ABSTRACT

Recent social movements have illuminated systemic inequities in U.S. society, including within the social sciences. Thus, it is essential that attachment researchers and practitioners engage in reflection and action to work toward anti-racist perspectives in the field. Our aims in this paper are (1) to share the generative conversations and debates that arose in preparing the Special Issue of Attachment & Human Development, “Attachment Perspectives on Race, Prejudice, and Anti-Racism”; and (2) to propose key considerations for working toward anti-racist perspectives in the field of attachment. We provide recommendations for enriching attachment theory (e.g. considering relations between caregivers’ racial-ethnic socialization and secure base provision), research (e.g. increasing the representation of African American researchers and participants), and practice (e.g. advocating for policies that reduce systemic inequities in family supports). Finally, we suggest two relevant models integrating attachment theory with perspectives from Black youth development as guides for future research.

Attachment theory has roots in East Africa: Mary Ainsworth conducted her foundational observations with Black mothers and infants in Uganda, and she provided detailed ethnographic descriptions of the context in which those observations took place (Ainsworth, Citation1967). Ainsworth was hesitant to make universal claims without sufficient evidence and for this reason was enthusiastic about cross-cultural research (Duschinsky et al., Citation2020). Her view embraced both the universal human capacity for love and relationships as well as cultural variation in their expression: “I think that environmental influences play no significant role in the infant’s basic need for an attachment figure who can be trusted. But culture-related differences in ecologies and expectations will certainly affect how some specific aspects of that organization are expressed” (Ainsworth & Marvin, Citation1995, p. 8). Since then, at least two decades of exceptional cross-cultural work (for reviews see Mesman, Citation2021; Mesman et al., Citation2018, Citation2012, Citation2016; Posada et al., Citation1995, Citation2016) has documented patterns of caregiving and attachment in hundreds of studies in over 25 non-Western countries, including observations of multi-caregiver networks (for a review see Howes & Spieker, Citation2016).

What is missing from this work, however, is adequate attention to the unique context of African American families – a context that includes the intergenerational trauma of slavery, the legacy of Jim Crow, ongoing racist policies that disproportionately harm families of color, daily experiences of discrimination, and the current Black Lives Matter movement, as well as the “ordinary magic” of cultural strengths, joy, and family resilience (Masten, Citation2015; Murry et al., Citation2018; Tyrell & Masten, Citation2021). These contextual factors are consequential for the parent–child relationship and for parents’ efforts to provide protection and safety in a racist world. Further, with regard to both researchers and participants, the field of attachment has been exclusionary (Causadias et al., Citation2021): The research on attachment in African American families is very limited. Moreover, there have been almost no examples of how attachment research might be linked to the thriving literature on African American families and Black youth development conducted by scholars of color in other research traditions (e.g. Barbarin et al., Citation2016; Coard & Sellers, Citation2005; Dunbar et al., Citation2017, Citation2021; Graham, Citation2018; Halberstadt & Lozada, Citation2011; Murry et al., Citation2018, Citation2014).

It is within this broader context – the historical roots of attachment theory, the development of attachment research and methods along pathways largely separate from concurrent work on African American family processes, and the current moment of racial reckoning in the U.S. – that the present dialogue between scholars studying attachment and Black youth development came to be.

Accordingly, the aims of this paper are twofold: (1) to share some of the conversations, debates, and insights generated in the exchanges among a set of authors, reviewers, editors, and commentators from diverse backgrounds involved in the 2021 special issue of Attachment & Human Development, “Attachment Perspectives on Race, Prejudice, and Anti-Racism;” and (2) to map several guiding considerations for working toward anti-racist perspectives in the field of attachment going forward. Anti-racism is the active process of (a) affirming the idea that racial groups are equal (i.e. no racial group is inherently superior or inferior to any other racial group), and (b) acting to oppose racism and promote equity by changing attitudes, practices, policies, organizational structures, and systems (Bonnett, Citation2005; Kendi, Citation2019). Anti-racism can be conceptualized as a developmental process in that it (1) is ongoing (i.e. there is no end point in “becoming” an anti-racist field or individual); (2) evolves over time to meet new situations; and (3) is shaped through social experiences, critical inquiry, and reflective processes (Kendi, Citation2019).

Thus, this paper offers a starting point for working toward anti-racist perspectives in attachment. Reflecting the scope of this volume, we focus on racism against Black children and caregivers within the United States, but many core ideas may be relevant to other social groups and contexts. Further, we note that because of the history of racist policies in the U.S. (Kendi, Citation2019), African American families face disproportionate rates of poverty (U.S. Census Bureau, Citation2020) and as a result, race and class are often confounded in psychological research. Although disentangling race and class is beyond the scope of this paper, we follow previous developmental scholars in discussing them as distinct but intersecting factors that inform the experiences of children and families (see, e.g. Johnson, Citation2000).

Considerations for attachment theory

A relevant critique of the field of attachment is that it is culturally insensitive and does not fully reflect the developmental context or capture the nuances of parent–child relationships in African American families (e.g. Keller, Citation2018), and this critique merits consideration (see, e.g. Mesman, Citation2018). What is not always clearly specified is whether such critiques lie with the theory itself (i.e. its central tenets regarding the formation of parent–child bonds, the nature of caregiving behaviors that most directly shape individual differences in development), the related research (i.e. questions, methods, participants, interpretation of findings), or its applications (e.g. prevention and intervention efforts, clinical practice, policy). Examining these specific components is necessary for any field to clarify what needs to be changed and why, in order to make constructive progress in moving the field forward. To that end, we here consider theory, research, and practice separately and for each describe our views of the current state of the field and areas for critical exploration. We first lay out some core elements of the theory and raise questions regarding what further research is needed to determine where the theory holds, as well as what aspects may need to change.

Historical roots

Against a historical backdrop of Freudian theory and behaviorism – which asserted that parental love was at best the conditioning of dependency and at worst “a dangerous instrument” that undermines children’s growth toward independence (Watson, Citation1928) – Bowlby began to question Western psychology’s fundamental assumptions about the nature of love.

His work grew from two central observations: one about how humans evolved as a highly social species, and one about how children’s unique environments gave rise to individual differences in psychological development. First, Bowlby observed that infants appeared specifically and intensely attached to their caregivers. He proposed that forging close “attachment bonds” was not a sign of pathological dependence, but rather a normative, biologically-based process that evolved to protect children from threats in the environment during vulnerable periods of development, thus enhancing reproductive fitness (Bowlby, Citation1969/1982). Now widely accepted (Shonkoff & Phillips, Citation2000), this idea that human beings are hard-wired for relationship was among the first neo-evolutionary theories (Simpson & Belsky, Citation2016). Second, Bowlby’s observations in clinical training of “44 juvenile thieves” revealed that all of these troubled youth shared a common history of loss or extended separations from their mothers (Bowlby, Citation1944). In combination with observations of children separated or orphaned in the wake of World War II, this led Bowlby to hypothesize that differences in children’s experiences of access to a caregiver underlie meaningful differences in psychological development. This notion, too, is now widely accepted (Fearon & Belsky, Citation2016).

At the time, these were radical ideas. Yet Bowlby started small and focused: Initially, he studied mothers, presuming that they were primary caregivers, with little attention to fathers or extended family members (though later work came to include family systems); he conceived of a child’s attachment to a specific individual caregiver (while acknowledging the possibility of multiple caregivers); he wrote about infants’ attachment behavior, and later about adults’ caregiving behavior (though he conceptualized attachment as a lifespan construct). But reflecting the limitations of his era and social position (as a White, British scholar writing in the 20th century), Bowlby focused on the universal function of the attachment system in the context of evolution and not at all on cultural contributions that are currently understood as socio-political forces, racism, wealth, or power – this despite citing Bronfenbrenner, invoking anthropological data from non-Western societies, and recognizing the importance of environmental context on children’s development (Bowlby, Citation1969/1982, Citation1973, Citation1980, Citation1988).

Since Bowlby’s early writings, the theory has incorporated observations in non-Western cultures (Ainsworth, Citation1967; Mesman et al., Citation2016; Posada et al., Citation1995, Citation2016); attention to fathers and other caregivers (Bretherton, Citation2010; Grossmann & Grossmann, Citation2020; Seibert & Kerns, Citation2009), as well as multi-caregiver arrangements (Howes & Spieker, Citation2016); attachment processes in adolescence and adulthood (Ainsworth, Citation1989; Allen & Tan, Citation2016; Shaver & Mikulincer, Citation2009); and models of ecological factors that influence attachment and caregiving, including social class (Belsky, Citation2005; Belsky & Isabella, Citation1988). Bringing attachment theory into the current socio-historical moment, we believe this is a pivotal time to integrate a critical understanding of the varying ecological contexts that shape attachment relationships among African American families specifically. Given Bowlby’s sensitivity to the complexities of children’s environmental contexts, we can only assume that he would have been excited to learn more about how specific dimensions of context – namely, racial identity and experiences of racism among African American families – might factor into his initial conceptualization.

An evolutionary basis for love

Drawing on ethological and anthropological data, Bowlby (Citation1969/1982) advanced the theory that human infants evolved a tendency to form strong emotional bonds to caregivers, that the function of such bonds is to increase proximity to caregivers in times of threat, and that such proximity is adaptive, increasing infants’ probability of survival in the face of threats in their unique environment. This is the “universality” claim in attachment theory: that all human children need care and connection, and that these needs serve the goal of using a caregiver as a secure base to derive safety and comfort, as well as confidence to explore the world.

Data support this central claim: Infants form strong attachment bonds to one or more caregivers in every culture studied to date (Mesman et al., Citation2016), including in African American families (see Malda & Mesman, Citation2017). Thus, we suggest that applying the universality claim to African American children (a) is supported by the data; further, when interpreted from an anti-racist perspective, it (b) asserts Black children’s core human right to, need for, and capacity for close relationships; and (c) may be leveraged to refute racist policies and practices that systematically separate families of color (see policy discussion below).

Bowlby also suggested that humans evolved systems of behavior with various adaptive functions across development: Children’s attachment behaviors (e.g. crying, reaching, approaching) are directed to a caregiver, and serve to gain closeness, particularly when distressed. As children develop, these behaviors change in their form (e.g. teens texting their parents for help) and the figures to whom they are directed (e.g. close friends, trusted teachers/coaches, romantic partners). Adults’ caregiving behaviors include provision of a secure base from which a child can confidently explore the world and build autonomy, as well as a safe haven to which the child can return for connection, comfort, and safety when needed. As children develop, caregiving behaviors also change in their form (e.g. parents talking their 10-year-old through a difficult situation at school) and primacy (e.g. parents ceding some caregiving roles to teens’ close friends and romantic partners in late adolescence and early adulthood). Children may show attachment behaviors to multiple individuals, such as older siblings and extended kin, depending on the situation and organization of their caregiving network; adolescents, for example, may turn to close friends for support with a problem at school but seek out parents in emergency situations (Rosenthal & Kobak, Citation2010).

Attachment and culture

Both attachment and caregiving behaviors vary in their unique forms across cultures, but share the common underlying function of establishing or maintaining safety and connection. When considering attachment in African American families, it is worth asking: (a) who serves as a secure base/ safe haven to this child, and in what situations? Though much research on Black youth development similarly highlights the central role of mothers (e.g. Murry et al., Citationthis issue), other work underscores the role of fathers (e.g. Tyrell & Masten, Citation2021), mentors (Billingsley et al., Citation2020), grandmothers and extended family, spiritual community members, and fictive kin (Stewart, Citation2007) in providing safety, support, encouragement, comfort, and emotional closeness. Recognizing and measuring the multiple sources of secure base support that Black children tap into may provide a richer picture of their attachment network and enhance the predictive power of attachment models. It may also shed light on the conditions and limits of Bowlby’s (Citation1969/1982) concept of monotropy – the idea that children tend to form a hierarchy of attachment figures, in which one caregiver is typically primary. A second question is (b) how do racialized experiences influence African American children’s attachment behavior? For example, in response to an experience of bias-based bullying at school (see Mulvey et al., Citation2018), a Black child may feel safer expressing emotions to a same-race peer or parent than to a White peer or teacher, even while turning to those individuals as a secure base in other situations. When considering caregiving in African American families it is also worth asking: (c) what are the common and unique forms of caregiving behavior that African American caregivers have developed to adapt to the ecological context of class- and racism-related threats? (For discussion of the adaptive calibration model, see Del Giudice et al., Citation2011; Gaylord-Harden et al., Citation2018.) We turn to further discussion of caregiving next.

Caregiving and individual differences in attachment

Within human beings’ universal tendency to form close relationships, Bowlby proposed that individual differences emerge as a result of unique experiences within those relationships. Specifically, he proposed that variation in caregiving behavior shapes individual differences in how infants’ attachment becomes organized (Bowlby, Citation1969/1982, Citation1973, Citation1980), such that infants learn to calibrate their attachment behavior via adaptive strategies for getting their needs for proximity and connection met (Main, Citation1990). Children who experience consistent, reliable, responsive care in times of need learn that they can rely on a secure base with confidence and develop a secure attachment, characterized by autonomous exploration, open and direct expression of attachment needs, easy soothability when distressed, and expectations that others will be responsive and helpful. Children who experience rejecting or emotionally unavailable care learn that they must downplay their needs to avoid the pain of rejection and develop an insecure-avoidant attachment, characterized by minimized expression of attachment needs and expectations that others will be unresponsive or rejecting. Children who experience inconsistent or intrusive care develop an insecure-anxious (or “resistant”) attachment, characterized by heightened expression of attachment needs, anger, difficulty being soothed when distressed, and expectations that others are unreliable.

Ainsworth conducted the first observations of caregiving and attachment behavior with Black mothers and infants during her research in Uganda (Ainsworth, Citation1967); these observations formed the basis for her conceptualization and measurement of maternal sensitivity (Ainsworth, Citation1969), which was later consolidated with a sample of White middle-class mothers in Baltimore (Ainsworth et al., Citation1978). Sensitivity is defined as a caregiver’s “ability to perceive and to interpret accurately the signals and communications implicit in her infant’s behavior, and given this understanding, to respond to them appropriately and promptly.” Ainsworth’s original Maternal Sensitivity Scales (Ainsworth, Citation1969) included 5 dimensions: sensitivity vs. insensitivity to the infant’s signals, cooperation/ support for autonomy vs. interference with ongoing behavior, psychological and physical availability vs. unavailability, and acceptance vs. rejection of the infant’s needs. The theory holds that maternal sensitivity predicts children’s secure attachment (i.e. confidence in availability of secure base when needed), and substantial data support this link across cultures (Mesman et al., Citation2016).

Though research with African American families is sparse, this work generally shows somewhat lower levels of maternal sensitivity and rates of attachment security in African American families compared to other groups studied (for a review see Malda & Mesman, Citation2017). Notably, however, some studies that probed contextual sources of family stress show that apparent racial differences in sensitivity may be largely accounted for by socioeconomic stressors (e.g. housing insecurity), in keeping with the Family Stress Model (Bakermans-Kranenburg et al., Citation2004; Malda & Mesman, Citation2017; Mesman et al., Citation2012).

Importantly, data show that sensitivity as typically measured accounts for only 6% of the variance in attachment security even in predominantly White community samples and just 2% in low-socioeconomic status (-SES) samples (De Wolff & van IJzendoorn, Citation1997). Recently, some researchers studying low-SES families (48% African American, 19% White, 15% Hispanic, 16% multiracial) showed that a newly developed home observation measure of secure base provision (including chest-to-chest soothing of distress, responsiveness even following a delay or apparent “insensitivity”) is 8-fold more predictive of attachment security than are traditional measures of sensitivity (Woodhouse et al., Citation2020). A key question that follows from this work is whether secure base provision is similarly predictive of attachment security in African American families, and whether it takes similar or different forms, taking into account SES-related stressors.

An important next step is to integrate theory and research on African American families to better conceptualize and measure the forms of caregiving that best predict secure attachment and positive outcomes. What helps Black children feel a sense of security, safety, and comfort in times of stress, as well as confidence to explore and act upon their world despite racism-related threats? To address these questions, researchers can bring together findings from the fields of both attachment and Black youth development to examine potential precursors of secure attachment in Black families. For example, converging evidence from both fields points to the promotive effects of caregiving behaviors such as: (a) effective co-regulation of distress, (b) support for child’s autonomy and safe exploration – within the constraints of children’s unique environment, and (c) experiences of mutual delight and joy.

Importantly, the specific caregiving behaviors supporting Black children’s secure attachment may change with development. For researchers examining infants, a fruitful starting point may be to incorporate dimensions of secure base provision, such as touch and physical co-regulation of distress (Woodhouse et al., Citation2020), rather than caregiving behaviors that may be less important to infants and that may be more prone to biased interpretations (e.g. tone of voice, verbal reprimands). Early childhood researchers may find it useful to consider Dunbar et al.’s (Citation2021) suggestion that caregivers’ preparation for bias, in combination with emotional support and moderate suppression in response to children’s distress, may constitute a culturally specific form of secure base provision that serves to equip Black children to regulate emotions in the context of racism in the United States. In adolescence – as attachment needs shift toward emotional (vs. physical) closeness and teens move toward greater independence – caregivers’ balance of support for teens’ autonomy and relatedness (i.e. availability for connection and support) are considered key ingredients for secure attachment (Allen & Tan, Citation2016). For caregivers seeking to protect their teens from racism-related threats, however, support for autonomy may be restricted in ways that are adaptively calibrated to the family’s environment. Further, support for autonomy may include culturally specific supports for teens’ exploration of their racial identity, while relatedness may include processing difficult emotions related to experiencing or witnessing racism.

Relatedly, a fundamental question to examine regarding the theory’s tenets about security-promotive caregiving is: To what extent are Black caregivers’ racial-ethnic socialization (RES) practices – such as preparation for bias and racial pride messages – a core feature of secure base provision in African American families (as proposed by Dunbar et al., Citation2021) vs. a unique contributor to positive development among Black youth that may act alongside or interact with secure base provision? On the one hand, it could be argued that preparing children to deal with a racist world and instilling confidence in their intrinsic worth despite demeaning messages cannot be separated from the core caregiving behaviors that support Black children’s feelings of security within the caregiver–child relationship. The behaviors parents engage in to warn and to protect children from racism cannot be reduced to mere cognitive instruction; they are emotional and relational processes that anticipate future currently unseen threats. In this way, RES overlaps with secure base provision in that it may function to draw the child closer to parents (i.e. increasing or maintaining proximity) and to allow for safer exploration of the environment. Further, the extent to which RES matters for secure base provision may depend on families’ broader environmental context: For example, for a family living in a neighborhood in which racism is deeply engrained, RES may be more relevant to secure base provision – contributing both to children’s safety in their environment and to children’s trust in their caregivers – compared to families who are less impacted. This would mean that RES is one of multiple dimensions of secure base provision that may be of particular relevance to African American families (see Coard Citationthis issue).

On the other hand, both Bowlby and Ainsworth distinguished between attachment processes and socialization, conceptualized as distinct but important predictors of child outcomes (Ainsworth et al., Citation1974). This second view – that secure base provision and RES are independent constructs with unique and interactive effects on positive Black youth development – would mean that children may develop a secure attachment to a caregiver even if that caregiver engages in very little RES (but is otherwise highly responsive to children’s needs); conversely, children may develop an insecure attachment to a caregiver who engages in high levels of RES but struggles to respond to children’s other emotional needs. These possibilities should be tested empirically – particularly in middle childhood, when RES becomes increasingly relevant. With regard to interaction effects, data suggest that securely attached children are more likely to accept and internalize their caregivers’ socialization of conscience (Kochanska et al., Citation2004). Similarly, it is possible that Black children of parents who provide a reliable secure base are more likely to accept and internalize their caregivers’ RES messages, whereas insecurely attached children may be more resistant to their caregivers’ RES efforts. Alternately, the effects of RES and secure base provision may be mutually reinforcing over time – that is, Black children’s trust in their caregiver as a secure base may magnify the promotive effects of RES, and RES may further enhance the benefits conferred by secure base provision. At this juncture, more research is needed to understand the relation between RES and secure base provision; as a starting point, we recommend conceptualizing RES as distinct from secure base provision, given their unique research traditions and forms of assessment, but to generate models that integrate both constructs to examine points of connection and conceptual overlap.

Predicting developmental outcomes

A final core tenet of attachment theory is that individual differences in attachment shape development across the life span. Data in diverse samples show that secure attachment predicts a host of positive outcomes, such as lower rates of psychopathology (Fearon et al., Citation2010; Groh et al., Citation2012); emotional and physiological self-regulation of stress (Calkins & Leerkes, Citation2011; Cassidy, Citation1994; Cassidy et al., Citation2013); social competence and positive peer relationships (Groh et al., Citation2017); and increased empathy (Stern & Cassidy, Citation2018) and prosocial behavior (Gross et al., Citation2017; Shaver et al., Citation2016; for evidence in a majority African American sample of preschoolers, see Beier et al., Citation2019).

A key mechanism by which attachment is thought to influence later developmental outcomes is via mental representations or internal working models (IWMs) – experience-based cognitive and affective models of self and others that guide expectations, emotions, and behavior in the social world. Securely attached children develop models of the self as worthy of love and care – as unconditionally mattering to their caregiver – and as capable and effective in their environment, knowing that their caregiver “has their back” when needed. Confident expectations of one’s specific caregivers are thought to generalize to the broader social world, such that secure IWMs of others include expectations that new social partners will be generally trustworthy and helpful in times of need. (For reviews of theory and research related to attachment, IWMs, and social information processing, see Dykas & Cassidy, Citation2011; Bretherton & Munholland, Citation2008.)

Considering attachment IWMs in the context of a racist society raises several novel questions for models of Black youth development. We outline three questions regarding IWMs as a starting point for future work on this key mechanism:

What happens when positive models of the self, fostered within secure parent–child relationships, come into conflict with African American children’s exposure to racist messages from the larger society of “not mattering”?

Are certain features of insecure-avoidant IWMs – such as distrust, downplaying vulnerability and emotional needs – adaptive for staying safe in the context of racism?

To what extent is racial pride (e.g. a belief that “Black is beautiful”) an important component of Black youth’s secure models of the self and others in their racial group? Or is it a distinct construct that may be predicted by (or independent of) secure attachment IWMs? Is it possible for a Black child to have secure IWMs in every other respect (e.g. in their representations of parents, teachers, and peers) but not to have a positive or central racial identity? Researchers could examine whether the relation between racial identity and secure IWMs varies depending on children’s broader environment, such as the racial composition of their school or neighborhood and whether they perceive racism in their social environment.

By integrating perspectives from the field of Black youth development, attachment researchers can address the question, what are the core components of secure IWMs for Black youth?

Limits of the theory and areas for growth

Critically, as Sroufe (Citation2016) and others have pointed out, attachment “is not a theory of everything.” Developed to understand close interpersonal (typically dyadic) relationships, their development, and their role in individuals’ psychological functioning, the heart of attachment theory is at the interpersonal level. Relatedly, attachment is not a theory of racism; however, the theory’s focus on the central role of threat in understanding human emotion, cognition, social behavior, and development make it particularly relevant to discussions of racism for three reasons:

For individuals facing threats (e.g. discrimination, violence), having secure, supportive relationships may buffer against some (though not all) negative biopsychological consequences (Brody et al., Citation2006; Dotterer & James, Citation2018; Miller et al., Citation2014).

For individuals who harbor prejudiced attitudes or engage in acts of discrimination, attachment security may contribute to reducing prejudice and discrimination by decreasing misperceptions of threat, regulating neurobiological and behavioral stress responses, increasing empathy, and reducing defensiveness and aggressive behavior (Boag & Carnelley, Citation2012, Citation2016; Carnelly & Boag, Citation2019; Mikulincer & Shaver, Citation2001, Citation2021).

These interpersonal dynamics may be relevant to the systemic level if individuals in power (a) act out their own attachment dynamics (whether secure or insecure), with consequences for policies that shape institutions and systems; and/or (b) strive to provoke some population of individuals to feel insecure or untrusting via rhetoric that invokes threat (e.g. xenophobia) in order to maintain systems of power and dominance (see also Mikulincer & Shaver, Citation2021; Shaver et al., Citation2011).

Importantly, these systemic applications are not germane to the original theory and to many people may be “a stretch” without sufficient testing and application beyond the lab. Thus, a key growing point is to examine both the potential applications of attachment theory to understanding and addressing racism, as well as its limits.

One fruitful starting point would be integrating attachment frameworks with other theoretical traditions that center understanding of context and systems of power (Spencer et al., Citation1997). For example, the integrative model of developmental competencies in minoritized children (García-Coll et al., Citation1996) holds that families actively adapt to racialized environments via specific caregiving competencies that support minoritized youth’s positive social-emotional development. Another helpful conceptualization is the integrative model of stress in African American families (Murry et al., Citation2018, Citationthis issue), which demonstrates how systemic racism cascades through daily racialized stressors to impact parent–child relationship quality and youth mental health and social adaptation. To facilitate further research, we propose a potential integration of these models with key attachment processes in . This adapted model suggests that contextual factors in the lives of Black families cascade through family stress and adaptation (Murry et al., Citation2018, Citationthis issue) to inform caregivers’ secure base provision and in turn, children’s attachment, with downstream effects on children’s representations of self and others (IWMs) and social-emotional competencies. The model focuses on specific pathways linking context and attachment in Black families that could be tested in future research.

Figure 1. Integrative Models of Contextual Factors Influencing Positive Black Youth Development – as Proposed by García-Coll et al. (Citation1996), Murry et al. (Citation2018), and Murry et al. (Citationthis issue) – Adapted to Integrate Attachment Processes.

In addition, critical race theory (Bell, Citation1995; Delgado & Stefancic, Citation2017; see Gaztambide, Citation2021) underscores that race is not a biological attribute but a social construct (reflecting broad scientific consensus; e.g. Yudell et al., Citation2016), and that racism is not merely the result of individual bias or prejudice, but is embedded in programs, practices, and policies – involving subjugation and preferential treatment of one group over another. These systematic processes impact parenting and child development (Wilkinson et al., Citation2021). Intersectionality (Collins & Bilge, Citation2020; Crenshaw, Citation1989, Citation2011) provides a framework for understanding how multiple systems of oppression – such as racism, colorism, sexism, and classism – combine to shape individuals’ experiences in unique ways depending on one’s race, gender, color and class. An intersectional framework opens the field to new questions, such as:

How does racism interact with social class to shape attachment experiences for African American children? In what ways are the stressors associated with poverty and experiences of racism similar vs. unique in their effects on parent-child relationships (e.g. Roopnarine et al., Citation2005)?

Does attachment security buffer against the dual stressors of racism and sexism (“misogynoir”) among Black girls?

What are the unique sources of stress and forms of adaptation that characterize African American mothers (e.g. Leath et al., Citation2021), Black LGBTQ caregivers, and immigrant and refugee families?

For biracial children, how might attachment to each parent interact with racial identity development to predict mental health outcomes?

What are the specific secure base needs of queer youth of color coming out to their family or peers, and how can therapists facilitate parents’ ability to meet these needs?

One promising approach to integrating these perspectives into quantitative attachment research is Critical Race Quantitative Intersectionality (QuantCrit; Garcia et al., Citation2018; Gillborn et al., Citation2018), which integrates intersectionality and critical race theory into the application and interpretation of statistics (for applications to developmental science see Suzuki et al., Citation2021).

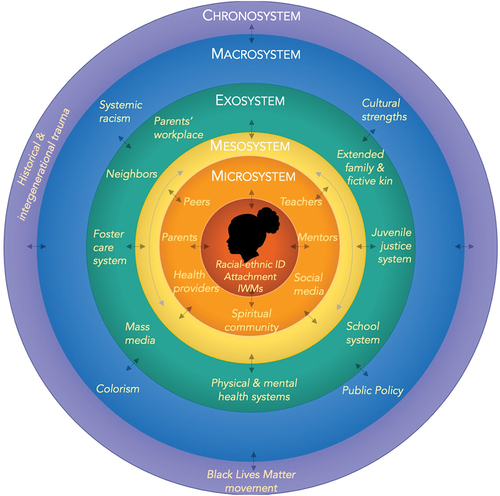

Another particularly relevant framework is Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1974) bioecological model, which highlights the central role of attachment in the child’s microsystem (e.g. “the mother-infant dyad as a context of development;” Bronfenbrenner & Morris, Citation2006, p. 815). Further, ecological perspectives have long been important in attachment theory (Belsky, Citation2005; Belsky & Isabella, Citation1988; Bowlby, Citation1969/1982; Cassidy, Citation2021). When applying this model to African American youth and families, it is important to include contextual factors that are particularly relevant to Black youth development, as identified in the work described above (García-Coll et al., Citation1996; Murry et al., Citation2018, Citationthis issue). To stimulate future research on attachment in African American children in context, we illustrate one possible adaptation of Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1974) bioecological model in . This adapted model includes many of Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1974) classic dimensions of context (e.g. the school environment), but also highlights attachment-related processes and specific contextual factors known to impact Black youth development, such as systemic racism and promotive factors such as spirituality and positive racial-ethnic socialization.

Figure 2. Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Model, Adapted to Focus On Black Youth Development and Attachment Processes in Context.

Leveraging the model in , researchers may consider how each factor shapes child outcomes via (a) their influence on caregivers’ capacity to provide a secure base, which impacts (b) children’s attachment security to that caregiver, and in turn (c) children’s broader sense of themselves as worthy, safe, and effective in their environment (i.e. generalized IWM of self and others). These adapted models are designed to generate novel research questions, as well as to contextualize existing findings at each level of analysis. For instance, in relation to Bronfenbrenner’s framework, researchers could ask how, within the microsystem, the development of an attachment relationship unfolds to a caregiver dealing with the chronic stressors of racism – both at different stages of development and also in relation to different types of caregivers (e.g. fathers, teachers). Within the exosystem, researchers could consider how more distal forms of support – from the neighborhood, spiritual community, or network of extended kin – could be strengthened as part of intervention work to buffer against toxic stress and increase support for Black caregivers, thus aiding their ability to provide a reliable secure base. Within the macrosystem, how might the intersection of racism and colorism cascade through children’s relationships to shape development, and could a secure internal working model of the self protect against internalized racism?

Thus, we emphasize that every concept contained within attachment theory will be enriched to the extent that researchers ask the question: Does this conceptualization hold in the context of families living with the realities of structural racism? Exploring such questions will shed light on which specific aspects of the theory hold or require changing or refinement, and crucially, which parts have yet to be sufficiently explored with African American families.

If this is to be a two-way conversation, it is necessary to share our thoughts about ways that Black youth development frameworks might be expanded to incorporate insights from attachment theory and research. In this regard, we suggest five attachment-related questions that, if explored, might enrich models of Black youth development:

To what extent do caregiver–child relationships shape Black youth development via children’s cognitive representations (internal working models) of the self and others?

Are the “active ingredients” of promotive caregiving behaviors those that buffer against stress or provide protection against threat (as opposed to, e.g. warmth)?

What is the role of mutual delight – or its more culturally specific form, “Black joy” – in fostering secure attachment relationships for Black youth?

Are caregivers who have a secure base themselves (e.g. from aromantic partner or from their family of origin) better supported to engage in positive racial-ethnic socialization with their children?

Do caregivers’ capacities for emotion regulation and reflective functioning (i.e. the ability to reflect on thoughts and feelings within themselves and others; Fonagy et al., Citation1991) help to process experiences of discrimination and buffer against potential negative effects on caregiving?

These questions, alongside the integrative models in , provide a roadmap toward greater cross-pollination of ideas between theories of attachment and Black youth development.

Considerations for research

Regardless of the extent to which the theory holds, multiple research issues merit attention. In this section, we consider factors that may influence the empirical work, ways in which these factors may have led to incorrect or biased findings, and potential steps to take to correct this.

Participants

Although the picture of participants in attachment research is increasingly diverse, there remains an overrepresentation of White, Western, educated, middle-class caregivers (mostly mothers) and children. What is most clear is that there is not nearly enough attachment research with African American families (Malda & Mesman, Citation2017). Empirical data focused on Black families – for example, data on what predicts secure attachment for Black children at different stages of development, what roles fathers and other caregivers play (Tyrell & Masten, Citation2021), and whether outcomes of secure attachment are similar or different from those of White children (e.g. Stern et al., Citation2021) – are essential in order to evaluate which parts of the theory hold or need to change. Such work requires that researchers increase efforts to include Black families as participants.

One starting point is to leverage existing datasets (e.g. NICHD Early Childcare Research Network dataset, Adolescent Health dataset) to conduct secondary analyses of attachment-related processes among African American populations (e.g. Bakermans-Kranenburg et al., Citation2004). Such work could focus exclusively on a subsample of Black participants (e.g. Ehrlich et al., Citation2019) or could utilize multigroup modeling to examine common and unique developmental pathways among multiple racial-ethnic groups (e.g. Stern et al., Citation2021). When comparing racial-ethnic groups, it is important not to treat White participants as the norm against which Black participants are measured, but rather to consider how specific ecological conditions may shape diverse, adaptive development pathways for each population of interest. When recruiting new samples, researchers can increase efforts to include African American participants – which may involve getting out of the lab and into more accessible locations, providing childcare for siblings, and engaging in long-term efforts to build trust and relationships with local communities (and recognizing where there may be a history of harm by researchers or research institutions that requires reparation).

Research team

One impetus for the Special Issue on attachment and anti-racism arose from the question, Why is the field of attachment so White? From the field’s founders to the authors in the Handbook of Attachment to the editorial board of Attachment & Human Development to the attendees at the International Attachment Conference, the majority as of this writing are Caucasian Western Europeans and Euro-Americans. Causadias et al. (Citation2021) quantify this lack of representation in their Special Issue commentary and highlight a number of factors that may contribute to it. What emerge are clear data that scholars of color are underrepresented in the field of attachment and that there is a need to question how the field can do a better job of including, supporting, and amplifying their scholarship.

First, attachment researchers can learn from and cite the work of scholars of color. Before embarking on new studies of attachment focused on Black youth and families, for example, it is particularly important to integrate the findings and perspectives of researchers who represent and have worked with African American populations (e.g. Anderson & Stevenson, Citation2019; Barbarin et al., Citation2020; Dunbar et al., Citation2017; N. E. Hill, Citation2006; R. B. Hill, Citation2003; Jones et al., Citation2020; Murry et al., Citation2001, Citation2018; Smith‐Bynum et al., Citation2016). Second, attachment researchers can forge collaborations with scholars of color, as well as with community leaders who best understand the needs of their community and are trusted by its members. Third, the field can invest in a more diverse next generation of attachment scholars by, for example, advocating for admissions, training, and retention policies that better support Black, Latinx, and Indigenous graduate students, clinical trainees, and undergraduate research assistants.

Methods

Turning to research methods, one potential issue is that applying traditional measures of sensitivity to African American caregivers may lead researchers to (a) overlook key features of adaptive caregiving specific to Black parents; (b) misinterpret aspects of caregiving (e.g. interpreting limits on children’s autonomy as interfering or controlling rather than as adaptive protections from ecological threats); (c) fail to account for contextual factors that shape caregiving behavior (both proximal factors such as the presence of White researchers and distal factors such as the vicarious trauma of witnessing police brutality), all of which may contribute to deficit narratives that cast Black mothers as “insensitive.”

When addressing these and related issues in observational measures, we make four suggestions. First, regarding data collection, it may be important to consider the race of the researcher who administers interview-based measures (including the Parent Development Interview, Working Model of the Child Interview, and Child and Adult Attachment Interviews), plays the role of the Stranger in the Strange Situation Procedure, or provides instructions as an experimenter in other measures of parent and child behavior. To what extent is the presence of a White researcher a potential stressor, a reminder of racism-related trauma, or otherwise a barrier to authentic and regulated self-expression for both caregiver and child? Research on interview methods from the fields of public health and sociology suggests that race-mismatch – that is, a White interviewer paired with a Black respondent – may affect responses due to social desirability, sensitivity to being judged, anxiety about not meeting the expectations of the interviewer, and stereotype threat; in contrast, respondents display great comfort and honesty when there is race-match with the interviewer (e.g. Davis et al., Citation2010). Therefore, consideration of the racial identites of research staff is crucial for administering measures of attachment and caregiving with integrity and for creating a space that is inclusive and safe for Black participants.

Second, turning to coding of behavioral data, we underscore recommendations by Malda and Mesman (Citation2017) that when working with African American samples, researchers make efforts to include African American members on coding teams. Data demonstrate that White observers show implicit emotional biases when viewing Black children and adults (e.g. Todd et al., Citation2016), and White researchers are not immune to such biases. The potential for bias may be less when coding is based on precise measurements (e.g. the number of seconds before a child approaches the parent, as in the Strange Situation; Ainsworth et al., Citation1978) than when codes rely on subjective assessments (e.g. tone of voice, in some measures of parental sensitivity). Further, researchers could develop novel attachment-focused measures of caregiving behavior that integrate African American perspectives on parenting, focusing on culturally specific paralinguistic and behavioral cues (e.g. touch, movement, humming or singing) that signal safety and acceptance in the context in which Black children grow up.

Third, when considering study designs that are sensitive to context, researchers using classic measures of attachment and caregiving could also include in the study well-validated measures from the field of Black youth development, including assessments of parental racial-ethnic socialization, exposure to racism, and youth racial identity development; such combinations of measures would help to test the unique and interactive pathways by which these constructs shape key developmental outcomes. Fourth, relatedly, it may be fruitful to test the ways in which attachment and caregiving behaviors become adaptively calibrated to the contexts in which Black children develop (see Del Giudice et al., Citation2011). For example, it is possible that secure attachment is best predicted by non-linear associations with, or interactions among, multiple dimensions of context (e.g. level of racism-related threat) and caregiving behavior (e.g. emotional support in combination with moderate limits on autonomy and high parental monitoring).

An additional issue is that that there are substantial barriers to more widespread use of attachment measures, including the costs, training, and laboratory space required for gold standard measures such as the Strange Situation (see Causadias et al., Citation2021). We offer three recommendations to begin addressing such barriers: First, offering collaborative opportunities with established attachment researchers and more accessible coder trainings online at reduced cost may be especially helpful for coding-intensive measures such as the Strange Situation and the Adult Attachment Interview. Second, researchers with constrained budgets can take advantage of well-validated and less costly questionnaire measures of attachment-related caregiving (e.g. the Coping with Toddlers’ [or Children’s] Negative Emotions Scale; Spinrad et al., Citation2007). For older children, there are several widely used self-report measures of attachment (e.g. Kerns Security Scales (Brumariu et al., Citation2018) and the Parent as a Secure Base Scale (Woodhouse et al., Citation2009), both validated for school-aged children; the Experiences in Close Relationships Scale (Brennan et al., Citation1998) and its short form (Wei et al., Citation2007), validated for adolescents and adults). Many of these measures have been translated into other languages, and some have been applied with African American families (see, e.g. Dunbar et al., Citation2021; Ehrlich et al., Citation2019, Citation2021; Stern et al., Citationthis issue). Third, beyond the lab, cultural psychologists have increasingly called for a return to attachment’s empirical origins – ethnographic field work (Keller, Citation2018). Though time-intensive and costly, such an approach removes certain barriers for researchers without access to the lab space needed for the Strange Situation, while also providing rich contextual information about families and their unique environments.

Context

Beyond socioeconomic status, the field of attachment has been slow to incorporate other measures of context identified by Black scholars as critical for understanding parent–child relationships among African Americans specifically – measures of systemic risks such as discrimination and economic inequities, as well as cultural assets such as positive racial socialization, African American spirituality, collective socialization, and “Black joy” (García-Coll et al., Citation1996; Gaylord-Harden et al., Citation2018; Murry et al., Citation2018; Tyrell & Masten, Citation2021). The failure to adequately address context in the field’s methods and interpretation of findings is consequential in two key ways: (1) there may be a tendency to essentialize or over-simplify findings regarding more “insensitive” parenting among Black mothers in particular, contributing to deficit narratives, while also (2) failing to recognize and validate parental “micro-protections” such as preparation for bias as forms of highly effective caregiving, which are adapted to the context of systemic racism and can be integrated and tested as security-promotive caregiving behaviors (Dotterer & James, Citation2018).

To help address this, attachment researchers can draw upon existing strong measures of context. The articles in the Special Issue on attachment and anti-racism provide a few starting points: Murry et al. (Citationthis issue) measure both mothers’ and children’s experiences of discrimination via self-report on the Schedule of Racist Events (Landrine & Klonoff, Citation1996). In secondary analyses of an existing dataset, Stern et al. (Citation2021) tap teens’ perceptions of neighborhood racism from a single item on the Neighborhood Environment Scale (Elliot et al., Citation1985). Other measures have been developed to tap experiences of racism in children ages 8–18 (e.g. Perceptions of Racism in Children and Youth; Pachter et al., Citation2010) and adults (e.g. Everyday Discrimination Scale; Williams et al., Citation1997; for a review of measures see Atkins, Citation2014), and a variety of methods exist for quantifying the effects of structural inequities (for a review see Groos et al., Citation2018). At the school level, Graham (Citation2021) suggests measuring the racial composition of the classroom – which is consequential for Black children’s experiences of discrimination, social support, and belonging at school – as well as teacher–student relationships (e.g. teachers’ capacity to provide a secure base for students of color). Integrating these and other contextual variables in future research which will allow for better understanding of how attachment processes play out as function of context (for related discussion see Osher et al., Citation2020).

Further, even if context is not explicitly measured in a particular study, context should still be accounted for in researchers’ interpretation of findings. This is especially important if a study finds that Black caregivers or children differ from previously established (and potentially biased) “norms” of caregiving or attachment metrics. For example, drawing on Murry et al.’s (Citation2018, p. Citationthis issue) model, researchers can situate findings regarding Black caregivers’ strengths and struggles within the context of historical and present-day sociopolitical factors, which include daily racism-related stressors known to impact physical and mental health (Clark et al., Citation1999; Harrell, Citation2000). Further, if comparisons are made to White middle- to upper-SES samples, researchers can contextualize findings within a discussion of such samples’ many sources of privilege and historical power/ hegemony. Applying such perspectives will (a) enrich our interpretations of attachment research findings, (b) enhance understanding of family processes and adaptation to environmental stressors, (c) excavate novel areas for research on context and parenting, and (d) counter deficit narratives that essentialize Black parents by acknowledging both systemic oppression and culturally specific adaptations.

Implications for policy and practice

Whether a given theory works toward racist or anti-racist ends hinges in large part on how it is applied. To the extent that attachment theory is applied in ways that reinforce deficit narratives about Black youth and caregivers, enforce White middle-class parenting norms as ideal in the absence of sufficient evidence in African American families, or present data in decontextualized ways that ignore or deny the role of systemic racism – then the theory is being used to promote racism by upholding White supremacist and colonialist ideas. On the other hand, if attachment theory is applied in ways that challenge and seek to dismantle these oppressive systems through research, policy, and practice, the theory stands to make a meaningful contribution to anti-racist efforts. We highlight a few (of many) possible ways that attachment can be leveraged in anti-racist action as a starting point for future efforts.

Advocating for anti-racist policy

One anti-racist policy application of attachment theory is to interpret its universality claim as a declaration of human rights: that is, the theory states that all children require and deserve access to a caregiver to support healthy development and therefore, that the disruption of access to a caregiver constitutes a violation of human rights, with disproportionate impacts on families of color. This claim is consistent with Articles 7, 8, and 9 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UN General Assembly, Citation1989; see also Dolan et al., Citation2020). Attachment theory and research provide decades of evidence for the long-term adverse impacts of family separation and loss and the mechanisms by which such effects occur (Bowlby, Citation1973, Citation1980). Separation from attachment figures removes the stress-buffering effects of caregivers and is itself a source of stress (Humphreys, Citation2019; Waddoups et al., Citation2019); such toxic stress in childhood has long-term adverse effects on brain development, mental and physical health, and behavioral outcomes (Shonkoff et al., Citation2012, Citation2021). Similar arguments have invoked attachment theory to oppose xenophobic policies that separate families at the U.S.-Mexico border (see Bouza et al., Citation2018; Coan, Citation2018; Lieberman et al., Citation2018; Teicher, Citation2018) and to advocate for policies that interrupt parent–infant separation by allowing infants to bond with their incarcerated mothers (e.g. Kanaboshi et al., Citation2017). It is worth noting that White supremacist and colonialist powers have historically used family separation as a tool of oppression: Family separation was endemic to the slave trade (King, Citation2011; Smith, Citation2021), as well as to Native American boarding schools in the 19th and 20th centuries (Olson & Dombrowski, Citation2020; Pember, Citation2019). Today, African American families continue to experience family separation via policies and practices that result in disproportionate rates of child welfare removals, school suspension and the “school-to-prison” pipeline, and incarceration of children and caregivers for nonviolent offenses (e.g. Barbarin, Citation2021; Kendi, Citation2019; Miller, Citation2018; U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights, Citation2016). Such policies are key targets for systemic change informed by attachment theory and research.

A second anti-racist policy application of attachment theory is to continue to advocate for better supports for caregivers to be able to provide a secure base for children, with particular attention to addressing racial inequities in caregiver supports. Attachment theory and research hold that caregivers’ own stress, access to secure relationships, mental and physical health, and trauma history contribute substantially to their capacity to provide a secure base (Belsky & Jaffee, Citation2006; Fearon & Belsky, Citation2016). This work has been invoked to advocate for policies that reduce family poverty; expand access to affordable quality prenatal and postnatal care, childcare, and physical and mental health care; and provide paid family leave (Bridgman, Citation2017; Cassidy et al., Citation2013; Plotka & Busch-Rossnagel, Citation2018; Shonkoff & Phillips, Citation2000). Crucially, in the U.S., racial inequities persist at every level of caregiver wellbeing and at every stage of development; for example, African American mothers experience elevated prenatal stress, higher rates of maternal and infant mortality, lower access to physical and mental health care, and greater housing and food insecurity (Wilkinson et al., Citation2021). As one recent policy brief explains, “The connection between maternal and child well-being is particularly important among women of color and their babies due to the intergenerational effects of and lived experiences with institutional and interpersonal racism” (Wilkinson et al., Citation2021, p. 1). Further, as Tyrell and Masten (Citation2021) note, Black men face disproportionate rates of incarceration, and the resulting forced separation from family can adversely impact fathers’ caregiving and children’s attachment (see also Cassidy et al., Citation2010). Thus, we encourage attachment scholars to leverage their knowledge of the importance of investing in caregiver wellbeing to advocate for evidence-based policies that specifically aim to reduce barriers to caregiver supports among families of color.

Imagining Anti-racist Clinical Practice

Many excellent ideas for anti-racist clinical practice have been proposed (see, e.g. Coard et al., Citation2004; Gaztambide, Citation2019, Citation2021; Kelly et al., Citation2020; Legha & Miranda, Citation2020; Maiter, Citation2009); further, a social justice framework is central to many models of counseling psychology (Hargons et al., Citation2017), social work (International Federation of Social Workers et al., Citation2012), and community psychology (Nelson & Prilleltensky, Citation2010). Here we highlight two themes of particular relevance to attachment-informed interventions.

First, as Gaztambide (Citation2021) suggests, attachment-based psychotherapy requires a move to the level of the sociopolitical that includes actively engaging and “mentalizing” issues of racial identity, social rank, and racism within the therapy space. Therapists with training in anti-racist practice may be better equipped to provide a safe space and secure base from which clients of color can explore issues of racial identity, discuss openly experiences of discrimination as well as cultural strengths, and address racism-related trauma. Such training is vital to therapists’ relational capacities to build trust, empathy, rapport, and a strong working alliance, which have been shown to predict positive treatment outcomes in children and adults (Comas-Díaz et al., Citation2019; Karver et al., Citation2018; Nienhuis et al., Citation2018; Vasquez, Citation2007).

Second, attachment-based parenting interventions can disrupt the racist legacy of pathologizing Black parents by adopting strengths-based approaches that affirm secure base practices specific to African American families and that contextualize parents’ behavior within the broader context of racism and historical trauma. As Coard (Citationthis issue) notes: “African American families are usually told what they are doing wrong and what they need to change, rather than what they are doing right and should continue. The positive caregiving practices used by African American parents need to be shared, validated, encouraged, and learned from.” When interveners make assumptions (for example, that because X parenting behavior leads to positive outcomes in White families, the goal should be to get Black families to do the same, in the absence of sufficient data), it can be unhelpful at best, or actively harmful. This underscores the importance of investing in a research base to examine attachment-relevant predictors of positive outcomes in Black families as the basis for interventions.

Concluding thoughts

Within the field of attachment, there remains an urgent need to “decolonize” specific aspects of theory (e.g. specifying the ecological context of racism in conceptualizing parent–child relationships in African American families), methods (e.g. measuring caregiving, integrating existing measures of contextual factors into studies examining attachment and caregiving), and research (e.g. increasing attention to African American populations, contextualizing interpretation of group-level differences). Decolonization has multiple layers of meaning, including (a) acknowledging the role of context and racism in children’s development, but also (b) interrogating cultural hegemony – the belief that one cultural group and its ways of thinking and being is superior to another, (c) allowing room for multiple perspectives, and (d) supporting the agency of marginalized people. For example, consider the dynamic aspects of a parent–child relationship in which circumstances require the child early in life to serve in a protector role for the family while at the same time still needing protection from threats: a boy becoming “the man of the house” when the father is unavailable, a teen becoming the economic provider for the family following a caregiver’s sudden loss of a job, or a child becoming the translator or “language broker” navigating a potentially threatening world among families of undocumented immigrants who speak only Haitian Creole. What does secure base provision look like here, accounting for the unique environmental threats that families must navigate? And whose view of sensitive or adaptive caregiving is privileged in these complex contexts?

The foundation of this work in the field of attachment must be relational – growing from a place of humility, curiosity, collaboration, reflection, and openness to feedback. What does it look like to actively question White Western samples as a comparative “norm,” as well as supposed “objectivity” of White Western scientists and interventionists (who, after all, are influenced by their culture and context, too)? How does researcher positionality matter? Such critical inquiry will enrich the field by shedding light on key components of attachment processes within contexts that have been historically neglected.

We note that this paper reflects our own current thinking and ongoing conversations with Black youth development scholars. There are undoubtedly other researchers, both within the field of attachment and outside of it, who will disagree or have additional views about these complex issues. Thus, this paper is intended to serve as a starting point for future work; we look forward to further conversations and research, with the expectation that our own understanding will continue to grow and change.

In sum, although theoretical models of Black youth development and attachment come from different starting places (the contextual vs. the interpersonal), they share a common goal: to understand and promote healthy child development via the power of relationships. Given their multiple points of overlap, we believe there is considerable promise for mutual enrichment and cross-fertilization. What is most clear is that collaborative research is needed in order to evaluate which aspects of attachment theory, research, and practice hold or need to change, and exactly how they need to change to best understand and support Black children’s healthy development in context. To echo Ainsworth (Citation1967) in the introduction to Infancy in Uganda, “We are here concerned with nothing less than the nature of love.” Bringing together perspectives from attachment and Black youth development may be a particularly potent means of working toward anti-racist perspectives – by using the science of love to advocate for programs and policies that better support Black children and families.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the authors who contributed to the 2021 Special Issue of Attachment & Human Development, “Attachment Perspectives on Race, Prejudice, and Anti-Racism.” The reflections contained herein are the direct result of reading their papers and engaging in fruitful dialogue during the review process and at the Society for Research in Child Development 2021 Biennial Meeting. We also thank Amanda Trujillo for her help preparing this paper, as well as José Causadias, Angel Dunbar, Roger Kobak, and Phil Shaver for their valuable feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1967). Infancy in Uganda: Infant care and the growth of love. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1969). Maternal sensitivity scales [Unpublished manuscript]. John Hopkins University.

- Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1989). Attachments beyond infancy. American Psychologist, 44(4), 709–716. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.44.4.709

- Ainsworth, M. D. S., Bell, S. M., & Stayton, D. J. (1974). Infant–mother attachment and social development: 'Socialisation' as a product of reciprocal responsiveness to signals. In M. P. M. Richards (Ed.), The integration of a child into a social world (pp. 99–135). Cambridge University Press.

- Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the Strange Situation. Erlbaum.

- Ainsworth, M. D. S., & Marvin, R. S. (1995). On the shaping of attachment theory and research. In E. Waters, B. E. Vaughn, G. Posada, & K. Kondo-Ikemura (Eds.), Caregiving, cultural, and cognitive perspectives on secure-base behavior and working models. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 60(2–3), 3–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5834.1995.tb00200.x

- Allen, J. P., & Tan, J. S. (2016). The multiple facets of attachment in adolescence. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (3rd ed., pp. 399–415). Guilford Press.

- Anderson, R. E., & Stevenson, H. C. (2019). RECASTing racial stress and trauma: Theorizing the healing potential of racial socialization in families. American Psychologist, 74(1), 63–75. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000392

- Atkins, R. (2014). Instruments measuring perceived racism/racial discrimination: Review and critique of factor analytic techniques. International Journal of Health Services, 44(4), 711–734. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2190/HS.44.4.c

- Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Kroonenberg, P. M. (2004). Differences in attachment security between African-American and white children: Ethnicity or socio-economic status? Infant Behavior & Development, 27(3), 417–433. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2004.02.002

- Barbarin, O. A. (2021). Racial disparities in the US child protection system: Etiology and solutions. International Journal on Child Maltreatment, 3 (4), 449–466. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s42448-020-00063-5

- Barbarin, O. A., Murry, V. M., Tolan, P., & Graham, S. (2016). Development of boys and young men of color: Implications of developmental science for My Brother’s Keeper Initiative (Social Policy Report). Society for Research and Child Development, 29(3), 1–31. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2379-3988.2016.tb00084.x

- Barbarin, O. A., Tolan, P. H., Gaylord-Harden, N., & Murry, V. (2020). Promoting social justice for African-American boys and young men through research and intervention: A challenge for developmental science. Applied Developmental Science, 24(3), 196–207. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2019.1702880

- Beier, J., Gross, J., Brett, B., Stern, J., Martin, D. R., & Cassidy, J. (2019). Helping, sharing, and comforting in young children: Links to individual differences in attachment. Child Development, 90(2), e273–e289. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13100

- Bell, D. (1995). Who’s afraid of critical race theory? University of Illinois Law Review, 1995(4), 893–910.

- Belsky, J., & Isabella, R. (1988). Maternal, infant, and social-contextual determinants of attachment security. In J. Belsky & T. Nezworski (Eds.), Clinical implications of attachment (pp. 41–94). Erlbaum.

- Belsky, J. (2005). Attachment theory and research in ecological perspective. In K. E. Grossmann, K. Grossmann, & E. Waters (Eds.), Attachment from infancy to adulthood: The major longitudinal studies (pp. 71–97). Guilford Press.

- Belsky, J., & Jaffee, S. (2006). The multiple determinants of parenting. In D. Cicchetti & D. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Vol. 3. Risk, disorder, and adaptation (2nd ed., pp. 38–85). Wiley.

- Billingsley, J. T., Rivens, A. J., & Hurd, N. M. (2020). Familial interdependence, socioeconomic disadvantage, and the formation of familial mentoring relationships within black families. Journal of Adolescent Research, 074355842097912. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558420979127

- Boag, E. M., & Carnelley, K. B. (2012). Self-reported discrimination and discriminatory behavior: The role of attachment security. British Journal of Social Psychology, 51(2), 393–403. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.2011.02065.x

- Boag, E. M., & Carnelley, K. B. (2016). Attachment and prejudice: The mediating role of empathy. The British Journal of Social Psychology, 55(2), 337–356. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12132

- Bonnett, A. (2005). Anti-racism. Routledge.

- Bouza, J., Camacho-Thompson, D. E., Carlo, G., Franco, X., Coll, C. G., Halgunseth, L. C., Marks, A., Stein, G. L., Suarez-Orozco, C., & White, R. M. B. (2018). The science is clear: Separating families has long-term damaging psychological and health consequences for children, families, and communities. Society for Research in Child Development. Policy Briefs. http://www.srcd.org/sites/default/files/resources/FINAL_The%20Science%20is%20Clear.pdf

- Bowlby, J. (1944). Forty-four juvenile thieves: Their characters and home life. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 25, 19–52, 107–127.

- Bowlby, J. (1969/1982). Attachment and loss. Vol 1: Attachment. Basic Books.

- Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss. Vol 2: Separation and anger. Basic Books.

- Bowlby, J. (1980). Attachment and loss. Vol 3: Loss, sadness and depression. Basic Books.

- Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base. Basic Books.

- Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 46–76). Guilford Press.

- Bretherton, I., & Munholland, K. A. (2008). Internal working models in attachment relationships: Elaborating a central construct in attachment theory. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed., pp. 102–127). Guilford Press.

- Bretherton, I. (2010). Fathers in attachment theory and research: A review. Early Child Development and Care, 180(1–2), 9–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430903414661

- Bridgman, A. (2017). Supporting parents: Using research to inform policy and best practice [Social Policy Report Brief]. Society for Research in Child Development, 30 (5), 1–2. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED581643.pdf

- Brody, G. H., Chen, Y. F., Murry, V. M., Ge, X., Simons, R. L., Gibbons, F. X., Gerrard, M., & Cutrona, C. E. (2006). Perceived discrimination and the adjustment of African American youths: A five-year longitudinal analysis with contextual moderation effects. Child Development, 77(5), 1170–1189. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00927.x

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1974). Developmental research, public policy, and the ecology of childhood. Child Development, 45(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/1127743

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The ecology of developmental processes. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (6th ed., pp. 795–825). Wiley.

- Brumariu, L. E., Madigan, S., Giuseppone, K. R., Abtahi, M. M., & Kerns, K. A. (2018). The Security Scale as a measure of attachment: Meta-analytic evidence of validity. Attachment & Human Development, 20(6), 600–625. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2018.1433217

- Calkins, S. D., & Leerkes, E. M. (2011). Early attachment processes and the development of emotional self-regulation. In K. D. Vohs & R. F. Baumeister (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 355–373). Guilford Press.

- Carnelly, K. B., & Boag, E. M. (2019). Attachment and prejudice. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 110–114. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.04.003

- Cassidy, J. (1994). Emotion regulation: Influences of attachment relationships. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59(2–3), 228–249. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5834.1994.tb01287.x

- Cassidy, J., Ehrlich, K. B., & Sherman, L. J. (2013). Child-parent attachment and response to threat: A move from the level of representation. In M. Mikulincer & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Nature and development of social connections: From brain to group (pp. 125–144). American Psychological Association.

- Cassidy, J. (2021). In the service of protection from threat: Attachment and internal working models. In R. A. Thompson, J. Simpson, & L. J. Berlin (Eds.), Attachment: The fundamental questions,103–109. Guilford Press.

- Cassidy, J., Poehlmann, J., & Shaver, P. R. An attachment perspective on incarcerated parents and their children. (2010). Attachment & Human Development, 12(4), 285–288. [Special Issue]. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730903417110

- Causadias, J. M., Morris, K. S., Cárcamo, R. A., Neville, H. A., Nóblega, M., Salinas-Quiroz, F., & Silva, J. R. (this issue). Attachment research and anti-racism: Learning from Black and Brown scholars. Attachment & Human Development. [Special Issue]. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2021.1976936

- Clark, R., Anderson, N. B., Clark, V. R., & Williams, D. R. (1999). Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist, 54(10), 805–816. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.54.10.805

- Coan, J. A. (2018, June 15). Opinion: The Trump administration is committing violence against children. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/the-trump-administration-is-committing-violence-against-children/2018/06/15/9be06440-70c0-11e8-bd50-b80389a4e569_story.html

- Coard, S. I., & Sellers, R. M. (2005). African American families as a context for racial socialization. In V. C. McLoyd, N. E. Hill, & K. A. Dodge (Eds.), African American family life: Ecological and cultural diversity (pp. 264–284). Guilford Press.