ABSTRACT

Scholarly discussion suggests prevalent, overconfident use of attachment classifications in child protection (CP) investigations but no systematic research has examined actual prevalence, the methods used to derive such classifications, or their interpretations. We aimed to cover this gap using survey data from a nationally representative sample of Swedish CP workers (N = 191). Three key findings emerged. First, the vast majority formed an opinion about young children’s attachment quality in all or most investigations. Second, most did not employ systematic assessments, and none employed well-validated attachment methods. Third, there was overconfidence in the perceived implications of attachment classifications. For example, many believed that insecure attachment is a valid indicator of insufficient care. Our findings illustrate a wide researcher-practitioner gap. This gap is presumably due to inherent difficulties translating group-based research to the level of the individual, poor dissemination of attachment theory and research, and infrastructural pressures adversely influencing the quality of CP investigations.

Child protection (CP) workers are not only required to make incredibly difficult decisions; they face numerous additional challenges such as high workload, funding cuts, and demands to anchor risk-assessments in scientific evidence. These factors have contributed to a need for developmental theories with high scientific rigor, and there are indications that CP workers increasingly perceive attachment theory – including its classifications of attachment quality – as meeting this need (e.g. White et al., Citation2019). This development has been encouraged by some scholars, who advocate the use of attachment classifications in CP as a means to gain insights into caregiving quality and future child development (e.g. Crittenden & Baim, Citation2017; Spieker et al., Citation2021). Other scholars have, however, raised warning flags against such use, due to psychometric limitations of the measures, and worries that overconfident translation of group-level research to individual children may undermine children’s best interests (e.g. Forslund et al., Citation2021a; Granqvist, Citation2016; van IJzendoorn et al., Citation2018a, Citation2018b). However, these concerns may well be exaggerated; systematic research addressing CP workers’ actual use of attachment classifications, and their views on the implications of such classifications, is remarkably scant. This study constitutes an attempt to cover this notable knowledge gap.

Child protection in context: conditions pressing attachment theory into service

Child protection (CP) workers face an incredibly difficult task, with high stakes for all parties concerned. On the one end, failure to recommend precautionary action (such as out-of-home care) for children at risk may result in serious harm, or even death, of the child. On the other end, child-caregiver separations are associated with developmental risks in themselves (e.g. Jones-Mason et al., Citation2021). These risks are especially pronounced if separations are followed by prolonged caregiving instability (van IJzendoorn et al., Citation2020), which is common, even preponderant, in many countries (e.g. Konijn et al., Citation2018; Sallnäs et al., Citation2004; Wulczyn et al., Citation2003). Thus, whether a child is placed in out-of-home care, or allowed to remain with the caregivers, ill-advised or poorly substantiated decision-making may have significant negative consequences.

Additionally, many Western countries have recently seen radical changes in child welfare. Changes include increased staff workload and bureaucratic demands, a rising number of investigations, limited funding, and heightened complexity of investigated families (e.g. Gibson et al., Citation2018; Lavee & Strier, Citation2018). Service managers also grapple with high turnover rates, and poor resources for training of unexperienced employees expected to replace experienced dropouts (e.g. Griffiths et al., Citation2017; Karsten, Citation2018; Park & Shaw, Citation2013). It has been suggested that these conditions contribute to a decreased focus on support to families, and an emphasis on assessments of risk and protection (e.g. Bilson & Munro, Citation2019).

Alongside contextual conditions, CP services in most Western countries have increasingly been required to anchor risk assessments in scientific evidence, both for legal (i.e. legal certainty; e.g. Lundström & Sallnäs, Citation2019) and bureaucratic reasons (e.g. accountability; Gibson et al., Citation2018). This has created a demand for developmental theories with high scientific rigor, and conceptualization of child risks and benefits in terms of these theories. Additionally, most Western countries have come to use the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC; UN General Assembly, Citation1989), with its principle of “the best interest of the child”, as a legal framework for CP decision-making (Falch-Eriksen & Backe-Hansen, Citation2018). This development has undoubtedly been important in drawing increased attention to children’s rights and needs. Nevertheless, the principle’s vague formulation has contributed to a need for more incisive interpretation in terms of empirically validated developmental theories (Mnookin, Citation1975), and an emphasis on child-caregiver relationships (Skivenes & Sørsdal, Citation2018). For reasons described below, attachment theory and its associated classification systems may have seemed to meet these needs.

Attachment theory, child protection, and words of caution regarding use of attachment classifications

Since Bowlby formulated attachment theory, attachment scholars have emphasized the general importance of child-caregiver interactions and relationships for child development. Bowlby (Citation1969/1982) understood attachment in terms of an evolved motivational system, with infants universally forming strong affectional bonds – attachments – to their caregivers (i.e. attachment figures). Attached children protest separations and seek to maintain proximity to their attachment figures by means of attachment behaviors (any behavior functioning to increase the likelihood of physical proximity; e.g. crying, clinging). This is particularly evident in situations that give clues to danger, where children are motivated to orient themselves towards attachment figures as sources of comfort and protection (i.e. safe havens). However, children also monitor their attachment figures’ whereabouts in the absence of threats, using them as secure bases for exploration.

While these normative (species-typical) aspects of attachment are central to attachment theory, scholars have also paid considerable attention to how variations in the quality of children’s attachment relationships (i.e. secure, insecure, disorganized) may moderate the output of the attachment system. Secure child attachment is characterized by expectations that an attachment figure will be available as a safe haven and secure base, as manifest in well-coordinated integration between the behavioral systems for attachment and exploration (Ainsworth et al., Citation1978), and flexibility of attention vis-à-vis attachment-related information (Main, Citation1990). Insecure/avoidant child attachment is characterized by defensive exploration at the expense of attachment-related feelings and needs, and insecure/resistant child attachment by negative engagement in attachment needs at the expense of exploration (Ainsworth et al., Citation1978). Lastly, children with disorganized/disoriented attachment show a momentary attentional and behavioral breakdown, as manifested by indices of conflicted, confused, or fearful behaviors in the presence of the caregiver (Main & Solomon, Citation1990).

Attachment research has also focused on how individual variations in attachment quality relate to caregiving and child developmental outcomes. Decades of research have demonstrated that such variations are predicted most consistently by caregivers’ sensitivity to their children’s signals (e.g. De Wolff & van IJzendoorn, Citation1997) and ability to mentalize their children’s behaviors (e.g. Zeegers et al., Citation2017). Moreover, insecure or disorganized child attachment have been linked to an array of negative developmental outcomes, including higher levels of internalizing (Groh et al., Citation2012) and externalizing (Fearon et al., Citation2010) behavior problems, and lower social competence (e.g. Groh et al., Citation2014). By offering this scientific account of how variations in child attachment quality relate to caregiving behaviors and child development, attachment theory may have seemed to promise a valid operationalization of the best-interest principle, and an empirical basis for considerations of caregiving and child developmental risks.

In the wake of attachment theory’s scientific success, simplified (i.e. allodoxic; Duschinsky, Citation2020) accounts of the theory have become widespread. These accounts typically employ deterministic descriptions of the aforementioned links among caregiving, attachment quality, and developmental outcomes. The empirical picture is, however, more complex. First, meta-analytic links between the pertinent constructs are not strong, but modest to moderate in size (e.g. Fearon et al., Citation2010; Groh et al., Citation2012, Citation2014; Verhage et al., Citation2016). A given child’s attachment quality can therefore be viewed neither as a mirror image of caregiver sensitivity, nor as a divination regarding child development. Crucially, and of particular importance to CP investigations, disorganized attachment cannot be viewed as a valid indicator of child maltreatment (Granqvist et al., Citation2017). Other factors, including aggregated socioeconomic strains, also increase the risk for disorganized attachment (Cyr et al., Citation2010).

Second, caregiver sensitivity and child attachment quality are both malleable in response to life events and changes in family support (Pinquart et al., Citation2013), and evidence-based attachment interventions facilitate caregiver sensitivity and child attachment security (Steele & Steele, Citation2017). In other words, low caregiver sensitivity per se is not a valid indicator of a parent’s inability to provide good-enough caregiving, let alone a sufficient reason for placing a child out-of-home.

Third, variations in attachment quality do not override the foundational importance of species-typical attachment processes (Granqvist, Citation2021). For example, disrupted attachments, like prolonged, involuntary and/or repeated separations from attachment figures, are linked to highly adverse developmental outcomes, especially when occurring in early childhood (e.g. Jones-Mason et al., Citation2021; van IJzendoorn et al., Citation2020). In fact, any adverse group-level effects of attachment insecurity are minor in comparison. Additionally, although insecure attachment is, on the whole, not optimal in the long term, most insecurely attached children are likely to benefit from their caregivers in various ways, if the relationships remain continuous and the child is kept safe and provided with stimulation (e.g. Forslund et al., Citation2021a).

Finally, assessing attachment quality is a complicated matter. There is currently an abundance of measures, and since most measures use similar terminology, they may mislead assessors to hasty conclusions about conceptual identity. Yet, many of the measures in circulation among practitioners have not been sufficiently validated, and the degree to which the pertinent classifications relate to the wider field of research on attachment quality is thus highly uncertain. One such example is the Attachment Styles Interview (ASI; Bifulco et al., Citation2008). Although insufficiently validated, as is acknowledged by its developers, the ASI has been used diagnostically in many Swedish municipalities, for instance to determine suitability to provide foster care (for a discussion, see Granqvist, Citation2016). In fact, even the usefulness of gold-standard assessments of attachment quality has been questioned in CP settings. More specifically, scholars have pointed out that these instruments, though validated for group-level research, have limited psychometric properties for use with individuals (e.g. Granqvist, Citation2016; van IJzendoorn et al., Citation2018a, Citation2018b), and should thus be avoided in high-stakes decision-making (e.g. Forslund et al., Citation2021a, Citation2021b).

Are attachment classifications invoked in child protection assessments? Missing pieces and the present study

Against the aforementioned caveats, scholars have expressed concerns regarding a seemingly increased use of attachment classifications in CP contexts (e.g. Duschinsky, Citation2020; Forslund et al., Citation2021a; Granqvist et al., Citation2017). To illustrate, social workers in the U.K. have been offered large-scale workshops to identify disorganized attachment in naturalistic settings as a proxy for child maltreatment (e.g. Shemmings & Shemmings, Citation2011). Moreover, at least a fourth of all municipalities in Sweden have used the Attachment Style Interview (Bifulco et al., Citation2008) in CP or child custody decision-making (Granqvist, Citation2016). Studies from Norway (Melinder et al., Citation2021), Denmark (Søberg Bjerre et al., Citation2021), and the UK (Beckwith, Citation2021; White et al., Citation2019) similarly indicate that attachment-quality considerations have become a priority among many CP workers. However, despite these indications, we do not know how widely involved attachment classifications are in CP investigations, nor which measures are used. Neither do we know to what aims CP workers use attachment classifications, nor how the classifications are interpreted. This is because there is no published systematic research on these matters. The present, descriptive study was therefore designed to address the prevalence of the use of attachment classifications in a nationally representative sample of CP workers in Sweden, one of the countries that have figured in recent discussions. We also asked which procedures are used to derive these classifications in CP investigations. Finally, we asked which opinions CP workers have regarding the purpose and applicability of attachment classifications in their investigations.

Method

Procedure

The survey

An online survey program (Survey&Report) was used to construct a digital 42-item survey that included six sections: (1) A control question to ascertain that the respondents had current experience of CP investigations; (2) Background questions needed to analyze sample representativeness (e.g. educational level, investigative experience, and size, socioeconomic risk status and geographical location of respondents’ operating municipalities); (3) Questions about how often the respondents form an opinion about attachment-quality in CP investigations; (4) Questions about the procedures used; (5) Questions about respondents’ opinions regarding the purpose and applicability of attachment classifications in CP investigations; and (6) Questions about formal training in attachment measures.

The questions in sections (1)-(3) were answered by all respondents, whereas section (4) and (6) only regarded respondents who stated that they form an opinion about attachment quality in their work. Section (5) consisted of two sets of questions. The first pertained to the perceived purpose of forming an opinion about attachment quality, and consequently regarded only respondents who stated they formed such opinions. The second set involved general questions pertaining to respondents’ understanding of attachment classifications, and was answered by all respondents. Thus, the exact number of questions answered by each respondent depended on their individual routes through the survey.

To ascertain valid responses, the survey included clear definitions of key concepts. Also, we consistently used the term “attachment patterns” rather than “attachment quality”, because pilot reviewers deemed the former concept more established among social workers (see next heading). Similarly, the term “assess attachment quality” was deemed likely to be perceived as pertaining exclusively to systematic, standardized assessments. Since we also wanted to examine the use of nonsystematic and unstandardized procedures, we used the wider concept of “forming an opinion about attachment patterns” in all questions that did not strictly regard use of standardized assessment instruments. For consistency of terminology, we use the term attachment quality in the remainder of this article.

To minimize internal data-loss, the survey mainly included compulsory, forced-choice questions. With regard to the prevalence of attachment-quality considerations, respondents were asked to state on a five-point scale how often (in all, most of, half of, a small part of, or none of the CP investigations) they formed an opinion about attachment quality in children (<1 year of age, 1–12 years old, 13–18 years old) and in parents. Questions about assessment procedures and the perceived purpose of forming an opinion about attachment quality were put in statement form (e.g. “I use a standardized assessment instrument … ”), with four response options (e.g. never, seldom, often, always). Questions related to respondents’ understanding of attachment classifications were similarly put in statement form (e.g. “Insecure child attachment is a sign of insufficient parental caregiving”), but with a dichotomous response option (yes/no). Finally, the survey included seven open-ended questions. Three of these were compulsory, and required specification of a previous answer (e.g. the labels of instruments used for assessing attachment quality), while four were optional and tapped potential mismatches between survey formulations and respondents’ practice.

Pilot test

Prior to the study, two reference groups comprising three persons each reviewed the survey. The first group had extensive experience from CP work, and provided feedback on survey content (e.g. phrasing of questions, appropriateness of questions vis-à-vis current investigative practice). The second group lacked such experience, but provided feedback on survey user-friendliness. Based on this feedback, we clarified parts of the instructions and rephrased a number of questions.

Recruitment

Recruitment was conducted in March-April 2021. Random sampling was not possible, since there was no available national or municipal data on the size of the population of interest, and no register of potential respondents. Thus, we employed a combined exhaustive and voluntary-response sampling strategy. Managers for all child and family social service units in Sweden were contacted per e-mail with information about the study, and asked to distribute the information to their staff. A reminder was sent out to the unit managers one week after the initial contact. The information included a description of the study, a link to the survey, and information about anonymity, the voluntary nature of participation, and the right to withdraw without negative consequences. The study information emphasized the need for further knowledge about CP workers perception and use of attachment theory and assessments. More specifically, it was stated that the study aimed to examine whether and, if so, how CP professionals’ reason about attachment-related matters and assessments in their investigations. To maximize heterogeneity among respondents, the study information also emphasized that all answers were equally important, and that previous experience of attachment-related questions and assessments was irrelevant for inclusion. Participating units were also invited to receive information about the results after study completion, through a written report sent to all unit managers. Staff members were eligible for participation if they had conducted at least one CP investigation during 2016–2021, and it was explicitly stated that all CP workers meeting this criterion could participate, again regardless of their experience of attachment theory or -assessments. To ascertain anonymity, only a minimum of personal information (e.g. operating municipality, educational background) was collected. Information concerning informed consent was repeated on the first page of the survey, and it was not possible to complete the survey without leaving informed consent. The study used fully anonymized data and formal ethical approval from the Swedish ethics review authority was therefore not needed. Unit managers forwarded the study invitation without us knowing which CP workers were reached by the invitation. Participating CP workers then used a hyperlink to reach and respond to the questionnaire, which did not include any questions that could potentially identify the respondents. Indeed, it was explicitly stated in the letter of invitation that neither we nor anybody else would know who had responded to the questionnaire. Thus, participation was completely anonymous.

Respondents

In total, 191 CP workers responded to the survey, from 19 of Sweden’s 21 regions, and 94 of 290 municipalities. The respondents had conducted CP investigations for an average of 6.2 years (SD = 5.4), and almost all (97%) had conducted their last investigation during the 12 months prior to the study. The most common educational background was a bachelor’s degree in social work (88%).

The sample’s national representativeness was analyzed by comparing the sample with (i) national estimates regarding educational level and investigative experience of CP workers, and (ii) the national distribution of municipalities with regard to population size, (iii) socioeconomic risk status, and (iv) geographical location (the Swedish Central Bureau of Statistics, Citationn.d.; the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare, Citation2021). The sample displayed good national representativeness regarding the size, risk status, and geographical location of respondents’ operating municipalities, and respondents’ investigative experience.

Statistical analyses

The data was downloaded from Survey&Report and analyzed in JASP statistical analysis software package (Version 0.14.1). Due to the exploratory nature of our research questions, only descriptive data (frequencies and proportions) were calculated. Responses to open-ended questions were grouped thematically and translated into frequency data. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Results

Prevalence of forming an opinion about attachment quality

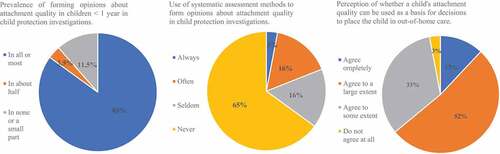

Results pertaining to how often the respondents form an opinion about attachment quality are displayed in . A vast majority (85%) stated they form such opinions in all or in most of their investigations involving children <1 year of age. The corresponding proportions for investigations involving children aged 1–12 years and 13–18 years old were 77% and 57%, respectively. Across all child age spans, very few stated they never form opinions about child attachment quality.

Table 1. The proportion of the respondents who form an opinion about attachment quality in child protection investigations.

Forming opinions about parents’ attachment representations was less common. A large minority (43%) stated they did so in a small part of their investigations, whereas only about a quarter formed such opinions in all or in most of their cases.

Procedures for assessing attachment quality

The procedures for forming opinions about child attachment quality are shown in . The most common procedures were interviews with the child (if verbal), alone or with parents; gathering of information from previous CP investigations or other professionals; and observing the child’s interaction with a parent or the investigative CP worker. Overall, 88–100% of the respondents stated they always or often use any of these procedures. The corresponding estimate for systematic assessment instruments was 19%, and a clear majority (65%) stated they never use systematic instruments to inform their opinions about child attachment quality.

Table 2. The procedures used by the respondents to form an opinion about child attachment quality in child protection investigations.

The minority of respondents who stated they use assessment instruments (always, often, or seldom) were asked to name these. The most common responses were Signs of Safety (a risk-assessment tool; 20 respondents), and Barns Behov i Centrum (BBiC; Swedish casework module; 8 respondents). Instruments developed for assessing attachment quality were rare: four respondents named the Attachment Style Interview (ASI), and one the Vulnerable Attachment Style Questionnaire (VASQ); both developed for use with adults.

With regard to forming opinions about parental attachment, a vast majority (92%) stated they never use systematic assessment instruments. Among the few who stated they did, ASI was the most commonly mentioned instrument (6 respondents).

Respondents’ training in attachment measures

A small minority (14%) stated they had completed formal training in a standardized measure developed for assessing attachment quality. The most frequently mentioned measure was ASI (6 respondents). Other measures were HOME (2 respondents); Circle of Security (2 respondents); Marte Meo (1 respondent); Kälvesten (a Swedish interview-based method used to examine suitability to become a family-home caregiver); 1 respondent); and the International Child Development Programme (1 respondent). The remaining respondents referred to brief courses or clinical supervision. Of the measures/methods mentioned, only ASI is actually a standardized measure for assessing attachment quality.

Opinions regarding the purpose and applicability of attachment classifications

Results pertaining to the perceived purpose of forming an opinion about attachment quality are shown in . A very large proportion (79–94%) agreed completely or to a large extent that child attachment quality provides information about the following: the quality of caregiving the child has received thus far; the parents’ current caregiving capacity; the child’s future development if the current situation remains unaltered; the child’s current psychological well-being; and information that can inform supportive interventions. A smaller majority (64–66%) agreed completely or to a large extent that child attachment quality can inform decisions about placing the child in out-of-home care, or about allowing the child to remain in parental care.

Table 3. The respondents’ perceptions of the purpose of forming an opinion about child attachment quality.

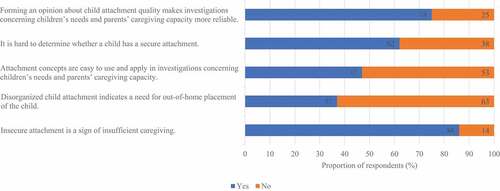

Regarding general opinions about attachment classifications (), a very large majority agreed that insecure child attachment is a sign of insufficient parental caregiving, and a substantial minority agreed that disorganized child attachment indicates a need for out-of-home placement. A large majority also agreed that forming an opinion about attachment quality makes CP investigations more reliable and valid. At the same time, a somewhat smaller majority agreed that it is hard to determine if a child has a secure attachment, and slightly less than half found attachment concepts easy to use in their practical work.

To facilitate dissemination, provides pie charts illustrating our key findings.

Figure 2. Key results concerning prevalence of forming opinions about attachment quality, use of systematic assessment methods, and perceived use of information about attachment quality, in CP investigations.

Discussion

The present study, based on a nationally representative sample of Swedish child protection (CP) workers, was motivated by concerns regarding seemingly prevalent, overconfident use of attachment classifications in CP investigations (e.g. Forslund et al., Citation2021a; Granqvist et al., Citation2017). In line with these concerns, the CP workers studied did indeed very often form opinions about children’s attachment quality, without using standardized or validated methods, and many agreed with overconfident statements about the implications of attachment classifications. These findings attest to a wide researcher-practitioner gap (White et al., Citation2019). They also attest to premature and incautious translation of attachment theory and research into practice, which has influenced many types of practitioners beyond CP workers (van IJzendoorn & Bakermans-Kranenburg, Citation2021). We discuss our key findings, address group-to-individual inference problems, note methodological considerations, and reiterate the real pressures making high-quality CP investigations difficult to accomplish.

Prevalence of forming opinions about attachment quality

Almost all respondents formed opinions about children’s attachment quality as part of their CP investigations, especially at younger child ages. While forming an opinion about does not necessarily imply assessing, these findings suggest that attachment classifications have become widely used among CP workers in Sweden, similar to the situation in other countries (Department for Education, Citation2018; Melinder et al., Citation2021; Søberg Bjerre et al., Citation2021). It is somewhat puzzling that forming opinions about attachment quality was descriptively most prevalent for children below 12 months of age. Attachment formation is certainly a milestone during 6–12 months of infant age (Bowlby, Citation1969/1982), but assessments of attachment quality are not validated until children’s second year of life onwards. It is also surprising that many of the CP workers formed opinions about caregivers’ attachment quality when evaluating caregiving competence. Notably, roughly forty percent of all adults in the general population are insecure with regard to attachment (e.g. Verhage et al., Citation2016), and most insecure adults provide good-enough caregiving. The high prevalence and misguided use of forming opinions about attachment quality may in part reflect the “winners’ curse” (van IJzendoorn & Bakermans-Kranenburg, Citation2021). Indeed, early, small attachment studies with unrepresentatively large effect sizes have yielded notable interest among many types of practitioners, and resulted in some premature and oversimplified applications (i.e. prior to thorough replications, downplaying complexity).

Procedures for forming opinions about attachment quality

The use of systematic assessment instruments was the least common procedure utilized, and the vast majority of respondents never or rarely used such instruments when forming an opinion about attachment quality. Here, it should be underscored that attachment quality is relationship-specific for young children, and it is therefore paramount that child-caregiver interactions form the basis for evaluating attachment quality. Despite this, many of the respondents formed opinions about children’s attachment quality based on other sources, such as previous CP investigations or their own conversations or interactions with children without the caregiver present.

Valid assignment of attachment quality also requires standardized procedures, training, and certification for coding. Nonetheless, the vast majority formed their opinions absent standardized procedures and pertinent training and certification. Further, the small minority who occasionally used systematic instruments almost exclusively mentioned broad batteries not developed to assess attachment quality. In fact, very few mentioned designated attachment instruments, and none used properly validated ones. Notably, a plethora of attachment instruments is currently in circulation, many with poor or unknown psychometric properties. It is disheartening that the few attachment instruments that were mentioned (i.e. the ASI and VASQ) are far from sufficiently validated. In fact, the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare (Citation2019) has emphasized that the validity of the ASI is unknown. At the same time, most Swedish CP workers are required to use a certain broad case module that recommends looking for signs of insecure attachment, illustrated with a fleeting example of how it might be expressed (the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare, Citation2018a, October 20, Citation2018b). Such guidance may misleadingly empower practitioners to form opinions about attachment quality absent standardized methods and pertinent training. Participants’ naming of other measures beyond designated attachment measures, including some measures that do not target attachment quality at all, presumably illustrates the emphasis placed on child-parent relationships in operationalizations of the best-interest-of-the-child standard, without specifying what aspects are most important or how they should be assessed. It also illustrates that attachment quality may indeed be conflated with relationship or caregiving quality (for a discussion, see Forslund et al., Citation2021a).

The perceived purpose and applicability of attachment classifications

The vast majority of our respondents regarded child attachment quality as useful for informing supportive interventions in the family, and this purpose was the one with which most respondents (descriptively) agreed. This result is comforting, as it is in line with research on evidence-based attachment interventions and recent recommendations from the attachment field (Forslund et al., Citation2021a). Yet, the majority of our respondents also regarded child attachment classifications a useful proxy of caregiving competence, an index of the child’s current wellbeing, and a strong predictor of child development. Further, a small majority also found attachment classifications useful for decision-making about out-of-home placements, and a substantial minority viewed out-of-home care as reasonable for children classified as having disorganized attachment. These findings corroborate concerns regarding widespread, overconfident beliefs in the implications of attachment classifications (Forslund et al., Citation2021a). In contrast to the supposition that insecure child attachment unequivocally signals “insufficient caregiving”, attachment quality is not a mirror image of caregiver sensitivity, and most children with insecure attachments benefit from their caregivers in many ways. Moreover, theory and research suggest that children are differentially susceptible to the rearing environment; for example, attachment quality may result from the interaction between genetic endowment and caregiving-based influences (Bakermans‐Kranenburg & van IJzendoorn, Citation2007). There are also several caregiving-based pathways to disorganized attachment, many of which do not involve maltreatment (e.g. Granqvist et al., Citation2017). Further, children can exhibit disorganized behaviour without a disorganizing relational history, due to neurological vulnerability or overstress (Padrón et al., Citation2014). Finally, the meta-analytical effect sizes between child attachment quality and development are modest (Groh et al., Citation2017). In sum, a child’s attachment quality is not sufficient for retrodicting caregiving or predicting development with any reasonable degree of certainty.

A majority of our respondents found it difficult to form an opinion about attachment quality, and half of the respondents expressed difficulties using attachment concepts in their work. These findings are somewhat reassuring and in line with research from other countries (Robertson & Broadhurst, Citation2019). However, a substantial minority did not find it difficult to form an opinion about attachment quality. This is, in our view, more concerning. A little knowledge can indeed be a dangerous thing (e.g. Pope, Citation1709/2017), especially if it misleads CP workers into sensing they have more expertise on attachment than in fact they do.

Attachment classifications and inferences from groups to individuals

To summarize, we have seen in this study that Swedish CP workers regularly form opinions about children’s attachment quality, in the absence of validated instruments, and that many make overconfident appeals about which inferences can be drawn from attachment classifications. These findings are a serious concern, since they suggest that misinformed perceptions about attachment quality may mislead CP investigations (cf. van IJzendoorn & Bakermans-Kranenburg, Citation2021).

We believe this unfortunate situation may reflect a fundamental tension between what scientists typically do, and what CP workers and courts are required to do (e.g. Neal et al., Citation2019). While science generalizes from individual cases to general principles, a central aspect of CP concerns particularization from general principles to individual cases (cf. nomothetic vs. idiographic science; Windelband, Citation1904). Specifically, CP workers and courts must decide whether and how knowledge from group-based research can be helpful for recommendations and decision-making regarding specific individuals, termed group (G) to (2) individual (i) inference (G2i; Faigman et al., Citation2014). A predicament in this process is that any individual may or may not constitute an example of a general group-based principle, and there is thus a risk for invalid inferences. Two things are especially important in managing this risk.

First, the risk is reduced if the assessment instruments used are able to reliably identify a high proportion of the cases they are designed to identify (sensitivity), and not erroneously misidentify others as such (specificity). However, and as mentioned above, attachment scholars have repeatedly emphasized that all current attachment instruments – while sometimes impressive for group-based research – have insufficient sensitivity and specificity to allow firm conclusions regarding individual children’s “true” attachment quality (e.g. Granqvist, Citation2016; van IJzendoorn et al., Citation2018a, Citation2018b). Second, the risk is also reduced (but not eliminated) if the effect size of a pertinent group-level association is very large. As also noted above, the effect sizes among caregiving, child attachment quality, and child development are, however, only modest to moderate in size.

Many attachment scholars have therefore cautioned against the use of attachment classifications in high-stakes decision-making, such as CP (Forslund et al., Citation2021a; Granqvist et al., Citation2017; van IJzendoorn et al., Citation2018a, Citation2018b). These scholars have argued that attachment assessments with individuals should primarily be used to guide supportive interventions (Forslund et al., Citation2021a), and that attachment theory as a whole is most useful as a general “framework” for decision-making and policy work rather than for “diagnostic” assessments (Forslund et al., Citation2021b).

Crucially, most attachment scholars who argue that validated attachment assessments may enhance CP investigations also emphasize notably stringent conditions for their use (see Forslund et al., Citation2021a). Certainly, both strands of scholars agree that assessing/forming opinions about attachment quality absent training in well-validated measures and a thorough understanding of the inferences that can (and cannot) be drawn from such assessments, can lead to erroneous perceptions that may harm children’s best interests. Finally, there is wide consensus in the field that attachment-normative considerations are much more central for CP work than considerations of children’s attachment classifications. In particular, it is key for CP work to give priority to three general principles: (1) children’s need for familiar, non-abusive and non-neglecting caregivers; (2) the value of continuity of good-enough care; and (3) the benefits of maintaining a network of (non-abusive and non-neglecting) attachment relationships (Forslund et al., Citation2021a).

Pressures on child protection and the use of scientific terminology

Our findings must be viewed in context. Not only do attachment scholars disagree among themselves about whether attachment classifications may inform CP considerations (see Forslund et al., Citation2021a); some scholars (e.g. Crittenden & Baim, Citation2017; Spieker et al., Citation2021) also advocate the use of their classification instruments in CP, despite the aforementioned criticism concerning the instruments’ psychometric properties (see van IJzendoorn et al., Citation2018a). Furthermore, attachment scholars have not contributed sufficiently to careful dissemination of research, including to the practitioners who put the theory to practice (Duschinsky, Citation2020; Goldberg, Citation2000). Such factors may also have fuelled some of the more optimistic ideas regarding the use of attachment classifications expressed by many respondents in this study.

As reviewed in the introduction, CP workers also face numerous challenges that may contribute to an interest in attachment classifications. These include increased demands on evidence-based assessments and recommendations, implying a spur to use scientific constructs with high credibility, so that recommendations are more likely to pass in court. In this context, the prestige and popularity of attachment theory and associated classifications may lead CP workers to dress their assessments of parent-child relationships in attachment attire, although the assessments may actually often regard much broader and less well-defined aspects of the relationship (White et al., Citation2019). Our finding that a majority of the CP workers form opinions about child attachment quality even at ages when many children have not yet developed a clear-cut attachment, could be understood from this perspective. The same goes for the finding that CP workers included broad measures not designed for assessment of attachment quality as attachment measures proper. Similarly, widespread “allodoxic” (Duschinsky, Citation2020) accounts of attachment theory may further fuel use of attachment classifications among CP workers. Such accounts are typically based on everyday connotations of terms used technically in attachment theory (e.g. sensitivity, security), and describe relations among parental caregiving, child attachment, and child development in deterministic and oversimplified manners. Nevertheless, their terminological overlap with attachment research may render the accounts an aura of empirical solidness, and obscure their limited fit with scientific reality. Our finding that many CP workers agreed with overconfident statements about the implications of attachment classifications suggests that such allodoxic accounts have influenced their understanding of attachment theory. This indicates a need for more training in attachment theory among Swedish CP workers, and more active and clear communication on behalf of Swedish attachment researchers.

Strengths and limitations

There are limitations to this study that present opportunities for future research. First and foremost, our results are descriptive and based on self-reports, using a brief questionnaire with forced choice questions. The response format may for instance have made the CP workers present a less nuanced view than they actually hold. Relatedly, most questions did not address the weight CP workers give to their opinions about individual children’s (and caregivers’) attachment quality. More specifically, a CP worker could agree completely with a question (e.g. that child attachment quality provides information about the quality of care hitherto received by the child) while believing it provides all information he or she needs, just a small part of it, or anything in between. Such important nuances were not captured by this study, and it is therefore somewhat unclear whether and how the findings translate to actual investigations, protocols, and recommendations. At the same time, the questions were carefully worded to emphasize the respondents’ perception and use of attachment theory and assessments in their own CP work with individual children and caregivers. Agreeing completely with certain questions (e.g. “attachment quality provides information that can be used as a basis for placing the child in out-of-home care”) clearly does imply giving substantial weight to information about attachment quality. Further, previous research from Sweden has suggested common references to children’s attachment quality in CP investigation protocols, without any information about assessment methods (Alexius & Hollander, Citation2014).

Second, practitioners who work more clearly based on attachment theory may have been more likely to participate, implying inflated references to attachment classifications. This seems unlikely, however, because very few respondents used or had training in standardized attachment methods. Moreover, we explicitly invited practitioners to participate whether or not they had experience of attachment-related questions and assessments. Notwithstanding, it is key to gain knowledge regarding the application of attachment theory from those CP workers who are actually putting the theory to use in their work.

Third, this study only included practitioners from Sweden, and our results do not necessarily generalize to other countries. At the same time, our findings are in line with findings from comparable countries (e.g. Melinder et al., Citation2021; Søberg Bjerre et al., Citation2021).

The study also had strengths. First, this is to the best of our knowledge the first systematic study to examine the use of attachment classifications among CP workers. Second, our study was based on a substantial and nationally representative sample of CP workers. Our findings raise important questions and suggest an urgent need for further research. We recommend attempts to replicate and extend our findings, particularly in other countries. Such research would not only do well to examine the extent to which our findings translate to actual CP assessments, and what weight is given to information about attachment quality, but also examine factors contributing to constructive vs. problematic uses of attachment classifications. Finally, future research should use methods that increase respondents’ opportunities to fully express their perceptions of the use of attachment theory and assessments in CP.

Conclusions

We have reported that the majority of a nationally representative sample of Swedish CP workers stated they form opinions about young children’s attachment quality in all or most of their investigations. Further, most respondents did not employ systematic assessments, and none made use of adequately validated attachment methods. Finally, most respondents made far-reaching inferences from individuals’ attachment classifications. We conclude that there is a substantial research-practitioner gap, presumably stemming in large part from difficulties translating group-based research to use at the level of the individual. We call for co-created research and application projects. We also urge attachment researchers to employ more conscientious knowledge dissemination strategies, and to invest efforts in developing attachment-informed assessments that better match the needs of CP workers (cf. Cyr et al., Citation2020). Finally, we cry out for better structural conditions for the many CP workers called upon to carry out one of society’s most important tasks.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to our respondents for participating despite high work-load pressure.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. N. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Psychology Press.

- Alexius, K., & Hollander, A. (2014). Care assessments concerning involuntary removal of children from intellectually disabled parents. The Journal of Social Welfare & Family Law, 36(3), 295–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/09649069.2014.933591

- Bakermans‐kranenburg, M. J., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2007). Research review: Genetic vulnerability or differential susceptibility in child development: The case of attachment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48(12), 1160–1173. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01801.x

- Beckwith, H. (2021). Understandings of attachment theory for clinical practice [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.78837

- Bifulco, A., Jacobs, C., Bunn, A., Thomas, G., & Irving, K. (2008). The attachment style interview (ASI): A support-based adult assessment tool for adoption and fostering practice. Adoption & Fostering, 32(3), 33–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/030857590803200306

- Bilson, A., & Munro, E. H. (2019). Adoption and child protection trends for children aged under five in England: Increasing investigations and hidden separation of children from their parents. Children and Youth Services Review, 96, 204–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.11.052

- Bowlby, J. (1969/1982). Attachment and loss: Attachment. Pimlico.

- Crittenden, P. M., & Baim, C. (2017). Using assessment of attachment in child care proceedings to guide intervention. In L. Dixon, D. F. Perkins, C. Hamilton-Giachritis, & L. A. Craig (Eds.), What works in child protection: An evidenced based approach to assessment and intervention in care proceedings (pp. 385–402). Wiley Blackwell Publishing.

- Cyr, C., Euser, E. M., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M., & van IJzendoorn, M. (2010). Attachment security and disorganization in maltreating and high-risk families: A series of meta-analyses. Development and Psychopathology, 22(1), 87–108. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579409990289

- Cyr, C., Dubois-Comtois, K., Paquette, D., Lopez, L., & Bigras, M. (2020). An attachment-based parental capacity assessment to orient decision-making in child protection cases: A randomized control trial. Child Maltreatment, 27(1), 66–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559520967995

- De Wolff, M. S., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (1997). Sensitivity and attachment: A meta‐analysis on parental antecedents of infant attachment. Child Development, 68(4), 571–591. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb04218.x

- Department for Education. (2018). Children in need of help and protection: Call for evidence. https:///www.gov.uk/government/consultations/children-in-need-of-help-and-protection-call-for-evidence

- Duschinsky, R. (2020). Cornerstones of attachment research. Oxford University Press.

- Faigman, D. L., Monahan, J., & Slobogin, C. (2014). Group to individual (G2i) inference in scientific expert testimony. The University of Chicago Law Review, 81(2), 417–480. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23762370

- Falch-Eriksen, A., & Backe-Hansen, E. (2018). Child protection and human rights: A call for professional practice and policy. In A. Falch-Eriksen & E. Backe-Hansen (Eds.), Human Rights in child protection: Implications for professional practice and policy (pp. 1–14). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fearon, R. P., Bakermans‐kranenburg, M. J., van IJzendoorn, M. H., Lapsley, A. M., & Roisman, G. I. (2010). The significance of insecure attachment and disorganization in the development of children’s externalizing behavior: A meta‐analytic study. Child Development, 81(2), 435–456. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01405.x

- Forslund, T., Granqvist, P., van IJzendoorn, M. H., Sagi-Schwartz, A., Glaser, D., Steele, M., Hammarlund, M., Schuengel, C., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Steele, H., Shaver, P. R., Lux, U., Simmonds, J., Jacobvitz, D., Groh, A. M., Bernard, K., Cyr, C., Hazen, N. L., Foster, S., & Duschinsky, R. (2021a). Attachment goes to court: Child protection and custody issues. Attachment & Human Development, 24(1) , 1–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2020.1840762

- Forslund, T., Hammarlund, M., & Granqvist, P. (2021b). Admissibility of attachment theory, research and assessments in child custody decision‐making? Yes and No! New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2021(180), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/cad.20447

- Gibson, K., Samuels, G., & Pryce, J. (2018). Authors of accountability: Paperwork and social work in contemporary child welfare practice. Children and Youth Services Review, 85, 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.12.010

- Goldberg, S. (2000). Attachment and Development. Routledge.

- Granqvist, P. (2016). Observations of disorganized behaviour yield no magic wand: Response to Shemmings. Attachment & Human Development, 18(6), 529–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2016.1189994

- Granqvist, P., Sroufe, L. A., Dozier, M., Hesse, E., Steele, M., van IJzendoorn, M., Solomon, J., Schuengel, C., Fearon, P., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M., Steele, H., Cassidy, J., Carlson, E., Madigan, S., Jacobvitz, D., Foster, S., Behrens, K., Rifkin-Graboi, A., Gribneau, N., & Duschinsky, R. (2017). Disorganized attachment in infancy: A review of the phenomenon and its implications for clinicians and policy-makers. Attachment & Human Development, 19(6), 534–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2017.1354040

- Granqvist, P. (2021). The God, the blood, and the fuzzy: Reflections on Cornerstones and two target articles. Attachment & Human Development, 23(4), 412–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2021.1918452

- Griffiths, A., Royse, D., Culver, K., Piescher, K., & Zhang, Y. (2017). Who stays, who goes, who knows? A state-wide survey of child welfare workers. Children and Youth Services Review, 77, 110–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.04.012

- Groh, A. M., Roisman, G. I., van IJzendoorn, M. H., Bakermans‐kranenburg, M. J., & Fearon, R. P. (2012). The significance of insecure and disorganized attachment for children’s internalizing symptoms: A meta‐analytic study. Child Development, 83(2), 591–610. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01711.x

- Groh, A. M., Fearon, R. P., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., van IJzendoorn, M. H., Steele, R. D., & Roisman, G. I. (2014). The significance of attachment security for children’s social competence with peers: A meta-analytic study. Attachment & Human Development, 16(2), 103–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2014.883636

- Groh, A. M., Fearon, R. P., van IJzendoorn, M. H., Bakermans‐kranenburg, M. J., & Roisman, G. I. (2017). Attachment in the early life course: Meta‐analytic evidence for its role in socioemotional development. Child Development Perspectives, 11(1), 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12213

- Jones-Mason, K., Behrens, K. Y., & Gribneau Bahm, N. I. (2021). The psychobiological consequences of child separation at the border: Lessons from research on attachment and emotion regulation. Attachment & Human Development, 23(1), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2019.1692879

- Karsten, E. (2018). Socialsekreterares arbetsmiljö [Social workers’ working environment] (Report no. 2015/051465). Arbetsmiljöverket [Swedish Work Environment Authority]. https://www.av.se/globalassets/filer/publikationer/rapporter/slutrapport-socialsekreterares-arbetsmiljo.pdf

- Konijn, C., Admiraal, S., Baart, S., van Rooij, F., Stams, G.-J., Colonnesi, C., Lindauer, R., & Assink, M. (2018). Foster care placement instability: A meta-analytic review. Children and Youth Services Review, 96, 483–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.12.002

- Lavee, E., & Strier, R. (2018). Social workers’ emotional labour with families in poverty: Neoliberal fatigue? Child & Family Social Work, 23(3), 504–512. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12443

- Lundström, T., & Sallnäs, M. (2019). Barnskyddets innersta kärna – om tvångsplaceringar som motiveras av barns hemförhållanden [The inner core of child protection – on coercive placement motivated by abuse or neglect]. Socialvetenskaplig Tidskrift, 26(3–4), 283–302.

- Main, M. (1990). Cross-Cultural studies of attachment organization: Recent studies, changing methodologies, and the concept of conditional strategies. Human Development, 33(1), 48–61. https://doi.org/10.1159/000276502

- Main, M., & Solomon, J. (1990). Procedures for identifying infants as disorganized/disoriented during the Ainsworth Strange Situation. In M. T. Greenberg, D. Cicchetti, & E. M. Cummings (Eds.), Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research, and intervention (pp. 121–160). The University of Chicago press.

- Melinder, A., van der Hagen, M. A., & Sandberg, K. (2021). In the best interest of the child: The Norwegian approach to child protection. International Journal on Child Maltreatment: Research, Policy and Practice, 4(3), 209–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42448-021-00078-6

- Mnookin, R. H. (1975). Child-Custody adjudication: Judicial functions in the face of indeterminacy. Law & Contemporary Problems, 39(3), 226–293. https://doi.org/10.2307/1191273

- Neal, T. M., Slobogin, C., Saks, M. J., Faigman, D. L., & Geisinger, K. F. (2019). Psychological assessments in legal contexts: Are courts keeping “junk science” out of the courtroom? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 20(3), 135–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100619888860

- Padrón, E., Carlson, E. A., & Sroufe, L. A. (2014). Frightened versus not frightened disorganized infant attachment: Newborn characteristics and maternal caregiving. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84(2), 201–208. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0099390

- Park, T. Y., & Shaw, J. D. (2013). Turnover rates and organizational performance: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(2), 268–309. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030723

- Pinquart, M., Feußner, C., & Ahnert, L. (2013). Meta-Analytic evidence for stability in attachments from infancy to early adulthood. Attachment & Human Development, 15(2), 189–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2013.746257

- Pope, A. (1709/2017). An Essay on Criticism. CUP archive.

- Robertson, L., & Broadhurst, K. (2019). Introducing social science evidence in family court decision-making and adjudication: Evidence from England and Wales. International Journal of Law, Policy, and the Family, 33(2), 181–203. https://doi.org/10.1093/lawfam/ebz002

- Sallnäs, M., Vinnerljung, B., & Kyhle Westermark, K. (2004). Breakdown of teenage placements in Swedish foster and residential care. Child & Family Social Work, 9(2), 141–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2004.00309.x

- Shemmings, D., & Shemmings, Y. (2011). Understanding disorganized attachment: Theory and practice for working with children and adults. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Skivenes, M., & Sørsdal, L. M. (2018). The child’s best interest principle across child protection jurisdictions. In A. Falch-Eriksen & E. Backe-Hansen (Eds.), Human rights in child protection: Implications for professional practice and policy (pp. 59–88). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Søberg Bjerre, L., Jacob Madsen, O., & Petersen, A. (2021). ‘But what are we doing to that baby?’ Attachment, psy-Speak and designed order in social work. European Journal of Social Work, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2020.1870439

- Spieker, S. J., Crittenden, P. M., Landini, A., & Grey, B. (2021). Using parental attachment in family court proceedings: An empirical study of the DMM‐AAI. Child Abuse Review, 30(6), 550–564. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2731

- Steele, H., & M. Steele (Eds.). (2017). Handbook of attachment-based interventions. Guilford Press.

- Swedish Central Bureau of Statistics (n.d.). Karta över NUTS-indelningen i Sverige från 2018-01-01. https://www.scb.se/contentassets/4e32573a1c8f46d1a5ca29e381fb462f/nuts_1_2_3_20080101.pdf

- Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. (2018a, October 20). Grundbok i BBIC – Barns Behov i centrum. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/ovrigt/2018-10-20.pdf

- Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare (2018b, October 20). Metodstöd för BBIC. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/ovrigt/2018-10-21.pdf

- Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare (2019, January 26). IAS (Intervju om Anknytningsstil). https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/kunskapsstod-och-regler/omraden/evidensbaserad-praktik/metodguiden/ias-intervju-om-anknytningsstil/

- Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare (2021, March 9). Bilaga - Resultat kommuner, län och riket - Social barn- och ungdomsvård - Öppna jämförelser socialtjänst 2020. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/statistik-och-data/oppna-jamforelser/socialtjanst/social-barn-och-ungdomsvard/

- UN General Assembly. (1989, November 20). Convention on the Rights of the Child. United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 1577.

- van IJzendoorn, M. H., Bakermans, J. J., Steele, M., & Granqvist, P. (2018a). Diagnostic use of Crittenden’s attachment measures in Family Court is not beyond a reasonable doubt. Infant Mental Health Journal, 39(6), 642–646. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21747

- van IJzendoorn, M. H., Steele, M., & Granqvist, P. (2018b). On exactitude in science: A map of the empire the size of the empire. Infant Mental Health Journal, 39(6), 652–655. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21751

- van IJzendoorn, M. H., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Duschinsky, R., Goldman, P. S., Fox, N. A., Gunnar, M. R., Johnson, D. E., Nelson, C. A., Reijman, S., Skinner, G. C. M., Zeanah, C. H., & Sonuga-Barke, E. J. S. (2020). Institutionalisation and deinstitutionalisation of children I: A systematic and integrative review of evidence regarding effects on development. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(8), 703–720. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30399-2

- van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. (2021). Replication crisis lost in translation? On translational caution and premature applications of attachment theory. Attachment & Human Development, 23(4), 422–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2021.1918453

- Verhage, M. L., Schuengel, C., Madigan, S., Fearon, R. M., Oosterman, M., Cassibba, R., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2016). Narrowing the transmission gap: A synthesis of three decades of research on intergenerational transmission of attachment. Psychological Bulletin, 142(4), 337–366. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000038

- White, S., Gibson, M., & Wastell, D. (2019). Child protection and disorganized attachment: A critical commentary. Children and Youth Services Review, 105, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104415

- Windelband, W. (1904). Geschichte und naturwissenschaft. Humboldt-Universität zu.

- Wulczyn, F., Kogan, J., & Harden, B. J. (2003). Placement stability and movement trajectories. The Social Service Review, 77(2), 212–236. https://doi.org/10.1086/373906

- Zeegers, M. A., Colonnesi, C., Stams, G. J. J., & Meins, E. (2017). Mind matters: A meta-analysis on parental mentalization and sensitivity as predictors of infant–parent attachment. Psychological Bulletin, 143(12), 1245. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000114