ABSTRACT

In the biomedical, behavioral and neurobiological sciences reproducibility and replicability of research results have become a major issue. The question is whether attachment research is also plagued by lack of replicability, and if so whether one can speak of a crisis? Furthermore, discussions about the applicability of attachment research findings to policy and (clinical) practice have recently been intensified. The subsequent question arises whether one could even speak of a “translational crisis”. In this paper assumptions and conditions of replicability and applicability will be outlined. Some examples of attachment findings lost or found in translation to policy and practice (e.g. on infant crying and parental insensitive responsiveness) will be used to illustrate the challenges and chances of bridging the gap between attachment science and practice.

Attachment in replication crisis?

In the past decade a replication crisis has been raging in the biomedical, neurobiological and behavioral sciences. A crucial question is how attachment theory and research are affected by this crisis, and what the impact is on translation of attachment findings to clinical practice and policy. Theoretical and empirical work on replication in attachment theory goes back at least 35 years (Van IJzendoorn & Hubbard, Citation1987; Van IJzendoorn, Citation1994), but it has recently become topical again. Scientists are more and more convinced of the plausibility of a provocative statement of Ioannidis in 2005 that most published research findings in the biomedical sciences are false (Baker, Citation2016; Fanelli, Citation2018; Ioannidis, Citation2005). Here we review some factors involved in the replication crisis, and we discuss what their role in attachment research may be.

Low statistical power

Low statistical power is one of the major reasons for the replication crisis. The power of a statistical test is the probability of making the correct decision of rejecting the null hypothesis when the null hypothesis indeed is false and there is a “true” effect to detect. A power of 80% is conventionally considered a minimum. In small samples the risk of false negatives or false positives is usually too high. Power failure is endemic in neuroscience studies (Button et al., Citation2013), in research on rodents (Bonapersona et al., Citation2019), and in psychology (Stanley et al., Citation2018). Attachment studies are no exception to the rule that most studies are underpowered. Of 46 studies on the association between unresolved adult attachment representations and infant disorganized attachment not a single study was sufficiently powered (N > 175) to run a tolerably low risk of producing false positives or false negatives findings (Verhage et al., Citation2016).

Blessed or damned by the winner’s curse?

Pioneering but small studies with impressively strong findings might suffer from the winner’s curse (a concept derived from economics, e.g. Thaler, Citation1988). Researchers may be seduced to jump on the promising bandwagon triggered by such a pioneering study with potentially great theoretical and practical impact. They feel inspired to design variations on the original path-finding study but without being able to find equally impressive effects. In attachment research the most prominent example is the famous Baltimore study of Ainsworth and her students (Ainsworth et al., Citation1978) which laid the basis for numerous studies with the Strange Situation Procedure. In the Baltimore study on 26 families the researchers conducted extensive home observations in the first year of the children’s lives and extracted measures of parental sensitivity from the observational notes. Around the first birthday they coded the infants’ patterns of attachment behavior in the Strange Situation Procedure, and they reported an effect size of r=0.78 for the association between caregiver sensitivity and attachment security (Ainsworth et al., Citation1978).

Applying correction for attenuation assuming modest measurement error in the coding of both parental sensitivity and infant attachment, the “real” effect size would be larger than r=0.90, almost a perfect overlap between two variables. In a meta-analysis of subsequent studies on attachment and sensitivity almost 20 years later we indeed found a large gap between the meta-analytic estimate of r=0.22 and the original Baltimore result, which appeared to be a statistical outlier (De Wolff & Van IJzendoorn, Citation1997). Combining the development of new measures of parenting and infant attachment with testing a substantive hypothesis in the Baltimore study was bound to lead to inflated estimates of effect sizes, and to the subsequent failure of replications in independent and blind studies.

Another example of a winner’s curse from attachment research is the association between the security of the maternal attachment representation as assessed from the Adult Attachment Interview and infant attachment security as observed in the Strange Situation Procedure. In the pioneering Berkeley study on 32 mother-child dyads this association was found to be extraordinarily strong; it amounted to r=0.62 (Main et al., Citation1985). In the first study to report on the association between Unresolved loss or trauma assessed in the Adult Attachment Interview and children’s disorganized attachment observed in the Strange Situation Procedure, Ainsworth and Eichberg (Citation1991) found a similarly strong effect size of r=0.60 (N = 45).

Again, correction for attenuation due to measurement error would bring these intergenerational associations into the range of 0.70 ~ 0.80 which must be considered uniquely strong effect sizes in the area of child development research. In fact Duschinsky (Citation2020) reminds us that Ainsworth clearly stated in her paper that, “after coding the sample a first time, she repeated her coding on the basis of changes made by Main to the coding manual, which led to the perfect correlation between unresolved loss and infant disorganized attachment”. Again, the combination of developing attachment measures and testing the intergenerational hypothesis inevitably led to inflated and non-replicable associations. In the meta-analysis by Verhage et al. (Citation2016) on 95 samples (N = 4819) intergenerational transmission of attachment was confirmed to exist, but with much lower effect sizes for secure to autonomous transmission (r=0.31) and for unresolved to disorganized transmission (r=0.21) compared to the first, exploratory studies.

On the one hand a winner’s curse really has the effect of sending a curse upon (often young) researchers who do not manage to replicate the original results and are inclined to blame themselves or be blamed by others for their lack of experience or observational skills. Part of the protective belt around an emerging research program is to blame the researcher using inadequate measures and skills if he or she fails to confirm a central tenet of a budding theory (Lakatos, Citation1980). On the other hand, paradoxically the winner’s curse might be a blessing in disguise because it motivates a community of researchers to contribute to the research program which in the long run converges on a modified and weaker but still extremely relevant version of the original hypothesis. Without the pioneering studies some core components of attachment theory would not have been discovered and demonstrated to have considerable truth-value and practical implications. Maybe the dictum “ex malo bonum” (“Good out of bad”; Saint Augustine of Hippo) would fit this paradox. Without a protective belt of auxiliary hypotheses (such as refinements of coding systems, see Padron, Carlson & Sroufe, Citation2014) no fallible research program would survive its first fledgling stage (Lakatos, Citation1980).

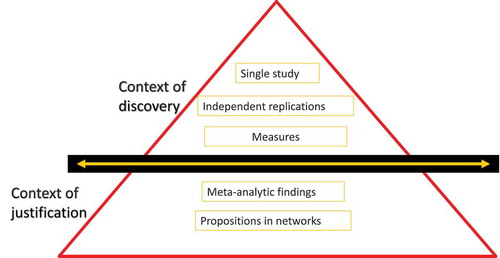

Context of discovery and justification

A winner’s curse is absolved of its bad reputation as soon as we differentiate between the context of discovery and the context of justification (Popper, Citation1959; Siegel, Citation1980), and avoid locating the pioneering studies in the context of justification. The problem of the original studies by Ainsworth, Main, and their students is not the improbably large effect sizes, but the naïve belief of their followers that the results would represent the truth instead of some fruitful hypotheses for further scrutiny in more strongly powered independent research. The pathfinding studies did produce useful measures to address core hypotheses of attachment theory but they were not equipped to validate the measures or test substantive hypotheses at the same time. Thus, the studies are no more (nor less) than exploratory pilots into uncharted territory. Even Main’s “guess and uncover” method to generate new coding systems (Duschinsky, Citation2020) is an inductive approach suggesting hypotheses that, like the outcome of Simon’s “logic” of scientific discovery (Simon, Citation1977), need stringent independent tests in the context of justification to be generalizable to new samples (Van Der Veer et al., Citation1983).

Furthermore, the power failure of the first, hypothesis-generating attachment studies should be ascribed to the lack of resources at the start of an innovative research program that forced the first generation of researchers to collect as much data from as few participants as possible because funding was extremely limited. Ainsworth complained about the very limited resources she could acquire through grants in competition with established research programs (Duschinsky, Citation2020). Fifty years ago the small initial samples only could produce publishable results if they took the hurdle of statistically significance in the Null Hypothesis Significance Testing tradition. And although “surely God loves the 0.06 nearly as much as the 0.05” (Rosnow & Rosenthal, Citation1989), there has been (and still is, unfortunately) an almost religious belief in the sanctity of the conventional alpha < 0.05. As a consequence, in small studies unlikely large effect sizes that with or without p-hacking (i.e. data-dredging until a “just significant” p-value is produced; Bruns & Ioannidis, Citation2016) just reach the alpha < 0.05 criterion are taken as established fact instead of being used as bold conjectures for further scrutiny (Popper, Citation1959). But without replications small underpowered studies also run the risk of premature translation to policy and practice (see ).

Attachment lost in translation?

The case of crying

Problems with feeding, sleeping and crying belong to the most taxing daily hassles that young parents have to cope with. Persistent crying during the first 6 months of life may, for example, trigger harsh and even abusive parenting such as smothering or shaking the baby in a substantial proportion of stressed parents (Reijneveld et al., Citation2004). Signs of postnatal depression or parental burn-out (Mikolajczak & Roskam, Citation2018) might often be related to these exhausting child-rearing issues. Parental demands for evidence-based advice have been sounding loud and clear for decades. Attachment theory suggests that infant crying is one of the primordial attachment behaviors that have the predictable outcome of the caregiver’s proximity and protection (Bowlby, Citation1982). In the Baltimore study Bell and Ainsworth (Citation1972) therefore focused specifically on infant crying and parental responses during the first year after birth. They summarized their main finding as follows: “ … the single most important factor associated with a decrease in frequency and duration of crying … is the promptness with which a mother responds to cries.” (Bell & Ainsworth, Citation1972).

This was a revolutionary, counter-intuitive result that led to precipitous translation to practice. Theoretically, it seemed a critical test of the controversy between attachment theory and learning theory about the way children’s behavior such as crying would be shaped: either terminated by prompt parental proximity or reinforced by immediate parental efforts to alleviate the distress. The design and statistical analyses of the controversial study were extensively criticized by Gewirtz and Boyd (Citation1977), who defended the conditioning perspective. In a rebuttal Ainsworth and Bell (Citation1977) emphasized the exploratory nature of their study and urgently called for replication. However, in the fierce competition at that time between the two research programs, the Baltimore cry findings were celebrated as a resounding victory of attachment theory. This may have blocked a potentially fruitful cross-fertilization between the two developmental theories for several decades (but see Bosmans et al., Citation2020; Juffer et al., Citation2017).

The outcome of the study on crying was prematurely translated into the practical advice that infant crying should be terminated quickly by close parental proximity and responsive interventions. Babies could not be spoiled by prompt responses to their cry signals. This advice was considered to be Ainsworth’s most important contribution to the popular parenting literature and related practices: “Though much of Dr. Ainsworth’s research was for an academic audience, it also had a practical side. She argued, on the basis of her research, that picking up a crying baby does not spoil the child; rather, it reduces crying in the future.” (Obituary in The New York Times 7 April 1999). The study on infant crying had great scientific impact and was cited more than 450 times, with countless references in the popular parenting literature.

Replication is “slow science”

Only few replications were attempted, and when they were published their fate was to remain largely ignored. Arguably the most extensive replication study was conducted by Hubbard (Hubbard & Van IJzendoorn, Citation1987, Citation1991) who replaced the imprecise post-visit narrative reports of paper-and-pencil registrations of infant crying and parental responses with event- and audio-recording. The longitudinal study on N = 50 mother-infant dyads across the first year of life included 12 home visits at 3-week intervals, with a mean total observation period per dyad of more than 21 hours (Hubbard & Van IJzendoorn, Citation1991). In contrast to the Bell and Ainsworth (Citation1972) study, the central finding of the replication based on cross-lagged multivariate analyses was that delayed instead of prompt responses to crying at earlier time-points reduced the number of cry bouts during the first half-year after birth. In the third quarter the pattern of crying seemed to be stabilized (Hubbard & Van IJzendoorn, Citation1991). Babies might be “spoiled” after all. This result did however not resonate in the discourse within attachment theory or in the public domain, with just 52 citations across 30 years, mostly in the pediatric cry literature (e.g. Barr, Citation1990).

From the perspective of “slow science” (Van IJzendoorn, Citation2019) it would have been equally premature to advise parents to promptly respond to their infant’s crying on the basis of the Baltimore study or, alternatively, to recommend delayed parental responses suggested by the replication study. With only a few correlational studies available we should refrain from catchy slogans (“babies can/cannot be spoiled”) that turn a complex scientific debate into a one-dimensional and misleading caricature. As Sroufe noted in his critique of “attachment parenting”: “Attachment is not a set of tricks”, such as prompt responding to crying (in Divecha, Citation2018). The lesson learnt the hard way in the biomedical sciences is that premature translation of exploratory study results may lead to unforeseen iatrogenic side-effects.

Translating attachment measures?

From a translational perspective, attachment measures seem most ready to be applied, in particular in clinical diagnosis and court decision-making (Van IJzendoorn et al., Citation2020). The reliability and validity of the Strange Situation Procedure and the Adult Attachment Interview demonstrated in psychometric studies and meta-analyses appear to be a guarantee for responsible application. For example, disorganized attachment is strongly associated with experienced child maltreatment: in some studies even more than 80% of the maltreated children were observed with disorganized attachment (Cyr et al., Citation2010). This leads to a situation in which clinicians tend to agree with the statement that disorganized attachment assessment can be used to identify child maltreatment (Duschinsky, Citation2020; Granqvist et al., Citation2017).

The problem though is that meta-analytically the association between disorganized attachment and maltreatment experiences is much weaker than reported in some studies, and that not only maltreatment but also other adverse life experiences and cumulative risks around poverty elevate the chances to develop disorganized attachment (Cyr et al., Citation2010). Furthermore, the average intercoder reliability of ICC=0.64, established by 12 trained coders after a workshop in March 4–8, 2019 at the University of Cambridge is adequate for research purposes but fails to reach the standard requirement (>0.80) for diagnostic purposes (Elliott et al., Citation2020; Guilford, Citation1946). Valid research instruments for attachment will produce too many false positives and false negatives in individual diagnostics (Van IJzendoorn et al., Citation2018) even though they are perfectly fine for research of individual differences on the group level.

Translating replicated core propositions of attachment theory

Attachment theory might be loosely described as a Lakatosian research program (Van IJzendoorn & Tavecchio, Citation1987) with two main characteristics. First, attachment researchers share a “hard core” of solid statements that serve as the foundation for empirical work on the implications. An important component is the statement that attachment is an evolutionary developed innate bias in each newborn to seek proximity to a protective conspecific. Second, the research program emphasizes specific acceptable operationalizations of central concepts. Attachment and sensitivity are central concepts assessed with observations of verbal and nonverbal interactive behavior indicating (mental representations of) relationships in function of a potentially secure base and safe haven provision.

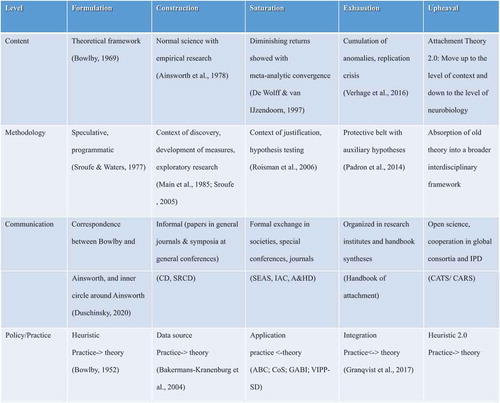

In we present an update of the four stages and four levels within these stages of attachment theory as a Lakatosian research program (for details see Van IJzendoorn & Tavecchio, Citation1987). After more than 30 years we add a fifth stage that seems to emerge (e.g. Duschinsky et al., Citation2021, this issue; Schuengel et al., Citation2021; this issue), with emphasis on interdisciplinarity, open science and global cooperation in response to the replication crisis.

Here we focus on applying attachment theory and suggest some replicated core propositions as key leads for translation to policy and practice. Three interrelated core propositions might be mentioned (partly overlapping with Forslund et al., Citation2021). The first proposition is the thesis that food is not the primary reinforcer of attachment but social interactions rooted in the innate bias of newborns to seek proximity to protective caregivers (Harlow, Citation1958). The second proposition is the need for continuity of caregiving arrangements and for prevention of fragmented care and of breaking attachment relationships (Bowlby, Citation1982). The third proposition concerns the indispensable value of a network of attachment relationships that a child (and parents) can fall back upon in times of (di-)stress (Hrdy, Citation2011).

The core propositions have been tested in a large series of studies on the deleterious effects of institutional child rearing that Bowlby (Citation1953) already labeled as fragmented care. Some 70 years and hundreds of detailed biobehavioral studies later it is clear that institutions should be considered structural neglect because of their regimented nature, high child-to-caregiver ratio, multiple shifts implied in 24/7 caretaking, and frequent changes of caregivers. Studies on institutional care reveal that even in well-equipped environments with sufficient food and medical care the absence of caregivers who can serve as stable attachment figures is highly detrimental for the children’s physical, neural, endocrine, cognitive, socioemotional and behavioral development. Longer stays in the institution predict larger developmental delays and atypical attachment development in a dose–response manner, but children show rapid recovery – also in a dose-response manner – after transition into a family-type caregiving arrangement through foster care, adoption, kinship care or kafalah. These conclusions are based on convergence of experimental and meta-analytic evidence (Van IJzendoorn et al., Citation2020), and they provide a firm basis for translation to policy and practice – if they are complemented with ethical considerations.

From is to ought?

In the beginning attachment theory and research seemed to try and avoid complicated ethical issues involved in central concepts such as “sensitive parenting” and “secure attachment”. On the recommendation of Bowlby who argued that these terms were “shot through with value judgements & hidden predictions” (Duschinsky, Citation2020) the various attachment classifications originally were designated with the first three letters of the alphabet, A – B – C to keep away from premature projection of (WEIRD) values on concepts that only served a theoretical purpose, not a practical aim. But public as well as scientific discourse about attachment began to reify secure attachment and sensitive parenting as morally desirable goals without much ethical reflections. This is a violation of Hume’s Law that one cannot derive an ought from an is, and that any valid argument leading to a normative conclusion must – perhaps implicitly – contain a normative premise (Elqayam & Evans, Citation2011). Jumping from is to ought without such a premise means committing a “naturalistic fallacy”.

Evolutionary inclusive fitness theory, life-history theory and cross-cultural models have proposed that it is not self-evident to evaluate a certain parenting style or attachment type as most optimal in all socio-economic or cultural circumstances. Instead they consider parenting and attachment from the more “value-free” perspective of adaptation to a specific niche (Hinde, Citation1982; Hochberg & Belsky, Citation2013). In life-history theory the term “adaptive” refers to reproductive fitness and “does not imply that a trait is socially desirable or conducive to well-being” (Ellis & Del Giudice, Citation2019). In a dangerous or poor environment harsh parenting and insecure attachment may benefit children’s inclusive fitness, for example, by their being more attentive to threat.

To avoid the counter-intuitive implication that parenting interventions should promote insensitive parenting additional ethical considerations are required. Just positing that “A secure attachment to parents for a child ought to be seen as a basic human right” (Steele, Citation2019) is a major jump from is to ought with the potentially dangerous implication that almost half of the children should be transferred to another family, and in some contexts (e.g. poverty) even a larger number. In an unpublished manuscript Bowlby (Citation1982, Citation1969) traced the etymology of “safe” to the Latin word “salvus” which is the absence of injury. However, he showed that “secure” originates from “se cura” which means being without a care. Every child may be entitled to a safe haven but a secure base cannot be a universal children’s right.

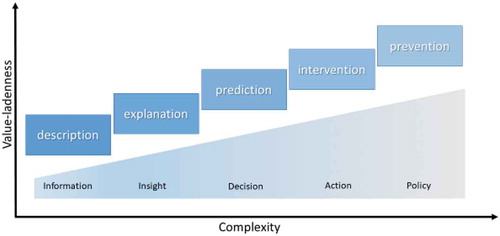

However, inclusive fitness theory, life-history theory and cross-cultural models also fail to deliberately take the step from the observation that in some unpredictable niches insecure attachments and harsh parenting might be adaptive, to the translational choice of either supporting parents to be harsh to their children or to empower them to change their harsh environments. For example, Ellis and his colleagues elaborated on the “hidden talents” model positing that children who survive and adapt to harsh and dangerous environments should not be condemned as “delayed” or otherwise developing in an atypical way. Instead their hidden talents should be used “to promote success in normative contexts” (see Ellis et al., Citation2020, ). Applied questions such as what “normative contexts” for these children mean and which alternative approaches could be used to empower parents to change their children’s harsh environment remain as yet unanswered. The closer we come to policy and practice, intervention and prevention, the more urgent ethical issues and choices become (see ).

Avoiding such choices, the concept of adaptation in the service of fitness only transfers the ethical issues to the justifiability of the social context (for example, a fast reproductive strategy for adaptation to the “fact” of poverty). Solving the ethical puzzles inherent in the concept of a “good-enough” parenting and child development might best be achieved through open communication about minimal ethical standards for a just society (Habermas, Citation1984/1987; Rawls, Citation1999). Bowlby’s, Ainsworth’s, and Main’s emphasis on the evolutionary expectable and natural adaptational value of parental sensitivity and child security would imply “a fundamental compatibility between man and society” (Stayton et al., Citation1971, p. 1059) but they ignore the need for an open discourse on socio-ethical standards – in fact a neglect of the ethical dimension not much different from life-history theory.

The idea of insecure attachments being “conditional strategies” (Main, Citation1990) and second-best options in adverse child-rearing environments underlines the “ontological” or “natural” status of secure attachments instead of the potential ethical superiority of this “default option”, and still requires ethical arguments to avoid committing the naturalistic fallacy. To her great credit, Main did not succumb to the temptation of becoming the next Spock or Brazelton: “Mary Main has never written about what parents should do, and she has emphasised in print that practitioners should not regard her tentative suggestions as authoritative for what they should do … ” (Duschinsky, Citation2020). In view of Bowlby’s role as public figure the restraint of most members of the first and second generation in going public is admirable. Maybe they remembered the example of Kohlberg (Citation1971) who tried but did not get away with the naturalistic fallacy in his theory of moral development. Hopefully this translational caution is transmitted across generations (Forslund et al., Citation2021).

Patient and Public Involvement

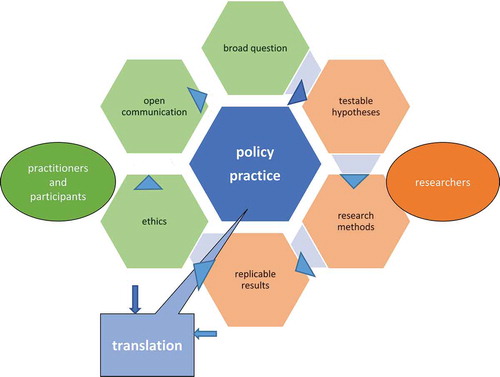

A crucial question is how to generate an ethical discourse about the translation of research findings to policy or (clinical) practice. Ethical discourse is not the expertise or exclusive right of researchers. The increasingly loud call for Patient/Participant and Public Involvement (PPI, Liabo et al., Citation2018) in research might offer an opportunity to start such a discourse for example, in randomized control trials on attachment-based interventions, to counteract the inadequate approach of health economics to calculate value for money of interventions (Van IJzendoorn & Bakermans-Kranenburg, Citation2020). Patient (or broader: Participant) and Public Involvement in research gives families who are the subjects and targets of intervention studies a voice in shaping the research agenda and addressing translational issues (see ). In a too radical version it would mean that participants are included in all stages of the research cycle (including data analysis) on an equal footing with the academics (Liabo et al., Citation2018).

However, division of expertise, responsibilities and tasks is essential for the quality of collaborative research in which everyone’s contribution is considered equivalent instead of equal (Van IJzendoorn, Citation2019). As researchers are experts in developing testable hypotheses, in selecting adequate methods to test these hypotheses, and in reproducible analysis and report of the data and findings, the participants should be involved in the first and final stages of the empirical spiral. They contribute to the selection and formulation of relevant domains and broad research questions, and in the final stage they can fill an important role in discussing the ethical implications of the study results and ways in which the findings can be implemented in policy and practice. Ethicists may be moderators of the open communication between researchers, practitioners and participants about inevitable moral choices throughout the research process.

The citizen assembly based on “sortition”, or the random selection of citizens to deliberatively propose social policy or legislative guidelines, might serve as an experimental model for such open communication (Van Reybrouck, Citation2016). Facing urgent challenges of accelerated climate change or growing social inequality, the deliberative road seems to slow down instead of catalyze the search for solutions addressing the challenges. Similarly, involving practitioners and participants in an ethical discourse as part of the research process may seem to ignore the urgency with which clinicians need to make decisions and to act, for example, in cases of child protection against (the risk of) family violence. At a minimum, children are entitled to grow up in a safe haven, but what this means and how to realize it is not easy to decide. Unfortunately, in the short run there are no quick and dirty solutions based on valid scientific measures or knowledge, so practitioners have to rely on their rich source of insights derived from previous experiences with children at risk. Only in the long run may the slow science of attachment support decision-making around diagnosis, prevention and intervention that create “good-enough” care arrangements for the developing child and the family involved (Van IJzendoorn et al., Citation2020).

Conclusions

Replicability is a necessary condition of responsible translation of scientific findings to policy and practice. Replication crisis and translational deficits – if not crisis – are intertwined and disturbing phenomena. Some core propositions have survived the conceptual, empirical and meta-analytic scrutiny of more than seven decades of attachment research: Attachment develops in social interactions building on the innate bias of newborns to seek proximity and protection; children need continuity of caregiving arrangements; and a network of attachment relationships may best guarantee the presence of a safe (but not always secure) haven for children. These replicated core propositions may be used as key leads for translation of attachment theory into policy and practice. However, replicable findings are necessary but insufficient to take the step from science to application. The gap between replication and translation, between is and ought, can only be bridged by open communication about “minima moralia” (Adorno, Citation1974) with participant and public involvement in research. Values are too valuable to be dismissed from the discourse in attachment theory and research.

Note

Based on an invited key note at the International Attachment Conference on “Science and Practice over the Lifespan”, Vancouver, Canada, July 18-20, 2019, and on a corona-cancelled contribution to the Cambridge symposium on “Attachment: retrospect and prospect”, organized by Robbie Duschinsky at Cambridge, Pembroke College, March 12-14, 2020. This paper was accepted for publication on September 9, 2020.

The work of MHVIJ was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, Spinoza Prize 2004. MJB-K was supported by the European Research Council (ERC AdG). MHVIJ and MJB-K were additionally supported by the Gravitation award of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO grant number 024.001.003).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adorno, T. W. (1974). Minima Moralia: Reflections from damaged life (E. F. N. Jephcott, Trans.). Original work published 1944-1951. NLB.

- Ainsworth, M. D., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment. Erlbaum.

- Ainsworth, M. D. S., & Eichberg, C. G. (1991). Effects on infant-mother attachment of mother’s experience related to loss of an attachment figure. In P. J. Stevenson- Hinde & P. Marris (Eds.), Attachment across the life cycle (pp. 160–183). Routledge.

- Ainsworth, M. D. S., & Bell, S. M. (1977). Infant crying and maternal responsiveness: A rejoinder to Gewirtz and Boyd. Child Development, 48(4), 1208–1216. https://doi.org/10.2307/1128477

- Baker, M. (2016). Is there a reproducibility crisis? Nature, 533(7604), 452–454. https://doi.org/10.1038/533452a

- Barr, R. G. (1990). The normal crying curve: What do we really know? Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 32(4), 356–362. https://doi-org.libproxy.ucl.ac.uk/10.1111/j.1469-8749.1990.tb16949.x

- Bell, S. M., & Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1972). Infant crying and maternal responsiveness. Child Development, 43(4), 1171–1190. https://doi.org/10.2307/1127506

- Bonapersona, V., Kentrop, J., Van Lissa, C. J., Van Der Veen, R., Joels, M., & Sarabdjitsingh, R. A. (2019). The behavioral phenotype of early life adversity: A 3-level meta-analysis of rodent studies. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 102, 299–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.04.021

- Bosmans, G., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Vervliet, B., Verhees, M. W. F. T., & Van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2020). A learning theory of attachment: Unraveling the black box of attachment development. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 113, 287–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.03.014

- Bowlby, J. (1953). Child Care and the Growth of Love. Pelican.

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Anxiety, stress and homeostasis. John Bowlby Archive, Wellcome Collections London, PP/Bow/H10.

- Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. [ Original work published 1969]. Attachment. Basic Books.

- Bruns, S. B., & Ioannidis, J. P. A. (2016). P-Curve and p-hacking in observational research. Plos One, 11(2), e0149144. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0149144

- Button, K. S., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Mokrysz, C., Nosek, B. A., Flint, J., Robinson, E. S. J., & Munafò, M. R. (2013). Power failure: Why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 14(5), 365–376. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3475

- Cyr, C., Euser, E. M., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & Van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2010). Attachment security and disorganization in maltreating and high-risk families: A series of meta-analyses. Development and Psychopathology, 22(1), 87–108. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579409990289

- De Wolff, M. S., & Van IJzendoorn, M. H. (1997). Sensitivity and attachment: A meta analysis on parental antecedents of infant attachment. Child Development, 68(4), 571–591. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb04218.x

- Divecha, D. (2018, May 2). Why attachment parenting is not the same as secure attachment. Greater Good Magazine. https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/why_attachment_parenting_is_not_the_same_as_secure_attachment

- Duschinsky, R. (2020). Cornerstones of Attachment Research in the Twenty First Century. Oxford University Press.

- Duschinsky, R., Bakkum, L., Mannes, J. M. M., Skinner, G. C. M., Turner, M., Mann, A., Coughlan, B., Reijman, S., Foster, S., & Beckwith, H. (2021). Six Attachment discourses: Convergence, divergence and relay. Attachment & Human Development.

- Elliott, M. L., Knodt, A. R., Ireland, D., Morris, M. L., Poulton, R., Ramrakha, S., Sison, M. L., Moffitt, T. E., Caspi, A., & Hariri, A. R. (2020). What is the test-retest reliability of common task-functional mri measures? New empirical evidence and a meta-analysis. Psychological Science, 31(7), 792–806. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797620916786

- Ellis, B. J., Abrams, L. S., Masten, A. S., Sternberg, R. J., Tottenham, N., & Frankenhuis, W. E. (2020). Hidden talents in harsh environments. In Development and Psychopathology (pp. 1–19). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579420000887

- Ellis, B. J., & Del Giudice, M. (2019). Developmental adaptation to stress: An evolutionary perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 70(1), 111–139. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011732

- Elqayam, S., & Evans, J. S. B. T. (2011). Subtracting “ought” from “is”: Descriptivism versus normativism in the study of human thinking. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 34(5), 233–248. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X1100001X

- Fanelli, D. (2018). Opinion: Is science really facing a reproducibility crisis. And Do We Need It To? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(11), 2628–2631. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1708272114

- Forslund, T., Granqvist, P., Van IJzendoorn, M. H., et al. (2021). Attachment and human development. Attachment goes to court: Child protection and custody issues. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2020.1840762

- Gewirtz, J. L., & Boyd, E. F. (1977). Does maternal responding imply reduced infant crying? A critique of the 1972 Bell and Ainsworth report. Child Development, 48(4), 1200–1207. https://doi.org/10.2307/1128476

- Granqvist, P., Sroufe, L. A., Dozier, M., Hesse, E., Steele, M., Van IJzendoorn, M. S., Schuengel, J., Fearon, C., Bakermans-Kranenburg, P., Steele, M., Cassidy, H., Carlson, J., Madigan, E., Jacobvitz, S., Foster, D., Behrens, S., Rifkin-Graboi, K., Gribneau, A., & Duschinsky, R. (2017). Disorganized attachment in infancy: A review of the phenomenon and its implications for clinicians and policy-makers. Attachment & Human Development, 19(6), 534–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2017.1354040

- Guilford, J. P. (1946). New standards for test evaluation. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 6(4), 427–438. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316444600600401

- Habermas, J. (1984/1987). The Theory of Communicative Action, Volumes 1 and 2. Beacon Press.

- Harlow, H. F. (1958). The nature of love. American Psychologist, 13(12), 673–685. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0047884

- Hinde, R. A. (1982). Attachment: Some conceptual and biological issues. In C. Murray Parkes & J. Stevenson-Hinde (Eds.), The place of attachment in human behavior (pp. 60–76). Basic Books.

- Hochberg, Z., & Belsky, J. (2013). Evo-devo of human adolescence: Beyond disease models of early puberty. BMC Medicine, 11, 113. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-113

- Hrdy, S. B. (2011). Mothers and Others. In The evolutionary origins of mutual understanding. Boston: Belknap Press.

- Hubbard, F. O., & Van IJzendoorn, M. H. (1991). Maternal unresponsiveness and infant crying across the first nine months: A naturalistic longitudinal study. Infant Behavior and Development, 14(3), 299–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/0163-6383(91)90024-M

- Ioannidis, J. P. A. (2005). Why most published research findings are false. PLOS Medicine, 2(8), e124. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124

- Juffer, F., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & Van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2017). Pairing attachment theory and social learning theory in video-feedback intervention to promote positive parenting. Current Opinion in Psychology, 15, 189–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.03.012

- Kohlberg, L. (1971). From is to ought: How to commit the naturalistic fallacy and get away with it in the study of moral development. In T. Mischel (Ed.), Cognitive Development and Psychology (pp. 151–235). Academic Press.

- Lakatos, I. (1980). The methodology of scientific research programmes. Philosophical papers. Volume I. Cambridge University Press.

- Liabo, K., Boddy, K., Burchmore, H., Cockcroft, E., & Britten, N. (2018). Clarifying the roles of patients in research. BMJ (British Medical Journal), 361, k1463. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k1463

- Main, M., Kaplan, N., & Cassidy, J. (1985). Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. In I. Bretherton & E. Waters (Eds.), Growing points of attachment theory and research. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50 (1-2, Serial No. 209) (pp. 66–104).

- Main, M. (1990). Cross-cultural studies of attachment organization: Recent studies, changing methodologies, and the concept of conditional strategies. Human Development, 33(1), 48–61. https://doi.org/10.1159/000276502

- Mikolajczak, M., & Roskam, I. (2018). A theoretical and clinical framework for parental burnout: The balance between risks and resources (BR2). Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00758

- Padrón, E., Carlson, E. A., & Sroufe, L. A. (2014). Frightened versus not frightened disorganized infant attachment: Newborn characteristics and maternal caregiving. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84(2), 201–208. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0099390

- Popper, K. (1959). The logic of scientific discovery. First English edition. London, New York: Routledge.

- Rawls, J. (1999). A Theory of Justice (rev edition). Harvard University Press.

- Reijneveld, S. A., Van Der Wal, M. F., Brugman, E., Hira Sing, R. A., & Verloove-Vanhorick, S. P. (2004). Infant crying and abuse. Lancet, 364(9442), 1340–1342. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17191-2

- Roisman, G. I., Fortuna, K., & Holland, A. (2006). An experimental manipulation of retrospectively defined earned and continuous attachment security. Child Development. 77(1), 59–71. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00856.x

- Rosnow, R. L., & Rosenthal, R. (1989). Statistical procedures and the justification of knowledge in psychological science. American Psychologist, 44(10), 1276–1284. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.10.1276

- Schuengel, C., Verhage, M. L., & Duschinsky, R. (2021). Prospecting the attachment research field: A move to the level of engagement. Attachment & Human Development.

- Siegel, H. (1980). Justification, discovery and the naturalizing of epistemology. Philosophy Articles and Papers, 7. https://scholarlyrepository.miami.edu/philosophy_articles/7

- Simon, H. A. (1977). Models of discovery and other topics in the methods of science. Reidel.

- Sroufe, L. A. (2005). Attachment and development: A prospective, longitudinal study from birth to adulthood. Attachment & Human Development. 7(4), 349–367. http://doi.org/10.1080/14616730500365928

- Sroufe, L. A., Waters, E (1977). Attachment as an organisational construct. Child Development. 48(4), 1184–1199. http://doi.org/10.2307/1128475

- Stanley, T. D., Carter, E. C., & Doucouliagos, H. (2018). What meta-analyses reveal about the replicability of psychological research. Psychological Bulletin, 144(12), 1325–1346. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000169

- Stanley, T. D., Carter, E. C., & Doucouliagos, H. (2018). What meta-analyses reveal about the replicability of psychological research. Psychological Bulletin, 144(12), 1325–1346. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000169

- Stayton, D. J., Hogan, R., & Ainsworth, M. D. (1971). Infant obedience and maternal behavior: The origins of socialization reconsidered. Child Development, 42(4), 1057–1069. https://doi.org/10.2307/1127792

- Steele, H. (2019). Commentary: Money can’t buy you love, but lack of love costs families and society plenty–a comment on Bachmann et al. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(12), 1351–1352. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13111

- Thaler, R. H. (1988). Anomalies: The Winner’s Curse. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2(1), 191–202. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.2.1.191

- Van Der Veer, R., Miedema, S., & Van IJzendoorn, M. H. (1983). Simons inductivistische benadering van de ontdekking [Simon’s inductivist approach to discovery]. Kennis En Methode, 7, 35–46.

- Van IJzendoorn, M., Bakermans-Kranenburg, H., Duschinsky, M. J., & Skinner, G. C. M. (2020). Legislation in search of ‘good-enough’ care arrangements for the child: A quest for continuity of care. In J. G. Dwyer (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Children and the Law (pp. 129–153). Oxford University Press.

- Van IJzendoorn, M., Bakermans, H., Steele, J. J. W., & Granqvist, P. (2018). Diagnostic use of Crittenden’s attachment measures in family court is not beyond a reasonable doubt. Infant Mental Health Journal, 39(6), 642–646. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21747

- Van IJzendoorn, M. H. (1994). Process model of replication studies: On the relations between different types of replication. In R. van der Veer, M. H. Van IJzendoorn, & J. Valsiner (Eds.), On reconstructing the mind. Replicability in research on human development (pp. 57–70). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

- Van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Tavecchio, L. W. C. (1987). The development of attachment theory as a Lakatosian research program. In L. W. C. Tavecchio & M. H. Van IJzendoorn (Eds.), Attachment in Social Networks: Contributions to the Bowlby– Ainsworth Attachment Theory (pp. 3–31). Elsevier Science.

- Van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2019). Addressing the replication and translation crises taking one step forward, two steps back? A plea for slow experimental research instead of fast “participatory” studies. In S. Hein & J. Weeland (Eds.), Alternatives to Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) in studying child and adolescent development in clinical and community settings. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 167, 133–140.

- Van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. (2020). Problematic cost-utility analysis of interventions for behavior problems in children and adolescents. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 172, 89–102.

- Van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Hubbard, F. O. A. (1987). De noodzaak van replicatie-onderzoek naar gehechtheid [The necessity of replication research on attachment]. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Psychologie, 42(3), 291–298.

- Van Reybrouck, D. (2016). Against elections: The case for democracy. Bodley Head.

- Verhage, M. L., Schuengel, C., Madigan, S., Fearon, R. M. P., Oosterman, M., Cassibba, R., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & Van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2016). Narrowing the transmission gap: A synthesis of three decades of research on intergenerational transmission of attachment. Psychological Bulletin, 142(4), 337–366. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000038