ABSTRACT

Parental support of children’s learning contributes to children’s motivation, efficacy, and academic success. Nonetheless, in the context of homework, many parents struggle to offer adequate academic support and intervene in a manner that can curtail children’s academic progress. A mentalization-based online intervention was proposed for improving parental homework support. The intervention involves teaching parents to dedicate the first 5 minutes of homework preparation to observation of the child’s and the parent’s mental states. Thirty-seven Israeli parents of elementary school children randomly assigned to intervention or waitlist conditions participated in a pilot study assessing the feasibility and initial efficacy of the intervention. Participants completed self-report measures before and after the intervention or a 2-week waiting period and provided feedback on the intervention. Pilot findings suggest that this low-intensity online intervention can be effective in improving parenting practices in the homework supervision context. A randomized controlled trial is required to further establish the intervention’s efficacy.

During elementary school, parents often assist their children with their schoolwork.

Parental academic support is an important source for students’ autonomous motivation for learning, self-regulation, and experience of self-efficacy as learners (Cooper et al., Citation2012; Grolnick et al., Citation1991; Hoover Dempsey et al., Citation2001; Pomerantz et al. (Citation2005a)). Moreover, in many families, parental homework support is an important opportunity for parents to interact with their school-age children (Author, under review). Nonetheless, parental homework assistance often results in the opposite outcomes despite its developmental potential. Several studies showed that both students and parents can become frustrated and stressed from doing homework together (Cooper et al., Citation2012; Katz et al., Citation2012; Pomerantz, Grolnick, et al., Citation2005b, Citation2005a) and that parental homework involvement can harm students’ motivation for learning and their sense of efficacy (Patall et al., Citation2008). The current project aimed to develop and pilot a brief online parenting-based intervention to help parents improve the support they provide their children during homework time. The intervention was based on mentalization theory and focused on changing the structure of parental homework involvement to facilitate parental attunement to the child’s needs.

Despite parents investing time and resources to support their children academically, many parents struggle to offer support matching their child’s cognitive and emotional needs. Studies on parental academic involvement from the past 30 years attempted to identify factors contributing to ineffective parental academic support. A central element is related to negative parental mediation practices, particularly parental control and emotional negativity (Grolnick et al., Citation1997; Pomerantz & Eaton, Citation2001). Parental control in the homework context involves taking over the work and intrusively pressuring children toward specific outcomes, solving children’s problems, excessive monitoring, or checking without child request. Parental negativity is manifest in negative affect (e.g. impatience, hostility), disparaging comments, and dismissing the child’s knowledge and work (Pino‐pasternak, Citation2014; Pomerantz, Grolnick, et al., Citation2005b, Citation2005a). Alarmingly, parental engagement in harmful homework mediation practices is highly prevalent (Cooper et al., Citation2000), and higher involvement frequency is linked to increased parental intrusiveness (Pino‐pasternak, Citation2014).

Previous attempts to improve parental homework support focused on changing parenting practices to decrease control and improve child autonomy support (i.e. Froiland, Citation2011) or decrease homework-related stress (i.e. Moe et al., Citation2020). In the current intervention, our approach focused on the cognitive and emotional processes underlying parental homework support, more specifically the parents’ ability to consider the child’s needs before offering help. We propose that when parents focus their attention on their own and the child’s mind during homework support, their ability to intervene in an attuned and contingent way improves without direct teaching of supporting mediation practices.

We use the term “parental mentalization” or parental reflective functioning to refer to the parental capacity to consider the child’s mind, motivation, cognitive abilities, and emotional state as underlying the child’s behaviors and to the parental ability to create a coherent representation of the child’s internal states (Ordway et al., Citation2014; Slade, Citation2005; Steele & Steele, Citation2008). Parental mentalization also refers to the parent’s ability to consider the child as a mental agent with thoughts, feelings, and motives that may differ from theirs (Fonagy & Target, Citation1997; Luyten et al., Citation2017; Sharp & Fonagy, Citation2008). Multiple studies documented the contribution of parental mentalization to sensitive and contingent parental response and the ability to manage the child’s distress (Camoirano, Citation2017; Rutherford et al., Citation2013; Yatziv, Gueron-Sela, et al., Citation2018; Zeegers et al., Citation2017). Studies conducted with parents of school-age children showed that higher parental mentalization was linked to increased parental support during frustrating tasks and moderated the impact of parental stress and emotion dysregulation on controlling (Borelli et al., Citation2016) and hostile parenting (Gershy & Gray, Citation2020; R. Cohen et al., Citation2022).

Decreased mentalization (or a prementalizing mode) refers to the parental focus on their own experiences or difficulty in considering the child’s behaviors in terms of mental processes. In the context of homework support, parents who consider the child’s mind and think about the child’s behaviors during homework in relation to underlying mental states may respond to the child’s needs in a sensitive and contingent way, respecting and encouraging the child’s competencies and autonomy. On the other hand, parental controlling and coercive behaviors during homework can stem from lower parental mentalization or a temporary loss of parental capacity to consider the child’s mind. Parental prementalizing mode has been associated with biased and hostile parental interpretations of the child’s behaviors and increased parental emotional reactivity, leading to controlling and negative behaviors (Asen & Midgley, Citation2019; Dieleman et al., Citation2020; Luyten et al., Citation2017).

Homework time can be a challenging context for parental mentalization. Homework time often occurs during the afternoon/evening hours when parents are busy attending to other home-related chores (e.g. taking care of siblings, preparing dinner) and therefore may have limited emotional and attentional resources. The distribution of attention over several tasks can challenge parents’ cognitive and emotional availability to perceive and process the child’s cues (H. J. Rutherford et al., Citation2018; Yatziv, Kessler, et al., Citation2018). Moreover, parental homework perception (e.g. the importance of homework for the child’s success, and parents’ experience of their own homework as a child) can create rigid expectations regarding the child’s behaviors and trigger negative emotions during the interaction (Dieleman et al., 2019). Finally, parental role construction (e.g. assuming responsibility for the child’s performance) can increase parental stress over achieving specific outcomes that depend on the child’s performance (Katz et al., Citation2012). These homework-related stressors can reduce parents’ ability to mentalize and attend to the child during the interaction, pay attention, and think openly and curiously about the child’s mental state. A prementalizing mode undermines the ability to respond flexibly to the child and intensifies coercion and control. When mentalization failures occur frequently, parent – child homework interaction can become stressful and dysregulating for the parent and the child (Asen & Midgley, (Citation2019)).

Given the propensity of homework to reduce mentalizing processes, addressing some of the barriers to mentalization described above can facilitate parental ability to think about the child’s mind and improve the quality of parental homework support. In the current project, we developed a brief intervention addressing the challenges of mentalization and increasing opportunities for parental mentalization during homework. Following Asen and Midgley’s ((Citation2019)) mentalization-based approach to working with families, we conceptualized parental mentalization as a dynamic spectrum that responds to external conditions. We assumed that parental mentalization could increase or decrease depending on the presence of opportunities and constraints to mentalize.

Dumas’s (Citation2005) and Duncan’s et al. (Citation2009) work on mindful parenting suggests that parents who can focus their full attention on their child are capable of perceiving their child’s feelings and thoughts more accurately. In the context of parent – infant psychotherapy, the “watch, wait, and wonder” approach of J. Cohen et al. (Citation1999) highlights the transformative role of parental observation of the child’s initiative in creating a reflective stance for the parent and its potential to improve parental sensitivity to the child’s needs. Following these two lines of work, we hypothesized that by asking parents to dedicate the first 5 minutes of homework time to observation of the child, parents could more easily engage in a mentalizing process, and improve their attunement to the child’s abilities and needs.

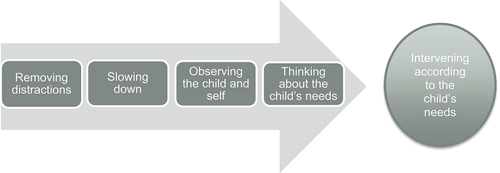

provides an outline of the model. As shown in the figure, facilitating a mentalization process involves several components: (a) Asking parents to refrain from other activities and to focus their attention only on their child. We expected that this step would improve the parent’s mental availability and their ability to assess the child’s mental state. (b) Asking parents to intervene only after dedicating time to observe the child. Separating the observation process from responding was expected to help the parent slow down and regulate emotional interpretations and responses. (c) Asking parents to think about several questions related to their child’s mental state and their own. A guided assessment of the child and the parent’s mental states breaks the process of thinking about the child’s mind into small, easy-to-observe components. It can encourage parental self-reflection in a non-critical fashion. Finally, (d) parents were asked to consider what the child needed and to intervene accordingly. We expected this would encourage an intervention that was sensitive to and contingent on the child’s mental state.

The four components described above represent a stepwise approach to mentalization that encourages parental reflectivity without placing high cognitive and emotional demands on them. Going through the four steps was expected to encourage parents to consider their child’s mental experience as relevant to their homework involvement and choose their intervention in relation to it. This process does not address the content of the parents’ thinking. It relies on the assumption that most parents can improve their mentalization of their child when provided with adequate support (Schechter et al., Citation2006). We assumed that teaching parents to structure their involvement differently and supporting their efforts to apply the new structure would create a mentalizing space during homework and improve parental utilization of their mentalizing capacity, leading to improved child support.

To test the proposed model, we developed a brief online mentalization-based intervention. The intervention was designed for parents of elementary school children. It was planned to fit the unique conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic, to be delivered online, and to address a large range of academic tasks. The changes in the learning conditions caused by the pandemic (i.e. school shut down and the transition to remote learning) made parental homework support an even more central component of children’s learning engagement (Gunzenhauser et al., Citation2021). Parents could use the technique in both remote and in-person learning modalities. We used a pilot sample recruited from the community (to be followed with a larger randomized controlled trial) to test the intervention’s acceptability and feasibility and to tentatively assess the effect on parental mentalization, behavior regulation, and practices. We hypothesized that: 1. Parents would be able to implement the intervention easily and experience it as complementary to their daily practices; 2. Parents in the intervention condition would report increased parental mentalization, warmth and autonomy support, and reduced behavioral reactivity and hostile and controlling parenting practices following the intervention.

Method

Participants

Thirty-seven Israeli parents were recruited from the community and were assigned to either the intervention (n = 21) or the control condition (n = 16). Three families dropped out of the intervention condition due to their inability to practice the observation technique. No families dropped out of the control condition. However, we had to terminate the participation of one family in the control condition due to their refusal to be recorded during the initial and final meetings with the researcher. Inclusion criteria were parents of children who were (1) in elementary school, (2) not attending special education, and (3) parents who assisted their children with homework at least once a week. Thirty-three parents (two fathers, 31 mothers) of first to sixth-grade students (36% girls; M age = 10.27, SD = 1.07) participated in the final sample (18 intervention and 15 control). Family income of 62% of the sample was above the national average (16,518 ILS; Central Bureau of Statistics, Citation2019), and 97% of the parents had completed higher education. Most parents identified as traditional or religious (73%). Of the children, 15% were previously diagnosed with ADHD. All parents gave consent to participate in the study and received monetary compensation.

Procedure

Participating parents were assigned to either intervention or waitlist conditions using a computerized randomization algorithm balanced for the child’s gender and age. The intervention was administered by three graduate-level research assistants from the Clinical and School Psychology program. All meetings with parents were recorded and checked by the first author for protocol adherence. The trial took place as follows (intervention then waitlist).

Intervention

Parents assigned to the intervention group completed Time 1 (T1) measures online.

Parents met with a researcher who administered a short interview regarding the last time parents assisted their child with homework.

Following the interview, parents received an explanation of the observation technique and they were asked to practice the 5-minute observation for 2 weeks using a guided observation form (see supplemental materials for the guided observation form).

By the end of the 2-week practice period, parents completed Time 2 (T2) measures online and met with the researcher for a second interview regarding the last time they assisted their child with homework. Parents were then asked to share their intervention experience.

Waitlist

Parents assigned to the waitlist group completed T1 measures online.

Parents met with a researcher who administered a short interview regarding the last time they assisted their child with homework. We asked parents to continue doing homework as usual for two weeks following the interview.

After the two-week waiting period, parents completed T2 measures online, completed a second interview regarding the last time they assisted their child with homework, and received the intervention.

All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later comparable ethical standards. The Ethics Committee of the Hebrew university approved the study (confirmation number 2021Y0306)

Measures

Parental mentalization. This was assessed at T1 and T2 using two six-item scales from the Hebrew version of the Parental Reflective Functioning Questionnaire (Luyten, Mayes, et al., Citation2017; R. Cohen et al., Citation2022; Shai, Citation2017). The Prementalizing Mode scale assesses a nonmentalizing stance. Items reflect the parental inability to enter the child’s subjective world and the tendency to make maladaptive and negative attributions about the child. A high score on this scale represents mentalization difficulties. The Interest and Curiosity in Mental States scale assesses active parental curiosity and willingness to understand the child’s mental states. A high score represents a higher interest in the child’s mental state. The original questionnaire includes an additional scale- Certainty in the Child’s Mind, that we did not use in the current study due to its non-linear characteristics (i.e. midrange scores are considered an optimal marker of mentalization; Anis et al., Citation2020; Luyten, Nijssens, et al., Citation2017). Internal consistencies in the current study were acceptable (Prementalizing Cronbach’s α T1 = .77, T2 = .65; Interest and Curiosity Cronbach’s α T1 = .65, T2 =.69).

Parental stress. This was assessed at T1 using the translated version of the Parenting Stress Scale (Berry & Jones, Citation1995). The scale consists of 18 items addressing positive and negative aspects of parenting (e.g. parental satisfaction, rewards, stressors, and lack of control). A higher score on the questionnaire represents a higher stress level. Internal consistency in the current study was good (Cronbach’s α = .80).

Parental behavioral regulation during homework. This was assessed at T1 and T2 using six items from the “impulse control difficulties” subscale that was adapted to the homework context (e.g. “When I helped my child with homework, I was able to stop myself and not respond immediately”). The internal consistency of the questionnaire was adequate (Cronbach’s α T1 = .71, T2 = .78).

Parental autonomy support and control. These factors were assessed at T1 and T2 using the Hebrew version of the Perceived Autonomy Support Scale (Mageau et al., Citation2015; translated by Katz et al., Citation2018). The scale consists of 18 items divided into autonomy-supporting scales (e.g. offering choice, providing a rationale for demands and limits, and acknowledging emotions) and controlling scales (e.g. threats to punish, performance pressure, and guilt-inducing criticism). For the current study, we adopted the scale to the homework context (e.g. “I make my child feel guilty when not concentrating or making mistakes while we are doing homework”). The scales’ internal consistencies in the current study were acceptable, (Autonomy support: Cronbach’s α T1 = .76, T2 = .86; Control: Cronbach’s α T1 = .88, T2 = .87).

Negative and positive parental reactions. These factors were assessed in T1 and T2 using two subscales from the Hebrew version of the Multidimensional Assessment of Parenting Scale (Parent & Forehand, Citation2017) adapted to the homework context. The Hostility scale assesses parental harshness and coercive processes such as arguing, yelling, and irritability. The Warmth scale assesses the display of positive emotions (e.g. “During homework, I express affection by hugging and kissing my child”). The scales’ internal consistencies in the current study were adequate (warmth: Cronbach’s α T1 = .72, T2 = .82; hostility Cronbach’s α T1 = .89, T2 = .85).

Parental experience of the intervention. We asked all parents to share their experience implementing the 5-minute observation technique by the end of the intervention. Specifically, we asked parents to describe if there were any challenges to implementation and what they had learned while implementing the technique. We analyzed participants’ responses thematically following Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) procedure in the following order: 1. Answers were transcribed verbatim; 2. Each answer was given a detailed code capturing its main content; 3. Answers with similar/close codes were collated under descriptive themes; 4. A second researcher assessed the goodness of fit of the themes to the original verbatim transcript; and 5. Disagreements were discussed, and final themes were named and described using examples from the transcripts.

Analytic approach

We assessed the questionnaire data for outliers using the Tukey test and evaluated the normality of distribution using the Shapiro – Wilk test. Each identified outlier was assessed for reporting errors, resulting in removing one outlier from the analysis and correcting three outliers using a winsorizing approach (Blaine, Citation2018). The normality test results indicated non-normal distribution of the prementalizing (T1 and T2), control (T1 and T2), and warmth (T2) scales. Both prementalizing and parental control scales were positively skewed, suggesting an overall trend toward the reporting of low parental prementalizing and control. To assess the intervention effect we conducted a series of two-way repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVA) with Time as the within-subject factor and Condition (control versus intervention) as the between-subject factor. Intervention effects were analyzed as the interaction of Condition x Time. Given the multiple testing, we used a Bonferroni adjusted alpha level (.05/7 = .007) for significance. We used robust inferential methods to estimate the significant effect for the non-normal distributed variables. This approach was conducted using the WRS2 package in R (Mair & Wilcox, Citation2020). This package provides p-values based on bootstrapping sample distributions. Due to the small sample of this pilot study, and the associated low power, we used effect size in addition to significance level to describe and interpret the intervention effect. To avoid biased interpretation, we interpreted only effect sizes at the medium/high level.

Results

Of the 21 families in the intervention group, three families did not practice the observation technique during the 2-week practice period due to a busy parental schedule (one family) or the lack of assigned homework (two families). Among the intervention completers, 55% of the parents reported having practiced the observation technique twice with their children, 28% practiced three times, and 17% practiced four times over the 2-week practice period.

Preliminary analyses

A series of t-test comparisons revealed no significant differences between the parents in the intervention and control conditions regarding the initial levels of the parents’ stress, behavioral dysregulation, and parental mentalization. Nonetheless, participants in the control condition reported higher levels of parental warmth (t(31) = 2.24, p = .03). In addition, there were differences in paternal participation (two fathers participated in the intervention condition) and children’s ADHD diagnoses (four in the intervention condition and one in the control condition).

Intervention effects

The changes in the outcome variables across Condition and Time and the results of the repeated measures ANOVAs are presented in and are described below.

Table 1. Means and Standard Deviations of Outcome Variables across Intervention Condition and Time.

Table 2. Results of 2 × 2 Repeated Measures ANOVA of Outcome Variables.

Parent-Reported mentalization of the child

For parental interest in and curiosity about the child’s mind, the results of the repeated measures analysis indicated a non-significant medium effect size for the Time × Condition interaction, F(1, 30) = 2.47, p = .13, η2 = .08. As can be seen in and , an improvement in parent-reported interest and curiosity was indicated only in the intervention condition. Regarding parental prementalizing, the results of the repeated measures analysis indicated a non-significant small effect size for the Time × Condition interaction, F(1, 29) = 1.07, p = .30, p bootstrapped=.73, η2 = .04.

Parental behavioral regulation

The results of the repeated measures analysis indicated a non-significant medium effect size for the Time × Condition interaction on parent-reported behavioral regulation during homework, F(1, 31) = 2.41, p = .13, η2 = .07. As can be seen in and , parent-reported behavioral regulation increased in both the intervention and control groups, with a non-significant trend toward greater improvement in the intervention condition.

Parenting practices during homework

For parental support of the children’s autonomy during homework, the results of the repeated measures analysis indicated a non-significant medium effect size for the Time × Condition interaction, F(1, 31) = 2.24, p = .14, η2 = .06. As can be seen in and , the non-significant trend toward improvement in autonomy support was indicated only in the intervention condition. Regarding controlling parenting practices, the results of the repeated measures analysis indicated a non-significant null effect size for the Time × Condition interaction, F(1, 31) = 0.18, p = .66, p bootstrapped =.58, η2 = .00, and a non-significant medium effect size to Time, suggesting a trend towards reduction in controlling practices in both study conditions.

For parental hostility during homework, a non-significant medium effect size was found for the Time × Condition interaction, F(1, 31) = 3.54, p = .07, η2 = 0.10. As seen in and , a non-significant trend toward decreased parental hostility was indicated only in the intervention condition. Regarding parental warmth during homework, the results of the repeated measures analysis indicated a non-significant small effect size for the Time × Condition interaction, F(1, 31) = 0.75, p = .39, p bootstrapped =.15, η2 = .02, and a non-significant medium effect to Time, suggesting a trend towards reduction in parental warmth in both study conditions.

To summarize, no significant changes were observed across study measures. When assessing effect sizes, we found medium-sized improvements in the intervention condition in interest in and curiosity about the child’s mind, autonomy support, and behavioral regulation, alongside a reduction in parental hostility. Contrary to the hypotheses, there was a medium-sized reduction in parental controlling behaviors and warmth in both study conditions.

Exploratory analysis

To further understand the factors contributing to the absence of benefits from the intervention, we identified a subgroup of families that did not report improvement on at least two outcome measures. Six families in the intervention group were identified. Compared to the rest of the intervention group, this subgroup had higher levels of parenting stress (M = 37.6, SD = 3.2 compared to M = 33.3, SD = 8.0) and prementalizing thinking (M = 1.6, SD = 0.8 compared to M = 1.3, SD = 0.3) at the pretest.

Parental experiences of the intervention

Of the 18 available interviews, 14 parents described the technique as easy to implement and to integrate with their homework routines. Four parents described challenges with implementation. The main challenge described was related to the child’s difficulty with waiting for the end of the observation phase and working independently.

Regarding their learning experiences, five parents described noticing their own mental states more during homework time and realizing the extent to which their mental state influences their children and the interaction quality. The parents mentioned the importance of not feeling stressed, being more patient, and focusing on the child instead of other chores or screens. For example, one parent said, “When I arrive calm, peaceful, and 100% hers and not divided into quarters and eighths, she is much calmer.” Six parents found that the observation technique made them practice what they already knew, thus serving as a reminder to consider their own mental states and offering a practical way to apply it in the homework context.

Nine parents said the observation technique revealed important things about their children. The parents described gaining a clearer understanding of the academic challenges their children struggled with, understanding that their children are more capable of working independently, and realizing the types of support their children needed from them. For example, one mother said, “I realized that when I let him cope independently, I need to be with him.”

Five parents shared insights they developed about the homework process following the intervention. These insights involved an increased appreciation of the meaning of homework time to the relationship with their child and a revised understanding of their roles. For example, one father said, “The intervention freed me [and] increased my awareness that homework is a process and the things he (i.e. the child) will not learn today, he can learn a couple of days later, but my relationship with him is the main thing.“Several parents shared that when they did not rush to offer help, their children could take more responsibility for the homework process and learn to trust themselves.

Discussion

In this pilot study, we assessed the feasibility of and preliminary evidence for a new online intervention with parents designed to improve parental homework support. The study results supported the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention with parents. Our analysis of the outcome measures provided initial support for the intervention’s positive effects on parental mentalization, autonomy support, hostility and behavioral regulation, alongside an unexpected reduction in parental warmth. In the following section, we discuss the results in relation to the intervention’s feasibility and initial efficacy.

Feasibility and acceptability

The pilot study was conducted in the winter of 2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic’s circumstances created much instability in schools and families’ lives that affected the scheduling of homework assignments, household routines, and parents’ availability to engage with a new intervention. Despite these external drawbacks, parents were interested in joining the intervention and described finding it relevant to their challenges in providing homework support. Most parents reported that implementing the 5-min observation was easy to integrate into their routines and was accepted by their children. The parents also reported that the implementation of the 5-min observation required them to come more prepared for homework time and take care in advance of situational conditions that could have prevented them from dedicating their full attention to their children. The few parents who reported challenges with implementation related them to their children’s dependency on their assistance and difficulty with waiting 5 min for their help. These children may have experienced the delay in parental assistance as frustrating and hard to manage. It is also possible that parents concerned about their children’s coping abilities struggled to a greater extent with stepping back and letting their children work independently. This implementation challenge highlights the importance of preparing children for changes in parental behaviors and helping parents apply the observation technique gradually, in a fashion that is attuned to their and their child’s comfort levels.

Efficacy

Although no significant changes were observed across all study measures, the medium effect sizes found for several of the outcome variables provided initial support for the intervention’s potential to positively affect parenting and suggested the need for a larger randomized controlled trial.

Regarding parental mentalization, the medium effect size of the interaction between time and condition suggested that the parents in the intervention condition improved their interest in and curiosity about their children’s minds following the intervention to a greater extent compared to those in the control condition. This increase may suggest that the 5-min observation encouraged the parents to pay attention to their children’s minds and increased parental willingness to think about the mental states underlying children’s behaviors. This is consistent with the theoretical link between observation and a parental reflective stance that J. Cohen et al. (Citation1999) proposed in the “wait, watch, and wonder” technique, suggesting parental curiosity can be honed by providing parents with a structured, everyday opportunity to observe the child.

The increase in parental mentalization was also indicated in the thematic analysis of parental verbal feedback. The parents described increased awareness of the relationship between their own mental state during the mutual homework time, their responses to their children, and the children’s homework behavior. Understanding the transactions between the parents’ and the child’s mental states is considered a pivotal part of parental metallization (Borelli et al., Citation2016; Slade, Citation2005). Parents who are aware of their own mental states are better able to distinguish their own from their children’s mental experiences and to recruit means of self-regulation that contribute to improved sensitive and contingent responses (Suchman et al., Citation2010).

Contrary to our expectations, no significant change was observed in the parental prementalizing mode. This finding may be related to the normative sample characteristics and in particular, to the low frequency of the parents reporting high levels of prementalizing, creating a floor effect for this scale.

Regarding parental behavioral regulation, we found no significant reduction in the intervention condition compared to the control condition. Nonetheless, the effect size of the interaction between time and condition suggested that the parents in the intervention condition improved their behavioral regulation during their interactions to a greater extent compared to the control condition. The request to focus for five minutes on the child may have helped reducing parental cognitive load, and facilitated the ability to slow down and delay automatic reactions toward the child. This reported improvement coincides with the parents’ verbal reports where parents described becoming less easily upset during their interactions.

Regarding parenting practices, although no significant improvement was indicated in the intervention condition compared to the control condition, the medium effect size of the interaction between time and condition suggested that the parents in the intervention condition reported improved support for their children’s autonomy. This improvement could be related to the request from the parent to allow the child to work independently for five minutes. This enabled children to present their independent work to their parents and enabled the parents to learn about their children’s abilities to cope with the task, making the parental response more in line with the child’s abilities. Moreover, the improvement in the parents’ affective regulation described above may have helped the parents modulate automatic negative emotions related to the homework context and reduced direct expressions of frustration and anger and the use of coercive means for controlling their children (Crandall et al., Citation2015; Leerkes et al., Citation2015). The parents’ verbal reports supported this direction, suggesting increased awareness of their children’s areas of independence and changes to parental role perception as supporting rather than monitoring the children’s work. These improvements are in line with previous studies on mentalization-based interventions with younger children that found reductions in intrusive parenting behaviors (Byrne et al., Citation2019; Menashe-Grinberg, Citation2022).

Contrary to our hypotheses, the results indicated a reduction in parental control and in parental warmth in both study conditions. It is possible that the interview conducted at the beginning of the procedure and the study questionnaires raised parental awareness of their behaviors during the homework interaction. This increased awareness possibly contributed to parental attempts to reduce coercive or intrusive behaviors, thus obscuring the possible intervention effect (McCambridge et al., Citation2011). In relation to parental warmth, the questionnaire may have raised participants’ awareness of their actual expression of affection during their homework interactions, leading to more accurate and lower accounts of these behaviors at T2.

In addition to the changes described above, the study results suggested that not all families benefited equally from the intervention. When assessing the differences in the families’ benefits, we identified parenting stress and parental prementalizing as important factors. Parenting stress refers to the parental experience of parenting demands surpassing parents’ personal, social, and financial resources (Deater Deckard, Citation1998). High parenting stress has previously been linked to parental experiences of exhaustion and helplessness and more controlling and nonaccepting parenting practices (Putnick et al., Citation2008). In the context of this intervention, the parents reporting high parenting stress may have experienced the intervention as an additional demand rather than as an opportunity for learning. For these parents, a higher level of support at home may be needed to change the homework time structure and improve parental emotional availability to support the child.

The parents who benefitted to a lesser extent from the intervention were also characterized by higher levels of prementalizing (i.e. a focus on their own experiences or difficulty considering their children’s behaviors in terms of mental processes). For this group of parents, a change in the structure of their interactions and the invitation to think about their children’s minds possibly were not sufficient to support the mentalizing process. For these parents, the holding environment a clinician creates may be required as a first step, enabling them to begin mentalizing about themselves before they can consider their children’s needs (Slade, Citation2007).

Limitations and future directions

This pilot study represents an initial attempt to assess whether an instruction for parents to use structured mentalization during interaction with their child can improve parental homework support. Although the study results supported the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention to parents and provided partial evidence of positive effects on parenting, it is important to consider them in light of several limitations. First, the sample was small, thus lacking sufficient power to detect medium and small effects. Second, the study population was normative and from an average/high socioeconomic status. Therefore, it is hard to discern if the intervention would have been effective to a similar extent with families experiencing financial hardship and/or higher levels of child-related difficulties. Third, the outcome measures were based on parental self-report and their participation in an intervention may have biased their responses. Moreover, the lack of child-related outcomes and follow-up assessment precludes an evaluation of the intervention’s effect on children’s homework engagement and academic progress. A randomized controlled trial with a larger, more diverse population, longer practice phase, collateral parent and child reports and observational measures is needed to establish the intervention’s efficacy.

Conclusion

Parents’ ability to pay attend to children’s needs and signals is essential for contingent and sensitive parenting responses. The current pilot study’s results provide preliminary and partial evidence that by changing the parent – child interaction structure and teaching parents to observe their children before intervening, parents can reduce negative responses during homework support. Moreover, in some cases, these structural changes encouraged parental curiosity regarding the child’s mind and promoted autonomy supporting responses that took the child’s perspective and abilities into account. This study’s results support the argument made by van IJzendoorn et al. (Citation2005) that parents can improve their sensitivity following relatively short interventions that target the parental ability to pay attention to and focus on the child during parent-child interaction. In the current context, the results suggest that a brief mentalization-based intervention that is easy to implement and highly accessible to all parents has the potential to promote a change in the quality of parental homework support.

The study was preregistered at osf.io/3bjfu. The dataset for the proof of concept study is available upon request from the first author.

Contribution statement

NG conceptualized and designed the intervention with the help of RC and NAP. RC led the data collection and data analysis under the supervision of NG. NG wrote the manuscript, and all authors edited several versions of the manuscript. Data is available on request to the first author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participating parents for their willingness to engage with the intervention and share their experiences. We thank Yuval Zonnberg, Yaraa Daeem, Nada Yassin, Daniel Biton, and Natalie Brunstein for their dedicated work with the study families. We would like to thank Professor Nilli Mor, Ph.D. for her thoughtful and professional advise on the study design and observation technique. Thanks to Leon Kaplan for his belief in the project and help to bring it to life.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anis, L., Perez, G., Benzies, K. M., Ewashen, C., Hart, M., & Letourneau, N. (2020). Convergent validity of three measures of reflective function: Parent development interview, parental reflective function questionnaire, and reflective function questionnaire. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 574719. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.574719

- Asen, E., & Midgley, N. (2019). “Working with families.“ In Bateman, A., Fonagy, P. (Eds.). Handbook of Mentalizing in Mental Health Practice, 135–150. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing.

- Berry, J. O., & Jones, W. H. (1995). The parental stress scale: Initial psychometric evidence. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 12(3), 463–472.. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407595123009

- Blaine, B. E. (2018). Winsorizing. In B. Frey (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of educational research, measurement, and evaluation (pp. 1817–1818). SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781506326139

- Borelli, J. L., John, S., K, H., & Cho, E. (2016). Reflective functioning in parents of school-aged children. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 86(1), 24–36. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000141

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Byrne, G., Sleed, M., Midgley, N., Fearon, P., Mein, C., Bateman, A., & Fonagy, P. (2019). Lighthouse Parenting Programme: Description and pilot evaluation of mentalization-based treatment to address child maltreatment. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 24(4), 680–693. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104518807741

- Camoirano, A. (2017). Mentalizing makes parenting work: A review about parental reflective functioning and clinical interventions to improve it. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00014

- Central Bureau of Statistics, (2019). “Household income and expenses, data from the 2017 household expenses survey - general summaries”. Retrieved from https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/publications/DocLib/2019/households17_1755/h_print.pdf

- Cohen, J., Muir, E., Lojkasek, M., Muir, R., Parker, C. J., Barwick, M., & Brown, M. (1999). Watch, wait, and wonder: Testing the effectiveness of a new approach to mother–infant psychotherapy. Infant Mental Health Journal, 20(4), 429–451. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0355(199924)20:4<429:AID-IMHJ5>3.0.CO;2-Q

- Cohen, R., Yassin, N., & Gershy, N. (2022 1-14). Parenting in Israel amid COVID-19: The Protective Role of Mentalization and Emotion Regulation. Adversity and Resilience Science, 3(4), 283–296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42844-022-00072-y

- Cooper, H., Lindsay, J. J., & Nye, B. (2000). Homework in the home: How student, family, and parenting-style differences relate to the homework process. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(4), 464–487. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1036

- Cooper, H., Steenbergen-Hu, S., & Dent, A. L. (2012). Homework. In K. R. Harris, S. Graham, T. Urdan, A. G. Bus, S. Major, & H. L. Swanson (Eds.), APA educational psychology handbook. Application to learning and teaching (Vol. 3, pp. 475–495). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13275-019

- Crandall, A., Deater Deckard, K., & Riley, A. W. (2015). Maternal emotion and cognitive control capacities and parenting: A conceptual framework. Developmental Review, 36, 105–126.

- Deater Deckard, K. (1998). Parenting stress and child adjustment: Some old hypotheses and new questions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 5(3), 314–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.1998.tb00152.x

- Dieleman, L. M., Soenens, B., De Pauw, S. S., Prinzie, P., Vansteenkiste, M., & Luyten, P. (2020). The role of parental reflective functioning in the relation between parents’ self-critical perfectionism and psychologically controlling parenting towards adolescents. Parenting, 20(1), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295192.2019.1642087

- Dumas, J. E. (2005). Mindfulness-based parent training: Strategies to lessen the Grip of automaticity in families with disruptive children. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 34(4), 779–791. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3404_20

- Duncan, L. G., Coatsworth, J. D., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). A Model of Mindful Parenting: Implications for Parent–Child Relationships and Prevention Research. Clinical Child and Family Psychological Review, 12(3), 255–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-009-0046-3

- Fonagy, P., & Target, M. (1997). Attachment and reflective function: Their role in self-organization. Development and Psychopathology, 9(4), 679–700.. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579497001399

- Froiland, J. M. (2011). Parental autonomy support and student learning goals: A preliminary examination of an intrinsic motivation intervention. Child & Youth Care Forum, 40(2), 135–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-010-9126-2

- Gershy, N., & Gray, S. (2020). Parental emotion regulation and mentalization: Buffering roles for coercive and hostile parenting in families of children with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 24(14), 2084–2099. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054718762486

- Grolnick, W. S., Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1997). Internalization within the family: The self-determination theory perspective. In J. Grusec & L. Kuczynski (Eds.), Parenting and children’s internalization of values: A handbook of contemporary theory (pp. 135–161). Wiley.

- Grolnick, W. S., Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (1991). Inner resources for school achievement: Motivational mediators of children’s perceptions of their parents. Journal of Educational Psychology, 83(4), 508.. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.83.4.508

- Gunzenhauser, C., Enke, S., Johann, V. E., Karbach, J., & Saalbach, H. (2021). Parent and Teacher Support of Elementary Students’ Remote Learning During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Germany. AERA Open, 7(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/23328584211065710

- Hoover Dempsey, K. V., Battiato, A. C., Walker, J. M., Reed, R. P., DeJong, J. M., & Jones, K. P. (2001). Parental involvement in homework. Educational Psychologist, 36(3), 195–209. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3603_5

- Katz, I., Buzukashvili, T., & Feingold, L. (2012). Homework stress: Construct validation of a measure. Journal of Experimental Education, 80(4), 405–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2011.610389

- Katz, I., Cohen, R., Green-Cohen, M., & Morsiano-davidpur, S. (2018). Parental support for adolescents’ autonomy while making a first career decision. Learning and IndividualDifferences, 65, 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2018.05.006

- Leerkes, E. M., Supple, A. J., O’brien, M., Calkins, S. D., Haltigan, J. D., Wong, M. S., & Fortuna, K. (2015). Antecedents of maternal sensitivity during distressing tasks: Integrating attachment, social information processing, and psychobiological perspectives. Child Development, 86(1), 94–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12288

- Luyten, P., Mayes, L. C., Nijssens, L., Fonagy, P., & Eapen, V. (2017). The parental reflective functioning questionnaire: Development and preliminary validation. Plos One, 12(5), e0176218. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0176218

- Luyten, P., Nijssens, L., Fonagy, P., & Mayes, L. C. (2017). Parental reflective functioning: Theory, research, and clinical applications. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 70(1), 174–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/00797308.2016.1277901

- Mageau, G. A., Ranger, F., Joussemet, M., Koestner, R., Moreau, E., & Forest, J. (2015). Validation of the perceived parental autonomy support scale (P-PASS). Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue Canadienne des Sciences du Comportement, 47(3), 251.. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039325

- Mair, P., & Wilcox, R. (2020). Robust statistical methods in R using the WRS2 Package. Behavior Research Methods, 52(2), 464–488. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-019-01246-w

- McCambridge, J., Kypri, K., & McCulloch, P. (2011). Can simply answering research questions change behaviour? Systematic review and meta analyses of brief alcohol intervention trials. Plos One, 6(10), e23748. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0023748

- Menashe-Grinberg, A., Shneor, S., Meiri, G., & Atzaba-Poria, N. (2022). Improving the parent– child relationship and child adjustment through parental reflective functioning group intervention. Attachment & Human Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2021.1919159

- Moe, A., Katz, I., Cohen, R., & Alesi, M. (2020). Reducing homework stress by increasing adoption of need-supportive practices: Effects of an intervention with parents. Learning and Individual Differences, 82, 101921.. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2020.101921

- Ordway, M. R., Sadler, L. S., Dixon, J., & Slade, A. (2014). Parental reflective functioning: Analysis and promotion of the concept for pediatric nursing. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 23(23–24), 3490–3500.. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12600

- Parent, J., & Forehand, R. (2017). The Multidimensional Assessment of Parenting Scale (MAPS): Development and psychometric properties. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(8), 2136–2151.. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0741-5

- Patall, E. A., Cooper, H., & Robinson, J. C. (2008). Parent involvement in homework: A research synthesis. Review of Educational Research, 78(4), 1039–1101. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308325185

- Pino‐pasternak, D. (2014). Applying an observational lens to identify parental behaviours associated with children’s homework motivation. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(3), 352–375. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12043

- Pomerantz, E. M., & Eaton, M. M. (2001). Maternal intrusive support in the academic context: Transactional socialization processes. Developmental Psychology, 37(2), 174–186. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.37.2.174

- Pomerantz, E. M., Grolnick, W. S., & Price, C. E. (2005a). The Role of Parents in How Children Approach Achievement: A Dynamic Process Perspective. In A. J. Elliot & C. S. Dweck (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation (pp. 229–278). Guilford Publications.

- Pomerantz, E. M., Wang, Q., & Ng, F. F. Y. (2005b). Mothers’ affect in the homework context: The importance of staying positive. Developmental Psychology, 41(2), 414. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.41.2.414

- Putnick, D. L., Bornstein, M. H., Hendricks, C., Painter, K. M., Suwalsky, J. T., & Collins, W. A. (2008). Parenting stress, perceived parenting behaviors, and adolescent self-concept in European American families. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(5), 752. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013177

- Rutherford, H. J. V., Booth, C. R., Luyten, P., Bridgett, D. J., & Mayes, L. C. (2013). Investigating the association between parental reflective functioning and distress tolerance in motherhood. Infant Behavior & Development, 40, 54–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2015.04.005

- Rutherford, H. J., Byrne, S. P., Crowley, M. J., Bornstein, J., Bridgett, D. J., & Mayes, L. C. (2018). Executive functioning predicts reflective functioning in mothers. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(3), 944–952. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0928-9

- Rutherford, H. J. V., Goldberg, B., Luyten, P., Bridgett, D. J., & Mayes, L. C. (2013). Parental reflective functioning is associated with tolerance of infant distress but not general distress: Evidence for a specific relationship using a simulated baby paradigm. Infant Behavior & Development, 36(4), 635–641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2013.06.008

- Schechter, D. S., Myers, M. M., Brunelli, S. A., Coates, S. W., Zeanah, J. C. H., Davies, M. , Grienenberger, J. F., Marshall, R. D., McCaw, J. E., Kimberly A. Trabka, K. A. , and Liebowitz, M. R. (2006). Traumatized mothers can change their minds about their toddlers: Understanding how a novel use of video feedback supports positive change of maternal attributions. Infant Mental Health Journal, 27(5), 429–447. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.20101

- Shai, D. (2017). Unpublished translation to Hebrew of the Parental Reflective Functioning Questionnaire.

- Sharp, C., & Fonagy, P. (2008). The parent’s capacity to treat the child as a psychological agent: Constructs, measures and implications for developmental psychopathology. Social Development, 17(3), 737–754. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00457.x

- Slade, A. (2005). Parental reflective functioning: An introduction. Attachment & Human Development, 7(3), 269–281.. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730500245906

- Slade, A. (2007). Disorganized mother, disorganized child. The mentalization of affective dysregulation and therapeutic change. In D. Oppenheim & D. F. Goldsmith (Eds.), Attachment theory in clinical work with children, bridging the gap between research and practice (pp. 226–250). Guilford Press.

- Steele, H., & Steele, M. (2008). On the origins of reflective functioning. In F. Busch (Ed.), Psychoanalytic Inquiry Book Series (Vol. 29, pp. 133–158). Analytic Books.

- Suchman, N. E., DeCoste, C., Leigh, D., & Borelli, J. (2010). Reflective functioning in mothers with drug use disorders: Implications for dyadic interactions with infants and toddlers. Attachment & Human Development, 12(6), 567–585.. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2010.501988

- van IJzendoorn, M. H., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & Juffer, F. (2005). Why less is more: From the dodo bird verdict to evidence-based interventions on sensitivity and early attachments. In L. J. Berlin, Y. Ziv, L. Amaya-Jackson, & M. T. Greenberg (Eds.), Enhancing early attachments: Theory, research, intervention, and policy (pp. 297–312). Guilford Press.

- Yatziv, T., Gueron-Sela, N., Meiri, G., Marks, K., & Atzaba-Poria, N. (2018). Maternal mentalization and behavior under stressful contexts: The moderating roles of prematurity and household chaos. Infancy, 23(4), 591–615. https://doi.org/10.1111/infa.12233

- Yatziv, T., Kessler, Y., Atzaba-Poria, N., & Olino, T. M. (2018). What’s going on in my baby’s mind? Mothers’ executive functions contribute to individual differences in maternal mentalization during mother-infant interactions. Plos One, 13(11), e0207869. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0207869

- Zeegers, M. A. J., Colonnesi, C., Stams, G. -J. -J.M., & Meins, E. (2017). Mind matters: A meta-analysis on parental mentalization and sensitivity as predictors of infant–parent attachment. Psychological Bulletin, 143(12), 1245–1272. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000114