ABSTRACT

During the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns made it impossible for parenting coaches to reach the families without digital means of communication. Several studies were initiated to transform existing parenting interventions into hybrid or fully online versions and to examine their feasibility, acceptability and efficacy. We present one such transformation in detail, the Virtual-VIPP which is based on Video-feedback Intervention to promote Positive Parenting and Sensitive Discipline (VIPP-SD). Furthermore, we report a systematic review of 17 published trials with online versions of parenting programs. Overall, online parenting interventions seem feasible to implement, are well-received by most families, and to show equivalent effects to face-to-face approaches. Careful preparation of technicalities and monitoring of fidelity are prerequisites. Advantages of online parenting interventions are their potentially broader reach, more detailed process documentation, and better cost-utility balance. We expect that online parenting interventions are here to stay, but their efficacy needs to be rigorously tested.

The COVID-19 pandemic has not only been a cause of serious morbidity and mortality among parents and children but has also impacted on their physical and mental well-being and health. A simple but alarming example are the large weight gains observed in the “Stress in America” pandemic survey of the American Psychological Association (American Psychological Association, Citation2021). In the total population these weight gains were estimated to amount to 100 million extra kilograms. Parents were among those who gained most weight during the lockdowns as more than half reported undesired weight gains of 16 kg on average. Stress seems a plausible cause of these weight changes as a large majority of the parents in this survey reported increased sleeping problems, and 29% (mothers) to 48% (fathers) admitted to drinking more alcohol to cope with stress.

For children the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been documented in the area of school achievements. In one of the largest and most valid studies to date, Per Engzell et al. (Citation2021) examined the impact of the 8-week lockdown of elementary schools in the Netherlands. Even such a relatively short school closure led to substantial learning losses in math, spelling and reading in a large cohort of 350,000 children. Comparing three assessments before and two assessments after the lockdown, the overall loss was 0.08 SD, equivalent to one-fifth of a school year. Maybe even more important were the significantly more serious academic losses of the children from lower socio-economic status families compared to their peers from more privileged families. Such disparities might turn out to be persistent over time if no extra support for the most affected children becomes available.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, interactions of parents with their children may have become harsher and child maltreatment more frequent. In a propensity score matching study comparing pre-COVID levels of harsh parenting with harsh parenting reports during the pandemic, Sari et al. (Citation2021) found an increase in the total score on 6 items of the Parent-Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS, Straus et al., Citation1998). More harsh parenting was reported by the parents of 1,236 toddlers on the items “shook my child,” “called my child names,” and “called my child stupid, lazy, or something like that.”

Some support for a potential “hidden pandemic” of harsh and maltreating parenting was also observed in Google searches before and during COVID-19 for terms derived from the CTS (yelled, screamed, shouted, cursed, swore, threatened, pinched, hit, slapped, beat, shook). In an infodemiology study Riem et al. (Citation2021) extracted weekly raw search counts from the Google Trends data and applied an autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model to estimate the excess search count after the start of the pandemic. Searches with psychological abuse terms increased 88% overall. For example, “parents cursed” showed a 196% increase. Searches for physical abuse terms increased with 21%. An example was “parents beat” showing a 27% increase (Riem et al., Citation2021).

It is clear that more than ever families need support in pandemic times but such support is especially difficult to provide because of lockdowns. Therefore, it is urgent to develop online (preventive) parenting interventions. In the current paper, we first present a case study of the development of an online version of our Video-feedback to promote Positive Parenting and Sensitive Discipline (virtual VIPP-SD) to discuss in detail some of the potentials and challenges of online transformation of an existing, well-validated program. This example serves as a steppingstone to a more general review and discussion of online attachment-based interventions developed during COVID-19.

Video feedback intervention to promote positive parenting-sensitive discipline (VIPP-SD)

One of the parent intervention or coaching programs that might support families in stressful pandemic times is the VIPP-SD suite of modalities using video-feedback to stimulate parents to reflect on daily interactions with their children (Juffer et al., Citation2017). Based on attachment theory and the social learning approach, the goal of VIPP-SD is to enhance parental sensitive responsiveness and limit setting. The VIPP-SD induced changes in parenting interactions would facilitate the development of attachment security and a decrease in child externalizing behavior problems (Juffer et al., Citation2017; Van IJzendoorn et al., Citation2022).

Core characteristics of VIPP-SD are the following. The program is home-based and focuses on the interaction between parent or caregiver and child. In six sessions, the parents learn to observe their interactions with the child more closely with help of video-recordings made at home. The feedback in the first two sessions covers mainly positive interactions that stimulate reflective thinking and create a sense of efficacy and empowerment in the parents. The intervener is not the expert telling the parent how to deal with the child but is supporting in a sensitive way the active involvement of the parent in reflecting on the video-taped child behavior and their interactions with the child.

The regular face-to-face VIPP-SD has been shown to be effective in a large variety of families. For example, in the pre-registered Healthy Start Happy Start pragmatic randomized controlled trial O’farrelly et al. (Citation2021) implemented VIPP-SD in 300 British families with one-to-three-year-old children who were at risk for externalizing issues. The intervention group of 151 children showed less conduct problems on the Preschool Parental Account of Children’s Symptoms (PPACS) compared to the control group with care as usual (effect size amounted to Cohen’s d = 0.30, O’farrelly et al., Citation2021). Another example of a pre-registered RCT was a preemptive trial conducted in Australia with 104 families in which 12-months old children were screened for elevated signs of autism. At post-test two-years later, children in the intervention group showed significantly less signs of autism on the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (Cohen’s d = 0.40; Whitehouse et al., Citation2021).

During the past 30 years 25 RCTs in 8 countries have been conducted with more than 2,000 parents or caregivers and their children (age ranging from 6 months to 8 years). A large variety of families participated, struggling with poverty, minority status, maltreatment, externalizing problems, autism, physical disabilities or parental psychopathology. The combined effect sizes of these 25 RCTs were Cohen’s d = 0.37 for sensitive parenting and d = 0.47 for child attachment security (Van IJzendoorn et al., Citation2022). Most importantly, larger effect sizes for VIPP-SD on parenting were associated with larger effect sizes on child attachment security, suggesting a causal link between parenting and attachment. For details about the RCTs, we refer to of the meta-analytic report (Van IJzendoorn et al., Citation2022).

Table 1. Delivering the online sessions of virtual-VIPP.

Development of an online virtual VIPP

During the COVID-19 pandemic regular home-based video-feedback interventions were impossible to implement despite the urgent need for parenting support in these stressful times. Initiated and led by Eloise Stevens at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, an international working group with developers of VIPP-SD, VIPP trainers, supervisors and other experts in the field discussed the potential transformation of the original video-feedback coaching into an online format. The goal was to preserve the core ingredients of VIPP but adapt its content and structure to facilitate delivery in a secure online environment. The Virtual-VIPP protocol was envisioned as an adjunct to the regular VIPP manual that would remain central to the work of the interveners. A major hurdle seemed to be digitally transforming the core parts of VIPP including the recording of parent–child interactions at home and the reflection by the parent and the intervener on the video-clips in the next session.

After many different approaches were explored, a video-conferencing platform was deemed the most suitable and effective way of both recording the clips and delivering the feedback whilst retaining the most important tenets of the intervention. The use of video-conferencing technologies has been on the rise over the last 10 years due to their potential to close the gap between mental health care need and availability. A meta-analysis carried out by Batastini et al. (Citation2021) of 57 studies (43 examining intervention outcomes; 14 examining assessment reliability) published over the past two decades found that video-conferencing technologies consistently produced treatment effects that were largely equivalent to in-person delivered interventions.

The way Virtual-VIPP works is that the intervener has a video call with the parents and asks them to complete the VIPP interaction tasks on the call, trying to keep the activity within the screen frame. The interveners play an important role in supporting the parent to prepare the most suitable toys and set up a device such as a mobile phone, laptop or tablet to capture both them and their child completing the different tasks together. The intervener gives the parent live instructions on what to do in each task before the parent’s recording of the meeting, and it is this recording which is sent to the intervener and used for the clips they will reflect upon and discuss in a later session. The interveners share their screen with the parents to play the video clips back to them to provide opportunities for reflection and feedback.

The choice of an online platform is complicated because of the large (and fluctuating) number of options (Teams, Skype, ZOOM, Facetime, Whatsapp, Jitsi, Jami) and the various requirements it must fulfil. The following criteria for filming were taken into account:

Possible to record meeting to use as the feedback clips

Possible to capture only the parent’s screen in recordings

Possible to live guide parent through tasks via the same platform

Possible to capture the parent and children’s faces and the toys on screen

Furthermore, the following criteria were deemed relevant for the feedback part of VIPP:

Good quality picture and sound recording

Possible for the parents to see their child’s face and their own face clearly and to see the interactions between them on screen when watching the clips back

Possible for parents to see the intervener clearly whilst watching the clips back and receiving live feedback

Possible for intervener to see parent’s face clearly when feeding back and sharing the screen

Interveners and parents should also meet some generic requirements that include having an electronic device with camera, access to good (preferably fiber broadband) WIFI, a quiet private area in their home and the latest version of the chosen platform downloaded. These need to be explored by the intervener, with the parent, prior to agreeing to deliver VIPP to a family because VIPP will not be possible and the quality of clips cannot be ensured, if any of these criteria are not met (Stevens, Citation2021). A trial video call before starting the intervention is recommended to test the technicalities, which also creates the opportunity for the interveners to meet the children and observe their mobility, assessing the need for any adaptations to the program.

A key online VIPP adaptation is the structure of the program, with shorter weekly sessions instead of longer fortnightly ones (see ). This is because it was decided to split the recording of the clips and the video feedback into two separate sessions: completing the recording one week and feeding back on this interaction the following week, instead of doing the recording and the feedback on the previous sessions’ recordings in one visit as in the original in-person intervention. The combination of recording and feedback can take around 1.5 hours which was deemed to run the risk of “zoom lethargy” - as watching the clips back requires a lot of concentration even when face to face. It also means that contact between the intervener and parent is more frequent which helps to build and maintain the relationship with the parents that may otherwise be jeopardized by the intervener only meeting them virtually and not face-to-face.

Feasibility of virtual VIPP: A qualitative evaluation

An informal evaluation was carried out to gather information on how eight pioneering interveners who had been delivering Virtual-VIPP over a period of 18 months during the pandemic, had experienced the intervention. Three interveners were delivering VIPP with children under 1 year who were not yet walking and five were working with children over 1 year who were walking – making it more challenging to deliver Virtual-VIPP to the parents because the children are mobile and able to move out of the video frame. In this preliminary qualitative evaluation, unfortunately it was not possible to include parents’ feedback and perspectives.

The main question was whether the online intervention was acceptable and feasible to deliver and receive, at least from the perspective of the interveners. The interveners were encouraged to keep notes after each session in their logbooks, about how the session went and to make video-records of their feedback sessions to feed into the evaluation of the model. Furthermore, some standardized questionnaires were developed for interveners to complete at the end of a Virtual VIPP intervention, to collect quantitative and qualitative data. The questions covered what they thought worked and what they struggled with, how they experienced the recording sessions, the feedback sessions and how they felt the parent received the different elements of the program (see Stevens, Citation2021).

Six out of the eight interveners agreed or strongly agreed that technicalities were not a stumbling block for effective delivery, with the devices and internet available to both intervener and parent not causing too many problems for the majority. This encouraging evaluation was supported by five of eight interveners disagreeing with statements like “I struggled to deliver VIPP virtually” and “the parent struggled to receive Virtual-VIPP,” and five interveners agreeing or strongly agreeing that they felt confident when delivering VIPP virtually, with two rating themselves as neutral and only one strongly disagreeing, indicating that the delivery method also felt acceptable for most of the interveners.

Rapport between intervener and parent seems critical for effective delivery (see Stolk et al., Citation2008) but also more difficult to create and retain online. Nevertheless, six of eight interveners agreed that they had a good rapport with parents in both the task recording sessions and during the feedback sessions. A couple of interveners commented that the relationship was not hindered in any way by being online and in some cases was even stronger than the majority seen face to face due to having the parent’s full focus on the screen. One intervener said: “I have preferred doing the VIPP virtually. I do not feel anything was lost by doing it online. I was able to build a rapport with the parent in the same way I believe was possible face-to-face.”

Initial findings showed that most interveners preferred the weekly structure of Virtual-VIPP. This was for a number of reasons – it helped parents to remember better what happened the week before and facilitated reflection on their interactions; it supported the building of a relationship with the parent; and by splitting the sessions into two, the feedback sessions could be planned for times when the child was asleep or in childcare. This was particularly welcomed as in the face-to-face VIPP the child’s presence during feedback can be a serious distraction for the parent and intervener.

As mentioned above, the aim of our investigation was to ensure that the intervention was delivered as close to the original manual as possible. Six out of eight interveners agreed or strongly agreed that they were able to follow the VIPP manual closely when delivering Virtual-VIPP (e.g. recording all set tasks, delivering feedback as per instructions) and no one strongly disagreed. The qualitative evaluation also found that interveners delivering Virtual-VIPP perceived similar benefits for parents to those who have received the face-to-face version – with six of eight agreeing that the parents started to notice moments where they could have done something differently in the video clips (turning points). All interveners felt that parents were learning something new about their child, and five out of eight felt that the parents’ confidence increased throughout the program.

Work in progress with virtual-VIPP

More work is needed to establish the feasibility of the Virtual VIPP in other cultures, and to rigorously test its effectiveness. In Singapore, a large scale RCT of Virtual VIPP has started with 150 mothers who are considered at risk of depression during pregnancy. This is part of a multi-million-dollar contract awarded by Wellcome Leap, to an international consortium led by Sir Peter Gluckman at the University of Auckland. In Vietnam, Nhu Tran at the Institute for Social Development Studies plans a feasibility study including parents with high stress and high scores on dysfunctional parent–infant interactions (Parenting Stress Index scale), to test the impact of Virtual-VIPP on parental sensitivity and attachment security.

The Anna Freud Centre has been delivering Virtual-VIPP as part of their “Mind the Dad” service for new fathers in the perinatal period, which is completely online, including all the assessments and interventions. Furthermore, one of the VIPP trainers has now adapted the training for interveners to online delivery – spreading it out from four full days to seven shorter days. For two reasons, Virtual-VIPP creates new opportunities beyond the challenges of the pandemic. First, video-feedback conducted at home is relatively expensive because it requires travelling, so the cost – benefit balance of Virtual VIPP might be affected in a positive way. Second, in Low and Middle Income Countries many families are living in remote areas but do have access to internet facilities, and Virtual-VIPP might be the gateway for parenting support to otherwise inaccessible families.

Review of other online parent support interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic

During the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2021) several parenting intervention studies were ongoing and researchers were forced to go online midstream to keep reaching their families. This change of gears resulted in hybrid versions of parent coaching programs that otherwise would have remained face to face. Researchers who had planned an intervention project to start in 2020 or 2021 needed to develop a completely revised online variant if they wanted to conduct their study during these unpredictable years. In these dark times, the development of hybrid or online parenting interventions has gained great momentum and the fortuitous outcome might be a strongly intensified use of potentially (cost-)effective online approaches in a future with and without lockdowns. One example is Virtual-VIPP as presented above, but much more work has been done with great promise of feasibility and efficacy.

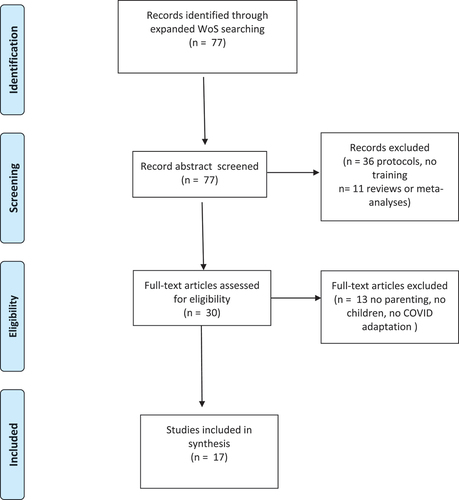

Here we take stock of the intervention studies conducted during the pandemic years 2020–2021 on feasibility or efficacy of hybrid or completely online parenting support programs. The following search string was used to trace relevant papers in Web of Science: ((TS=((digital OR E-Health OR Telehealth OR online OR internet OR virtual) AND (parent* training OR parent* intervention OR parent* coach*))) AND TS=(covid*)) AND TS=(experiment* OR trial). This search was conducted on 23 April 2022, and identified 77 potentially relevant papers (see for a flow chart). The search of the references in the papers included in the current special issue did not yield new studies. Screening of titles and abstracts led to the exclusion of 47 papers because they presented reviews (k = 11), focused on adult offspring, took place in school settings, or did not describe empirical parent coaching studies (e.g. protocols of study designs) (k = 6). Full-text screening was done on the remaining 30 papers independently by two coders (MBK, vIJ) who had 87% agreement. Diverging classifications were discussed and consensus was established, resulting in k = 17 studies in the final set.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram for search of COVID-19 related studies on feasibility and effectiveness of online parenting support.

The studies were coded for general characteristics: mean age of the children; country; type of sample (typical; low SES; clinical), type of intervention (online – hybrid; video – app). Quality indicators pertained to the study designs (number of participants, RCT; quasi-experiment; pilot; development case study), fidelity check, blind coding, intent-to-treat analysis, correct statistics, overall Risk of Bias). See for study characteristics and quality ratings of eight studies with a randomized controlled design.

Table 2. Overview of randomized controlled studies on online parenting interventions.

Randomized controlled trials

All eight randomized controlled trials (RCTs) starting just before or during the pandemic with online versions of face-to-face parent training showed satisfactory acceptance and feasibility. For example, Aranki et al. (Citation2022) reported that Applied Behavior Analytic (ABA) interventions met with initial hesitance of a substantial percentage (40%) of the parents of children with autism to start participating in the online variant of the training (but see Yi & Dixon, Citation2021, for an effective acceptance and commitment training component added to ABA). However, as soon as parents had decided to participate, they benefitted from the training, and their demographic characteristics were not different from those parents who refused to be enrolled in the online training. These findings of some hesitance to be enrolled in an online coaching program and no difference between parents who accepted versus declined enrollment was also found by Baggett et al. (Citation2021). They successfully used a mobile intervention to improve maternal mood and positive parenting practices in a sample of low-income, depressed Black mothers and their infants.

Six of eight online parenting interventions documented promising evidence for their effectiveness in RCTs with a variety of samples and intervention modalities. For example, a chatbot with real-time consultation messages provided parents with vaccination-related information and motivation boosters which was effective in stimulating them to get their children vaccinated (Hong et al., Citation2021). Using only two video sessions and three email reminders to implement emotion regulation strategies for coping with the pandemic stresses, Preuss et al. (Citation2021) showed that cognitive reappraisal was effective in lowering individual stress and indirectly also parenting stress. In a sample of high-anxiety mothers of preschoolers, Zengin et al. (Citation2021) managed to lower state (but not trait) anxiety levels with four online sessions of a Solution-Focused Support Program. Twelve weekly teleconferencing sessions with internet-delivered parent–child interaction therapy (I-PCIT) for mothers with non-metastatic cancer and their children with oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) showed significant improvements in children’s impulsiveness in the short- and long-run (Sadeghi et al., Citation2021). A final example is the internet version of comprehensive behavioral intervention for tics (ICBIT) for tic disorders in youth, guided by parents (Rachamim et al., Citation2021), with similar effectiveness on tics reduction and improved self-esteem as found with face-to-face delivery.

In terms of Risk of Bias, it can be noted that only a few studies were preregistered, which is perhaps no wonder as the COVID-19 pandemic was unexpected and adaptations to intervention studies were made at short notice. Another potential bias is the lack of blind coding, which is evident when the outcome is self-reported and participants are well aware that they received an intervention. This points to the need of independent observation of outcome measures. Attrition was high in some studies, but very low in others. Further work on the causes of attrition in online interventions is badly needed. Is higher attrition related to lower digital competence or less digital experience of the parents? Are mothers and fathers equally at ease with the technical challenges involved? Does scarcity of time even lead to a preference for the more time-efficient online approach? Risk of bias may partly explain the wide range in effect sizes, varying from negative and small to positive and very large. Compared to the overall combined effect sizes of parent training programs in the USA reported by HOMVEE (d = 0.10; Sama-Miller et al., Citation2020) and of four popular home-visiting programs stimulating positive parenting (d = 0.11; Michalopoulos et al., Citation2019), effect sizes larger than d = 1.00 seem unrealistic and those studies that found such strong effects may be the inspiring first trials that cannot be replicated with similar effect sizes in later studies (the so-called winner’s curse). Small samples may be particularly vulnerable for outlying effect sizes, and replication of the intervention programs in larger samples may provide more realistic estimates of the effects that can be expected.

Non-randomized studies

Nine studies tried to test the effectiveness of online interventions using designs without a control group or examining pre-test to post-test development of participants in non-equivalent groups. Because the validity of conclusions about effectiveness remains equivocal due to potential confounding with pre-existing differences, absence of participant blindness to the intervention, or biases in self-reported outcome measures, we focus on acceptability and fidelity of these online interventions. Although non-random, a lot of pioneering effort has been invested in the development of online or hybrid versions of existing programs during the COVID-19 pandemic and they will therefore be briefly discussed here.

Overall, the remarkable conclusion in a large variety of parent coaching programs applied in different typical and atypical samples from a variety of countries is that participants evaluate online versions as acceptable and mostly with high satisfaction. Interveners and researchers evaluate the fidelity of program implementation as sufficient, and they report potential effectiveness. Online interventions directed at parental behavior elicited high levels of parental satisfaction (Doğan Merih et al., Citation2021). For example, the evidence-based Family Foundations program targeting parent mental health, conflict and co-parenting through video-conferencing was met with enthusiasm by the participants (Giallo et al., Citation2021). The online Celebrating Families! intervention program for parents struggling with substance abuse was also considered highly satisfactory by the participants who perceived progress in parenting skills thanks to the received support (Cohen & Tisch, Citation2021).

Challenges and limitations of online approaches were mentioned as well. The online behavioral parent training programs for disruptive child behavior Helping Our Toddlers, Developing Our Children’s Skills (HOT DOCS) BPT met with less parent satisfaction but seemed to show equal effectiveness compared to face-to-face implementation (Agazzi et al., Citation2021). Several studies mentioned technical difficulties (e.g. Fogarty et al., Citation2021) such as incompatibility of web browsers and limited search engine capability (Shorey et al., Citation2021). Some studies included only participants with digital expertise to avoid technical issues (Şenol & Üstündağ, Citation2021). Giallo et al. (Citation2021) noticed that the online version of their program triggered more directive behavior of the interveners and reported some complaints about lack of cultural diversity in the pre-recorded videoclips. In the online Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up (ABC) parent coaching (Schein et al., Citation2022, this issue), ongoing supervision, weekly fidelity checks, and flexibility of the coaches in arranging meetings were deemed to be major components of its success. In the online modality of the Pivotal Response Treatment (PRT) model for families with a child on the autism spectrum (White et al., Citation2021), close cooperation between parents and interveners seemed critical for acceptance, fidelity and effectiveness of the intervention. The rapport between intervener and parent is critical for effectiveness of in vivo interventions (Stolk et al., Citation2008) and might be equally important but more difficult to reach in online interventions.

General discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a pressure cooker for the development of online approaches to family coaching in a variety of domains. Whatever the label used for online parenting interventions (virtual, digital, online, hybrid, eHealth type, etc.), they all have in common the goal of reaching families in need of support in distant places or stressful times that make face-to-face coaching less feasible or even impossible. What can be gleaned from the fledgling trials to develop and examine online parent training is the promise that they can be acceptable for the families, technically feasible, and maybe not less effective compared to face-to-face methods. Although the verdict about effectiveness of online parenting interventions still waits for a series of rigorous RCTs, careful preparation of technicalities, thoughtful adaptation of protocols, and stringent observation of fidelity pave the way to demonstration of effectiveness in future RCTs. Special attention might go to long-term effects of these interventions to see whether online short-term effects translate into persistent long-term changes in parenting and child development.

One of the (unfortunately very few) long-term collateral benefits of COVID-19 is the potential shift in the balance between costs and benefits of parenting interventions. Policy makers are increasingly pushing for so-called “cost-utility” analyses of interventions (Van IJzendoorn & Bakermans-Kranenburg, Citation2020). Health economists have developed methods to assess cost-utility of psychological and biomedical treatments and (preventive) interventions with help of measures such as the EuroQol 5 Dimensions scale (EQ-5D). These measures assess the potential gain in Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYs) of interventions. For parenting interventions several issues with this approach can be noticed. For example, treatment of physical illness is algorithmically favored over improving mental health, and adult criteria for QALYs are often used for children as well (see Van IJzendoorn & Bakermans-Kranenburg, Citation2020). Most importantly, home-based interventions that require visits to the family weigh heavily on the “costs” part of the balance compared to clinic visits, and the same is true for interventions targeting one family per session instead of addressing groups of parents and/or their children. With a larger numerator and a smaller denominator cost-utility of attachment-based interventions such as VIPP-SD or ABCD are traditionally at a disadvantage, but online versions may make them more cost effective.

In sum, online or virtual parenting interventions show great promise because they seem feasible, show a better balance between costs and benefits, and might be equally effective to face-to-face parent training. We expect an increasing trend toward online interventions in coming years, also after the end of the pandemic, and such interventions might become more accessible to families in LMICs or non-WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic) countries across the globe. Much work however still has to be done to prove the promise to be reality (see Bao & Moretti, 2023 this issue; Labella, Margolis, & Dozier, 2023 this issue; Gershy, Cohen, & Atzaba Poria, 2023 this issue).

Author contributions

MJB-K: conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, validation, writing – review and editing. ES: data curation, writing – original draft preparation, writing – review and editing. MHvIJ: conceptualization, supervision, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, validation, writing – original draft preparation, writing – review and editing.

Competing interest. Together with Femmie Juffer, MHVIJ and MJB-K are the developers of the VIPP-SD program. They developed and evaluated the intervention on a nonprofit basis. ES is a VIPP supervisor and early years therapist.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agazzi, H., Hayford, H., Thomas, N., Ortiz, C., & Salinas-Miranda, A. (2021). A nonrandomized trial of a behavioral parent training intervention for parents with children with challenging behaviors: In-person versus internet-HOT DOCS. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 26(4), 1076–1088. https://doi.org/10.1177/13591045211027559

- American Psychological Association. (2021). Stress in America™ one year later, a new wave of pandemic health concerns. https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2021/sia-pandemic-report.pdf

- Aranki, J., Wright, P., Pompa-Craven, P., & Lotfizadeh, A. D. (2022) Acceptance of telehealth therapy to replace in-person therapy for autism treatment during covid-19 pandemic: An assessment of patient variables. Telemedicine Journal and E-Health: The Official Journal of the American Telemedicine Association, 28(9),1342–1349. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2021.0397

- Baggett, K. M., Davis, B., Mosley, E. A., Miller, K., Leve, C., & Feil, E. G. (2021). Depressed and socioeconomically disadvantaged mothers’ progression into a randomized controlled mobile mental health and parenting intervention: A descriptive examination prior to and during COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 719149. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.719149

- Batastini, A. B., Paprzycki, P., Jones, A. C. T., & MacLean, N. (2021) Are videoconferenced mental and behavioral health services just as good as in-person? A meta-analysis of a fast-growing practice, Clinical Psychology Review, 83, 101944, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101944.

- Cohen, E., & Tisch, R. (2021). The online adaptation and outcomes of a family-based interventionaddressing substance use disorders. Research on Social Work Practice, 31(3), 244–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731520975860

- Doğan Merih, Y., Karabulut, Ö., & Sezer, A. (2021). Is online pregnant school training effective in reducing the anxiety of pregnant women and their partners during the COVID-19 pandemic? Bezmialem Science, 9(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.14235/bas.galenos.2020.4718

- Engzell, P., Frey, A., & Verhagen, M. D. (2021). “Learning Loss Due to School Closures During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118, e2022376118 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2022376118

- Fogarty, A., Jones, A., Seymour, M., Savopoulos, P., Evans, K., O’brien, J., O’dea, L., Clout, P., Auletta, S., & Giallo, R. (2021). The parenting skill development and education service: Telehealth support for families at risk of child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child & Family Social Work, 27(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12890

- Giallo, R., Fogarty, A., Seymour, M., Skinner, L., Savopoulos, P., Bereznicki, A., Talevski, T., Ruthven, C., Bladon, S., Goldfeld, S., Brown, S. J., & Feinberg, M. (2021). Family foundations to promote parent mental health and family functioning during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia: A mixed methods evaluation. Journal of Family Studies, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2021.2019606

- Hong, Y. -J., Piao, M., Lee, J. -H., & Kim, J. (2021). Development and evaluation of a child vaccination chatbot real-time consultation messenger service during the COVID-19 pandemic. Applied Sciences, 11(24), 12142. https://doi.org/10.3390/app112412142

- Juffer, F., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2017). Pairing attachment theory and social learning theory in video-feedback intervention to promote positive parenting. Current Opinion in Psychology, 15, 189–194.

- Michalopoulos, C., Faucetta, K., Hill, C. J., Portilla, X. A., Burrell, L., Lee, H., Duggan, A., & Knox, V. (2019). Impacts on family outcomes of evidence-based early childhood home visiting: Results from the mother and infant home visiting program evaluation. OPRE Report 2019-07. Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- O’farrelly, C., Watt, H., Babalis, D., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & Ramchandani, P. G. (2021). A brief home-based parenting intervention to reduce behavior problems in young children: A pragmatic randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(5), 567–576. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.6834

- Preuss, H., Capito, K., Van Eickels, R. L., Zemp, M., & Kolar, D. R. (2021). Cognitive reappraisal and self-compassion as emotion regulation strategies for parents during COVID-19: An online randomized controlled trial. Internet Interventions, 24, 100388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2021.100388

- Rachamim, L., Mualem-Taylor, H., Rachamim, O., Rotstein, M., & Zimmerman-Brenner, S. (2021). Acute and long-term effects of an internet-based, self-help comprehensive behavioral intervention for children and teens with tic disorders with comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or obsessive compulsive disorder: A re-analysis of data from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11010045

- Riem, M. M. E., De Carli, P., Guo, J., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Lodder, P. (2021). Internet Searches for Terms Related to Child Maltreatment During COVID-19: Infodemiology Approach. JMIR Pediatr Parent, 4(3), e27974. https://doi.org/10.2196/27974

- Sadeghi, P., Mirzaei, G., Reza, F., Khanjani, Z., Golestanpour, M., Nabavipour, Z., & Dastanboyeh, M. (2021). COVID-19 and tele-health, effectiveness of internet-delivered parent-child interaction therapy on impulsivity index in children with non-metastatic cancer parents: A pilot randomized controlled trial. World Cancer Research Journal, 8, e2043. https://doi.org/10.32113/wcrj_20217_2043

- Sama-Miller, E., Lugo-Gil, H. J., Akers, L., & Coughlin, R. (2020). Home visiting evidence of effectiveness HomeVEE) systematic review. OPRE Report 2020-151. OPRE.

- Sari, N. P., Van IJzendoorn, M. H., Jansen, P. W., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & Riem, M. M. E. (2021). Higher Levels of Harsh Parenting During the Covid-19 Lockdown in the Netherlands. Child Maltreatment. https://doi.org/10.1177/10775595211024748

- Schein, S. S., Roben, C. K. P., Costello, A. H., & Dozier, M. (2022, January). Assessing changes in parent sensitivity in telehealth and hybrid implementation of attachment and biobehavioral catch-up during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child Maltreatment, 28(1), 24–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/10775595211072516

- Şenol, F. B., & Üstündağ, A. (2021). The effect of child neglect and abuse information studies on parents’ awareness levels during the COVID-19 pandemic. Children and Youth Services Review, 131, 106271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106271

- Shorey, S., Tan, T. C., Thilagamangai, M., Yu, J., Cy, L. S., Shi, L., Ng, E. D., Chan, Y. H., Law, E., Chee, C., & Chong, Y. S. (2021). Development of a supportive parenting app to improve parent and infant outcomes in the perinatal period: Development study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(12), e27033. https://doi.org/10.2196/27033

- Stevens, E. (2021). Virtual VIPP. Piloting the delivery of VIPP remotely. Paper presented at the online conference of the Society for Emotion regulation and Attachment Studies (SEAS) on Innovations in Attachment-Based Interventions for Pandemic Times, organized by Howard Steele and Xiqiao Chen, December 2-3, 2021.

- Stolk, M. N., Mesman, J., Van Zeijl, J., Alink, L. R. A., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Van IJzendoorn, M. H., Juffer, F., & Koot, H. M. (2008). Early parenting intervention aimed at maternal sensitivity and discipline: A process evaluation. Journal of Community Psychology, 36(6), 780–797. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20280

- Straus, M. A., Hamby, S. L., Finkelhor, D., Moore, D. W., & Runyan, D. (1998). Identification of child maltreatment with the parent- child conflict tactics scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 22(11), 1177–1177.

- Van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. (2020). Problematic cost–utility analysis of interventions for behavior problems in children and adolescents. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2020(172), 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1002/cad.20360

- Van IJzendoorn, M. H., Schuengel, C., Wang, Q., & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. (2022). Improving parenting, child attachment and externalizing behaviors: Meta-analysis of the first 25 randomized controlled trials on the effects of video-feedback intervention to promote positive parenting and sensitive discipline. Development & Psychopathology, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579421001462

- White, D. M., Aufderheide Palk, C., & Gengoux, G. W. (2021). Clinician delivery of virtual pivotal response treatment with children with autism during the COVID-19 pandemic. Social Sciences, 10(11), 414. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10110414

- Whitehouse, A. J. O., Varcin, K. J., Pillar, S., Billingham, W., Alvares, G. A., Barbaro, J., Bent, C. A., Blenkley, D., Boutrus, M., Chee, A., Chetcuti, L., Clark, A., Davidson, E., Dimov, S., Dissanayake, C., Doyle, J., Grant, M., Green, C. C., Harrap, M. … Hudry, K. (2021). Effect of preemptive intervention on developmental outcomes among infants showing early signs of autism: A randomized clinical trial of outcomes to diagnosis. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(11), e213298. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.3298

- Yi, Z., & Dixon, M. R. (2021). Developing and enhancing adherence to a telehealth ABA parent training curriculum for caregivers of children with autism. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 14(1), 58–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-020-00464-5

- Zengin, M., Başoğul, C., & Yayan, E. H. (2021). The effect of online solution-focused support program on parents with high level of anxiety in the COVID-19 pandemic: A randomised controlled study. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 75(12), e14839. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.14839

- Zheng, Y., Wang, W., Zhong, Y., Wu, F., Zhu, Z., Tham, Y., Lamoureux, E., Xiao, L., Zhu, E., Liu, H., Jin, L., Liang, L., Luo, L., He, M., Morgan, I., Congdon, N., & Liu, Y. (2021). A peer-to-peer live-streaming intervention for children during COVID-19 homeschooling to promote physical activity and reduce anxiety and eye strain: Cluster randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(4), e24316. https://doi.org/10.2196/24316