ABSTRACT

This paper prospected the evidence synthesized in meta-analyses on child–parent attachment to discuss its implications for the future of attachment research. Based on the 75 identified meta-analyses, effect size benchmarks may need to be adjusted to small (r = .10), medium (r = .20), and large (r = .30). Topics of attachment meta-analyses predominantly (53%) reflected interest in testing theory. Bibliometric analysis of scientific publications (k = 7,595) that cited these meta-analyses reflect waxing uptake in work on interventions, mental health, and attachment anxiety/avoidance and waning uptake in work on attachment relationships and representations, except for the subtopics of sensitivity and fathers. Prospects for scientifically rigorous research are to be found in engagement with stakeholders working to address important societal challenges. Promoting nurturing care and reducing harm in child welfare contain “Goldilocks-problems” that are amenable to incremental progress while simultaneously advancing theory and methods.

To prospect something is to consider its existing resources in terms of their potential contribution to the future. Following in the footsteps of Mary Ainsworth, attachment research has been oriented by a concern to contribute to and achieve recognition within academic psychology (Duschinsky, Citation2020). At times, this may have aligned with, but at other times may have come at the cost of, engagement with citizens, professionals, and policymakers to set the agenda of research. This concern prompted us to prospect attachment research, to consider its existing resources and their potential scientific and societal yield.

Prospecting a field of scientific inquiry could begin with surveying the terrain that has been covered by research, an assessment of the value of its findings, and a discussion of implications for the approach in our field within the current societal and scientific context. Recently, Duschinsky (Citation2020) offered one perspective on this future, considered particularly in terms of theoretical and methodological developments at key laboratories that laid the ground for work to come. However, the field has also quantitatively synthesized attachment research through meta-analyses, and these syntheses and their impact on the field may also provide quantitative data points that can be extrapolated into the years to come. Van IJzendoorn was an early adopter of the methodology within and outside the field of attachment, influenced by Karl Popper’s emphasis on the need for replication as the basis of surety in science (Van IJzendoorn, Citation1994). Both to provide such surety, and to examine explanations for different outcomes among studies, meta-analysis became an important instrument to represent empirical evidence and identify empirical and theoretical gaps. The method has since been adopted by numerous other authors in the field. Collectively, these meta-analyses reflect, on the one hand, the research topics which have received repeated interest from attachment researchers and, on the other hand, provide authoritative summaries (relative to single primary studies) informing scientific and societal issues. These meta-analyses and also the effect sizes reported therein have guided researchers in deciding which effects would be worthwhile and feasible to study.

The first aim of this paper is therefore to map the meta-analytic work on attachment as well as synthesize the distribution of effect sizes that these meta-analyses have reported. The second aim of this paper was to characterize the relevance of meta-analyzed evidence by describing the focus of scientific publications that build upon this evidence and examine how citation patterns have changed over time. The third aim of this paper was to draw from the paper’s bibliometric findings and Duschinsky’s sociological reflections (Duschinsky, Citation2020; Duschinsky et al., Citation2021) some proposals about how attachment researchers might optimize their orientation towards relevant societal contributions.

Meta-analyses of child attachment research

To achieve the first aim of the paper, we set the scope of our description and analysis of attachment meta-analyses to the corpus of meta-analyses that synthesized descriptives or effect sizes based on attachment assessment with children (up to age 18) and their caregivers, across the field of psychology. First, from the main effect sizes reported in these meta-analyses we derive field-specific effect-size benchmarks (Funder & Ozer, Citation2019). Such benchmarks, if used with caution (see Kvarven et al., Citation2020), may inform the planning and design of future studies. Second, we summarize the topics of meta-analyses of attachment research, in order to obtain an overall impression of the focus of the work.

Retrieval of meta-analyses of developmental attachment research

Eligibility criteria

Publications were selected if these: (1) presented the original report of meta-analyses to quantitatively synthesize research findings, (2) reported on attachment-theoretical constructs (e.g. attachment behavior, attachment relationships, attachment representations), (3) reported on research with children (until age 18), and (4) were published in the field of psychology.

Retrieval and eligibility assessment

Query strings (Supplemental Material Appendix A) were entered on 9 June 2019 in the bibliographic databases of Scopus and Web of Science, which provide ongoing coverage of the large majority of international peer reviewed journals in the field of psychology. Records retrieved (Web of Science: number of studies k = 159; Scopus: k = 156) were exported (Web of Science: tab-delimited; Scopus: csv-format) to Endnote to remove duplicates, after which k = 208 records remained. Two of the authors (CS and MLV) independently coded the titles and abstracts on eligibility criteria 1–3, turning to the full manuscript if information was missing or unclear. One publication was not considered eligible because it was published only as a conference abstract. provides the PRISMA flow diagram for the study selection and results.

Extracting meta-analytic effect sizes and heterogeneity

We took a stepped approach to extracting the effect sizes of the meta-analyses. First, we identified the key attachment-related research question into effects of attachment or associations with attachment from the abstract and the title. In the case of multiple key research questions, the first one of these questions was selected, assuming that usually, the most important question comes first. Second, the first effect size that unambiguously answered that key research question in the Results section was recorded for that meta-analysis. If no effect size could be found, we proceeded with the next key research question until an effect size could be recorded. Meta-analyses reporting only proportions (i.e. the prevalence of classifications) were excluded. Third, heterogeneity of the effect sizes was recorded based on the I2 or Q statistic reported for the chosen effect size in the meta-analysis or based on the description of the effect as homogeneous or heterogeneous. If this information was not available, we assumed heterogeneity when moderators of the effect size were tested. Finally, effect sizes were converted into effect size metric Pearson r and recoded to reflect positive directionality for comparison. If conversion into r was not possible (e.g. due to missing information needed for the conversion), the effect size was excluded from these analyses. Full details of effect size extractions can be found in the protocol (https://osf.io/hxez2/).

Categorization of meta-analytic topics

A bottom-up approach was used to arrive at categories for the main research aims of meta-analyses on attachment research. First, CS read the titles of the meta-analyses retrieved at step 1. This led to formulating four provisional categories for the primary aims. Second, CS and MLV read the abstracts and if needed the Introduction sections of each meta-analysis to classify the aims of each meta-analytic review in one or more of these four categories. Discussion of discrepancies (k = 13; 83% agreement) led to slight reformulation into the categories reported below.

Findings

Benchmarking meta-analytic attachment effect sizes

Retrieval and coding led to the identification of 75 meta-analyses (see supplemental material Table S1 for overview). Publication rate showed exponential growth up to and including 2018 (Supplemental Material Figure S1). shows the distribution of the 64 main effect sizes that could be extracted from these meta-analyses (for an overview per meta-analysis, see Table S1). In interpreting the descriptive statistics on this set of effect sizes, it should be kept in mind that these effect sizes represent, to an unknown degree, overlapping primary level effect sizes, for instance, when meta-analyses on the same research question were repeated. The unweighted mean based on absolute effect sizes was r = .23, median r = .20, and the range was between .01 and .99. This latter extreme effect size was obtained for the still face effect. The 25th percentile was r = .13 and the 75th percentile .30. Only 28% of tested effect sizes were reported to be homogeneous, underlining the caution that needs to be exercised when using meta-analytic effect sizes for the planning of new studies, because corrections for small sample bias are unreliable under conditions of high heterogeneity (Ioannidis & Trikalinos, Citation2007). Distribution of these homogeneous effect sizes was largely similar to the overall set, with an unweighted mean based on absolute effect sizes r = .20, median r = .17, a range between .01 and .72, 25th percentile of r = .04, and the 75th percentile r = .26. This distribution of effect sizes reported in attachment meta-analyses appears remarkably similar to the distribution of effect sizes in social psychological studies (mean r = .21; Richard et al., Citation2003), personality studies (mean r = .21; Fraley & Marks, Citation2007), social and personality psychology together (mean r = .19; 25th percentile r = .11 and 75th percentile r = .29; Gignac & Szodorai, Citation2016), and individual differences studies in gerontology (25th percentile r = .12; median r = .20; and 75th percentile r = .32; Brydges, Citation2019). Even without taking into account that meta-analysis may overestimate the actual effect size due to selective non-reporting (Kvarven et al., Citation2020), planning studies with sufficient statistical power (conventionally 80%) for testing with 95% confidence (two-sided) a typical effect size in attachment research (r = .20) would require a sample of at least 193 participants.

Trends in meta-analytic topics

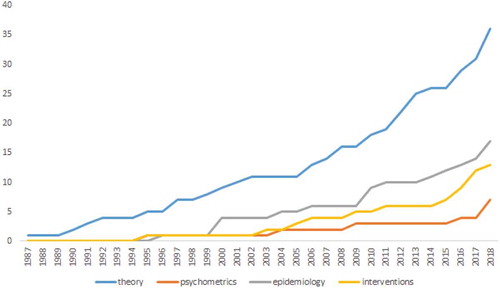

The meta-analyses can be distinguished into those aimed (1) to test phenomena and mechanisms in the Bowlby-Ainsworth attachment theory and its extensions (e.g. testing propositions about the link between parenting and attachment, or between attachment and developmental outcomes); (2) to test the psychometric quality of attachment assessments (e.g. reliability and validity of attachment instruments); (3) to describe the epidemiology of individual differences in attachment (e.g. describing prevalences across populations); and (4) to test effects of interventions on individual differences in attachment (e.g. efficacy of attachment-based interventions). shows cumulative trends over time (1987–2018) in these aims. While the period from 1987 when the first attachment meta-analysis was published until 1999 reveals an exclusive focus on testing and elaborating attachment theory, from 2004 on largely stable proportions can be seen of published meta-analyses with theoretical aims (53%), psychometric aims (8%), epidemiological aims (24%), and aims related to intervention (15%).

Trends in scientific impact of attachment meta-analyses

The scientific impact of the evidence consolidated in attachment meta-analyses may be gauged through the scientific publications that refer to this body of work. The content of these publications reflect scientific interests within or related to the scope of attachment theory. First, we describe the academic work that has cited attachment meta-analyses and the trends therein, as citation volume and trends are broadly accepted gauges of scientific impact (Waltman et al., Citation2010). Second, we extracted the topics and themes of the publications that have been citing attachment meta-analyses and mapped the structure of the network of publications based on the similarity of terms used in these publications. Networks and clusters thus constructed are an outward manifestation of researchers focusing on similar topics, using similar conceptual frameworks or methods, or coordinating their efforts in visible or invisible ways. Here, the focus was on the research fields in which there is interest in the evidence consolidated in these meta-analyses and on gauging the extent to which the interest from these fields is waxing or waning.

Retrieval of studies citing meta-analyses

Eligibility criteria

Publications were selected if these: (1) cited one or more of the meta-analyses identified in the previous section (as per the goal of the study), (2) had full bibliographic records electronically available with title, author list, publication year, abstract, keywords, and reference list (to provide the data necessary for science mapping analysis), which limited the search to journal articles.

Retrieval

The meta-analyses (k = 75) retrieved in step 1 were searched in Scopus to identify citing references. Records retrieved (k = 7,595) were exported to a publication database.

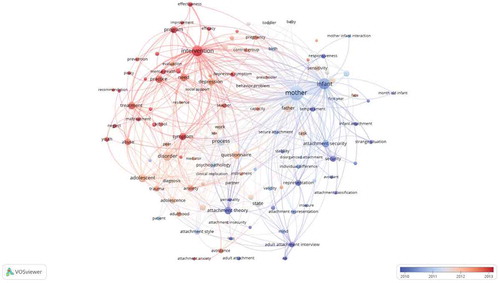

Science mapping

Bibliometric analyses were conducted by loading the bibliographic data collected into the software program VOSviewer 1.6.10 (Van Eck & Waltman, Citation2016) for the construction and visualization of bibliographic networks. This software projects “nodes,” such as publications, authors, or terms, in a two-dimensional space based on a normalized index for bibliographic similarity (i.e. link strength). To map the structure of topics and themes in the literature citing meta-analyses of attachment research, natural language processing of titles and abstracts was conducted, extracting nouns and adjective-noun combinations. Only terms that occurred 100 times or more were included (for interpretability). The algorithm ranks the terms found based on the extent to which co-occurrence appears systematic or random, keeping only the 60% most relevant terms. Terms were excluded if these described meta-analysis or study methods (given the interest in substantive focus), referred to review, or if the terms appeared trivial (such as type of publication, statistical terms, or country of study). The full list of excluded terms can be found in Supplemental Material Appendix B. The mapped structure of the body of citing literature was based on the number of times two terms occurred together in the same publication (Van Eck & Waltman, Citation2014). In addition, the program performs a weighted and parameterized variant of modularity-based clustering on the link strengths to reveal additional distinctions beyond those that can be derived from the two-dimensional scaling (Waltman et al., Citation2010). Additional bibliometric analyses were conducted on the bibliographic data using the Bibliometrix package (Aria & Cuccurullo, Citation2017) for R, via the Biblioshiny interface.

Findings

As of 9 June 2019, the meta-analyses on attachment had been cited in 7,595 publications, growing at an annual rate of 24% per year up to and including 2018. To put this into perspective, the landmark publication by Ainsworth et al. (Citation1978) that initiated empirical attachment research was cited in total 8,641 times, peaking at 480 citations in 2015.

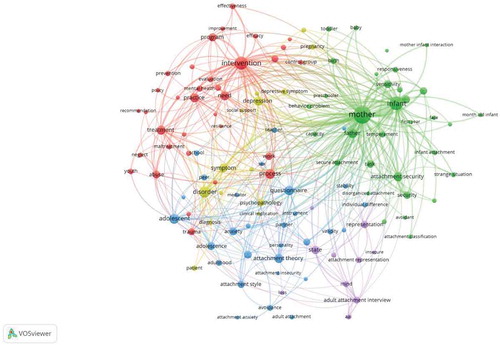

Clusters based on machine reading for meaningful terms and phrases in titles and abstracts are shown in . shows the same clusters, with colour gradient indicating average year of the publications from which these terms were drawn. For each of the clusters we provide a brief interpretation.

Figure 4. Network clusters of nouns and adjective-noun combinations extracted by natural language processing of titles and abstracts of publications that cited attachment meta-analyses

Figure 5. Network of nouns and adjective-noun combinations extracted by natural language processing of titles and abstracts by average year of publication citing attachment meta-analyses

The red cluster depicts a network of 34 terms referring to intervention. Besides “intervention,” dominant terms include “treatment,” “program,” “practice,” “need,” “process,” and “abuse.” The overlay of publication year of the articles from which these terms were derived indicates increasing interest in this set of topics.

The green cluster depicts a network of 33 terms that reflect the vocabulary that Ainsworth, the founder of attachment research as an empirical paradigm, proposed for describing parent–child relationships. Besides “mother,” “infant,” and “father,” dominant terms are (attachment) “security,” “responsiveness,” and (maternal) “sensitivity.” The overlay of publication year shows, overall, a decrease of attention to the topics in this cluster relative to the other clusters. However, publications on sensitivity and on fathers specifically has been increasing among papers citing the meta-analyses, following an opposed trend.

The blue cluster depicts a network of 29 items that refer to attachment styles as conceptualized within the social psychological tradition of self-report assessments of attachment (Roisman, Citation2009). Dominant terms in addition to “attachment style” are “questionnaire,” “attachment theory,” “adolescent”/”adolescence,” “adult,” and “anxiety.” While the terms attachment style and attachment theory appear to be used less over time in the field demarcated by attachment meta-analyses, attention has increased in attachment anxiety and avoidance. This follows the identification of these as the latent dimensions of individual differences in adult attachment by Brennan et al. (Citation1998), which helped to retire the category-focused concept of “attachment style” previously used by the social psychological tradition. Attachment anxiety and avoidance have, since then, become somewhat synonymous with attachment theory for social psychologists (e.g. Mikulincer & Shaver, Citation2003), likely contributing to the decline of the latter term.

The yellow cluster consists of a smaller network of 14 items referring to disorder. The cluster is dominated, in addition to the term “disorder,” by terms around “symptom,” “depression,” and “psychopathology.” With this cluster straddling the intervention-cluster, the publication years of the underling articles indicate a similar increase in attention in this field.

The purple cluster contains 10 items, identifying interest in attachment representations, also denoted as “state of mind regarding attachment” (Main et al., Citation1985). Terms that form this cluster are “Adult Attachment Interview,” “AAI,” “state (of) mind,” and “(attachment) representation.” The publication years underlying this set of terms suggest that interest in these aspects is decreasing relative to the other topics in this field.

Discussion

The proportion of publications that refer to mothers and children using the classic terminology introduced by Mary Ainsworth and to the concept of attachment state of mind as conceptualized by Mary Main has been relatively decreasing among studies citing attachment meta-analyses. The notable exception is increasing citation of publications dealing with sensitivity, perhaps due to the importance of sensitivity for causal models.

There also appears to have been increasing citation of attachment meta-analyses on research using self-report instruments for attachment anxiety and avoidance in adolescence and adulthood. This trend is visible without even taking into account possible meta-analyses that may have been published on the adult romantic attachment literature in social psychology. While emergence of research using the anxiety and avoidance concepts may reflect genuine shifts in interest, research strategies may also play a role. Social psychology more broadly has seen an increase in self-report and online data collection, which is explained by increasing awareness of the need to have sufficient statistical power (Sassenberg & Ditrich, Citation2019). Attachment research in the developmental tradition uses observational and interview instruments that are particularly taxing for research participants and time-consuming and difficult to master for researchers. Without innovation in these methods, it may become increasingly difficult to address issues of statistical power, participant burden, and reliability, especially in light of the attachment field-specific effect size benchmarks derived in the preceding section, which are lower than the conventional benchmarks proposed by Cohen (Citation1988).

A majority of meta-analyses on developmental studies of child-parent attachment are still concerned with theoretical issues, while meta-analyses on interventions are increasing only in absolute numbers but remain proportionally stable at 15%. It may be that attachment researchers have increased their contributions to societal impact in other ways, such as in training of practitioners or contributions to policy. Such trends are difficult to detect in bibliographic research. What the bibliographic impact analysis does make clear, however, is that citation impact of attachment meta-analyses is increasing most clearly within the body of papers dealing with clinical issues and interventions, indicating at least that the scientific interest in applications of attachment research is growing.

Optimizing societal contributions of attachment research

Attachment theory itself has its origins in recognition of the plight of children and their parents. Responsiveness to societal calls for engagement can be traced as far back to Bowlby’s work for the World Health Organization (Bowlby, Citation1951) on welfare for homeless children. Duschinsky’s (Citation2020) critical account of Bowlby’s dissemination style and strategy highlights that such engagement may have promoted the viability of the research program that ensued in the wake of considerable public interest. The emerging theory of attachment gained traction as it could be seen to help solve actual societal problems, such as contesting alternative explanations for the behaviors observed among children in hospitals and institutions. However, oversimplifications and overstated claims, especially in Bowlby’s popular writings, also loaded attachment theory with a legacy of political and scientific controversy and misapprehension. Duschinsky (Citation2020) has documented that in contrast to Bowlby, Ainsworth and many from the second generation of attachment researchers in her footsteps showed reluctance in engaging with the public about the practical implications of their research. This was in part to focus efforts on establishing attachment as a field of empirical inquiry, but may also have been motivated by a desire to avoid becoming embroiled in the controversies around Bowlby’s public claims about working parents and daycare. In addition, the complexity of key measures and theory facilitated the development of an oral culture of shared knowledge, and this limited opportunities for an open dialogue between attachment researchers, colleagues from cognate fields, and the public (Duschinsky, Citation2020). The strategy of focusing on establishing attachment as a field of empirical inquiry before engaging with public and practitioners may even have backfired in certain respects. Terms like “attachment security” and “sensitivity” have circulated in the public sphere and served as tools for clinical and child welfare professionals in ways that diverge from the tacit knowledge of experts (Duschinsky, Citation2020). Recognizing how the continuing misrepresentation of attachment theory undermines the legitimacy of attachment research itself, researchers like Cassidy (Citation2015) and Madigan (Citation2019) have explicitly called on the field to prioritize dissemination and translation. In fact, we perceive academic research on attachment as already in conversation with, and sometimes relying on, assumptions from ordinary language and simplified theoretical concepts – but without realising that this is taking place, and without sufficient focus and coherence (cf. Duschinsky, Citation2020; Duschinsky et al., Citation2021).

Attachment researchers are not alone in having to reconsider their stance towards interacting with the public, practitioners, and policymakers. Duschinsky and colleagues (Duschinsky, Citation2020; Reijman et al., Citation2018) have documented factors that have made this interaction particularly strained, but it should be recognized as a wider issue. Godin and Schauz (Citation2016) describe the shift from science being a central cultural value to a subsidiary issue in the public sphere, with “research” becoming an umbrella term that includes but is not necessarily limited to research with a scientific purpose. Their historical overview describes the commodification of research to deliver public and private goods. This commodification is accompanied by overall decreases in expectations about the difference that the work of individual scientists can make and an increase in expectations that research may deliver public goods only when properly organized and managed. From the perspective of scientists themselves, this means that pure knowledge wanes as a pursuit sanctioned by the larger society and that a sense of purpose may be found more readily in the mobilizing calls from communities, parent and patient organizations, societies, and supranational bodies. Although the causal direction remains to be determined, the most prolific of scientists have been found to regularly cross back-and-forth between knowledge production and skills creation, development of technology, and engagement with end-users of knowledge and technology (Tijssen, Citation2018). It was his willingness to engage with wine manufacturers that led Louis Pasteur to understand how his basic scientific findings in crystallography could help to sort out what made grape juice turn into wine, and in so doing discover how fermentation works, subsequently propose his germ theory of disease, and develop simple procedures like pasteurization saving millions of lives (Ligon, Citation2002).

Crossing over from theory to practice and back may not only increase the value of research by fostering serendipity but also by addressing epistemological problems. In his advice for addressing the incoherency of the social sciences, Watts (Citation2017) suggests to focus on “Goldilocks problems.” These are the sorts of societal problems that are difficult enough to require advances in theory and methods while also being amenable for incremental progress using existing theoretical and empirical tools of science. Especially attractive are problems that are easily recognized as important by those affected and where the successes in solving it are readily perceived, even though the intermediate scientific advances itself may be highly complex and specialized. Importantly, the requirement that solutions work in settings that social science aims to understand (e.g. families, education, welfare, and care settings) gives replicable and generalizable findings a selective advantage over those that are non-replicable or can only be observed under highly specific (i.e. non-generalizable) conditions. Solution-focused research would therefore not only quell doubts about social science’s coherence and legitimacy, but increase its credibility as well. While Duschinsky et al. (this issue) describe how the attachment field is actually positioned in multiple discourses with high public interest (child rearing, mental health, and child welfare) they also show where the ill-fit with the concerns and constraints in these discourses is holding attachment research back from bringing its contributions to scale. Another barrier for the application of attachment research is that scientific meaning and the popular use for terms like sensitivity and attachment are very distinct, and that the extent to which the same words mean different things to different people is hard to overestimate. Efforts to respond to solution-focused calls will therefore be more successful if the conceptual “spring cleaning” suggested by Duschinsky et al. (Citation2021) is taken on board, as this will both help sharpen our tools and our capacity to communicate our conclusions and recommendations. Applying the Goldilocks criterion to the various calls that may be directed to attachment research, we have selected two such calls as illustrations of prospects for attachment research.

Promoting nurturing care

One solution-focused call that might contain Goldilocks properties from the perspective of the attachment field, is equitable access of children across the world to nurturing care, that is to good health, nutrition, security and safety, responsive caregiving, and opportunities for early learning (Britto et al., Citation2017). Underlying this call was the argument that early childhood development programmes are key to achieving the health, wellbeing, and education goals for sustainable development that global nations have set for 2030, citing a pathway from genetic and epigenetic variation, through attachment and learning systems, to life-span health and development (Black et al., Citation2017). This argument draws on the well-established role of caregiver sensitivity that emerged from the bibliographic analysis as continuing to have increasing scientific impact. With global institutions such as UNICEF, WHO, the World Bank Group, and UNESCO prioritizing investments into early childhood development as part of the overall efforts to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, the initiative takers for the Nurturing Care Framework saw the urgency of formulating an unified strategy and articulation of the importance of responsive caregiving and early learning as essential for good quality care (World Health Organixation [WHO], United Nations Children’s Fund [UNCF] & World Bank Group, Citation2018). Interventions developed to support caregivers’ sensitive responsiveness on the basis of attachment theory and other well-established theories such as social learning theory (Patterson, Citation1982) may provide a fruitful basis for contributing to the strategic actions laid out in the roadmap provided by the nurturing care framework and thereby go beyond local implementation in high resource countries to also reach low to medium resource areas. For example, the strategic action to strengthen services for families and caregivers may be augmented on the basis of the strong evidence that interventions increase parental sensitivity (Bakermans-Kranenburg et al., Citation2003; Facompré et al., Citation2018). Work on the Circle of Security (Yaholkoski et al., Citation2016), Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up (Dozier & Bernard, Citation2017), and VIPP (Juffer et al., Citation2017) is crossing the threshold from establishing an evidence base for program efficacy to scaling up (in settings where these programs were experimentally tested) and scaling out (to new settings). Attachment researchers may also be called upon to contribute to the nurturing care framework’s strategic action to monitor progress in access to nurturing care and the development and implementation of indicators of responsive caregiving in national monitoring plans. Several research groups have research lines underway to develop and test instruments that ultimately could be suitable for use by practitioners (e.g. Cooke et al., Citation2020; Forrer et al., Citation2018). Coordination and exchange between such lines might speed up cycles of development, independent validation, and synthesis of data considerably, building on the infrastructure for collaborative work that the field has been building across decades, such as training institutes and forums such as Attachment & Human Development (Duschinsky, Citation2020). Furthermore, attachment researchers may tease out the importance of nurturing care in the network of multiple attachment relationships that children develop (Dagan & Sagi-Schwartz, Citation2018). Being aware of the downsides of simplifying messages to public and stakeholders about continuity of care and maternal deprivation in the early days of the attachment program (Duschinsky, Citation2020), the attachment field may challenge the nurturing care framework to look beyond its present focus on maternal caregivers.

Solving issues related to implementation of interventions and care indicators across a wide array of local communities will not only require crossing disciplinary boundaries (e.g. educational science, communication science, implementation science) but also stimulate scientific progress. Joining global initiatives such as the nurturing care framework will confront attachment researchers with questions regarding the ecological and cultural validity of concepts and methods (cf. Keller, Citation2013; Mesman et al., Citation2018), which they will need to address if their contribution is to be regarded as useful. Furthermore, as attachment-based interventions may need to be locally adapted, evaluated, and integrated within broader programs, the focus on program integrity and treatment adherence for evidence-based interventions (e.g. Costello et al., Citation2019) may no longer be tenable. Rather, it becomes necessary to understand the specific components of intervention effectiveness, how these relate to mechanisms of behavior change in context, and how these mechanisms are related to mechanisms of attachment development (Bosmans et al., Citation2019; Mohamed et al., Citation2019; Schuengel & Tharner, Citation2020). These questions can only be answered in any coherent way by collective and coordinated efforts of researchers collecting data across settings and countries. Sharing and comparing data from efficacy trials allows robust tests of effect mediation and moderations as well as gauge the extent to which there are clear “winning” matches of intervention practice elements with populations and settings (cf. Chorpita & Daleiden, Citation2009) or that efficacy of different practice elements is largely equivalent. The attachment field has a long tradition of sharing data (e.g. Lamb et al., Citation1992; Van IJzendoorn et al., Citation1992) and disseminating the products resulting from those data back in the research community (e.g. the coding system for disorganized attachment; Main & Solomon, Citation1990). More recent examples suggesting the viability of collaborative research approaches include Individual Participant Data meta-analyses on the intergenerational transmission of attachment (Verhage et al., Citation2018). Thus, the call to ensure nurturing care or related calls to socially embed long-term prevention of common mental health disorders by reducing maladaptive parenting (Holmes et al., Citation2018; Ormel et al., Citation2020) exhibits Goldilocks properties both in allowing incremental progress through knowledge and methods that are already available or are part of a sound program of research as well as requiring fundamental scientific advances to be forged through coordinated large-scale research efforts.

Reducing harm in child welfare

The increasing scientific impact of attachment findings on work dealing with issues of disorder and intervention suggests that attachment research is viewed as germane to supporting children at risk for harm to their wellbeing. Child welfare epitomizes these problems, but at first blush, the problems within this field may fall outside the Goldilocks zone of viable attachment research. Child maltreatment and child welfare entail dynamic, multilayered interactions in which actors become increasingly defined by those interactions, thus exhibiting properties of complex systems (Cohn et al., Citation2013). Others have described child abuse as a “wicked problem” (e.g. Devaney & Spratt, Citation2009), one that is maintained by structural socioeconomic inequalities at a macrosystem level and partly reproduced through child and social welfare intervening at meso and microsystem levels (Davidson et al., Citation2017). Solutions for one aspect of wicked problems are bound to engender new problems, because there may not be agreement on the nature of the problem and on what solutions are deemed acceptable (Rittel & Webber, Citation1973). A case in point is the way in which attachment theory has highlighted the inadequacy of practices such as residential placements for addressing children’s needs (e.g. Dozier et al., Citation2014). Another example regards the argument made about the harm caused by involuntary separation of children from their parents when suspected of illegal entry to the country (Jones-Mason et al., Citationin press). However, distorted and misconstrued versions of attachment theory and research have unfortunately been also instrumental in inflicting harm (see e.g. Chaffin et al., Citation2006, on coercive “re-attachment” therapies; Granqvist et al., Citation2017, on using attachment categories to assess risk; Forslund et al., Citation2020).

Misinterpretations and misuses of attachment concepts may not only reveal cognitive biases and barriers to proper understanding (Epley & Caruso, Citation2009; Lilienfeld et al., Citation2014) but also reveal what the needs of workers and caregivers are (i.e. averting risk; Devaney & Spratt, Citation2009), providing input for a research agenda that matches these needs. Such dialogue has, for example, led to the development of brief assessment instruments for atypical parental behavior (Cooke et al., Citation2020) and the testing of protocols for intervention-informed decision-making (Cyr & Alink, Citation2017; Van der Asdonk et al., Citation2019). As such, attachment research that responds to these concrete needs may be seen as solution-focused, even though in the case of complex systems, solutions will remain partial and the process will be iterative and tailored towards locally agreed problem formulations (Greenhalgh & Papoutsi, Citation2018). However, even if theoretical insight and empirical evidence are available to address the needs of children, parents, and workers, translation into action may be hampered by the difference between technical definitions of attachment-related concepts and the meaning that the same words take on in everyday usage. Much may be learnt from projects (e.g. Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, Citation2014) that have systematically worked to formulate scientific insights in clear, accurate, and uniform ways and support learning communities, leadership programs, and educational resources to innovate child welfare. Rather than explaining what attachment is and how relationships may exhibit different qualities, their dissemination efforts emphasize the importance of stable relationships, responsive caregiving, and serve and return interactions. What is less clear from some of the center’s projects is how learning communities and educational programs may evaluate the progress being made and steer the direction of the research agenda. Rather than only serving the translated end product of research, engagement between science and practice may also give stakeholders and public the opportunity to return on the serve with critical reflections and additional needs. Methods for guideline development such as Grading of Evidence, Assessment and Evaluation (GRADE; Guyatt et al., Citation2008) involve the appraisal from multiple perspectives of the strength of evidence for benefit and harm, assessment of resources needed and implementation preconditions, and preferences and values of stakeholders. Through such a process, knowledge gaps may be identified and research prioritized alongside implementation of those recommendations for which sufficient knowledge exists (Maher & Ford, Citation2017). Accordingly, a team of attachment researchers, clinicians, and (former) care users produced a guideline for the UK about attachment in children and young people who are adopted from care, in care or at high risk of going into care (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE], Citation2016). The enormous challenge of further reducing child maltreatment within families (Finkelhor et al., Citation2015) and “institutional abuse” (Exalto et al., Citation2019) calls for continued contributions from the attachment research program.

Conclusions

Research on children’s attachments remains a lively area of research which continues to be consolidated in meta-analyses, which in turn are cited in an ever-increasing volume of papers in the wider scientific field. Furthermore, the evidence is increasingly cited in scientific publications on interventions and disorders, suggesting that results from empirical attachment research are recognized as germane to solving real-world problems. However, our brief review of attachment meta-analyses also reveal challenges ahead for continuing progress.

One challenge derives from calibrating effect size expectations to levels lower than the arbitrary rule of thumb criteria that are often derived from Cohen (Citation1988), meaning that proposals for new studies would have to include larger samples than before. Using the main effect sizes reported in attachment meta-analyses as a benchmark to interpret effect sizes (Funder & Ozer, Citation2019), small effects may be those around r = .10, medium effects those around r = .20, and large effects those around r = .30. Very large effects (r = .40 and higher) in primary studies are more likely to be overestimations, made possible by running small studies, and unlikely to replicate. Benchmarks for study sample size therefore need to be drastically revised upwards, putting increasing pressure on research resources.

Another challenge derives from the widening gap between interest in the academic literature increasingly being in interventions and clinical issues while the focus of meta-analyses in intervention issues remains stably low (15%). Keeping attachment research relevant therefore requires increasing attention towards issues relevant to intervention while addressing issues of statistical power and generalizability. This is easier said than done, given that conducting studies that allow causal inferences to be made (i.e. randomized clinical trials) require multiple assessments (e.g. pretest, posttest, follow-up) within the same sample, with assessments further multiplied by the process-related constructs that might need to be included when testing intervention models (e.g. changes in sensitivity driving changes in attachment quality). One approach to yield novel insights into how attachment-based interventions work and for whom is to conduct Individual Participant Data meta-analyses (Verhage et al., Citation2020), an effort that is currently underway as the Collaboration for Attachment and Parenting Intervention Synthesis (https://osf.io/5qhcu/). By bringing together as collaborators all relevant data collected in previous trials, it may be possible to test (registered) mediator and moderator hypotheses with sufficient statistical power. Another approach that may be feasible for the field given its strong infrastructure for cross-site dissemination is the ManyBabies approach (Frank et al., Citation2017), which involves the coordinated and simultaneous conducting of experimental studies across research sites, based on preregistered research protocols. The argument that this approach would address issues of replicability, generalizability, and feasibility at once should be brought in with funders, who would need to either coordinate their efforts across national borders or relax criteria on where funding should be spent. These challenges appear to be mostly of a practical nature and should therefore in principle be solvable.

While moving to the level of collaboration would be an evolutionary step, keeping business as usual largely intact, moving to the level of engagement confronts the field of attachment with existential questions. Attachment theory is about relationships, which is a level of abstraction above that of people and behavior. Not only is attachment in everyday usage more often understood as an individual’s affective experience rather than as a quality of dyadic interaction, discourse between attachment researchers and stakeholders may also be hampered because researchers may reason at the abstract level of relationships while stakeholders may reason at the more concrete level of individuals and behavior. Many of the misunderstandings and misrepresentations of attachment research have resulted from applying relationship-concepts such as attachment to the level of the individual (Duschinsky et al., Citation2021; Forslund et al., Citation2020). Although strong arguments for relationship-based science and practice have been made, particularly with regard to interventions in early childhood (e.g. Winnicott’s adage “there is no such thing as a baby without a mother”; Mitchell, Citation2009), the emphasis on this perspective is partly normative and therefore the extra mental effort required to conceptualize problems at this level needs to be justified and validated. Recently in the Netherlands, questionnaires have been developed and disseminated that capture parents’ own perceptions of the quality of their attachment relationships with their child (e.g. Spruit et al., Citation2018). The ease of use and free availability of these instruments will accelerate the proliferation of structured measurement of attachment across fields of practice and even into the private sphere, presenting a serious test whether this form of engagement will actually solve problems faced by families or create new ones.

Moving towards collaborative engagement raises the stakes for the field of attachment research. On the one hand, ill-considered responses to societal needs may backfire and call the legitimacy of the research into question. The attachment research field has suffered from, but ultimately survived, the onslaught on its reputable nature from misapplications of its central tenets before, like in the case of attachment therapies (see Chaffin et al., Citation2006) and attachment parenting (Moore & Abetz, Citation2016). On the other hand, numerous scientific fields have been shown to flourish when the strategic importance of these fields for addressing societal challenges was recognized and these scientists were supported not only with the needed funding but also by the management and coordination required to make these efforts fruitful and sustainable (Sarewitz, Citation2016). An illustration of the latter possibility can be seen in response of the scientific world to the SARS-Cov-2 pandemic that started in 2020, showing not only coordinated calls to action for developing treatments and vaccines, but also for addressing the impact on mental health (Holmes et al., Citation2020) and families (Prime et al., Citation2020). Families are poised to bear the brunt of increasing uncertainty, lingering health problems, complex mourning, and erosion of the protective matrix offered by communities. It is evident that the attachment field has a contribution to offer to address these challenges.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (323.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

References

- Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment. Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Aria, M., & Cuccurullo, C. (2017). bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. Journal of Informetrics, 11(4), 959–975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2017.08.007

- Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Juffer, F. (2003). Less is more: Meta-analyses of sensitivity and attachment interventions in early childhood. Psychological Bulletin, 129(2), 195–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.195

- Black, M. M., Walker, S. P., Fernald, L. C. H., Andersen, C. T., DiGirolamo, A. M., Lu, C., McCoy, D. C., Fink, G., Shawar, Y. R., Shiffman, J., Devercelli, A. E., Wodon, Q. T., Vargas-Barón, E., & Grantham-mcgregor, S. (2017). Early childhood development coming of age: Science through the life course. The Lancet, 389(10064), 77–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31389-7

- Bosmans, G., Waters, T. E. A., Finet, C., De Winter, S., & Hermans, D. (2019). Trust development as an expectancy-learning process: Testing contingency effects. Plos One, 14(12), e0225934. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225934

- Bowlby, J. (1951). Maternal care and mental health. World Health Organisation.

- Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 46–76). Guilford.

- Britto, P. R., Lye, S. J., Proulx, K., Yousafzai, A. K., Matthews, S. G., Vaivada, T., Perez-Escamilla, R., Rao, N., Ip, P., Fernald, L. C. H., MacMillan, H., Hanson, M., Wachs, T. D., Yao, H., Yoshikawa, H., Cerezo, A., Leckman, J. F., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2017). Nurturing care: Promoting early childhood development. The Lancet, 389(10064), 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31390-3

- Brydges, C. R. (2019). Effect size guidelines, sample size calculations, and statistical power in gerontology. Innovation in Aging, 3(4). https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igz036

- Cassidy, J. (2015, August 8). Early relationships, later functioning Why and how a secure base matters [Paper presentation]. The International Attachment Conference, New York.

- Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. (2014). A decade of science informing policy: The story of the national scientific council on the developing child. Retrieved February 8, 2020, from http://www.developingchild.net

- Chaffin, M., Hanson, R., Saunders, B. E., Nichols, T., Barnett, D., Zeanah, C., Berliner, L., Egeland, B., Newman, E., Lyon, T., Letourneau, E., & Miller-Perrin, C. (2006). Report of the APSAC task force on attachment therapy, reactive attachment disorder, and attachment problems. Child Maltreatment, 11(1), 76–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559505283699

- Chorpita, B. F., & Daleiden, E. L. (2009). Mapping evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: Application of the distillation and matching model to 615 treatments from 322 randomized trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(3), 566–579. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014565

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Academic Press.

- Cohn, S., Clinch, M., Bunn, C., & Stronge, P. (2013). Entangled complexity: Why complex interventions are just not complicated enough. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 18(1), 40–43. https://doi.org/10.1258/jhsrp.2012.012036

- Cooke, J. E., Eirich, R., Racine, N., Lyons-Ruth, K., & Madigan, S. (2020). Validation of the AMBIANCE-brief: An observational screening instrument for disrupted caregiving. Infant Mental Health Journal, 41(30), 299–312. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21851

- Costello, A. H., Roben, C. K. P., Schein, S. S., Blake, F., & Dozier, M. (2019). Monitoring provider fidelity of a parenting intervention using observational methods. Professional Psychology, Research and Practice, 50(4), 264–271. https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000236

- Cyr, C., & Alink, L. R. A. (2017). Child maltreatment: The central roles of parenting capacities and attachment. Current Opinion in Psychology, 15, 81–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.02.002

- Dagan, O., & Sagi-Schwartz, A. (2018). Early attachment network with mother and father: An unsettled issue. Child Development Perspectives, 12(2), 115–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12272

- Davidson, G., Bunting, L., Bywaters, P., Featherstone, B., & McCartan, C. (2017). Child welfare as justice: Why are we not effectively addressing inequalities? British Journal of Social Work, 47(6), 1641–1651. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcx094

- Devaney, J., & Spratt, T. (2009). Child abuse as a complex and wicked problem: Reflecting on policy developments in the United Kingdom in working with children and families with multiple problems. Children and Youth Services Review, 31(6), 635–641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2008.12.003

- Dozier, M., & Bernard, K. (2017). Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up: Addressing the needs of infants and toddlers exposed to inadequate or problematic caregiving. Current Opinion in Psychology, 15, 111–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.03.003

- Dozier, M., Kaufman, J., Kobak, R., O’Connor, T. G., Sagi-Schwartz, A., Scott, S., Shauffer, C., Smetana, J., Van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Zeanah, C. H. (2014). Consensus statement on group care for children and adolescents: A statement of policy of the American Orthopsychiatric Association. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84(3), 219–225. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000005

- Duschinsky, R. (2020). The cornerstones of attachment research. Oxford University Press.

- Duschinsky, R., Bakkum, L., Mannes, J. M. M., Skinner, G. C. M., Turner,, M., Mann, A., Coughlan, B., Reijman, S., Foster, S., & Beckwith, H. (2021). Six attachment discourses: Convergence, divergence and relay. Attachment & Human Development.

- Epley, N., & Caruso, E. (2009). Perspective taking: Misstepping into others’ shoes. In K. D. Markman, W. M. P. Klein, & J. A. Suhr (Eds.), Handbook of imagination and mental simulation (pp. 295–309). Psychology Press.

- Exalto, J., Bekkema, N., De Ruyter, D., Rietveld-Van Wingerden, M., De Schipper, J. C., Oosterman, M., & Schuengel, C. (2019). Sectorstudie geweld in de residentiële jeugdzorg [Sector study violence in residential youth care]. In Commissie Onderzoek naar Geweld in de Jeugdzorg (Ed.), Sector- en themastudie geweld in de jeugdzorg [Sector and thematic study violence in youth care]. WODC The Hague.

- Facompré, C. R., Bernard, K., & Waters, T. E. A. (2018). Effectiveness of interventions in preventing disorganized attachment: A meta-analysis. Development and Psychopathology, 30(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579417000426

- Finkelhor, D., Turner, H. A., Shattuck, A., & Hamby, S. L. (2015). Prevalence of childhood exposure to violence, crime, and abuse: Results from the national survey of children’s exposure to violence. JAMA Pediatrics, 169(8), 746–754. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0676

- Forrer, M., Schuengel, C., Oosterman, M., & Fearon, R. M. P. (2018, October 10). The effect of decision trees on rater accuracy in assessment of parental behavior [Paper presentation]. EUSARF, Porto, Portugal.

- Forslund, T., Granqvist, P., Van IJzendoorn, M. H., Sagi-Schwartz, A., Glaser, D., Steele, M., & Duschinsky, R. (2020). Attachment goes to court: Child protection and custody issues. Attachment & Human Development. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2020.1840762

- Fraley, R. C., & Marks, M. J. (2007). The null hypothesis significance testing debate and its implications for personality research. In R. W. Robins, R. C. Fraley, & R. F. Krueger (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in personality psychology (pp. 149–169). Guilford.

- Frank, M. C., Bergelson, E., Bergmann, C., Cristia, A., Floccia, C., Gervain, J., Hamlin, J. K., Hannon, E. E., Kline, M., Levelt, C., Lew-Williams, C., Nazzi, T., Panneton, R., Rabagliati, H., Soderstrom, M., Sullivan, J., Waxman, S., & Yurovsky, D. (2017). A collaborative approach to infant research: Promoting reproducibility, best practices, and theory-building. Infancy, 22(4), 421–435. https://doi.org/10.1111/infa.12182

- Funder, D. C., & Ozer, D. J. (2019). Evaluating effect size in psychological research: Sense and nonsense. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 2(2), 156–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245919847202

- Gignac, G. E., & Szodorai, E. T. (2016). Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers. Personality and Individual Differences, 102, 74–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.069

- Godin, B., & Schauz, D. (2016). The changing identity of research: A cultural and conceptual history. History of Science, 54(3), 276–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0073275316656007

- Granqvist, P., Sroufe, L. A., Dozier, M., Hesse, E., Steele, M., Van IJzendoorn, M., Solomon, J., Schuengel, C., Fearon, P., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M., Steele, H., Cassidy, J., Carlson, E., Madigan, S., Jacobvitz, D., Foster, S., Behrens, K., Rifkin-Graboi, A., Gribneau, N., Ward, M. J., … Duschinsky, R. (2017). Disorganized attachment in infancy: A review of the phenomenon and its implications for clinicians and policy-makers. Attachment & Human Development, 19(6), 534–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2017.1354040

- Greenhalgh, T., & Papoutsi, C. (2018). Studying complexity in health services research: Desperately seeking an overdue paradigm shift. BMC Medicine, 16(1), 95. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1089-4

- Guyatt, G. H., Oxman, A. D., Vist, G. E., Kunz, R., Falck-Ytter, Y., Alonso-Coello, P., & Schünemann, H. J. (2008). GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ, 336(7650), 924–926. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD

- Holmes, E. A., Ghaderi, A., Harmer, C. J., Ramchandani, P. G., Cuijpers, P., Morrison, A. P., Bockting, C. L., O’Connor, R. C., Shafran, R., Moulds, M. L., & Craske, M. G. (2018). The Lancet psychiatry commission on psychological treatments research in tomorrow’s science. The Lancet Psychiatry, 5(3), 237–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30513-8

- Holmes, E. A., O’Connor, R. C., Perry, V. H., Tracey, I., Wessely, S., Arseneault, L., Christensen, H., Silver, R.C., Everall, I., Ford, T., & Bullmore, E. (2020). Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(6), 547–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1

- Ioannidis, J. P., & Trikalinos, T. A. (2007). An exploratory test for an excess of significant findings. Clinical Trials, 4(3), 245–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/1740774507079441

- Jones-Mason, K., Behrens, K. Y., & Gribneau Bahm, N. I. (). The psychobiological consequences of child separation at the border: Lessons from research on attachment and emotion regulation. Attachment & Human Development, 23(1), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2019.1692879

- Juffer, F., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & Van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2017). Pairing attachment theory and social learning theory in video-feedback intervention to promote positive parenting. Current Opinion in Psychology, 15, 189–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.03.012

- Keller, H. (2013). Attachment and culture. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44(2), 175–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022112472253

- Kvarven, A., Strømland, E., & Johannesson, M. (2020). Comparing meta-analyses and preregistered multiple-laboratory replication projects. Nature Human Behaviour, 4(4), 423–434. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-019-0787-z

- Lamb, M. E., Sternberg, K. J., & Prodromidis, M. (1992). Nonmaternal care and the security of infant mother attachment: A reanalysis of the data. Infant Behavior & Development, 15(1), 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/0163-6383(92)90007-s

- Ligon, B. L. (2002). Biography: Louis Pasteur: A controversial figure in a debate on scientific ethics. Seminars in Pediatric Infectious Diseases, 13(2), 134–141. https://doi.org/10.1053/spid.2002.125138

- Lilienfeld, S. O., Ritschel, L. A., Lynn, S. J., Cautin, R. L., & Latzman, R. D. (2014). Why ineffective psychotherapies appear to work: Ataxonomy of causes of spurious therapeutic effectiveness. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9(4), 355–387. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614535216

- Madigan, S. (2019, July 18). Beyond the academic silo: Collaboration and community partnerships in attachment research [Paper presentation]. The International Attachment Conference, Vancouver, CA.

- Maher, D., & Ford, N. (2017). A public health research agenda informed by guidelines in development. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 95(12), 795–795A. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.17.200709

- Main, M., Kaplan, N., & Cassidy, J. (1985). Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. In I. Bretherton & E. Waters (Eds.), Growing points of attachment theory and research (Vols. 50, no. (1–2), pp. 66–104). Society for Research in Child Development.

- Main, M., & Solomon, J. (1990). Procedures for identifying infants as disorganized/disoriented during the Ainsworth strange situation. In M. T. Greenberg, D. Cicchetti, & E. M. Cummings (Eds.), Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research, and intervention (pp. 121–160). The University of Chicago Press.

- Mesman, J., Minter, T., Angnged, A., Cissé, I. A. H., Salali, G. D., & Migliano, A. B. (2018). Universality without uniformity: A culturally inclusive approach to sensitive responsiveness in infant caregiving. Child Development, 89(3), 837–850. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12795

- Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2003). The attachment behavioral system in adulthood: Activation, psychodynamics, and interpersonal processes. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 35, pp. 53–152). Academic Press.

- Mitchell, J. (2009). Using Winnicott. In S. D. Sclater, D. W. Jones, H. Price, & C. Yates (Eds.), Emotion: New psychosocial perspectives (pp. 46–56). Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Mohamed, A. R., Sterkenburg, P. S., Van Rensburg, E., & Schuengel, C. (2019, July 12). The development of a coding system to examine the effective elements of attachment-based interventions [Paper presentation]. The International Attachment Conference, Vancouver, CA.

- Moore, J., & Abetz, J. (2016). “Uh Oh. Cue the [New] Mommy Wars”: The ideology of combative mothering in popular u.s. newspaper articles about attachment parenting. Southern Communication Journal, 81(1), 49–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/1041794X.2015.1076026

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2016). Children’s attachment: Attachment in children and young people who are adopted from care, in care or at high risk of going into care (NG26). Retrieved May 17, 2020, from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng26

- Ormel, J., Cuijpers, P., Jorm, A., & Schoevers, R. A. (2020). Fixation what is needed to eradicate the depression epidemic, and why. Mental Health & Prevention, 17, 200177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhp.2019.200177

- Patterson, G. R. (1982). A social learning approach to family intervention. III. Coercive family process (IIIrd ed.). Castalia.

- Prime, H., Wade, M., & Browne, D. T. (2020). Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist., 75(5), 631–643. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000660

- Reijman, S., Foster, S., & Duschinsky, R. (2018). The infant disorganised attachment classification: “Patterning within the disturbance of coherence”. Social Science & Medicine, 200, 52–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.12.034

- Richard, F. D., Bond, C. F., Jr., & Stokes-Zoota, J. J. (2003). One hundred years of social psychology quantitatively described. Review of General Psychology, 7(4), 331–363. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.7.4.331

- Rittel, H. W. J., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4(2), 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01405730

- Roisman, G. I. (2009). Adult attachment: Toward a rapprochement of methodological cultures. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(2), 122–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01621.x

- Sarewitz, D. (2016, Spring/Summer). Saving science. The New Atlantis, 40, 5–40. https://www.thenewatlantis.com/docLib/20160816_TNA49Sarewitz.pdf

- Sassenberg, K., & Ditrich, L. (2019). Research in social psychology changed between 2011 and 2016: Larger sample sizes, more self-report measures, and more online studies. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 2(2), 107–114. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245919838781

- Schuengel, C., & Tharner, A. (2020). Patterns of parenting: Revisiting mechanistic models. Attachment & Human Development, 22(1), 66–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2019.1589062

- Spruit, A., Wissink, I., Noom, M. J., Colonnesi, C., Polderman, N., Willems, L., Barning, C., & Stams, G. J. J. M. (2018). Internal structure and reliability of the Attachment Insecurity Screening Inventory (AISI) for children age 6 to 12. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1608-z

- Tijssen, R. J. W. (2018). Anatomy of use-inspired researchers: From Pasteur’s quadrant to Pasteur’s cube model. Research Policy, 47(9), 1626–1638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.05.010

- Van der Asdonk, S., Van Berkel, S. R., De Haan, W. D., Van IJzendoorn, M. H., Schuengel, C., & Alink, L. R. A. (2019). Improving decision-making agreement in child protection cases by using information regarding parents’ response to an intervention: A vignette study. Children and Youth Services Review, 107, 104501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104501

- Van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2014). VosViewer manual. Leiden University.

- Van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2016). VosViewer (Version 1. 6.10) [ Software]. http://www.vosviewer.com/

- Van IJzendoorn, M. H., Sagi, A., & Lambermon, M. W. E. (1992). The multiple caretaker paradox: Some data from Holland and Israel. In R. C. Pianta (Ed.), New directions in child development: Relationships between children and non-parental adults (5–24). Jossey-Bass. (Reprinted from: In File).

- Van IJzendoorn, M. H. (1994). Process model of replication studies: On the relations between different types of replication. In R. Van der Veer, M. H. Van IJzendoorn, & J. Valsiner (Eds.), On reconstructing the mind: Replicability in research on human development (pp. 57–70). Ablex.

- Verhage, M. L., Fearon, R. M. P., Schuengel, C., Van IJzendoorn, M. H., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Madigan, S., Roisman, G. I., Oosterman, M., Behrens, K. Y., Wong, M. S., Mangelsdorf, S., Priddis, L. E., & Brisch, K.-H., & Collaboration for Attachment Transmission Synthesis. (2018). Examining ecological constraints on the intergenerational transmission of attachment via individual participant data meta-analysis. Child Development, 89(6), 2023–2037. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13085

- Verhage, M. L., Schuengel, C., Duschinsky, R., Van IJzendoorn, M. H., Fearon, R. M. P., Madigan, S., Roisman, G. I., Bakermans–Kranenburg, M. J., & Oosterman, M., & The Collaboration on Attachment Transmission Synthesis. (2020). The Collaboration on Attachment Transmission Synthesis (CATS): A move to the level of individual-participant-data meta-analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 29(2), 199–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721420904967

- Waltman, L., Van Eck, N. J., & Noyons, E. C. M. (2010). A unified approach to mapping and clustering of bibliometric networks. Journal of Informetrics, 4(4), 629–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2010.07.002

- Watts, D. J. (2017). Should social science be more solution-oriented? Nature Human Behaviour, 1(1), 0015. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-016-0015

- World Health Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund, & World Bank Group. (2018). Nurturing care for early childhood development: A framework for helping children survive and thrive to transform health and human potential. World Health Organization.

- Yaholkoski, A., Hurl, K., & Theule, J. (2016). Efficacy of the circle of security intervention: A meta-analysis. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 15(2), 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/15289168.2016.1163161