Abstract

In many countries, the demographic shift towards an ageing population is occurring against a backdrop of welfare state restructuring. The paradigm of asset-based welfare may become increasingly central to these developments as individualised welfare is touted as part of the response to the challenge of funding the care of an ageing population. This article focuses on the framing of housing wealth as a form of asset-based welfare in the UK context. We consider the strengths and weaknesses of housing as a form of asset-based welfare, both in terms of equity between generations and equality within them. We argue that housing market gains have presented many homeowners with significant, and arguably unearned, wealth and that policy-makers could reasonably expect that some of these assets be utilised to meet welfare needs in later life. However, the suitability of asset-based welfare as a panacea to the fiscal costs of an ageing population and welfare state retraction is limited by a number of potential practical and ethical concerns.

Introduction

One of the recurring debates in public policy concerns the extent of state-provided welfare: how it should be distributed and how it should be financed. A pertinent and timely reminder of these tensions is the significant and lasting shift towards an ageing population across many nations of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) which raises serious fiscal challenges for social policy and welfare systems where retired people are supported by a proportionally shrinking working age population.Footnote1

This change in the dependency ratio is a particular concern for later life welfare where most public pension systems operate on a pay-as-you-go basis – that is, current pensions are financed through tax contributions from current workers (Jones, Geilenkeuser, Helbrecht, & Quilgars, Citation2012). Notwithstanding the flaws in a measure which assumes everyone of working age is productive and everyone over working age is dependent (Walker, Citation2012), in many nations the ratio is predicted to fall to fewer than two working-age people to every older person (OECD, Citation2014). Even with the move towards increased retirement age, the ratio of retired to working population will still rise. Increasing numbers of older people, notably among the oldest old, will add to welfare demands and their longevity will increase the length of time any one person will call upon health and care services. The Office for Budget Responsibility (Citation2011) in the UK estimates that the additional health, state pension and social care of this demographic shift will cost an extra 5.4% of the UK's current GDP (£80 billion). Others predict that public expenditure on long-term care will grow by over 300% in real terms between 2005 and 2041 (Gheera, Citation2010).

The ‘dangers’ of an ageing population are not new (Phillipson, Citation2000, p. 293). The generational conflict between workers and pensioners has remained on the political agenda since the 1930s (Phillipson,Citation2000). What has changed in recent years is the shift in political rhetoric away from equality towards the issue of equity; older people have moved from being poor and deserving to being the hoarders of societies’ wealth and welfare (e.g. Livsey & Price, Citation2013; Walker, Citation2012), and in the interests of what is ‘right’ and ‘fair’ they should now be giving something back to the younger generations (Willetts, Citation2010). A powerful narrative has developed which argues against the unsustainability of current welfare expenditure in the face of the immediate need to address an unprecedented budget deficit and the longer term levels of welfare provision for pensioners (Helm, Citation2011). Faced with the option of either increasing contributions from those who are working, or paying out less to those who are retired, policy initiatives are increasingly looking towards individuals to use the wealth they have accumulated over the life course to fund their welfare needs. Although later life welfare includes a range of financial challenges, we focus on one aspect that is pertinent to the international study of housing; the use of housing asset wealth to fund later life care.

Housing wealth is becoming a potentially more significant source of individual welfare across the life course. Governments in Western welfare states are attempting to restructure expectations of citizens that their current and future welfare needs should be self-funded and are pursuing policies which aim to promote such behaviour (Appleyard, Citation2012). Consequently, the substantial wealth held by many older people in housing stock is increasingly entering policy debates as governments probe how these assets can be liquidised to increase private contributions to the costs of the care system (Fernandez & Forder, Citation2010).

Whilst housing- and asset-based welfare generally have been seen as a compliment to the existing state provision (Sherraden, Citation2002), paying for residential care represents a new departure where the use of housing wealth could become compulsory. This paper critically explores the positioning of housing asset-based welfare as a potential compulsory solution to the fiscal pressures of meeting care costs in later life. In particular, it asks: What are the implications for inter- and intra-generational inequality?

There are long and interesting debates to be had about defining or even the existence of ‘a generation’ (inter alia, Kertzer, Citation1983; Phillipson, Citation2000) that we do not have the space to enter into here. However, as Phillipson (Citation2000) acknowledges, the study of generations in and of itself is as much about differences within them as it is between them. This simultaneous consideration is at the heart of our discussion. It is the combination of the new political rhetoric framed around issues of equity between generations, when considered in tandem with the long-standing inequalities within them, which underpin issues of intra- and inter-generational justice and form the basis for arguments for and against housing asset-based welfare.

In debating both within (intra-) and between (inter-) generational differences, we embrace the complex entanglement of ‘equity’ and ‘equality’. The argument for the use of housing asset-based welfare is built on the issue of equity; in that it is fair or just that those with the means pay for their welfare and do not pass the burden on to others less well off, particularly the younger, tax-paying generation. In the argument against, the issue becomes more focussed on equality; not all older people have, or will have, sufficient housing wealth nor the means to access it, in order to cover the costs of their care and welfare.

In the following sections we consider how evidence can inform debates about the policy implications of housing- and asset-based welfare. First, we provide a brief outline of the emergence of asset-based welfare. Taking an intra- and inter-generational justice perspective, we then discuss the case for developing a housing-based welfare system, before considering the case against. Although our focus is the UK, the issues raised are relevant to nations seeking to support elderly populations without penalising future generations of older people.

The emergence of the housing asset-based welfare model

The UK and many other countries do not have a sustainable system for paying for long-term care. Nations are facing similar challenges to funding systems and contain elements of private insurance, universality and means testing to varying degrees (see Forder & Fernandez, Citation2011; OECD, Citation2011, for reviews). At the heart of debates is the extent to which personal assets, particularly housing, will become the financial resource through which an ageing population funds their care. It is within this context, that housing wealth is being positioned as a central component of asset-based welfare in many nations (Doling & Ronald, Citation2010; Ong, Haffner, Wood, Jefferson, & Austen, Citation2013; Toussaint & Elsinga, Citation2009).

It is important to point out that the self-financing of elderly care through housing and other personal assets is not a new phenomenon. Local authorities in the UK have been able to require that people sell their homes to pay for residential care since 1948 (Gheera, Citation2010). More broadly, housing has existed as the ‘the hidden welfare state’ since the introduction of tax relief on mortgage interest in 1913 in the United States (Howard, Citation1997 cited in Béland, Citation2007, p. 96), while the role of housing as a welfare resource, particularly as a substitute or ‘trade-off’ for pensions, has been debated for some time (Castles, Citation1998; Dewilde & Raeymaeckers, Citation2008; Doling & Ronald, Citation2010; Kemeny, Citation1981). Asset-based welfare, in this sense, is not really a new idea in housing policy. However, whilst existing initiatives have positioned housing and other asset-wealth as complimentary to state provision, developments in policy for England demonstrate a move towards housing as a ‘legitimate target’ for policy interventions (Price & Livsey, Citation2013, p. 77) and the first step towards compulsory contribution towards long-term care costs.

The 2014 Care Act for England, which would come into effect in April 2016, is based on a series of recommendations made by the Dilnot Commission Report of 2011 (see Price & Livsey, Citation2013). Proposals include an individual cap (currently £72,000) on the cost of care. The proposed threshold at which individuals would have to start contributing will be set at around £118,000 worth of assets (savings and property) (Department of Health, Citation2014). Whilst the cap paves the way for new insurance products it is likely that those with highest risk of meeting care in later life will be least able to afford premiums, assuming that they will be insurable (Price & Livsey, Citation2013). For many older home-owners therefore covering the costs of care will inevitably mean tapping into their housing assets.

Despite its historical links to pensions and care provision, housing as a speculative investment was not initially explicitly associated with the concept of asset-based welfare. Sherraden's (Citation1991) seminal work in this area, traditionally focussed on savings schemes (Individual Development Accounts in the United States and the Child Trust Fund in the UK are key examples). His belief in an asset-effect, that owning assets changes attitudes and behaviour (Sherraden, Citation1991), has underpinned most asset-based welfare initiatives. However, as Searle and Köppe's (Citation2014) review of evidence shows most of this work has a theoretical base – how assets have the potential to improve people's lives, and the little evidence available shows that asset-based welfare generally benefits those who are already wealthy. Even Sherraden (Citation2002) acknowledges that inequalities remain an issue, and the shift towards asset-based welfare presents a major challenge where many remain excluded from asset accumulation and social protection. It is these inequalities that underpin issues of intra- and inter-generational justice and form the basis for arguments for and against asset-based welfare.

Housing asset-based welfare: the case for

Notwithstanding the current economic downturn, the quantities of personal wealth held in housing has increased dramatically over the past 40 years across many OECD nations (OECD, Citation2005, Citation2013). First, this is associated with significant increased levels of homeownership throughout the second half of the twentieth century (Andrews & Sánchez, Citation2011), making housing the most widely spread asset. In the 1970s, fewer than half of 60 year olds in England were owner-occupiers, by the 2000s this figure had risen to over three quarters (Bottazzi, Crossley, & Wakefield, Citation2012). The rise of owner-occupation among those aged 60 and over in particular points towards its potential as a welfare resource.

Second is the rise in real house price values (OECD, Citation2005, Citation2013). Those who bought into homeownership during the 1970s and 1980s have seen their assets increase dramatically in value. When adjusted for inflation, house prices in the UK, for example, have grown on average by 2.9% annually since 1975 (Appleyard & Rowlingson, Citation2010) and the average cost of property trebled from £54,547 to £167,294 between 1991 and 2013.Footnote2 The total net property wealth (property values minus mortgage liabilities and equity release) for all private home owning households in Great Britain is estimated at £3375 billion and the median net household property wealth at £148,000 (Office for National Statistics [ONS], Citation2011). Estimates of the value of housing equity held by older people in the UK range from £751 billion to £3 trillion (Housing LIN, Citation2012) and more than half of individuals aged 65 or over live in households with a total wealth of at least £300,000 (ONS, Citation2011). It is these substantial sums of (arguably unearned) wealth that some are suggesting should form the basis of the housing asset-based welfare model (Willetts, Citation2010).

When the increasing demands on government finances incurred through population ageing came up against the economic crisis of 2008, the potential for inter-generational conflict was raised as a major fault line in modern welfare states (Esping-Andersen, Citation2009). Whilst claims about inter-generational conflict are not novel and are perhaps overstated (Attias-Donfut & Arber, Citation2000), they do draw attention to the point that the so-called ‘baby boomer’ generation have enjoyed the ‘one-off bonanza’ of gains through homeownership, free tertiary education and a relatively generous welfare state and stable labour market which subsequent age cohorts will not directly benefit from as such circumstances are unlikely to ever be repeated (see Attias-Donfut, Ogg, & Wolff, Citation2005[Europe]; Forrest & Izuhara, Citation2009[East Asia]; Olsberg & Winters, Citation2005[Australia]; Willetts, Citation2010[UK]). This context underpins arguments for housing asset-based welfare.

Wealth is much more unevenly distributed than income and as housing assets constitute a large proportion of household wealth, they are a major component of inequality (Hills et al., Citation2010). A case could, therefore, be made for those who hold considerable housing wealth to be encouraged to use this for their welfare in older age rather than these costs being met by dwindling state budgets, or further contributions from a shrinking working generation. Another argument is for housing wealth to be redistributed (through taxation) to those who face more uncertain labour markets, reduced levels of state provision of welfare and higher barriers to homeownership.

As noted above, a large part of the population aged 65 and over own housing assets. Some of whom will have homes worth considerably more than when originally purchased. Earned forms of wealth, such as wages, are subject to taxes in the name of redistributive justice. The same principle could be applied to arguably ‘unearned’ income through measures such as the taxation of household wealth and inheritance or means testing of care. Such a policy would be in the interest of fairness in tackling intra-generational inequality. Housing is an important source of division between young people who are part of asset-rich families and those with fewer resources at their disposal. Inter-generational transfers of housing assets through inheritance and lifetime gifts are important means through which wealth inequality is entrenched over time. For example, in the UK, residential buildings accounted for 41% of the value of estates passing at death in 2001/02, by 2009/10 it was 48%, and the average amount of housing wealth per estate ranged from £83,282 to £1.3 m.Footnote3 Those who are already affluent are most likely to inherit and bequeath substantial amounts (Rowlingson & McKay, Citation2005) and benefit from earlier transfers of family wealth (Kohli, Citation1999). Research shows equity release among those financially better off is more likely to be used to facilitate the early transfer of housing wealth to the younger generation than those who are less well off (Overton, Citation2010), reinforcing inter-generational inequalities. Ensuring that those with sufficient assets use them to provide for their own welfare, could be a step towards disrupting the long-standing structures which perpetuate inequalities, associated with the transfer of wealth and advantage across generations.

These steps would be innovative since wealth, despite being the main source of inequality, has been a hitherto neglected element of distributive justice (Buchanan, Citation2009). Politicians have largely shied away from wealth redistribution policies. On a practical level they may be deemed more difficult to carry out than income redistribution through fiscal policy, but it should also be conceded that significant political, and public, opposition may render the actualisation of these measures difficult.Footnote4

Taxation of housing wealth, or the potential to accumulate it, is currently limited to measures such as capital gains tax, council tax, stamp duty and inheritance tax. Yet this might be expected to change as the substantial equity stored in housing becomes recognised as one of a limited range of solutions to the costs of population ageing, the need to increase tax revenues, and as a form of wealth redistribution.Footnote5 In summary, by adopting a rhetoric of equity or fairness, housing asset-based welfare has been presented as a means of addressing both the fiscal costs of population ageing and also as a way of challenging inter- and intra-generational inequality. The paper now turns to explore issues of inequality directly, and in so doing it raises some of the potential limitations of the housing-based welfare paradigm.

Housing asset-based welfare: the case against

As recognised by Sherraden (Citation2002) the inequalities in society present a serious limitation of asset-based welfare. Not only is asset wealth distributed unevenly across a range of structural divisions, but there are many people who remain excluded from asset accumulation. A further key limitation of housing asset-based welfare is that housing markets operate differently; regional inequalities in house prices are compounded by unequal growth rates over time. An asset welfare system based on housing would have inherently uneven social and spatial effects. Differences in value of property are also reflected in the inequalities in the amount of housing wealth that is available to households. The growth in access to, and value of, housing has created new inter- and intra-generational inequalities. Whilst some of this is reflective of a life-cycle effect such that the majority of wealth is accumulated over the age of 35, significant disparities exist within and between age groups.

For example, applying population weights to the sample of owner-occupiers from the UK Household Longitudinal SurveyFootnote6– Understanding Society – over £230 billion of housing wealth is concentrated among owners aged 50–64 in London (average £507,000), compared to £43 billion among the same age group in the North East of England (average £173,000). Among those aged 80 and over who may be expected to cash in their wealth, £45 billion is available to those in London (average £417,000), compared to £6.6 billion in the North East of England (average £131,000), £19 billion for the whole of Scotland (average £163,000), £15.9 billion in Wales (average £189,000) and £6.7 billion in Northern Ireland (average £198,000). Of course, these figures will inevitably mask sub-regional differences and will be reflective of the number of owners located within each region, but as the averages reported above and below shows the amount available per household varies both spatially and demographically.

Figure 1. Average housing wealth by age and UK region: 2010.

Source: Understanding Society and Labour Force Survey, author's analysis.

Analysis at the individual level shows the vast discrepancies in availability of housing wealth often hidden in average or aggregate statistics. Based on homeowners’ own accounts of the equity in their home (value of home minus any outstanding mortgage debt), Searle (Citation2013) shows the extreme range of the level of equity that owners of different ages have available, within the confines of data that set an upper limit of ‘£1 million or more’. The largest diversity is among 50–64 year olds – the age group commonly referred to as the ‘baby boomers’ who are deemed to have benefitted most from rising house prices (Willetts, Citation2010). For example, among this age group housing equity per household across the UK ranges from minus £280,000 (negative equity) to £1 million or more.Footnote7Amongst those aged 80 or over, who are most likely to need additional resources to pay for health care, household equity ranges from £10,000 to £1 million or more.Footnote8

Homeownership alone, therefore, is no guarantee of housing wealth, with many homeowners having very low or negative equity in their home. Such inequalities are not confined to the UK, but are relevant across many home owning nations. As a consequence, a significant proportion of the population would be disenfranchised from a housing-based model of welfare lacking sufficient housing equity to fund their welfare.

Of further concern are constraints on access to mortgage finance and homeownership (Stephens, Citation2007), creating a growing divide between ‘housing haves’ and ‘housing have-nots’ (Appleyard & Rowlingson, Citation2010). Across Europe, on average, around 30% of households live in a home that is rented (Eurostat, Citation2013). Thus, any moves towards an asset-based welfare system would exclude around a third of households. Across OECD nations, rental markets differ significantly. In nations where it tends to be those with limited access to financial resources who find homeownership least accessible and reside in rented accommodation, asset-based welfare models would further disadvantage these groups (Yates & Bradbury, Citation2010).

shows the unequal distribution of English households according to their housing wealth and incomes. Across all age groups the proportion of people without any equity reduces the further up the income scale they are. A fifth (22%) of all households have no equity and are located in the lowest two income quintiles. By contrast, those with housing wealth are more likely to have higher incomes. A third (32%) of all housing wealth in the UK is owned by households located in the top two income quintiles. Homeowners in the top 20% of the population, in respect of household income, have twice the housing equity as owners in the lowest 20%. Where housing and other welfare safety nets are being withdrawn, renting may be harbouring longer term welfare problems.

Figure 2. Housing equity by income and age groups (owners and renters): England 2011.

Source: English Housing Survey, author's analysis.

The model of asset-based welfare assumes homeowners have sufficient equity in their homes to cover their welfare needs. However, although house prices have risen, mortgage debt has grown even more rapidly, an issue noted across many OECD countries (Smith, Searle, & Powells, Citation2010). As the proportion of net household income required to service mortgage repayments has been on an upward trajectory, other resources which could provide for future welfare needs, such as saving and pensions contributions, have diminished (Doling & Ronald, Citation2010). Financial products developed and taken up due to the unaffordability of housing (such as interest-only mortgages) mean that some homeowners reach retirement age with levels of housing equity which are considerably lower than the value of their homes. The Financial Conduct Authority (Citation2013) in the UK reported that among 2.6 million people with interest-only loans due to mature in the next 30 years, nearly half are estimated to have insufficient funds set aside to pay off the mortgage, whilst 10% do not have any final repayment strategy.

A second issue is the growing trend in equity borrowing – where homeowners withdraw equity across the life course, before reaching retirement age (Klyuev & Mills, Citation2007; Schwartz, Hampton, Lewis, & Norman, Citation2006; Smith & Searle, Citation2008). Although this is not a phenomenon experienced across all home-owning nations (Toussaint & Elsinga, Citation2009), nevertheless it is estimated that home equity-based borrowing released $1.45 trillion in the United States between 2002 and 2006 (Mian & Sufi, Citation2009), £381 billion (in the UK) and A$373 billion (in Australia) between 2001 and 2008 (Wood, Parkinson, Searle, & Smith, Citation2013), leading to claims that housing wealth is being used routinely as an ATM (Klyuev & Mills, Citation2007) as well as funding some substantial ‘one-off’ or ‘sustained expenditures’ (Parkinson, Searle, Smith, Stokes, & Wood, Citation2009, p. 385). Equity withdrawal across the life course reduces the asset base available to homeowners to fund their welfare in older age. This new equity borrowing trend also counters the potential efficacy of the asset-based welfare model as the assets available to homeowners are greatly diminished by the time one reaches later life, with an increasing proportion of homeowners entering retirement with substantial outstanding mortgage debts (Appleyard & Rowlingson, Citation2010). This adds to the uncertainty of life expectancy and the difficulty in predicting how long any equity available in older age will have to last once accessed (Pensions Policy Institute, Citation2009).

The shift towards housing equity as the basis for welfare requires potentially competing policy measures for the ‘market excluded’ and the ‘market included’ (Doling & Ronald, Citation2010). On one hand, governments face pressure to maintain high house prices to protect the asset base of those who have already secured access to homeownership. On the other hand, there are calls from those without assets to make access to private welfare more affordable through lower house prices. Since homeowners outnumber those in other housing tenure types, the policy focus has been to stabilise or increase property values,Footnote9 reflecting the governments’ focus on house prices, creating the ‘feel good factor’ that drives general consumption in the economy (Forrest, Citation2008, p. 181). In this respect, short-term economic growth and political popularity are prioritised over a more sustainable and universal model of housing-based welfare.

From an inter-generational justice perspective, this raises the paradox of fairness. Accessing housing equity to fund an ageing society is deemed fairer than passing the burden on to younger taxpayers. However, asset-based welfare needs the value of housing to continue to rise at or above inflation in order to provide sufficient equity to fund later life care. The cost of care is then passed back down the generations in the form of high house prices; the next generation are paying the price by not being able to enter the market, or enter at a much higher income/house value ratio than their parents or grandparents.

Housing market volatility

The volatility of housing markets also strengthens the case against housing-based welfare, where the funds available at the time of withdrawal cannot be guaranteed. The slump in property values which both pre-empted and followed the financial crisis of 2007 (Mian & Sufi, Citation2009) showed how housing systems strongly influence and are influenced by the twists and turns of global financial systems and economies. This ‘glocalisation’ of finance (Martin, Citation2010, p. 587) restricts the ability of national governments to regulate or influence the erratic global capital flows which have such a significant bearing on the fortunes of housing markets within their borders (Clapham, Citation2005). This vulnerability to cyclical effects, and limited capacity of governments to counteract it, gives rise to concerns that a housing asset base may represent an unstable platform for a nation's welfare in older age; a crash in house prices greatly reduces the equity available to draw on.

This has been the experience in Singapore, where following the financial crisis in the late 1990s it became clear that retired owners had become too dependent on their homes as a pensions resource: ‘the East Asian economic downturn illustrated that when the wealth held in housing equity was needed most, its value was undermined by those very economic conditions’ (Ronald & Doling, Citation2012, p. 955). It was soon recognised ‘that other sources of income (than homeownership) better prevent poverty and enhance living conditions’ (ibid., p. 952). Subsequently, the post-Asian financial crisis period is marked by a notable shift away from encouragement into homeownership towards the development of social protection measures and alternative asset investment vehicles.

Barriers to realising housing wealth

Another drawback of housing asset-based welfare is the political and practical barriers to releasing housing wealth. State provision of welfare in older age commands widespread public support (Burkhardt, Martin, Mau, & Taylor-Gooby, Citation2011; Hills, Citation2007), whilst older people themselves make up a large share of the voting block that may resist government attempts to make older people fund their own welfare in later life (Doling, Citation2008). Steps to encourage asset-based welfare and withdraw aspects of state provision of support for older people, even in the name of inter-generational justice, would therefore be unpopular and difficult to enact. This may explain why successive governments in the UK and elsewhere have not taken measures to address the obvious unsustainability of current levels of provision in the face of population ageing.

The development of the equity release market varies across Europe and confidence in using products is equally varied across nations, with most owners envisioning only using a reverse mortgage as a last resort (Doling & Elsinga, Citation2013). Even in the UK, which dominates the European equity release market (Overton & Doling, Citation2010), evidence suggests older owners face multiple barriers to accessing their housing assets through equity release schemes (Jones et al., Citation2012; Terry & Gibson, Citation2006) or downsizing to a cheaper property (Angelini, Brugiavini, & Weber, Citation2011). The amount of equity realisable will also depend on the value of the property. Fox O’Mahony (Citation2013) demonstrates that in order for £75,000 to be released (the ‘lifetime cap’ on care costs deemed reasonable by the UK Government in 2012) £200,000 would need to be held in equity. As demonstrated earlier, this is well above the average amount of equity held by the majority of older people. For some, the low equity held in their homes means the financial gains may be outweighed by the costs, and hassle, of moving (Savilles, Citation2013).

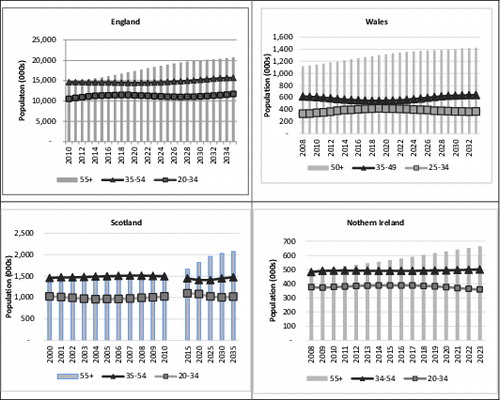

Another important, but under-researched barrier is the impact that demographic changes will have on the housing market and the potential for downsizing to access equity. Downsizing involves both sellers (in this case older owners) and buyers (younger generations). Given current population projections () this highlights two further constraints. First, the number of people in their 50s or older (those who will potentially look to downsize their property) is predicted to rise at a rate faster than those in middle age (35–54 years) (people potentially looking for larger family homes). Second, the downsizers will be competing for the same smaller properties as those entering the market (20–34 year olds) – and potentially with more buyer power and favourable outcomes (Norwood, Citation2013).

Figure 3. Population projections for UK (selected age groups).

Source: 2010-based Subnational Population Projections, Table 1 England and English Regions; General Registrars of Scotland; 2008-based population projections for the Spatial Plan areas of Wales; NISRA, 2008-based Sub-Northern Ireland Population Projections.

The ageing of societies is well noted, but the regional variations in population ageing are less well rehearsed. Searle (Citation2013) shows the changing population distributions within different regions of the UK.Footnote10 She notes two key trends that have implications in a broader international context. First, the regional differences in the rate of population increase. The rise in the number of people over 50 years old is evident in all regions, but the rate of this rise varies considerably. Second, there are a disproportionate number of people in each age group across regions. So areas which may experience similar rises in the numbers of older people may experience very different changes in the number of middle age and younger people. From the perspective of releasing equity through home moves, this raises concerns about whether older owners looking to sell larger family homes (and acquire suitable retirement housing) will be located in the places that younger owners are either located in or want to, and can afford to, move to; namely will buyers and sellers be in the ‘right’ locations at the right time?

From an inter-generational perspective, the demographic challenges around access to housing not only pose questions for older owners in accessing their equity, but also raise new ones in respect of inter-generational support and the future of asset-based welfare. Where welfare is increasingly dependent on private means, the uneven capacity to accumulate, retain and mobilise housing wealth within households and across generations has arguably become a key factor in determining life chances (Forrest, Citation2008). Whilst admittedly skewed in favour of relatively asset-rich families, inter-generational transfers of wealth from older people to their children are an important source of welfare for the latter group for large parts of their life course. For these familial safety nets to be maintained, it is important that homeowners can retain their assets in older age for their children's welfare. State coercion into utilising housing resources to fund welfare would diminish the ability of older people to financially support their children during key life course transitions. Similarly where young people are obtaining homes at a later stage in life than their parents did, means that they will have less time to accumulate housing assets to fund their own welfare in older age (Forrest & Hirayama, Citation2009). Although longevity may have a role where working life is prolonged and retirement age is delayed, as things stand, housing-based welfare may only be effective for the cohort currently moving towards old age. At best it is a short-term fix to the wider fiscal challenges of long-term demographic change. This is because future cohorts will face much tougher barriers to the accumulation of housing assets, resulting in less wealth for their welfare in later life.

Conclusions

Many countries are confronting the thorny dilemma of how to fund the welfare needs of a rapidly ageing population. Welfare states were conceived at a time of much lower life expectancies and people are now living longer post-retirement than ever before. It is perhaps inevitable, given the strain placed on the public provision of pensions, health care and other welfare services, that these additional costs are increasingly met through private means in the longer term. The argument presented here has been framed in the concept of generational justice in the UK context, although the same messages seem likely to apply in other countries too. Many homeowners have accumulated (mostly unearned) substantial wealth through housing market gains and it is perhaps unavoidable and just that they should draw on this wealth to provide for their welfare in later life.

However, whilst aggregate or average figures grab the headlines, and often politicians’ attention, this paper shows how this masks the extreme variability at the individual level. By offering a new narrative from an inter- and intra-generational perspective, we demonstrate that the issue is not simply one of equity – pitching one generation against another, but is a much more complex relationship between historical, political, economic and social contexts which create and perpetuate inequalities within as much as between generations.

Positioning housing assets as a welfare resource opens up a paradox of justice. Asset-based welfare relies on rising house prices in order for sufficient equity to be accumulated to cover care costs in later life. But, through higher house prices those costs will be passed down to those trying to enter this housing welfare system. Although younger generations are struggling to get on the housing ladder until later in life, potentially delaying the point at which they will start accumulating their housing assets, this may be counterbalanced by longer working lives as retirement age rises. However, there still remain uncertainties over how these demographic shifts will play out. As yet we do not know whether the entry and exit points will move along the life course in tandem.

Despite international evidence of the limitations of housing asset-based welfare, Western government responses still focus on private insurance rather than collective forms of protection. The expectation that individuals can assess their own risks and calculate their finances accordingly over their lifetime fails to acknowledge the risks of aligning personal welfare resources with the financial services industry (Price & Livsey, Citation2013) and the vulnerabilities of housing, labour and global financial markets (Searle & Köppe, Citation2014). The rhetoric of equity therefore raises further questions about political ideology as it does generational conflict, and social inequality.

A system needs to be developed which encourages and enables asset-rich homeowners to draw on their housing assets in a secure, efficient manner. However, this needs to run alongside and not be at the expense of a collective system which guarantees a minimum level of support for those lacking sufficient (and accessible) assets to fund their welfare in older age. Housing-based welfare could best serve as a complement, rather than alternative, to existing models of state provision. The responsibility and unenviable challenge for social and housing policy is to manoeuvre the bumpy road between socialising the long-term care risk and banking on private solutions. This involves inherently difficult and unpopular choices, yet the development of long-term solutions to the fiscal challenges of demographic change cannot be postponed for much longer.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Leverhulme Trust under Grant RP2011-IJ-024. The paper uses unit record data from Understanding Society. Understanding Society is an initiative by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) with scientific leadership by the Institute for Social and Economic Research, University of Essex and survey delivery by the National Centre for Social Research. Data are made available through the ESRC Data Archive. The findings and views reported in this paper are those of the authors. We are grateful for the comments from Duncan Maclennan and two anonymous referees on an earlier drafts of this paper.

This article was originally published with errors. This version has been amended. Please see Corrigendum (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14616718.2014.979620).

Notes

1. This is an issue for many OECD countries as reported in the ‘Ageing Population’ chapters of the OECD Fact Book series and the OECD Pensions at a Glance series among others (www.oecd-library.org).

2. Nationwide House Price Index.

3. National Archives of HM Revenue and Customers: Estates notified for probate, Table 12.4 for 2001/2 and 2009/10. Available at webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk.

4. The replacement of a property-based rates system by an individual ‘poll tax’ led to the most vociferous and violent protests that the UK had experienced and culminated in the resignation of the then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher (see http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/magazine/8593158.stm). Inheritance tax is one of the most unpopular in the UK. Despite its limited impact – it was only levied on 3% of estates upon death in 2009/10 – half the population of the UK think it should be abolished (Hedges & Bromley, Citation2001 cited in Mirlees et al., Citation2011, p. 358).

5. The Scottish Government approved a reform of Stamp Duty as part of The Land and Building Transactions Tax (Scotland) Bill which will come into effect in April 2015. The new system will move from a ‘slab’ to a ‘proportional’ system with additional tax payable on the amount that exceeds the next threshold, rather than on the full value of the property. The new system will potentially reduce the tax payable on lower-cost homes, but increase it across above-average-priced properties. The new system is proving popular within the property industry with calls for the reform to be extended to the rest of the UK (Moore, Citation2013).

6. Based on population weights from the Labour Force Survey applied to the Understanding Society sample of 15,310 households who own their home outright or are buying their home with a mortgage. Age is based on oldest owner-occupier in household.

7. Variations are also evident across Wales (£55,000–£750,000), Scotland (£80,000–£1 million or more) and Northern Ireland (£120,000–£800,000) (Searle, Citation2013).

8. Variations are also evident across Wales (£40,000–£600,000), Scotland (£45,000–£500,000) and Northern Ireland (£10,000–£650,000) (Searle, Citation2013).

9. Although this may not be a vote-winning strategy. A recent poll conducted in Great Britain, for instance, showed that 66% of adults would prefer to see house prices remain stable or fall (Shelter, Citation2013).

10. Figures for Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland are available in the Searle (Citation2013) appendix.

References

- Andrews, D., & Sánchez, A.C. (2011). The evolution of homeownership rates in selected OECD countries: Demographic and public policy influences. OECD Journal: Economic Studies, 8(1), 1–37.

- Angelini, V., Brugiavini, A., & Weber, G. (2011). Does downsizing of housing equity alleviate financial distress in old age? In A. Borsch-Supan, M. Brandt, & M. Schroder (Eds.), The individual and the welfare state (pp. 93–101). London: Springer.

- Appleyard, L. (2012). Household finance under pressure: What is the role of social policy? Social Policy and Society, 11(1), 131–140.

- Appleyard, L., & Rowlingson, K. (2010). ShipHome owner and the distribution of personal wealth. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Attias-Donfut, C., & Arber, S. (2000). Equity and solidarity across the generations. In C. Attias-Donfut & S. Arber (Eds.), The Myth of generational conflict, the family and state in ageing societies (pp. 1–21). London: Routledge.

- Attias-Donfut, C., Ogg, J., & Wolff, F.-C. (2005). European patterns of intergenerational financial and time transfers. European Journal of Ageing, 2(3), 161–173.

- Bottazzi, R., Crossley, T.F., & Wakefield, M. (2012). Late starters of excluded generations? A cohort analysis of catch up in home ownership in England (IFS Working Paper W12/10). London: Institute For Fiscal Studies.

- Buchanan, N.H. (2009). What do we owe future generations? The George Washington Law Review, 77(5/6), 1237–1297.

- Burkhardt, C., Martin, R., Mau, S., & Taylor-Gooby, P. (2011). Differing notions of social welfare? Britain and Germany compared. In J. Clasen (Ed.), Converging worlds of welfare? British and German social policy in the 21st century (pp. 15–32). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Castles, F.G. (1998). Comparative public policy: Patterns of post-war transformation. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Clapham, D. (2005, April 6–8). What future for housing policy? Paper presented at Housing Studies Association Annual Conference, University of York, York, United Kingdom.

- Department of Health. (2014). Factsheet 6: Care and support funding reforms. London: Department of Health. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-care-bill-factsheets. Accessed August 1 2014.

- Dewilde, C., & Raeymaeckers, P. (2008). The trade-off between home-ownership and pensions: Individual and institutional determinants of old-age poverty. Ageing and Society, 28, 805–830.

- Doling, J. (2008). Housing and demographic change. Paper given to the ENHR Workshop on Home Ownership and Globalisation at the OTB Research Institute for Housing, Planning and Mobility Studies, Delft University of Technology., Delft, The Netherlands.

- Doling, J., & Elsinga, M. (2013). Demographic change and housing wealth: Homeowners, pensions and asset-based welfare in Europe. New York, NY: Springer.

- Doling, J., & Ronald, R. (2010). Home-ownership and asset-based welfare. Journal of Housing and Built Environment, 25(2), 165–173.

- Esping-Andersen, G. (2009). The incomplete revolution: Adapting to women's new roles. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Eurostat. (2013). Statistics explained: Housing statistics. Retrieved from http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/statistics_explained/index.php/Housing_statistics#Tenure_status. Accessed 2 April 2014.

- Fernandez, J., & Forder, J. (2010). Equity, efficiency, and financial risk of alternative arrangements for funding long-term care systems in an ageing society. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 26(4), 713–733.

- Financial Conduct Authority. (2013). The FCA publishes findings of reviews into interest-only mortgages and reaches agreement with lenders to contact interest-only borrowers. Retrieved from http://www.fca.org.uk/news/interest-only-mortgages. Accessed 30 July 2013

- Forder, J., & Fernandez, J. (2011). What works abroad? Evaluating the funding of long-term care: International perspectives (PSSRU Discussion Paper 2794). Retrieved from http://www.pssru.ac.uk/pdf/dp2794.pdf. Accessed 13 June 2013.

- Forrest, R. (2008). Globalisation of the housing asset rich. Global Social Policy, 8(2), 167–187.

- Forrest, R., & Hirayama, Y. (2009). The uneven impact of neoliberalism on housing opportunities. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 33(4), 998–1013.

- Forrest, R., & Izuhara, M. (2009). Exploring the demographic location of housing wealth in East Asia. Journal of Asian Public Policy, 2(2), 209–221.

- Fox O’Mahony, L. (2013). Paying for care: What matters is how you get there. Retrieved from http://wealthgap.wp.st-andrews.ac.uk/paying-for-care/. Accessed 30 July 2013.

- Gheera, M. (2010). Funding social care. London: House of Commons Library Research.

- Hedges, A., & Bromley, C. (2001). Public attitudes towards taxation: The report of research conducted for the Fabian commission on taxation and citizenship. London: Fabian Society. Cited in Mirless, J., Adams, S., Besley, T., Blundell, R., Bond S, Chote R … Poterba, J. (2011). Mirless review: Tax by design. London: Institute for Fiscal Studies. Retrieved from http://www.ifs.org.uk/mirrleesReview/ design. Accessed 21 October 2011.

- Helm, D. (2011). The sustainable borders of the state. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 27(4), 517–535.

- Hills, J. (2007). Pensions, public opinion and policy. In J. Hills, J. Le Grand, & D. Piachaud (Eds.), Making social policy work. CASE studies on poverty, place and policy (pp. 221–243). Bristol: The Policy Press.

- Hills, J., Brewer, M., Jenkins, S., Lister, R., Lupton, R., Machin, S. … Riddell, S. (2010). An anatomy of economic inequality in the UK: Report of the national equality panel, CASEreport60. London: London School of Economics.

- Housing LIN. (2012). Strategic housing for older people. London: Housing Learning and Improvement Network.

- Howard, C. (1997). The hidden welfare state: Tax expenditures and social policy in the United States, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Cited in Béland, D. (2007). Neo-liberalism and social policy: The politics of ownership. Policy Studies, 28(2), 91–107.

- Jones, A., Geilenkeuser, T., Helbrecht, I., & Quilgars, D. (2012). Demographic change and retirement planning: comparing household's views on the role of housing equity in Germany and the UK. International Journal of Housing Policy, 12(1), 27–45.

- Kemeny, J. (1981). The Myth of home ownership: Public versus private choices in housing tenure. London: Routledge.

- Kertzer, D. (1983). Generation as a sociological problem. Annual Review of Sociology, 9, 125–149.

- Klyuev, V., & Mills, P. (2007). Is housing wealth an “ATM”? the relationship between household wealth, home equity withdrawal and saving rates. IMF Staff Papers, 54(3), 539–561.

- Kohli, M. (1999). Private and public transfers between generations: Linking the family and the state. European Societies, 1(1), 81–104.

- Livsey, L., & Price, D. (2013). Old problems and new housing conflicts. Paper presented at the Housing Studies Association Annual Conference, University of York. York, United Kingdom.

- Martin, R. (2010). The local geographies of the financial crisis: from the housing bubble to economic recession and beyond. Journal of Economic Geography, 11, 587–618.

- Mian, A., & Sufi, A. (2009). House prices, home equity-based borrowing and the US household leverage crisis (NBER Working Paper]). Retrieved September 21, 2010 from http://ssm:com/abstract=1397607.

- Moore, E. (2013, June 28). Scotland blazes stamp duty reform trail. Financial Times. Retrieved July 23, 2013 from http://www.ft.com.

- Norwood, G. (2013, July 14). Older homeowners accused of muscling in on first-time buyers. The Observer. Retrieved July 22, 2013 from http://www.guardian.co.uk/money/2013/jul/14/olde4r-homeowners-first-time-buyers.

- Office for Budget Responsibility. (2011). Fiscal sustainability report. Retrieved June 1, 2012 from http://budgetresponsibility.independent.gov.uk/fiscal-sustainability-report-july-2011.

- Office for National Statistics. (2011). Wealth in Great Britain: Main results from the wealth and assets survey: 2008/10. Newport: Author.

- Olsberg, D., & Winters, M. (2005). Ageing in place: Intergenerational and intrafamilial housing transfers and shifts in later life (Final Report Number 88). Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute.

- Ong, R. Haffner, M. Wood, G. Jefferson, T., & Austen, S. (2013). Assets, debt and the drawdown of housing equity by an ageing population (AHURI Positioning Papers No 153). Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2005). Economic outlook 78. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2011). Help wanted? pProviding and paying for long-term care. Retrieved June 13, 2013 from http://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/helpwantedprovidingandpayingforlong-termcare.htm#to_obtain.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2013). Economics: Key tables from OECD. 17. House Prices. Retrieved April 2, 2014 from http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/house-prices_2074384x-table17.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2014). Society at a glance. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Overton, L. (2010). Housing and finance in later life: A study of UK equity release customers. A report for Age UK. Retrieved July 10, 2012 from http://www.ageuk.org.uk/documents/en-gb/for-professionals/consumer-issues/id9116_housing_and_finance_in_later_life_a_ study_of_uk_equity_release_customers_2010_pro.pdf?dtrk=true.

- Overton, L., & Doling, J. (2010). The market in reverse mortgages: Who uses them and for what reason? Hypostat 2009. Brussels: European Mortgage Federation. Cited in Doling, J., and Elsinga, M. (2013). Demographic change and housing wealth: Homeowners, pensions and asset-based welfare in Europe. New York, NY: Springer

- Parkinson, S., Searle, B., Smith, S., Stokes, A., & Wood, G. (2009). Mortgage equity withdrawal and Australia and Britain: Towards a wealth-fare state? European Journal of Housing Policy, 9(4), 363–387.

- Pensions Policy Institute. (2009). Retirement Income and assets: How can housing support retirement? (discussion paper by John Adams and Sean James, Pensions Policy Institute). London: London Author.

- Phillipson, C. (2000). Intergenerational conflict and the welfare state: American and British perspectives. In C. Pierson & F.G. Castle (Eds.), The welfare state reader (pp. 293–307). Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Price, D., & Livsey, L. (2013). Financing later life: Pensions, care, housing equity and the new politics of old age. In G. Ramia, K. Farnworth, & Z. Irving (Eds.), Social policy review 25: Analysis and debate in social policy, vol. 25 (pp. 67–88). Bristol: The Policy Press.

- Ronald, R., & Doling, J. (2012). Testing home ownership as the cornerstone of welfare: Lessons from East Asia for the West. Housing Studies, 27(7), 940–961.

- Rowlingson, K., & McKay, S. (2005). Attitudes to inheritance in Britain. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Savilles (2013). Family values: What the genealogy of the housing market means to different buyer types, residential property focus Q1 2013. London: Savills UK Research. Retrieved July 26, 2013 from http://pdf.euor.savills.co.uk/residential–-other/rpf-q113-lr.pdf.

- Schwartz, C., Hampton, T., Lewis, C., & Norman, D. (2006). A survey of housing equity withdrawal and injection in Australia (Research Discussion Paper 2006-08). Sydney: Reserve Bank of Australia.

- Searle, B.A. (2013). Who owns all the housing wealth? (Patterns of Inequality in England, Mind the Housing Wealth Gap: Briefings, No 3, June 2013). Retrieved October 25, 2013 from http://wealthgap.wp.st-andrews.ac.uk/publications/.

- Searle, B.A., & Köppe, S. (2014). Assets, savings and wealth, and poverty: A review of evidence. Final report to the Joseph Rowntree Foundation. Bristol: Personal Finance Research Centre.

- Shelter. (2013). At any cost? The case for stable house prices in England. London: Author.

- Sherraden, M. (1991). Assets and the poor: A new American welfare policy. New York, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

- Sherraden, M. (2002). Assets and the social investment state. In W. Paxton (Ed.), Equal shares? Building a progressive and coherent asset-based welfare policy (pp. 28–41). London: IPPR.

- Smith, S.J., & Searle, B.A. (2008). Dematerialising money: The ebb and flow of wealth between housing and other things. Housing Studies, 23(1), 21–43.

- Smith, S.J., Searle, B.A., & Powells, G.D. (2010). Introduction. In S.J. Smith & B.A. Searle (Eds.), The Blackwell companion to the economics of housing: The housing wealth of nations (pp. 1–28). Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Stephens, M. (2007). Mortgage market deregulation and its consequences. Housing Studies, 22(2), 201–220.

- Terry, R., & Gibson, R. (2006). Obstacles to equity release. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Toussaint, J., & Elsinga, M. (2009). Exploring ‘Housing Asset-Based Welfare’, can the UK be held up as an example for Europe? Housing Studies, 24(5), 669–692.

- Walker, A. (2012). The new ageism. The Political Quarterly, 83(4), 812–819.

- Willetts, D. (2010). The pinch: How the baby boomers took their children's future – and why they should give it back. London: Atlantic.

- Wood, G., Parkinson, S., Searle, B., & Smith, S. (2013). Motivations for equity borrowing: A welfare-switching effect. Urban Studies, 7, 1–20.

- Yates, J., & Bradbury, B. (2010). Home ownership as a (crumbling) fourth pillar of social insurance in Australia. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 25, 193–211.