ABSTRACT

Lacking secure attachment representations is associated with vulnerability to mental and physical health problems, perhaps mediated by increased susceptibility to stress and impaired emotion regulation. Even though cognitive representations of self and others tend to favor confirmation over information, research has shown that adult attachment security can be positively influenced. In a randomized control trial using a mixed between- and within-subjects design, participants (N = 112) were mobile primed with attachment security stimulating visualization tasks, over a 7-day period. Self-reported attachment security was unchanged; however, reduced attachment avoidance and perceived stress and increased resilience and self-compassion scores were obtained up to one week after the last prime. Participants who reported less effort and more pleasure in carrying out the visualization tasks experienced the highest gains. Results highlight the potential of mobile attachment security priming for intervention, but also the differential potential of such intervention for people with different attachment orientations.

Introduction

Attachment security has an expansive power over a person’s lifelong development, impacting on domains of individual functioning such as emotion self-regulation and adaptive coping mechanisms, and is thus associated with either vulnerability to various (mental and physical) health risks or resilience (Shaver & Mikulincer, Citation2010). Knowledge about whether, and how, attachment security can be positively influenced beyond early childhood is thus important. Evidently, the momentary sense of attachment security can be induced by experimental priming, but it is still unclear whether such priming can produce sustained changes (Fraley, Vicary, Brumbaugh, & Roisman, Citation2011; Gillath, Selcuk, & Shaver, Citation2008). In the present study, we explored the effectiveness of location independent (smartphone delivered), repeated attachment security priming via visualization tasks, beyond the point of immediate application.

Attachment security

Adult attachment representations are understood as moderately stable generalizations of early childhood attachment experiences with caregivers (Bowlby, Citation1969, Citation1973), that emerge in interaction with individual temperament and the sociocultural environment (Fraley, Citation2002). Repeated early experiences of supportive caregivers reliably soothing fear, anxiety, and distress contribute to a sense of security, trust that close relationships with other people is valuable (Bowlby, Citation1973; Bretherton & Munholland, Citation2008), and adaptive affect regulation (Lopez & Brennan, Citation2000; Mikulincer & Shaver, Citation2005; Mikulincer, Shaver, & Pereg, Citation2003). Consistently, attachment security is associated with balanced self-representations (e.g. Psouni, Di Folco, & Zavattini, Citation2015) and engagement in constructive coping (Mikulincer, Hirschberger, Nachmias, & Gillath, Citation2001; Psouni & Apetroaia, Citation2014).

By contrast, experiences of unresponsive, unreliable, or unavailable parenting result in strategies characterized by hyper- or deactivation of the attachment system (Ainsworth, Citation1989; Bowlby, Citation1973), that later generalize into patterns of anxious or avoidant behaviors and thinking processes, respectively. In adulthood, individuals high in attachment avoidance tend to distrust relationship partners and strive to maintain emotional distance and independence from others, while individuals high in attachment anxiety worry that relationship partners will not be available in times of need and struggle to maintain proximity to these partners (Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, Citation1998). These patterns of attachment-related avoidance of intimacy, or anxiety regarding being abandoned, tend to be associated with negative outcomes such as low self-esteem and high levels of distress (Maunder, Lancee, Nolan, Hunter, & Tannenbaum, Citation2006), increased susceptibility to burnout (Leiter, Day, & Price, Citation2015; Vanheule & Declercq, Citation2009), and depressive and anxious symptoms (Jinyao et al., Citation2012).

The idea that accessibility to well-organized, implicit knowledge about supportive interactions and affect-regulation strategies facilitates support-seeking and helps maintain emotional balance (Mikulincer, Shaver, Sapir-Lavid, & Avihou-Kanza, Citation2009) is corroborated by neurological evidence (Norman, Lawrence, Iles, Benattayallah, & Karl, Citation2014), while combined fMRI and psychophysiological measures demonstrate that attachment security is correlated with reduced threat-related amygdala activation (Canterberry & Gillath, Citation2013; Lemche et al., Citation2006). According to meta-analytical evidence, attachment security is moderately stable from infancy to adulthood (Fraley, Citation2002; Pinquart, Feußner, & Ahnert, Citation2013), partly because of earlier attachment representations unconsciously guiding attention to relevant, schema-congruent information. At the same time, change over the course of development is theoretically possible, as increasingly diverse attachment-relevant experiences challenge the original attachment model’s validity and initiate processes of re-evaluation and change (Bowlby, Citation1969; Mikulincer & Shaver, Citation2007). Evidently, the strength of attachment security can be influenced by life events (e.g. committing to a steady, supportive relationship; Feeney & Noller, Citation1992) and other contextual factors (Baldwin & Fehr, Citation1995; Gillath et al., Citation2008), but also by the meaning a person assigns to different life events and contexts (Davila & Sargent, Citation2003).

The attachment security priming paradigm

Contextual influences on individual attachment can be illustrated experimentally. Security-related cognitive representations can be activated in a laboratory setup (Mikulincer & Shaver, Citation2015), using words, pictures, or memories associated with the feeling of being loved and supported. These representations can also be influenced by priming methods that experimentally induce specific mental activation. Accordingly, security priming has been shown to increase attachment security (Lin, Enright, & Klatt, Citation2013); improve mood, self-perceptions, and relationship expectations (Carnelley & Rowe, Citation2007); boost energy (Luke, Sedikides, & Carnelley, Citation2012); increase authenticity and reduce dishonesty (Gillath, Sesko, Shaver, & Chun, Citation2010); and moderate emotional responses to stress and trauma (e.g. Mikulincer, Shaver, & Horesh, Citation2006). Meta-analytic data confirm positive, short-term effects of security priming on exam-related anxiety, work performance, attitude towards novelty, outgroup tolerance, aggression, compassion, and altruism (Gillath et al., Citation2008).

Considering duration, positive effects of repeated activation of attachment security representations have been measured from 2 days (Carnelley & Rowe, Citation2007) to 14 days (Sohlberg & Birgegard, Citation2003) post-exposure, fueling discussions of the method’s potential value in treating anxiety and depression (Carnelley, Otway, & Rowe, Citation2015), eating disorders (Dakanalis et al., Citation2014; Tasca & Balfour, Citation2014), post-traumatic stress disorder (Mikulincer & Shaver, Citation2015), and obsessive-compulsive disorder (Doron, Sar-El, Mikulincer, & Talmor, Citation2012). The existing evidence is nevertheless mainly restricted to priming manipulations in the laboratory. Only one study to date has explored repeated security priming location-independently (Otway, Carnelley, & Rowe, Citation2014). After being primed at the laboratory with a 10-minute writing task about a security-enhancing attachment figure on day 1, participants received text messages on the following three days, asking them to recall the feeling related to the attachment figure they initially wrote about. This location-independent priming was associated with increased felt security, but accounted for only 39% of variance in security change. Notably, felt security was operationalized as the extent to which the priming task was perceived as evoking a feeling of security (Otway et al., Citation2014). No attachment variables or other attachment-related mechanisms relevant for mental health were assessed. Importantly, the final assessment was carried out one day after the last prime.

The present study

To further explore the potential usefulness of security priming for clinical intervention, the present study was designed for a real-life context, shifting the focus from immediate effects in the laboratory to sustained changes in daily life. Taking into consideration the habit-forming power of apps and the fact that 79% of smartphone users check their phones within the first 15 minutes after waking up (ICD Research Report, Citation2013), we resolved to further develop the methodology of Otway et al. (Citation2014) and deliver attachment security primes via mobile technologies. Because of a need for testing longer exposure periods (Gillath et al., Citation2008), we employed a week-long priming exposure period. The real-life context for the study made also possible a follow-up of potential effects after the end of priming, through assessments also seven days post-exposure.

The overall aim of the study was to investigate whether an exposure to attachment security primes via smartphone could impact on attachment-related variables crucial for mental and physical health, including attachment security, avoidance and anxiety, and perceived stress. Critically, unlike Otway et al. (Citation2014), our study sought effects on attachment security as operationalized by an attachment self-report measure, hypothesizing that the visualization of positive emotional states related to secure attachment would increase attachment security. Since attachment security is linked to capacity to cope with stress (Bowlby, Citation1969; Fisher, Aron, Mashek, Li, & Brown, Citation2002) and security priming has shown to unfold a stress-reducing effect (e.g. Dandeneau, Baldwin, Baccus, Sakellaropoulos, & Pruessner, Citation2007; Gillath et al., Citation2008; Pierce & Lydon, Citation1998), it was further hypothesized that being exposed to security primes would reduce perceived stress.

Apart from attachment variables and stress perception, we investigated potential effects on two variables known to be related to attachment security. First, we assessed self-compassion, capturing the balanced, non-judgmental awareness of one’s inadequacies and failures (Neff, Citation2003). Self-compassion has been conceptually and empirically linked to attachment security and healthy coping and is increasingly recognized as beneficial in psychotherapy (Barnard & Curry, Citation2011; Joeng et al., Citation2017; Shaver, Mikulincer, Sahdra, & Gross, Citation2016), for instance through decreasing perceived stress and depressive symptoms and increasing resilience and curiosity/exploration (Bluth & Eisenlohr-Moul, Citation2017). Based on meta-analytic evidence of increased self-compassion as a result of self-development or psychotherapeutic intervention (Galla, Citation2016; Gu, Strauss, Bond, & Cavanagh, Citation2015), we hypothesized that it may be open to positive influences also from short-term exposure to attachment security priming. Such effect would be important to document also from a clinical perspective, as increased self-compassion may enhance compliance to challenging intervention (Rowe, Shepstone, Carnelley, Cavanagh, & Millings, Citation2016). Second, we assessed emotional resilience, as it is considered both a precondition and a product of stress perception, appraisal, and coping (Mikulincer & Shaver, Citation2007; Shibue & Kasai, Citation2014). In addition, it has previously been argued that earned attachment security later on in life, for instance through experiences with a supportive partner, may take their expression in heightened levels of self-reported resilience, while other features of the attachment working model may still be suggestive of insecure attachment (Shibue & Kasai, Citation2014). This suggests that potential benefits from security priming may be reflected in increased emotional resilience even in the absence of changes in attachment security.

Method

An experimental mixed between- and within-subjects design (AB/BA, ) was employed, which allowed testing for effects of attachment security priming as independent variable and distinguishing priming from participation effects. Within the course of two weeks, participants were exposed to security primes through visualization tasks on their smartphones, on seven consecutive mornings after waking up. Attachment, perceived stress, self-compassion, and resilience were assessed before and after priming exposure on three occasions (T1, T2, and T3), one week apart from each other. Half of the participants (AB group) were primed between baseline (T1) and second assessment (T2), while the other half (BA) were primed between second (T2) and third (T3) assessment. A planned missing data design was employed, hoping that the reduced burden for participants would result in lower rates of unplanned missing data or dropout and, thereby, increased validity (Little & Rhemtulla, Citation2013). To ensure a valid split of items across the assessments, a pilot study was conducted.

Figure 1. Mixed between- and within-subject design with an assessment period of 17 days. Assessments T1 (Baseline), T2, and T3 were carried out on the same dates for both groups (AB and BA).

Participants

A sample across different age groups, gender, and ethnical backgrounds was recruited. Inclusion criteria were a minimum age of 18, smartphone-use, (self-assessed) proficiency in English, and the motivation and time to engage in the study. In total, 179 participants registered for the study and 131 provided baseline data. Over the course of the study, a dropout of 14.5% reduced the sample to N = 112 (70.5% females, n = 79) with a mean age of 32.5 years (range 18–62 years, SD = 9.8). A majority (n = 76) stated Caucasian ethnicity. Germany (n = 37) and Sweden (n = 36) constituted the main countries of residency. English as native language was spoken by 20.5% (n = 23). Other native languages were German (n = 40), Danish (n = 9), Swedish (n = 6), French (n = 5), and Italian (n = 3). With 67.9% university graduates and 20.5% college graduates, participants in the sample were relatively highly educated. About two-thirds (60.7%, n = 68) stated to be in a committed relationship.

Materials

Primes

Picture-assisted visualization tasks were used, inviting participants to imagine security-related positive emotional states for 2 minutes. These were inspired by similar techniques used in previous studies, for instance asking participants to recall a time when they were part of a group that accomplished a meaningful goal (Gillath, Sesko, Shaver, & Chun, Citation2010; see also by Gillath et al., Citation2008; Mikulincer & Shaver, Citation2007), or think about how a previously described security figure makes them feel safe, secure, and comforted (Otway et al., Citation2014). The visualization tasks were each cued by a picture. Exposure to pictures representing attachment security, asking people to recall or imagine situations of being loved and supported by others has previously shown effective as security prime in the laboratory (see review by Mikulincer & Shaver, Citation2007a). Seven visualization themes and pictures were used, each related to different life situations, in order to increase the chance of priming effectiveness despite participants' individual differences (e.g. relationship status, sexual orientation, previous experiences). Themes depicted a peaceful moment surrounded by family, the connection and support by a close friend, the peace and sense of trust of a playful child, the love of an attentive partner, time spent with a group of close friends, and the empowering feeling of belonging to a team. Instructions were, for example, “Imagine the feeling of … Close your eyes and try to imagine this feeling as detailed as possible. How would you describe it to someone who has never experienced it? Please do that for the next 2 minutes.“ All participants carried out all seven visualization tasks in the same order, one each morning for seven consecutive days.

Attachment security

The Experiences in Close Relationships Questionnaire – Revised (ECR-R; Fraley, Waller, & Brennan, Citation2000) was used as baseline for attachment security. This is a 36-item self-report measure of adult attachment orientation summarized in two dimensions: Avoidance, e.g. “I prefer not showing a partner how I feel inside,” and Anxiety, e.g. “I worry about being abandoned.” Items are responded to on a 7-point Likert-type scale. The anxiety and avoidance sub-scales of the ECR-R comprise distinctive dimensions with high internal reliabilities (.95 and .93, respectively: Sibley, Fischer, & Liu, Citation2005).

To capture temporal fluctuations in felt attachment security, we used the 21-item State Adult Attachment Measure (SAAM; Gillath, Hart, Noftle, & Stockdale, Citation2009), which addresses adult attachment as attachment-related security, anxiety, and avoidance. Items (e.g. “I feel I can trust the people who are close to me”) concern one’s feelings in the present moment and are rated on a 7-point Likert scale. SAAM is related to other attachment style scales with adequate discriminant, convergent, and criterion validity (Gillath et al., Citation2009) as well as incremental validity in predicting psychological well-being and mental health (Trentini, Foschi, Lauriola, & Tambelli, Citation2015), while demonstrating good reliability (internal consistency α = .86 for the security subscale, α = .82 for anxiety, and α = .75 for avoidance: Xu & Shrout, Citation2013).

Perceived stress

Perceived stress was measured with the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, Citation1983). Instead of the original time frame of the past month, we asked for the presence of feelings and thoughts in the past week, to match the study design (one-week exposure and one-week break). Items (e.g. “… how often have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life?”) were rated on a 5-point Likert Scale (1 = never, 5 = very often). While construct validity with other similar measures has been reported between .52 and .76, internal consistencies (α = .84 – .86) and test–retest reliability of .85 are presumed being high (Cohen et al., Citation1983).

Self-compassion

The 12-item short form of Neff, Raes, Pommier, and Van Gucht’s (Citation2011) Self-Compassion Scale (SCS-SF) was used for measuring self-compassion by rating the frequency of six different facets: self-kindness, common humanity, mindfulness as opposed to self-judgment, isolation, and over-identification (e.g. “WhenI’mfeeling down I tend to obsess and fixate on everythingthat’swrong”) in difficult times. With a 5-point Likert response scale (1 = almost never, 5 = almost always), the SCS-SF has shown high internal consistency (α = .87) and good construct validity (Castilho, Pinto-Gouveia, & Duarte, Citation2015; Neff et al., Citation2011). There is some discussion as to whether the scale’s factorial structure reflects one self-compassion factor, as López et al. (Citation2015) found two separate factors, self-compassion and self-criticism, when they used SCS in clinical samples. Following Hayes, Lockard, Janis, and Locke (Citation2016) recommendation for non-clinical samples, we applied here the initial, one-factor structure suggested by the method developers.

Resilience

To assess an individual’s perceived ability to recover from hardships, the 6-item Brief Resilience Scale (BRS; Smith et al., Citation2008, e.g. “I have a hard time making it through stressful events”) was used. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert response scale. A methodological review of 19 resilience scales reported good psychometric properties of the BRS, with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from .70 to .95 and high construct validity (Windle, Bennett, & Noyes, Citation2011).

Evaluation of the study participation

At the end of the final assessment, participants were asked to evaluate and reflect upon the priming experiment, through questions about how they experienced the visualization tasks, e.g. “How did you feel about the imagination tasks? Please rate how much you generally enjoyed visualizing,”1 = didn’tlike it, 5 = enjoyed it a lot; “How much effort was generally necessary for you to engage in a visualization?,”1 = No effort/It was very easy, 5 = Lots of effort/Itwas very difficult. We also asked concerning experiences after the visualization tasks (“Did you experience that your thoughts or feelings returned to a visualization later that day?,” 1 = Never/Very rarely, 5 = Very often/Every day) and concerning expectations (“Do you think the visualizations influenced your thinking or feeling beyond the study?,” 1 = Not at all, 5 = Very much).

Pilot study

To secure an adequate methodological planned missing procedure, a pilot study (N = 66, 78.8% female, mean age Mage = 32.82, SD = 11.44) was conducted in the form of an online questionnaire containing a total of 58 items. Demographics and mean scores were similar to the main study sample. The survey took about 7 minutes to complete. Internal consistency across the three split parts (to be used at T1, T2, and T3, respectively) was above α = .90 for all scales , supporting the split parts’ appropriateness for use in the planned missing procedure.

Table 1. Reliability statistics (Pilot N = 66).

Procedure

The study was titled “ASPS – study about personality and stress-coping”, as complete disclosure of its aim would have risked biased responses (ASPS stands for Attachment Security Priming Study). Participants were recruited via social media over the course of three weeks, mainly through announcements of the study posted on Facebook groups regarding personal development, well-being, physical activity, and music. Facebook promotion tools (advertisements) were also used for spreading the announcement but no specific target group was defined, apart from the requirement of 18 years of age and above. Participants were informed that the data collected via anonymous online participation would be treated confidentially, that no information could directly or indirectly be linked to a living person, that participation was voluntary, and that no questions would be asked in case the participant decided to drop out. As compensation for participation, a choice of gifts (value range 15–100 Euro), ranging from vouchers for personal training or nutrition counseling to jewelry and photography prints, was raffled among participants. After completion of the study, participants were asked to indicate a preferred win, in order to ensure a (geographic) match.

The study was conducted during a 2.5-week period (1+7+1+7+1 days). At day 1, registered participants received instructions and the link to the baseline assessment (T1). Access to the assessment required signed informed consent and the registration of an individual 4-digit code. At the end of the assessment, participants emailed their phone number and current time zone to the study. Participants' contact details were thus never linked to their responses. Participants (phone numbers) were then randomly assigned to either the AB (n = 57) or BA (n = 55) condition. During the following seven days, each morning at 6 am their time-zone, AB participants received a text message linking to the study website, where the day’s security prime visualization task was presented. This choice of time for sending the message maximized the chances that the priming task would be available when the participant woke up, or during the morning routine, without disturbing participants’ sleep. Visual countdown for the duration of the visualization was implemented, in order to promote engagement with the task, and a “Done” button was pressed when finished. The time spent on the task was recorded. BA participants did not receive any message during the first week.

After one week, all participants were sent a link to the second assessment (T2). Then, during the second week, BA participants received text messages introducing a visualization task every morning, while AB participants did not receive any messages. At the end of the second week, all participants received the link to the final assessment (T3). Experiences of the trial were assessed after the final measurements at T3, followed by a more detailed outline of the study aims upon completion.

Data analytic plan

All analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 24). To control that there were no group differences on background factors, MANOVA was conducted with age, gender, English as native language, relationship status, and all baseline measures as dependent variables (DVs), and the manipulation condition (AB vs. BA) as grouping factor. Associations among baseline measures were quantified through regression analysis.

Effects of the attachment security prime exposure were tested between groups (AB, primed between T1 and T2 vs. BA, not primed between T1 and T2), focusing on DV difference scores (T2-T1). For the between-groups comparisons, detecting a change in one of our DVs of about .4 SD (as previously reported in the literature, with SDs also as previously reported, see for instance Otway et al., Citation2014), significant at p = .05 and with an 80% power, would require a minimum of 48 participants in each group. Changes after the week-long priming exposure were also estimated for participants overall, via repeated-measures ANCOVAs comparing post-exposure values (T2 for AB, T3 for BA) to pre-exposure values (T1 for AB, T2 for BA). Detection of .4 SD anticipated changes pre-post exposure, assuming stability in the general population over a week, and with p set at .01 (considering that six DVs were studied and thus six analyses carried out), would require a minimum of 64 participants. Thus, the sample size N = 112 participants (57/55 per group) suggests acceptable power. Effect endurance was estimated on data from the AB group (n = 57), via repeated-measures ANOVA including data before priming (T1), one day after (T2), and one week after (T3), security priming exposure.

In a final, explorative round of analysis, we investigated whether participants’ experience of the priming trial impacted on measured effects. Specifically, we explored whether (a) having enjoyed the attachment-priming visualization tasks, and (b) believing the tasks to influence one’s well-being, accounted for variance in changes in the DVs pre- as compared to post-exposure.

Results

The two groups (AB and BA) did not differ at baseline (). At baseline, higher stress levels were associated with lower self-compassion (r(112) = −.48, p < .0001) and lower resilience scores (r(112) = −.29, p < .01) as well as higher attachment anxiety (r(112) = .37, p < .0001) and higher attachment avoidance (r(112) = .28, p < .01). Together, these variables captured 29.7% of variance in perceived stress at baseline (F(4,107) = 10.38, p < .001, adjR2 = .26). ECR-R anxiety and avoidance scores were highly correlated to the respective SAAM-scales at baseline (for anxiety r(112) = .86 and for avoidance r(112) = .76, both p < .0001), and negatively correlated to SAAM-security (for ECR-R anxiety r(112) = −.38 and for ECR-R avoidance r(112) = −.51, both p < .0001).

Table 2. Group-level values at baseline (T1).

Effects of priming

Between-subjects

No group-level differences were observed in change (T2-T1) in attachment security (F(1,110) = .01, p = .91), attachment anxiety (F(1,110) = .09, p = .76), or attachment avoidance (F(1,110) = .18, p = .67) at the end of the first week. No group-level differences in self-compassion or resilience were found. However, primed participants (AB group) reported more reduced stress post-priming (MDifference T2-T1 = −.48, SD = .84) than participants in the control condition (BA group) (MDifference = -.20, SD = .79), a difference that almost reached significance (F(1,110) = 3.27, p = .07).

Within-subjects

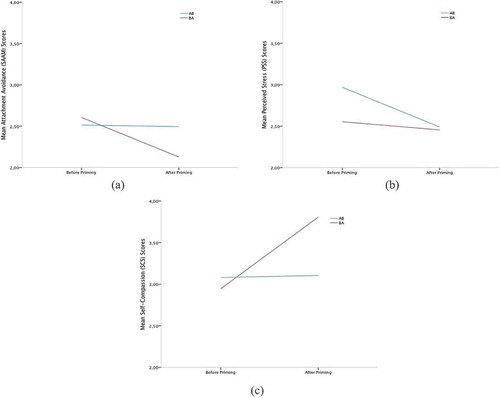

Considering effects of the week-long priming for all participants together (T1-T2 for group AB, T2-T3 for group BA), attachment avoidance scores were lower post-exposure (F(1,110) = 4.68, p = .03). Perceived stress scores dropped, while self-compassion increased (see for unstandardized mean scores, standard deviations and factorial repeated-measures ANOVA results). Group × Time interactions indicate that these changes were contributed by participants in the AB group regarding stress (F(1, 110) = 6.66, p = .011, η2 = .057) and participants in the BA group regarding attachment avoidance (F(1, 110) = 3.94, p = .049, η2 = .035) and self-compassion (F(1, 110) = 4.64, p = .033, η2 = .040). Significant group interactions are illustrated in .

Table 3. Dependent variables pre- and post-exposure: Repeated-measures ANOVA, N = 112.

Effects endurance

The stress-reducing effect in group AB (T2) (F(1,56) = 18.52, p = .0001, η2 = .249) was still significant one week post-exposure, at T3 (F(1, 56) = 18.104, p = .0001, η2 = .244; ). Significantly higher at T3, compared to baseline, were also self-compassion scores (F(1, 56) = 27.05, p = .0001, η2 = .326). The resilience scores that had temporarily dropped immediately after exposure rose significantly during the post-exposure week (F(1,56) = 6.52, p = .013, η2 = .104), to levels above baseline.

Experiences of the trial

The visualization tasks were experienced as moderately to highly pleasant (n = 104, M = 3.38, SD = 1.09). Experiences ranged from positive (e.g. “It gave me a pleasant and warm feeling to start into this day”) to negative (e.g. “It made me think of things Idon’thave right now. It was painful”), with some participants reporting varying (e.g. “Picturing friendship was relaxing, picturingrelationshipand family I got angry and maybe sad”) or indifferent (e.g. “It didn’t change my feelings or actions in any way”) experiences. The effort for engaging in the visualization tasks was described as medium (M = 3.07, SD = 1.23). Experiencing an echo of the priming visualization later that day was occasional (M = 2.25, SD = 1.18) but expectations were mostly positive (M = 2.53, SD = .99), e.g. “feeling more confident during the day when the day starts with positive thoughts.” Group AB (primed during the first week) reported more often than group BA experiences of visualization echo (F(1,102) = 4.96, p = .028).

Pleasure when visualizing was negatively related to baseline (ECR-R) attachment anxiety (r (104) = −.26, p < .01) and attachment avoidance (r (104) = −.20, p < .05). Pleasure and effort of visualizing were negatively correlated (r(104) = −.47, p < .01), and the higher the reported pleasure at the end of the trial, the more the reported echo during the trial (r (104) = .41, p < .01). Reported echo and estimated influence beyond study participation were positively correlated (r (103) = .38, p < .01). The visualizations that were most often stated as particularly resonating (not every participant gave this optional information) were about being loved by an attentive partner (n = 21), the morning after a passionate night (n = 15), spending time with close friends (n = 14), and a peaceful family moment (n = 13).

Finally, the participants’ estimated influence of the security priming beyond the duration of the study correlated with change in perceived stress post-exposure (r(103) = −.35, p < .01), as well as change in attachment anxiety (r(103) = −.28, p < .01) and attachment security (r(103) = .20, p < .05). As experiences of the trial were recorded after all other measurements, at the very end of the last questionnaire, this suggests that the more the participant’s attachment anxiety and perceived stress had decreased, and the more attachment security had increased, the higher the estimated influence retrospectively reported by the participant at the end of the trial.

Discussion

The goal of the present study was to expand prior research on security priming. For the first time, security primes were applied entirely integrated in everyday life, through mobile technologies, and effects and endurance of a week-long exposure period were investigated. Somewhat unexpectedly, the week-long priming exposure did not impact self-reported attachment security or anxiety. However, confirming our hypotheses, visualizing positive attachment security situations for seven consecutive days resulted in reduced self-reported attachment avoidance and reduced perceived stress and increased self-compassion, assessed one day after the week-long exposure. The effects on stress and self-compassion persisted one week after the end of the priming. Importantly, positive effects of attachment priming were stronger for participants who found it easier to engage in the visualization tasks.

Attachment-priming effect on stress, self-compassion, and resilience

Confirming our hypothesis, participants reported lower levels of stress one day after the week-long daily attachment priming, while self-compassion increased, consistent with previous findings on stress (e.g. Dandeneau et al., Citation2007; Gillath et al., Citation2008; Pierce & Lydon, Citation1998), and attitude towards oneself (e.g. Rowe et al., Citation2016; Shaver & Mikulincer, Citation2009; Shaver et al., Citation2016). These changes seem particularly relevant, as self-compassion together with attachment anxiety accounted for almost 30% of stress levels at baseline, reflecting an interconnectedness of attachment, self-compassion, and stress perception consistent with what is reported in the literature (e.g. Rowe et al., Citation2016). Given that these effects were still present eight days after the week-long daily attachment priming, stress perception and self-compassion may hold the potential of an accelerator for prime-induced change in attachment-related cognition.

Changes in self-reported stress and self-compassion were partly dependent on participants’ experiences of the visualization tasks as disclosed at the end of the study. The higher the participant’s estimate of positive influence of the visualization tasks at the very end of the trial, the more their attachment anxiety and stress scores had actually decreased, and attachment security scores increased. Importantly, influence estimates were higher when participants had experienced the visualization tasks to be easy and enjoyable, and when they had experienced the visualization tasks echoing throughout the day. Thus, it seems that the effects of the priming technique applied in this study cannot be evaluated independently from participants’ subjective experiences of the visualizations, and their influence estimates. The analysis of group (AB vs. BA) comparisons revealed also that resilience scores were highest and avoidance scores lowest at the end of the second half of the study (T3), for both groups, despite the fact that group AB was primed between T1 and T2, while group BA was primed between T2 and T3. These patterns raise suspicion of a general participation effect, consistent with suggestions by McCambridge, Kypri, and Elbourne (Citation2014).

Attachment priming and reported attachment security

The attachment-priming procedure in the present study resulted in decreased attachment avoidance scores post-exposure, unlike previous findings (e.g. Carnelley & Rowe, Citation2007; Lin et al., Citation2013). As a defense mechanism beyond individual awareness, attachment avoidance has been regarded as more difficult to influence through security priming (Mikulincer & Shaver, Citation2007). However, our findings suggest that repetitive (week-long) priming may in fact lead to decreased self-reported attachment avoidance measured one day after priming was terminated. Notably, the security priming used in our experiment comprised rather diverse visualization task stimuli. The fact that only two out of seven visualization themes were clearly linked to romantic relationships (while other stimuli primed positive emotional states related to friends, family, and being a child) may have reduced the subconscious perception of threat by individuals high in avoidance, therefore eliciting a reduction of avoidant tendencies. The decrease in self-reported avoidance is an encouraging finding, although it must be noted that it did not last beyond the exposure week, as values had returned to baseline levels one week after termination of the priming procedure, consistently with previous evidence that intervention-induced changes related to attachment may be transient (Fraley, Citation2002).

Unexpectedly, there was no change in self-reported attachment security one day after week-long, daily attachment priming was terminated. Although this seems somewhat inconsistent with previously reported findings (Otway et al., Citation2014), it is important to distinguish between increased felt security (as in Otway et al., Citation2014), which concerns whether a specific priming task increased a participant’s momentary feeling of security (e.g. “Thinking about that person made me feel secure”), and increased self-reported attachment security as state, which concerns generalized, task-independent thoughts and feelings towards others (e.g. “I feel secure and close to other people”). From a theoretical point of view, attachment security is more than the absence of insecure strategies (Mikulincer & Shaver, Citation2007). While both attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety are associated with worry about relation to others, and applied strategies are meant to deal with fear of too much or too little proximity, respectively, attachment security represents a resource that is continually nourished by positive interactions with significant others (Bowlby, Citation1969). It seems logical that, for insecurely attached individuals, strengthening a secure base schema may become possible when the need for defensive strategies becomes less present. Hence, a reduction of avoidant and/or anxious thoughts and feelings may be a prerequisite for an increase in reported attachment security. The decrease in avoidance scores directly after the week-long priming and increase in attachment scores during the week following the termination of priming, as observed in the present study, may thus be regarded as a valuable starting point towards less transient influences in the degree of attachment security.

Although it has been suggested that security priming effects are independent from dispositional attachment (Carnelley & Rowe, Citation2007; Gillath et al., Citation2008; Otway et al., Citation2014), our results suggest that there may be differences in the effectiveness of different primes for individuals with different attachment styles. For example, for individuals with no access to a secure model, or for whom the status of being single is painful, priming with symbols of a secure relationship situation may have a negative impact (Lutz et al., Citation2003). Indeed, our results suggest that attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance at baseline was associated with difficulty in carrying out the visualization tasks retrospectively reported at the end of the two-week trial, and no expectation that the task would have an impact over time, which in turn was associated with less measured impact. It is thus no surprise that no effect on attachment anxiety was observed in the present sample. These findings are consistent with the suggestion that anxiety and avoidance moderate the effects of explicit security priming (Mikulincer, Shaver, & Rom, Citation2011) and emphasize the importance of refining priming methods to increase such desired differentiation for different groups. Notably, priming studies who have reported positive effects on attachment security and anxiety used writing narratives that elicited personalized security primes (e.g. Carnelley & Rowe, Citation2007; Otway et al., Citation2014), and subsequent priming was based on recalling the feeling associated with the narrative, ensuring high personal relevance of the prime.

The present study design enabled a follow-up of effects for longer periods after the priming exposure than usually assessed, with important insights. The data eight days after the week-long daily priming exposure (T3) showed that the initially reduced attachment avoidance one day post-exposure (T2) soared between T2 to T3 to levels comparable to baseline. Hence, in the present study, a backlash effect appears to follow a positive short-term effect of priming on attachment-related variables, as previously also noted by Fraley (Citation2002). This could be an indication that prime-induced change requires a certain time to become more long-term accessible. Similarly to Lewandowsky, Ecker, Seifert, Schwarz, and Cook (Citation2012) description of mechanisms why efforts to correct misinformation can backfire and ironically increase misbelief, the provision of secure-base information may have to reach a certain ratio of all processed information (which is only partly insecure-base confirming), in order to initiate sustainable change in attachment orientation.

Limitations

The particulars of the study sample pose some limitations to generalizability. First, the study participants were volunteers, and it cannot be excluded that they may have had increased interest in stress reduction techniques and their workings. Second, the sample was not balanced across genders, as almost three-quarters of participants identified themselves as female. Third, in contrast to studies by Carnelley and Rowe (Citation2007), in which all participants in the secure prime condition had a steady romantic partner, being committed to a relationship was true for only one-third of participants in the present sample. Finally, several participants were not native English speakers (the study’s language of instruction). Previous security priming studies did not control for their participants’ native language, but in the present study we controlled for whether participants had English as native language or not, in all analyses. Surprisingly, despite previous evidence of a foreign language effect in aspects potentially relevant for attachment mechanisms, such as the expression of emotions (e.g. Pavlenko, Citation2005; Wilson, Citation2013), we found no impact of English as native language on changes in the study-dependent variables, possibly because the level of the participants’ proficiency in English language was high. However, future research ought to control for this factor more stringently.

Bringing security priming to everyday life comes with inevitable methodological hurdles. It was technically not possible to secure that the priming task, which was sent to all participants at exactly the same time in the morning, was also received at that time. Different operating systems of individual devices may have influenced the exact layout of the visualization countdown. Nor was it possible to control for features in the context in which the visualizations were carried out (interfering noises, interruptions). As it seems crucial to consider individual evaluations of the intervention, future research should explore preferences in the degree of guidance of the visualization and customized timing (taking into consideration exact waking-up times). For a rigorous test of the priming visualization tasks, a future study could deliver a set of neutral visualization primes to the control group, instead of no prime. Customized primes could increase the fit between prime and participant and reduce the risk of eliciting negative feelings in association with a particular prime. Further exploring the endurance of attachment security priming changes could also involve combining self-report with physiological methods during follow up.

Finally, to account for the threat of validity when measuring psychological change, a planned missing data design was applied, trying to keep reactive response bias as low as possible. Splitting the original scales rather than using them complete at all three measurement points helped to avoid fatigue effects, as the questionnaires otherwise would have been very long, and memory effects, as the assessments were only one week apart. In the present study, we obtained very high internal consistencies across the splits. Expanding on this promising feature, improved planned missing data designs could be attempted in future studies, such as multiform designs, which involves randomly assigning participants to have missing items on a survey, or wave missing designs, which involves missing selected measurement occasions in the longitudinal design (Little & Rhemtulla, Citation2013).

Conclusions

The repeated activation of cognitive representations of attachment security seems capable of inducing enduring beneficial effects on attachment-related variables and, possibly, even on the accessibility of secure attachment representations themselves. However, as attachment patterns represent automatic affect regulation tendencies (Carnelley & Rowe, Citation2007; Mikulincer et al., Citation2003) and investigations of security priming in naturalistic settings are scarce, techniques aiming at sustainable changes in adult attachment insecurity require further systematic research. Through features such as customization potential and location-independent integration in daily life, mobile technologies offer new opportunities for positively influencing individual behavior (Fiordelli, Diviani, & Schulz, Citation2013). Being discussed as the future of mental health provision (Hides, Citation2014), these opportunities come along with a clear need for data safety and scientific validation (Donker et al., Citation2013; Luxton, McCann, Bush, Mishkind, & Reger, Citation2011).

Our design tested the suitability of a mobile application that integrated seven consecutive priming trials in everyday life, explored longer effect endurance and allowed for differentiating priming from general participation effects. The planned missing feature secured low drop out over the course of two weeks, suggesting good compliance while most participants experienced the participation as positive. With this study, we could show that a period of seven days of visualizations could reduce stress and strengthen a sense of self-compassion up to eight days after priming exposure. The week-long exposure resulted also in decrease in attachment avoidance. The findings of this study and the opportunities of mobile applications suggest great potential of mobile security priming for sustainable change in attachment-related mechanisms.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ainsworth, M. D. (1989). Attachments beyond infancy. The American Psychologist, 44(4), 709–716.

- Baldwin, M. W., & Fehr, B. (1995). On the instability of attachment style ratings. Personal Relationships, 2, 247–261.

- Barnard, L. K., & Curry, J. F. (2011). Self-compassion: Conceptualizations, correlates, & interventions. Review of General Psychology, 15(4), 289–303.

- Bluth, K., & Eisenlohr-Moul, T. A. (2017). Response to a mindful self-compassion intervention in teens: A within-person association of mindfulness, self-compassion, and emotional well-being outcomes. Journal of Adolescence, 57, 108–118.

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss. Attachment (Vol. 1, 2nd ed.). New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss: Vol. 2. Separation: Anxiety and anger. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson, W. S. Rholes, J. A. Simpson, & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 46–76). New York, NY, US: Guilford Press.

- Bretherton, I., & Munholland, K. A. (2008). Internal working models in attachment relationships: Elaborating a central construct in attachment theory. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications, 2nd ed (pp. 102–127). New York, NY, US: Guilford Press.

- Canterberry, M., & Gillath, O. (2013). Neural evidence for a multifaceted model of attachment security. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 88(3), 232–240.

- Carnelley, K. B., Otway, L. J., & Rowe, A. C. (2015). The effects of attachment priming on depressed and anxious mood. Clinical Psychological Science, 4(3), 1–58. doi:10.1177/2167702615594998

- Carnelley, K. B., & Rowe, A. C. (2007). Repeated priming of attachment security influences later views of self and relationships. Personal Relationships, 14(2), 307–320.

- Castilho, P., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Duarte, J. (2015). Evaluating the multifactor structure of the long and short versions of the self-compassion scale in a clinical sample. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 71(9), 856–870.

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396.

- Dakanalis, A., Timko, C. A., Zanetti, M. A., Rinaldi, L., Prunas, A., Carà, G., … Clerici, M. (2014). Attachment insecurities, maladaptive perfectionism, and eating disorder symptoms: A latent mediated and moderated structural equation modeling analysis across diagnostic groups. Psychiatry Research, 215(1), 176–184.

- Dandeneau, S. D., Baldwin, M. W., Baccus, J. R., Sakellaropoulo, M., & Pruessner, J. C. (2007). Cutting stress off at the pass: Reducing vigilance and responsiveness to social threat by manipulating attention. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 93(4), 651–666.

- Davila, J., & Sargent, E. (2003). The meaning of life (events) predicts changes in attachment security. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(11), 1383–1395.

- Donker, T., Petrie, K., Proudfoot, J., Clarke, J., Birch, M., & Christensen, H. (2013). Smartphones for smarter delivery of mental health programs: A systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(11), e247.

- Doron, G., Sar-El, D., Mikulincer, M., & Talmor, D. (2012). Experimentally-enhanced attachment security influences obsessive compulsive related washing tendencies in a non-clinical sample. E-Journal of Applied Psychology, 8(1), 1–8.

- Feeney, J. A., & Noller, P. (1992). Attachment style and romantic love: Relationship dissolution. Australian Journal of Psychology, 44(2), 69–74.

- Fiordelli, M., Diviani, N., & Schulz, P. J. (2013). Mapping mhealth research: A decade of evolution. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(5), e95.

- Fisher, H. E., Aron, A., Mashek, D., Li, H., & Brown, L. L. (2002). Defining the brain systems of lust, romantic attraction, and attachment. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 31(5), 413–419.

- Fraley, R. C. (2002). Attachment stability from infancy to adulthood: Meta-analysis and dynamic modeling of developmental mechanisms. Personality & Social Psychology Review, 6(2), 123–151.

- Fraley, R. C., Vicary, A. M., Brumbaugh, C. C., & Roisman, G. I. (2011). Patterns of stability in adult attachment: An empirical test of two models of continuity and change. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 101(5), 974–992.

- Fraley, R. C., Waller, N. G., & Brennan, K. A. (2000). An item-response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 350–365. doi:10.1037/a0022898

- Galla, B. M. (2016). Within-person changes in mindfulness and self-compassion predict enhanced emotional well-being in healthy, but stressed adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 49, 204–217.

- Gillath, O., Hart, J., Noftle, E. E., & Stockdale, G. D. (2009). Development and validation of a state adult attachment measure (SAAM). Journal of Research in Personality, 43(3), 362–373.

- Gillath, O., Selcuk, E., & Shaver, P. R. (2008). Moving toward a secure attachment style: Can repeated security priming help? Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(4), 1651–1666.

- Gillath, O., Sesko, A. K., Shaver, P. R., & Chun, D. S. (2010). Attachment, authenticity, and honesty: Dispositional and experimentally induced security can reduce self- and other-deception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(5), 841–855. doi:10.1037/a0019206

- Gillath, O., Sesko, A. K., Shaver, P. R., & Chun, D. S. (2010). Attachment, authenticity, and honesty: Dispositional and experimentally induced security can reduce self- and other-deception. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 98(5), 841–855.

- Gu, J., Strauss, C., Bond, R., & Cavanagh, K. (2015). How do mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction improve mental health and wellbeing? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 37, 1–12.

- Hayes, J. A., Lockard, A. J., Janis, R. A., & Locke, B. D. (2016). Construct validity of the self-compassion scale-short form among psychotherapy clients. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 5070(April), 0–18.

- Hides, L. (2014). Are SMARTapps the future of youth mental health? InPsych, 36(3). APS Australian Psychological Association. Retrieved from www.psychology.org.au/inpsych/2014/june/hides/

- ICD Research Report. (2013). Always connected. How smartphones and social keep us engaged. Retrieved from www.nu.nl/files/IDC-FacebookAlwaysConnected(1).pdf

- Jinyao, Y., Xiongzhao, Z., Auerbach, R. P., Gardiner, C. K., Lin, C., Yuping, W., & Shuqiao, Y. (2012). Insecure attachment as a predictor of depressive and anxious symptomology. Depression & Anxiety, 29(9), 789–796.

- Joeng, J. R., Turner, S. L., Kim, E. Y., Choi, S. A., Lee, Y. J., & Kim, J. K. (2017). Insecure attachment and emotional distress: Fear of self-compassion and self-compassion as mediators. Personality & Individual Differences, 112, 6–11.

- Leiter, M. P., Day, A., & Price, L. (2015). Attachment styles at work: Measurement, collegial relationships, and burnout. Burnout Research, 2(1), 25–35.

- Lemche, E., Giampietro, V. P., Surguladze, S. A., Amaro, E. J., Andrew, C. M., Williams, S. R., … Phillips, M. L. (2006). Human attachment security is mediated by the Amygdala: Evidence from combined fMRI and psychophysiological measures. Human Brain Mapping, 27(8), 623–635.

- Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H., Seifert, C. M., Schwarz, N., & Cook, J. (2012). Misinformation and its correction. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13(3), 106–131.

- Lin, W. N., Enright, R. D., & Klatt, J. S. (2013). A forgiveness intervention for taiwanese young adults with insecure attachment. Contemporary Family Therapy, 35(1), 105–120.

- Little, T. D., & Rhemtulla, M. (2013). Planned missing data designs for developmental researchers. Child Development Perspectives, 7(4), 199–204.

- López, A., Sanderman, R., Smink, A., Zhang, Y., Eric, V. S., Ranchor, A., & Schroevers, M. J. (2015). A reconsideration of the self-compassion scale’s total score: Self-compassion versus self-criticism. PLoS ONE, 10(7), 1–13.

- López, F. G., & Brennan, K. A. (2000). Dynamic processes underlying adult attachment organization: Toward an attachment theoretical perspective on the healthy and effective self. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47(3), 283–300.

- Luke, M. A., Sedikides, C., & Carnelley, K. (2012). Your love lifts me higher! The energizing quality of secure relationships. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(6), 721–733.

- Lutz, C. J., Cohen, J. L., Neely, L. C., Baltman, S., Schreiber, S., & Lakey, B. (2003). Context-induced contrast and assimilation in judging supportiveness. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology, 22(4), 441–462.

- Luxton, D. D., McCann, R. A., Bush, N. E., Mishkind, M. C., & Reger, G. M. (2011). mHealth for mental health: Integrating smartphone technology in behavioral healthcare. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 42(6), 505–512.

- Maunder, R. G., Lancee, W. J., Nolan, R. P., Hunter, J. J., & Tannenbaum, D. W. (2006). The relationship of attachment insecurity to subjective stress and autonomic function during standardized acute stress in healthy adults. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 60(3), 283–290.

- McCambridge, J., Kypri, K., & Elbourne, D. (2014). Research participation effects: A skeleton in the methodological cupboard. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(8), 845–849.

- Mikulincer, M., Hirschberger, G., Nachmias, O., & Gillath, O. (2001). The affective component of the secure base schema: Affective priming with representations of attachment security. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 81(2), 305–321.

- Mikulincer, M., Shaver, P., & Pereg, D. (2003). Attachment theory and affect regulation: The dynamics, development, and cognitive consequences of attachment-related strategies. Motivation and Emotion, 27(2), 77.

- Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2005). Attachment theory and emotions in close relationships: Exploring the attachment-related dynamics of emotional reactions to relational events. Personal Relationships, 12(2), 149–168.

- Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2007). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. New York, NY: The Guilford. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

- Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2015). The psychological effects of the contextual activation of security-enhancing mental representations in adulthood. Current Opinion in Psychology, 1, 18–21.

- Mikulincer, M., Shaver, P. R., & Horesh, N. (2006). Attachment bases of emotion regulation and posttraumatic adjustment. In D. K. Snyder, J. A. Simpson, & J. N. Hughes (Eds.), Emotion regulation in families: Pathways to dysfunction and health (pp. 77–99). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Mikulincer, M., Shaver, P. R., & Rom, E. (2011). The effects of implicit and explicit security priming on creative problem solving. Cognition & Emotion, 25(3), 519–531.

- Mikulincer, M., Shaver, P. R., Sapir-Lavid, Y., & Avihou-Kanza, N. (2009). What’s inside the minds of securely and insecurely attached people? The secure-base script and its associations with attachment-style dimensions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(4), 615–633.

- Neff, K. D. (2003). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity., 2(3), 223–250.

- Neff, K. D., Raes, F., Pommier, E., & Van Gucht, D. (2011). Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the self-compassion scale. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 18, 250–255.

- Norman, L., Lawrence, N., Iles, A., Benattayallah, A., & Karl, A. (2014). Attachment-security priming attenuates amygdala activation to social and linguistic threat. Social Cognitive & Affective Neuroscience, 10, 832–839.

- Otway, L. J., Carnelley, K. B., & Rowe, A. C. (2014). Texting “boosts” felt security. Attachment & Human Development, 16(1), 93–101.

- Pavlenko, A. (2005). Emotions and multilingualism. Cambridge. Cambridge: University Press.

- Pierce, T., & Lydon, J. (1998). Priming relational schemas: Effects of contextually activated and chronically accessible interpersonal expectations on responses to a stressful event. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(6), 1441–1448.

- Pinquart, M., Feußner, C., & Ahnert, L. (2013). Meta-analytic evidence for stability in attachments from infancy to early adulthood. Attachment & Human Development, 15(2), 189–218.

- Psouni, E., & Apetroaia, A. (2014). Measuring scripted attachment-related knowledge in middle childhood: The secure base script test. Attachment & Human Development, 16(1), 22–41.

- Psouni, E., Di Folco, S., & Zavattini, G. C. (2015). Scripted secure base knowledge and its relation to perceived social acceptance and competence in early middle childhood. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 56(3), 341–348.

- Rowe, A. C., Shepstone, L., Carnelley, K. B., Cavanagh, K., & Millings, A. (2016). Attachment security and self-compassion priming increase the likelihood that first-time engagers in mindfulness meditation will continue with mindfulness training. Mindfulness. doi:10.1007/s12671-016-0499-7

- Shaver, P. R., & Mikulincer, M. (2009). Attachment styles. In Leary, M. R., & Hoyle, R. H. (Eds.), Handbook of individual differences in social behavior (pp. 62–81). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Shaver, P. R., & Mikulincer, M. (2010). New directions in attachment theory and research. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27(2), 163–172.

- Shaver, P. R., Mikulincer, M., Sahdra, B., & Gross, J. (2016). Attachment security as a foundation for kindness toward self and others. In The Oxford handbook of hypo-egoic phenomena (Vol. 1). Oxford Handbooks Online. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199328079.013.15

- Shibue, Y., & Kasai, M. (2014). Relations between attachment, resilience, and earned security in Japanese University students. Psychological Reports, 115(1), 279–295.

- Sibley, C. G., Fischer, R., & Liu, J. H. (2005). Reliability and validity of the revised experiences in Close Relationships (ECR-R) self-report measure of adult romantic attachment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 1524–1536. doi:10.1177/0146167205276865

- Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., & Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(3), 194–200.

- Sohlberg, S., & Birgegard, A. (2003). Persistent complex subliminal activation effects: First experimental observations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 302–316.

- Tasca, G. A., & Balfour, L. (2014). Attachment and eating disorders: A review of current research. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47(7), 710–717.

- Trentini, C., Foschi, R., Lauriola, M., & Tambelli, R. (2015). The State Adult Attachment Measure (SAAM): A construct and incremental validity study. Personality and Individual Differences, 85, 251–257.

- Vanheule, S., & Declercq, F. (2009). Burnout, adult attachment and critical incidents: A study of security guards. Personality and Individual Differences, 46(3), 374–376.

- Wilson, R. (2013). Another language is another soul. Language and Intercultural Communication, 13(3), 298–309.

- Windle, G., Bennett, K. M., & Noyes, J. (2011). A methodological review of resilience measurement scales. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 9(1), 8.

- Xu, J. H., & Shrout, P. E. (2013). Assessing the reliability of change: A comparison of two measures of adult attachment. Journal of Research in Personality, 47(3), 202–208.