Introduction

On February 24, 2022, Russia launched a three-pronged invasion of its southwest neighbor, Ukraine, from the north, east, and south, marking a devastating escalation of the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian conflict. The invasion immediately captured global media attention. Political scientists, such as Maria Repnikova and Wendy Zhou (Citation2022), quickly noted that the Russian side appears to be enjoying official and popular support from China. However, while the Chinese government communicates in vague and ambiguous ways, Chinese social media is more overtly pro-Russian. As a Chinese feminist researcher who closely follows China’s current political climate, I understand the emotionally charged Chinese nationalist appreciation of Russia’s challenges to the coalition led by the United States (US) as both an acknowledgment that China’s only major ally is Russia and that colloquial and provocative posts can be a way to circumvent official censorship and surveillance. However, what strikes me the most is the sexist and racialized nature of my compatriots’ pro-Russian commentaries and even pro-Ukrainian responses, which constantly appear on my personal social media feed.

In order to protect loved ones, I choose not to intervene or engage in these social media conversations that reveal the Chinese masculinist nationalist gaze upon Ukrainian and Russian bodies. Instead, I offer in this Conversations piece only an imagined response, viewing this digital misogyny and racism through a Chinese feminist lens. Specifically, I examine how Chinese social media users jokingly offer to “take in” beautiful, young Ukrainian women, and contestation by social media users over the most “masculine” leader (Volodymyr Zelensky, Vladimir Putin, or Xi Jinping), to explore, first, the intersection of masculinity, nationalism, and race and, second, what I call “distorted dissent.” I also add that I am a cisgender man, and as such, I feel responsible for revealing how Chinese masculinity operates, not only as a way to hold myself accountable but also to be in solidarity with predominantly cis and trans female Chinese feminists who have been mobilizing over decades against all odds.

The intersection of masculinity, nationalism, and race

I became aware of trolling-style posts on Weibo, the Chinese-language equivalent of Twitter, because I follow the Twitter account of a Voice of America (VOA) Chinese American journalist. The journalist captured a selection of these posts and provided English captions for an international audience (). The predatory misogyny that the journalist points out, as well as the lack of empathy toward Ukrainians, is consistent with the overall pro-Russia sentiments in “mainstream” Chinese public opinion. However, the Weibo users are also implicitly mocking the inability of the Ukrainian government and men to protect their female citizens.

Figure 1. A VOA journalist’s tweet exposing Chinese social media users’ sexualization of Ukrainian women.

Translation:Footnote1

User 1: The Ukrainian situation is alarming, but so many people do not care about it at all. This is very disappointing! I would like to use my limited capacity to shelter 2–3 Ukrainian girls, who are between 18 and 25 years old and at least 160 [cm] tall. American imperialists are apathetic, but I am empathic and would like to help as much as I could. World peace #Ukraine

User 2: Accepting heartbroken Ukrainian homeless girls. Food and shelter are provided, and the more the better. Nothing much, [I] just care so much about world affairs.

User 3: #FocusingonthelatestdevelopmentsintheRusso-Ukrainiansituation Accepting Ukrainian single women between 18 and 26 years old.

User 4: Waiting online for heartbroken Ukrainian girls. Most welcome if she is between 18 and 25 years old, 165–175 [cm] tall, has no obvious body odor, and has a good body shape.

User 5: #FocusingonthelatestdevelopmentsintheRusso-Ukrainiansituation Accepting homeless Ukrainian friends, and ladies are first to serve.

![Figure 1. A VOA journalist’s tweet exposing Chinese social media users’ sexualization of Ukrainian women.Translation:Footnote1User 1: The Ukrainian situation is alarming, but so many people do not care about it at all. This is very disappointing! I would like to use my limited capacity to shelter 2–3 Ukrainian girls, who are between 18 and 25 years old and at least 160 [cm] tall. American imperialists are apathetic, but I am empathic and would like to help as much as I could. World peace #UkraineUser 2: Accepting heartbroken Ukrainian homeless girls. Food and shelter are provided, and the more the better. Nothing much, [I] just care so much about world affairs.User 3: #FocusingonthelatestdevelopmentsintheRusso-Ukrainiansituation Accepting Ukrainian single women between 18 and 26 years old.User 4: Waiting online for heartbroken Ukrainian girls. Most welcome if she is between 18 and 25 years old, 165–175 [cm] tall, has no obvious body odor, and has a good body shape.User 5: #FocusingonthelatestdevelopmentsintheRusso-Ukrainiansituation Accepting homeless Ukrainian friends, and ladies are first to serve.](/cms/asset/d9335696-b06f-48b3-b11d-4d6c68d07484/rfjp_a_2082511_f0001_oc.jpg)

Responding to international criticism, official regulators for the platform have since removed these Weibo posts, archived by the VOA journalist using screenshots. However, using “Ukrainian women” as a keyword search, it was not at all difficult for me as an active Weibo user to locate similar posts, with the one in being representative of the politics of the sexualization of Ukrainian women. This commentary was posted on Weibo by a male digital influencer. I suggest that the poster refers to Ukraine as “womb of the world” to emphasize its lucrative industries of surrogacy and escort services. He offers condescending “sympathy” for Ukrainian women in connection with his account of ephemeral encounters with young women from the country to make his concluding claim more convincing to his followers. The poster attributes the “misery” of Ukrainian women to their politicians’ inability to offer strong leadership, thereby emasculating male Ukrainian politicians and possibly Ukrainian men in general.

Figure 2. A male Chinese digital influencer talking about his encounters with Ukrainian women.

Translation:

Fighting has broken out in Ukraine. While worrying for their people, [I] cannot help thinking of something I came across over ten years ago. Back then, I was a teacher at a Shijiazhuang-based military training university. One night, we went out together to celebrate a colleague’s promotion to headquarters. We were unsatisfied with the wine session, so booked a table at the front of a casino club next to our hotel to watch shows. The shows were great and were performed by foreign actresses, who were all blondies with blue eyes. They particularly impressed us with their white, long legs … These Ukrainian girls started traveling around the world for a modest wage about ten years ago. In recent years, [I] heard a lot of stories about Chinese losers moving to Ukraine and marrying white beauties there. The saddest thing is that Ukraine is no longer “womb of Europe” but “womb of the world” … Your people will suffer if you cannot run your country, and that is why I sympathize with Ukrainian women.

![Figure 2. A male Chinese digital influencer talking about his encounters with Ukrainian women.Translation:Fighting has broken out in Ukraine. While worrying for their people, [I] cannot help thinking of something I came across over ten years ago. Back then, I was a teacher at a Shijiazhuang-based military training university. One night, we went out together to celebrate a colleague’s promotion to headquarters. We were unsatisfied with the wine session, so booked a table at the front of a casino club next to our hotel to watch shows. The shows were great and were performed by foreign actresses, who were all blondies with blue eyes. They particularly impressed us with their white, long legs … These Ukrainian girls started traveling around the world for a modest wage about ten years ago. In recent years, [I] heard a lot of stories about Chinese losers moving to Ukraine and marrying white beauties there. The saddest thing is that Ukraine is no longer “womb of Europe” but “womb of the world” … Your people will suffer if you cannot run your country, and that is why I sympathize with Ukrainian women.](/cms/asset/2f0e3765-08fe-49ba-9418-5f976f2629ae/rfjp_a_2082511_f0002_oc.jpg)

It is important to investigate the multiple gendered layers of “sympathy” professed by Chinese men toward Ukrainian women as they reveal how geopolitics is interpreted and shaped by Chinese citizens. Indeed, since the invasion started, I have noticed that this digital influencer has been sharing pro-Russian opinions on Weibo on a daily basis. With over 500 likes received for this single post and 12 million followers accumulated on the platform overall, his gendered assessment of the Russo-Ukrainian crisis is gaining significant traction in the Chinese-language social media sphere.

As a member of the overseas diaspora who mainly uses Chinese-language platforms to stay in touch with friends and family back home, I have been wary of engaging in social media debates outside of the academic context because of the personal consequences that it may entail. However, with my social media feeds being populated by misogynist and nationalist posts since the Russian invasion started, I feel the urge to share my critique with the world as a way to show my solidarity with war crime victims.

Of course, what I have observed should not be a surprise to readers of the International Feminist Journal of Politics. We know that modern nationhood, war, and state identity are principally masculinist projects (Enloe Citation1989; McClintock Citation1993). Indeed, feminist arguments from the late 1980s and early 1990s remain disturbingly relevant, given more recent scholarship on representations of and discourses about female leadership, as well as female citizenry’s endorsement of masculinist nationhood (Schneider and Bos Citation2014; Baxter Citation2017).

In the Chinese context, early nationalist thinkers framed the urgency of modern Chinese nation building around the moral call to “defend our women and children from foreign invaders” (see for example Liang Citation1897; Fan and Mangan Citation2001). Furthermore, the recent rise of nationalism in China is inseparable from the government’s nationalist propaganda and the way in which it has mobilized official media channels and sponsored themed popular cultural production to legitimize the party-state polity at a time when exacerbated social stratification threatens the regime’s legitimacy in the post-reform era (Schneider Citation2018). Amid the revival of Cold War mentalities in both the West and the East, China and Euro-American democracies have drifted away from each other, despite the close trade relations between them. Anti-Westernism has thus emerged as a defining characteristic of China’s current nationalist sentiments (Zhang Citation2022). In this process, Russia has become one of China’s few strategic partners, as it shares a similar desire to challenge Euro-American hegemony in the global geopolitical order.

Intersecting with this anti-Westernism are increasingly overt calls for the preservation of “Chinese racial stock.” While the roots of Chinese “racial purity” are in its historical narrative, which repeatedly highlights “racial differences” as the causes of the ancient Chinese empire’s wars with surrounding countries, ideas about racial stock in contemporary discourse chiefly serve to discriminate against male African immigrants (Cheng Citation2011, 567). Yet, of course, the above-mentioned social media posts reveal a fetishizing of white skin, blonde hair, and blue eyes. Such a seemingly paradoxical phenomenon underscores the racial hierarchy deeply embedded in China’s racialization of world nations, in which whiteness and “typical” Euro-American features are still associated with desirability, despite the country’s ongoing geopolitical frictions with the West (Peng Citation2020). I posit that we can understand this paradox by appreciating that the “desire” is imbued with violence, as the posts depict Ukrainian women as sexually accessible. While I have not yet found evidence on Chinese social media of responses to or comments on the widespread claims about Russian soldiers’ sexual assaults against Ukrainians, the offers to “house” Ukrainian women show how picking “sides” during conflict means condoning sexual assault and discrimination against the “enemy.”

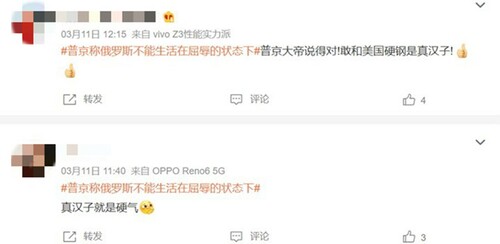

An additional layer in the intersection of masculinity, nationalism, and race is how Chinese social media users idolize other countries’ male leaders as “sexier” and “manlier” than Chinese male leaders. Those other leaders are not white, Western leaders but rather Slavic leaders read as white due to their skin, hair, and eye color as well as aquiline features and double-lidded eyes. Consider that Putin is idolized by both female and male Chinese nationalists (). The hashtag #PutinsaysRussianscannotlivewithhumiliationanymore has become popular slang on Weibo since he launched the invasion of Ukraine. Albeit reappropriated in the Russian context, it echoes similar slogans being used in China’s official propaganda, which constantly reminds its people of the national humiliations caused by past Western and Japanese invasions to galvanize nationalist sentiments.

Figure 3. Two Weibo users calling Putin a “real tough guy.”

Translation of the first post by a male Weibo user:

#PutinsaysRussianscannotlivewithhumiliationanymore Well said, Putin! You are a real tough guy because you dare to fight against America!

Translation of the second post by a female Weibo user:

#PutinsaysRussianscannotlivewithhumiliationanymore This real tough guy is a badass!

Furthermore, by referring to Putin as a “real tough guy,” the posts also point to the association between strong state leadership and hyper-masculinist politicians such as the Russian dictator. Given the total ban on any grassroots discussion about President Xi Jinping on Weibo, Chinese nationalists’ masculinist idolization of the Russian president is often a veiled way of expressing their expectation of China’s leadership, which is made explicit by another Weibo user in . This user rationalizes his vocal support for Putin through an analogy of China and Russia’s respective situations in the current global geopolitical order. Calling for the masculinist leaders of both nations to “eliminate all enemies,” the poster exploits the portrayal of a close friendship between Putin and Xi Jinping in China’s state media (Sohu Citation2018), rendering the former a proxy for his idealized imaginary of the latter. If only Xi Jinping could be like Putin!

Figure 4. A male Weibo user suggesting that Putin is a “real tough guy,” and that China has one too.

Translation:

#TheentirecontentofPutin’s10,000-wordspeech I always support Putin! This is a real man with sophisticated thought, futuristic vision, and personal charisma! [I] feel so excited when reflecting on China’s situation. Is it not the same for China? When did those hegemonic [Western] nations respect us and treat us equally? If there must be a way, I hope it will eliminate all the bad guys and the hegemony they represent. Only this could bring peace on earth.

![Figure 4. A male Weibo user suggesting that Putin is a “real tough guy,” and that China has one too.Translation:#TheentirecontentofPutin’s10,000-wordspeech I always support Putin! This is a real man with sophisticated thought, futuristic vision, and personal charisma! [I] feel so excited when reflecting on China’s situation. Is it not the same for China? When did those hegemonic [Western] nations respect us and treat us equally? If there must be a way, I hope it will eliminate all the bad guys and the hegemony they represent. Only this could bring peace on earth.](/cms/asset/c90bfaa9-1176-46ff-b9bb-ab6eb11a2d6b/rfjp_a_2082511_f0004_oc.jpg)

Pro-Russian commentaries fortify both China’s position in the anti-Western alliance and men’s place in the nation and beyond. This consistent discursive pattern has brought a masculinist interpretation of international geopolitics to the forefront of social media discussions about the current Russo-Ukrainian crisis. A post by a male Weibo digital influencer is a representative example (). The post invokes divorce as a metaphor for Russo-Ukrainian bilateral relations after the collapse of the Soviet Union, and is characterized by its use of colloquial language, adopting phrases such as “flirting” and “winking” to describe Ukraine’s attempt to join NATO. This style distinguishes the post from formal, serious political commentary, so that it is more readily circulated in the social media sphere. Yet, it is precisely the colloquial language that makes its masculinist focus obvious; assigning a male role to Russia to connote its position of strength in the relations, the post feminizes Ukraine as a demonized ex-wife, who has “no independent personality, but only an evil mind” (Repnikova and Zhou Citation2022). Ukraine is not only a scorned woman but also an opportunist, “flirting” its way into the company of other men (NATO). The discourse not only explicitly glorifies a state’s invasion of another sovereign country but also implicitly legitimizes a man’s violence against a woman in an abusive relationship.

Figure 5. A colloquial interpretation of the Russo-Ukrainian crisis widespread on Weibo.

Translation:

Over 20 years ago, Ukraine divorced her ex-husband (Russia) and obtained custody of their children. Her ex-husband treated her well and paid off her debt worth 200 billion! After divorcing her ex-husband, she starts flirting with the big bully in the village (America) and winking her eyes at a bunch of playboys ([other] Western nations). She completely listens to the bully and the playboys and starts abusing her ex-husband together with them … Now the ex-husband is no longer letting it go and starts striking back.

![Figure 5. A colloquial interpretation of the Russo-Ukrainian crisis widespread on Weibo.Translation:Over 20 years ago, Ukraine divorced her ex-husband (Russia) and obtained custody of their children. Her ex-husband treated her well and paid off her debt worth 200 billion! After divorcing her ex-husband, she starts flirting with the big bully in the village (America) and winking her eyes at a bunch of playboys ([other] Western nations). She completely listens to the bully and the playboys and starts abusing her ex-husband together with them … Now the ex-husband is no longer letting it go and starts striking back.](/cms/asset/2b904ea5-2abc-4790-b9e3-9d19c4d56078/rfjp_a_2082511_f0005_oc.jpg)

The original post () has now been shared over 1,000 times on Weibo. Among those Weibo accounts that have shared the post, I discovered a verified one with over 1.8 million followers, operated by a male professor currently chairing the Research Center for International Affairs at a prestigious Chinese university. The university is famous for being the “cradle of government officials” and always aligns itself with state propaganda campaigns.Footnote2 My scrutiny of the professor’s Weibo posting history reveals a mixture of formal academic opinions and informal posts. Those colloquial posts tend to showcase the misogynist aspect of his worldview. The professor’s post on March 8, 2022 – International Women’s Day – is representative (). It reiterates his pro-Russian stance by directly quoting the Russian president’s speech on the festival through a web link, while reveals his sexist perspective by describing women as a “magic potion” who fascinate/seduce men and by encouraging his fellow men to “have more girlfriends.” The professor's post also contains three images. In the first, a female cartoon character looks in the mirror and says “March 8 [women] is a magic potion.” The second image shows women celebrating under the banner of UN Women. The third image depicts female actresses on a stage, with a caption reading “Women are more reliable than men! The hard fact tells us to have more girlfriends!” As a public figure who is influential in the Chinese-language social media sphere, the professor’s sexist posts are evidently tolerated by his university. Considering the 18,000 likes that the original post received, the widespread circulation of such commentary signifies the creation of an echo chamber on Chinese social media platforms that interweaves nationalist politics and masculinist values.

Figure 6. A Weibo post by a male professor “celebrating” International Women’s Day.

Translation:

The charm of International Women’s Day: three times eight equals 24. Happy in all 24 solar terms!Footnote3 Putin’s wishes on March 8 are very special [web link]!

![Figure 6. A Weibo post by a male professor “celebrating” International Women’s Day.Translation:The charm of International Women’s Day: three times eight equals 24. Happy in all 24 solar terms!Footnote3 Putin’s wishes on March 8 are very special [web link]!](/cms/asset/2a950d82-1ce6-4f5b-ad41-21aedc71f8a9/rfjp_a_2082511_f0006_oc.jpg)

This group of social media users’ political ambition is to challenge white men’s hegemony in international geopolitics, but their discourses have paradoxically reinforced a racial hierarchy that associates white male leaders with the quality of distinguished statesmanship.Footnote4 On this note, such a valorization of Putin is consistent with the rise of Donald Trump fandom in China, where a large group of nationalists embrace the crude masculinity that the latter represents in Western right-wing politics (as opposed to “civilized” liberal elitists such as Barack Obama and Joe Biden), despite their antipathy to the former US president’s anti-Chinese rhetoric (Lin Citation2021). This ironic racialization of masculinity reflects the modern evolution of masculinist values in China, whereby the indigenous wen–wu dyad paradigm,Footnote5 and its emphasis on men balancing intellectual/cultural capital and martial valor, is increasingly interpreted as “feminine” and weak (Louie Citation2002). However, these racial logics are not limited to nationalist posts. Racial hierarchies also often surface through “distorted dissent,” in which the masculinities of Zelensky and Xi Jinping are compared and contrasted to push for anti-nationalist agendas in China’s domestic politics, as I discuss in detail below.

Distorted dissent

As I move in and out of social media spaces, I realize that I need to explain one more layer of the Chinese social media response to Russia’s invasion: dissent. Dissent is often romanticized as brave and transformative, but dissident words and actions may be rooted in sexism and racialization; dissent’s radical promise, in other words, may be distorted by oppressive systems. The misogynist posts about “housing” Ukrainian women also constitute dissent, even though the posters are Chinese nationalists mocking Ukrainians, because they draw attention to China’s inability to prevent sexist commentaries. Thus, Chinese officials removed the Weibo posts that explicitly sexualized Ukrainian women. The state-owned and state-sponsored media also jointly condemned such commentaries, after they provoked international criticism, primarily to protect the East Asian superpower’s global image (China News Web Citation2022). State-backed condemnations conveniently invoked nationalist discourses to energize existing anti-Western sentiments among the population.

A typical example of this propaganda strategy can be found in an article authored by Xiying Lei (Citation2022), whose official profile describes him as a standing committee member of the All-China Youth Federation. The article was posted in his capacity as President of the China Cross-Strait Academy, a Hong Kong-registered think tank, which specializes in Mainland–Taiwan relations and has a history of promoting China’s official agendas (China Cross-Strait Academy Citation2021). In this article, he frames any international criticisms of Chinese social media users as plotted by China’s domestic separatists, who are allegedly puppets of the US-led pro-Ukraine coalition, aiming to promote anti-China rhetoric in the global context to destabilize the Chinese state. He puts forward a conspiratorial style of argument to mitigate the negative impacts of Chinese nationalists’ misogynist postings in the eyes of its domestic audiences.

Propaganda campaigns of the kind launched by the China Cross-Strait Academy are not specific to gender politics per se but reveal Beijing’s attempt to reframe anything that could be read as dissenting as an anti-China plot. This enables China to censor social media and inhibit its potential to galvanize dissent against the state while also subtly allowing the masculinist, nationalist rhetoric to continue by scapegoating “real” dissenters and agitators. Thus, dissent can proceed as long as the West’s corrupting influence can be blamed. After all, the state’s strict suppression of domestic grassroots feminist movements reveals that its censorship of misogynist posts has nothing to do with caring about sexism (Liao and Luqiu Citation2022). China’s censorship and surveillance of social media is in reality an attempt to deal with how Chinese citizens are able to share and respond to ideas and commentaries due to the interactive, user-generated-content nature of social media use.

According to the preliminary results from a study conducted by Jennifer Pan, Yingdan Lu, and Anfan Chen, over 50 percent of the sampled 500,000 Weibo posts attribute the cause of the 2022 Russo-Ukrainian war to the US-led coalition or the Ukrainian government, which resonates with Repnikova and Zhou’s (Citation2022) observation of pro-Russian sentiments in “mainstream” Chinese public opinion (Pan Citation2022). However, the research findings also suggest that some 10 percent of the sampled posts primarily blame Russia’s aggression for the crisis, with an additional 15–20 percent either sympathizing with Ukrainians or criticizing both Russia and Ukraine for the escalation of the ongoing conflict. The authors have not yet shared their methodology as to how they identify blame and sympathy, nor have they accounted for gender as a variable. While we cannot presume that gender dictates whether a person is misogynist, nationalist, or anti-Western, it would be interesting to examine whether female and male Chinese social media users have responded differently to the Russian invasion, or the extent to which the sexist comments about “housing” Ukrainians should be coded as pro-Ukraine or pro-Russia.

I tried to find Chinese feminist or other responses to sexist commentaries. An example can be seen in . The post uses a screenshot of international criticisms of Chinese men’s sexualization of Ukrainian women circulated on Twitter, alongside an image of a young Ukrainian woman, to substantiate the poster’s critique of male Chinese misogynists. She suggests that male misogynists do not represent the opinions of the entire Chinese population, because there are women, like herself, who are on the opposing side in the debate. To substantiate this argument, she references a response that she received from a female digital influencer, who argues for the condemnation of the nationalism and misogyny that Chinese men seem to endorse: “Why are you feeling ashamed because of men? Men, rather than women, should be ashamed of what they did. Women should avoid being influenced by nationalist sentiments. After all, your fellow men could sell you out when you sacrifice for the nation.” Based on the screenshot, the female social media user received the response when she approached the digital influencer in an attempt to use the influencer’s platform to voice her personal critique of male misogynists.

Figure 7. A female Chinese social media user calling for a distinction to be made between Chinese women and Chinese men.

Translation:

You must consider Chinese women and men as separate groups when trying to understand them. I am sorry for those Ukrainian women insulted by them [Chinese men].

![Figure 7. A female Chinese social media user calling for a distinction to be made between Chinese women and Chinese men.Translation:You must consider Chinese women and men as separate groups when trying to understand them. I am sorry for those Ukrainian women insulted by them [Chinese men].](/cms/asset/4bbd87e6-5589-4eb7-995d-db732a8df1d6/rfjp_a_2082511_f0007_oc.jpg)

Of the various social media posts that I examined, none tackled the fetishizing of whiteness. To challenge misogyny requires an analysis of how racialization operates in China; dissent is limited otherwise. Indeed, Chinese men have a long history of fantasizing about Ukrainian women as companions, sex objects, and potential brides (Zhou and Ewe Citation2020). Such fantasizing is rooted in the whiteness of Ukrainian women and in Chinese men’s perception of China’s position as a superpower in the making that has boosted their ego and fueled their desire to “conquer foreign women’s bodies.” With a Sino-centric worldview being a defining characteristic of public debates within the country, male Chinese misogynists’ “derogatory language [is] only recognized as damaging when it [is] seen as [increasing anti-Chinese sentiments abroad], rather than seen as offensive and discriminatory toward Ukrainian women.”

Certainly, I am not suggesting that all men participate in misogyny while all women do not. For example, I have witnessed both a female Chinese TikTok user bluntly celebrating the Russian invasion (Ayako2758 Citation2022) and a male Chinese vlogger currently living in Odessa standing up with Ukrainian friends against his pro-Russian compatriots (Buckley Citation2022). Furthermore, I see a trend among pro-Ukrainian posts to emasculate Xi Jinping and valorize Zelensky. Chinese social media users have historically used swear words that insult one’s female family members to protest against the state censorship system. According to Cara Wallis’ (Citation2015) analysis, such lexical choices are informed by the patriarchal values embedded in China’s digital activist traditions. For example, “the little pink” (小粉红) is a degrading feminine label to describe Chinese nationalist citizens (Tao Citation2017) and is often also used by China’s international critics (Jett Citation2021). Those who identify as liberals or dissidents use this misogynist label to mock nationalists for their blind support for the regime; mere alliance with Ukraine and thus dissent against China does not mean the absence of sexism (see also Fang and Repnikova Citation2018; Peng Citation2020).

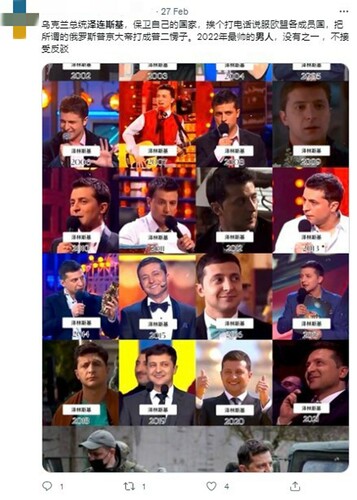

Consider too the reaction to Zelensky’s masculinity, a preferred style of hegemonic masculinity, one that is honed primarily in the Euro-American context and is about protection, a preference for diplomacy but readiness for combat, and performativity as a “civilized” man, as opposed to Putin’s crude masculinity and use of cruel aggression and terror.Footnote6 The commentary shown in was retrieved from the Twitter account of a male Chinese social media user, whose profile describes himself as a “rebel leader” to connote his dissenting identity in the Chinese context. Using expressive rather than neutral language, the tweet voices support for Ukraine by praising Zelensky as one of the greatest in his profession, despite him being a politician in power whose public image is performative by nature.

Figure 8. A male Chinese social media user praising Zelensky on Twitter.

Translation:

Zelensky once played a president role in a comedy. His performance was outstanding, making the show a great success. He was then elected to be President [of Ukraine] and now plays the role of a wartime president. His facial expression, his body language, and the way in which he projects his voice are all perfect. Now, he is not only a legend but also one of the greatest politicians of the twenty-first century!

![Figure 8. A male Chinese social media user praising Zelensky on Twitter.Translation:Zelensky once played a president role in a comedy. His performance was outstanding, making the show a great success. He was then elected to be President [of Ukraine] and now plays the role of a wartime president. His facial expression, his body language, and the way in which he projects his voice are all perfect. Now, he is not only a legend but also one of the greatest politicians of the twenty-first century!](/cms/asset/14fd342a-f7d5-4b43-bece-c0dbc2a9eb7b/rfjp_a_2082511_f0008_ob.jpg)

This excessively positive assessment of Zelensky clearly has support among both female and male Chinese dissidents on Twitter, with the female Twitter user in portraying the Ukrainian president in a similar way to the male Twitter user in . Both users adopt intentionally excessive, fawning language to project a masculinist heroization of Zelensky, much like what we see in Euro-American social media and popular press (Smith and Gant Citation2022). Interestingly, the tweet in is more focused on his appearance. With a series of photographs that capture the facial features of the Ukrainian president, the tweet also participates in racialization, in the sense of its portrayal of a Slavic man read as white, with an aquiline nose, fair skin, and double eyelids, as a desirable male ideal, which is consistent with the changing aesthetics in Chinese society as a result of globalization (Peng Citation2021).

Figure 9. A female Twitter user calling Zelensky the most handsome man of 2022.

Translation:

Ukrainian president Zelensky is fighting to protect his nation. He called all EU member states and has now beaten Putin the Emperor into Putin the Stupid. He is the most handsome man of 2022. There is no second person who deserves this title. Any rebuttal is not accepted.

Circumventing surveillance does not necessarily denote dissent. However, considering the official censorship and monitoring on Chinese-language platforms, a masculinist, emotive description of Zelensky almost always indicates pro-Ukrainian sentiments and defiance of the Chinese government’s official stance. My search on Twitter using the Chinese translation of “Zelensky” (泽连斯基) as the keyword returned volumes of Chinese-language tweets involving a masculinist idolization of the Ukrainian president. In particular, as shown in , this heroization is often juxtaposed with a problematization of the Russian president’s manhood. This not only follows on a dichotomous good/evil narrative of geopolitics but also feeds into the trope of Western/Euro-American hegemonic masculinity being the key marker of being a capable politician.

Considering the anti-nationalist political agenda that dissidents demand in China’s domestic politics, the problematization of the manhood of “Zelensky’s enemies” often alludes to negative assessments of the current leader of their own country, as demonstrated by the tweet in , posted by a self-declared Chinese dissident. The Chinese-language tweet quotes a media interview in which the senior US official Antony Blinken publicly challenges China’s pro-Russian foreign policy during the current crisis. Interpreting the US official’s message as an ultimatum, the tweet specifically calls the masculinity of Xi Jinping into question.

Figure 10. A male Chinese social media user challenging Xi Jinping’s manhood.

Translation:

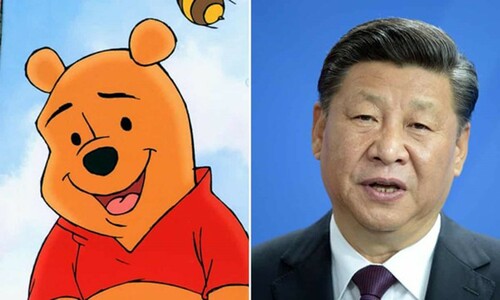

This is an ultimatum to Xi Jinping. Xi Jinping the Pig Head, you now have to do something about it. You cannot hide anymore and must say it out loud if you support Putin the war criminal. Please be a man!

By referring to Xi Jinping as a swine, this tweet is consistent with memes, such as the widely known meme using Winnie the Pooh (), that mock the Chinese leader for being “portly,” which is often interpreted as indicative of his lack of intelligence and sexual attractiveness (Moskowitz Citation2019). In this way, Chinese dissidents’ masculinist idolization of Zelensky is intertextually linked to their problematization of Xi Jinping’s masculinity. Due to their aversion to Putin’s politics, these dissidents simultaneously reject Chinese nationalists’ adoration of Putin and reaffirm the desirability of Western-style hegemonic masculinity. As previously discussed, this phenomenon reflects the long-existing debates over the untenability of China’s indigenous wen–wu masculinity, which is typically associated with the country’s political elite and misperceived as feminine (Louie Citation2002). Thus, we cannot uncritically accept or glorify China’s dissenting voices, given the underlying sexism in their discourses. That dissent is distorted and refracted through the layers of hegemonic masculinity, race, and misogyny that underscore discourses around war and conflict.

Figure 11. An image juxtaposing Winnie the Pooh and Xi Jinping (Haas Citation2018).

Conclusion

Reflecting on my observation of social media discussions about the Russian invasion of Ukraine, what shocked me the most was many male Chinese social media users’ misogynist posts. As a feminist Chinese man trying to engage in solidarity with Chinese feminist theorists and activists, I am most critical of the misogyny of my fellow cisgender men, whose discourses are evidently contributing to the perpetuation of patriarchy and violence. However, my examination simultaneously shows that the real situation is far more complex than a simplistic female-versus-male or a feminist-versus-misogynist paradigm can capture. With colloquial and emotionally expressive styles of language use prevailing in Chinese social media users’ posts, public debates of any kind in the Chinese context provide little room for sensible, evidence-based argumentation. Despite political dissidents’ challenges to the state government and its nationalist politics, their comments on international platforms do not dismantle patriarchy but rather reinforce the value and desirability of certain kinds of normative masculinities (heterosexual, cisgender, performative, swoon-worthy).

This situation calls for urgent feminist intervention. With this aim in mind, I am keen to use my writing to unpack the gender specifics of China’s social issues and their reflection in social media public debates. It is my hope that the above analysis will make a modest contribution to the future democratization of Chinese society by inspiring fellow scholars and activists to continue on this trajectory, whether it is through our critical feminist gaze or a feminist reckoning with Chinese dissent.

Acknowledgments

I wish to express my sincere gratitude to Meghana Nayak, Co-Editor of the International Feminist Journal of Politics’ Conversations section, for her insightful comments on early versions of this piece. It would have been impossible for me to use the journal’s platform to show my solidarity with the victims of Russia’s war crimes without her encouragement and continuous support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Altman Yuzhu Peng

Altman Yuzhu Peng received his PhD from Newcastle University, UK, and is currently Assistant Professor in Intercultural Communication in the Department of Applied Linguistics at the University of Warwick, UK. His research interests lie at the intersections of critical discourse studies, feminism, media and cultural studies, and public relations. He is author of A Feminist Reading of China’s Digital Public Sphere (2020) and has previously published in the Asian Journal of Communication, Convergence, the Chinese Journal of Communication, Feminist Media Studies, the Journal of Gender Studies, Media International Australia, Social Semiotics, and Television and New Media.

Notes

1 All translations from Chinese to English are provided by the author.

2 In China, all prestigious universities are funded by the government and always publicly endorse state policy. This is especially the case for this particular university, which is famous for political sciences and public administration studies and has educated a lot of top officials.

3 The solar term is used in China's traditional calendar to convey seasonal change. A whole year has 24 solar terms. In this sentence, the professor uses the phrase “24 solar terms” as an alternative expression for an entire year to make it sound more memorable.

4 Generally speaking, Chinese people are aware of the crude Russo-centric masculinity that Putin embodies and the cultural differences between Russia and typical Euro-American democracies. However, Russia is simultaneously considered to be part of Euro-American cultures through the lens of race in China because popular Chinese racial discourses largely follow a simplified classification of race as “Yellow” (Chinese/East Asian), “white” (Euro-American), “Brown” (South Asian/Latin American), and “Black” (African). In this coding, ethnically Slavic peoples such as Russians and Ukrainians are considered to be “white.” Barack Obama, while Black, is coded as embodying a style of hegemonic masculinity that is “Western” (Euro-American), as is discussed below.

5 While more complex than I can explain in this paper, wen masculinities are about being “gentlemanly,” culturally competent, and “intellectual,” whereas wu masculinities are about physical skills/prowess and military readiness.

6 While I do not have room to expand on this here, the “Western”/Euro-American-style hegemonic masculinity is in a sense an interesting abstraction and reduction of wen characteristics but is also seen as preferable to balanced wen–wu masculinity. I am also interested in Trump as an aberration from Euro-American hegemonic masculinity and an emulator of Putin’s cruel and brutal style of masculinity.

References

- Ayako2758. 2022. “What’s Chinese Mainland People Look at Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine … ” Twitter, February 26. Accessed May 15, 2022. https://twitter.com/Ayako2758/status/1497455076893655044.

- Baxter, Judith. 2017. Women Leaders and Gender Stereotyping in the UK Press: A Poststructuralist Approach. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Buckley, Chris. 2022. “A Chinese Video Blogger in Odessa Challenges Beijing’s Version of the War.” New York Times, March 15. Accessed May 17, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/15/world/europe/china-blogger-odessa-ukraine-war.html.

- Cheng, Yinghong. 2011. “From Campus Racism to Cyber Racism: Discourse of Race and Chinese Nationalism.” The China Quarterly 207 (September): 561–579.

- China Cross-Strait Academy. 2021. “Chief Executive Xiying Lei’s Bio” [“理事长雷希颖介绍”]. China Cross-Strait Academy. Accessed May 17, 2022. http://ccsa.hk/index.php?m=home&c=View&a=index&aid=80.

- China News Web. 2022. “China News Web Commentary: Please Only Make Sensible Comments on War and Avoid Being a Vulgar Audience” [“中新微: 呼吁对战争理性发言,切勿做低俗看客”]. The Global Times, February 26. Accessed May 17, 2022. https://china.huanqiu.com/article/46yIKxjvIvt.

- Enloe, Cynthia. 1989. Bananas, Beaches, and Bases: Making Feminist Sense of International Politics. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Fan, Hong, and J. A. Mangan. 2001. “A Martyr for Modernity: Qui Jin – Feminist, Warrior and Revolutionary.” The International Journal of the History of Sport 18 (1): 27–54.

- Fang, Kecheng, and Maria Repnikova. 2018. “Demystifying ‘Little Pink’: The Creation and Evolution of a Gendered Label for Nationalistic Activists in China.” New Media & Society 20 (6): 2162–2185.

- Haas, Benjamin. 2018. “China Bans Winnie the Pooh Film after Comparisons to President Xi.” Guardian, August 7. Accessed May 17, 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/aug/07/china-bans-winnie-the-pooh-film-to-stop-comparisons-to-president-xi.

- Jett, Jennifer. 2021. “‘Fragile’: Why a Saccharine Pop Song Has Gotten under China’s Skin.” NBC News, November 12. Accessed May 17, 2022. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/fragile-saccharine-pop-song-gotten-chinas-skin-rcna5057.

- Lei, Xiying. 2022. “Taiwan and Xinjiang Separatists behind the ‘Incident of Ukraine-Related Vulgar Commentary’” [“台湾及疆独势力煽动"涉乌克兰恶俗言论"事件”]. China Cross-Strait Academy, February 27. Accessed May 17, 2022. http://ccsa.hk/index.php?m=home&c=View&a=index&aid=524.

- Liang, Qichao. 1897. “On Education for Women [“论女学”].” The Chinese Progresses 23 (12 April): 1a–4a.

- Liao, Sara, and Luwei Rose Luqiu. 2022. “#MeToo in China: The Dynamic of Digital Activism against Sexual Assault and Harassment in Higher Education.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 47 (3): 741–764.

- Lin, Yao. 2021. “Beaconism and the Trumpian Metamorphosis of Chinese Liberal Intellectuals.” Journal of Contemporary China 30 (127): 85–101.

- Louie, Kam. 2002. Theorising Chinese Masculinity: Society and Gender in China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- McClintock, Anne. 1993. “Family Feuds: Gender, Nationalism, and the Family.” Feminist Review 44 (1): 61–80.

- Moskowitz, Marc L. 2019. Internet Video Culture in China: YouTube, Youku, and the Space in Between. London: Routledge.

- Pan, Jennifer. 2022. “But Not All Hold This View … ” Twitter, March 14. Accessed May 15, 2022. https://twitter.com/jenjpan/status/1503367296940531712.

- Peng, Altman Yuzhu. 2020. A Feminist Reading of China’s Digital Public Sphere. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Peng, Altman Yuzhu. 2021. “A Techno-Feminist Analysis of Beauty App Development in China’s High-Tech Industry.” Journal of Gender Studies 30 (5): 596–608.

- Repnikova, Maria, and Wendy Zhou. 2022. “What China’s Social Media Is Saying about Ukraine.” The Atlantic, March 11. Accessed May 17, 2022. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2022/03/china-xi-ukraine-war-america/627028/.

- Schneider, Florian. 2018. China’s Digital Nationalism. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Schneider, Monica C., and Angela L. Bos. 2014. “Measuring Stereotypes of Female Politicians.” Political Psychology 35 (2): 245–266.

- Smith, Tita, and James Gant. 2022. “Hotter than Trudeau! Ukrainian President’s Defiant Heroics and Combat Gear Photos Defending Kyiv Turn Him into an Unlikely Sex Symbol.” Mail Online, February 27. Accessed May 17, 2022. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-10556123/Fans-swoon-Ukraine-President-Volodymyr-Zelenskyy-fights-Russian-invasion.html.

- Sohu. 2018. “Xi Jinping: ‘Putin Is My Best Friend Who Really Understands Me’” [“习近平: ‘普京总统是我最好的知心朋友’”]. Sohu, June 9. Accessed May 17, 2022. https://www.sohu.com/a/234755104_115479.

- Tao, Anthony. 2017. “China’s ‘Little Pink’ Are Not Who You Think.” SupChina, November 15. Accessed May 17, 2022. https://supchina.com/2017/11/15/chinas-little-pink-are-not-who-you-think/.

- Wallis, Cara. 2015. “Gender and China’s Online Censorship Protest Culture.” Feminist Media Studies 15 (2): 223–238.

- Zhang, Chenchen. 2022. “Contested Disaster Nationalism in the Digital Age: Emotional Registers and Geopolitical Imaginaries in COVID-19 Narratives on Chinese Social Media.” Review of International Studies 48 (2): 219–242.

- Zhou, Viola, and Koh Ewe. 2020. “The Chinese Obsession with Ukrainian Wives.” Vice, March 4. Accessed May 17, 2022. https://www.vice.com/en/article/7kbmva/chinese-obsession-ukrainian-women-russia-invasion.