the affirmation of the sense of community, a positive and intimate reflection of the sense of place, a stroke for our us-ness, our extended family-ness and our profound and interlocking connectedness.

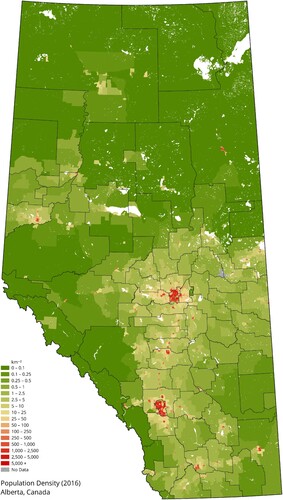

Within Canada, the province of Alberta makes an ideal location to study rural media. Outside of two metropolitan areas, the majority of Alberta is very sparsely populated so there are few “contaminating” media effects between adjacent towns (see ). Communities are typically separated by at least 15 km of farmland or wilderness, and in some cases, separated by hundreds of kilometers. Only a handful of communities still have more than a single local newspaper (Alberta Weekly Newspaper Association Citationn.d.; CBC Citationn.d.). This vastly simplified the media ecosystem makes in-depth analysis more straightforward than in more complicated environments. However, even in these simple ecosystems, complex change is occurring.

Figure 1. 2021 Population density of Alberta. Note: The data for this figure is from “Population and dwelling counts: Canada, provinces and territories, census subdivisions and dissemination areas”, by Statistics Canada (Citation2022). Statistics Canada Open Licence.

Alberta has long been home to independent rural media (publications outside the two Alberta metropolitan areas of Calgary and Edmonton). Most of Alberta’s rural newspapers were started by local entrepreneurs that are owner-operators; managing, editing, and often reporting for the titles they own. Independently owned newspapers, and independently owned groups of two to four newspapers, today account for 47 of 109 titles in the province (Alberta Weekly Newspaper Association Citationn.d.). As is the case in many rural areas, formerly independent Alberta newspapers have increasingly been purchased by chains, with corresponding cutbacks in editorial staffing. Taken to an extreme, this has created in some Alberta areas what Abernathy describes as “ghost newspapers,” publications that are only vestiges of their former selves (Citation2020, 10, 115). Four newspaper chains together now own 62 titles in Alberta: Postmedia (30 titles), Great West Media (14 titles), Black Press (10 titles) and Alta Newspaper Group (8 titles). These chains are diverse in their ownership and scope. Postmedia, for example, owns 130 newspaper titles across Canada including many of the country’s most prominent urban dailies. At the other end of the spectrum, Alta Newspaper Group operates only about a dozen titles, all of them local newspapers. Great West and Black Press own larger numbers of Canadian local newspapers and no urban dailies.

The shift from independent to chain ownership in Alberta mirrors trends observed elsewhere. As early as two decades ago, Franklin (Citation2006, xxi) observed a preponderance of local newspapers “owned by monopoly newspaper groups with head offices, where editorial policy and key decisions are made, located in remote cities or towns”. Such chain ownership of local titles may lead to erosion of news values in terms of “resource allocation decisions that managements take to preserve sustainability of news markets and protect operating profitability” (Cawley Citation2017, 1180). Unlike independent titles, chain-owned newspapers centralize some job functions. For example, a group of newspapers within a chain may share a single publisher, editor, or even reporter (e.g., Mayerthorpe Freelancer Citation2024; Whitecourt Star Citation2024). In some cases, these management positions may be geographically separated from the publication by hundreds of kilometres (e.g., Town and Country Today Citation2024). As well, layout, design, and website maintenance are often centralized in chain publications.

Globally, local media in decline has been well documented and the subject of significant popular attention (Örnebring, Kingsepp, and Möller Citation2020; Takenaga Citation2019). However, studies of local newspapers (and especially rural newspapers) are rare in Canada and represent a significant gap in the research literature. Canadian local newspapers “lie at an unstudied quadrant: they are distinct from better-studied American community newspapers, and they are distinct from better-studied Canadian daily newspapers” (Nagel Citation2015, 331). Notwithstanding this general paucity, a 2017 study of Canadian newspapers (including urban dailies) found significant contraction in the sector as a whole. However, this study was not specific to rural media (Public Policy Forum Citation2017). In 2019, a survey of Canadian local media (one of the only contemporary ones), found that local newsrooms were shrinking, and that job insecurity was rampant among remaining staff (Lindgren et al. Citation2019). Despite its significance to rural news scholarship in Canada, this survey was not comprehensive in any single Canadian region and relied on anonymous responses. Lindgren continues to track the decline in local Canadian media through the Local News Map (Lindgren, Corbett, and Hodson Citation2020), documenting the loss of 269 local news titles in Canada between 2008 and 2019.

As the local news sector continues to contract, newspapers close and towns are left without newspapers dedicated to their community. Instead of a newspaper for each town, regional newspapers serve groups of rural communities. Such a regional title may cover the entire news of a county or may span several communities in more than one county, sometimes covering hundreds or thousands of square kilometres (The Local News Research Project Citation2024). For example, the East Central Alberta Review covers news in 12 towns, with populations ranging from 2234 (Hanna) to 154 (Youngstown) (East Central Alberta Review Citation2024). Several of these communities once had their own newspapers but these became unviable as individual publications.

Intrinsic to local journalism, especially in rural communities, are relationships between the local reporter and their audience and sources. It is clear that reporter staffing is quickly changing in local newspapers in Canada (Lindgren et al. Citation2019). To understand the changing position of rural journalists we develop and advance Gould and Fernandez’s (Citation1989) general knowledge broker categories in the context of rural journalism. We ask: How do journalists function as knowledge brokers in rural communities in order to build and maintain relationships with sources and audiences?

Methodology

This paper focuses on newspapers (both print and online): they are the dominant form of local news media production (Mahone et al. Citation2019, 2). Moreover, newspapers are “keystone” local media—the main providers of local news information in many communities, and enablers of other forms of news media (Nielsen Citation2015, 54). Further, local rural news radio and television stations are quite rare in rural Alberta (mediainalberta.ca Citation2023a, Citation2023b). To begin, all newspaper titles in Alberta were identified through listings on the websites of the Alberta Weekly Newspaper Association (Citationn.d.) and National NewsMedia Council (Citation2022), online searches, and snowball sampling of other media outlets. The criteria for inclusion were a journalistic publication that relied on the use of human source material (interviews, etc.) in textual and photographic coverage, and that employed editorial staff (instead of relying solely on volunteer contributions). In keeping with a focus on journalism, the study excluded non-journalistic newsletters, and publications from groups other than media organizations (for example, a county newsletter produced by the county government itself). To maintain a focus on rural publications, newspapers in two large Alberta cities with populations of more than 1,000,000 were excluded, as well as local newspapers from the surrounding commuter towns. This resulted in a comprehensive list of newspapers that reflects the entire population of rural newspapers in the province of Alberta as of 2022. In total, 73 rural newspapers were included.

Through contact details on websites, print editions and social media, the publisher, editor, or reporters at each newspaper were approached. Because we wanted to include as many outlets as possible and visiting them in person was impossible given the remoteness of the area, we decided to send them a questionnaire in August 2022. We offered respondents the opportunity to answer the questions either by email or by telephone. In all, 50 respondents representing 61 newspapers participated, generating an 83.6% response rate, much higher than average response rates for organizational studies research (Baruch and Holtom Citation2008). Of the responses, 10 were by telephone call and 40 were by email. For those that participated by telephone, verbal interviewing allowed the researcher to probe the functioning of the newspaper, including the current operating practices. Those answering by email often engaged in longer interview-like exchanges, because follow-up email questions were posed to prompt additional details or to clarify information when data or answers provided in email responses were unclear. Our questionnaire thus functioned as a semi-structured interview guide that allowed for obtaining in-depth information about the operations of the newspapers.

The questionnaire first focused on the levels of editorial staffing to get an insight in the number of journalists working at each paper. We then inquired after the editor and publisher roles (often one and the same at small newspapers, despite the desirability of separating these roles in larger news organizations). Consecutively, we asked questions to unravel complex multi-role positions and responsibilities common at very small newspapers. It is important to note that we did not ask about brokerage specifically in the questionnaire, and the telephone and email interviews. This theme came up inductively when we analyzed the data. Our research design was reviewed and approved by the SAIT research ethics board in Calgary, Canada (certificate 100117).

Because a comprehensive dataset of staffing at all rural newspapers in Alberta was desired, 12 nonrespondent rural newspapers were examined to determine the total number of news workers at each publication. As much public data as possible was gathered, including staff listings on websites and social media, mastheads in print editions, and bylines on online and digital stories. To ensure the rigor of the resulting data, it was tested for accuracy by employing the same triangulation techniques on 12 randomly selected respondent newspapers. In all, a 93% accuracy level was achieved on the 12 respondent papers, indicating that the resulting triangulation data for the nonrespondent papers was accurate.

Analysis was conducted on the number of editorial staff at each title. Staff dedicated solely to layout and design, advertising sales, production, distribution, and administration were not included. Full time, part time, and freelance editorial contributors were aggregated and averaged across titles and by chain ownership. In the rural Alberta context, most freelance contributors are generally of the “country correspondent” variety described by Byerly (Citation1961, 113) and work exclusively for a single newspaper rather than full-time freelancers, common in metropolitan contexts, that write content for several publications. This quantitative data was supplemented by qualitative comments by individual news workers at participant publications.

Thematic analysis was conducted on the telephone interviews and the email exchanges. After a subjective familiarization with the data, responses were coded according to themes. As such brokerage was identified as an issue. Bearing in mind the use of the concept, survey responses were specifically analyzed for descriptions of relationships between sources, journalists, and audiences. This was an iterative process: as new themes were identified, previously coded responses were reanalyzed for the new themes. Once the survey data were analyzed, the responses informed the brokerage framework outlined in this paper.

Reporters as Brokers

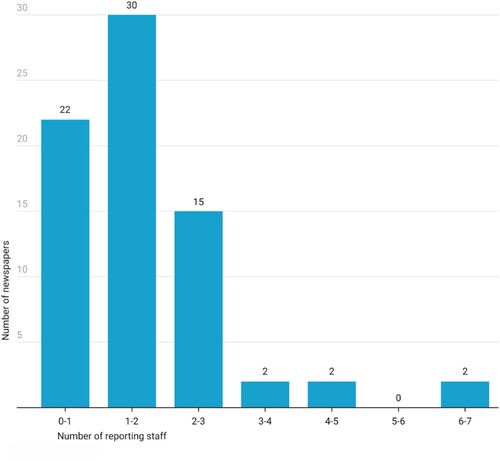

In Alberta, there are 91 full-time news workers employed at 73 rural newspapers. 21 part-time workers are employed, and there are 43 regular freelance contributors. Rural newspapers have a wide variety of arrangements and workloads for part-time and freelance contributors. In some cases, the workload varies with the season, or with events taking place in the community. To generate an estimate at overall staffing levels, a weighting system was used to produce full-time-equivalents to part-time workers and freelance staffing. Part-time workers were weighted as equivalent to one-half of a full-time position, and freelance contributors were weighted as equivalent to a 10% full-time position. The overall staffing levels and full-time equivalent positions are presented in , below, and a frequency chart is provided as .

Table 1. Total and average numbers by position type at 73 rural Alberta newspapers.

These staffing numbers are important in the application of brokerage to rural journalism. They demonstrate that rural journalism is a lonely endeavor: In rural Alberta, most newspapers consist of teams of two or fewer editorial staff working largely independently to provide coverage of a community. Rural publications don’t fit into newsroom models frequently employed by journalism scholars of better-staffed newspapers. Reporters don’t operate with the close supervision common at larger organizations, so factors such as newsroom norms and editorial oversight of individual reporters are not as applicable. Also, visualizing rural newspapers as organizations creates a level of complexity that is no longer appropriate to most outlets. In many cases, the reporter now is the organization.

Types of Brokerage Relationships

In our brokerage analysis of rural journalists, their sources, and audiences, we consider three characteristics of Alberta’s rural newspapers that the interviews revealed. First, that reporters either work independently, or in a team of two or fewer full-time reporters. Second, that reporters have developed relationships with local community members during their reporting work and in daily life. Third, that they have little organizational oversight of their editorial work, considering that most either work for an independent local paper, or for a chain with distant managers that are not resident in the community that is being covered. Freed from the oversight of an editor or manager, the independent news worker can use their deep community relationships to gather information from one party, manipulate and package it to increase value, and deliver it to another member of the community: the core function of a broker.

Recognizing this independence and the implications it has for journalist-source-audience relationships, this paper now returns to the Gould and Fernandez brokerage framework to analyze brokerage relationships in rural Alberta journalism: coordinating, itinerant, representative, liaison, and gatekeeping. We then advance the framework to include a novel brokerage type: relay.

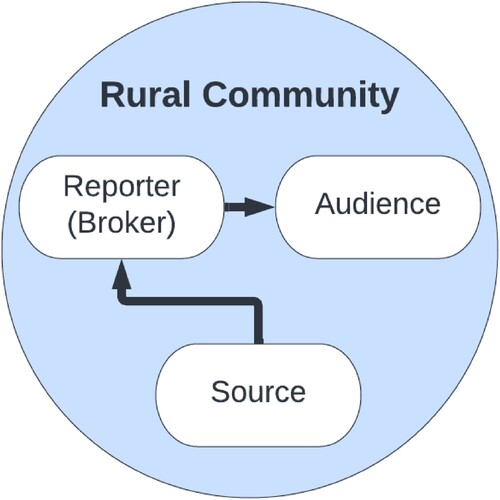

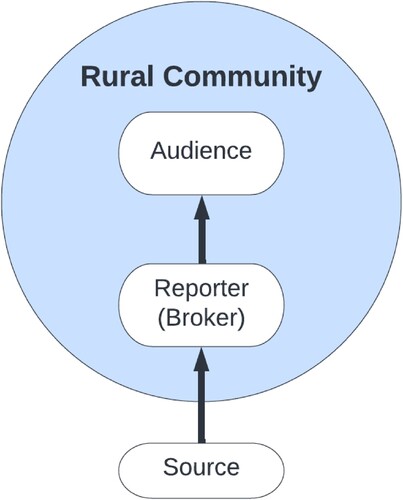

Coordinating Brokerage. In a coordinating brokerage, the broker is a member of the same community as the audience and source (). Generally, newspapers typified by this relationship are created when a community member identifies the need for a newspaper and acts upon it. Coordinating brokerages were the classic model used in rural reporting in Alberta for almost a century. For example, in the town of Three Hills Alberta (population 3212) the Three Hills Capital was founded independently in 1916. It is currently owned by a local family that purchased the newspaper in 1976. In an uninterrupted hundred-year history, it has printed local news by employing local reporters. Now reduced to a single reporter, the Capital is on the brink of financial unviability as advertising revenues have declined sharply. “There’s just not enough news here” despairs the resident editor, exemplifying an almost exclusive focus of telling locally sourced stories to a (declining) local audience. Because the reporter-broker lives in the community of Three Hills, reporting local news from local sources to local audiences, this is a typical coordinating brokerage.

Not all coordinating brokerages in rural Alberta are declining. For example, a failing newspaper in Cardston (population 3585) was recently purchased by a new publisher who lives within the community. He discontinued the digital version of the paper and reverted to print publication only. “The previous owner went online. After I bought the paper, I reversed course” says the new owner. Because of the increased community engagement and improved ad revenue of the print edition, the paper is now profitable once more.

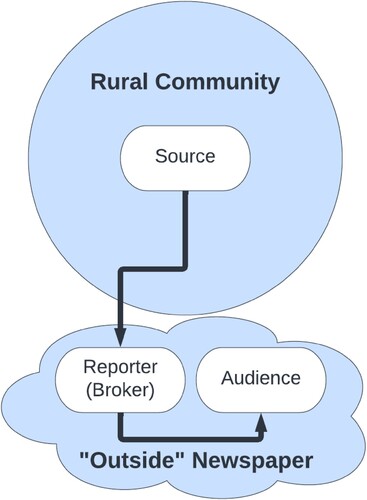

Itinerant Brokerage. In an itinerant brokerage, the broker is in one group, while the story sources and audiences belong to another group (). This type of relationship is typified when a community no longer has a resident reporter, with the coverage being performed by a reporter stationed in an external community. The reporter-broker may only visit the community in question occasionally (or on a schedule). The Vauxhall Advance, an Alta Newspaper Group title, is, for example, staffed by two reporters, who collectively dedicate 2.5 days per week to the town, with the balance of their hours dedicated to other titles in the ownership group. In the case of Vauxhall (population 1222), both shared reporters live in other towns but the community is provided with regular journalists. Due to newspaper chain budgets not allowing for a full-time reporter in each town, “staff routinely work in multiple titles” says the group publisher.

Longer-duration itinerant brokerages were discovered in a different remote community served by a chain-owned newspaper. The only remaining reporter relocated to another province but continues to attempt coverage from a now-distant location. Working with sources over the telephone and internet, he tells stories using community sources, and the stories are printed in a newspaper for consumption by local audiences.Footnote2 This type of work arrangement is increasingly demanded by applicants for reporting jobs in rural areas. Three different editors in this study independently reported that job applicants recently made requests for remote-coverage arrangements because they wanted to continue living in a major urban area while covering rural news remotely.

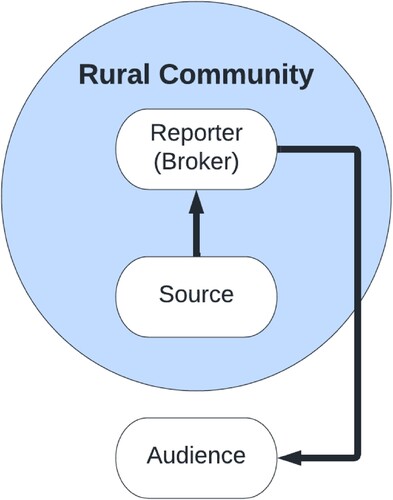

Representative Brokerage. Representative brokerage is when reporters and their sources are in the same community, but audiences are in different ones (). This often occurs when a reporter employed by a regional paper is stationed in a single town. The stories they write are read by a largely non-group audience. These types of arrangements are increasingly common as regional publications take the place of community newspapers. The news for several towns is aggregated in a single publication, or a smaller town’s news is included as a section in a larger neighboring community’s newspaper.

For example, the Mountain View Today now covers the towns of Carstairs (population 4077), Didsbury (population 5268), Olds (population 9184), Innisfail (population 7847) and Sundre (2729). As recently as 20 years ago, each of these towns had their own newspaper (and in the case of Olds, had two competing newspapers). Mountain View Today still employs resident reporters to cover news in Olds, Innisfail and Sundre, but a regional reporter covers news in Carstairs and Didsbury. In the case of Sundre, the resident reporter-broker works with local Sundre sources to create stories which are subsequently printed in the regional title and read by members of all five communities. In the wake of budget cutbacks, making strategic decisions about which reporters represent which communities can be difficult. “During the pandemic, I let go of my Didsbury reporter—who used to cover Carstairs too; a second reporter and photographer based in Olds, and a second reporter in Innisfail” says the publisher.

Representative brokerages are also increasingly common as news reporters from other towns (sometimes unknowingly) have their work published in so-called “ghost newspapers”—titles that continue to be printed or published online but are filled with no local reporting (Abernathy Citation2020). Usually owned by chains, the non-local content comes from reporters further afield, and the titles exist mostly to sell local ads, not to provide any meaningful or comprehensive community content. Sources and reporters are resident in a nearby or distant town, and the content created is usually intended for a separate news publication local to that town. These stories are subsequently published in a “ghost” newspaper and distributed to local community residents. Several ghost (or nearly-ghost) newspapers were identified in in Alberta during this study.

Liaison Brokerage. In this most complex brokerage relationship in Gould and Fernandez’s typology, brokers, readers, and sources each belong to different communities (). This occurs where the reporter is not a local community member, yet “takes” a story from local sources that is published in external newspapers. Liaison brokerage can happen when an important story “breaks” in a rural community and outside reporters “parachute” into the community to tell the story. This happened, for example, in the remote town of Slave Lake (population 6651) in 2011 when a wildfire burned almost every building in the city. The event attracted national interest, and reporters from all over Canada turned their attention to Slave Lake to report the story to national audiences. The sources were from Slave Lake, the reporters from communities elsewhere in Canada, and the audience was national (e.g., Ibrahim, Snyder, and Cummins Citation2011; Wingrove Citation2011). Generally, liaison brokerages in rural journalism are born out of necessity or opportunity, and often are singular to a particular story or event.

Gatekeeping Brokerage. Gatekeeping brokerages occur when the reporter-broker and the reader are in one local group, with the source in an external group (). Like liaison brokerages, a gatekeeping brokerage most often occurs in singular stories, and not as long-term brokerage relationships. They occur when out-of-community sources are involved in a single piece (or recurring) type of coverage, for example when rural reporters work with sources that are not community members. This might happen when news is reported on a federal government initiative that affects a small town, or a local member of parliament is interviewed for a story. For example, a federal member of parliament was interviewed by a reporter for the Drumheller Mail about his opinions of the federal budget, but he is not resident in the town of Drumheller (population 7982) and represents many towns in the area (Kolafa Citation2024).

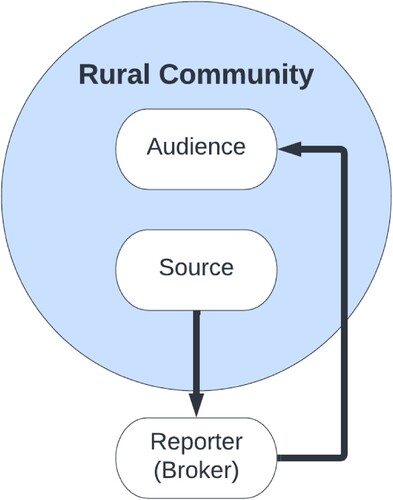

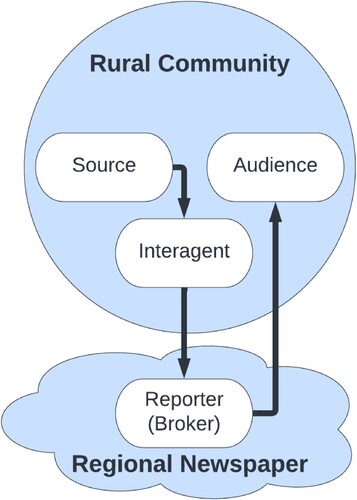

A Novel Category of Brokerage: Relay. Based on our analysis we conceptualize an additional brokerage relationship, relay brokerage, which complements Gould and Fernandez’s five types (Citation1989). It is typified by the addition of a fourth actor, next to journalists, sources, and audiences, termed an interagent. These perform an additional step in the source-audience group: gathering information from in-group sources before sending it to an external broker for inclusion, manipulation, and subsequent broadcast back to the in-group audience ().

Relay brokerages can occur when a news desert community is served by a regional newspaper. A local contributor (the interagent) gathers information from a local source (an in-group source). This information is sent to a remote editor (the broker) for inclusion in a regional publication, then distributed back to the source community audience (in the same group as the source and interagent). Only the broker is outside the group. For example, Bassano (population 1206), formerly had a newspaper, the Bassano Times, that closed. Coverage of the town council and other local affairs is now performed by a Bassano resident and printed in The Bulletin, a newspaper in the nearby town of Brooks (population 14,451). The Brooks Bulletin is subsequently distributed in Bassano. There are four actors in this relationship: the source in Bassano, a contributor (the interagent) in Bassano, a news editor (broker) in Brooks, and an audience back in Bassano.

The local contributor technique is recently employed to provide coverage to small towns where a paper has closed, but it is not a novel phenomenon (e.g., Allen Citation1928, 116). The technique of local contributors has deep roots in rural journalism in Canada: “Rural correspondents have been a fixture of this newspaper and other rural papers since pretty well day one” says the editor of the Brooks Bulletin. There are many similar cases of correspondents in rural Canadian newspaper history: evidence that relay brokerage predates the current downturn in local journalism (e.g., Whitehorse Star Citation1995).

The relay brokerage model may become more yet prevalent in contemporary rural journalism as titles regionalize, and as reporting budgets are squeezed to the point where newspapers are no longer able to afford even a paid freelance reporter position. Community members sometimes have a desire for local news coverage, but lack the training, knowledge, time, and resources to start a news outlet. For example, in La Crete, a settlement of 3000 people and without a local newspaper, the closest newspaper is 45 min away. Residents had approached the regional newspaper, at they told in a La Crete community Facebook group, offering to cover La Crete news on a volunteer basis. The offers have not yet been acted on by the regional newspaper, and some residents are resentful about that. Towns like La Crete may be prime locations to discover other relay brokerage relationships.

Discussion

Literature on brokerage shows that these offer stable structures to local communities, but also change and evolve over time. In many rural communities with degraded or closed local newspapers and a reduced amount of brokered information, new brokers have emerged to fill this information void. Sometimes these are “interlopers” that in some cases push the boundaries of what is considered to be journalism (Eldridge Citation2017). These start-up titles can be visualized as new brokers, filling the gaps left by the reduced efficacy of traditional brokers. However, while these new brokers may offer capabilities or approaches that don’t exactly duplicate the functions of prexisting ones, brokerage relationships may remain the same. We argue that this provides stability to news ecosystems.

An example of this is the town of Grande Cache. With a population of 3276, this community is among the most remote and sparsely populated regions in Alberta, and until recently the Belgium-sized census division of 33,104 square kilometres was a complete news desert with no local journalism. In 2021, a local mental health worker with a journalistic background received a grant from the provincial mental health association to start a newspaper. This editor felt that the isolation wrought by COVID-19 restrictions and polarization in the community over vaccines could be mended by sharing uplifting community news. The Grande Cache Community Mountain Voice therefore eschews any divisive subject (such as local controversy and scandal, and COVID-19 restrictions) as well as any “negative” stories (such as fires and automobile accidents), in direct contrast with decades-old established rural journalistic practice (cf. Allen Citation1928; Byerly Citation1961).

With a focus on telling “good news” stories about the community to community members, the role of the journalist is a coordinating broker. In the case of the Mountain Voice, the concept of brokerage allows us to understand important context to the unusual storytelling practices of the newspaper: it was founded by community members to share news within the community with a unifying intention. With audience, broker and source all members of the community, its unconventional approach to journalistic norms (telling good news only) is better understood. The journalist/broker has a specific role in the community, and she shapes the information she gathers to serve the “good news” needs of a divided community.

However, while journalistic brokerage provides structural stability to local communities, brokerages themselves evolve. Reflecting the murky world of human relationships (local and distant, transient and long-term, official and ad-hoc), relationships between sources, audiences and rural journalists are fluid, transgressing the boundaries of the six brokerage types we outlined (Yanovitzky and Weber Citation2019, 196). Change may even happen by the hour, instead of the year or decade. In a rural community, the reporter may report on a city council meeting in the morning, and then have her car fixed by the mayor in a repair shop in the afternoon, as our respondents vividly told. The reporter may attend a press conference of a local politician and then the same day, attend a library board meeting or volunteer as a library worker in the evening. The reporter might edit and publish the column of a freelance contributor from a neighboring town and then visit a different town herself to cover a story. Much more so than in urban newspapers, rural journalists are active community members as well as reporters (Perreault et al. Citation2023). Performance of the community member role may collide with traditional journalistic norms. For example, a small-town reporter may be called on to perform roles repugnant to major-market journalist, like “boosterism” of local enterprises over competing businesses in adjoining towns (Guth Citation2015; Hess and Waller Citation2016). Local reporting work itself (no matter whether it’s rural or urban) demands flexibility and creativity—and this is amplified in a rural setting.

This daily flexibility in journalistic brokerage models mean that unlike Wolf’s classic description of brokers as “Janus-like, they face in two directions at once” (Wolf Citation1956, 1076), a rural reporter-broker is more than that. Perhaps instead of Janus, a local news reporter is more like the Greek god Proteus: a shapeshifter that assumes forms convenient to a situation. In terms of brokerage classifications for local reporting, the type of brokerage may vary from story to story or vary from day to day. In fact, flexibility has long been part of the journalist role. Brokerage classifications should be used as a lens to understand the work and roles of local reporters, not to definitively classify a particular reporter or their work.

Conclusion

The connection of reporters with sources and audiences in their communities is a hallmark of rural journalism (Mathews Citation2022; Perreault et al. Citation2024). The concept of brokerage provides a framework to understand these shifting relationships, moving further research on rural audience relationships and journalist-source interactions from descriptive to conceptual. In addition, it offers a pathway to examine local information ecosystems worldwide as the influence of newspapers in rural communities continues to decline. However, the increasing diversity of role manifestations of journalists poses ontological questions about the practice of journalism itself. In discovering specific brokerage relationships in contemporary Albertan rural journalism, we must ask whether such relationships have always existed, or whether they are manifestations of the changing face of local journalism. Further, as entrepreneurial approaches change the medium and practice of news production, are newer informational brokerages journalistic? Carlson and Lewis advocate for scholarly precision in defining journalistic boundaries (Citation2019)—and this should be extended to precision in assessment of brokerage categorizations.

Brokerage may provide a useful path for scholars to understand some of the challenges in identifying what, exactly, journalism is. While Carlson and Lewis propose a framework of participants, practices and propositions in their boundary work (Citation2019), their model does not analyze complex relationships between the participants, or what the practices yield in terms of social discourse. Brokerage provides a way of looking at journalistic work (rural and potentially urban) in terms of the relationship of participants—including journalists, sources, and audiences—to the information being created, gathered, and shared. Journalism is more than a participant, a practice, or a preposition: it is the manifestation of a complex web of shared understandings and complicated informational and inter-actor relationships that yields a recognizable product (Benson and Neveu Citation2005). Brokerage provides a new starting point for understanding such relationships.

These six brokerage roles may be used to consider the dynamics between sources, audiences, and journalists. They are, however, reliant on understanding where the bounds of the community are. For the classifications to be effective, an actor must be clearly defined as “in” or “out” of a community. In a rural context, there is often little uncertainty about who is “in” or “out” of the community, unlike metropolitan areas. Rural residents either live within the coverage area of the newspaper, or they don’t. In nearly every case, there are no competing publications. Application of brokerage classifications to more densely populated areas will require clear definitions of the boundaries of “community.” For example, if a resident of a major city served by two daily newspapers only reads a competing paper, are they a member of the first newspaper’s community, or an outsider?

One dimension not considered in our research is the intensity of the relationships within a brokerage model, something considered in depth by earlier work on non-journalistic brokerages (e.g., Gould and Fernandez Citation1989). Our study has shown that in rural Alberta staffing has declined to levels where some titles don’t even employ a single full-time reporter and many titles have been aggregated to regional publications, sometimes not employing even a part-time reporter to cover news in each community they “serve.” With the increasing number of communities without a resident reporter, news production relies more on itinerant and relay brokerages which carry with them weaker ties to audiences and sources. Examination of the intensity of the relationships present in various brokerage types in communities may be a productive line of research in understanding the role of ghost newspapers and regional amalgamation in local information ecosystems.

Future research might further tease out brokerage relationships. The application of brokerage emerged inductively from our questionnaire, which was conducted by telephone and email due to the vast distances and sparse populations in rural Alberta. Further, this study examined journalists only. A more thorough examination of information ecosystems within small communities, including actors beyond journalists, such as sources and audiences, will further elucidate the journalistic brokerage relationships present in rural areas. An “on the ground” ethnographic research methodology could elucidate various ways brokerage relationships interact. As well, such an approach would facilitate examination of non-journalistic information brokerages present in rural communities, including public librarians, social media group moderators, and public relations professionals. Another fruitful avenue of advance is to examine how funders of journalism—be they advertisers, subscribers or philanthropists, affect brokerage relationships.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The newspaper owner that said this made their participation contingent on their anonymity, for business reasons.

2 The newspaper worker that said this made their participation contingent on their anonymity, because of concerns for their employment.

References

- Abernathy, P. M. 2020. News Deserts and Ghost Newspapers: Will Local News Survive? University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. https://www.usnewsdeserts.com/reports/news-deserts-and-ghost-newspapers-will-local-news-survive/.

- Alberta Weekly Newspaper Association. n.d. AWNA Member Listing. Alberta Weekly Newspaper Association. Retrieved October 28, 2022, from http://www.awna.com/awna-member-listing.

- Ali, C., D. Radcliffe, T. R. Schmidt, and R. Donald. 2020. “Searching for Sheboygans: On the Future of Small Market Newspapers.” Journalism 21 (4): 453–471. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884917749667.

- Allen, C. L. 1928. Country Journalism. T. Nelson and Sons. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/006620373.

- Bagshaw, T. 2019. “What Happens When our Local News Disappears? How UK Local Newspapers Are Closing and Coverage of Court Proceedings is not Happening.” Index on Censorship 48 (1): 29–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306422019842090.

- Baruch, Y., and B. C. Holtom. 2008. “Survey Response Rate Levels and Trends in Organizational Research.” Human Relations 61 (8): 1139–1160. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726708094863.

- Benson, R., and E. Neveu, eds. 2005. Bourdieu and the Journalistic Field. Malden, MA: Polity.

- Burt, R. S. 2005. Brokerage and Closure: An Introduction to Social Capital. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Byerly, K. R. 1961. Community Journalism. Philadelphia, PA: Chilton Co., Book Division.

- Carlson, M., and S. Lewis. 2019. “Boundary Work.” In The Handbook of Journalism Studies, edited by K. Wahl-Jorgensen and T. Hanitzsch. 2nd ed. 123–135. New York: Routledge.

- Cawley, A. 2017. “Johnston Press and the Crisis in Ireland’s Local Newspaper Industry, 2005–2014.” Journalism 18 (9): 1163–1183. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884916648092.

- CBC. n.d. Local News Directory. The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved April 13, 2024. https://cbc.radio-canada.ca/en/impact-and-accountability/local-news-directory.

- East Central Alberta Review. 2024. Distribution & Coverage Area. East Central Alberta Review. https://ecareview.com/distribution/.

- Eldridge, S. A. 2017. Online Journalism from the Periphery: Interloper Media and the Journalistic Field. 1st ed. Abingdon: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315671413.

- Franklin, B., ed. 2006. Local Journalism and Local Media: Making the Local News. London: Routledge.

- Friedland, L., P. M. Napoli, K. Ognyanova, C. Weil, and E. J. I. Wilson. 2012. Review of the Literature Regarding Critical Information Needs of the American Public. Federal Communications Commission. https://www.fcc.gov/news-events/blog/2012/07/25/review-literature-regarding-critical-information-needs-american-public.

- Geertz, C. 1960. “The Javanese Kijaji: The Changing Role of a Cultural Broker.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 2 (2): 228–249. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0010417500000670

- Gesualdo, N., M. S. Weber, and I. Yanovitzky. 2020. “Journalists as Knowledge Brokers.” Journalism Studies 21 (1): 127–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2019.1632734.

- Gould, R. V., and R. M. Fernandez. 1989. “Structures of Mediation: A Formal Approach to Brokerage in Transaction Networks.” Sociological Methodology 19:89. https://doi.org/10.2307/270949.

- Gulyas, A., and D. Baines. 2020. “Demarcating the Field of Local Media and Journalism.” In The Routledge Companion to Local Media and Journalism, edited by A. Gulyas and D. Baines, 1–21. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Guth, D. 2015. “Amber Waves of Change: Rural Community Journalism in Areas of Declining Population.” Journal of Applied Journalism & Media Studies 4 (2): 259–275. https://doi.org/10.1386/ajms.4.2.259_1.

- Hanusch, F. 2015. “A Different Breed Altogether? Distinctions Between Local and Metropolitan Journalism Cultures.” Journalism Studies 16 (6): 816–833. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2014.950880.

- Hess, K. 2013. “ Tertius Tactics: “Mediated Social Capital” as a Resource of Power for Traditional Commercial News Media.” Communication Theory 23 (2): 112–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/comt.12005.

- Hess, K. 2020. “New Approach Needed to Save Rural and Regional News Providers in Australia.” ADI Policy Briefing Papers 1 (4): 10.

- Hess, K., and L. Waller. 2016. Local Journalism in a Digital World. London: Macmillan International Higher Education.

- Hobbis, S. K., and G. Hobbis. 2020. “Non-/human Infrastructures and Digital Gifts: The Cables, Waves and Brokers of Solomon Islands Internet.” Ethnos 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/00141844.2020.1828969.

- Ibrahim, M., J. Snyder, and J. Cummins. 2011. “Fires Invade Slave Lake; Town Hall, Businesses Burn as Residents Seek Safety.” Edmonton Journal A.1.

- Kolafa, P. 2024. “MP Damien Kurek Reacts to Federal Budget.” Drumheller Mail, April 29, 2024. https://www.drumhellermail.com/news/36324-mp-damien-kurek-reacts-to-federal-budget.

- Latour, B. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lauterer, J. 2006. Community Journalism: Relentlessly Local. 3rd ed. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Lindgren, A., J. Corbett, and J. Hodson. 2020. “Mapping Change in Canada’s Local News Landscape: An Investigation of Research Impact on Public Policy.” Digital Journalism 8 (6): 758–779. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2020.1724516.

- Lindgren, A., B. Jolly, C. Sabatini, and C. Wong. 2019. Good News, Bad News: A Snapshot of Conditions at Small-Market Newspapers in Canada. https://portal.journalism.ryerson.ca/goodnewsbadnews/wp-content/uploads/sites/17/2019/04/GoodNewsBadNews.pdf.

- Lindquist, J. 2015. “Of Figures and Types: Brokering Knowledge and Migration in Indonesia and Beyond.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 21 (S1): 162–177. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9655.12172.

- The Local News Research Project. 2024. Local News Map Data. The Local News Research Project. https://localnewsresearchproject.ca/category/local-news-map-data/.

- Mahone, J., Q. Wang, P. M. Napoli, M. Weber, and K. Mccollough. 2019. Who’s Producing Local Journalism? Assessing Journalistic Output Across Different Outlet Types. DeWitt Wallace Center for Media & Democracy Sanford School of Public Policy. http://dewitt.sanford.duke.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2019/08/Whos-Producing-Local-Journalism_FINAL.pdf.

- Marsden, P. V. 1982. “Brokerage Behavior in Restricted Exchange Networks.” In Social Structure and Network Analysis, edited by P. V. Marsden and N. Lin, 201–218. Beverly Hills: Sage.

- Mathews, N. 2021. “The Community Caretaker Role: How Weekly Newspapers Shielded Their Communities While Covering the Mississippi ICE Raids.” Journalism Studies 22 (5): 670–687. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2021.1897477.

- Mathews, N. 2022. “Life in a News Desert: The Perceived Impact of a Newspaper Closure on Community Members.” Journalism 23 (6): 1250–1265. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884920957885.

- Mayerthorpe Freelancer. 2024. Contact the Mayerthorpe Freelancer. Mayerthorpe Freelancer. https://www.mayerthorpefreelancer.com/our-newsroom/contact-the-mayerthorpe-freelancer.

- mediainalberta.ca. 2023a. Radio Stations in Alberta. https://mediainalberta.ca/radio-stations.html.

- mediainalberta.ca. 2023b. Television Stations in Alberta. https://mediainalberta.ca/television-stations.html.

- Nagel, T. W. S. 2015. “Online News at Canadian Community Newspapers: A Snapshot of Current Practice and Recommendations for Change.” Journal of Applied Journalism & Media Studies 4 (2): 329–362. https://doi.org/10.1386/ajms.4.2.329_1.

- Napoli, P. M., M. Weber, K. Mccollough, and Q. Wang. 2018. News Deserts, Journalism Divides, and the Determinants of the Robustness of Local News. Durham: DeWitt Wallace Center for Media & Democracy.

- National NewsMedia Council. 2022. List of Members. National NewsMedia Council. https://www.mediacouncil.ca/list-of-members/.

- Nielsen, R. K. 2015. “Local Newspapers as Keystone Media: The Increased Importance of Diminished Newspapers for Local Political Information Environments.” In Local Journalism: The Decline of Newspapers and the Rise of Digital Media, edited by R. K. Nielsen, 51–72. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Örnebring, H., E. Kingsepp, and C. Möller. 2020. “Journalism in Small Towns: A Special Issue of Journalism: Theory, Practice, Criticism.” Journalism 21 (4): 447–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884919886442.

- Pentzold, C., D. J. Fechner, and C. Zuber. 2021. “Flatten the Curve”: Data-driven Projections and the Journalistic Brokering of Knowledge During the COVID-19 Crisis.” Digital Journalism 9 (9): 1367–1390. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1950018.

- Perreault, M. F., J. Fargen Walsh, L. Lincoln, G. Perreault, and R. Moon. 2023. ““Everything Else is Public Relations” How Rural Journalists Draw the Boundary Between Journalism and Public Relations in Rural Communities.” Mass Communication and Society 27 (2): 332–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2023.2243920.

- Perreault, M. F., J. Walsh, G. Perreault, L. Lincoln, and R. Moon. 2024. “What is Rural Journalism? Occupational Precarity and Social Cohesion in US Rural Journalism Epistemology.” Journalism Studies 25 (4): 421–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2024.2314206.

- Public Policy Forum. 2017. The Shattered Mirror: News, Democracy and Trust in the Digital Age. https://shatteredmirror.ca/.

- Smith, C. C. 2019. “Identity(ies) Explored: How Journalists’ Self-Conceptions Influence Small-Town News.” Journalism Practice 13 (5): 524–536. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2018.1544849.

- Statistics Canada. 2022. Table 98-10-0015-01 Population and Dwelling Counts: Canada, Provinces and Territories, Census Subdivisions and Dissemination Areas, February 9, 2022. https://doi.org/10.25318/9810001501-eng.

- Stovel, K., and L. Shaw. 2012. “Brokerage.” Annual Review of Sociology 38 (1): 139–158. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-081309-150054.

- Szasz, M. C. 2001. Between Indian and White Worlds: The Cultural Broker. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Takenaga, L. 2019. “More than 1 in 5 U.S. Papers Has Closed. This Is the Result.” The New York Times, December 21, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/21/reader-center/local-news-deserts.html.

- Town and Country Today. 2024. Contact Us. Town and Country Today. https://www.townandcountrytoday.com/other/contact-us.

- Weber, Matthew S., and I. Yanovitzky. 2021. “Knowledge Brokers, Networks, and the Policymaking Process.” In Networks, Knowledge Brokers, and the Public Policymaking Process, edited by M. S. Weber and I. Yanovitzky, 1–26. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-78755-4.

- Whitecourt Star. 2024. Contact the Whitecourt Star. Whitecourt Star. https://www.whitecourtstar.com/our-newsroom/contact-the-whitecourt-star.

- Whitehorse Star. 1995. “Whitehorse Daily Star: Star columnist Edith Josie named to Order of Canada.” Whitehorse Star, June 29, 1995. https://www.whitehorsestar.com/History/star-columnist-edith-josie-named-to-order-of-canada.

- Wingrove, J. 2011. “Forest Fires Engulf Alberta Town.” The Globe and Mail, A.3, May 16, 2011.

- Wolf, E. R. 1956. “Aspects of Group Relations in a Complex Society: Mexico.” American Anthropologist 58 (6): 1065–1078. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1956.58.6.02a00070.

- Yanovitzky, I., and M. S. Weber. 2019. “News Media as Knowledge Brokers in Public Policymaking Processes.” Communication Theory 29 (2): 191–212. https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qty023.