Abstract

The paper assesses how housing commodification in China has been used to cope with the impact of financial crises and open up new opportunities to boost economic growth. In particular, in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, the injection of capital has led to a new housing market cycle. We explain the major housing market cycles after 1978 and suggest an underlying linkage with macroeconomic measures aimed at making housing a more ‘liquid’ asset and richer households increasingly using second homes as an investment strategy. Further, the Chinese form of development regime is examined, revealing the role of local government in promoting housing markets, on the one hand, and the concern of central government with property bubbles and financial risks – leading to the adaptation of a more regulated approach to restrict housing sales – on the other. We argue that housing market cycles should be understood by seeing how property development is at the centre of urban development in China.

Introduction

Since China embarked on the road towards the development of a housing market, house prices have experienced five major cycles of fluctuations. Each cycle has specific historical conditions, but there is a general pattern of driving forces, which is related to the commodification of housing, placing property development at the centre of consumption and development, and the formulation of promotional or restrictive policies to achieve objectives outside the housing sphere. In the 2000s, China has sustained an unprecedented housing boom, despite a series of tightening policies from the central government.

Although there is extensive research on China's housing reform and system (e.g. Li & Yi, Citation2007; Wang & Murie, Citation1999; Zhou & Logan, Citation1996), tenure changes (Huang & Clark, Citation2002; Huang & Yi, Citation2010; Logan, Fang, & Zhang, Citation2009), the development of the mortgage market (Li, Citation2010; Wang, Citation2001), housing affordability (Chen, Hao, & Stephens, Citation2010; Wang, Citation2001), and residential inequalities (Logan et al., Citation2009), studies of house prices focus on price changes and real estate dynamics (Chen, Citation1996; Chen et al., Citation2010) with inadequate attention paid to the political economic environment in which these changes occurred. The contribution of this study is to relate the housing sector to general economic changes, especially economic crises and consequent changes in government policies.

China has rapidly developed its housing stock since 1979. Per capita housing space increased from 4 m2 in 1980 to 27.1 m2 in 2006 (China National Statistics Bureau [CNSB], Citation2005, Citation2009). Despite remarkable housing development, house price inflation has become a contentious issue in China. The issue of housing affordability is constantly raised at the annual meetings of the Peoples’ Congress. The ability of the state to regulate house prices is also hotly debated. For example, in the media there has been a saying that the chief executive (zong jingli) rather than the premier (zong li) decides house prices. Former premier Wen Jiabao responded to this comment in a dialogue programme on the Chinese Central Broadcast Network (www.cnr.cn), and vowed, ‘We should not avoid sensitive questions. Last year I promised to our people that within my office I shall keep house prices at a reasonable range. I will continue to achieve this objective without hesitation’ (Xinhua News Network,Footnote1 26 December 2010). Reports such as these show that the housing boom has become politicised. The risk of a housing market bubble has continued to be a hot issue since the third plenary session of 18th Communist Party of China Central Committee in November 2013 (Wu, Citation2013). Since 2014, however, the Chinese housing market has suddenly begun to face greater uncertainty. The third- and fourth-tier cities in particular have begun to see a downward trajectory in property values, which may lead to housing market division between the first-tier cities and the third- or fourth-tier cities (Wu & Ning, Citation2014).

The purpose of this paper is to go beyond a specific market analysis, which dominates China's real estate research, and identify driving forces behind housing booms. This paper is organised as follows. The next section briefly reviews the literature that understands housing change in the wider context of political economic transformation before going on to consider the context of political economic change in China. Our attention then turns to housing market cycles in Chinese cities, the centrality of property in housing consumption as well as evidence of capital investment as the driver for housing booms. The later sections turn to the issues of housing property in governance and regulation and ask as to what extent housing policy can be said to be a neoliberal one. Finally, our conclusion suggests that it is important to go beyond a purely market analysis of housing changes and see housing market cycles in China as the result of housing commodification and the state's attempt to regulate its consequences, including building booms.

Theoretical perspectives: the centrality of property development in advanced capitalism

The theoretical underpinning of this research originates from a more general perspective of the built environment in terms of capital circuits in advanced capitalism (Harvey, Citation1978) in which surplus capital is switched from the primary capital circuit of production to the secondary circuit of the built environment, deriving from an inherent over-accumulation tendency in the process of capitalist development. The theory of capital switching goes beyond the supply and demand relation in the housing market and relates the development of housing to the more general development dynamics of capitalism. This capital switching theory has been further explored in the context of the subprime mortgage crisis in the USA (Gotham, Citation2009), where the spatial fixity of housing was made more ‘liquid’ through financialisation of the real estate market and the securitisation of mortgages. Although the empirical evidence about the 1980s building boom in the USA does not support the claim that capital switching occurred (Beauregard, Citation1994), recent studies have begun to demonstrate the mechanism of converting home ownership into a financial asset, which may absorb surplus capital (Aalber, Citation2008; Gotham, Citation2009; Weber, Citation2010). The explanation pinpoints a driving force as well as a financial source for housing development. Such a perspective places the production of ‘property’ at the centre of capital accumulation in the process of urban development.

The centrality of property in the economy has been examined in the context of East Asian housing development (Haila, Citation2000; Smart & Lee, Citation2003a). Smart and Lee (Citation2003a) suggest that in Hong Kong, the ‘financialisation’ of property helps to maintain the stability and instability of accumulation. The importance of real estate is not only in its contribution to the government revenue of Hong Kong through land leasing but also in that it becomes the ‘centre of everyday life of the society’. Such a centrality once helped the development of a stable and growing process of capital accumulation, while at a later stage it triggered instability and volatile market changes. Further, their analysis applies regulation theory to the housing sector, and examines how regulation of housing has contributed to the instability of the market (see also Smart & Lee, Citation2003b). Haila (Citation2000) argues that both Hong Kong and Singapore are ‘property states’, but these two property states act differently. Hong Kong uses property as a budgetary (revenue) mechanism while Singapore uses it as a regulation instrument. The role of the state in raising the centrality of property is examined in Hong Kong, for example, by Forrest and Lee (Citation2004). They identify that the accumulation of property assets for specific cohorts of residents has been specifically fuelled by government homeownership programmes.

In the case of Japan, Kerr (Citation2002) studied the role of land development in post-war Japanese development and found that a ‘land myth’ placed land at the centre of economic growth. In the case of the Asian financial crisis, the boom and bust of the housing market in Bangkok has been examined by Sheng and Kirinpanu (Citation2000), who consider the growth of the housing market as driven by capital accumulation. Quigley (Citation2001) and Fung and Forrest (Citation2002) have also studied the influence of the property market on the Asian financial crisis. These studies link the housing sector and the economic crisis. More recently, the thesis of the ‘financialisation of home’ is examined with reference to the subprime crisis in the USA (Aalbers, Citation2008). Kim and Renaud (Citation2009) described the increase in housing prices in the western developed economies from 1997 to 2006, which is closely linked to massive global credit expansion and housing mortgage securitisation. Watson (Citation2010) meanwhile, has examined housing price changes in the UK and traced their root to the contradiction between financial literacy and asset-based welfare promoted by the Labour government.

These studies expand the view of housing price changes outside the sphere of housing. This approach is useful because it goes beyond the specific housing sector and relates the sector to the wider economy, capital accumulation, and regulation. This kind of analysis is needed for China as, currently, real estate analysts attempt to forecast house price changes purely through market fluctuation analysis.

Analytical framework: changing capital accumulation and housing development in China

From the perspective of capital accumulation, China has experienced a transition from state-led industrialisation to land-centred urban development. The objective of reform is to expand the scope of accumulation on the world stage (i.e., becoming the world's workshop), and to extend into a new space of accumulation, namely the extension of market mechanisms into housing and land development. The difference in the regime of accumulation before and after economic reform can be summarised as follows.

The regime of accumulation before economic reform was characterised by the following features: (1) the state's dominance in resource allocation; (2) significant resources devoted to industrial production (manufacturing); (3) labour reproduction achieved through collective consumption, and in particular under the organisation of state work-units; (4) the built environment treated not as an investment outlet but rather as a pure burden to the state, as non-productive but necessary funding items; (5) over-accumulation tendencies (under-developed mass consumption), which did not lead to a crisis because the problem was circumvented by free allocation of housing and welfare; and (6) consumption not serving as the driver for growth.

Since the economic reform, a new regime of accumulation has been developed. This development regime is created by expanding production capacity for overseas markets and attracting foreign investment in economic development. Housing has been commodified, and changed from an occupation-related benefit to a private consumption item and household asset, and is regarded as an investment opportunity during a housing boom. The change in capital accumulation is accompanied by related regulation changes. Economic decisions have been decentralised to the local government level with greater local discretion. Major changes include economic decentralisation, fiscal reform, and downloading management tasks to localities. In state socialism, extensive state-led industrialisation required the regulation mode of ‘central planning’, which played a key role in resource allocation. Through concentration of social surplus into the state bureaucratic system, the state played a redistributive role. Now, with a much decentralised form of accumulation, the mode of regulation has witnessed the rising entrepreneurialism of local government, transforming the local state from ‘regulator’ to ‘market agent’.

This perspective of capital accumulation is particularly useful because it helps reveal the different roles of housing in different accumulation regimes. In the previous centrally controlled regime, housing was a burden to the state and the local government was reluctant to develop more housing. After housing commodification, housing became an investment item, as real estate, and now provides revenue through land sales to the local government. To homeowners, housing is an asset that can retain the benefit of value appreciation and is believed to be an effective method to cope with the impact of inflation. From this perspective of capital accumulation, we can see why property development occupies a central position in China's overall development.

The extensive body of literature now provides a clear picture of the changing characteristics of housing. The development of the housing market can be divided into two stages (Wang, Shao, Murie, & Cheng, Citation2012). The initial stage (1979–1998) is the expansion of the so-called ‘commodity housing’ market, mainly driven by in-kind housing allocation by state-owned enterprises (work-units). Work-units used their self-raised funds and retained revenue to buy commodity housing for their employees. The growth of commodity housing thus circumvented the constraint of low affordability. By the mid-1990s, this pragmatic housing reform had reached a dead end. Although the housing market was not fully established, housing subsidies incurred a huge financial burden for state work-units.

The second stage started in 1998. The housing policy adopted in 1998 was a milestone in China's housing reform. In-kind housing allocation was abolished, which had been an integral part of the package of expansionist macroeconomic policy. The ‘financialisation’ of the Chinese housing sector had begun. Housing mortgages became available for better-off households (Wang, Citation2001), significantly raising affordability. Better-off households tended to be those which gained higher market remuneration and owned free or heavily discounted public housing (Logan et al., Citation2009). Now, equipped with new financial instruments and the expectation of asset appreciation, they aggressively entered the commodity housing market and drove prices to a new high. Many became second or even third homeowners.

Housing market cycles in urban China

China has experienced five housing market cycles since 1979. summarises these major cycles and their historical conditions. The first boom was a minor one after the initial housing reform started in selected cities in the early 1980s. The cities in the housing reform experiment began to see a buoyant but controlled market in the 1980s. The extent of the housing market within the overall size of housing provision was quite limited. The initial experiment of housing reform ended with hectic inflation caused by the dual track system of prices, which led to the 1989 Tiananmen event and an overall downturn of the economy from 1989 to 1991.

Table 1. Housing market cycles in China, 1982–2013.

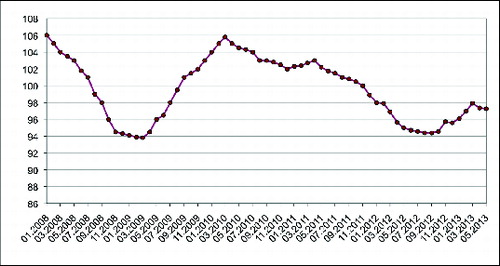

Figure 1. The housing price index from China Real Estate Index System (CREIS) in 70 major cities in China. Source: CNSB, various years.

The second boom started after Deng Xiaoping's southern China tour. The full-fledged reform package led to a fever of development zones and rampant land development from 1992 to 1994. This stage was characterised by fiscal devolution, and the central government signed fiscal contracts with local governments, which reduced the proportion of central government revenue. In 1994, former premier Zhu Rongji developed a tax-sharing system and tightened up microeconomic control. This boom ended with the collapse of the rampant market in Hainan Island, the city of Beihai, and the downturn of the property market in Guangzhou and Shanghai. From 1995 onwards, the housing market slowly declined and was generally inactive. The 1997 Asian financial crisis made the downturn worse. The crisis hit China's export and foreign direct investment hard. The impact on offices and other property markets was also severe. To boost domestic demand, the Chinese government adopted a radical reform package, abolished in-kind housing allocation and started market-oriented housing reform (Li & Yi, Citation2007; Wang, Citation2001).

The market-oriented reform, characterised by housing commodification, rejuvenated the housing market from 1999. shows the official housing index from the China Real Estate Index System (CREIS) (known as zhongfang zhishu). The CREIS is a widely recognised index for the housing market in China, compiled by the National Statistics Bureau and based on the sampling of properties initially from 35 cities and later from 70 cities since 2005. The index covers new commodity housing. Although the housing market started to recover from 1999, substantial growth did not start until 2002. In 2002, the third and major housing boom started and was sustained for several years until the recent global financial crisis, despite the tightening of land market management in 2003 and 2004. The new commodity housing index of CREIS increased from 97.9 points in the first quarter of 1998 to 145.1 points in the second quarter of 2006, a relatively modest increase of 1.5 times in this period. But it should be noted that the index is drawn from the national sample as an average and does not reflect individual cities which saw a much more significant boom. The index was criticised for being too conservative. It was reported that house prices nationwide jumped 12.5% year on year in 2004, and for Shanghai up to 14.6%. In 2006, after the state tightened control over land supply and the housing market, house prices did not decline but rather leapt to a new high, especially in the cities of Beijing and Shenzhen. In the first quarter of 2006, house prices in Beijing increased by 17.9%.Footnote2

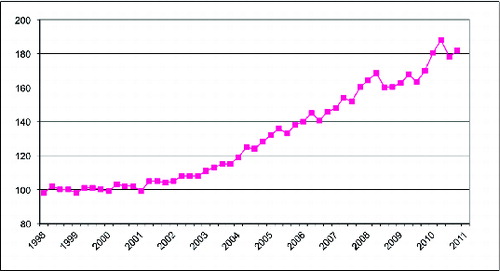

Figure 2. The change (in percentage) in housing price index in major Chinese cities. Source: CNSB, various years.

According to changes in the house price index (), it can be seen that starting from 2006 the housing market began to cool down in response to a series of housing tightening policies. Potential buyers began to hold back their purchase decisions, although the housing market did not see a sharp downturn. The housing market entered a quiet period. However, in 2007, just before the bursting of the global financial crisis, the tide of the housing market turned again to another period of frenetic growth. This was the fourth housing boom, which had rather a short life. The driver for this boom was not economic growth but rather the deterioration of Chinese manufacturing industries immediately before the global economic crisis. The increase in the minimum wage and the rise in labour costs in general, plus a higher interest rate in late 2007, imposed a pressure on labour-intensive small and medium enterprises (SMEs). The bust of the stock market in 2007 led to the outflow of capital. For some SMEs in manufacturing industries, it became more profitable to invest in the property market than to engage in production. This may be similar to the declining profit rate in the production sphere which causes the switching of capital into the second circuit of capital accumulation hypothesised by Harvey (Citation1978) in advanced capitalism. The fourth boom was hit by the much more severe downturn caused by the global economic crisis in 2008.

The winter of 2008 was a period of housing market downturn. The house price index recorded zero growth in the fourth quarter of 2008, and then fell into negative growth in the first quarter of 2009, which had not been seen since 2000 when the property market recovered from the Asian financial crisis. But the central government acted swiftly by initiating a stimulus package of 4 trillion yuan. The stimulus package consisted of major investment in infrastructure projects. To boost construction, the fund was allocated on a competitive basis, which greatly invigorated local governments’ enthusiasm for pushing forward with land supply to secure the conditions for these projects. The central government also injected capital liquidity, and fiscal policy abruptly reversed from tightening in the first half of 2008 to expansion. After several downward adjustments, a reduction of 1% in the bank deposit requirement released 450 billion yuan for investment. Bank loans thus greatly eased capital constraints on developers. The minimum capital requirement for commodity housing projects was reduced from 30% to 20%, and the down payment for house purchase was reduced to 20% from October 2008. The development of housing was again chosen as an economic growth booster, just like the measure adopted after the Asian financial crisis in 1997. In 2009, the central government announced a 33 billion yuan investment in ‘social security housing’, which extended the category of affordable housing. Social security housing is government-funded housing development with price discounts or restrictions for qualified low-income families. Thus, beginning in mid-2009, China has seen its fifth property boom so far.

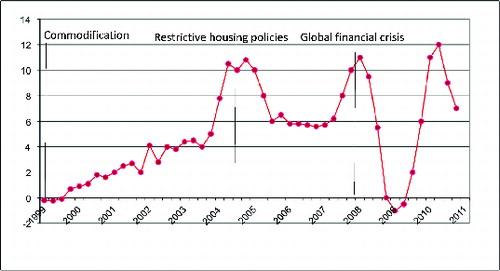

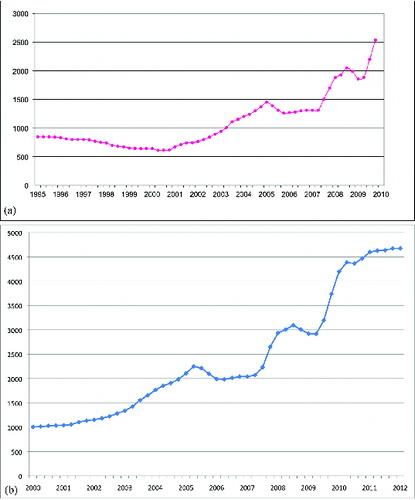

The fifth housing boom started with a significant sale. CNSB (Citation2010) shows that in March 2010 the house price index in 70 cities increased by 11.7%. In the first quarter, investment in real estate reached 659 billion yuan, an increase of 35.1%; the opening of new construction space amounted to 323 million m2, an increase of 60.8%, and the sale of commodity housing was 797.7 billion yuan, an increase of 57.7%. The Chinese Housing Market Climate Index (known as guofan jingqi zhishu) reflects such a V-shaped recovery of market confidence (). The index reached a peak in April 2010, just before the announcement of a tougher housing policy by the central government in May 2010. However, measured by house prices and investment, the fifth housing boom continued. In December 2010, China recorded the fourth consecutive month of price increases, according to information released by CNSB (Citation2010). The price of newly built residential properties increased by 7.6% compared with the same period in the previous year, among which commodity housing increased by 8.5%. In the whole of 2010, real estate investment was 4826.7 billion yuan, a yearly increase of 33.2%, among which investment in commodity housing was 3403.8 billion yuan, an increase of 32.9%. Housing investment accounted for 70.5% of investment in real estate, indicating that the housing boom was the key driver for property growth. The boom was characterised by a significant increase in land purchases. Measured by space, the purchase area was 410 million m2, an increase of 28.4%. However, land revenue from land purchase reached 999.2 billion yuan, a stunning growth of 65.9%. For individual cities, taking Shanghai as an example, the trajectory of house price changes is similar to the general trend but with some more dramatic changes and stronger growth impetus. shows the change in the CREIS for Shanghai. Since December 2009, the Shanghai CREIS has been adjusted to take the index of October 1999 as the base line of 1000 points (originally 640).Footnote3 Therefore, the index is presented in two charts. (a) represents the pre-adjusted index to show a longer history. From the figure, we can see that the impact of the Asian financial crisis on Shanghai's housing market is more severe than its impact on the national market because Shanghai had a higher concentration of foreign companies and multinationals and has been more export-oriented. The downturn trajectory in Shanghai was not reversed until the end of 2000. Consequently, prices rebounded more swiftly when China joined the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 2001, which opened up a great opportunity for the development of the world workshop in the Yangtze River Delta as Shanghai's hinterland. The decline of the third boom in Shanghai was also very obvious in 2005. The fourth boom starting in 2007 pushed house prices in Shanghai to a new high, jumping from the first quarter of 2007 at 1310 points to the fourth quarter of 2009 at 2536 points. In other words, house prices nearly doubled in just three years. As CREIS is derived from a sample of properties in the whole metropolitan area, the increase in house prices in premier locations within the inner ring road would be more significant.

Figure 4. (a) CREIS Shanghai Index (before the adjustment of the baseline in 2009). (b) CREIS Shanghai Index (after the adjustment of baseline in 2009). Source: CREIS Shanghai Office, various years.

(b) shows the adjusted indexFootnote4 after October 2009, which presents a similar trend. Despite a slight decline in the third quarter of 2010, prices continued to grow strongly. The CREIS Shanghai Office Citation(2009, 2010) admitted that growth in 2009 was frenetic with a record of 42% price inflation. In 2010, however, the growth rate was more constrained although still significant. Only four cases among 102 samples of the index system experienced a 5.9% decrease. However, these four projects were located either in the exurbs or outside the outer ring road, which suggests that all cases in the main area of Shanghai still experienced significant price increases (CREIS Shanghai Office, 2009, Citation2010).

To sum up, both national and Shanghai data show significant increase in house prices since the adoption of a more radical market approach. Despite the cycles of the housing market, there have so far been no major corrections on such a scale that we may describe them as the bursting of a property bubble. For the city of Shanghai, the change in prices was more spectacular, and since 1999 property prices have inflated 4.5 times since the abolition of in-kind housing provision.

The centrality of property in housing consumption

This section tries to place the extraordinary housing boom in the context of property development and its centrality in housing consumption. It is argued that housing is becoming a property that is central to urban development in the post-reform era. Through housing reform, the state has retreated from the direct provision of public housing. While the reform takes a gradual approach, the accumulated effect is significant (Logan et al., Citation2009), because those who managed to buy their public housing received the benefit of asset appreciation with the housing boom, which enlarged housing inequalities between those who were entitled to better housing and those who were not. Since the abolition of in-kind housing provision in 1998, China's housing policy has been geared towards prioritising market provision. The public housing sector has been declining and becoming residual. The shift in housing tenure has been radical. China is now a nation of homeowners. According to the population census in 2000, the rate of homeownership in cities reached 72% and in towns 78% among urban households. According to the National Statistical Bureau,Footnote5 in 2010, among urban residents the homeownership rate reached 89.3%, among which 38% own commodity housing, 11.2% own inherited private housing, and 40.1% own privatised public housing (known as ‘reform housing’). The percentage of homeownership among urban residents indicates pervasive housing commodification and privatisation. It could be argued that a large amount of the rural migrant population in the cities do not own housing actually in the cities. But many still own a house in their rural area. Housing, which used to be an important item of collective consumption in urban China, is now becoming an asset of capital appreciation. Those who bought discounted housing in the sale of public housing or purchased new market housing gained windfall wealth (Logan et al., Citation2009), because house prices have appreciated annually in double digits since 2000. Many began to buy second or even third properties and collect handsome rents while enjoying asset appreciation (Huang & Yi, Citation2010).

Initially, housing commodification was justified as a measure to tackle the chronic housing shortage left by the socialist era. Housing commodification in the 1990s helped overcome political resistance towards radical privatisation and private housing consumption, because housing reform adopted a gradual approach. That is, the production of housing was commoditised through the housing market in which development companies played a role in housing development. But on the consumption side, there was a lingering role for work-units in buying housing from the market and then allocating them as in-kind benefits. This muddling-through approach reflects the gradual nature of housing reform (Logan et al., Citation2009).

This gradual way was politically successful because it smoothed resistance towards housing privatisation and allowed the establishment of the housing market under conditions of very low affordability. The housing policy was adopted to overcome the bottleneck of affordability. The government waived the land charge for affordable housing, which in reality helped better-off households become homeowners. A mortgage market was established to enhance purchasing power but again it favoured high-income households (Wang, Citation2001). As a consequence, better-off households with mortgage-supported ownership gained the benefit of home ownership and asset appreciation. The sale of public housing was also muddled through with heavy discounts, although resale was restricted in the initial five years. Ownership benefited those who had had housing advantages under work-unit socialism (Logan et al., Citation2009). Through the housing reform, a large proportion of housing stock was produced through quasi-market approaches.

The retreat of the state from public housing provision has facilitated and reinforced the centrality of property in housing consumption. In the Chinese statistics, housing investment is now listed together with investment in fixed assets, in contrast to the earlier definition of housing investment as a ‘non-productive item’ in the socialist era. Housing is now treated as an asset rather than shelter. To individual households, the decision to buy a home is increasingly seen and justified by the imperative to preserve present savings and gain asset appreciation in the future. The policy of housing commodification adopted in 1998 transferred the responsibility for getting housing from employers to individuals. Although the policy is quite pro-market, in terms of housing tenure change, it was also quite modest and proposed that the composition of housing tenures in Chinese cities should contain three components: about 70% to 80% of housing would be affordable housing; about 10% to 15% would be high-standard commodity housing; and about 10% to 15% would be social rental housing supported by either employers or the government (CitationWang et al., 2012).

However, in reality, housing commodification has been implemented more aggressively. The provision of housing has been biased towards the development of ‘commodity housing’. In the beginning, the so-called ‘affordable housing’ developed with land subsidy was developed and bought by better-off households because there was no qualification check. After some criticism, affordable housing development was halted and no longer formed the major component of the housing system. The recent official figure indicates that affordable housing accounted for only 4.6% of housing provision in 2004 (Peoples’ Daily, 8 June 2005). Further, the public rental sector has been privatised and become a residual housing sector. Housing privatisation is pervasive. Even in low-income neighbourhoods, public housing has been sold at a heavily discounted price. State enterprises initiated various programmes to privatise their assets. The level of privatisation reaches all possible buyers. On the other hand, the new scheme of social rental (lianzhu fang) has been severely under-developed. The Ministry of Construction (MoC) (now Ministry of Housing and Urban and Rural Development, MOHURD) announced that more than 70 cities had not developed social rental housing in 2006.Footnote6

To sum up, since the late 1990s commodity housing has become the dominant form of housing provision; affordable housing and social rental housing are still limited in Chinese cities. Further, housing consumption has become essentially a form of private consumption. There is greater differentiation in the housing market in terms of location and quality (Logan et al., Citation2009). For example, for the upwardly mobile middle class, housing consumption is becoming a way of defining their social status and in turn they are pursuing desirable forms of housing, for example living in luxury and lavish gated communities (Zhang, Citation2010).

Capital investment as a driver for the housing boom

China has been a country with high savings and investment rates, and for a long period of time has maintained a relatively low real interest rate compared with Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries (Gong & Lin, Citation2005). The low real interest rate means that China has high capital liquidity, which increases the incentive to invest in real estate. The dominance of state banks in absorbing and collecting savings has led to the accumulation of capital in the banking system. The accumulation of capital in the banking system created an enormous pressure for banks to find outlets for accumulated capital in the 2000s. In the middle of the housing boom of 2005, the gap between bank loans and deposits reached 9000 billion yuan. Mr Ren Zhiqiang, the CEO of a large real estate development corporation, called the capital in the banks the ‘tiger in the cage’, and suggested that property development should be chosen as the outlet for capital investment.

The growth of savings in the banks has been phenomenal, reflecting the change in the structure of the economy. The ratio of year-end saving to GDP also rose from about 40% in 1992 to more than 76.5% in 2010 (CNSB, Citation2010). This means that compared with GDP growth, bank savings saw more rapid accumulation. The under-developed social security system meant a strong preference for saving for the unforeseeable costs of healthcare, education, and elderly care. However, because of low interest rates, savings in the banks are becoming devalued. The appreciation of housing value in the last decade gives a strong signal that housing investment could be an alternative channel to protect asset values. According to Mr Chen Huai, the director of the Housing Policy Research Centre of MOHURC, ‘Too many households treated their house as a money deposit machine’, and indeed the most effective way of realising housing investment opportunities for the government is to ‘demolish half of the Chinese city’ (Chen, Citation2010, p. 9).

The housing boom in China has been driven by increasing bank loans in the housing market, both as mortgages and as loans to real estate enterprises. For example, at the peak of the housing boom, the volume of bank loans reached 1260 billion yuan in the first quarter of 2006, accounting for almost half of the whole year loan target, and about 50% flowed into the real estate sector. China's GDP growth has been driven by high rates of investment in fixed assets. The share of fixed asset investment in GDP rose from 24% in 1990 to 41.2% in 2005, 55.6% in 2007, and to 65% in 2009 (CNSB, Citation2010). Housing investment is an important item in fixed asset investment and has seen a significant increase over the years. Capital inflow from the banking system into property development paved the way for the housing boom in the mid-2000s.

To sum up, commoditising ‘homes’ as more liquid property, transforming housing development as property development, and treating housing consumption as a channel of asset appreciation have led to increasing capital investment in housing, which became the driver for the housing booms in China in the 2000s.

The centrality of property development in regulation

Property development in general and housing development in particular play a key role in urban development (Lin, Citation2009). Extensive studies on urban China now suggest that China's urban development has been land-driven (Hsing, Citation2010; Lin, Citation2009). The housing price cycle is influenced by the politics of land development. In the pro-growth development regime (Zhu, Citation2005), central and local governments have different positions. For the central government, the top priority is the control of financial risk and rampant development. When house prices increase too fast, there is wide discontent over housing affordability. The lack of access to decent housing is regarded as detrimental to the development of a ‘harmonious society’. To achieve these objectives, several ministries jointly announced policies to constrain a housing bubble. Recently, the central government has shown its position in housing price control more openly. For example, in 2006 the State Council criticised the municipal governments of Beijing and Shenzhen for their failure to control house price inflation.

However, local government is more pro-development, because it is estimated that about 30%–40% of local revenue comes from land sales. Local governments thus have an incentive for land development. The performance of local officials is evaluated and promoted on the basis of GDP growth rates. For ambitious local officials to achieve a good performance in office, property development is the most effective instrument to attract investment. They are unwilling to adopt more stringent measures to slow down land and housing development. However, they can only passively resist the policy of the central government, and sometimes have to show that local policies are in line with central government requirements, because the central government still maintains the power to appoint local leaders, as the political system remains hierarchical despite economic devolution (Chien, Citation2008).

Despite the differences in regulating housing prices, the central government does not want to exert too harsh policies that might lead to a crash in the housing market. The central bank still regards real estate as the engine for economic growth.Footnote7 The collapse of the housing market might cause a serious local debt crisis because various ‘investment platforms’ – local development corporations backed up by the local government – have used land as collateral with the banks to borrow capital for property development. They could become insolvent if property prices declined.

To sum up, property development has become a key issue in the ‘mode of regulation’, because the state has to balance the need for maintaining the momentum of economic growth and the imperative of curtailing financial risk. A buoyant property market may lead to a crisis of housing affordability, which in turn may generate social discontent and speculative property investment. This would then undermine the ‘structural coherence’ of the regime of accumulation. To avoid this scenario, the home as a commoditised property is central to governance and regulation. Contrary to the regime of the welfare state, the regulation of homes does not originate from a purpose of redistribution but rather is more associated with investment stimulus and financial risk.

Towards a neoliberal housing policy?

The commodification of housing and financialisation of housing investment may imply a neoliberal approach to housing provision in the world. The global financial crisis and subsequent housing foreclosure crisis generated a debate on neoliberalism (Harvey, Citation2005). Harvey observed that China is a strange case of neoliberalism because it combines pro-market policy with state authoritarianism. Regarding strong state control over the course of economic reform, it is argued that the presence of state control is a reaction to marketisation rather than a legacy of the previous regime (Wu, Citation2010). In the Chinese housing market, Wang et al. (Citation2012) argue that neoliberal housing policies are not simply one way towards the deregulation of housing but rather that housing reform and regulation policies changed frequently in response to market conditions, leading to what they call the ‘maturation’ of a neoliberal housing market. The housing booms in China and market cycles reflect the role of the state in both creating the conditions for market speculation and containing the damage of market cycles.

First, the state plays a significant role in paving the way towards the housing boom. In the aftermath of the Asian financial crisis and more recently the global financial crisis, the state either adopted a strongly aggressive pro-market policy to reverse the economic downturn or mobilised financial power to pump in capital liquidity. Both measures use the housing market and property development to achieve objectives beyond the housing sphere.

Second, in the period of the buoyant housing market, the state began to tackle the issues of housing affordabilityFootnote8 and financial risk. This may then deviate from neoliberal housing policies and promote stronger state intervention. State intervention may alter market conditions and turn the housing boom into a temporary downturn of the housing market. For example, from 2006 housing policies turned from an expansionist to a more conservative approach. The State Council began to formulate ‘Six Measures’ to stabilise house prices.Footnote9 The resurgent role of the state is reflected in the series of orders, decrees, and policies over a short period.

It is interesting to note that, although the state has retreated from the direct provision of housing, the housing market cannot fulfil the task of affordable housing provision. Rather, the centrality of property development has led to greater inequalities in access to housing and consequential financial risks. The problems and risks require the state to act. In 2006 at the peak of the housing boom, we see that the state had to tighten credit provision, reduce land hoarding to prevent speculation, control house price inflation by increasing down payments, propose social housing (known as social rental housing, lianzufang), designate a requirement for a proportion of smaller units (known as the policy of 90/70, namely the proportion of housing with floor space less than 90 m2 should reach 70% of the total floor space of housing projects), constrain the pace of housing demolition, and implement a new property tax experiment in Shanghai and Chongqing. More dramatic change occurred in 2011 when the central government required the local governments of 49 major cities to implement housing purchase restrictions to exclude non-local homebuyers and set a maximum of one unit of commodity housing units. In Beijing, for example, buyers must present five-year tax payment evidence to the Beijing municipal government for commodity housing purchase.

The strengthening of the state role in the housing market contradicts the original design of the ‘neoliberal’ policy, which suggests that the centrality of property in social reproduction is an unaccomplished objective. Both the promotion of housing commodification and the restriction of housing sales exacerbated rather than reduced the housing market cycle.

Conclusion

This paper analyses housing market cycles in China and finds that the volatility of house prices is driven by housing financialisation and state intervention in response to global macroeconomic crises, which exacerbate rather than reduce their cyclic nature. The theoretical underpinning of our analysis is the centrality of property development in the process of Chinese urbanisation and economic growth, a thesis that has been explored in western advanced capitalism (Harvey, Citation1978) and East Asian housing markets (Smart and Lee, Citation2003a). Doling and Ronald (Citation2014) examined housing as a growth machine and the features of developmental states across East Asia. The thesis is still under-studied in the Chinese context. Through housing commodification, housing is becoming a more ‘liquid’ asset (Gotham, Citation2009), which attracts investment in homeownership and is used by the government to boost investment in housing production and domestic consumption at various times to cope with the decline of export markets due to economic and financial crisis.

Thus, the inflation of house prices paradoxically co-exists with relatively low affordability (Chen, Citation1996; Chen et al., Citation2010). Through bringing housing development as commodity production in the circuit of capital, the new process of property development significantly expands the scope of accumulation, which has greatly stimulated the production of housing. The result is that housing has become an outlet for capital investment and plays a critical role in capital appreciation, which becomes the underlying dynamics of the housing boom in China's post-reform period.

The state played an important role in the building of housing booms. But the roles of the central and local states are different. The central government provided initial policy drivers, which set the conditions for a housing boom. For example, housing reform was speeded up to commoditise housing production and consumption in the aftermath of the Asian financial crisis in 1997, and a financial stimulus package was adopted to increase capital liquidity and investment in infrastructure and fixed assets after the global financial crisis in 2008. Both policies contributed to the two major property booms in China. On the other hand, the central state is very concerned with financial risk, the lack of housing affordability, and social discontent. Thus, alongside the boom, the central government has to intervene. However, the local governments adopted a more aggressive approach to the promotion of property development. This is often operated through the so-called ‘local investment platforms’, for example land development corporations, because land sales are an important source of local revenue.

Despite the housing market cycles, Chinese housing prices in general have experienced significant inflation since 1998. Housing booms and consequent decline lead to potential financial risk, as shown in the bursting of property bubbles in Japan in the 1990s (Kerr, Citation2002), the property-triggered Asian financial crisis (Forrest & Lee, Citation2004; Sheng & Kirinpanu, Citation2000; Smart & Lee, Citation2003a), and the more recent subprime crisis (Aalbers, Citation2008; Gotham, Citation2009). The specific risk for Chinese cities might be the bankruptcy of local investment platforms backed by the government. As a result, the state has been forced to intervene in the housing boom, suggesting that the centrality of property development may not automatically lead to a more neoliberal housing policy, but rather that housing commodification and the financialisation of homes are necessarily an unaccomplished transformation.

Acknowledgements

The paper has been presented in International Sociological Association RC43 Conference 2013: At Home in the Housing Market, Amsterdam, 10–12 July 2013. The author wishes to thank Richard Ronald, the conference organiser, for his support. The author also thanks anonymous referees for their constructive comments and Suzanne Fitzpatrick and Richard Ronald for their editorial guidance. This research is supported by the UK Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC)/Department for International Development (DFID) project (RES-167-25-0448) and the Ministry of Education of PRC project at Modern City Research Centre at East China Normal University (11JJD840015).

Notes

1. http://news.xinhuanet.com/fortune/2010-12/26/c_12918677.htm.

2. Data from house.sina.com.cn, accessed 30 March 2006. However, the total volume of transactions has declined. According to the State General Bureau of Taxation, from January to April 2006 the total amount of stamp duty nationwide increased by only 7.4%, while in the same period the increase for 2005 was 63%. For Beijing, stamp duty was 20% lower than the equivalent figure in 2005. This suggests that the volume of transactions has declined. Consumers began to hold on and wait for a clear market trend.

3. The relationship between the earlier index and the adjusted index is not a straightforward one. The CREIS office has made retrospective adjustments and they are not necessarily compatible.

4. The reason for adjusting the index is not very clear. Considering it was adjusted in December 2009, there might be pressure to provide a less dramatic price fluctuation. According to the old index, in 2009 prices increased by 1.37 times, while the new index smoothed out the increase to 1.28 times. However, this is only speculation and might not be valid.

5. Accessed from http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjfx/ztfx/sywcj/t20110307_402708357.htm.

6. Accessed from house.people.com.cn/xinwen/060524/article_0900.html.

7. For example, in the ‘121 Document’ published by the central bank, the role of real estate is confirmed and emphasised.

8. At the 10th Peoples’ Congress in 2005, the inflation of house prices was raised as a threat to the construction of a ‘harmonious society’. In subsequent ‘two-congresses’ (lianghui) (Peoples’ Congress and the Congress of Chinese Political Consultation), housing was constantly raised as a major topic.

9. These six points include: (1) to adjust the structure of housing provision and strategically to develop medium- to low-price housing, and middle-to-small ordinary commodity housing, affordable housing, and social rental housing. The local government should promulgate and implement housing construction plans and propose detailed requirements for the structure of newly constructed housing; (2) to use taxation, bank loans, and land policy measures to control land hoarding; (3) to control the scale and pace of housing demolition so as to reduce the demand for secondary housing; (4) to consolidate the order of the real estate market and strengthen the monitoring of development processes; (5) to speed the construction of social rental housing, and to develop affordable housing and the secondary housing market and rental housing to solve the housing problem of lower income households; and (6) to develop real estate statistics and market transparency, and provide accurate information.

References

- Aalbers, M.B. (2008). The financialization of home and the mortgage market crisis. Competition & Change, 12(2), 148–166.

- Beauregard, R.A. (1994). Capital switching and the built environment: United States, 1970–89. Environment and Planning A, 26(5), 715–732.

- Chen, A. (1996). China's urban housing reform: Price-rent ratio and market equilibrium. Urban Studies, 33, 1077–1092.

- Chen, H. (2010, August 16). Old houses have to go for greater good. China Daily, p. 9.

- Chen, J., Hao, Q., & Stephens, M. (2010). Assessing housing affordability in post-reform China: A case study of Shanghai. Housing Studies, 25(6), 877–901.

- Chien, S.-S. (2008). The isomorphism of local development policy: A case study of the formation and transformation of national development zones in post-Mao Jiangsu, China. Urban Studies, 45(2), 273–294.

- China National Statistics Bureau (CNSB). (2005, 2009). China statistical year books 2005, 2009. Beijing: China Statistical Press.

- China National Statistics Bureau (CNSB). (2010). Information about house price inflation. Retrieved February 20, 2011 from www.stats.gov.cn

- China Real Estate Index System. (2009, 2010). December report of Shanghai CREIS change, 2009/2010. Shanghai: CREIS Office.

- Doling, J., & Ronald, R. (2014). Housing East Asia: Socioeconomic and demographic challenges. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Forrest, R., & Lee, J. (2004). Cohort effects, differential accumulation and Hong Kong's volatile housing market. Urban Studies, 41(11), 2181.

- Fung, K.K., & Forrest, R. (2002). Institutional mediation, the Asian financial crisis and the Hong Kong housing market. Housing Studies, 17(2), 189–208.

- Gong, G., & Lin, J.Y. (2005). Over impact: An explanation for China's economic deflation. Working Paper. Beijing: China Economic Research Centre.

- Gotham, K.F. (2009). Creating liquidity out of spatial fixity: The secondary circuit of capital and the subprime mortgage crisis. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 33(2), 355–371.

- Haila, A. (2000). Real estate in global cities: Singapore and Hong Kong as property states. Urban Studies, 37, 2241–2256.

- Harvey, D. (1978). The urban process under capitalism. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 2, 101–131.

- Harvey, D. (2005). A brief history of neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hsing, Y.-T. (2010). The great urban transformation. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Huang, Y., & Clark, W.A.V. (2002). Housing tenure choice in transitional urban China: A multilevel analysis. Urban Studies, 32(1), 7–32.

- Huang, Y., & Yi, C. (2010). Consumption and tenure choice of multiple homes in transitional urban China. International Journal of Housing Policy, 10(2), 105–131.

- Kerr, D. (2002). The ‘place’ of land in Japan's post-war development, and the dynamic of the 1980s real-estate ‘bubble’ and 1990s banking crisis. Environment and Planning D, 20, 345–374.

- Kim, K.-H., & Renaud, B. (2009). The global house price boom and its unwinding: An analysis of a commentary. Housing Studies, 24(1), 7–24.

- Li, S.M. (2010). Mortgage loan as a means of home finance in urban China: A comparative study of Guangzhou and Shanghai. Housing Studies, 25(6), 857–876.

- Li, S.-M., & Yi, Z. (2007). The road to homeownership under market transition: Beijing, 1980–2001. Urban Affairs Review, 42(3): 342–368.

- Lin, G.C.S. (2009). Developing China: Land, politics, and social conditions. London: Routledge.

- Logan, J., Fang, Y., & Zhang, Z. (2009). Access to housing in urban China. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 33(4), 914–935.

- Quigley, J. (2001). Real estate and the Asian crisis. Journal of Housing Economics, 10, 129–161.

- Sheng, Y.K., & Kirinpanu, S. (2000). Once only the sky was the limit: Bangkok's housing boom and the financial crisis in Thailand. Housing Studies, 15(1), 11–27.

- Smart, A., & Lee, J. (2003a). Financialization and the role of real estate in Hong Kong's regime of accumulation. Economic Geography, 79(2), 153–171.

- Smart, A., & Lee, J. (2003b). Housing and regulation theory: Domestic demand and global financialization. In R. Forrest and J. Lee (Eds.), Housing and social changes: East-west perspective (pp. 87–107). London: Routledge.

- Wang, Y.P. (2001). Urban housing reform and finance in China: A case study of Beijing. Urban Affairs Review, 36(5), 620–645.

- Wang, Y.P., & Murie, A. (1999). Commercial housing development in urban China. Urban Studies, 36, 1475–1494.

- Wang, Y.P., Shao, L., Murie, A., & Cheng, J. (2012). The maturation of the neo-liberal housing market in urban China. Housing Studies, 27(3), 343–359.

- Watson, M. (2010). House price Keynesianism and the contradictions of the modern investor subject. Housing Studies, 25(3), 413–426.

- Weber, R. (2010). Selling city futures: The financialization of urban redevelopment policy. Economic Geography, 88(3), 251–274.

- Wu, F. (2010). How neoliberal is China's reform? The origins of change during transition. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 51(5), 619–631.

- Wu, F. (2013, November 13). Deflate the housing bubble. China Daily, p. 9. Retrieved from www.chinadaily.com.cn/opinion/2013-11/13/content_17100443.htm

- Wu, F., & Ning, Y. (2014, March 12). Housing market faces division. China Daily, p. 10. Retrieved from www.chinadaily.com.cn/opinion/2014-03/12/content_17340354.htm

- Zhang, L. (2010). In search of paradise: Middle-class living in a Chinese metropolis. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Zhou, M., & Logan, J.R. (1996). Market transition and the commodification of housing in urban China. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 20, 400–421.

- Zhu, J. (2005). A transitional institution for the emerging land market in urban China. Urban Studies, 42(8), 1369–1390.