ABSTRACT

We investigated whether attachment quality is related to infant–mother dyadic patterns in monitoring animated social situations. Sixty 12-month-old infants and their mothers participated in an eye-tracking study in which they watched abstractly depicted distress interactions involving the separation of a “baby” and a “parent” character followed by reunion or further separation of the two characters. We measured infants’ and their mothers’ relative fixation duration to the two characters in the animations. We found that infant attachment disorganization moderated the correspondence between the monitoring patterns of infant–mother dyads during the final part of the animations resulting in reunion or separation. Organized infants and their mothers showed complementary monitoring patterns: the more the mothers focused their attention on the “baby” character, the more the infants focused their attention on the “parent” character, and vice versa. Disorganized infant–mother dyads showed the opposite pattern although the correlation was nonsignificant: mothers and their infants focused on the same character. The attachment-related differences in the nature of the synchrony in the attentional processes of infants and their mothers suggest that by 12 months the dyads’ representations of social situations reflect their shared social–emotional experiences.

Introduction

Recent studies already provide evidence for the formation of attachment-related social information processing biases in infancy (Biro, Alink, Huffmeijer, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Van IJzendoorn, Citation2015; Johnson, Dweck, & Chen, Citation2007; Johnson et al., Citation2010; Peltola, Forssman, Puura, Van IJzendoorn, & Leppänen, Citation2015). Using the violation of expectation method, Johnson and her colleagues (Citation2007) showed that only securely attached 12-month-old infants looked longer at animations depicting unresponsive caregiving behavior compared to responsive caregiving behavior, indicating that they did not expect the former. In a previous study (Biro et al., Citation2015), we demonstrated that attachment security is associated with 12-month-old infants’ monitoring patterns during the observation of a separation animation of a parent and baby figure. Secure and insecure infants showed different strategies in their attentional allocation, namely, secure infants focused more on the parent figure compared to insecure infants. This finding suggests that securely attached infants, based on the interactions with their own caregivers, regard the availability of a caregiver figure as more relevant in a separation situation or have stronger expectations of a response from the caregiver figure. These biases in attentional processes for social information might be markers of infants’ developing internal working models (IWMs), which are assumed to be the consequence of the differences in the quality of early attachment relationships (Bowlby, Citation1969; Bretherton & Munholland, Citation2008; Dykas & Cassidy, Citation2011; Waters & Waters, Citation2006). In the current study, we aim to investigate whether attachment quality is related to specific infant–caregiver dyadic patterns during observation of social interaction.

Caregiver–infant interactions have been extensively discussed with respect to the concept of synchrony, which describes a wide variety of coordinated behaviors including gaze, affect, vocalization, attention, actions, and also physiological processes (e.g. Feldman, Citation2007a; Feldman, Magori-Cohen, Galili, Singer, & Louzoun, Citation2011). Synchrony builds on the growing familiarity with each other and involves adaptation to each other’s rhythms. Synchronous behaviors include not only cooccurrences of specific behaviors but also reciprocal and complementary dyad-specific behavioral configurations. Caregiver–infant interactions are seen as a dynamic system that the infant can influence as well (Tronick, Citation1989). Synchrony can serve various functions at many levels including organizing and regulating behavioral and hormonal responses, for example to stressful events, and influencing maturation processes of the brain from early on (see review by Leclère et al., Citation2014). It is generally assumed that synchrony plays a critical role in preparing the infant to coordinate complex social acts and in shaping social, cognitive, and emotional development over time. Dysregulation in caregiver–child interactions has indeed been linked to maladjustment (Harrist, Pettit, Dodge, & Bates, Citation1994), development of problem behavior (García-Sellers & Church, Citation2000), and lower capacity for empathy (Feldman, Citation2007b). Importantly, several studies have found associations between interactional synchrony and attachment in infants (De Wolff & Van IJzendoorn, Citation1997; Isabella, Belsky, & Von Eye, Citation1989; Jaffe, Beebe, Feldstein, Crown, & Jasnow, Citation2001; Lundy, Citation2002, Citation2003), with a higher frequency of interactional synchrony being related to attachment security. In a preschool study including not only attachment security but also attachment disorganization, attachment disorganization was linked to the lowest levels of synchrony (Bureau et al., Citation2014).

Furthermore, microanalytic studies of mother–infant communication also point to the importance of mutual regulation and reciprocity between infants and caregivers and further refine the specific content and process of the interaction patterns in relation to attachment relationship (e.g. Beebe & Steele, Citation2013). By analyzing face-to-face interactions on a moment-to-moment basis in infants as young as 4 months of age, several studies showed that both security and disorganization can be predicted by specific patterns in the contingencies and coordination within different modalities such as maternal stimulation, facial responsivity, social engagement, self-regulation, and vocal coordination (Braungart-Rieker, Garwood, Powers, & Wang, Citation2001; Jaffe et al., Citation2001; Malatesta, Culver, Tesman, & Shepard, Citation1989; Tronick, Citation1989; see also review by Beebe & Steele, 2013).

Synchrony research and the microanalytic approach have so far been restricted mainly to studying levels of synchrony and contingencies, while caregivers and infants are engaged in an interaction with each other. However, both attachment theory and the concept of synchrony together with the microanalytic approach emphasize the internalization of specific interactional patterns between the caregiver and the infant in the form of IWMs, and the central role of IWMs in social-cognitive processes outside the realm of direct caregiver–infant interaction (Beebe & Steele, Citation2013; Bowlby, Citation1969; Dykas & Cassidy, Citation2011). We, therefore, examined dyadic patterns of infants’ and their caregivers’ attentional and cognitive processing of animated attachment-related interactions.

To investigate these patterns, we tested the correspondence between the monitoring strategies of infants and their caregivers while they observed animations involving social interactions. Infants and their mothers separately participated in an eye-tracking session during which a series of identical animations were presented (the animations were adopted from the study of Johnson et al., Citation2007). The animations involved two abstract figures, representing a “parent” and a “baby”, who were separated from each other. The “baby” figure starts to cry or laugh upon separation which is followed by the “parent” figure’s return or departure. We recorded infants’ and mothers’ eye movements and used their attentional allocation (relative fixation duration) for the two figures during the separation and response parts of the animations as the measure of monitoring strategy. As this measure provides insight into the attentional processes of the observer in terms of the relative salience or importance of the interacting figures, it allows us to tap into the nature of internalized representations of parent–child social interactions. Here, we focus on animations depicting the distress separation situation (i.e. in which the “baby” figure cries) as this situation is most likely to elicit attachment-related representations and biases.

We hypothesized that attachment moderates the relation between the monitoring patterns of the infant and the mother. We expected stronger correspondence between infants’ and their mothers’ monitoring strategies in secure compared to insecure infant–parent dyads and in organized compared to disorganized infant–parent dyads. Since secure infant–mother dyads display frequent synchronous interactions (e.g. Lundy, Citation2003), often showing optimal levels of interactional contingencies (Beebe & Steele, Citation2013), and mothers of secure infants have been found to show responsive, sensitive, and consistent care (De Wolff & Van IJzendoorn, Citation1997; Verhage et al., Citation2016), it is expected that cognitive representations or IWMs of mothers and infants with secure relationships are likely to become “attuned” by the end of the first year. This could lead to a stronger correspondence in their biases of attentional processes for animated separation and reunion interactions. Insecure infants experience less or less optimal level of synchrony and often have less sensitive and responsive mothers. Social-cognitive biases of mothers and their insecure infants might thus involve more “mismatches”. Disorganization is characterized by (momentary) breakdowns in attachment strategy, with the infant displaying, for example, contradictory behaviors supposedly triggered by frightening or frightened parental behavior (Main & Hesse, Citation1990; Schuengel, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Van IJzendoorn, Citation1999). Together with the evidence that there are unique disturbances in the microanalysis of infant–mother contingent and reciprocal communication (Beebe et al., Citation2010; Beebe & Steele, Citation2013) and that interactional synchrony is lower in disorganized than in organized children (Bureau et al., Citation2014), we expected that the monitoring strategies of disorganized infants show lower correspondence with those of their caregivers. Due to the relatively small sample size, we primary rely on continuous attachment variables in the main analysis and will not test the difference between organized secure and insecure dyads. Control variables of age and education level of the mother were also included in the analyses to test if they influence the presence and strength of the moderation as these variables have previously been shown to be relevant in attachment research (e.g. Bakermans-Kranenburg, Van IJzendoorn, & Kroonenberg, Citation2004).

Method

Participants

Sixty mothers participated with their 12-month-old infants (26 boys and 34 girls). Infants were all healthy, full term and their mean age was 375.63 days (SD = 9.29 days, range = 354–396 days). The mothers’ mean age was 34 years (SD = 4.48 years; range = 24–53 years). The mothers were all the biological mothers of the infants except for one who was a foster mother who had by far the highest age. In 89% of the families, both parents had the Dutch nationality, and in the remaining families one of the parents had a European (non-Dutch; 7%), South American (2%), or African (2%) nationality. Using a five-point scale for education level (1: primary school, 2: vocational school, 3: secondary school, 4: postsecondary applied education, 5: university degree), the mean education level of the mothers was 4.14 (SD = 0.84, range: 1–5), which indicates a relatively highly educated sample. Families were recruited through direct mail, their addresses were provided by the city council.

Two mothers and five infants were excluded from the sample because they did not provide usable eye-tracking data (see “Data analysis” section). This resulted in 53 mother–infant dyads with available data in our analyses. The excluded infant–mother dyads did not differ from the included dyads in infant gender, mothers’ age and education, or quality of the attachment relationship, ps > .14.

Procedure

The lab visit started with the eye-tracking experiment for the infant, which lasted about 5 min. This was followed by the Strange Situation Procedure (SSP) that took place in a different lab room. We continued the lab visit with other observational measures lasting about an hour, which are not part of the current paper (see Biro et al., Citation2015). Finally, the eye-tracking experiment was conducted with the mothers. Infants received a gift and the mothers had their travel expenses reimbursed. The study was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the Institute of Child and Education Studies of Leiden University. Caregivers signed informed consent forms before participation.

Measures: eye-tracker paradigm/animations

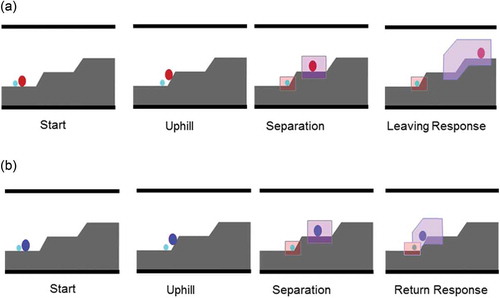

Stimuli. Infants and mothers were presented with eight animations (34.5 x 25.5 cm with a resolution of 1270 by 924 pixels) involving two abstract figures: a larger oval shape “parent” (3.5 x 2.5 cm) and a smaller oval shape “baby” (2x1.5 cm), see (see also Biro, Alink, Van IJzendoorn, & Bakermans-Kranenburg, Citation2014 for more details). Each animation started with the figures first moving together (Start segment, 2.6 s). This was followed by the “parent” figure moving up a hill and stopping on the plateau while the “baby” figure was trying to go uphill but slipped back (Uphill segment, 2.1 s). Upon separation, the sound of a crying baby was played in half of the movies while the sound of a laughing baby was played in the other half (Separation segment, 11.0 s). When the sound started, the “baby” figure expanded slightly (2 mm) and contracted three times together with a slight change in color (lasting 2.8 s), giving the impression that it was the source of the sound. During the rest of the Separation segment, the figures did not move. Following separation, in half of the movies (both for movies including cry and laughter sounds), the “parent” figure moved down the hill and ended up next to the “baby” figure (Return Response segment, 4.3 s), while in the other half of the movies the “parent” figure moved further up a second hill and stayed on top of it (Leaving Response segment, 4.3 s). The sounds of crying or laughter faded away during the last 2 s. The color of the “parent” figure in the animations with the returning response was different from the one with the leaving response (blue vs. red), and counterbalanced across participants. The color of the “baby” figure was always light blue.

Figure 1. Frames from the Start, Uphill, Separation, Leaving Response (a) and Return Response segments (b) of the animation. Areas of interests (AOIs) for the two figures during the Separation and Response segments are shown (not visible during the presentation).

There were four order conditions to which the infants were randomly assigned. Mothers received the same order condition as their infants. Two cry and two laughter movies were alternating, starting with either one or the other emotional type. In addition, the “parent” figure’s response type alternated between every movie: the first four movies started with either Return or Leaving, and in the second four movies the response type alternated in the opposite order. In the current study, we only focused on animations with cry sounds.

Recording eye-movements

The eye-movement patterns of infants and mothers were recorded by a Tobii T120x eye-tracker (Tobii technology AB, Stockholm, Sweden). During the infant experiment, infants sat on their mothers’ laps in a curtained booth facing the 17” thin-film transistor monitor with the integrated eye-tracker. The height of the chair and the position of the monitor were adjusted to establish a good eye-tracking position (with eyes 60 cm away from the monitor). Using Tobii Studio software, first a five-point infant calibration procedure was carried out. The presentation of the animations immediately followed the calibration. One of four different short attention-getting movies was played in between the animations. Mothers were informed about the procedure but not the content of the stimuli, and were instructed not to talk and to try to keep the infants from moving or leaning. Mothers were wearing blinded sunglasses during the stimulus presentation for their infants. During the mother eye-tracking experiment, the infant was in an adjacent room playing with one of the experimenters. The calibration process and presentation of the animations were identical to that of the infant’s.

Data analysis

A Tobii fixation filter was used with velocity and distance thresholds set to 35 pixels. Fixation measures were calculated using Tobii Studio software and further analyzed with SPSS. Two areas of interest (AOIs) covering the two figures were defined during the Separation segment: a Parent AOI (5.42% of the entire area) and a Baby AOI (2.19%); see . During the Response segments, the same Baby AOI was defined for the “baby” figure. For the “parent” figure, a Parent Going Away AOI (10.91%) was used in the Leaving Response that covered the area traversed by the “parent” figure while moving further up the hill, and a Parent Coming Back AOI (7.37%) was defined in the Return Response covering the path the “parent” figure took while descending the hill; see . Note that the accuracy of the eye-movement recordings did not allow for distinguishing fixations aimed at the “baby” and the “parent” figures when they were next to each other in the Return Response; therefore, only the first period (2.3 s) of both types of Response segments was analyzed, during which the two figures in the Return Response were more than 1 cm away from each other.

Our monitoring measure, the relative fixation duration ratio for the “parent” figure (the duration of fixations for the Parent AOI divided by the sum of the duration of fixations for the Baby AOI and Parent AOI) was calculated during the Separation and Response segments of each “crying” animation (four animations in total, with two identical animations shown twice) and then the ratios were averaged separately for the Separation and the Response segment. (Note that the “laughter movies” were not included in the current analysis and the two types of responses (Leaving or Return) during the Response segment of the “crying” movies were combined.)

Participants who had no data (due to calibration problems or infant distress) for any of the four distress “crying” movies (two mothers, five infants) were excluded. After exclusion, 53 mother–infant dyads remained. The remaining 53 mothers had valid data in all four crying movies. Missing value analysis for infants revealed that during the Separation segment four infants had no data in one movie, one infant in two movies, and two infants in three movies. During the Response segment, 22 infants had no data in one movie, 11 infants in two movies, and 3 infants in three movies. Missing data for infants were imputed in cases when there was valid data for an identical movie (i.e. since two types of movies were shown twice, if, for example, the infant had valid data for one of the two animations of the same type, the other was imputed, but if data for both animations of one type were missing, no imputation was done). The imputation was based on the regression equation predicting the ratio score for one movie by data from the same type of movie and from infants’ fearful temperament score. Infants’ fearful temperament was assessed by the Laboratory Assessment Temperament Battery (Goldsmith & Rothbart, Citation1999) during the lab visit. This measure was only used for imputation and was not part of the current study (see Biro et al., Citation2015 for more details). We included it in the imputation because it enhanced the regression equation predicting the ratio scores of one movie from another. Analyses were done both with and without the imputed data.

Measures: attachment quality: SSP

The SSP (Ainsworth, Citation1978) was used to measure the quality of the infant–mother attachment relationship. In short, the infant is introduced to an unfamiliar lab environment and a female stranger. The mother leaves the room twice and then returns to the room, leaving the infant alone for a short period, first with the stranger and then by herself/himself. Attachment behavior was coded by two experienced coders. One of the coders was trained by Brian Vaughn (ABC) and Mary Main (D) and has been a trainer in SSP coding, and the other coder was trained and certified by Alan Sroufe and Elizabeth Carlson. Both coders were blind to other information about the infants or mothers. The infant’s interactive behavior during the two reunion episodes was rated on four scales each ranging from 1 to 7 (proximity seeking, contact seeking, avoidance, and resistance to contact and interaction). For the present analyses, a continuous score representing security of attachment was computed on the basis of these interactive scales using the simplified Richters, Waters, and Vaughn (Citation1988) algorithm (Van IJzendoorn & Kroonenberg, Citation1990), which gives specific weights for the scores on the interactive scales. A higher overall score indicates a more secure attachment relationship. Furthermore, Main and Solomon’s nine-point scale (1990) was used for coding infants’ disorganized attachment behavior. One third of the sessions (n = 20), randomly selected, were coded by both coders. Intercoder reliability was adequate, the intra-class correlation coefficient (single measure, absolute agreement) was .82 for the continuous security score and .77 for attachment disorganization. In case of disagreements, the scores of the most experienced coder were used. For the included infant–mother dyads (n = 53), the mean score of attachment security was −0.11 (SD = 2.75, range = −7.50–5.16) and the mean score for attachment disorganization was 3.30 (SD = 2.33, SD, range = 1–9). Both scores were centered before inclusion in linear regression.

For a follow-up analysis (see “Results” section), we used a disorganized vs. organized categorical distinction of the infants on the basis of the ABCD classification of the certified coders. Intercoder agreement based on the selected 20 sessions was 85% (κ = .69) for disorganized (D) vs. organized (ABC) categories. For the included infant–mother dyads (n = 53), 16 infants were classified as disorganized and the remaining 37 as organized. For additional information, provides the distribution of infants based on the secondary ABC classification within the organized and disorganized groups. Intercoder agreement for ABC was 75% (κ = .62).

Table 1. Distribution of infants based on the secondary ABC classification within the organized and disorganized groups.

Results

All numerical variables were normally distributed. The distribution of the D scores was slightly positively skewed with more lower values but with adequate standardized skewness (2.03) and kurtosis (–0.85) values. No extreme outliers in any of the variables were detected.

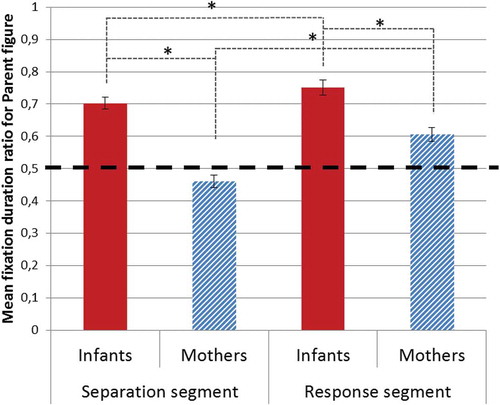

One-sample t-tests (with test value of 0.5) revealed that overall infants focused longer on the “parent” figure relative to the “baby” figure in both the Separation segment, t = 11.18, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 1.53, and the Response segment, t = 10,77, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 1.47. Mothers overall focused equally long on the “parent” figure and the “baby” figure during Separation segment, t = −1.95, p = .06, Cohen’s d = −0.26, and allocated their attention more to the “parent” figure during the Response segment, t = 4.86, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.67. Repeated measures ANOVA with infants’ and mothers’ relative fixation ratios in the Separation and Response segments revealed that infants as a group showed a higher relative fixation ratio for the “parent” figure in both segments than the mother group, F(1, 52) = 52.24, p < .001, ηp2 = .50. In addition, the interaction between segment and observer, F(1, 52) = 8.10, p = .006, ηp2 = .13, showed that mothers focused more on the “parent” figure in the Response segment than in the Separation, t = −6,83, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.84, while this difference was smaller in the infant group, albeit still significant, t = −2.21, p = .04, Cohen’s d = 0.33 (see ).

Figure 2. Mean fixation duration ratio for the “parent” figure for infants and mothers during the Separation and Response segments (* p < .05). Dashed line at 0.5 indicates equal relative fixation duration for “parent” and “baby” figure.

Infants’ attachment security and disorganization scores were negatively correlated indicating that infants with higher security scores showed fewer signs of disorganized attachment behavior (see ). There were no significant correlations between infants’ attachment security or disorganization scores and the relative monitoring of the infant or the mother in the Separation or in the Response segment. In addition, no significant correlations were found between mothers’ and infants’ relative monitoring measures during the Separation or Response segment. Unimputed data yielded correlations that were similar.

Table 2. Correlations (Pearson r) between attachment security, disorganization, and relative monitoring in infants and mothers during the crying animations in the Separation and Response segments.

To test the moderating effect of infants’ attachment security and disorganization on the relation between mother and infant monitoring patterns, linear regression analyses were conducted for the Separation and Response segments separately, with infants’ monitoring as the outcome variable and mothers’ monitoring, attachment security, and attachment disorganization scores as predictors entered in the first step. In the second step, the interaction terms of mothers’ monitoring and infant attachment security scores, and of mothers’ monitoring and infant attachment disorganization scores were entered. The interaction terms were calculated on the basis of the centered variables. In separate linear regression analyses, age and education level of mother were also entered to test if these potential confounders influenced the moderating effect.

For the Separation segment, linear regression revealed a nonsignificant prediction of the model, R2 = .18, F = 2.06, p = .09. Infant security, B = 0.01, β = 0.31, t = 2.22, p = .03, and infant disorganization, B = 0.02, β = 0.34, t = 2.36, p = .02, were both significant predictors of infant monitoring. Our focus variables, mother monitoring, B = −0.034, β = −0.038, t = −0.28, p = .78, the interaction between attachment security and mother’s monitoring, B = 0.07, β = 0.21, t = 1.48, p = .14, and the interaction between attachment disorganization and mother’s monitoring, B = 0.03, β = .09, t = 0.56, p = .57, however, were not significant. With the inclusion of the covariates of age and education, both interaction terms remained nonsignificant in the Separation segment.

For the Response segment, however, the model was significant, R2 = .22, F = 2.67, p = .03. While mother monitoring, security and disorganization were not predictors, the interaction between mothers’ monitoring and infant attachment disorganization showed a significant contribution to the prediction, B = 0.16, β = .34, t = 2.42, p = .02. The interaction between mothers’ monitoring and infant attachment security scores did not contribute significantly, B = −0.04, β = -.09, t = −0.66, p = .51. Tolerance was high (8.54–9), thus multicollinearity was not a concern. With the inclusion of the covariates of age and education, the interaction between mothers’ monitoring and infant attachment disorganization in the Response segment remained significant, B = 0.18, β = .36, t = 2.74, p = .009. These findings indicate that during the Response segment, the relation between mother and infant monitoring patterns was moderated by infant attachment disorganization.

When infants with high and low scores for disorganized attachment behavior were grouped based on a median split, the correlation between mothers’ and infants’ monitoring in the group with low disorganized attachment scores (<4) was significant and negative, r = -.43, p = .01, n = 32, while in the group with disorganized attachment scores ≥4 the correlation was positive (i.e. in the other direction) although not significant, r = .28, p = .21, n = 21. A similar pattern emerged when correlations between the monitoring of mothers and infants were calculated separately for the group classified as organized, r = -.39, p = .02, n = 37, and disorganized, r = .33, p = .21, n = 16, according to the categorical coding system. The linear regressions were also run with unimputed data for infants and revealed similar results. In the Response segment, the interaction term of mother monitoring and infant disorganization was a significant predictor, B = 0.21, β = .34, t = 2.47, p = .02, and the correlations between mothers’ and infants’ monitoring were only significant in the group with lower disorganization score, r = -.45, p = .01, n = 32, or in the group classified as organized, r = -.40, p = .01, n = 37.

Discussion

In the current study, we investigated the attunement of infants’ and their caregivers’ monitoring strategies while they observed animations involving attachment-related interactions. We found that mothers and infants showed dyad-specific patterns in the way they allocated their attention to the interacting characters during the response part of the social situations. Attunement between mother and infant attention was however moderated by infant attachment disorganization. The correspondence between the monitoring of infants and their mothers followed a different pattern in organized and disorganized dyads. We found that organized mother–infant dyads showed a significant negative correlation in their monitoring: the more the mothers focused their attention on the “baby” character, the more their infants focused their attention on the “parent” character, and vice versa, the more the mothers focused on the “parent” figure, the more their infants focused on the “baby” figure. (Note that the monitoring measure is a ratio that reflects how much attention was given to both the “parent” and “baby” figure.) In the disorganized group, the correlation between infant and mother monitoring was about the same magnitude but in the opposite direction. However, possibly due to the relatively low number of dyads in this group, this positive correlation was not significant. Therefore, while the disorganized group certainly showed a significantly different pattern from the organized group, we have to be cautious about the description of the pattern or the lack of it in the disorganized group. The positive correlation suggests that infants and their mothers in the disorganized group tend to focus relatively more on the same characters (“parent” or “baby”) during the observation of the outcome of the interaction.

In the organized dyads, the synchrony was complementary in nature; the relative focus of infants and their mothers within a dyad was on the opposite characters. While on average infants focused more on the “parent” character than the “baby” character, this does not mean that it was the case for all infants. Some infants focused more on the “baby” character but then their mothers focused more on the “parent” character in the organized group. This may indicate that social interactions can be processed with varying underlying attentional biases and that organized attachment is associated with the development of a complementary bias in the social information processing of infants and their mothers. These biases might be related to their internalized representations of social interactions. Infants and their caregivers’ cognitive representations or IWMs about attachment-related events may become attuned due to their shared social–emotional experiences and the ways in which they interact with each other during daily routines. Why this attunement should manifest itself in complementary monitoring strategies is hard to explain. (Note that we did not have any specific hypotheses regarding the form that synchrony would take either.) Perhaps complementary strategies are advantageous in terms of efficiency in processing and responding to environmental input as a dyad. The literature on joint action in both adults and infants emphasizes the importance of developing complementary strategies for the optimal coordination of action and attention to achieve common goals (Brownell, Citation2011; Feniger-Schaal et al., Citation2015; Sebanz, Bekkering, & Knoblich, Citation2006). Feniger-Schaal and colleagues (Citation2015) recently showed that, in adults, less rigid synchrony and more complex coordination during a mirror game was related to attachment security. However, further experiments will be necessary to shed light on the mechanisms and perhaps also on the environmental conditions involved. What is important regarding the current results, though, is that in an organized attachment relationship mothers and infants adapt their monitoring strategies to each other.

The lack of evidence for complementary synchrony with the inconclusive evidence for corresponding synchrony in the monitoring patterns of disorganized infants and their caregivers seems to thus indicate differences in the attunement of IWMs between infants and mothers compared to that of the organized dyads. Our finding fits well with previous research reporting the presence of uniquely different pattern of synchrony during interaction in disorganized mother–child dyads (see review by Beebe & Steele, Citation2013). Beebe and Steele (Citation2013) argue that there is an “optimal midrange” level of interactive contingency in which too high or too low levels of contingent interactions could be problematic. Disorganized attachment was predicted by a unique pattern of dysregulation with lower contingency levels in emotional or touch coordination by both infant and mother and with heightened levels of infant facial or vocal distress, maternal facial self-contingency, and mismatch between mother and infant facial expression (Beebe et al., Citation2010). Our finding of a possible corresponding type of synchrony may thus be another manifestation of a suboptimal level of attunement in social processing. Several mechanisms have been suggested that could lead to disorganized attachment in infancy, including maltreatment, unpredictable environment, frightening/frightened and highly insensitive parental behavior, chronic marital discord, and neurological abnormalities (Cyr, Euser, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Van IJzendoorn, Citation2010; Van IJzendoorn, Schuengel, & Bakermans–Kranenburg, Citation1999). All of these factors could potentially play a role in preventing the fine-tuning of predictable but optimally contingent, turn-taking, and synchronous interactions between infant and caregiver.

We did not find evidence for a moderation effect of attachment security on the relationship between infant and mother monitoring. Mothers of secure infants are generally more sensitive and more synchronous interactions between mother and secure infants have been reported (Bigelow et al., Citation2010; De Wolff & Van IJzendoorn, Citation1997; Leerkes, Citation2011; Lundy, Citation2002, Citation2003). Therefore, we had expected a stronger correspondence in the monitoring patterns in infant–mother dyads with secure infants. However, from the perspective of attachment theory, both secure and insecure infants use an adaptive attachment strategy that “works” for the specific infant–mother dyad. Thus, while the content of secure and insecure infants’ IWMs might be different (i.e. secure but not insecure infants are assumed to have a secure base script in which a child in need will promptly be comforted), biases associated with the contents or organization of the IWMs of a particular mother–infant dyad could still show similar levels and type of correspondence in secure and insecure dyads. The similarity of secure and insecure infants is indirectly supported by the fact that according to the secondary three-way attachment classification of the infants, there were both secure (60%) and insecure infants (avoidant and resistant; 40%) in the organized group.

We would also like to point out that our current finding corroborates our previous finding of differences in the monitoring patterns between secure and insecure infants (Biro et al., Citation2015). In the current study, we also found that security predicted infants’ relative focus on the “parent” figure during the Separation segment of the animations. Note that this was the case even though the current and our previous study differ in terms of the type of stimuli included in the analysis (only cry movies) and the measure of attachment quality (continuous vs. categorical). These differences might contribute to the fact that in the current study, contrary to the previous paper, we found that disorganization of the infant also predicted infants’ relative attention to the “parent” figure during the distress Separation segment. Together these findings point to the possibility that different underlying mechanisms (such as expecting comfort or being overly vigilant) are associated with the monitoring bias of increased focus on “parent” figure. Importantly, however, the question of differences in the monitoring strategies between infants is different from the question of how their monitoring is matched with the monitoring strategies of their own mothers. Secure and insecure or organized and disorganized infants may see the world differently but both views could be related to their mothers’ views.

An interesting aspect of our finding was that the complementary synchrony in monitoring was restricted to the response part of the animation. The main perceptual difference between the two segments is that the Separation segment depicts a static while the Response segment involves a dynamic stimulus. There is evidence that static scenes are more likely to elicit a high degree of variation in eye-movements compared to dynamic scenes especially in free viewing conditions (Smith & Mital, Citation2013), which decreases the chance of finding matching monitoring patterns. Furthermore, the shorter duration of the Response segment compared to the Separation segment may have allowed the capturing of a more automatic, less consciously controlled processing of the situation that may have also facilitated attentional synchrony.

The movement of the parent figure in the Response segment is an exogenous, stimulus-driven factor that likely clusters fixations from different viewers, which might explain why overall both mothers and infants focused their attention more on the “parent” figure than the “baby” figure. It could in principle also explain the synchrony between infants and mothers assuming that there might be genetic factors involved in the extent to which an individual’s attention is drawn by the motion. However, the complementary nature of the synchrony in the monitoring between infants and their mothers and the moderating role of infant disorganization renders this explanation unlikely. It has also been shown that endogenous factors such as knowledge or expectations of the viewer can influence fixation allocation and fixation duration during dynamic scenes in both adult and infant studies (Johnson, Slemmer, & Amso, Citation2004; Klein, Zwickel, Prinz, & Frith, Citation2009; Zwickel, White, Coniston, Senju, & Frith, Citation2010). In our study, expectations about the interaction and about relevance of the state of the characters as well as their role in the resolution of the situation could include the dyad-specific endogenous factors that resulted in matching monitoring patterns in the organized mother–infant dyads. Future studies need to investigate the exact role of the different factors in monitoring processes.

Regarding the limitations of our study, as we mentioned earlier, due to our relatively small sample size the interpretation of the moderation effect in the disorganized group is inconclusive. Relatedly, since our study is exploratory (this is the very first study on attachment quality and synchrony in monitoring processes of mother–infant dyads), it is hard to determine what effect size could be expected. On the basis of the medium effect size we found in the current study (R2 = 0.22), we estimated what the expected power would be for replicating such an effect in another study. We found that power for the medium range effect size is between 0.50 and 0.90. This means that a larger sample in future studies is useful to enhance the power to detect effect sizes in the medium range. A further issue is that we did not vary the order of the SSP and eye-tracking measures; therefore, it could be argued that the mothers’ participation in the SSP may have affected their response in the eye-tracking task. However, since other pleasant and playful observational measures lasting for about an hour (not part of the current study) and a break between SSP and eye-tracking measure were included, it is plausible that activation of mothers’ caregiving system was no longer affected by the SSP.

Finally, our findings fit with the notion of intergenerational transmission of attachment, which refers to the emergence of the matching attachment representation in the offspring to that of the parent (Verhage et al., Citation2016). Growing attunement of attentional biases for social interaction between mother and infant may well play a role in such transmission. Future research should investigate whether our findings hold in other attachment-related situations and whether synchrony in attentional processes are unique to attachment-related events or could be observed in a broader range of situations. Equally important is it to test the direct relation between synchrony of attentional processes in mother–infant dyads for animated interactions and the degree and nature of synchrony while they interact with each other. The moderating effect of infant disorganization should be replicated, as our study is the first to suggest the emergence of complementary synchrony in attentional processes during observation of animated social interactions in organized infants and their mothers.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank the parents and the infants who participated in our study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ainsworth, M. D., Blehar, M., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978) Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J., Van IJzendoorn, M.H., & Kroonenberg, P.M. (2004). Differences in attachment security between African-American and white children: Ethnicity or socio-economic status? Infant Behavior and Development, 27(3), 417–433. doi:10.1016/j.infbeh.2004.02.002

- Beebe, B., Jaffe, J., Markese, S., Buck, K., Chen, H., Cohen, P., … Feldstein, S. (2010). The origins of 12-month attachment: A microanalysis of 4-month mother–infant interaction. Attachment & Human Development, 12(1–2), 3–141. doi:10.1080/14616730903338985

- Beebe, B., & Steele, M. (2013). How does microanalysis of mother–infant communication inform maternal sensitivity and infant attachment? Attachment & Human Development, 15(5–6), 583–602. doi:10.1080/14616734.2013.841050

- Bigelow, A.E., MacLean, K., Proctor, J., Myatt, T., Gillis, R., & Power, M. (2010). Maternal sensitivity throughout infancy: Continuity and relation to attachment security. Infant Behavior and Development, 33(1), 50–60. doi:10.1016/j.infbeh.2009.10.009

- Biro, S., Alink, L.R.A., Huffmeijer, R., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J., & Van IJzendoorn, M.H. (2015). Attachment and maternal sensitivity are related to infants’ monitoring of animated social interactions. Brain and Behavior, 5(12), e00410. doi:10.1002/brb3.410

- Biro, S., Alink, L.R.A., Van IJzendoorn, M.H., & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J. (2014). Infants’ monitoring of social interactions: The effect of emotional cues. Emotion, 14(2), 263–271. doi:10.1037/a0035589

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss. Vol 1. Attachment. New York: Basic Books.

- Braungart-Rieker, J., Garwood, M., Powers, B., & Wang, X. (2001). Parental sensitivity, infant affect, and affect regulation: Predictors of later attachment. Child Development, 72(1), 252–270. doi:10.1111/cdev.2001.72.issue-1

- Bretherton, I., & Munholland, K.A. (2008). Internal working models in attachment relationships. In J. Cassidy & P.R. Shaver (Eds.), The Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed., pp. 102–127). New York: Guilford Press.

- Brownell, C.A. (2011). Early developments in joint action. Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 2(2), 193–211. doi:10.1007/s13164-011-0056-1

- Bureau, J.-F., Yurkowski, K., Schmiedel, S., Martin, J., Moss, E., & Pallanca, D. (2014). Making children laugh: Parent–child dyadic synchrony and preschool attachment. Infant Mental Health Journal, 35, 482–494. doi:10.1002/imhj.21474

- Cyr, C., Euser, E.M., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J., & Van IJzendoorn, M.H. (2010). Attachment security and disorganization in maltreating and high-risk families: A series of meta-analyses. Development and Psychopathology, 22(01), 87–108. doi:10.1017/S0954579409990289

- De Wolff, M.S., & Van IJzendoorn, M.H. (1997). Sensitivity and attachment: A meta-analysis on parental antecedents of infant attachment. Child Development, 68, 571–591. doi:10.1111/cdev.1997.68.issue-4

- Dykas, M.J., & Cassidy, J. (2011). Attachment and the processing of social information across the life span: Theory and evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 137(1), 19–46. doi:10.1037/a0021367

- Feldman, R. (2007a). Parent–infant synchrony biological foundations and developmental outcomes. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(6), 340–345. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00532.x

- Feldman, R. (2007b). Mother-infant synchrony and the development of moral orientation in childhood and adolescence: Direct and indirect mechanisms of developmental continuity. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 77, 582–597. doi:10.1037/0002-9432.77.4.582

- Feldman, R., Magori-Cohen, R., Galili, G., Singer, M., & Louzoun, Y. (2011). Mother and infant coordinate heart rhythms through episodes of interaction synchrony. Infant Behavior and Development, 34(4), 569–577. doi:10.1016/j.infbeh.2011.06.008

- Feniger-Schaal, R., Noy, L., Hart, Y., Koren-Karie, N., Mayo, A.E., & Alon, U. (2015). Would you like to play together? Adults’ attachment and the mirror game. Attachment & Human Development, 18(1), 33–45. doi:10.1080/14616734.2015.1109677

- García-Sellers, M.J., & Church, K. (2000). Avoidance, frustration and hostility during toddlers’ interaction with their mothers and fathers. Infant-Toddler Intervention, 10, 259–274.

- Goldsmith, H.H., & Rothbart, M.K. (1999). Laboratory temperament assessment battery (Technical Manual). USA: University of Wisconsin-Madison.

- Harrist, A.W., Pettit, G.S., Dodge, K.A., & Bates, J.E. (1994). Dyadic synchrony in mother–child interaction: Relation with children’s subsequent kindergarten adjustment. Family Relations: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies, 43, 417–424. doi:10.2307/585373

- Isabella, R.A., Belsky, J., & Von Eye, A. (1989). Origins of infant-mother attachment: An examination of interactional synchrony during the infant’s first year. Developmental Psychology, 25, 12–21. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.25.1.12

- Jaffe, F., Beebe, B., Feldstein, S., Crown, C.L., & Jasnow, M.D. (2001). Rhythms of dialogue in infancy. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 66(2) , i-149.

- Johnson, S.C., Dweck, C., & Chen, F.S. (2007). Evidence for infants’ internal working models of attachment. Psychological Science, 18(6), 501. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01929.x

- Johnson, S.C., Dweck, C., Chen, F.S., Ok, S.J., Stern, H.L., & Barth, M.E. (2010). At the intersection of social and cognitive development: Internal working models of attachment in infancy. Journal of Cognitive Science, 34(5), 807–825. doi:10.1111/j.1551-6709.2010.01112.x

- Johnson, S.P., Slemmer, J.A., & Amso, D. (2004). Where infants look determines how they see: Eye movements and object perception performance in 3-month-olds. Infancy, 6(2), 185–201. doi:10.1207/s15327078in0602_3

- Klein, A.M., Zwickel, J., Prinz, W., & Frith, U. (2009). Animated triangles: An eye tracking investigation. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 62(6), 1189–1197. doi:10.1080/17470210802384214

- Leclère, C., Viaux, S., Avril, M., Achard, C., Chetouani, M., Missonnier, S., & Cohen, D. (2014). Why synchrony matters during mother-child interactions: A systematic review. Plos One, 9(12), e113571. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0113571

- Leerkes, E.R.M. (2011). Maternal sensitivity during distressing tasks: A unique predictor of attachment security. Infant Behavior and Development, 34(3), 443–446. doi:10.1016/j.infbeh.2011.04.006

- Lundy, B.L. (2002). Paternal socio-psychological factors and infant attachment: The mediating role of synchrony in father-infant interactions. Infant Behavior & Development, 25, 221–236. doi:10.1016/S0163-6383(02)00123-6

- Lundy, B.L. (2003). Father- and mother-infant face-to-face interactions: Differences in mind-related comments and infant attachment? Infant Behavior & Development, 26, 200–212. doi:10.1016/S0163-6383(03)00017-1

- Main, M., & Hesse, E. (1990). Parents’ unresolved traumatic experiences are related to infant disorganized attachment status: Is frightened and/or frightening parental behavior the linking mechanism? In M.T. Greenberg, D. Cicchetti, & E.M. Cummings (Eds.), Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research, and intervention (pp. pp. 161-182). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Malatesta, C., Culver, C., Tesman, J., & Shepard, B. (1989). The development of emotion expression during the first two years of life. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 54, 1–136. doi:10.2307/1166153

- Peltola, M.J., Forssman, L., Puura, K., Van IJzendoorn, M.H., & Leppänen, J.M. (2015). Infant precursors of attachment: Attention to facial expressions of fear at 7 months predicts attachment security at 14 months. Child Development, 86(5), 1321–1332. doi:10.1111/cdev.12380

- Richters, J.E., Waters, E., & Vaughn, B.E. (1988). Empirical classification of infant-mother relationships from interactive behavior and crying during reunion. Child Development, 512–522. doi:10.2307/1130329

- Schuengel, C., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J., & Van IJzendoorn, M.H. (1999). Frightening maternal behavior linking unresolved loss and disorganized infant attachment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67(1), 54–63. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.67.1.54

- Sebanz, N., Bekkering, H., & Knoblich, G. (2006). Joint action: Bodies and minds moving together. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10(2), 70–76. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2005.12.009

- Smith, T.J., & Mital, P.K. (2013). Attentional synchrony and the influence of viewing task on gaze behavior in static and dynamic scenes. Journal of Vision, 13(8), 16–16. doi:10.1167/13.8.16

- Tronick, E.Z. (1989). Emotions and emotional communication in infants. American Psychologist, 44, 112–126. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.44.2.112

- Van IJzendoorn, M.H., & Kroonenberg, P.M. (1990). Cross-cultural consistency of coding the strange situation. Infant Behavior and Development, 13(4), 469–485. doi:10.1016/0163-6383(90)90017-3

- Van IJzendoorn, M.H., Schuengel, C., & Bakermans–Kranenburg, M.J. (1999). Disorganized attachment in early childhood: Meta-analysis of precursors, concomitants, and sequelae. Development and Psychopathology, 11(2), 225–250. doi:10.1017/S0954579499002035

- Verhage, M.L., Schuengel, C., Madigan, S., Fearon, R.M., Oosterman, M., Cassiba, R., … Van IJzendoorn, M.H. (2016). Narrowing the transmission gap: A syntheses of three decades of research on intergenerational transmission of attachment. Psychological Bulletin, 142(4), 337–366. doi:10.1037/bul0000038

- Waters, H.S., & Waters, E. (2006). The attachment working models concept: Among other things, we build script-like representations of secure base experiences. Attachment & Human Development, 8, 185–197. doi:10.1080/14616730600856016

- Zwickel, J., White, S.J., Coniston, D., Senju, A., & Frith, U. (2010). Exploring the building blocks of social cognition: Spontaneous agency perception and visual perspective taking in autism. Scan, 6(5), 564-571.