ABSTRACT

Video-feedback Intervention to promote positive parenting-visual (VIPP-V) or visual-and-intellectual disability is an attachment-based intervention aimed at enhancing sensitive parenting and promoting positive parent–child relationships. A randomized controlled trial was conducted to assess the efficacy of VIPP-V for parents of children aged 1–5 with visual or visual-and-intellectual disabilities. A total of 37 dyads received only care-as-usual (CAU) and 40 received VIPP-V besides CAU. The parents receiving VIPP-V did not show increased parental sensitivity or parent–child interaction quality, however, their parenting self-efficacy increased. Moreover, the increase in parental self-efficacy predicted the increase in parent–child interaction. In conclusion, VIPP-V does not appear to directly improve the quality of contact between parent and child, but does contribute to the self-efficacy of parents to support and to comfort their child. Moreover, as parents experience their parenting as more positive, this may eventually lead to higher sensitive responsiveness and more positive parent–child interactions.

1. Introduction

For parents of young children with a visual disability, communication and interaction with their child is generally more difficult. As these children can appear more unresponsive to the parent because of a lack of eye contact, absence of reciprocal smiling, and fewer emotional expressions, parent–child interactions can get disturbed (e.g. Howe, Citation2006; Tröster & Brambring, Citation1992). About half of the children with visual disabilities in Western Europe also exhibit intellectual disabilities (Boonstra et al., Citation2012; Rosenberg et al., Citation1996). In these cases, communicating with the child may be even more difficult, because of the child’s relatively slow information processing and delay or absence of social responses (Howe, Citation2006; Spiker, Boyce, & Boyce, Citation2002). Furthermore, children with intellectual disabilities tend to use fewer internal state words, i.e. communicate less on thoughts or feelings, and it appeared that over time, their mothers also use less internal state words in communicating with their children (Beeghly & Cicchetti, Citation1997). This negatively affects the quality of communication and joint affect regulation (Howe, Citation2006). In sum, parents of children with visual or visual-and-intellectual disabilities may experience difficulties in understanding and interpreting the communicative signals of their child, which could make parents less sensitive and responsive toward their child (Howe, Citation2006).

Sensitive parenting and, as a result, a secure attachment relationship may be particularly relevant for children with disabilities (Baker, Fenning, Crnic, Baker, & Blacher, Citation2007; Schuengel & Janssen, Citation2006), yet secure attachment may be more difficult to establish than in relationships between parents and children without disabilities (Howe, Citation2006). Firstly, in order to be sensitive and responsive as a parent, it is necessary to recognize, understand, and interpret the child’s communicative signals. For children with visual or visual-and-intellectual disabilities, however, it is more difficult to clearly communicate their needs, emotions, and mental states to their parents (e.g. Howe, Citation2006; Moran, Pederson, Pettit, & Krupka, Citation1992). Secondly, for parents it can be difficult to resolve their feelings concerning their child’s condition (Neely-Barnes & Dia, Citation2008; Reichman, Corman, & Noonan, Citation2008). This, in turn, has been related to poorer sensitivity and emotional attunement (Barnett et al., Citation1999). Lastly, the often stressful period around obtaining the diagnosis and the associated emotional confusion coincides with the period in which attachment relationships are established. Attachment-based early intervention may therefore be of great value for parents of children with visual or visual-and-intellectual disabilities.

Not only the attachment relationship may be under strain, but parents of children with visual disabilities may experience more stress and feel less competent in their parenting role as well (Howe, Citation2006; Spiker et al., Citation2002). Caring for a child with a disability has an impact in terms of economic costs, less social support, and higher child-caring demands (Mitchell & Sloper, Citation2002; Sloper, Jones, Triggs, Howarth, & Barton, Citation2003). These factors may be experienced as stressful and parents may feel less competent and more stressed because of the higher parenting demands and smaller social supportive network to help them cope. Possibly even more important with respect to attachment, is that previous studies have shown that specific problems in interpersonal communication with their child are also related to parental stress (e.g. Hoppes & Harris, Citation1990; Johnston et al., Citation2003), which is particularly relevant for children with visual (and intellectual) disabilities.

Despite several studies indicating that parents of children with visual or visual-and-intellectual disabilities encounter more rearing difficulties (e.g. Spiker et al., Citation2002; Tröster & Brambring, Citation1992), to date, effect studies on early-intervention programs in which these parents can learn to relate to their child with a disability in an appropriate and attuned way are scarce (Affleck, McGrade, McQueeney, & Allen, Citation1982; Preisler, Citation1991). In contrast, for children without disabilities, a meta-analysis showed that particularly interventions focused on sensitive parenting were effective and that intervention programs with a moderate number of sessions were more effective than long (over 16 sessions) interventions (Bakermans-Kranenburg, Van IJzendoorn, & Juffer, Citation2003).

Based on these findings, Video-feedback intervention to promote positive parenting (VIPP) has been developed (Juffer, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Van IJzendoorn, Citation2008). VIPP is an evidence-based attachment-oriented intervention aimed to enhance parental sensitivity, by providing personal video feedback on sensitive responsiveness (Juffer et al., Citation2008). It has previously been shown that discussing parents’ interaction with their child by using video-recordings enhances insight in the specific needs of their child and improves parental responsiveness (Steele et al., Citation2014). VIPP focuses on the relationship between parent and child and their interactions. Moreover, a trusting alliance between the parent and the intervener is essential, and parents are explicitly acknowledged as experts on their own child and empowered through positive feedback. Specific themes are (1) exploration versus attachment behavior – showing the difference between these behaviors and learning when and how the child needs their parent; (2) “speaking for the child” – increasing accurate perception of the child’s signals by verbalizing the child’s nonverbal cues shown on videotape; (3) “sensitivity chain” – explaining the relevance of parents’ sensitive responses to the child’s signals and highlighting the child’s positive reaction to the parents’ response; and (4) sharing emotions – showing and encouraging parents’ affective attunement to their child’s positive and negative emotions (Juffer et al., Citation2008; Juffer, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Van IJzendoorn, Citation2017). This intervention has been adapted for and shown effective in several subpopulations, such as parents of children at risk of externalizing problem behavior (VIPP-SD; Van Zeijl et al., Citation2006) and parents who themselves have a learning disability (VIPP-LD; Hodes, Meppelder, Kef, & Schuengel, Citation2014) (For a full review see Juffer, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Van IJzendoorn, Citation2018). However, to date, despite various studies aiming to enhance parental sensitivity and attachment, young children with visual impairments have not previously been studied (Steele & Steele, Citation2018).

To meet the specific needs of parents of young children with visual or visual-and-intellectual disabilities, “Video-feedback Intervention to promote Positive Parenting in parents of children with Visual or visual-and-intellectual disabilities” (Video-feedback Intervention to promote positive parenting-visual [VIPP-V]) has been developed. VIPP has been adapted particularly for these parents based on reported clinical expertise within a Delphi group and a recent systematic review examining the necessary additional themes (Van Den Broek et al., Citation2017). As these sources stressed the importance of including a focus on interaction, intersubjectivity, and joint attention, these themes have been added to the intervention for parents of young children with visual or visual-and-intellectual disabilities.

Therefore, the objective of the present study is to examine the efficacy of an attachment-based video-feedback parenting intervention for parents of young children with a VIPP-V or visual-and-intellectual disability. This will be examined by comparing two groups in a randomized controlled trial (RCT): one group receiving VIPP-V as well as care-as-usual (CAU) and one group receiving only CAU. Primary outcomes are parental sensitivity, parent–child interaction quality, parenting self-efficacy, and parenting stress. It is hypothesized that participation in VIPP-V will be associated with stronger improvement in parental sensitive responsiveness, quality of parent–child interaction, parenting self-efficacy, and decreased parenting stress than receiving CAU only. As the therapeutic working alliance has been shown to predict more successful intervention outcomes (Del Re, Flückiger, Horvath, Symonds, & Wampold, Citation2012), this is taken into account as a potential predictor of change. The level of empathy of the VIPP-V worker may also be associated with the relationship with the parent (Gibbons, Citation2011) and is therefore assessed as a potential predictor of change as well.

2. Methods

Study design

This study is a RCT with two conditions. One group received an attachment-based video-feedback parenting intervention (VIPP-V) in combination with CAU and one group received only CAU. Effects were tested at three time points; at pretest, posttest (several weeks after the intervention), and at follow-up after at least3 months. This trial was carried out in the two national organizations specialized in care for people with visual impairments and their families (Royal Dutch Visio and Bartiméus) and has been registered in the Nederlands Trial Register (NTR4306). For full details of the study protocol see Overbeek, Sterkenburg, Kef, and Schuengel (Citation2015).

Procedure and randomization

Parents of young children aged 1–5 years with a visual or visual-and-intellectual disability were sent information on the study and a consent form through Royal Dutch Visio and Bartiméus, and early-intervention workers personally informed eligible families in their caseload about the study. Families who were approached for participation but did not wish to participate remained anonymous to the researchers. If families decided to participate, they signed a consent form and filled out a demographic questionnaire. The early-intervention workers also completed consent forms. Participating families were enrolled in blocks of 16–18 families, and in both Royal Dutch Visio and Bartiméus three blocks were formed. Randomization was performed as stratified (on age and organization) block randomization with a 1:1 allocation using a computerized random number generator. Data collection took place from April 2014 to December 2016.

The pretest assessment (T0) took place after randomization, and on average 7.18 (SD = 6.64) weeks before the intervention started. The intervention lasted approximately 5 months and on average 6.90 (SD = 4.92) weeks after the last home-visit, the posttest, took place, with the follow-up assessment on average 6.31 (SD = 1.68) months later. Families in the CAU group were assessed at the same time-points. Assessments took place in the family home and consisted of a 20–30 min computerized administration of questionnaires for the parent, and a parent–child interaction play task of 15 min (see Measures). This procedure was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee (METc VUmc 2013/449/NL47334.029.13).

Parents agreed to participate before randomization into the conditions. It was not possible for intervention workers to be blind to the randomization. Research assistants conducting the assessments were also not blind to randomization, as the questionnaires differed slightly between the conditions; in the VIPP-V intervention group the Working Alliance Inventory (WAI) and the EQ-short was administered. Researchers coding and analyzing the observation data were blind to the randomization and assessment (pretest, posttest, or follow-up).

Participants

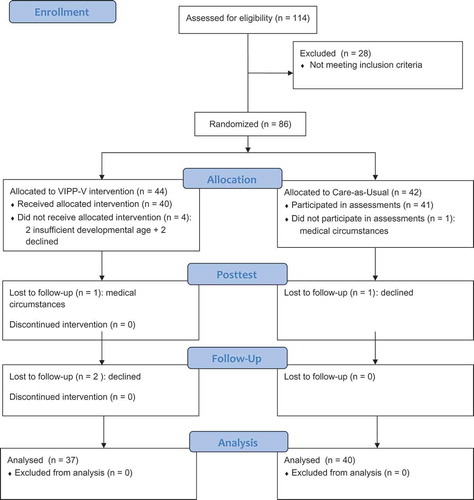

A total of 114 parents of young children with a visual or visual-and-intellectual disability were assessed for eligibility. See for a CONSORT flow diagram. A total of 28 participants did not fulfill inclusion criteria. After allocation of the remaining 86 participants, retention was high, i.e. 90% (N = 77). The families who withdrew did not differ from those retaining on allocated condition (χ2(1) = 3.91, p = .089), child’s gender (χ2(1) = 0.74, p = .52), age (t(80) = −0.49, p = .26), visual disability (χ2(1) = 0.95, p = 1.0), presence of hearing impairment (χ2(1) = 0.46, p = 1.0) or syndrome (χ2(1) = 1.27, p = .33) or medication use (χ2(1) = 2.34, p = .15), nor on parent’s gender (χ2(1) = = 1.17, p = .37), age (t(79) = −0.72, p = .47), educational level (χ2(1) = 2.80, p = .25), ethnicity (χ2(1) = 0.33, p = .95), single parenting (χ2(1) = 4.19, p = .12), or parental disability (χ2(1) = 1.28, p = .59). In families who withdrew from the study, the child did more often have an intellectual (χ2(1) = 9.39, p = .005) or physical disability (χ2(1) = 7.31, p = .012).

In , characteristics of the experimental VIPP-V group and CAU group are compared. It can be seen that the groups were similar on all demographic variables and disabilities.

Table 1. Demographic and disability characteristics for the VIPP-V and CAU groups.

Video-feedback intervention to promote positive parenting in parents of children with visual or visual-and-intellectual disabilities

This intervention program was based on the original VIPP (Juffer et al., Citation2008). VIPP consists of four themes in a standardized order; (1) exploration versus attachment behavior, (2) “speaking for the child,” (3) “sensitivity chain,” and (4) sharing emotions, followed by two booster sessions, yet individualized to each specific parent–child dyad. Adaptations to the intervention were made in close collaboration with professionals from Royal Dutch Visio and Bartiméus and based on knowledge of behavior patterns of young children with visual or visual-and-intellectual disabilities, clinical experience, and knowledge of attachment-based interventions (Van Den Broek et al., Citation2017). Elements of VIPP-SD (sensitive discipline; Van Zeijl et al., Citation2006) and Video-feedback intervention to promote positive parenting for children with autism (VIPP-AUTI; Poslawsky et al., Citation2014) were used to make this new intervention applicable for use in families with a young child with a visual or visual-and-intellectual disability. Particular attention was devoted to increasing (safe) exploration, joint attention, and parent’s abilities to recognize and understand the signals and emotions of their child (Van Den Broek et al., Citation2017).

VIPP-V consists of seven 1.5-h sessions. In , the themes per session are described. The first five sessions are similar to the original VIPP themes, with an added component each session addressing specific skills which (parents of) children with visual or visual-and-intellectual disabilities often experience difficulties with (see Van Den Broek et al., Citation2017). These added components are: predictability, safety, independence, making demands of the child, dealing with changes and frustration, sharing of attention, joint attention, recognizing and naming emotions, and empathy and induction (see ). The sixth and seventh sessions are booster sessions. The intervention focuses on the primary caregiving parent. The five regular home-visits are scheduled every 2–3 weeks, and the two booster sessions are scheduled in the next2 months (every 4–5 weeks). In these booster sessions, the other parent is also invited to participate.

Table 2. Description of themes in each home-visit in VIPP-V, including additions to the original VIPP.

Extensively trained professionals (see Overbeek et al., Citation2015) used a standardized protocol describing the goals and activities of each home-visit, but also leaving sufficient flexibility to adapt for specific needs of the parent–child dyad. Each home-visit starts with video-taping the parent–child dyad in various tasks, after which feedback on the video of the previous home-visit is discussed and the intervention worker provides information on sensitive responsiveness and visual/visual-and-intellectual disabilities. At the end of the last home-visit, parents receive a brochure with a summary of the most important elements discussed in the intervention, including several tips, and the video-recordings.

To ensure treatment fidelity the scripts of three randomly selected VIPP-V workers were checked by a VIPP-V trained scientist-practitioner and fidelity was confirmed.

Care-as-usual

The CAU group received early-intervention care, while the intervention group received early-intervention care and VIPP-V. The frequency in contact between care worker and parents is determined by the parents’ needs, for example regarding mobility or visual support. Therefore, the frequency is very different for the participating parents. To reduce the risk of contamination, the VIPP-V intervention workers were not familiar with the parents and were not the general early-intervention worker of this family. Thus, a VIPP-V intervention worker of one team/region treated families they had not visited earlier. Due to the high number of CAU workers and the varying contact between the CAU workers and the parents, it was not possible to have frequent and reliable data concerning the working alliance and empathy for the CAU group. To reduce the risk of contamination, the VIPP-V intervention workers were independent from the team providing CAU.

Primary outcome measures

The main research question of this study was whether parents of a child with a visual or visual-and-intellectual disability benefit from participating in VIPP-V in terms of higher parental sensitivity and better parent–child interaction quality compared to receiving CAU only.

Parental sensitivity and quality of parent–child interaction was assessed at pretest, posttest, and follow-up using the Three Boxes-procedure (Appelbaum et al., Citation1999; Vandell, Citation1979). For ease of transportation to the home-visits, bags were used instead of boxes. The bags were numbered and parents were instructed to play with their child with toys in the bags in a specified order. The toys were slightly adapted for children with visual disabilities and more toys were used for older (age 3–5 years) than for younger (age 1–2 years) children. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Scales were used to code parental sensitivity and quality of parent–child interaction (Egeland & Hiester, Citation1993) on a 7-point Likert-scale, ranging from “very low (1)” to “very high (7)” on five parent scales (supportive presence, respect for child’s autonomy, stimulation of cognitive development, and hostility and confidence), four child scales (enthusiasm, negativity, persistence and affection toward mother), and one dyad scale (affective mutuality). A parental sensitivity composite was calculated as the sum of supportive presence, hostility (reversed), and respect for autonomy (Egeland & Hiester, Citation1993). Three coders were trained by the fifth author (Prof. Dr Schuengel), who has previously established reliability (Oosterman & Schuengel, Citation2008; Potharst et al., Citation2012). Videotapes were randomly assigned to a pool of three trained coders, who were blind to condition and assessment and showed high inter-coder reliability with single measure Intraclass Correlations (ICC's) of respectively .86, .79, and .84. Certainty of their scores and validity (whether the task was performed as intended) were scored on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = very uncertain/very worrisome to 5 = very certain/excellent with an average certainty of 3.97 (SD = 0.61) and validity of 4.22 (SD = .93). A total of 16% of the videotapes were double coded, including all videotapes with certainty scores below 3. In the current study, the parental sensitivity composite was used to assess parental sensitivity and the affective mutuality dyad scale to assess the quality of parent–child interaction. Cronbach’s alpha of the parental sensitivity composite was .72 at T0, .79 at T1, and .67 at T2.

Secondary outcome measures

In addition to the main research question, we also studied whether parents of a child with a visual or visual-and-intellectual disability benefit from participating in VIPP-V in terms of lower parenting stress and higher parenting self-efficacy compared to receiving CAU only.

Parenting self-efficacy

Parenting self-efficacy was examined using the Self-efficacy in the Nurturing Role questionnaire (Pedersen, Bryan, Huffman, & Del Carmen, Citation1989) in Dutch translation (Verhage, Oosterman, & Schuengel, Citation2013) at pretest, posttest, and follow-up. This questionnaire consists of 16 items, capturing parents’ perceptions of their competence on basic skills required in taking care of their child. The items were slightly modified for parents of children aged 1–5 years, instead of infants. Examples are: “I feel competent in my role as a parent” and “Touching, holding and being affectionate with my child is comfortable and pleasurable for me” and items are rated on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 = “not at all applicable to me” to 7 = “totally applicable to me.” Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .84 to .89 in the current study.

Parenting stress

At pretest, posttest, and follow-up parents reported on overall stress experienced in parenting using the shortened Dutch version of the Parenting Stress Index (Abidin, Citation1983; De Brock, Vermulst, Gerris, & Abidin, Citation1992). It consists of 25 items assessing child-related parenting stress (e.g. “My child cries or fusses more often than other children”) and parent-related parenting stress (e.g. “I often feel that I cannot handle things”). Questions are rated on a 6-point-scale, ranging from 1 = “totally disagree” to 6 = “totally agree.” Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .92 to .95 in the current study.

Moderators and predictors of change

As moderator variables, demographic variables, and the child’s developmental age were studied. Working alliance between the VIPP-V intervention worker and parent, and empathy of the VIPP-V intervention worker were studied as predictors of change in the VIPP-V group.

Demographic and disability characteristics

Before pretest, parents completed a 14-item demographic questionnaire. Questions were asked on ages and genders of the participating parent and child as well as other family members, cultural and socio-economic background, parental health, nature and severity of the disability of the child, medical background and medication use of the child, and possible disabilities of other family members.

Children’s developmental age

Children’s developmental age was assessed by the early-intervention worker who provided CAU in the family by the Dutch screening version of the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (Sparrow, Balla, & Cichetti, Citation1984; Van Duijn, Dijkxhoorn, Noens, Scholte, & Van Berckelaer-Onnes, Citation2009). Children’s adaptive behavior was measured with 93 items on 4 domains: communication, daily living skills, socialization, and motor skills together composing a total adaptive behavior. Cronbach’s alpha was .98.

Working alliance

Working alliance according to both the parent receiving VIPP-V and the VIPP-V worker was assessed using the Dutch translation of the short version of the WAI (Horvath & Greenberg, Citation1989; Tracey & Kokotovic, Citation1989; Vertommen & Vervaeke, Citation1990) at posttest (T1). It consists of 12 items, for example: “We [the parent and VIPP-V intervention worker] have established a good understanding of the kind of changes that would be good for me and my child.” Items are scored on a 5-point scale, ranging from (1) “never” to (5) “always.” It measures general alliance, which can also be divided into three scales (Bond, Goals, and Tasks). In the current study, general alliance was used as a potential predictor of change in the VIPP-V group. Validity and reliability of the original English version has been demonstrated to be good (Horvath & Greenberg, Citation1989), and the Dutch translation as well showed high reliability (Meppelder, Hodes, Kef, & Schuengel, Citation2014). Cronbach’s alphas for general alliance were .69 for the parent and .86 for the VIPP-V worker.

Empathy

Empathy of the VIPP-V worker was assessed at pretest (T0) and posttest (T1) as self-report on the Dutch short version of the empathy quotient (EQ-short; Baron-Cohen & Wheelwright, Citation2004; Wakabayashi et al., Citation2006). The EQ-short consists of 22 items, measuring how easily one picks up other people’s feelings and how strongly one is affected by those feelings, for example “I am good at predicting how someone will feel.” Responses are scored on a 4-point scale, ranging from (1) “totally disagree” to (4) “totally agree,” which are recoded to (0) for nonempathic responses, whatever the magnitude, and (1) or (2) for empathic responses, depending on the strength of the reply. Cronbach’s alphas were .77 at T0 and .84 at T1.

Data analysis

Outliers were not found. Baseline characteristics were described in descriptive analyses. For analyses on the outcome measures of the study (parental sensitivity, parent–child interaction quality, parenting stress, and parenting self-efficacy) analysis of variance (ANOVA)-repeated measures were used with the three assessments (T0, T1, and T2) as “Time” and “Condition” (CAU vs. VIPP-V) as between factor. The intervention effect was examined as the main effect of condition and the Time × Condition interaction effect.

In order to investigate whether change in parenting self-efficacy or parenting stress could predict change in parental sensitivity and parent–child interaction, regression analyses were performed regressing either posttest or follow-up parenting self-efficacy or parenting stress on posttest and follow-up parental sensitivity and parent–child interaction, controlling for pretest self-efficacy, parenting stress, parental sensitivity, and parent–child interaction.

Potential effects of demographic variables (gender, age, type of visual disability (blindness vs. severe visual disability), and presence of intellectual disability) were tested if they appeared to differ between the conditions. We examined the potential moderating effects of the child’s developmental age. Furthermore, it was examined whether working alliance (parent and VIPP-V worker) and empathy of the VIPP-V worker (pre- and posttest) were predictors of change in the VIPP-V group. Intention-to-treat and completer analyses were performed.

With an expected effect size of d = 0.33 and an alpha of .05, 100 families were aimed to participate resulting in adequate statistical power (0.97) for testing the significance of an interaction effect between the between-subject factor and the within-subject factor in repeated measures ANOVA. With an effect size this high, high power (0.80) can still be achieved with 58 families for the main research question regarding time by group effects on parental sensitivity (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, Citation2007).

3. Results

In , the mean levels of parental sensitivity, parent–child interaction quality (affective mutuality), parenting stress, and parenting self-efficacy are shown for both conditions (CAU and VIPP-V) across time (pretest, posttest, and follow-up).

Table 3. Descriptive statistics (Mean (SD)) of parental sensitivity, parent–child interaction, parenting stress, and parenting self-efficacy for the two conditions across time.

In , correlations between all outcome measures are shown. Parental sensitivity and parent–child interactions were positively and strongly associated at all time points. Parenting stress and self-efficacy were negatively associated. At pretest, parental sensitivity and parent–child interaction were not significantly associated with parenting stress and parenting self-efficacy. At posttest, however, negative correlations between both parental sensitivity and parent–child interaction with parenting stress, and positive correlations with parenting self-efficacy were found. At follow-up as well, negative correlations between both parental sensitivity and parent–child interaction with parenting stress were found, but not with parenting self-efficacy.

Table 4. Correlations between all outcome measures at pretest, posttest, and follow-up.

Intervention effects

Repeated measures ANOVAs indicated no main effects of time on parental sensitivity (F(1,75) = 0.47, p = .624, η2 = .006), of condition (VIPP-V or CAU group) (F(1,75) = 0.72, p = .790, η2 = .001) or of the Time × Condition interaction (F(1,75) = 0.13, p = .715, η2 = .002). For parent–child interaction, a quadratic effect of time (F(1,75) = 5.85, p = .018, η2 = .072) was found, indicating an increase from pretest to posttest and a decrease to follow-up. No effect of condition (F(1,75) < 0.01, p = .977, η2 < .001) or Time × Condition interaction (F(1,75) = 1.30, p = .257, η2 = .017) was found.

On parenting stress no main effect of time (F(1,74) = 2.09, p = .153, η2 = .027), or condition (F(1,74) = 1.13, p = .291, η2 = .015) was found, but a trend toward a quadratic Time × Condition interaction (F(1,75) = 3.52, p = .065, η2 = .045) was present, indicating a decrease in parenting stress for the VIPP-V group from pretest to posttest, which slightly increased to follow-up, whereas parenting stress for the CAU group did not change over time. This trend toward a decrease in parenting stress for the VIPP-V condition was seen on both parent and child subscales.

On parenting self-efficacy a linear effect of time was found (F(1,74) = 6.05, p = .016, η2 = .076), indicating an increase across time in parenting self-efficacy. No main effect of condition was found (F(1,74) = 1.81, p = .183, η2 = .024), but the Time × Condition interaction (F(1,75) = 5.35, p = .024, η2 = .067) was significant, indicating higher parenting self-efficacy for the VIPP-V group compared to CAU at posttest, which further increased at follow-up.

Post-hoc analysis: is change in parenting stress or self-efficacy related to change in parenting sensitivity and parent–child interaction?

Regression analyses indicated that changes in parental sensitivity were not related to changes in parenting stress or parenting self-efficacy. Increases in parent–child interaction from pretest to posttest, however, were predicted by decreases in parenting stress (B = −.38, β = −.30, p = .014, = .50), as well as by increases in parenting self-efficacy (B = .03, β = .26, p = .022,

= .40). Increases in parent–child interaction from pretest to follow-up were not predicted by changes in parenting stress nor parenting self-efficacy.

Moderators and predictors of change

No moderating effects of developmental age were found on any of the outcome measures. Next, predictors of change of working alliance and empathy of the VIPP-V worker were examined. These were only assessed for the group receiving VIPP-V. For working alliance, according to the parent a quadratic interaction with parental sensitivity (F(1,34) = 4.14, p = .050, η2 = .011) was present, as well as for parent–child interaction (F(1,34) = 6.14, p = .018, η2 = .15). In order to probe these interaction effects, a median split was performed on working alliance according to the parent (lower group scored 3.75–4.42 and higher group 4.50–5.00), which indicated that at posttest for the parents reporting the highest working alliance, parental sensitivity, and parent–child interaction were higher compared to the parents reporting lower levels of working alliance, while no differences were present at follow-up. Working alliance according to the VIPP-V worker did not moderate either of the outcome measures.

Empathy of the VIPP-V worker showed a restriction of range with all VIPP-V workers scoring as emphatic (scores of 19–41 on a scale from 0 to 44). This variable was therefore not further analyzed.

Control variables

Five dyads in the VIPP-V group experienced stressful experiences during intervention (1 divorce, 2 moving houses, 1 hospitalization parent, and 1 birth sibling), these dyads did not differ from dyads not having experienced stressful events on any of the outcome measures across time. Furthermore, four parents have a visual disability themselves, they did not differ in any of the outcome measures across time from parents without a visual disability.

Intention-to-treat analyses

Intention-to-treat analyses after multiple imputation resulting in 41 dyads in the CAU and 40 in the VIPP-V condition, yielded similar results as the completer analyses.

Discussion

As parents of children with visual or visual-and-intellectual disabilities may experience difficulties in understanding and interpreting the communicative signals of their child, which could make the interaction between parents and children less sensitive and harmonious (e.g. Howe, Citation2006; Schuengel & Janssen, Citation2006; Tröster & Brambring, Citation1992), attachment-based early intervention may be of value for these parents. To meet the specific needs of parents of young children with a visual or visual-and-intellectual disability, “Video-feedback Intervention to promote Positive Parenting in parents of children with Visual or visual-and-intellectual disabilities” (VIPP-V) has been developed (Van Den Broek et al., Citation2017). Although parents receiving VIPP-V did not show increased parental sensitivity or parent–child interaction, parenting self-efficacy did increase for parents receiving VIPP-V and a trend toward decreased parenting stress was found as well. The relevance of the intervention effect on parenting self-efficacy is underscored by the finding that mothers who increased in parenting self-efficacy also improved in quality of parent–child interaction. Similarly, the relevance of reducing parenting stress was underscored by the finding that mothers who reduced in parenting stress also increased in quality of parent–child interaction.

The null-effects of the intervention on sensitivity and parent–child interaction may be explained by a lower need for an attachment-based intervention for parents of children with visual or visual-and-intellectual disability as compared to other populations in which the VIPP intervention was tested. A recent meta-analysis indicated that overall VIPP is moderately effective in increasing parenting behavior in various populations (Juffer et al., Citation2018), while the effect was stronger for parents at risk for insensitive parenting compared to when their children are at risk for problematic development, as is the case with VIPP-V. More specifically, the efficacy may vary by the type of problematic development of the children, as parents of adopted children (Juffer, Citation1993; Rosenboom, Citation1994) and children at risk of externalizing problem behavior (Van Zeijl et al., Citation2006) did show increased parental sensitivity after VIPP-SD (sensitive discipline), whereas parents of children with an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) did not increase in parental sensitivity after following VIPP-AUTI, although a significant increase in nonintrusiveness was found (Poslawsky et al., Citation2015). Parents receiving VIPP-AUTI did report increased parenting self-efficacy, as did the parents in the current study. The communication difficulties between parents and children with a visual or visual-and-intellectual disability are closely related to those of children with ASD, and may be very different from the parenting difficulties that parents of adopted children and children at risk of externalizing problem behavior experience. It is possible that parents of children with a visual impairment or ASD do not necessarily require a training that enhance their skills for sensitive interaction, but might benefit more from guidance targeted at the specific challenges in the interaction with their child. While the VIPP intervention is individually tailored based on the interaction quality between individual parents and children, the framework for intervention may still be too narrow. Furthermore, the CAU which is provided for the families in this study is also of a very high standard and individual parents and children receive home-based support for some time (sometimes years) from trained support workers who frequently attend courses to keep their knowledge updated, who work in a multidisciplinary team under supervision of a developmental psychologist. Lastly, it is likely that the acuteness of the shock of obtaining the diagnosis has passed. The exact time of diagnosis was unfortunately unknown, yet it is likely that would be soon after birth. At the time of VIPP-V, the intervention need may have already decreased. Future studies should include time of diagnosis and, more importantly, intervene soon after parents obtain a diagnosis for their child.

Although the parenting behaviors, that is, parental sensitivity and parent–child interaction, did not show direct benefit, VIPP-V did enhance parenting efficacy and possibly (but this is uncertain) diminished parenting stress. These intervention effects of parents’ subjective experience are consistent with a considerable body of research that parenting interventions boost confidence in parenting competence (e.g. Bloomfield & Kendall, Citation2012; Poslawsky et al., Citation2015), which indirectly benefit children’s outcomes (e.g. Roskam, Brassart, Loop, Mouton, & Schelstraete, Citation2015; Spiker et al., Citation2002). Moreover, enhanced subjective experiences in parenting were found in turn related to parenting behavior in the current study. This implies that less stress and increased self-efficacy are reasonable intervention targets for enhancing both parents’ wellbeing as well as children’s developmental outcomes (cf. Roskam et al., Citation2017).

A good working alliance between VIPP-V worker and parents predicted intervention success in the current study. This is in line with previous studies in different populations (Kazdin & Whitley, Citation2006) and a crucial element of VIPP (Juffer et al., Citation2008). It is therefore recommended for future studies to control for working alliance to avoid premature dismissal of intervention program benefits, for example by supporting intervention workers in enhancing working alliance or by controlling for working alliance as a moderator.

Some limitations need to be taken into account when interpreting the results of this study. Firstly, the time until follow-up was relatively short. Longer follow-up is important to establish the long-term effects, particularly as this may reveal a possible indirect effect from increased parenting experiences to parenting behavior. Secondly, this trial was carried out in the two Dutch national organizations specialized in care for people with visual disabilities and their families (Royal Dutch Visio and Bartiméus) and generalizability to other centers and the CAU offered may vary across countries. Thirdly, we did not have data on potential stressful events, therapeutic alliance, and empathy in the CAU group and could therefore not compare the groups on these moderators. Lastly, the timing of diagnosis was not assessed, while this may be an important moderator of intervention efficacy.

In conclusion, it is unlikely that VIPP-V directly benefits the increase in quality of the contact between parent and child. VIPP-V is likely to contribute to the self-efficacy of parents to support and to comfort their child. Possibly, it may relieve parenting stress, yet this is uncertain based on the current findings. As parents experience their parenting more positively, this may over time lead to higher sensitive responsiveness and positive parent–child interactions (e.g. Spiker et al., Citation2002). The current study also indicates that a higher level of working alliance between intervention worker and parent may further contribute to intervention success (see also Del Re et al., Citation2012).

Acknowlegments

The authors would like to thank the parents, the professionals and other members of Bartiméus and Royal Visio who contributed generously to this study. We would specifically like to thank dr. F. Juffer for her advice in the adaptation and implementation of VIPP. Thanks to Cindy Kieftenbeld and many master and bachelor students for their important contribution during the data collection. Furthermore, we thank all the parents and children who participated in the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abidin, R. R. (1983). Parenting Stress Index: Manual, administration booklet, (and) research update. Charlottesville: Pediatric Psychology Press.

- Affleck, G., McGrade, B. J., McQueeney, M., & Allen, D. (1982). Relationship-focused early intervention in developmental-disabilities. Exceptional Children, 49, 259–261.

- Appelbaum, M., Batten, D. A., Belsky, J., Booth, C., Bradley, R., Brownell, C. A., et al. (1999). Child care and mother-child interaction in the first 3 years of life. Developmental Psychology, 35, 1399–1413.

- Baker, J. K., Fenning, R. M., Crnic, K. A., Baker, B. L., & Blacher, J. (2007). Prediction of social skills in 6-year-old children with and without developmental, delays: Contributions of early regulation and maternal scaffolding. American Journal of Mental Retardation : AJMR, 112, 375–391.

- Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Juffer, F. (2003). Less is more: Meta-analyses of sensitivity and attachment interventions in early childhood. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 195–215.

- Barnett, D., Hunt, K. H., Butler, C. M., McCaskill, J. W. I. V., Kaplan-Estrin, M., & Pipp-Siegel, S. (1999). Indices of attachment disorganization among toddlers with neurological and non-neurological problems. In J. Solomon & C. George (eds), Attachment disorganization (pp. 189–212). New York: Guilford Press.

- Baron-Cohen, S., & Wheelwright, S. (2004). The empathy quotient: An investigation of adults with Asperger syndrome or high functioning autism, and normal sex differences. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34, 163–175.

- Beeghly, M., & Cicchetti, D. (1997). Talking about the self and other: Emergence of an internal state of lexicon in young children with Down syndrome. Development and Psychopathology, 9, 729–748.

- Bloomfield, L., & Kendall, S. (2012). Parenting self-efficacy, parenting stress and child behaviour before and after a parenting programme. Primary Health Care Research & Development, 13(4), 364–372.

- Boonstra, N., Limburg, H., Tijmes, N., Van Genderen, M., Schuil, J., & Van Nispen, R. (2012). Changes in causes of low vision between 1988 and 2009 in a Dutch population of children. Acta Ophthalmol, 90, 277–286.

- De Brock, A. J. L. L., Vermulst, A. A., Gerris, J. R. M., & Abidin, R. R. (1992). NOSI: Nijmeegse Ouderlijke Stress Index. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Harcourt Assessment B.V.

- Del Re, A. C., Flückiger, C., Horvath, A. O., Symonds, D., & Wampold, B. E. (2012). Therapist effects in the therapeutic alliance–outcome relationship: A restricted-maximum likelihood meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(7), 642–649.

- Egeland, B., & Hiester, M. (1993). Teaching task rating scales. Unpublished scale, Institute of Child Development Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–19. doi:10.3758/BF03193146

- Gibbons, S. B. (2011). Understanding empathy as a complex construct: A review of the literature. Clinical Social Work Journal, 39(3), 243–252.

- Hodes, M. W., Meppelder, H. M., Kef, S., & Schuengel, C. (2014). Tailoring a video-feedback intervention for sensitive discipline to parents with intellectual disabilities: A process evaluation. Attachment & Human Development, 16, 387–401.

- Hoppes, K., & Harris, S. L. (1990). Perceptions of child attachment and maternal gratification in mothers of children with autism and Down syndrome. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 19, 365–370.

- Horvath, A. O., & Greenberg, L. S. (1989). Development and validation of the Working Alliance Inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 36, 223–233.

- Howe, D. (2006). Disabled children, parent-child interaction and attachment. Children Family Social Work, 11, 95–106.

- Johnston, C., Hessl, D., Blasey, C., Eliez, S., Erba, H., Dyer-Friedman, J., … Reiss, A. L. (2003). Factors associated with parenting stress in mothers of children with Fragile X Syndrome. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 24, 267–275.

- Juffer, F. (1993). Verbonden door adoptie. Een experimenteel onderzoek naar hechting en competentie in gezinnen met een adoptiebaby. [Attached through adoption. An experimental study of attachment and competence in families with adopted babies.] Amersfoort, the Netherlands: Academische Uitgeverij.

- Juffer, F., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & Van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2008). Promoting positive parenting; An attachment-based intervention. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Juffer, F., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & Van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2017). Pairing attachment theory and social learning theory in video-feedback intervention to promote positive parenting. Current Opinion in Psychology, 15, 189–194.

- Juffer, F., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & Van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2018). Video-feedback intervention to promote positive parenting and sensitive disciple: Development and meta-analytic evidence for its effectiveness. In H. Steele & M. Steele (Eds.), Handbook of attachment-based interventions (pp. 1-26). New York: Guilford Publications.

- Kazdin, A. E., & Whitley, M. K. (2006). Pretreatment social relations, therapeutic alliance, and improvements in parenting practices in parent management training. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(2), 346–355.

- Meppelder, M., Hodes, M., Kef, S., & Schuengel, C. (2014). Parents with intellectual disabilities seeking professional parenting support: The role of working alliance, stress and informal support. Child Abuse Negl, 38, 1478–1486.

- Mitchell, W., & Sloper, P. (2002). Quality services for disabled children. Research works 2002–02. York: Social Policy Research Unit, University of York.

- Moran, G., Pederson, D. R., Pettit, P., & Krupka, A. (1992). Maternal sensitivity and infant-mother attachment in a developmentally delayed sample. Infant Behavior and Development, 15, 427–442.

- Neely-Barnes, S. L., & Dia, D. A. (2008). Families of children with disabilities: A review of literature and recommendations for interventions. Journal of Early and Intensive Behavior Intervention, 5(3), 93-107.

- Oosterman, M., & Schuengel, C. (2008). Attachment in foster children associated with caregivers’ sensitivity and behavioral problems. Infant Mental Health Journal, 29, 609–623.

- Overbeek, M. M., Sterkenburg, P. S., Kef, S., & Schuengel, C. (2015). The effectiveness of VIPP-V parenting training for parents of young children with a visual or visual-and-intellectual disability: Study protocol of a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Trials, 16, 401.

- Pedersen, F. A., Bryan, Y. E., Huffman, L., & Del Carmen, R. (1989). Constructions of self and offspring in the pregnancy and early infancy periods. Paper presented at the Society for Research in Child Development, Kansas City, MO.

- Poslawsky, I. E., Naber, F. B., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., De Jonge, M. V., Van Engeland, H., & Van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2014). Development of a video-feedback intervention to promote positive parenting for children with autism (VIPP-AUTI). Attachment & Human Development, 16(4), 343–355.

- Poslawsky, I. E., Naber, F. B. A., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Van Daalen, E., Van Engeland, H., & Van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2015). Video-feedback intervention to promote positive parenting adapted to autism (VIPP-AUTI): A randomized controlled trial. Autism, 19(5), 588–603.

- Potharst, E. S., Schuengel, C., Last, B. F., Van Wassenaer, A. G., Kok, J. H., & Houtzager, B. A. (2012). Difference in mother-child interaction between preterm- and term-born preschoolers with and without disabilities. Acta Paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992), 101, 597–603.

- Preisler, G. M. (1991). Early patterns of interaction between blind infants and their sighted mothers. Child Care Health Dev, 17, 65–90.

- Reichman, N. E., Corman, H., & Noonan, K. (2008). Impact of child disability on the family. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 12(6), 679–683.

- Rosenberg, T., Flage, T., Hansen, E., Riise, R., Rudanko, S. L., Viggosson, G., & Tornqvist, K. (1996). Incidence of registered visual impairment in the Nordic child population. The British Journal of Ophthalmology, 80, 49–53.

- Rosenboom, L. G. (1994). Gemengde gezinnen, gemengde gevoelens? Hechting en competentie van adoptiebaby’s in gezinnen met biologisch eigen kinderen. (Mixed families, mixed feelings? Attachment and competence of adopted babies in families with biological children.) Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands.

- Roskam, I., Brassart, E., Houssa, M., Loop, L., Mouton, B., Volckaert, A., … Schelstraete, M. A. (2017). Child-oriented or parent-oriented focused intervention: which is the better way to decrease children’s externalizing behaviors? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(2), 482–496.

- Roskam, I., Brassart, E., Loop, L., Mouton, B., & Schelstraete, M. A. (2015). Stimulating parents’ self-efficacy beliefs or verbal responsiveness: Which is the best way to decrease children’s externalizing behaviors? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 72, 38–48.

- Schuengel, C., & Janssen, C. G. (2006). People with mental retardation and psychopathology: Stress, affect regulation and attachment: A review. International Review of Research in Mental Retardation, 32, 229–260.

- Sloper, P., Jones, L., Triggs, S., Howarth, J., & Barton, K. (2003). Multi-agency care coordination and key worker services for disabled children. Journal of Integrated Care, 11, 9–15.

- Sparrow, S. S., Balla, D. A., & Cichetti, D. V. (1984). Vineland adaptive behavior scales. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

- Spiker, D., Boyce, G. C., & Boyce, L. K. (2002). Parent-child interactions when young children have disabilities. Int Rev Res Mental Retardation, 25, 35–70.

- Steele, H., & Steele, M. (Eds.). (2018). Handbook of attachment-based interventions. New York: Guilford Publications.

- Steele, M., Steele, H., Bate, J., Knafo, H., Kinsey, M., Bonuck, K., … Murphy, A. (2014). Looking from the outside in: The use of video in attachment-based interventions. Attachment & Human Development, 16, 402–415.

- Tracey, T. J., & Kokotovic, A. M. (1989). Factor structure of the Working Alliance Inventory. Psychol Assessment: J Consulting Clin Psychol, 1, 207–210.

- Tröster, H., & Brambring, M. (1992). Early social-emotional development in blind infants. Child Care Health Dev, 18, 207–227.

- Van Den Broek, E. G., Van Eijden, A. J., Overbeek, M. M., Kef, S., Sterkenburg, P. S., & Schuengel, C. (2017). A systematic review of the literature on parenting of young children with visual impairments and the adaptions for video-feedback intervention to promote positive parenting (VIPP). Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 1–43. doi:10.1007/s10882-016-9529-6

- Van Duijn, G., Dijkxhoorn, Y., Noens, I., Scholte, E., & Van Berckelaer-Onnes, I. (2009). Vineland Screener 0–12 years research version (NL). Constructing a screening instrument to assess adaptive behaviour. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 18, 110–117.

- Van Zeijl, J., Mesman, J., Van IJzendoorn, M. H., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Juffer, F., Stolk, M. N., … Alink, L. R. A. (2006). Attachment-based intervention for enhancing sensitive discipline in mothers of 1-to 3-year-old children at risk for externalizing behavior problems: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74, 994–1005.

- Vandell, D. L. (1979). Effects of a playgroup experience on mother-son and father-son interaction. Developmental Psychology, 15, 379–385.

- Verhage, M. L., Oosterman, M., & Schuengel, C. (2013). Parenting self-efficacy predicts perceptions of infant negative temperament characteristics, not vice versa. Journal of Family Psychology, 27(5), 844–849.

- Vertommen, H., & Vervaeke, G. A. C. (1990). Werkalliantievragenlijst (WAV). Vertaling voor experimenteel gebruik van de WAI (Dutch translation of the Working Alliance Inventory for experimental use). KU Leuven, Belgium: Non-published questionnaire. Department of Psychology.

- Wakabayashi, A., Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Goldenfeld, N., Delaney, J., Fine, D., … Weil, L. (2006). Development of short forms of the empathy quotient (EQ-Short) and the Systemizing Quotient (SQ-Short). Personal Individ Differ, 41, 929–940.