ABSTRACT

In this article we present and outline depth-hermeneutics as a new application of a theoretically founded psychosocial approach, with the ambition of inspiring teachers to explore challenging aspects of their relational work with students. Empirical knowledge and psychodynamic theory suggest that teaching and learning are profoundly rooted in relationship based processes. Hence it is a prerequisite for improving learning and supporting teachers’ professional development that challenging aspects in the student-teacher relationship be taken seriously by being examined, with the aim of enabling and supporting learning from experience in reflective practice. We suggest that group-based depth-hermeneutics, a qualitative psychosocial method, may allow for analysis and interpretation of situations and relations in school that may be experienced by teachers as difficult or incomprehensible. Drawing on an empirical example from fieldwork in a Norwegian middle school, we illustrate the nature of a challenging situation and relation in teaching and show step-by-step how depth-hermeneutics can be adapted, adopted, implemented, and facilitated in teacher groups, to increase scenic understanding of such complex phenomena.

Introduction

There is a plethora of models for teachers’ professional development (Avalos, Citation2011). In this article we present depth-hermeneutics as a theoretically founded approach to ‘reflective practice’ (Adamowich, Kumsa, Rego, Stoddart, & Vito, Citation2014; Schön, Citation1983; Thompson & Pascal, Citation2011), already an established concept in teaching. According to Loughran (Citation2002, p. 33), the concept’s seductive ‘allure’ is that it appears universally ‘useful and informing’ to think about what one is doing, but that the core of its usefulness lies in its potential to go beyond the common sense level of thought. Williams (Citation2013, p. 75) asserts how group reflective practice may offer ‘a powerful explanation of the situated nature of seemingly individualized thinking, learning and knowing’. Depth-hermeneutics bears promise in this regard, as it engages a group to critically analyse a text, with the aim of generating a wide understanding (Salling Olesen, Citation2016) of its psychosocial dynamics.

Our approach is based on the assumption that teaching and learning involve complex relationships, mediated by a societal-cultural context, which necessitate teachers’ ongoing curiosity towards, and probing of, their situated practice. As researchers, we have experienced how qualitative methods hold ‘a considerable potential for the discovery of processes and problems of professional practice’ for practitioners (Dausien, Hanses, Inowlocki, & Riemann, Citation2008, para 4). Hence, we propose a qualitative psychosocial approach, operationalized through lay-application of depth-hermeneutics, as a means to encourage reflective practice and learning from experience (Bion, Citation1962) for teachers. The second author has carried out explorative but unpublished work using this method as a teacher-educator with 12 groups in Danish higher education (students in teacher education and experienced teachers pursuing a further education MA). The third author has employed a related approach in practice teaching with students in nursing and social work (Froggett, Ramvi, & Davies, Citation2014). The application of depth-hermeneutics for teachers has, however, to the best of our knowledge, not yet been presented in a scholarly journal.

The psychosocial approach is inspired by our experiences as members of the International Research Group for Psycho-Societal Analysis, where we interpret empirical data extracts in groups (Hollway & Volmerg, Citation2010). This practice has its roots in the, mainly, German tradition for depth-hermeneutics – a ‘critical cultural analysis with a psychoanalytic orientation’ (Krüger, Citation2017, p.47) – developed by the German sociologist and psychoanalyst Alfred Lorenzer (Citation1922–2002), who attempted to extend ‘historical-materialist thinking to the psychodynamics of intersubjective relations’ (Krüger, Citation2017; p.47 see also; Leithäuser, Citation2013; Nagbøl, Citation2002). The core concern in depth-hermeneutics is to study unconscious aspects of texts in order to ‘lift out societally repressed meanings and point to their potential as radical imaginations of alternative realities’ (Salling Olesen, Citation2017, p. 35, our translation).

In what follows we start by drawing out teaching as intrinsically relationship-based work implicated in societal discourse, suggesting how performance culture can be a negative influence on conditions for professional development. We then present the methodological moorings of depth-hermeneutics, before providing its step-by-step outline, including suggestions for how texts can be generated for analysis and how group interpretation may proceed and be facilitated for teachers. We illustrate by taking a teacher’s narrative through four phases of interpretation, using our theoretical lenses to generate understandings. We end on a discussion of competencies required to facilitate and carry through such a depth-hermeneutic inquiry.

Relationships and learning in performance schools

Teaching and learning take place in relations between teachers and students (Isenbarger & Zembylas, Citation2006; Näring, Vlerick, & Van de Ven, Citation2012; Ramvi, Citation2010). One review indicates the teacher’s role and relational competence as the single most important factor for students’ learning progress (Nordenbo, Larsen, Tiftikci, Wendt, & Østergaard, Citation2008), suggesting that a key to understanding learning can be found within ‘the learning relationship’ (Youell, Citation2006). As relational workers, teachers undertake considerable emotion work – and management (Hochschild, Citation1979). To elaborate on this, we draw on fieldwork in a Norwegian middle school (Ramvi, Citation2010, Citation2017), where teachers claimed that their relationships with students were ‘alpha and omega’ with regard to being a good teacher and achieving learning – a finding recently confirmed by Klinge (Citation2016). Teachers experienced their professional role as something deeply personal and had strong desires for affirmation in teacher-student relationships; self-esteem became attached to the quality of their relationships with students (Ramvi, Citation2010). Such attention to quality is considered essential to being able to carry out, and carry on in, relationally intensive work (Laursen, Citation2006; Moos, Krejsler, & Laursen, Citation2004), but what are the conditions for reflecting on relational quality in educational practice?

Froggett (Citation2002) observes how the introduction of performance systems in the public sector resulted in tensions between professional and managerial power and an instrumentalisation of organisational cultures, as market-oriented restructuring saturated public services. With a ‘global educational architecture’ permeated by such neoliberal policy (Stray & Voreland, Citation2017, p.87), educational practices have been widely transformed. Allocation of resources in schools may result from performance assessments, like monitoring of exam results, with sanctions against schools and individual teachers who fail to meet targets. When performance is perpetuated, an attitude of competition is imposed on educational institutions. Hoggett (Citation2017, p.4) refers to ‘a growing body of research literature on the impact of performative organizational regimes’ which ‘emphasizes the links between performativity, continuous improvement and the self’. This can readily be observed in schools, where assessment and inspection stir up ‘internal dynamics’ (Youell, Citation2006, p. 4) for staff, as well as students.

While the performance school accentuates excellence, it may also create an atmosphere that disregards quality in teachers’ relational work by denigrating basic feelings of frustration, inadequacy, helplessness, weakness, or ignorance – which arise in any significant relationship. Teachers may, accordingly, protect themselves against relations rather than try to develop tolerance to uncertainty that exists within the relations, thereby ‘turning a blind eye’ to relationships’ (Ramvi, Citation2017, p. 140). This is alarming, because whereas a good teacher-student relationship may promote learning (Klinge, Citation2016) and protect mental health (Krane, Karlsson, Ness, & Kim, Citation2016), negative impacts result from poor relationships. Counteracting detrimental consequences of ‘blindness’ to relations requires the enabling of teachers to ‘think from experience with concepts which can help them think about experience’ (Froggett, Ramvi et al., Citation2014, p.3). We believe that interventions are needed to counterbalance the negative consequences of performance culture and suggest that teachers embrace new modes of critical reflective practice sensitive to the societal changes that they are shaped by, and that they themselves contribute to shaping through their work, which reproduces societal norms. A psychosocial approach may allow for investigation of simultaneous and mutual interplays between the intra- and intersubjective, cultural and societal – and to examine how these dimensions affect and effect teaching in good and bad ways.

A psychosocial approach

Psychosocial approachesFootnote1 often share an understanding of subjectivity informed by psychoanalysis. A founding psychoanalytic assumption is that not everything we say and do is entirely conscious or rational (Freud, Citation1915), and that disciplining aspects of civilization compromise basic instinctual drives, leading to unconscious repression (Freud, Citation1920–1922). As a psychosocial method, depth-hermeneutics aims to go beyond the immediate level of meaning in a text by investigating its latent ‘schemes of life that have been excluded from societal consensus’ (Krüger, Citationforthcoming), seeking to ‘re-integrate’ human experience as embodied, individual, unconscious, relational and social (Bereswill, Morgenroth, & Redman, Citation2010; Gripsrud, Ramvi, Froggett, Hellstrand & Manley, Citation2018; Salling Olesen & Weber, Citation2012).

Lorenzer theorises early infantile development as involving a primary capacity to experience the world as an embodied interconnection of and with ‘scenes’ (Nagbøl, Citation2002). These scenes precede language-acquisition and differentiation between objects, and are the ‘fundamental units of lived experience […and] the most formative ways of people relating to one another’, which are ‘established from the earliest interactions between infant and mother/caregiver’ and socio-culturally mediated by the latter’s role as an agent of society (Krüger, Citation2017, p.50). The ‘Lorenzerian scene’ refers to the characteristic qualities of imagination, which, through its infantile origins, is fundamentally ‘scenic in its format: it interrelates all informative, sensual and situated impressions in holistic images’ (Salling Olesen, Citation2012, para 3). Theoretically laden, ‘the scenic’ could be understood as a metaphor for the stage of a theatre, where a play invites emotional identifications (Froggett, Conroy, Manley, & Roy, Citation2014). The scene, with its condensed ‘matrix of setting, characters, actions, talk and relational encounters’ (Hollway, Citation2015, p.124), can be accessed by the ‘audience’ through the individual’s biographical experience, and imaginary interaction with common sociocultural references. Through the reflexive design of depth-hermeneutic inquiry it is possible to bring this scene to life, as an affective and embodied register of psychosocial meaning that we can recognise and relate to.

In the following, we illustrate how this can be done through a procedure for interpretation of a text emerging from teaching praxis. Adapting depth-hermeneutics to a practitioner context may be audacious but we believe that such a move is congruent with Lorenzer’s vision of transferring the method of psychoanalysis (hermeneutic interpretation) into interdisciplinary lay analysis (see Frosh, Citation2010), which inspired Lorenzer’s development of depth-hermeneutics as psychoanalytic cultural analysis (Rothe, Krüger, & Rosengart, Citationforthcoming). We do, however, recognise that its implementation in teachers’ reflective practice is likely to yield more fruitful results with appropriate facilitation (see p. 19).

A step-by-step outline of the depth-hermeneutic method

Preparation

We suggest that depth-hermeneutics is tried out in groups of four–six teachers, with one facilitator to guide the process and provide emotional ‘containment’ (Bion, Citation1970). The facilitator’s task is to ensure that group’s dynamics do not veer off in an unproductive (say competitive, aggressive) manner, and that the text owner, who may be exposing vulnerability by sharing personal experiences, feels accommodated. Another task is to guide the group towards unveiling latent content, seeking to generate understanding beyond the common-sense level through interpretation.

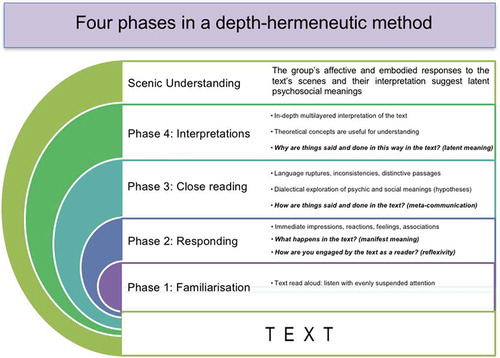

Before work can begin a member of the group should be delegated the task of writing a short text (one–three pages). This could be an observation from the classroom, excerpts from a logbook, a conversation with a student, colleague or manager, or a short personal narrative on the topic of a challenging school situation. A timeframe for the session should be determined – we suggest setting aside one and a half hours. The facilitator ensures that the agreed timeframe is observed, maintaining progress through the interpretation, informing the group about what the respective phases entail. We employ a teacher’s narrative as an example of what such a text could look like. This narrative emerged during fieldwork in a Norwegian middle school (Ramvi, Citation2010, Citation2017). We take this text through four analytic phases (see ) in order to illustrate the process (different approaches exist, see Bereswill et al., Citation2010; Hollway & Volmerg, Citation2010; Salling Olesen & Weber, Citation2012). Key tasks or questions (italicised) are pursued by the group through phases 2–4 with the aim of hermeneutically bringing together meanings in the interpretation.

Figure 1. Four phases in a depth-hermeneutic method. The figure provides an accessible schematic overview of the four phases we suggest to depth-hermeneutic text interpretation and scenic understanding, drawing on Hollway and Volmerg (Citation2010), Bereswill, Morgeroth and Redman (Citation2010) and Salling Olesen and Weber (Citation2012).

Phase one: familiarisation with the text

In this phase (see ) the text is read aloud in the group. The participant who brought it in (the text owner) remains silent as the text is read out and throughout the session until the final phase. In this way, the text owner has the privilege to take notes from the group’s emerging comments, reactions and interpretations – entering the role of an observer as opposed to veering towards a position of authority, defending or explaining particular comments, events or actions. If the excerpt involves two or more characters, different members of the group read these out. Kristin is the narrator in our text example. Recently graduated, she has a strong wish to sustain her ideal of being a good teacher, but then experiences a situation where she feels that she fails as a teacher. She vividly recalls this episode, when she became uncontrollably angry with a student named Ole:Footnote2

The student had irritated several teachers for a long time. We’d get complaints from other teachers; he goes into other classrooms and throws paper around, trips people up, says nasty things. One day Ole left the classroom to join a group project, having neither asked for nor received permission to leave. In the hall many students were gathered, and there was a lot of noise. After a few minutes, I went out and asked everyone in my class to go back into the classroom. “My God, do you see how she keeps going on?” Ole said. I said, “In the classroom it‘s quiet and here in the hall it’s noisy. Usually, if you go out in the hall, it’s because it is quiet, but it isn’t now”. Then he said something very bad, and then he said, “It’s obvious you don’t like me”. I responded, “Do you know what?” He stood in front of me, and all the students in the A and B classes were standing behind me. I got so angry that I said, “Now I’m fed up with you. I’m sorry to say it, but I can’t stand you. You behave so… I’ve never experienced this before”, I said. “That so much filth can come out of that mouth of yours, I don’t understand!” I spoke so loudly that the students heard me through the vents in the classroom wall. I don’t remember word for word what I said, but they came like beads on a string. At any rate I was so stupid as to say that there were “complaints from your class and from the parallel class, and they talk about you in the teachers’ room, about what filthy words you use. I’m never going to give in, I’m going to give you bad marks all the time, because I won’t accept that kind of behaviour, never!” While I’m talking, he stands there, glancing at the ceiling and rolling his eyes. “Yes, yes, sorry, sorry”. He tries to grasp the door handle to go in, but I stop him and say, “I’m not finished with you”. Then I continue on the same key, scolding and scolding: “Look at me when I’m talking to you”, I said. It was now completely quiet in the hall. I felt the blood throbbing in my head, I was so angry. Afterwards, they went into the classroom. There were l0 minutes left. Ole sat still and I continued my rounds among the students. (in Ramvi, Citation2010).

At its heart depth-hermeneutics concerns how a text speaks to and works on – and transforms – the reader consciously and unconsciously (Rothe et al., Citationforthcoming). Hence, participants should start by tuning in to the text’s emergent themes with evenly suspended attention, noting how it is read out and letting it play in the imagination.

Phase two: first responses to the text

What happens in this text in a basic sense? and

How are you engaged in or provoked by the text?

After the recitation participants (except the text owner) take rounds to express spontaneous reactions. Attention is directed toward how the text touches, provokes or plays with the reading self (Bereswill et al., Citation2010). This phase (see ) is characterized by free association. Participants should hold back on argumentative discussion and focus on emotional responses to the text. The central task is to express participants’ immediate and reflexive ways of relating to the material, for instance: ‘my experience is… “, ”I come to think of…’, ‘this makes me feel sad…’, ‘I find it ironic that…’ or ‘it annoys me that…’. Which experiences, scenarios, thoughts and discourses are socially recognizable in the group, having read out the text? Gradually, the group begins to dwell on manifest themes and builds an immediate, common sense overview of the text.

To exemplify, we note that at first impression our narrative concerns a teacher’s reaction to a ‘classic scenario’ involving disruptive student behaviour. Ole challenges Kristin’s authority, to which she responds with loud scolding. This is a common sense level of meaning (key question 1), to which we may add feelings evoked by the text (key question 2). In the narrative’s visual scenery, Kristin was facing Ole with the other students behind her, as an audience. We now come into touch with the vulnerable feeling of being exposed, alone and excluded by a group of others – or the feeling of being in the classroom as a voyeuristic witness to a drama unfolding, or the frustration at being unable to relate to the other, running out of patience.

Phase three: close reading the text

Key question: how are things said and done in the text?

During this phase (see ) the group starts to work line-by-line in a detailed analysis of meta-communicative aspects: specific vocabulary, emphasis, tone, ruptures, repetitions, puzzling statements, emotional outbursts (laughter, shouting, crying), and irony/sarcasm. Positions in relation to the text are likely to be taken up differently by participants, opening up for multiple perspectives in the interpretation. The facilitator should allow these perspectives to co-exist, resisting urges to create one coherent interpretation. The group discusses what is at stake in the text, how this is expressed and how each participant is affected by the material. Working hypotheses may be pursued, or abandoned if they fail to gain support in the group’s continued interpretation of the text.

To exemplify, we hypothesise that there is a gender dynamic in Kristin’s outburst, as she reacts not only to Ole’s behaviour but specifically mentions his ‘filthy words’. The exact expletives remain inarticulate leading us to speculate whether Ole said something sexually explicit or derogatory that she censors in her story. Another hypothesis involves how Kristin belittles Ole, but ends up ‘losing it’ and thereby humiliates herself. Ole’s transgressions are echoed by Kristin’s transgression of moral conduct as a teacher in a societal context where reticence is favoured over expressiveness. We also recall how Kristin said to Ole ‘I am not finished with you’, indicating how both her loss of control and loss of authority may be restored if Ole can comply with her as an authority, which paradoxically is the authority she simultaneously exerts through her imposing statement. We could also point in the direction of Kristin’s sense of impotence and a need to relieve herself of this intolerable feeling: perhaps it is her emotional self she is ‘not finished with’. The outburst could thus be seen as coming from the repudiated self she does not want anyone to see. When reading line-by-line we see how Kristin said three interrelated things: 1) ‘I’m fed up with you’, 2) ‘I’m never going to give in’, 3) ‘I’m not finished with you’. If Kristin desires to be a good teacher, strong anxiety could be linked to not being able to control herself, or not being able to solve interpersonal conflicts. We speculate that Kristin rejects Ole but ambivalently wants to hold onto him too.

Phase four: establishing scenic understanding

Key question: why are things said and done in this way in the text?

In this final phase (see ), the aim is to establish scenic understanding of the text. Aided by the facilitator, the group begins to build a conceptual framing for the different components generated through phases one–three, while keeping in mind that there may be aspects of the analysis for which there is no concept or that members are not aware of. It does so by moving through the previous phases, building a comprehensive, multi-layered interpretation, drawing on manifest and latent meanings. Different conclusions may be drawn but these should open for new perspectives in recognition of the fact that there is always much one does not yet know.

We return to our example, pulling together layers of Kristin’s story. As an individual Kristin does not know why she lost control, but when her authority is undermined by Ole she blows out. She said she was ‘not finished with’ Ole, which suggests that she is unable to settle diffuse feelings triggered in this situation. Her immediate response is to turn Ole into the problem: a projection of unbearable feelings. For her, Ole constitutes the problem because she is not able to recognize these uncomfortable feelings in herself, nor her felt inadequacy in relation to handling his behaviour. Kristin’s intense frustration with Ole is exacerbated by his ‘filthy words’ and generally unappreciative attitude to teachers. She feels unable to connect with Ole emotionally. Kristin’s anger has been disavowed over time due to her strong internal ideal of being a good teacher – someone who prides herself on connecting with students. When pooled up frustrations suddenly erupt, words (she cannot remember them, suggesting an altercated mind) come out of her mouth like projectile ‘beads on a string’. Ole had ‘irritated several of the teachers for a long time’. Hence, socially, Kristin’s ‘retaliation’ functions as a collective expression of despise against Ole: the teachers are all frustrated and fed up with him. Ole’s ‘troublemaking’ appears not to have been addressed at the collegial level other than as a recurring complaint. The institutional failure to deal with a challenging student may have contributed to Kristin’s despair.

With crucial bearing for our interpretation, Krüger (Citation2017, p. 51) notes how ‘[c]onflicts arising at the subjective level might […] be subjectively suffered, but are always produced in relation with others and therefore never without a sociocultural dimension or free from the contradictions of society at large’. We therefore expand the interpretation ‘psychosocially’ and ask: could Kristin’s personal story be seen as representative of a wider societal dynamic? Depth-hermeneutically we would pursue not only the question of ‘how did this conflict arise in this individual?’ but we would ask about a social typology, i.e. ‘what sort of conflict is this?’ (Leithäuser, Citation2013, para 40). This question invites an interpretation of Kristin’s narrative as ‘a typical scene’ (Leithäuser, Citation2013, para 38). In phase three we touched on gender. Perhaps Kristin’s strong sense of a professional ideal could have mobilised (in herself and in Ole) unconscious longings for a good relationship, implicit in sociocultural ideas, norms and fantasies of mothering, which frequently affect the practice of relation workers (Ramvi & Davies, Citation2010). Thus, the confrontation may have arisen due to mutually unfulfilled and disappointed needs, wishes and desires related to societally gendered dimensions of their roles and relationship, involving a ‘naughty boy’ and a ‘kind female teacher (mother)’.

Another key to interpreting this as a ‘typical scene’ could be found by bringing in a tension in the changing historical role of teachers, who used to be seen as distant and punitive authoritarian figures but who, in the current societal context, are more likely to be seen as ‘highly motivated, benign, facilitating […] professionals’ (Youell, Citation2006, p. 4). As Kristin’s narrative reveals, a conflict between student and teacher will inevitably be affected by power dynamics, despite the introjections or projections of gender or contemporary professional ideals. The repression of a teacher’s negative feelings (Kristin’s frustration) could be a product of a romanticising societal ideal of the teacher which ‘demonises’ difficult emotions in learning relations as ‘failure’ to be and do good. According to Hochschild (Citation1979), emotional interchanges are ideologically conditioned by ‘feeling rules’, in turn connected to social structures. An angry outburst is unusual in Kristin’s institutional and cultural context – not unlike the British, Norwegians tend to ‘keep calm and carry on’. In this context, ‘feeling out of control’ relates Kristin’s shame in having breached ‘feeling rules’ and revealed herself as an ‘angry tyrant’. When her voice emitted from the school hallway (the disciplining zone of exclusion for unwanted feelings and behaviour), it carried through a vent into the classroom for the entire class to acoustically witness her outburst at Ole. Thus, her attempt to separate this socially and personally undesirable inter-personal conflict from the collective context of the classroom collapses due to her expressive rage. Kristin identified relationships as important to her role as teacher. Her experience of vulnerability (feelings of failure) in this student relationship is also threatening because she fears that her anger may be perceived in the school as a sign of inadequacy, in an educational context where incompetence carries a peculiar meaning – as something undesirable and ultimately unbearable. We are prompted to interpret Kristin’s sense of failure as a reflection of the tendency in neoliberal culture for individuals to unconsciously internalise oppressive norms (Layton, Citation2007), giving rise to self-blame and shameful feelings for failures which are also the products of society. Cultural hierarchies, to which we add notions of ‘professional identity’ and ‘social conduct’ can furthermore cause teachers ‘to split off part of what it means to be human, thereby creating painful individual and relational repetition compulsions’ (Layton, Citation2007, p.146). As we have shown, depth-hermeneutics is particularly apt to identify, psychosocially, outlines of such collective formulas for behaviour (Nagbøl, Citation2002), and split-off experience, revealed by our example where one teacher’s loss of control indicates layers of mutually implicating scenes.

In the above we hope to have illustrated, with some theoretical apparatus, how the dialectical build-up to the fourth phase leads to a synthetisation of an individual’s narrative with the intersubjective unconscious with the social and cultural, thereby representing a psychosocial movement towards scenic understanding.

Providing closure to the session

To provide closure to the session the text owner is encouraged to speak about what he or she has observed, and what thoughts and feelings this may have given rise to, including elaborations on any ambiguities emerging from the group’s interpretation. The text owner should not be positioned as the authority of the text but rather encouraged to think in new ways through being attentive to the contributions of the group. By engaging with the group’s imaginary and critical interpretations in the case of Kristin, for example, the figure of the ‘good enough teacher’ (Bibby, Citation2017) may emerge as a more realistic ideal to which professional identity can be attached. Finally, the facilitator rounds off the session in a reflective mode by asking about any new thoughts in the group, thanking participants for their contributions.

A discussion on facilitation and pre-understanding

As academics with a mutual interest in psychosocial thinking, we have relied on theoretical knowledge in our interpretation of the case – this is not however a prerequisite to achieving understanding. The strength of depth-hermeneutics lies in the group’s ability to bring the scenes of the text to life together (Krüger, Citationforthcoming, see also p. 8), so that they may be imagined and critically examined in a relatively flat structure. In this sense, depth-hermeneutics may be considered a way of thinking and being together, rather than a mode of empirical investigation in sensu stricto. In a real-life setting, it is necessary to draw attention to two crucial aspects of the interpretation work. First i the task of generating understanding of the text through analysis. Second is the task of bringing to the surface obscured content emerging reflexively in the group’s thoughts, feelings and fantasies about the text. In depth-hermeneutics, these are two aspects of the same process, and we consider this duality a key methodological strength. But to what extent does holding this dual attention to the text, and to participants’ responses to the text, require expert facilitation? This depends on the purpose of the interpretation work. If the aim is to gain in-depth understanding of a complex problem with a view towards achieving ‘therapeutic outcome’, this would require a facilitator with psychodynamic training. If the aim is to encourage reflective practice, the session could be feasibly facilitated and contained (Bion, Citation1970) by an experienced educator or an educational psychologist, whose responsibilities include supporting teachers (Kennedy, Frederickson, & Monse, Citation2008) when students have emotional and behavioural difficulties. In any case, the facilitators should be able to initiate and lead on didactically in the first phases, and challenge common sense assumptions. Educational psychologists have been found to espouse theories based on solution-focused thinking, systemic practice and problem-solving (Kennedy et al., Citation2008). It could be argued that depth-hermeneutics represents the opposite approach; what we call ‘complexity expansion’. However, we believe that its group-orientation can offer a necessary shift to a ‘reciprocal learning process’ (Carrington, Citation2004).

In the second author’s experience, prior theoretical knowledge was not a prerequisite to students’ engagement with depth-hermeneutics. In his facilitation, he encouraged participants to become aware of the group’s processes during the text analysis. MA students tagged along through the first phases and were interested in deconstructing the text, as well as learning to identify unconscious aspects of their individual and group reactions through the interpretation process. This involved bringing to the fore and reflecting on antipathies or sympathies for a particular person or situation in the text. The main challenges were that students were confined by a pursuit of logical reasoning, or that they felt insecure about their competencies and contributions. Performance anxiety inhibited explorative impetus, as some participants refrained from speculation and desired to be problem solvers who concluded through consensus rather than allowing for the co-existence of multiple hypotheses or meanings. Other challenges included strong or dominant personalities, and behaviours of self-interest. However, because facilitation encouraged the groups to challenge their pre-understandings – where this could be duly recognized, personal investments were set aside and alternative interpretations emerged quite freely. This experience suggests attention to facilitation before initiating depth-hermeneutics in a group.

Concluding reflections

We have outlined a theoretically founded adaptation and application of depth-hermeneutics as a psychosocial approach to teachers’ reflective practice, illustrated through interpretation of an empirical case. This is a departure from Lorenzer’s conception of depth-hermeneutics as psychoanalytically informed cultural analysis, which required years of training and supervision. However, as researchers and educators we have been inspired by his method as ‘first and foremost a new way of observing and experiencing, a new technique, a craft one must learn to use’ (Nagbøl, Citation2002, p.303, our translation), and believe that, through appropriate facilitation, this craft can be developed in new contexts.

The strength of depth-hermeneutics lies in the group approach to text interpretation, in which everyone should feel encouraged to take part, regardless of professional experience, a priori knowledge or seniority. Participants gain awareness of the self through engagement with the other, in the text and in the group. Drawing on Jessica Benjamin, Adamowich et al. (Citation2014, p.136) claim that crucially, it ‘is through the recognition of others that we understand ourselves, including our qualities and abilities and our shortcomings and disabilities’. Scenic understanding, the aim of interpretation, is life practical in the sense that in order to achieve it, one has to get experientially involved with those phenomena one seeks to understand analytically (Nagbøl, Citation2002). Herein lies its potential as a conduit for teachers’ learning from experience, by:

encouraging and facilitating peer dialogue, as well as self-reflection, self-awareness and reflexivity by focusing together on a text related to emotional challenges in teaching

examining, through letting a text work on a group’s imaginations, unconscious intra- and intersubjective dynamics that may underlie blind-spots in teaching, including societal and institutional conditions which preclude the possibility of certain schemes of life

Depth-hermeneutics may inspire critically reflective practice for teaching professionals who must continue to renew themselves in relational encounters, while facing up to changing and challenging societal requirements. Future research should aim to document its implementation in a practice context.

Acknowledgments

We dedicate this paper to the International Research Group for Pscyho-Societal Analysis, which has developed and promoted psychosocial and psycho-societal approaches over the years, including depth-hermeneutics.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Birgitta Haga Gripsrud

Birgitta Haga Gripsrud is a Post-Doctoral Fellow in the research group Professional Relations in the Faculty of Health Sciences at the University of Stavanger. Gripsrud has a PhD in Cultural Studies (University of Leeds 2006). A prominent strand in her research is critical, creative and psychosocial approaches to cultures and experiences of embodiment, health, illness, ageing and death. Another strand of Gripsrud’s research concerns conditions for, and challenges in, professional relational work, professional development and sound professional practice. Gripsrud is a member of The International Research Group for Psycho-Societal Analysis and a founding member of The Association for Psychosocial Studies.

Karsten Mellon

Karsten Mellon research field is lifelong learning, adult learning and education, and leadership. He is an Associate Professor at University College Absalon, Denmark and a PhD Fellow at Roskilde University, Denmark, where he is writing his thesis based on a psycho-societal approach to life history research. Mellon is an associate member of the Professional Relations research group at the University of Stavanger, and a member of The International Research Group for Psycho-Societal Analysis, as well as Kenneth Gergen’s The Taos Institute.

Ellen Ramvi

Ellen Ramvi is Professor and Head of the research group Professional Relations at the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Stavanger. Areas of interest in her research involve emotional and relational aspects of professional activity and development. Her particular contribution to this research field has been to develop psychosocial perspectives and methodologies. She is a founding member of the Association for Psychosocial Studies, and a member of the International Research Group for Psycho-Societal Analysis, and The International Society for the Psychoanalytic Study of Organisations.

Notes

1. Psycho-societal and psychosocial approaches have mainly emerged in Europe (Clarke, Citation2002; Clarke & Hoggett, Citation2009; Froggett, Citation2002; Hollway & Jefferson, Citation2000; Salling Olesen, Citation2016; Soldz & Andersen, Citation2012). ‘Psycho-societal’, ‘psychosocial’ or ‘psycho-social’ reflect different disciplinary and theoretical inspirations, the former associated with ‘a German tradition represented by e.g. Thomas Leithäuser, Birgit Volmerg, Regina Becker-Schmidt, Ulrike Prokop and Christine Morgenroth, inspired by Alfred Lorenzer, Theodor W. Adorno and Oskar Negt – and the latter, a British tradition represented by e.g. Wendy Hollway, Tony Jefferson, Lynn Froggett, Prue Chamberlayne, and others’ (Salling Olesen, Citation2012, p.11).

2. Kristin gave this account to the researcher. The case has previously been published in Ramvi (Citation2010).

References

- Adamowich, T., Kumsa, M.K., Rego, C., Stoddart, J., & Vito, R. (2014). Playing hide-and-seek: Searching for the use of self in reflective social work practice. Reflective Practice, 15(2), 131–143.

- Avalos, B. (2011). Teacher professional development in teaching and teacher education over ten years. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(1), 10–20.

- Bereswill, M., Morgenroth, C., & Redman, P. (2010). Alfred Lorenzer and the depth-hermeneutic method. Psychoanalysis, Culture & Society, 15(3), 221–250.

- Bibby, T. (2017). The creative self: Psychoanalysis, teaching and learning in the classroom. London: Routledge.

- Bion, W.R. (1962). Learning from experience. Nortvale, NJ: Jason Aronson.

- Bion, W.R. (1970). Attention and interpretation. London: Routledge.

- Carrington, G. (2004). Supervision as a reciprocal learning process. Educational Psychology in Practice, 20(1), 31–42.

- Clarke, S. (2002). Learning from experience: Psycho-social research methods in the social sciences. Qualitative Research, 2, 173–194.

- Clarke, S., & Hoggett, P. (2009). Researching beneath the surface: Psycho-social research methods in practice. London: Karnac.

- Dausien, B., Hanses, A., Inowlocki, L., & Riemann, G. (2008). The Analysis of Professional Practice, the Self-Reflection of Practitioners, and their Way of Doing Things. Resources of Biography Analysis and Other Interpretative Approaches. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(1). Retrieved from: http://www.qualitative–research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/312

- Freud, S. (1915). The Unconscious. In J. Strachey & A. Lorenzer (Eds.), On the history of the post psychoanalytic movement, papers on metapsychology and other works (Vol. 14, The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Lorenzer ed., pp. 159–209). London: Vintage.

- Freud, S. (1920–1922). Beyond the pleasure principle; Group psychology; And, other works (Vol. 18). London: Hogarth Press.

- Froggett, L. (2002). Love, hate and welfare. Psychosocial approaches to policy and practice. Bristol: The Policy Press.

- Froggett, L., Conroy, M., Manley, J., & Roy, A. (2014). Between art and social science: Scenic composition as a methodological device. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 15(5). Retrieved from http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/2143/3684

- Froggett, L., Ramvi, E., & Davies, L. (2014). Thinking from experience in psychosocial practice: reclaiming and teaching ‘use of self’. Journal of Social Work Practice: Psychotherapeutic Approaches in Health, Welfare and the Community. doi:10.1080/02650533.2014.923389

- Frosh, S. (2010). Psychoanalysis outside the clinic. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gripsrud, BH., Ramvi, E., Froggett, L., Hellstrand, I., & Manley, J. (2018). Psychosocial and symbolic dimensions of the breast explored through a visual matrix. Nora - Nordic Journal Of Feminist and Gender Research, 26(3), 210–229. doi:10.1080/08038740.2018.1482958

- Hochschild, A.R. (1979). Emotion work, feeling rules, and social structure. American Journal of Sociology, 85(3), 551–575.

- Hoggett, P. (2017). Shame and performativity: Thoughts on the psychology of neoliberalism. Psychoanalysis, Culture & Society. doi:10.1057/s41282-017-0050-3

- Hollway, W. (2015). Knowing mothers: Researching maternal identity change. Basingstoke: Pallgrave Macmillan.

- Hollway, W., & Jefferson, T. (2000). Doing qualitative research differently: Free association, narrative and the interview method. London: Sage.

- Hollway, W., & Volmerg, B. (2010). Interpretation Group Method in the Dubrovnik Tradition. Manual.

- Isenbarger, L., & Zembylas, M. (2006). The emotional labour of caring in teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22(1), 120–134.

- Kennedy, E.K., Frederickson, N., & Monse, J. (2008). Do educational psychologists “walk the talk” when consulting? Educational Psychology in Practice, 24(3), 169–187.

- Klinge, L. (2016). Lærerens relationskompetence [The teacher’s relational competency] (PhD), Copenhagen University, Copenhagen.

- Krane, V., Karlsson, B., Ness, O., & Kim, H.S. (2016). Teacher-student relationship, student mental health, and dropout from upper secondary school. Scandinavian Psychologist, 3. doi:10.15714/scandpsychol.3.e11

- Krüger, S. (2017). Dropping depth hermeneutics into Psychosocial Studies – A Lorenzarian perspective. The Journal of Psycho-Social Studies, 10(1), 47–66.

- Krüger, S. (forthcoming). Reinvigorating Scenic Understanding – towards a critical practice of psychoanalytic cultural analysis, 1–47

- Laursen, P.F. (2006). Den autentiske lærer. Bliv en god og effektiv underviser – Hvis du vil [The authentic teacher: Become a good and effective educator – If you want]. Copenhagen: Gyldendals lærerbibliotek.

- Layton, L. (2007). What psychoanalysis, culture and society mean to me. Mens Sana Monographs, 5(1), 146–157.

- Leithäuser, T. (2013). Psychoanalysis, socialization and society – The psychoanalytical thought and Interpretation of Alfred Lorenzer. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13(3), 56–70.

- Loughran, J.J. (2002). Effective reflective practice: In search of meaning in learning about teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 53(1), 33–43.

- Moos, L., Krejsler, J., & Laursen, P.F. (Eds.). (2004). Relationsprofessioner – Lærere, pædagoger, sygeplejersker, sunhedsplejersker, socialrådgivere og mellemledere [Relational professions – Teachers, pedagogues, nurses, healthcare assistants, social workers and middle managers]. Aarhus: Danmarks Pædagogiske Forlag.

- Nagbøl, S.P. (2002). Oplevelsesanalyse og subjektivitet [Experiential analysis and subjectivity]. Psyke & Logos, 23(1), 32.

- Näring, G., Vlerick, P., & Van de Ven, B. (2012). Emotion work and emotional exhaustion in teachers: The job and individual perspective. Educational Studies, 38(1), 63–72.

- Nordenbo, S.E., Larsen, M.S., Tiftikci, N., Wendt, R.E., & Østergaard, S. (2008). Lærerkompetanser og elevers læring i barnehage og skole. Et systematisk review utført for Kunnskapsdepartementet [Teacher competency and children’s learning in kindergarten and school: A systematic review conducted for the Department of Education] (Report No. 8776842487). Aarhus: D. P. Universitetsforlag.

- Ramvi, E. (2010). Out of control: A teacher’s account. Psychoanalysis, Culture & Society, 15(4), 328–345.

- Ramvi, E. (2017). Passing the buck, or thinking about experience? Conditions for professional development among teachers in a Norwegian middle school. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 5, 139–156.

- Ramvi, E., & Davies, L. (2010). Gender, mothering and relational work. Journal of Social Work Practice, 24(4), 445–460.

- Rothe, K., Krüger, S., & Rosengart, D. (forthcoming). Scenic understanding: Translated selections from Alfred Lorenzer’s ‘in-depth hermeneutical cultural analysis’ (1986) (pp. 1–25).

- Salling Olesen, H. (2012). The societal nature of subjectivity: An interdisciplinary methodological challenge. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13(3). Retrieved from http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1908

- Salling Olesen, H. (2016). A psycho-societal approach to life histories. In I. Goodson, A. Antikainen, P. Sikes, & M. Andrews (Eds.), The routledge international handbook on narrative and life history (pp. 214–224). London: Routledge.

- Salling Olesen, H. (2017). Læringsbarrierer, læringsmodstand og læringsforsvar – Prismer for en historisk konfliktutfoldelse [Barriers to learning, resistance to learning and learning defenses – Prisms for a historical conflict expansion]. In K. Mellon (Ed.), Læring eller ikke-læring? (pp. 23–38). Fredrikshavn: Dafolo.

- Salling Olesen, H., & Weber, K. (2012). Socialization, language, and scenic understanding. Alfred Lorenzer’s contribution to a psycho-societal methodology. 13(3). Retrieved from: http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1906

- Schön, D.A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Soldz, S., & Andersen, L.L. (2012). Expanding subjectivities: Introduction to the special issue on’new directions in psychodynamic research’. Journal of Research Practice, 8(2), 2.

- Stray, I.E., & Voreland, H.E. (2017). Refractions of the global educational agenda: Educational possibilities in an ambiguous policy terrain. In T. Rudd & I.F. Goodson (Eds.), Negotiating neoliberalism: Developing alternative educational visions (pp. 87–99). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Thompson, N., & Pascal, J. (2011). Reflective practice: An existentialist perspective. Reflective Practice, 12(1), 15–26.

- Williams, A. (2013). Critical reflective practice: Exploring a reflective group forum through the use of Bion’s theory of group processes. Reflective Practice, 14(1), 75–87.

- Youell, B. (2006). The learning relationship: Psychoanalytic thinking in education. London: Karnac.